1. Introduction

Dengue is a global public health problem with common epidemics in the tropical countries. Dengue incidences are greatly underestimated because most dengue infections are self-limiting, inapparent cases that usually go unreported [

1,

2,

3]. Dengue is a viral infection transmitted to humans by the bite of infected mosquitoes that occurs in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, primarily in urban and semi-urban areas [

4]. The main vectors of the disease are mosquitoes of the species Aedes aegypti and, to a lesser extent, of the species Aedes albopictus. Over the past two decades, the incidence of dengue fever has increased dramatically worldwide, representing a significant public health challenge. Between 2000 and 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a tenfold increase in the number of dengue cases reported worldwide, from 500,000 to 5.2 million [

5]. Dengue cases have increased sharply in all six WHO regions, and the number of cases has nearly doubled each year since 2021, with more than 12.3 million cases reported by the end of August this year, almost double the 6.5 million cases reported in all of 2023 [

6]. This might be explained by the influence of climatic and ecological deterioration, increasing crisis circumstances, and congested resettlement camps for both refugees and internally displaced persons (IDP) on disease outbreak [

7]. Recently, the WHO announced the Global Strategic Plan for Preparedness, Response, and Readiness (SPRP) for Dengue and Other Arboviral Diseases Spread by Aedes Mosquitos [

6].

A meta-analysis results showed that the overall prevalence of dengue virus in Africa is 14% [

8]. All four dengue serotypes (DENV-1–4) have been reported in the continent, with DENV-1 and DENV-2 being reported most frequently [

8,

9,

10]. Despite increasing reports of dengue in Africa, its burden in different epidemiological contexts is not well described [

8]. In Africa, as compared with 2019, dengue infections surged 9-fold by December 2023, with >270 000 cases and 753 deaths across 18 African countries [

11]. The inaugural dengue outbreak identified in Chad occurred in August 2023, following the displacement of refugees from Sudan to the neighboring region of Ouaddaï. When such complex epidemiologic and mobility settings are combined with appropriate environmental conditions for Aedes spp vectors, outbreaks are sure to occur more frequently [

11]. This inaugural dengue epidemic in Chad marks a significant milestone for the nation, underscoring the difficulties in preparedness and response to vector-borne diseases. The surge of Chad's inaugural dengue outbreak could be explained by insufficient surveillance, weak healthcare systems, poor sanitation and dense populations, limited resources for vector control, and lack of public awareness. Given the climatic conditions conducive to mosquito dissemination, the ongoing humanitarian situation caused by the significant influx of refugees and returnees from Sudan, and limited response resources, WHO evaluates the risk posed by this outbreak at the national level as high [

4].

Despite the publication of numerous reports concerning this outbreak, no study has been undertaken to delineate the epidemiological profile and characterization of the initial dengue epidemic in Chad. Outbreak investigations provide a foundation for the formulation of public health policies and preventive guidelines. Scientific knowledge enables the formulation of broad conclusions, the identification of emerging trends, and the demonstration of novel preventive strategies [

12].

2. Methods

2.1. Study Objectives

In response to the need for a deeper understanding of the first dengue outbreak in Chad, this study aims to (1) Describe confirmed dengue cases in terms of incidence, clinical, demographic, and geographic characteristics; (2) Investigate socio-demographic and environmental factors associated with confirmed dengue cases findings; (3) Assess the national response capacity by evaluating, outbreak coordination, risk communication, and management efforts, including surveillance, diagnosis, community engagement, and logistics; (4) Identify the key challenges encountered during the outbreak response.

2.2. Study design

This was a cross-sectional descriptive and analytical study using retrospective data from an outbreak investigation, with suspected, probable, and confirmed dengue cases in Chad from August 03, 2023 to January 7, 2024.

2.3. Study Area

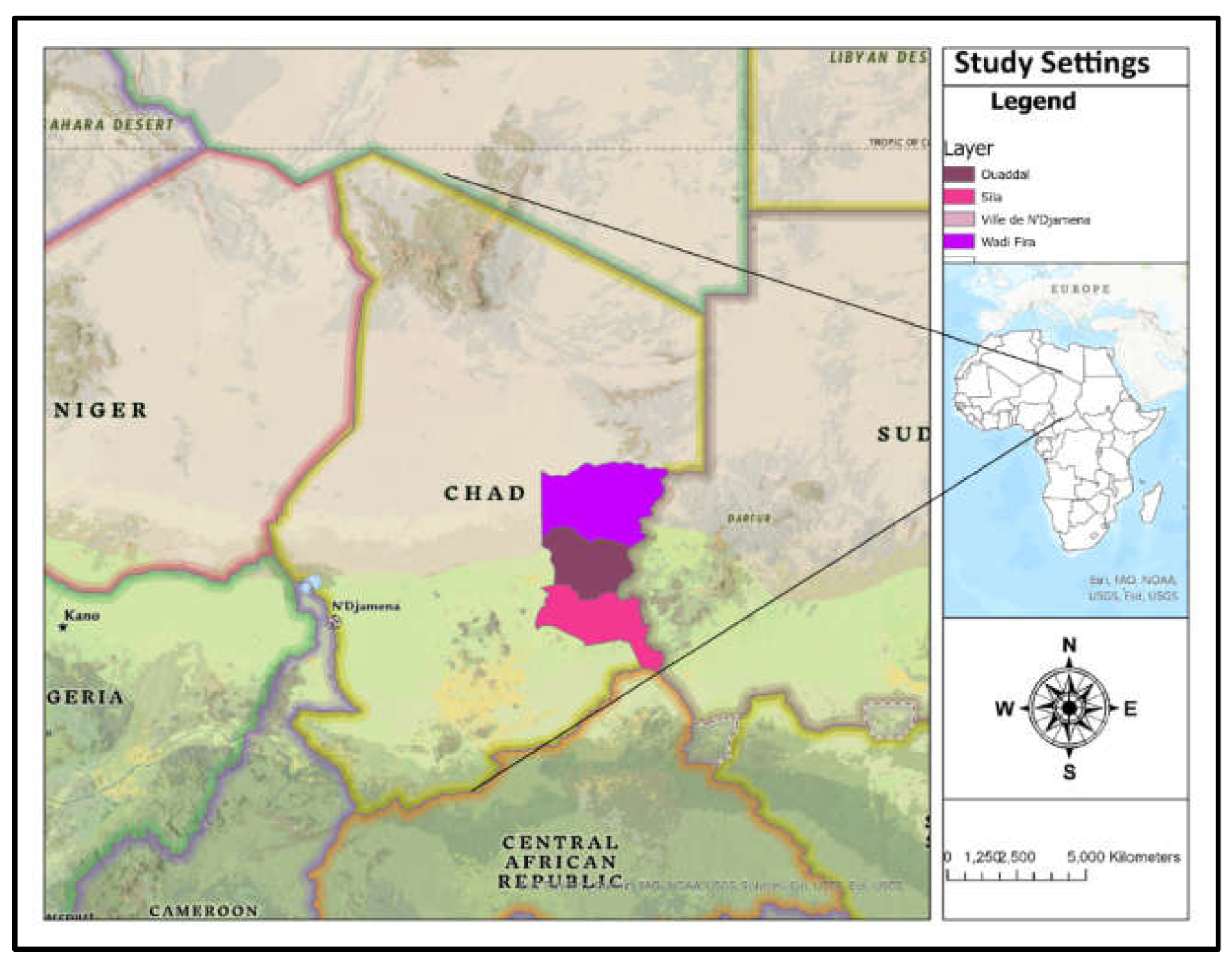

Chad is a landlocked, Sahelian country in Central Africa that faces security issues from neighbouring wars and the effects of climate change (

Figure 1) [

13]. Districts of provinces that have recorded cases of dengue (Abéché, Adré and Abougoudam in Ouaddaï, Biltine, Arada, Amzoer and Guereda in Wadi Fira, Abdi and Goz-Beida in Sila, Ndjamena East, Ndjamena South, and Ndjamena Center in the province of N’Djamena). As illustrated in

Figure 1, the majority of the damaged areas were in Eastern Chad. The environment of Eastern Chad is characterized by both tropical savanna climate and desertification. The tropical environment of Eastern Chad, especially in the Ouaddaï area, promotes mosquito breeding, such as dengue vectors. Furthermore, eastern Chad is at risk of dengue fever epidemics owing to a tropical environment, continuous Sudanese humanitarian crises, poor healthcare infrastructure, and cross-border mobility with Sudan which is an area with high risk of dengue [

14].

2.4. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included participants with the clinical and laboratory definition of a probable or confirmed dengue case. Participants with other infectious diseases that could mimic or confound a dengue diagnosis, including malaria, bacterial infections, or other arbovirus were excluded. Because of the expensive expense of RT-PCR in a large number of suspected cases, only those with positive RDT were eligible for RT-PCR. Then, we assumed that suspected patients with negative RDT were likewise negative for the Dengue RT-PCR.

2.5. The Outbreak Investigation

2.5.1. Case definition

According to the WHO, dengue case definition includes suspected, probable, confirmed and severe dengue [

15].

Suspected case (with or without warning signs):

• Fever and two or more of the following: (Persistent vomiting/nausea: three or more episodes in one hour or four episodes in six hours, progressive to continuous or severe abdominal pain, rash, aches and pains, tourniquet test positive, leukopenia) and any warning sign (sensory disturbances: irritability, drowsiness, and lethargy), mucous membrane bleeding: bleeding from the gums (gingivorrhagia), nose (epistaxis), or vagina unrelated to menstruation, or heavier than usual menstruation, or blood in the urine (hematuria), postural hypotension, fluid accumulation (clinically or detected by imaging, or both), enlarged liver (hepatomegaly), exceeding 2 cm below the costal margin, sudden onset, and progressive increase in hematocrit: on at least two consecutive measurements during patient monitoring [

15].

Probable case:

A patient is considered a probable case if suspected case with laboratory results indicative of a probable infection, such as positive detection of IgM antibodies or a compatible result from a rapid diagnostic test [

15].

Confirmed case:

• A probable case with laboratory confirmation:

1. Highly suggestive: Immunoglobulin M (IgM) positive in a single serum sample; Immunoglobulin G (IgG) positive + in a single serum sample with a house index (HI) titre of 1280 or greater; detection of viral antigen NS1+ in a single serum sample by ELISA or rapid tests [

15].

2. Confirmed with PCR positive; virus culture positive; IgM seroconversion in paired sera; and IgG seroconversion in paired sera or fourfold IgG titre increased in paired sera [

15].

Severe dengue:

Suspected dengue with one or more of the following: severe plasma leakage, leading to dengue shock syndrome, fluid accumulation with respiratory distress; severe bleeding, as evaluated by clinician; severe organ involvement, such as liver (aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation > 1000), central nervous system (impaired consciousness) or heart and other organs [

15].

2.5.2. Case finding

The Ministry of Health and Prevention in Chad coordinated case finding with the Departments of Public Health and the WHO. Three provinces (Ouaddaï, Wadi Fira, and N'Djamena) and three health districts (Biltine, Abéché, and N'Djamena) were affected. The Public Health Emergency Operations Center (COUSP-PHEOC) was activated, and an Incident Management System (IMS) was implemented, including the appointment of an Incident Manager. Similarly, a national response plan to the dengue outbreak was developed with WHO help [

16]. A provincial plan was also drawn up specifically for Ouaddaï, Wadi Fira, and N'Djamena provinces, and the deployment of a joint team from the provincial delegation of health and prevention and the WHO for in-depth investigations were also put in place [

16]. Furthermore, dissemination of case definitions and key messages to the community and institutions were conducted as well [

16]. Cases were identified by clinicians in health facilities based on common symptoms and subsequently confirmed through laboratory testing. Clinicians in Chad were alerted to suspect dengue in patients presenting with acute fever (lasting 2-7 days) accompanied by typical other symptoms as described above. As cases were identified, each was interviewed using a standardized dengue questionnaire to collected other related data such as exposure of Dengue vectors and travel two weeks ago in high-risk.

2.5.3. Surveillance and investigation

The Ministry of Public Health and Prevention declared a dengue outbreak in the Republic of Chad on August 15, 2023. There were 2404 suspected cases, 63 of which were confirmed cases, reported throughout eight health districts in four provinces. Clinical diagnoses were made by medical personnel in local health facilities, most notably in the affected provinces, while laboratory confirmation was conducted by specialized institutions. Clinical care was provided by a combination of local healthcare professionals, the Chadian Ministry of Public Health, and international humanitarian and health organizations. This was followed by the activation of the PHEOC and the establishment of an IMS, which included the appointment of an Incident Manager. Briefings for focus points on Dengue surveillance were planned. Briefings on dengue surveillance concentrated on increasing early detection, reporting accuracy, and coordinating response operations in resource-constrained environments. Furthermore, the definition of dengue cases was disseminated to health facilities, along with a briefing on ongoing research involving the evaluation of patient registers and the collection of samples from cases fulfilling the description of suspected cases. The IMS team collects data from healthcare facilities and private clinics. Finally, the national action plan for the dengue epidemic, which included a rapid assessment of severe public health hazards was approved.

2.5.4. Sample collection and laboratory investigation

Blood samples were collected primarily through venipuncture by experienced laboratory technologists or healthcare professionals at health facilities. R T-PCR was used to analyse materials taken during the first 5 days of sickness, whereas serological testing was used after day 7. RT-PCR and serological tests were performed on specimens obtained between 5-7 days after the beginning of illness, as well as ones with equivocal findings. The outbreak statement was made after dengue infection was verified blood samples examined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at N'Djamena's National Laboratory for Biosafety and Epidemics (LaBiEp). The samples were then transferred to the Pasteur Institute of Cameroon for confirmation using PCR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Laboratory tests and reagent orders, including Dengue Duo NS1 - IgG/IgM fast diagnostic assays and RT-PCR, were conducted. The SD Biosensor brand Bioline Dengue Duo (DENGUE NS1 Ag + IgG/IgM) test kits were likely used for rapid detection. For confirmatory testing, specialized laboratories such as the Institut Pasteur in Cameroon would likely use a different range of tests, including RT-PCR and ELISA, from various manufacturers. Additionally, genotyping of four specific serotypes, namely DENV1, DENV2, DENV3, and DENV4, was conducted. Subsequent to the procurement of RT-PCR kits and rapid diagnostic tests by WHO, Regional Disease Surveillance Systems Enhancement (REDISSE) IV, and Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); sustaining diagnostic operations in the laboratory and facilities that conducted expedited dengue assessments. Oversight of screening operations using fast assays and RT-PCR.

2.5.5. Environmental investigation

We conducted briefings and deployment of teams consisting of laboratory technicians, epidemiologists, and entomologists. Key environmental study issues included exposure to the primary vector (Aedes aegypti mosquitos) and recent travel to high-risk areas. Environmental investigations also included a study of vector behaviour. Vector density was based mostly on immature mosquito indices, which quantify the prevalence of mosquito larvae and pupae in and near dwellings.

2.6. Data collection and management

Data were acquired from the Ministry of Health and prevention of Chad's situation reports (SITREP) between August 03, 2023 and January 7, 2024. Both passive and active surveillance were used in the process of data collection. Demographic data, weekly cases, and response measures were gathered to determine the magnitude and effect of the outbreak. Data were obtained using an Excel spreadsheet line list in accordance with an established dengue epidemic data gathering protocol. Stata 18 MP (StataCorp., USA) was utilized for data administration and cleaning. The following information was gathered: case ID, age, gender, province, district, health center, travel to risk areas, dengue symptoms (fever, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, retro-orbital pain, cutaneous eruptions, bleeding, and other symptoms), onset dates, notification dates, laboratory specimen collection and analysis dates, results, and sources of information. To make sure the information submitted was accurate and of high quality, the quality control of data entry was conducted by a supervisor. Data were managed in accordance with HPA policy, which included safeguards to protect personally identifying information.

2.7. Statistical analysis and narrative synthesis

Data analysis was performed using Stata 18 MP (StataCorp., USA) and Excel. The first descriptive analysis was conducted to characterize the dengue outbreak in terms of demographic and epidemiological factors. Weekly case trends were plotted to show how the outbreak progressed. The demographic distribution of confirmed cases was grouped by age and gender. A description of the outbreak in terms of symptoms seen in suspected and confirmed cases was done using tables of frequencies and proportions (%). Descriptive analysis also revealed the province-specific distribution of confirmed dengue cases and deaths (new and cumulative). Finally, an epidemic curve trend was drawn to display the weekly trends of suspected, confirmed, deceased, and probable dengue cases.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to investigate potential factors associated with finding confirmed dengue cases. The odds ratios (ORs) and their 95%CIs were used to measure the strengths of association. Prior to logistic regression, a variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to check for multicollinearity among the predictor variables. If 0<VIF<5, there is no evidence of multicollinearity. To determine which factors were independently associated with being a dengue case, those with a P value <0.2 in univariable analysis were entered into a multivariable analysis. For both univariable and multivariable, p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. The GraphPad Prism version 9.2.0 was used to assess how case definition combined with dengue rapid test (RDT) and Dengue RT-PCR performed. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were computed to check how the tests performed. Finally, the results included a narrative synthesis that reviewed the primary themes of the measures implemented.

2.8. Ethical considerations

This study obtained the ethical approval from the Chadian Ministry of Health (reference: MSPP/SE/SG/COUSP/2023). Due to the nature of this investigation, the Ethics Committee authorised a waiver of consent to be acquired from the participants. The confidentiality of participants' information was maintained by giving a code number to each individual and securing the data in a locked cabinet and password-protected computer.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological profile of confirmed dengue cases

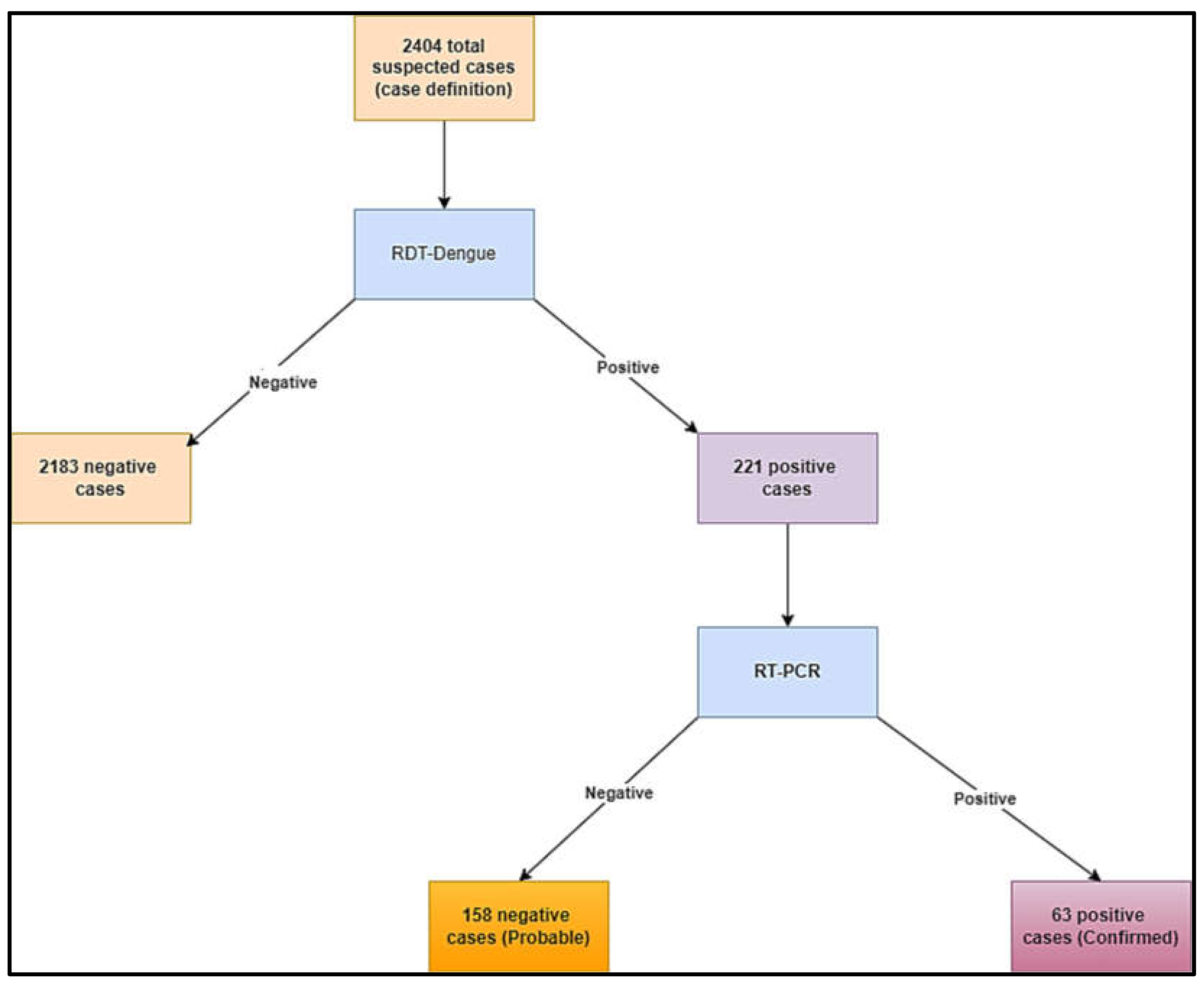

A total of 2404 suspected cases were recorded from 03 August 2023 to 07 January 2024 (

Figure 2). Among them, 63 were confirmed cases (2.62%) and 158 were probable cases (6.57%) (

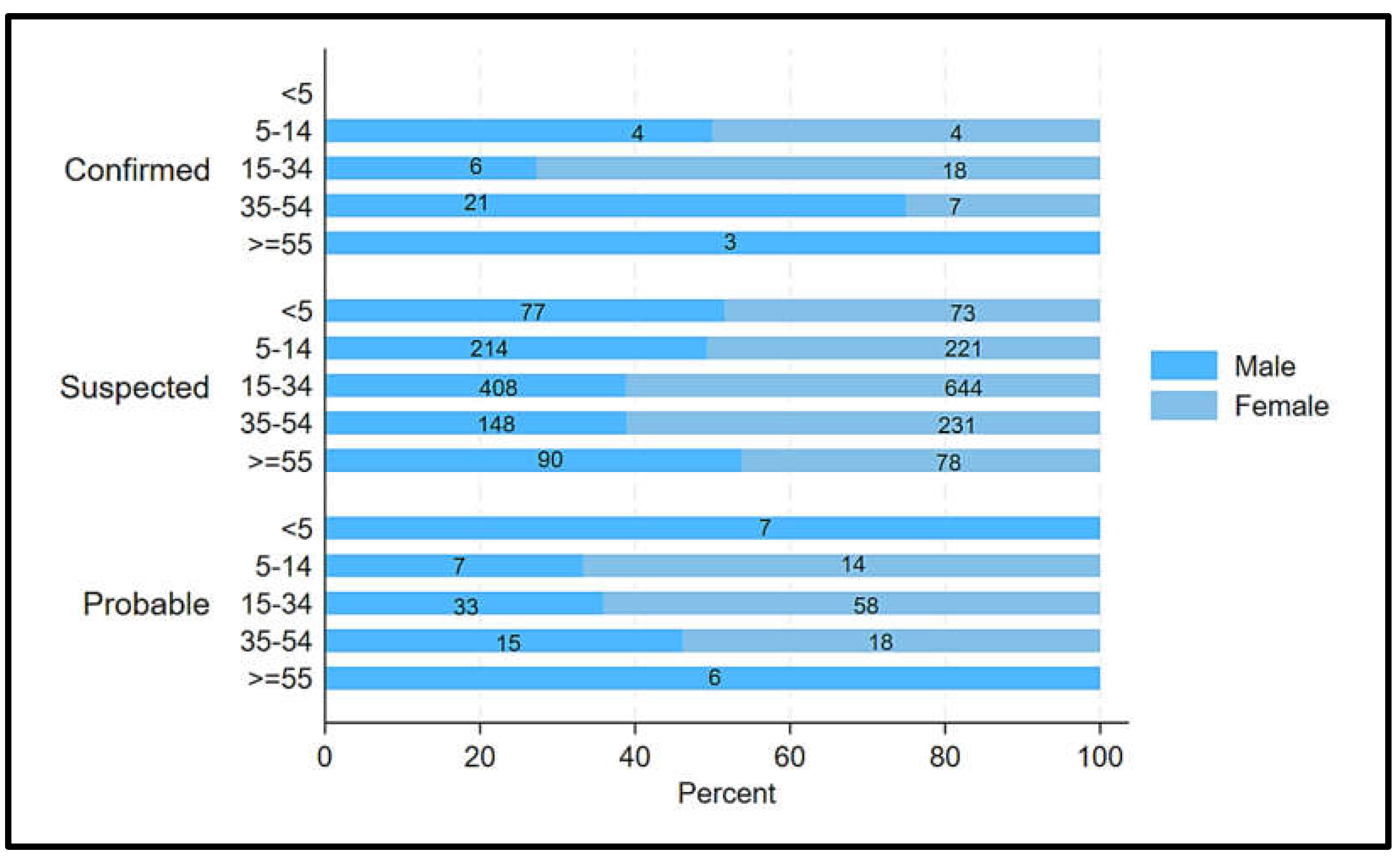

Figure 2). Among confirmed cases, 54.0% (34/63) were males and 46.03% (29/63) were females (

Figure 3). 52.38% (33/63) of confirmed cases were aged 15-44 years (

Figure 3). Furthermore, all three confirmed male cases were beyond 54 years (

Figure 3).

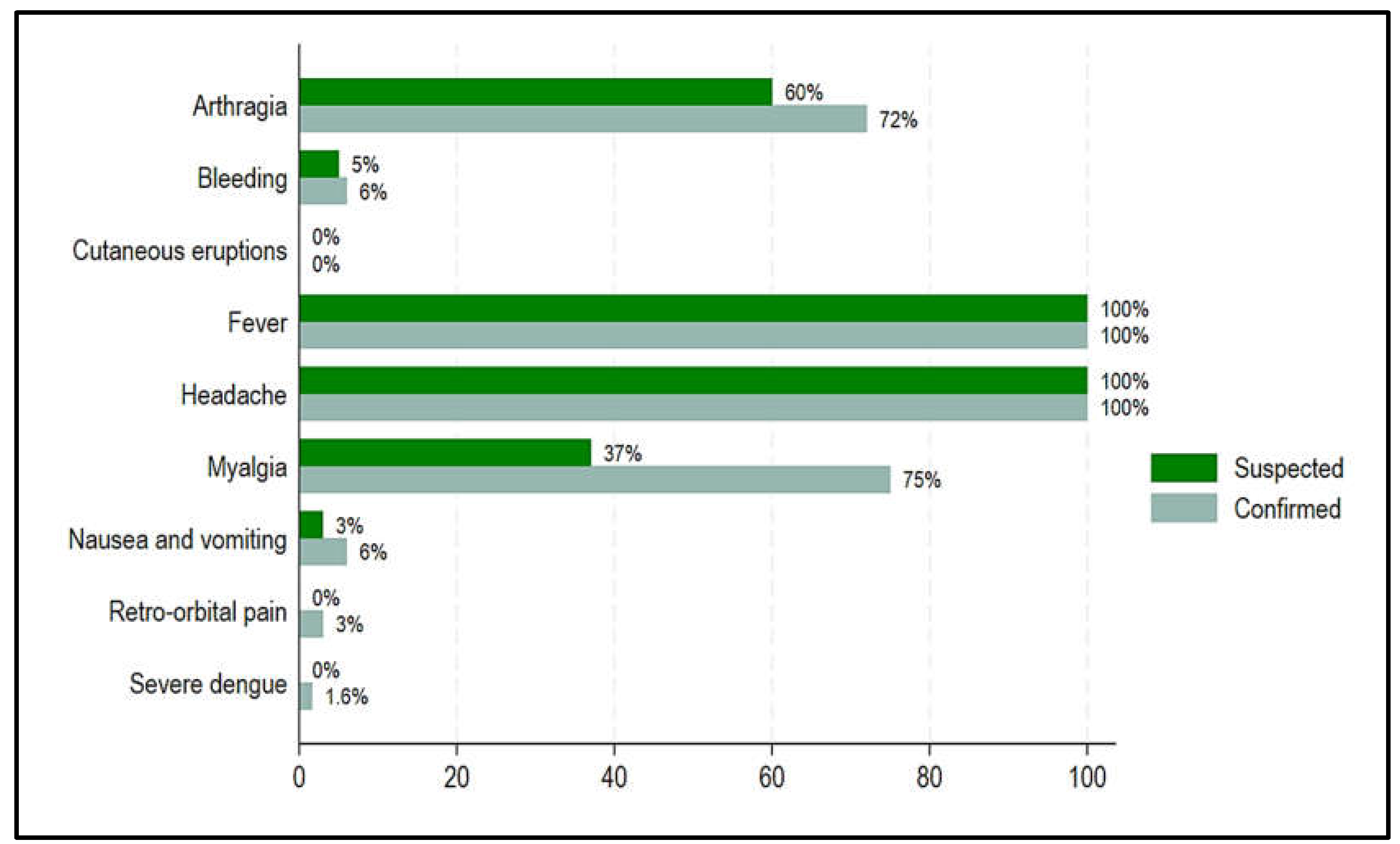

Figure 5 presents the most common clinical manifestations reported by the cases. Even though headache and fever had the same rates in both confirmed and suspected cases (100%), confirmed vs. suspected cases had higher rates of arthralgia (72.00% vs. 60.00%), myalgia (75.00% vs. 37.00%), nausea and vomiting (6.0% vs. 3.00%), retro-orbital pain (3.00% vs. 0.00%), severe dengue/shock (1.60% vs. 0.00%), bleeding (6.00% vs. 5.00%) (

Figure 5). However, none of the confirmed and suspected cases were found with cutaneous eruptions (

Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Study Flow diagram describing suspected, probable, and confirmed Dengue cases in Chad.

Figure 2.

Study Flow diagram describing suspected, probable, and confirmed Dengue cases in Chad.

Figure 3.

Distribution of confirmed, suspected, and probable cases of Dengue by gender and age, Chad, 2023-2024.

Figure 3.

Distribution of confirmed, suspected, and probable cases of Dengue by gender and age, Chad, 2023-2024.

Figure 4.

Common clinical manifestations comparing confirmed and suspected dengue cases, Chad, 2023-2024.

Figure 4.

Common clinical manifestations comparing confirmed and suspected dengue cases, Chad, 2023-2024.

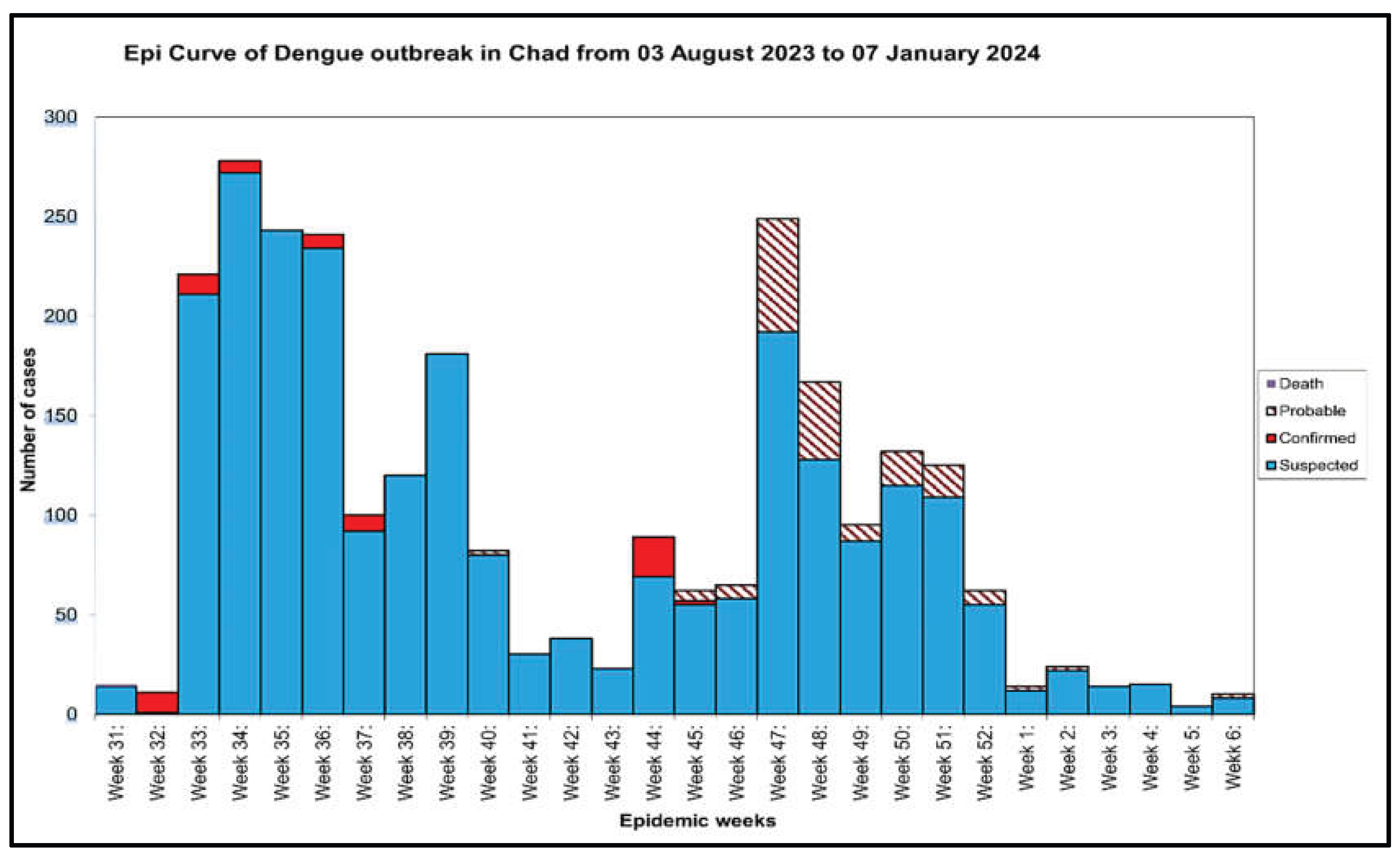

3.2. Outbreak magnitudes

The first suspected cases appeared in week 31 in 2023 and the last one was reported in week 6 in 2024, with the peak of the outbreak in week 4 (

Figure 5). The epidemiological trend showed that Chad recorded a cumulative total of 2,404 suspected dengue cases, including 63 confirmed cases and 1 death (

Figure 5). In the same line, the outbreak reached a peak of confirmed cases in week 14 (

Figure 5). Our results also revealed a total case fatality rate of 1.59 % (

Table 1).

Table 2 displays the results of the univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis. In univariable logistic regression, patients with fever, arthralgia, headache, and myalgia had a higher chance of having confirmed dengue cases, with a COR (95%CI) of 3.71(1.56 - 8.84, P-value = 0.003). Similarly, patients who stayed in areas where vectors were present were more likely to be confirmed dengue cases, with a COR (95%CI) of 5.40(2.09 - 13.93, P-value > 0.001). In contrast, patients who did not know if they had travelled to a high-risk zone two weeks ago and those whose case findings came from the health centres were less likely to be confirmed cases (COR 0.24 (95%CI 0.08 - 0.70, P-value = 0.009) and 0.17 (95%CI 0.04 - 0.71, P-value = 0.015). In multivariable logistic regression, only patients whose case results came from the health centres had a decreased chance of being confirmed (AOR: 0.04 (95%CI: 0.00 - 0.77, P-value = 0.033).

Figure 5.

Weekly progression of suspected, confirmed, deceased, and probable Dengue cases Chad, 2023-2024.

Figure 5.

Weekly progression of suspected, confirmed, deceased, and probable Dengue cases Chad, 2023-2024.

3.3. Diagnostic and accuracy of case definition combined to RDT and PCR

To compare how the case definition performed compared to dengue rapid diagnostic tests (RDT), we built two-by-two tables for diagnostic accuracy (

Table 3). For the comparison between the case definition and the RDT, the computed sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were estimated at 100% (95%CI: 94.2%-100%), 93.2% (95%CI: 92.2%-94.2%), 28.5% (23.0%-34.8%), and 100% (99.2%-100%), respectively. The whole-genome sequencing revealed that the circulating serotype for all 63 confirmed cases was DENV-1, genotype III.

3.4. National response assessments

The national response to Chad's first dengue outbreak was centered on seven axes: coordination, epidemiological surveillance, biological diagnostics, dengue case management, effective communication, vector control, and logistics.

Coordination entailed conducting weekly meetings at the central level, supervising outbreak response activities at all levels, and holding meetings in each province with administrative, traditional, and ABC authorities. This effort also includes the preparation and dissemination of situation reports, the development, compilation, and dissemination of dengue information bulletins, and the design of dengue data collection tools. Plan a validation workshop for data collection tools and administer a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) survey. Finally, train provincial trainers on SOPs and data collection methodologies; undertake an after-action review of the dengue outbreak; and conduct quarterly risk assessment Entomological actions were effective in reducing mosquito vector populations (significant reductions in key Aedes larval indices were observed) and contribute to halting dengue outbreaks as an integrated approach with strong community involvement was used.

3.5. Outbreak challenges uncounted

The first dengue outbreak in Chad presented numerous obstacles in terms of surveillance, emergency preparedness, and response, as well as financial concerns. Among these challenges that should be taken into account during the inter-epidemic period were insufficient financial resources to carry out the priority activities identified in the response plan, insufficient communication materials, insufficient medicines for case management in health facilities, insufficient logistical resources to initiate spraying in urban areas, insufficient laboratory reagents and consumables, and insufficient communication materials.

4. Discussion

This study aims to analyze the epidemiological data of the dengue outbreak in Chad, including parameters linked with confirmed dengue cases. Additionally, this study examined the epidemic response and control measures, as well as the many challenges encountered during the response. This was the first dengue outbreak in Chad, affecting twelve districts of four provinces, reportedly with the most confirmed in the province of Ouaddaï. It is substantial to highlight that province of Ouaddaï neighbouring the Sudan province of Darfur, where mosquito-borne viral diseases, including dengue, West Nile virus, and Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever infections are frequent [

1]. The ongoing conflict in Sudan has led to an upsurge in migration to Eastern Chad, particularly to Ouaddaï region, where roughly 50% of dengue-confirmed cases were diagnosed. This geographical location could be one of the most plausible hypotheses for the first dengue outbreak in Chad.

Our findings also contrasted with other studies that found the highest number dengue cases in those less than 14 years [

17,

18]. However, a study conducted in Thailand revealed an increase age of dengue cases ranging from 8.1 to 24.3 years [

19]. This contrast could be explained by different dengue virus serotypes circulating in the population [

20].

Our results showed that headache and fever were the most common symptoms, followed by arthralgia, myalgia, nausea and vomiting, retro-orbital pain, severe dengue/shock, and bleeding. Common clinical manifestations were quite similar to the picture of previous dengue outbreaks in Sudan, Somalia, Malaysia, and Bangladesh [

1,

17,

21,

22,

23]. Particular emphasis placed on one case of dengue shock syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), inducing a case fatality rate of 1,59%. Our study was also on the line with a study showing that, in rare instances, complex dengue infections may result in severe consequences, including fulminant hepatic failure, renal dysfunction, encephalitis, encephalopathy, neuromuscular and ocular abnormalities, convulsions, and cardiomyopathy [

24]. Healthcare providers must recognize the potential complications of dengue fever and swiftly diagnose and manage them to enhance patient outcomes. The epidemic curve indicated a significant reduction in confirmed cases from week 46 until the end of dengue outbreak. This can be attributed to the implementation of efficient response and control strategies during the period, which included enhancing awareness among urban political and administrative officials regarding environmental sanitation (wastewater treatment and management, tyre disposal, etc.), pesticide application in proximity to concessions and mosquito-prone areas, community engagement, effective communication (to avert dengue fever, safeguard oneself from mosquito bites by donning long-sleeved attire, utilizing insecticide-treated mosquito nets, and fitting insect screens on windows), and robust surveillance. Comparatively, case fatality rate of 0.43% in Africa [

25], our results showed a higher case fatality in this first dengue outbreak in Chad. This could be explained by poor healthcare infrastructure, delayed or misdiagnosed, and the unique features of the epidemic, as well as the health system's inability to prepare for the illness and its potential for grave effects, are all possible causes of a CFR in a dengue outbreak in Chad.

In univariable analysis, patients with fever, arthralgia, headache, and myalgia and those staying in areas where vectors were present were at increased risk of being confirmed dengue cases. Our results were in the line with a large study conducted in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay, among 1716 confirmed dengue cases, 90.1% (

n = 1546) of patients experienced myalgia [

26]. In both univariable and multivariable analysis, our study revealed that health centers had lower reduction of finding confirmed dengue cases compared to the association of community. Studies have shown that significant associations were found between practices for control and community shared information during dengue outbreak, community link with health department, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and other agencies [

6,

27]. Our results showed the importance of communities’ involvement in finding dengue cases during an outbreak. An association with case detection in the community rather than in health centres has important implications for a dengue prevention approach. Relying entirely on health facility-based monitoring may result in significant underreporting and a skewed picture of the outbreak's real extent and dynamics. Instead, a strong plan must be built on a mix of active and passive monitoring, with a focus on community-based measures to capture the whole picture of the epidemic. Our results also revealed that the combination of case definition/RDT showed high specificity and specificity. This combination was able to correctly identify confirmed dengue cases.

However, its ability to correctly identify dengue confirmed cases was low, as indicated by the low PPV. A low PPV indicates that a large percentage of the positive test findings are false positives, indicating that the patient does not have the condition. This study demonstrated that a well-defined case definition associated with RDT can effectively screen cases during a dengue outbreak. This could be useful as rapid case finding and adequate therapy are crucial for minimizing disease severity and fatal outcomes.

Although the measures of outbreak prevention control implemented during the initial outbreak of dengue were effective, as seen by the overall results. Nonetheless, multiple challenges were identified. With its complex epidemiology, intertwining with existing humanitarian crises in Chad and expansion of vector distribution due to climate change and mobility, dengue epidemics may create a public health perfect storm in Africa in general and in Chad particularly. Knowing that the rapid spread of dengue in recent years is an alarming trend that requires a coordinated response from all sectors and across borders in Chad. This study should serve as a lesson to learn for future dengue outbreaks in Chad. Recently, the WHO launched the SPRP for dengue and other Aedes mosquito-borne arboviral diseases. By promoting a coordinated global response, the Plan aims to reduce the burden of disease, suffering and death from dengue and other Aedes mosquito-borne arboviral diseases [

6]. Using a regional, whole-of-society approach, the Plan outlines priority actions to combat transmission and makes recommendations to affected countries in a range of areas, including disease surveillance, laboratory activities, vector control, community mobilization, clinical management and research and development [

6]. The SPRP includes five key elements that are essential for a successful response to the outbreak [

6]: emergency coordination, collaborative surveillance, community protection, safe and scalable care, and access to countermeasures [

6]. Routine surveillance is the backbone of dengue information, but there are other tools that strengthen the information system. These systems either contribute with additional alarm signals or increase data quality and timeliness. The potential value of enhanced surveillance lies in combining tools that complement the routine reporting but do not replace it. Enhanced surveillance during the inter-epidemic period includes: a) epidemiological sub-analysis of routinely reported data b) syndromic surveillance c) laboratory-based dengue reporting d) other active surveillance approaches. The options for enhanced surveillance to be selected by countries are presented below [

28]. As a summary, dengue control and prevention programs provide a compelling case study for the effective application of the One Health approach. The One Health approach could contribute to the global fight against dengue, emphasizing the need for collaborative and holistic approaches in public health initiatives [

29]. During the inaugural dengue outbreak in Chad, the circulating serotype was found to be DENV-1, genotype III. This idea should be explored and may be a way of controlling future dengue outbreaks in Chad and Africa in general. Given that many dengue virus infections cause just a mild influenza-like illness and that more than 80% of cases in refugees may be asymptomatic, improving surveillance, emergency planning, and response in the early stages of the outbreak is critical. The operational and strategic recommendations for improving dengue monitoring and preventing and controlling future outbreaks in Chad include strengthening passive surveillance, including syndromic surveillance, improving laboratory support, and utilizing digital health tools. Create and maintain a well-coordinated database and surveillance system, focusing on early identification, prediction, and monitoring of dengue transmission. Implement community engagement and education programs, and involve youth in preventative measures.

Abbreviations

ALT: alanine aminotransferase, ASAT: aspartate aminotransferase, CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COUSP-PHEOC: Activation of the Public Health Emergency Operations Center, COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, DENV: serotype of the dengue virus, ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, HI, house index, IMS: Incident Management System, IgM: Immunoglobulin M, LaBiEp: National Laboratory for Biosafety and Epidemics, MILDA: Distribution of mosquito nets, MODS: multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, MSPP: The Ministry of Public Health and Prevention, NGOs: non-governmental organizations, NPV: negative predictive value, ORs: odds ratios, PPV: positive predictive value, REDISSE: Regional Disease Surveillance Systems Enhancement (REDISSE), RT-PCR: Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, SITREP: situation reports, SGI: Incident Management System, SPRP: Global Strategic Preparedness, Readiness and Response Plan, VIF: variance inflation factor, WHO: World Health Organization