2. Case Report

A 43-year-old male, 12 years post-right middle cerebral artery infarction, walked independently with an ActiGait (Ottobock, Duderstadt, Germany) functional electrical stimulation (FES) system but reported slow, effortful gait and left-knee “locking”. Multiple triceps surae and quadriceps BTI series gave only transient relief. Without FES, he showed drop foot, stiff-knee gait and recurvatum, matching pattern IIb of the chronic stroke typology [

7]. Given the unsatisfactory BTI response, we proposed precision CNL targeting selected motor branches. Two sessions were conducted (

Figure 1): the first addressed the soleus and medial gastrocnemius branches of the tibial nerve (CNL-1), the second targeted the rectus femoris and vastus intermedius branches of the femoral nerve (CNL-2).

Throughout his follow-up [pre-intervention (T0), six weeks after each CNL session (T1, T2), and six months after first CNL intervention (T3)], the patient underwent quantitative gait analysis (QGA), with and without FES, during 10-m straight-line walking at self-selected speed. When FES was applied, stimulation parameters (pulse width, frequency, amplitude, and trigger timing) were standardized at T0 and kept identical across all subsequent acquisitions (T1–T3).

Passive ankle dorsiflexion range of motion (ROM) was assessed in supine position (with knee flexed/ extended) with a goniometer, while muscle strength was evaluated with the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale [

8]. Spasticity of the quadriceps was rated using the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) and triceps surae using the ankle Tardieu Scale (TS) at fast speed (V3) [

9]. The clinical evaluation was carried out by the same evaluator (FC).

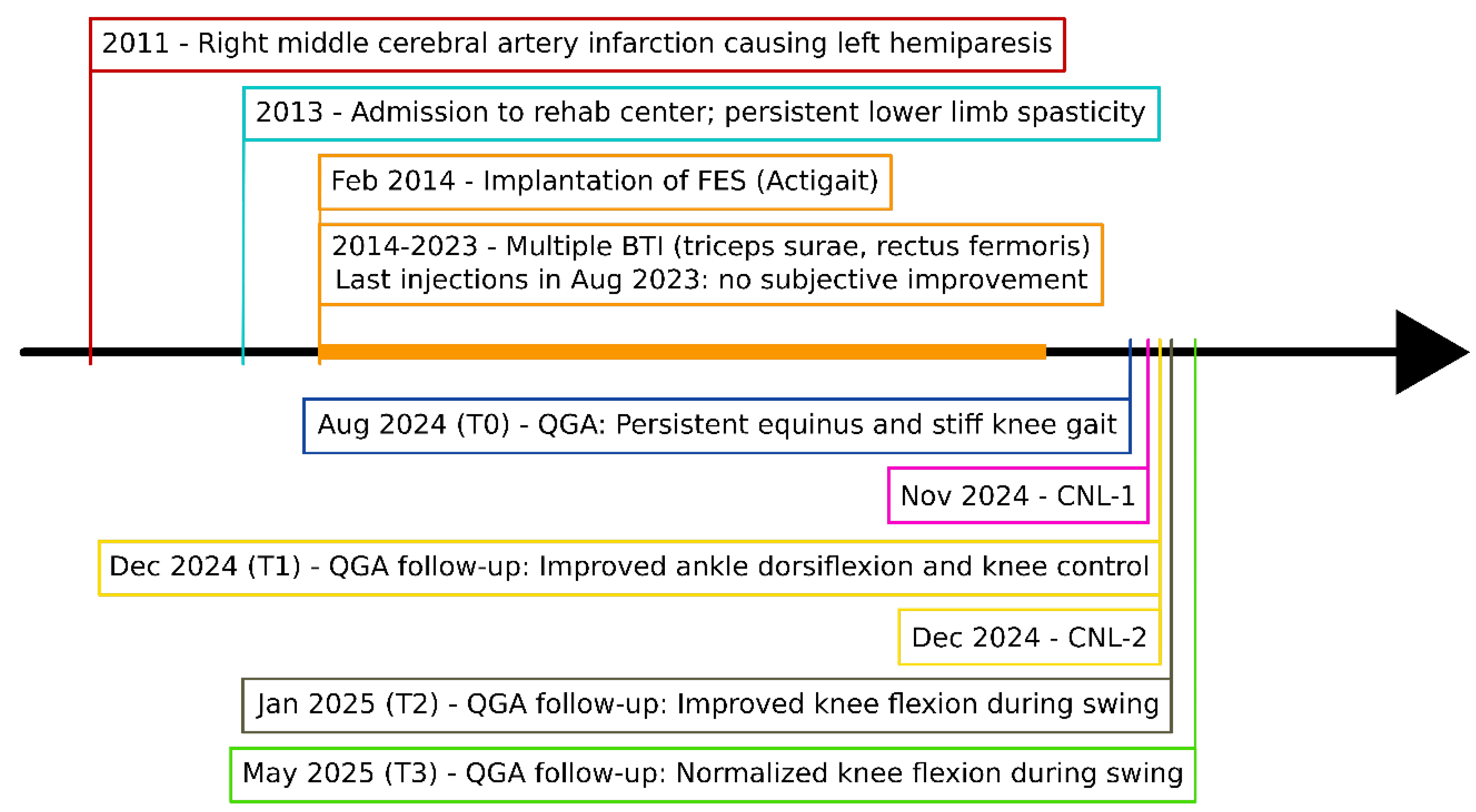

Chronological overview from index stroke (age 31) to the 6-month post-CNL assessment. BTI = botulinum-toxin injection (five gastrocnemii/soleus (100 U) and five rectus femoris (200 U) series, 2014-2023); FES = implantable common peroneal functional electrical stimulation system (ActiGait, implanted in 2014); CNL-1 = tibial-motor-branch CNL (Week 0); CNL-2 = femoral-motor-branch CNL (Week 6).

QGA included kinematics and kinetics acquired via a 10-camera optoelectronic motion capture system (Oqus4, Qualisys, Göteborg, Sweden, 200 Hz) and two force plates (OR6-5, AMTI, Watertown, MA, United States of America (USA), 2000 Hz). Five gait cycles per condition were recorded and averaged. Dynamic muscle activity was measured (TeleMyo Desktop DTS, Noraxon, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2000 Hz) using ultrasound-guided intramuscular fine-wire electromyography (EMG) targeting triceps surae (soleus, gastrocnemius medialis and lateralis) and quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus intermedius and medialis). EMG recordings were band-pass filtered (60–500 Hz) and full-wave rectified. For each muscle, we visually compared timing and burst amplitude across T0 and T2. In T0, two baseline knee patterns (recurvatum or flexion), likely reflecting fluctuations in hemiparetic motor control and compensatory strategies, were observed. Time was normalized to the gait cycle with toe-off alignment.

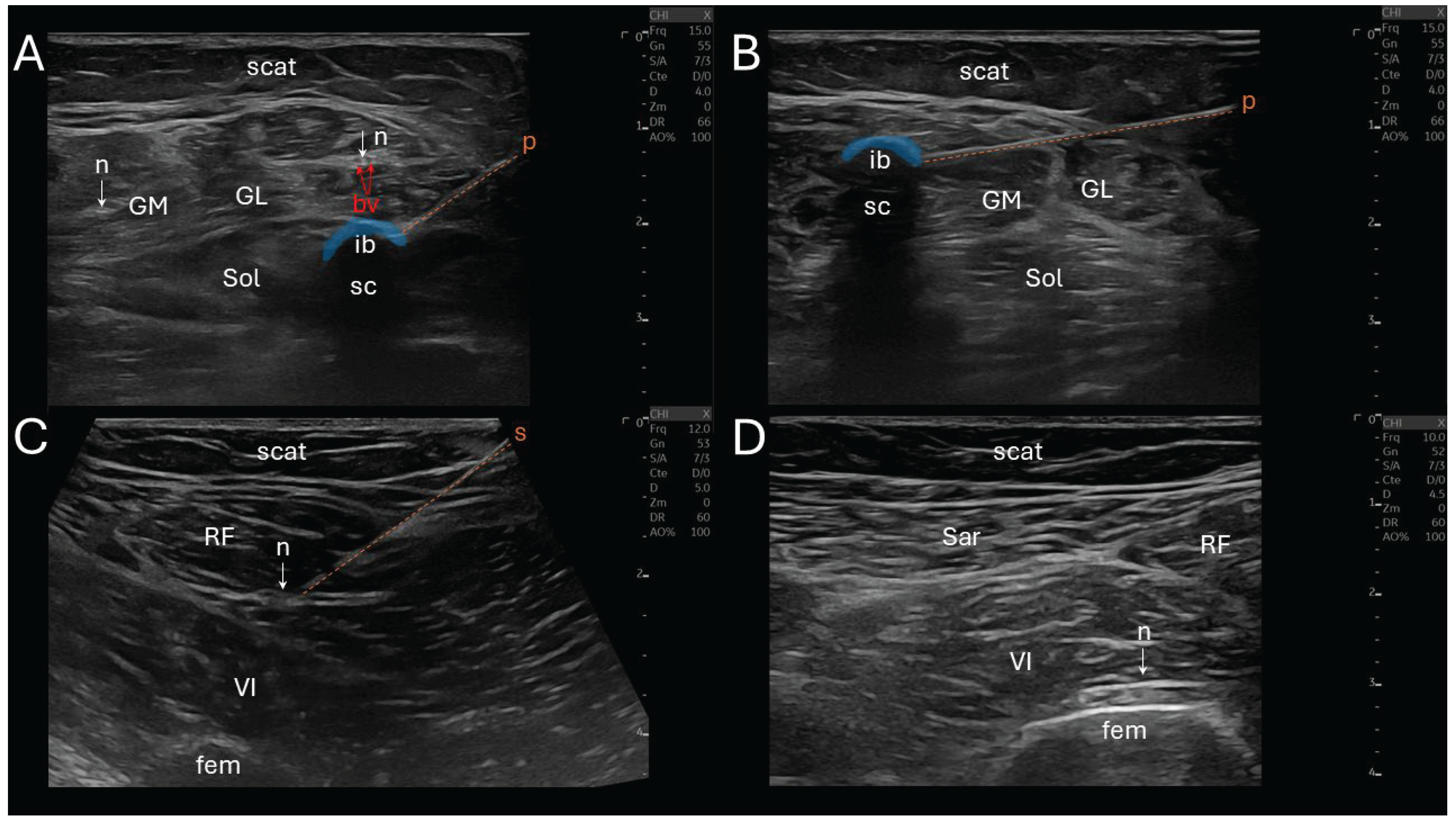

CNL was performed using a N₂O-based system (Metrum Cryoflex, Warsaw, Poland) delivering cryogenic temperatures through a 14G percutaneous cryoprobe (

Figure 2). The target motor nerve was cooled to approximately –30 °C to –40 °C to induce a controlled, reversible axonotmesis. All CNL procedures were conducted under sterile conditions, without sedation or general anesthesia, and under real-time ultrasound guidance using a linear 10-15 MHz probe (Logiq E10, General Electric, Boston, MA, USA).

The seven procedural steps of CNL (total duration ≈ 1 hour) were the following: (i) a sonographic landmarking in a transverse view, (ii) the introduction of an insulated stimulation needle (22G, 10 cm) via an in-plane technique, directing it towards the nerve trajectory, while avoiding vascular structures, (iii) a nerve stimulation initiated at 2 mA, gradually reduced to 0.5 mA to ensure close proximity to the motor fascicles (muscle contraction remains visible), (iv) needle-to-cryoprobe exchange, (v) a reconfirmation neurostimulation twitch via the cryoprobe prior to freezing, (vi) the CNL phase (first cycle: 2 minutes continuous freezing, thawing: 45 seconds, second cycle: another 2 minutes freezing) creating an ellipsoidal anechoic ice ball and its posterior acoustic shadow cone at the tip of the cryoprobe, and (vii) a post-lesion stimulation was performed to confirm temporary denervation (absence of evoked muscle contraction at 1 mA). If the nerve still responded to this stimulation, a supplemental freezing of 2 minutes was applied.

The stimulation of the soleus was performed proximally, 2-3 cm distal to the popliteal fossa, in two points, medially and laterally close to the tibial nerve. The gastrocnemius medialis stimulation was performed slightly more proximally, intramuscularly. The rectus femoris and vastus intermedius stimulations were also performed proximally, distal to the inguinal ligament, laterally close to the femoral nerve, and the vastus intermedius stimulation required a deeper insertion.

Baseline clinical examination (T0,

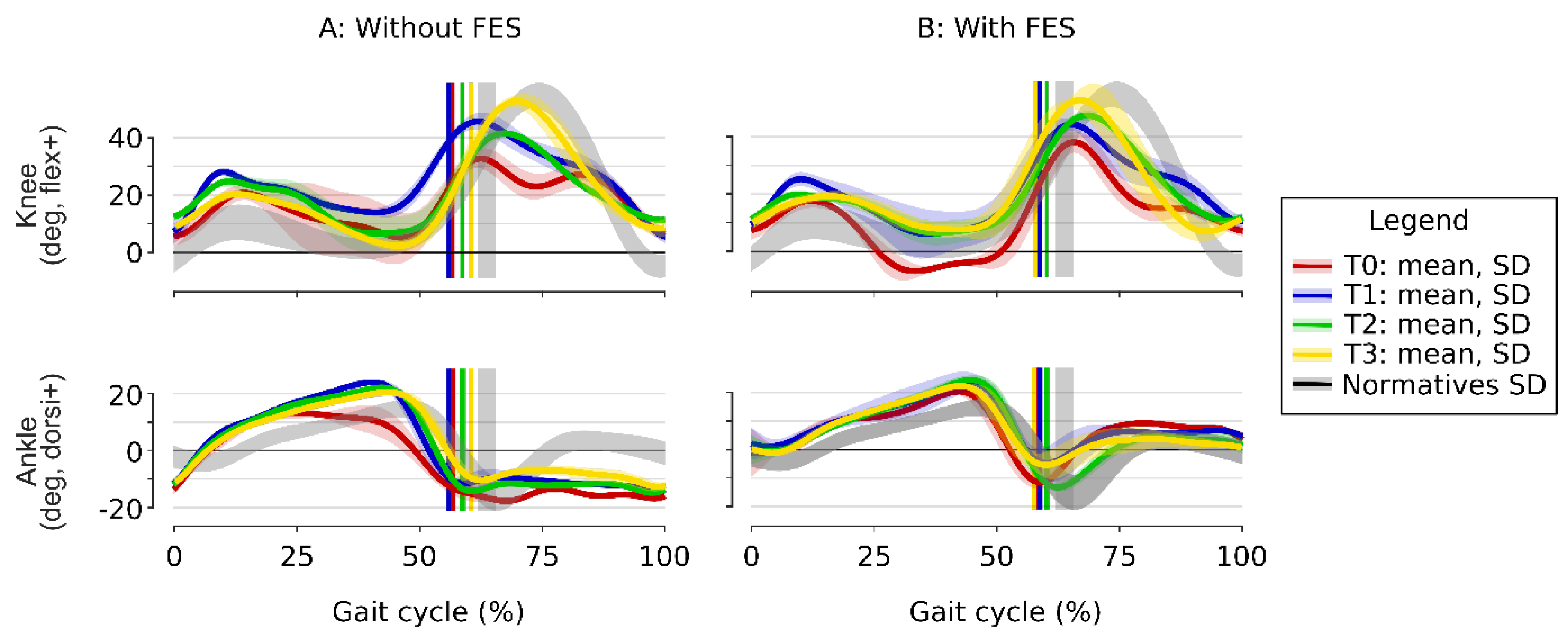

Table 1) reveals normal passive ankle dorsiflexion ROM and preserved sensory function. MRC indicated normal knee extensors’ strength and reduced ankle plantar flexors’ strength. Spasticity was observed for quadriceps and triceps surae. TS revealed dynamic ankle clonus triggered at –30°. Kinematics (

Figure 3, red) show ankle plantar flexion in swing, knee hyperextension in stance and a stiff-knee gait pattern in swing. The knee kinematics showed marked stance-phase variability (important standard deviation), with a knee sometimes flexed, sometimes extended, varying from one walking cycle to another. GGI and GDI scores confirmed a globally pathological gait. FES improved dorsiflexion during swing (9.3°), but increased knee hyperextension (genu recurvatum) (–6.8°). The gait velocity was 0.92±0.05 m/s without FES and 0.97±0.04 with FES.

After the CNL-1 (T1), without FES (

Figure 3A, blue), ankle dorsiflexion improved during stance phase: peak dorsiflexion increased from 13.1±1.9° to 24.0±0.8° in the second rocker, with better knee control resulting in less variability and less knee hyperextension. During swing, peak knee flexion improved from 32.8° to 45.7°, despite persistent ankle plantar flexion. With FES (

Figure 3B, blue), and during swing, ankle dorsiflexion improved and knee flexion remained above 40°, and during stance, genu recurvatum disappeared. The patient reported improved walking comfort and confidence, particularly during transitional movements and turning. GGI and GDI scores (

Table 1) mirrored the kinematic gains: GGI dropped in the no-FES and FES conditions, while GDI rose in both test conditions. Spasticity of the triceps surae was reduced, with dynamic ankle clonus triggered at –5°. The gait velocity was stable, 0.88±0.07 m/s without FES and 1.00±0.03 with FES.

After the CNL-2 (T2) of the femoral motor branches (

Figure 3A, green), ankle kinematics remained stable, with preserved improvements from CNL-1 (blue) with and without FES. Knee kinematics showed an increase in peak knee flexion during swing from 44.3° without FES to 47.4° with FES (

Figure 3B, green). Therefore, the stiff-knee gait pattern was, by definition [

12], completely corrected in the two conditions since the peak knee flexion in swing was over 40°. GGI remained clearly below baseline and GDI stabilized (

Table 1), indicating that the overall gait pattern, although slightly regressed without FES, was still markedly closer to normal in both test conditions (with and without FES) compared to T1. No more spasticity was observed for quadriceps. The gait velocity was stable, 0.92±0.06 m/s without FES and 1.03±0.03 with FES.

At follow-up (T3,

Figure 3, yellow), ankle kinematics remained stable, while knee kinematics improved further and were very close to the normative values, with a knee flexion in swing of 53.5°. The GGI and GDI improvements were consolidated (

Table 1).

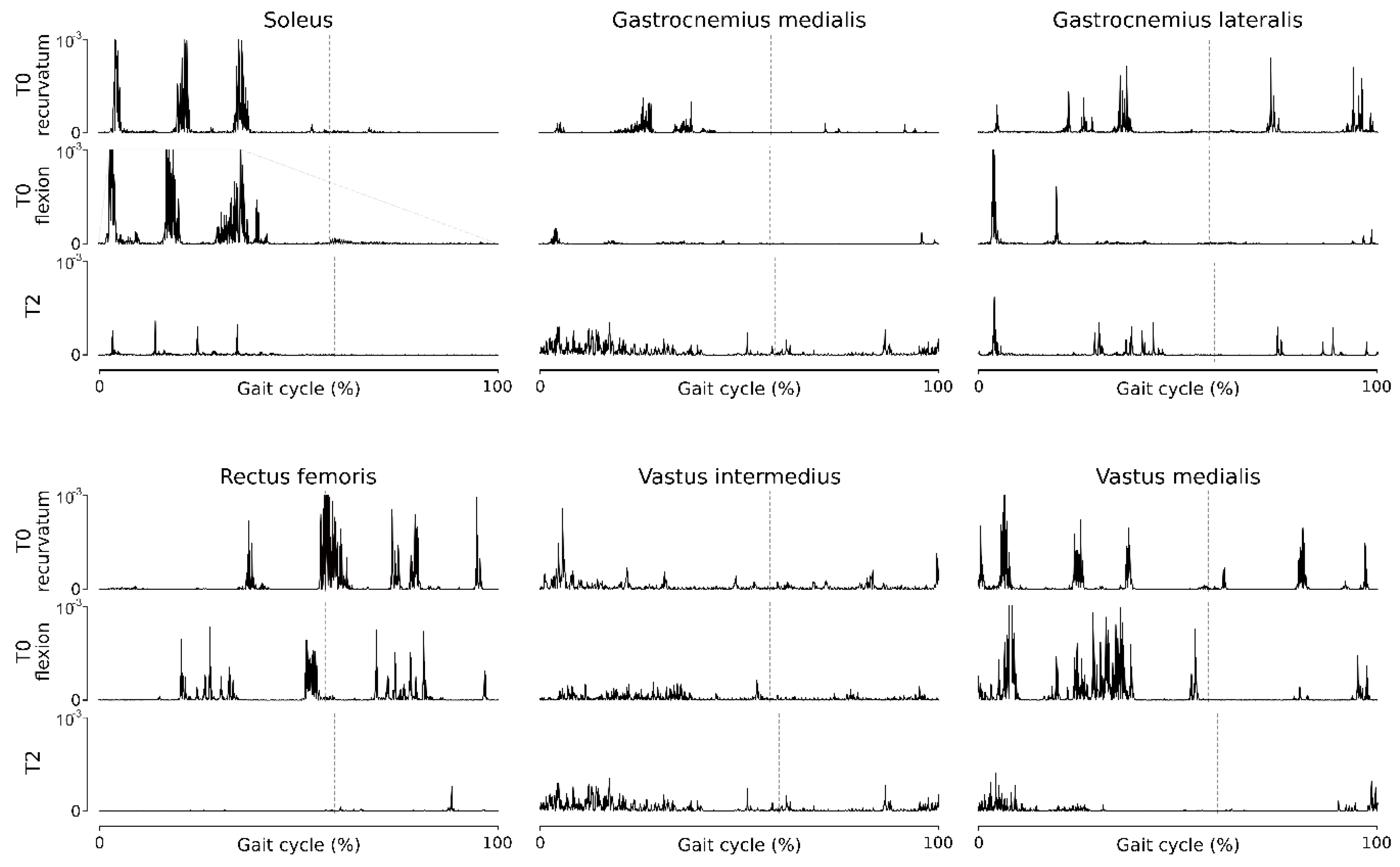

Fine-wire EMG at T0 (

Figure 4) showed two types of behaviors related to the two different knee kinematic strategies (recurvatum or flexion) in stance phase, with greater quadriceps activity when the knee is flexed. The triceps muscles exhibit hyperactivity during stance phase, responsible for the recurvatum, and the quadriceps muscles, especially the RF head, exhibit hyperactivity in the pre-swing and early swing, causing stiff knee. After the two stages of CNL (T2), fine-wire EMG revealed substantial decrease in soleus and rectus femoris activity throughout the gait cycle, and no change in gastrocnemii and vastus intermedius activities.

The patient tolerated both CNL interventions well. There were no reported adverse events or unexpected reactions, no signs of neuropathic pain, dysesthesia or muscle weakness, and no functional decline or compensatory gait deviations. The patient completed all follow-up assessments and remained adherent to gait training with FES and routine rehabilitation. The patient’s perspective was the following: “After the last injections of botulinum toxin, I felt like nothing was improving anymore. My leg remained stiff and heavy, especially around my ankle and my knee. I started to lose confidence in walking, even with FES. When the CNL was proposed, I didn’t really know what to expect, but the procedure was quick, and I felt no pain at all after the technique. A few minutes later, I could really feel the difference. Walking became easier, and the knee didn’t lock as much. I feel more stable, especially when turning or walking longer distances. For the first time in a long time, I’m walking without constantly thinking about how to avoid falling.”

3. Discussion

When compared with BTI, a practical benefit of CNL is its longer therapeutic horizon. Across mixed etiologies, clinical series summarized in a recent review, report tone-reduction that persists during 6-17 months in 60-70% of treated nerves, with only rare sensory sequelae [

4]. By contrast, pooled randomized control trial data place the median functional benefit of BTI at 12-16 weeks despite repeat dosing [

1,

2,

3], while chemical neurolysis (alcohol and phenol) offers variable 3-6-month relief at the cost of neuritis and myonecrosis [

4]. The immediate onset and the longer CNL therapeutic duration, when compared to BTI, stems from its reversible axonotmesis: Wallerian degeneration abolishes pathological firing immediately, yet the preserved endoneurial scaffolding requires several months for axonal regeneration and myelin remodeling [

5]. In addition, unlike BTI, which acts only on the efferent component of the uninhibited sensorimotor loop, CNL directly modulates both afferent and efferent pathways — addressing the reflex hyperexcitability at the core of spasticity. Together, these mechanisms yield four clinical advantages: (i) fewer treatment visits are necessary; (ii) no cumulative-dose ceiling or antibody risk exists; (iii) a stepwise therapeutic approach is feasible; and (iv) enhanced synergy with adjunct technologies is possible: the multi-month antagonist quieting, seen here, expanded the effectiveness window of the implanted foot-drop stimulator — something that a short-acting BTI could probably not achieve.

The present case extends the emerging CNL literature in four ways. First, it is consistent with the reversible-axonotmesis model established histologically [

5]. The large fall in EMG power, the parallel drop in MAS scores, and the preservation of voluntary strength jointly indicate that CNL silenced the targeted motor branches but did not definitively denervate it. This distinguishes cold-induced block from phenol neurolysis, whose unpredictable myotoxicity can blur the boundary between paresis and tone reduction [

4]. Second, the kinematic and composite gait data demonstrate that neural silencing translated into functionally relevant, whole-gait change. At six months, the GDI had climbed from 69 to 80, placing the patient within two SD of normative adult gait; concurrently, the GGI fell by more than 55%. Both shifts exceed the adult minimal detectable differences reported by [

10,

11]. A GDI of 80 also lies at the upper boundary of the “independent community ambulator” corridor identified by [

2], linking laboratory gain to real-life walking ability. Third, the study is the first to show that CNL and an implanted ankle/foot dorsiflexors stimulator can act synergistically. Activating the FES device reduced GGI by a further 23-40%, implying that debulking antagonist tone enlarges the biomechanical “window” in which a neuro-prosthesis can operate. This interaction is clinically relevant, as many chronic stroke survivors who reach the therapeutic ceiling of BTI subsequently rely on orthotic or neuroprosthetic aid. Fourth, the pairing of CNL with full-wave rectified EMG patterns and global gait indices offers a reproducible evaluation framework. Unlike isolated spasticity scores, the combined approach bridges changes in motor-unit firing, joint kinematics and integrated gait quality, aligning with current calls for precision, multi-scale outcome measurement in post-stroke rehabilitation [

1,

13,

14].

The report is not without limitations: single-case design, unblinded assessors and six-month follow-up constrain external validity. Nevertheless, the effect sizes surpass accepted minimal detectable changes for GDI (around 5 points) [

11]. Future controlled series should benchmark CNL against repeat BTI cycles, include dynamometry to track re-innervation, and incorporate patient-centered metrics such as the Modified Gait Efficacy Scale [

15].