Introduction

Menopause is a universal life transition in women, marking the end of reproductive capacity through the permanent cessation of menstruation. Globally, the age of natural menopause ranges between 45 and 55 years, with ethnic and geographic variations [

1,

2]. While vasomotor symptoms, sleep disturbance, mood changes, and genitourinary problems are widely recognised, their intensity, and impact are mediated by intersecting determinants such as co-morbidities, cultural beliefs, occupational settings, and health system responsiveness [

3,

4].

Singapore, as a high-income nation with advanced healthcare infrastructure, presents a unique context for exploring these issues [

5]. It’s rapidly shifting demographics and multi-ethnic population - Chinese, Malay, Indian, and others; bring diverse cultural and religious beliefs influencing perceptions of health, ageing, and gender roles. Asian perspective of menopause either as a natural process requiring minimal intervention or as a stigmatised marker of ageing and diminished femininity introduces reluctance in discussing symptoms, particularly sexual health, reinforcing silence within families, workplaces, and clinical settings [

6,

7].

Clinical pathways for menopause care in Singapore reflect broader global trends of fragmentation and under-recognition. Although specialist services exist, they are not widely utilised, with primary care often serving as the first point of contact. General practitioners, however, may lack familiarity and confidence in diagnosing and managing menopause. Historical concerns about cancer risk fuel caution and reluctance in prescribing hormonal therapy, despite evolving evidence regarding its safety and effectiveness in appropriate populations [

8].

The intersection of medical comorbidities and menopause introduces an additional layer of complexity [

3]. Chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, and neurological diseases are increasingly prevalent among midlife women in Singapore, in line with global non-communicable disease trends [

9]. Menopause both influences and is influenced by these, altering symptom expression, treatment decisions, and care pathways. Surgical or medically induced menopause, particularly in cancer survivors, intensifies the symptom burden, with clinical encounters complicated by treatment contraindications and absence of tailored, integrated care models [

10].

Despite these challenges, women’s resilience remains a critical mediating factor. Coping strategies rooted in spirituality, exercise, social networks, and reframing menopause as a natural life stage buffers distress and foster adaptation [

11]. However, resilience is unevenly distributed and mediated by socio-economic position, cultural context, and access to supportive environments.

Empirical data capturing the lived experiences of Singaporean women remain scarce, particularly qualitative accounts that illuminate how symptoms, cultural norms, and systemic structures converge. Addressing this gap, the present study employs an equity-oriented qualitative framework to examine the multifaceted experiences of perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause in Singapore. By embedding women’s voices into the evidence base, this study aims to inform clinical practice, workplace strategies, and policy interventions that can collectively reduce disparities and improve health outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

This qualitative study formed part of a larger multi-country study into menopause and midlife health - MARIE WP2A (Menopause and Ageing Research in International Environments – work package 2A), with the Singapore arm focusing on lived experiences of individuals undergoing perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause in Singapore. A qualitative design was selected to capture nuanced, in-depth accounts of symptom experiences, healthcare interactions, and socio-cultural contexts that cannot be adequately represented through quantitative methods. The study followed consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) to ensure transparency and methodological robustness.

Sampling and Recruitment

Participants were recruited purposively to capture heterogeneity across age, menopausal stage, socio-economic position, ethnicity, and healthcare access. Eligibility criteria included: (i) age 18–99 years, (ii) self-identifying as experiencing perimenopause, menopause, or post-menopause— natural, surgical, or medically induced—and (iii) Singapore resident for at least 12 months. Exclusion criteria comprised inability to communicate in English or cognitive impairment precluding informed consent. Recruitment was mainly from clinics in a tertiary hospital with some from community networks. The study received ethical approval from Singhealth IRB (reference 2024/2126). Informed consent, outlining the study purpose, voluntary nature, and confidentiality assurance was obtained electronically before each interview. In total, 18 participants were interviewed.

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between March – May 2025 by trained qualitative researchers with background in women’s health. Interviews took place via secure videoconferencing on Microsoft Teams platform, lasting 45–90 minutes. An interview guide; co-developed with clinical experts and individuals with lived experiences; explored biological symptoms, psychological wellbeing, socio-cultural influences, and healthcare experiences. The guide allowed flexibility to probe emergent issues in depth. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by professional transcribers. Identifying details were removed from transcripts and participants were assigned unique identifiers. Quotes used were anonymised. Reflexive field notes documented contextual factors, non-verbal cues, and researcher reflections.

Analytical Framework

For analysis, the Delanerolle and Phiri Framework [

12], a structured model incorporating four interrelated domains of Biological, Psychological, Socio-cultural, and Health System enabling systematic exploration of symptom profiles and care experiences was used alongside of Braun and Clarke’s lens.

Analysis proceeded in four stages, as described in

Table 1:

Coding was conducted inductively within each domain and iteratively refined to capture both unique and recurrent experiences. Two researchers independently coded an initial subset of transcripts and subsequently discussed code application, domain mapping, and thematic saturation. Discrepancies were resolved, ensuring reflexivity and analytic consensus.

Reflexivity and Positionality

The research team comprised clinicians, public health scientists, and patient partners, with diverse professional and personal experiences of menopause. This positionality informed data interpretation while being critically examined throughout the analytic process. Reflexive discussions addressed potential biases, particularly regarding symptom prioritisation, interpretations of healthcare encounters, and cultural framing of menopause.

Results

Analysis of 18 in-depth interviews (

Table 2) revealed diverse menopausal trajectories shaped by biological, psychological, socio-cultural, and health system factors, with substantial variation in symptom severity and comorbidities. While some participants reported minimal disruption, others experienced multi-domain impact significantly affecting daily functioning, relationships, and occupational capacity.

Cross-cutting themes (

Table 3), such as comorbidity intersections, delayed symptom recognition, and the moderating effect of resilience and social support, recurred across domains.

Biological Domain

Vasomotor and Sleep Disturbance

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) ranged from absent or mild (PID3, PID4, PID17) to severe, sleep-disrupting episodes (PID1, PID6, PID9, PID10). Night-time hot flushes were particularly problematic, often fragmenting sleep and compounding overall fatigue. In some cases, workplace productivity and emotional regulation were adversely affected, with participants adopting cooling strategies, evening showers, and in rare cases, HRT, to mitigate symptoms.

“Suddenly I used to wake up with lots of sweat… sometimes for few hours I was not able to sleep.” (PID9)

“Turn on the fan and air con at the same time in order to sleep.” (PID1)

Several participants (PID10, PID14) developed or worsened vasomotor symptoms years after their final menstrual period, highlighting variability in onset and the potential for late-emerging needs.

Musculoskeletal and Bone Health

Musculoskeletal (MSK) pain and bone density changes were frequent but variably attributed to menopause. In some, MSK pain was the sentinel symptom prompting HRT initiation (PID7), leading to rapid and sustained resolution. Others linked aches to comorbidities such as osteoarthritis (PID16) or previous injuries (PID5), while DEXA-confirmed osteopenia in PID1 and PID7 underscored the role of oestrogen in bone health.

“Hip pain… very deep seated… nothing was helping… went away after HRT.” (PID7)

“DEXA… still osteopenic… trying to get it up.” (PID1)

Weight-bearing exercise and physiotherapy were effective non-pharmacological strategies, though awareness of menopause–bone health links was inconsistent.

Genitourinary and Sexual Health

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) emerged as one of the most consistent burdens across surgical and natural menopause cases. Symptoms included vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, urinary urgency, and recurrent infections (PID1, PID6, PID9, PID16). Some experienced marked improvement with topical oestrogen or tibolone (PID10, PID16), while others faced treatment intolerance or contraindication due to cancer history (PID2, PID8).

“It was very uncomfortable even when I just touch that area… painful because it was so dry.” (PID1)

“The dryness is like… a magic pill…gone [after tibolone].” (PID16)

Under-recognition of urinary and bladder symptoms as menopause-related delayed appropriate care, particularly among those without prior menopause education.

Cross-Cutting Biological Theme – Comorbidity Interaction

Across cases, comorbidities such as autoimmune disease (PID10), Parkinson’s (PID12), ADHD (PID11, PID13), and cancer survivorship (PID2, PID5, PID8, PID17) intersected with menopause to influence symptom profile, care-seeking, and management options. These intersections required nuanced clinical assessment but were frequently overlooked.

Psychological Domain

Mood Disturbance and Emotional Regulation

Mood changes ranged from mild irritability (PID4, PID15) to severe, prolonged low mood with anxiety and intrusive thoughts (PID1, PID11, PID6). For some, symptoms were cyclical, intensifying during perimenopause (PID13). Interpersonal strain, particularly within families, was common, leading to social and emotional withdrawal as a coping mechanism (PID11).

“Small thing would just trigger me… now it can last for days.” (PID11)

“I became anxious… bothersome thoughts… I could not cope as well as before.” (PID1)

HRT improved mood stability in those able to access it (PID13, PID18), while others relied on meditation (PID8, PID17) or lifestyle-based strategies.

Cognitive Change

Brain fog, forgetfulness, and reduced concentration were widely reported (PID1, PID9, PID13, PID16, PID18). These symptoms affected work performance and confidence, prompting compensatory strategies such as note-taking, mental exercises, and mindfulness.

“I could quite easily forget within 5 minutes…” (PID18)

“I can be in the middle of sharing something and I forgot why…” (PID16)

Cognitive impacts were often normalised or attributed to ageing, delaying targeted intervention.

Coping and Resilience

Adaptive coping mechanisms included reframing menopause as a natural life stage (PID15), keeping physically and socially active (PID3, PID15), and spiritual practices (PID4, PID17). Resilience was bolstered by supportive peer or family networks, professional health literacy, and workplace flexibility.

Cross-Cutting Psychological Theme – Professional Paradox

Healthcare professionals (PID6, PID7, PID12) sometimes delayed their own menopause care despite high knowledge levels, reflecting cultural “hormone phobia,” time constraints, and occupational role expectations.

Socio-Cultural Domain

Family and Interpersonal Relationships

Menopause altered family dynamics for many. Spousal withdrawal (PID1) and reduced intimacy linked to GSM (PID9, PID16) affected emotional wellbeing, while others described understanding and accommodation from partners and children (PID2, PID3).

“Husband… withdrew… kids… told to steer clear of mum.” (PID1)

“They just… keep quiet.” (PID2)

Peer Influence and Social Narratives

Peers were both sources of misinformation (PID1, PID13) and support (PID4, PID15). Cancer myths about HRT persisted, deterring uptake even in eligible women. Workplace cultures ranged from silence to active engagement through education programmes (PID18).

“Friends… said HRT could be… cancer inducing.” (PID1)

Stigma and Silence

Participants repeatedly noted the absence of open conversation about menopause (PID13, PID14, PID18). Cultural conservatism and fear of ageing reinforced reluctance to disclose symptoms, especially sexual health concerns.

“People still… don’t want to talk about it.” (PID13)

“Some people… don’t accept the fact they are going through menopause.” (PID14)

Cross-Cutting Socio-Cultural Theme – Community Gaps and Opportunities

The absence of local peer-support groups (PID11) and culturally adapted educational campaigns (PID18) limited collective learning and normalisation. Suggestions included discreet WhatsApp groups, school-based education, and leveraging Asian heritage influencers.

Health System Domain

Access and Pathways

Access varied sharply between public and private sectors. Some had long-term trusted GP relationships (PID9) while others avoided public services anticipating delays or dismissal (PID13). Public specialist services were valued for their comprehensiveness and patient-centred approach (PID18), whereas private care was sometimes seen as commercially driven with less menopause expertise.

“Private… knowledge was very lacking… commercial.” (PID18)

“I had to spend a lot of money to go through the private system.” (PID13)

Clinical Knowledge and Attitudes

Participants identified pervasive knowledge gaps among GPs and non-specialists, including normalisation of heavy bleeding (PID1), symptom dismissal (PID2, PID16), and reluctance to prescribe HRT (PID7, PID13). Even in healthcare settings, women reported being questioned about the necessity and duration of HRT.

“Doctors are not trained… they don’t know how to prescribe hormone therapy.” (PID7)

“The first thing they say is, ‘Why are you on it? When are you going to get off it?’” (PID13)

Continuity and Integration of Care

Positive experiences occurred where continuity existed, such as ongoing GP or specialist relationships (PID9, PID12). Integration of menopause care into chronic disease management was rare but proposed by participants with multimorbidity (PID10, PID16).

Cross-Cutting Health System Theme – Trigger Points for Care-Seeking

For several, participation in the MARIE survey prompted self-recognition of symptom burden and subsequent help-seeking (PID6, PID10). This underscores the potential for structured screening tools to act as entry points into care.

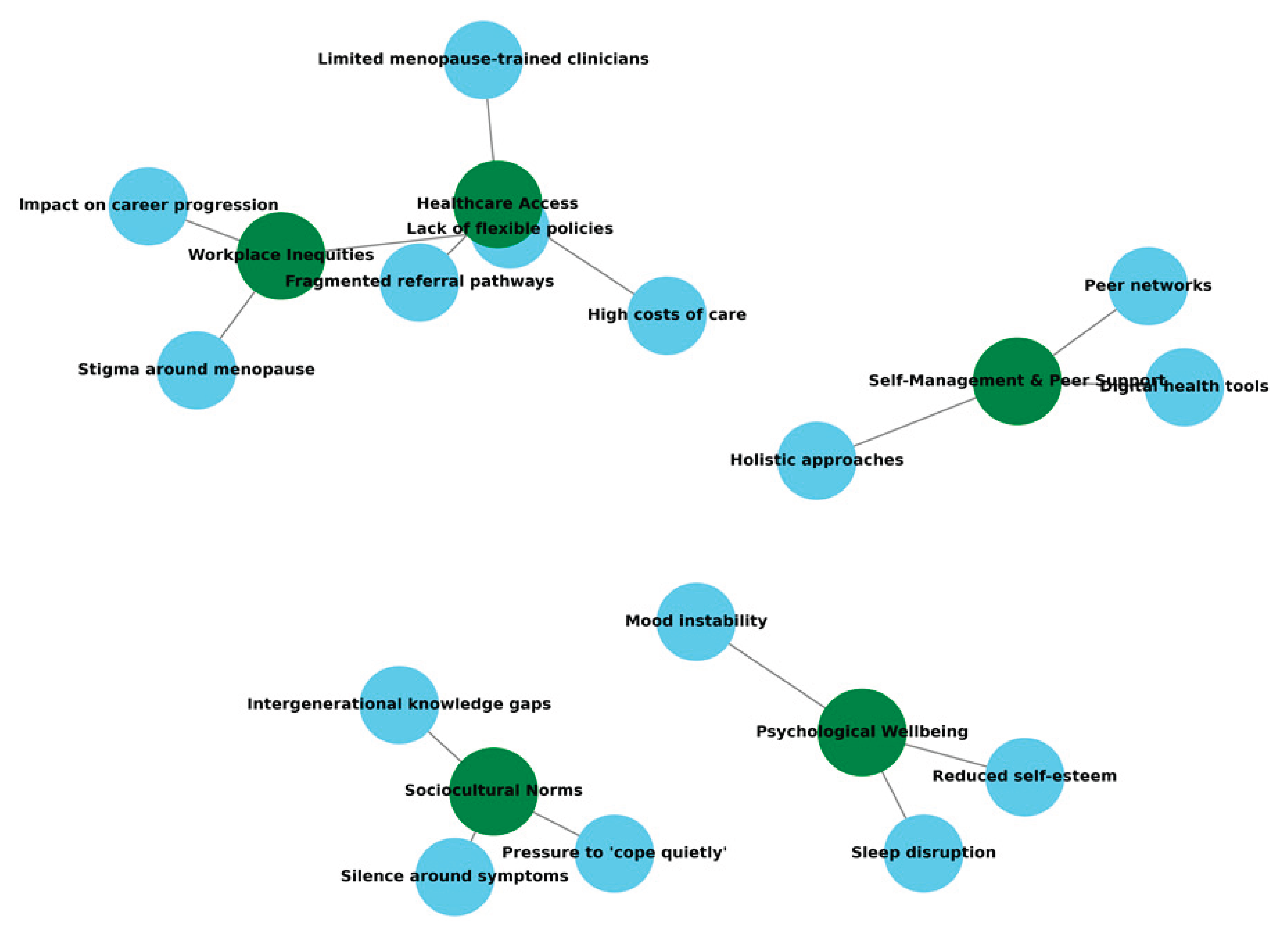

Cross-Cutting Themes Narrative: Intersectionality of Health Status and Menopause

Menopause experiences were profoundly shaped by pre-existing health conditions and surgical histories. Autoimmune disorders (PID10), neurological conditions (PID1, PID12, PID13), chronic metabolic disease (PID14, PID16), and cancer survivorship (PID2, PID5, PID8, PID17) altered symptom expression, complicated assessment and limited treatment options. Surgical menopause cases described more abrupt symptom onset and higher GSM prevalence, though symptom severity varied widely. For many, multimorbidity necessitated integrated care approaches, yet most described fragmented provision (

Figure 1). This intersectional complexity underscores the importance of holistic assessment, where menopause is neither overshadowed by nor isolated from other health conditions.

Systemic and Cultural Silence

Across cases, both institutional and societal silence acted as a structural determinant of delayed recognition and management, fostering reliance on self-navigation and amplifying disparities for those without the means or confidence to advocate for themselves. Cultural conservatism and stigma (PID13, PID14, PID18) limited discussion of sexual health and emotional changes. In healthcare settings, undertrained clinicians often normalised symptoms or dismissed hormonal contributions (PID1, PID2, PID16), leading to missed intervention opportunities. Service invisibility compounded these gaps, with several participants unaware of specialist menopause services (PID10, PID11). This silence extended to workplaces, where only a minority experienced formal menopause policy support.

Discussion

The qualitative analysis of Singapore participants in the MARIE WP2a study revealed a complex interplay between workplace inequities, healthcare access barriers, sociocultural norms, psychological wellbeing, and self-management strategies. Participants described how menopausal symptoms such as vasomotor, cognitive, and psychological disturbances intersected with professional responsibilities in high-pressure environments. Stigma and silence, both in professional and social settings, were recurrent threads, influencing not only help-seeking behaviours but also perceptions of legitimacy regarding symptoms. Thematic connections illustrated a fragmented care landscape in which specialist availability was not well known, costs were prohibitive for some, and referral pathways were inconsistent. These dynamics reinforced reliance on informal networks and self-care approaches, particularly digital tools and peer support, which partially mitigated, but did not eliminate, the cumulative impact on quality of life.

Population Insights

Singapore’s population is characterised by a unique multicultural composition, comprising primarily Chinese (approximately 74%), Malay (13%), and Indian (9%) communities, alongside a smaller proportion of Eurasian and other ethnic groups. This diversity is further shaped by a sizeable expatriate population, adding to the mosaic of languages, cultural norms, and health beliefs. Such heterogeneity has profound implications for menopausal care. Health-seeking behaviours, perceptions of menopause, and openness in discussing symptoms are influenced by culturally embedded values—ranging from the Chinese emphasis on balance and traditional medicine, to Malay and Indian norms around modesty and intergenerational respect. The participant experiences in this study reflected these intersections: some women preferred holistic and herbal approaches rooted in cultural tradition, others prioritised privacy over disclosure even to clinicians, and many highlighted the role of family dynamics in shaping their coping strategies. Tailored interventions that are linguistically accessible, respectful of religious and cultural sensitivities, and inclusive of both biomedical and culturally familiar therapies are essential if care pathways are to be both effective and equitable.

Clinical Impact

The lived experiences described by Singaporean participants highlight a need for embedding women’s narratives into clinical pathways and co-designing clinical guidelines with patients. Menopause care cannot be effectively delivered if it is narrowly defined through biomedical parameters alone; it must also integrate an understanding of the psychosocial and occupational realities patients face [

13]. Lack of alignment of treatment options for menopausal and perimenopausal women amongst healthcare providers leaves women confused and turning to informal networks for information [

14]. Lack of clinician education on appropriate treatment for menopausal symptoms as well as lack of empathy for the women’s suffering highlights a need for training not only in the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of symptoms but also in culturally competent communication that addresses stigma and normalises open discussion [

15]. Standard consultations should incorporate space for exploring work-related impacts, sleep disturbance, and sexual health, while acknowledging patients’ own strategies for symptom control.

Policy Impact

To optimise menopause care in Singapore, policy attention is needed on three fronts: workplace regulation, healthcare provision, and public health education. Singapore currently ranks first in Asia-Pacific for having a low level of gender inequality with more women participating in the workforce including leadership roles. To complement progress in providing women with equal opportunities in the workplace, financial support for caregivers and protection against violence and online harms; there is now a need to acknowledge menopause as a legitimate occupational health issue. Introducing workplace accommodations, such as temperature control, flexible hours, and protected health disclosures will support the women workforce going through menopause [

16,

17]. This is especially important as Singapore faces a shrinking birth rate and should be encouraging more older workers to continue working [

18].

On the healthcare side, incorporating menopause management into healthcare subsidies similar to CHAS (community health assist scheme), and allowing increased insurance coverage will reduce cost and improve access [

19].

Public health campaigns, delivered in multiple languages and tailored to different ethnic and religious groups, would help dismantle stigma and equip women with accurate, culturally relevant information. By aligning policy with clinical realities and population needs, Singapore can set a precedent for equitable and inclusive menopause care.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that menopause in Singapore is not solely a biological event, but an experience profoundly shaped by intersecting cultural norms, workplace environments, healthcare pathways, and individual resilience. While some women navigated the transition with minimal disruption, others experienced multi-domain burdens that compromised health, relationships, and occupational performance. The persistence of stigma and silence within families, communities, and health systems was a critical determinant of delayed recognition and inadequate support.

Policy innovation will help normalise menopause in workplaces, reduce financial barriers to treatment, and deliver multi-lingual, culturally sensitive public health education. Embedding resilience-building strategies and ensuring inclusive, equitable care could transform menopause from a silent struggle into a supported life-course transition.

Ethics Approval

Obtained from Singhealth (CIRB 2024/2126).

Consent to Participate

Obtained.

Consent for Publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

MARIE Consortium: Om Kurmi, Donatella Fontana, Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dassanayake, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Clementine Kanazayire, Jean Damascene Hanyurwimfura, Nwankwo Helen Chinwe, Stella Matutina Isingizwe, Jean Marie Vianney Kabutare, Dorcas Uwimpuhwe, Melanie Maombi, Ange Kantarama, Uchechukwu Kevin Nwanna, Benedict Erhite Amalimeh, Theodomir Sebazungu, Elius Tuyisenge, Yvonne Delphine Nsaba Uwera, Emmanuel Habimana, Nasiru Sani, Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Bertin Ngororano, Victor Archibon, Ibe Michael Usman, Baraka Godfrey Mwahi, Filbert Francis Ilaza, Zepherine Pembe, Clement Mwabenga, Mpoki Kaminyoghe, Brenda Mdoligo, Thomas Alone Saida, Nicodemus E. Mwampashi, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi.

References

- Delanerolle G, Phiri P, Elneil S, et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 2025, 13, e196–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurston RC, Thomas HN, Castle AJ, et al. Menopause as a biological and psychological transition. Nature Reviews Psychology 2025;1-14.

- Bagga SS, Tayade S, Lohiya N, et al. Menopause dynamics: From symptoms to quality of life, unraveling the complexities of the hormonal shift. Multidisciplinary Reviews 2025;8:2025057-57.

- Ang SB, Sugianto SRS, Tan FCJH, et al. Asia-Pacific menopause federation consensus statement on the management of menopause 2024. Journal of Menopausal Medicine 2025;31:3.

- Tan CC, Lam CS, Matchar DB, et al. Singapore's health-care system: key features, challenges, and shifts. The Lancet 2021;398:1091-104.

- Baber, R. East is east and West is west: perspectives on the menopause in Asia and The West. Climacteric 2014;17:23-28.

- Ilankoon I, Samarasinghe K, Elgán C. Menopause is a natural stage of aging: a qualitative study. BMC women's health 2021;21:47.

- Cho L, Kaunitz AM, Faubion SS, et al. Rethinking menopausal hormone therapy: for whom, what, when, and how long? Circulation 2023;147:597-610.

- Lee ES, Lee PSS, Xie Y, et al. The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care: a comparison of two definitions of multimorbidity with two different lists of chronic conditions in Singapore. BMC Public Health 2021;21:1409.

- Franzoi MA, Janni W, Erdmann-Sager J, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up Care After Treatment for Primary Breast Cancer: Strategies and Considerations. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2025;45:e473472.

- Süss H, Ehlert U. Psychological resilience during the perimenopause. Maturitas 2020;131:48-56.

- Delanerolle, G. The Delanerolle and Phiri Theory: The Basis to the Novel Culturally Informed ELEMI Qualitative Framework for Women's Health Research. 2025.

- Davis SR, Pinkerton J, Santoro N, et al. Menopause—Biology, consequences, supportive care, and therapeutic options. Cell 2023;186:4038-58.

- Opayemi, OO. Menopausal transition, uncertainty, and women’s identity construction: Understanding the influence of menopause talk with peers and healthcare providers. Communication Quarterly 2025;73:239-63.

- Barber K, Charles A. Barriers to accessing effective treatment and support for menopausal symptoms: a qualitative study capturing the behaviours, beliefs and experiences of key stakeholders. Patient preference and adherence 2023;2971-80.

- Webster, J. Workplace adjustments and accommodations–Practical suggestions for managing the menopause: An overview and case study approach. In: Exploring resources, life-balance and well-being of women who work in a global context. Springer; 2016:239-54.

- Crawford BJ, Waldman EG, Cahn NR. Working through menopause. Wash UL Rev 2021;99:1531.

- Thang, LL. Population aging, older workers and productivity issues: the case of Singapore. Journal of Comparative Social Welfare 2011;27:17-33.

- Taylor-Swanson L, Kent-Marvick J, Austin SD, et al. Developing a Menopausal Transition Health Promotion Intervention With Indigenous, Integrative, and Biomedical Health Education: A Community-Based Approach With Urban American Indian/Alaska Native Women. Global Advances in Integrative Medicine and Health 2024;13:27536130241268232.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).