1. Introduction

The beetle family Coccinellidae (Coleoptera) is globally recognized for its striking colors but is also known worldwide for its significant impact on ecosystems and its role in pest control, sparking great interest both scientifically and in agro-industrial applications [

1]. Coccinellids are natural predators, especially of aphids and scale insects, although some species are phytophagous or mycophagous [

2]. Many species exhibit complex trophic interactions, including intraguild predation (IGP) [

3] and intra-specific cannibalism [

4].

Reproduction begins once the adult female lays her eggs, in the tribe Coccinellini usually in clusters near a colony of aphids or other food source [

5]. The eggs are bright yellow or orange and hatch within three to seven days, primarily depending on the temperature to which they are exposed [

6]. The larvae go through four larval instars before reaching the pupal stage. Both eggs and pupae are immobile, do not actively defend themselves, and they are thus more prone to be cannibalized than larvae [

7]. Older ladybird larvae may also attack and feed on smaller larval instars [

8]. Adults and larvae of

Coleomegilla maculata and

Propylea quatuordecimpunctata attacked eggs, 1st and 2nd instars of

H. axyridis [

9]. It may seem that a selection for faster growth and development will minimize the risk of being cannibalized as an egg or a small larva, but it can increase the risk of being cannibalized as a pupa by slower conspecific 4

th instar larvae.

Besides cannibalism, simple competition for food can be a driver for faster development. But this competition will be strong only when food is scarce, and thus the fast development would lead to smaller adults.

One form of intraspecific communication detected in insects provides protection of eggs and young larvae against cannibalism and IGP by older larvae or simply against competition for limited food source. It is known as the Oviposition-deterring pheromone (ODP) or allomone. ODP in fruit flies consists of chemicals released by adult individuals that affect female decisions regarding egg-laying, leading other females to avoid depositing eggs in the same fruit [

10].

Similar effects have been detected in aphidophagous predators

Coccinella septempunctata and

Chrysopa oculata [

11]. In Coccinellidae, ODP are deposited by larvae. Females do not lay eggs or lay less eggs in presence of either conspecific or heterospecific larval tracks. This effect persists from one day to one month [

12]. Chemical analyses of the compounds responsible for this communication included short-chain hydrocarbons and esters [

13]. Initial studies on this phenomenon in the invasive harlequin ladybird,

Harmonia axyridis, also demonstrated that chemical markers could deter females from laying eggs, thus reducing resource competition and cannibalism among larvae [

14].

Population dynamics of systems with ladybirds and aphids can be better specified as a metapopulation model of aphid-ladybird interactions than by classical Lotka-Volterra models of predator-prey relationship [

15]. Selection should favor mechanisms that enable predators to avoid reproducing in patches with insufficient prey and those already occupied by predators [

16]. Optimization of the oviposition sites in systems with large generation times ratio (aphids having extremely short life cycle, compared e.g. to coccids [

17] then favor using compounds deposited by conspecifics as a clue to search for an alternative food patch [

18].

Exposure of either larvae or adults of

Cheilomenes sexmaculatus to IGP risk by

H. axyridis decreased either adult or offspring body size [

19]. As mentioned above, pupae are also in risk of IGP and cannibalism. We expect that ODP may also influence larval developmental rate and resulting body size. Larvae could either accelerate their development to avoid competition for food or to decelerate it not to become defenseless pupae in presence of voracious larvae.

Population density should be important in both competition and cannibalism; and truly, cannibalism increased with larval density in

Cycloneda sanguinea and

H. axyridis, suggesting that not all attacks on conspecifics are driven by hunger [

20].

This research investigated whether exposure to larval tracks and the intensity of physical larval presence would affect the developmental time of H. axyridis larvae and body mass of resulting adults. The development times of the last larval instar and the pupal stage were measured in the presence of diverse amounts of larval tracks pheromone and at various population densities.

2. Materials and Methods

We maintain a laboratory stock of the ladybird

H. axyridis named Stáňa, which belongs to the colour form

novemdecimsignata (otherwise known as

succinea) at 25°C, 16:8 LD [

21]. We feed them with frozen

Ephestia eggs and aphids

Acyrthosiphon pisum reared on

Vicia faba and provided them with water in cotton pads and corrugated paper for oviposition. Eggs were separated from the adults and larvae were reared in groups of five in 10 cm diameter Petri dishes. Water and food were renewed once a day until the larvae reached the third instar. Then we checked them twice a day (once every 12 hours) until larvae reached the fourth instar. Then the larvae of the same developmental stage (within a 12-hour interval) were separated into new clean Petri dishes with sufficient water and food.

From the moment when larvae reached the fourth instar, they were separated into six treatments. Three treatments were so called "clean" (C) and three were called "pheromone" (P). The individuals of the clean treatments were moved to a new clean dish daily at the same time to avoid accumulation of pheromones. The larvae of the pheromone treatments remained in the same dish until pupation to allow accumulation of pheromones. In both, water was changed and frozen Ephestia eggs ad libitum were replenished each day to minimize cannibalism. Within these groups, three treatments were set up with different larval densities per 15 cm Petri dish: 1 larva living alone (C1, P1), 4 larvae living in a group (C4, P4), and 8 larvae living in a group (C8, P8).

The developmental times of the fourth instar and of the pupa were measured in 12-hour intervals and recorded for each individual. The experiment was replicated three times within two months, resulting in 354 larvae measured. Within one day after each adult emerged from pupa, the body mass was measured to the precision 0.1mg. A total of 324 adult individuals from all treatments were examined.

The measured variables were analyzed using two-way ANOVA and Fisher LSD tests; standard significant difference value of p<0.05 was considered.

3. Results

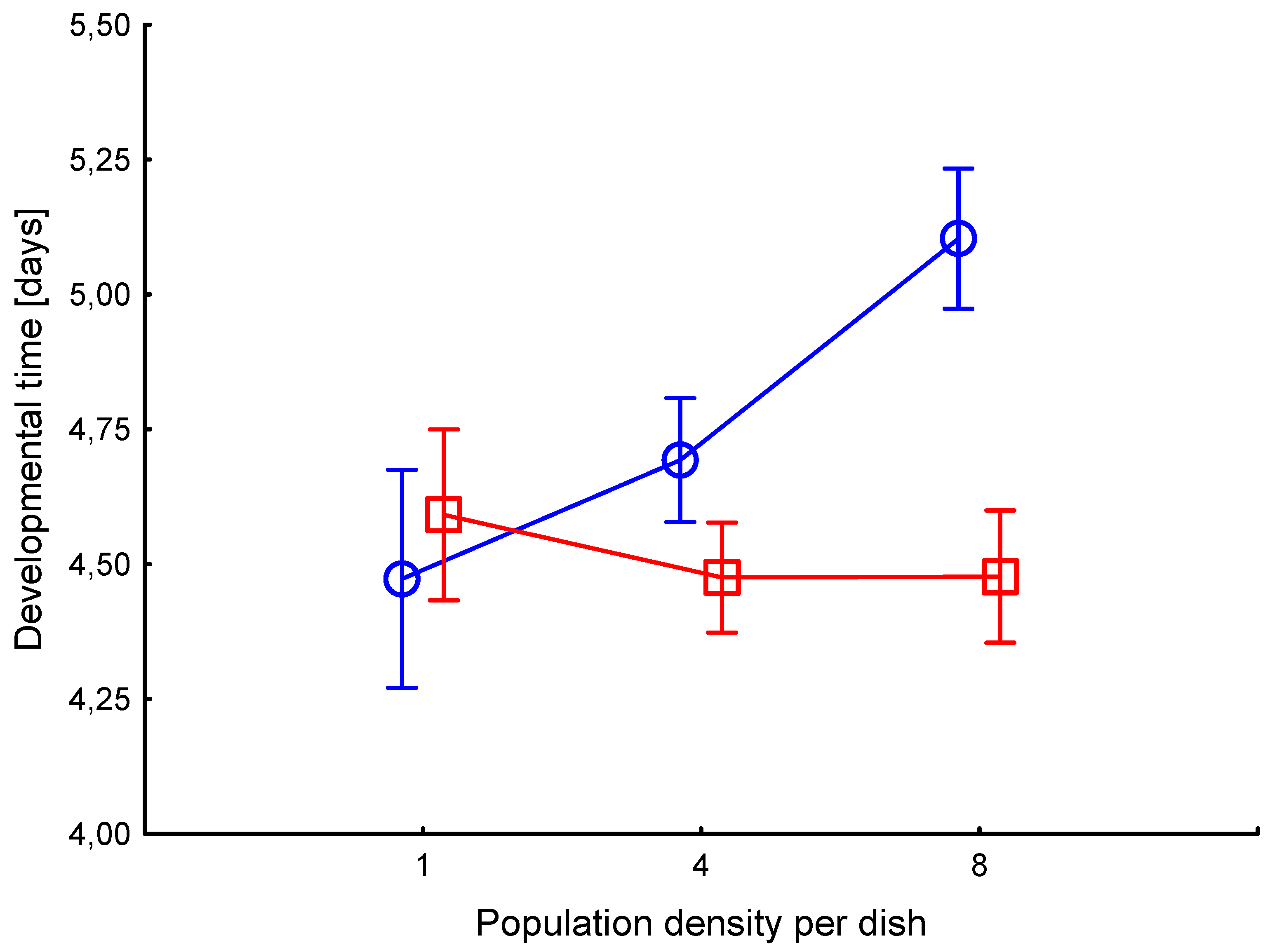

3.1. Developmental time

Developmental times of the 4

th instar highly differed among the six treatments (

Figure 1). Larval developmental time was shorter in P than in the C treatments (F

1,348=16.8, p<0.00001). High density of individuals resulted in longer larval development (F

1,348=7.8, p=0.0005), mainly in the C treatment, as shown by strong interaction (F

2,348=12.2, p<0.00001). Developmental time in treatment C8 was longer than in all other treatments (p<0.00001), development of C4 was longer than that of P4 (p=0.006), but it was not different from C1 (p=0.06). Such a pattern suggests that a high number of physical encounters between larvae in clean environment prolongs their development, decreasing the risk of predation in the pupal stage. But high amount of pheromones from larval tracks reverse the effect, keeping the development as fast as in solitary larvae.

There was no significant difference in the pupal developmental time between the six treatments (F2,348=1.40, p=0.23), suggesting that neither group density nor pheromone action affected development time from pupa to adult. In all cases, the average time was 5.5 days.

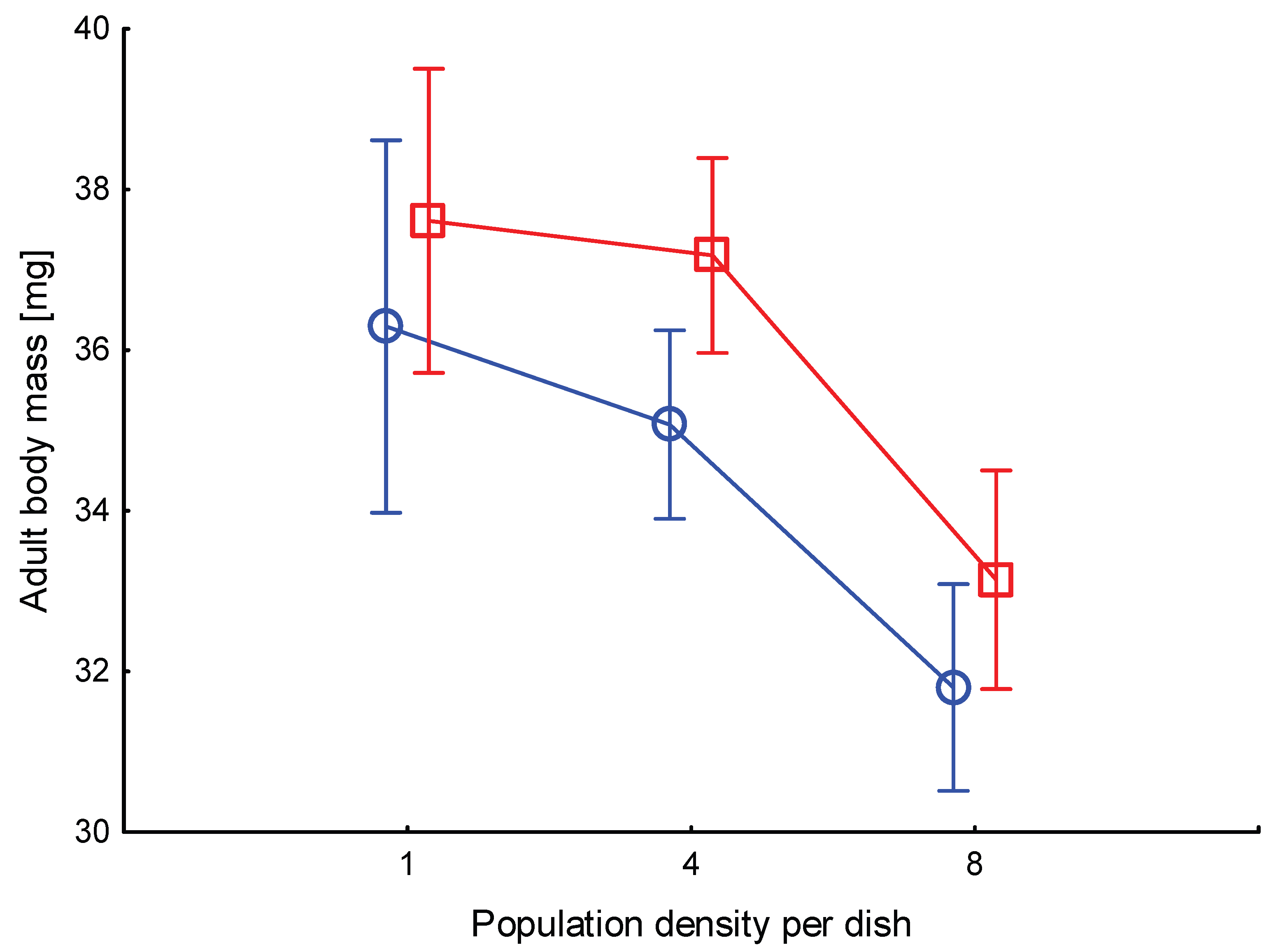

3.2. Adult body mass

Body mass of one day old adults highly differed among the six treatments (

Figure 2) Body mass was higher in P than in C treatments (F

1,318=5.7, p=0.017). High density of individuals resulted in smaller adults (F

1,318=20.7, p<0.00001), similarly in C and P treatments (interaction F

2,318=0.21, p=0.81). Body mass in treatment C8 was lower than in C1 and C4 (p<0.001), in P8 lower than in P1 and P4 (p<0.00001). It was not different between C1 and P1 (p=0.39), neither between C8 and P8 (p=0.16). Such a pattern suggests that a high number of physical encounters between larvae decreases the body mass of resulting adults, regardless of pheromone amount, probably due to lower food intake following stress.

4. Discussion

4.1. Developmental time

When population density increased to the highest level, while the amount of putative pheromones was kept low (treatment C8), developmental time of the last instar larvae – the most voracious and cannibalistic – significantly increased. Unexpected frequent encounters with conspecifics seemed to delay metamorphosis to avoid becoming a defenseless pupal stage in the presence of many predators. Similar results were found in two Russian populations of

H. axyridis [

22], where an increase in population density (1, 5, and 10 per dish) led to an increase in development time. Other factors had a stronger effect than population density, with long photoperiod (18h) prolonging development, and diet consisting of aphid

Myzus persicae accelerated development in comparison to

Ephestia eggs diet.

A possible explanation for the differences in development times related to density and pheromones could be that high levels of stress from physical interactions and the presence of other individuals (competitors) may force individuals to compete for available resources (food, space, shelter). In this situation, individuals may prioritize short-term survival over development, taking more time to reach the pupal stage. This explanation was suggested for

Locusta migratoria (Orthoptera: Acrididae) and

Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae), where some of the effects of increased population density could produce immune responses and signs of nutritional deficiencies that affect developmental time [

23,

24].

The pupal development lasted 5.5 days in all treatments which corresponds to the values found in the literature, where the time spent in the pupal stage was 5.3 days at 24°C [

25]. There was no delay either due to high density of larvae or pheromones deposited – pupae developed as fast as possible. They do not perceive the two types of information due to their limited sensory capacity, and they do not remember the situation from their previous life.

4.2. Adult body mass

Body mass of newly hatched adults, which is mostly dependent on mass gain during the last larval instar, also decreased only at the highest level of larval population density (treatments C8, P8). Similar results were found in the two Russian populations [

26], where an increase in population density led to a significant decrease in body mass, but only in the treatment fed with aphids. Density-dependent factors, such as cannibalism and food availability, negatively affected larval development in both native and invasive Russian

H. axyridis populations, leading to smaller adults. Because food supply was not limited in our experiments, and it consisted of

Ephestia eggs, we consider the stress of frequent encountering the other larvae responsible to lower food ingestion or utilization.

Some authors also propose that competition for space indirectly affects the ability to feed and move efficiently. This trend was observed in flies Musca domestica, Drosophila melanogaster, the tropical butterfly Bicyclus anynana, and moth Lymantria dispar [27-31]. In all the studied cases, the population density was manipulated, finding that an increase in population density directly affects stress levels, producing a 10-45% decrease in the body mass of individuals, as well as other factors such as fertility and the effectiveness of sexual reproduction.

Ladybird females are always heavier than males [

32], what was not distinguished in our samples. However, we found much higher average fresh mass than that reported for

H. axyridis 28.3 ± 2.8 mg at long photoperiod females fed with

M. persicae [

33]. This difference suggests that food stress was not the direct driver of differences among our treatments.

However, the effects of density and pheromones were not positively combined. Perception of larval tracks (P treatments) increased the adult body mass, meaning that larval feeding and utilizing the food for growth was improved compared to clean environment (C treatments). Because each larva produces and then feels its own pheromones, it seems to be calmed from a possible stress in their presence. Known, already visited vegetation can be safer than unknown one.

4.3. General discussion

The trends found in this study caused by population density and deposited pheromones in both development time and body mass in H. axyridis warrants further investigation. Future studies should conduct a detailed analysis by increasing population density even further and observing changes in developmental time, body mass, and survival rate to determine a possible self-regulation mechanism of the species field populations at high densities. However, the effect of high larval density can be diminished in nature, where physical contact or encounters between individuals may cause them to take opposite paths and directions to avoid interaction and keep distance from each other.

Considering the scenario where an individual enters the pupal stage while surrounded by individuals in the larval stage, this individual would be defenseless and immobile, and could be cannibalized. Both the stress caused by the encounters leading to inefficient food intake and utilization, and endeavour to avoid defenceless stage are logical interpretations of our results. High-density populations may begin to self-regulate due to negative effects on growth and survival, reducing the risk of overpopulation. The presence of pheromones without physical contact with larvae could induce behaviors or physiological responses that accelerate development due to the activation of species regulation mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

Larvae of ladybirds seem to react both to their density and to the presence of larval tracks. High larval density had negative effects on developmental rate and subsequent adult body size. Presence of the tracks stabilized high developmental rate and increased body size. Thus, the compounds present in the tracks, previously known as oviposition deterring pheromone, can be also considered as development enhancing pheromones.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, writing—review and editing, O.N.; investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data in Excel tables are kept by the authors and will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

Chat GPT was used for language correction in the final version. We thank Selgen Company in Chlumec and Cidlinou, Czech Republic, for providing seeds of Vicia faba for free.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hodek, I.; van Emden, H.F.; Honěk, A. Ecology and Behaviour of the Ladybird Beetles; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, United Kingdom, 2012; 561p. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona, H.E.; Zwick, A.; Li, H.-S.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Pang, H.; Hartley, D.; Jermiin, L.S.; Nedvěd, O.; Misof, B.; Niehuis, O.; Ślipiński, A.; Tomaszewska, W. Molecular phylogeny reveals food plasticity in the evolution of true ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae: Coccinellini). BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedvěd, O.; Fois, X.; Ungerová, D.; Kalushkov, P. Alien vs. Predator – the native lacewing Chrysoperla carnea is the superior intraguild predator in trials against the invasive ladybird Harmonia axyridis. Bull. Insectology 2013, 66, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Synder, W.E.; Joseph, S.B.; Preziosi, R.F.; Moore, A.J. Nutritional benefits of cannibalism for the lady beetle Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) when prey quality is poor. Environ. Entomol. 2000, 29, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.W. Searching and reproductive behaviour of female aphidophagous ladybirds (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): a review. Eur. J. Entomol., 2003, 100, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M.A.; Tirry, L.; Arbab, A.; De Clercq, P. Temperature-dependent development of the two-spotted ladybeetle, Adalia bipunctata, on the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae, and a factitious food under constant temperatures. J. Insect Sci. 2010, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayeh, A.; Estoup, A.; Lombaert, E.; Guillemaud, T.; Kirichenko, N.; Lawson-Handley, L.; Facon, B. Cannibalism in invasive, native and biocontrol populations of the harlequin ladybird. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, B.K. Why do ladybirds (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) cannibalize? J. Biosciences 1991, 16, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrie, G.; Meseguer, R.; Lucas, E. Stage-specific vulnerability of Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) to intraguild predation. Eur. J. Entomol. 2023, 120, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, J.; Díaz-Fleischer, F. Oviposition deterrents for the Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) from fly faeces extracts. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2006, 96, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Růžička, Z. Recognition of oviposition-deterring allomones by aphidophagous predators (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae, Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 1997, 94, 431–434. [Google Scholar]

- Růžička, Z. Persistence of deterrent larval tracks in Coccinella septempunctata, Cycloneda limbifer and Semiadalia undecimnotata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2002, 94, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemptinne, J.L.; Lognay, G.; Doumbia, M.; Dixon, A.F.G. Chemical nature and persistence of the oviposition deterring pheromone in the tracks of the larvae of the two spot ladybird, Adalia bipunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Chemoecology 2001, 11, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Takagi, T.; Kogi, K.K. Effects of conspecific and heterospecific larval tracks on the oviposition behaviour of the predatory ladybird, Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2000, 97, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindlmann, P.; Štípková, Z.; Dixon, A.F.G. Generation time ratio, rather than voracity, determines population dynamics of insect - natural enemy systems, contrary to classical Lotka-Volterra models. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 10, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostálková, I.; Kindlmann, P.; Dixon, A.F.G. Are classical predator-prey models relevant to the real world? J. Theor. Biol. 2002, 218, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, A.F.G.; Honěk, A.; Jarošík, V. Physiological mechanism governing slow and fast development in predatory ladybirds. Physiol. Entomol. 2013, 38, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdková, K.; Kidlmann, P. Scaling up population dynamic processes in a ladybird-aphid system. Popul. Ecol. 2006, 48, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.L.; Tang, R.; Liu, T.X.; Qiu, B.L. Larval and/or Adult exposure to intraguild predator Harmonia axyridis alters reproductive allocation decisions and offspring growth in Menochilus sexmaculatus. Insects 2023, 14, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, J.-P. A comparative study of larval cannibalism in three species of ladybird. Ecol. Entomol. 2003, 28, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, S.; Nedvěd, O. Root elongation test on seeds of Sinapis alba reveals toxicity of extracts from thirteen colour forms of the Asian multi-coloured ladybird, Harmonia axyridis Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2023, 171, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznik, S.Y.; Belyakova, N.A.; Ovchinnikov, A.N.; Ovchinnikova, A.A. The influence of density-dependent factors on larval development in native and invasive populations of Harmonia axyridis (Pall.) (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae). Entomol. Rev. 2017, 97, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Population density-dependent developmental regulation in migratory locust. Insects 2024, 15, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couret, J.; Dotson, E.; Benedict, M.Q. Temperature, larval diet, and density effects on development rate and survival of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). PlosOne 2014, 9, e87468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Ramos, T.; Dos Santos-Cividanes, T.; Cividanes, F.; Dos Santos, L. Harmonia axyridis Pallas (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): Biological aspects and thermal requirements. Adv. Entomol. 2014, 2, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznik, S.Y.; Belyakova, N.A.; Ovchinnikov, A.N.; Ovchinnikova, A.A. The influence of density-dependent factors on larval development in native and invasive populations of Harmonia axyridis (Pall.) (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae). Entomol. Rev. 2017, 97, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kökdener, M.; Kiper, F. Effects of larval population density and food type on the life cycle of Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae), Environ. Entomol. 2021, 50, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkitachalam, S.; Das, S.; Deep, A.; et al. Density-dependent selection in Drosophila: evolution of egg size and hatching time. J. Genet. 2022, 101, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarangi, M.; Naragaranjan, A.; Dey, S.; et al. Evolution of increased larval competitive ability in Drosophila melanogaster without increased larval feeding rate. J. Genet. 2016, 95, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauerfeind, S.S.; Fischer, K.; Larsson, S. Effects of Food stress and density in different life stages on reproduction in a butterfly. Oikos 2005, 111, 514–524, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3548643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Harrison, R. L.; Shi, J. Effects of rearing density on developmental traits of two different biotypes of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar L., from China and the USA. Insects, 2021, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedvěd, O.; Honěk, A. Life history and development. In Hodek I., van Emden H.F. & Honěk A. (eds): Ecology and Behaviour of the Ladybird Beetles (Coccinellidae). Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, 2012; pp. 54–109.

- Reznik, S.Y.; Dolgovskaya, M.Y.; Ovchinnikov, A.N. Effect of photoperiod on adult size and weight in Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur. J. Entomol. 2015, 112, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).