Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Results and Discussion

Preparation of Samples

3. Characterisation of Samples

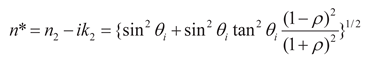

3.1. Optical Microscopy Images

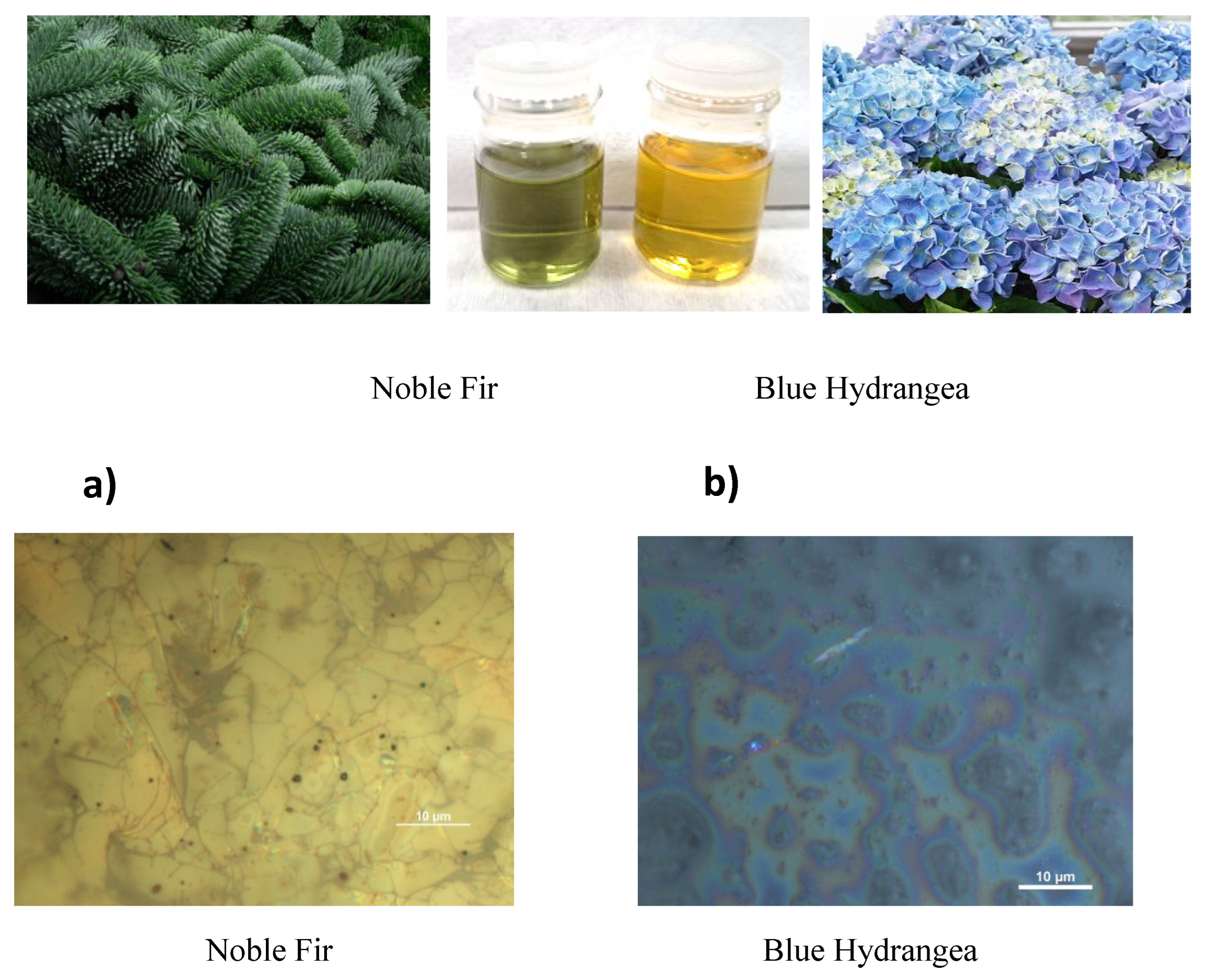

3.2. Photoluminescence Spectroscopy

3.3. Reflection/Absorption Spectroscopy

3.4. Ellipsometric Measurements

3.5. Fourier Transforms Infrared Spectroscopy

3.6. Photoluminescence Spectra

3.7. Absorption Spectra

3.8. FTIR Spectroscopy

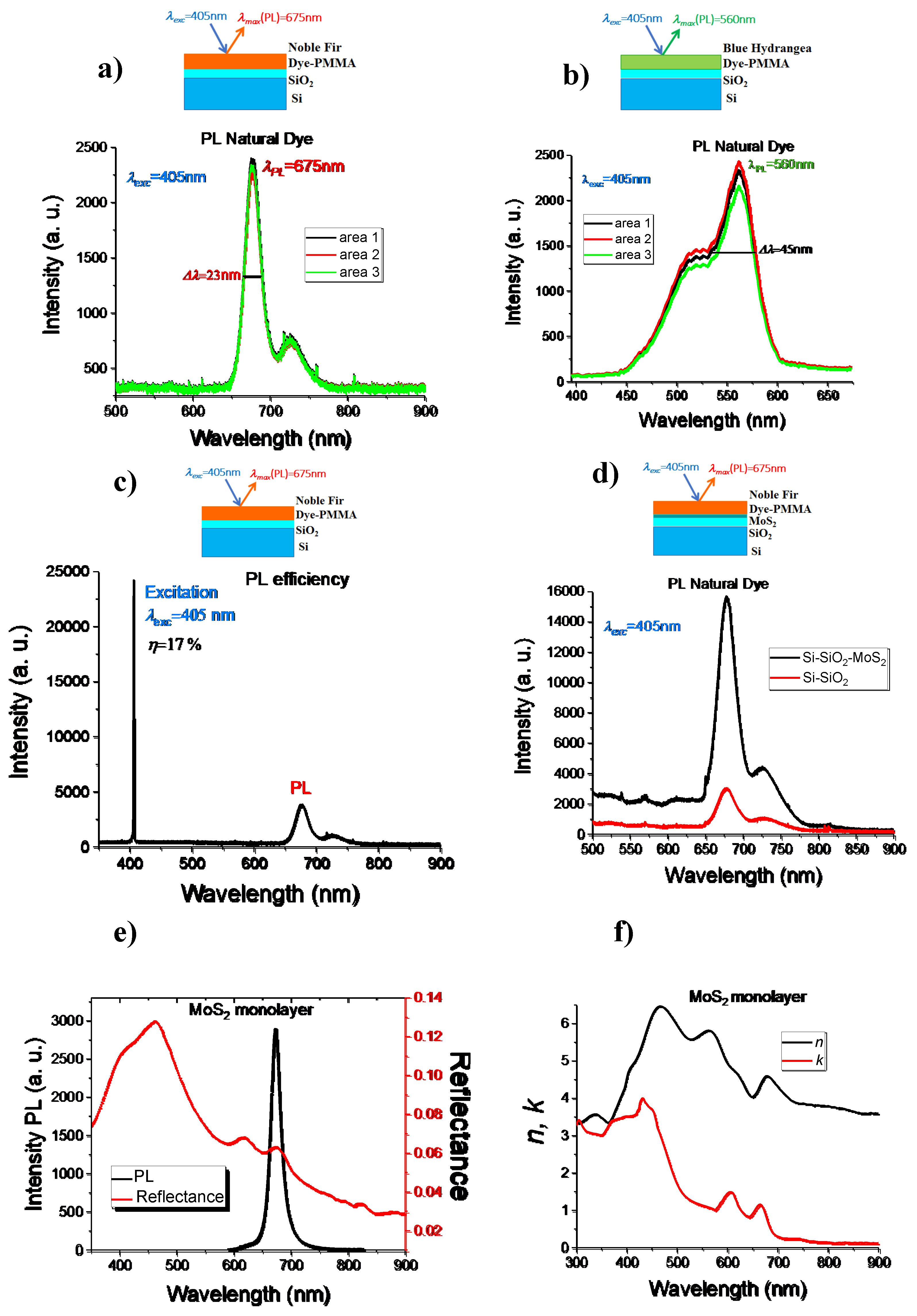

3.9. PL Performance Based on Natural Dyes Excited by Blue GaN Photodiode

3.10. A Circular Economy Strategy for Photoluminescent Organic LEDs Based on Natural Dyes

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, J.; Lv, Z.; Luo, J.; Shi, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wang, X. Organic Cocrystal Alloys: From Three Primary Colors to Continuously Tunable Emission and Applications on Optical Waveguides and Displays. Small 2024, 20, e2400313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, S.; Xie, Z.; Huang, K.; Yan, K.; Zhao, Y.; Redshaw, C.; Feng, X.; Tang, B.Z. Molecular Engineering toward Broad Color-Tunable Emission of Pyrene-Based Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogens. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2400301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoročenkova, J.; Filgas, J.; Khan, N.M.; Slavíček, P.; Klán, P. Thermal Truncation of Heptamethine Cyanine Dyes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 19768–19781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lee, H.; Jeong, E.G.; Choi, K.C.; Yoo, S. Organic Light-Emitting Diodes: Pushing Toward the Limits and Beyond. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1907539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richhariya, G.; Kumar, A.; Tekasakul, P.; Gupta, B. Natural dyes for dye sensitized solar cell: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H.; Ray, S.K.; Chakrabarty, P.; Pal, S.; Gangopadhyay, G.; Das, S.; Das, S.; Basori, R. High-Performance Chlorophyll-b/Si Nanowire Heterostructure for Self-Biasing Bioinorganic Hybrid Photodetectors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 5726–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, M.S.; Raj, V.; Devi, H.V.S.; Sankararaman, S. Optical emission diagnosis of carbon nanoparticle-incorporated chlorophyll for sensing applications. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2019, 18, 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-P.; Lin, R.Y.-Y.; Lin, L.-Y.; Li, C.-T.; Chu, T.-C.; Sun, S.-S.; Lin, J.T.; Ho, K.-C. Recent progress in organic sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 23810–23825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, H.; Dau, H. Preparation protocols for high-activity Photosystem II membrane particles of green algae and higher plants, pH dependence of oxygen evolution and comparison of the S2-state multiline signal by X-band EPR spectroscopy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2000, 55, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravets, V.G. Photoluminescence and Raman spectra of SnOx nanostructures doped with Sm ions. Opt. Spectrosc. 2007, 103, 766–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravets, V.G. Using electron trapping materials for optical memory. Opt. Mater. 2001, 16, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, C.; Lüttjohann, S.; Kravets, V.G.; Nienhaus, H.; Lorke, A.; Ifeacho, P.; Wiggers, H.; Schulz, C.; Kennedy, M.K.; Kruis, F.E. Vibrational and defect states in SnOx nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 99, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, P. New Contributions to the Optics of Intensely Light-Scattering Materials Part II: Nonhomogeneous Layers*. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1954, 44, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, R.M.A.; Bashara, N.M. Ellipsometry and polarized light, North-Holland, Amsterdam, 1987.

- Kravets, V.G.; Grigorenko, A.N. Water and seawater splitting with MgB2 plasmonic metal-based photocatalyst. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravets, V.G.; Wu, F.; Yu, T.; Grigorenko, A.N. Metal-Dielectric-Graphene Hybrid Heterostructures with Enhanced Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensitivity Based on Amplitude and Phase Measurements. Plasmonics 2022, 17, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Wolf, E.; Bhatia, A.B.; Clemmow, P.C.; Gabor, D.; Stokes, A.R.; Taylor, A.M.; Wayman, P.A.; Wilcock, W.L. Principles of Optics; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kravets, V.G.; Zhukov, A.A.; Holwill, M.; Novoselov, K.S.; Grigorenko, A.N. “Dead” Exciton Layer and Exciton Anisotropy of Bulk MoS2 Extracted from Optical Measurements. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 18637–18647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravets, V. Ellipsometry and optical spectroscopy of low-dimensional family TMDs. Semicond. Physics, Quantum Electron. Optoelectron. 2017, 20, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, A.M. Standards for photoluminescence quantum yield measurements in solution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2011, 83, 2213–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photobiology; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, United States, 2015.

- Larkum, A.W.; Kühl, M. Chlorophyll d: the puzzle resolved. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Jalali, T.; Maftoon-Azad, L.; Osfouri, S. Performance Evaluation of Natural Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: A Comparison of Density Functional Theory and Experimental Data on Chlorophyll, Anthocyanin, and Cocktail Dyes as Sensitizers. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 1693–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennel, F.; Lochbrunner, S. Long distance energy transfer in a polymer matrix doped with a perylene dye. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 3527–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuyan, C.A.; Madapu, K.K.; Prabakar, K.; Das, A.; Polaki, S.R.; Sinha, S.K.; Dhara, S. A Novel Methodology of Using Nonsolvent in Achieving Ultraclean Transferred Monolayer MoS2. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, M. The International Standards as the Constitution of Life Cycle Assessment: The ISO 14040 Series and its Offspring, in: W. Klöpffer (Ed.), Background and Future Prospects in Life Cycle Assessment, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2014: pp. 85–106. [CrossRef]

- Tsoka, S.; Tsikaloudaki, K. Design for Circularity, Design for Adaptability, Design for Disassembly, in: Bragança, L.; Griffiths, P.; Askar, R.; Salles, A.; Ungureanu, V.; Tsikaloudaki, K.; Bajare, D.; Zsembinszki, G.; Cvetkovska, M. (Eds.), Circular Economy Design and Management in the Built Environment, Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2025: pp. 257–272. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).