1. Introduction

Since the release of BERT in 2018 computational social science and social science more generally has profited from a vast increase in accessibility of computational methods for the analysis of large sets of natural speech data. The particular qualities of large language models (LLM) surpass many previous approaches to annotation and classification of natural language texts [

1]. Annotation is one of the most time-intensive and costly tasks in the preparation of corpora for further qualitative and quantitative analysis and LLMs offer new options for quick and cost-effective annotation of increasingly large corpora. Compared to previous approaches of computational annotation like Naïve Bayes classification, LLMs profit from training before deployment and semantic capabilities often surpass those of previous approaches [

1]. Recent developments in the accessibility of open-access LLMs have the potential to decrease the burden for low-level annotation even further. Individual researchers, small research teams and groups with little to no funding gain a potentially increased capability to conduct annotation for large corpora that would have previously necessitated employment of human annotators or training a classifier for the task. Compared to the option of supervised training of a classifier, a large advantage of LLM is zero- and few-shot annotation which negates the necessity for preparing a dataset for training and training a classifier. This increase in accessibility of easy annotation might well positively affect research on discourse and language multiple ways, foremost by likely increasing the number of publications utilizing increasingly large corpora.

On the other hand, LLM based annotation introduces new hurdles to contend with. Larger models with more parameters require increased computational power hardly available on consumer grade hardware and thus necessitate either increasingly expensive hardware or cloud computing solutions. But this is not the only issue as previous research has shown that word embeddings often mirror biases against marginalized groups and are far from neutral (Garg et al., 2018). This observation makes it clear that LLM cannot simply be used “out of the box” but that researchers have to be aware of the potential issues of LLM. Against this background of novel capabilities and novel issues, this paper focuses on LLM based annotation for utilization by individual researchers, groups without funding or other reasons that make human annotation or even paid LLM annotation infeasible.

The main idea this paper aims to examine is the potential offered by small LLM, with fewer than 14b parameters, to increase accessibility for semantically complex data annotation performed by research groups with little to no funding and hardware. To establish the feasibility of LLM annotation in such a setting, the question at hand is therefore: To what extent can locally executed small LLMs (<14B parameters) provide accurate, reliable few-shot annotation of semantically complex social-science text (topic labels), given typical consumer-grade hardware and constrained budgets? What specific limitations (topic prevalence, historical shift, gendered bias) can be expected? The core investigation is informed by potential as well as previously identified advantages and disadvantages given the setting that inform the research design. These considerations informed two linked investigations. The topic prevalence investigation addresses expected issues with the prevalence of different topics in training data for smaller models. The second diachronic prevalence investigation concerns potential limitations of smaller models given expected issues with training data from different periods in time.

The first potential issue that will be explored and tested is the assumption that topics that feature less in the model dataset might result in lower annotation quality. Additional limitations expected are gendered bias in the model embeddings as well as historical bias. These issues should be exacerbated for smaller LLM particularly since topics that are rare in larger models should be even less pronounced in the embeddings of smaller models. Therefore, two topics “Economy” and “Abortion” are selected for the comparison of topic annotation task quality as the first is featured often in public debate and is thus assumed to have a high prevalence within the training data whereas the latter is a more occasional topic with clear and identifiable conjunctural changes in political discussion

1 . For the comparison of topic annotation quality, common evaluation metrics of both annotation tasks are compared for all models to identify potential trends in annotation quality. The second possible issue tested concerns potentially biased training data in terms of its historicity. Since most training data is assumed to be sourced from the internet, it is likely that LLM training data is biased toward more recent modes of speaking. Therefore, the second investigation conducts a comparison between the quality of annotation of samples from different historical episodes to identify suspected issues with the annotation of historical data. These two linked comparisons and the low number of parameters, aim at deliberately prodding the limitations of few-shot annotation that is still useful for sociological analysis. The annotation task is dichotomous, and all annotations are conducted on samples from a dataset sourced from speeches made in the German parliament between 1949 and 2025.

After a brief overview of contemporary literature on the topic, a theoretical exploration describes potential issues of LLM based annotation while also exploring likely advantages of the approach. Following this exploration, the model selection, evaluation metrics, dataset and prompting strategies are outlined. For both brevity and readability model only relevant comparisons will be explored

2 in detail in the results section. The interpretation focuses on the theoretical and practical implications of said results. Following a discussion of the limitations of this paper a conclusion explains some further research that could improve on said limitations.

1.1. Literature

Utilization of LLMs for data annotation has steadily increased since the release of BERT [

2] and especially after the release of ChatGPT. Today, the use of LLM as an approach to data annotation has precedent in a range of different disciplines. Ziems et al. [

3] focus on the role of LLM for social sciences and zero-shot annotation specifically. They test 13 LLM for various tasks relevant to sociological and political analysis of text data. The authors conclude that LLMs are not capable of surpassing the precision of finetuned classifiers but achieve notable agreement with human annotators. Ziems et al. contrast their findings with the results of crowdworkers and note that LLM generation often surpasses the work of crowdworkers. Ni et al. [

4] focus on utilizing free open access models for the annotation of datasets in preparation of RAG (retrieval augmented generation) development. They highlight the cost of human expert or GPT-4 annotation and thus attempt to utilize freely accessible LLM’s for the annotation of datasets. Savelka & Ashley [

5] focus on the use of GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 Turbo for the annotation of legal texts and are able to show that GPT-4 performs well on annotation of a legal dataset and highlight its costs and suspected drawbacks. They specifically explore the pricing of different LLM’s, and they demonstrate how utilization of cloud-computing for LLM can relatively quickly result in increasing costs. They furthermore note that the relatively low accuracy scores of their zero-shot annotation limits the possible application of LLM annotation for tasks requiring high accuracy. Heseltine et al. [

6] specifically focus on comparing human annotation with GPT-4 annotation noting the cost-effectiveness and quality of the latter. They do caution that LLM performance drops for the annotation of non-English datasets. Abraham et al. [

7] note that LLM can perform very well in terms of annotation, providing a cheap, quick, and accurate option for complex annotation tasks given a good prompting strategy. They note that this aspect of prompt strategy and structure has largely been under-investigated by most papers despite its large impact on LLM performance. They conclude with the introduction of systematic prompt testing, highlighting its strong effects on annotation quality. Meanwhile Brown et al. [

8] study suspected demographic bias in LLM annotation, finding that LLM tend to annotate demographically biased, but that this annotation is connected to the dataset and not the model selection. They further note that LLM disagreement is largely driven by ‘label entropy’, meaning that LLM struggle with annotation when human annotators struggle likewise. Garg et al. [

9] show how embeddings central to modern LLM are affected by sexist bias and how this bias even changes over time. Schröder et al. [

10] caution against the idea of controlling for biases and issues in LLM annotation by introducing a human control annotator into the annotation pipeline noting that human annotators often use LLM annotation for anchoring, thus aligning themselves with the LLM annotations instead of the other way around.

For this paper some immediate implications follow from this literature review. The first notable observation of the literature review was that authors [

4] most often chose licenced models provided by AI companies, particularly GPT-4, instead of running locally executed LLM. They tend to further focus on larger models with closed or limited access. Apart from Ni et al. (2025) no team focused on the inherent possibilities of smaller LLM for annotation. This aspect of LLM annotation is therefore largely under-investigated warranting further research. For the immediate methodological approach Abraham et al. [

7] are informative as they highlight the necessity to experiment with prompting structure for optimal results. Schröder et al.’s [

10] paper inform the methodological decision to submit the dataset to human annotator blinded to the LLM annotations to avoid the anchoring effect in the human annotation. These papers strongly inform both the expected advantages and disadvantages explored in the next section as well as the methodology in 2.1.

1.2. Potential Advantages of LLM Annotation

LLM provide multiple advantages for annotation that traditional approaches via human annotation and trained classifier do not. Further advantages arise from utilization of open-access models with smaller sizes. This section will briefly describe these expected advantages as well as likely disadvantages for utilizing small open-access LLM for annotation of natural language data for quantitative and qualitative social science research. These assumed advantages will be explored as part of this paper, highlighting the actualization of potential advantages and shortcomings.

A first significant advantage is the comparatively low cost LLM annotation can provide [

6]. Since access to a desktop computer is common, open access LLM enable annotation that is close to free [

4] and scalable given time constraints. This allows small academic teams, individual researchers or even students to focus on more cognitively demanding tasks or to forgo the need to hire human labourers for the annotation tasks. While utilizing paid LLM annotation through for example API access from companies like OpenAI, is already more cost efficient than paying crowd-workers or student assistants [

11], usage of open-access models provides both more control and practically free annotation. This in turn positively affects the incentive structure for researchers which may positively affect annotation quality. Paid access to an LLM API results in an incentive structure that disincentivizes experimentation with prompting strategy and creates lock-in effects. As every attempted prompting strategy cost money, the researcher is disincentivized from experimenting and improving on their prompt strategy and will instead likely act in satisficing

3 [

12] behaviour. Meanwhile this is not the case for utilizing locally run LLM as the cost approaches zero and low annotation times positively affect experimentation. This advantage of increased control can be extrapolated further.

Increased control generally is the second large advantage of local LLM annotation. Utilizing annotation through an AI-providers API can affect the annotation quality by reducing control over the model. Mentions of suicide, sexual deviancy or crime can result in null-results when annotating via AI-service providers, caused by content moderation (Abraham et al., 2025, p. 3). While many providers maintain such safeguards, running LLM locally means the possibility to download uncensored models or even to train them further. Likewise local LLM annotation positively affects researcher control over the annotation compared to student assistant or crowd worker enabled annotation. Retraining a student assistant usually reduces their available monthly hours, thus again incentivizing satisficing researcher behaviour. The need to schedule meetings and imperfect communication further deepens this issue. Both for crowd workers as well as student assistants, the agent-principal problem [

13] potentially affects the annotation quality also. As annotation is usually a boring and repetitive task, the human annotator is incentivised to do the least amount of work. This results in annotation in which researcher and student assistant are likely to have diverging interests reducing annotation quality via reduced control over the annotation process. Utilizing LLM for local annotation negates this issue, as LLM do not suffer from boredom or refrain from repetitive tasks. Shirking and similar behaviour are not known issues affecting LLM annotation. LLM annotation thus has the potential to positively affect both the annotation quality as well as the potential size of the annotated corpus as repetition does not negatively affect annotation.

While the resulting annotated corpus can easily be scaled up compared to human annotation, LLM annotation does not need a large training datasets like those required for traditional machine-learning classifiers. For LLM annotation, little to no training for either classifier or human annotator is necessary while it is still a possibility for finetuning. A conventional classifier requires an annotated dataset and a dataset for evaluation whereas LLM annotation only needs the latter. Furthermore, LLM annotation is more capable for dealing with unexpected data. If a classifier has not encountered an unusual phrase or idiom, it is unlikely to correctly annotate it. Since LLM architecture relies more on semantic structures it is often more likely to pick up idioms or unexpected phrases and thus more likely to properly annotate such.

Meanwhile the smaller model size selected for this paper offers several additional advantages. 14b parameters are the upper limit for mid-range consumer GPU with no more than 12GB VRAM. While a 12b parameter model is often outperformed by models like GPT-4 these models have the advantage of running entirely locally without relying on an internet connection (after downloading the model files) or an API key. This is highly advantageous for replicability as replication packages can be offered to other researchers aiming to reproduce results without them having to subscribe to any LLM services. This local annotation is also highly valuable as it potentially offers a far greater degree of privacy. Utilizing LLM services offered by AI-companies runs the risk of uploading data to jurisdictions with little to no privacy protection for foreign nationals or data-breaches. Both issues are far less likely when running a local LLM annotation on a private or institute PC.

Local annotation using small LLM compared to closed access models positively affects experimentation and decreases cost generally. Contracted human annotators are likely to be surpassed by LLM annotation given the changed incentive structure and traditional classifiers require larger pre-annotated datasets for training and evaluation. The utilization of LLM likely results in more researcher control overall. On the other hand, it could be argued that the need for a large dataset of training data is only externalized and control gained through the utilization of LLM annotation is also mirrored by a loss of control as the next section will explore.

1.3. Potential Disadvantages

The decreased need for a training dataset is potentially offset by the externalization of that step within the research process. Training and deploying a traditional classifier with a custom dataset of annotated training data includes degrees of freedom and specific methodological choices a researcher may take. These methodological choices might include the data source for training, the preprocessing method and specific considerations for the research question at hand. Choices like these are likely not offered by the utilization of LLM for annotation. These advantages in terms of selective considerations have the possibility to be negated by the sheer volume of training data most LLM are trained with as cases in which training data were structurally biased or poorly annotated, would lead to the researcher being potentially less aware of those biases and limitations as compared to creating a dataset for training from scratch. Biases within training data have been reported upon [

7] and much data annotation has been put under scrutiny due to biased outputs from models but there are additional issues [

9]. If a specific topic has a low prevalence within a LLM’s training data, the model is likely to perform worse on tasks regarding the topic [

7]. Since access to much of the training data for LLM is restricted by intellectual property, a researcher might not have any possibility of assessing topic prevalence within the training data of an LLM. This has the potential to introduce an additional source of bias into a research project that the researcher can only broadly reflect upon and adjust for. In addition to assumed sexist or political bias, the training data for LLM is likely to exclude data that is hard to access because it is not easily machine-read or simply because it has not yet been included in the training data [

7]. Therefore, there is the potential for historical bias in the sense that most of the data utilized for LLM training may well be from 2000 and onwards as most of the training data is likely acquired from the internet. Since few companies disclose their training data this historic bias might therefore also be an issue for researchers to be aware of.

The additional control LLM annotation provides to a researcher could be offset by the probabilistic nature of LLM (Abraham et al., 2025, p. 4). Where a researcher can ask their colleague to elaborate on their annotation choice, a LLM is more likely to hallucinate a justification compared to most researchers. Hallucinations, more generally, are a potential issue with any utilization of LLM, but this means that the researcher´s control over the model is also somewhat limited. Taking a more constructivist epistemological perspective may invite questions about the value of LLM annotation, as the previously described anchoring effect might flatten the range of potential interpretations of an annotation task that would otherwise be deliberated by the entire research team or thoughtful consideration

4.

The positive effects might thus be mirrored by a loss of control in terms of externalization of the training and tool development to AI companies which introduces more sources of unreflected bias and the probabilistic nature of LLM generally. As these hypothetical, theoretical as well as the previously published literature highlight, LLM have the capacity to positively affect annotation both in terms of accessibility as well as quality. This might serve as a boon to both qualitative as well as quantitative research on discourse. These expected advantages and disadvantages inform the central investigations of this paper. As the research question is: “To what extent can locally executed small LLMs (<14B parameters) provide accurate, reliable few-shot annotation of semantically complex social-science text (topic labels), given typical consumer-grade hardware and constrained budgets? What specific limitations (topic prevalence, historical shift, gendered bias) can be expected?” the first aspect is the investigation of the now explored potential advantages of LLM whereas the second aspect is the investigation of the suspected issues with topic prevalence bias and historicity induced bias more generally caused by the externalization of the LLM training. The next section will explore the operationalization, data and methods of these investigations.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

For identifying annotation bias based on topic prevalence, two different topics are selected for dichotomous annotation by the LLMs. The first topic is concerned with abortion and reproductive freedom. This choice is based on the relatively low prevalence of discussions on the topic within the dataset. While it has been a topic that has been relevant in the last few years, it has distinct conjunctural cycles unlike more frequent topics like for example defence or the economy. The second reason for this selection is based on previous studies identifying a distinct LLM bias in terms of gender (Garg et al., 2018). If LLM tend to show gendered bias, it can reasonably be expected that they also struggle with annotation of topics traditionally associated with feminity. The second topic thus mirrors the first topic in terms of prevalence and gendered social interpretation

5. As discussions about the economy are very common in political discourse and since the economy is traditionally socially interpreted as a masculine (Peterson, 2005, p. 514) topic, this topic selection should result in more accurate annotation if the annotation is indeed affected by topic prevalence as well as gendered bias

6. For this investigation, two datasets are created for the annotation task. The abortion annotation sample consists of two entire chunkified sessions of the Bundestag. This preselection was necessary as the topic is so infrequently discussed that a random choice selection on average results in no single discussion of the topic within the evaluation sample. The samples for the annotation of economic topics are randomly selected. While this potentially introduces confounding, an alternative approach without preselection would not have captured any instances of the abortion topic within each sample. A comparison between the annotation of both topics should highlight any actualization of the suspected topic prevalence issues.

The second potential issue with LLM based annotation, historicity-induced bias, will be tested by comparing the annotation quality of two different samples from historical episodes in German political history. Here the first abortion annotation sample metrics are compared to a second sample given the same annotation task. As both samples are roughly 50 years apart, any issues arising from training data favouring more recent data sources should be identifiable by a worse annotation quality of the older sample. An additional comparison between the random sample for the economic annotation task and a random selection sample picked after 2020 serves to strengthen or differentiate the results of the comparison between the other samples. If either of these annotation tasks is notably affected by model bias the feasibility of local LLM annotation for social sciences would be negatively affected as topics like abortion and historical comparison are of particular relevance to social sciences research, often focusing on issues of marginalization and social change.

2.2. Dataset and Sampling

The dataset for testing the annotation quality of the models is based on 1444 sessions of the German parliament between 1949 and 2025. All sessions in that timeframe were acquired using a custom scraper accessing the API of the German parliaments archival service. The approach for selecting chunks for analysis follows an approach similar to Datta et al. (2024). Thus, sessions were semantically preselected by a list of keywords surrounding reproductive freedom and abortion. This preselection was necessary since the original corpus of parliamentary sessions is even larger. Since manual inspection of the sessions revealed that topics about the economy feature in practically every session of the German parliament, no preselection was necessary for this topic as it was prevalent in high frequency

7. This semantic preselection for discussions about reproductive rights resulted in the 1444 sessions featuring the set of keywords that were split via a recursive text splitter from the Langchain package into single speeches that are the target for retrieval via annotation. An introductory approach towards chunking revealed that the simple chunking of speeches via a speaker pattern reduced context to a degree that made meaningful annotation often impossible. Chunks with less than 300 characters where thus combined with the previous chunk. This decision was based on previous research, showing that LLM can identify allusions and subtle hints (Törnberg, 2024) but relies on context. Manual dataset inspection revealed these 300-character speeches annotation often relied on context outside the chunk itself and referred to the previous speech. Combining both chunks allowed for capturing the context of the speech and to enable more specific annotation. Qualitative analysis of the resulting preselected dataset was conducted to select 2 sessions from different points in time that heavily features the topic in question.

The first sample selected was the entire session of the German parliament April 25th, 1974, during which a debate took place at a time in which feminist issues became a relevant political issue. This date marks the first time the FRG parliament attempted a legalization of abortion and thus the resulting dataset contains about 1/3 of speeches about the topic. The second dataset is from the 24th of June.2022 when a debate about abolishing §219a StGB took place which forbade advertising abortion services. Thus, this section too contains a high prevalence about topics of reproductive rights. This diachronic sampling allows for comparing the annotation quality to identify and highlight potential historicity induced bias. For the two samples for testing the annotation of economic topics, two random samples with 150 entries each were selected with the first one being sampled completely at random and the second one from sessions after 2020 to only include more recent discussions. It is notable that, as expected, the prevalence of topics discussing reproductive freedom is rather low. Excluding single mentions and remarks, in only 500 sessions of the parliament did members engage at all with this topic. This affirms the topic selection as it points towards a topic with low prevalence within the training data of LLM too. Combining each two samples thus results in samples of at minimum 300 annotated chunks for both annotation topic tasks.

2.3. Manual Expert Coding

These samples were annotated manually by 2 human coders based on a binary decision whether issues of reproductive freedom were mentioned in the speech at any point. The first annotation was done by a student of a different discipline (Public management) analogous to a student assistant with the second annotation conducted by the author as the expert annotator analogue. The student assistant was supplied with an annotation guideline mirroring the prompt submitted to the LLM. Discrepancies between the coders were discussed and mutually resolved to create the final expert/goldstandard annotation. For the first two sets the student assistants original annotations too were kept for comparing the baseline student assistant performance to the models. Only the aggregate annotation of both annotators serves as the gold standard against which the models were tested though.

2.4. LLM Specifications

Multiple different models were tested for comparing if meaningful differences in evaluation metrics could be identified for the low number of parameters of each model. For the model selection Qwen2.5:7b, Gemma3:4b, Mistral:7b, Llama3.2:latest, Stablelm2:12b and Phi:2.7b were selected based on their current popularity and availability of a branch with less than 14b parameters on the Ollama platform. All models have multilingual capabilities allowing for annotation of the German language samples. Furthermore, the models vary in parameter size which enables a stronger comparison based on model size affecting both the requirements on hard drive space as well as computational time. All models were included in a pipeline that featured an identical few shot-prompt and structured output running locally on a NVIDIA Geforce RTX 3080ti with 12GB of available VRAM.

2.5. Prompt strategy

For prompting, different strategies were attempted in line with Abraham et al. (2025) until 3 example annotations submitted were considered to result in a sufficient balance between computational time and accuracy. A pipeline for model annotation meant that every model utilized the same prompting structure which was also provided to the student assistant annotator. The general prompting structure followed a few-shot approach to provide the models with some example annotations. Therefore, the models and human annotator were provided a task description as well as 3 examples of correct annotation. This approach while increasing computational load has the advantage of increasing annotation accuracy without the necessity for increasing model size thus providing a potentially useful trade-off between the advantages of smaller models and annotation accuracy. The final prompt structure was thus:

You are an expert classifier. Classify whether political speeches discuss topics of abortion and/or reproductive rights (including abortion, §218, reproductive autonomy, family planning, contraception, etc.), either explicitly or implicitly. If yes, reply only ’1’. If not, reply only ’0’.

This was followed by these examples:

role": "user", "content": "Ich bin gegen die Reform des § 218. — Are topics of abortion and reproductive rights discussed? Classify with ’1’ for yes or ’0’ for no."}, {"role": "assistant", "content": "1"}, {"role": "user", "content": "Der Verkehrsausschuss tagte heute zum Thema Infrastruktur. — Are topics of abortion and reproductive rights discussed? Classify with ’1’ for yes or ’0’ for no."}, {"role": "assistant", "content": "0"}, {"role": "user", "content": "Frauen sollen selbst entscheiden dürfen, ob sie ein Kind bekommen. — Are topics of abortion and reproductive rights discussed? Classify with ’1’ for yes or ’0’ for no."}, {"role": "assistant", "content": "1"}8

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

For evaluation of annotation quality, multiple metrics were calculated. Accuracy describes the proportion of correctly annotated chunks, with the expert annotation serving as the gold standard. Precision captures the amount of correctly predicted items. The recall metric assesses the number of actual positives identified by the model and the F1 score calculates a mean of both previous metrics (Pedregosa et al., 2011). As F1 score serve as a decent heuristic for general model task quality it is the primary metric reported upon. These metrics are calculated for all models and the student assistant. Krippendorff’s alpha is calculated for assessing the intercoder agreement and thus only captures the general performance of all included models. To reduce redundancy, not all models’ metrics are reported for each model and only relevant differences are highlighted. An additional model-agreement metric is constructed using an inverted gaussian function (

Figure 1) to identify cases where model agreement is low. Since the prompting and structured output only allows for 0 and 1 annotations, a maximum disagreement would result in a mean annotation of 0.5. Therefore, the gaussian function plots model each mean and scales it from 0 to 1 with 1 being perfect agreement and 0 being perfect disagreement. The function for scaling follows a gaussian function with

=0.5 and

=0.166 serving as arbitrary approximations for achieving a normal distribution.

Since this is no statistical test, it can only serve as an additional heuristic for comparing chunks that cause strong disagreement between the models, this latter goal was the core reason for construction of the intermodel agreement index. The next section will report upon these metrics for the different tasks beginning with the reproductive rights annotation task

9.

3. Results

3.1. Reproductive Rights Annotation Task

This section breaks down the results of the annotation process without interpretation beginning with the abortion annotation task for sample 1. Therefore, the following results are calculated for the April 25, 1974, sample. With the exception of Mistral:7b and Phi:2.7b all models perform with F1 scores above 0.85. A value of 0.46 for Krippendorff’s alpha shows moderate agreement between the models. After removing two problematic models Phi:2.7b and Mistral:7b, Krippendorff’s alpha rises to 0.75 denoting substantial agreement. As for the individual model performance the annotation quality varies moderately depending on the model.

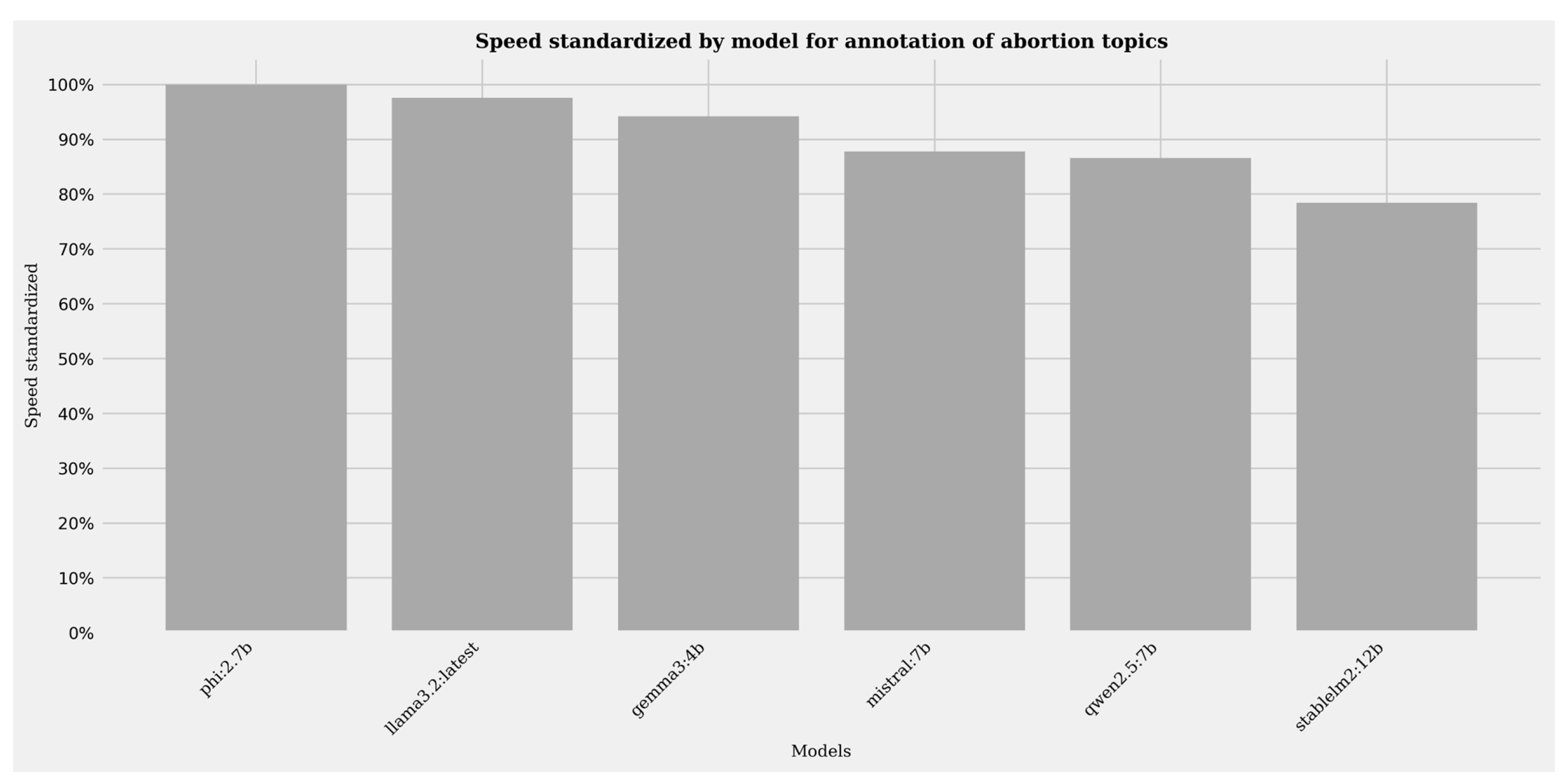

Stablelm2:12b generally performs with the highest scores in terms of pure evaluation metrics but comparing its speed to the other models highlights its relatively slow computational speed compared to the other models. Its computational speed is on average about 20% slower than Phi:2.7b

10. A precision score of 0.94 and 0.90 marks its capability to approach the quality of human annotation by lay annotators. Recall likewise is high with a score of 0.86 and 0.97. The combined F1 scores of 0.93 (Class 1 = positive annotation) and 0.90 (Class 0 = negative annotations) further stress the high annotation quality achieved.

Phi:2.7b is the top model in terms of speed surpassing all other models while at the same time dropping in accuracy and recall to F1 scores of 0.67 and 0.77. It is the only model that drops below a F1 score of 0.7 for positive annotations. It’s accuracy likewise is scored with 0.73.

Like Stablelm2:12b, Qwen2.5:7b performs with comparatively high scores, scoring F1 metrics of 0.91 and 0.94 surpassing all but the student assistant’s evaluation metrics. Its precision too is about as high (0.93/0.92) as Stablelm2:12b. Its recall performance is only surpassed by Gemma3:4b for positive annotations and Stablelm2:12b for negative annotations.

Llama3.2:latest performs well in terms of most metrics. Its performance is slightly worse compared to Qwen2.5:7b and Stablelm2:12b but it’s the second fastest model only 5% slower than Phi:2.7b. When comparing Llama3.2:latest and Stablelm2:12b, the former performs about 20% faster while losing only a little in terms of annotation evaluation scores.

Gemma3:4b performs slightly worse than the previous models for the annotation and is only about as fast as Llama3.2:latest.

Mistral:7b is the only model incapable of annotating the dataset given the prompt submitted to all models. All chunks are annotated NA (transformed to 0) due to the structured output settings.

The student assistants first set of self-guided annotation had the best scores in terms of accuracy, recall and precision but comparatively slow annotation times roughly 13x slower than Phi:2.7b ( 200 seconds vs. 2700 seconds for the sample). The expert annotation time combining student assistant and author annotation took even longer ( 7400 seconds).

Krippendorff’s alpha is relatively high for the annotation task on this sample and excluding Mistral:7b and Phi:2.7b results in substantial agreement between the model annotation. When assessing the intermodel agreement index, it’s notable that the annotation of chunks with higher intermodel agreement index values are on average longer than chunks with high agreement. The intermodel agreement index highlights that models most often annotate similar except for some specific cases. These cases are usually longer in size and feature more complex arguments.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of evaluation metrics (Abortion annotation task sample 1)

Figure 2.

Heatmap of evaluation metrics (Abortion annotation task sample 1)

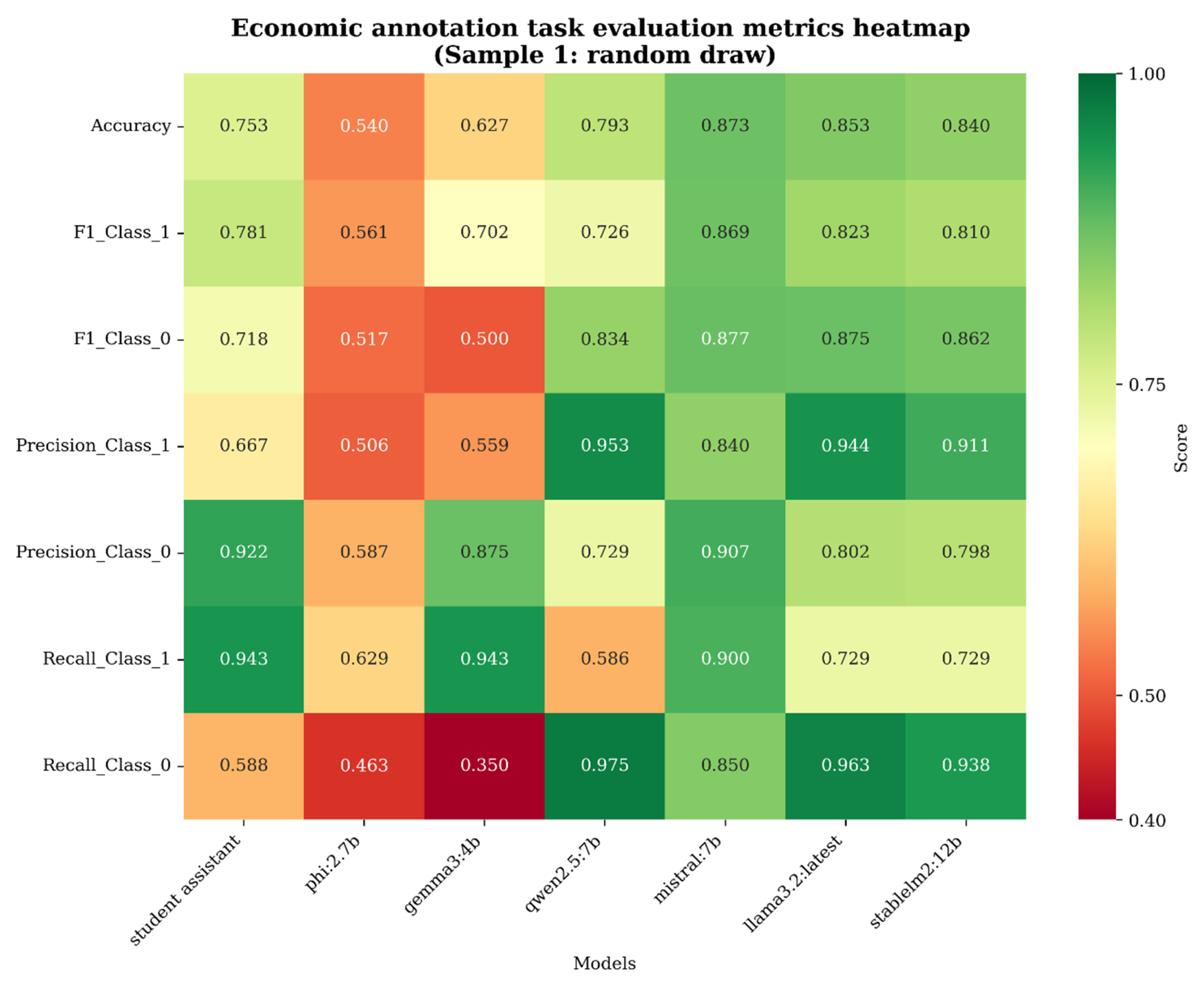

3.2. Economic Annotation Task

The evaluation metrics are worse for the annotation of economic topics. The first sample annotated for the economic annotation tasks consists of randomly selected chunks. All models as well as the student assistant performed with lower scores for this annotation task compared to the reproductive rights annotation. Krippendorff’s alpha is significantly lower for this set of annotations to. It’s value of 0.4 shows fair agreement.

Stablelm2:12b again with high values on most metrics while taking the longest for annotation of the sample again being about 25% slower than Phi:2.7b.

Phi:2.7b again performs the best in terms of speed alone but its annotation quality again is severely lacking for this annotation task. Accuracy (0.54), recall (0.63/0.46) and precision (0.50/0.59) are significantly lower than any other model.

Qwen2.5:7b has a notable drop in terms of recall (0.58/0.98) and precision (0.72/0.95) compared to the annotation of abortion resulting in F1 scores of 0.73 and 0.83.

Likewise, Llama3.2:latest annotates with scores above 0.8 on all metrics but recall class 1. Its annotation speed is again close to phi and its F1 scores are 0.82 and 0.87.

Gemma3:4b has the second lowest F1 scores after Phi:2.7b with 0.70 and 0.50 respectively. Its recall is very low for negative annotations scoring 0.35. For this annotation task,

Mistral:7b achieves high scores on all metrics but speed. Its F1 scores of 0.82 and 0.88 are comparatively high and only surpassed by Qwen2.5:7b. Even when excluding Phi:2.7b, Krippendorff’s alpha still has a value of 0.40 denoting substantial disagreement between models. Unlike the previous annotation task, the intermodel agreement index largely results in higher values when comparing single entry annotation.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of evaluation metrics (Economic annotation task)

Figure 3.

Heatmap of evaluation metrics (Economic annotation task)

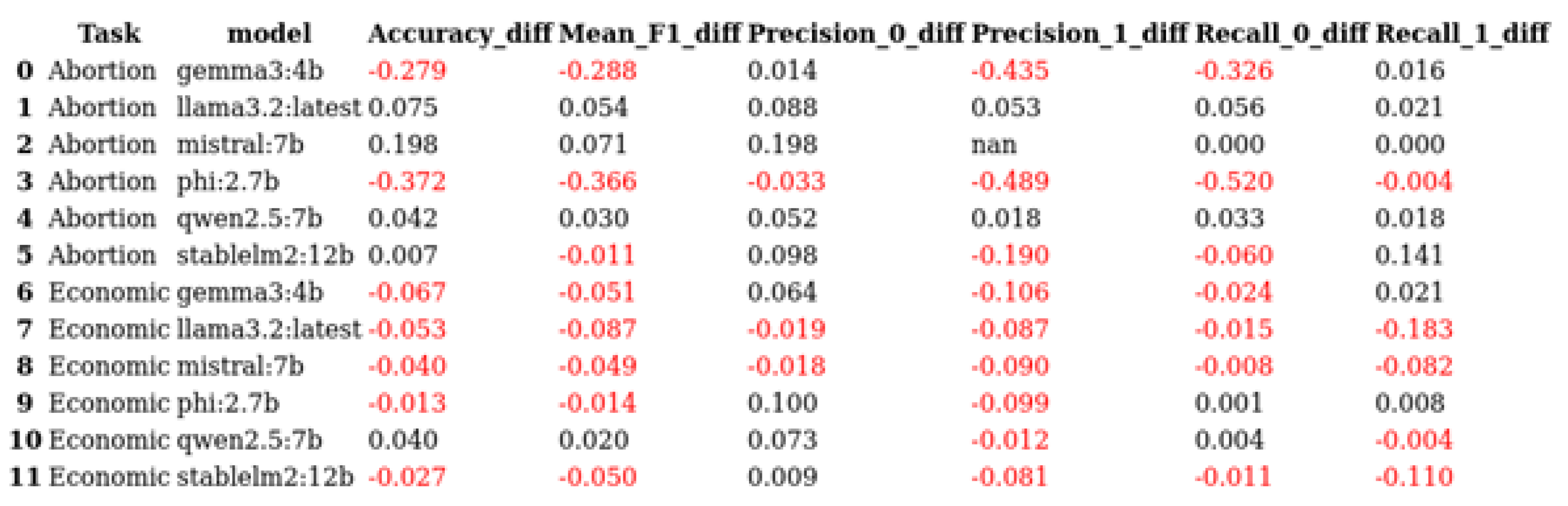

3.3. Diachronic Comparison

For the diachronic comparison of annotation quality, the quality of annotations is worse for both the abortion annotation task comparing the 1974 sample to a 2022 sample and the economic annotation task comparing a random sample to a random sample for a subset after 2020. This means that for both the annotation of topics of reproductive freedom as well as economic topics, the annotation quality of the more recent sample is on average lower. The mean F1 score for all models drops from 0.74 for the annotation of economic topic on the older dataset to 0.70. For the annotation of reproductive topics, the mean F1 score for all models drops from 0.75 to 0.71. The decreases in F1 score are largely uniform with every model decreasing in F1 scores for both annotation tasks. Only the F1 scores for Llama3.2:latest does not drop for the annotation of reproductive topics while Gemma3:4b does not decrease in F1 score for the economic annotation task. Mistral:7b is again unable of annotating the abortion topics and performs with relatively high scores for the annotation of economic topics not dropping below 0.75 on any metric. For these more recent samples Phi:2.7b and Gemma3:4b largely drop to scores below 0.5. The abortion annotation task results in Stablelm2:12b, Llama3.2:latest and Qwen2.5:7b still achieving relatively high annotation evaluation metrics while still being lower than with the older sample. For the economic annotation task, the evaluation metrics are again lower than the metrics of the abortion annotation task but the F1 scores of Mistral:7b, Qwen2:7b, Llama3.2:latest and Stablelm2:12b still mostly surpass 0.7 and 0.8. A Krippendorff’s alpha score of 0.15 for the annotation of abortion topics, and 0.23 for the annotation of economic topics highlights the lower performance metrics further. When selectively excluding Mistral:7b and Phi:2.7b from the calculation, Krippendorff’s alpha increases to 0.48 and 0.29 each.

Figure 4.

Table of differences in evaluation metrics between samples (Sample 2 - Sample 1)

Figure 4.

Table of differences in evaluation metrics between samples (Sample 2 - Sample 1)

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

This section will briefly interpret individual model performance, go on to examine the results in terms of expected advantages of LLM annotation and then move on to the interpretation in regard to expected disadvantages. Overall Llama3.2:latest and Qwen2.5:7b perform well in terms of providing a quick and accurate annotation. While Stablelm2:12b on aggregate has high accuracy and recall in all measures, its comparatively large size and computational load leads to significantly increased computational times. It’s per annotation time is about 1.3 times slower than that of Phi and the increased accuracy is relatively low compared to this drop in speed. Since its size approaches a reasonable limit for a consumer grade GPU with 12GB of VRAM it is hard to argue for its utilization when particularly Qwen2.5:7b and Llama3.2:latest perform with similar annotation quality. Phi:2.7b generally performed the worst in every metric excluding speed. This is expected for the low model size, yet it has to be noted that despite the comparatively low scores, it still achieves F1 scores of 0.67 and 0.77 for the abortion annotation task on the 1974 sample. The comparatively lower scores are unique to Phi:2.7b though, as compared to the other models, it is the only model with scores that largely make it a questionable choice for annotation of German political speeches. The high speed might still be useful for preselecting potential cases within a larger dataset, since Phi:2.7b still has the potential of outperforming traditional methods of preselection like keyword selection or traditional classifiers. Gemma3:4b performs neither well nor bad and is situated firmly in the middle on most metrics with its annotation quality being relatively varied. Mistral:7b performs rather well on the annotation of economic topics but does not generate any successful annotations of chunks for the annotation of the reproductive rights topic.

The general quality of all models, Phi:2.7b and Mistral:7b excluded, shows that free, low entry annotation is certainly a possibility for common LLM’s with less than 14b parameters. A NVIDIA RTX-3080-ti with 12gb of VRAM was sufficient to run all included models at high speeds. Annotation of a data frame of 300 annotations with an average of 1000 characters per chunk took about 6 minutes at maximum. Annotation of a larger corpus consisting of 18k chunks took about 8 hours. Running a pc for a couple of days for an even larger dataset is a comparatively cheap expenditure for a research project especially compared to employing and training a student assistant. The manual human annotation for the gold standard took significantly longer with the combined set taking about 2hrs of human annotation time resulting in annotation that was only slightly better, potentially worse (for ambiguous prompting) than LLM annotation. This last part has to be stressed as the student assistant’s annotation quality too dropped for the economic topic annotation task, highlighting that poor instructions resulting in poor annotation does not just affect LLM’s but human annotators also.

For the investigation into potential issues, the results are somewhat inconclusive. The worse performance of all models for the economic dataset implies that a good prompting strategy might be more important than topic prevalence in a model’s training data. This implication follows from the previously mentioned observation that the student assistant annotator performed worse than most models highlighting that the issue is likely found with the prompting strategy instead of the model embeddings. For the economic annotation the Krippendorff’s alpha metric as well as largely random intermodel agreement for single entries further strengthens this interpretation. This observation is in line with the results by Abraham et al. (2025) who previously highlighted similar issues with prompting issues and Brown et al.’s (2025) focus on label entropy. The prompt structure for the economic annotation task followed the structure of the abortion annotation task prompt but where the annotation of discussions around abortion was specific, the annotation prompt for topics of the economy was likely more ambiguous. This might be the case since discussions about abortion and reproductive rights are usually segregated to specific topics. Political discussions generally often include either explicit topics connected to the economy or could be interpreted so. The examples provided within the prompt structure proved valuable for the annotation of discussions connected to abortion but had little to no effect on the annotation quality for the annotation of economic topics. Therefore, the issue most likely arose from the system prompt being too vague for the annotation of economic topics. These results therefore reasonably imply that prompting strategy might often be more important than the assumed topic prevalence within LLM training data. This on the other hand, does not mean that good prompting negates the necessity for a good training set but that a good prompting strategy might potentially yield better results than using a larger more computationally demanding model or even somewhat ameliorate issues with training data.

While this might be the case, the exception of Mistral:7b which fails at annotating any chunk for the abortion topic and performs very well for annotations of economic topics leads to more ambiguous interpretations. This result implies contrary to the performances of the other models, that the assumption that topic prevalence and bias might affect annotation quality might still be justified though only for some models. The fact that the annotation of abortion fails with both submitted samples and that the annotation of economic topics succeeds well for both samples underlines this interpretation. Meanwhile the diachronic investigation shows some indication of historic bias but not in line with the authors initial expectation. As most models had worse annotation quality for the annotation of the more recent samples, a historic bias can be assumed. This bias, while not confirming original expectations is a possible result of the models training data likely not including the more recent political discussions. This points towards a potential issue with overfitting for these smaller models as they might only perform well on the annotation of content previously encountered in the models’ training data. While four annotations resulting in 3600 (excluding null results)11 annotated chunks are relatively little for generalizability this trend is certainly noticeable.

Some additional practical implications follow from these results and interpretations. The results highlight that LLM annotation can be similar in quality to human annotation and that model size unsurprisingly has an effect on annotation quality. While model size has an effect, smaller models can surpass larger models in some cases like with the economic annotation task. Comparing the results of the investigation into different topic annotation quality highlights that researchers should take care when crafting a prompt in the sense that not every topic is created equal. As social constructs the meaning of a topic might vary or be ambiguous, something that a prompting strategy should properly account for. The general performance further implies that training data topic prevalence might be ameliorated utilizing a good prompting structure and few-shot prompting while the example of Mistral:7b stresses that researchers should still expect such issues and test for the right model for each task. This specific example suggests that models even if similar in size and general performance are not equal in terms of specific task performance which invites experimentation with models and a more open-access focused approach to LLM annotation. These results more generally strengthen the case to experiment with different models to identify the most appropriate one for each historical episode or topic instead of getting locked in by a closed access provider of AI services An additional potential annotation strategy was identified during research. If high accuracy is important but full annotation of a sample using a larger LLM is to time costly, the intermodel agreement per annotation highlighted that problematic cases can be systematically identified using this or a similar metric. A research group could thus utilize 2-3 decent performing small models for a quick and dirty first annotation and use a larger model for the annotation of more problematic cases. This could easily be achieved within a single pipeline providing a desirable balance between speed and accuracy.

4.2. Limitations

Both the dataset as well as the prompting strategy necessitate some caution in the interpretation of these results. The dataset was preselected to include sessions that featured a set of keywords connected to abortion. While this preselection was necessary to get any samples containing discussions on the topic, this choice might potentially negatively affect the annotation of economic topics. This does not seem particularly likely as a qualitative overview revealed that every manually screened session of the German parliament had some discussions about the economy, but it is a selective sample, nonetheless. Qualitative preselection of two entire sessions as with the abortion annotation task samples might result in the issues with the economic annotation task being identified as a result of sample selection. Likewise, the poor prompting strategy for the economic annotation might result in a drop in annotation quality that makes comparison between the quality of annotation concerning different topics ill advised. This particular issue is likely to be the more troublesome of the two and a future study could profit from a more thoughtful topic selection. The topic selection in general is problematic as it features a potential interaction between topic prevalence and gendered bias. This issue might be ameliorated with a broader set of topics allowing for more distinctive differentiation of the assumed prevalence of a topic within LLM training data and model bias. Testing for two topics only is arguably appropriate for a proof of concept, but a more thorough approach should focus on more diverse topics as this current limitation undoubtably reduces generalizability. The lack of insight into the training data used to create most LLM is likely to be the most severe limitation of this paper. One of the core assumptions, that certain topics feature within the training data within different proportions is not given, neither is the assumption that the training data leans heavily towards more recent data. Both assumptions are likely given the known sources of training data but the extend of the issue is unclear. A further study might also experiment more with prompting strategy an approach where the model would explain its reasoning as well as a structured output might improve annotation quality further.

5. Conclusion

All expectations towards the advantages of locally executed LLM annotation using small models were confirmed during the investigation. The smaller models enabled local execution resulting in somewhat surprisingly robust annotation quality. This shows that small open-access LLM can effectively and relatively easily be utilized for the annotation of German political speeches even for infrequently discussed topics and for samples from different historical episodes. Few of the suspected disadvantages actually affected the results as only Mistral:7 might have been affected by the low topic prevalence of discussions about abortion. The lower annotation quality for more recent discussions points to a potential issue with the models not containing the more recent discussions within their dataset thus somewhat confirming the assumption of historic bias and pointing towards overfitting. The results largely imply that a good prompting strategy is central to successful annotation and that annotation quality is affected both by model size as well as structure of the data. All results are in line with the previously established literature on the topic while expanding research onto smaller models and a novel investigation into differences between topics. Individual researchers, small teams and even students are likely to profit from the identified advantages but should still maintain a measured approach towards LLM annotation and be aware of potential issues.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

References

- Törnberg, P. Large Language Models Outperform Expert Coders and Supervised Classifiers at Annotating Political Social Media Messages. p. 08944393241286471. Publisher: SAGE Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, [1810.04805 [cs]]. version: 2. [CrossRef]

- Ziems, C.; Held, W.; Shaikh, O.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, D. Can Large Language Models Transform Computational Social Science? 50, 237–291. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Schimanski, T.; Lin, M.; Sachan, M.; Ash, E.; Leippold, M. DIRAS: Efficient LLM Annotation of Document Relevance in Retrieval Augmented Generation, [2406.14162 [cs]]. [CrossRef]

- Savelka, J.; Ashley, K.D. The unreasonable effectiveness of large language models in zero-shot semantic annotation of legal texts. 6. Publisher: Frontiers. [CrossRef]

- Heseltine, M.; Clemm Von Hohenberg, B. Large language models as a substitute for human experts in annotating political text. 11, 20531680241236239. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, L.; Arnal, C.; Marie, A. Prompt Selection Matters: Enhancing Text Annotations for Social Sciences with Large Language Models, [2407.10645 [cs]]. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.A.; Atreja, S.; Hemphill, L.; Wu, P.Y. Evaluating how LLM annotations represent diverse views on contentious topics, [2503.23243 [cs]]. [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Schiebinger, L.; Jurafsky, D.; Zou, J. Word Embeddings Quantify 100 Years of Gender and Ethnic Stereotypes. 115, [1711.08412 [cs]]. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.; Roy, D.; Kabbara, J. Just Put a Human in the Loop? Investigating LLM-Assisted Annotation for Subjective Tasks, [2507.15821 [cs]]. [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, F.; Alizadeh, M.; Kubli, M. ChatGPT Outperforms Crowd-Workers for Text-Annotation Tasks. Publisher: arXiv Version Number: 2. [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice. 69, 99–118. Publisher: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. 3, 305–360. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Harrison, K.; Shklovski, I. The Problems of LLM-generated Data in Social Science Research. 18, 145–168. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

This pattern was identified during a preliminary screening of the dataset. |

| 2 |

Though the tables included within the section include all the model results |

| 3 |

Satisficing in the sense that the researcher is less interested in getting optimal results than in an economic trade-off between immediate cost and result quality. |

| 4 |

Rossi et al. [ 14] note upon a similar issue with LLM as a source of synthetic data. This is also why only a binary annotation task was selected as an appropriate utilization of LLM capabilities. |

| 5 |

This specific wording aims to highlight the socially constructed interpretations of topics and their interpretation as something gendered instead of viewing it through biological essentialism. |

| 6 |

This paper thus more accurately tests the interaction between gendered bias and topic prevalence. A more detailed investigation would have to test each individual aspect. Since this paper is mainly interested in providing a proof of concept than establishing detailed causal mechanisms this exploration will suffice. The largest bottleneck for a more thorough investigation was, in line with one of the previous arguments, the human annotation for the gold standard. |

| 7 |

The author did not encounter a single session of the German parliament in which no single mention of the economy could be identified. It appears to be an issue of quite some importance. |

| 8 |

For the economic annotation prompt see appendix 1 |

| 9 |

All annotations as well as evaluation metrics were calculated on python version 3.12.7 running through Visual Studio Code version 1.104.1. The models were last updated on the 01.09.2025. |

| 10 |

All speed evaluations are reported as multiples of Phi:2.7b as it is the fastest model. A report on absolute time per annotation was deemed unnecessary as this report would only represent the specific hardware constraints and background processes during computing. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 1996 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).