Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

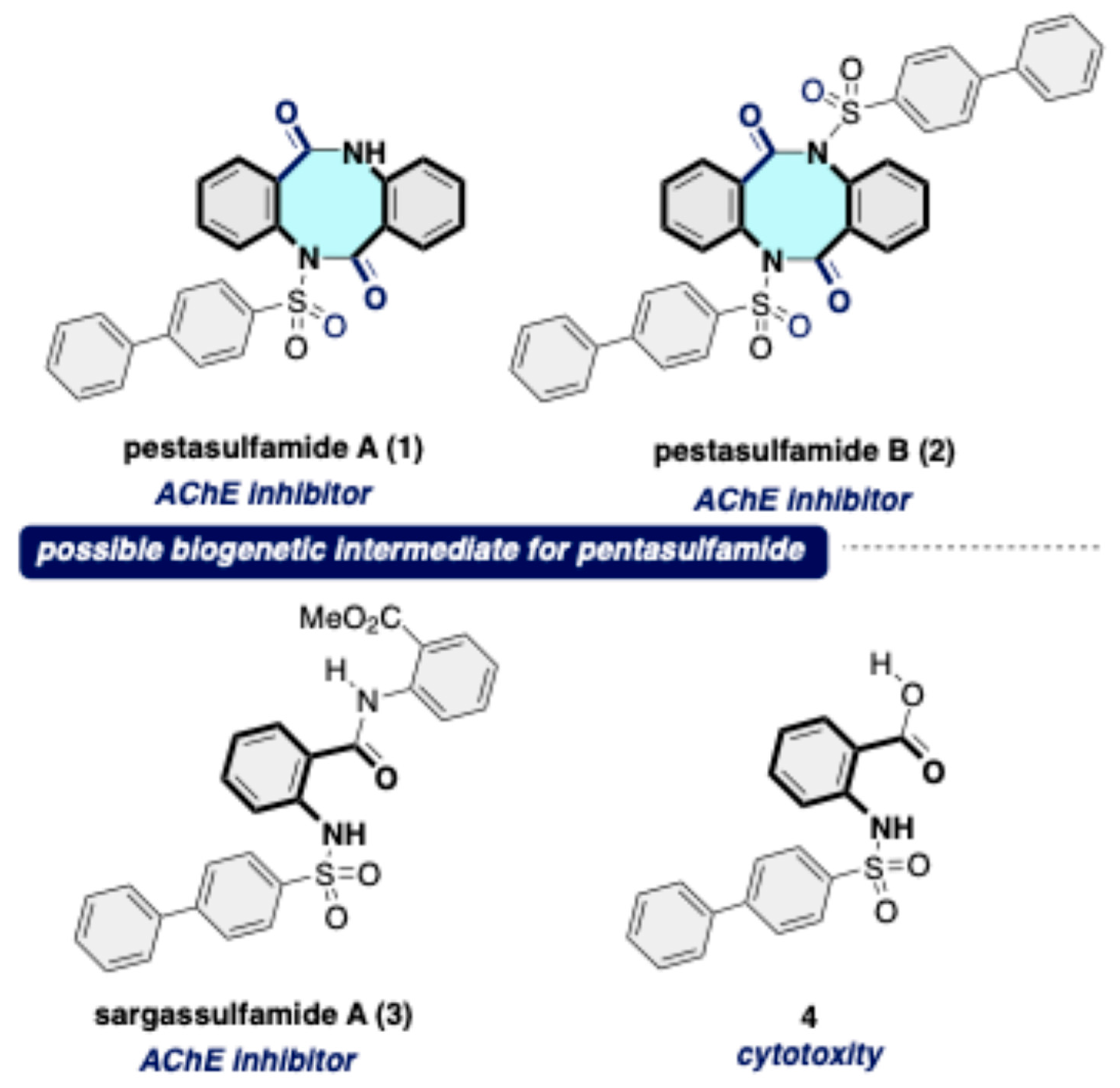

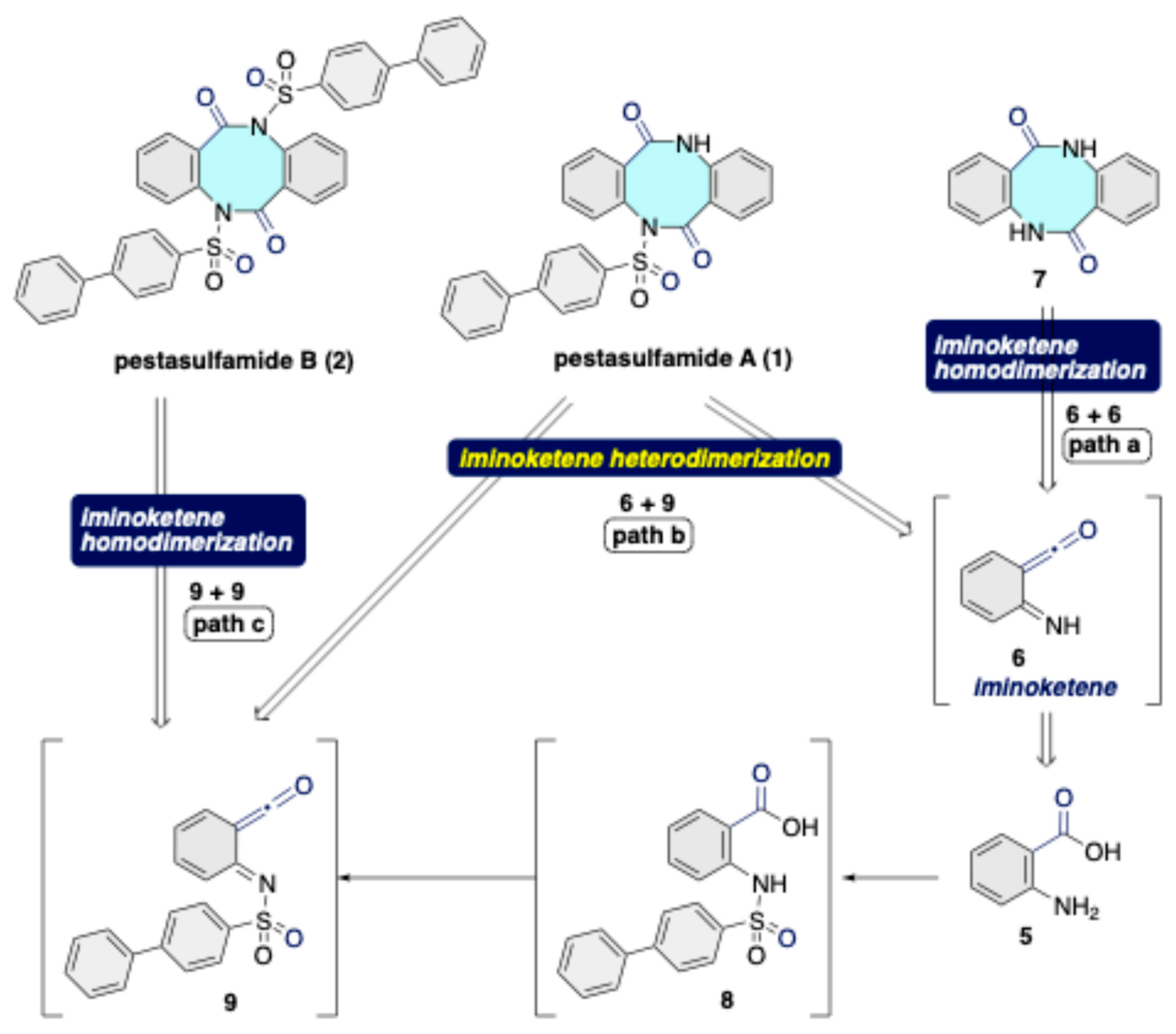

1. Introduction

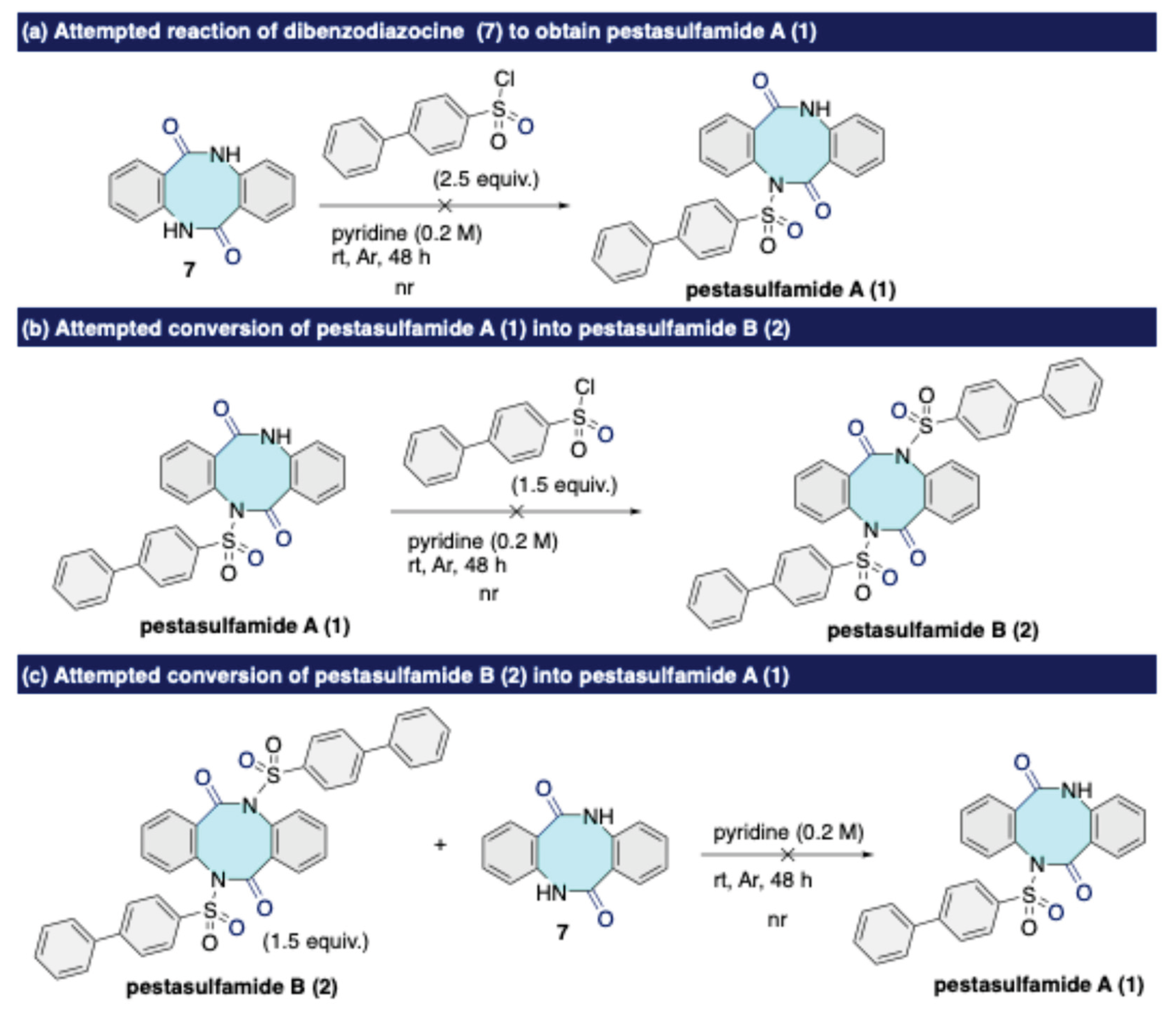

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

3.2. Experimental Procedures and Characterization Data for the Synthetic Products

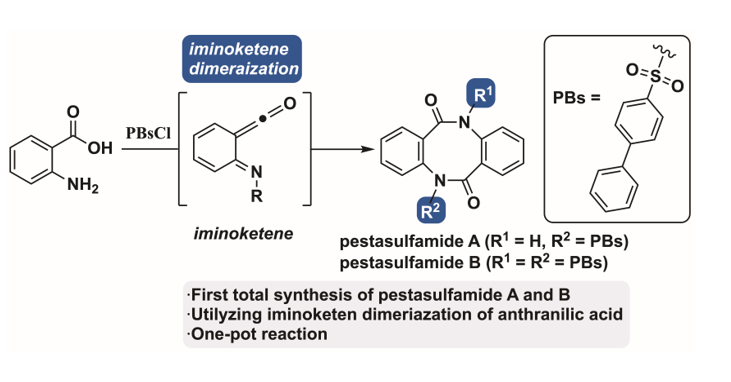

3.2.1. Synthesis of Pestasulfamide A (1) and Pestasulfamide B (2)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institution Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chhablani, A.; Jain, V.; Makasana, J. Sulfonamides: Historical Perspectives, Therapeutic Insights, Applications, Challenges, and Synthetic Strategies. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilardi, E.A.; Vitaku, E.; Njardarson, J.T. Datamining for Sulfur and Fluorine: An Evaluation of Pharmaceuticals to Reveal Opportunities for Drug Design and Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2832–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovung, A.; Bhattacharyya, J. Sulfonamide drugs: Structure, Antibacterial Property, Toxicity, and Biophysical Interactions. Biophys Rev. 2021, 13, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Delost, M.D.; Qureshi, M.H.; Smith, D.T.; Njardarson, J.T. A survey of the Structures of US FDA Approved Combination Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 4265–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuercher, W.J.; Buchholz, R.G.; Campobasso, N.; Collins, J.L.; Galardi, C.M.; Gampe, R.T.; Hyatt, S.M.; Merrihew, S.L.; Moore, J.T.; Oplinger, J.A.; et al. Discovery of Tertiary Sulfonamides as Potent Liver X Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3412–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosak, U.; Benedik, N.S.; Knez, D.; Zakelj, S.; Trontelj, J.; Pislar, A.; Horvant, S.; Bolje, A.; Znidarsic, N.; Grgurevic, N.; et al. Lead Optimization of a Butylcholinesterase Inhibitor for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 11693–11723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang-Song; Gao, Q.-L.; Wu, B.-W.; Li, D.; Shi, L.; Zhu, T.; Lou, J.-F.; Jin, C.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Zhang, S.-Y.; et al. Novel Tertiary Sulfonamide Derivatives Containing Benzimidazole Moiety as Potent Anti-gastric Cancer Agents: Design, Synthesis, and SAR Studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, L.; Marinacci, B.; Valle, A.D.; D’Agostino, I.; Lauro, A.; Mori, M.; Carradori, S.; Ammazzzalorso, A.; De Filippis, B.; Maccallini, C.; et al. Azobenzenesulfonamide Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors as New Weapons to Fight Heicobacter pylori: Synthesis, Bioactivity Evaluation, In Vivo Toxicity, and Computational Studies. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, P.; Poulsen, S.-A. Natural Product Primary Sulfonamides and Primary Sulfamates. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Xie, B.; Chen, T.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Sun, B.; She, Z. First discovery of sulfonamides derivatives with acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity in fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. HNY36-1D. Tetrahedron 2023, 142, 133524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, J.; Song, X. Arylsulfonamides from the Roots and Rhizomes of Tupistra chinensis Baker. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Cao, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, R. Sargassulfamide A, An Unprecedented Amide Derivatives from the Seaweed Sargassum naozhouense. Chem. Nat. Compounds. 2020, 56, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, P.; Polsen, S.-A. Natural Product Primary Sulfonamides and Primary Sulfamates. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baunach, M.; Ding, L.; Willing, K.; Hertweck. Bacterial Synthesis of Unusual Sulfonamide and Sulfone Antibiotics by Flavoenzyme-Mediated Sulfur Dioxide Capture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13279–13283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P.; Saravanan, C.; Singh, S.K. Sulphonamides: Deserving Class of MMP Inhibitors? Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 60, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaludercic, N.; Lindsey, M.L.; Tavazzi, B.; Lazzarino, G.; Paolocci, N. Inhibiting Metalloproteases with PD 166793 in Heart Failure: Impact of Cardic Remodeling and Beyond. Cardiovascular Therapeutics 2008, 26, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, F.C.; Partridge, M.W. Cyclic Amidines. Part 5 8-Dimethylphenohom. J. Chem. Soc. 1957, 2888–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska, T.; Gdaniec, M.; Polonski, T. Planner Chiral Dianthranilide and Dithiodianthranilide Molecules: Optical Resolution, Chroptical Spectra, and Molecular Self-Assembly. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Pan, Y.; Jin, L.L.; Yin, Y.; Yang, B.-Z.; Sun, X.-Q. Chiral Exploration of 6,12-Diphenyldibenzo[b.f][1,5]diazocine with Stable Conformation. Chirality 2017, 29, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, M.A.; Zhang, B.; Tilley, A.J.; Scheerlinck, T.; White, J.M. Amine-Substituted Diazocine Derivatives – Synthesis, Structure, and Photophysical Properties. Helv. Chim. Acta 2018, 101, e180146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnenmacher, E.; Hevertt, A.; Mahamoudt, A.; Aubert, C.; Molnartt, J.; Barbe, J. A Novel route to new dibenzo[b,f][1,5]diazocine Derivatives as Chemosensitizers. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 1997, 29, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, P.; Müller, E.; Rangits, G.; Lóránd, T.; Kollár, L. Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylation of 4-Substituted 2-Iodoaniline Derivatives: Carbonylative Cyclization and Aminocarbonylation. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 12051–12056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Ramana, K.V.; Ankati, H.B.; Ramana, A.V. Mild and Efficient Reduction of Azides to Amines: Synthesis of Fused [2,1]Quinazolines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 6861–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorfar, A.; Ollis, W.D.; Price, J.A.; Stephanatou, J.S.; Stoddart, J.F. Conformational Behaviour of Medium-sized Rings. Part 11. Dianthranilides and Trianthranilides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1982, 1649–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Wylie, S.W.; Teplin, E.; Morris, J.C.; Trombley, M.I.; McCarthy, S.M.; Cleaver, W.M.; Clark, G.R. Exploring Hydrogen-Bonded Structures: Synthesis and X-ray Crystallographic Screening of a Cisoid Cyclic Dipeptide Mini-Library. Cryst. Growth Des. 2004, 4, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, N.; Xu, S.; An, Z.; Shuang, X.; Lan, Z.; Wen, L.; Wan, X. Reductive Ring Closure Methodology toward Heteroacenes Bearing a Dihydropyrrolo [3,2-b]pyrrole Core: Scope and Limitation. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 11339–11348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieszczad, B.; Garbicz, D.; Trzybinski, D.; Mielecki, D.; Wozniak, K.; Grzesiuk, E.; Mieczkowski, A. Unsymmetrically Substituted Dibenzo[b,f][1,5]-diazocine-6,12(5H,11H)dione–A Convenient Scaffold for Bioactive Molecule Design. Molecules 2020, 25, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kametani, T.; Asagi, S.; Nakamura, S.; Satoh, M.; Wagatsuma, N.; Takano, S. Compounds containing Amino, Hydroxyl, or Carboxyl Groups with Mesyl Chloride. Yakugaku Zasshi 1966, 86, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Mi, M.; Li, S.-J.; Huang, J.-F.; Feng, P.; Lin, L.; Tang, Y. The Studies on the Synthesizing Dibenzodiazocinediimine via Constructing an Eight-Membered Ring. J. Org. Chem. 2025, 90, 6655–6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, N.; Wan, X. A Rapid and Efficient Access to Diaryldibenzo[b,f][1,5]diazocines. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Tang, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, L. Scandium Pentafluorobenzoate-Catalyzed Unexpected Cascade Reaction of 2-Aminobenzaldehydes with Primary Amines: A Process for the Preparation of Ring-Fused Aminals. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 12848–12854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, B.; Bergman, J.; Svensson, P.H. Synthetic Studies towards 1,5-Benzodiazocines. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, N.D.; Arcadi, A.; Chiarini, M.; Marinelli, F.; Portalone, G. Gold-Catalyzed Synthesis of Dibenzo [1,5]diazocines from b-(2-Aminophenyl)-a,b-ynones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 3371–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramle, A.Q.; Tiekink, E.R.T. Synthetic Strategies and diversification of Dibenzo [1,5]diazocines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 2870–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, T.; Itoh, T.; Choshi, T.; Hibino, S.; Ishikura, M. One-pot Synthesis of Tryptanthrin by the Dakin Oxidation of Indole-3-Carbaldehyde. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 5268–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Tarasaki, M. Synthesis of Phaitanthrin E and Tryptanthrin through Amination/Cyclization Cascade. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2018, 101, e1700284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Abe, T.; Choshi, T.; Nishiyama, T.; Ishikura, M. A One-pot Synthesis of Phaitanthrin E through Intermolecular Condensation/Intramolecular Aryl C–H Amination Cascade. Heterocycles 2016, 92, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, T.; Takeda, H.; Miwa, Y.; Yamada, K.; Yanada, R.; Ishikura, M. Copper-Catalyzed Ritter-type Reaction of Unactivated Alkenes with Dichloramine-T. Helv. Chim. Acta 2010, 93, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Kida, K.; Yamada, K. A Copper-Catalyzed Ritter-type Cascade via Iminoketene for the Synthesis of Quinazolin-4(3H)-ones and Diazocines. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 4362–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).