Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminary Concept of Deep Research

2.1. What is Deep Research

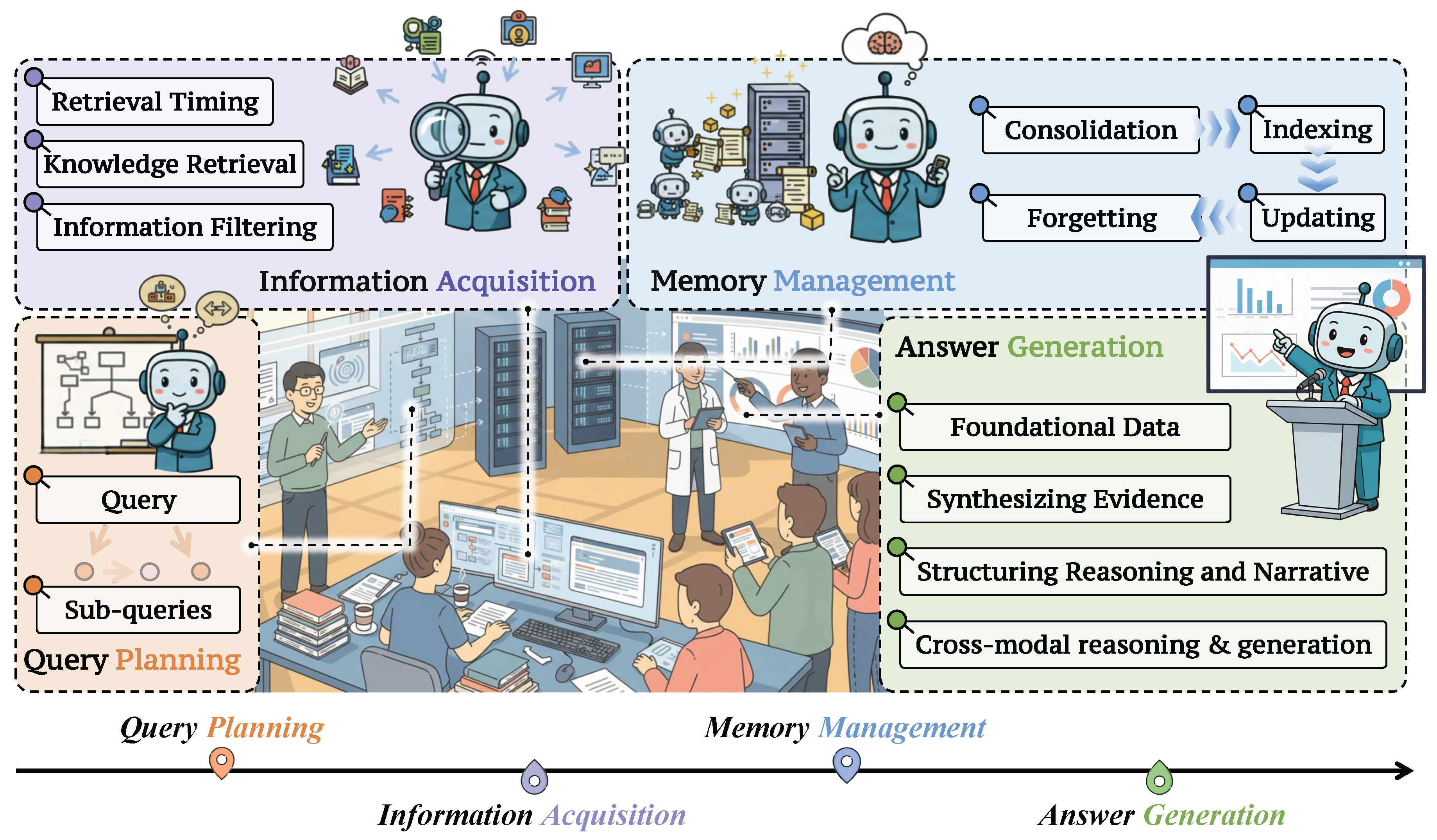

2.2. Understanding Deep Research from Three Phases

- Phase I: Agentic Search. Phase I systems specialize in finding the correct sources and extracting answers with minimal synthesis. They typically reformulate the user query (via rewriting or decomposition) to improve recall, retrieve and re-rank candidate documents, apply lightweight filtering or compression, and produce concise answers supported by explicit citations. The emphasis is on faithfulness to retrieved content and predictable runtime. Representative applications include open-domain question answering [168,220], multi-hop question answering [171,175,177], and other information-seeking tasks [178,221,222,223,224] where truth is localized to a small set of sources. Evaluation prioritizes retrieval recall@k and answer exact matching, complemented by citation correctness and end-to-end latency, reflecting the phase’s focus on accuracy-per-token and operational efficiency.

- Phase II: Integrated Research. Phase II systems move beyond isolated facts to produce coherent, structured reports that integrate heterogeneous evidence while managing conflicts and uncertainty. The research loop becomes explicitly iterative: systems plan sub-questions, retrieve and extract key evidence from various raw content (e.g., HTML [92], tables [225,226], and charts [227,227]), and ultimately synthesize comprehensive, narrative reports. The most commonly-used applications include market and competitive analysis [228,229], policy briefs [230], itinerary design under constraints [231], and other long-horizon question answering [16,181,184,186]. Accordingly, evaluation shifts from superficial short-form lexical matching to long-form quality, including: fine-grained factuality [232,233], verified citations [234,235], structural coherence [236], key points coverage [237]. Phase II thus trades a modest increase in compute and complexity for substantial gains in clarity, coverage, and decision support.

- Phase III: Full-stack AI Scientist. Phase III aims at advancing scientific understanding and creation beyond mere information aggregation, representing a broader and more ambitious stage of DR In this phase, DR agents are expected not only to aggregate evidence but also to generate hypotheses [238], conduct experimental validation or ablation studies [239], critique existing claims [219], and propose novel perspectives [212]. Common applications include paper reviewing [219,240,241], scientific discovery [242,243,244], and experiment automation [245,246]. Evaluation at this stage emphasizes the novelty and insightfulness of the findings, the argumentative coherence, the reproducibility of claims (including the ability to re-derive results from cited sources or code), and calibrated uncertainty disclosure.

| Capability | Standard | Agentic | Integrated | Full-stack |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Key Feature) | RAG | Search | Research | AI Scientist |

| Search Engine Access | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Use of Various Tools (e.g., Web APIs) | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Code Execution for Experiment | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Reflection for Action Correction | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Task-solving Memory Management | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Innovation and Hypothesis Proposal | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Long-form Answer Generation & Validation | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 1-5[6pt/6pt] Action Space | Narrow | Broad | Broad | Broad |

| Reasoning Horizon | Single | Long-horizon | Long-horizon | Long-horizon |

| Workflow Organization | Fixed | Flexible | Flexible | Flexible |

| Output Form and Application | Short Span | Short Span | Report | Academic Paper |

2.3. Comparing Deep Research with RAG

- Flexible Interaction with the Digital World. Conventional RAG systems operate in a static retrieval loop, relying solely on pre-indexed corpora [247,248]. However, real-world tasks often require active interaction with dynamic environments such as search engines, web APIs, or even Code executors [239,245,249]. DR systems extend this paradigm by enabling LLMs to perform multi-step, tool-augmented interactions, allowing agents to access up-to-date information, execute operations, and verify hypotheses within a digital ecosystem.

- Long-horizon Planning with Autonomous Workflows. Complex research-like problems often require agents to coordinate multiple subtasks [184], manage task-solving context [250], and iteratively refine intermediate outcomes [109]. DR addresses this limitation through closed-loop control and multi-turn reasoning, allowing agents to autonomously plan, revise, and optimize their workflows toward long-horizon objectives.

- Reliable Language Interfaces for Open-ended Tasks. LLMs are prone to hallucination and inconsistency [251,252,253,254,255], particularly in open-ended settings. DR systems introduce verifiable mechanisms that align natural language outputs with grounded evidence, establishing a more reliable interface between human users and autonomous research agents.

3. Key Components in Deep Research System

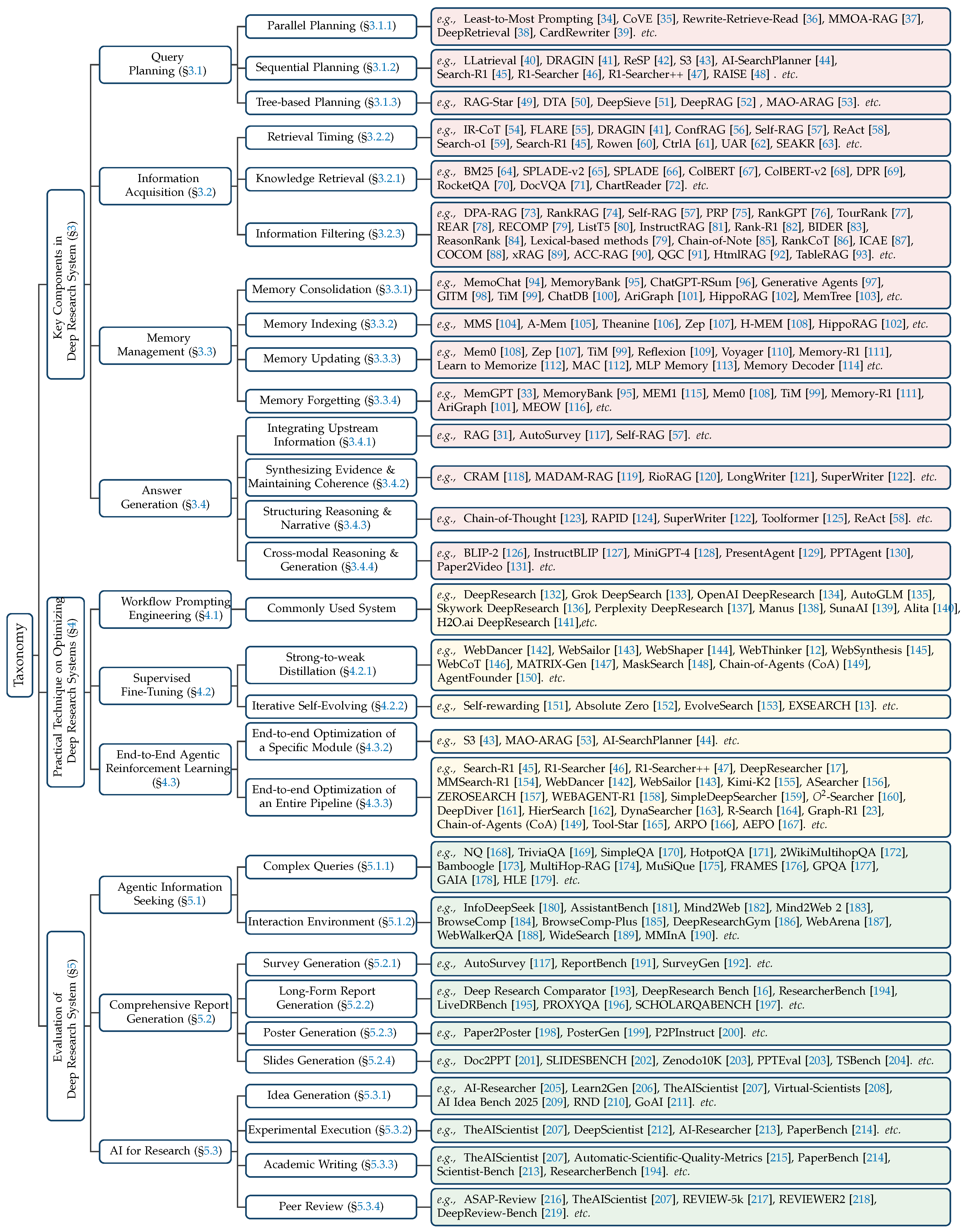

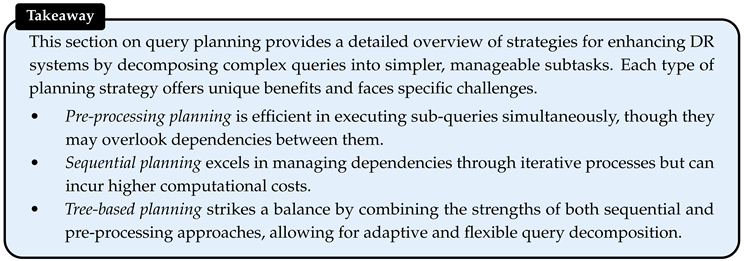

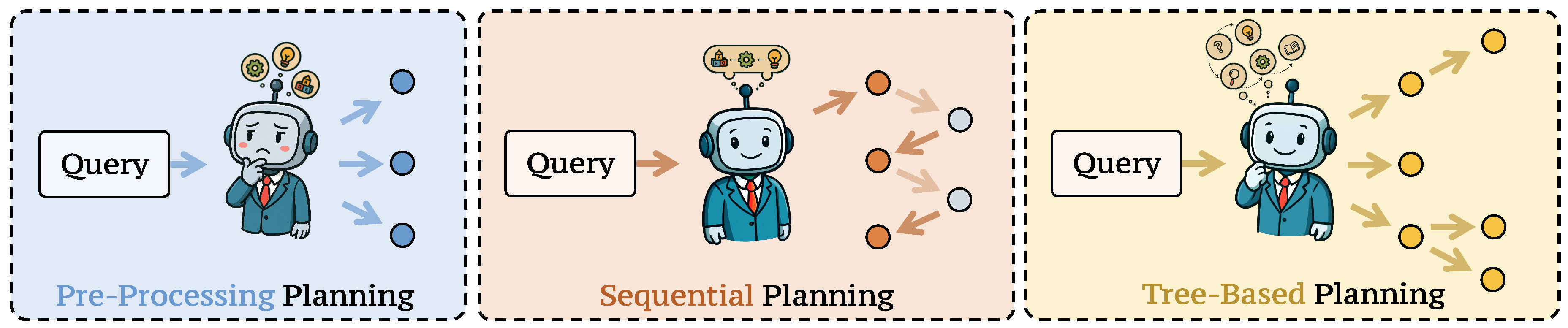

3.1. Query Planning

3.1.1. Parallel Planning

- Definition. As illustrated in Figure 3(a), parallel planning operates by rewriting or decomposing the original query into multiple sub-questions in a single pass, typically without iterative interaction with downstream components. The primary advantage of this strategy lies in its efficiency: simultaneous generation enables parallel processing of sub-queries.

- Representative Work. Early research typically instantiates parallel planning modules through heuristic approaches, most notably via prompt engineering [34,35] or training on manually annotated datasets. For example, Least-to-Most Prompting [34] guides GPT-3 [258] to decompose a complex task into an ordered sequence of simpler, self-contained sub-queries in a few-shot setting. Similarly, CoVE [35] prompts LLMs to first generate multiple independent sub-questions and then ground each one with well-established evidence in parallel, a strategy widely adopted in knowledge-intensive applications.

- Advantages & Disadvantages. Despite their efficiency, parallel planning has two primary limitations. First, they typically operate in a one-shot fashion, interacting with other modules (e.g., retriever, reasoner, aggregator) non-iteratively. As a result, they lack mechanisms to incorporate intermediate evidence, correct earlier decisions, or adaptively allocate computational resources. Second, they often ignore data and logical dependencies across sub-queries. Parallel execution assumes conditional independence, yet many real-world queries involve sequential reasoning in which later subtasks depend on the resolution of earlier ones. This can result in ill-posed or unanswerable sub-queries due to missing contextual information.

3.1.2. Sequential Planning

- Definition. As illustrated in Figure 3(b), the sequential planning decomposes the original query through multiple iterative steps, where each round of decomposition builds upon the outputs of previous rounds. At each stage, the sequential planning may invoke different modules or external tools to process intermediate results, enabling a dynamic, feedback-driven reasoning process. This multi-turn interaction allows the sequential planning to perform logically dependent query decompositions that are often intractable for pre-processing planning, which typically assumes conditional independence among sub-queries. By incorporating intermediate evidence and adapting the query trajectory accordingly, sequential planning is particularly well-suited for complex tasks that require stepwise inference, disambiguation, or progressive information gathering.

- Representative Work. The sequential planning is often used to provide a series of sub-queries for the external knowledge needed in a step-by-step manner, which has been widely used in iterative QA systems [40,41,42]. For example, LLatrieval [40] introduces an iterative query planner that, whenever the current documents fail verification, leverages the LLM to pinpoint missing knowledge and generate a new query, either a question or a pseudo-passage, to retrieve supplementary evidence, repeating the cycle until the accumulated context fully supports a verifiable answer. DRAGIN [41] introduces a query planner that can utilize the self-attention scores to select the most context-relevant tokens from the entire generation history and reformulate them into a concise and focused query. This dynamic, attention-driven approach produces more accurate queries compared to the static last sentence or last n tokens strategies in previous methods, resulting in higher-quality retrieved knowledge and improved downstream generation. In ReSP [42], the query planner dynamically guides each retrieval iteration by formulating novel sub-questions explicitly targeted at identified information gaps whenever the currently accumulated evidence is deemed insufficient. By conditioning this reformulation process on both global and local memory states and by disallowing previously issued sub-questions, the approach mitigates the risks of over-planning and redundant retrieval. This design ensures that each newly generated query substantially contributes to advancing the multi-hop reasoning trajectory toward the final answer. RAISE [48] sequentially decomposes a scientific question into sub-problems, generates logic-aware queries for each, and retrieves step-specific knowledge to drive planning and reasoning. Additionally, S3 [43] and AI-SearchPlanner [44] both adopt sequential decision-making to control when and how to propose retrieval queries during multi-turn search. At each turn, the sequential planner evaluates the evolving evidence state and decides whether to retrieve additional context or to stop. Besides, more recent studies, including Search-R1 [45], R1-Searcher [46,47] integrate a sequential planning strategy into an end-to-end, multi-turn search framework, thereby leveraging LLMs’ internal reasoning for query planning.

- Advantages & Disadvantages. Sequential planning enables dynamic, context-aware reasoning and fine-grained query reformulation, thereby facilitating more accurate acquisition of external knowledge. However, excessive reasoning turns or overly long reasoning chains can incur substantial computational costs and latency. In addition, an increased number of turns may introduce cumulative noise and error propagation, potentially causing instability during reinforcement learning training.

3.1.3. Tree-Based Planning

- Definition. As illustrated in Figure 3(c), the tree-based planning integrates features of both parallel and sequential planning by recursively treating each sub-query as a node within a structured search space, typically represented as a tree or a directed acyclic graph (DAG) [260]. This structure enables the use of advanced search algorithms, such as Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) [261], to explore and refine potential reasoning paths. Compared to linear or flat decompositions, this approach supports more flexible and fine-grained decomposition of the original query, facilitating comprehensive knowledge acquisition.

- Representative Work. A representative example is RAG-Star [49], which leverages MCTS in conjunction with the Upper Confidence Bound for Trees (UCT) [262] to guide a query planner in the iterative decomposition of complex questions. At each iteration, the planning model selects the most promising node using the UCT criterion, expands it by generating a sub-query and corresponding answer using a language model, evaluates the quality of the expansion via a retrieval-based reward model, and back-propagates the resulting score. This iterative process grows a reasoning tree of sub-queries until a satisfactory final answer is obtained. Other examples include DTA [50] and DeepSieve [51], which use a tree-based planner to restructure sequential reasoning traces into a DAG. This design enables the planning to aggregate intermediate answers along multiple branches and improves the model’s ability to capture both hierarchical and non-linear dependencies across sub-tasks. DeepRAG [52] introduces tree-based planning via binary-tree exploration to iteratively decompose queries and decide parametric vs. retrieved reasoning, yielding large accuracy gains with fewer retrievals. More recently, MAO-ARAG [53] trains a planning agent that can dynamically orchestrate multiple, diverse query reformulation modules through a DAG structure. This adaptive workflow enables comprehensive query decomposition to enhance performance.

- Advantages & Disadvantages. Tree-based planning integrates the strengths of parallel and sequential planning. It facilitates the decomposition of interdependent sub-queries and supports local parallel execution, striking an effective balance between efficiency and effectiveness. Nevertheless, training a robust Tree-based Planning module is challenging, requiring precise dependency modeling, careful trade-offs between speed and quality, addressing data scarcity, and tackling credit assignment issues in reinforcement learning.

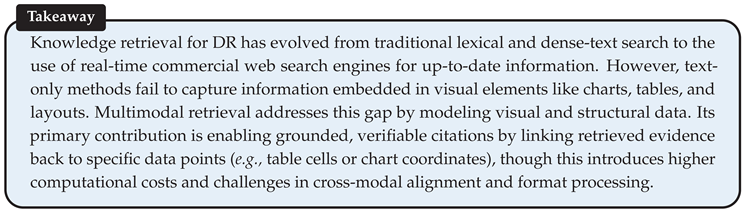

3.2. Information Acquisition

3.2.1. Retrieval Tools

- Definition. In the context of DR, retrieval tools [266,267,268] are used to identify relevant information from large-scale corpora in response to a query, typically containing indexing and search techniques. Within typical DR workflows, retrieval serves as a core mechanism for bridging knowledge gaps by surfacing candidate evidence that can then be checked for accuracy, filtered for relevance, or combined into a coherent answer. Below, we systematically review widely adopted retrieval techniques, organized by modality: (i) text-only retrieval, and (ii) multimodal retrieval.

- Text Retrieval. Conceptually, modern text retrieval can be organized into three families: (i) lexical retrieval, (ii) semantic retrieval, and (iii) commercial web search. Lexical and semantic retrieval are typically implemented on local resources, while commercial web search is typically accessed only via paid APIs. Specifically, lexical retrieval refers to methods that match documents based on exact term overlaps and statistical term weighting, including traditional approaches like TF-IDF and BM25 [64], as well as neural sparse models that learn to expand queries and documents with relevant terms while maintaining interpretable inverted-index structures [65,66,67,68,69,70,269,68].

- Multimodal Retrieval. Multimodal retrieval aims to mine multimodal information, including text, layout, and visuals (figures, tables, charts), and to preserve grounded pointers (spans, cells, coordinates) for verifiable citation, while maximizing recall under tight latency to support iterative DR. Multimodal information retrieval can be organized into three classes based on the primary type of information modality being indexed and retrieved: (i)text-aware retrieval with layout, which indexes titles, captions, callouts, and surrounding prose and leverages document understanding models (LayoutLM [281], Donut [282], DocVQA [71]) plus layout/metadata filters; (ii) visual retrieval via text–image similarity, which encodes figures and chart thumbnails with CLIP [283], SigLIP [284], or BLIP [285] and performs ANN search for text-to-image matching or composed image retrieval [286]; and (iii) structure-aware retrieval over parsed tables and charts, which indexes axes, legends, data marks, and table schemas to support grounded lookup of numeric facts and relations (e.g., ChartReader [72] or Chartformer [287]). These three approaches are typically combined: queries are searched across all indices simultaneously, with results fused using reciprocal-rank fusion [288] or cross-modal reranking to preserve grounded pointers for citations. Recent chart-focused VLMs [289,290,291,292] further enhance the quality of visual-textual features.

- Comparing Text Retrieval and Multimodal Retrieval. Compared to text-only retrieval, multimodal retrieval provides several key advantages. First, it captures visually encoded information and numeric trends that text-based methods often overlook, and facilitates cross-modal verification through hybrid fusion [288]. Second, it enables grounded citations using techniques such as layout parsing (e.g., LayoutLM [281], Donut [282]) and chart understanding (e.g., ChartReader [72] or Chartformer [287]). However, multimodal retrieval also presents several challenges, including increased computational costs for visual processing [283,284], sensitivity to OCR errors and variations in chart formats [293,294], and the complexity of aligning information across different modalities.

3.2.2. Retrieval Timing

- Definition. Retrieval timing refers to determining when a model should trigger retrieval tools during information seeking, which is also known as adaptive retrieval [60,63,295]. Because the quality of retrieved documents is not guaranteed, blindly performing retrieval at every step is often suboptimal [13,296,297]. Retrieval introduces additional computational overhead, and low-quality or irrelevant documents may even mislead the model or degrade its reasoning performance [256]. Consequently, adaptive retrieval aims to invoke retrieval only when the model lacks sufficient knowledge, which requires the model to recognize its own knowledge boundaries [298,299,300,301], i.e., knowing what it knows and what it does not.

-

Confidence Estimation as a Proxy for Boundary Perception. There are extensive works that investigate LLMs’ perception of their knowledge boundaries. The degree to which a model perceives its boundaries is typically measured by the alignment between its confidence and factual correctness. Since factual correctness is typically evaluated by comparing the model’s generated answer with the ground-truth answer, existing studies focus on how to measure the model’s confidence, which can be broadly divided into four categories.

- Probabilistic Confidence. This line of work treats a model’s token-level generation probabilities as its confidence in the answer [302,303,304,305,306,307,308]. Prior to the emergence of LLMs, a line of work had already shown that neural networks tend to be poorly calibrated, often producing overconfident predictions even when incorrect [302,303,304]. More recently, some research[305,306] reported that LLMs can be well calibrated on structured tasks such as multi-choice question answering or appropriate prompts, but for open-ended generation tasks, predicted probabilities still diverge from actual correctness. To address this gap, Duan et al. [308] proposed SAR, which computes confidence by focusing on important tokens, while Kuhn et al. [307] introduced semantic uncertainty, which estimates confidence from the consistency of outputs across multiple generations.

- Consistency-based Confidence. Since probabilistic confidence often fails to capture a model’s semantic certainty and is inapplicable to black-box models without accessible generation probabilities, recent works represent confidence via semantic consistency across multiple responses [60,307,309,310,311]. The key idea is that a confident model should generate highly consistent answers across runs. Fomicheva et al. [309] first measured consistency through lexical similarity, while later studies used NLI (i.e., natural language inference) models or LLMs to assess semantic consistency [307,310]. To address the issue of consistent but incorrect answers, Zhang et al. [311] measure consistency across different models, as incorrect answers tend to vary between models, whereas correct ones align. Ding et al. [60] further extended this idea to multilingual settings.

- Confidence Estimation Based on Internal States. LLMs’ internal states have been shown to capture the factuality of their generated content [312,313,314,315,316,317]. Azaria and Mitchell [312] first discovered that internal states can signal models’ judgment of textual factuality. Subsequent studies [313,314] found that internal states after response generation reflect the factuality of self-produced answers. More recently, Wang et al. [315] and Ni et al. [316] demonstrated that factuality-related signals already exist in the pre-generation states, enabling the prediction of whether the output will be correct.

- Verbalized Confidence. Several studies explore enabling LLMs to express confidence in natural language, akin to humans, viewing such verbalization as a sign of intelligence [56,318,319,320,321,322,323]. Yin et al. [319] and Ni et al. [56] examined whether LLMs can identify unanswerable questions, finding partial ability but persistent overconfidence. Other works [320,321] investigated fine-grained confidence expression. Xiong et al. [321] offered the first comprehensive study for black-box models, while Tian et al. [320] proposed generating multiple answers per pass for more accurate estimation. Beyond prompting, some methods explicitly train models to verbalize confidence [318,322,323], with Lin et al. [318] introducing this idea and using correctness-based supervision.

-

Representative Adaptive Retrieval Approaches. Deep research systems typically involve iterative interactions between model inference and external document retrieval, differing mainly in how they determine when to retrieve. Early works such as IR-CoT [54] enforce retrieval after every reasoning step, ensuring continual grounding in external knowledge but at the cost of efficiency. Building on insights from studies of models’ perceptions of their own knowledge boundaries, recent approaches treat retrieval as a model-issued action, enabling the model to perform it dynamically only when needed. Similar to techniques in confidence estimation, these methods assess whether the model can answer a question correctly given the current context and perform retrieval when knowledge is deemed insufficient. They can be broadly categorized into four paradigms.

- Probabilistic Strategy. It triggers retrieval based on token-generation probabilities: when the model produces a token with low confidence, retrieval is initiated [41,55].

- Consistency-based Strategy. Recognizing that both token-level probabilities and single-model self-consistency may fail to capture true semantic uncertainty, Rowen [60] evaluates consistency across responses generated by multiple models and languages, triggering retrieval when cross-model or cross-lingual agreement is low.

- Internal States Probing. CtrlA [61], UAR [62], and SEAKR [63] further propose that compared to generated responses, a model’s internal states provide a more faithful reflection of its confidence, using them to guide adaptive retrieval decisions.

- Verbalized Strategy. It enables the model to directly express its confidence via natural language. These methods typically generate special tokens directly in the response to indicate the need for retrieval. ReAct [58] directly prompts the model to generate corresponding action text when retrieval is needed. Self-RAG [57] trains the model to explicitly express uncertainty through the special token (i.e., <retrieve>), signaling the need for retrieval. With LLMs’ growing reasoning capacity, recent research has shifted toward determining retrieval timing through reasoning and reflection. Search-o1 [59] introduces a Reason-in-Documents module, which prompts the model to selectively invoke search during reasoning. Search-R1 [45] further frames retrieval as part of the environment and employs reinforcement learning to jointly optimize both when and what to retrieve.

-

- Collectively, these methods trace an evolution from fixed or per-step retrieval (e.g., IR-CoT [54]) to dynamically triggered retrieval (e.g., ReAct [58], Self-RAG [57], Search-o1 [59]), and finally to RL–based systems that explicitly train retrieval policies (e.g., Search-R1 [45]).

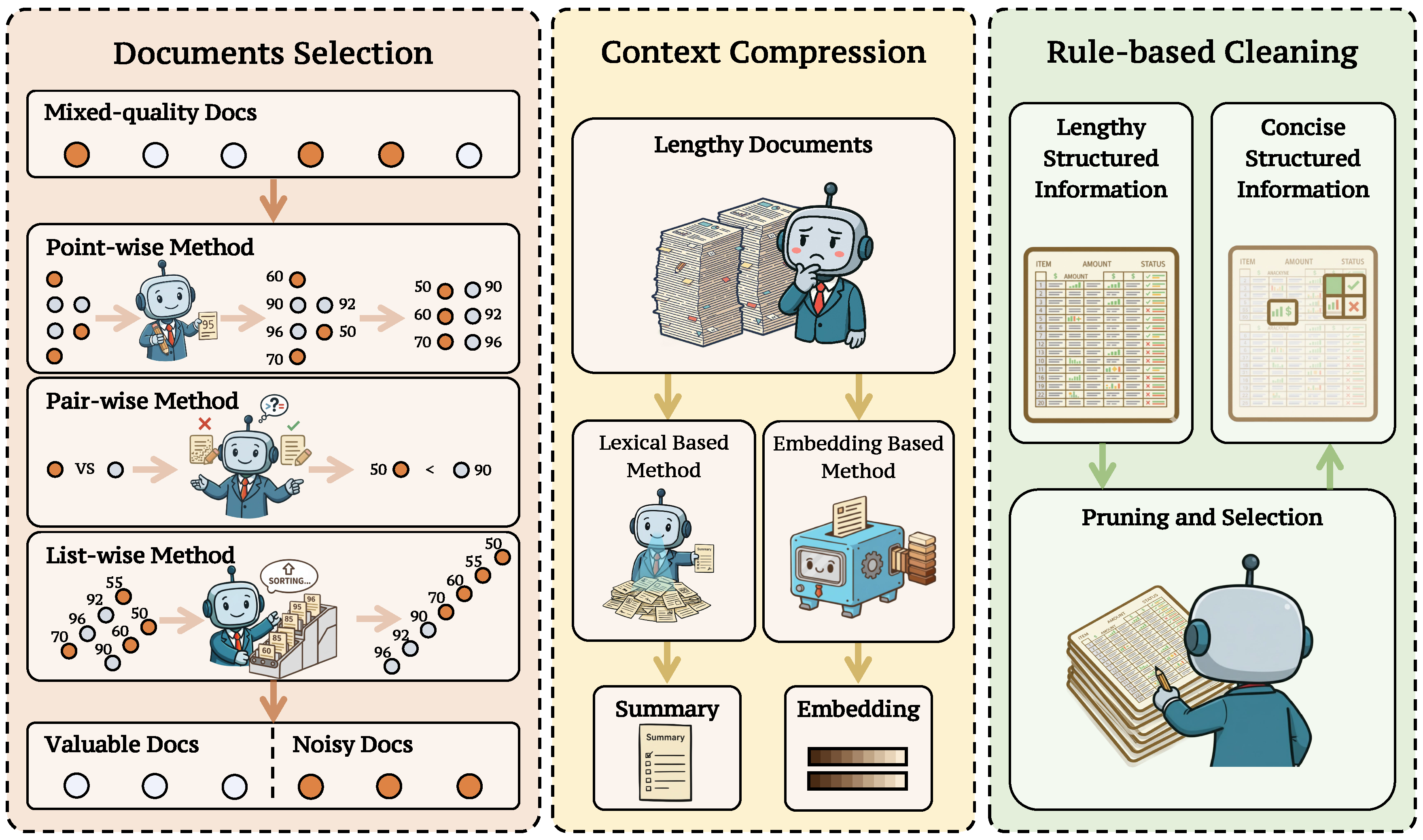

3.2.3. Information Filtering

- Definition. Information filtering refers to the process of selecting, refining, or transforming retrieved documents so that only the most relevant and reliable evidence is passed to subsequent steps. Since retrieval tools are not perfect, the retrieved information often contains considerable noise [324,325,326]. This includes the content that is entirely irrelevant to the query or plausible-looking statements that nevertheless provide incorrect or misleading context. As shown in prior work [324,327], LLMs are highly sensitive to such noise; without additional filtering or optimization, they can be easily misled into generating incorrect or hallucinated responses. Figure 4 summarizes three information filtering approaches: (i) Document Selection, (ii) Context Compression, and (iii) Rule-based Cleaning.

-

Document Selection. Document selection aims to rank a set of candidate documents based on their relevance and usefulness to the query, selecting the top-k helpful documents for question answering [74,79,81]. This selection operation reduces the impact of noisy documents on LLMs, improving the question-answering accuracy in downstream tasks. Below, we review three document selection strategies: point-wise selection, pair-wise selection, and list-wise selection.

- Point-wise Selection. Given an initially retrieved document list, point-wise methods independently score each candidate document. The most common approach involves fine-tuning an embedding model (e.g., BGE [328]) that encodes the query and each document separately, after which their relevance is estimated via inner-product similarity [79,329]. Another widely adopted strategy employs a cross encoder, which takes the concatenation of the query and a document as input and directly predicts a binary relevance score [73,78]. More recently, several studies have leveraged LLMs’ natural language understanding capabilities for relevance assessment. These methods train LLMs to output special tokens, such as <ISREL> [57] or the identifier True [74], to indicate whether an input document is relevant to the query.

- Pair-wise Selection. Unlike the point-wise approach, which assigns an absolute relevance score, the pair-wise method compares the relevance of two input candidate information snippets (typically two documents) and predicts which one is more relevant to the query. Pair-wise selection is less common than point-wise selection. A representative work is PRP [75], which adopts a pairwise-ranking-prompting approach. In PRP, the LLM receives a query and two candidate documents to decide which is more relevant, and the final ranking list is then obtained using a heapsort algorithm. To mitigate positional bias, PRP performs the comparison twice, swapping the document order each time, and aggregates the results to yield a more stable judgment.

- List-wise methods.Given a document list, a list-wise selection strategy directly selects the final set of relevant documents from the candidate list. A representative work is RankGPT [76], which feeds the entire candidate sequence into an LLM and leverages prompt engineering to produce a global ranking. In addition to RankGPT, other work, such as TourRank [77], uses a tournament-inspired strategy to generate a robust ranking list [77,80]. ListT5 [80] proposes a list re-ranking method based on the Fusion-in-Decoder (FiD) [330] architecture, which independently encodes multiple documents in parallel and orders them by relevance, mitigating positional sensitivity while preserving efficiency. For large document sets, it builds m-ary tournament trees to group, rank, and merge results in parallel. Recently, more and more work has employed the reasoning model for list-wise document selection, advancing document selection by explicitly modeling a chain of thought. For example, InstructRAG [81] trains an LLM to generate detailed rationales via instruction tuning [331], directly judging the usefulness of each document in the raw retrieved document list. Rank-R1 [82] employs the reinforcement learning algorithm GRPO [332] to train the LLM, enabling it to learn how to select the documents most relevant to a query from a list of candidates. ReasonRank [84] empowers a list-wise selection model through a proposed multi-view ranking-based GRPO [332], training an LLM on automatically synthesized multi-domain training data.

-

Content Compression. Content Compression aims to remove redundant or irrelevant information from retrieved knowledge, thereby increasing the density of useful content within the model’s context. Existing approaches primarily fall into two categories: lexical-based and embedding-based methods.

- Lexical-based methods condense retrieved text into concise natural language, aiming to only include the key point related to the given query [79,333]. Representative works such as RECOMP [79] fine-tune a smaller, open-source LLM to summarize the input retrieved documents, where the ground truth is synthesized by prompting powerful commercial LLMs like GPT-4 [334]. Chain-of-Note [85] introduces a reading-notes mechanism that compels the model to assess the relevance of retrieved documents to the query and extract the most critical information before generating an answer, with training data annotated by GPT-4 and further validated through human evaluation. Other work, like BIDER [83], eliminates reliance on external model distillation by synthesizing Key Supporting Evidence (KSE) for each document, using it for compressor SFT, and further optimizing with PPO based on gains in answer correctness. Zhu et al. [335] argue that previous compressors optimized with log-likelihood objectives failed to precisely define the scope of useful information, resulting in residual noise. They proposed a noise-filtering approach grounded in the information bottleneck principle, aiming to maximize the mutual information between the compressed content and the target output while minimizing it between the compressed content and retrieved passages. RankCoT [86] implicitly learns document reranking during information refinement. It first employs self-reflection to generate summary candidates for each document. In subsequent DPO [259] training, the compression model is encouraged to assign higher probabilities to correct summaries when all documents are fed in, thereby inducing implicit reranking in the final summarization.

- Embedding-based methods compress context into dense embedding sequences [90,336,337]. Because embedding sequences can store information flexibly, embedding-based methods can be more efficient and effective than lexical-based methods. ICAE [87] uses an encoder to compress context into fixed-length embedding sequences and designs training tasks to align the embedding space with the answer generation model. COCOM [88] jointly fine-tunes the encoder and answer generation model, enhancing the latter’s ability to capture the semantics of embeddings. xRAG [89] focuses on achieving extreme compression rates. It introduces a lightweight bridging module, initialized with a two-layer MLP and trained through paraphrase pretraining and context-aware instruction tuning. This module projects the document embedding vectors originally used for initial retrieval into a single token in the answer generation model’s representation space, achieving contextual compression with only a single additional token. ACC-RAG [90] adapts compression rates for different documents by employing a hierarchical compressor to produce multi-granularity embedding sequences and dynamically selecting compression rates based on query complexity. Similarly, QGC [91] adjusts compression rates based on query characteristics, dynamically selecting different rates for different documents based on their relevance to the query.

- Rule-based Cleaning. Rule-based methods are effective for cleaning externally sourced information with specific structures. For example, HtmlRAG [92] applies rule-based compression to remove structurally present but semantically empty elements, such as CSS styling and JavaScript code, from retrieved web pages. This is combined with a two-stage block-tree pruning strategy that first uses embeddings for coarse pruning, followed by a generative model for fine-grained pruning. Separately, TableRAG [93] accurately extracts core table information through schema retrieval, which identifies key column names and data types, and cell retrieval, which locates high-frequency cell value pairs. This method addresses the challenges of context length limitations and information loss in large table understanding.

- Advantages & Disadvantages. Filtering the retrieved knowledge is a simple yet effective strategy to enhance the performance of DR systems, as widely demonstrated in previous work [73,79,92]. However, incorporating an additional filtering module typically incurs additional computational costs and increased latency [325]. Moreover, overly filtering may remove useful or even correct information, thereby degrading model performance. Therefore, balancing filtering precision and information retention is crucial for building efficient and reliable DR systems.

3.3. Memory Management

- Definition. Memory management is a foundational component of advanced DR architectures, which governs the dynamic lifecycle of context used by DR agents in complex, long-horizon tasks [338,339,340], aiming to maintain coherent and relevant task-solving context [341,342,343].

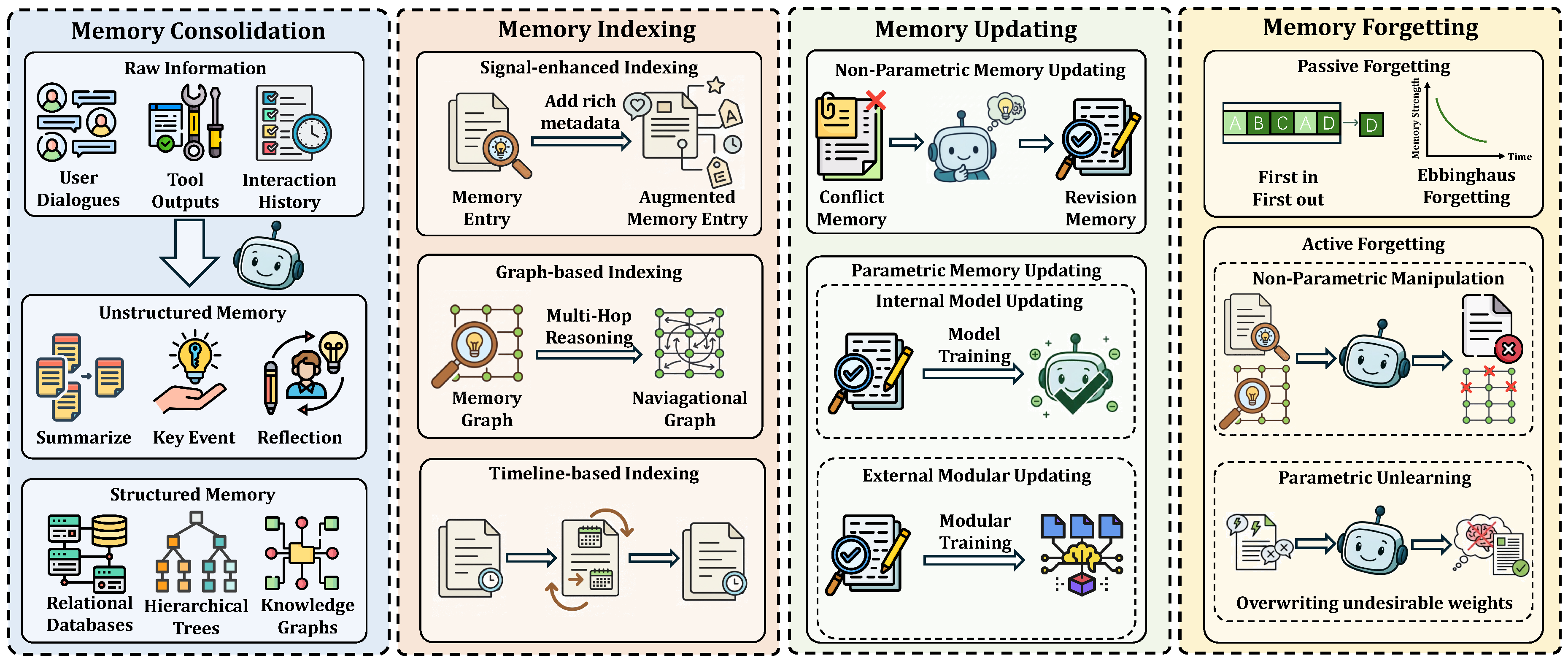

- Core Operation. As illustrated in Figure 5, memory management typically involves four core operations: consolidation, indexing, updating, and forgetting. Consolidation converts short-term experiences into durable representations that form the basis for later indexing. Indexing organizes these representations into retrieval structures that support efficient recall during problem solving. Updating refines or corrects stored knowledge, whereas forgetting selectively removes outdated or irrelevant content to reduce interference. In the following sections, we discuss consolidation, indexing, updating, and forgetting in detail.

3.3.1. Memory Consolidation

- Definition. Memory consolidation is the process of transforming transient, short-term information, such as user dialogues or tool execution outputs, into stable, long-term representations [338,339,344]. Drawing an analogy to cognitive neuroscience, this process encodes and abstracts raw inputs to create durable memory engrams, laying the groundwork for efficient long-term storage and retrieval [338].

- Unstructured Memory Consolidation. This paradigm distills lengthy interaction histories or raw texts into high-level, concise summaries or key event logs. For example, MemoryBank [95] processes and distills conversations into a high-level summary of daily events, which helps in constructing a long-term user profile. Similarly, MemoChat [94] summarizes conversation segments by abstracting the main topics discussed, while ChatGPT-RSum [96] adopts a recursive summarization strategy to manage extended conversations. Other approaches focus on abstracting experiences; Generative Agents [97] utilize a reflection mechanism triggered by sufficient event accumulation to generate more abstract thoughts as new, consolidated memories. To create generalizable plans, GITM [98] summarizes key actions from multiple successful plans into a common reference memory.

- Structured Memory Consolidation. This paradigm transforms unstructured information into highly organized formats such as databases, graphs, or trees. This structural encoding is the primary act of consolidation, designed to capture complex inter-entity relationships and create an organized memory corpus. For instance, TiM [99] extracts entity relationships from raw information and stores them as tuples in a structured database. ChatDB [100] leverages a database as a form of symbolic memory, transforming raw inputs into a queryable, relational format. AriGraph [101] implements a memory graph where knowledge is represented as vertices and their interconnections as edges. Similarly, HippoRAG [102] constructs knowledge graphs over entities, phrases, and summaries to form an interconnected web of fragmented knowledge units. MemTree [103] builds and updates a tree structure by traversing from the root and deciding whether to deepen the tree with new information or create new leaf nodes based on semantic similarity. This hierarchical organization is the core of its consolidation strategy, enabling structured storage of memories.

3.3.2. Memory Indexing

- Definition. Memory indexing involves constructing a navigational map over a DR agent’s consolidated memories, analogous to a library’s catalog or a book’s index for efficient information retrieval [347]. Unlike memory consolidation, which focuses on the initial transformation of raw data into a durable format, indexing operates on already consolidated memories to create efficient, semantically rich retrieval pathways. This process builds auxiliary access structures that enhance retrieval not only in efficiency but also in relevance.

- Signal-enhanced Indexing. This paradigm augments consolidated memory entries with auxiliary metadata, including emotional context, topics, and keywords, which function as granular pivots for context-aware retrieval [104,352]. For instance, LongMemEval [353] enhances memory keys by integrating temporal and semantic signals to improve retrieval precision. Similarly, the Multiple Memory System (MMS) [104] decomposes experiences into discrete components, such as cognitive perspectives and semantic facts, thereby facilitating multifaceted retrieval strategies.

- Graph-based Indexing. This paradigm leverages a graph structure, where memories are nodes and their relationships are edges, as a sophisticated index. By representing memory networks in this way, agents can perform complex multi-hop reasoning by traversing chains of connections to locate information that is not explicitly linked to the initial query [108,354]. For instance, HippoRAG [102] uses lightweight knowledge graphs to explicitly model inter-memory relations, enabling structured, interpretable access. A-Mem [105] adopts a dynamic strategy where the agent autonomously links related memory notes, progressively growing a flexible access network.

- Timeline-based Indexing. This paradigm creates a temporal index by organizing memory entries along chronological or causal sequences. Such structuring provides a historical access pathway, which is essential for understanding progression, maintaining conversational coherence, and supporting lifelong learning [355]. For example, the Theanine system [106] arranges memories along evolving timelines to facilitate retrieval based on both relevance and temporal dynamics. Zep [107] introduces a bi-temporal model for its knowledge graph, indexing each fact with and timestamps, which allows the agent to navigate the memory based on temporal validity.

3.3.3. Memory Updating

- Definition. Memory updating is a core capability of DR agents, involving the reactivation and modification of existing knowledge in response to new information or environmental feedback [356,357,358]. This process is essential for maintaining the consistency, accuracy, and relevance of the agent’s internal world model, thereby enabling continual learning and adaptive behavior in dynamic environments [110,359].

-

Non-Parametric Memory Updating. Non-parametric memory, stored in external formats such as vector databases or structured files, is updated via explicit, discrete operations on the data itself. This approach offers flexibility and transparency. Key operations include:

- Integration and Conflict Updating. This operation focuses on incorporating new information and refining existing entries to maintain logical consistency. For example, the Mem0 framework employs an LLM to manage its knowledge base through explicit operations, such as adding new facts (ADD) or modifying existing entries with new details (UPDATE) to resolve inconsistencies [108]. To handle temporal conflicts, Zep updates its knowledge graph by modifying an existing fact’s effective time range, setting an invalidation timestamp () to reflect that a newer fact has superseded it [107]. Similarly, the TiM framework curates its memory by using MERGE operations to combine related facts into a more coherent representation [99]

- Self-Reflection Updating. Inspired by human memory reconsolidation, this paradigm enables agents to iteratively refine their knowledge by reflecting on past experiences [109,362]. Early systems like Reflexion [109] and Voyager [110] implement this through verbal self-correction and updates to a skill library. More dynamically, A-Mem [105] triggers a Memory Evolution process that re-evaluates and autonomously refines previously linked memories based on new contextual information.

-

Parametric Memory Updating. Parametric memory, encoded directly in a model’s weights, is updated by modifying internal representations. This is typically more complex and computationally intensive. Three main approaches have emerged:

- Global Updating. This approach integrates new knowledge by continuing model training on additional datasets [363]. While effective for large-scale adaptation, it is computationally expensive and prone to catastrophic forgetting [356]. To address this, instead of simply injecting factual knowledge, Memory-R1 trains a dedicated Memory Manager agent to learn an optimal policy for modification operations such as ADD and UPDATE, moving beyond heuristic rules [111]. Additionally, a recent framework refines this process by employing methods such as Direct Preference Optimization to fine-tune the model’s memory utilization strategy [112].

- Localized Updating. This technique modifies specific facts in the model’s parameters without requiring full retraining [360,361]. It is especially suited for online settings where rapid adaptation is needed, such as updating a user’s preference [357]. Methods typically follow a locate-and-edit strategy or use meta-learning to predict weight adjustments while preserving unrelated knowledge [357,361].

- Modular Updating. This emerging paradigm avoids the risks of continual weight modification by distilling knowledge into a dedicated, plug-and-play parametric module. Frameworks such as MLP Memory [113] and Memory Decoder [114] train a lightweight external module to imitate the output distribution of a non-parametric kNN retriever. This process effectively compiles a large corpus of external knowledge into the compact weights of the module. The resulting module can then be attached to any compatible LLM to provide specialized knowledge without modifying the base model’s parameters, thereby avoiding catastrophic forgetting and reducing the latency of real-time retrieval [113,114].

3.3.4. Memory Forgetting

- Definition. Forgetting constitutes a fundamental mechanism in advanced agent architectures, enabling the selective removal or suppression of outdated, irrelevant, or potentially erroneous memory content. Rather than a system defect, forgetting is a functional process critical for filtering noise, reclaiming finite storage resources, and mitigating interference between conflicting information. In contrast to memory updating, which modifies existing knowledge to improve its accuracy, forgetting is a subtractive process that streamlines the memory store by eliminating specific content. This process can be broadly categorized into passive and active mechanisms.

- Passive Forgetting. This simulates the natural decay of human memory, in which infrequently accessed or temporally irrelevant memories gradually lose prominence. This mechanism is particularly critical for managing the agent’s immediate working memory or context window. Implementations are typically governed by automated, time-based rules rather than explicit content analysis. For instance, MemGPT [33] employs a First-In-First-Out (FIFO) queue for recent interactions, automatically moving the oldest messages from the main context into long-term storage. MemoryBank [95] draws inspiration from the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve, in which memory traces decay over time unless reinforced, allowing the agent to naturally prioritize recent content. A more aggressive approach, MEM1 [115], employs a use-and-discard policy: after each interaction, the agent synthesizes essential information into a compact state and immediately discards all prior contextual data to maintain constant memory consumption.

-

Active Forgetting. Active forgetting involves the intentional and targeted removal or invalidation of specific memory content. This process is a deliberate action, often triggered by the detection of contradictions or the need to correct inaccurate information, and its implementation varies depending on the memory type.

- Non-Parametric Memory. Active forgetting in external memory stores involves direct data manipulation. For example, Mem0 [108] implements an explicit DELETE command to remove outdated or contradictory facts. Similarly, TiM [99] introduces a dedicated FORGET operation to actively purge irrelevant or incorrect thoughts from its memory cache. Reinforcement learning can also be used to train a specialized Memory Manager agent to autonomously decide when to execute a DELETE command, as seen in the Memory-R1 framework [111]. AriGraph [101] maintains a structured memory graph by removing outdated vertices and edges. Some systems employ non-destructive forgetting; the Zep architecture [107], for example, uses edge invalidation to assign an invalid timestamp to an outdated entry, effectively retiring it without permanent deletion.

- Parametric Memory. In this context, active forgetting is typically achieved through machine unlearning techniques that modify a model’s internal parameters to erase specific knowledge without full retraining. Approaches include locating and deactivating specific neurons or adjusting training objectives to promote the removal of targeted information. For example, MEOW [116] facilitates efficient forgetting by fine-tuning an LLM on generated contradictory facts, effectively overwriting undesirable memories stored in its weights.

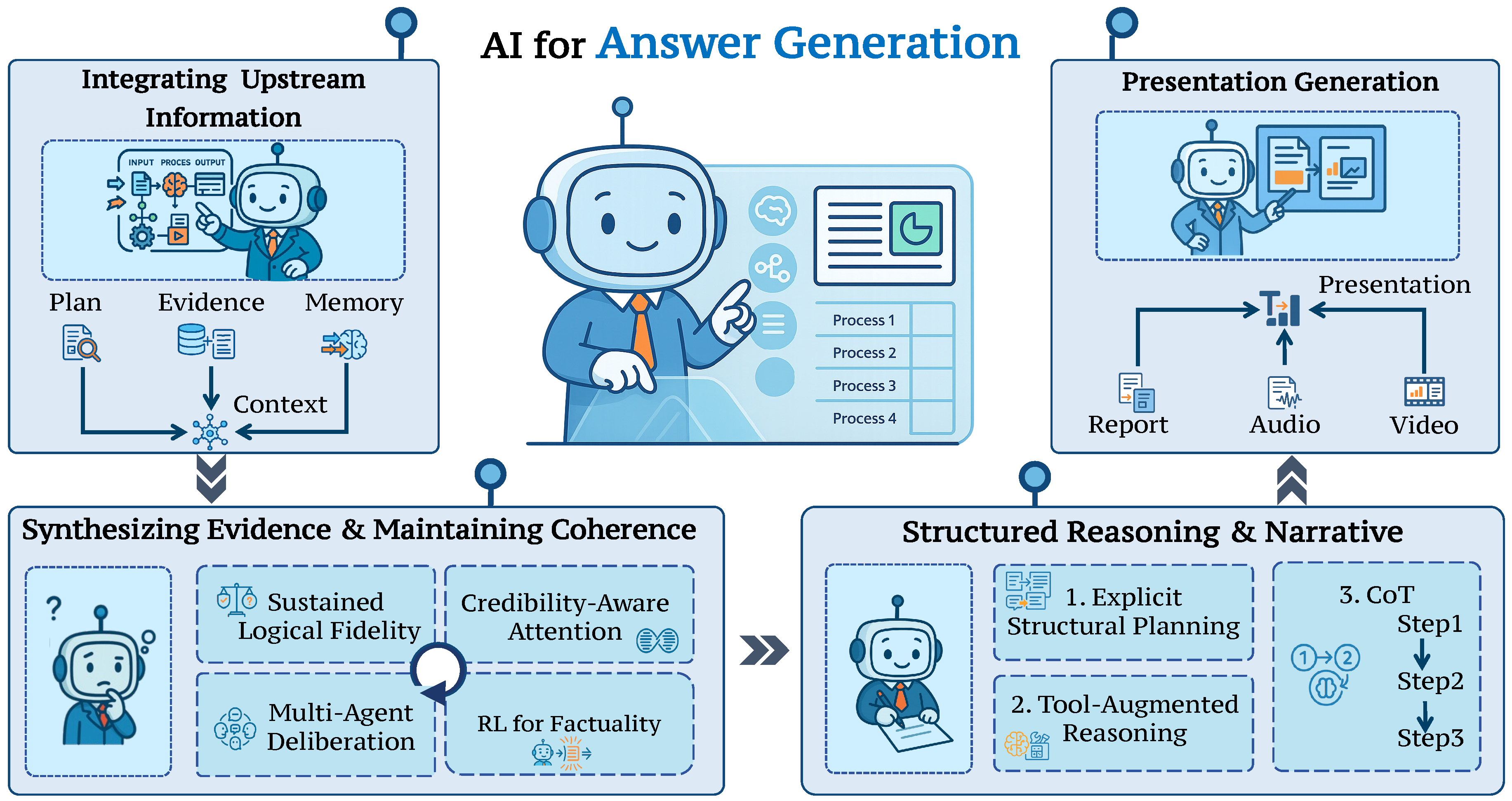

3.4. Answer Generation

- Definition. Answer generation typically represents the culminating stage of a DR system. It synthesizes information from upstream components, such as query planning (Section 3.1), information acquisition (Section 3.3.1), and memory systems (Section 3.3.1), and generates a coherent, comprehensive, and well-supported response that accurately reflects the user’s original intent.

3.4.1. Integrating Upstream Information

- Definition. The main principle of trustworthy answer generation is to ensure that every statement is grounded in verifiable external evidence. Thus, the first stage of answer generation is integrating information from its upstream components, including: the sub-queries from the query planning, the ranked and potentially conflicting evidence, and the evolving contextual state stored in memory.

3.4.2. Synthesizing Evidence and Maintaining Coherence

-

Resolving Conflicting Evidence. Research queries frequently surface contradictory sources, requiring the model to discriminate among varying levels of reliability. Building on fact-verification paradigms [368], recent systems adopt three major strategies.

- Credibility-Aware Attention: Instead of treating all retrieved information equally, this approach intelligently weighs evidence based on its source. The system assigns a higher score to information coming from more credible sources (e.g., a top-tier scientific journal) compared to less reliable ones (e.g., an unverified blog) [118]. This allows the model to prioritize trustworthy information while still considering relevant insights from a wider range of sources [369].

- Multi-Agent Deliberation: This strategy simulates an expert committee meeting to debate the evidence. Frameworks like MADAM-RAG [119] employ multiple independent AI agents, each tasked with analyzing the retrieved documents from a different perspective. Each agent forms its own assessment and conclusion. Afterwards, a final meta-reasoning step synthesizes these diverse viewpoints to forge a more robust and nuanced final answer, much like a panel of experts reaching a consensus [370].

- Reinforcement Learning for Factuality: This method trains the generator through a trial-and-error process that rewards factual accuracy [371]. A representative approach is RioRAG [120], in which an LLM receives a positive reward when it generates statements that are strongly and consistently supported by the provided evidence. Conversely, it is penalized for making unsubstantiated claims or statements that contradict the source material, shaping the model to inherently prefer generating factually grounded and reliable answers.

- Long-form Coherence and Information Density. Another key challenge is ensuring Sustained Informational Accuracy. Research answers are often lengthy, and maintaining a logical thread while avoiding repetition or verbosity is non-trivial. Let denote the maximum coherent length of a model’s output, and represent the average length of examples in its supervised fine-tuning dataset. SFT offers an intuitive approach to enhancing the long-form generation capabilities of large language models. However, LongWriter [121] empirically demonstrates that the maximum coherent length of a model’s output often scales with the average length of its fine-tuning samples, which can be formally expressed as [121]. To address this, LongWriter focuses on systematic training for extended generation, while others use reflection-driven processes to iteratively improve consistency [122]. Additionally, RioRAG [120] introduces a length-adaptive reward function to promote information density, which penalizes verbosity that fails to add informational value, preventing reward hacking through verbosity. Together, these techniques shift the focus of generation from mere content aggregation toward credible, concise, and coherent synthesis, laying the groundwork for structured reasoning.

3.4.3. Structuring Reasoning and Narrative

- Prompt-based Chain-of-Thought. This foundational approach focuses on eliciting intermediate reasoning steps before producing a final answer. The most prominent technique is Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting [123], which can be formally expressed as . This method enhances both interpretability and multi-step reasoning performance. Its applicability has been broadened by extensions such as zero-shot CoT [375] and Least-to-Most prompting [34].

- Explicit Structural Planning. More advanced systems move beyond simple linear chains to formalize the structure of the entire answer. For instance, RAPID [124] formalizes this process into three stages: (i) outline generation; (ii) outline refinement through evidence discovery; and (iii) plan-guided writing, where the outline forms a directed acyclic graph to support complex, non-linear argumentation. Similarly, SuperWriter [122] extends this idea by decoupling the reasoning and text-production phases and optimizing the entire process via hierarchical Direct Preference Optimization.

- Tool-Augmented Reasoning. This line of work enhances reasoning by dynamically interfacing with external resources. Representative work allows models to invoke external computational or retrieval tools dynamically, ensuring both analytic rigor and factual grounding [125,376,377,378,379].

3.4.4. Presentation Generation

4. Practical Techniques for Optimizing Deep Research Systems

4.1. Workflow Prompt Engineering

- Definition. A simple yet effective way to build a DR system is to construct a complex workflow that enables collaboration among multiple agents. In the most common setting, an orchestration agent coordinates a team of specialized worker agents, allowing them to operate in parallel on different aspects of a complex research task. To illustrate the key principles and design considerations behind such a DR workflow, we introduce Anthropic Deep Research [391] as a representative example.

4.1.1. Deep Research System of Anthropic

- Query Stratification and Planning. The orchestrator first analyzes the semantic type and difficulty of the input query (e.g., depth-first vs. breadth-first) to determine research strategy and allocate a corresponding budget of agents, tool calls, and synthesis passes.

- Delegation and Scaling. Effort scales with complexity: from 1–2 agents for factual lookups to up to 10 or more for multi-perspective analyses, each assigned with clear quotas and stopping criteria to enable dynamic budget reallocation.

- Task Decomposition and Prompt Specification. The main query is decomposed into modular subtasks, each encoded as a structured prompt specifying objectives, output schema, citation policy, and fallback actions to ensure autonomy with accountability.

- Tool Selection and Evidence Logging. A central tool registry (e.g., web fetch, PDF parsing, calculators) is used following freshness, verifiability, and latency rules. Agents record all tool provenance in an evidence ledger for traceable attribution.

- Parallel Gathering and Interim Synthesis. Worker agents operate concurrently while the orchestrator monitors coverage, resolves conflicts, and launches micro-delegations to close residual gaps or trigger deeper reasoning where needed.

- Final Report and Attribution. The orchestrator integrates verified findings into a coherent report, programmatically linking claims to sources and ensuring schema compliance, factual grounding, and transparent citation.

- Overall, Anthropic’s system exemplifies a scalable, interpretable multi-agent research paradigm that achieves high-quality synthesis through modular delegation, explicit budgeting, and verifiable reasoning.

4.2. Supervised Fine-Tuning

- Definition. Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) is a widely adopted approach that trains models to imitate desired behaviors using input–output pairs under a supervised learning objective. Within DR, SFT is commonly employed as the cold start, e.g., a warm-up process, before online reinforcement learning [45,46,59,148,392]. It aims to endow agents with basic task-solving skills [158,393].

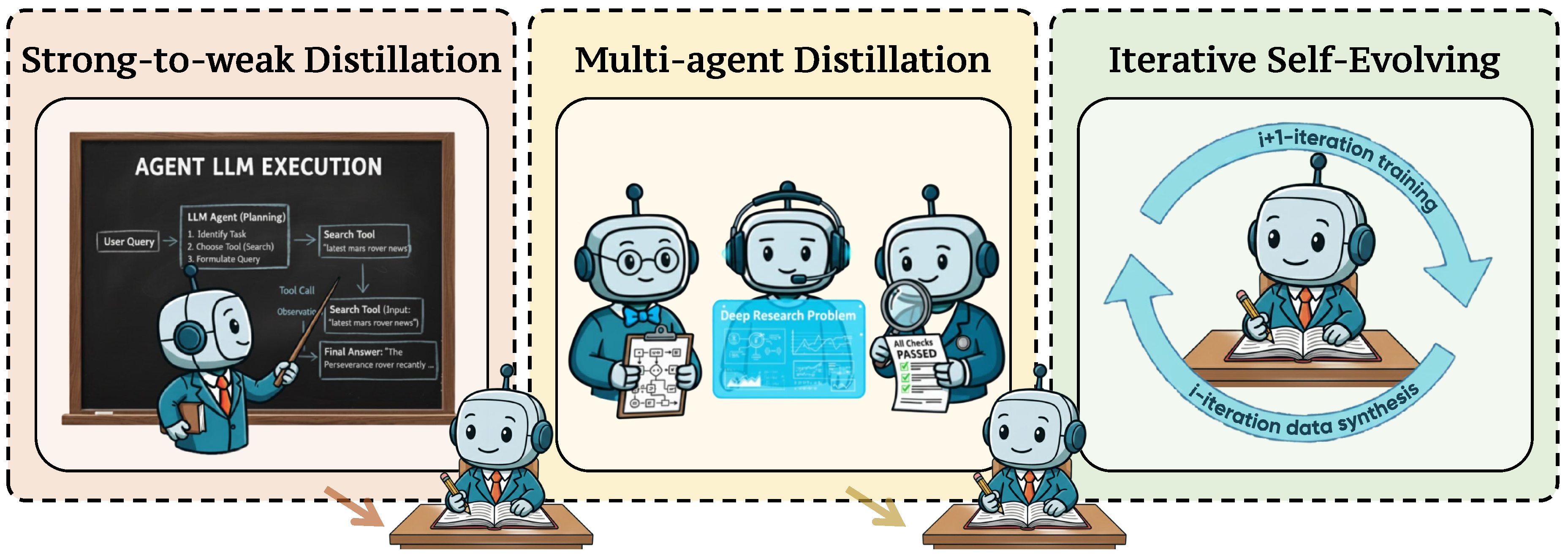

4.2.1. Strong-to-Weak Distillation

- Definition. Strong-to-weak distillation transfers high-quality decision trajectories from a powerful teacher system to smaller, weaker student models. Early work predominantly uses a single LLM-based agent to synthesize trajectories; more recent research employs multi-agent teacher systems to elicit more diverse, higher-complexity trajectories. We detail these two lines of work below.

- Single-agent distillation. Representative systems instantiate this pipeline in various ways. WebDancer [142] provides the agent with search and click tools. A strong non-reasoning model generates short CoT, while a large reasoning model (LRM) generates long CoT. The agent learns from both, using rejection sampling for quality control. WebSailor [143] uses an expert LRM to generate action-observation trajectories, then reconstructs short CoT with a non-reasoning model, ensuring the final reasoning chain is compact enough for long-horizon tasks. WebShaper [144] uses search and visit tools in a ReAct-style trajectory. It performs 5 rollouts per task and filters out repeated or speculative answers using a reviewing LLM. WebThinker [12] augments SFT with policy-gradient refinement and WebSynthesis [145] leverages a learned world model to simulate virtual web environments and employs MCTS to synthesize diverse, controllable web interaction trajectories entirely offline.

- Multi-agent distillation. Multi-agent distillation synthesizes training data using an agentic teacher system composed of specialized, collaborating agents (e.g., a planner, a tool caller, and a verifier), with the goal of transferring emergent problem-solving behaviors into a single end-to-end student model [147,398]. This paradigm tends to produce diverse trajectories, richer tool-use patterns, and explicit self-correction signals.

- Comparing Two Types of Distillation. Single-agent distillation provides a simple and easy-to-deploy pipeline, but it is limited by the bias of a single teacher model and the relatively shallow nature of its synthesized trajectories [400,401,402,403]. Such trajectories often emphasize token-level action sequences rather than higher-level reasoning, which can restrict the student model’s generalization ability in complex tasks. In contrast, multi-agent distillation generates longer and more diverse trajectories that expand the action space to include strategic planning, task decomposition, iterative error correction, and self-reflection [404,405]. This broader behavioral coverage equips student models with stronger capabilities for multi-step and knowledge-intensive reasoning [149].

4.2.2. Iterative Self-Evolving

- Definition. Iterative self-evolving data generation is an autonomous, cyclic process in which a model continuously generates new training data to fine-tune itself, progressively enhancing its capabilities [110,152,153,394].

- Representative Work. Early evidence that large language models can improve themselves comes from self-training methods [151,394,409], where a model bootstraps from a small set of seed tasks to synthesize instruction–input–output triples, filters the synthetic data, and then fine-tunes itself on the resulting corpus. These approaches deliver substantial gains in instruction following with minimal human supervision. Yuan et al. [151] further introduces self-rewarding language models, in which the model generates its own rewards through LLM-as-a-Judge prompting. More recently, Zhao et al. [152] extends this idea to the zero-data regime by framing self-play as an autonomous curriculum. The model creates code-style reasoning tasks, solves them, and relies on an external code executor as a verifiable environment to validate both tasks and solutions. In the context of DR, EvolveSearch [153] iteratively selects high-performing rollouts (i.e., task-solving trajectories) and re-optimizes the model on these data via supervised fine-tuning.

- Advantages & Disadvantages. A key advantage of iterative self-evolving frameworks is their closed-loop design, where the model progressively improves its capabilities by tightly interleaving data generation with training. This autonomy enables scalable training without heavy reliance on external models or human annotations, and it allows exploration of data distributions that extend beyond handcrafted knowledge [151,394,410,411,412].

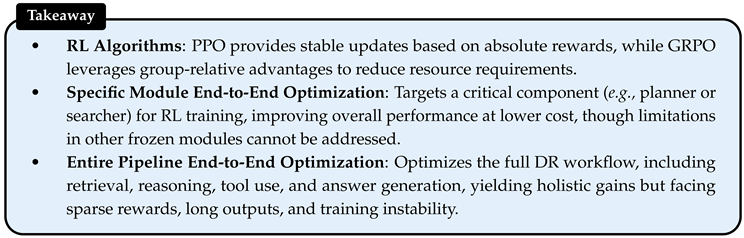

4.3. End-to-End Agentic Reinforcement Learning

- Definition. In this section, we dive into the application of end-to-end agentic reinforcement learning (RL) in DR, i.e., using RL algorithms to incentivize DR agents that can flexibly plan, act, and generate a final answer. We start with a brief overview, including commonly used RL algorithms and reward design for optimizing DR systems. For a clear explanation, we provide a glossary table in Table 3 to formally introduce the key variable in this Section 4.3. Then we discuss two training practices: (i) specific module optimization and (ii) entire pipeline optimization.

| Symbol | Definition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Current policy | Parameterized LLM policy that generates actions (tokens or sequences) conditioned on a given state. | |

| Reference (old) policy | A frozen snapshot of the policy before the current update, used for computing probability ratios and ensuring stable optimization. | |

| q | Input query | Input question or prompt to the agent. |

| o | Model output | Final answer produced by the policy model. |

| Action at step t | The token generated by the policy model conditioned on state . | |

| State at step t | Context of the policy model at time step t. | |

| Reward function | Scalar score assigned to output o for the input query q. | |

| Probability ratio | Ratio between current and reference policy probabilities, computed as . | |

| Clipping threshold | Stability constant that limits update magnitude in PPO or adds numerical robustness in GRPO. | |

| Response group | A collection of multiple sampled responses corresponding to the same query in GRPO. | |

| m | Group size | The number of candidate responses in a response group . |

| j-th response in group | The j-th sampled output candidate among the m responses in group . |

4.3.1. Preliminary

- RL algorithms in Deep Research. In DR, LLMs are trained to act as autonomous agents that generate comprehensive reports through complex query decomposition, multi-step reasoning, and extensive tool use. The primary RL algorithms used to train these agents include Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) from OpenAI [259,420], Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) from DeepSeek [332,421], and their variants [422].

- Proximal Policy Optimization. PPO [259] is a clipped policy-gradient method that constrains updates within a trust region [423]. Given a current policy and a old policy , the objective is to maximize the clipped surrogate:where bounds the policy update and is the estimated advantage. The advantage is computed using discounted returns or generalized advantage estimation (GAE) [424] as:Here denotes the immediate reward at time step , is the discount factor balancing the importance of long-term and short-term returns; T is the terminal time step of the current trajectory (episode); is the next state used for bootstrapping after termination, is the value function predicted by the value network parameterized by . We define the empirical return purely from rewards as:which represents the cumulative discounted rewards from time step t until the end of the episode. In PPO, the value function parameters are updated by minimizing the squared error between the predicted value and the empirical return:

- Group Relative Policy Optimization. Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) [332] extends PPO by normalizing rewards within groups of responses to the same query. Formally, given a group of m responses sampled for the same query , each response is assigned a scalar reward . The group-relative advantage for the j-th response is:where and denote the mean and standard deviation of rewards within group , and prevents numerical instability when the variance is small. The GRPO objective mirrors PPO’s clipping mechanism but replaces with the group-relative advantage :

- Comparison between PPO and GRPO in Deep Research. In PPO, each sampled output is optimized using an advantage signal derived from a value model. While this approach is effective, its performance is highly reliant on accurate value estimation and requires additional resources for training the value model. In contrast, GRPO optimizes by contrasting each response against others within the same group. This shifts the focus to a relative-quality comparison among competing hypotheses, simplifying implementation while maintaining strong performance.

-

Reward Design in Deep Research Agents. During the RL training of DR agents, the reward model, denoted as , assesses the quality (e.g., correctness) of the agents’ outputs and produces scalar signals to enable policy optimization algorithms such as PPO and GRPO. Reward design takes a critical role in training LLM. There are two common reward design paradigms in DR systems, i.e., rule-based rewards and LLM-as-judge rewards.

- Rule-based Rewards . Rule-based rewards are derived from deterministic, task-specific metrics such as Exact Match (EM) and F1 score [425]. In the context of research agents, EM is a commonly used binary score that indicates whether a generated answer perfectly matches a ground-truth string [45,69,273]. Alternatively, the F1 score (i.e., the harmonic mean of precision and recall calculated over token overlap) is also used to reward outputs [37,53]. However, a key limitation of rule-based rewards is that they are primarily suited for tasks with well-defined, short-span ground truths (e.g., a specific entity name) and struggle to evaluate multi-answer or open-ended questions effectively.

- LLM-as-judge Rewards . The LLM-as-judge approach uses an external LLM to evaluate the quality of an agent’s output and assign a scalar score based on a predefined rubric [426]. Formally, for an output o to an input query q, the reward assigned by an LLM judge can be formulated as:where is the set of evaluation criteria (e.g., accuracy, completeness, citation quality, clarity, etc) and returns a scalar score for each criterion.

4.3.2. End-to-end Optimization of a Specific Module

- Definition. End-to-end optimization of a specific module focuses on applying RL techniques to improve individual components within a DR system, such as the query planning, document ranking, or planning modules.

- Representative work. Within DR, most existing work trains the query planner [43,427,428,429] while freezing the parameters, leaving components such as retrieval. MAO-ARAG [53] treats DR as a multi-turn process where a planning agent orchestrates sub-agents for information seeking. PPO propagates a holistic reward (e.g., final F1 minus token and latency penalties) across all steps, enabling end-to-end learning of the trade-offs between answer quality and computational cost. AI-SearchPlanner [44] decouples a lightweight search planner from a frozen QA generator. PPO optimizes the planner with dual rewards: an outcome reward for improving answer quality and a process reward for reasoning rationality. A Pareto-regularized objective balances utility with real-world cost, guiding the planner on when to query or stop.

- Advantages & Disadvantages. Single-module optimization usually focuses on training a single core component (e.g., the planning module) while keeping the others fixed. Optimizing this critical module can improve the performance of a DR system by enabling more accurate credit assignment, more sophisticated algorithm design for the target module, and reduced training data and computational costs. However, this approach restricts the optimization space and may be inadequate when other frozen modules contain significant design or performance flaws.

4.3.3. End-to-end Optimization of an Entire Pipeline

- Definition. End-to-end pipeline optimization involves jointly optimizing all components and processes from input to output (e.g., query decomposition, search, reading, and report generation) to achieve the best overall performance across the DR workflow.

- Representative work on Multi-Hop Search. Some work focuses on enhancing the capability of multi-hop search by training the entire DR systems end-to-end [17,46,47,154,430]. For example, Jin et al. [45], Jin et al. [273] present Search-R1, the first work to formulate search-augmented reasoning as a fully observable Markov Decision Process and to optimize the entire pipeline via RL, containing query planning, retrieval, and extracting the final answer. By masking retrieved tokens in the policy-gradient loss, the model learns to autonomously decide when and what to search while keeping the training signal on its own generated tokens. Meanwhile, Song et al. [46] introduces R1-Searcher, a two-stage RL method in which the DR agent learns when to invoke external searches and how to use retrieved knowledge via outcome rewards. However, it has been observed that pure RL training often leads to over-reliance on external retrieval, resulting in over-searching [47]. To mitigate this issue, R1-Searcher++ [47] first cold-starts the DR agent via an SFT, then applies a knowledge-assimilation RL process to encourage the agent to internalize previously retrieved documents and avoid redundant retrievals.

- Representative work on Long-Chain Web Search. Besides the relatively simple multi-hop QA tasks, more recent work also applies end-to-end pipeline optimization to address longer-chain web search problems. Prior works, such as WebDancer [142], WebSailor [143], and Kimi-K2 [155], have focused on advancing more intricate multi-hop tasks, including GAIA [178] and BrowseComp [184]. These approaches combine data synthesis with end-to-end reinforcement learning training, thereby enabling more extensive iterations in the DR process.

- Advantages & Disadvantages. These end-to-end methods model the entire DR system as a multi-turn search process, achieving comprehensive optimization across reasoning, query rewriting, knowledge retrieval, tool invocation, and answer generation. This modeling and optimization approach is not only flexible but also allows for different objectives to be emphasized through the design of reward functions. However, these methods also have drawbacks, including sparse rewards, excessively long responses, and unstable training. Continuous optimization is needed to further enhance the effectiveness, stability, and efficiency of DR systems.

5. Evaluation of Deep Research System

5.1. Agentic Information Seeking

| Benchmark (with link) | Date | Aspect | Data size (train/dev/test) | Evaluation metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NQ | 2019 | QA | 307373/7830/7842 | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| SimpleQA | 2024 | QA | 4,326 | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| HotpotQA | 2019 | QA | 90124 / 5617 / 5813 | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| 2WikiMultihopQA | 2020 | QA | 167454/12576/12576 | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| Bamboogle | 2023 | QA | 8600 | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| MultiHop-RAG | 2024 | QA | 2556 | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| MuSiQue | 2022 | QA | 25K | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| GPQA | 2023 | QA | 448 | Accuracy |

| GAIA | 2023 | QA | 450 | Exact Match |

| BrowseComp | 2025 | QA | 1266 | Exact Match |

| BrowseComp-Plus | 2025 | QA | 830 | Accuracy / Recall / Search Call / Calibration Error |

| HLE | 2025 | QA | 2500 | Exact Match / Accuracy |

5.1.1. Complex Queries

| Benchmark (with link) | Date | Aspect | Data size (train/dev/test) | Evaluation metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRAMES | 2024 | QA | 824 | Exact Match / F1 / Accuracy |

| InfoDeepSeek | 2025 | QA | 245 | Accuracy / Utilization / Compactness |

| AssistantBench | 2025 | QA | 214 | F1 / Similarity |

| Mind2Web | 2025 | QA | 2350 | Accuracy / F1 / Step Success Rate |

| Mind2Web 2 | 2025 | QA | 130 | Agent-as-a-Judge |

| Deep Research Bench | 2025 | QA | 89 | Precision / Recall / F1 |

| DeepResearchGym | 2025 | QA | 96,000 | Report Relevance / Retrieval Faithfulness / Report Quality |

| WebArena | 2024 | Complex Task | 812 | Correctness |

| WebWalkerQA | 2025 | QA | 680 | Accuracy / Action Count |

| WideSearch | 2025 | QA | 200 | LLM Judge |

| MMInA | 2025 | Complex Task | 1050 | Success Rate |

| AutoSurvey | 2024 | Survey Generation | 530,000 | Citation Quality / Content Quality |

| ReportBench | 2025 | Survey Generation | 600 | Content Quality / Cited Statement / Non-Cited Statements |

| SurveyGen | 2025 | Survey Generation | 4200 | Topical Relevance / Academic Impact / Content Diversity |

| Deep Research Comparator | 2025 | Report Generation | 176 | BradleyTerry Score |

| DeepResearch Bench | 2025 | Report Generation | 100 | LLM Judge |

| ResearcherBench | 2025 | Report Generation | 65 | Rubric Assessment / Factual Assessment |

| LiveDRBench | 2025 | Report Generation | 100 | Precision / Recall / F1 |

| PROXYQA | 2025 | Report Generation | 100 | LLM Judge |

| SCHOLARQABENCH | 2025 | Report Generation | 2967 | Accuracy / Citations / Rubrics |

| Paper2Poster | 2025 | Poster Generation | 100 | Visual Quality / Textual Coherence / VLM Judge |

| PosterGen | 2025 | Poster Generation | 10 | Poster Content / Poster Design |

| P2PInstruct | 2025 | Poster Generation | 121 | LLM Judge |

| Doc2PPT | 2022 | Slides Generation | 6000 | ROUGE / Figure Subsequence / Text-Figure Relevance |

| SLIDESBENCH | 2025 | Slides Generation | 7000/0/585 | Text / Image / Layout / Color / LLM Judge |

| Zenodo10K | 2025 | Slides Generation | 10,448 | Content / Design / Coherence |

| TSBench | 2025 | Slides Generation | 379 | Editing Success / Efficiency |

| AI Idea Bench | 2025 | Idea Generation | 0/0/3495 | LLM Judge |

| Scientist-Bench | 2025 | Idea Generation, Experimental Execution | 0/0/52 | LLM Judge, Human Judge |

| PaperBench | 2025 | Experimental Execution | 0/0/20 | LLM Judge |

| ASAP-Review | 2021 | Peer Review | 0/0/8877 | Human / ROUGE / BERTScore |

| DeepReview | 2025 | Peer Review | 13378/0/1286 | LLM Judge |

| SWE-Bench | 2023 | Software Engineering | 0/0/500 | Environment |

| ScienceWorld | 2022 | Scientific Discovery | 3600/1800/1800 | Environment |

| GPT-Simulator | 2024 | Scientific Discovery | 0/0/76369 | LLM Judge |

| DiscoveryWorld | 2024 | Scientific Discovery | 0/0/120 | LLM Judge |

| CORE-Bench | 2024 | Scientific Discovery | 0/0/270 | Environment |

| MLE | 2024 | Machine Learning Engineering | 0/0/75 | Environment |

| RE-Bench | 2024 | Machine Learning Engineering | 0/0/7 | Environment |

| DSBench | 2024 | Data Science | 0/0/540 | Environment |

| Spider2-V | 2024 | Data Science | 0/0/494 | Environment |

| DSEval | 2024 | Data Science | 0/0/513 | LLM Judge |

| UnivEARTH | 2025 | Earth Observation | 0/0/140 | Exact Match |

| Commit0 | 2024 | Software Engineering | 0/0/54 | Unit test |

5.1.2. Interaction Environment

5.2. Comprehensive Report Generation

5.2.1. Survey Generation

5.2.2. Long-Form Report Generation

5.2.3. Poster Generation

5.2.4. Slides Generation

5.3. AI for Research

5.3.1. Idea Generation

5.3.2. Experimental Execution

5.3.3. Academic Writing

5.3.4. Peer Review

5.4. Software Engineering

6. Challenges and Outlook

6.1. Retrieval Timing

6.2. Memory Evolution

6.2.1. Proactive Personalization Memory Evolution

6.2.2. Cognitive-Inspired Structured Memory Evolution

6.2.3. Goal-Driven Reinforced Memory Evolution

6.3. Instability in Training Algorithms

6.3.1. Existing Solutions

- Filtering void turns. The first representative solution is proposed by Xue et al. [470], who identify void turns as a major cause of collapse in multi-turn RL. Void turns refer to responses that do not advance the task, such as fragmented text, repetitive content, or premature termination; and once produced, they propagate through later turns, creating a harmful feedback loop. These errors largely stem from the distribution shift between pre-training and multi-turn inference, where the model must process external tool outputs or intermediate signals that were not present during pre-training, increasing the chance of malformed generations. To address this, SimpleTIR [470] filters out trajectories containing void turns, effectively removing corrupted supervision and stabilizing multi-turn RL training.

- Mitigating the Echo Trap. Wang et al. [471] identify the Echo Trap as a central cause of collapse in multi-turn RL. The Echo Trap refers to rapid policy homogenization, where the model abandons exploration and repeatedly produces conservative outputs that yield short-term rewards. Once this happens, reward variance and policy entropy drop sharply, forming a self-reinforcing degenerative loop. The root cause is a misalignment between reward-driven optimization and reasoning quality. In multi-turn settings, sparse binary rewards cannot distinguish coincidental success from genuine high-quality reasoning, encouraging reward hacking behaviors such as hallucinated reasoning or skipping essential steps. To address this, the proposed StarPO-S [471] uses uncertainty-based trajectory filtering to retain trajectories exhibiting meaningful exploration. This breaks the Echo Trap cycle and stabilizes multi-turn RL training.

6.3.2. Future Directions

- Cold-start methods that preserve exploration. SFT is a practical cold-start strategy for multi-turn RL, yet it introduces a significant drawback: it rapidly reduces output entropy, constraining the model’s ability to explore and develop new reasoning strategies [473]. A promising research direction is to design cold-start methods that improve initial task performance while maintaining exploratory behavior. Such techniques should aim to avoid early entropy collapse and preserve the model’s capacity for innovation in multi-turn reasoning.

- Denser and smoother reward design. Although StarPO-S [471] effectively mitigates training collapse in PPO-based multi-turn RL, its benefit is more limited for GRPO. The critic module inherent to PPO algorithm [259] naturally smooths reward signals, while GRPO relies on group-wise normalization, which makes it more sensitive to reward variance and extreme values. Developing denser, smoother, and more informative reward functions for multi-turn scenarios, especially for GRPO-style algorithms, remains an important direction for future research.

6.4. Evaluation of Deep Research System

6.4.1. Logical Evaluation

6.4.2. Boundary between Novelty and Hallucination

6.4.3. Bias and Efficiency of LLM-as-Judge

- Mitigating bias. Bias can be reduced by incorporating human evaluators for critical or ambiguous cases, providing a grounded reference for calibration [433]. Another direction is to fine-tune judge models using datasets that highlight diverse reasoning styles and explicit debiasing signals [494]. Such training may lessen systematic preferences for particular formats or linguistic patterns.

- Improving efficiency. Efficiency can be improved by adopting open-source, general-purpose judge models, which reduce evaluation cost while offering greater transparency and reproducibility [495]. Further improvements may come from smarter candidate selection algorithms that focus on the most informative comparisons [496]. By lowering the number of required pairwise evaluations without sacrificing quality, such methods enable LLM-based evaluation in more resource-constrained settings.

7. Open Discussion: Deep Research to General Intelligence

7.1. Creativity

7.2. Fairness

7.3. Safety and Reliability

8. Conclusions and Future Outlook

References

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A comprehensive overview of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]