1. Introduction

Eukaryotic cell membranes contain a remarkably diverse repertoire of lipids and the classical view of membranes as uniform lipid bilayers has evolved, allowing certain lipids to possess self-organizing properties that promote the formation of specialized membrane domains [

1]. Sphingolipids (SLs) are essential structural components of cell membranes, where they contribute significantly to membrane fluidity, curvature, and the organization of microdomains known as lipid rafts [

2]. In macrophages, these lipid rafts are enriched in cholesterol and SLs and serve as platforms for receptor clustering, cell signaling, antigen presentation, extracellular vesicles (EVs) biogenesis and phagocytic functions [

3,

4]. Disruption of SLs homeostasis impairs these functions and can modulate innate immune responses, especially via influencing Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and subsequent inflammatory cascades [

5].

The SLs constitute a complex class of bioactive lipids, which major representatives include ceramides (Cer), sphingomyelin (SM), sphingosine (Sph), sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), ceramide-1-phosphate (C1P), and various glycosphingolipids. Despite their structural diversity, SLs share interconnected anabolic and catabolic pathways that maintain cellular homeostasis. De novo SLs synthesis begins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where serine-palmitoyltransferase catalyzes the condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA to produce 3-ketosphinganine. Subsequent reduction and acylation steps yield dihydroceramide, which is desaturated to form Cer, the central hub of SLs metabolism. Cer can be further converted into SM, C1P, or glycosphingolipids such as glucosyl- (HexCer) and galactosyl-ceramides (LactCer). In parallel, the hydrolysis of SM by neutral or acid sphingomyelinases (ASM) provides an alternative source of Cer at the plasma membrane. Cer can also be degraded to Sph, which may either re-enter the biosynthetic cycle or be phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases to generate S1P, a key signaling lipid. In macrophages, SLs metabolism plays a pivotal role in the coordination of inflammatory responses, vesicle release, and membrane remodeling during activation [

6].

Acting both as pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators depending on the cellular and metabolic context, SLs have dual roles in immune response. Cer typically promotes cell death, inflammatory responses, and vascular leak, while S1P generally opposes these actions by supporting cell survival, vascular integrity, and resolution of inflammation [

7,

8]. In macrophages, inflammatory stimuli, such as LPS, dynamically remodel the SLs network, with discrete metabolites correlating with distinct activation states [

8]. Moreover, imbalances in the Cer/ S1P axis are linked to chronic inflammatory diseases, such as atherosclerosis, fatty liver disease, and neurodegeneration [

9,

10]. The spatial and temporal regulation of SLs species is thus critical for proper inflammatory resolution and prevention of pathological amplification of immune responses [

10].

Building upon the concept of membrane microdomains, SLs emerge as key regulators of vesicular trafficking. The generation of Cer by sphingomyelinases promotes the driving of intraluminal vesicles within multivesicular bodies (MVB), fundamental processes for the biogenesis of EVs [

11]. These lipid vesicles comprise a heterogeneous population of membrane-derived structures that include exosomes and larger microvesicles or ectosomes [

12]. Although both EVs subtypes originate from distinct biogenic pathways, they share similar lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids cargo [

12,

13,

14]. In this context, EVs regulate the extracellular and intercellular microenvironment, support physiological processes and can contribute to inflammatory and degenerative disorders [

15]. Additionally, the Cer transfer protein CERT is directly involved in regulating both the Cer and SM content of EVs, thus linking SLs metabolism to EV biogenesis through the ESCRT pathway [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Changes in SLs composition not only modulate the amount of EVs produced but also modify their cargo and functional effects in recipient cells [

20]. In addition, SL-enriched EVs from immune cells can influence macrophage polarization and migration, with implications for tissue repair and inflammatory disease progression [

21]. Therefore, the specific SLs content of EVs is crucial for role in intercellular communication, affecting pathophysiological processes such as neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease, and cancer progression [

22,

23].

Pharmacological inhibition of ASM, an enzyme responsible for Cer production, has been shown to impair EVs formation. Fluoxetine (FXT), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) known to functionally inhibit ASM (FIASMA), may therefore alter SLs homeostasis and EVs dynamics [

24]. This action has several downstream effects, such as diminishes the Cer-rich domains required for viral entry, as observed with SARS-CoV-2, and may modulate inflammatory signaling in both immune and non-immune cells [

24]; chronic FXT treatment leads to SM accumulation and Cer reduction, which is associated with enhanced autophagy and neuroprotection [

25]. Concisely, by targeting SLs metabolism, FXT and related SSRI have pleiotropic effects that extend beyond neurotransmission, influencing inflammation, cell survival, and potentially viral susceptibility [

24].

In this context, we investigated the effects of FXT on macrophage SLs metabolism and EVs release stimulated with inactivated-SARS-CoV-2 to better elucidate its broader immunomodulatory mechanisms. Our results shown that inactivated-SARS-CoV-2 particles induces a robust inflammatory response in macrophages, while FXT treatment attenuates the production of key pro-inflammatory mediators commonly elevated in COVID-19, and concurrently remodels the SLs composition in cellular membranes. Notably, the release and biogenesis of EVs were not significantly affected under these conditions. Reshaping SLs homeostasis, FXT influence macrophage activation and inflammatory signaling. Collectively, we provide new advancements into drug repurposing of FXT in regulating macrophage membrane lipid metabolism, inflammatory signaling, and EVs dynamics, emphasizing its dynamic function beyond antidepressant therapy toward immunometabolic modulation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

THP-1 monocytes (BRCJ 0234) were maintained and differentiated into macrophages as previously described [

26]. For prophylactic exposure, differentiated macrophages were treated with 1 µM FXT for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were washed with an incomplete medium to remove residual drug. Subsequently, cells were either stimulated with UV-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 (MOI 2.0) (MφV or MφV-FXT) or left unstimulated (Mφ0 or Mφ0-FXT). The viral inactivation was performed in a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) facility at the Center for Virology Research - FMRP–USP, Stimulation was carried out for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO

2. Finally, cells were washed again and incubated for 24 h in 40 mL of EV-depleted DMEM. Culture supernatants from the four groups were collected for subsequent EVs isolation and analysis.

2.2. Sphingolipid Extraction

For SLs extraction, 1×10⁶ cells were suspended in 1 mL PBS and transferred to glass centrifuge tubes. Samples were spiked with 10 µL internal standard (10 µM Cer/Sph Mixture II, LM6005, Avanti Polar Lipids, AL, USA), followed by addition of 300 µL HCl (18.5%), 1 mL MeOH, and 2 mL CHCl3. Samples were vortexed for 30 min (50 rpm) and centrifuged at 2000×g for 5 min. The organic phase was collected, and a second extraction was performed on the remaining aqueous phase with another 2 mL of CHCl3. Combined organic phases were evaporated under vacuum for 45 min at 45 °C. The dried lipids were resuspended in 50 µL MeOH:CHCl3 (4:1, v/v), vortexed for 1 min, centrifuged for 5 min at 2000×g, and the supernatant was injected into the LC-MS/MS system.

2.3. LC-MS/MS Quantification of Sphingolipids

Chromatographic separation was performed on an Ascentis Express C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.7 µm; Supelco, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 40 °C using a Nexera X2 HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Samples (10 µL) were injected after column equilibration for 20 min, as described by our research group [

27]. Briefly, a binary gradient system was employed, solvent A (H

2O with 1% formic acid) and solvent B (MeOH), delivered at 0.5 mL/min with the following program: 0-1 min (30% B), 1.1-2.5 min (85% B), 2.5-5.0 min (100% B), 5.0-15.0 min (100% B), 15.1-20.0 min (re-equilibration at 30% B). Detection was carried out using a TripleTOF 5600

+ mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Redwood City, CA, USA) operated in positive electrospray ionization (ESI) mode with high-resolution multiple reaction monitoring (MRM

HR). External calibration was performed using an atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) probe with positive SCIEX calibration solution (SCIEX, Redwood City, CA, USA), maintaining a mass accuracy < 2 ppm. Instrument parameters were as follows: GS1 = 50 psi, GS2 = 50 psi, CUR = 25 psi, ISVF = +4500 V, source temperature = 500 °C, dwell time = 10 ms, mass resolution = 35,000 at

m/z 400. Data acquisition and qualitative analysis were conducted using Analyst

TM and PeakView

TM software (SCIEX, Redwood City, CA, USA). Quantification was performed with MultiQuant

TM (SCIEX, Redwood City, CA, USA), normalizing peak areas to internal standards. Monoisotopic correction accounted for

13C isotope abundance [

28]. Final concentrations (pmol/mL) were derived by multiplying the analyte-to-standard peak area ratio by the known standard concentration.

2.4. Isolation and Purification of Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

All the experiments of isolation and physicochemical analysis of EVs were performed following the Minimal Information for Studies of EV (MISEV2024) guidelines [

29]. In brief, cell culture supernatants (40 mL) were clarified by sequential centrifugation at 5000×g (15 min) and 15,000×g (15 min) at 4 °C (Sorvall Legend XFR, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The clarified supernatants were concentrated using a 100 kDa Amicon system (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and filtered through 0.45 µm membranes. Filtrates were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g for 1 h at 4 °C in an ultracentrifuge equipped with a 70 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The final EVs pellet was resuspended in 1 mL ultrapure H

2O (MilliQ, Darmstadt, Germany) and stored at -80 °C until analysis.

2.5. Extracellular Vesicles Characterization

Particle size distribution and concentration were measured by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using a NanoSight NS300 (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). For each sample, three times 30 s recordings were captured and analyzed to determine mean size and dispersion profiles. For morphological assessment, EVs suspensions were adsorbed onto carbon-coated Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) for 20 min, fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), rinsed with deionized water (MilliQ, Darmstadt, Germany), and visualized with a JEM-2100 microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), available at Electron Microscopy Multiuser Laboratory at Department of Cell and Molecular Biology (FMRP-USP).

2.6. Protein Mediators Quantification

Secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10; Cat. No. 555157), interleukin-1β (IL-1β; Cat. No. 557953), matrix metalloproteinases -3 (MMP-3, Cat. No. DY513) and -9 (MMP-9, Cat. No. DY911) in culture supernatants were quantified using BD OptEIA™ Human ELISA kits for cytokines (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and RD DuoSet-Human ELISA kits for MMPs (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA), following the manufacturers protocols.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data visualization and statistical comparisons were performed in GraphPad Prism (v9.1, San Diego, USA). Multivariate lipidomics analyses were conducted using R packages such as MetaboAnalystR, ggplot2 and ComplexHeatmap. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was applied for parametric comparisons among treatments. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used for comparisons among stimulation conditions. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and only significant p-values are indicated in figures.

3. Results

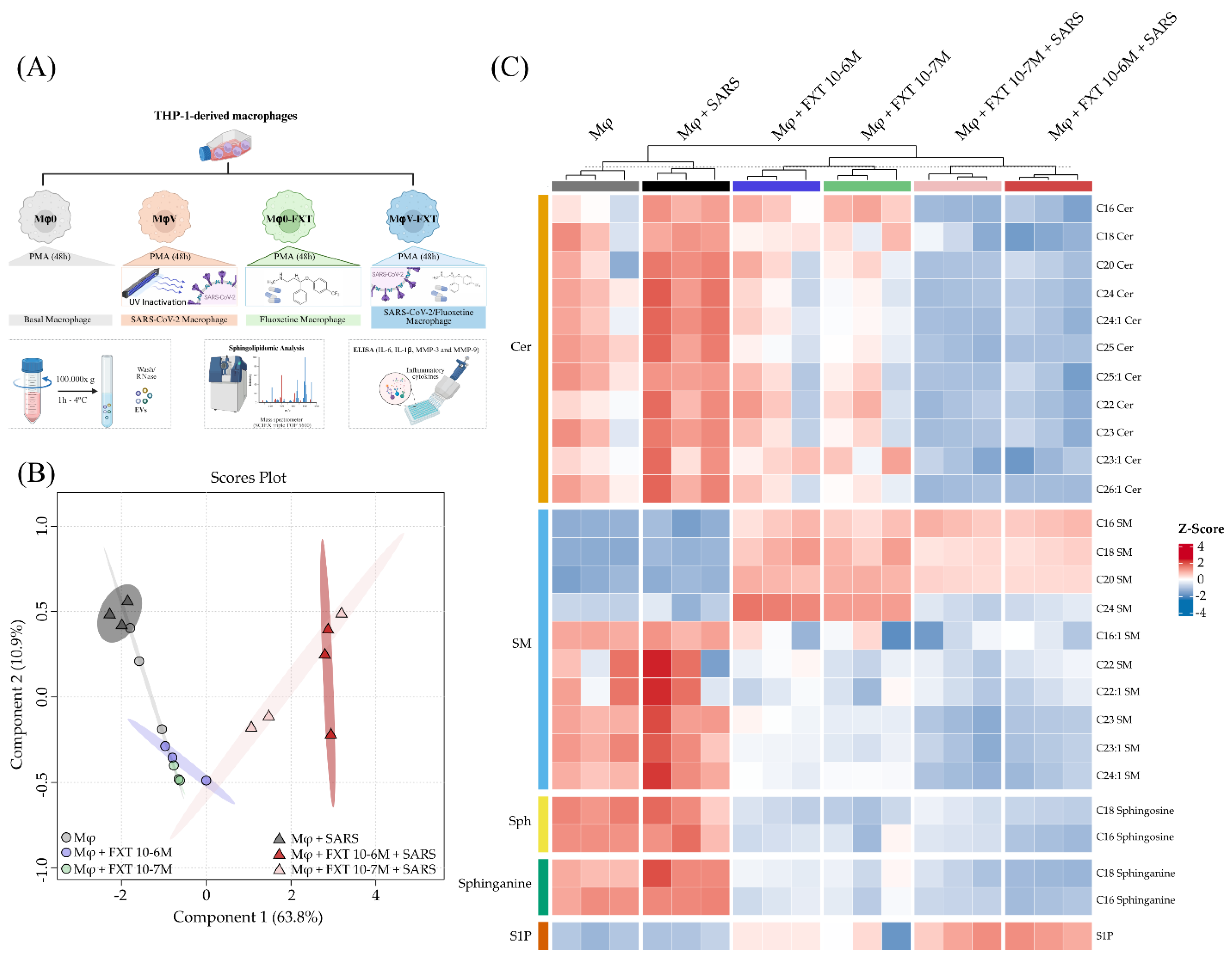

3.1. Viral Stimulation and Fluoxetine Treatment Modulate Macrophage Sphingolipidomes

To investigate whether FXT treatment could modulate macrophage lipid profiles, we utilized a sphingolipidomics approach in THP-1-derived macrophages (

Figure 1A). We observed that both non-stimulated macrophages (Mφ0) and inactivated-SARS-CoV-2 stimulated macrophages (MφV) presented similar overall sphingolipid profiles, despite the intensity of Cer and SM on MφV group. However, prophylactic FXT treatment in 10

−7 and 10

−6 M concentrations (Mφ0+FXT and MφV+FXT groups) robustly altered cells sphingolipidomes, differentially when compared with non-treated groups (

Figure 1B). Main differences in the sphingolipidomes were found in the classes of SLs: Cer, SM, Sph, sphinganines, and S1P. We demonstrated qualitative higher Cer, Sph and sphinganines levels in the MφV group compared to the others (

Figure 1C). Interestingly, S1P levels were completely dependent on FXT treatment, being specially increased in MφV+FXT groups, while Cer, Sph and sphinganines have been strongly reduced in the same groups. We observed a dimorphic pattern in SM abundances, in which C16, C18, C20 and C24 SM had their levels increased only upon FXT treatment, but the other SM species were completely reduced in the same groups (Mφ0+FXT and MφV+FXT). Furthermore, the C24 SM species was present only in Mφ0+FXT.

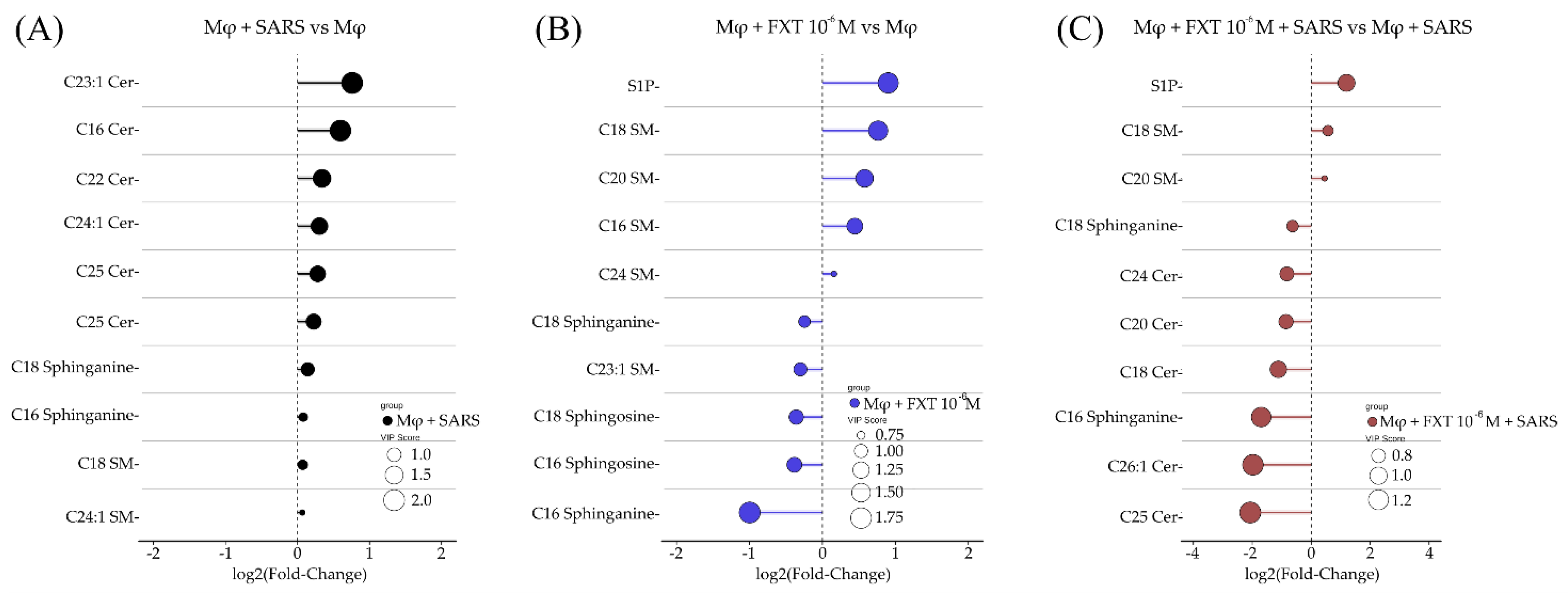

3.2. Fluoxetine Shifts Sphingolipid Balance in SARS-CoV-2–Stimulated Macrophages

We further investigated which specific lipid species were most modulated within each group. To better visualize the magnitude and direction of the sphingolipidomic changes, we provide a representation of statistical comparisons between groups and VIP score. Each data point represents an individual lipid species, connected to the baseline, allowing a depiction of the degree of modulation relative to the reference condition. This visualization facilitates the identification of the most significantly altered species and emphasizes overall trends in sphingolipid remodeling across experimental groups. As shown in

Figure 2A, comparison of the sphingolipidomes of the MφV and Mφ0 groups revealed that C23:1 Cer exhibited the greatest upregulation, followed by other Cer species such as C16, C22, C24:1, C25, and C24 Cer. This result emphasizes a shift toward pro-apoptotic and inflammatory lipid signaling. When comparing the Mφ0+FXT (10⁻⁶ M) and Mφ0 groups, FXT treatment increased the levels of S1P, C18, C20, C16, and C24 SM, while reducing C18 and C16 sphinganines, C18 and C16 Sph, and C23:1 SM (

Figure 2B). In MφV+FXT (10⁻⁶ M) compared to MφV (

Figure 2C), we observed elevated S1P levels accompanied by increases in C18 and C20 SM. However, in contrast to Mφ0, the most pronounced reduction occurred among Cer species, with decreases in C24, C20, C18, C26:1, and C25 Cer following FXT treatment. These data indicate high ASM activity in MφV and FXT treatment effects direct these enzyme products, as demonstrated by SM preservation and Cer depletion. Indeed, the notable S1P increase following FXT treatment, these findings support an anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory environment.

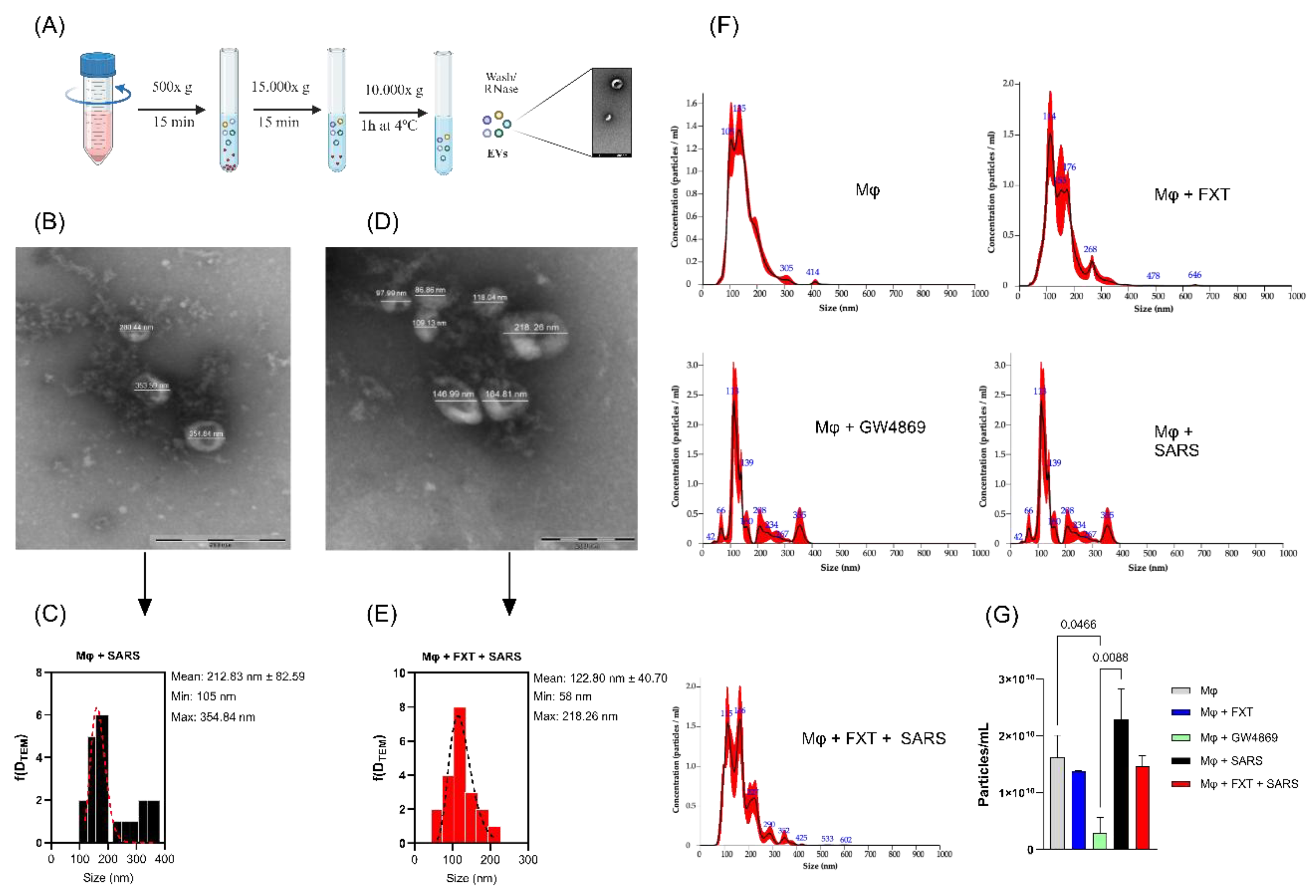

3.3. Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Production Was Not Modulated by Fluoxetine Treatment

Considering the fundamental role of EVs in mediating intercellular communication and propagating inflammatory signals during viral infections, we investigated how treatment with FXT could modulate their biogenesis, morphology, and physicochemical properties (

Figure 4A). The TEM analyses revealed that treatment with FXT substantially reduces the average diameter of EVs released after stimulation with SARS-CoV-2 particles, indicating that FXT treatment modulates cargo composition and diminishes the EVs size (

Figures 4B-E). For NTA analysis, we included a group of EVs from macrophages treated with neutral-SMase inhibitor (GW4869 - 10 μM), described as EVs release inhibitor, to be a positive control [

30]. Although FXT markedly impacted EVs size, it did not significantly alter the total concentration of particles produced compared to untreated virus-stimulated cells (

Figures 4F-G); while treatment with GW4869 significantly reduced EVs production compared to the Mφ0 (

p = 0.0466) and MφV (

p = 0.0088). Altogether, these results demonstrated a selective mechanism by which FXT modulates the physicochemical properties of EVs, potentially influencing their functional role, without affecting the overall release of EVs.

Figure 3.

Fluoxetine treatment induces smaller macrophage-derived EVs but non-effect on biogenesis release. (A) Flowchart for the production and extraction of Mφ EVs. Created in BioRender (BioRender Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada—Agreement number: KZ28ZD07D9). Representative TEM images and histograms, displaying the size distribution (nm) of EVs isolated from MφV (B and C) and MφV + FXT 10⁻⁶ M (D and E) groups. (F) Representative NTA analysis describing the size and concentration profile of isolated Mφ-EVs from the cells treated with FXT or GW4869 (10 x 10⁻⁶ M). (G) Concentration of EVs (particles/mL) released in each experimental condition, quantified by NTA (n = 3 per group; mean ± SD). Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05, calculated by one-Way-ANOVA with Tukey post-test. Scale bars for TEM are indicated within each image.

Figure 3.

Fluoxetine treatment induces smaller macrophage-derived EVs but non-effect on biogenesis release. (A) Flowchart for the production and extraction of Mφ EVs. Created in BioRender (BioRender Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada—Agreement number: KZ28ZD07D9). Representative TEM images and histograms, displaying the size distribution (nm) of EVs isolated from MφV (B and C) and MφV + FXT 10⁻⁶ M (D and E) groups. (F) Representative NTA analysis describing the size and concentration profile of isolated Mφ-EVs from the cells treated with FXT or GW4869 (10 x 10⁻⁶ M). (G) Concentration of EVs (particles/mL) released in each experimental condition, quantified by NTA (n = 3 per group; mean ± SD). Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05, calculated by one-Way-ANOVA with Tukey post-test. Scale bars for TEM are indicated within each image.

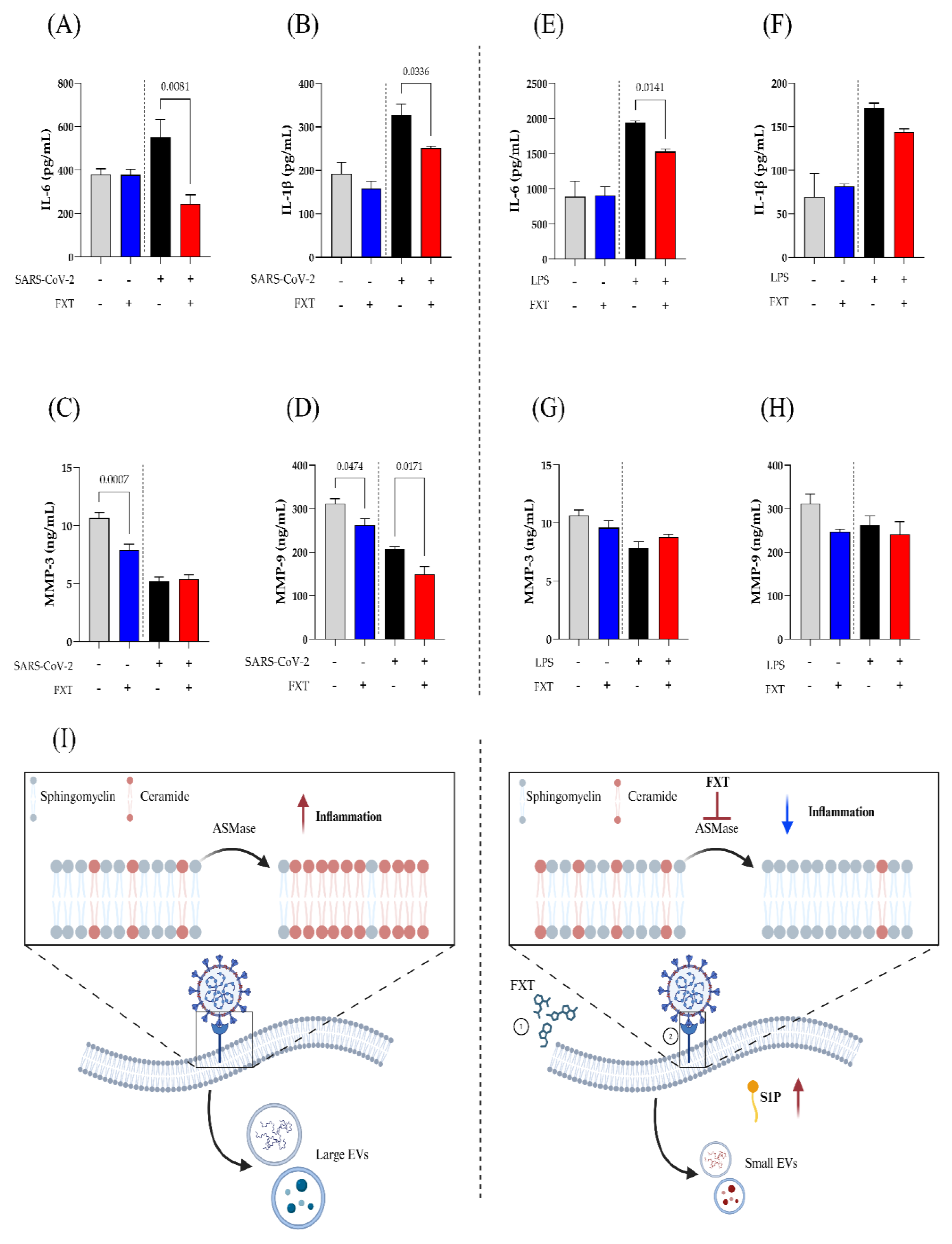

3.4. Fluoxetine Treatment Suppresses Inflammatory Mediators Released by SARS-CoV-2-Stimulated Macrophages

To test whether FXT treatment could modulate the production of inflammatory mediators in SARS-CoV-2-stimulated macrophages, we quantified IL-6, IL-1β, MMP-3 and -9 in cell culture supernatants by ELISA. In this context,

Figure 4A and 4B demonstrated significant reduction in the release of classic pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β, after FXT treatment and SARs-CoV-2-stimulation, key components of the COVID-19 cytokine storm. On the other hand, MMP-3 (

Figure 4C) and MMP-9 (

Figure 4D) release was significantly decreased by FXT treatment at macrophage basal level. Notably, all MMP levels were lower in the MφV groups compared to Mφ groups, regardless of FXT treatment. However, we observed a statistical reduction in MMP-9 levels of MφV+FXT compared to MφV (

p = 0.0171).

Evaluating other inflammatory stimulation, such as LPS (1 μg/mL), the macrophage treatment with FXT modulated only IL-6 levels with significant reduction (

p = 0.0141) (

Figure 4E). IL-1β levels showed a trend toward reduction in the treated group, although non-statistical significance (

Figure 4F). Further, MMP-3 (

Figure 4G) and MMP-9 (

Figure 4H) tend to decrease in cell basal level after FXT treatment, but non-significantly. These results suggest an immunoregulatory effect of prophylactic FXT treatment, attenuating the production of inflammatory mediators induced by different pathogenic stimuli.

Our findings indicate that FXT modifies the SLs composition of the MφV membrane, reducing Cer levels and increasing SM concentrations. Although the treatment altered the membrane lipid profile, EV biogenesis was not significantly affected. However, we observed a reduction in particle size, possibly related to changes in their cargo and biological function. Finally, FXT treatment regulated the production of cytokines and MMPs associated with the inflammation process, suggesting that its effect may contribute to attenuating the hyperinflammation and tissue damage observed in severe cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection (

Figure 4I).

4. Discussion

Lipid metabolism has emerged as a central regulator of immune response and EVs biogenesis, particularly through the modulation of SLs, which involves membrane curvature and signaling microdomains, such as lipid rafts[

11,

30]. Our study demonstrates that prophylactic treatment with FXT, a well-known SSRI and FIASMA, profoundly modulates SLs metabolism in macrophages while attenuating inflammatory responses to inactivated-SARS-CoV-2 stimulation. In the approach of integrated lipidomic and immunochemical analyses, we provide mechanistic evidence that FXT-induced remodeling of the Cer pathway, reprogramming the macrophage lipid composition and inflammatory process, has no effect on EVs biogenesis. In response to infectious stimuli or cellular injury, ASM is translocated to the cell surface, where it catalyzes Cer generation and drives membrane remodeling [

31]. This lipid reprogramming by selective inhibition of the ASM-Cer axis, led to consequent transition from a pro-inflammatory lipid signaling to an anti-inflammatory profile [

8]. Further, the synthesis and accumulation of Cer at the cell membrane and within endosomes directly modulate membrane dynamics, coordinating critical steps in EV biogenesis [

32].

The observed increase in SM and S1P levels, accompanied by reduced Cer species, is consistent with pharmacological inhibition of ASM activity. ASM catalyzes the hydrolysis of SM into Cer, a central hub in SL metabolism and an important regulator of membrane fluidity, lipid raft formation, and signaltransduction [

33,

34,

35]. The FXT-mediated shift toward SM accumulation suggests a suppression of Cer-driven inflammatory cascades, as Cer has been shown to facilitate the assembly of receptor complexes involved in NF-κB activation and cytokine release [

36,

37]. Conversely, S1P is associated with prosurvival and anti-inflammatory pathways through S1PR signaling [

38]. These findings support the concept that ASM inhibition rebalances the Cer–S1P rheostat, promoting a less inflammatory macrophage phenotype. Furthermore, SM participates in multiple cellular processes, including cell division, proliferation, and autophagy, while maintaining the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory lipids [

39].

Lipid raft microdomains associate with ASM at the cell membrane, where its enzymatic activity promotes membrane curvature and vesicular budding [

40]. Enveloped viruses, as well as intracellular pathogens such as

Neisseria gonorrhoeae [

41] and

Trypanosoma cruzi [

42], require ASM function during cell entry, as these pathogens share invasion mechanisms strongly associated with SM-rich membrane regions [

43,

44]. SARS-CoV-2, in turn, exhibits a unique capacity to fuse directly with the plasma membrane, thereby enabling efficient delivery of its viral genome into the host cell cytoplasm [

45].

Several ASM inhibitors, including antidepressants, have been shown to potently block SARS-CoV-2 entry in vivo [

35]. Beyond removing Cer from the membrane, these inhibitors induce endolysosomal cholesterol accumulation and disrupt acidification, thereby blocking viral entry through the endosomal route in a dose-dependent manner [

46,

47]. In contrast to Cer effects, sphingosine binds to ACE2 receptors at the membrane, blocking the interaction between ACE2 and the spike protein and consequently inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 entry [

48]. Considering that FXT has been reported to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro and to markedly suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production, our findings support a broader immunomodulatory role for FXT [[

49,

50].

Importantly, FXT pre-treatment significantly reduced the secretion of classical proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and IL-1β, by SARS-CoV-2-stimulated macrophage. This anti-inflammatory effect aligns with previous studies reporting that FIASMAs attenuate cytokine storm and macrophage activation in viral and bacterial infections [

51]. Our results extend these observations by linking the modulation of macrophage SL composition directly to the downregulation of inflammatory mediators in response to viral mimetic stimuli. The use of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 provides a relevant model of virus-induced innate activation, demonstrating the immunometabolic dimension of macrophage lipid interactions during infection. Studies of septic shock in vivo and allergic asthma, the non-serotonergic anti-inflammatory effects of FXT inhibited IL-6 and NF-κB signaling pathways [

52,

53], leading to decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IFN-γ, and TNF, thereby exerting a protective effect against chronic inflammation [

54]. Furthermore, FXT has been shown to reduce the immunostimulatory properties of tumor cells through macrophage reprogramming in inflammatory environments [

55]. Although our study focused on the prophylactic use of FXT, the evidence presented may point toward potential therapeutic strategies.

Although FXT altered the membrane lipid environment, it did not significantly change the number of EVs released. Instead, FXT-treated macrophages produced EVs with smaller size distribution. This observation suggests that while ASM inhibition and Cer depletion could modify membrane curvature and dynamics, they do not necessarily suppress EV biogenesis. Rather, they might influence the biophysical properties or cargo loading of EVs. Given that Cer is a critical factor in exosome formation via endosomal budding, partial inhibition of the ASM–Cer axis may selectively affect EV composition or function instead of overall release rates. Further proteomic and lipidomic profiling of EVs will be necessary to determine whether FXT-induced changes alter their immunomodulatory potential. Our method for isolating macrophage-derived EVs yielded consistent concentrations and morphologies, with particle sizes matching the reference ranges for microvesicles and exosomes [

56]. As expected, GW4869 markedly decreased the number of EVs, confirming the role of neutral-SMase in reducing secretion of larger ceramide-dependent EVs [

57,

58]. Despite the observed size reduction, these findings suggest that EV-cargo variation may be linked to inflammatory burden.

Despite these promising findings, some limitations should be considered in our study, that was conducted in THP-1–derived macrophages, although widely used as a model for human macrophage responses, may not fully recapitulate the complexity of primary macrophage populations or tissue-specific phenotypes in vivo. The use of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 provides a controlled model of viral-induced inflammation but lacks the dynamic aspects of viral replication and host–pathogen interactions that occur during infection. Also, the functional impact of FXT on EV-cargo and biological activity remains to be elucidated. Collectively, our findings provide novel evidence into the potential of FXT to exert immunomodulatory effects beyond neurotransmission. The remodelation SL metabolism and membrane architecture, FXT attenuates macrophage inflammation in response to viral triggers without disrupting intercellular communication through EVs. This supports the notion that targeting lipid metabolic checkpoints, particularly the ASM–Cer axis, represents a promising therapeutic approach for modulating excessive inflammation associated with viral infections and other immune-related disorders.

5. Conclusions

FXT profoundly reshapes SLs metabolism in macrophages by inhibiting the ASM–Cer axis, resulting in the accumulation of SM and S1P. This remodeling reestablishes SLs homeostasis and aligns with a balanced inflammatory state. The lipid reprogramming induced by FXT was associated with decreased production of IL-6, IL-1β, and MMP-9 following stimulation with inactivated SARS-CoV-2, reflecting an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype. Despite extensive changes in membrane lipid composition, the overall release of EVs remained unaltered, although their size distribution shifted toward smaller vesicles, suggesting potential modifications in lipid or protein cargo. Collectively, these findings provided the pharmacological capacity of FXT to modulate the ASM–Cer–S1P axis, unveiling its therapeutic potential in controlling excessive inflammation associated with viral or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.S.d.C and C.A.S.; methodology, J.C.S.d.C., P.N.-A., P.V.d.S.-N., B.T.M.O., L.A.T., D.M.T; A.O.B; M.A.N., E.A., R.B.M., F.A., C.A.S; validation, J.C.S.d.C., B.T.M.O., L.A.T and F.A.; formal analysis, J.C.S.d.C., P.N.-A., P.V.d.S.-N., B.T.M.O., L.A.T., M.A.N.; investigation, J.C.S.d.C and C.A.S.; resources, E.A., R.B.M., F.A., and C.A.S.; data curation, J.C.S.d.C., P.N.-A., P.V.d.S.-N and C.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.S.d.C., P.N.-A., P.V.d.S.-N., L.A.T., D.M.T., A.O.B., and M.A.N; writing—review and editing, C.A.S.; supervision, C.A.S.; funding acquisition, C.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo—FAPESP (grant #2024/03414-5 for C.A.S., #2022/07287-2, #2023/07776-6, for J.C.S.d.C.). Additional support was provided by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Educational Personnel (CAPES-Finance Code 001); National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq, #310683/2025-4 for C.A.S. The funders had no role in the study’s design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Electron Microscopy Laboratory of the Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto (FMRP-USP) for their technical assistance and infrastructure support during the acquisition and analysis of TEM data. We also thank the Center of Excellence for Quantification and Identification of Lipids (CEQIL) – Multiuser Facility supported by FAPESP (São Paulo Research Foundation, EMU #2015/00658-1) for providing access to high-resolution mass spectrometry and lipidomic analysis platforms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Simons, K.; Van Meer, G. Lipid Sorting in Epithelial Cells. Biochemistry 1988, 27. [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Toomre, D. Lipid Rafts and Signal Transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2000, 1. [CrossRef]

- Gaus, K.; Rodriguez, M.; Ruberu, K.R.; Gelissen, I.; Sloane, T.M.; Kritharides, L.; Jessup, W. Domain-Specific Lipid Distribution in Macrophage Plasma Membranes. J Lipid Res 2005, 46. [CrossRef]

- Dixson, A.C.; Dawson, T.R.; Di Vizio, D.; Weaver, A.M. Context-Specific Regulation of Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Cargo Selection. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Heinz, L.X.; Baumann, C.L.; Köberlin, M.S.; Snijder, B.; Gawish, R.; Shui, G.; Sharif, O.; Aspalter, I.M.; Müller, A.C.; Kandasamy, R.K.; et al. The Lipid-Modifying Enzyme SMPDL3B Negatively Regulates Innate Immunity. Cell Rep 2015, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, S.Y.; Bae, Y.S. Functional Roles of Sphingolipids in Immunity and Their Implication in Disease. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55. [CrossRef]

- Jernigan, P.L.; Makley, A.T.; Hoehn, R.S.; Edwards, M.J.; Pritts, T.A. The Role of Sphingolipids in Endothelial Barrier Function. Biol Chem 2015, 396. [CrossRef]

- Chiappa, N.F.; Lal, N.; Botchwey, E.A. Resolving vs. Non-Resolving Sphingolipid Dynamics During Macrophage Activation: A Time-Resolved Metabolic Analysis 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Peng, Q.; Huang, Y. Potential Therapeutic Targets for Atherosclerosis in Sphingolipid Metabolism. Clin Sci 2019, 133. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Perales, A.; Escribese, M.M.; Garrido-Arandia, M.; Obeso, D.; Izquierdo-Alvarez, E.; Tome-Amat, J.; Barber, D. The Role of Sphingolipids in Allergic Disorders. Frontiers in Allergy 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Verderio, C.; Gabrielli, M.; Giussani, P. Role of Sphingolipids in the Biogenesis and Biological Activity of Extracellular Vesicles. J Lipid Res 2018, 59. [CrossRef]

- Cocucci, E.; Meldolesi, J. Ectosomes and Exosomes: Shedding the Confusion between Extracellular Vesicles. Trends Cell Biol 2015, 25. [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, J.; Casari, I.; Manfredi, M.; Falasca, M. Role of Lipid Signalling in Extracellular Vesicles-Mediated Cell-to-Cell Communication. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2023, 73. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, M.; Névo, N.; Jouve, M.; Valenzuela, J.I.; Maurin, M.; Verweij, F.J.; Palmulli, R.; Lankar, D.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; et al. Specificities of Exosome versus Small Ectosome Secretion Revealed by Live Intracellular Tracking of CD63 and CD9. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in the Aging Microenvironment and Age-Related Diseases. J Extracell Vesicles 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Crivelli, S.M.; Giovagnoni, C.; Zhu, Z.; Tripathi, P.; Elsherbini, A.; Quadri, Z.; Pu, J.; Zhang, L.; Ferko, B.; Berkes, D.; et al. Function of Ceramide Transfer Protein for Biogenesis and Sphingolipid Composition of Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Wang, C. A Review of the Regulatory Mechanisms of Extracellular Vesicles-Mediated Intercellular Communication. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- Duro, M.G.; Tavares, L.A.; Furtado, I.P.; Saint-Pol, J.; D’Angelo, G. Protrusion-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (PD-EVs) and Their Diverse Origins: Key Players in Cellular Communication, Cancer Progression, and T Cell Modulation. Biol Cell 2025, 117. [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, N.R.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Joliot, A.; Théry, C. Extracellular Vesicles: A Complex Array of Particles Involved in Cell-to-Cell Communication for Tissue Homeostasis. Cells & Development 2025, 204054. [CrossRef]

- Skotland, T.; Hessvik, N.P.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Exosomal Lipid Composition and the Role of Ether Lipids and Phosphoinositides in Exosome Biology. J Lipid Res 2019, 60. [CrossRef]

- Hakkar, R.; Brun, C.E.; Leblanc, P.; Meugnier, E.; Berger-Danty, E.; Blanc-Brude, O.; Tacconi, S.; Jalabert, A.; Reininger, L.; Pesenti, S.; et al. Sphingolipids in Extracellular Vesicles Released From the Skeletal Muscle Plasma Membrane Control Muscle Stem Cell Fate During Muscle Regeneration. J Extracell Vesicles 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, O.M.; Mir, R.A.; Nehvi, I.B.; Wani, N.A.; Dar, A.H.; Zargar, M.A. Emerging Role of Sphingolipids and Extracellular Vesicles in Development and Therapeutics of Cardiovascular Diseases. IJC Heart and Vasculature 2024, 53. [CrossRef]

- Natale, F.; Fusco, S.; Grassi, C. Dual Role of Brain-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Dementia-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders: Cargo of Disease Spreading Signals and Diagnostic-Therapeutic Molecules. Transl Neurodegener 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hoertel, N.; Sánchez-Rico, M.; Cougoule, C.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J.; Carpinteiro, A.; Becker, K.A.; Reiersen, A.M.; Lenze, E.J.; Seftel, D.; et al. Repurposing Antidepressants Inhibiting the Sphingomyelinase Acid/Ceramide System against COVID-19: Current Evidence and Potential Mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Brunkhorst, R.; Friedlaender, F.; Ferreirós, N.; Schwalm, S.; Koch, A.; Grammatikos, G.; Toennes, S.; Foerch, C.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Pfeilschifter, W. Alterations of the Ceramide Metabolism in the Peri-Infarct Cortex Are Independent of the Sphingomyelinase Pathway and Not Influenced by the Acid Sphingomyelinase Inhibitor Fluoxetine. Neural Plast 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- da Silva-Neto, P. V.; de Carvalho, J.C.S.; Toro, D.M.; Oliveira, B.T.M.; Cominal, J.G.; Castro, R.C.; Almeida, M.A.; Prado, C.M.; Arruda, E.; Frantz, F.G.; et al. TREM-1-Linked Inflammatory Cargo in SARS-CoV-2-Stimulated Macrophage Extracellular Vesicles Drives Cellular Senescence and Impairs Antibacterial Defense. Viruses 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Felippe, T. V.D.; Toro, D.M.; de Carvalho, J.C.S.; Nobre-Azevedo, P.; Rodrigues, L.F.M.; Oliveira, B.T.M.; da Silva-Neto, P. V.; Vilela, A.F.L.; Almeida, F.; Faccioli, L.H.; et al. High-Resolution Targeted Mass Spectrometry for Comprehensive Quantification of Sphingolipids: Clinical Applications and Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles. Anal Biochem 2025, 698. [CrossRef]

- Toro, D.M.; da Silva-Neto, P. V.; de Carvalho, J.C.S.; Fuzo, C.A.; Pérez, M.M.; Pimentel, V.E.; Fraga-Silva, T.F.C.; Oliveira, C.N.S.; Caruso, G.R.; Vilela, A.F.L.; et al. Plasma Sphingomyelin Disturbances: Unveiling Its Dual Role as a Crucial Immunopathological Factor and a Severity Prognostic Biomarker in COVID-19. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic, K.; Hsu, C.; Chiantia, S.; Rajendran, L.; Wenzel, D.; Wieland, F.; Schwille, P.; Brügger, B.; Simons, M. Ceramide Triggers Budding of Exosome Vesicles into Multivesicular Endosomes. Science (1979) 2008, 319. [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.; Idone, V.; Devlin, C.; Fernandes, M.C.; Flannery, A.; He, X.; Schuchman, E.; Tabas, I.; Andrews, N.W. Exocytosis of Acid Sphingomyelinase by Wounded Cells Promotes Endocytosis and Plasma Membrane Repair. Journal of Cell Biology 2010, 189. [CrossRef]

- Menck, K.; Sönmezer, C.; Worst, T.S.; Schulz, M.; Dihazi, G.H.; Streit, F.; Erdmann, G.; Kling, S.; Boutros, M.; Binder, C.; et al. Neutral Sphingomyelinases Control Extracellular Vesicles Budding from the Plasma Membrane. J Extracell Vesicles 2017, 6. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, S.; Pang, W.; Zhao, Z. Crosstalk Between Acid Sphingomyelinase and Inflammasome Signaling and Their Emerging Roles in Tissue Injury and Fibrosis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Gulbins, E.; Palmada, M.; Reichel, M.; Lüth, A.; Böhmer, C.; Amato, D.; Müller, C.P.; Tischbirek, C.H.; Groemer, T.W.; Tabatabai, G.; et al. Acid Sphingomyelinase-Ceramide System Mediates Effects of Antidepressant Drugs. Nat Med 2013, 19. [CrossRef]

- Carpinteiro, A.; Edwards, M.J.; Hoffmann, M.; Kochs, G.; Gripp, B.; Weigang, S.; Adams, C.; Carpinteiro, E.; Gulbins, A.; Keitsch, S.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of Acid Sphingomyelinase Prevents Uptake of SARS-CoV-2 by Epithelial Cells. Cell Rep Med 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Abboushi, N.; El-Hed, A.; El-Assaad, W.; Kozhaya, L.; El-Sabban, M.E.; Bazarbachi, A.; Badreddine, R.; Bielawska, A.; Usta, J.; Dbaibo, G.S. Ceramide Inhibits IL-2 Production by Preventing Protein Kinase C-Dependent NF-ΚB Activation: Possible Role in Protein Kinase Cθ Regulation. The Journal of Immunology 2004, 173. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, H.; Vincent, V.; Chaurasia, B. Ceramide Signaling in Immunity: A Molecular Perspective. Lipids in Health and Disease 2025, 24. [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.P.; Mahanta, C.S.; Maurya, M.; Mandal, D.; Parihar, V.; Ravichandiran, V. Exploring SK/S1P/S1PR Pathway as a Target for Antiviral Drug Development. Health Sciences Review 2024, 11, 100177. [CrossRef]

- Harvald, E.B.; Olsen, A.S.B.; Færgeman, N.J. Autophagy in the Light of Sphingolipid Metabolism. Apoptosis 2015, 20. [CrossRef]

- Ermini, L.; Farrell, A.; Alahari, S.; Ausman, J.; Park, C.; Sallais, J.; Melland-Smith, M.; Porter, T.; Edson, M.; Nevo, O.; et al. Ceramide-Induced Lysosomal Biogenesis and Exocytosis in Early-Onset Preeclampsia Promotes Exosomal Release of SMPD1 Causing Endothelial Dysfunction. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Grassmé, H.; Gulbins, E.; Brenner, B.; Ferlinz, K.; Sandhoff, K.; Harzer, K.; Lang, F.; Meyer, T.F. Acidic Sphingomyelinase Mediates Entry of N. Gonorrhoeae into Nonphagocytic Cells. Cell 1997, 91. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.C.; Cortez, M.; Flannery, A.R.; Tam, C.; Mortara, R.A.; Andrews, N.W. Trypanosoma Cruzi Subverts the Sphingomyelinase-Mediated Plasma Membrane Repair Pathway for Cell Invasion. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2011, 208. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.E.; Adhikary, S.; Kolokoltsov, A.A.; Davey, R.A. Ebolavirus Requires Acid Sphingomyelinase Activity and Plasma Membrane Sphingomyelin for Infection. J Virol 2012, 86. [CrossRef]

- Grassmé, H.; Riehle, A.; Wilker, B.; Gulbins, E. Rhinoviruses Infect Human Epithelial Cells via Ceramide-Enriched Membrane Platforms. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181. [CrossRef]

- Schloer, S.; Brunotte, L.; Goretzko, J.; Mecate-Zambrano, A.; Korthals, N.; Gerke, V.; Ludwig, S.; Rescher, U. Targeting the Endolysosomal Host-SARS-CoV-2 Interface by Clinically Licensed Functional Inhibitors of Acid Sphingomyelinase (FIASMA) Including the Antidepressant Fluoxetine. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, D.X.; Tam, J.P. Lipid Rafts Are Involved in SARS-CoV Entry into Vero E6 Cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 369. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.J.; Becker, K.A.; Gripp, B.; Hoffmann, M.; Keitsch, S.; Wilker, B.; Soddemann, M.; Gulbins, A.; Carpinteiro, E.; Patel, S.H.; et al. Sphingosine Prevents Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Spike to Its Cellular Receptor ACE2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2020, 295. [CrossRef]

- Roumestan, C.; Michel, A.; Bichon, F.; Portet, K.; Detoc, M.; Henriquet, C.; Jaffuel, D.; Mathieu, M. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Desipramine and Fluoxetine. Respir Res 2007, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sherkawy, M.M.; Abo-youssef, A.M.; Salama, A.A.A.; Ismaiel, I.E. Fluoxetine Protects against OVA Induced Bronchial Asthma and Depression in Rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2018, 837. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wu, M.; He, Y.; Jiang, B.; He, M.L. Metabolic Alterations upon SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Potential Therapeutic Targets against Coronavirus Infection. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Creeden, J.F.; Imami, A.S.; Eby, H.M.; Gillman, C.; Becker, K.N.; Reigle, J.; Andari, E.; Pan, Z.K.; O’Donovan, S.M.; McCullumsmith, R.E.; et al. Fluoxetine as an Anti-Inflammatory Therapy in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2021, 138. [CrossRef]

- Durairaj, H.; Steury, M.D.; Parameswaran, N. Paroxetine Differentially Modulates LPS-Induced TNFα and IL-6 Production in Mouse Macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol 2015, 25. [CrossRef]

- Sorrells, S.F.; Sapolsky, R.M. An Inflammatory Review of Glucocorticoid Actions in the CNS. Brain Behav Immun 2007, 21. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Choudhury, S.; Gupta, P.; Adhikary, A.; Baral, R.; Chattopadhyay, S. Reactive Oxygen Species in the Tumor Niche Triggers Altered Activation of Macrophages and Immunosuppression: Role of Fluoxetine. Cell Signal 2015, 27. [CrossRef]

- Bobrie, A.; Colombo, M.; Krumeich, S.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Diverse Subpopulations of Vesicles Secreted by Different Intracellular Mechanisms Are Present in Exosome Preparations Obtained by Differential Ultracentrifugation. J Extracell Vesicles 2012, 1. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Gapper, C.; Kaya, H.; Bell, E.; Kuchitsu, K.; Dolan, L. Local Positive Feedback Regulation Determines Cell Shape in Root Hair Cells. Science (1979) 2008, 319. [CrossRef]

- Risner, M.L.; Ribeiro, M.; McGrady, N.R.; Kagitapalli, B.S.; Chamling, X.; Zack, D.J.; Calkins, D.J. Neutral Sphingomyelinase Inhibition Promotes Local and Network Degeneration in Vitro and in Vivo. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).