3.2. Planning of Experiments and Concrete Test Results

The planning matrix and experimental data are shown in

Table 5.

As a result of statistical analysis of the experimental data, adequate regression equations were obtained with a confidence probability of 0.95 for the water demand of the concrete mixture with a slump of 10–12 cm and the compressive strength at ages of 7, and 28 days. The statistical analysis included the following components: a full ANOVA table and a lack-of-fit test. The resulting statistical characteristics are presented in

Appendix A. Statistical analysis of the results and construction of graphical dependencies were carried out using the ’Statistica 14.0’ software package [

36]. The analysis of the obtained equations shows that all studied factors affect the water demand and compressive strength of concrete with RCF addition, and their influence can be quantitatively evaluated and ranked (

Table 6).

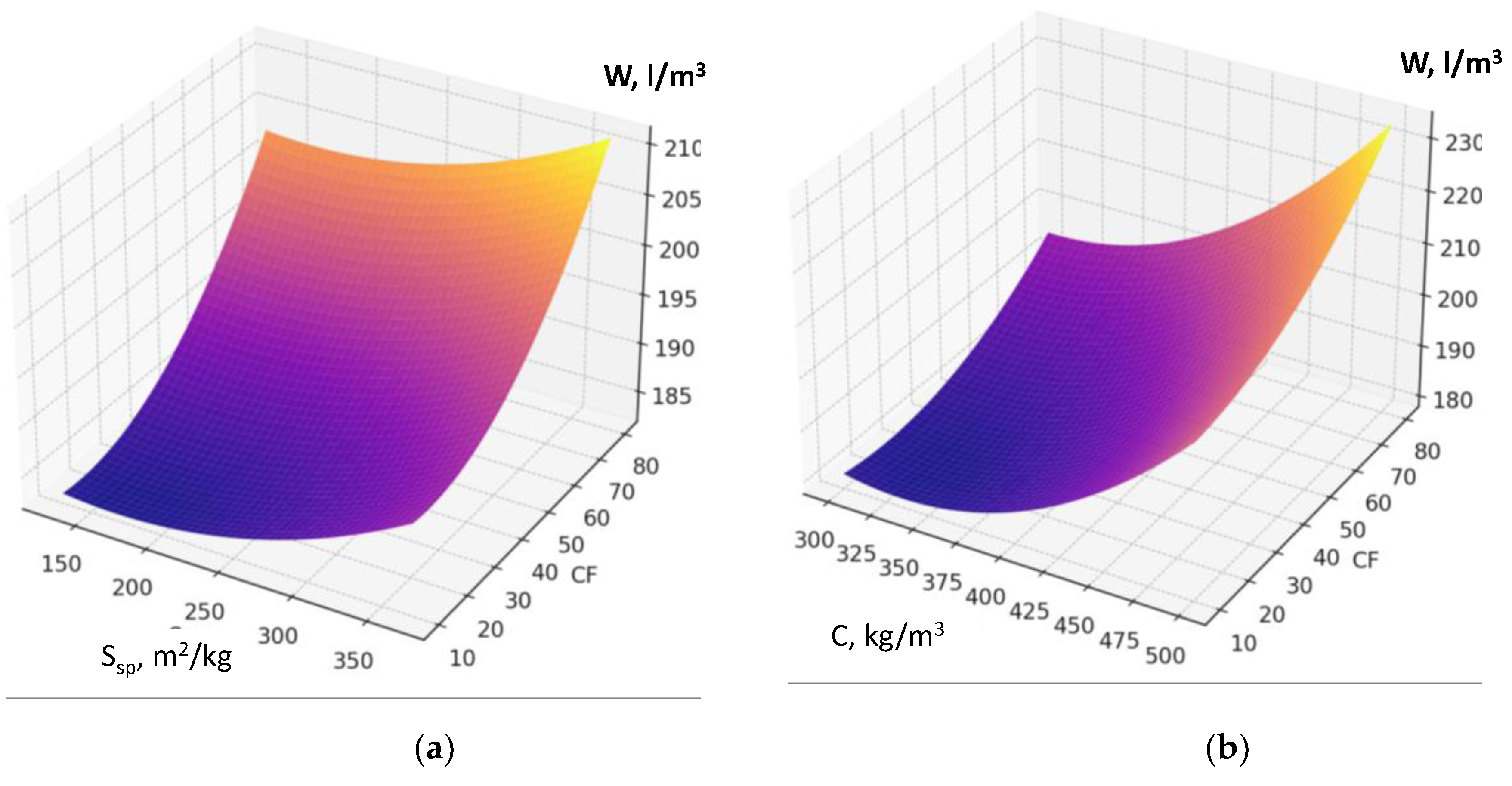

Recycled concrete fines dosage if its interaction with other factors is not considered, increases water demand due to its porosity and the presence of amorphized cement hydration products (

Figure 6 a, b).

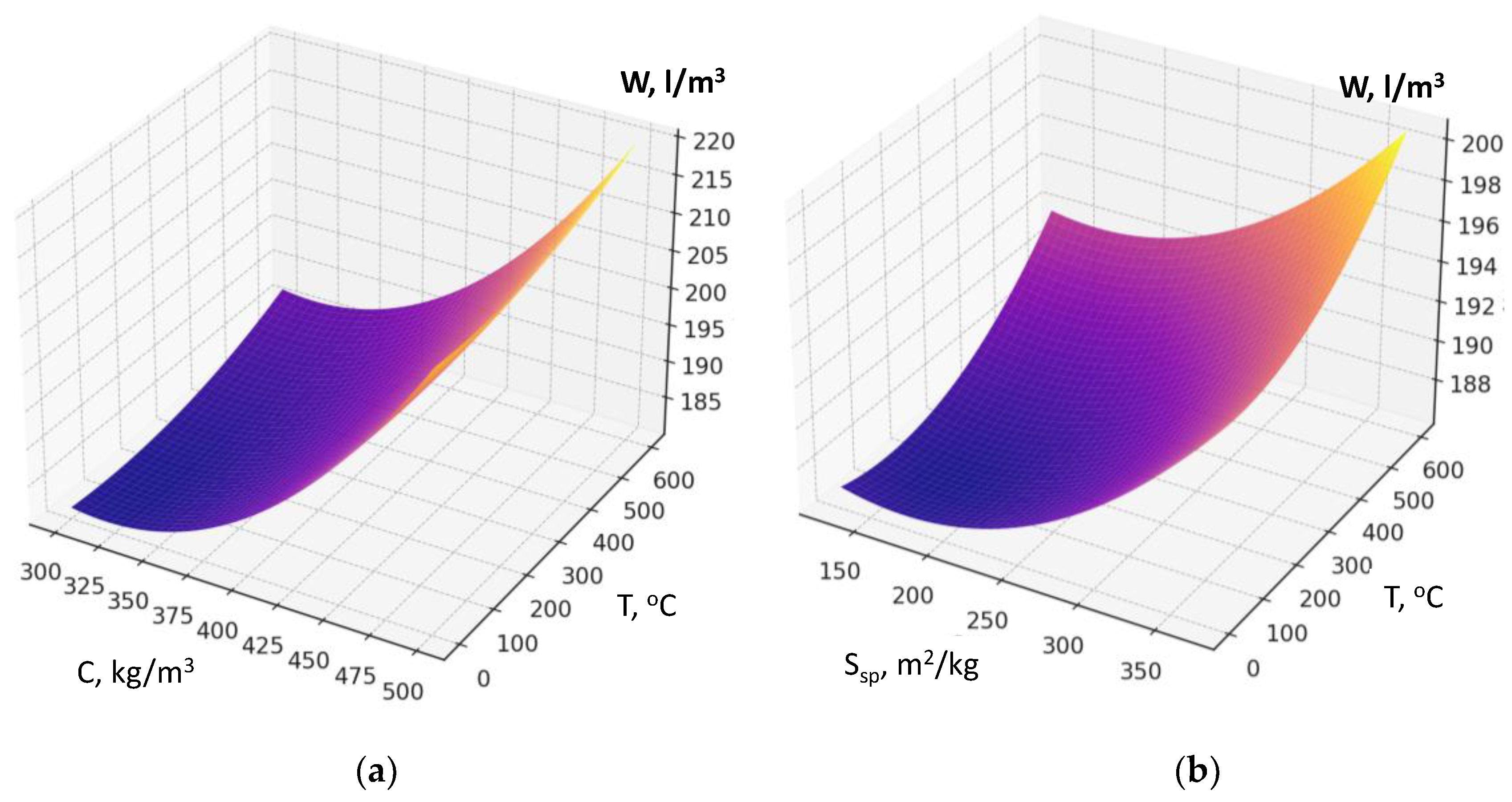

The factors responsible for RCF activation (specific surface area, Figure 4a; thermal treatment temperature; dosage of chemical activator Na₂SiF₆) also affect water demand, although their impact is comparatively less pronounced (

Figure 7). An increase in factor X₂ (cement consumption) causes the maximum rise in water demand of the fresh concrete within the studied range. The presence of a significant quadratic effect of this factor indicates that the highest increase in water demand is observed at cement consumption levels above 400 kg/m³ (

Figure 7b, Figure 5a). It confirms the well-known rule of constant water demand of concrete mixtures [

26].

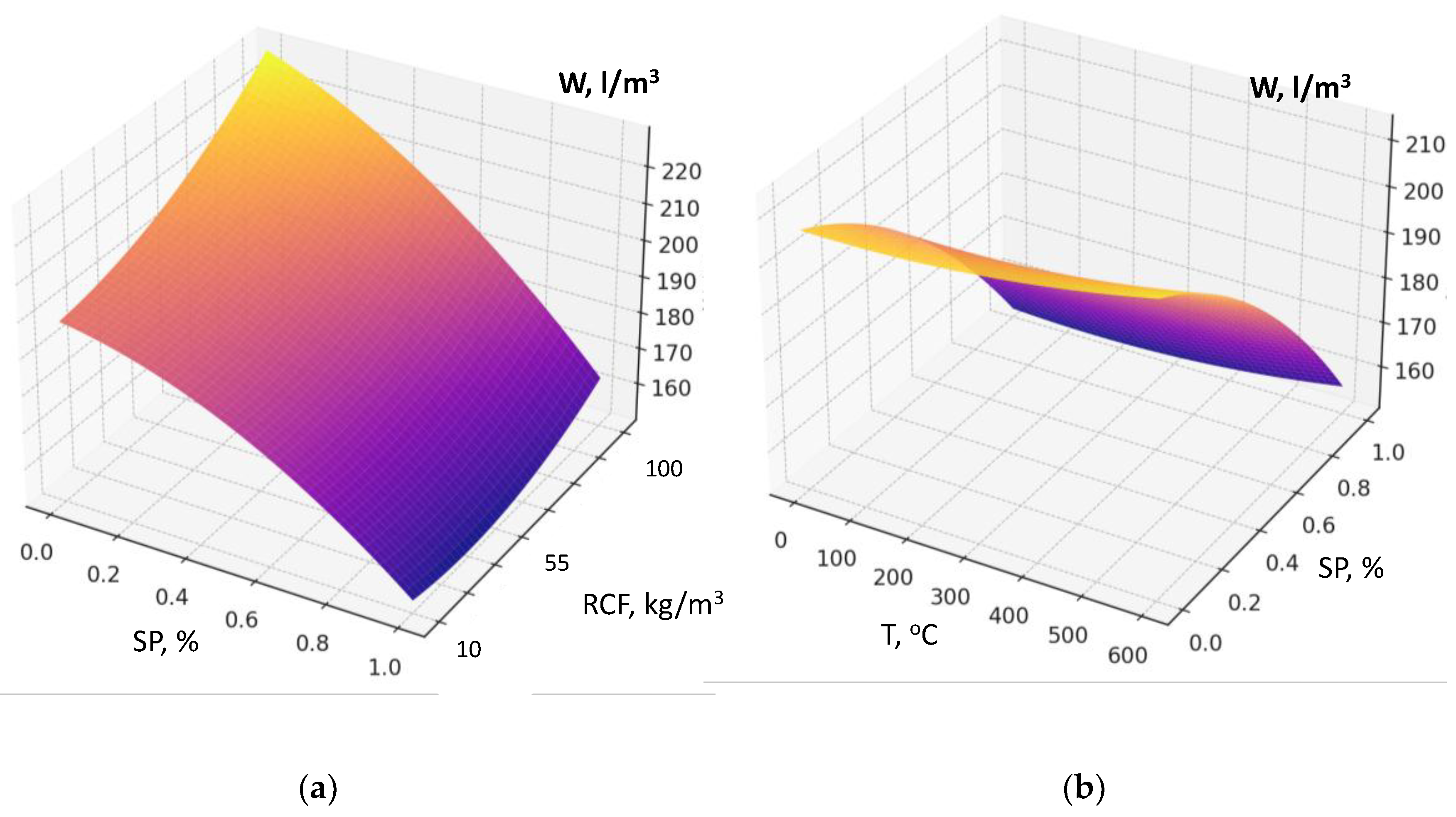

The maximum reduction in water demand is caused by factor X₄ (superplasticizer SP dosage) (

Figure 8a, b). The higher the SP content is, the less water is required to achieve the normal consistency. This factor is characterized by the most significant negative interactions in the model (X₄×X₁, X₄×X₂, X₄×X₃, X₄×X₅): SP effectively compensates the increased water demand caused by other factors (

Figure 8a). The increasing of RCF specific surface area (S

sp, X₁) also increases water demand by 2–5 l/m³, since fine particles require more water for wetting and dispersion in the cement matrix. When combined with high cement content, the increase in water demand reaches 10–15 l/m³. The thermal treatment temperature of RCF (X₃) leads to a relatively small increase in water demand, which may be due to surface activation and the formation of more hydrophilic and reactive phases (2–10 l/m³) (

Figure 8b). Factor X₆ (Na₂SiF₆ content) causes a slight decrease in water demand within the studied range due to a certain plasticizing effect (5–15 l/m³).

An important feature of this model is the presence of significant factor interaction coefficients, the consideration of which makes it possible to draw several important conclusions. For example, the interaction of the amount of RCF and superplasticizer clearly shows that increasing SP dosage almost completely neutralizes the additional water demand caused by an increase in RCF content (

Figure 8a): the increase in water demand of 25–35 l/m³ is reduced to 5–10 l/m³ or less. The interactions of SP with RCF specific surface area (S

sp) and RCF thermal treatment temperature (T) are negative in terms of their influence on W: under the action of SP, the negative effects of increased dispersion or thermal treatment are significantly weakened (

Figure 8b). Thus, to minimize water demand at high RCF content, especially at elevated cement consumption, the key solution is to increase the SP dosage (reducing water demand by about 50±10 l/m³).

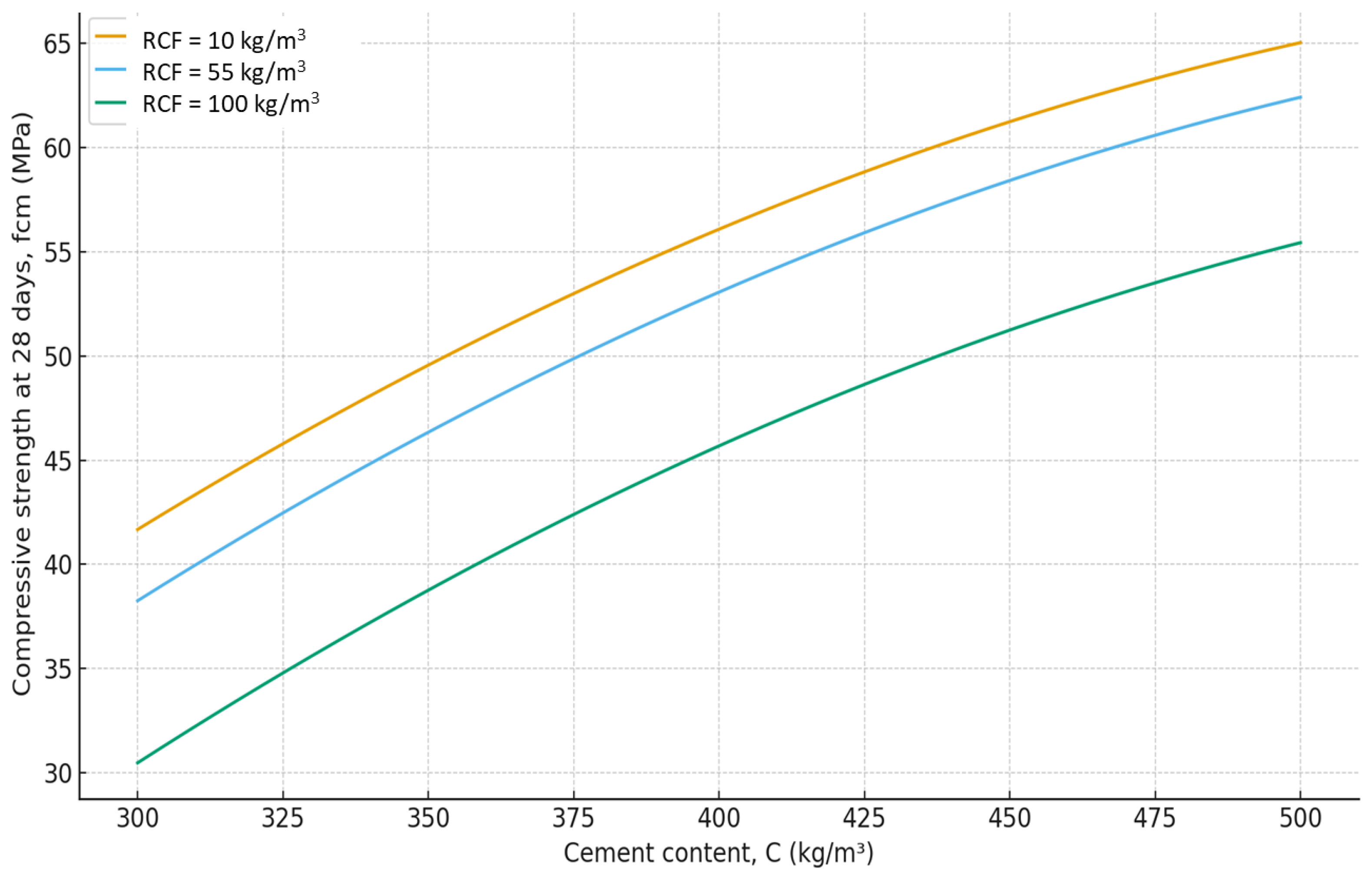

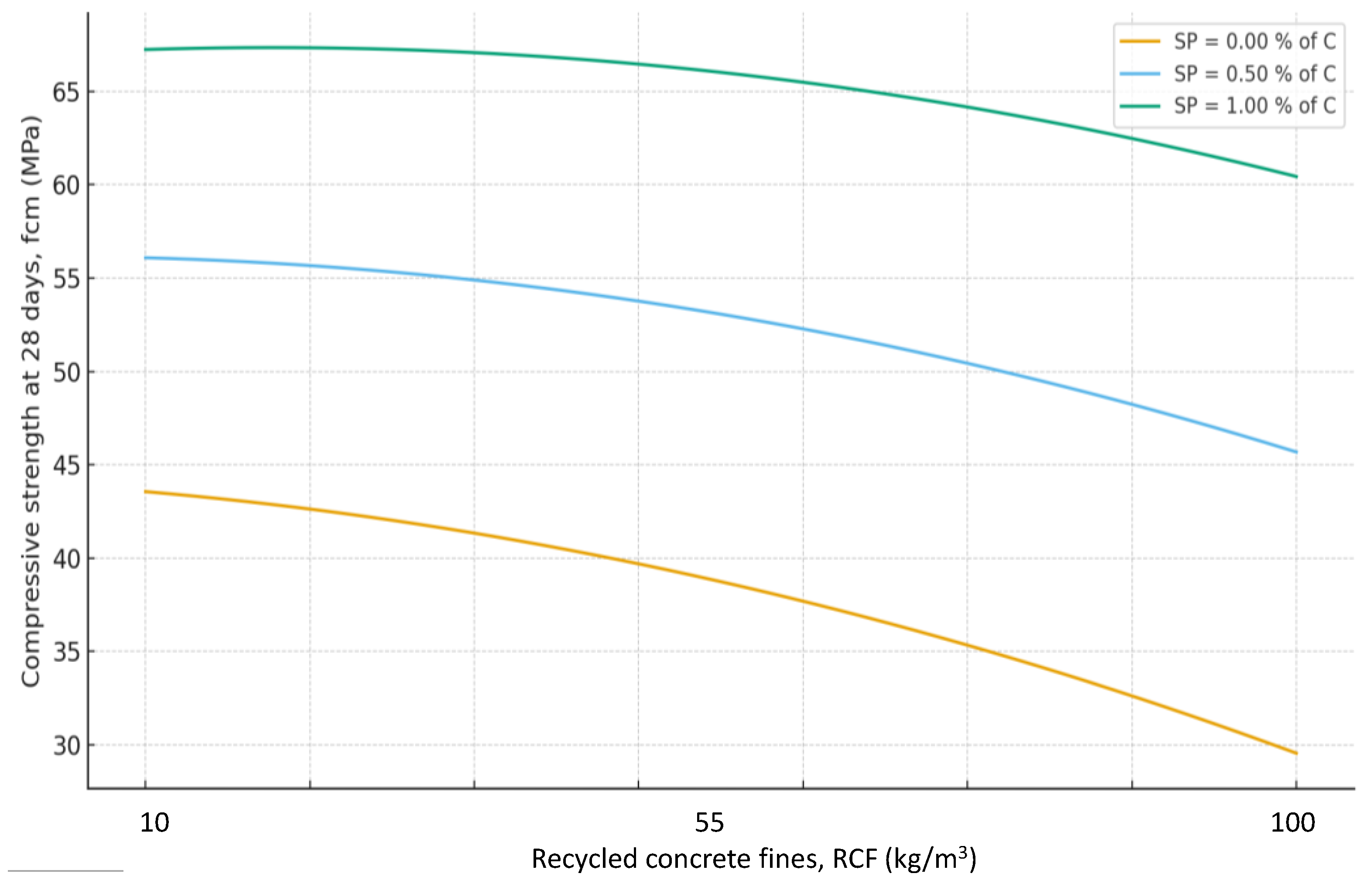

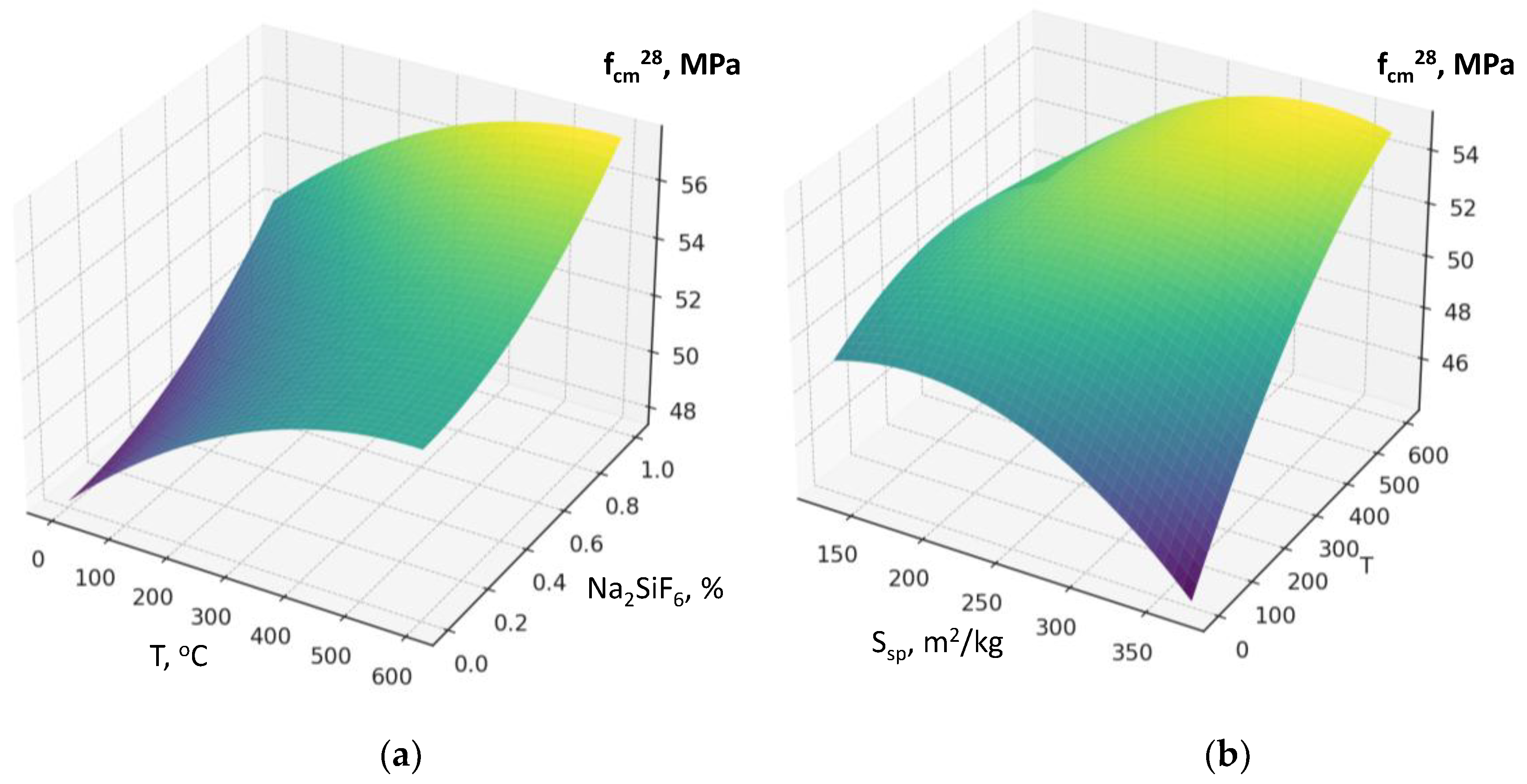

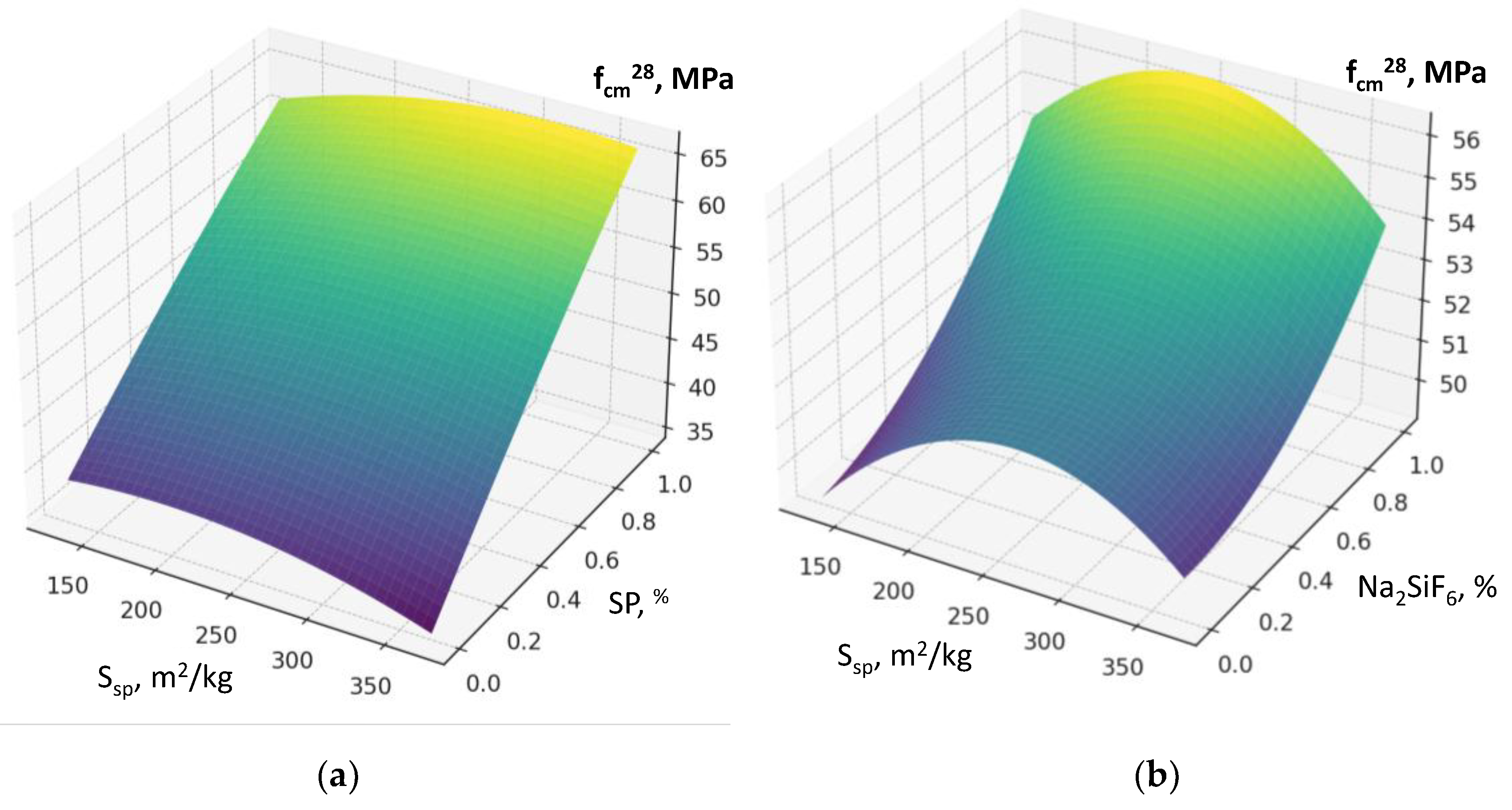

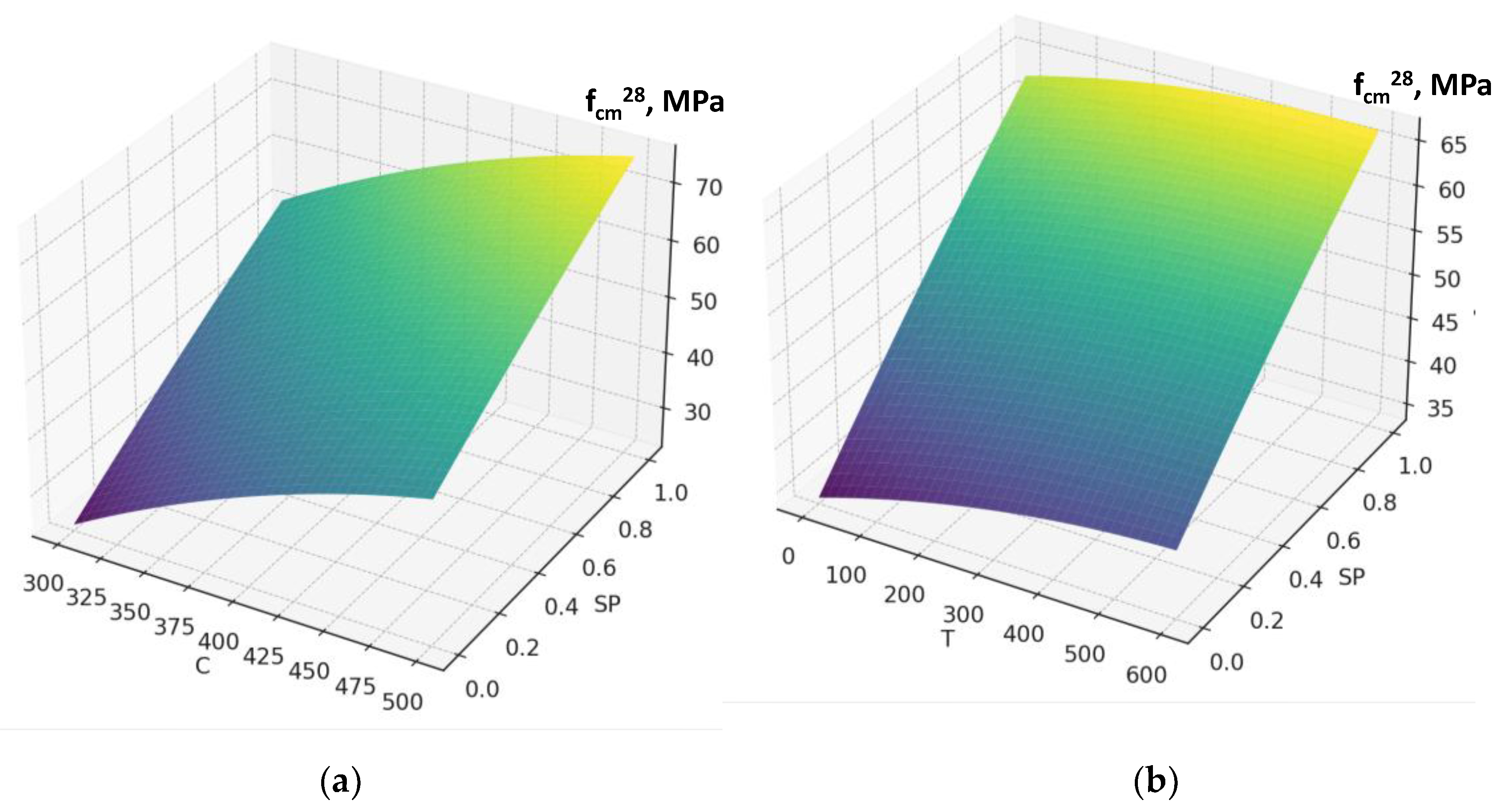

The compressive strength model with six factors (2) showed a high level of adequacy (R² ≈ 0.991, average error ≈ 1.8 MPa). This allows not only qualitative but also quantitative evaluation of the influence of individual parameters. According to the model (equation), the compressive strength of concrete at 28 days varies within a fairly wide range of 20–70 MPa, which is caused by significant variations in the w/c ratio (from 0.35 to 0.68) (

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

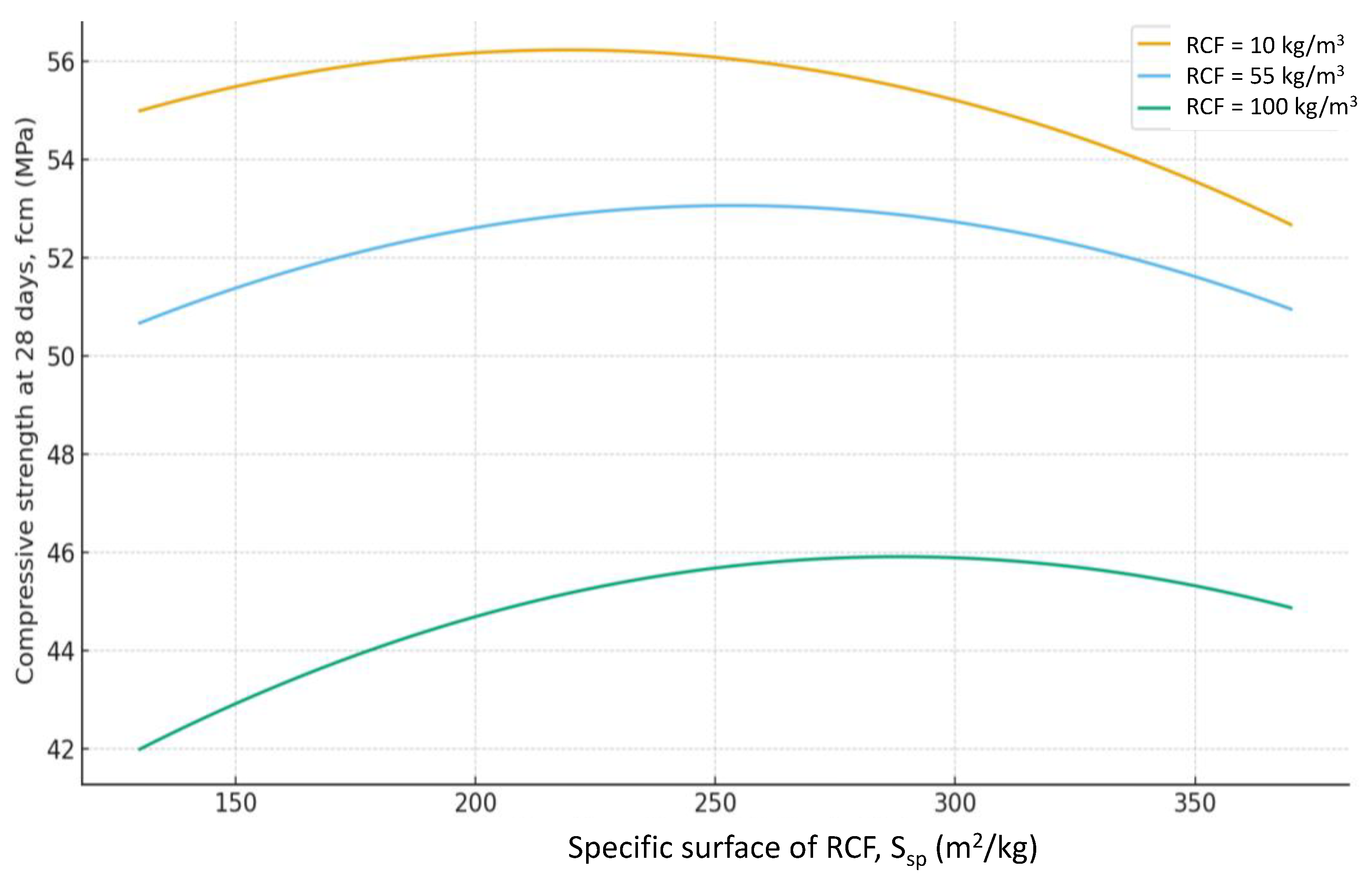

As expected, the greatest influence on strength belongs to factors X₂ and X₄ (cement content and SP). An increase in cement consumption and, accordingly, the cement-to-water ratio from the minimum to maximum level results in a strength gain of about 24 MPa (42–45% relative to the average), while an equivalent increase in superplasticizer dosage provides about 27 MPa (50–55%). At the same time, an increase in the RCF dosageis negative: rising from the minimum to the maximum level reduces strength by approximately 8–10 MPa (16–18%) (

Figure 7). The effect of different RCF activation methods on concrete strength is mixed. Increasing thermal activation temperature causes a noticeable effect: the difference between low (non-thermally activated RCF) and high T is about 9%. Activation by Na₂SiF₆ within the studied range produces a strength gain of about 7%. Increasing the specific surface area of RCF by grinding in a ball mill (S

sp) shows an ambiguous effect, producing the greatest strength increase near the mid-level of variation (250 m²/kg); further fineness increase reduces strength due to higher water demand (

Figure 10).

Interactions between factors confirm that the maximum efficiency of using the RCF as a mineral additive is achieved through combined effects. The most important is the interaction between RCF and SP (X₅ and X₄) (

Figure 8): if SP is not used, increasing RCF content reduces strength on average by 10–12 MPa, but with sufficient SP dosage (up to 1%) the losses decrease to 3–5 MPa, i.e., they are almost fully compensated. The interaction between Ssp and SP is also positive: with SP present, the effect of mechanical activation of RCF nearly doubles (

Figure 11a). The combination of mechanical and thermal activation (factors X₁ and X₃) (

Figure 10b) allows an additional strength gain of up to 4 MPa compared with the simple sum of their effects. Other interactions (e.g., C×SP or T×Na₂SiF₆) are less significant (within 1–2 MPa) (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

Thus, the dispersed fraction of recycled concrete in the form of concrete powder generally reduces strength by 15–20%, but this effect is significantly offset by the use of SP and additional activation. Key interactions (Ssp×T, Ssp×SP, SP×RCF) demonstrate that the mechanochemical activation of RCF provides maximum effect only when combined with thermal treatment and plasticization.

The above-described tendencies in factor influence on 28-day strength are generally preserved at earlier curing ages (3 and 7 days), although the negative effect of RCF addition is comparatively stronger.

The obtained models of strength and water demand of concretes with dispersed fractions of recycled concrete allow the prediction of concrete properties and the determination of mix composition for a given target strength.

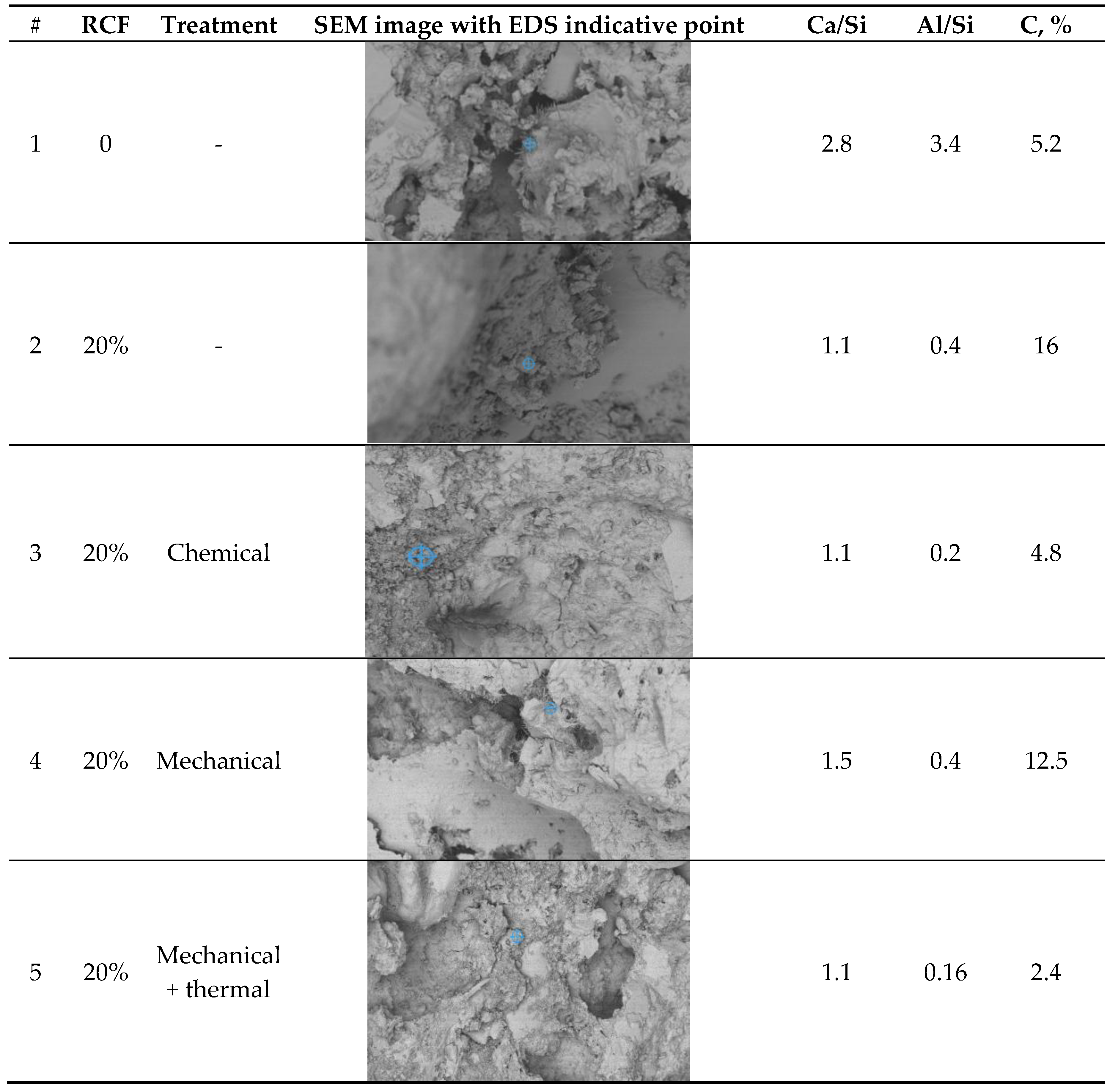

There had been taken and analysed SEM images of concrete for the 5 samples:

Control,

20% recycled concrete fines;

20% recycled concrete fines+ Na2SiF6 (chemical activation).

20% recycled concrete fines (ground/nonground = 50/50);

20% recycled concrete fines (ground + thermally treated)

The key idea is to determine the effect of recycled concrete fines (RCF) on microstructure, chemistry, reactivity, mechanical performance, and ways mechanical and thermal treatment modifies these effects compared to a control concrete.

It was supposed that RCF reduces Ca/Si in the paste at increasing C and slightly reduces early strength vs control but improves late-age strength due to filler/pozzolanic effects (nucleation effect).

Chemical activation with Na₂SiF₆ is supposed to increase reactive Si/Al availability (higher amorphous content), accelerating pozzolanic reactions and improving strength and CH consumption relative to untreated RCF.

Mechanical grinding was expected to increase surface area and early reactivity, but does not change bulk chemistry; the 50/50 mix yields a heterogeneous microstructure and intermediate performance.

Figure 15.

SEM micrograph of concrete microstructure:a) 1; b) 2; c) 3;d) 4; e) 5. (according to

Table 4).

Figure 15.

SEM micrograph of concrete microstructure:a) 1; b) 2; c) 3;d) 4; e) 5. (according to

Table 4).

As it can be seen at micrographs RCF improves the continuity between aggregate and paste phases. Concrete fines serve mainly as fine filler, improving particle packing.

The SEM-EDS analysis presented in

Table 7 reveals distinct microstructural and compositional differences between the control concrete and those modified with recycled concrete fines (RCF), with or without additional treatment. The key outcomes reflect the influence of RCF on the calcium-silicate-hydrate (C–S–H) chemistry, degree of carbonation, and presence of other hydration or filler phases.

As it can be seen from

Table 7, for control concrete Ca/Si ratio is the highest among all the samples tested as there is higher portlandite content (CH) from full cement hydration. There is also a low level of carbonation since the matrix is denser, with lower open porosity (especially if well cured), and less CO₂ can diffuse inside.

The control concrete sample exhibits the highest Ca/Si ratio (≈ 2.8) and Al/Si (≈ 3.4) among all samples, suggesting the dominance of portlandite (Ca(OH)₂) and potentially aluminate-rich phases (e.g., AFm/AFt or hydrogarnet). These values are much higher than those typical of C–S–H gel (Ca/Si ≈ 1.2–1.8), implying limited pozzolanic activity and a fully hydrated cement system.

The low carbon content (5.2%) indicates minimal carbonation, consistent with a dense, well-cured microstructure with limited CO₂ ingress. The microstructure is likely dominated by unreacted clinker phases, portlandite, and conventional C–S–H, with minimal influence from recycled or supplementary materials.

The inclusion of 20% RCF for sample 2 leads to a substantial drop in Ca/Si (≈ 1.1) and Al/Si (≈ 0.4), which may reflect the formation of a low-Ca C–S–H or C–A–S–H phase. The high carbon content (16%) strongly suggests the presence of pre-carbonated fines from the RCF or increased carbonation.

Sample 3 with chemically activated RCF with Na₂SiF₆ results in a similar Ca/Si (≈ 1.1) as untreated RCF, but with lower Al/Si (≈ 0.2) and a reduced carbon content (4.8%). The activator appears to enhance silica dissolution, leading to the formation of Si-rich C–A–S–H gels with improved density and reduced carbonation. This aligns with expectations from chemically assisted pozzolanic systems, where lower Ca/Si ratios are associated with more durable C–S–H structures. The reduced carbon content supports the conclusion that chemical treatment helps densify the microstructure and limits CO₂ penetration.

Sample 4 presents a moderate Ca/Si ratio (≈ 1.5), with relatively high Al/Si (≈ 0.4) and elevated carbon (12.5%). The values suggest a heterogeneous matrix, likely due to the mixed presence of ground and unground RCF particles.

For sample 5 thermal treatment can lead to decomposing portlandite and partial dehydration C–S–H, leading to a more silica-rich surface, lowering the Ca/Si ratio compared to the mechanically treated sample. Al-compounds dehydroxylate/ decompoe reducing Al/Si. Carbonates decompositng leads to the reduction of C.

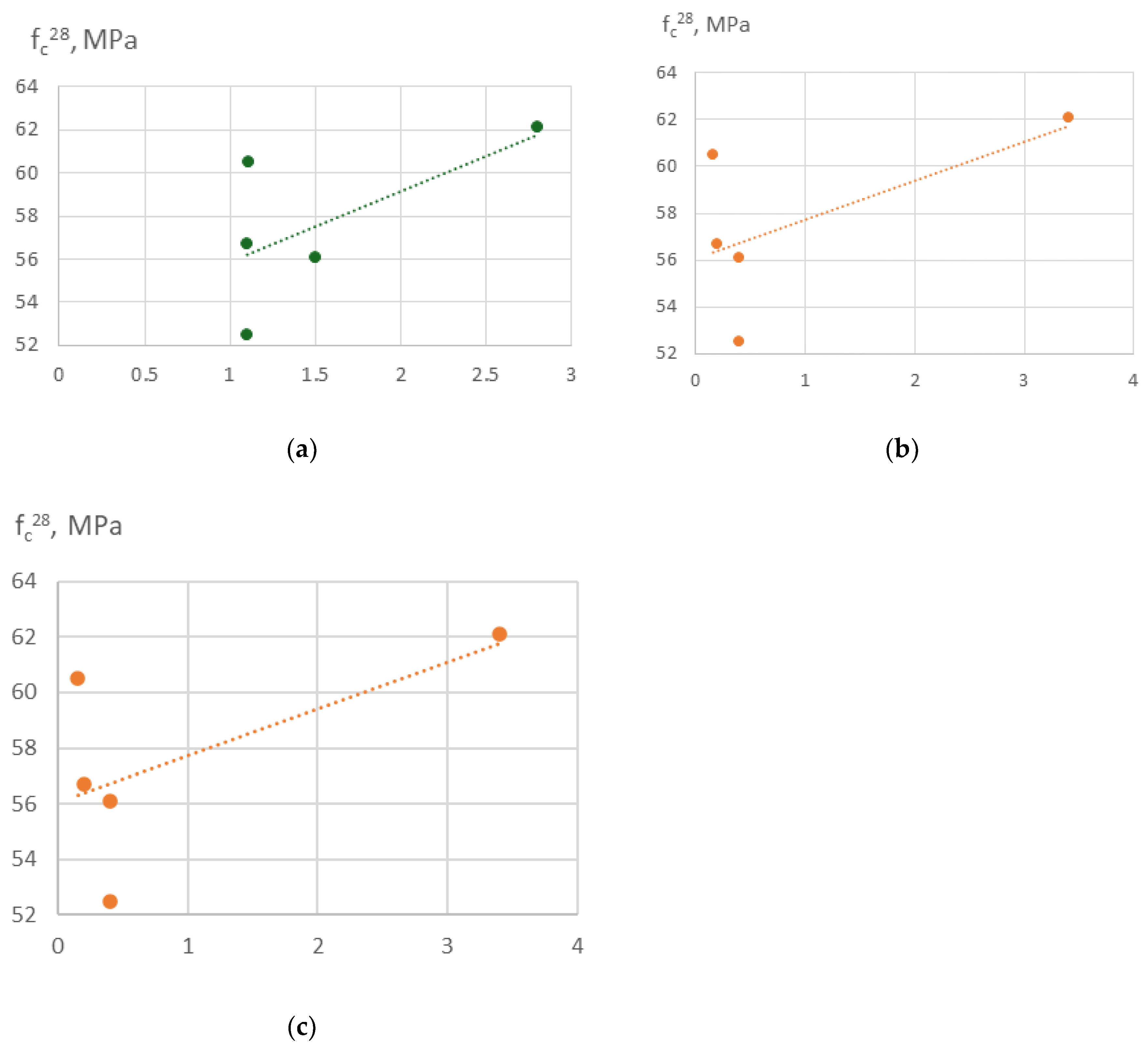

Based on this increasing strength at growing Ca/Si (

Figure 16a) may be explained by grrwing amount alcium reacting with silicates from recycled fines, denser microstructure due to calcium-rich C-S-H fills voids between recycled fines and aggregates more effectivel and improved bonding between recycled fines and the new paste.

Increasing Al/Si (

Figure 16b) in concrete enhances compressive strength because aluminum substitutes into C-S-H to form cross-linked C-A-S-H, densifying the microstructure and improving bonding between matrix and aggregates/fines. Essentially, Al acts like a “cross-linker” in the cement gel network.

Increased carbon content (

Figure 16c) leads to reduction of reactivity of the RCF, increased porocity anI iterferes with hydration. It leads to formation weaker microstructure and lower compressive strength.