Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of AuAgS/rGO

2.3. Fabrication of FTO by Prepared Particles

2.4. Diazinon and Ethion Detection

2.5. Characterization of AuAgS / rGO Nanoparticles

2.6. Synthesis and Modification of Mn-CdO/RGO Composite Electrode

2.7. Diazinon Detection with MnCdO/rGO Electrode

2.8. Characterization of MnCdO / rGO Nanoparticles

3. Results and Discussion

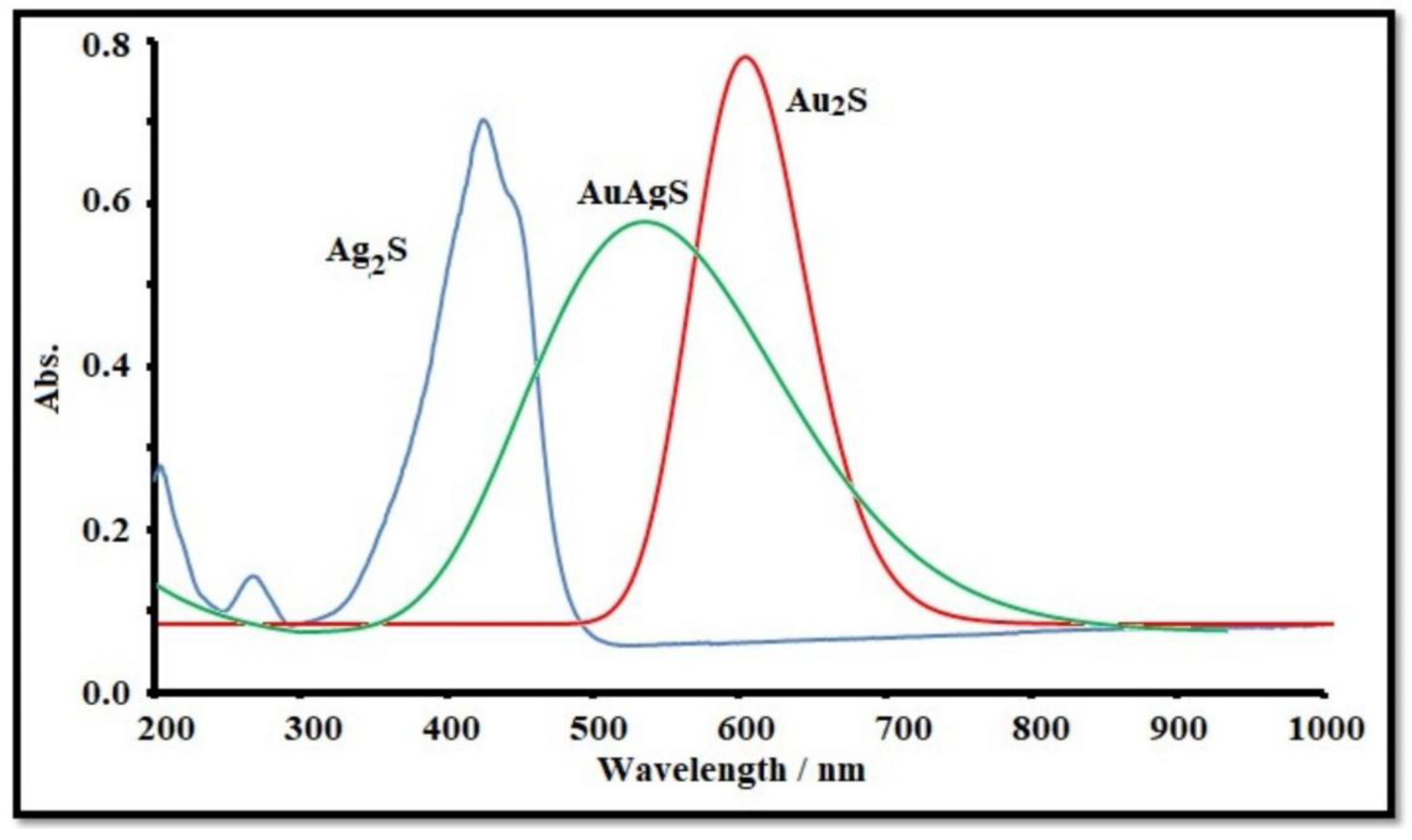

3.1. Characterization of AuAgS Nanoparticles

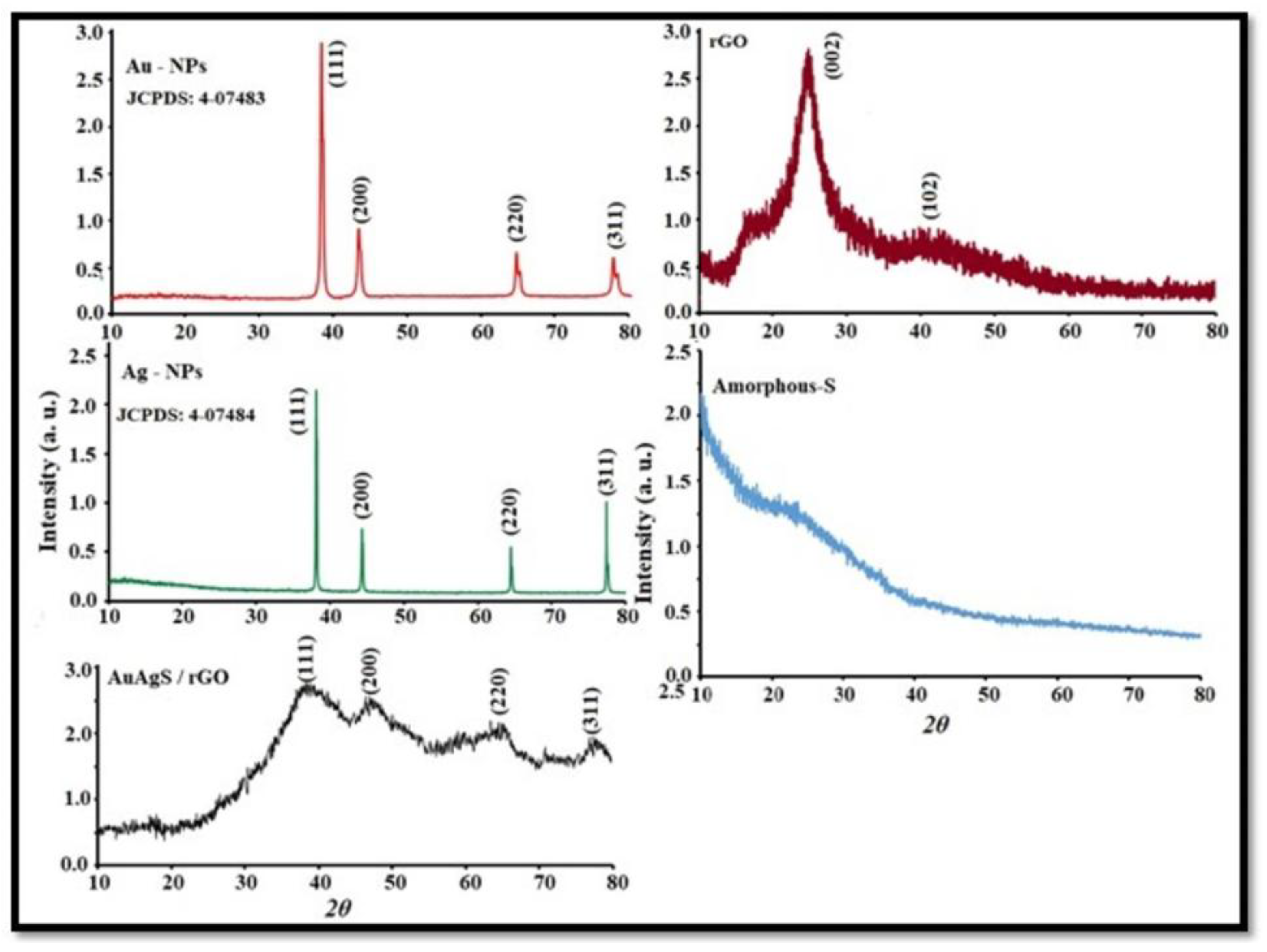

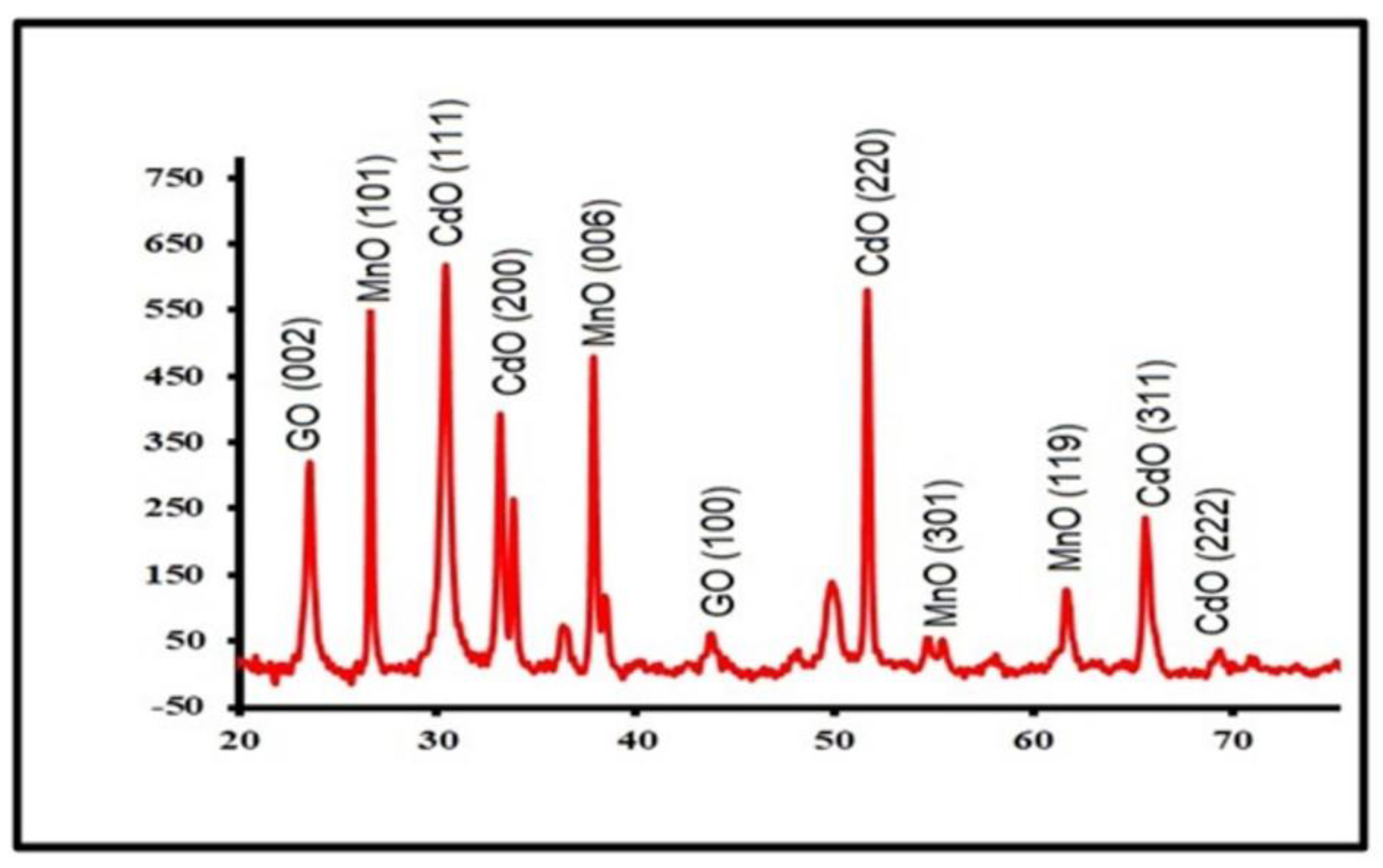

3.2. XRD

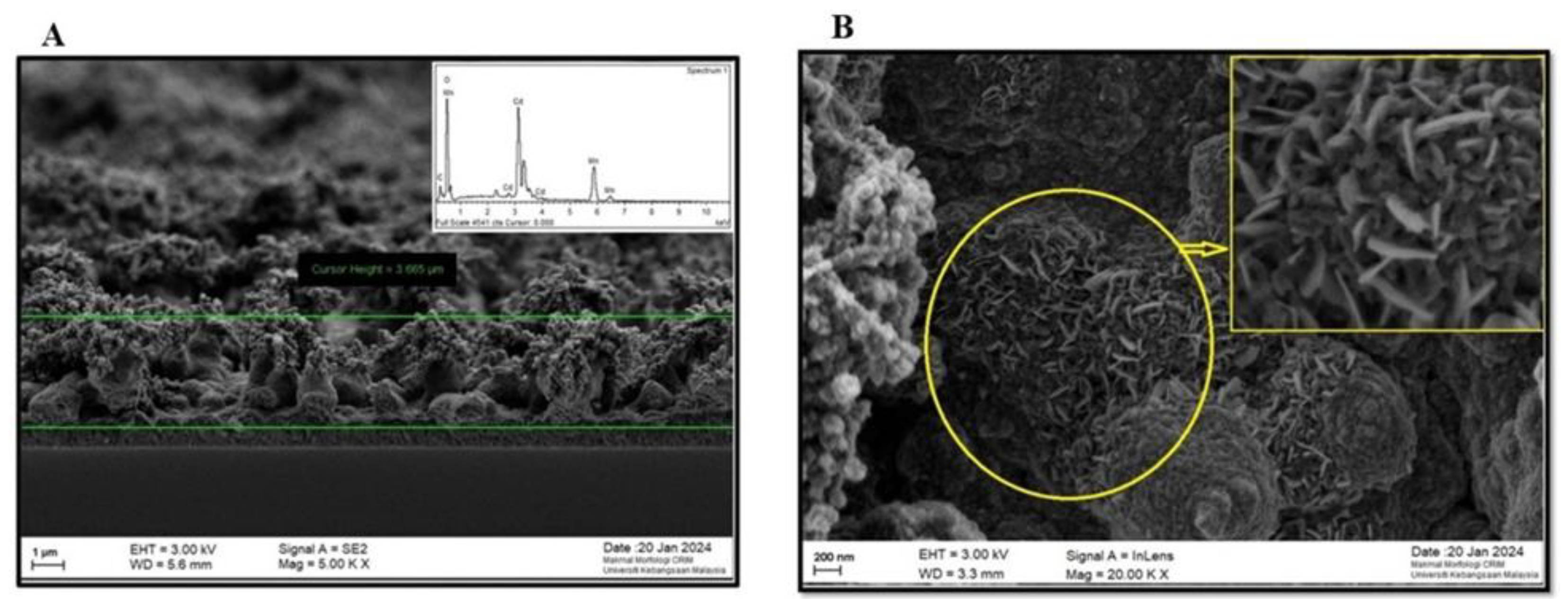

3.3. TEM and FESEM/EDX studies

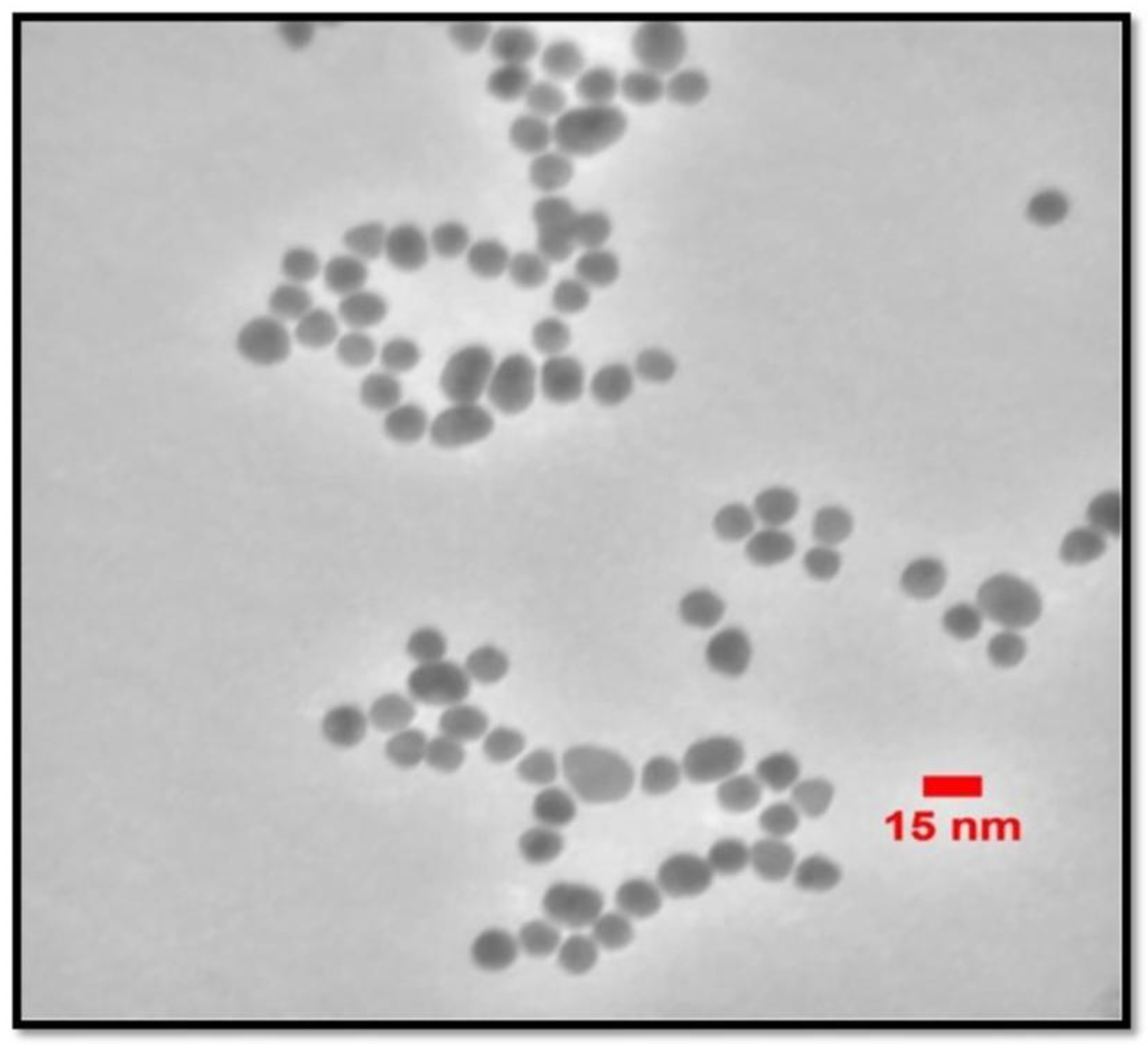

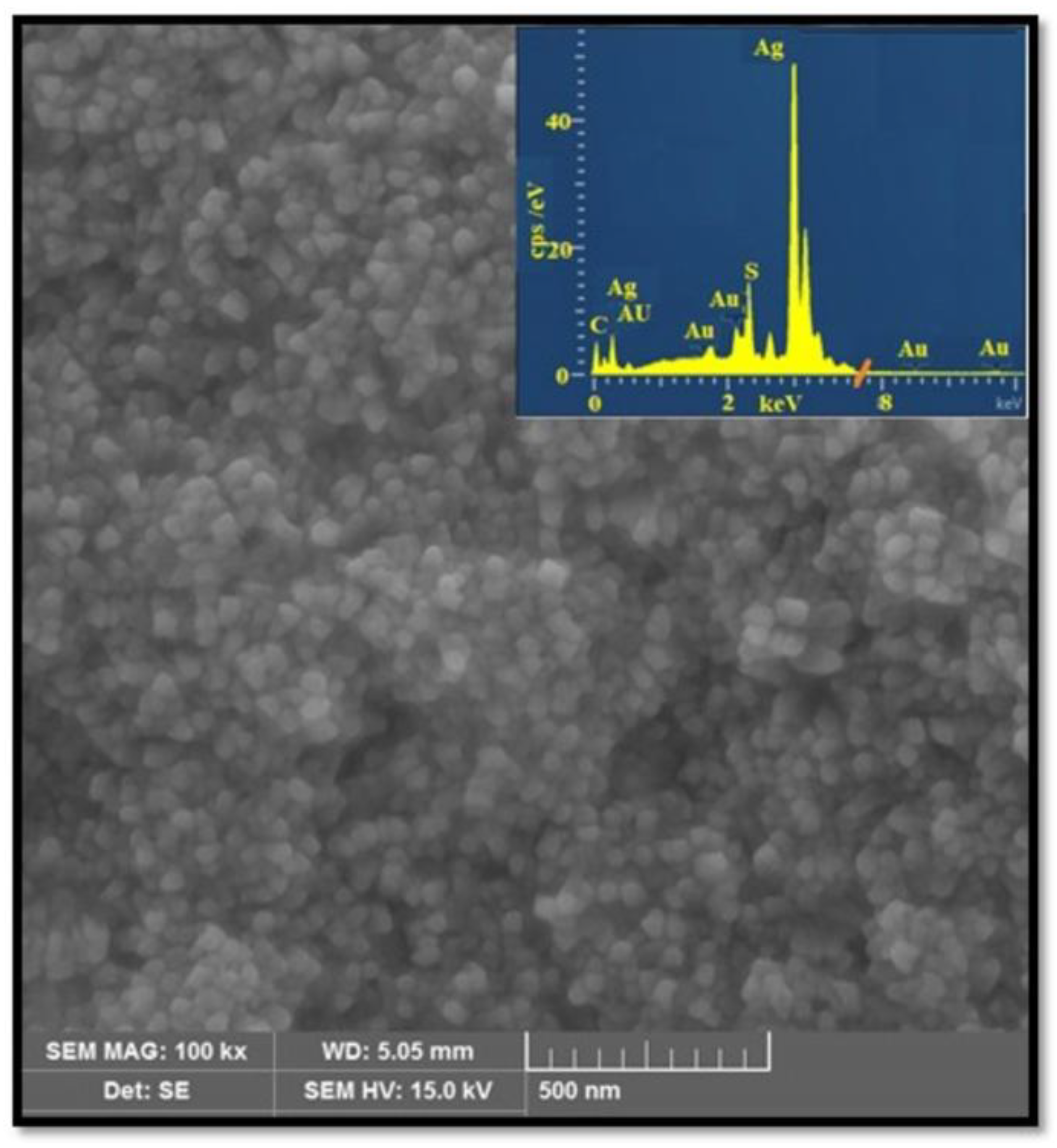

3.3.1. TEM and FESEM/EDX Analysis of AuAgS/rGO Nanoparticles

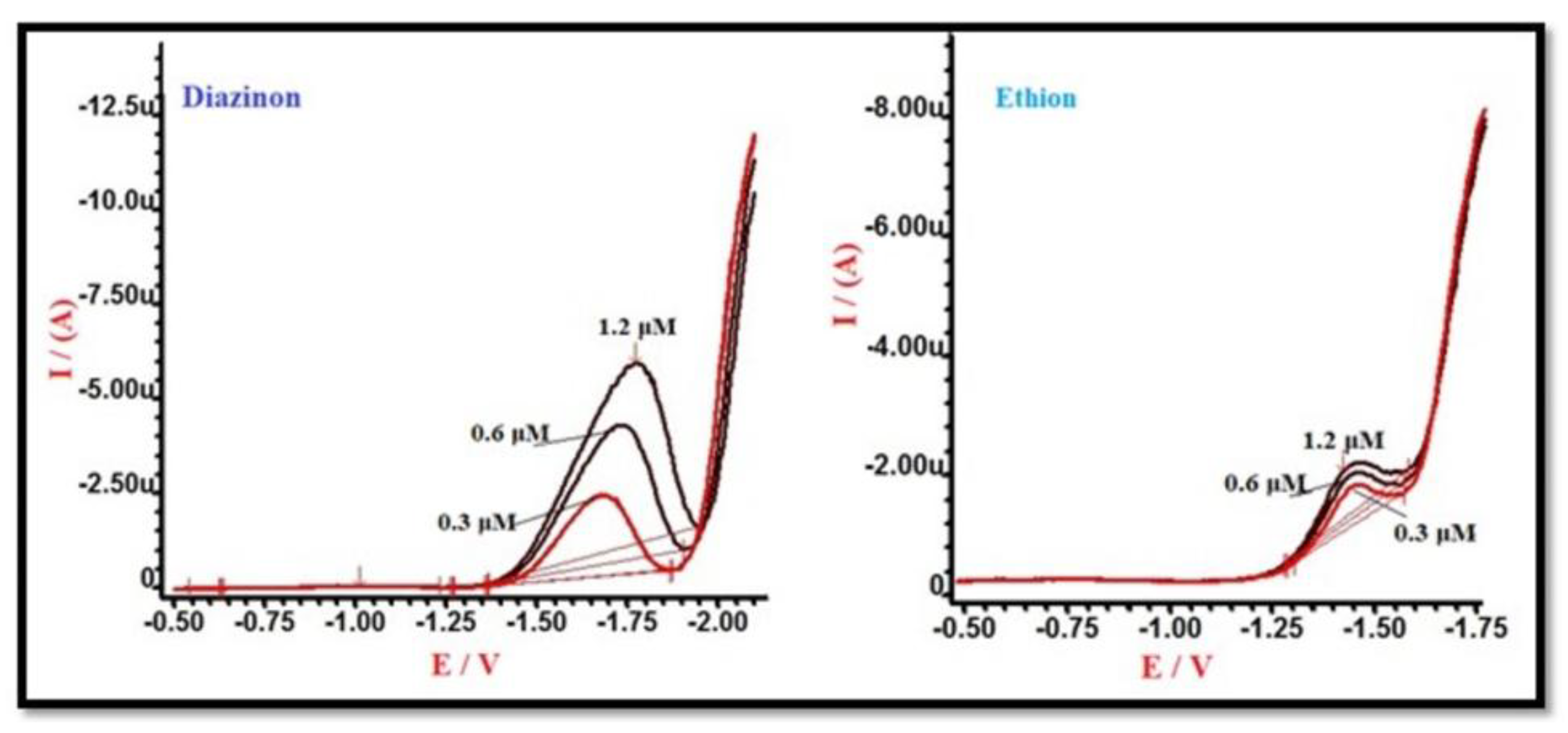

3.4. Electrochemical Detection of Organophosphate Pesticides

3.5. DPV Technique: Sensitivity and Linearity

3.6. Advantages of DPV

3.7. Comparative Performance

3.8. Characterization and Performance of MnCdO/rGO Sensor

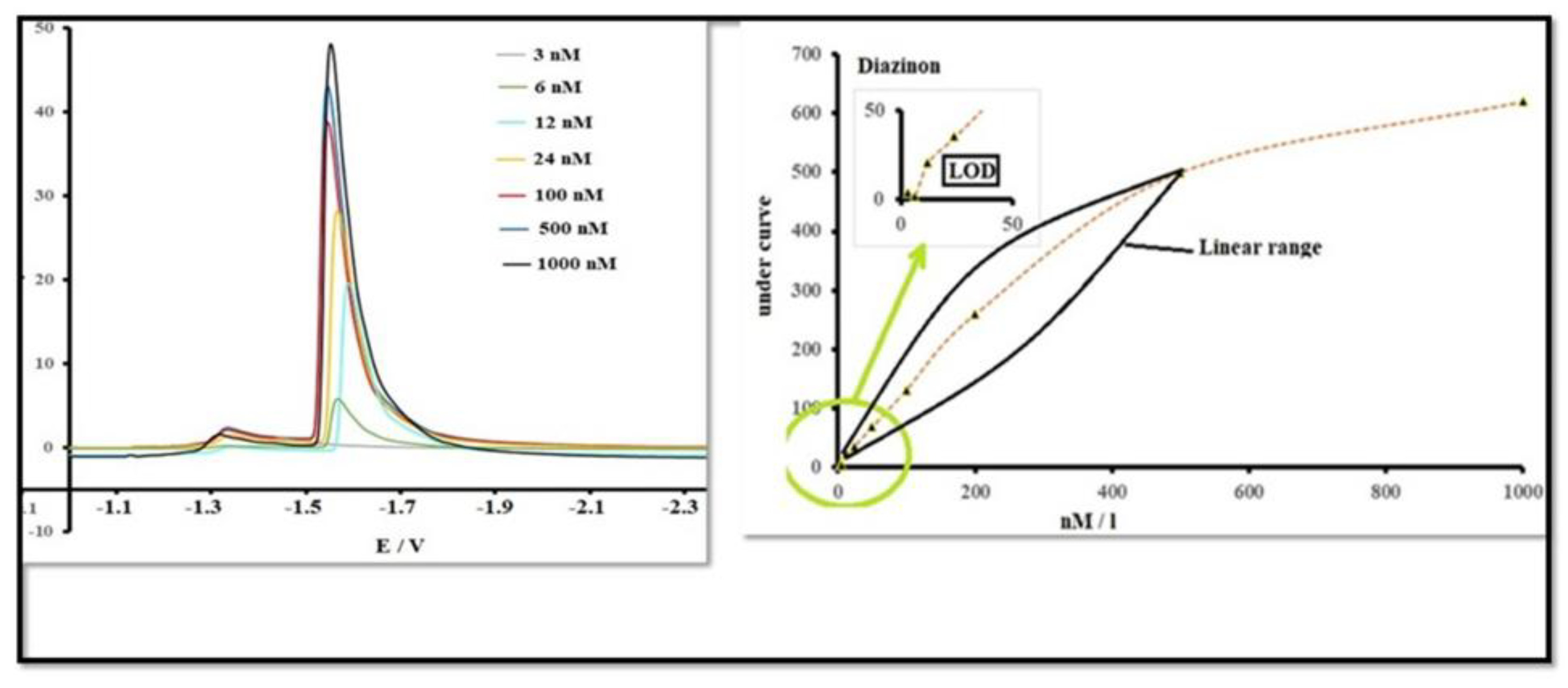

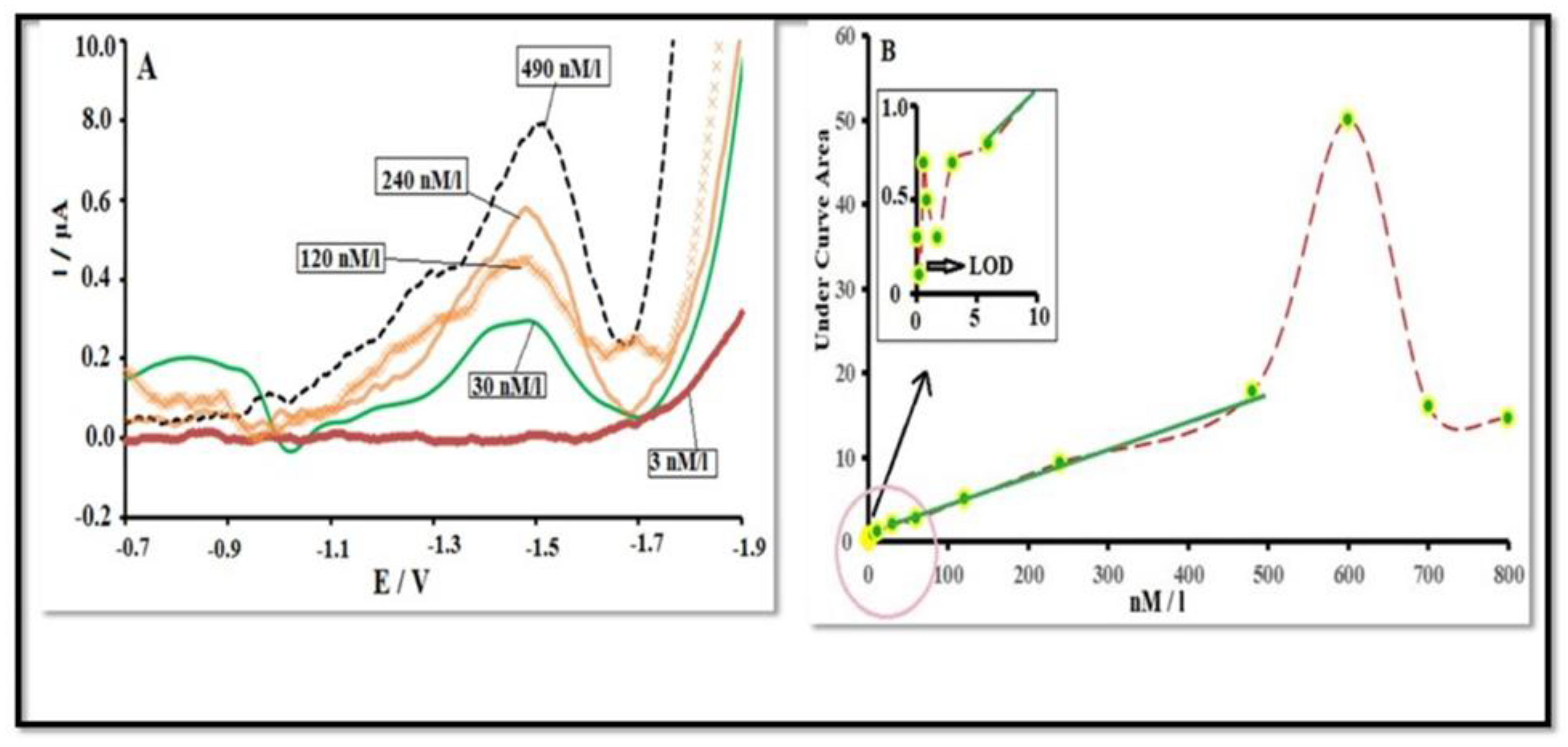

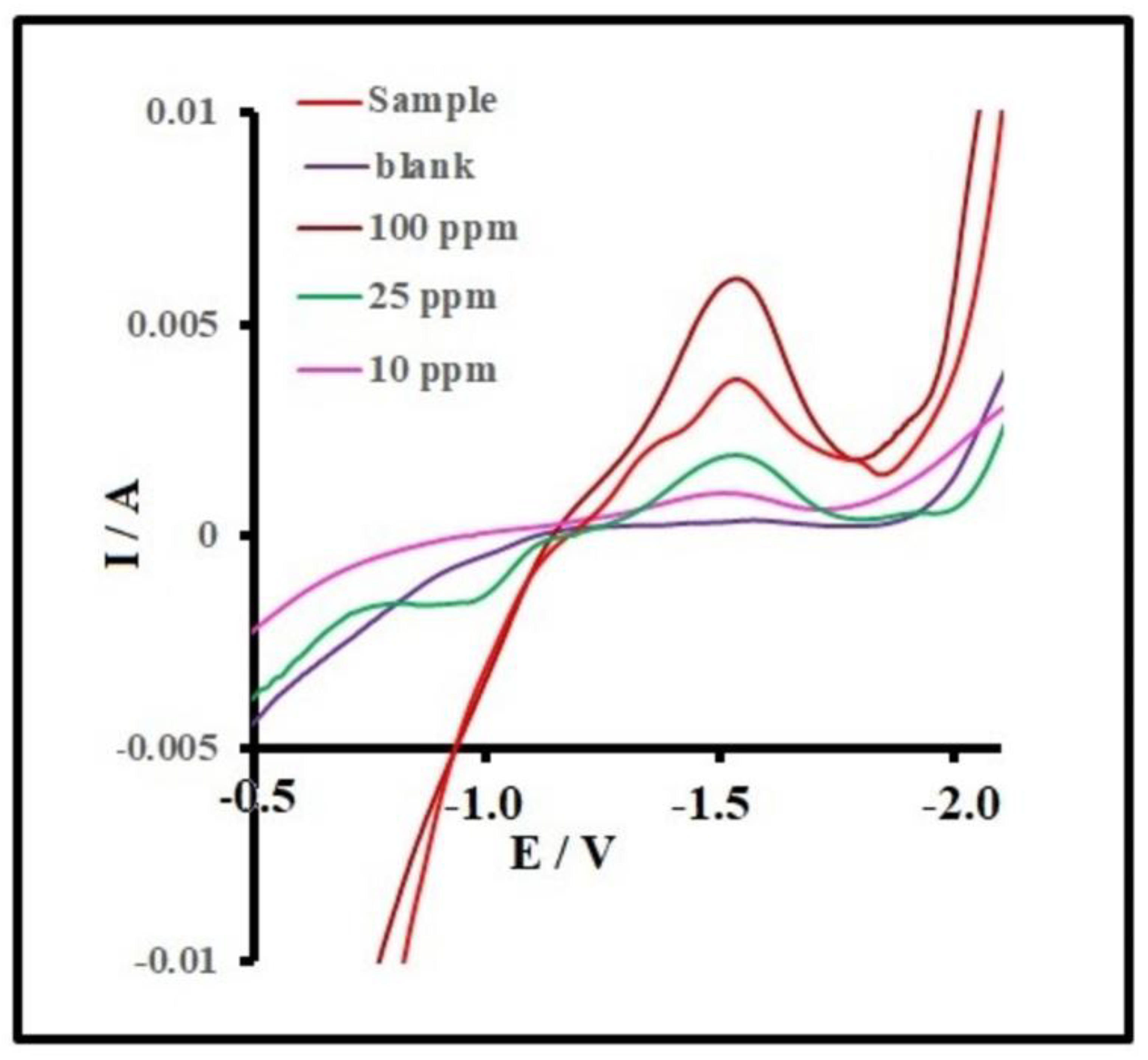

3.9. DPV Detection of Diazinon with MnCdO/rGO Electrode

3.10. Limit of Detection (LOD) and Linear Range

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data availability

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Rgo | reduced graphene oxide |

| DPV | Differential pulse voltammetry |

| FTO | Fluorine-doped tin oxide |

| OPPs | Organophosphorus pesticides |

| NMS | Noble metal sulfides |

| Na₂S | Sodium Sulfide |

| FESEM | Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| CV | Cyclic Voltammetry |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| KCl | Potassium chloride |

| SCE | Saturated calomel reference electrode |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

References

- Jayaraj, R.; Megha, P.; Sreedev, P. Organochlorine pesticides, their toxic effects on living organisms and their fate in the environment. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2016, 9, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, C.H.; Lavanya, C.; Akash, S.; Shwetharani, R.; Surareungcahi, W.; Balakrishna, R.G. Nanomaterials for organophosphate sensing: present and future perspective. In: Sensing of Deadly Toxic Chemical Warfare Agents, Nerve Agent Simulants, and their Toxicological Aspects. Elsevier, 2023, pp. 183–202.

- Pathiraja, G.; Bonner, C.D.; Obare, S.O. Recent advances of enzyme-free electrochemical sensors for flexible electronics in the detection of organophosphorus compounds: a review. Sensors. 2023, 23, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, A.E.; Oreba, R.; Elshafey, R. Molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor for the detection of organophosphorus pesticide profenofos. Electroanalysis. 2021, 33, 1945–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranveer, S.A.; Harshitha, C.; Dasriya, V.; Tehri, N.; Kumar, N.; Raghu, H. Assessment of developed paper strip-based sensor with pesticide residues in different dairy environmental samples. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghris, S.; Alaoui, O.T.; Laghrib, F.; Farahi, A.; Bakasse, M.; Saqrane, S.; Lahrich, S.; El Mhammedi, M. Extraction and determination of flubendiamide insecticide in food samples: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosello-Marquez, G.; Fernández-Domene, R.M.; Garcia-Anton, J. Organophosphorus pesticides (chlorfenvinphos, phosmet and fenamiphos) photoelectrodegradation by using WO3 nanostructures as photoanode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 894, 115366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Li, F. Two-dimensional MnO2 nanozyme-mediated homogeneous electrochemical detection of organophosphate pesticides without the interference of H2O2 and color. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 4084–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, T.F.; Wan, Y.W.; Chen, S.Y. Gold nanoparticles-carbon nanotubes modified sensor for electrochemical determination of organophosphate pesticides. Microchim. Acta. 2009, 165, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.H.; Kim, S.H.; Jang, S.; Lim, J.E.; Chang, H.; Kong, K.-j.; Myung, S.; Park, J.K. Synthesis of silver sulfide nanoparticles and their photodetector applications. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 28447–28452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdinasab, M.; Daneshi, M.; Marty, J.L. Recent developments in non-enzymatic (bio) sensors for detection of pesticide residues: Focusing on antibody, aptamer and molecularly imprinted polymer. Talanta. 2021, 232, 122397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gu, C.; Wu, L.; Tan, W.; Shang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Ma, J. Recent advances in carbon dots for electrochemical sensing and biosensing: a systematic review. Microchem. J. 2024, 111687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhao, S.; Lv, Y.; Chen, F.; Fu, L. Acid red dyes and the role of electrochemical sensors in their determination. Microchem. J. 2024, 111705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Xie, S.; Tan, R. Sythesis, Modification, and Biosensing Characteristics of Au2S/AuAgS-Coated Gold Nanorods. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 530631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohrasbi Nejad, A. Electrochemical strategies for detection of diazinon. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2022, 12, 1041–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Engelman, B.J.; Haywood, T.L.; Blok, N.B.; Beaudoin, D.S.; Obare, S.O. Dual fluorescence and electrochemical detection of the organophosphorus pesticides—ethion, malathion and fenthion. Talanta. 2011, 87, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, N.; Tan, R.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, H.; Chang, G.; He, Y. A novel electrochemical sensor via Zr-based metal organic framework–graphene for pesticide detection. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 19060–19074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, D.; González-García, M.B.; Hernández-Santos, D.; Fanjul-Bolado, P. Detection of dithiocarbamate, chloronicotinyl and organophosphate pesticides by electrochemical activation of SERS features of screen-printed electrodes. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 248, 119174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Hasnat, M.A. Recent advancements in non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor development for the detection of organophosphorus pesticides in food and environment. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e19299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, A.; Malode, S.J.; Alshehri, M.A.; Shetti, N.P. Recent advances in the development of electrochemical sensors for detecting pesticides. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 144, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, D.; Xu, X.; Ying, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; Wang, J. Immunosensors for detection of pesticide residues. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 23, 1577–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Li, S.-P.; Lisak, G. Advanced sensing technologies of phenolic compounds for pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 179, 112913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedeen, M.Z.; Sharma, M.; Kushwaha, H.S.; Gupta, R. Sensitive enzyme-free electrochemical sensors for the detection of pesticide residues in food and water. TrAC Trend. Anal. Chem. 2024, 176, 117729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batvani, N.; Alimohammadi, S.; Kiani, M.A. Nonenzymatic glucose sensor design based on carbon fiber ultra-microelectrode: Controlled with a manual micro adjuster. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2022, 1209, 339845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, W. Recent advances in perovskite oxides for non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2023, 1251, 341007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamiglio, V.; Arduini, F.; Palleschi, G.; Rea, G. Biosensing technology for sustainable food safety. TrAC Trend. Anal. Chem. 2014, 62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Ding, X.; Zhao, R.; Huang, T.; Lan, L.; Nasry, A.A.N.B.; Liu, S. Effect of starvation time on NO and N2O production during heterotrophic denitrification with nitrite and glucose shock loading. Process Biochem. 2019, 86, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Wang, M.; Luo, M.; Yu, N.; Xiong, H.; Peng, H. A nanowell-based molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor for highly sensitive and selective detection of 17β-estradiol in food samples. Food Chem. 2019, 297, 124968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geto, A.; Noori, J.S.; Mortensen, J.; Svendsen, W.E.; Dimaki, M. Electrochemical determination of bentazone using simple screen-printed carbon electrodes. Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Taneja, P.; Yadav, L.; Sharma, P.; Janu, V.C.; Gupta, R. Current insights into the implementation of electrochemical sensors for comprehensive detection and analysis of radionuclides. TrAC Trend. Anal. Chem. 2024, 117845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, P.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. A novel molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor based on graphene quantum dots coated on hollow nickel nanospheres with high sensitivity and selectivity for the rapid determination of bisphenol S. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 100, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, H.; Su, X. Review of optical sensors for pesticides. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 103, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, W.; Ju, H. Rapid detection of pesticide residues using a silver nanoparticles coated glass bead as nonplanar substrate for SERS sensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 287, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, R.; Jin, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z. Recent advances and future prospects in molecularly imprinted polymers-based electrochemical biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 100, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Jia, M.; Zhao, H.; Kang, L.; Shi, L.; Zhou, L.; Kong, W. Molecularly imprinted polymer-based optical sensors for pesticides in foods: Recent advances and future trends. Trend. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimnejad, M.A.; bdulkareem, R.A.; Najafpour, G. Determination of Diazinon in fruit samples using electrochemical sensor based on carbon nanotubes modified carbon paste electrode. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Su, L.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Xu, S.; Qian, L.; Yang, B. Non-enzymatic glucose sensor based on micro-/nanostructured Cu/Ni deposited on graphene sheets. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 838, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglione, A.; Raucci, A.; Mancini, M.; Gioia, V.; Frugis, A.; Cinti, S. An electrochemical biosensor for on-glove application: Organophosphorus pesticide detection directly on fruit peels. Talanta. 2025, 283, 127093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.A.; Demirtaş, O.Ö.; Bek, A.; Bhatti, A.S.; Ahmed, W. Facile fabrication of Au-Ag alloy nanoparticles on filter paper: Application in SERS based swab detection and multiplexing. Vib. Spectrosc. 2022, 120, 103359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Sepehrizadeh, Z.; Ebrahim-Habibi, A.; Shahverdi, A.R.; Faramarzi, M.A.; Setayesh, N. Enhancing activity and thermostability of lipase A from Serratia marcescens by site-directed mutagenesis. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2016, 93, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoun, O.; Lazarević-Pašti, T.; Pašti, I.; Nasraoui, S.; Talbi, M.; Brahem, A.; Adiraju, A.; Sheremet, E.; Rodriguez, R.D.; Ben Ali, M. A review of nanocomposite-modified electrochemical sensors for water quality monitoring. Sensors, 2021, 21, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, A.; Vashishth, R.; Singh, S.; Surendran, U.; James, A.; Chellam, P.V. Biosensors for detection of organophosphate pesticides: Current technologies and future directives. Microchem. J. 2022, 178, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehani, N.; Dzyadevych, S.V.; Kherrat, R.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.J. Sensitive impedimetric biosensor for direct detection of diazinon based on lipases. Front. Chem. 2014, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, M.H.; Kadam, U.S.; Trinh, K.H.; Cho, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Kang, C.H.; Kim, S.H.; Chung, W.S.; et al. Engineering novel aptameric fluorescent biosensors for analysis of the neurotoxic environmental contaminant insecticide diazinon from real vegetable and fruit samples. Front. Biosci.-Landmark. 2022, 27, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Huang, X.; Peng, C.; Sun, F. Highly sensitive fluorescence detection of three organophosphorus pesticides based on highly bright DNA-templated silver nanoclusters. Biosensors, 2023, 13, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parham, H.; Saeed, S. Resonance Rayleigh scattering method for determination of ethion using silver nanoparticles as probe. Talanta. 2015, 131, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, E.; Kamel, M.S.; Hassan, H.N.; Abdel-Gawad, H.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Performance of a portable biosensor for the analysis of ethion residues. Talanta 2014, 119, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanish, R.P. Sittig’s handbook of pesticides and agricultural chemicals, 2nd ed.; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 332–382. [Google Scholar]

| Sensor Type | Recognition Element | Detection Method | LOD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impedimetric Biosensor | Lipase from Candida Rugosa (CRL) | EIS | 10 Nm/L | 43 |

| Impedimetric Biosensor | Lipase from Porcine Pancreas (PPL) | EIS | 0.1 µM/L | 43 |

| Aptamer-based Fluorescent Biosensor | ssDNA Aptamer (DIAZ-02, DIAZ-03) | Fluorescence | 148 Nm/L (stated as ppb level) | 44 |

| Sensor Type | Recognition Element | Detection Method | LOD | Reference |

| Fluorescence Biosensor | DNA-templated Silver Nanoclusters (DNA-Ag NCs) | Fluorescence Quenching | 30 ng/mL | 45 |

| Resonance Rayleigh Scattering (RRS) Sensor | Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Resonance Rayleigh Scattering Quenching | 3.7 µg/L (which is ~3.7 ng/mL) | 46 |

| Screen-Printed Potentiometric Sensor | multi-walled carbon nanotube–polyvinyl chloride (MWNT–PVC) | Butyrylcholinesterase enzyme inhibition by Ethion | 22.0 ng/mL | 47 |

| Sensor Type | Recognition Element | Detection Method | LOD | Reference |

| Fluorescence Biosensor | DNA-templated Silver Nanoclusters (DNA-Ag NCs) | Fluorescence Quenching | 30 ng/mL | 45 |

| Resonance Rayleigh Scattering (RRS) Sensor | Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Resonance Rayleigh Scattering Quenching | 3.7 µg/L (which is ~3.7 ng/mL) | 46 |

| Screen-Printed Potentiometric Sensor | multi-walled carbon nanotube–polyvinyl chloride (MWNT–PVC) | Butyrylcholinesterase enzyme inhibition by Ethion | 22.0 ng/mL | 47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).