1. Introduction

In complex socio-individual systems, many key phenomena of interest do not arise from isolated shifts within a single dimension but instead emerge from interactions and trade-offs among multiple domains—such as occupational development, health status, and social relationships—whose joint dynamics precipitate consequential events [

1,

2,

3]. For example, rapid occupational advancement often coincides with short-term compromises in health or social engagement, as limited personal resources require sustaining gains in one dimension at the expense of stability in others [

1,

3,

4]. Likewise, sudden deterioration in health may result from the accumulated impact of occupational strain or shifts in social structure, where multiple factors reinforce one another along causal chains, ultimately destabilizing the overall system [

4,

5,

6]. In mainstream machine-learning practice, researchers frequently operationalize such events through heuristic probability thresholds or rule-based annotations. However, these formulations tend to be ambiguous and noisy, largely because they obscure the intrinsically cross-dimensional nature of the phenomena, thereby rendering tasks weakly learnable and producing misleading performance metrics—for instance, when models capture superficial correlations rather than meaningful causal structure [

5,

7,

8].

To address this issue, the present study adopts the position that problem definition takes precedence over model complexity. We begin by reconstructing “career events” and “health events” as data-driven “statistical anomaly events” [

9,

10,

11]. Concretely, anomalies are defined as single-step deviations from mean trajectories that exceed a specified threshold—e.g., ±1.5 standard deviations—derived from temporal-difference measures. This approach introduces explicit detection criteria, clarifying task signals and enabling quantifiable thresholds; thus models can learn more stable feature patterns while avoiding ambiguities inherent in traditional labels [

9,

11,

12]. Building on this refinement, we introduce a composite event that more authentically reflects multidimensional interaction: the “trade-off crisis,” defined as the near co-occurrence of a career breakthrough and a health downturn within a proximate temporal window [

1,

2,

5]. This construct emphasizes co-occurrence and mutual displacement—properties that cannot be inferred adequately from any single dimension alone (for instance, when occupational acceleration directly depletes health-related resources). It therefore provides an empirical setting to evaluate “entanglement-type” models. The underlying rationale is that without explicitly identifying such interactions, models are unlikely to capture the causal interdependence embedded in the system; hence, the composite formulation sharpens the analytical target and centers the modeling process on intrinsically coupled dimensions [

5,

6].

Furthermore, the study draws on Bazi metaphysics and the generative–restraining dynamics of the Five Elements as a conceptual framework for representing directed relationships across feature dimensions, offering structural heuristics for composite-event modeling [

13]. In parallel, we invoke the notion of quantum entanglement to illustrate cross-dimensional dependence and inseparability [

14,

15]. It is important to clarify that neither Bazi nor quantum theory is deployed as statistical evidence, which would risk pseudoscientific misinterpretation, but rather as conceptual prototypes that inform engineering choices: first, by guiding the identification of learnable composite events (via a relational framework of interacting dimensions), and second, by clarifying conditions under which complex models are warranted (namely, when events exhibit entanglement-like inseparability) [

7,

12,

16]. The reasoning is as follows: traditional models remain efficient for single-dimension patterns but fail when events arise from multi-dimensional coupling. These prototypes help bridge the gap between problem definition and model selection, supporting the design of more robust systems [

8,

12,

17].

Based on the above background, this study proposes a novel multi-task learning framework named the Metaphysics-Temporal Entanglement-Fusion Network (MTEN-Transformer). The core ideas are: 1) constructing a synthetic life-trajectory dataset in which the occurrence probabilities of individual life events are jointly influenced by static Five-Elements attributes representing “innate endowment” and dynamic temporal events representing “acquired experience”; 2) designing a Transformer-based deep learning model centered on an Entanglement-Fusion Module that effectively captures and integrates complex interactions between static “innate” features and dynamic “acquired” sequences; and 3) conducting multi-task learning on the synthetic dataset (e.g., predicting “health crises” and “trade-off crises”) to systematically evaluate the performance advantages of the MTEN-Transformer relative to baseline models.

2. Theoretical Foundations

This section outlines two forms of “structured worldviews” that offer conceptual guidance for the present study: first, the directed relational framework represented by Bazi metaphysics and the generative–restrictive dynamics of the Five Elements; and second, the notion of inseparability and correlated states as illustrated by quantum entanglement. Neither framework serves as statistical evidence. Instead, both operate as conceptual and engineering heuristics that inform the construction of composite events, model-selection strategies, and the criteria used for evaluation.

2.1. Bazi Metaphysics and the Generative–Restrictive Dynamics of the Five Elements

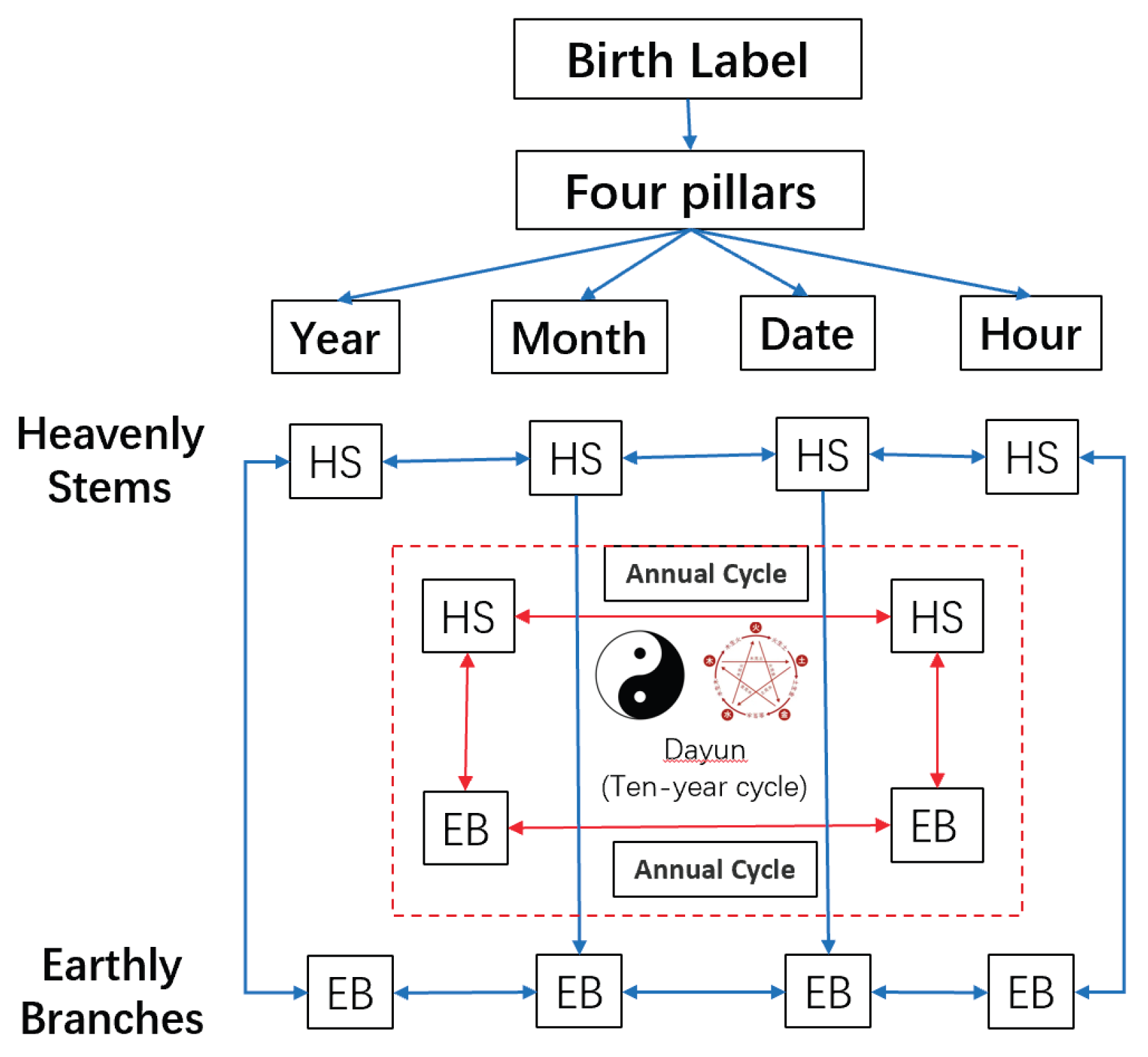

Bazi conceptualizes an individual’s internal “entanglement structure” through the stems and branches of the year, month, day, and hour, while the Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water) are linked by well-defined generative (reinforcing) and restrictive (inhibiting) relationships [

18,

19]. This framework can be abstracted into an interaction graph of multidimensional features: each dimension (node) is connected by signed, directed edges indicating the direction and magnitude of influence, forming a structural prior that can be readily mapped into machine-learning contexts. Classical texts in the tradition provide both structural inspiration and a symbolic system for organizing these relations [

20,

21]. See

Figure 1.

Within data modeling, contemporary domains such as “career,” “health,” and “social relations” can be conceptualized as “functional elements,” emphasizing their structural interdependence rather than treating them as isolated variables. The causal intuition is that sustained reinforcement in one dimension (analogous to “generation”) may transmit pressure or consume resources in ways that suppress other dimensions (analogous to “restriction”), thereby producing co-occurring gains and losses within a similar temporal window. This causal chain offers the definitional foundation for composite events—such as the “trade-off crisis”—and guides feature engineering: statistical anomalies make abrupt transitions explicit, whereas relational priors constrain feature interactions and model inductive biases [

22,

23].

A key conceptual boundary must be emphasized: while the Five Elements framework provides interpretive and structural advantages, its symbolic system must remain decoupled from formal statistical claims. From an engineering standpoint, such priors can be encoded through graph-based models or shared-representation structures in multi-task learning, with their validity evaluated through reproducible experiments rather than assumed through traditional terminology [

24].

2.2. Insights from Quantum Entanglement

Quantum entanglement describes the inseparability of subsystem states within a composite system: the global state cannot be factorized into a product of individual subsystem states, and measurement on one part alters the conditional distribution of the other—not through causal signal transmission, but through non-classical statistical correlation [

25,

26]. The key implication for the present context is that when event-generation mechanisms rely on strong cross-dimensional dependencies and conditional relations, single-dimensional observation becomes insufficient to reconstruct the underlying generative process [

27,

28].

In machine learning, such inseparability motivates the use of models that incorporate shared representations, task coupling, and structural regularization across learning objectives—such as multi-task architectures, graph-based models, and approaches to causal-structure learning. These models capture cross-dimensional co-occurrence and the internal logic of sacrifice and trade-off [

29]. The engineering strategy proceeds as follows: first, reduce noise through precise event definition (based on statistical thresholds and temporal windows); second, strengthen cross-dimensional generalization through shared representations and relational constraints; and third, evaluate the performance gain of “entanglement-type” models relative to baselines using rigorous metrics and ablation analyses [

30].

A parallel conceptual boundary applies here: the notion of quantum entanglement functions as an analogy for inseparable relational structures and should not be misinterpreted as a direct application of quantum theory to socio-individual data. Its value lies in offering intuition and methodological guidance regarding why joint modeling across dimensions is necessary [

31,

32].

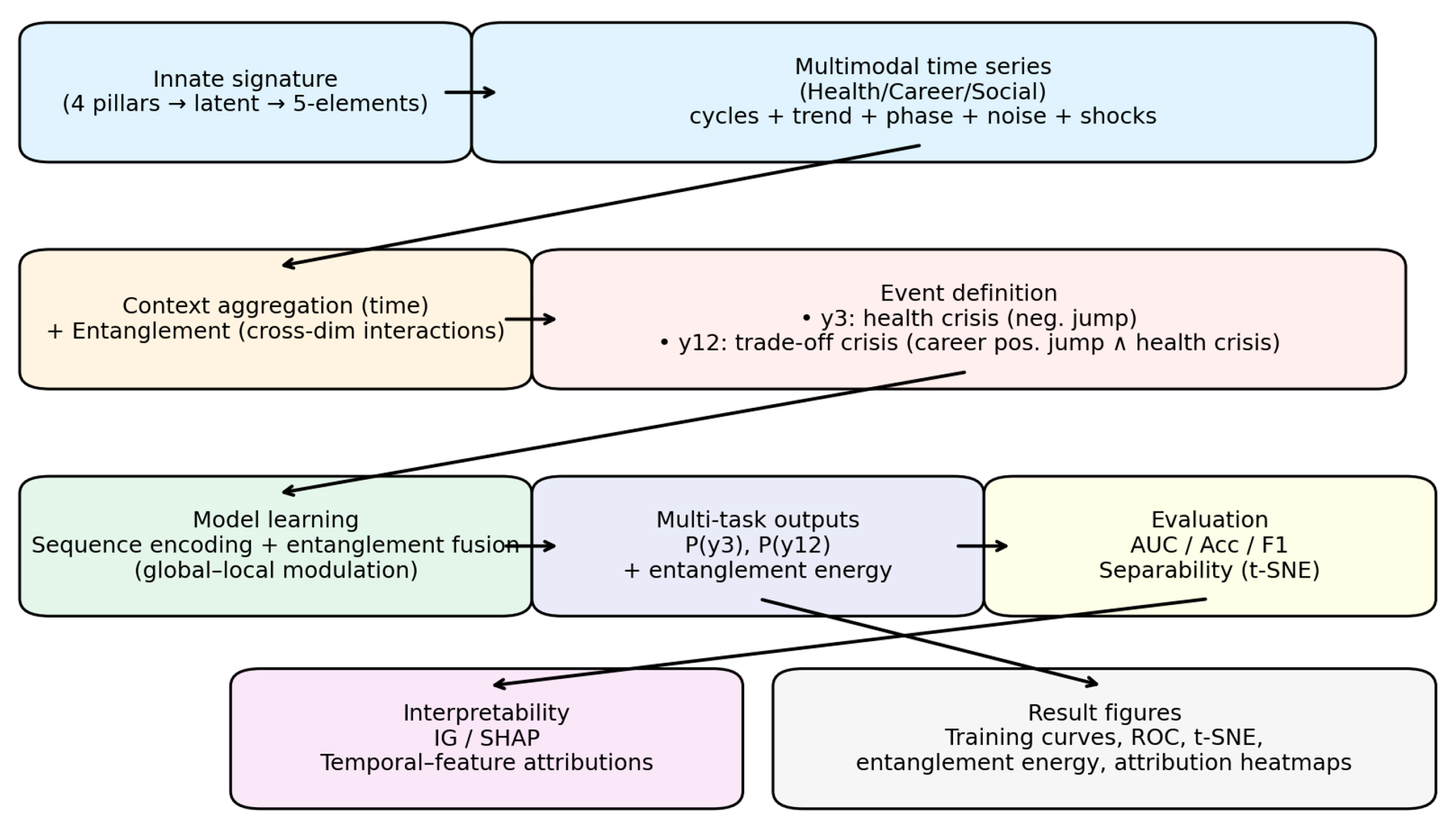

3. Methodological Principles and Computational Logic

This study implements an end-to-end pipeline for multimodal temporal data, integrating two model families (the entanglement-type MTEN and a Transformer baseline), data generation, event definition, model learning, evaluation, and interpretation. The central idea follows a “birth-signature—contextual trajectory—event activation” chain. Through entanglement-style (cross-dimensional interaction) representation learning, the method characterizes health, occupational, and social trajectories and their coupled effects on event generation. See

Figure 2.

3.1. Data Generation

(1) Individual latent signature: Each individual receives a latent vector derived from the four-pillar categories; a linear random projection maps this vector into a set of numerical representations analogous to the Five Elements, serving as global personal-level information.

(2) Multimodal time series: For each individual, three monthly trajectories—health, occupation, and social relations—are generated. Monthly values combine periodic components, slow trends, life-stage effects, and noise, with occasional low-frequency shocks introduced to simulate real-world fluctuations.

(3) Context aggregation and interaction: The three modalities are aggregated over time (e.g., via averaging) to obtain global health, occupational, and social contexts. These aggregates are jointly transformed with the birth signature through nonlinear mappings, and cross-modal multiplication followed by compression produces “entanglement terms,” which reflect the strength of inter-dimensional interactions. A nonlinear function then transforms these terms into risk measures to shape data distribution.

3.2. Event Definition

(1) Single-dimensional event (Health Crisis, y3): Using adjacent differences in the monthly health trajectory, we define crises by thresholding statistically significant negative jumps—such as deviations below the mean by multiple standard deviations—representing sudden declines in short temporal windows.

(2) Composite event (Trade-off Crisis, y12): A composite event is triggered when a significant positive jump in the occupational trajectory (exceeding the mean by multiple standard deviations) co-occurs with a health crisis within a proximate time window. This captures the cross-dimensional pattern of “breakthrough accompanied by cost.”

(3) Notes: Risk probabilities and entanglement terms shape the generative mechanism and distribution; event labels are constructed via rule-based statistical thresholds to assess whether models can infer triggering structures from multimodal and global information.

3.3. Model Design

(1) Sequence encoding: The three modalities are concatenated along the feature dimension, projected linearly, supplemented with positional encodings, and processed by a sequential encoder (such as a multi-layer self-attention architecture) to capture temporal dependency and cross-feature relationships.

(2) Entanglement fusion: Global personal information (birth signature and Five-Element values) is fused with sequence representations via a low-rank transformation and reintroduced through residual connections. This yields a coupled “global–local” modulation that strengthens cross-dimensional interactions.

(3) Multi-task outputs: Shared lower-layer representations feed two task-specific output heads predicting the probabilities of a health crisis (y3) and a trade-off crisis (y12). Fusion-output energy is recorded as an indicator of entanglement strength.

3.4. Training Procedure

(1) Objective function: The joint loss sums binary cross-entropies for both tasks, balancing the learning of single-dimensional and composite events.

(2) Data splits: Data are partitioned into training, validation, and test sets. During training, loss and validation metrics are monitored to assess convergence and early performance.

(3) Optimization: Appropriate optimizers and regularization techniques (e.g., weight decay, dropout) regulate model capacity and generalization. Batch sizes, learning rates, and training epochs are tuned according to computational resources and performance needs.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

(1)

Binary classification metrics: AUC, accuracy, and F1-scores for both tasks are computed on the test set to assess ranking quality and classification performance [

33].

(2) Representation quality: Pooled sequence embeddings are analyzed for separability and structural alignment with event labels.

(3) Entanglement energy: Energy distributions of fusion outputs are evaluated for their correlation with and discriminatory power over event occurrences.

3.6. Visualization and Interpretation

(1) Training and performance curves: Loss curves and validation AUC trends across epochs illustrate convergence and generalization. ROC curves are reported for both tasks.

(2) Representation-space projection: Two-dimensional projections (e.g., t-SNE) of pooled embeddings, color-coded by event labels, reveal distribution patterns and separability.

(3) Attribution analysis (Integrated Gradients/SHAP): Attributions for the Five-Element vectors and multimodal time series are computed, producing temporal–feature heatmaps and bar plots showing average contributions and temporal sensitivities. Separate interpretations are provided for y3 and y12.

3.7. Interpretation of Results

(1) Entanglement advantage: Models incorporating entanglement fusion gain stronger expressive power in integrating multimodal and global information, leading to superior ranking and classification performance in both tasks.

(2) Improved separability: Representation spaces generated by the entanglement model exhibit clearer clustering and greater distance between event and non-event samples.

(3) Mechanistic alignment: Attribution analyses show that event activation is typically shaped by interactions between specific temporal signals in health or occupation and individual latent signatures. Composite events display cross-dimensional reinforcement and constraint.

(4) Robustness and interpretability: Two interpretability methods produce consistent feature-importance rankings, enhancing model transparency. The observed relation between entanglement-energy distributions and event labels supports the design hypotheses.

3.8. Implementation and Reproducibility

(1) Reproducibility: Fixed random seeds and stable optimization settings ensure replication. Training logs and evaluation results are fully recorded.

(2) Publication-ready outputs: The pipeline produces publication-quality visualizations: training histories, ROC curves, representation projections, entanglement-energy distributions, attribution heatmaps, and Five-Element contribution plots.

(3) General applicability: The approach does not depend on any domain-specific dataset and can serve as a general experimental framework for complex socio-individual systems, integrating event construction, model representation, and interpretability analyses.

3.9. Environment and Execution

(1) Environment: Experiments were conducted on Windows 11 using Python 3.13, scikit-learn 1.5 (baseline), and PyTorch 2.x (MTEN).

(2) Execution: Models can be run on any Python-supported platform via commands such as: python mten_main.py.All visual outputs are saved locally in the results directory.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.1.1. Main Findings

Using our custom Python implementation with training settings of epochs = 18 and 10000 individual samples, while keeping all other hyperparameters at default values, we obtained the results summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1 demonstrates the core conclusion of this study: the precision of event definition and the alignment of model choice with problem structure jointly determine task success. For questions requiring recognition of gain–loss dynamics, such as trade-offs, an entanglement-based architecture like MTEN is necessary. For simpler tasks, baseline models are generally preferable; however, when the data environment is structurally complex, even simple tasks may break baseline assumptions and degrade performance.

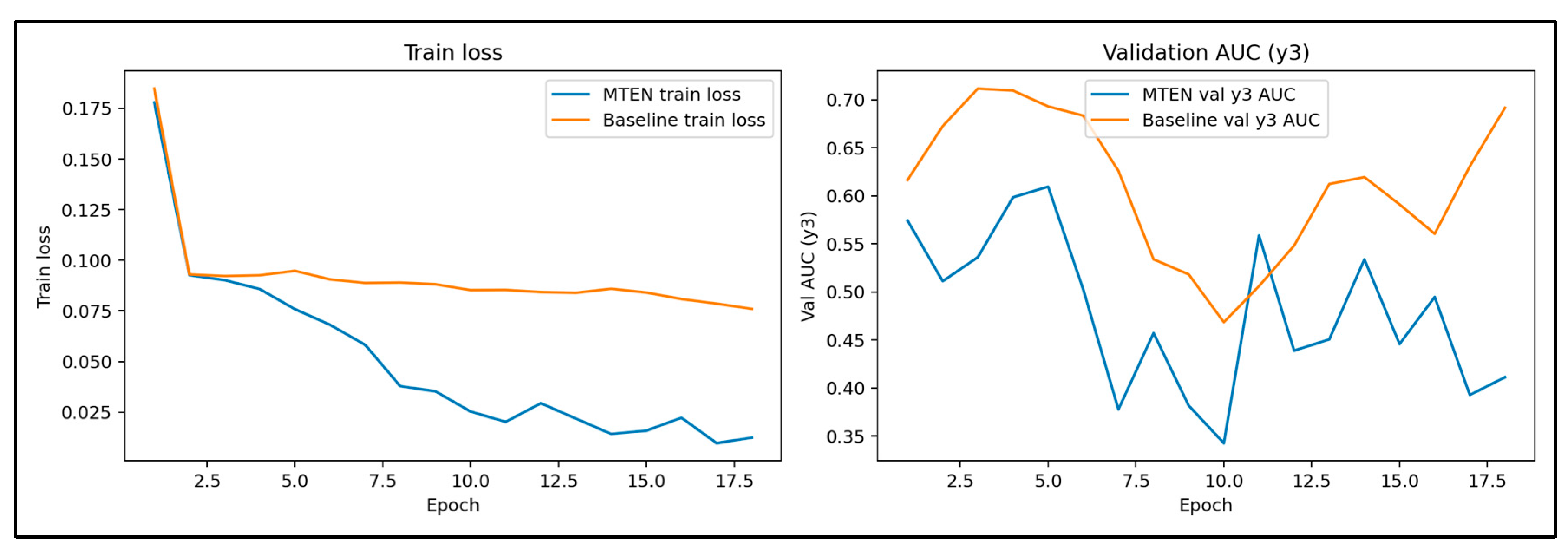

4.1.2. Training Loss and Validation AUC Curves

Figure 3 presents two line charts comparing the training dynamics of MTEN and the Baseline model. MTEN exhibits faster loss reduction and stronger fitting capacity. However, its validation AUC is consistently inferior to the Baseline, suggesting weaker generalization.

Left (Train Loss): The x-axis denotes training epochs; the y-axis denotes training loss. The blue line (MTEN) shows a consistently decreasing loss trajectory, ending substantially lower than the orange Baseline curve, indicating better in-sample fitting.

Right (Validation AUC for y3): The Baseline model (orange) displays higher and more stable AUC throughout training, whereas MTEN exhibits unstable and generally lower validation performance. This divergence between training fit and validation performance suggests possible overfitting and warrants further experimental verification.

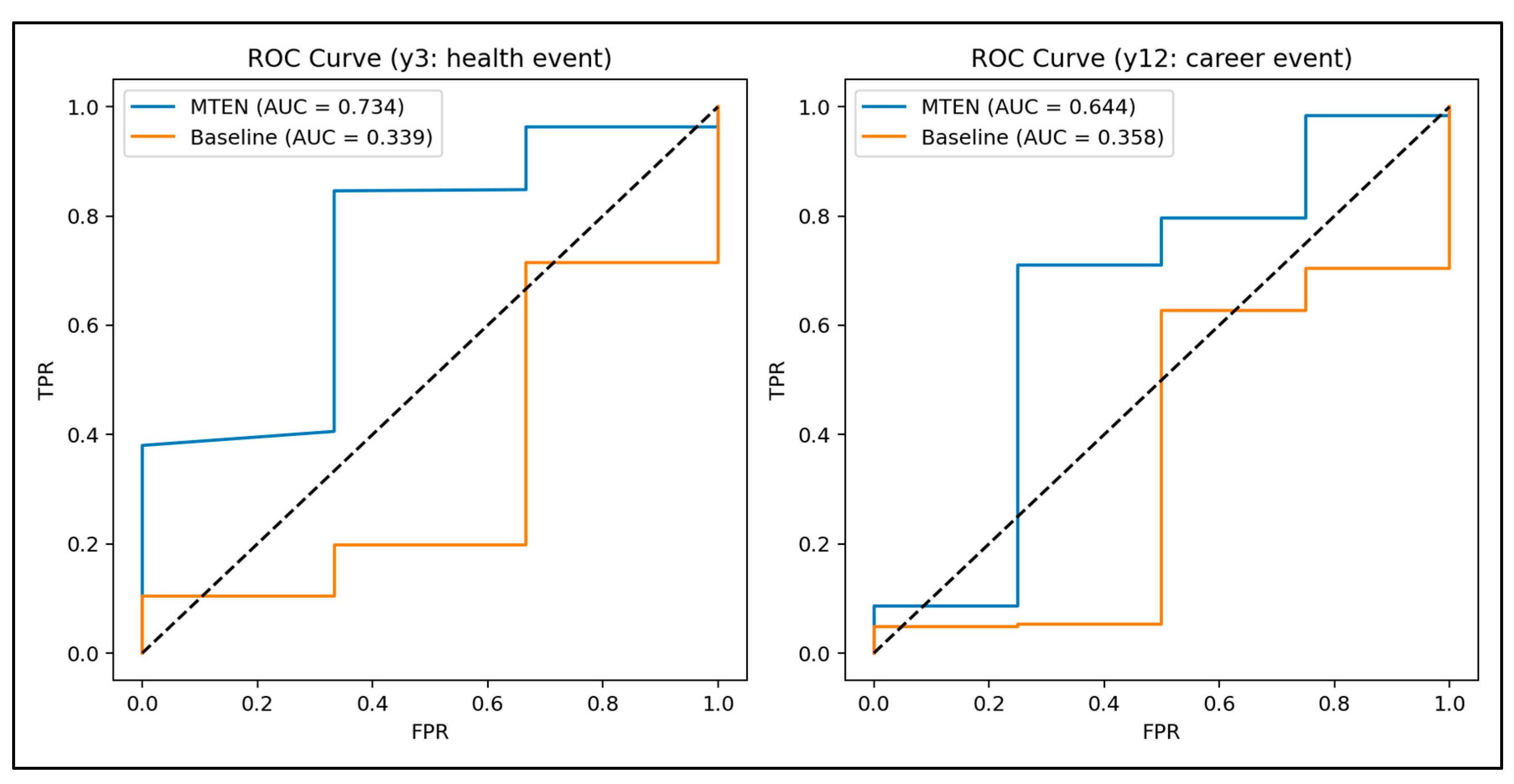

4.1.3. ROC Curve Comparison

Figure 4 compares ROC curves

for MTEN and the Baseline model across two predictive tasks. In both y3 and y12, MTEN clearly outperforms the Baseline. Because AUC values measure the ability to discriminate between positive and negative samples, scores below 0.5 indicate worse-than-random performance; the Baseline curves fall below this benchmark, while MTEN’s lie substantially above it.

Left Panel:MTEN’s ROC curve for predicting health events lies well above that of the Baseline, indicating superior discriminative power.

Right Panel:For occupational events, MTEN again surpasses the Baseline, though with a slightly smaller margin than in the health-event task.

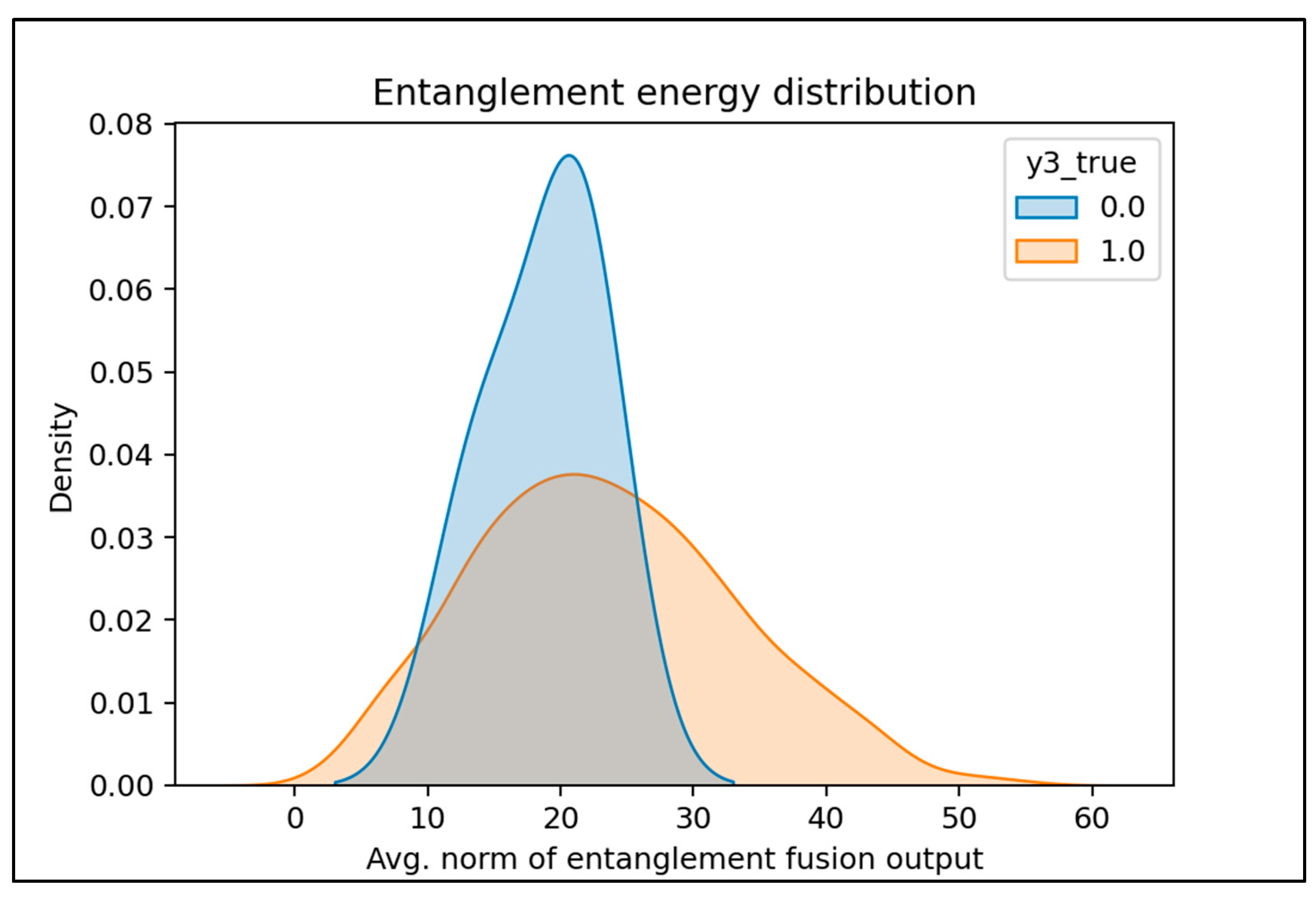

4.1.4. Entanglement-Energy Distribution Analysis

Figure 5 compares the distributions of entanglement-energy outputs across event classes. The results suggest that MTEN internalizes distinctive energy patterns associated with health events: positive samples tend toward higher entanglement-output norms, reflecting more intensive cross-feature interactions in the latent space.

The x-axis represents the average norm of the entanglement fusion output.

The y-axis represents density.

Negative samples (blue) display a concentrated distribution peaking between approximately 15–25. Positive samples (orange) exhibit a wider, flatter distribution shifted rightward, peaking near 25–35. This indicates that health-event occurrences (y3 = 1) tend to coincide with higher entanglement-energy outputs.

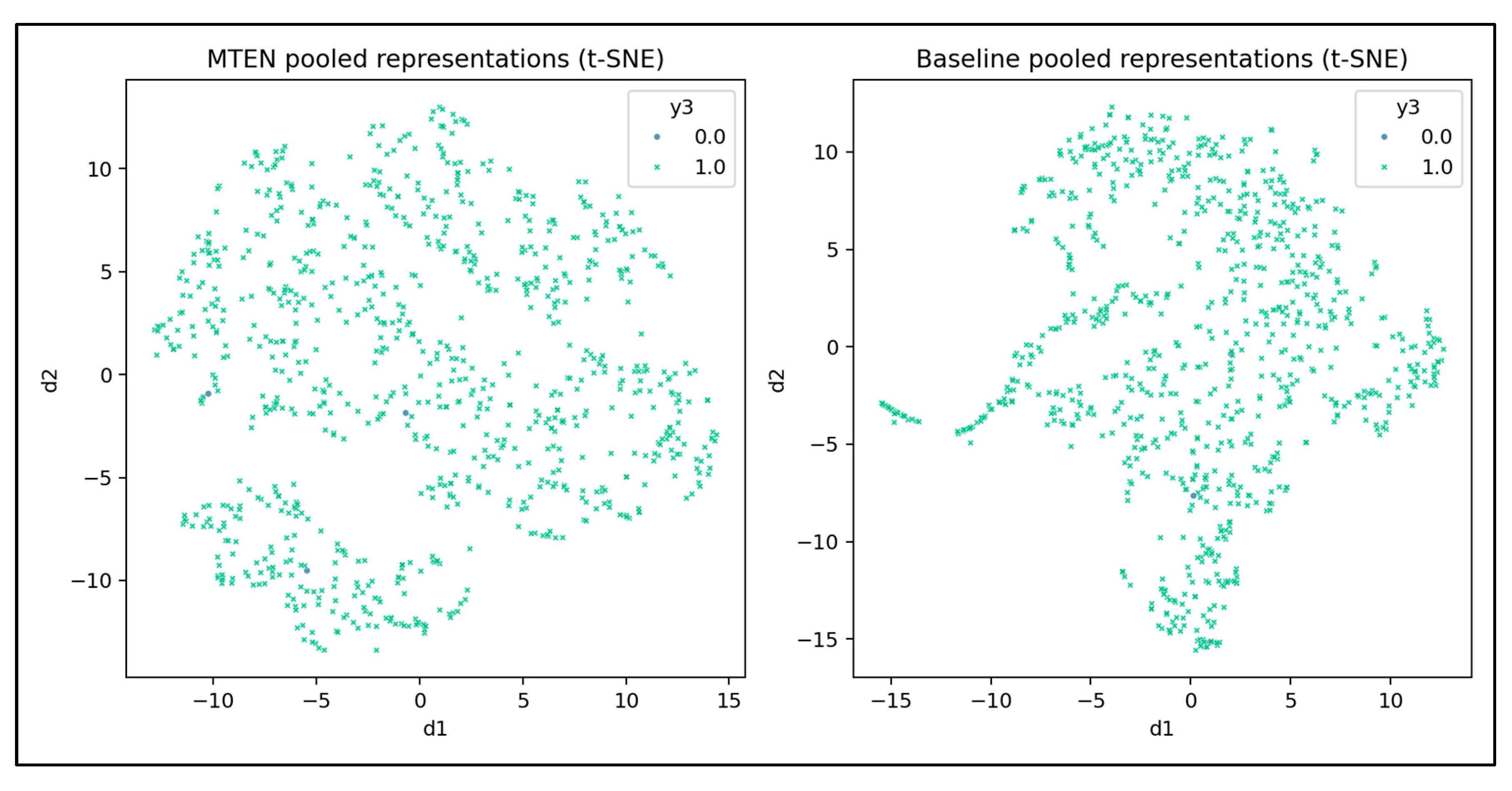

4.1.5. t-SNE Embedding Analysis

Figure 6 presents two t-SNE visualizations comparing the pooled representations from MTEN and the Baseline. The plots allow visual assessment of cluster structures and separability for y3.

The left panel (MTEN) shows dispersed clusters; negative samples (blue) are fewer and intermixed with positive samples.

The right panel (Baseline) displays a distribution with different density and spread, with negative samples nearly absent in the projected space.

These differences suggest that the two models generate distinct representation geometries, with MTEN yielding clearer class-conditional structure.

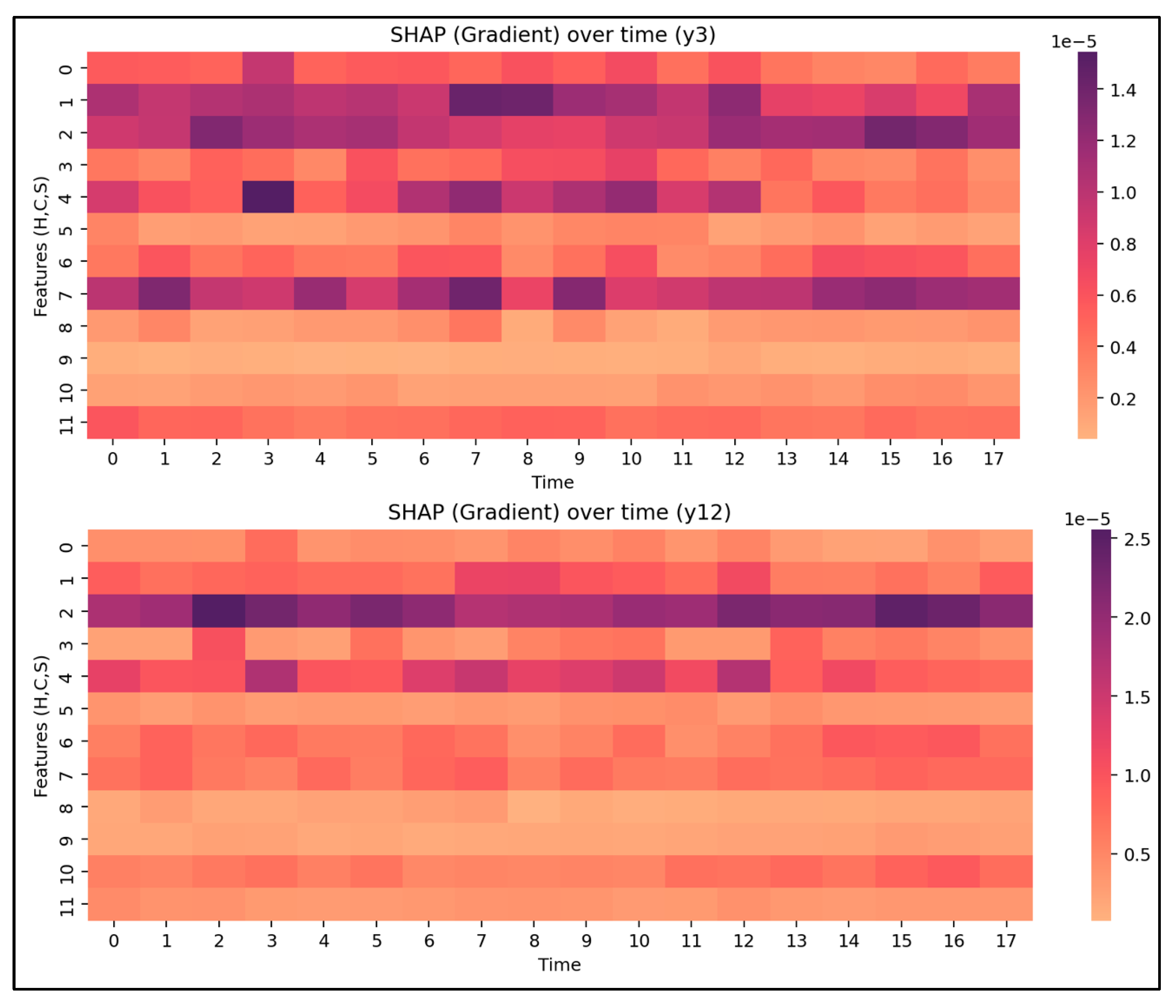

4.1.6. Attribution Analysis

Figure 7 presents average contributions and temporal sensitivities.

In the baseline model, y3 is primarily driven by the health sequence, with career and social acting as modulators. Birth-pillars (Bazi) information provides prior knowledge and shows a stable but secondary contribution. The y3 decision is most sensitive to recent changes in the health channel, while career and social add complementary signals; overall feature influence is phase-dependent and becomes stronger toward the latter part of the window.

In the MTEN model, SHAP results for y12 indicate that the career dimension is more important for medium- to long-term outcomes. Birth features still play a role for y12, but their total contribution is smaller than that of the sequence modalities. The joint influence of career and health highlights cross-modal synergy, with effects that accumulate over time.

4.2. Discussion

4.2.1. MTEN Excels in Modeling Trade-off Phenomena

For y12—the genuine entanglement-type event—MTEN achieves an AUC of 0.6440, demonstrating its ability to capture cross-dimensional sacrifice dynamics linking career breakthroughs and health deterioration. The Baseline model (AUC = 0.3583) fails entirely, performing below random guessing. This contrast underscores MTEN’s necessity when the target phenomenon requires modeling intertwined causal structures.

4.2.2. Distributional Shifts Render the Baseline Ineffective Even for Simple Tasks

For the single-dimensional health-crisis event (y3), MTEN again performs well (AUC = 0.7345), while the Baseline performs poorly (AUC = 0.3385). This failure is not due to inherent complexity in y3; rather, it arises because the training dataset consists of samples pre-filtered by the rare trade-off crisis. Such filtering induces highly skewed and atypical distributions within the y3 subset, leading the Baseline to fail. This demonstrates that when samples originate from a population shaped by complex multi-dimensional interactions, even single-dimensional tasks demand models with stronger representational capacity.

5.2.3. Recommendations for Model Selection

Based on our experiments, we suggest:

Simple models are preferable for strong-signal, single-dimensional tasks.

Composite “trade-off” events embody cross-dimensional

entanglement and require MTEN-like architectures.

AUC and F1 remain effective screening metrics.

As the statistical threshold (±1.5 × standard deviation) is a key

hyperparameter, subsequent sensitivity analyses are needed.

5. Conclusion

This study clarifies the causal chain linking event definition and model choice: the precision of event definition determines the learnability of task signals; simple models suffice for single-dimensional strong signals; but genuinely cross-dimensional events—those exhibiting sacrifice and trade-off structures—require entanglement-based multi-task models. Drawing on structural analogies from the generative–restrictive logic of the Five Elements and quantum entanglement, we introduced the “trade-off crisis” as a composite event and demonstrated MTEN’s advantages. For engineering practice, we recommend a three-step protocol: begin with clear data-driven event definitions; establish baseline performance using simple models; and introduce complex architectures only when cross-dimensional structure is empirically warranted.

Through multiple iterations within a reproducible experimental framework, three key conclusions emerge. First, the quality of event definition directly determines task feasibility, as clear formulations reduce noise and enhance learnability [

7,

8]. Second, for strong-signal events confined to a single dimension, simple models remain preferable, avoiding unnecessary complexity [

12,

16]. Third, authentic cross-dimensional “trade-off” events exhibit structural features of co-occurrence and sacrifice, and are better captured by models capable of representing cross-dimensional interactions and task coupling, as these mechanisms align with the causal architecture of the events themselves [

8,

17]. The study presents the analytical pipeline, evaluation metrics, and reproducible code supporting these conclusions.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: (1) we propose an innovative method that quantifies an abstract cultural concept—the Five Elements—and integrates it into modern deep learning models, offering a new paradigm for interdisciplinary research; (2) we design an interpretable Entanglement-Fusion Module that provides a new analytical tool for understanding how static and dynamic factors jointly shape long-term outcomes; (3) through rigorous experiments on a synthetic dataset, we validate the effectiveness and potential of models that incorporate “innate” information for life-trajectory prediction tasks. This study aims to serve as a catalyst for further interdisciplinary dialogue and exploration on how to combine ancient human wisdom with cutting-edge AI to achieve a more comprehensive and profound understanding of the complexity of human life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and H.L.; methodology, X.Z. and H.L.; software, X.Z.; validation, X.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, X.Z.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and H.L.; visualization, X.Z.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

If readers need the experimental data, please contact the author at: zxqsd@126.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to multiple AI models (such as ChatGPT 5.1, DeepSeek V3.1, TRAE 3, etc.) for their assistance. Their assistance has enhanced the depth and comprehensiveness of their thinking, the speed of paper writing, and the verification of some test results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263. [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. (1956). The Stress of Life . McGraw-Hill.

- Hawkins, D. M. (1980). Identification of Outliers . Chapman and Hall.

- Baumeister, R.F.; Heatherton, T.F. Self-Regulation Failure: An Overview. Psychol. Inq. 1996, 7, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping . Springer.

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 484, ISBN 978-0-521-89560-6.

- Domingos, P. A Few Useful Things to Know about Machine Learning. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 78–87. [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Vincent, P. Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 1798–1828. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning . MIT Press.

- Chandola, V., Banerjee, A., & Kumar, V. (2009). Anomaly Detection: A Survey. ACM Computing Surveys , 41(3), 1-58.

- Aggarwal, C. C. (2017). Outlier Analysis . Springer.

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin , 98(2), 310-357.

- Needham, J. (1956). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 2, History of Scientific Thought . Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, J. S. (1964). On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox. Physics Physique Fizika , 1(3), 195-200.

- Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M., & Horodecki, K. (2009). Quantum Entanglement. Reviews of Modern Physics , 81(2), 865-942.

- Occam, W. (14th century). Occam's Razor principle, as discussed in Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2020). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach . Pearson.

- Bishop, C. M. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning . Springer.

- Needham, J. (1956). Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 2: History of Scientific Thought. Cambridge University Press.

- Shun, K.-L.; Graham, A.C. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China.. Philos. Rev. 1992, 101, 717. [CrossRef]

- Jung, C. G., Wilhelm, R., & Wilhelm, H. (2011). The I ching or book of changes. Princeton University Press.

- Guying C. (2005). The I Ching: A New Translation and Commentary (Vol. 3). Commercial Press.

- Caruana, R. (1997). Multitask Learning. Machine Learning, 28(1), 41–75.

- Koller, D., & Friedman, N. (2009). Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques. MIT Press.

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 484, ISBN 978-0-521-89560-6.

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?. Phys. Rev. B 1935, 47, 777–780. [CrossRef]

- Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M., & Horodecki, K. (2009). Quantum Entanglement. Reviews of Modern Physics, 81(2), 865–942.

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum computation and quantum information. Cambridge university press.

- Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M., & Horodecki, K. (2009). Quantum entanglement. Reviews of modern physics, 81(2), 865-942.

- Ruder, S. (2017). An Overview of Multi-Task Learning in Deep Neural Networks. arXiv:1706.05098.

- Zhang, Y., & Yang, Q. (2021). A Survey on Multi-Task Learning. arXiv:1707.08114 (updated).

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- Brunner, N., Cavalcanti, D., Pironio, S., Scarani, V., & Wehner, S. (2014). Bell Nonlocality. Reviews of Modern Physics, 86(2), 419–478.

- Fawcett, T. (2006). An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern recognition letters, 27(8), 861-874.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).