Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

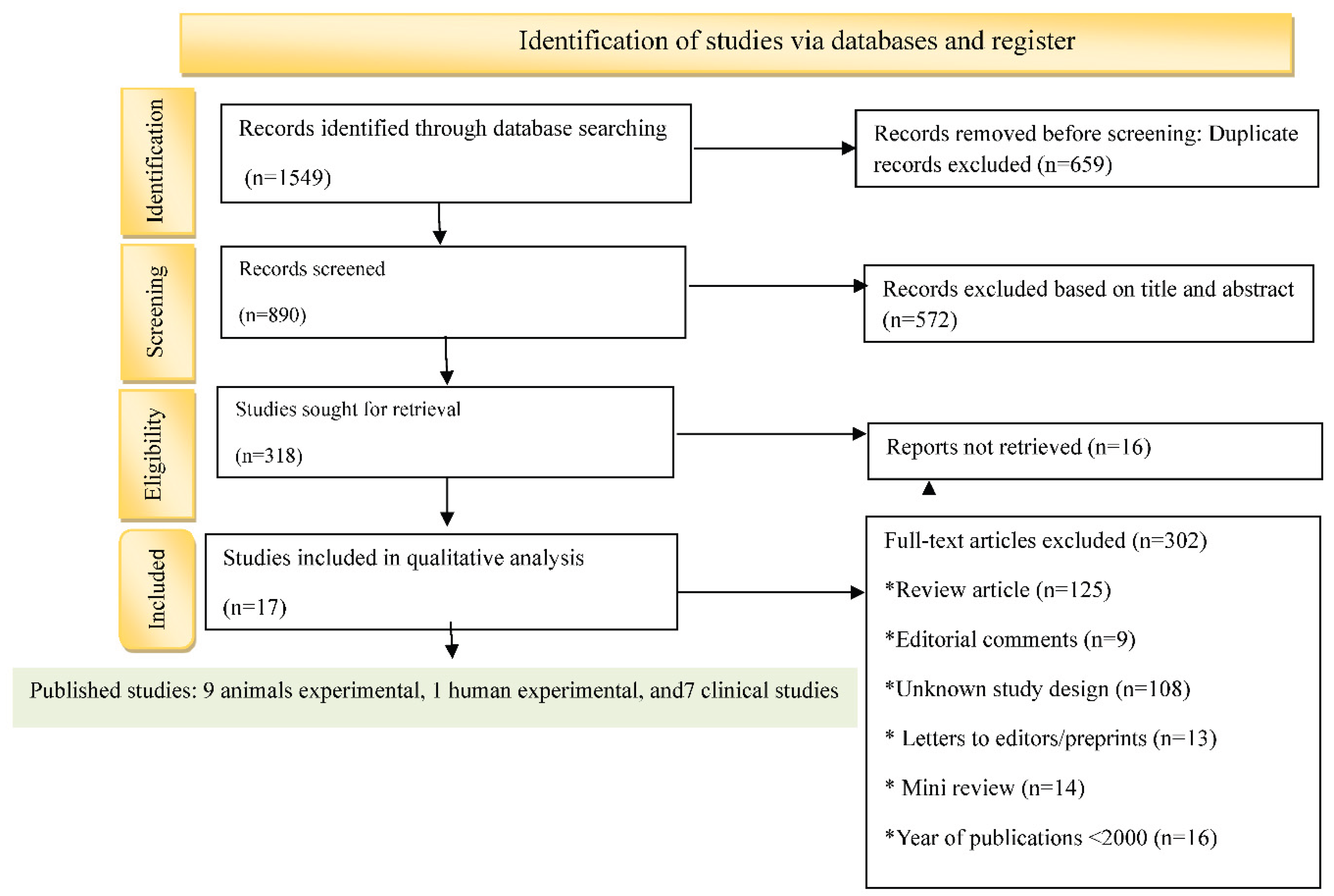

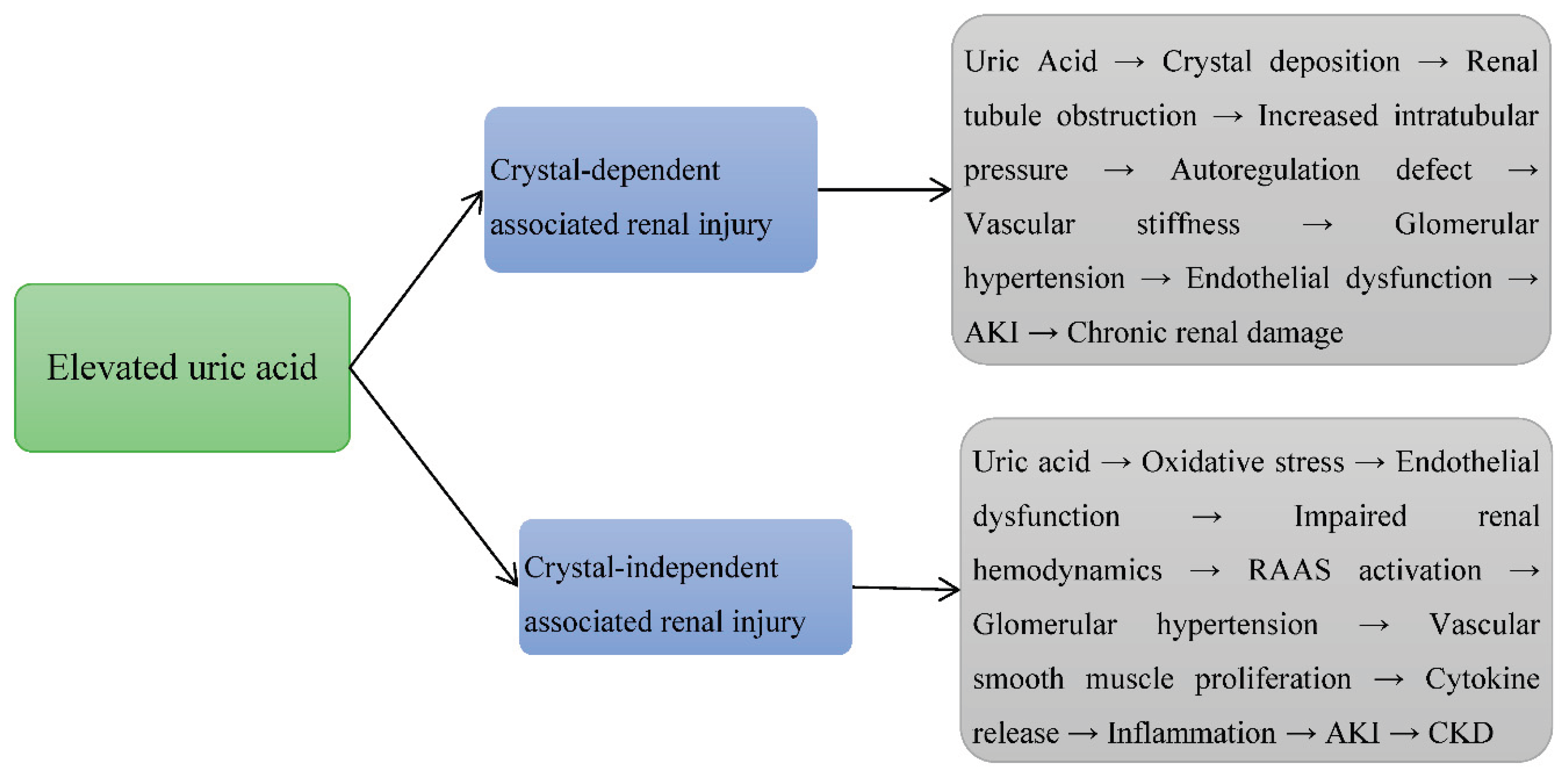

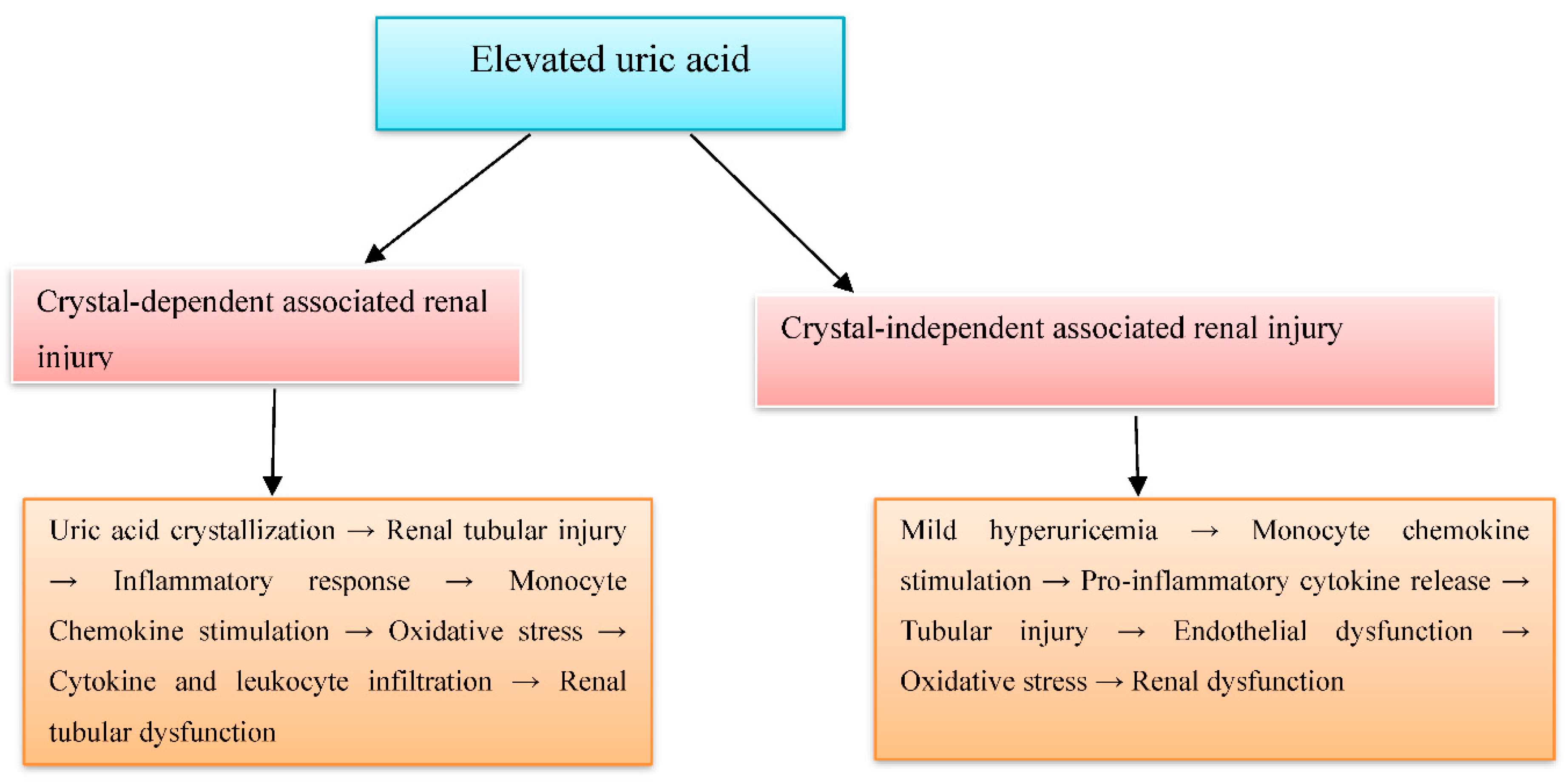

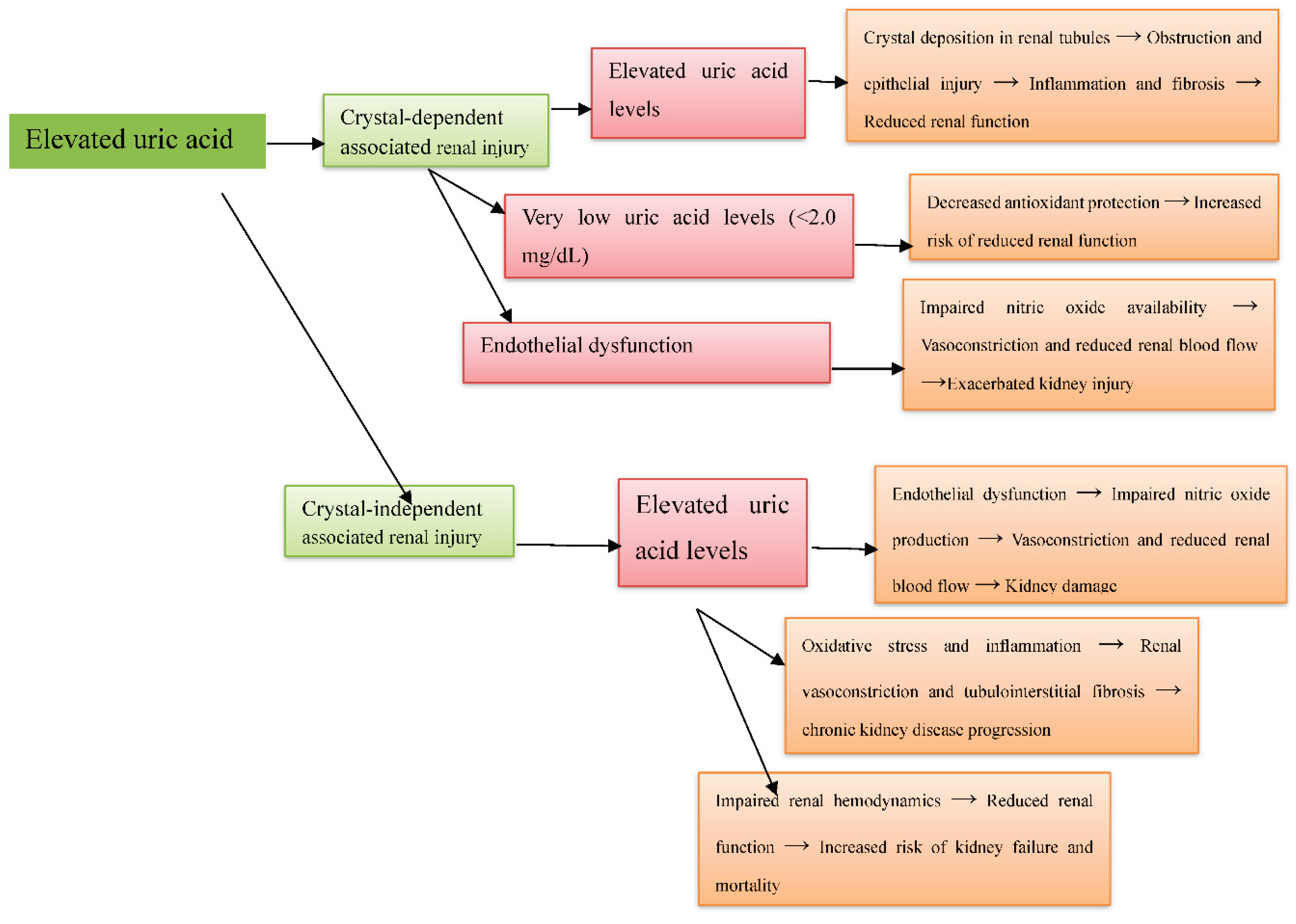

Background: Hyperuricemia, marked by elevated uric acid levels, is associated with renal disorders like acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease, through both crystal-dependent and crystal-independent mechanisms. Objective: This review aims to evaluate the crystal-dependent and crystal-independent mechanisms by which hyperuricemia induces renal injury. Design: A systematic review of the literature. Participants: Human and animal studies. Measurements: A total of 1549 articles were initially identified from PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. After removing 659 duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 572 articles were excluded, and 16 could not be retrieved, leaving 302 for full-text review. Of these, 17 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included. Risk of bias was assessed using SYRCLE for animal studies, ROB2 for human studies, and NOS for observational studies. Results: From seventeen studies: nine animal experiments, one human experiment, and seven observational studies. Animal studies showed hyperuricemia causes preglomerular arteriolopathy, glomerular hypertension, and worsens nephrotoxicity. Human studies demonstrated elevated uric acid, even without crystals, activates intrarenal RAS, increases oxidative stress, and reduces nitric oxide. Clinical studies confirmed high uric acid is linked to CKD progression, with very low levels also risky (“J-shaped” relationship). Endothelial dysfunction is a unifying mechanism, promoting inflammation and fibrosis in crystal-dependent injury and vasoconstriction and renal damage in crystal-independent injury. Conclusions: This review confirmed that hyperuricemia damages the kidney through both crystal-dependent and crystal-independent pathways, with endothelial dysfunction as a key mediator. Further human studies are needed to confirm these findings and explore new treatments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Criteria

3.2. Study Characteristics

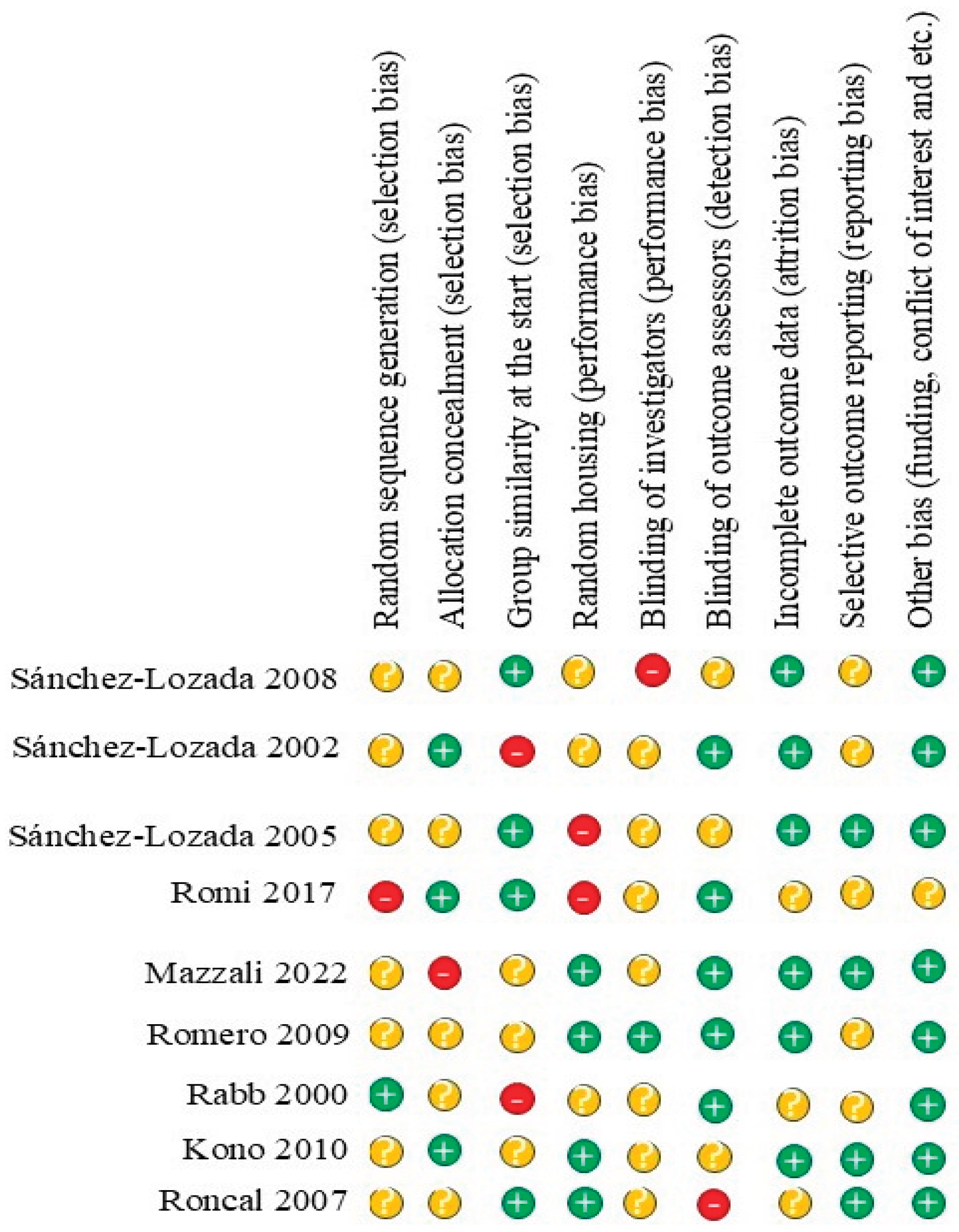

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment of Included Studies

3.4. Animal Experimental

3.4.1. Uric Acid-Associated Renal Injury via Crystal-Dependent Mechanisms in Animal Experimental Studies

3.4.2. Findings in Relation to Crystal-Independent Uric Acid-Induced Renal Injury in Animal Experimental Studies

3.5. Human Experimental

3.5.1. Uric Acid–Induced Renal Injury via Crystal-Dependent Mechanisms in Human Experimental Studies

3.5.2. Uric Acid–Induced Renal Injury via Crystal-Independent Mechanisms in Human Experimental Studies

3.6. Observational Studies

3.6.1. Uric Acid-Induced Acute Kidney Injury via Crystal-Dependent Mechanisms in Observational Studies

3.6.2. Uric Acid-Induced Renal Injury via Crystal-Independent Mechanisms in Observational Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Animal Studies

4.2. Human Experimental Studies

4.3. Observational Studies

4.4. Integrative View

4.5. Clinical and Research Implications

5. Limitations

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Informed consent

Declaration of conflicting interests

Data availability statement

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

References

- Du L, Zong Y, Li H, et al. Hyperuricemia and its related diseases: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2024 Aug 28;9(1):212. [CrossRef]

- Zhou M, Huang X, Li R, et al. Association of dietary patterns with blood uric acid concentration and hyperuricemia in northern Chinese adults. Nutrition journal. 2022 Jun 23;21(1):42. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad MI, Masood S, Furlanetto DM, et al. Urate crystals; beyond joints. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021 Jun 4; 8:649505. [CrossRef]

- Hao G, Xu X, Song J, et al. Lipidomics analysis facilitate insight into the molecular mechanisms of urate nephropathy in a gout model induced by combination of MSU crystals injection and high-fat diet feeding. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 2023 ; 10:1190683. 3 May. [CrossRef]

- Tola, GB. Exploring the Role of Elevated Uric Acid in Acute Kidney Injury: A Comprehensive Review of Pathways and Therapeutic Approaches.

- Russo E, Verzola D, Cappadona F, et al. The role of uric acid in renal damage-a history of inflammatory pathways and vascular remodeling. Vessel Plus. 2021 Mar 26;5: N-A. [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi C, Franchi T, Mathew G, et al. PRISMA 2020 statement: what’s new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int J Surg 2021; 88:105918. [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen ML, Page MJ. PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: common questions on tracking records and the flow diagram. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA. 2022 Apr 1;110(2):253. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Sun N, Zhang W, et al. The impact of uric acid on musculoskeletal diseases: clinical associations and underlying mechanisms. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2025 Feb 4; 16:1515176. [CrossRef]

- Miake J, Hisatome I, Tomita K, et al. Impact of hyper-and hypo-uricemia on kidney function. Biomedicines. 2023 Apr 24;11(5):1258. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Lozada LG, Soto V, Tapia E, et al. Role of oxidative stress in the renal abnormalities induced by experimental hyperuricemia. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2008 Oct;295(4): F1134-41.

- Sánchez-Lozada LG, Tapia E, Avila-Casado C, et al. Mild hyperuricemia induces glomerular hypertension in normal rats. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2002 Nov 1;283(5): F1105-10.

- Sanchez-Lozada LG, Tapia E, Santamaria J, et al. Mild hyperuricemia induces vasoconstriction and maintains glomerular hypertension in normal and remnant kidney rats. Kidney international. 2005 Jan 1;67(1):237-47. [CrossRef]

- Romi MM, Arfian N, Tranggono U, et al. Uric acid causes kidney injury through inducing fibroblast expansion, Endothelin-1 expression, and inflammation. BMC nephrology. 2017 Dec; 18:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Mazzali M, Kanellis J, Han L, et al. Hyperuricemia induces a primary renal arteriolopathy in rats by a blood pressure-independent mechanism. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2002 Jun 1;282(6): F991-7. [CrossRef]

- Romero F, Pérez M, Chávez M, et al. Effect of uric acid on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats–role of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology. 2009 Dec;105(6):416-24.7. [CrossRef]

- Kono H, Chen CJ, Ontiveros F, et al. Uric acid promotes an acute inflammatory response to sterile cell death in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010 Jun 1;120(6):1939-49.8.

- Rabb H, Daniels F, O'Donnell M, et al. Pathophysiological role of T lymphocytes in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2000 Sep 1;279(3): F525-31.9.

- Roncal CA, Mu W, Croker B, et al. Effect of elevated serum uric acid on cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2007 Jan;292(1), 2007, F116-22. [CrossRef]

- Perlstein TS, Gumieniak O, Hopkins PN, et al. Uric acid and the state of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in humans. Kidney international. 2004 Oct 1;66(4):1465-70.

- Jung SW, Kim SM, Kim YG, et al. Uric acid and inflammation in kidney disease. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2020. 11 May. [CrossRef]

- Gu W, Zhao J, Xu Y. Hyperuricemia-induced complications: dysfunctional macrophages serve as a potential bridge. Frontiers in Immunology. 2025 Jan 28; 16:1512093.

- Diaz-Ricart M, Torramade-Moix S, Pascual G, et al. Endothelial damage, inflammation and immunity in chronic kidney disease. Toxins. 2020 Jun 1;12(6):361. [CrossRef]

- Yuan Q, Tang B, Zhang C. Signaling pathways of chronic kidney diseases, implications for therapeutics. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2022 Jun 9;7(1):182. [CrossRef]

- Gomchok D, Ge RL, Wuren T. Platelets in renal disease. International journal of molecular sciences. 2023 Sep 29;24(19):14724. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Peng J, Wu Y, et al. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms and therapeutic targets of gout: An update. International immunopharmacology. 2023 Aug 1; 121:110466. [CrossRef]

- Kimura Y, Tsukui D, Kono H. Uric acid in inflammation and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021 Jan;22(22):12394. [CrossRef]

- Lo CW, Lii CK, Hong JJ, et al. Andrographolide inhibits IL-1β release in bone marrow-derived macrophages and monocyte infiltration in mouse knee joints induced by monosodium urate. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2021 Jan 1; 410:115341.

- Kwaifa IK, Bahari H, Yong YK, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in obesity-induced inflammation: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Biomolecules. 2020 Feb 13;10(2):291. [CrossRef]

- Hénaut L, Candellier A, Boudot C, et al. New insights into the roles of monocytes/macrophages in cardiovascular calcification associated with chronic kidney disease. Toxins. 2019 Sep 12;11(9):529. [CrossRef]

- Joo HJ, Kim GR, Choi DW, et al. Uric acid level and kidney function: a cross-sectional study of the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey (2016–2017). Scientific reports. 2020 Dec 10;10(1):21672. [CrossRef]

- San Koo B, Jeong HJ, Son CN, et al. J-shaped relationship between chronic kidney disease and serum uric acid levels: a cross-sectional study on the Korean population. Journal of rheumatic diseases. 2021 Oct 1;28(4):225-33.

- Nagore D, Candela A, Bürge M, et al. Uric acid and acute kidney injury in high-risk patients for developing acute kidney injury undergoing cardiac surgery: A prospective multicenter study. Revista Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación (English Edition). 2024 Aug 1;71(7):514-21.

- Srivastava A, Palsson R, Leaf DE, et al. Uric acid and acute kidney injury in the critically ill. Kidney medicine. 2019 Jan 1;1(1):21-30. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava A, Kaze AD, McMullan CJ, et al. Uric acid and the risks of kidney failure and death in individuals with CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2018 Mar 1;71(3):362-70. [CrossRef]

- Lee EH, Choi JH, Joung KW, et al. Relationship between serum uric acid concentration and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass surgery. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2015 Oct 1;30(10):1509-16. [CrossRef]

- Kanbay M, Yilmaz MI, Sonmez A, et al. Serum uric acid level and endothelial dysfunction in patients with nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. American journal of nephrology. 2011 Mar 8;33(4):298-304. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Meng X, Timofeeva M, et al. Serum uric acid levels and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of evidence from observational studies, randomised controlled trials, and Mendelian randomisation studies. Bmj. 2017 Jun 7;357.

- Sato Y, Feig DI, Stack AG, et al. The case for uric acid-lowering treatment in patients with hyperuricaemia and CKD. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2019 Dec;15(12):767-75. [CrossRef]

- Sah OS, Qing YX. Associations between hyperuricemia and chronic kidney disease: a review. Nephro-urology monthly. 2015 ;7(3): e27233. 23 May. [CrossRef]

- Cui D, Liu S, Tang M, et al. Phloretin ameliorates hyperuricemia-induced chronic renal dysfunction through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and uric acid reabsorption. Phytomedicine. 2020 Jan 1; 66:153111. [CrossRef]

- Han YJ, Li S. High levels of uric acid upregulate endothelin receptors: the role of MAPK pathways in an in vitro study. Archives of Medical Science. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ejaz AA, Johnson RJ, Shimada M, et al. The role of uric acid in acute kidney injury. Nephron. 2019 Apr 16;142(4):275-83.

- Wen L, Yang H, Ma L, et al. The roles of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated signaling pathways in hyperuricemic nephropathy. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2021 Mar; 476:1377-86. [CrossRef]

- Wei X, Zhang M, Huang S, et al. Hyperuricemia: A key contributor to endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases. The FASEB Journal. 2023 Jul;37(7): e23012. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Lin X, Yang X, et al. Research progress on related mechanisms of uric acid activating NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic kidney disease. Renal failure. 2022 Dec 31;44(1):615-24. [CrossRef]

- Galozzi P, Bindoli S, Luisetto R, et al. Regulation of crystal induced inflammation: current understandings and clinical implications. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2021 Jul 3;17(7), 773-87. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Chen M, Zheng J, et al. Insights into the relationship between serum uric acid and pulmonary hypertension. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2023 Nov 21;29(1):10.

- Gherghina ME, Peride I, Tiglis M, et al. Uric acid and oxidative stress—relationship with cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal impairment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022 Mar 16;23(6):3188.

- Chang HY, Lee PH, Lei CC, et al. Hyperuricemia as an independent risk factor of chronic kidney disease in middle-aged and elderly population. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2010 Jun 1;339(6):509-15. [CrossRef]

- Kawasoe S, Kubozono T, Salim AA, et al. J-shaped association between serum uric acid levels and the prevalence of a reduced kidney function: a cross-sectional study using Japanese Health Examination Data. Internal Medicine. 2024 Jun 1;63(11):1539-48. [CrossRef]

- Jiang F, Peng Y, Hong Y, et al. Correlation Between Uric Acid/High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio and Postoperative AKI in Patients with CABG. International Journal of General Medicine. 6: 2024 Dec 31 6065-74.

- Wang JJ, Chi NH, Huang TM, et al. Urinary biomarkers predict advanced acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Critical care. 1: 2018 Dec; 22 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava A, Palsson R, Leaf DE, et al. Uric acid and acute kidney injury in the critically ill. Kidney medicine. 2019 Jan 1;1(1):21-30.

- Weisman, A. Associations between allopurinol and cardiovascular and renal outcomes in diabetes. University of Toronto (Canada); 2020.

- Beberashvili I, Sinuani I, Azar A, et al. Serum uric acid as a clinically useful nutritional marker and predictor of outcome in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Nutrition. 2015 Jan 1;31(1):138-47. [CrossRef]

- Hahn K, Kanbay M, Lanaspa MA, et al. Serum uric acid and acute kidney injury: a mini review. Journal of advanced research. 2017 Sep 1;8(5):529-36. [CrossRef]

- Giordano C, Karasik O, King-Morris K, et al. Uric acid as a marker of kidney disease: review of the current literature. Disease markers. 2015;2015(1):382918. [CrossRef]

| № | Authors (years) | Title | Study type | Study subject | Duration | Pathophysiological implications | |

| Animal experimental | |||||||

| 1 | Sa´nchez-Lozada LG., et al 2008 [11] | Role of oxidative stress in the renal abnormalities induced by experimental hyperuricemia | Experimental (animal studies) | Three groups of male Sprague-Dawley rats | 5 weeks | These findings indicate that hyperuricemia-induced renal damage in rats is primarily due to impaired autoregulation in preglomerular vessels, leading to the direct transmission of systemic hypertension to glomerular capillaries. This dysfunction is associated with UA-induced microvascular injury in the afferent arteriole. | |

| 2 | Sa´nchez-Lozada LG., et al 2002 [12] | Mild hyperuricemia induces glomerular hypertension in normal rats | Experimental (animal studies) | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | 2 and 5 weeks | The relevance of these findings to human disease remains uncertain, as extrapolating from animal models requires caution. However, chronic hyperuricemia has been linked to renal disease in gout patients and is a predictor of IgA nephropathy progression and renal insufficiency in healthy individuals. Additionally, it has been reported to worsen experimental cyclosporin nephropathy. | |

| 3 | Sa´nchez-Lozada LG., et al 2005 [13] | Mild hyperuricemia induces vasoconstriction and maintains glomerular hypertension in normal and remnant kidney rats | Experimental (animal studies) | Male 300 to 350 g Sprague-Dawley rats | 5 weeks | These results suggest that in normal rats, a slight increase in serum uric acid leads to preglomerular arteriolopathy, causing systemic hypertension to be transmitted to the glomerular capillaries. This, along with increased efferent resistance from hyperuricemia, exacerbates glomerular hypertension. | |

| 4 | Romi MM et al. 2017 [14] | Uric acid causes kidney injury through inducing fibroblast expansion, Endothelin-1 expression, and inflammation | Experimental (animal studies) | Swiss background mice (4 months old, 30-35 g, n = 6-7 each group). | 14 days | These findings indicate that elevated uric acid levels in mice are linked to increased ET-1 mRNA expression. This suggests that ET-1 may influence uric acid's role in glomerular injury and could also be regulated by uric acid, contributing to vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in human cell cultures. | |

| 5 | Mazzali M et al 2022 [15] | Hyperuricemia Induces a Primary Renal Arteriolopathy in Rats by a Blood Pressure-Independent Mechanism | Experimental (animal studies) | Male Sprague-Dawley rats, 200- 250 g (Simonsen Laboratories, Gilroy CA) | 7 weeks | Recent findings indicate that hyperuricemia induced by oxonic acid in rats worsens cyclosporine-induced microvascular and tubulointerstitial damage. This study reveals a novel finding: hyperuricemia is linked to primary arteriolopathy in the preglomerular renal vasculature. The arteriolopathy, observed consistently in afferent arterioles, is characterized by medial thickening, suggesting hypertrophic vascular remodeling. | |

| 6 | Romero F et al 2009 [16] | Effect of Uric Acid on Gentamicin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Rats – Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases 2 and 9 | Experimental (animal studies) | Male Sprague–Dawley rats (IVIC), weighing 300–400 g | 10 days | These findings suggest that uric acid administration exacerbates gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. The downregulation of MMP-9 may contribute to the increased tubulointerstitial damage observed. This may have clinical implications, as acute serum uric acid elevations occur in various pathological conditions. | |

| 7 | Kono H et al 2010 [17] | Uric acid promotes an acute inflammatory response to sterile cell death in mice | Experimental (animal studies) | Uricase Tg mouse models | Unspecified | The findings suggest that dead cells not only release stored uric acid but also produce it in large quantities after death as nucleic acids break down. In experiments with transgenic mice with reduced uric acid levels, either inside or outside the cells, we observed that uric acid depletion significantly reduces the inflammatory response triggered by cell death. | |

| 8 | Rabb H et al 2000 [18] | Pathophysiological role of T lymphocytes in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice | Experimental (animal studies) | Male mice were anesthetized with 35–50 mg/kg pentobarbital and underwent bilateral flank incisions and dissection of the renal pedicles | Unspecified | The findings indicate a more significant difference in tubular injury and serum creatinine in CD4/CD8-deficient mice at 48 hours compared to 24 hours. This suggests that the observed response is a continuous effect of T cell abrogation at both early and later stages of the inflammatory response (F. Epstein, personal communication). | |

| 9 | Roncal, CA et al 2007 [19] | Effect of elevated serum uric acid on cisplatin-induced acute renal failure | Experimental (animal studies) | Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200 –250 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) | 5 days | The findings indicate that mild hyperuricemia significantly worsens renal tubular injury and inflammation in a rat model of CP-induced acute renal failure (ARF), primarily by promoting monocyte chemokine stimulation and increasing leukocyte infiltration. | |

| Human experimental | |||||||

| 1 | Perlstein TS et al 2004 [20] | Uric acid and the state of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in humans | Experimental (human studies) | 249 Caucasian and African American | Unknown | The findings indicate that serum uric acid levels predict reduced renal vascular response to Ang II in humans, suggesting a link between uric acid and an activated intrarenal RAS. This could help explain the connection between serum uric acid levels and the risk of hypertension and nephropathy. | |

| Observational studies | |||||||

| S/No | Authors (years) | Title | Study type | Groups | Duration | Comorbidities | Pathophysiological implications |

| 1 | Joo HJ et al 2020 [31] | Uric acid level and kidney function: a cross-sectional study of the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey (2016–2017) | A cross-sectional study | 16,277 individuals (unspecified ages) | Unspecified | Unspecified | This study found a significant negative relationship between high uric acid levels and kidney function in the South Korean population, showing a dose-response link in both sexes. Higher uric acid levels were associated with a greater likelihood of impaired kidney function. |

| 2 | Koo BS, et al 2021 [32] | J-shaped Relationship Between Chronic Kidney Disease and Serum Uric Acid Levels: A Cross-sectional Study on the Korean Population | A cross-sectional study | 173,357 participants aged 40∼79 years | Unspecified | Unspecified | The study found that as uric acid levels increased, the risk of reduced renal function also increased. Additionally, for uric acid levels ≤2.0 mg/dL, the risk of reduced renal function was higher than in the reference group. |

| 3 | D. Nagore et al 2024 [33] | Uric acid and acute kidney injury in high-risk patients for developing acute kidney injury undergoing cardiac surgery | A multicentre prospective cohort study (clinical studies) | All consecutive patients aged 18 years or older with a Cleveland score ≥ 4 that underwent cardiac surgery | Unspecified | Cardiac surgery | Unlike previous studies, this multicenter cohort study of 261 high-risk cardiac surgery patients found that preoperative hyperuricemia (≥7 mg/dL) was not associated with a significantly increased risk of postoperative AKI compared to uric acid levels < 7 mg/dL. |

| 4 | Srivastava A, et al 2019 [34] | Uric Acid and Acute Kidney Injury in the Critically Ill | Prospective cohort study | 2 independent cohorts of critically ill patients: (1) 208 patients without AKI; and (2) 250 participants with AKI requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) who had not yet initiated RRT | Unspecified | Unspecified | The findings suggest that uric acid levels do not contribute to the development of AKI or mortality in ICU patients with severe AKI, conflicting with several published studies on this association. |

| 5 | Srivastava A., et al 2018 [35] | Uric Acid and the Risks of Kidney Failure and Death in Individuals With CKD | A prospective cohort study | 3939 men and women aged 21 to 74 years | Unspecified | Unspecified | This prospective study of nearly 4,000 individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) found that higher serum uric acid levels were linked to an increased risk of kidney failure in those with CKD stage 3a or earlier. Uric acid showed a ‘J-shaped’ relationship with all-cause mortality. As expected, uric acid was inversely correlated with eGFR, which strongly influenced its association with kidney failure and mortality. |

| 6 | Lee E-H, et al 2015 [36] | Relationship between Serum Uric Acid Concentration and Acute Kidney Injury after Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery | Large single-center observational study | 2,185 patients | Unknown | Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery | This study suggests that even preoperative serum uric acid levels within the normal range may be linked to an increased risk of postoperative AKI in CABG patients. The findings do not indicate a J-shaped relationship; instead, the risk of AKI appears to rise almost linearly with increasing preoperative uric acid levels. |

| 7 | Kanbay M, et all 2011 [37] | Serum Uric Acid Level and Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients with Nondiabetic Chronic Kidney Disease | Observational cohort study | 263 nondiabetic subjects with CKD and a mean eGFR of 26 ml/min/1.73 m 2 | Unspecified | Unspecified | This study found that endothelial dysfunction, assessed via FMD, was independently linked to both decreased eGFR and elevated serum uric acid levels. Reduced eGFR may contribute to the accumulation of substances like uric acid and asymmetric dimethylarginine, a uremic toxin that competes with L-arginine for endothelial NO synthase. |

| S/N | Authors (Year) | Study Type | Selection | Comparability | Outcome/Exposure | Total NOS Score | Quality |

| 1 | Joo HJ (2020) [31] | Cross-sectional | ★★ | ★ | ★★ | 5 out of 9 | Moderate |

| 2 | San Koo B (2021) [32] | Cross-sectional | ★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 6 out of 9 | Moderate |

| 3 | Nagore D (2024) [33] | Prospective cohort | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 8 out of 9 | High |

| 4 | Srivastava A (2019) [34] | Prospective cohort | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7 out of 9 | High |

| 5 | Srivastava A (2018) [35] | Prospective cohort | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7 out of 9 | High |

| 6 | Lee EH (2015) [36] | Large single-center observational | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7 out of 9 | High |

| 7 | Kanbay M (2011) [37] | Observational cohort | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7 out of 9 | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).