1. Introduction

Mental health professionals are particularly vulnerable to intense emotional labor, high empathy demands, and chronic psychological stress (Moore & Cooper, 1996; Chlap & Brown, 2022; Wilczek--Rużyczka, 2023). These job-specific pressures heighten the risk of experiencing adverse psychological outcomes such as burnout and depressive symptoms (Maslach & Leiter, 2016; Bianchi et al., 2021; Huo et al., 2021; Glandorf et al., 2025). During the COVID--19 pandemic, a multinational longitudinal study found that many mental health professionals’ occupational well--being deteriorated over time, particularly among younger and female practitioners (Kogan et al., 2023). In addition, frequent exposure to patient trauma and emotional suffering may lead to compassion fatigue and secondary stress symptoms (Figley, 2002). Studies suggest that insufficient institutional support and work-life imbalance can further exacerbate burnout among health workers (Shanafelt et al., 2015).

Burnout is a state of emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion that develops in response to prolonged occupational stress, negatively influencing motivation, well-being, and job performance (Schaufeli & Buunk, 2003). A frequently observed consequence of burnout is the emergence of depressive symptoms, which may manifest persistent low mood, fatigue, and loss of interest in professional and personal activities (Bianchi et al., 2015). Given the potential overlap between burnout and depressive states, identifying psychological resources that can buffer this relationship is crucial. A systematic review and meta-analysis estimated that nearly 40% of mental health professionals experience high levels of emotional exhaustion, underlining the urgent need for targeted mental health support in clinical workplaces (O’Connor, Muller--Neff, & Pitman, 2018). Previous research has found that burnout not only predicts depression but may also contribute to cardiovascular and physiological health risks in the long term (Melamed et al., 2006). Moreover, burnout has been linked to hopelessness and suicidal ideation in high-stress professions such as medicine (Pompili et al., 2013).

Psychological well-being (PWB) serves as a vital resource and is understood as a multifaceted concept involving purpose in life, independence, control over one’s surroundings, continual growth, self-approval, and positive social connections (Ryff, 1989; Keyes, 2002), psychological well-being has been shown to support resilience, enhance coping, and mitigate the adverse effects of stress (Ryff & Singer, 2008; Diener et al., 2017). Individuals with higher PWB are generally more capable of maintaining emotional stability and effective functioning, even under stressful conditions. Global evidence also points to organizational factors such as poor communication, high administrative burden, and workplace bullying as key risk factors for burnout, while a supportive environment and individual resilience function as important protective resources (Amiri et al., 2024). In healthcare settings, psychological well-being has been shown to promote emotional regulation and protect against stress-related disorders (Awa et al., 2010).

Theoretically, the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory (Hobfoll, 1989) offers a relevant framework for understanding how psychological well-being may function as a protective factor. According to COR theory, individuals strive to acquire, maintain, and protect valuable resources such as time, energy, or psychological strength. Burnout represents a depletion of such resources, while psychological well-being can serve as a buffer, mitigating the psychological consequences of this loss (Hobfoll et al., 2018). COR theory has been widely applied in occupational health research to explain how emotional exhaustion arises when personal and organizational resources are threatened (Halbesleben et al., 2014).

In this context, the stress-buffering model offers a specific lens through which this relationship can be examined. This model posits that the impact of stressors (e.g., burnout) on psychological outcomes (e.g., depression) is moderated by protective psychological variables (e.g., psychological well-being), which can reduce or “buffer” negative outcomes (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Introducing this model allows for a more nuanced understanding of how individual differences in well-being can shape responses to workplace stress. However, despite its theoretical value, empirical studies exploring this moderation effect in mental health professionals are still limited especially in non-Western contexts such as Turkey. Despite its theoretical relevance, the moderating role of psychological well-being has been relatively underexplored in empirical studies on mental health professionals. Most studies in the literature have examined burnout and psychological well-being as separate or linearly related constructs, often treating PWB as an outcome rather than a moderator (Hakanen et al., 2008). Particularly in the Turkish context, empirical evidence on how psychological well-being may buffer the impact of burnout on depression among mental health workers remains limited.

This study aims to clarify the moderating effect of psychological well-being on the connection between burnout and depressive symptoms within mental health professionals. Specifically, the study investigates whether high levels of psychological well-being can weaken the strength of the association between burnout and depressive symptoms. The conceptual framework is grounded in the stress-buffering model and the Conservation of Resources theory. By analyzing a sample of psychologists, guidance counselors, social workers, and psychiatrists actively working in public and private institutions across Turkey, this study contributes to both the international literature and the local context. In doing so, it seeks to offer insights for mental health policy and intervention design aimed at reducing the burden of burnout and promoting psychological resilience in high-risk occupational groups.

2. Method

This study is quantitative research based on a correlational design, aiming to examine the relationships between burnout, psychological well-being, life satisfaction, and depressive symptoms among mental health professionals. The research specifically assessed both the direct relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms, as well as the indirect effects on life satisfaction, while exploring the moderating role of psychological well-being in this context.

Theoretically, it was hypothesized that increased levels of burnout would be associated with higher depressive symptoms; however, psychological well-being would function as a protective factor, weakening this association. In addition, the potential negative impact of burnout on life satisfaction was also investigated. Based on these assumptions SEM was developed to test the proposed relationships.

The model includes the direct effects of burnout on depressive symptoms and life satisfaction, the moderating effect of psychological well-being, and the interaction pathways between the variables. This structural framework was developed within the scope of the buffering model, which posits that protective psychological resources can buffer the negative impact of stress-related variables.

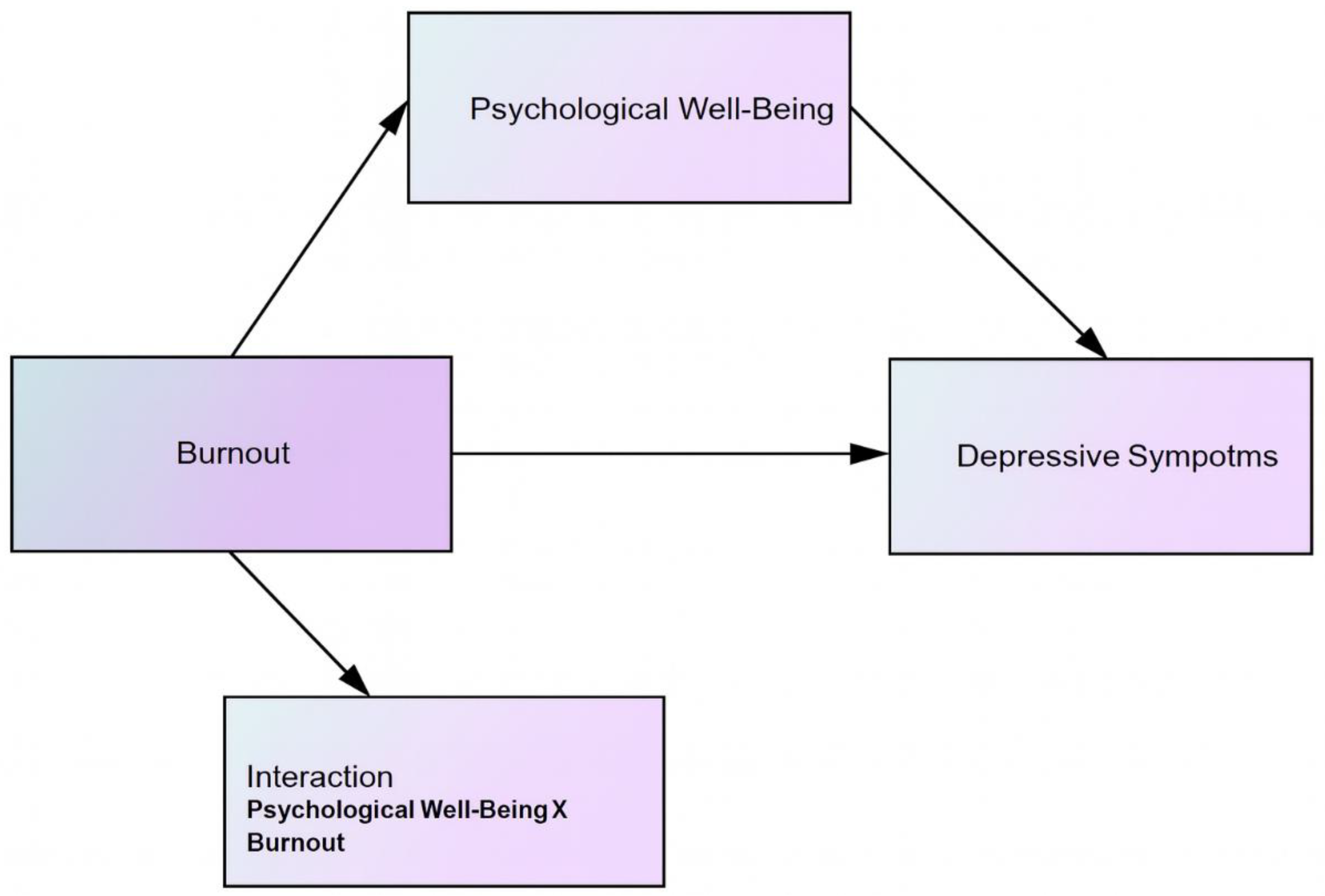

Data was analyzed using AMOS 29 and SPSS 29 software, employing the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. The adequacy of the model fit was assessed through several indicators, including the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). The symbolic representation of the research model is shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Participants

The sample of the study consisted of 607 mental health professionals (psychologists, guidance counselors, social workers, and psychiatrists) working in public and private healthcare institutions across Turkey. Of the participants, 45.3% were female (n = 275), and 54.7% were male (n = 332). In terms of age distribution, 46.6% were aged between 20–30, 43.0% between 31–45, and 10.4% were 46 years or older. Regarding marital status, 83.7% of the participants were single (n = 508), and 16.3% were married (n = 99). In terms of professional distribution, 50.9% were psychologists (n = 309), 33.8% were guidance counselors (n = 205), 9.9% were social workers (n = 60), and 5.4% were psychiatrists (n = 33). All participants had at least one year of professional experience and were actively working with clients or patients. Participation in the study was voluntary.

2.2. Ethics

Prior to data collection, all participants provided written informed consent. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University Ethics Committee (protocol code 2025-01-78/January 2025-1), and the research was carried out in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI): MBI was employed to assess participants’ burnout levels. Originally developed by Maslach and Jackson (1981) and later adapted into Turkish by Ergin (1992), the instrument includes three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment. In the present study, the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha) was calculated as .89.

Psychological Well-Being Scale: The scale was measured using the scale originally developed by Ryff (1989) and adapted into Turkish by Telef (2013). The instrument assesses six core dimensions: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. In the current study, the scale demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .90.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II): Depressive symptoms were measured with BDI-II, developed by Beck et al. (1996) and adapted into Turkish by Hisli (1989). The scale evaluates the severity of depressive symptoms, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .91.

2.4. Procedure

The data collection process took place between January and March 2025 via an online survey. Participants were provided with detailed information regarding the study’s aim, confidentiality assurances, and the voluntary nature of their involvement. Informed consent was obtained electronically. The completion of the questionnaires required approximately 15 to 20 minutes. All research procedures complied with the ethical standards outlined in the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.5. Data Analysis

SPSS 29 and AMOS 29 programs were used for data analysis. Prior to analysis, the data were examined for normality, multicollinearity, and outliers. All variables were standardized (Z-scores), and an interaction term (Burnout × Psychological Well-Being) was created by multiplying the burnout and psychological well-being variables. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) was employed to examine the moderating effect of psychological well-being on the relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms. Model fit was assessed using several indices: χ²/df, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The level of significance was set at p < .05. The interaction effect was visualized through simple slope analysis at low (–1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of psychological well-being.

3. Findings

Table 1 presents the basic sociodemographic distribution of 607 participants working in the field of mental health. Of the participants, 45.3% were female (n = 275) and 54.7% were male (n = 332). Regarding age, 46.6% were between 20–30 years old, 43.0% were aged 31–45, and 10.4% were 46 years or older. This distribution indicates that the sample largely consisted of professionals in young and middle adulthood. In terms of marital status, 83.7% were single (n = 508), while 16.3% were married (n = 99). Regarding professional background, 50.9% of the sample were psychologists (n = 309), 33.8% were guidance counselors (n = 205), 9.9% were social workers (n = 60), and 5.4% were psychiatrists (n = 33). These results demonstrate that the study was conducted with a heterogeneous sample representing various disciplines in the mental health field. Moreover, the fact that the majority of the sample consists of young, single, and actively working professionals provides a meaningful context for examining variables such as burnout and depressive symptoms.

Table 2 shows all relationships within the model reached statistical significance, with p-values less than .001. Burnout emerged as the strongest predictor of depressive symptoms (β = .367). The main effect of psychological well-being was positive (β = .263). The interaction term was also significant (β = .201), indicating that psychological well-being moderates the relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms. The model explained 27% of the variance in depressive symptoms (R² = .27), which is considered a medium to strong explanatory power in psychological research (Cohen, 1988).

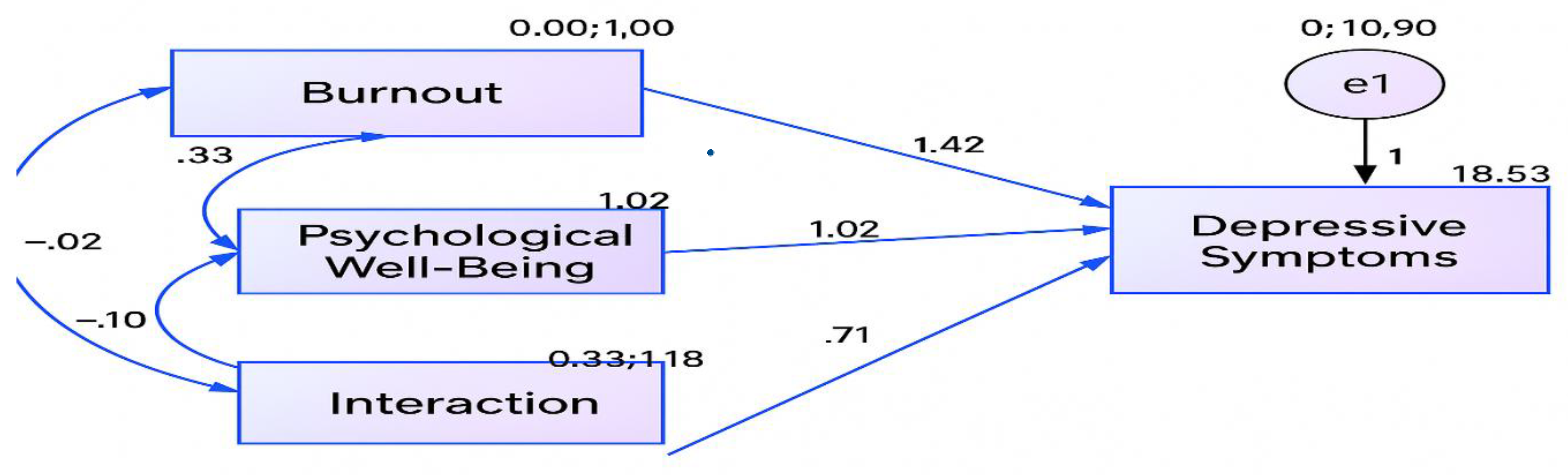

Table 3 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients (r) among burnout, psychological well-being, and the interaction term. Although the correlation between burnout and psychological well-being is positive but weak (.33), the directionality of the interaction term indicates a buffering effect. The inverse associations between the interaction term and the independent variables suggest that multicollinearity is minimal, supporting the validity of the moderation model’s independence assumption. The structural model showing the moderating role of psychological well-being in the relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms is shown in

Figure 2.

In the structural model developed using AMOS, the effects of burnout, psychological well-being, and their interaction term on depressive symptoms were examined. Analysis revealed that each pathway in the model reached statistical significance at the p < .001 level. The path coefficient from Burnout to Depressive Symptoms was β = 1.42, demonstrating a strong and positive influence. This finding suggests that as burnout increases among mental health professionals, depressive symptoms also rise significantly. The path from Psychological Well-being to Depressive Symptoms was β = 1.02, indicating a direct positive effect; however, the interpretation of this effect changes when considered in conjunction with the interaction term.

One of the most critical findings of the model is that the path for the interaction term (Burnout × Psychological Well-being) was both significant and positive (β = 0.71, p < .001). This suggests that psychological well-being significantly moderates the relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms. In other words, the negative impact of burnout on depressive symptoms varies depending on the level of psychological well-being. For individuals with higher psychological well-being, the effect of burnout on depressive symptoms is weaker, whereas for those with lower psychological well-being, this effect is stronger.

The correlation analysis showed an inverse association between burnout and psychological well-being (r = –.33), suggesting that higher levels of well-being are linked to lower levels of burnout. Additionally, the correlations between psychological well-being and the interaction term (r = –.10), as well as burnout and the interaction term (r = –.20), were found to be weak but statistically significant and negative. These results support the theoretical integrity of the model.

The model’s overall explanatory power (R² = .27) shows that 27% of the variance in depressive symptoms is accounted for. This level of explained variance is considered moderately strong in psychological research (Cohen, 1988).

In conclusion, the model confirms the direct effect of burnout on depressive symptoms, while also demonstrating that psychological well-being significantly buffers and moderates this relationship. The role of psychological well-being as a moderator between burnout and depressive symptoms is shown in

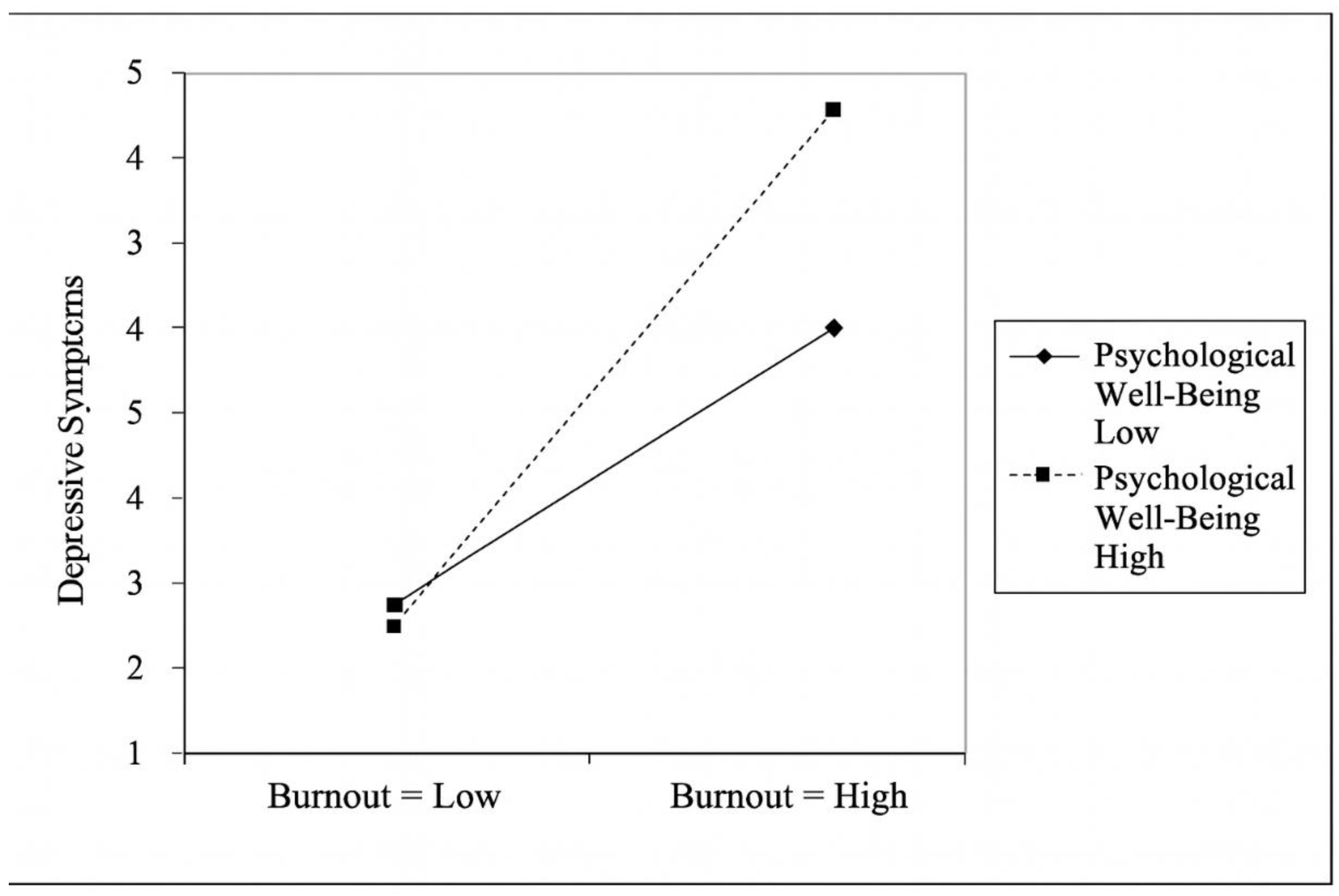

Figure 3.

In the interaction plot, the horizontal axis represents the level of burnout (low to high), while the vertical axis represents the level of depressive symptoms. The two lines reflect low and high levels of psychological well-being. When burnout is low, depressive symptoms remain relatively low in both groups, with minimal differences between them. As burnout increases, depressive symptoms also rise in both groups; however, the rate of increase varies depending on the level of psychological well-being. Among those with high psychological well-being, the increase in depressive symptoms is slower and more limited. In contrast, among individuals with low psychological well-being, depressive symptoms rise much more rapidly as burnout intensifies. This clearly illustrates that psychological well-being weakens the impact of burnout on depressive symptoms.

4. Discussion

This research explored how psychological well-being may alter the strength or direction of the relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms in mental health professionals. The findings revealed that burnout significantly and positively predicts depressive symptoms; however, this relationship is moderated by individuals’ level of psychological well-being. Thus, psychological well-being weakens the impact of burnout on depressive symptoms. The significant interaction (β = .201, p < .001) confirms the moderation effect. Those with high psychological well-being reported fewer depressive symptoms under burnout, confirming its buffering role.

These results align with the theoretical framework proposed by Maslach and Jackson (1981), emphasizing the long-term association between the core components of burnout emotional exhaustion, reduced personal accomplishment, and depersonalization and depressive symptomatology. One limitation of the current model is that it treats burnout as a unidimensional construct. However, MBI comprises three distinct dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. Future research could benefit from analyzing these subdimensions separately, as they may differentially predict depressive symptoms or interact with psychological well-being in unique ways.

Mental health professionals are prone to burnout due to emotional labor and constant empathic demands (Schaufeli & Buunk, 2003). The strong direct effect of burnout on depressive symptoms observed in this study supports the structural linkage proposed in the literature.

The moderating effect of psychological well-being is also consistent with conceptualizations by Keyes (2002) and Ryff (2014), which highlight positive functioning and a sense of meaning as critical components of mental health. Elevated psychological well-being has been associated with greater emotional resilience, enhanced coping capacity, and diminished impact of stressors and negative life events (Diener et al., 2017). Recent findings suggest that well-being interventions not only promote emotional regulation but also enhance neurocognitive flexibility, enabling individuals to disengage from negative affective loops triggered by occupational stressors (VanderWeele et al., 2020). Moreover, mindfulness-based interventions in nurses have been found to reduce burnout and improve resilience, suggesting that interventions targeting well-being can have meaningful impact (Dou et. al., 2025). Within this framework, psychological well-being may serve as a buffer mitigating the negative psychological consequences of occupational burnout.

The slope differences observed in the graphical analyses further illustrate that the increase in depressive symptoms associated with burnout varies as a function of psychological well-being. This finding was evident in the plotted interaction effect, where the burnout-depression link was substantially weaker for individuals scoring high on psychological well-being. According to Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 1989), psychological well-being enhances internal resources and reduces burnout effects. Psychological well-being can be conceptualized as a key protective resource in managing stress, promoting job satisfaction, and preventing emotional exhaustion among mental health professionals.

These findings highlight implications at both clinical and organizational levels. Interventions aimed at alleviating depressive symptoms should not only focus on reducing burnout but also actively foster psychological well--being. Institutional strategies such as supervision, self--care initiatives, mindfulness training, and positive psychology interventions may enhance psychological well--being, thereby buffering the detrimental effects of burnout (Hülsheger et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2023; Tement et al., 2023). Institutions may integrate psychological well--being screening tools into regular supervision or clinical evaluation processes to detect early signs of emotional vulnerability and guide timely support. However, evidence from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis (Strudwick et al., 2023) indicates that screening alone (i.e., providing feedback or advice) does not reliably improve employee mental health, unless it is paired with facilitated access to interventions. A meta--analysis of resilience training in nurses showed significant reductions not only in burnout (SMD ≈ –1.01) but also in depression, stress, and anxiety (SMD ≈ –0.43) (Zhai, 2021). Another meta-analysis on the relationship between resilience and burnout in nursing populations found a moderate inverse correlation (r ≈ –0.41), supporting the idea that higher resilience goes hand in hand with lower burnout (Castillo-González et. al., 2024).

Notably, psychological well-being has been positively associated with reduced cortisol reactivity in occupational stress contexts, suggesting a potential physiological mechanism through which buffering occurs (Boehm et al., 2018). Additional strategies such as psychoeducational workshops, resilience training, and structured self--care modules—shown to have modest positive effects in health and social service workplaces—can be embedded into professional development curricula to strengthen coping in high--demand environments. Indeed, meta-analyses indicate that resilience training among nurses reduces burnout, depression, stress, and anxiety symptoms (SMD ~ –1.01 for burnout) (Zhai et al., 2021). Moreover, resilience has been found to buffer the negative psychological outcomes of burnout in healthcare workers in Sri Lanka (Baminiwatta et al., 2025). Moreover, organizational commitment to psychological safety and meaningful recognition has been linked to enhanced well-being and lower turnover among human service professionals (Kowalski & Loretto, 2017).

These results suggest that organizations should consider integrating regular psychological well-being assessments into routine occupational health monitoring to detect early signs of vulnerability. Despite these contributions, the study is subject to certain limitations. Due to its cross-sectional design, causal inferences remain tentative. Furthermore, reliance on self-report measures introduces potential bias. While Z-transformation (Z-score standardization) enabled standardization of variables and reduced multicollinearity in the interaction term, it may have influenced the interpretation of results, especially concerning established clinical thresholds. For example, in the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), scores above 20 typically indicate moderate to severe depressive symptoms; however, due to standardization, it is unclear how many participants reached clinical levels of depression. Although this approach enhances comparability, it may obscure meaningful clinical thresholds for depressive symptoms or burnout severity. Future studies may consider reporting both raw and standardized scores to enhance clinical interpretability. Online data collection may have excluded those with limited internet or tech access. This could affect the representativeness of the sample and introduce self-selection bias. Another limitation is the lack of subgroup analyses across variables such as professional group (e.g., psychologist, psychiatrist), gender, or age. These factors may moderate the effects observed in the model. For instance, younger professionals may experience burnout differently than more experienced colleagues, and institutional factors may vary across professional roles. Incorporating multi-group SEM or moderation by these demographic variables could yield more nuanced insights. Future research could explore whether the strength of the moderation effect differs by profession, gender, or years of experience.

Future research should use longitudinal or experimental designs and explore profession-specific models and gender or experience-based moderation effects. Mixed-methods approaches (adding qualitative data) can also deepen insight into the lived experience of burnout and well--being in mental health professionals. Longitudinal evidence from Finnish dentists shows that burnout predicts depressive symptoms and life dissatisfaction over time (Hakanen & Schaufeli, 2012). Moreover, given findings that burnout is associated with a depressive interpretation style (Bianchi and da Silva Nogueira, 2019), future studies might examine whether interpretive biases moderate or mediate the relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study underscores the critical role of psychological well-being in moderating the detrimental effects of burnout on depressive symptoms among mental health professionals. These findings provide a strong empirical foundation for the development of targeted mental health policies and interventions at both the individual and institutional levels. As psychological well-being emerges as both a protective and modifiable factor, its inclusion in workplace mental health programs may not only reduce depression risk but also improve long-term professional sustainability and resilience in emotionally demanding professions.

Author Contributions

FB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data collection, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft; İO: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; HKÇ: Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing; GFÇ: Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing; MS: Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing.

Funding

The study has no funding.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Approved by the University Ethics Committee (protocol code 2025-01-78; January 2025-1). All participants provided electronic informed consent.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Amiri, S.; Mahmood, N.; Mustafa, H.; Javaid, S. F.; Khan, M. A. Occupational Risk Factors for Burnout Syndrome Among Healthcare Professionals: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health 2024, 21(12), 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, W. L.; Plaumann, M.; Walter, U. Burnout prevention: A review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling 2010, 78(2), 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baminiwatta, A.; Fernando, R.; Gadambanathan, T.; Jiyatha, F.; Maryam, K. H.; Premaratne, I.; Kuruppuarachchi, L.; Wickremasinghe, R.; Hapangama, A. The buffering role of resilience on burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress among healthcare workers in Sri Lanka. Discover Psychology 2025, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Schonfeld, I. S.; Laurent, E. Burnout-depression overlap: a review. Clinical psychology review 2015, 36, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; da Silva Nogueira, D. Burnout is associated with a depressive interpretation style; Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress; Stress and Health, 2019; Volume 35, 5, pp. 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, R.; Verkuilen, J.; Schonfeld, I. S.; Hakanen, J. J.; Jansson-Fröjmark, M.; Manzano-García, G.; Laurent, E.; Meier, L. L. Is burnout a depressive condition? A 14-sample meta-analytic and bifactor analytic study. Clinical Psychological Science 2021, 9(4), 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, J. K. Positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular disease: Exploring mechanistic and developmental pathways. Social and personality psychology compass 2021, 15(6), e12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlap, N.; Brown, R. Relationships between workplace characteristics, psychological stress, affective distress, burnout and empathy in lawyers. International Journal of the Legal Profession 2022, 29(2), 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-González, A.; Velando-Soriano, A.; De La Fuente-Solana, E. I.; Martos-Cabrera, B. M.; Membrive-Jiménez, M. J.; Lucía, R. B.; Cañadas-De La Fuente, G. A. Relation and effect of resilience on burnout in nurses: A literature review and meta-analysis. International nursing review 2024, 71(1), 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, C.; Pignata, S.; Bezak, E.; Tie, M.; Childs, J. Workplace interventions to improve well-being and reduce burnout for nurses, physicians and allied healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMJ open 2023, 13(6), e071203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Heintzelman, S. J.; Kushlev, K.; Tay, L.; Wirtz, D.; Lutes, L. D.; Oishi, S. Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne 2017, 58(2), 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Lian, Y.; Lin, L.; Asmuri, S. N. B.; Wang, P.; Durai, R. A/P R. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout, resilience and sleep quality among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Nurs 2025, 24, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C. R. Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2002, 58(11), 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glandorf, H. L.; Madigan, D. J.; Kavanagh, O.; Mallinson-Howard, S. H. Mental and physical health outcomes of burnout in athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2023, 18(1), 372–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Ahola, K. The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress 2008, 22(3), 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J.; Schaufeli, W. B. Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. Journal of affective disorders 2012, 141(2-3), 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B.; Neveu, J. P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S. C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management 2014, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 1989, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J. P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5 2018, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Ning, Y.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Y. Burnout and its relationship with depressive symptoms in medical staff during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 12, 616369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U. R.; Alberts, H. J.; Feinholdt, A.; Lang, J. W. Benefits of mindfulness at work: the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. The Journal of Applied Psychology 2013, 98(2), 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2002, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, C. S.; Garcia-Pacheco, J. A.; Rebello, T. J.; Montoya, M. I.; Robles, R.; Khoury, B.; Kulygina, M.; Matsumoto, C.; Huang, J.; Medina-Mora, M. E.; Gureje, O.; Stein, D. J.; Sharan, P.; Gaebel, W.; Kanba, S.; Andrews, H. F.; Roberts, M. C.; Pike, K. M.; Zhao, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J. L.; Reed, G. M. Longitudinal Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Stress and Occupational Well-Being of Mental Health Professionals: An International Study. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 26(10), 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, T. H. P.; Loretto, W. Well-being and HRM in the changing workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2017, 28(16), 2229–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. E. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior 1981, 2(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M. P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, S.; Shirom, A.; Toker, S.; Berliner, S.; Shapira, I. Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: Evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychological Bulletin 2006, 132(3), 327–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K. A.; Cooper, C. L. Stress in mental health professionals: A theoretical overview. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 1996, 42(2), 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.; Muller Neff, D.; Pitman, S. Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. European psychiatry: the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists 2018, 53, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Innamorati, M.; Venturini, P.; Masotti, V.; Lamis, D. A.; Erbuto, D.; Girardi, P. Burnout, hopelessness and suicide risk in medical doctors. Psychiatry Research 2013, 210(1), 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1989, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 2014, 83(1), 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 2008, 9(1), 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Buunk, B. P. Schabracq, M. J., Winnubst, J. A. M., Cooper, C. L., Eds.; Burnout: An overview of 25 years of research and theorizing. In The handbook of work and health psychology; John Wiley & Sons, 2003; pp. 383–425. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt, T. D.; Boone, S.; Tan, L.; Dyrbye, L. N.; Sotile, W.; Satele, D.; Oreskovich, M. R. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Archives of Internal Medicine 2015, 172(18), 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strudwick, J.; Gayed, A.; Deady, M.; Haffar, S.; Mobbs, S.; Malik, A.; Akhtar, A.; Braund, T.; Bryant, R. A.; Harvey, S. B. Workplace mental health screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational and environmental medicine 2023, 80(8), 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telef, B. B. Psikolojik İyi Oluş Ölçeği: Türkçeye uyarlama, geçerlik ve güvenilirlik çalışması. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 2013, 28(3), 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Tement, S.; Ketiš, Z. K.; Miroševič, Š.; Selič-Zupančič, P. The Impact of Psychological Interventions with Elements of Mindfulness (PIM) on Empathy, Well-Being, and Reduction of Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(21), 11181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T. J.; McNeely, E.; Koh, H. K. Reimagining Health-Flourishing. JAMA 2019, 321(17), 1667–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek-Rużyczka, E. Empathy and resilience in health care professionals. Acta Neuropsychologica 2023, 21(4), 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Ren, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Su, X.; Feng, B. Resilience training for nurses: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 2021, 23(6), 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).