Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

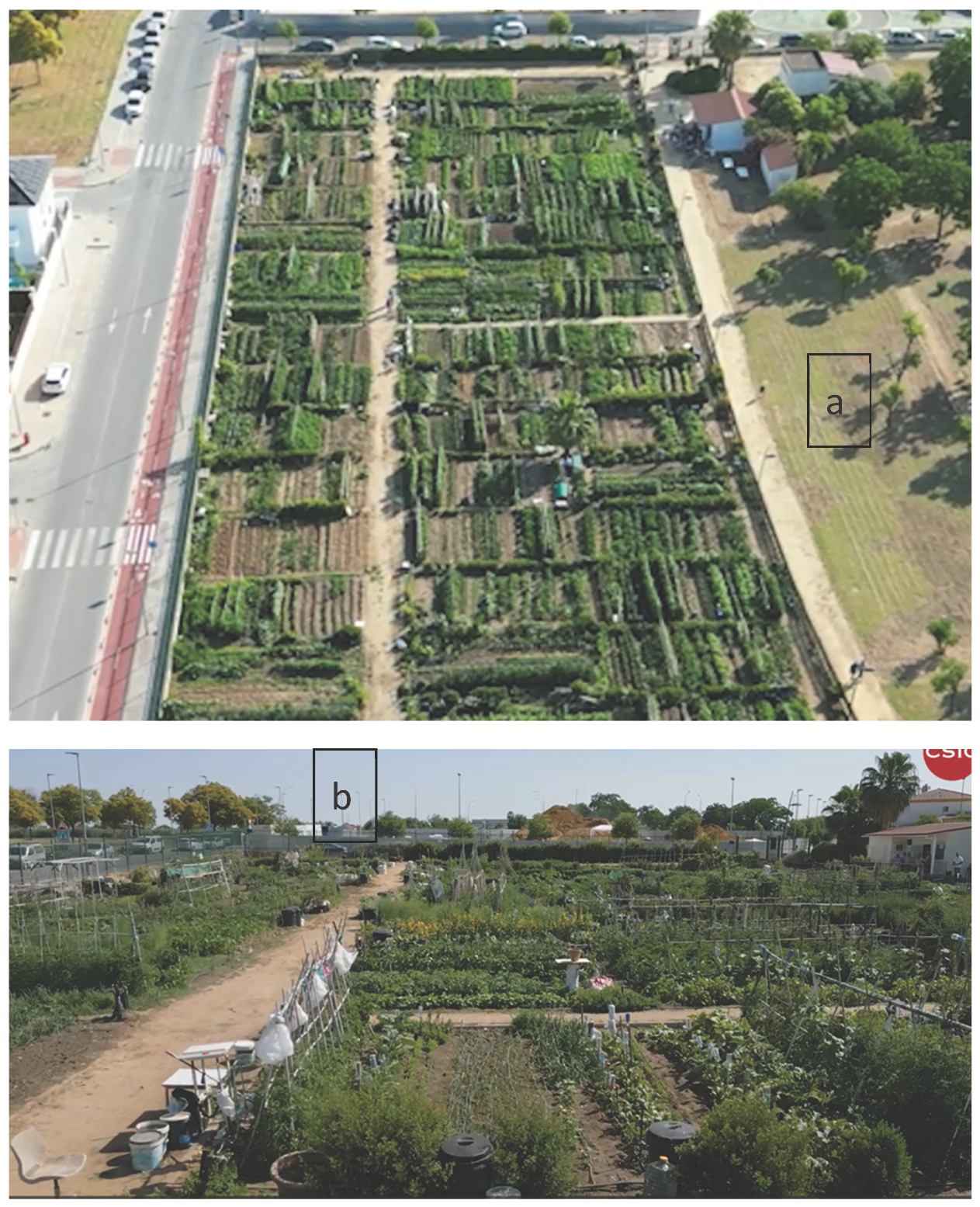

2.1. Study Site and Soil Sampling

2.2. Soil and Organic Amendment Analyses

2.3. Pollution Indices

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the Performance of the X-Ray Fluorescence Instrument

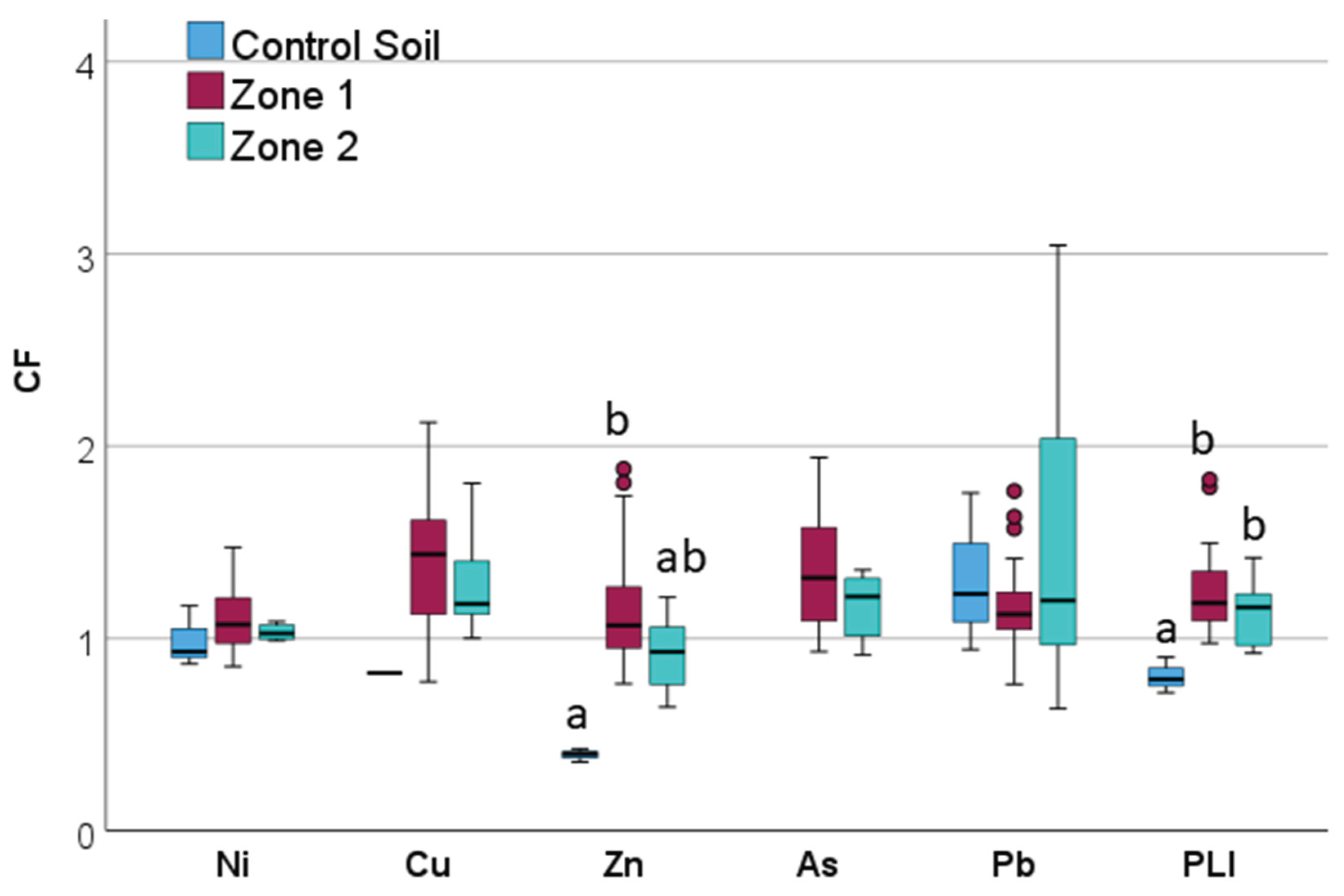

3.2. Element Concentration and Inter-Plot Variability

3.3. Composition of Manures

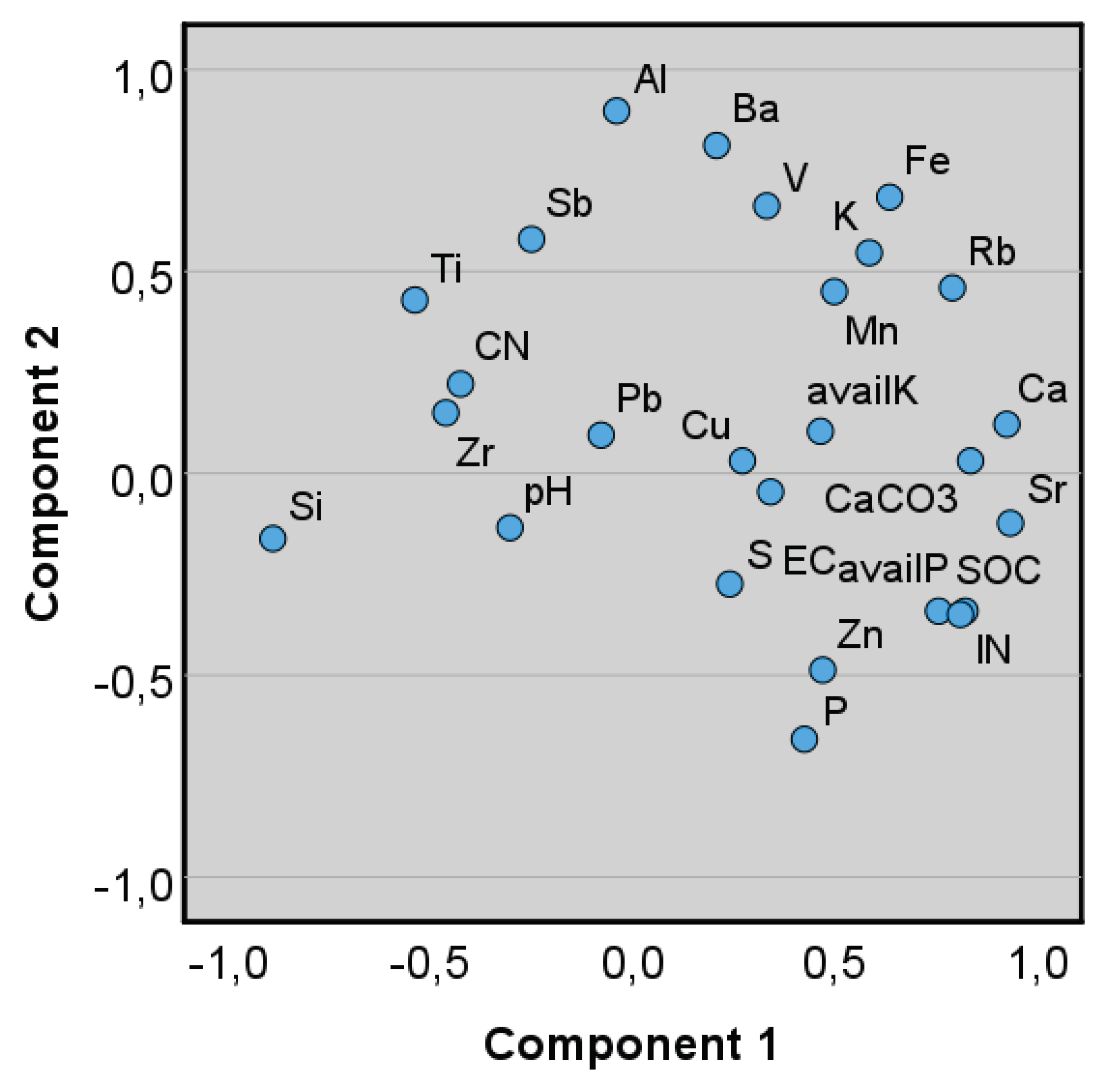

3.4. Factor Analysis

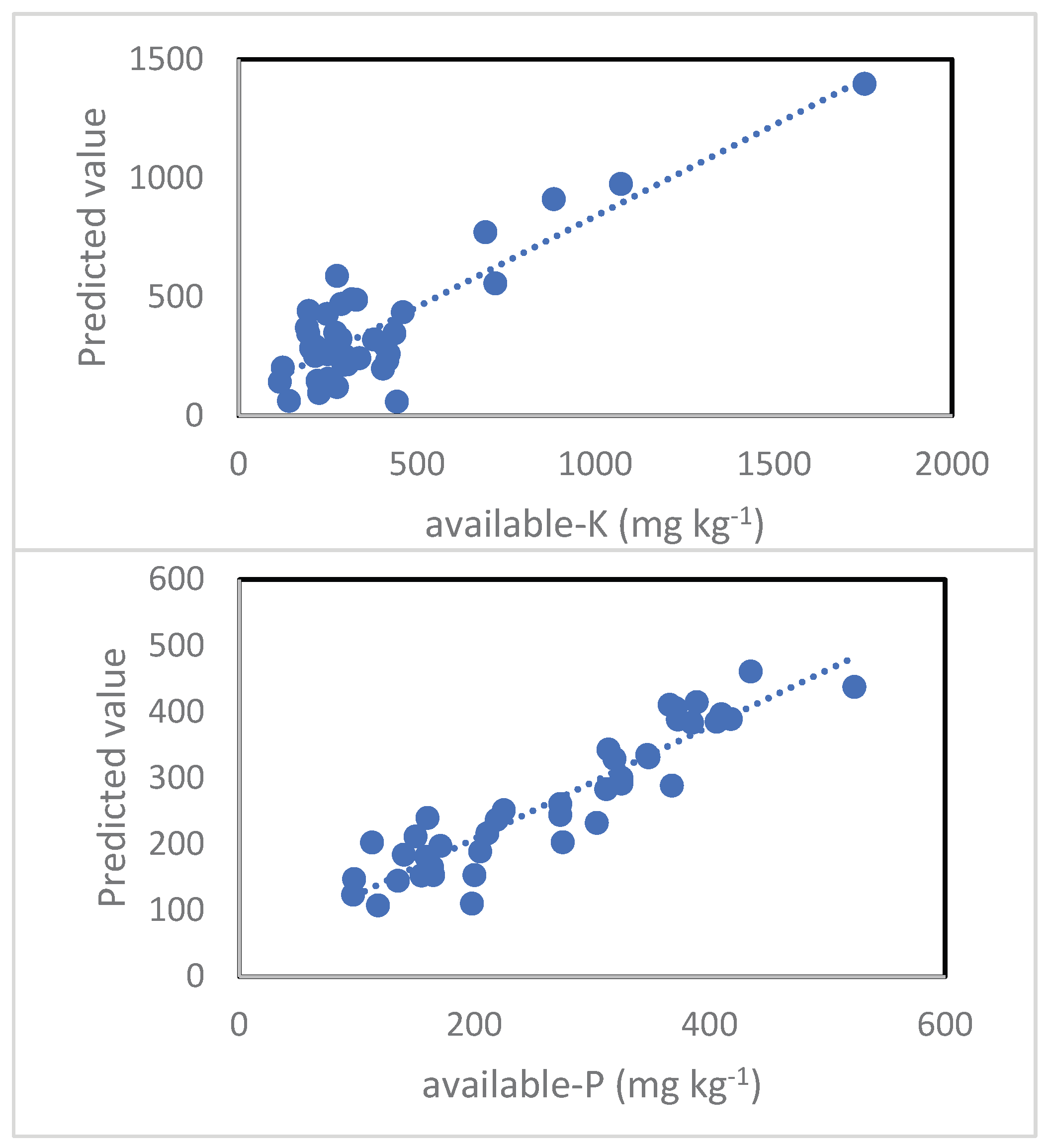

3.5. Prediction of available-K and available-P

3.6. Intra-Plot Variability

4. Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of the Performance of the X-Ray Fluorescence Instrument

4.2. Variability of Elements in the Soil of the Plots

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UA | Urban and peri-urban agriculture |

| pXRF | portable X-ray fluorescence |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Fei, S.; Wu, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; Wang, N. Technological Innovations in Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture: Pathways to Sustainable Food Systems in Metropolises. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A.; Hopeward, J.; Myers, B. Modelling the Benefits and Impacts of Urban Agriculture: Employment, Economy of Scale and Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, R.; Takahashi, H.; Kato, T.; Sila, D.; Koaze, H.; Tani, M. Peri-urban agricultural management impacts the soil nutrient status of Nitisols in the central highlands of Kenya. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 71(5), 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Hartung, J.; Zikeli, S.; et al. Status quo of fertilization strategies and nutrient farm gate budgets on stockless organic vegetable farms in Germany. Org. Agr. 2024, 14, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, M.; Oelofse, M.; Müller-Stöver, D.; et al. Sustainable growth of organic farming in the EU requires a rethink of nutrient supply. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 2024, 129, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badagliacca, G.; Testa, G.; La Malfa, S.G.; Cafaro, V.; Lo Presti, E.; Monti, M. Organic Fertilizers and Bio-Waste for Sustainable Soil Management to Support Crops and Control Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Mediterranean Agroecosystems: A Review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygens, D.; Orveillon, G.; Lugato, E.; Tavazzi, S.; Comero, S.; Jones, A.; Gawlik, B.; Saveyn, HGM. Technical proposals for the safe use of processed manure above the threshold established for Nitrate Vulnerable Zones by the Nitrates Directive (91/676/EEC), EUR 30363 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soils and food sufficiency. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Council Directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 concerning the protection of waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources. Official Journal L 375 , 31/12/1991, 0001 – 0008.

- Orsini, F.; Pennisi, G.; Michelon, N.; Minelli, A.; Bazzocchi, G.; Gianquinto, G. Features and Functions of Multifunctional Urban Agriculture in the Global North: A Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 562513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meharg, A.A. Perspective: City farming needs monitoring. Nature 2016, 531, S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini-Oliva, S.; López-Núñez, R. Potential Toxic Elements Accumulation in Several Food Species Grown in Urban and Rural Gardens Subjected to Different Conditions. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini-Oliva, S.; López-Núñez, R. Is it healthy urban agriculture? Human exposure to potentially toxic elements in urban gardens from Andalusia, Spain. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2024, 31, 36626–36642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Contamination of soils in domestic gardens and allotments: A brief overview. L. Contam. Reclam. 2004, 12, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidar, G.; Pelfrêne, A.; Schwartz, C.; Waterlot, C.; Sahmer, K.; Maro, F.; Doua, F. Urban kitchen gardens: effect of the soil contamination and parameters on the trace element accumulation in vegetables – a review. Sci Total Environ 2020, 738, 139569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Declet, A.; Rodinò, M.T.; Praticò, S.; Gelsomino, A.; Rombolà, A.D.; Modica, G.; Messina, G. Spatial and Temporal Variability of C Stocks and Fertility Levels After Repeated Compost Additions: A Case Study in a Converted Mediterranean Perennial Cropland. Soil Syst. 2025, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wheeler, D.; Bell, J.; Wilding, L. Assessment of soil spatial variability at multiple scales. Ecol. Model. 2005, 182, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechet, B.; Joimel, S.; Jean-Soro, L.; et al. Spatial variability of trace elements in allotment gardens of four European cities: assessments at city, garden, and plot scale. J Soil. Sediment. 2018, 18, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, J.C.; Van Halen, D.; Speer, J.; et al. Soil Lead Testing at a High Spatial Resolution in an Urban Community Garden: A Case Study in Relic Lead in Terre Haute, Indiana. J Environ Health. 2016, 79, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bugdalski, L.; Lemke, L.D.; McElmurry, S.P. Spatial Variation of Soil Lead in an Urban Community Garden: Implications for Risk-Based Sampling. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romzaykina, O.N.; Slukovskaya, M.V.; Paltseva, A.A.; et al. Rapid assessment of soil contamination by potentially toxic metals in the green spaces of Moscow megalopolis using the portable X-ray analyzer. J Soil. Sediment. 2025, 25, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.; Hartemink, A.E. Chapter Two - Sampling soils in urban ecosystems—A review, In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Eds.; Academic Press, 2025; Volume 189, pp. 63-136. [CrossRef]

- Sanz de Galdeano, C.; Vera, J.A. Stratigraphic record and palaeogeographical context of the Neogene basins in the Betic Cordillera, Spain. Basin Res. 1992, 4, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoral E, Abad M. 2008. Geología de la Cuenca del Guadalquivir. In Geología de Huelva, Lugares de interés geológico, 2nd ed.; Universidad de Huelva: Huelva, Spain, 2009; pp. 20–2.

- USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Method 6200: Field Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry for the Determination of Elemental Concentrations in Soil and Sediment: Rev 0. 2007. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/6200.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- López-Núñez, R.; Bello-López, M.A.; Santana-Sosa, M.; Bellido-Través, C.; Burgos-Doménech, P. Effect of Particle Size on Compost Analysis by Portable X-ray Fluorescence. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Geoanalysts. Reference Material Data Sheet SdAR-M2 Metal-Rich Sediment; International Association of Geoanalysts: Nottingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10694: Soil quality — Determination of organic and total carbon after dry combustion (elementary analysis).

- CSN EN 13650; Soil Improvers and Growing Media—Extraction of Aqua Regia Soluble Elements. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- Tomlinson, D.L.; Wilson, J.G.; Harris, C.R.; et al. Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgolander Meeresunters 1980, 33, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ruíz, J.; Galán-Huertos, E.; Gómez-Ariza, J. Estudio de Elementos Traza en Suelos de Andalucía. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain.

- . European Union. Commission Decision (EU) 2022/1244 of 13 July 2022 establishing the EU Ecolabel criteria for growing media and soil improvers (notified under document C(2022) 4758) (Text with EEA relevance). Official Journal of the European Union L 190, 19.7.2022, pp. 141-165. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022D1244.

- Jenkins, E.M.; Galbraith, j.; Paltseva, A.A. Portable X-ray fluorescence as a tool for urban soil contamination analysis: accuracy, precision, and practicality. 2025. Soil 2025, 11, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M., Chen, J., Huang, B., and Zhao, Y.: Resampling with in situ field portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (FPXRF) to reduce the uncertainty in delineating the remediation area of soil heavy metals, Environ. Pollut., 2021, 271, 116310. [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.R.; Besançon, T.; Rabinovich, A. Equine Manure Composition, Soil Fertility and Forage Response. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2025, 56(9), 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Serrano, P.; Lucena-Marotta, J.J.; Ruano-Criado, S.; Nogales-García, M. fosfatada. In Guía práctica de la fertilización racional de los cultivos en España (Practical guide to the rational fertilization of crops in Spain); Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino: Madrid. Spain, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Mompó, C.; Pomares García, F. Abonado de los cultivos hortícolas. In Guía práctica de la fertilización racional de los cultivos en España (Practical guide to the rational fertilization of crops in Spain); Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino: Madrid. Spain, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- García-Serrano, P.; Lucena-Marotta, J.J.; Ruano-Criado, S.; Nogales-García, M. fosfatada. In Guía práctica de la fertilización racional de los cultivos en España (Practical guide to the rational fertilization of crops in Spain); Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino: Madrid. Spain, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, F.; L Clemente, L.; Dı́az Barrientos, E.; López, R.; Murillo, J.M. Heavy metal pollution of soils affected by the Guadiamar toxic flood. Sci Total Environ. 1999, 242, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, R.; Hallat, J.; Castro, A.; Miras, A.; Burgos, P. Heavy metal pollution in soils and urban-grown organic vegetables in the province of Sevilla, Spain, Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2019, 35(4), 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Pendias, H. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 3rd ed.; CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, Fla, 2001.

- Delbecque, N.; Van Ranst, E.; Dondeyne, S.; Mouazen, A.M.; Vermeir, P.; Verdoodt, A. Geochemical fingerprinting and magnetic susceptibility to unravel the heterogeneous composition of urban soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 847, 157502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, L.B.; Westendorf, M.; Willians, C. Managing manure, erosion, and water quality in and around horse pastures. In Horse Pasture Management, 2nd ed.; Sharpe, P.H., Eds.; Academic Press: 2025. pp. 277-295.

- González-García, F. Estudio Agrobiologico de la provincia de Sevilla. Centro de Edafologia y Biologia Aplicada del Cuarto. CSIC, Sevilla, Spain, 1962.

- San-Emeterio, L.M.; De la Rosa, J.M.; Knicker, H.; López-Núñez, R.; González-Pérez, J.A. Evolution of Maize Compost in a Mediterranean Agricultural Soil: Implications for Carbon Sequestration. Agronomy 2023, 13, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Certified Value mg kg-1 |

Average value mg kg-1 |

Standard Deviation |

CV % |

Recovery % |

Minimum recovery % |

Maximum recovery % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | 15 | 19.1 | 2.3 | 12.0 | 127.2 | 105.9 | 148.2 |

| As | 76 | 79.7 | 9.3 | 11.7 | 104.9 | 86.1 | 117.1 |

| Ba | 990 | 871 | 13.7 | 1.6 | 88.0 | 86.1 | 90.2 |

| Cr | 49.6 | 61.1 | 12.2 | 19.9 | 123.2 | 84.6 | 149.6 |

| Cu | 236 | 219 | 13.3 | 6.1 | 92.9 | 86.3 | 99.7 |

| Mn | 1038 | 844 | 28.8 | 3.4 | 81.3 | 76.0 | 84.8 |

| Ni | 48.8 | 76.4 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 156.6 | 134.7 | 177.2 |

| Pb | 808 | 796 | 17.9 | 2.2 | 98.5 | 93.6 | 99.9 |

| Rb | 149 | 133 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 89.5 | 85.5 | 91.6 |

| S | 970 | 1068 | 98.9 | 9.3 | 110.1 | 94.0 | 121.1 |

| Sb | 107 | 103 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 95.9 | 91.8 | 100.1 |

| Sr | 144 | 142 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 98.5 | 95.1 | 101.4 |

| Th | 14.2 | 16.9 | 3.1 | 18.1 | 119.0 | 87.5 | 145.7 |

| Ti | 1798 | 1407 | 97.1 | 6.9 | 78.3 | 67.2 | 83.1 |

| Zn | 760 | 716 | 17.5 | 2.4 | 94.2 | 90.6 | 98.2 |

| K × 10-3 | 41.5 | 37.6 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 90.7 | 78.4 | 96.4 |

| 1Fe × 10-3 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 100.7 | 99.2 | 101.7 |

| 1Ca × 10-3 | 6.00 | 5.88 | 0.14 | 2.4 | 98.0 | 94.1 | 101.5 |

| 1Mg × 10-3 | 2.96 | 4.63 | 1.24 | 26.9 | 156.4 | 92.9 | 205.7 |

| 1Al × 10-3 | 66.0 | 37.5 | 2.43 | 6.5 | 56.8 | 53.5 | 63.3 |

| 1Si × 10-3 | 343 | 292 | 13.0 | 4.4 | 85.1 | 79.9 | 90.7 |

| 1P | 345 | 549 | 91 | 16.8 | 159.1 | 129.9 | 183.8 |

| Control soil mg kg-1 |

Average value mg kg-1 |

Standard Deviation mg kg-1 |

CV1 % |

Minimum mg kg-1 |

Maximum mg kg-1 |

N2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 396 | 1337 | 769 | 57.5 | 598 | 5146 | 46 |

| Zn | 22.0 | 66.2 | 31.1 | 47.0 | 36.0 | 244.3 | 46 |

| 3Ca × 10-3 | 14.3 | 62.7 | 23.6 | 37.6 | 20.1 | 123.4 | 46 |

| Pb | 22.3 | 20.8 | 6.9 | 33.4 | 10.8 | 51.8 | 46 |

| P | 1390 | 2485 | 689 | 27.7 | 1009 | 3961 | 46 |

| Sr | 20.7 | 60.0 | 16.3 | 27.2 | 29.0 | 90.2 | 46 |

| Cu | 19.7 | 33.2 | 8.4 | 25.4 | 18.6 | 51.0 | 44 |

| Zr | 164 | 140 | 34.1 | 24.3 | 76.9 | 233 | 46 |

| As | bd | 7.85 | 1.74 | 22.2 | 5.48 | 11.64 | 25 |

| Ba | 215 | 202 | 43.6 | 21.5 | 104 | 291 | 46 |

| 3Fe × 10-3 | 10.7 | 12.6 | 2.4 | 18.7 | 8.85 | 19.4 | 46 |

| Sb | 23.2 | 18.6 | 3.4 | 18.5 | 12.7 | 26.4 | 38 |

| V | 35.7 | 37.6 | 6.9 | 18.3 | 28.7 | 57.2 | 44 |

| Mn | 166 | 169 | 29.1 | 17.2 | 110 | 257 | 46 |

| 3Al × 10-3 | 19.1 | 15.3 | 2.55 | 16.6 | 10.9 | 21.3 | 46 |

| Ni | 29.7 | 32.8 | 4.9 | 15.0 | 25.6 | 44.2 | 27 |

| 3Mg × 10-3 | bd | 5.13 | 0.76 | 14.7 | 4.47 | 6.30 | 5 |

| Rb | 19.3 | 23.9 | 3.5 | 14.6 | 18.0 | 31.1 | 46 |

| 3K × 10-3 | 7.01 | 7.48 | 1.09 | 14.5 | 5.42 | 10.9 | 46 |

| Ti | 2020 | 1607 | 227 | 14.2 | 1198 | 2172 | 46 |

| 3Si × 10-3 | 245.5 | 208.7 | 24.6 | 11.8 | 157.0 | 274.4 | 46 |

| Control soil mg kg-1 |

Average value mg kg-1 |

Standard Deviation mg kg-1 |

CV1 % |

Minimum mg kg-1 |

Maximum mg kg-1 |

N2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector 1 and 2 | ||||||||

| pH | 7.36 | 7.41 | 0.40 | 5.50 | 6.33 | 8.21 | 41 | |

| EC3 | dS m-1 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 83.0 | 0.12 | 2.60 | 41 |

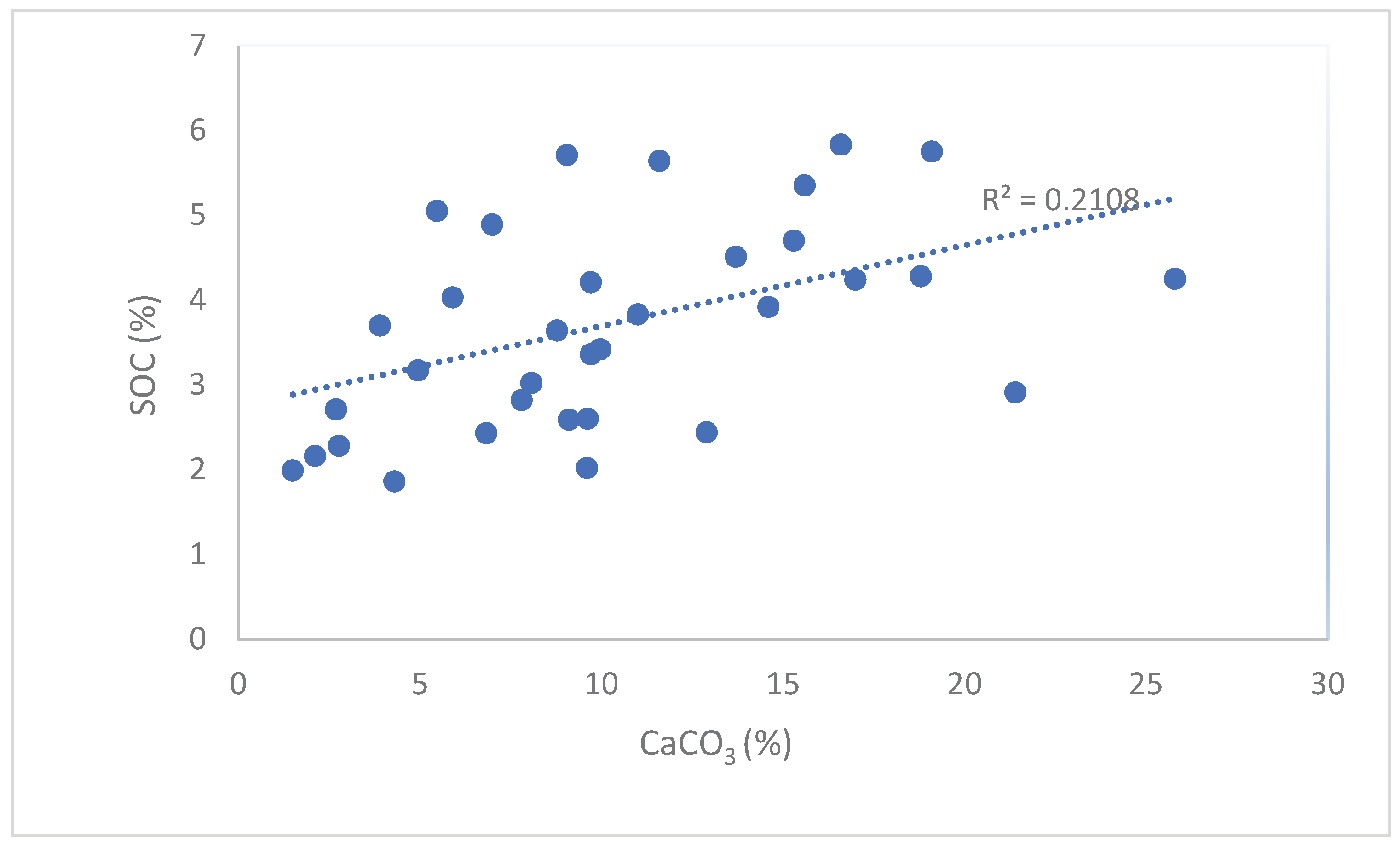

| CaCO3 | % | 1.93 | 9.86 | 5.48 | 55.6 | 1.50 | 25.80 | 41 |

| SOC4 | % | 1.23 | 3.57 | 1.18 | 33.2 | 1.86 | 5.83 | 41 |

| total-N | % | 0.073 | 0.355 | 0.116 | 32.7 | 0.203 | 0.605 | 41 |

| C/N | 16.6 | 10.1 | 1.2 | 12.2 | 8.3 | 13.2 | 41 | |

| avail-P5 | mg kg-1 | 26 | 264 | 108 | 41.0 | 97 | 523 | 46 |

| avail-K6 | mg kg-1 | 113 | 375 | 294 | 78.4 | 116 | 1755 | 41 |

| Sector 1 | ||||||||

| pH | 7.36 | 7.39 | 0.44 | 5.9 | 6.33 | 8.21 | 33 | |

| EC | dS m-1 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 67.7 | 0.12 | 1.67 | 33 |

| CaCO3 | % | 1.93 | *10.64 | 5.8 | 54.3 | 1.5 | 25.8 | 33 |

| SOC | % | 1.23 | *3.78* | 1.20 | 31.7 | 1.99 | 5.83 | 33 |

| total-N | % | 0.073 | *0.377* | 0.118 | 31.3 | 0.203 | 0.605 | 33 |

| C/N | 16.6 | *10.1 | 1.18 | 11.7 | 8.3 | 13.2 | 33 | |

| avail-P | mg kg-1 | 26 | *276 | 110 | 40.0 | 97 | 523 | 38 |

| avail-K | mg kg-1 | 113 | 412 | 315 | 76.4 | 142 | 1755 | 33 |

| Sector 2 | ||||||||

| pH | 7.36 | 7.49 | 0.23 | 3.1 | 7.22 | 7.84 | 8 | |

| EC | dS m-1 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.82 | 125 | 0.16 | 2.60 | 8 |

| CaCO3 | % | 1.93 | 6.64 | 2.09 | 31.5 | 3.9 | 9.5 | 8 |

| SOC | % | 1.23 | 2.72* | 0.66 | 24.3 | 1.86 | 3.70 | 8 |

| total-N | % | 0.073 | *0.264* | 0.045 | 17.1 | 0.208 | 0.344 | 8 |

| C/N | 16.6 | *10.2 | 1.52 | 14.9 | 8.6 | 12.4 | 8 | |

| avail-P | mg kg-1 | 26 | *208 | 83 | 39.8 | 113 | 370 | 8 |

| avail-K | mg kg-1 | 113 | 221 | 81 | 36.7 | 116 | 339 | 8 |

| Horse manure | Horse manure | Horse manure | Cow dung | Commercial compost | Biowaste compost |

||

| Moisture | % | 53.0 | 26.0 | 72.0 | 20.9 | 23.5 | 11.7 |

| pH | 8.85 | 7.88 | 8.14 | 7.58 | 9.05 | 8.51 | |

| E.C.1 | dS m-1 | 1.40 | 1.84 | 1.86 | 4.08 | 1.52 | 3.45 |

| Inorg-C | g kg-1 | 2.25 | 4.48 | 2.29 | 5.94 | 5.95 | 15.0 |

| Org-C | g kg-1 | 404 | 99.6 | 365 | 356 | 121 | 328 |

| OM2 | g kg-1 | 768 | 189 | 693 | 676 | 229 | 607 |

| N | g kg-1 | 13.9 | 9.34 | 14.0 | 22.5 | 12.9 | 32.6 |

| C/N ratio | 29.1 | 10.7 | 26.0 | 15.8 | 9.0 | 10.1 | |

| Ca | g kg-1 | 19.1 | 24.3 | 12.6 | 23.8 | 19.4 | 83.2 |

| K | g kg-1 | 12.0 | 5.68 | 19.4 | 15.1 | 11.3 | 11.4 |

| Mg | g kg-1 | 2.83 | 2.33 | 3.66 | 4.42 | 6.69 | 7.79 |

| Na | g kg-1 | 7.62 | 1.70 | 4.26 | 6.58 | 3.14 | 6.43 |

| S | g kg-1 | 2.66 | 1.55 | 2.53 | 3.90 | 2.55 | 5.52 |

| P | g kg-1 | 3.95 | 2.74 | 3.78 | 4.70 | 5.20 | 6.99 |

| Al | g kg-1 | 1.55 | 7.19 | 2.96 | 2.22 | 8.57 | 5.07 |

| As | mg kg-1 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | 21.9 | 1.02 |

| B | mg kg-1 | 11.9 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 13.8 | 20.7 | 34.4 |

| Ba | mg kg-1 | 39.8 | 53.0 | 69.0 | 34.4 | 67.0 | 49.9 |

| Cd | mg kg-1 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.19 |

| Co | mg kg-1 | 0.55 | 2.39 | 0.87 | 1.44 | 3.80 | 1.31 |

| Cr | mg kg-1 | 10.1 | 38.2 | 10.9 | 12.9 | 92.8 | 40.2 |

| Cu | mg kg-1 | 10.8 | 23.6 | 8.1 | 22.1 | 46.6 | 56.7 |

| Fe | mg kg-1 | 1697 | 8286 | 2687 | 2546 | 9297 | 7097 |

| Li | mg kg-1 | 2.01 | 7.70 | 4.09 | 3.31 | 28.3 | 4.57 |

| Mn | mg kg-1 | 95.0 | 123 | 90.0 | 159 | 343 | 207 |

| Mo | mg kg-1 | 1.43 | 0.79 | 2.38 | 1.87 | 2.80 | 3.44 |

| Ni | mg kg-1 | 5.70 | 8.66 | 5.39 | 7.30 | 44.7 | 26.1 |

| Pb | mg kg-1 | 8.0 | 9.5 | 14.5 | 1.9 | 14.9 | 24.1 |

| Sn | mg kg-1 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 0.48 | 1.9 | 13.8 |

| Sr | mg kg-1 | 48.0 | 58.6 | 101.4 | 56.6 | 84.8 | 193 |

| V | mg kg-1 | 4.2 | 14.6 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 16.3 | 10.9 |

| Zn | mg kg-1 | 41.1 | 68.5 | 49.6 | 155.1 | 153.5 | 167 |

| Predictor | t | Sig. | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available-K Accuracy 73.7% | |||

| K | 2.391 | 0.000 | 0.656 |

| Al | -4.275 | 0.000 | 0.133 |

| Mn | -3.097 | 0.004 | 0.070 |

| Zn | -2.896 | 0.007 | 0.061 |

| pH | -2.857 | 0.007 | 0.059 |

| Available-P Accuracy 83.6% | |||

| Sr | 7.403 | 0.000 | 0.436 |

| P | 6.218 | 0.000 | 0.307 |

| Al | 4.001 | 0.000 | 0.127 |

| Rb | -2.554 | 0.015 | 0.052 |

| Mn | -2.397 | 0.021 | 0.046 |

| Plot | 35 | 34 | 45 | Zone 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | 56.3 (6) | 16.5 (3) | 57.3 (4) | 67.7 (33) |

| CaCO3 | 21.0 (6) | 32.3 (3) | 15.0 (4) | 54.3 (33) |

| SOC | 14.2 (6) | 16.0 (3) | 32.6 (4) | 31.7 (33) |

| Total-N | 12.8 (6) | 9.1 (3) | 27.3 (4) | 31.3 (33) |

| avail-P | 7.7 (6) | 8.9 (4) | 14.3 (4) | 40.0 (38) |

| avail-K | 55.1 (6) | 34.5 (3) | 40.6 (4) | 76.4 (33) |

| S | 11.3 (6) | 6.9 (4) | 6.4 (4) | 40.8 (38) |

| Zn | 12.1 (6) | 6.4 (4) | 5.5 (4) | 47.8 (38) |

| Ca | 10.3 (6) | 5.8 (4) | 7.3 (4) | 37.1 (38) |

| Pb | 9.1 (6) | 18 (4) | 18.0 (4) | 17.2 (38) |

| Cu | 26.1 (6) | 7.6 (4) | 2.1 (4) | 26.0 (37) |

| Ni | 24.0 (4) | 7.8 (3) | -- | 15.9 (23) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).