Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

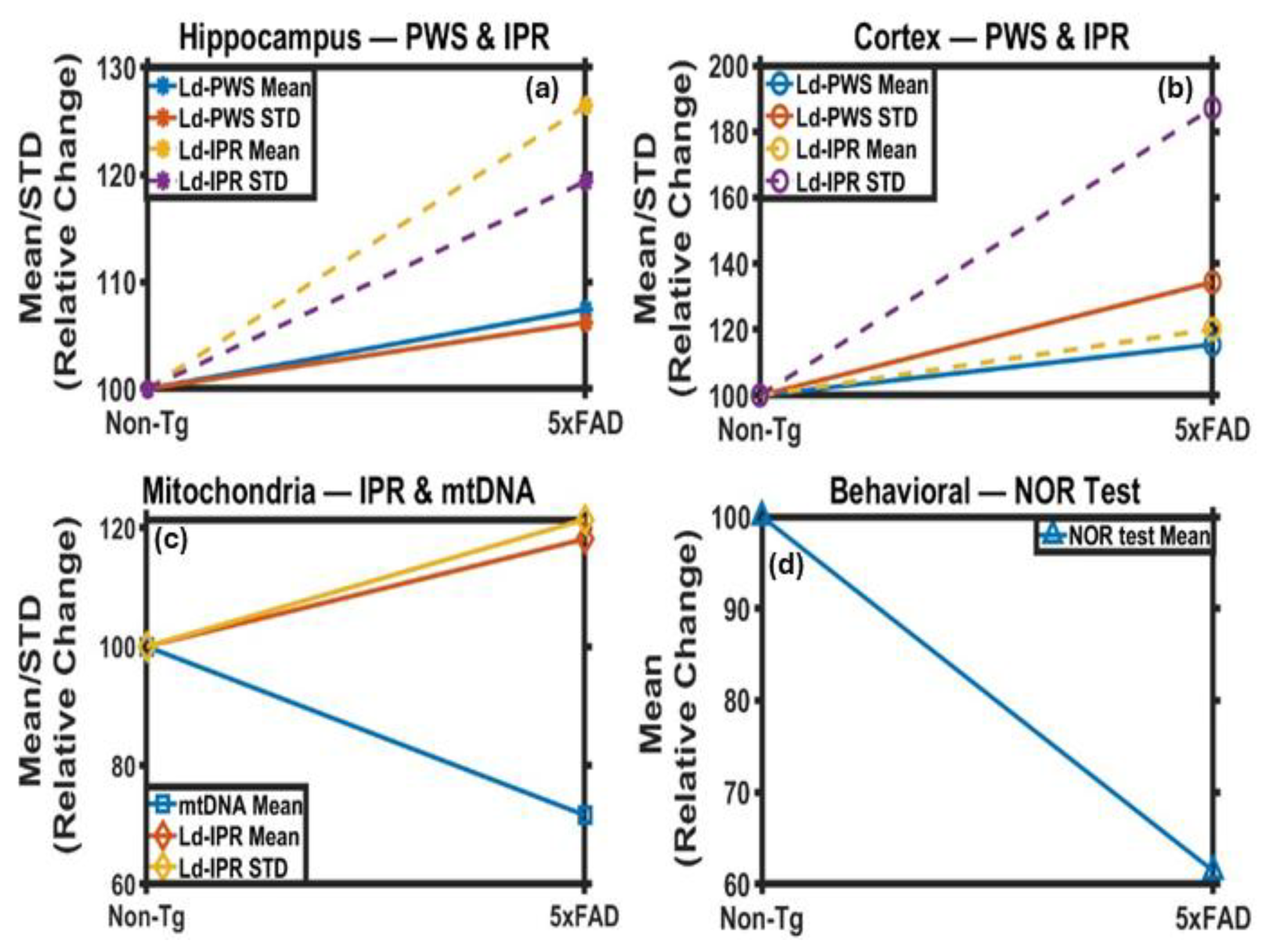

2.1. PWS Analysis of Mice Brain Tissues

2.1.1. PWS Analysis of Cortical Tissues

2.1.2. PWS Analysis of Hippocampus Tissues

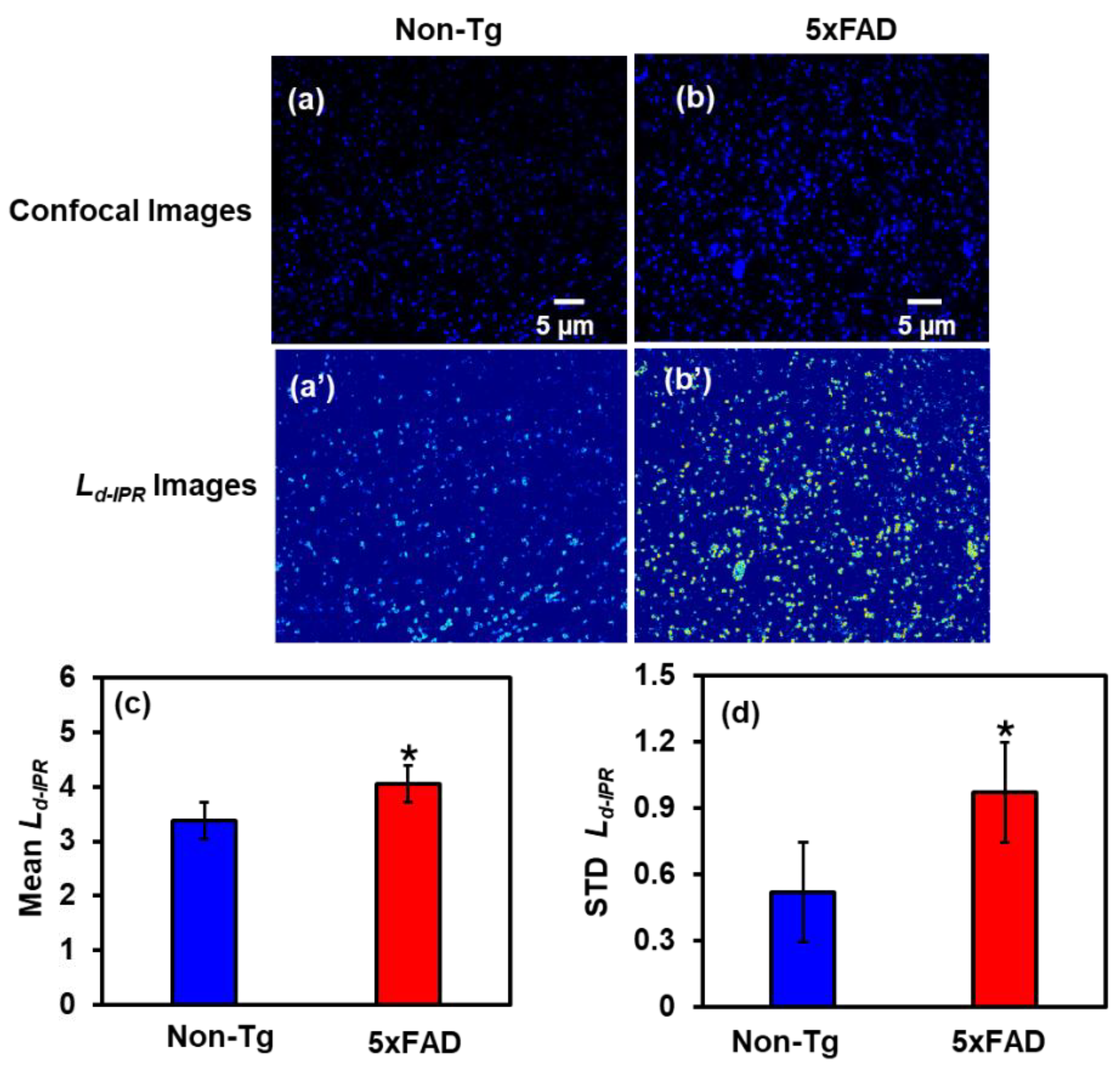

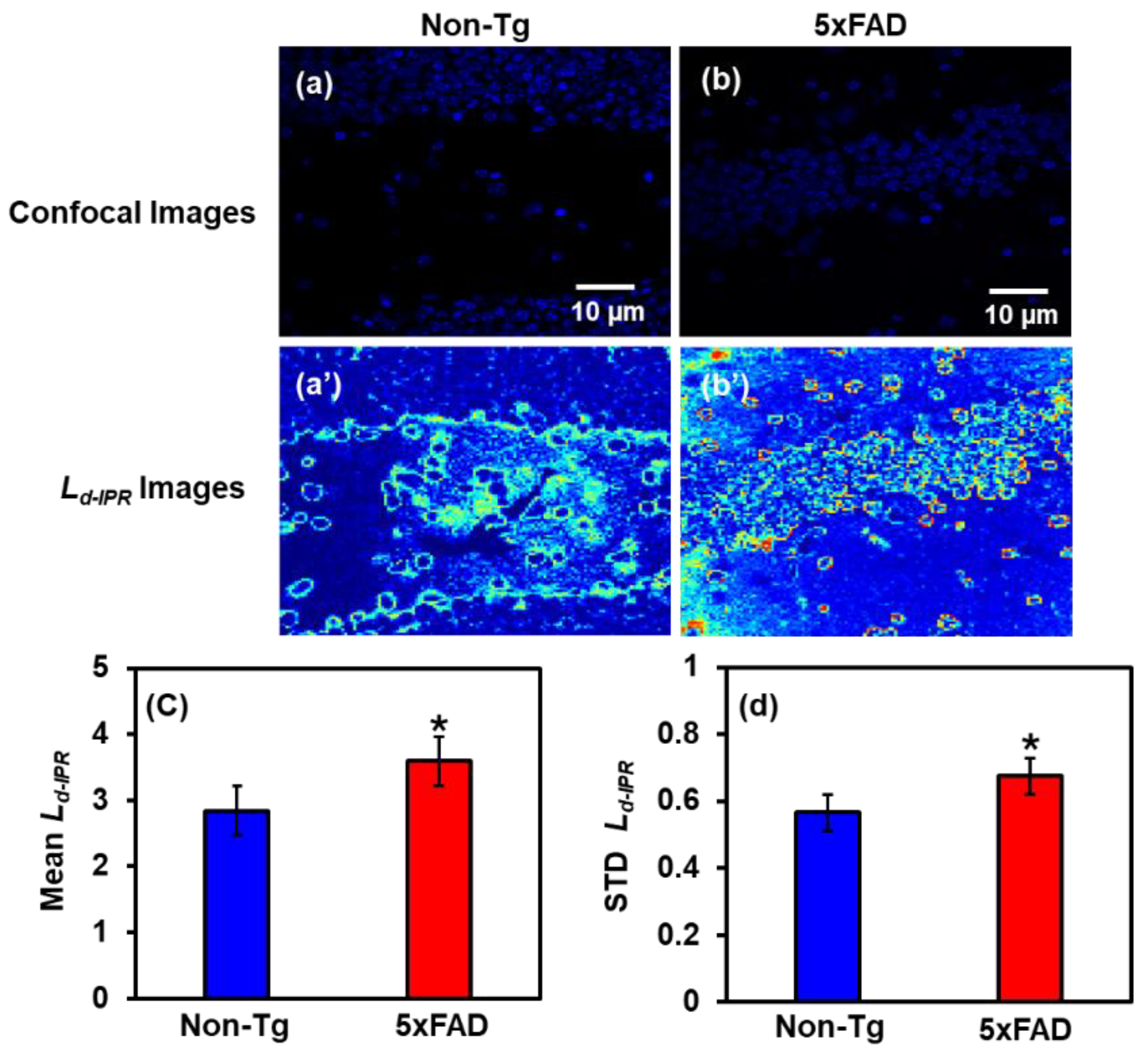

2.2. IPR Analysis of Mice Brain Tissues

2.2.1. IPR Analysis of Cortex Region

2.2.2. IPR Analysis of Hippocampus Region

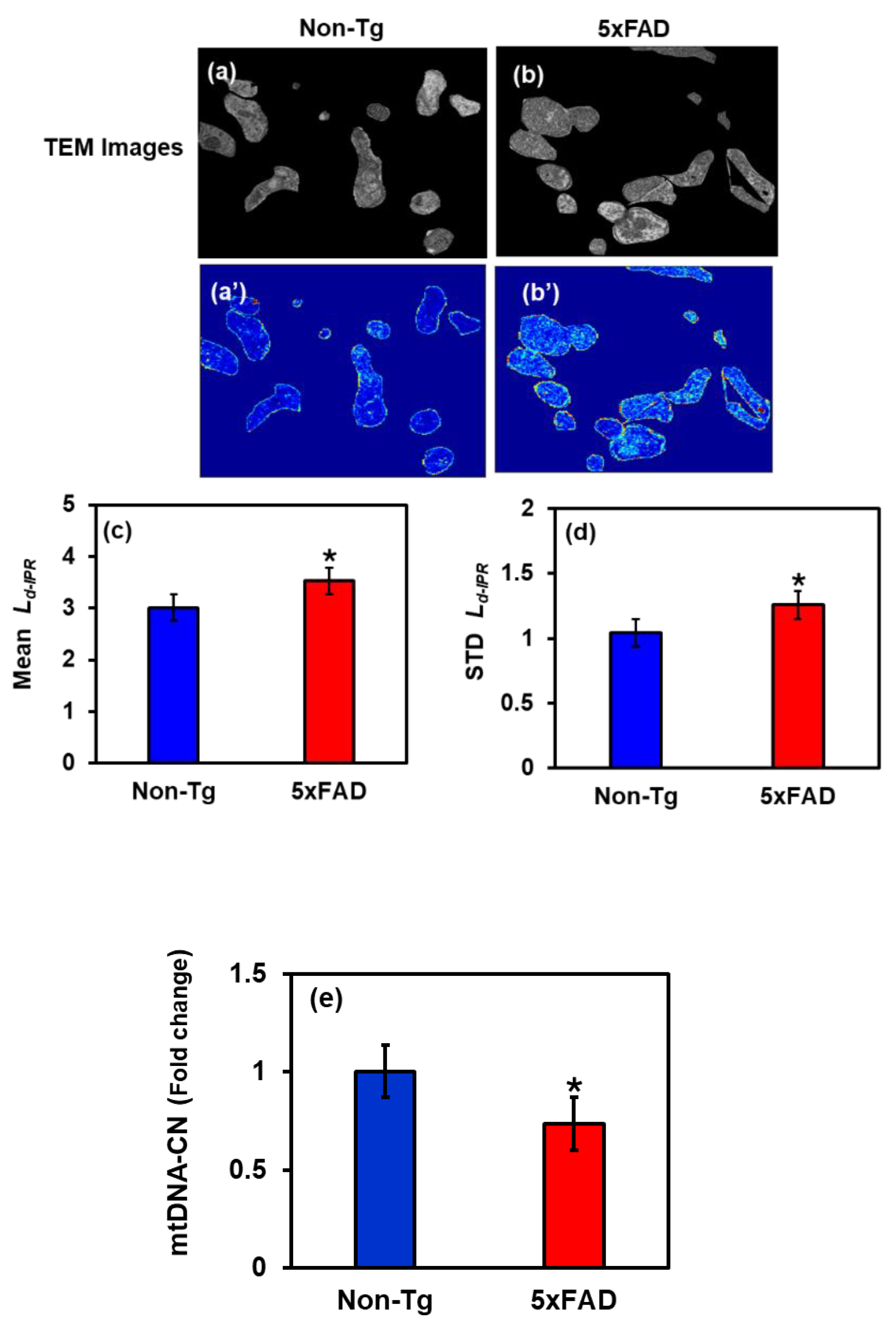

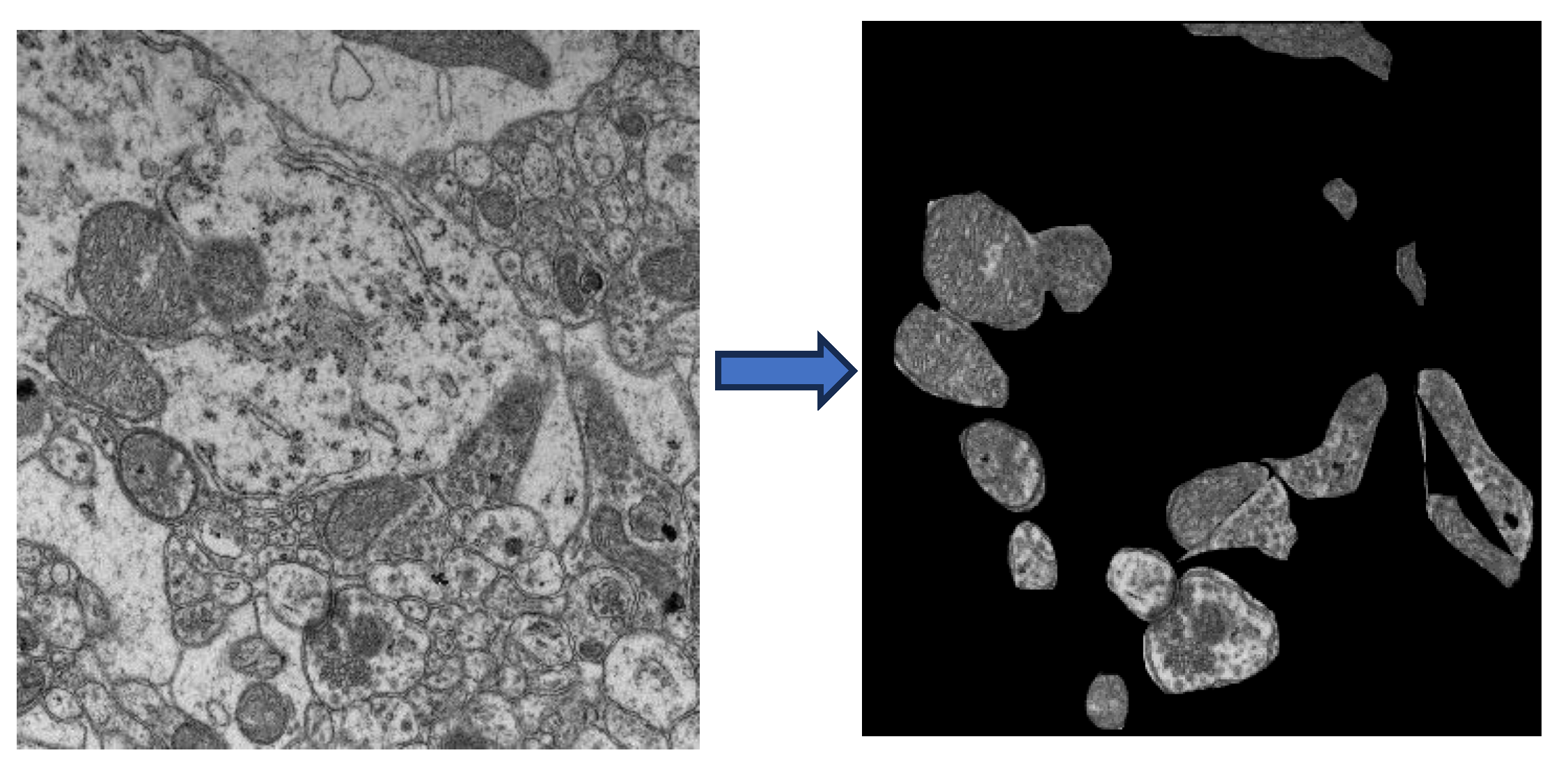

2.3. Changes in Mitochondria Structure in 5xFAD Mice: TEM Study

2.4. Behavioral Study

2.4.1. Microglial Activation and Aβ Accumulation in the Brain of 5xFAD Mice

2.5. Mitochondrial DNA Analysis: Relative mtDNA

| Primer | Sequence (5’→3’) | Locus | Species | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mtDNA_mF1 | cagaaacaaaccgggccc | NC_005089.1 3322 - 3339 | Mouse | |

| mtDNA_mR1 | gccggctgcgtattctac | NC_005089.1 3404 - 3387 | Mouse | 83 (with mtDNA_mF1) |

| nDNA_mF1 | ccagggagagctagtatctagg | NC_000072 122150920 - 0941 | Mouse | |

| nDNA_mR1 | ctggtcatgggagaaaaggc | NC_000072 122151095 - 1076 | Mouse | 176 (with nDNA_mF1) |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Partial Wave Spectroscopy Experiment

4.1.1. Optical Setup

4.1.2. Measurement of Structural Disorder Strength

4.1.3. Sample Preparation for PWS Experiment

4.2. Inverse Participation Ratio Quantification using Confocal Microscopy and Transmission Electron Microscopy

4.2.1. Confocal Imaging

4.2.2. Measurement of IPR

4.2.3. Sample Preparation for IPR Experiment

4.2.4. TEM Imaging of Mitochondria

4.2.5. IPR Quantification using TEM Images

4.3. Novel Object Recognition

4.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

4.5. Quantification for Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| PWS | Partial Wave Spectroscopy |

| IPR | Inverse Participation Ratio |

| Aβ | Amyloid beta |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| Non-Tg | Non-transgenic |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| NOR | Novel Object Recognition |

| RI | Refractive Index |

References

- Bush, A.I. The Metallobiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends in Neurosciences 2003, 26, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2025 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2025, 21, e70235. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P.; LeVine, H. Alzheimer’s Disease and the β-Amyloid Peptide. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 19, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, C.L.; Mori, H.; Selkoe, D.J. Amyloid β-Protein Deposition in Tissues Other than Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 1989, 341, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, C.L.; Bateman, R.; Blennow, K.; Rowe, C.C.; Sperling, R.A.; Cummings, J.L. Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Hyman, B.T. Neuropathological Alterations in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2011, 1, a006189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thal, D.R.; Rüb, U.; Orantes, M.; Braak, H. Phases of A Beta-Deposition in the Human Brain and Its Relevance for the Development of AD. Neurology 2002, 58, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Damania, D.; Joshi, H.M.; Turzhitsky, V.; Subramanian, H.; Roy, H.K.; Taflove, A.; Dravid, V.P.; Backman, V. Quantification of Nanoscale Density Fluctuations by Electron Microscopy: Probing Cellular Alterations in Early Carcinogenesis. Phys Biol 2011, 8, 026012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drayer, B.P.; Heyman, A.; Wilkinson, W.; Barrett, L.; Weinberg, T. Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: An Analysis of CT Findings. Annals of Neurology 1985, 17, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, A.K.; Valentine, M.T.; Kaplan, P.D.; Weitz, D.A. Microscopic Origin of Light Scattering in Tissue. Appl. Opt., AO 2003, 42, 2871–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boustany, N.N.; Thakor, N.V. Light Scatter Spectroscopy and Imaging of Cellular and Subcellular Events. Biomedical Photonics: Handbook 2003, 16–16. [Google Scholar]

- Drezek, R.; Dunn, A.; Richards-Kortum, R. Light Scattering from Cells: Finite-Difference Time-Domain Simulations and Goniometric Measurements. Appl. Opt. AO 1999, 38, 3651–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.; Alharthi, F.; Pradhan, P. Partial Wave Spectroscopy Detection of Cancer Stages Using Tissue Microarrays (TMA) Samples. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Optics + Laser Science APS/DLS (2019), paper JW4A.89; Optica Publishing Group, 15 September 2019; p. JW4A.89.

- Adhikari, P.; Hasan, M.; Sridhar, V.; Roy, D.; Pradhan, P. Studying Nanoscale Structural Alterations in Cancer Cells to Evaluate Ovarian Cancer Drug Treatment, Using Transmission Electron Microscopy Imaging. Phys. Biol. 2020, 17, 036005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharthi, F.; Apachigawo, I.; Solanki, D.; Khan, S.; Singh, H.; Khan, M.M.; Pradhan, P. Dual Photonics Probing of Nano- to Submicron-Scale Structural Alterations in Human Brain Tissues/Cells and Chromatin/DNA with the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 12211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.Y.; Chin, L.K.; Ser, W.; Chen, H.F.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Lee, C.-H.; Sung, K.-B.; Ayi, T.C.; Yap, P.H.; Liedberg, B.; et al. Cell Refractive Index for Cell Biology and Disease Diagnosis: Past, Present and Future. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladstein, S.; Damania, D.; Almassalha, L.M.; Smith, L.T.; Gupta, V.; Subramanian, H.; Rex, D.K.; Roy, H.K.; Backman, V. Correlating Colorectal Cancer Risk with Field Carcinogenesis Progression Using Partial Wave Spectroscopic Microscopy. Cancer Medicine 2018, 7, 2109–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, V.; Roy, H.K. Light-Scattering Technologies for Field Carcinogenesis Detection: A Modality for Endoscopic Prescreening. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 35–41.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, H.; Pradhan, P.; Liu, Y.; Capoglu, I.R.; Li, X.; Rogers, J.D.; Heifetz, A.; Kunte, D.; Roy, H.K.; Taflove, A.; et al. Optical Methodology for Detecting Histologically Unapparent Nanoscale Consequences of Genetic Alterations in Biological Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 20118–20123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, E.; Wisniewski, T. Alzheimer’s Disease: Experimental Models and Reality. Acta Neuropathol 2017, 133, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Genetically Modified Mouse Model Mimics Multiple Aspects of Human Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/new-genetically-modified-mouse-model-mimics-multiple-aspects-human-alzheimers-disease (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Hoekstra, J.G.; Hipp, M.J.; Montine, T.J.; Kennedy, S.R. Mitochondrial DNA Mutations Increase in Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease and Are Inconsistent with Oxidative Damage. Ann Neurol 2016, 80, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondrial DNA–Related Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002, 126, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsering, W.; Prokop, S. Neuritic Plaques - Gateways to Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2024, 61, 2808–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazestani, V.; Kamath, T.; Nadaf, N.M.; Dougalis, A.; Burris, S.J.; Rooney, B.; Junkkari, A.; Vanderburg, C.; Pelkonen, A.; Gomez-Budia, M.; et al. Early Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in Human Cortex Involves Transient Cell States. Cell 2023, 186, 4438–4453.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobro-Flatmoen, A.; Lagartos-Donate, M.J.; Aman, Y.; Edison, P.; Witter, M.P.; Fang, E.F. Re-Emphasizing Early Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology Starting in Select Entorhinal Neurons, with a Special Focus on Mitophagy. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 67, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thadathil, N.; Delotterie, D.F.; Xiao, J.; Hori, R.; McDonald, M.P.; Khan, M.M. DNA Double-Strand Break Accumulation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence from Experimental Models and Postmortem Human Brains. Mol Neurobiol 2021, 58, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Gunewardena, S.; Haeri, M.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Wang, N. Landscape of Double-Stranded DNA Breaks in Postmortem Brains from Alzheimer’s Disease and Non-Demented Individuals. J Alzheimers Dis 2023, 94, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dileep, V.; Boix, C.A.; Mathys, H.; Marco, A.; Welch, G.M.; Meharena, H.S.; Loon, A.; Jeloka, R.; Peng, Z.; Bennett, D.A.; et al. Neuronal DNA Double-Strand Breaks Lead to Genome Structural Variations and 3D Genome Disruption in Neurodegeneration. Cell 2023, 186, 4404–4421.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengel-From, J.; Thinggaard, M.; Dalgård, C.; Kyvik, K.O.; Christensen, K.; Christiansen, L. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Peripheral Blood Cells Declines with Age and Is Associated with General Health among Elderly. Hum Genet 2014, 133, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filograna, R.; Mennuni, M.; Alsina, D.; Larsson, N.-G. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Human Disease: The More the Better? FEBS Lett 2021, 595, 976–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerantonio, A.; Citrigno, L.; Greco, B.M.; De Benedittis, S.; Passarino, G.; Maletta, R.; Qualtieri, A.; Montesanto, A.; Spadafora, P.; Cavalcanti, F. The Role of Mitochondrial Copy Number in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Present Insights and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, C.A.; Longchamps, R.J.; Sun, J.; Guallar, E.; Arking, D.E. Thinking Outside the Nucleus: Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Health and Disease. Mitochondrion 2020, 53, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, M.C.B.; Kanaan, S.; Geller, M.; Praticò, D.; Daher, J.P.L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Res Rev 2025, 107, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Ortiz, J.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role in Pathogenesis and Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 3489–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harerimana, N.V.; Paliwali, D.; Romero-Molina, C.; Bennett, D.A.; Pa, J.; Goate, A.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Andrews, S.J. The Role of Mitochondrial Genome Abundance in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wiggins, K.L.; Kurniansyah, N.; Guo, X.; Rodrigue, A.L.; Zhao, W.; Yanek, L.R.; Ratliff, S.M.; Pitsillides, A.; et al. Association of Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number With Brain MRI Markers and Cognitive Function: A Meta-Analysis of Community-Based Cohorts. Neurology 2023, 100, e1930–e1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kim, H.-A.; Han, Y.S.; Jeon, W.K.; Han, J.-S. Recognition Memory Impairments and Amyloid-Beta Deposition of the Retrosplenial Cortex at the Early Stage of 5XFAD Mice. Physiol Behav 2020, 222, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pádua, M.S.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Lopes, P.A. Behaviour Hallmarks in Alzheimer’s Disease 5xFAD Mouse Model. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, H.; Cole, S.L.; Logan, S.; Maus, E.; Shao, P.; Craft, J.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.; Ohno, M.; Disterhoft, J.; Van Eldik, L.; et al. Intraneuronal Beta-Amyloid Aggregates, Neurodegeneration, and Neuron Loss in Transgenic Mice with Five Familial Alzheimer’s Disease Mutations: Potential Factors in Amyloid Plaque Formation. J Neurosci 2006, 26, 10129–10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanism and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, L.; Paolicelli, R.C. Microglia-Mediated Synapse Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurosci 2018, 38, 2911–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Das, A.; Ray, S.K.; Banik, N.L. Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Released from Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Brain Res Bull 2012, 87, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Bueno, R.; de la Cruz Ruiz, P.; Artal-Sanz, M.; Askjaer, P.; Dobrzynska, A. Nuclear Organization in Stress and Aging. Cells 2019, 8, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, B.R.; Comaills, V. Nuclear Envelope Integrity in Health and Disease: Consequences on Genome Instability and Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.K.; Delotterie, D.F.; Xiao, J.; Pierre, J.F.; Rao, R.; McDonald, M.P.; Khan, M.M. Alterations in the Gut-Microbial-Inflammasome-Brain Axis in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Shukla, P.; Almabadi, H.; Sahay, P.; Rao, R.; Pradhan, P. Optical Study of Stress Hormone-Induced Nanoscale Structural Alteration in Brain Using Partial Wave Spectroscopic (PWS) Microscopy. 10.

- Pradhan, P.; Subramanian, H.; Liu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Roy, H.; Backman, V. Application of Mesoscopic Light Transport Theory to Ultra-Early Detection of Cancer in a Single Biological Cell. 2007, B41.013.

- Pradhan, P. Phase Statistics of Light Wave Reflected from One-Dimensional Optical Disordered Media and Its Effects on Light Transport Properties. 18.

- Pradhan, P.; Liu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Li, X.; Wali, R.K.; Roy, H.K.; Backman, V. Mesoscopic Light Transport Properties of a Single Biological Cell : Early Detection of Cancer. 2006, Q1.326.

- Pradhan, P.; Subramanian, H.; Damania, D.; Roy, H.; Backman, V. Mesoscopic Light Reflection Spectroscopy of Weakly Disordered Dielectric Media: Nanoscopic to Mesoscopic Light Transport Properties of a Single Biological Cell and Ultra-Early Detection of Cancer. 2009, A28.001.

- Pradhan, P.; Kumar, N. Localization of Light in Coherently Amplifying Random Media. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 9644–9647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.K.; Subramanian, H.; Damania, D.; Hensing, T.A.; Rom, W.N.; Pass, H.I.; Ray, D.; Rogers, J.D.; Bogojevic, A.; Shah, M.; et al. Optical Detection of Buccal Epithelial Nanoarchitectural Alterations in Patients Harboring Lung Cancer: Implications for Screening. Cancer Research 2010, 70, 7748–7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, H.; Pradhan, P.; Kunte, D.; Deep, N.; Roy, H.; Backman, V. Single-Cell Partial Wave Spectroscopic Microscopy. In Proceedings of the Biomedical Optics (2008), March 16 2008; p. BTuC5., paper BTuC5; Optica Publishing Group.

- Pradhan, P.; Damania, D.; Joshi, H.M.; Turzhitsky, V.; Subramanian, H.; Roy, H.K.; Taflove, A.; Dravid, V.P.; Backman, V. Quantification of Nanoscale Density Fluctuations Using Electron Microscopy: Light-Localization Properties of Biological Cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 243704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.A.; Fisher, D.S. Anderson Localization in Two Dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1981, 47, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafi, A. Transverse Anderson Localization of Light: A Tutorial. Adv. Opt. Photon., AOP 2015, 7, 459–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.; Shukla, P.K.; Rao, R.; Pradhan, P. Quantification of Light Localization Properties to Study the Effect of Probiotic on Chronic Alcoholic Brain Cells via Confocal Imaging. In Proceedings of the Imaging, Manipulation, and Analysis of Biomolecules, Cells, and Tissues XIX; Leary, J.F., Tarnok, A., Georgakoudi, I., Eds.; SPIE: Online Only, United States, March 5, 2021; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.; Khan, S.; Xiao, J.; Nguyen, N.; Das, A.; Johnson, D.; Fang-Liao, F.; Frautschy, S.A.; McDonald, M.P.; Pourmotabbed, T.; et al. Harnessing cGAS-STING Signaling to Counteract the Genotoxic-Immune Nexus in Tauopathy. bioRxiv, 6789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueptow, L.M. Novel Object Recognition Test for the Investigation of Learning and Memory in Mice. J Vis Exp 2017, 55718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, X. Behavioral and Pathological Characteristics of 5xFAD Female Mice in the Early Stage. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Delotterie, D.F.; Xiao, J.; Thangavel, R.; Hori, R.; Koprich, J.; Alway, S.E.; McDonald, M.P.; Khan, M.M. Crosstalk between DNA Damage and cGAS-STING Immune Pathway Drives Neuroinflammation and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Behav Immun 2025, 130, 106065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).