Introduction

Uterine fibroids (UFs) are benign monoclonal neoplasms originating from the myometrium and represent the most prevalent tumors in women worldwide. [

1] The clinical manifestations of UFs commonly include abnormal uterine bleeding leading to anemia, fatigue, chronic vaginal discharge, and dysmenorrhea. Also referred to as leiomyomas, UFs are among the most common benign neoplasms in women. Reported incidence rates vary widely, ranging from 5.4% to 77%, depending on the studied population. [

2,

3] Treatment options for UFs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, vitamin D3 and iron supplementation, combined oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs, and surgical excision. [

4,

5]

Female sex hormones play a crucial role in fibroid growth and proliferation. This hormonal dependency allows the use of hormone therapy to reduce fibroid size. Hormone-based treatments may be utilized to alleviate symptoms or facilitate preoperative preparation. GnRH agonists inhibit fibroid growth, thereby reducing menstrual bleeding and pain. In cases of menorrhagia-induced anemia, this treatment can also improve hematologic parameters. However, not all patients respond favorably to these hormonal agents; approximately half report minimal or no symptomatic improvement. The suitability of GnRH agonists depends on fibroid type and the planned surgical approach. Several studies have demonstrated their efficacy as preoperative agents prior to UF surgery.[

6] Furthermore, GnRH antagonists have recently emerged as promising alternatives for UF management. These agents rapidly bind to GnRH receptors, block endogenous GnRH activity, and directly suppress LH and FSH secretion, thereby avoiding the initial flare-up effect. [

7]

Clinical management of UFs may vary among specialists depending on existing guidelines, patient symptoms, and clinical findings. With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) and clinical decision support systems, these decision-making processes can now be modeled algorithmically, enabling the translation of clinical experience into computational systems.[

8] Such systems can assist less-experienced clinicians in making informed and consistent surgical decisions. A critical objective is to develop algorithms that achieve high predictive accuracy. Moreover, designing AI algorithms that operate with minimal input parameters enhances their practicality for routine clinical use.

Vetrivel et al.[

9] developed a machine learning–based decision support tool for UF treatment. Using data sourced from Kaggle, the authors trained multiple machine learning (ML) models to predict both treatment decisions and timing. The highest model accuracy achieved was 78%.

The present study aims to develop a machine learning–based clinical decision support algorithm to guide surgical decision-making for UFs using fibroid characteristics and female sex hormone parameters.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval was granted by the Istinye University Ethics Committee (approval date: June 30, 2025; decision number: 24-18). All study procedures adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

A total of 618 patients diagnosed with UFs who presented to the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Private Derindere Hospital, Ataköy Medicana Hospital, and Kızılay Kağıthane Hospital (Turkey) were included in the study. Of these, 238 patients underwent surgical intervention. Analyses were planned and conducted by stratifying patients into surgical and non-surgical groups.

Study Design

This study is a national, multicenter, retrospective analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between surgical and non-surgical groups across all input parameters. ML training was initially performed for each female sex hormone—follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estrogen (E2), prolactin (PRL), and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)—independently of UF characteristics. Subsequently, 126 unique input combinations were generated by integrating hormone parameters with UF characteristics, and ML models were trained accordingly. In addition to this retrospective development phase, the model underwent a prospective validation process, during which independent clinical cases were evaluated in real time by a gynecologist blinded to model predictions.

Validation Procedure

To evaluate the external decision-support performance of the developed AI model, an independent validation exercise was conducted using 20 anonymized clinical cases that were not included in the training dataset. These cases were presented to an experienced gynecologist who was blinded to both the model predictions and the surgical outcomes. The clinician was asked to assess each case solely based on the available clinical and hormonal parameters and to determine whether myomectomy was indicated.

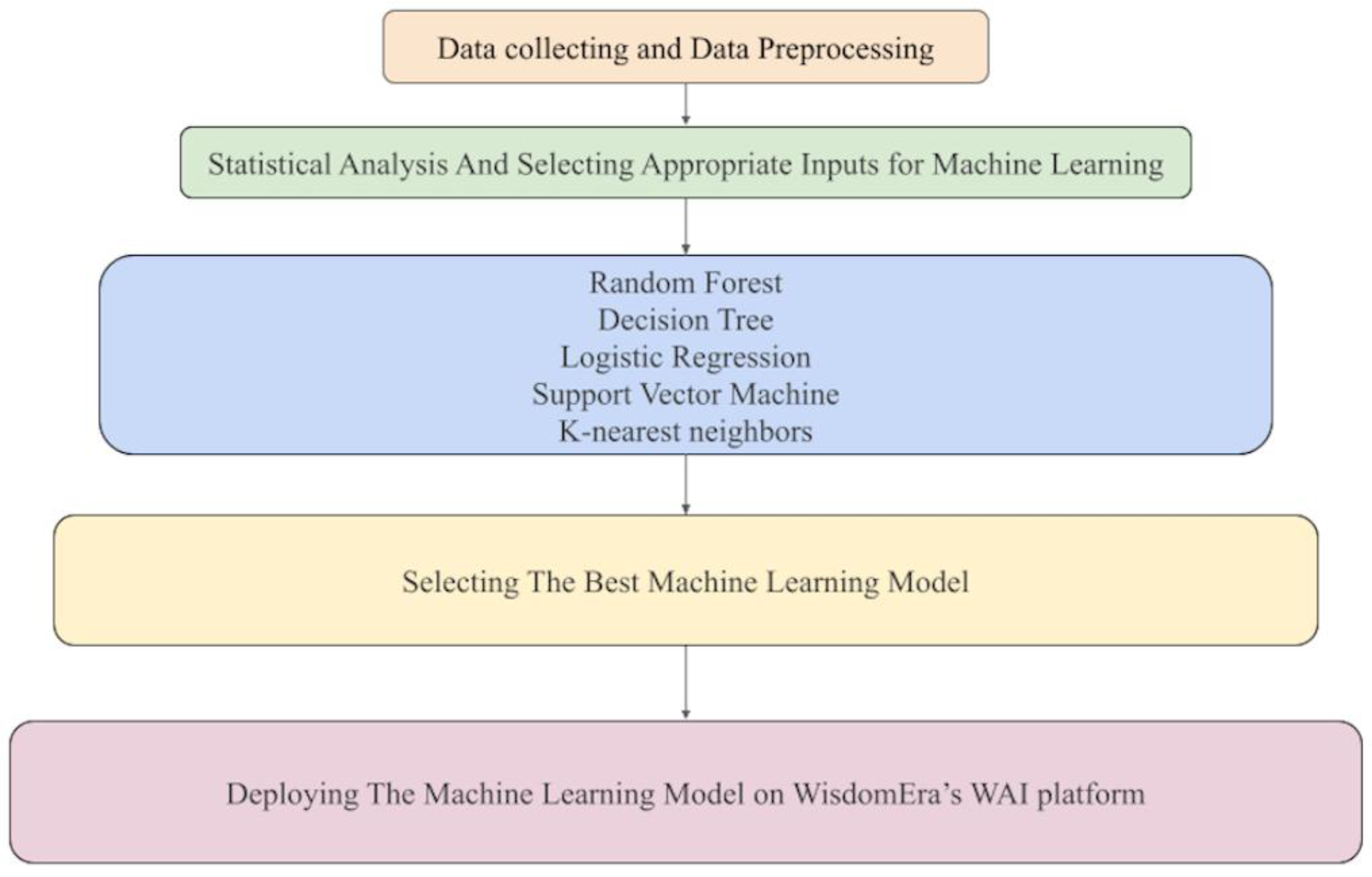

Machine Learning Procedure and Pipeline

Statistical analyses were conducted prior to ML modeling. Surgical application status was defined as the primary outcome, and predictive algorithms were developed using five classification models: support vector machine (SVM), decision tree (DT), random forest (RF), logistic regression (LR), and k-nearest neighbors (KNN). A 70:30 train–test split was applied for model evaluation, and model performance was evaluated using area under the curve (AUC), accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1 score (

Figure 1).

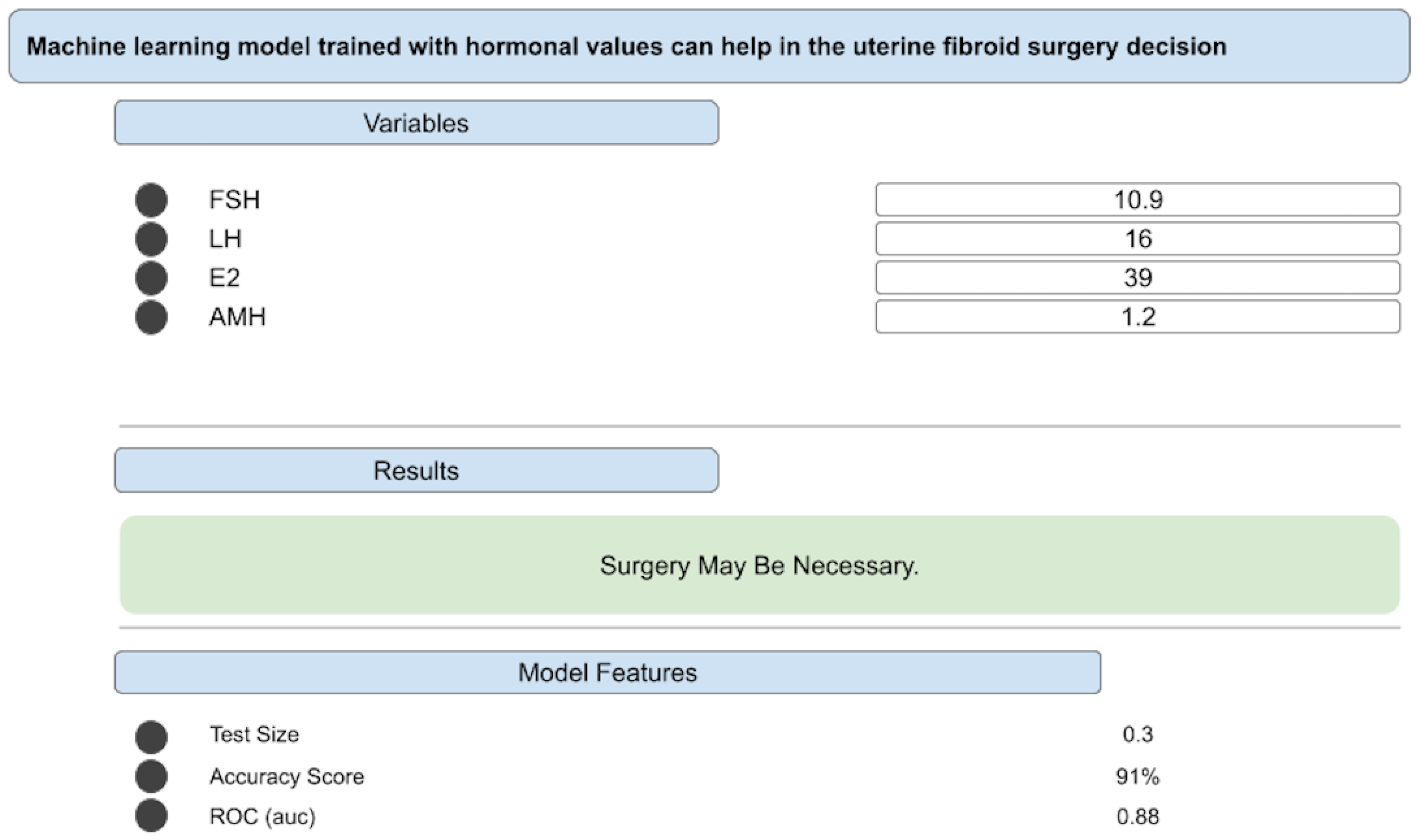

Deploying The Best Decision Support Algorithm on “JinekoAI.com” Web Application

Among the developed algorithms, it was determined that the machine learning model with the highest performance could be used in clinical settings. Consequently, the algorithm was implemented on the WisdomEra Artificial Intelligence (WAI) data analytics platform, hosted on cloud infrastructure.[

10] In this application, we introduce several decision support algorithms that have been developed, which will be linked to our corresponding publications. Additionally, the algorithms can generate outputs related to the necessity of surgical intervention based on input parameters (

Figure 2). This system allows for the integration of the algorithms into decision support services. In doing so, we can transform these decision support algorithms into tangible products for use by both specialists and patients.[

11]

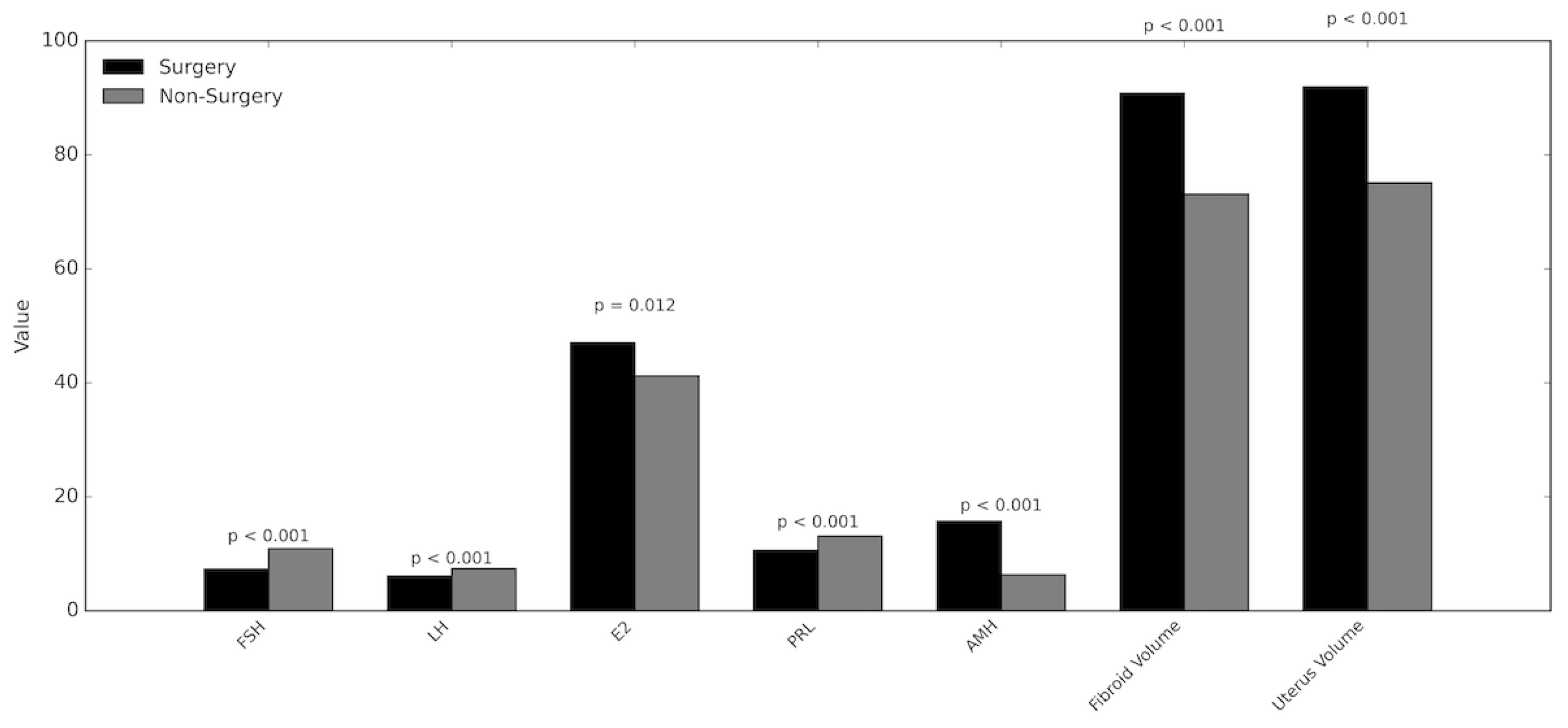

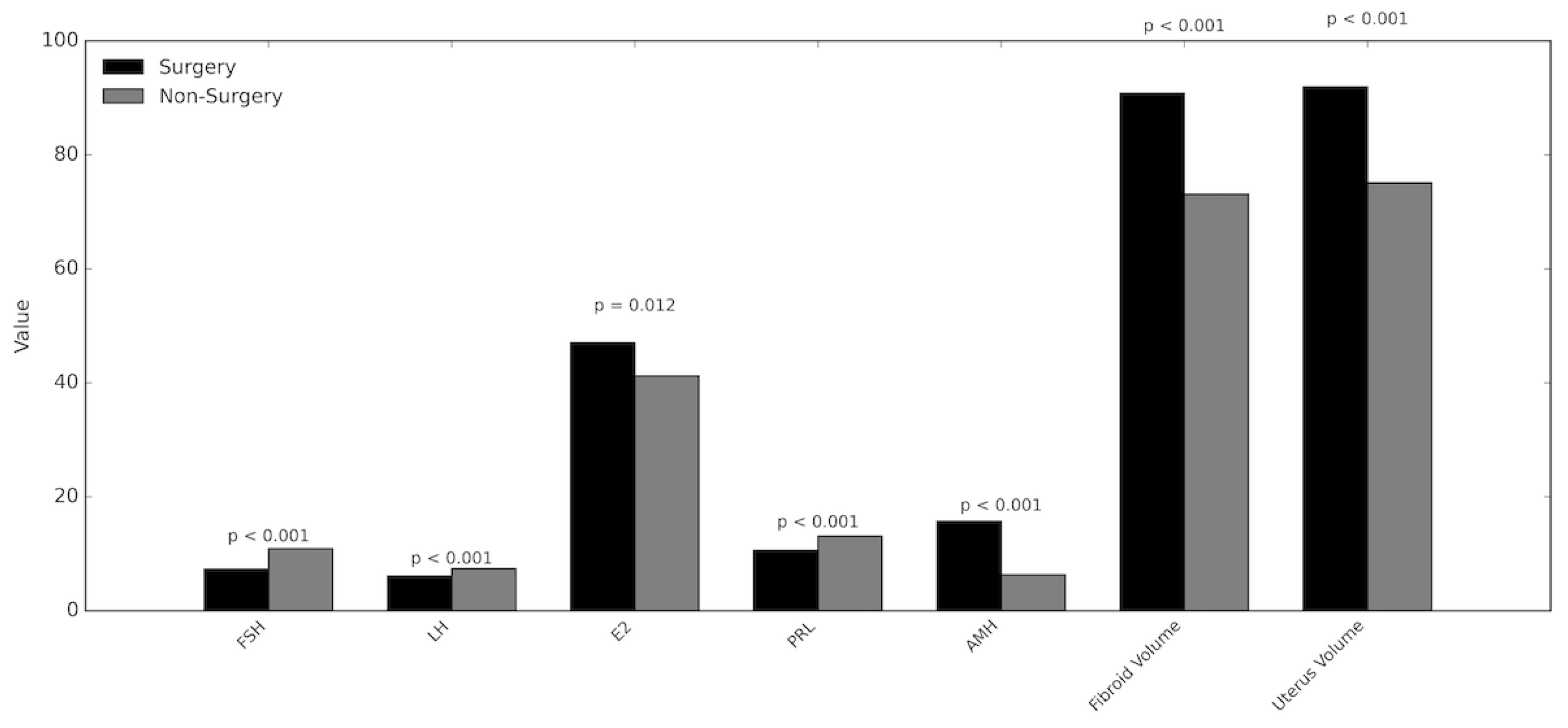

Figure 3.

Comparison of Hormonal and Morphological Parameters Between Surgical and Non-Surgical Groups. This figure presents a grouped bar chart illustrating mean values of key hormonal markers—follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estrogen, prolactin, and anti-Müllerian hormone—together with fibroid and uterine volumes in women who underwent surgical intervention versus those managed conservatively. For each parameter, black bars represent the surgical group and gray bars represent the non-surgical group. Corresponding p-values above each pair of bars indicate the statistical significance of between-group differences. The chart demonstrates that the surgical cohort exhibited significantly lower follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and prolactin levels, and significantly higher estrogen and anti-Müllerian hormone levels, as well as larger fibroid and uterine volumes. These trends reflect the combined hormonal and structural features associated with surgical indication in uterine fibroid management.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Hormonal and Morphological Parameters Between Surgical and Non-Surgical Groups. This figure presents a grouped bar chart illustrating mean values of key hormonal markers—follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estrogen, prolactin, and anti-Müllerian hormone—together with fibroid and uterine volumes in women who underwent surgical intervention versus those managed conservatively. For each parameter, black bars represent the surgical group and gray bars represent the non-surgical group. Corresponding p-values above each pair of bars indicate the statistical significance of between-group differences. The chart demonstrates that the surgical cohort exhibited significantly lower follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and prolactin levels, and significantly higher estrogen and anti-Müllerian hormone levels, as well as larger fibroid and uterine volumes. These trends reflect the combined hormonal and structural features associated with surgical indication in uterine fibroid management.

Results

Statistical Results

The detailed descriptive and comparative statistics are summarized in

Table 1. There was no statistically significant age difference between the surgical and non-surgical groups (p = 0.613; mean age: 35.7 vs. 35.4 years). Similarly, the duration of disease (1–5 years vs. > 5 years) showed no statistically significant variation between the two groups (p = 0.361; proportion of patients with disease > 5 years—surgical: 47%, non-surgical: 43%). In contrast, serum levels of FSH, LH, and PRL were significantly lower in the surgical group than in the non-surgical group (p < 0.001, 0.009, and < 0.001, respectively). Conversely, E2 and AMH concentrations were significantly higher in the surgical group (p = 0.012 and 0.001, respectively). Comparative analysis of UF characteristics revealed that the mean UF volume was markedly greater in the surgical group (p < 0.001; surgical: 90.8 cc, non-surgical: 73.1 cc). However, the number of UFs did not differ significantly between groups (p = 0.384; surgical: 4.7, non-surgical: 4.6).

Machine Learning Model Training Results

ML models were trained and evaluated to predict surgical necessity by generating 126 input combinations derived from hormonal parameters and UF characteristics. Five different ML algorithms were applied to each input combination, resulting in a total of 630 independent model training sessions. Among these, 12 models achieved an accuracy exceeding 85% and are presented in

Table 2. All trained models were categorized according to their accuracy ranges (>90%, 80–90%, 70–80%, 60–70%, 50–60%, and <50%). The distribution of models across these accuracy groups is displayed in

Table 3.

In multivariable analyses, the most efficient ML model was identified among those utilizing hormonal parameters. Specifically, the RF model trained on LH, FSH, E2, and AMH demonstrated the highest predictive performance, achieving an accuracy of 91%. The test dataset constituted 30% of the total sample. Additional performance metrics were as follows: area under the curve (AUC) = 0.88, Precision = 0.91, Recall = 0.91, and F1-score = 0.91.[

12]

When UF volume—a parameter found to differ significantly between surgical and non-surgical groups—was incorporated alongside LH, FSH, E2, and AMH, the resulting model achieved an accuracy of 85%. Using the same 30% test set, its performance metrics were recorded as: AUC = 0.82, Precision = 0.85, Recall = 0.85, and F1-score = 0.85.

External Validation Results

Concordance was observed in 18 of the 20 cases, corresponding to a 90% agreement rate. The two discordant cases were subsequently reviewed and determined to represent borderline clinical scenarios in which surgical decision-making is inherently ambiguous. This high level of agreement supports the model’s robustness and demonstrates its potential to align closely with expert clinical judgment in real-world decision-making contexts.

Discussion

UFs substantially affect women’s health and quality of life, primarily through abnormal or heavy menstrual bleeding and iron deficiency anemia.[

13] Making timely and appropriate surgical decisions is therefore critical for optimizing patient outcomes. However, determining the optimal timing of surgery often poses a clinical challenge. The management of UFs should be individualized based on symptom severity and the patient’s reproductive preferences or the desire for definitive treatment.[

5] Given the well-established role of female sex hormones in UF pathophysiology [

14], our findings demonstrate that hormonal parameters can effectively contribute to clinical decision-support algorithms for predicting surgical necessity. Notably, the RF model incorporating LH, FSH, E2, and AMH achieved the highest predictive accuracy (91%). Furthermore, the UF volume was significantly higher in the surgical group compared with the non-surgical group (p < 0.001). Importantly, these model-derived predictions demonstrated strong real-world concordance: in an external validation exercise, the AI model and a blinded gynecologist reached identical surgical decisions in 18 of 20 independent cases, yielding a 90% agreement rate. This level of clinical alignment underscores the model’s capacity to reflect expert decision-making in practice.

Symptomatic anemia associated with UF progression often influences surgical decision-making. Our results suggest that abnormalities in female sex hormones—particularly decreased FSH and LH levels alongside elevated E2 and AMH—can serve as early predictors of surgical need, even before anemia develops. Increasing UF volume further supports the indication for surgical intervention, particularly in patients with borderline low hemoglobin values.

Previous studies have highlighted the hormonal influence on UF growth. Estrogen, LH, and FSH play key regulatory roles in fibroid development [

15], and elevated estrogen levels have been linked to accelerated UF growth.[

16] Li et al. developed regression-based predictive models identifying FSH, LH, age, and lipid markers as significant predictors of UF growth.[

14] In line with these findings, our models utilizing FSH and LH as input features achieved high predictive accuracy (

Table 2). We propose that these hormonal parameters can be effectively integrated into ML-based models to estimate surgical necessity in UF patients.

The increasing integration of AI into clinical medicine provides novel opportunities to address diagnostic complexity, personalize treatment planning, and enhance patient outcomes. However, AI-driven decision-support systems remain underutilized in gynecologic practice.[

17]

Recent studies have demonstrated promising applications of AI in UF diagnosis and treatment. Hue et al. developed an AI-assisted ultrasonography tool that significantly improved diagnostic accuracy among junior ultrasonographers (94.72% vs. 86.63%) compared with senior experts.[

18] In our study, we similarly incorporated clinical expertise into AI-based algorithms trained on structured hormonal and UF data. Such models could assist less experienced clinicians in making more informed and timely surgical decisions.

Moreover, other AI applications have shown diagnostic performance comparable to that of human experts in differentiating benign from malignant lesions.[

19] Chen et al. reported that AI tools enhanced the precision of hysteroscopic myomectomy by improving spatial localization of submucosal myomas.[

20]

A recent review by Micić and colleagues summarized current UF management strategies, emphasizing that treatment should begin with medical or minimally invasive approaches before considering surgical intervention. Nonetheless, surgery remains the most common modality. The review also stressed that UF treatment decisions must balance risks and benefits while reflecting patients’ medical profiles and preferences.[

5] Consistent with this perspective, our proposed clinical decision-support algorithms offer a systematic, data-driven approach to guide individualized treatment selection.

Surgical intervention is often necessitated by UF-related complications. The AI-based decision-support algorithms developed in this study provide a highly accurate framework for predicting surgical necessity based on hormonal and UF characteristics. These models may enhance decision-making efficiency, reduce inter-clinician variability, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

This study has several limitations. Postoperative hormone levels were unavailable, preventing analysis of hormonal dynamics after surgery. Additionally, data on preoperative pharmacological or interventional treatments were not included, as these variables were absent from our database. Despite these limitations, the developed algorithms demonstrated robust performance and clinical applicability.

To our knowledge, no prior study has developed an ML-based clinical decision-support algorithm that integrates female sex hormone parameters with UF characteristics to predict surgical necessity. Therefore, this research represents the first such approach reported in the literature and provides a foundation for future AI-driven decision-support systems in gynecology.

Conclusions

In conclusion, determining the appropriate timing for UF surgery remains a global clinical challenge. The AI-based clinical decision-support algorithms developed in this study can effectively assist in making timely and evidence-based surgical decisions. The high external validation concordance—90% agreement between the model and a blinded gynecologist—demonstrates that the system not only performs well statistically but also aligns closely with real clinical judgment. Our findings underscore the potential of AI to augment clinical expertise, reduce subjective variability, and optimize management strategies for patients with UFs. Further work is underway to refine and expand these AI models for broader surgical decision-making contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: İnci OZ and Engin Ulukaya; Methodology: İnci OZ and Engin Ulukaya; Investigation: İnci OZ, Ali Utku OZ, and Ecem E. YEGIN; Resources: İnci OZ and Ali Utku OZ; Data Curation: İnci OZ; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: İnci OZ, Ali Utku OZ, and Ecem E. YEGIN; Writing – Review & Editing: İnci OZ and Ecem E. YEGIN; Supervision: İnci OZ and Engin Ulukaya.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Istinye University (protocol code 24-18 and January 30, 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the study was designed as a retrospective analysis of anonymized medical records, involved no direct patient contact or intervention, and posed no foreseeable risk to participants. The Institutional Review Board approved the waiver of informed consent in accordance with national regulations and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed in this study is publicly available on the Istinye University Dataset Sharing Platform. Anonymized clinical and hormonal data related to uterine fibroids can be accessed at the following link:

https://dataset.istinye.edu.tr/dataset?did=55. All data were fully anonymized in accordance with ethical regulations. Access is provided for research purposes through a controlled-access system under the platform’s standard licensing and data-sharing policies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Artificial Intelligence Research And Application Center of Istinye University (

https://yzaum.istinye.edu.tr/) for their support in the technical assessment of the manuscript, including verification of data integrity and plagiarism screening prior to submission. We also extend our appreciation to the Ditako Data Analytics Team (

https://ditako.com) for providing professional statistical analysis and machine learning services that contributed to the robustness of the results.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has any potential financial conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| AMH |

Anti-Müllerian hormone |

| AUC |

Area under the ROC curve |

| cc |

Cubic centimeter |

| DT |

Decision tree |

| E2 |

Estradiol |

| FSH |

Follicle-stimulating hormone |

| GnRH |

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| KNN |

k-nearest neighbors |

| LH |

Luteinizing hormone |

| LR |

Logistic regression |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| PRL |

Prolactin |

| RF |

Random forest |

| SVM |

Support vector machine |

| UF |

Uterine fibroid |

| UFs |

Uterine fibroids |

| WAI |

WisdomEra Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Yang Q, Ciebiera M, Bariani MV, Ali M, Elkafas H, Boyer TG, et al. Comprehensive Review of Uterine Fibroids: Developmental Origin, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Endocr Rev 2022;43:678–719. [CrossRef]

- Giuliani E, As-Sanie S, Marsh EE. Epidemiology and management of uterine fibroids. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet 2020;149:3–9. [CrossRef]

- Tinelli A, Morciano A, Sparic R, Hatirnaz S, Malgieri LE, Malvasi A, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Uterine Fibroids: A Useful Combination for Diagnosis and Treatment. J Clin Med 2025;14:3454. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad A, Kumar M, Bhoi NR, Badruddeen null, Akhtar J, Khan MI, et al. Diagnosis and management of uterine fibroids: current trends and future strategies. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2023;34:291–310. [CrossRef]

- Micić J, Macura M, Andjić M, Ivanović K, Dotlić J, Micić DD, et al. Currently Available Treatment Modalities for Uterine Fibroids. Med Kaunas Lith 2024;60:868. [CrossRef]

- Uterine fibroids: Learn More – Hormone treatments for uterine fibroids. Inf. Internet, Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2025.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Ciccarone F, Muzii L, Scambia G, Vignali M. Use of oral GnRH antagonists combined therapy in the management of symptomatic uterine fibroids. Facts Views Vis ObGyn n.d.;15:29–33. [CrossRef]

- Mills S. Electronic Health Records and Use of Clinical Decision Support. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2019;31:125–31. [CrossRef]

- Vetrivel S, Rexline D, Gowri MsTD. Decision Support Tool for Uterine Fibroids Treatment with Machine Learning Algorithms – A Study. Int J Sci Res Publ IJSRP 2022;12:442–9. [CrossRef]

- Wisdomera.io. wisdomera.io n.d. https://wisdomera.io/dashboard (accessed June 22, 2025).

- jinekoai.com n.d. https://jinekoai.com/dashboard (accessed June 27, 2025).

- jinekoai | /surgery-estimate-by-hormone-value-myoma-count n.d. https://jinekoai.com/surgery-estimate-by-hormone-value-myoma-count (accessed July 9, 2025).

- Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, Carmona F, Calaf J, Chapron C. The modern management of uterine fibroids-related abnormal uterine bleeding. Fertil Steril 2024;122:20–30. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Zhong J, Yi D, Deng G, Liu Z, Wang W. Assessing the risk of rapid fibroid growth in patients with asymptomatic solitary uterine myoma using a multivariate prediction model. Ann Transl Med 2021;9:370. [CrossRef]

- Commandeur AE, Styer AK, Teixeira JM. Epidemiological and genetic clues for molecular mechanisms involved in uterine leiomyoma development and growth. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21:593–615. [CrossRef]

- Luo N, Guan Q, Zheng L, Qu X, Dai H, Cheng Z. Estrogen-mediated activation of fibroblasts and its effects on the fibroid cell proliferation. Transl Res 2014;163:232–41. [CrossRef]

- Polat G, Arslan HK. Artificial Intelligence in Clinical and Surgical Gynecology. İstanbul Gelişim Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim Derg 2024:1232–41. [CrossRef]

- Huo T, Li L, Chen X, Wang Z, Zhang X, Liu S, et al. Artificial intelligence-aided method to detect uterine fibroids in ultrasound images: a retrospective study. Sci Rep 2023;13:3714. [CrossRef]

- Wright DE, Gregory AV, Anaam D, Yadollahi S, Ramanathan S, Oyemade KA, et al. Developing a Machine Learning-Based Clinical Decision Support Tool for Uterine Tumor Imaging 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Kong W, Li B, Tian Z, Yin C, Zhang M, et al. Revolutionizing hysteroscopy outcomes: AI-powered uterine myoma diagnosis algorithm shortens operation time and reduces blood loss. Front Oncol 2023;13:1325179. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).