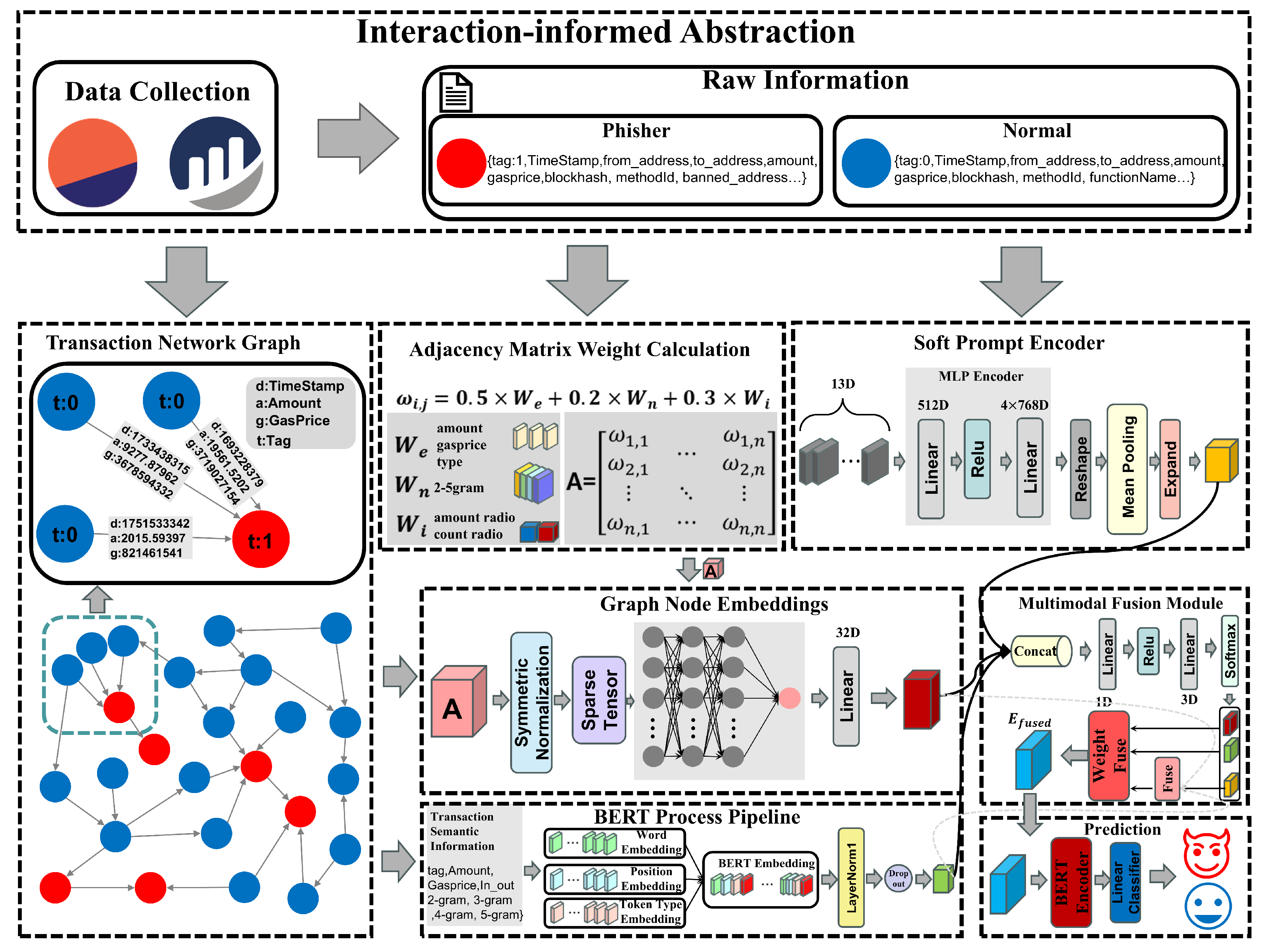

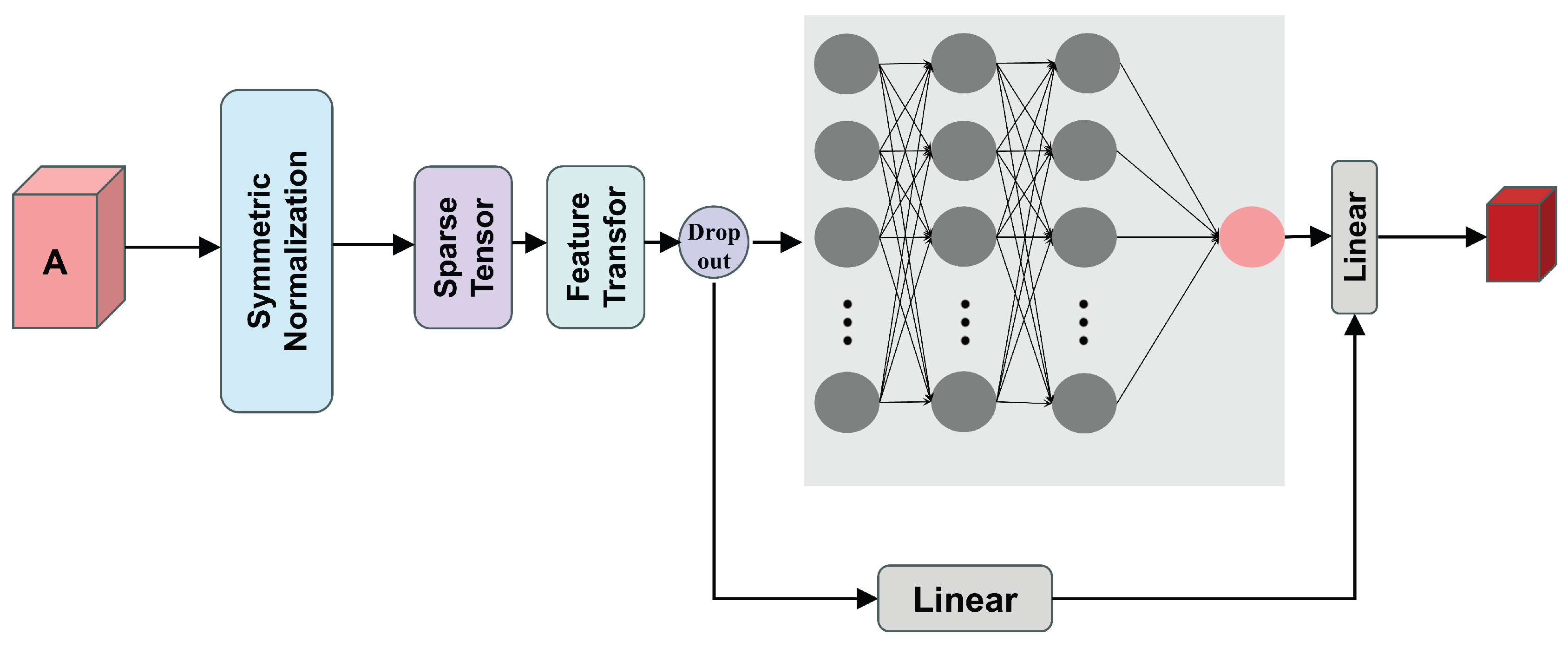

3.2.1. Graph Data Generation Based on Adjacency Matrices

Given the inherent complexity of transaction records within trading networks, effectively extracting inter-node transaction features presents a significant challenge. To address this, we propose a method that constructs adjacency matrices between account nodes and incorporates transaction weights to capture global trading characteristics. When processing each transaction record for an account, we first sort transactions by timestamp. This allows us to calculate the time difference between successive transactions, reflecting the actual sequence of account activity and the flow of funds within specific timeframes. By enhancing temporal aggregation features, we can effectively identify anomalous behavior within these accounts.

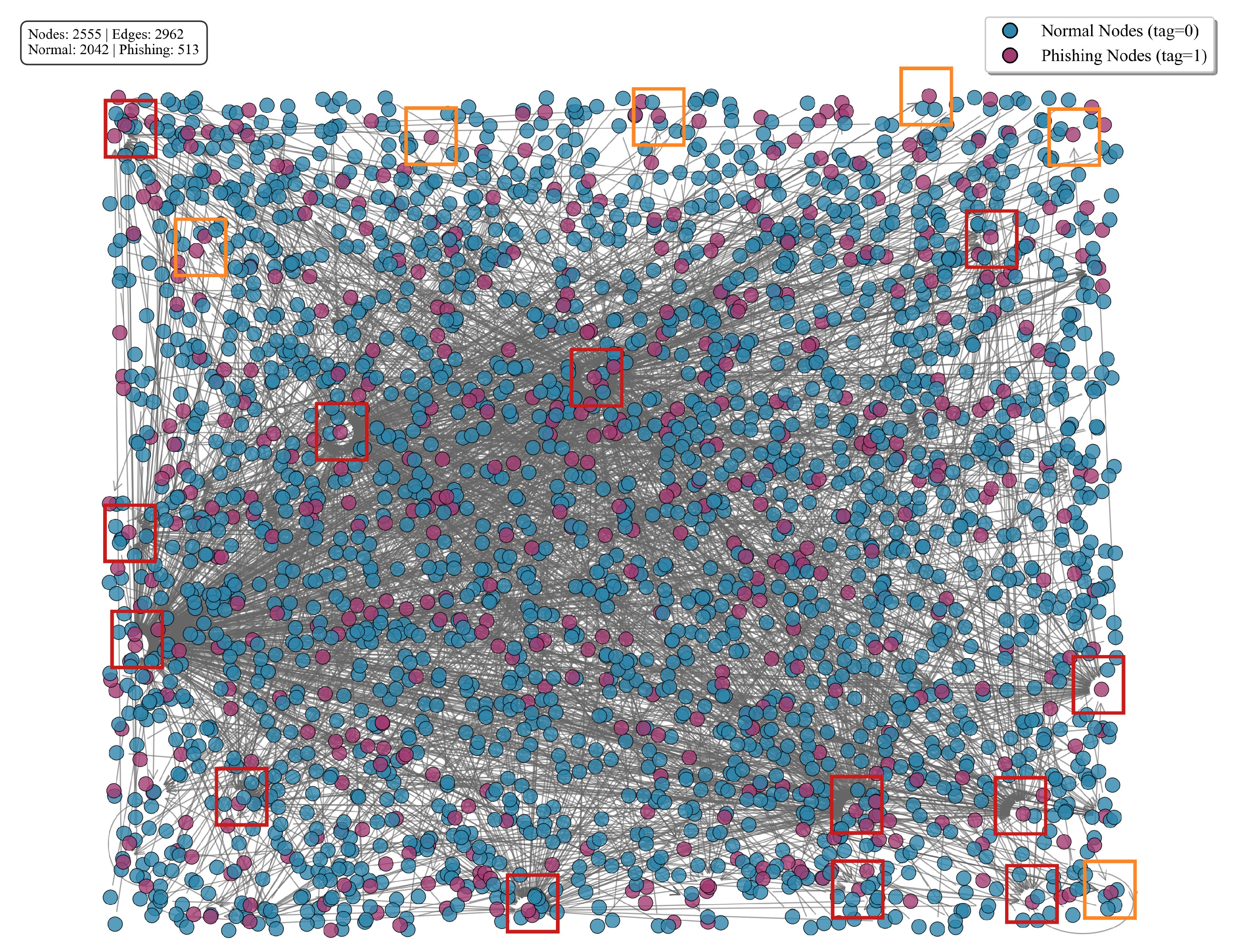

Based on the preprocessed transaction data, we constructed a directed multigraph

, where

V represents the set of account address nodes and

E represents the set of transaction edges. Each node

in the graph represents a unique account address, and each directed edge

signifies a transaction record from account

to account

. To quantify the degree of frequent transactions within a short period, we introduce the concept of n-gram time difference [

28]. The n-gram time difference is defined as the measure of an account’s transaction frequency by calculating the time difference between a transaction and its preceding n-1 transactions. In this study, we compute 2-gram to 5-gram time differences, as represented by the following formula:

Where

represents the timestamp of the

i-th transaction for an account, and

represents the timestamp of the

-th transaction for that account. If the number of transactions for an account is limited, this time difference is set to 0.

We constructed an

zero matrix

A, where

n is the total number of unique account addresses in the transaction network. The elements within this adjacency matrix represent the connection weights between corresponding addresses. For instance,

signifies the transaction weight between account

i and account

j across all transactions. The initial state of the adjacency matrix is as follows:

In a directed graph, each transaction record

includes a sender address and a receiver address. By traversing all transaction records within the directed graph, we construct a dictionary, ‘Index’, to map unique addresses to their corresponding indices. The keys of this dictionary are account addresses, and their values are their respective indices. We then map these account addresses to the indices of an empty adjacency matrix, as shown in the following formula:

Where

denotes the sender’s address,

denotes the sender’s index,

denotes the recipient’s address, and

denotes the recipient’s index.

We employ a multi-dimensional weighted calculation strategy, integrating four dimensions—timestamp differences, transaction amounts, gas prices, and stablecoin interaction characteristics to construct the connection weights of the adjacency matrix. For each element

within the adjacency matrix, its weight is calculated using the following fusion formula:

Where denotes the weighted fusion of transaction amount and gas price within transaction records, represents the n-gram time difference feature, and signifies the stablecoin account interaction feature. captures characteristics of high-value transactions; captures characteristics of frequent transactions within short timeframes; captures the proportion of transaction frequency between two distinct node categories.

Regarding the transaction execution time of phishing nodes, abnormal nodes usually set a high Gasprice to accelerate fund transfer. Therefore, when constructing matrix weights, a weighted calculation is performed on the transaction amount and Gasprice of the two types of nodes, with the formula as follows:

Where a denotes the transaction amount for a given transaction, g denotes the Gas price for that transaction, and respectively represent the logarithmically normalised transaction amount and Gas price, and denotes the node type weighting. If the transaction originates from a fishing node to another fishing node, is 2; if the transaction originates from a normal node to another fishing node, is 1.5. If the transaction is sent from a normal node to another normal node, is 1.

Some phishing nodes seek to evade suspension due to large transactions, employ frequent transactions within short timeframes to raise funds or transfer capital. In such scenarios, the n-gram time difference characteristic becomes particularly crucial. The formula for

is as follows:

Here, denotes the timestamp difference of the n-gram, represents the weighting coefficient of the n-gram, and signifies the maximum value among all 5-gram differences.

Within on-chain transaction networks, phishing nodes typically exhibit transaction input counts several times greater than their output counts, whereas normal nodes maintain nearly equal input and output counts due to their long-term transactional characteristics. To capture the interaction patterns of these two node types throughout their lifecycle, this paper defines a node’s input-to-output value ratio and input-to-output frequency ratio. These metrics are ultimately weighted and fused to form the account interaction feature

, calculated as follows:

Where

and

denote the ratio of incoming to outgoing amounts for the destination node and the ratio of incoming to outgoing amounts for the source node in a transaction record;

and

denote the ratio of incoming to outgoing occurrences for the destination node and the ratio of incoming to outgoing occurrences for the source node in a transaction record. The

function is a non-linear compression function. The weights ultimately populated into the adjacency matrix are:

Where denotes the set of all transactions between accounts and . Consequently, the adjacency matrix elements reflect the transaction amounts and Gas price weights between two accounts, the overall transaction frequency, and the characteristics of interactions between different account types.The resulting adjacency matrix will serve as input to the graph convolutional network module, enabling the model to capture structural relationships within the directed graph.