Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Related Work

4. Methodology

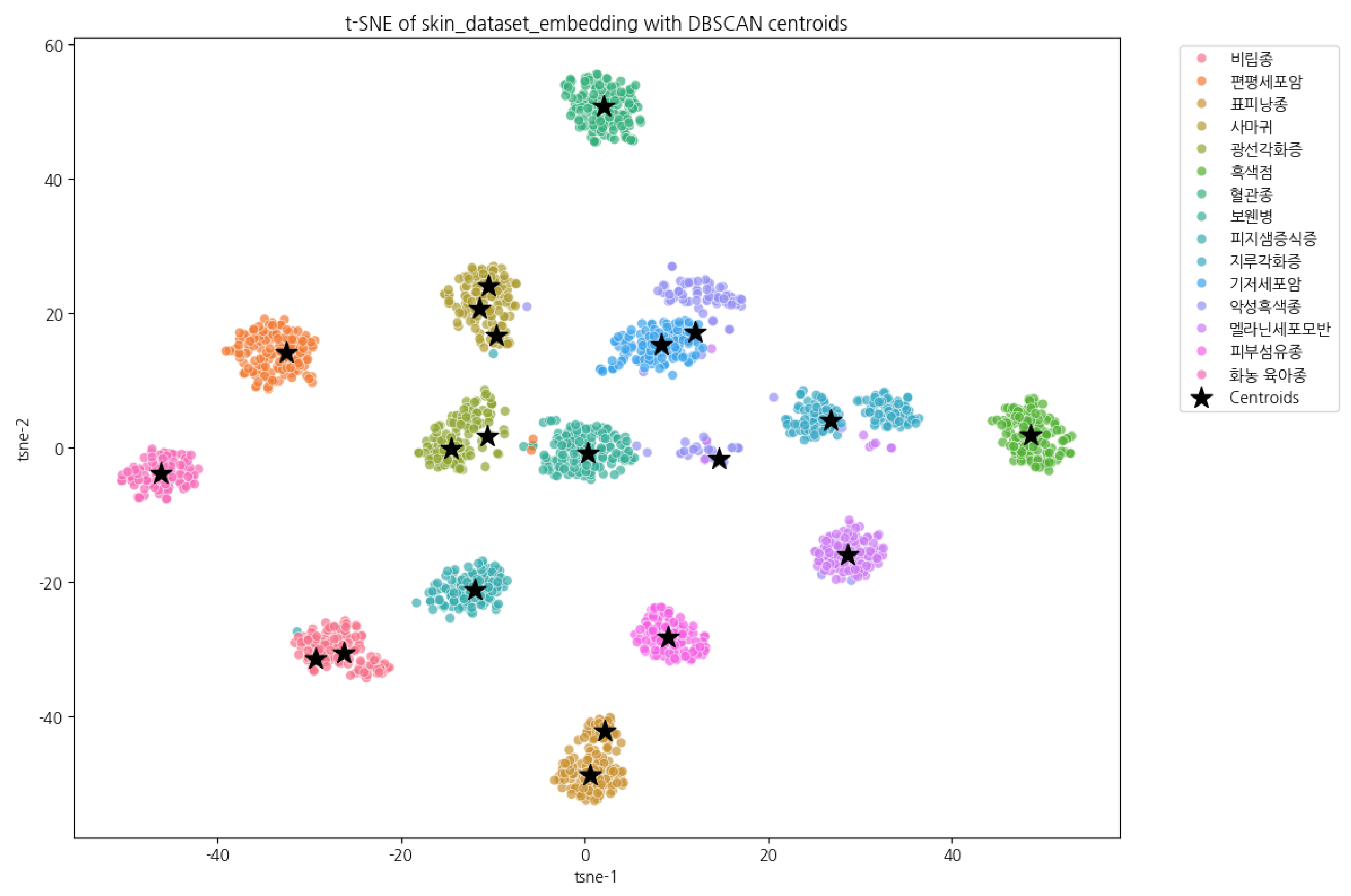

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Dataset Preprocessing (1) Generation of Disease Descriptions

| Korean Original Prompt | English-Translated Prompt |

|---|---|

|

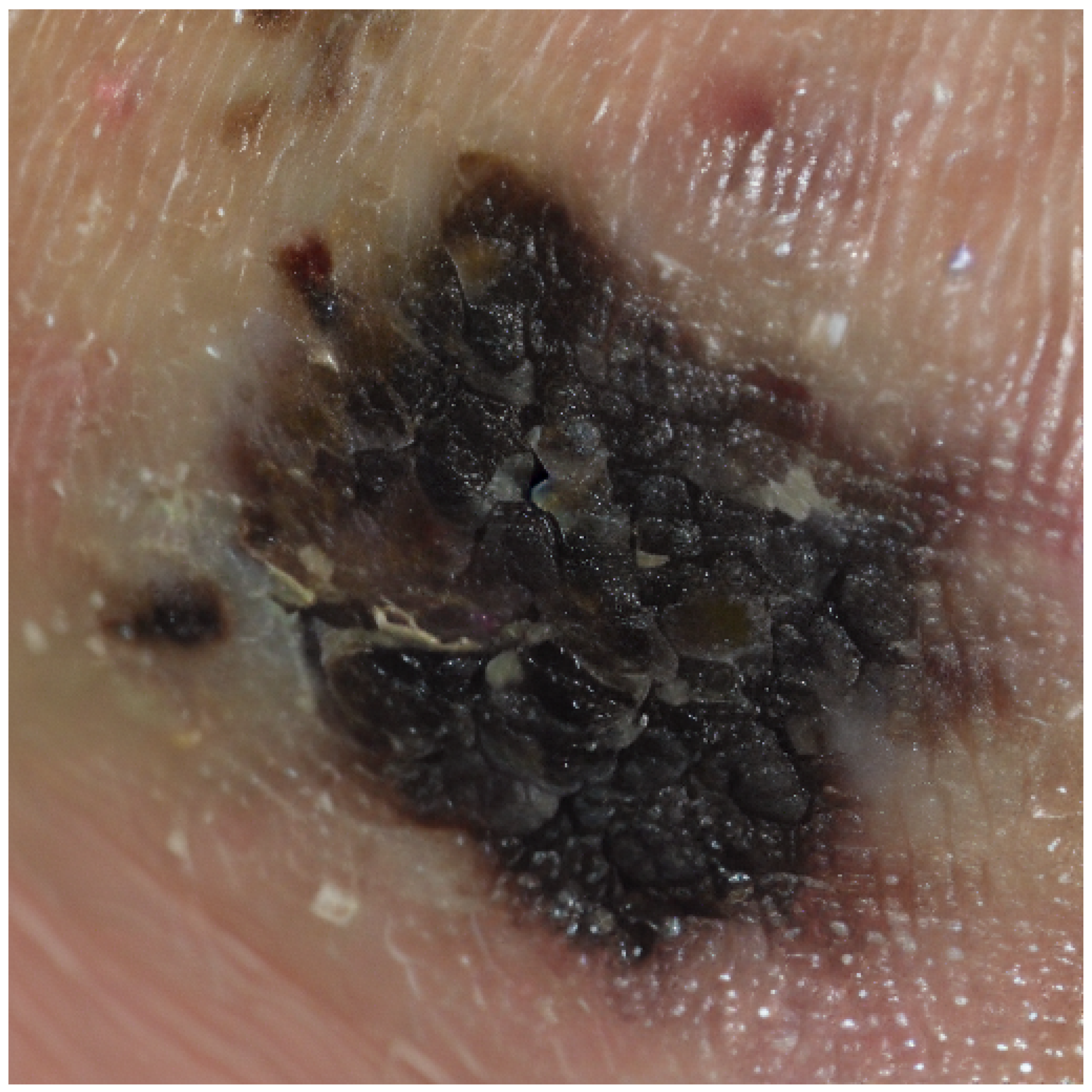

너는 피부 병변을 진단하는 전문 AI이다. 다음은 네가 진단할 수 있는 피부 병변 목록이며, 각 병변의 임상적 특징은 아래와 같다. 환자에게 나타난 병변의 이미지와 설명을 바탕으로 가장 적합한 질병을 하나 선택하여 진단하라.

아래 진단 기준을 참조하여 이미지에서 어떤 특징이 해당 질병의 특징에 해당하는지 설명하라. 각 질병의 특징은 다음과 같다: ... (중략)... 악성흑색종 - 색상특징: 비균일한 검정, 갈색, 붉은색 혼합 - 비대칭성: 모양이 비대칭이며 경계가 불규칙함 - 병변변화: 빠르게 크기 증가 및 색 변화 가능 - 전이가능성: 림프절 및 전신으로 빠르게 전이 - 생존율: 조기 발견 시 생존율 높지만, 진행 시 예후 불량 ...(중략)... <label>질병명</label> <summary>질환설명</summary> |

You are an AI system specialized in diagnosing dermatological lesions. The following list presents the skin conditions that you are capable of identifying, along with their corresponding clinical characteristics. Based on the patient’s lesion image and the accompanying description, select the single most appropriate diagnosis. Refer to the diagnostic criteria below and explain which features observed in the image correspond to the characteristic findings of the selected disease. The key features of each condition are as follows: ... (omitted) ... Malignant Melanoma - Color Characteristics: Uneven mixture of black, brown, and red tones - Asymmetry: Asymmetrical shape with irregular borders - Lesion Evolution: Rapid increase in lesion size and possible changes in pigmentation - Metastatic Potential: Rapid metastasis to lymph nodes and distant organs - Survival Rate: High survival rate when detected early; poor prognosis in advanced stages ...(omitted)... <label>Disease Name</label> <summary>Disease Description</summary> |

| Korean Original Example | English-Translated Example |

|---|---|

| 예시: <label>지루각화증</label> <summary> 이미지에서는 피부 표면에 갈색으로 보이며, 표면이 거칠게 융기된 병변이 관찰됩니다. 이 병변은 피부에 덧붙은 듯한 모양을 가지며, 크기가 천천히 증가할 수 있지만 대체로 양성이며 건강에 큰 문제를 일으키지 않습니다. </summary> |

Example: <label>Seborrheic Keratosis</label> <summary> In the image, a brown-colored lesion with a rough, elevated surface is observed. The lesion appears as though it is stuck onto the skin and may gradually increase in size; however, it is generally benign and does not typically pose significant health concerns. </summary> |

4.3. Dataset Preprocessing (2) Confidence Score

5. Experimental Design

5.1. Training Models, Groups, and Hyperparameters

| trainer = SFTTrainer( model = model, tokenizer = tokenizer, data_collator = UnslothVisionDataCollator( model, tokenizer, train_on_responses_only = True, max_seq_length = 4096, instruction_part = "<|im_start|>user\n", response_part = "<|im_start|>assistant\n", ), ... (omitted)... |

5.2. Dataset Splitting

5.3. Experimental Environment

6. Experiments and Results

6.1. Training and Evaluation Results

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations

9. Future Research Directions

Abbreviations

| VLM | Vision–Language Model |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| QLoRA | Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| PRC | Precision |

| REC | Recall |

| F1 | F1-Score |

References

- Esteva, Andre, et al. "Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks." nature 542.7639 (2017): 115-118. [CrossRef]

- Brinker, Titus J., et al. "Deep learning outperformed 136 of 157 dermatologists in a head-to-head dermoscopic melanoma image classification task." European Journal of Cancer 113 (2019): 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, Ashish, et al. "Attention is all you need." Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

- Radford, Alec, et al. "Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision." International conference on machine learning. PmLR, 2021.

- Sellergren, Andrew, et al. "Medgemma technical report." arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.05201 (2025).

- Li, Chunyuan, et al. "Llava-med: Training a large language-and-vision assistant for biomedicine in one day." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2023): 28541-28564.

- Ester, Martin, et al. "A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise." kdd. Vol. 96. No. 34. 1996.

- Krizhevsky, Alex, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey E. Hinton. "Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks." Advances in neural information processing systems 25 (2012).

- He, Kaiming, et al. "Deep residual learning for image recognition." Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016. (pp. 770-778).

- Russakovsky, Olga, et al. "Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge." International journal of computer vision 115.3 (2015): 211-252. [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey, et al. "An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale." arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

- Zhai, Xiaohua, et al. "Sigmoid loss for language image pre-training." Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2023.

- Liu, Haotian, et al. "Visual instruction tuning." Advances in neural information processing systems 36 (2023): 34892-34916.

- Kim, Young Jae, et al. "Augmenting the accuracy of trainee doctors in diagnosing skin lesions suspected of skin neoplasms in a real-world setting: A prospective controlled before-and-after study." PLoS One 17.1 (2022): e0260895. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Muhammad Ali, et al. "Derm-t2im: Harnessing synthetic skin lesion data via stable diffusion models for enhanced skin disease classification using vit and cnn." 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2024.

- Zhao, Chen, et al. "Dermoscopy image classification based on StyleGAN and DenseNet201." Ieee Access 9 (2021): 8659-8679. [CrossRef]

- Bridle, John S. "Probabilistic interpretation of feedforward classification network outputs, with relationships to statistical pattern recognition." Neurocomputing: Algorithms, architectures and applications. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1990. 227-236.

- Hinton, Geoffrey, Oriol Vinyals, and Jeff Dean. "Distilling the knowledge in a neural network." arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.02531 (2015).

- Huerta-Enochian, Mathew, and Seung Yong Ko. "Instruction Fine-Tuning: Does Prompt Loss Matter?." arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13586 (2024).

- Dettmers, Tim, et al. "Qlora: Efficient finetuning of quantized llms." Advances in neural information processing systems 36 (2023): 10088-10115.

- U.S. National Cancer Institute(NCI)’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program https://training.seer.cancer.gov/melanoma/intro/survival.html https://training.seer.cancer.gov/melanoma/abstract-code-stage/staging.html.

- Najungim et al. “Synthetic Skin Tumor Image Dataset.” AI Hub (constructed as part of the “Intelligent Information Industry Infrastructure Development” project supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT and the National Information Society Agency of Korea).

| Stage at Diagnosis | 5-Year Relative Survival Rate | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | 100% | Tumor cells confined to the epidermis only. |

| Stage I-II (Localized) | 97.6% | Tumor thickness (Breslow depth) . |

| Stage III (Regional) | 60.3% | tumor thickness (Breslow depth) with regional lymph node involvement. |

| Stage IV (Distant) | 16.2% | Distant metastasis to other organs. |

| Korean Original (JSON) | English Translation (JSON) |

|---|---|

|

{ "annotations": [ { "identifier": "Z4_2051_P0_L0", "diagnosis_info": { "diagnosis_name": "악성흑색종", "desc": "멜라닌세포의 악성 종양으로 진단을 위해 조직검사가 필요함" }, "generated_parameters": { ... }, "photograph": { ... }, "bbox": { ... } } ] } |

{ "annotations": [ { "identifier": "Z4_2051_P0_L0", "diagnosis_info": { "diagnosis_name": "Malignant melanoma", "desc": "Malignant tumor of melanocytes; biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis." }, "generated_parameters": { ... }, "photograph": { ... }, "bbox": { ... } } ] } |

| Korean Original Output | English-Translated Output |

|---|---|

|

<label>악성흑색종</label> <summary> 이미지에서 보이는 병변은 비균일한 검정과 갈색의 혼합색상을 지니며, 경계가 불규칙한 특징을 보입니다. 이러한 비대칭성과 색상 변화는 악성흑색종의 전형적인 특징입니다. 이 병변은 빠른 크기 증가와 색 변화 가능성을 내포하고 있으며, 림프절 및 전신으로 전이될 위험이 있습니다. 조기에 발견할수록 생존율이 높지만, 진행된 경우 예후는 불량할 수 있습니다. </summary> |

<label>Malignant Melanoma</label> <summary> The lesion observed in the image exhibits an uneven mixture of black and brown pigmentation with irregular borders. Such asymmetry and color variation are characteristic features of malignant melanoma. The lesion carries the potential for rapid growth and pigment changes and poses a risk of metastasis to the lymph nodes and distant organs. Early detection is associated with a high survival rate, whereas advanced stages may result in a poor prognosis. </summary> |

| Korean Original | English Translation |

|---|---|

|

[(’멜라닌세포모반’, 0.9672727286892795), (’피부섬유종’, 0.8325640355322497), (’지루각화증’, 0.8229875053707825), (’흑색점’, 0.803708897289274), (’표피낭종’, 0.7775588886435125)] |

[(’Melanocytic Nevus’, 0.9672727286892795), (’Dermatofibroma’, 0.8325640355322497), (’Seborrheic Keratosis’, 0.8229875053707825), (’Lentigo’, 0.803708897289274), (’Epidermal Inclusion Cyst’, 0.7775588886435125)] |

| Korean Original Output | English-Translated Output |

|---|---|

|

<root> <label id_code="0" score="67.6">광선각화증</label> <summary>이미지에서는 자외선 노출이 많은 부위인 얼굴에 붉은색의 각질성 반점이 관찰됩니다. 이는 만성 자외선 노출로 인한 DNA 손상으로 발생하며, 장기간 방치할 경우 피부암, 특히 편평세포암으로의 진행 가능성이 있습니다. 병변의 진행 속도가 느릴 수 있으나, 조기 발견 시 적절한 치료를 통해 예후를 양호하게 할 수 있습니다.</summary> <similar_labels> <similar_label id_code="3" score="16.6">보웬병</similar_label> <similar_label id_code="1" score="5.7">기저세포암</similar_label> </similar_labels> </root> |

<root> <label id_code="0" score="67.6">Actinic Keratosis</label> <summary>In the image, erythematous, scaly macules are observed on a sun-exposed area of the face. These lesions result from chronic ultraviolet-induced DNA damage and, if left untreated, may progress to skin cancer, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. Although progression may be slow, early detection and appropriate management can lead to favorable outcomes.</summary> <similar_labels> <similar_label id_code="3" score="16.6">Bowen’s Disease</similar_label> <similar_label id_code="1" score="5.7">Basal Cell Carcinoma</similar_label> </similar_labels> </root> |

| Model | Rank | Grp. | Steps | LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qwen2.5-vl-7b | 128 | A | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| gemma3-4b | 128 | A | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| qwen2.5-vl-7b | 128 | B | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| gemma3-4b | 128 | B | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| qwen2.5-vl-7b | 128 | C | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| gemma3-4b | 128 | C | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| qwen2.5-vl-7b | 128 | D | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| gemma3-4b | 128 | D | 3000 | 5e-5 |

| Group | Input | Output | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | X | O | Classification-focused transformation |

| B | X | O | Original output preserved |

| C | O | O | Classification-focused transformation |

| D | O | O | Original output preserved |

| Korean Original | English Translation |

|---|---|

|

<|im_start|>user 진단병명만 말해. <|vision_start|> <|image_pad|> <|vision_end|> <|im_end|> <|im_start|>assistant 피지샘증식증<|im_end|> |

<|im_start|>user State only the diagnosis. <|vision_start|> <|image_pad|> <|vision_end|> <|im_end|> <|im_start|>assistant Sebaceous Hyperplasia<|im_end|> |

| Korean Original | English Translation |

|---|---|

|

<|im_start|>user 0: 광선각화증 1: 기저세포암 2: 멜라닌세포모반 3: 보웬병 4: 비립종 5: 사마귀 6: 악성흑색종 7: 지루각화증 8: 편평세포암 9: 표피낭종 10: 피부섬유종 11: 피지샘증식증 12: 혈관종 13: 화농 육아종 14: 흑색점 <|vision_start|> <|image_pad|> <|vision_end|> <|im_end|> <|im_start|>assistant 11<|im_end|> |

<|im_start|>user 0: Actinic Keratosis 1: Basal Cell Carcinoma 2: Melanocytic Nevus 3: Bowen’s Disease 4: Milia 5: Verruca Vulgaris 6: Malignant Melanoma 7: Seborrheic Keratosis 8: Squamous Cell Carcinoma 9: Epidermal Inclusion Cyst 10: Dermatofibroma 11: Sebaceous Hyperplasia 12: Hemangioma 13: Pyogenic Granuloma 14: Lentigo Simplex <|vision_start|> <|image_pad|> <|vision_end|> <|im_end|> <|im_start|>assistant 11<|im_end|> |

|

lora_rank = 128, lora_alpha = 128, per_device_train_batch_size = 8, gradient_accumulation_steps = 1, warmup_steps = 5, max_steps = 3000, learning_rate = 5e-5, logging_steps = 1, eval_strategy ="steps", eval_on_start = True, eval_steps = 50, optim = "adamw_8bit", weight_decay = 0.01, lr_scheduler_type = "cosine", output_dir = "outputs", report_to = "wandb", save_total_limit = 3, max_grad_norm = 5.0, |

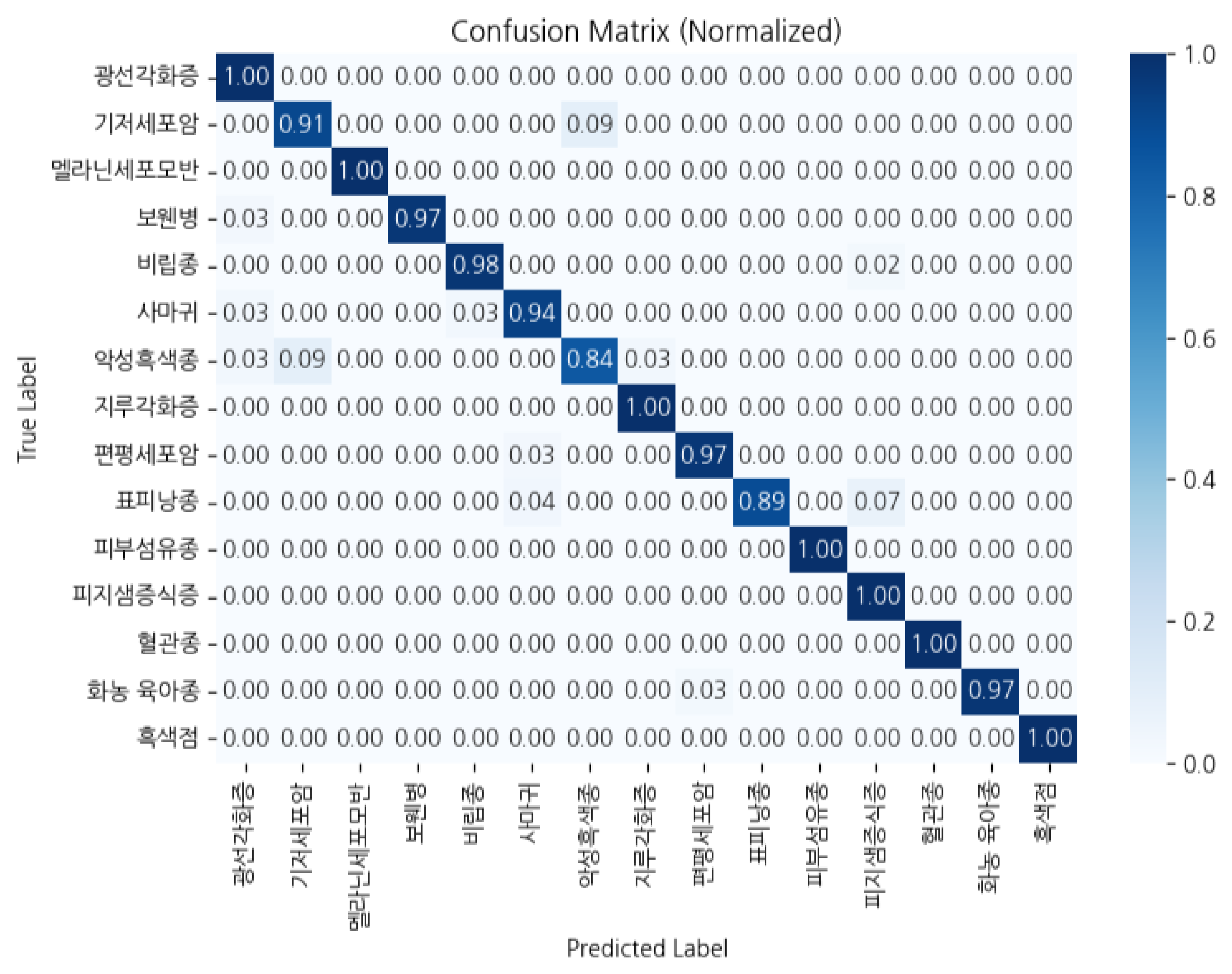

| Grp. | Model | Acc | Prc | Rec | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | qwen2.5 | .966 | .9665 | .966 | .9657 |

| A | gemma3 | .980 | .9824 | .980 | .9809 |

| B | qwen2.5 | .972 | .9723 | .972 | .9717 |

| B | gemma3 | .966 | .9679 | .966 | .9654 |

| C | qwen2.5 | .968 | .9681 | .968 | .9677 |

| C | gemma3 | .980 | .9804 | .980 | .9799 |

| D | qwen2.5 | .970 | .9702 | .970 | .9697 |

| D | gemma3 | .946 | .9525 | .946 | .9441 |

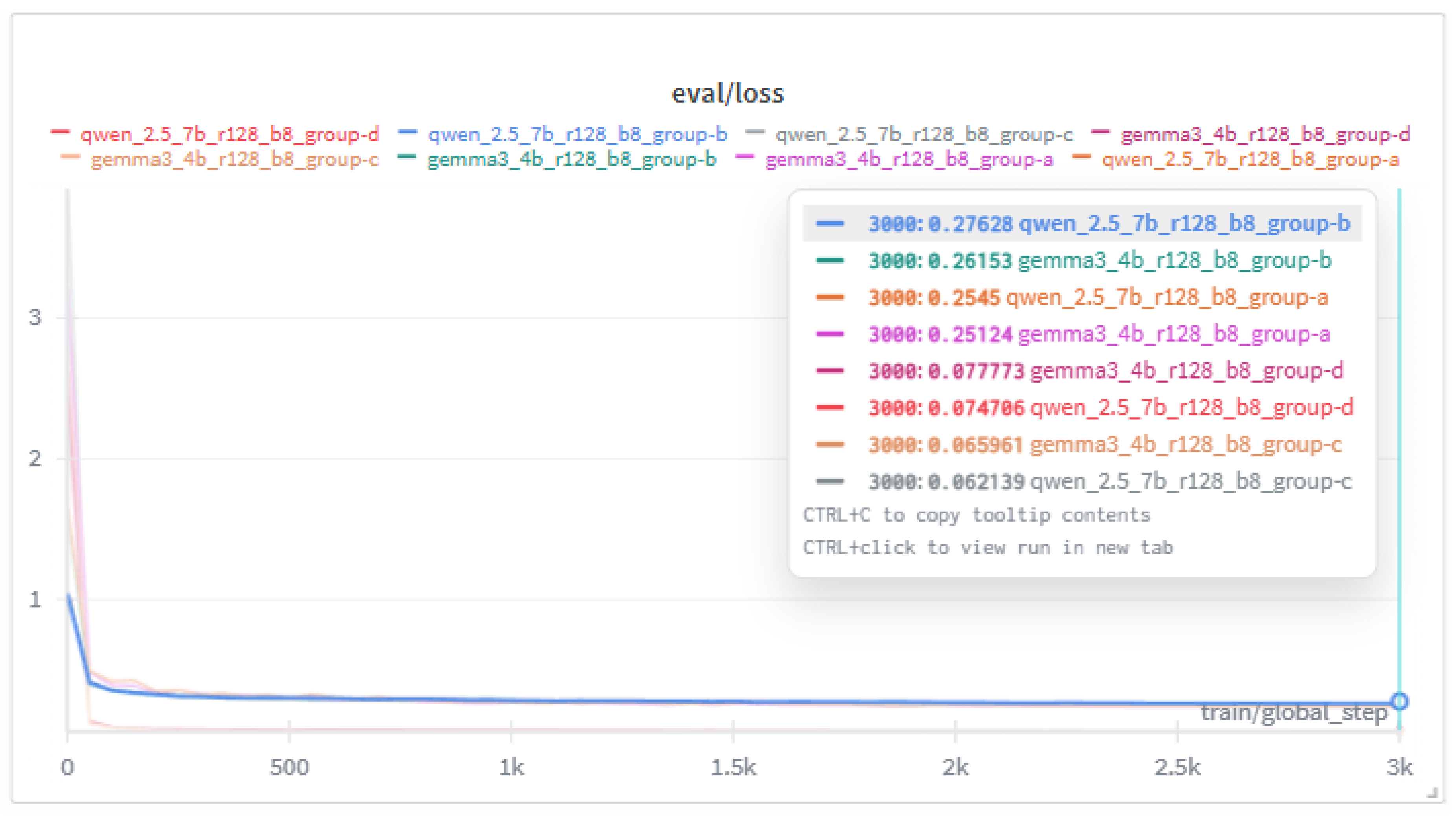

| Grp. | Model | Steps | Train/Loss | Eval/Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | qwen2.5 | 3000 | .3256 | .2545 |

| A | gemma3 | 3000 | .3123 | .2512 |

| B | qwen2.5 | 3000 | .2889 | .2763 |

| B | gemma3 | 3000 | .2899 | .2615 |

| C | qwen2.5 | 3000 | .0923 | .0621 |

| C | gemma3 | 3000 | .0968 | .0660 |

| D | qwen2.5 | 3000 | .0898 | .0747 |

| D | gemma3 | 3000 | .0913 | .0778 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).