2. The Special Theory of Relativity (STR) and the Block Universe

In the years following the publication of STR (1905), many physicists embraced either the block universe (Eddington, Minkowski, Weyl) or an idealist view of time (Gödel, Gold, von Laue). The block universe refers to Minkowski’s four-dimensional representation of STR. Time becomes a fourth dimension, on a par with the three dimensions of space. In Minkowski space-time time and space appear as two axes in a space-time diagram, whose maximum separation is a right angle for a stationary observer. But the angle between the axes shifts away from the right angles by an equal amount for an observer moving in relation to the stationary observer. This change means that two observers in relative motion to each other disagree about the duration of an event and the time of its occurrence. An idealist view of time refers to views of time, as defended by Saint Augustine and Kant, according to which time is a mental construct. Temporal awareness is taken to be built into the human mind either as a pure form of intuition (Kant) or as succeeding changes in perceptions (Saint Augustine). Acceptance of the block universe entails an idealist view of time. This is often expressed in the (erroneous) statement that clocks tick differently for observers in relative motion with one another. But acceptance of an idealist view of time does not necessarily entail a block universe, if the latter representation is ignored. The physicist Max von Laue echoed Kant when he declared that ‘time and space are (…) pure forms of intuition; a scheme into which we must order events, so that they take on objective meaning – in contrast to subjective, highly accidental perceptions.’ (Von Laue 21913: 37) According to Eddington and Cunningham time and space are merely a mental scaffolding or modes of thought.

Although Einstein originally accepted the block universe, once he had become convinced of the usefulness of Minkowski space-time as a representation of the STR, he changed his mind towards the end of his life. He even hinted at a dynamic view of time, as shown below. The STR can thus be taken to either imply a static, Parmenidean view– stasis– or a dynamic, Heraclitean view of time – flux. Parmenidean stasis seems to be the predominant view. It leads to the implication that physical time is unreal, that time is not a physical parameter. This may lead to the further step of saying that the perception of time is ‘personal’ (Carroll 2022: 147) or a mental affair (Weyl 41921/1952: 3, 227). In the language of philosophy Weyl’s statement reflects an idealist view of time because the perception of time seems to be relegated to individual observers. Heraclitean flux is a minority view but defended by some physicists: ‘…space and time do not have independent existence; they are nothing but mirroring the relations among physical events taking place in the world.’ (Cheng 22010: 4) In the language of philosophy this statement reflects a relational account of physical time, as it was first formulated by Leibniz.

Which features of the STR and Minkowski space-time were taken to imply aParmenidean, static view of time? The most important parameter, which has tempted many physicists and philosophers to embrace the block universe or an idealist view of time, is the relativity of simultaneity. A typical statement taken from a textbook on relativity, illustrates what is meant by this concept:

Special relativity makes the strange claim that observers in relative motion will have different perceptions of distance and time. This means that two identical watches worn by two observers in relative motion will tick at different rates and will not agree on the amount of time that has elapsed between two given events. It is not that these two watches are defective. Rather, it is a fundamental statement about the nature of time. (Cheng 22010: 26)

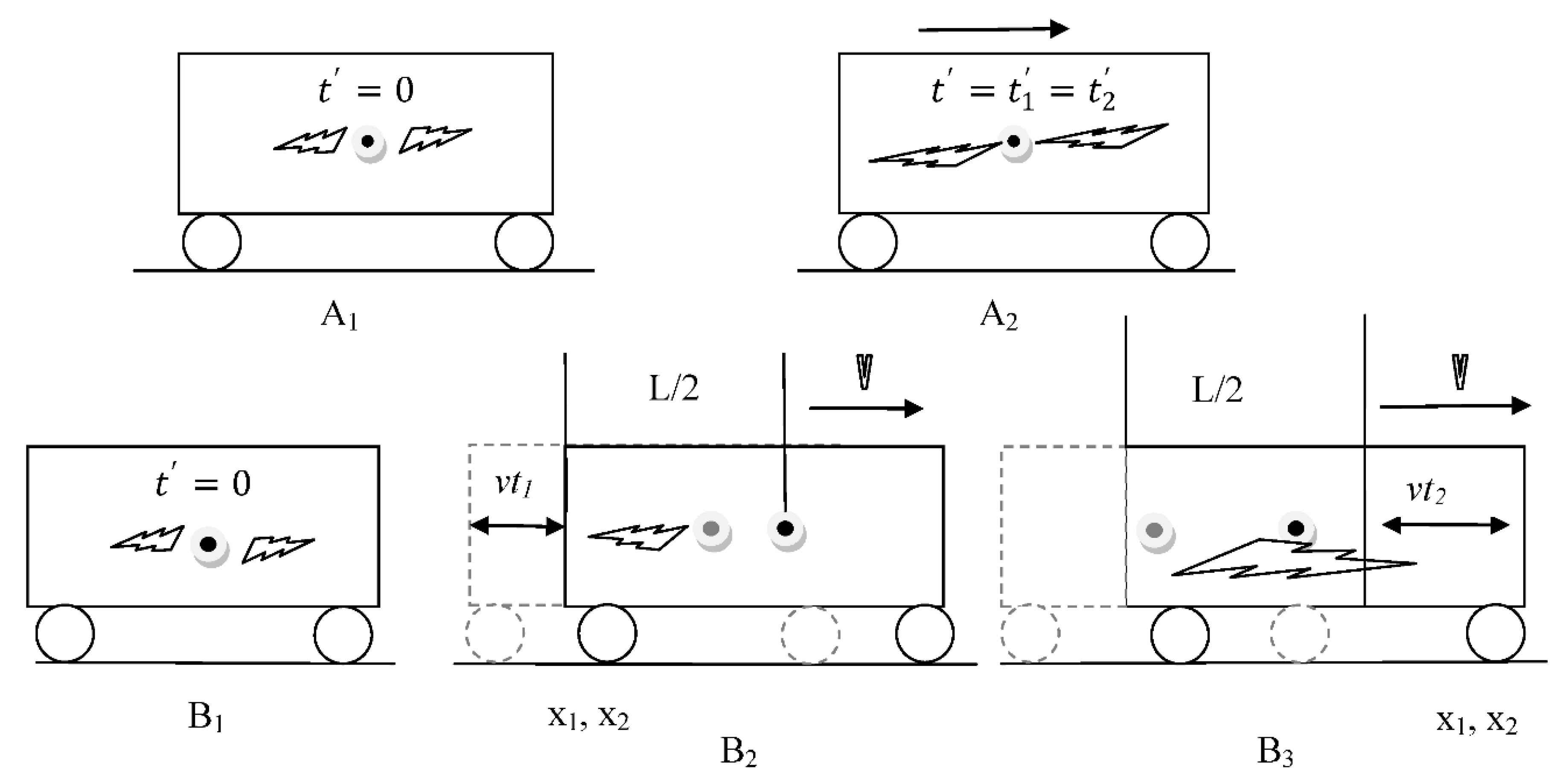

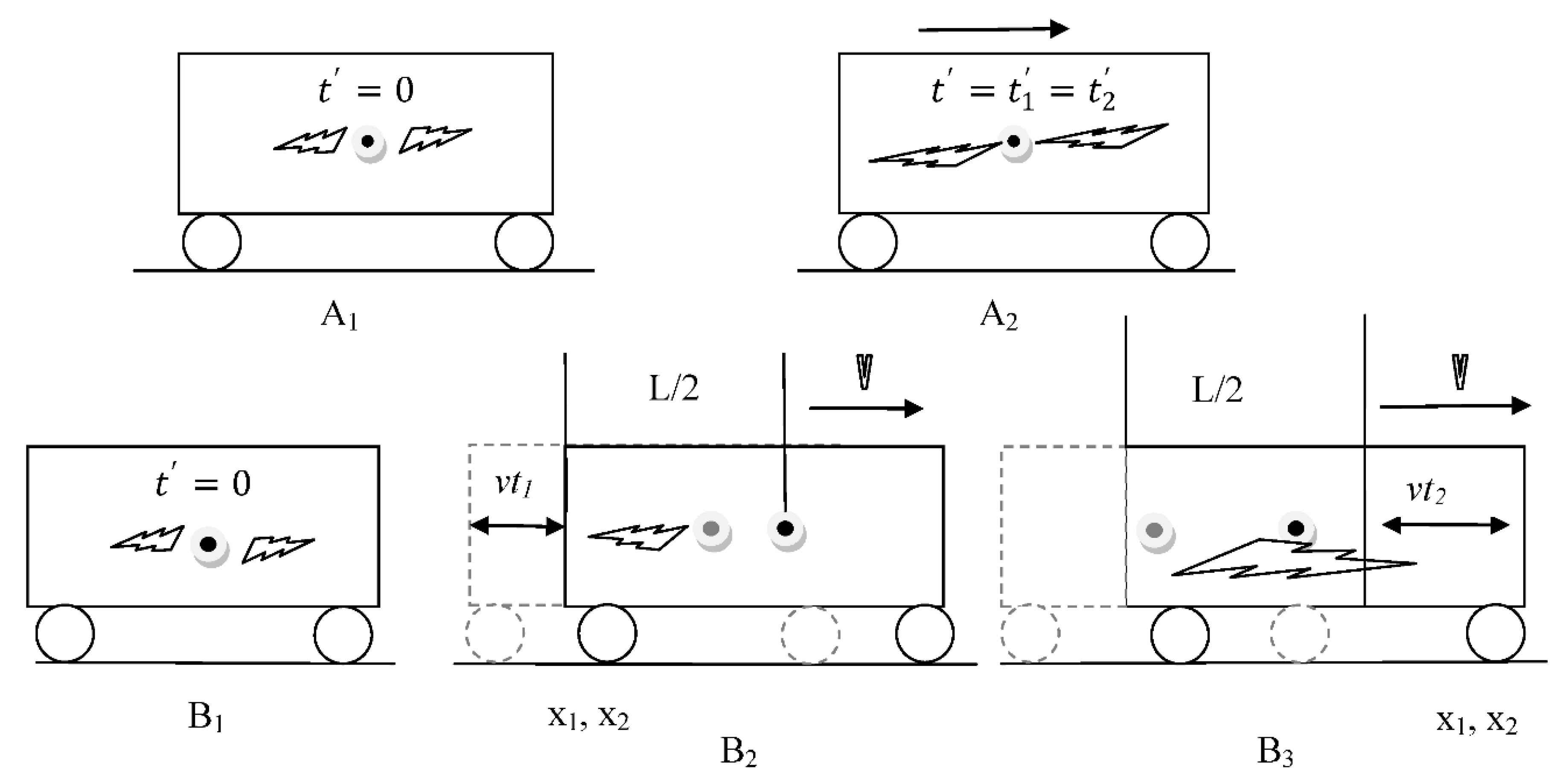

Thus, relative simultaneity means that two observers who are in relative (relativistic) motion with respect to each other will not agree on whether two events happened at the same time. A popular illustration of the relativity of simultaneity involves two observers, one sitting on a fast-moving train and the other standing on a station platform. They observe the same event say, a light pulse, which is emitted from the middle of the train. The question is: do the two observers, the one on the train, the other on the platform, agree on the moment when the front and rear of the train are hit? The straight-forward answer, according to relativity, is ‘no’. The observer who is sitting in the rail coach will see the light pulse as arriving at the same time at opposite ends of the moving train (

Figure 1: events A

1& A

2). This observer is located in the same reference frame as the light pulse. Their clock measures proper time. However, the observer on the platform (events B

1, B

2, B

3) will not agree that the two light pulses arrive at the train walls at the same time. This observer is at rest with respect to the observer on the moving train. For this observer the situation consists of two parts: the light pulse, which is moving in the direction of the train, arrives later (at B

3) than the light pulse in the opposite direction (at B

1). Light pulses travel at a finite speed,

c. The light pulse in the opposite direction to the motion of the train has a shorter distance (

vt1) to travel to the end wall of the rail coach. The end of the rail coach ‘travels towards it’. But the light signal has to travel a larger distance (

vt2) to the front of the train because the train front is ‘running away from it’. The light pulses must cover the distances

to the back and the front of the train, respectively. The propagation times are

Before I proceed to argue that, despite appearances, the STR is actually more compatible with the Heraclitean than the Parmenidean view, some clarifications are in order.

Although one often reads that according to the STR, time is relative to particular reference frames, time is not observer-dependent, although clocks do reflect the path-length of an observer’s journey through space-time. The reference to human observers is misleading because the ‘relativity’ of time is not dependent on human observers. If all observers are replaced by clocks, the same relativity of simultaneity occurs. It is true, however, that clock time becomes path-dependent, since proper time measures the time along the travelled path (distance).

It is not the case that clocks ‘tick at different rates’, in their respective reference frames. The clocks which are attached to reference frame tick at the time rate. Such clocks indicate ‘proper time’. But the ‘observation’ of proper time in one frame from the point of view of another frame appears to be different. This notion is called ‘coordinate time’. Coordinate time is the common reference time on space-time, as ‘seen’ by observers who are in relative motion to each other. In the STR proper time and coordinate time are the same for an inertial observer. ‘You will sometimes hear that time can speed up or slow down according to the theory of relativity. That’s baloney. Or to be more polite about it, it’s a misleading way to describe a real phenomenon.’ (Carroll 2022: 148)

Figure 1.

Relativity of Simultaneity (adapted from Cheng 22010: 24). At location A1 and time t’=0 the observer on the train sees a light pulse being emitted from the centre of the train coach. As the observer is moving along with the train s/he is in the train’s inertial system which means that s/he sees the light pulse hitting the front and rear walls at the same time (A2). At B1, and the beginning of the experiment (t’=0), the observer is at rest on the platform with respect to the train. The train moves to the right at high speed. At B2 the train has moved a distance d=vt1to the rightso that for the observer at rest the light source is no longer at the mid-point of the train but has moved to the left. The light pulse therefore has a shorter distance to travel to the rear end of the rail car. At location B3 the train has moved further, namely a distance d=vt2. The light pulse now has a larger distance to travel to reach the front end of the rail car. Therefore for the stationary observer the arrival of the light pulse at the front and rear end of the train are not simultaneous.

Figure 1.

Relativity of Simultaneity (adapted from Cheng 22010: 24). At location A1 and time t’=0 the observer on the train sees a light pulse being emitted from the centre of the train coach. As the observer is moving along with the train s/he is in the train’s inertial system which means that s/he sees the light pulse hitting the front and rear walls at the same time (A2). At B1, and the beginning of the experiment (t’=0), the observer is at rest on the platform with respect to the train. The train moves to the right at high speed. At B2 the train has moved a distance d=vt1to the rightso that for the observer at rest the light source is no longer at the mid-point of the train but has moved to the left. The light pulse therefore has a shorter distance to travel to the rear end of the rail car. At location B3 the train has moved further, namely a distance d=vt2. The light pulse now has a larger distance to travel to reach the front end of the rail car. Therefore for the stationary observer the arrival of the light pulse at the front and rear end of the train are not simultaneous.

Once such misconceptions are removed and experimental test results are taken into account, it becomes clear that time, according to the STR, does not dependent on human observers and that clocks tick regularly and at the same rate in every reference frame (proper time). Nevertheless, the argument for the unreality of time hinges on the presence of observers. It is then not difficult to see how relative simultaneity, in addition to the two misconceptions, mentioned above, can lead to the conclusion that time, according to the STR, has become unreal. Einstein himself drew this conclusion:

No absolute meaning can be assigned to the conception of the simultaneity of events that occur at points separated by a distance in space (…). (Einstein 1929: 1073)

According to Einstein, physics becomes a sort of static block in a four-dimensional continuum.

From a “happening” in three-dimensional space, physics becomes, as it were, an “existence” in the four-dimensional “world”. (Einstein 1920: Ch. IX, 26)

The fact that two observers in relative motion with respect to each other cannot agree on the simultaneity of events, also means that their clocks do not agree on the times of the event (Eq.1). One consequence of the STR is that time is not universal, as it is in Newton’s universe. Every reference frames carries its own clock and observers in these frames will disagree about temporal measurements and the simultaneity of events. It seems that there only exists a timeless block of events: the block universe. The distinction between past, present and future is suspended. The block universe is the consequence of Minkowski’s presentation of the STR as a four-dimensional space-time, in which time and space exist on an equal footing.

It appears therefore more natural to think of physical reality as a four-dimensional existence, instead of, as hitherto, the evolution of a three-dimensional existence. (Einstein 1920: Appendix II, 122; Appendix V, 150)

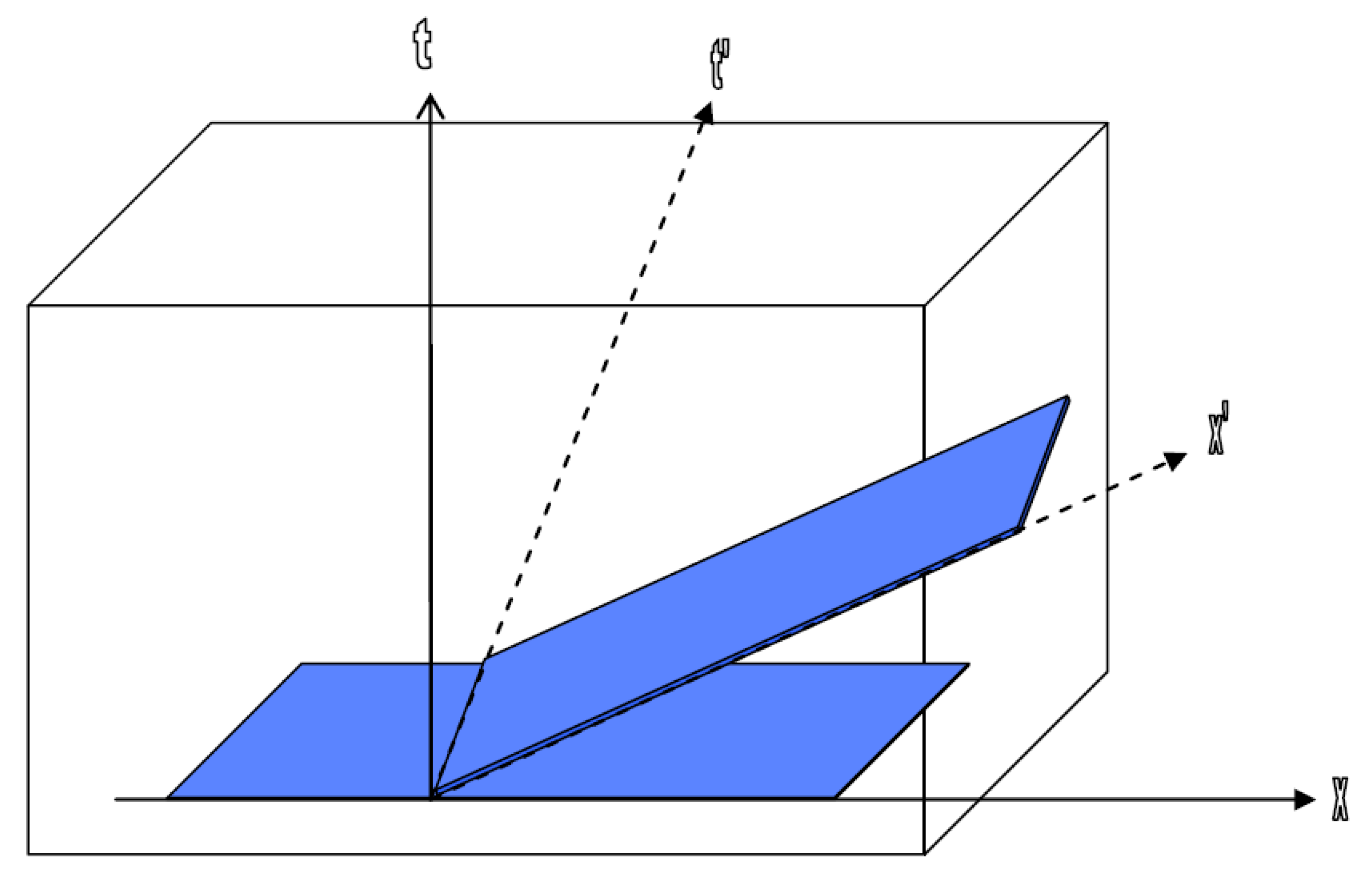

Arthur Eddington (1920: 36, 51) proposed the analogy of solid block of paper to capture the idea of a four-dimensional continuum and the observer-dependence of the separation of space and time. Each observer, depending on the state of motion, will slice the block differently. The lamination planes (or foliation planes) at different angles indicate the respective observer's perspective on simultaneity. The Special theory of relativity only allows relative simultaneity. For any observer, events are simultaneous if they lie on a plane, which lies perpendicular to the observer's path through space-time.

Figure 2.

Lamination of space-time block by different observers in relative, inertial motion to each other.

Figure 2.

Lamination of space-time block by different observers in relative, inertial motion to each other.

This representation exploits a particular feature of the STR – the relativity of simultaneity – to infer the unreality of time. It is a static interpretation of the STR.

It is important to keep in mind that the ‘unreality’ of time is not a deductive consequence to the STR. The deductive consequences of the STR are related to its two fundamental principles: the constancy of the velocity of light, c, and the principle of relativity. The deductive consequences are: time dilation, length contraction and relative simultaneity. The ‘unreality’ of time is a conceptual inference from one feature of STR, the relativity of simultaneity of events. It shows that a scientific theory has philosophical consequences. But then the question arises what other features of the theory give us information about the ‘nature’ of time. In other words, is there a dynamic interpretation of the STR?

Although the authority of the master physicists discouraged a dynamic interpretation of the STR, at least some physicists, like Paul Langevin in the 1920s, adopted a dynamic interpretation of the Special theory of relativity. (Langevin 1923) Taking up E. Cunningham’s suggestion that world lines have a history, Langevin added that this history was irreversible.

Let us review some of the features of the Special theory of relativity, which support a dynamic interpretation: causal propagation and irreversible processes. These two facts about the STR are well illustrated in the so-called Twin Paradox.

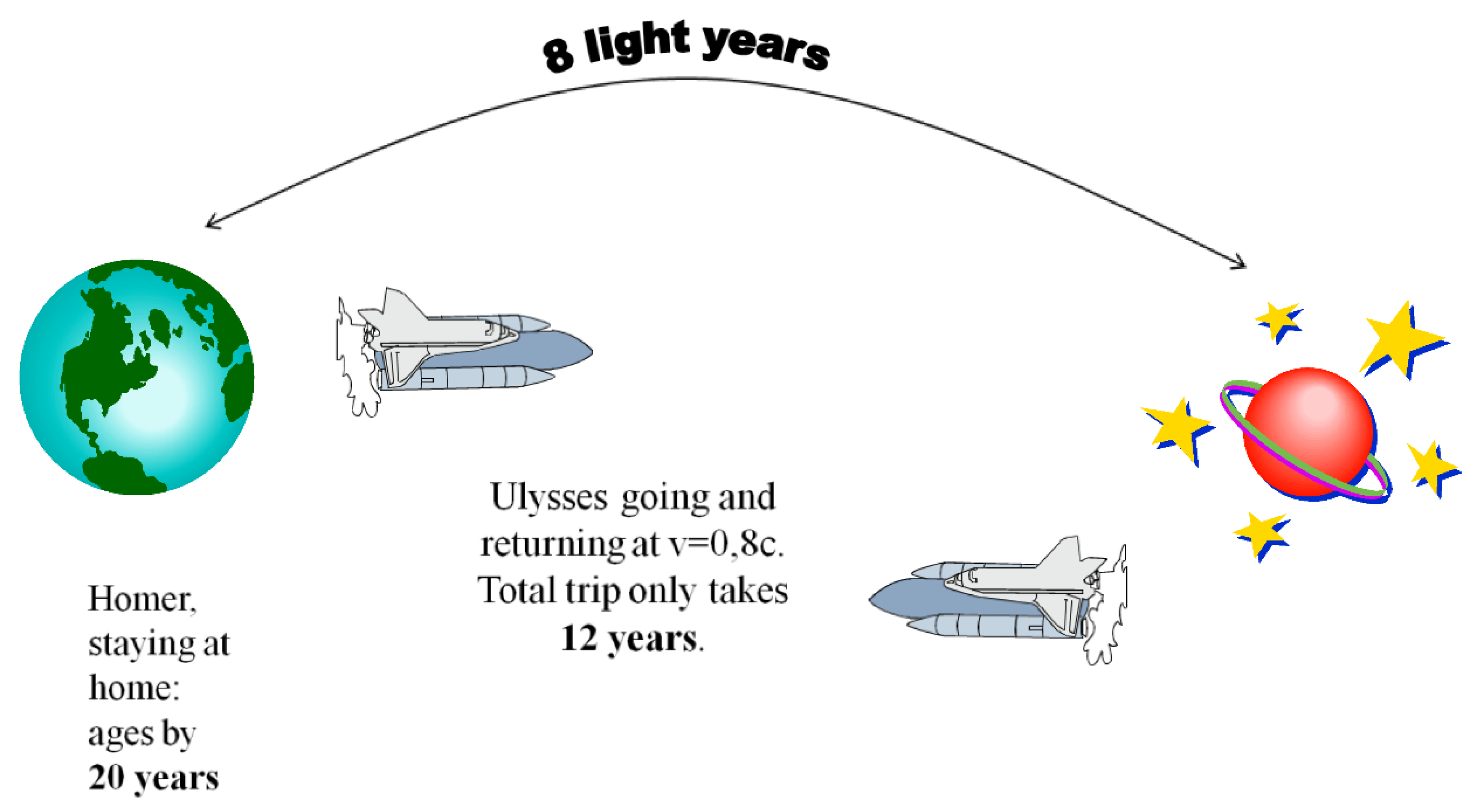

To illustrate, here is a reminder of an imaginary journey involving two twins: Homer and Ulysses. They decide to run an experiment. Homer will stay on Earth while Ulysses visits a distant planet, some 8 light years away. Ulysses’s spaceship travels at 80% of the speed of light (0.8c). Then according to Homer the journey there and back should take 20 years, 10 years for each leg. But not so for Ulysses. Ulysses’s clocks slow down, compared to Homer’s clocks. According to Ulysses’s clocks the round-trip will only take 12 years (

Figure 3). As a consequence, Ulysses will be younger than Homer on his return. It sounds paradoxical but it is ‘a consequence of time dilation, or the slowing down of the traveler’s clock relative to that of the twin.’ (Will 1988: 54)

Does this mean that time is ‘personal’? During the trip, the twins will be able to communicate with each other by exchanging signals, say once every year. From these signals they can calculate each other’s age. The signals will be Doppler-shifted, due to the speeds involved. The speeds will affect both the frequency,, and the wavelength, , of the signals. (The speed of the wave is the product of the frequency of the wave multiplied by its wavelength.) Homer will receive 12 signals from Ulysses. He will be able to calculate that his brother will be 8 years younger when he returns to Earth. Ulysses will receive 20 signals from Homer. He will be able to infer from Homer’s signals that his brother will have aged 20 years. At one point the signals may stop. If Ulysses were able to travel close to the speed of light he would return to Earth in the distant future. In a way Ulysses would have travelled far into the future. A very fast moving time traveller would only age by 31.6 years in 500 years of Earth time.

Figure 3.

The Twin Thought Experiment. An illustration of the time dilation effect, drawn by author.

Figure 3.

The Twin Thought Experiment. An illustration of the time dilation effect, drawn by author.

The twin thought experiment, which is not a paradox, helps us to highlight two aspects of relativity, which support a dynamic interpretation of the STR.

There is, firstly, the argument from the irreversibility of causal propagation. The propagation of a signal from an earlier to a later space-time event is an irreversible process. The irreversibility of world lines not only means that they acquire a history, as Langevin pointed out. It also means that there is an asymmetry between an earlier and a later space-time event, such that causal signals can be sent from the earlier to the later event. Causal signals cannot travel faster than the speed of light.

Causal propagation only concerns time-like connected events. At least as far as time-like connected events are concerned, their order of succession is the same for all observers. Even proponents of the philosophy of being agree that between time-like connected events, the ‘before-after’-relation is irreversible. Observers in relative motion to each other cannot agree on the set of events, which they call 'simultaneous'. But this does not mean, contrary to what proponents of the unreality of time assert, that the notion of simultaneity loses its objective meaning. As long as observers do not reside outside of each other's light cones, they can make use of the Lorentz transformations to communicate their respective temporal and spatial measurements to each other. Equipped with the Lorentz transformations, each observer can predict two things: a) the other observer's temporal and spatial measurements for the duration of events and b) the other observer's determination of the simultaneity plane of events. There is no subjective ingredient in these calculations. (Langevin 1923: Ch. VI; Bohm 1965: 151) All observers moving relative to each other at constant speed will agree on the same temporal order - but disagree on the duration and simultaneity of events!

The succession of causally related events is a topological invariant, independent of our choice of reference frame. The invariance belongs to the space-time interval

ds

and concerns the relations

ds2 = 0 (the null interval) and

ds2> 0 (the

time-like interval). In other words, as Bohm (1965: §§XXVIII, XXXI) and Langevin (1923: 127) pointed out, world lines of this kind are irreversible. They may coincide in space, but cannot be made to coincide in time. The order of events cannot be inverted by a change of reference system. The interval

ds has physical significance because it is directly related to proper time:

;

τ(rest frame time) is related to coordinate time

t by the well-known formula

(where

;

By contrast, in the case where

ds2< 0, the case of a

space-

like separation of events without possibility of causal connections, there is no definite order of succession of events. These space-time events lie outside each other’s light cone. By an appropriate choice of the reference system, they can be made to coincide in time. (Langevin 1923: 285-6)

When two events are in each other’s absolute elsewhere, so that they can have no physical contact, it makes no difference whether we say they are before or after each other. Their relative time order has a purely conventional character, in the sense that one can ascribe any such order that is convenient, as long as one applies these conventions in a consistent manner. Observers, moving at different speeds, and correcting for the time Δt, taken by light to reach them from a point at a distance r by the formula Δt=r/c, will arrive at different conventions for assigning such event as before, after, and simultaneous with some event taking place in the immediate neighbourhood of the observer. But as long as there is no physical contact, which is the basis of the relationship of causal connection of events, it does not matter what we say about which is before and which is after. On the other hand where such causal contact is possible, the order of events is unambiguous, so that the Lorentz transformation will never lead to confusion as to what is a cause and what is an effect. (Bohm 1965: 159-60)

Both the proponents of a philosophy of being and a philosophy of becoming agree on the fundamental postulate of the Special theory of relativity: the invariance of the velocity of light in all inertial reference frames. This means that light cones, emanating from events, have an invariant structure. Light cones do not tilt according to the STR as they do in gravitational fields. But physical trajectories or causal signals travel inside the light cones between events.

The second aspect, in support of a dynamic view of time, refers to irreversible processes. They may legitimately be considered to support a dynamic interpretation of STR. Shortly before his death in 1955, Einstein expressed the idea of the block universe or the static picture of reality in the following words:

For us believing physicists, the distinction between past, present, and future is only an illusion, even if a stubborn one. (Quoted in Hoffmann 1972: 257-8)

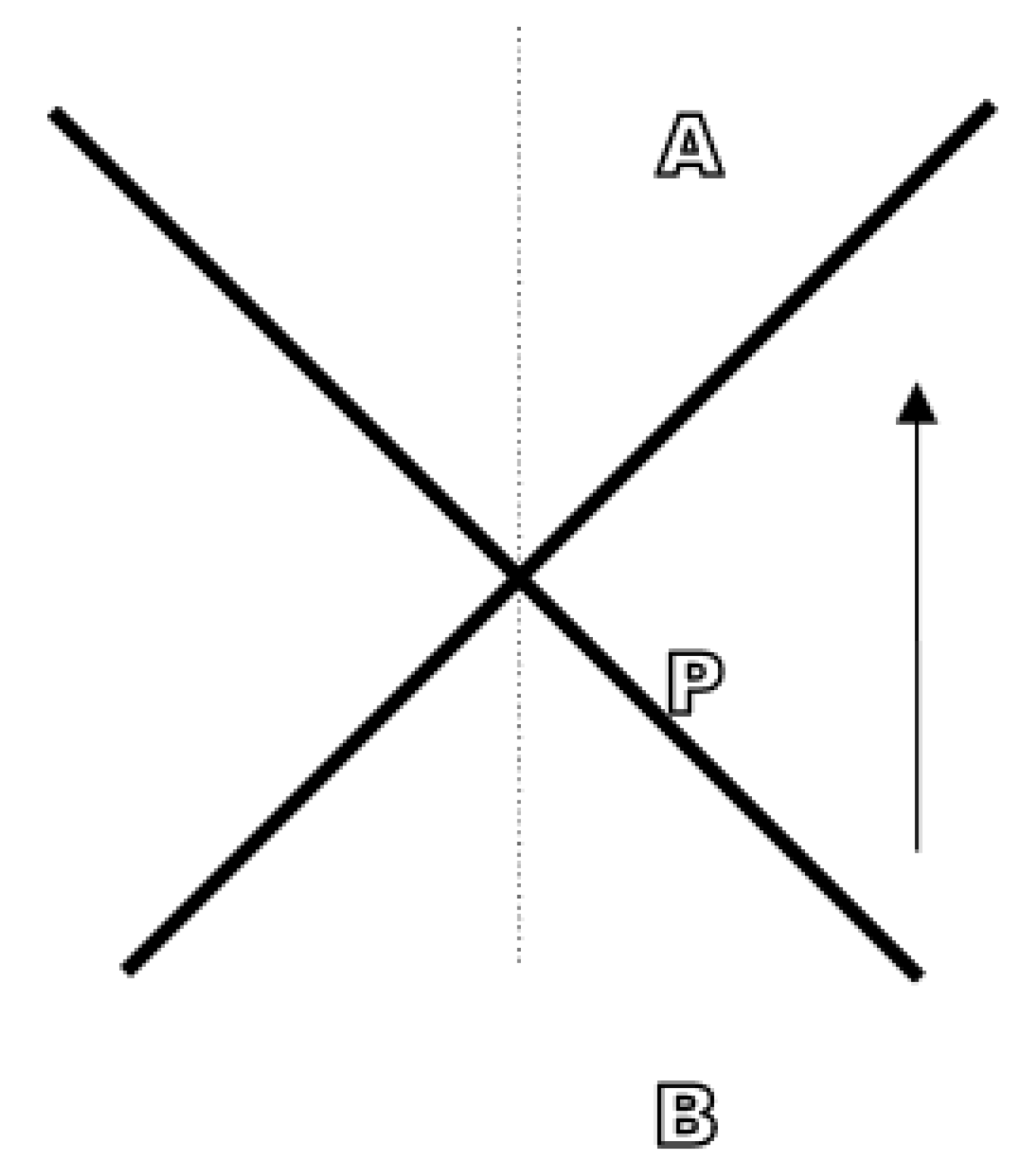

But when he was invited to comment on Gödel's claim of a connection between the theory of relativity and the block universe, Einstein was unwilling to draw idealistic consequences. Quite 'aside from the relation of the theory of relativity to idealistic philosophy' Einstein considers the question of the direction of time. (Einstein 1949: 687-8) Without realising it, he injects a dynamic element into the

static representation of reality and therefore the block universe. Imagine a signal is sent from

A to

B through

P. This is an irreversible process. On thermodynamic grounds he asserts that a

time-like world line from

B to

A through

P in a light cone, takes the form of an arrow making

B happen

before P and

A after P (

Figure 4). This secures the 'one-sided (asymmetrical) character of time (…), i.e., there exists no free choice for the direction of the arrow.' (Einstein 1949: 687; cf. Einstein 1920: 139-41) This is true at least if points

A,

B and

P are sufficiently close in cosmological terms. But the asymmetrical character of time is here based on a fundamental

earlier-later or

before-after relation between physical events without reference to an observer. There is an event,

B, at which the signal is emitted. And there is a later event,

A, at which the signal is received. Einstein had claimed that the

static representation is more objective than the

dynamic representation. In his reply to Gödel there is a subtle shift. He introduces elementary change - the motion of the signal from

B to

A. It takes time for the signal to reach

A. This means that world lines have a

history due to the invariance of

c. In his reply to Gödel, Einstein thus gives an indication that the loss of fixity of the time axis need not lead to a static block universe. It is interesting to note that Eddington, too, came to doubt the reality of the block universe. According to Eddington, (1929: 92) the problem with the Minkowski view was that it ‘leaves the external world without any dynamic quality.’ In one of the first books on relativity in the English-speaking world, published by E. Cunningham in 1915, a similar interpretation of the union of space and time is suggested.

The motion of a moving point through all time is represented by a single curve, the points on the curve being ordered to correspond with the succession of events in time, but the interpretation of the curve as representing an ordinary motion is not unique; it depends upon the choice of the direction in the four-dimensional region which is chosen to be the time axis.1 (Cunningham 1915: §60)

Figure 4.

Einstein's consideration of the direction of time in response to Gödel's idealistic interpretation of the special theory of relativity. A time-like world line exists between events, which lies within, not outside, the light cone.

Figure 4.

Einstein's consideration of the direction of time in response to Gödel's idealistic interpretation of the special theory of relativity. A time-like world line exists between events, which lies within, not outside, the light cone.

In his objection to Gödel, Einstein had pointed out that a

time-like world line from

B to

A satisfied the fundamental ‘before-after’-relation (

Figure 4). It is in fact a fundamental result of the Special theory of relativity that the entropy of a system is frame-independent. (Einstein 1917: §15) The entropy of closed systems is their universal tendency, loosely speaking, to develop over time from a state of high order to a state of low order. Frame-independence of entropy means that from every reference frame the same tendency of closed systems to increase their disorder will be observed. Entropic order is not reversible by a convenient choice of reference frame. It is a difficult and separate question whether entropy, in the sense of Statistical Mechanics, is the basis of the direction of time. Even if the cosmic arrow of time cannot be identified with the Second law, entropic processes are irreversible in every reference frame. Entropic processes bear witness to change and the succession of events from a lower to a higher state of entropy. This is an

invariant of the theory and can lay claim to being part of objective reality. By this criterion, then, the transience of entropic states is evidence of real physical becoming, on which all observers in every reference frame will agree. As will be shown in the next section, the frame-invariance of entropy extends to the GTR.

This section has considered two criteria, two types of invariance, which strongly suggests that a dynamic interpretation of the STR is permissible and leads to a dynamic view of time. Furthermore the causal propagation of signals and the invariance of entropy are processes in the physical world. Clocks must ultimately be based on such regular and invariant physical processes.

3. The General Theory of Relativity (GTR) and the Unreality of Time

The most important difference between the space-time of the two versions of the theory of relativity is that the space-time of the STR is flat (Euclidean) and fixed, whilst the space-time of GTR is curved and dynamic. This means that the space-time of GTR is determined by the energy-matter distribution in the universe. ‘GR fulfils Einstein’s conviction that “space is not a thing:” the ever-changing relation of matter and energy is reflected by an ever-changing geometry.’ (Cheng 22010: 104) From this difference all the important differences follow. The Special theory may be compatible with the inference to the passage of time in the local neighbourhoods of inertially moving observers, but the anisotropy of time may still be an illusion from a cosmological point of view. There may be no cosmic time, no global temporal orientation. The Special theory is only an approximation to the General theory in physical systems, where the effect of gravitation and acceleration can be neglected. There have been a number of attempts to show that the General theory also supports a timeless block universe. But here again the distinction between technical aspects of the theoretical apparatus – the symmetry of the equations – and their asymmetrical solutions is important. The theory itself makes no distinction between past, present and future, but its solutions imply the anisotropy of time. (Carroll 2022: 262) Gravitation affects the running of clocks in a similar way as the motion of inertial systems.

In contrast to his Special theory, Einstein’s General Theory of relativity (1916) is a cosmological theory. Einstein was motivated to construct such a theory because he found that even his Special theory gave an unjustified preference to inertial coordinate systems. His theory replaced the Newtonian notion of gravity, affecting the behaviour of bodies, by the notion of space-time curvature. Einstein identifies non-inertial (accelerated) reference frames in Newton’s theory with the presence of gravitational forces (equivalence principle). The General theory deals with the large space-time structures of the universe, and it shows how the running of clocks and the behaviour of light rays are affected by the presence of energy-matter fields. But the General theory says nothing about the origin of time. The origin of temporal asymmetry is often attributed to the initial conditions of the universe, in conjunction with gravitational clumping and the operation of the Second law of thermodynamics. Nevertheless, entropic considerations play a part in both versions of the theory of relativity.

Let us first examine the claim that the General theory of relativity supports Parmenidean stasis. The argument comes in two flavours: Einstein’s point-coincidence argument and a relativistic reconstruction of McTaggart’s ‘proof’ of the unreality of time.

1. Einstein’s point-coincidence argument. To repeat, the General theory reaffirms the relativity of temporal measurements, because the running of clocks is affected by gravitational fields. 2 Furthermore, the structure of the General theory, as a gauge theory, means that coordinate transformations are local transformations in contrast to the global transformations in Minkowski space-time. Gauge transformations are position-dependent, reflecting the dynamic nature of space-time. Einstein asserted that the General theory had deprived time of the last vestiges of reality. (Einstein 1916) This claim stands in stark contrast to Newton’s mechanics in which the symbol treflects Newton’s assertion that time is a physical parameter in the physical universe. According to Newton time is absolute (independent of physical events) and universal (the universe has a master clock). Einstein specifically claims that the laws of physics are statements about space-time coincidences. In fact only such statements can ‘claim physical existence’. (Einstein 1918, 241; 1920, 95; cf. Norton 1992, 298)As a material point moves through space-time its coordinate system is marked by a large number of co-ordinate values x1, x2, x3, x4;x’1, x’2, x’3, x’4and so on. This is true of any material point in motion. It is only where the space-time coordinates of the systems intersect that they ‘have a particular system of coordinate values x1, x2, x3, x4 in common’. (Einstein 1916, 86; 1920, 95) In terms of observers, attached to different coordinate systems, it is only at such points of encounter that they can agree on their temporal and spatial measurements. This means that they disagree about spatial and temporal measurements when they are in relative accelerated motion with each other. This is due to the effect of gravitational fields on the running of clocks, which need to be subtracted from the inertial effect. Einstein, as we can see, reasons from technical aspects of the theory of relativity to the nature of time. The point-coincidence argument implies for Einstein ‘the unreality of time.’ (Cf. Lockwood 2005: 87)

The reason for this implication is that the coordinates in the General theory are no longer read in a realist sense, as representing particular space-time points. GTR allows a ‘democracy of coordinate systems’ but the coordinates have no intrinsic meaning. (Cheng 22010: 7, 301) Observers are free to choose different coordinates to label events. The coordinates of its coordinate system can be marked by a large number of coordinate values, either Gaussian coordinates (for two-dimensional spheres) or Riemannian coordinates (μ=0, 1, 2, 3) for four-dimensional space. These coordinates are taken to be arbitrary symbols, deprived of any realist implications. In other words, equations should not depend on ‘any particular choice of coordinates.’ (Penrose 2005: 469)

We assign to every point of the continuum (event) four numbers, x1, x2, x3, x4 (co-ordinates), which have not the least direct physical significance, but only serve the purpose of numbering the points of the continuum in a definite but arbitrary manner. (Einstein 1920: 94; cf. Carroll 2022: 190; Cheng 22010: 83, 119)

Particles share a particular system of coordinate values x1, x2, x3, x4where their world lines intersect. The General theory, then, presents a situation in which arbitrary generalized coordinates, linked by (continuous but local) transformations, can be used to describe material points, which are in accelerated motion. As Einstein said, the dynamical variables of the theory can be expressed in a number of ways, and this freedom is expressed in the gauge (or local) symmetries. This characterization essentially re-affirms, in more abstract terms, the point made in the Special theory that there are as ‘many clock times as there are reference frames’, with the consequence that the objective passage of time seems to be illusory. Again, the argument concentrates on one aspect of the theory, at the expense of others. Yet, as observed before, invariance plays a significant part in physical theories. It is obviously important that underlying these coordinates there is some invariant structure. No conclusions regarding the ‘reality’ or ‘unreality’ of time should be drawn as long as the invariant features of the General theory have not been investigated. The fact that many different kinds of descriptions can be used to express the motion of material particles in space-time imposes a requirement of ‘covariance’: covariant laws must have the same form in every coordinate system and covariant transformations must leave the same invariant structure. Einstein calls this requirement ‘the general principle of covariance’: ‘Natural laws must be covariant with respect to arbitrary continuous transformations of the coordinates.’ (Einstein 1920: 152-3) In modern space-time theories these general coordinate transformations are termed ‘general covariance’ or ‘diffeomorphism’. A diffeomorphism d is a one-to-one mapping of a differentiable manifold M into another differentiable manifold N.

The General theory is characterized by mathematical structures or models of the form, where M is a four-dimensional manifold, representing space-time, g is a metric tensor field on M, and T is the stress-energy tensor, satisfying Einstein’s field equations. Einstein’s ‘point-coincident argument’ is re-affirmed for the metric tensor: , where the letters ‘i’, ‘j’ are just labels for the values of the indices without any physical significance. The class of models is diffeomorphism-invariant means: is a model of the theory if and only if is also a model for a smooth one-to-one mapping or diffeomorphism. (Cf. Healey 2003: §4; Rickles 2008: Ch. I) What remains invariant between these transformations is generally regarded as a candidate for the physically real:

In general the physically significant properties of a theory’s models are those which are invariant under arbitrary diffeomorphism. (Norton 1989: 1228; cf. Norton 1992)

What are the invariants of the space-time models? The space-time interval

ds, in the presence of a gravitational field, now takes the general form:

where the

are functions of the generalized coordinates

for four-dimensional space-time. It is now this more general relation, which must remain covariant with respect to ‘arbitrary continuous transformations of the coordinates.’ (Einstein 1950; Einstein 1920: 154) Whilst it is true that temporal (and spatial) measurements are ‘relative’, this is not true of the space-time interval

ds. The space-time interval is invariant in the sense that

, that is the space-time interval remains invariant in the change from one to another coordinate system.

For some authors, this feature does not extend to the notion of time. The fact that the General theory is a gauge theory means that, due to its symmetries, the theory has a mathematical structure, which cannot simply be read as reflecting physical reality. From the structure of the General theory as a gauge theory these authors infer the ‘unreality of time’.

2. John Earman, for instance, has offered a reformulation of McTaggart’s argument for the unreality of time in the General theory:

(P1’) There must be physical change, if there is to be physical time. (This premise harks back to the relationism of Saint Augustine and Leibniz.)

(P2’) Physical change occurs only if some genuine physical magnitude (a.k.a. “observable”) takes on different values at different times.

(P3’) No genuine physical magnitude countenanced in the General theory changes over time.

From (P2’) and (P3’) Earman arrives at his first conclusion:

(C’) If the set of physical magnitudes countenanced in the General theory is complete, then there is no physical change.

And from (P1’) and (C’) he arrives at his second conclusion

(C’’) Physical time as described by the General theory is unreal. (Earman 2002: 5)

This argument has attracted much critical commentary:

(…) we can have no empirical reason to believe such a theory if it cannot explain even the possibility of our performing observations and experiments capable of providing evidence to support it. And in the absence of convincing evidence for such a theory we have no good reason to deny the existence of time as a fundamental feature of reality. (Healey 2002: 308; cf. Healey 2002; Maudlin 2002; Rickles 2008: Ch. 7)

What is of interest in the present context is that according to Earman the frozen dynamic of the General theory implies the unreality of time; i.e. Earman infers the unreality of time from the mathematical structure of the General theory. To consider whether there is change (in the sense of McTaggart’s B-series), Earman focuses on the ‘mathematical and perceptual representation’, rather than on the physical world itself. (Earman 2002, §9) In this argument Earman seems to commit the mistake of deducing the presumed nature of space-time (its unreality) from the mathematical structure of a scientific theory. This move is similar to the move from the lack of simultaneity to the unreality of time in the STR. This is a surprising move since no philosophical claims about the nature of time can be deduced from the structure of a scientific theory because they are not built into its principles. Thus Earman arrives at the conclusion (C’’) which is supposedly true because of the mathematical structure of GTR.

But are the premises in Earman’s reconstruction correct? Is premise P2’ true? As observed above gravitational time dilation is an observable which takes on different values at different times. Hence some ‘genuine physical magnitude – clock time – does change. In STR time dilation means that each observer sees the other observer’s clock run slow. In GTR time dilation means that the observer on top of a tower sees the clock on the ground run slower and the observer on the ground sees the higher clock run fast.

The premise (P3’) is not only questionable but plainly false. This is because the metric tensor is position-dependent, that is it is dependent on the location of the coordinates in the metric field. This marks an important difference with the global metric tensor in STR: which is not position-dependent. These expressions mark the difference between the dynamic space-times of the GTR and the flat, constant space-time of the STR (Minkowski space-time).

As is well known, false premises invalidate the conclusion. From the point of view of the present discussion such arguments leave out important considerations concerning the measurement of time in gravitational fields, as well as various invariants of the theory. Thus the space-time interval ds also play an important part in the GTR because of its relation to proper time.

The space-time interval, ds, is useful for the measurement of time, in flat as well as curved space-time, in the sense that it allows observers to calculate their respective clock times. The twin thought experiment can be represented both in an STR version – where acceleration and deceleration are neglected and a GTR version – where the differential aging is attributed to the change of reference frame of the second twin. This fact in itself should make us hesitant about drawing the conclusion that time is unreal. These observers can calculate the respective ticking of their clocks and the elapsed time they would measure for certain intervals between two events (p, q) on their respective world lines; and hence there is no reason for them to conclude that time is unreal. The only permissible inference from the effects of time dilation due to frame velocity and gravitational effects is that the ticking rates of clocks are affected differentially, due to the location of the clocks in the gravitational fields and path-dependence of clock time, resulting in the difference between proper and coordinate time. The very fact that from their respective world lines the observers can compute and predict the ticking of clocks on other world lines seems to suggest that time cannot simply be a human illusion.

The space-time interval has physical significance since it is related to proper time both in Minkowski space-time:

and curved space-time, where the metric,

now depends on the chosen coordinates. In curved space-time, the relevant relation is the gravitational time dilation (Cheng

22010: 101):

In this situation, a stationary clock is used as a standard clock, Φ=0, which ticks at a fixed rate, t. The time intervals , which are measured by clocks placed at other locations (the proper time interval at ), is related to this coordinate interval dt, as in equation (4) Hence the difference between coordinate time and proper time is important in both the STR and the GTR.

A further invariant, which supports an objective notion of time, is due to thermodynamic parameters. Here the above-mentioned second invariant, entropy, comes into play. In the light of what has been said before the question boils down to the role of thermodynamic variables in gravitational systems.

In his thought experiment Einstein identified the irreversible process of signal propagation with ‘the arrow of time.’ The observer at

P (in Einstein’s thought experiment,

Figure 4) would be entitled to infer that his local passage of events indicated the anisotropy of time in his local neighbourhood. The increase in entropy in thermodynamic systems is a regular process – based on the Second law of thermodynamics – but the crucial point is that entropy is frame-invariant. In fact, in thermodynamic systems, moving with velocity,

v, several thermodynamic parameters remain invariant. According to Max Planck (1907), the following invariant relationships hold in relativistic thermodynamics:

The frame-invariance of entropy means that in both systems, moving inertially with respect to each other, the entropy of a body in thermodynamic equilibrium increases in a similar way and is not dependent on the velocity of the body. (Møller 1972: 237; Landsberg 1978: Ch. 18.5) Entropy is thus Lorentz-invariant and depends on the internal micro-state of the system. This can be seen directly from the definition of entropy in statistical mechanics:

The number of microscopic states, N, which correspond to a given macro-state, does not depend on the velocity of the thermodynamic system. This feature of thermodynamic systems would give observers in different coordinate systems the possibility of taking the rise in entropy of a body as a basis for measuring the passage of time. The Lorentz-invariance of entropy in statistical mechanics is derived from the definition of entropy:. As N = No – so that the number of microstates, N, does not depend on the velocity of the thermodynamic system - we also have, and hence the invariance of entropy . It follows from this equation that when the entropy reaches a certain state in one system, by the spreading of microstates into the available phase-space, two observers can perform a prearranged action in their respective systems simultaneously. Note that the spreading of the microstates into the available phase space is a function of time, and this spreading of microstates into phase-space occurs at the same rate. The spreading rate can therefore be used to define an entropy clock, Σ. Hence observers in two relativistically moving systems can use the rate of spreading of the microstates, which according to the equation, S = So, must be invariant, as a way of measuring the objective, frame-independent passage of time. Even the fact that one of the two systems, with an entropy clock Σ’ attached to it, must be accelerated to reach its relativistic velocity does not change the invariant rate of entropy increment, , in the accelerated system. If we consider the velocity increase in the Σ’-clock as , then the invariance theorem can be written as , and hence the change in velocity has no effect on .

The invariance of, say, pressure and entropy extends to gravitational systems. By the equivalence principle of the General theory, accelerating systems are equivalent to gravitational systems, and hence the relation should apply in this case. Thermodynamics in curved space-time is the same as in flat space-time, whether it be relativistic or classical. Hence, we find the same invariants as encountered before. (Misner et al. 1973: Ch. 22; Cheng 22010: Ch. 10)

Even in an expanding universe, there is energy conservation. Hence two observers in curved space-time find themselves in the same situation as those in flat space-time. And by the above arguments they are able to measure the passage of time, objectively, by the use of thermodynamic clocks.

We must take it, then, that the Σ’-clock while being accelerated gains the same increments which comparableΣ clocks are gaining; if it were otherwise, entropy would not be independent of velocity. In the limiting case of zero velocity increments, we must also have the same entropy increments for the Σ and Σ’ clocks, and hence also the same increases in clock readings. We conclude that similar entropy clocks, in relative uniform motion, will run at the same rate. (Schlegel 1968: 148; cf. Schlegel 1977)

Two observers who use entropy clocks will know that the invariance of S ensures both an objective measurement of the passage of time in their respective systems and the simultaneous performance of pre-arranged actions in their respective systems. It is important to stress that these considerations do not question the validity of the relativity principle and do not give rise to notions of ‘absolute simultaneity’ or motion. Thermodynamic invariants, like pressure or the number of micro-states, reveal no information about the motions of the observers. Nor do thermodynamic clocks show the ‘correct’ time but are simply particular physical systems amongst other physical clocks. It remains true that there are as many clocks as there are reference systems. But thermodynamic clocks show that, if relativistic thermodynamics is taken into account, new invariant relationships come to light, which can be exploited for the objective measurement of the passage of time in relativistic systems.