Background

People with somatic symptom disorder (SSD) live with real pain and discomfort even though repeated medical tests come back "normal." These unrelenting sensations—and the fears that grow around them—can derail school, work, and family life [

1]. Brain-scan studies offer one clue: regions that tag sensations as urgent, such as the insula and anterior cingulate, seem to fire too easily, while the chemical messenger glutamate appears out of balance [

2].

Standard care—selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, talking therapy, reassurance—helps some people, but many wait months for modest relief or improve only a little [

3]. Interest has therefore turned to medicines that act faster. Low doses of ketamine, given intravenously, can quiet bodily distress within hours, likely by briefly blocking NMDA receptors and then sparking a burst of healthy synaptic growth [

4,

5]. Similar benefits have been reported in patients whose depression or post-traumatic stress is tangled up with chronic pain and other bodily complaints [

6,

7]. Safety work also shows that short ketamine courses are generally well tolerated, even in people with medical comorbidities, when basic monitoring is in place [

8].

Because IV infusions are costly and inconvenient—especially for teenagers—clinicians have started exploring pill-based regimens that aim to mimic ketamine's chain of events. One strategy pairs the cough suppressant dextromethorphan with a low dose of a CYP2D6 inhibitor (to keep dextromethorphan in the system), adds piracetam to boost downstream signalling, and tops up glutamine to nourish recovering synapses [

9].

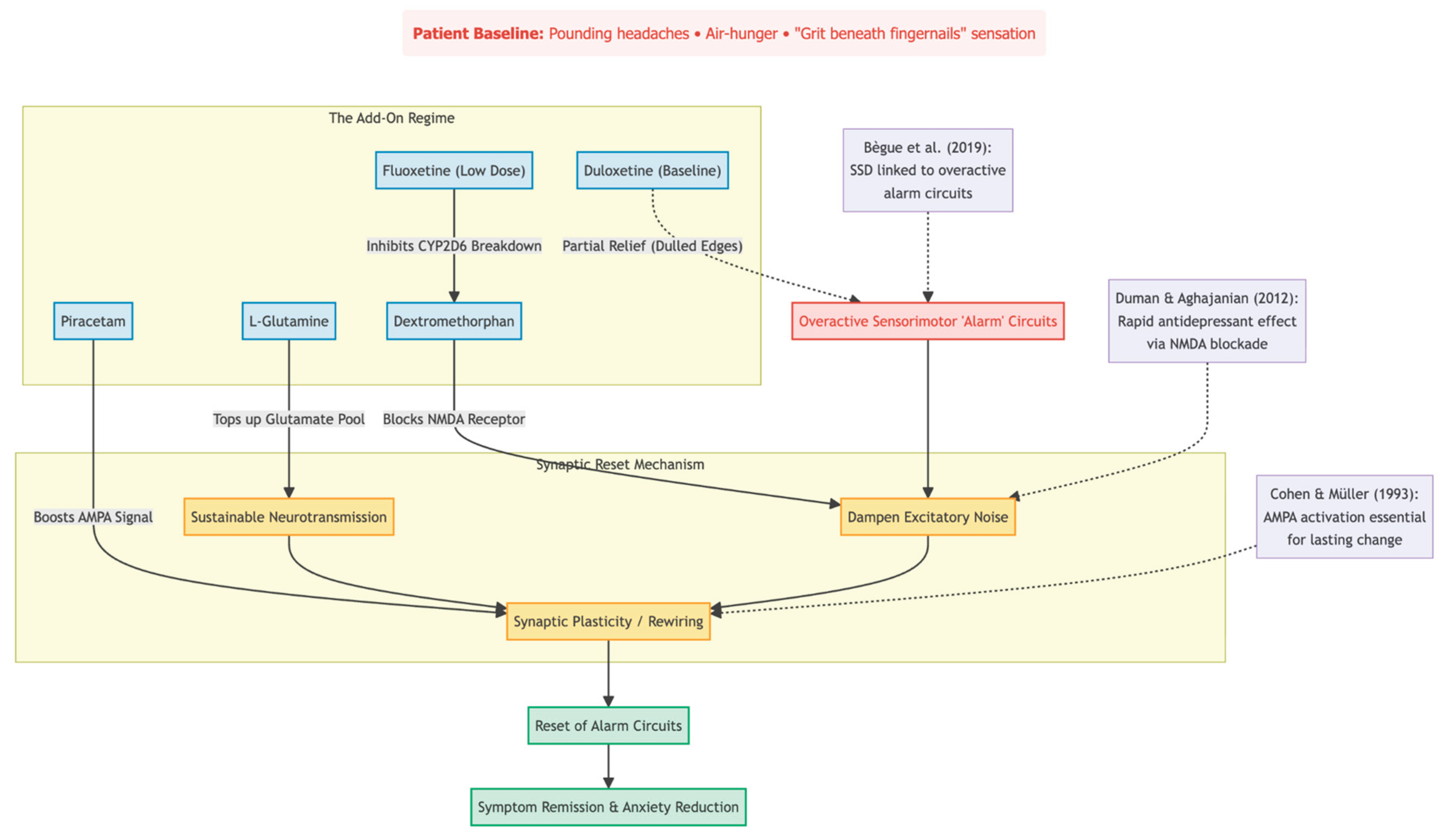

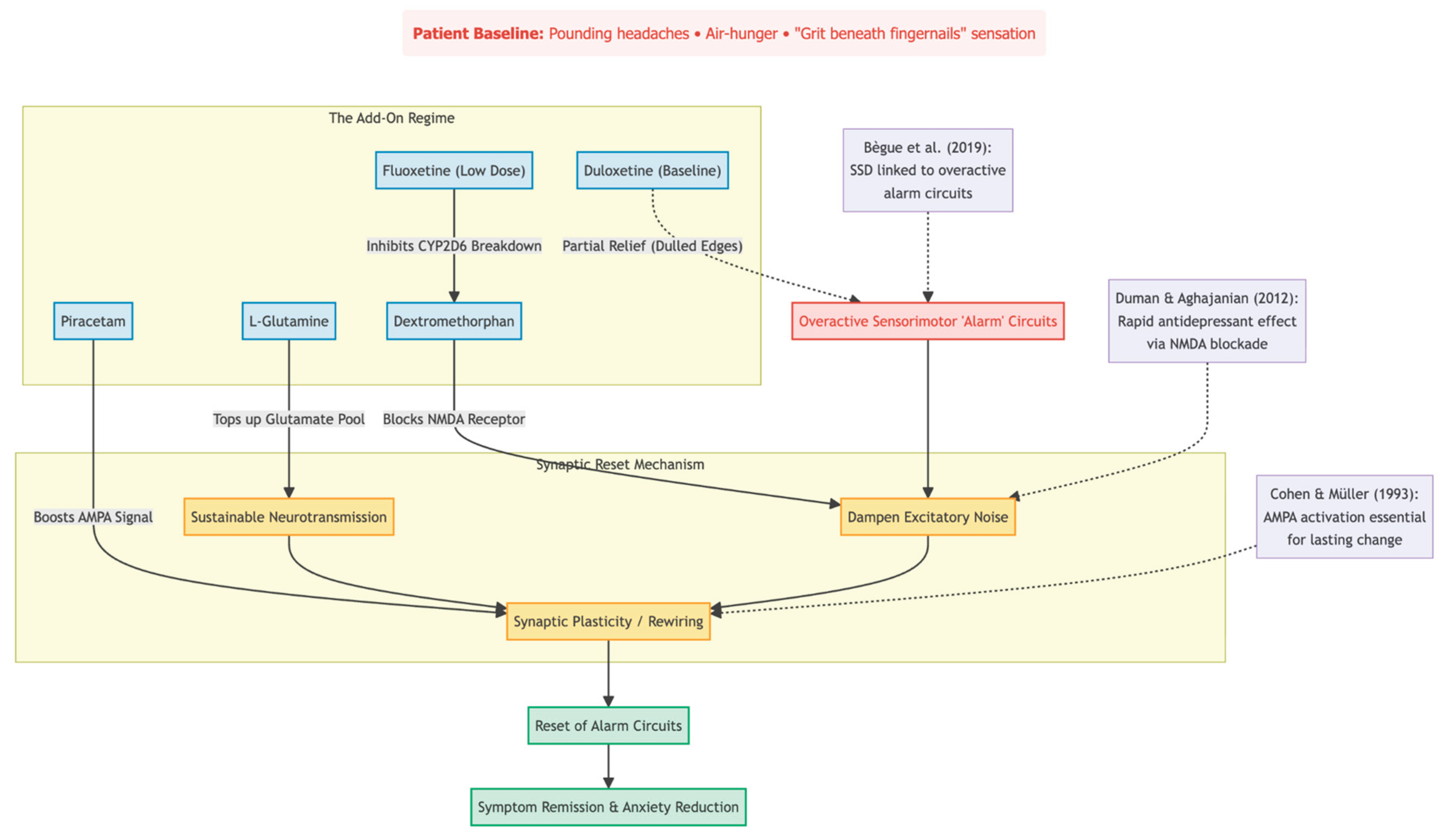

This case report follows a teenage girl whose severe, year-long SSD barely budged with high-dose duloxetine but improved rapidly after the four-drug oral combination was added. Her course illustrates how targeting glutamate pathways might help when usual treatments have failed.

Methods

This single-case report was conducted in a solo private psychiatry practice (Cheung Ngo Medical) in Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong. From early September to late November 2025 the patient was seen exclusively by the author-clinician, who carried out all assessments, prescriptions, and follow-up visits.

Before entry into this observation period the adolescent had been taking duloxetine 60 mg/day for roughly a year with only partial benefit from other doctors. On 2 September 2025 a stepwise, fully oral glutamatergic augmentation programme was started. Dextromethorphan hydrobromide was introduced at 30 mg/day and gradually increased to 60 mg/day (30 mg twice daily) over seven weeks. To prolong dextromethorphan exposure, fluoxetine 10 mg/day was added while the baseline duloxetine was maintained, providing dual CYP2D6 inhibition. One month later piracetam was begun at 600 mg each morning and, by the end of October, raised to 600 mg twice daily. During the same late-October visit, L-glutamine 500 mg/day was added to support longer-term neuroplasticity. Brief adjunctive use of risperidone 0.5 mg at night (for early agitation) and short courses of pregabalin 25–50 mg/day (for transient sensory discomfort) were allowed but were not considered central to the study intervention.

The patient returned roughly every four weeks (2 September, 30 September, 28 October, and 25 November 2025). At each visit she completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; these scores were supplemented by an open clinical interview covering bodily symptom burden, compulsive behaviours, school attendance, and day-to-day functioning. No new psychotherapeutic techniques were introduced during the monitoring window.

Written informed consent for anonymous publication of de-identified data was obtained from the patient's mother, and the patient herself provided written assent. All potentially identifying details have been removed in keeping with ethical guidelines for single-case reporting.

Results

A 17-year-old girl arrived at our clinic in early September 2025 complaining of a year-long barrage of physical symptoms no doctor had been able to explain. She described daily tension-type headaches, episodes of air hunger, vague "all-over" aches, and an intense sensation that something was lodged beneath her fingernails. The last feeling drove her to scratch the nail beds until they bled. These worries had already pushed her to withdraw from school and most social activities. On standard screening, she scored 23 on the PHQ-9 and 9 on the GAD-7, confirming marked low mood and moderate anxiety. During the preceding 12 months she had taken duloxetine from other doctors, escalated to 80 mg and later settled at 60 mg, with only modest relief.

Because the combination of somatic distress, obsessive checking, and functional collapse continued, we offered an oral program aimed at recreating the rapid-acting, glutamatergic effects usually seen with intravenous ketamine. Treatment began on 2 September 2025 with dextromethorphan 30 mg once daily, later increased to 60 mg. To slow dextromethorphan's metabolism we added fluoxetine 10 mg while keeping duloxetine 60 mg in place; both medicines inhibit CYP2D6 and therefore extend dextromethorphan exposure. Piracetam 600 mg daily (titrated to 1,200 mg) was introduced to boost AMPA signaling. Low-dose risperidone (0.5 mg at night) and a brief trial of pregabalin were used for obsessions and sleep as well.

Four weeks into treatment the patient volunteered that she felt "a bit better." Headaches were less frequent, breathing was easier, and her PHQ-9 had fallen to 15. We were motivated to stick to the plan, and by week 8, we were taking 500 mg of L-glutamine every day to help recycle glutamate. There was a little rise in derealisation when she went back to school, but it went away on its own without any modifications to her dose.

The change was very noticeable by week 12 (25 November 2025). She was going to class full-time, and headaches only came up after long study sessions. The nail-scratching habit was gone. The PHQ-9 had dropped to 11 and the GAD-7 to 6, placing anxiety below the clinical threshold. Her mother remarked that this was her daughter's "first stretch of normal life" in more than a year.

No adverse effects attributable to the core four-drug combination emerged during the 12-week observation period; transient drowsiness from risperidone resolved spontaneously. The close temporal link between initiation of the glutamatergic stack and the patient's sustained recovery suggests that completing the NMDA-to-AMPA neuroplasticity sequence may offer a practical, oral route to rapid relief in severe, treatment-resistant somatic symptom disorder.

Conclusions

When this teenager arrived at our clinic, she had lived for more than a year with pounding headaches, air-hunger, and a maddening feeling of grit beneath her fingernails. High-dose duloxetine had dulled the edges but never let her return to class. What changed the picture was a simple four-pill add-on: low-dose dextromethorphan, a tiny amount of fluoxetine to slow its breakdown, piracetam, and, a month later, L-glutamine. Within three months her symptoms were no longer running her life; mood scores fell by half, and anxiety slipped below the clinical line.

Why might this have worked? Brain-scan research points to overactive "alarm" circuits in SSD [

2]. Briefly blocking NMDA receptors—ketamine's first step—can reset those circuits, but ketamine requires IV lines and monitoring. Dextromethorphan, kept active by fluoxetine, can deliver a similar NMDA block in pill form [

4]. Piracetam then boosts the follow-up AMPA signal that animal studies say is essential for lasting change [

10,

11]. Finally, glutamine tops up the brain's own glutamate supply, supporting new synapses without the risk of "over-revving" the system [

12].

The improvement we saw mirrors reports from adults with depression and heavy body symptoms who responded quickly to dextromethorphan–bupropion [

13]. Our case suggests that adding targeted AMPA support and glutamine can push the benefit even further in pure SSD. Equally important, the regimen was easy to take and caused no noticeable side-effects—no blood-pressure spikes, no dissociation, nothing that forced a dose change.

One success story is not proof. Placebo effects, growing maturity, or delayed benefit from duloxetine could all play a part. Still, the speed, size, and stability of her recovery after many stalled months argue that the glutamatergic stack made a real difference. Controlled studies that track physical-symptom scales in SSD seem the logical next step.

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding Statement

None declared.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 2013.

- Bègue I, Adams C, Stone J, et al. Structural alterations in functional neurological disorder and related conditions: a software and hardware problem?. NeuroImage. Clinical. 2019;22:101798. [CrossRef]

- Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2018;20(1):23–31. [CrossRef]

- Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2012;338(6103):68–72. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2010;329(5994):959–964. [CrossRef]

- Chen MH, Wu HJ, Li CT, et al. Low-dose ketamine infusion for treating subjective cognitive, somatic, and affective depression symptoms of treatment-resistant depression. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2021;66:102869. [CrossRef]

- Liriano F, Hatten C, Schwartz TL. Ketamine as treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder: a review. Drugs in context. 2019;8:212305. [CrossRef]

- Szarmach J, Cubała WJ, Włodarczyk A, et al. Somatic Comorbidities and Cardiovascular Safety in Ketamine Use for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2021;57(3):274. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. DXM, CYP2D6-Inhibiting Antidepressants, Piracetam, and Glutamine: Proposing a Ketamine-Class Antidepressant Regimen with Existing Drugs. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cohen SA, Müller WE. Effects of piracetam on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor properties in the aged mouse brain. Pharmacology. 1993;47(4):217–222.

- Koike H, Iijima M, Chaki S. Involvement of AMPA receptor in both the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in animal models of depression. Behavioural brain research. 2011;224(1):107–111. [CrossRef]

- Son H, Baek JH, Go BS, et al. Glutamine has antidepressive effects through increments of glutamate and glutamine levels and glutamatergic activity in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2018;143:143–152. [CrossRef]

- Iosifescu DV, Jones A, O'Gorman C, et al. Efficacy and Safety of AXS-05 (Dextromethorphan-Bupropion) in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial (GEMINI). The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2022;83(4):21m14345.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).