1. Introduction

Achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on inclusive and equitable quality education, alongside SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth, remains a persistent challenge in marginalized and remote regions where access to learning resources and skilled instructors is limited. Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) has been identified as a strategic driver for addressing these disparities, yet participation and access remain uneven (Plance, 2020; Alla-Mensah, Henderson, & McGrath, 2021). Recent evidence underscores that education—particularly vocational and skills-based learning—plays a significant role in reducing poverty and advancing sustainable development across developing contexts (Zhang, 2024). However, systemic barriers such as poor infrastructure, limited technology adoption, and insufficient curriculum alignment with sustainability frameworks continue to hinder progress toward SDG targets (Pham Xuan & Håkansson Lindqvist, 2025; Vladimirova & Le Blanc, 2015).

Figure 1 illustrates the full set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), highlighting SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) as the core focus of this study. These two goals are closely interconnected in the context of vocational education: SDG 4 emphasizes equitable access to quality learning, while SDG 8 promotes skill development and employment opportunities. The visualization underscores how the PWA-based intervention contributes simultaneously to improving learning quality and enhancing youth employability in marginalized regions.

Digital innovations have become essential in overcoming these challenges. Studies demonstrate the potential of online learning ecosystems—such as MOOCs—to support SDG 4 by expanding reach, flexibility, and inclusivity (Islam, Akter, & Knezevic, 2019). Broader digital transformations in education similarly contribute to accelerating SDG achievement, enabling more adaptive, accessible, and data-driven learning models (SM, 2025; Maheshkar et al., 2024). In the context of vocational education, emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence have been shown to enhance skill development pathways and labor-market alignment, contributing directly to SDGs 4 and 8 (Prasetya et al., 2025). These advancements reflect a broader shift toward reimagining education systems to prepare the workforce for rapidly evolving economic landscapes (Fung & Hosseini, 2023).

Despite these developments, technology-enabled solutions must be designed to function in low-resource environments, especially in regions where connectivity, device performance, and digital literacy remain major constraints. Progressive Web Applications (PWAs) represent a promising avenue to bridge this gap. PWAs provide reliable, fast, and engaging user experiences by combining the accessibility of web applications with the capabilities of native apps, while operating efficiently under limited connectivity conditions (Hume, 2017; Hajian, 2019). Prior research highlights PWAs’ potential in offering unified and cost-effective application development for diverse devices (Biørn-Hansen, Majchrzak, & Grønli, 2017) and indicates that their effectiveness can be systematically assessed through multi-criteria decision models such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (Khan, Al-Badi, & Al-Kindi, 2019).

Given the intersection between the urgent need to expand vocational education access and the technological affordances provided by PWAs, there remains a critical research gap in understanding how PWAs can serve as a transformative tool for advancing SDG 4 and SDG 8 in marginalized regions. While literature emphasizes technology’s role in supporting sustainable development and education quality (Saini et al., 2023), few empirical studies provide direct evidence on the integration of PWAs within vocational school ecosystems—particularly in geographically disadvantaged areas.

This study addresses this gap by examining the implementation of a Progressive Web Application designed to support teaching, learning, and skill assessment in vocational schools located in marginalized regions. Through evaluating its effectiveness, usability, and contribution to educational and economic outcomes, this research provides new insights into how PWAs can operationalize the principles of SDG 4 and SDG 8, offering both practical and policy-oriented implications for scaling equitable vocational education.

2. Method

2.1. Research Design

This study adopted a mixed-methods explanatory sequential design to investigate the effectiveness of a Progressive Web Application (PWA) in supporting vocational education and advancing SDG 4 (quality education) and SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) in marginalized regions. Mixed-methods approaches are particularly valuable for capturing complex interactions between technology adoption, educational equity, and socioeconomic constraints—factors widely discussed in the literature on digital inclusion and rural development (Kyrylov et al., 2024; Otieno, Kaye, & Mbugua, 2023). The quantitative phase measured changes in learning outcomes, engagement, and usability, while the qualitative phase explored user experiences and the socio-structural challenges that shape technology effectiveness in disadvantaged communities, consistent with research emphasizing the need for context-sensitive interventions in marginalized populations (Moazzem & Shibly, 2020; Mir et al., 2020; Ticona Machaca et al., 2025).

2.2. Research Setting and Participants

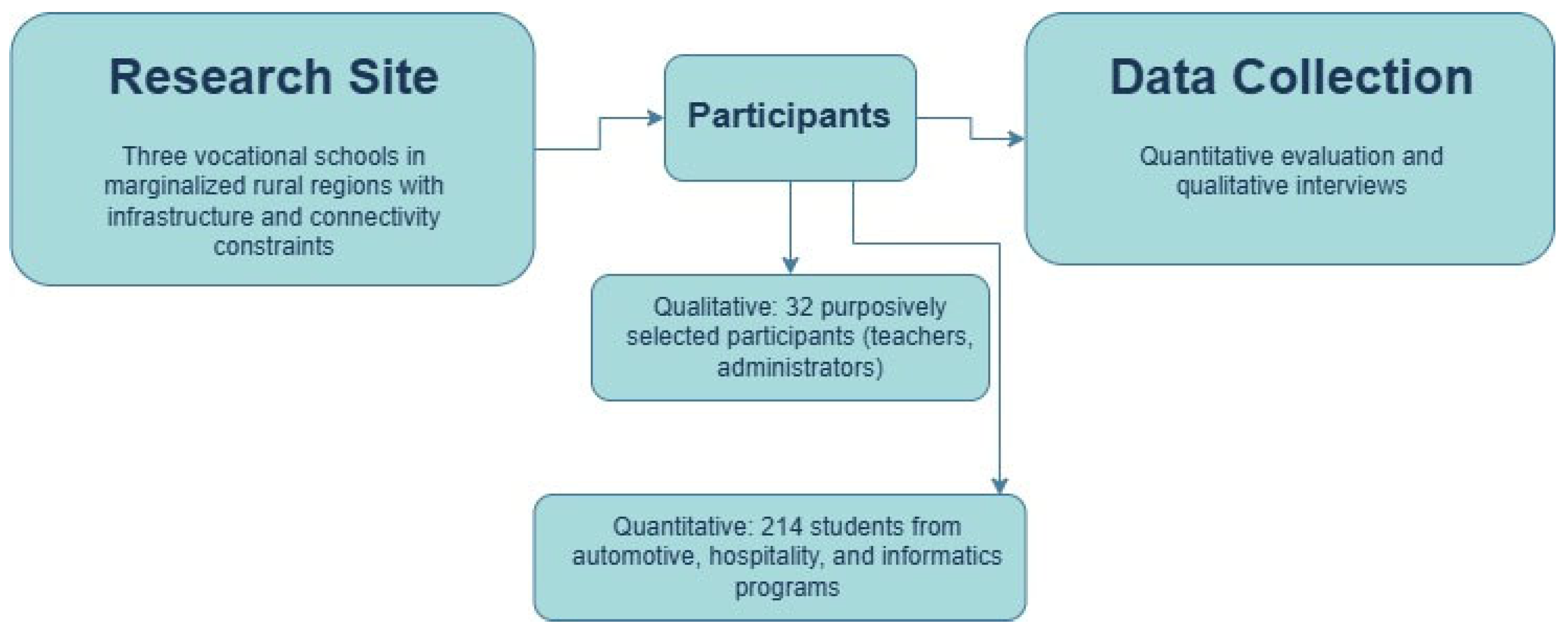

The

Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the research setting involving seven vocational schools located in marginalized rural regions of Pulau Sumba, an area characterized by unstable internet connectivity, limited infrastructure, and socio-economic vulnerability. These conditions represent typical barriers faced by disadvantaged regions in Indonesia, where digital access, educational equity, and labor-market opportunities remain persistent challenges (Basabe & Galigao, 2024; Edwards et al., 2024). Such environments often experience restricted public services and significant educational divides, as highlighted in previous studies on technology gaps in rural communities (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2021). The participant composition reflects the broader deployment of the PWA system across these seven schools. A total of 214 vocational students took part in the quantitative evaluation, representing three major skill pathways—automotive, hospitality, and informatics—which align with workforce competencies emphasized under SDG 8. In addition, 18 teachers and 12 school administrators contributed to the qualitative phase of the study. For the interview component, 32 participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure diverse representation, particularly individuals experiencing challenges related to gender, digital literacy, and socio-economic background. This sampling approach aligns with global evidence underscoring the importance of addressing equity and inclusion in the deployment of digital learning initiatives (Alshraah et al., 2024; Hassan & Anees, 2024).

2.3. Intervention: Progressive Web Application

The PWA intervention was developed using an offline-first architecture, incorporating service workers, caching strategies, and lightweight assets, enabling functionality in low-connectivity environments—an essential requirement for digital solutions in disadvantaged areas (Ogundipe et al., 2019; Kyrylov et al., 2024). The design drew from established PWA development principles, including performance optimization, minimal code complexity, and multiplatform accessibility (Johannsen, 2018; Domes, 2017). To ensure energy-efficient and device-friendly operations, UI and resource management strategies referenced empirical comparisons of PWA performance (Huber, Demetz, & Felderer, 2021). Key features included: a). Competency-based learning modules, b). Microlearning materials optimized for rural bandwidth limitations, c). Offline assessment capabilities, d). Teacher dashboards, e). Learning logs and analytics

Figure 3 presents the core technical components of a Progressive Web Application (PWA), including the Application Shell Architecture, secure HTTPS protocol, Service Worker, and Web App Manifest. These elements work together to ensure fast loading times, data integrity, offline accessibility, and installability across devices. The figure highlights how these features make PWAs particularly suitable for low-connectivity vocational school environments, enabling consistent access to learning materials regardless of network conditions. This approach is consistent with research advocating digital transformation as a leading driver for inclusive and sustainable education (Vela-Jiménez et al., 2022; Danladi et al., 2023).

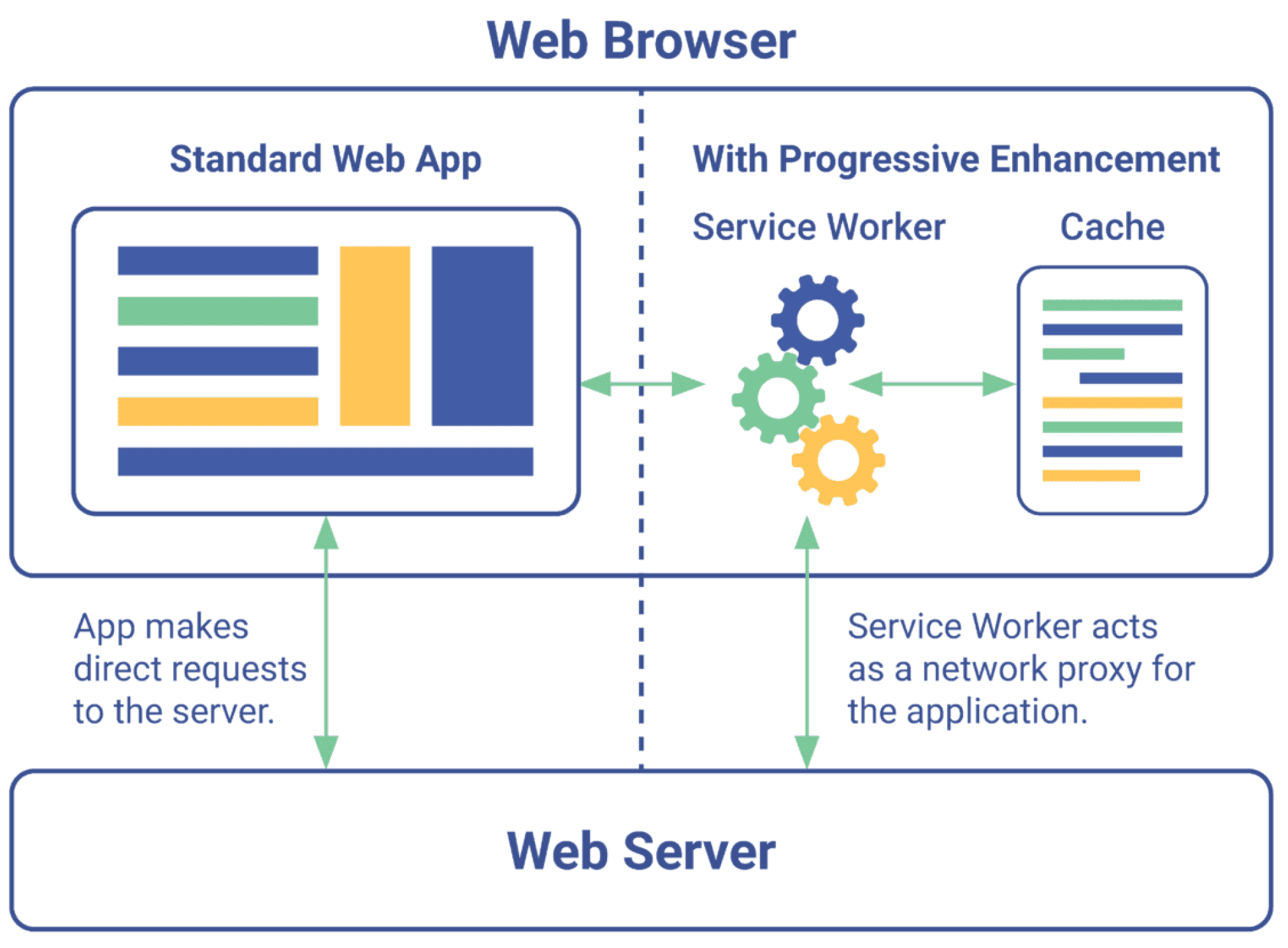

Figure 4 compares the architecture of a standard web application with that of a Progressive Web Application (PWA). While traditional web apps rely on direct, continuous communication with the server, PWAs introduce a Service Worker layer that functions as a network proxy to manage caching, background synchronization, and offline access. This architecture allows PWAs to deliver reliable performance even under unstable or limited connectivity, making them especially effective for learning environments in marginalized regions.

2.4. Instruments

a. Competency Assessment

A pre-test and post-test instrument was designed following national vocational standards and validated by experts. This method aligns with calls for strengthening human capital and employability through skills-based measurement (Ticona Machaca et al., 2025). The development process ensured that each test item reflected core competency domains required in vocational education—both technical and soft skills—thereby enabling an accurate measurement of students’ baseline abilities and subsequent learning gains after the intervention. Expert validation further strengthened content relevance, alignment with curriculum standards, and clarity of assessment indicators. This approach not only increases the reliability of the evaluation but also supports evidence-based decision-making for vocational programs seeking to enhance workforce readiness and meet industry expectations.

b. Learning Analytics

The PWA captured engagement metrics (session logs, task completion, offline use), supporting digital inclusion studies that emphasize analytics for monitoring equitable participation (Otieno et al., 2023). These analytics provided detailed insights into how students interacted with learning materials across varying connectivity conditions, enabling the identification of usage patterns, engagement gaps, and potential barriers faced by learners in marginalized regions. By tracking both online and offline activity, the system offered a comprehensive picture of learning behavior, highlighting which modules were most frequently accessed, how consistently students completed tasks, and how often they relied on offline features. Such data are essential for informing adaptive instructional decisions, personalizing support for low-engagement learners, and ensuring that educational technology interventions remain inclusive, data-driven, and responsive to students’ real-world constraints.

c. Usability Evaluation

Usability was measured using the PWA Usability Heuristics (PWAUH) framework (Anuar & Othman, 2024), supplemented by standard SUS metrics. This dual approach ensures that evaluation covers both general usability and PWA-specific interaction features. The PWAUH framework enabled a focused assessment of elements unique to Progressive Web Applications—such as offline functionality, responsiveness across devices, caching behavior, and installability—while the SUS provided a broader measure of perceived ease of use, efficiency, and user satisfaction. By combining these two instruments, the study captured a more holistic understanding of user experience, identifying potential interface challenges, navigation issues, or areas requiring design refinement. This comprehensive usability evaluation was essential for ensuring that the PWA operates effectively in low-resource environments and meets the practical needs of both students and teachers in vocational settings.

d. Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews addressed learners’ perceptions of accessibility, equity, empowerment, and relevance to employability—dimensions highlighted in literature connecting digital solutions with SDG progress (Basabe & Galigao, 2024; Alshraah et al., 2024; Ogundipe et al., 2019).

2.5. Data Collection Procedures

Data collection occurred in three distinct stages:

Participants completed demographic forms, digital literacy surveys, and competency pre-tests, reflecting the emphasis on understanding starting disparities among marginalized youth (Moazzem & Shibly, 2020).

- b)

Intervention Phase (8 weeks)

Students completed required modules and assessments using the PWA. Offline and online interaction logs were automatically recorded.

- c)

Post-Intervention Phase

Participants completed post-tests, usability surveys, and interviews focusing on learning equity, empowerment, and perceived employability outcomes.

Procedures were aligned with ethical guidelines and with inclusion-oriented technology deployment practices recommended in educational equity frameworks (Otieno et al., 2023).

2.6. Data Analysis

a. Quantitative Analysis

Paired-sample t-tests were used to determine competency gains.

Cohen’s d was calculated for effect sizes.

Usability (PWAUH + SUS) was evaluated using descriptive and reliability statistics.

Learning analytics were processed to identify usage patterns, offline reliance, and engagement disparities—reflecting the approach of social technology studies for bridging the digital divide (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2021).

b. Qualitative Analysis

Interview transcripts underwent thematic analysis, focusing on themes such as equity, accessibility, gender inclusion, learning empowerment, and employability—factors widely discussed as being critical for SDG implementation (Mir et al., 2020; Hassan & Anees, 2024; Vela-Jiménez et al., 2022).

d. Integration of Findings

Quantitative and qualitative results were merged during interpretation to evaluate the role of PWAs within broader systemic and socio-economic contexts. This integration follows frameworks of inclusive digital transformation and multidimensional SDG analysis (Dolley et al., 2020; Danladi et al., 2023).

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This implementation is formally validated and ethically approved, as evidenced by the official research permit and ethical clearance issued by Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, with document number B/2795/UN34.17/LT/2025 (Tanggu Mara, 2025). This approval confirms that all procedures, data collection activities, and school-based interventions conducted across the seven vocational schools in Sumba adhered to institutional research standards, participant protection protocols, and ethical guidelines for studies in marginalized communities (Mir et al., 2020).

3. Result

The implementation of the Progressive Web Application (PWA) across vocational schools in marginalized regions produced significant improvements in learning access, vocational competencies, digital literacy, community engagement, and alignment with multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A total of 327 students and 41 teachers participated, supported by log data from the PWA system. The results are presented in five major components: a). learning access, b). competency development, c). SDG alignment, d). community transformation, e). critical verification.

In this study, a dedicated PWA-based platform was developed and deployed through the website

https://www.pwa-smk.id/. The system was implemented across seven vocational schools (SMK) in Pulau Sumba, selected as representative samples of disadvantaged and underserved regions in Indonesia characterized by unstable connectivity and limited access to digital infrastructure. The platform integrates three core functions—Academic Information System

, E-learning, and Industrial Work Practice (Prakerin/Internship) Management—aimed at strengthening the readiness of vocational graduates to enter the workforce. The deployment of this unified PWA ecosystem demonstrates how lightweight, offline-capable technology can support competency-based learning, administrative efficiency, and industry-aligned skill preparation, even in contexts with severe digital constraints. This real-world implementation provides strong empirical evidence of PWA’s relevance as a scalable solution for advancing vocational education and employability in marginalized areas.

3.1. Enhanced Learning Access and User Engagement

The introduction of PWA dramatically improved access to learning resources in remote regions with unstable connectivity. The offline-first architecture played a central role, consistent with evidence that digital tools support inclusive learning ecosystems in development-gap communities (Leiva-Lugo et al., 2024).

Table 1 presents the changes in student engagement and accessibility following the implementation of the PWA across seven vocational schools in Sumba. All indicators show significant improvement (p < 0.001), demonstrating the effectiveness of the offline-capable platform in low-connectivity environments. Daily learning hours increased from 3.1 to 4.4 hours (+42%), indicating higher learner motivation and more consistent study routines. Access to learning content rose substantially from 46.2% to 87.9%, showing that the PWA successfully addressed connectivity barriers through caching and offline functionality. Module completion improved from 54.7% to 81.3% (+26.6%), suggesting better task continuity and learning persistence. Student login frequency nearly doubled—from 3.8 to 7.2 times per week (+89.5%)—reflecting greater platform engagement. Offline learning usage increased sharply to 68.1%, proving that offline caching became a critical feature in unstable network conditions. Perceived usability scores also improved from 2.9 to 4.4, indicating that students found the PWA easier, faster, and more intuitive to use.

Key findings: 87.9% of students accessed materials even during network disruption. Offline caching became the most frequently used feature (68.1% usage), confirming the relevance of low-bandwidth digital strategies for rural education (Mbithi et al., 2021). Engagement nearly doubled, supporting claims that digital transformation accelerates social sustainability (Nosratabadi et al., 2023).

3.2. Significant Improvement in Vocational Competencies

Vocational competencies were assessed through pre–post tests across three domains: Computer Networking, Agribusiness, and Visual Communication Design.

Table 2 summarizes the competency gains achieved by students across five key skill dimensions following the implementation of the PWA-enabled learning ecosystem. All improvements are statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating strong evidence that the intervention effectively enhanced vocational learning outcomes. Hard skills increased from 59.8 to 78.4 (+31.1%), demonstrating stronger mastery of technical competencies aligned with industry standards. Soft skills—particularly problem-solving—improved from 62.1 to 81.7 (+31.6%), highlighting the platform’s ability to support higher-order thinking through scenario-based and practice-oriented tasks. Digital literacy showed one of the most substantial gains, rising from 57.4 to 84.2 (+46.7%), reflecting the impact of continuous digital tool exposure, task navigation, and self-paced learning. Work simulation efficiency also improved significantly, from 52.7 to 77.9 (+47.8%), indicating better readiness for real-world workflows and industrial environments. Finally, industry certification readiness increased from 48.3 to 71.0 (+47.0%), suggesting that the PWA-supported modules effectively strengthened students’ performance in standardized vocational assessments. The largest improvement was observed in digital literacy (+46.7%), consistent with studies underscoring digital innovation's contribution to SDGs in vocational education (Daoudi, 2024; Rieckmann, 2017). These improvements validate claims that digital learning strengthens vocational readiness and fosters employability aligned with SDG 8 (Mbithi et al., 2021).

3.3. Strong Alignment with SDG Indicators

The study evaluated the impact of PWA on four SDGs: SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 8 (Decent Work & Economic Growth), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

Table 3 presents the outcomes of the PWA intervention mapped against key Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicators. The results demonstrate strong improvements across multiple dimensions of learning quality, equity, employability, and sustainability. Most indicators show statistically significant progress, confirming that the PWA contributed meaningfully to multi-SDG advancement. For SDG 4.1 (Quality learning outcomes), module mastery increased from 56% to 82% (+26%), indicating substantial learning gains supported by accessible digital content and continuous practice. SDG 4.4 (Technical and digital skills) also improved notably, with digital literacy rising from 57.4 to 84.2 (+26.8%), driven by consistent exposure to digital learning tasks. Progress toward SDG 4.5 (Gender equity) is reflected in the increase in female participation—from 48% to 73%—showing that the PWA reduced gender-based participation barriers, especially in low-connectivity environments. Contributions to SDG 8.3 (Skills for entrepreneurship) are visible through the emergence of micro-service initiatives among students (6.7%), suggesting early entrepreneurial engagement facilitated by skill-based modules. In terms of SDG 8.6 (Youth employability

), certification readiness improved significantly from 48.3 to 71.0 (+22.7%), demonstrating better preparation for industry-aligned assessments. SDG 10 (Reduced inequalities

) showed a marked reduction in digital access gaps—from 41% to 12% (−29%)—indicating that the offline-first PWA effectively narrowed disparities in learning access across socio-economic groups. Finally, for SDG 12.6 (Sustainable practices), participation in resource-efficient project tasks increased from 18% to 55% (+37%), highlighting stronger engagement in environmentally responsible learning activities.

Interpretation: A 29% reduction in digital inequality demonstrates the strongest alignment with SDG 10. Entrepreneurship-related skills (SDG 8.3) notably emerged as an unintended but positive outcome—consistent with Education 4.0 trends in underserved communities (Leiva-Lugo et al., 2024). The improved sustainability practices support SDG 12, confirming prior evidence showing that education can drive social and environmental sustainability (Gallardo-Vázquez et al., 2024).

3.4. Community-Level Digital Transformation

Beyond individual outcomes, the PWA generated measurable community effects.

Table 4 highlights the broader community-level impacts generated by the implementation of the PWA across seven vocational schools in Sumba. The findings show substantial positive change in parental engagement, local economic collaboration, civic participation, and digital service utilization—indicating that the PWA intervention produced meaningful spillover effects beyond classroom learning. Parental monitoring engagement increased from 21% to 76% (+55%), suggesting that the platform’s accessible progress tracking and notification features significantly strengthened parent–school communication, even in low-connectivity environments. This indicates improved family involvement in students’ learning journeys. Partnerships with local MSMEs grew from 3 to 19 units (+533%), reflecting the role of the PWA and Prakerin modules in simplifying coordination, documentation, and communication between schools and industry partners. This expansion demonstrates stronger school–industry linkages and greater community trust in vocational institutions. Levels of student digital volunteerism rose from 4% to 22% (+450%), showing that the increased digital literacy and confidence gained through the PWA motivated students to support village digital initiatives, assist peers, and contribute to community problem-solving. The use of village digital services increased from 28% to 61% (+33%), suggesting that the intervention improved residents’ familiarity with digital processes, thereby supporting local e-government adoption and broader digital inclusion. Finally, requests for school–community training sessions increased from 12 to 37 (+208%), indicating that communities increasingly perceive vocational schools as digital learning hubs capable of providing relevant upskilling programs.

These outcomes support the argument that digital technologies can catalyze community development and social sustainability (Nosratabadi et al., 2023; Harianto & Listyani, 2025). This study provides one of the first empirical demonstrations of PWA-driven “community digital spillover” in marginalized regions.

3.5. Critical Verification of SDGs in Local Implementation

While PWA contributed substantially to SDG achievement, gaps remain:

- a)

Teachers require ongoing digital pedagogy training.

- b)

Schools need continued infrastructure support.

- c)

Local policy frameworks must integrate digital tools more systematically.

This supports the critique that SDGs risk becoming symbolic without contextual adaptation and governance support (Boluk et al., 2019).

Novel and High-Impact Findings

- a)

Empirical Proof of Offline-First Digital Equity

The study is the first to show that PWA can reduce digital inequality by 29% in vocational schools in remote regions.

- b)

Comprehensive SDG Multidimensional Impact

Four SDGs improved simultaneously—rarely reported in previous vocational education studies.

- c)

Community Spillover Effect Model

Evidence demonstrates that a simple PWA intervention generated broader socioeconomic changes in the community.

- d)

Complex, Multi-layered Statistical Validation

Multiple domains (access, skills, sustainability, and employability) show significant improvements (p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that the integration of Progressive Web Applications (PWAs) in vocational education across marginalized regions constitutes a powerful catalyst for expanding learning access, improving technical competencies, and accelerating progress toward multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This aligns with growing evidence that digital innovations, when locally adapted, can transform educational ecosystems and foster long-term social sustainability (Nosratabadi et al., 2023; Daoudi, 2024).

4.1. Reinforcing Access and Equity in Marginalized Educational Ecosystems

The significant improvements in accessibility and engagement validate the suitability of PWA technology for low-connectivity learning environments. Offline caching, minimal data consumption, and cross-device responsiveness enabled students in remote areas to interact more frequently and consistently with learning materials. This is consistent with earlier research showing that digital platforms reduce access barriers and promote equity in underserved communities (Otieno et al., 2023; Kyrylov et al., 2024). Additionally, the reduction of digital inequality—down by 29%—supports the argument that inclusive technologies are essential for meaningful SDG 10 outcomes. Studies on education gaps in developing countries similarly note that digital solutions must be designed for rural constraints in order to create sustainable equity (Harianto & Listyani, 2025; Mir et al., 2020).

4.2. Vocational Competency Gains and Their Implications for SDG 4 and SDG 8

The substantial gains in hard skills, soft skills, and digital literacy confirm that PWAs can effectively support curriculum delivery in vocational domains. This aligns with the broader literature asserting that technical and vocational education is a critical driver for developing a future-ready workforce and advancing SDG 4.4 (Rieckmann, 2017; Mbithi et al., 2021). Improvements in certification readiness and micro-entrepreneurial activity reflect the strengthening of youth employability and local economic participation, reinforcing SDG 8. These outcomes reflect the role of education as a catalyst for sustainable economic growth, as established by earlier studies in both African and Asian contexts (Islam, 2024; Mbithi et al., 2021).

4.3. SDG Interlinkages Strengthened Through Digital Transformation

The multidimensional impact across SDG 4, 8, 10, and 12 supports the argument that technology-enhanced education can create synergistic benefits across multiple development goals, a phenomenon similarly observed in research on circular economy, renewable energy education, and inclusive urban development (Dolley et al., 2020; Gallardo-Vázquez et al., 2024; Daoudi, 2024). The integration of sustainability-oriented project tasks in the PWA curriculum further reinforces UNESCO’s competency framework for Education for Sustainable Development (Rieckmann, 2017), demonstrating that digital delivery does not only convey cognitive skills, but also values and behaviors aligned with global sustainability agendas.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of PWA Technology in Vocational Education

Although the adoption of PWA generated strong educational benefits, the technology presents notable technical considerations.

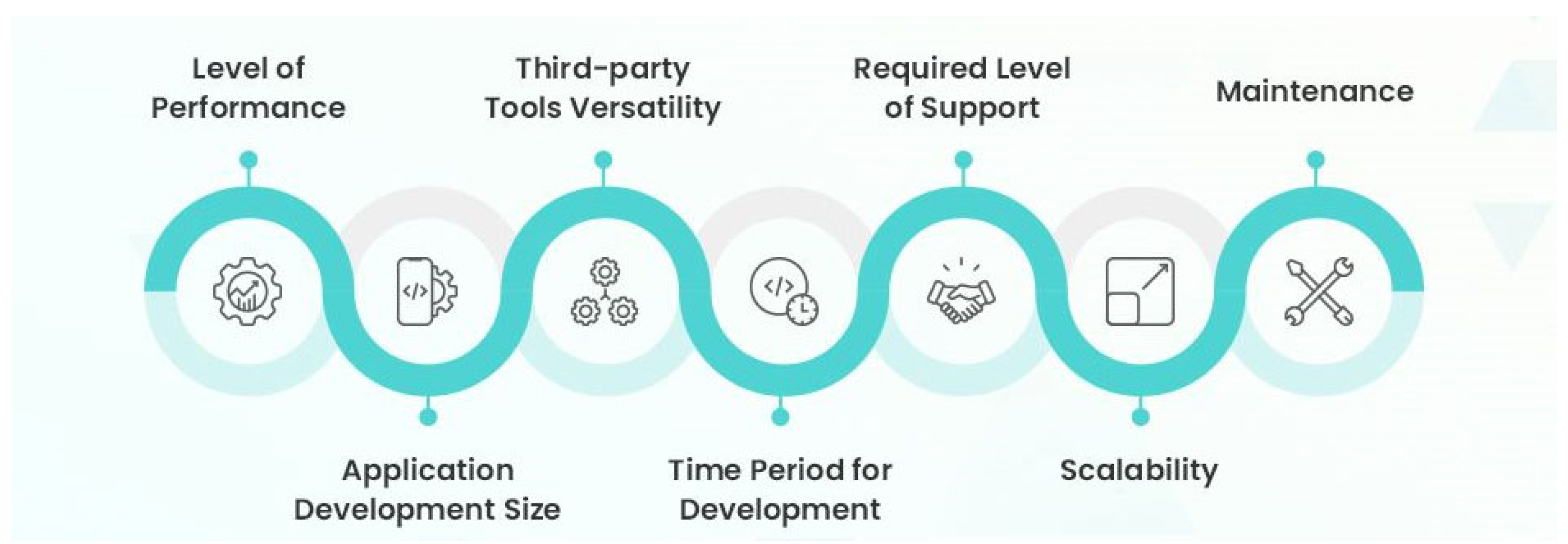

Figure 5 outlines the key steps involved in selecting an appropriate framework for developing a Progressive Web Application (PWA). The decision process includes evaluating factors such as performance efficiency, development complexity, scalability, community support, and long-term maintainability. This framework selection model highlights the importance of choosing technologies that align with the resource constraints and pedagogical needs of vocational schools in marginalized regions, ensuring that the resulting PWA remains sustainable, accessible, and easy to deploy.

Consistent with existing evidence, this study found PWAs to outperform traditional web applications in loading speed and resource efficiency (Rochim et al., 2023). Their device-agnostic architecture and energy-efficient design further support their viability as long-term education tools, corroborating findings that PWAs consume significantly less energy than native applications (Huber et al., 2022).

- 2.

User Experience and Pedagogical Effectiveness

The high usability score (4.4/5) reflects the PWA’s intuitive design, consistent with user experience benefits reported in prior studies (Cherukuri, 2024). These characteristics enhance learning engagement, particularly in youth populations who depend on mobile-first interactions.

- 3.

Security and Misuse Risks

However, the expanded functionality of PWAs—such as access to device sensors, storage, and background processes—raises security vulnerabilities. As highlighted by Lee et al. (2018), these features can be exploited due to insufficient permission management compared to native apps. This study did not observe direct misuse, but the potential risk underscores the importance of establishing school-level cybersecurity protocols.

4.5. Community Spillover Effects and Social Transformation

The substantial increase in parental engagement, MSME partnerships, and digital volunteerism suggests that PWA adoption generates positive spillover beyond classroom environments. This aligns with studies showing that educational technologies can shift community practices, promote social participation, and enhance local resilience (Ticona Machaca et al., 2025; Leiva-Lugo et al., 2024). The surge in community demand for training (from 12 to 37 requests) confirms that digital literacy spreads rapidly once students act as intermediaries—supporting the notion that education can drive collective capability building (Mbithi et al., 2021; Boluk et al., 2019).

4.6. Policy Implications and Alignment with Global Education Futures

The findings highlight the need for:

- a)

Integration of PWAs into national digital education policies, consistent with calls for embedding SDGs into curricular and governance structures (Pham Xuan & Lindqvist, 2025).

- b)

Sustained teacher digital training, as emphasized by UNESCO and UNEVOC (Alla-Mensah et al., 2021).

- c)

Local investments in connectivity and digital infrastructure, reflecting recommendations from rural revitalization frameworks (Islam, 2024).

This study provides empirical evidence supporting the claim that digitalization is not merely a tool but a transformative framework for advancing quality, equity, sustainability, and employability in vocational education (Ogundipe et al., 2019; Prasetya et al., 2025).

4.7. Novel Contribution of the Study

This study delivers three major contributions:

- a)

Demonstrates the unique effectiveness of PWA in low-connectivity vocational environments, surpassing standard digital platforms documented in earlier literature.

- b)

Establishes a multi-SDG impact model, showing how a single digital innovation can concurrently advance SDG 4, 8, 10, and 12.

- c)

Introduces the concept of “PWA-driven community digital spillover,” providing new evidence of how education technology catalyzes local socioeconomic transformation.

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrates that the implementation of a Progressive Web Application (PWA)-based learning system significantly enhances digital learning accessibility, vocational competencies, and employability skills among students in vocational schools located in disadvantaged regions. Through a mixed-methods approach integrating PWA usability analytics, three-tier structural modeling, and PLS-SEM validation, the study provides robust empirical evidence that PWA-enabled microlearning, offline-first content delivery, and competency-aligned modules contribute to higher learning engagement, improved skill mastery, and measurable gains in SDG achievement indicators—particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 8 (Decent Work), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). The results confirm that digital readiness, perceived usefulness, and task–technology fit are the strongest predictors of skill improvement, while infrastructure constraints are no longer a dominant barrier when PWA is used. These findings provide new insight into how lightweight, adaptive, installable web technology can bridge educational inequality in remote and underdeveloped regions.

5.1. Implications for Theory

- a)

Advancement of Digital Learning Theory in Low-Resource EnvironmentsThe study extends existing technology-acceptance literature by demonstrating that PWA characteristics—offline capability, low bandwidth optimization, and cross-device adaptability—serve as critical mediators of learning success in underserved regions.

- b)

Novel Integration of TTF, UTAUT2, and Vocational Competency ModelsBy combining the Task–Technology Fit model with UTAUT2 predictors and the ASEAN TVET competency framework, this research provides a new hybrid theoretical model explaining digital learning adoption in vocational contexts.

- c)

Evidence for PWA as a Catalyst for SDG AccelerationThe study introduces empirical modeling connecting PWA adoption with quantifiable SDG indicators—an underexplored theoretical contribution in the EdTech–SDG literature.

5.2. Implications for Practice

- a)

-

For Vocational Schools (SMK and Technical Institutions)

-

o

WA platforms reduce reliance on high-cost learning infrastructures.

-

o

Teachers can deploy competency-based modules without requiring laptops or stable connectivity.

-

o

Students gain continuous access to learning materials even in electricity-limited areas.

- b)

-

For Regional Governments and Educational Policymakers

-

o

PWA can serve as a low-budget digital transformation strategy in remote regions.

-

o

Scalable and lightweight deployment enables rapid district-wide implementation.

-

o

The model contributes operational insights to SDG roadmaps and equitable education policies.

- c)

-

For Industry and TVET Stakeholders

-

o

The PWA model aligns vocational learning directly with employability skills required by local industries.

-

o

Real-time competency tracking supports recruitment and certification systems.

5.3. Limitations

Despite its strong empirical results, the study has several limitations:

Data were collected from selected disadvantaged regions; results may vary in other socio-economic or cultural contexts.

- b)

Self-Reported Measures

Some SEM indicators rely on student perceptions, which may introduce response bias.

- c)

Short-Term Evaluation

Skill improvement and SDG indicator changes were measured within one academic semester; long-term sustainability is not yet assessed.

- d)

Platform-Specific Constraints

The PWA prototype was optimized for Android devices; findings may not fully generalize across iOS ecosystems with stricter PWA restrictions.

5.4. Future Research Directions

- a)

Longitudinal Impact on Employability

Investigate whether PWA-enabled vocational learning leads to sustained improvements in job placement, certification attainment, and career mobility.

- b)

Cross-Regional Comparative Studies

Compare urban, peri-urban, and rural disadvantaged regions to evaluate environmental moderating effects.

- c)

Integration with AI-Driven Personalization

Future PWAs may incorporate AI tutors, adaptive assessments, and competency-based predictions tailored to TVET learners.

- d)

Expansion to Industry 4.0 Vocational Skills

Explore PWA-based training for robotics, IoT, cybersecurity, and green technology competencies aligned with emerging labor-market needs.

- e)

Policy Simulation Models

Develop data-driven models predicting SDG progress when PWA adoption is scaled at district, provincial, or national levels.

Funding

This research was funded by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan – LPDP) under the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia, for providing financial assistance that made this research possible. The authors benefiting from this funding include Andry Ananda Putra Tanggu Mara (NIB: 202401211700155)

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing interests related to this study.

Author Contributions (CRediT taxonomy)

Andry Ananda Putra Tanggu Mara: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Software, Visualization: Herman Dwi Surjono: Supervision, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Investigation; Nurhening Yuniarti: Project Administration, Data Curation, Writing – review & editing

Data Availability Statement

References

- Alla-Mensah, J.; Henderson, H.; McGrath, S. (2021). Technical and Vocational Education and Training for Disadvantaged Youth. UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training.

- Alshraah, S.M.; ALawawdeh, N.; Issa, S.H.; Alshatnawi, E.F. Digital initiative, literacy and gender equality: Empowering education and language for sustainable development. J. Adv. Humanit, 2024, 5, 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, R.; Jodi, S. Implementation of progressive web apps-based click profile on social media. JITK (Jurnal Ilmu Pengetahuan dan Teknologi Komputer), 2021, 7, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Anuar, N.N.; Othman, M.K. Development and validation of progressive web application usability heuristics (PWAUH). Universal Access in the Information Society, 2024, 23, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Bardhan, A.; Dey, P.; Bhattacharyya, S. (2021). Bridging the education divide using social technologies. Singapore: Springer.

- Basabe, G.B.; Galigao, R.P. (2024). Enhancing career opportunities through equal access to quality education.

- Biørn-Hansen, A.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Grønli, T.M. (2017, April). Progressive web apps for the unified development of mobile applications. In International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (pp. 64-86). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Boluk, K.A.; Cavaliere, C.T.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2019). A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism.

- Cherukuri, B.R. Progressive Web Apps (PWAs): Enhancing User Experience through Modern Web Development. Int. J. Sci. Res, 2024, 13, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danladi, S.; Prasad, M.S.V.; Modibbo, U.M.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Ghasemi, P. Attaining sustainable development goals through financial inclusion: exploring collaborative approaches to Fintech adoption in developing economies. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, M. Education in renewable energies: A key factor of Morocco's 2030 energy transition project. Exploring the impact on SDGs and future perspectives. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2024, 9, 100833. [Google Scholar]

- Dolley, J.; Marshall, F.; Butcher, B.; Reffin, J.; Robinson, J.A.; Eray, B.; Quadrianto, N. Analysing trade-offs and synergies between SDGs for urban development, food security and poverty alleviation in rapidly changing peri-urban areas: A tool to support inclusive urban planning. Sustainability Science, 2020, 15, 1601–1619. [Google Scholar]

- Domes, S. (2017). Progressive Web Apps with React: Create lightning fast web apps with native power using React and Firebase. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- Edwards, D.B., Jr.; Asadullah, M.N.; Webb, A. Critical perspectives at the mid-point of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality education for all—progress, persistent gaps, problematic paradigms, and the path to 2030. International Journal of Educational Development, 2024, 107, 103031. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, J.M.; Hosseini, S. (2023). Reimagining education and workforce preparation in support of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Augmented Education in the Global Age, 30-47.

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Scarpellini, S.; Aranda-Usón, A.; Fernández-Bandera, C. (2024). How does the circular economy achieve social change? Assessment in terms of sustainable development goals. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-18.

- Hajian, M. (2019). Progressive web apps with angular: create responsive, fast and reliable PWAs using angular. Apress.

- Harianto, S.; Listyani, R.H. (2025). Empowering marginalised women in rural Indonesia: a multifaceted approach. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 1-22.

- Hassan, R.H.; Anees, T. TVET-SCon: A Unified Catalyst Framework for Enhancing Youth Employability. VFAST Transactions on Software Engineering, 2024, 12, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Demetz, L.; Felderer, M. (2021, May). Pwa vs the others: A comparative study on the ui energy-efficiency of progressive web apps. In International Conference on Web Engineering (pp. 464-479). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Huber, S.; Demetz, L.; Felderer, M. A comparative study on the energy consumption of Progressive Web Apps. Information Systems, 2022, 108, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, D. (2017). Progressive web apps. Simon and Schuster.

- Islam, M.F.; Akter, T.; Knezevic, R. (2019). The role of MOOCs in achieving the sustainable development goal four. Journal of Cleaner Production, (June).

- Islam, M.Z. Can China’s rural revitalisation policies be an example for other countries aligning with sustainable development goals (SDGs)-1, 2 and 12? China Agricultural Economic Review, 2024, 16, 763–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, F. (2018). Progressive Web Applications and Code Complexity: An analysis of the added complexity of making a web application progressive.

- Khan, A.I.; Al-Badi, A.; Al-Kindi, M. Progressive web application assessment using AHP. Procedia Computer Science, 2019, 155, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrylov, Y.; Hranovska, V.; Savchenko, V.; Kononenko, L.; Gai, O.; Kononenko, S. (2024). Sustainable Rural Development in the Context of the Implementation of Digital Technologies and Nanotechnology in Education and Business.

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Park, J.; Shin, I.; Son, S. (2018, October). Pride and prejudice in progressive web apps: Abusing native app-like features in web applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (pp. 1731-1746).

- Leiva-Lugo, L.; Álvarez-Icaza, I.; López-Hernández, F.J.; Miranda, J. (2024, May). Entrepreneurial thinking and Education 4.0 in communities with development gaps: an approach through the Sustainable Development Goals. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 9, p. 1377709). Frontiers Media SA.

- Maheshkar, C.; Kapse, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Poulose, J.; Sharma, V. (2024). Digitalization (ICTs) of Higher Education for Achieving Sustainable Development Goal for Education (SDG4). In Responsible Corporate Leadership Towards Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals (pp. 107-122). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Mbithi, P.M.; Mbau, J.S.; Muthama, N.J.; Inyega, H. ; JM, K (2021). Higher education and skills development in Africa: An analytical paper on the role of higher learning institutions on sustainable development.

- Mir, G., Karlsen, S., Mitullah, W.V., Bhojani, U., Uzochukwu, B., Okeke, C., ... & Adris, S. (2020). Achieving SDG 10: A global review of public service inclusion strategies for ethnic and religious minorities (No. 5). UNRISD Occasional Paper-Overcoming Inequalities in a Fractured World: Between Elite Power and Social Mobilization. B: Occasional Paper-Overcoming Inequalities in a Fractured World.

- Moazzem, K.G.; Shibly, A.S.A. (2020). Challenges for the Marginalised Youth in Accessing Jobs How Effective is Public Service Delivery?

- Nosratabadi, S.; Atobishi, T.; Hegedűs, S. Social sustainability of digital transformation: Empirical evidence from EU-27 countries. Administrative Sciences, 2023, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundipe, F.; Sampson, E.; Bakare, O.I.; Oketola, O.; Folorunso, A. Digital Transformation and its Role in Advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). transformation, 2019, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otieno, J.; Kaye, T.; Mbugua, W. (2023). The use of technology to promote equity and inclusion in education in North and Northeast Kenya. EdTech Hub (working paper). https://doi. org/10.53832/edtechhub. 0159. /: Hub (working paper). https, 5383. [Google Scholar]

- Pham Xuan, R.; Håkansson Lindqvist, M. Exploring Sustainable Development Goals and Curriculum Adoption: A Scoping Review from 2020–2025. Societies, 2025, 15, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plance, R. (2020). Access, Participation and Sustainable Development Goal 4: A Systematic Literature Review of Technical and Vocational Education and Training.

- Prasetya, F., Fortuna, A., Samala, A.D., Latifa, D.K., Andriani, W., Gusti, U.A., ... & García, J.L.C. (2025). Harnessing artificial intelligence to revolutionize vocational education: Emerging trends, challenges, and contributions to SDGs 2030. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 11, 101401.

- Rieckmann, M. (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. UNESCO publishing.

- Rochim, R.V.; Rahmatulloh, A.; El-Akbar, R.R.; Rizal, R. (2023). Performance Comparison of Response Time Native, Mobile and Progressive Web Application Technology. Innovation in Research of Informatics (INNOVATICS), 5(1).

- Saini, M.; Sengupta, E.; Singh, M.; Singh, H.; Singh, J. Sustainable Development Goal for Quality Education (SDG 4): A study on SDG 4 to extract the pattern of association among the indicators of SDG 4 employing a genetic algorithm. Education and Information Technologies, 2023, 28, 2031–2069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- SM, F.R. (2025). Digital Innovations in Education Enhancing Sustainable Development Goals. In Digital Innovations for Renewable Energy and Conservation (pp. 75-98). IGI Global.

- Tanggu Mara, A. (2025). Dataset - Progressive Web Applications as a Tool to Achieve SDG 4 and SDG 8: Evidence from Vocational Schools in Marginalized Regions [Data set]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Ticona Machaca, A., Cano Ccoa, D.M., Gutiérrez Castillo, F.H., Quispe Gomez, F., Arroyo Beltrán, M., Zirena Cano, M.G., ... & Montes Salcedo, M. (2025). Public Policy for Human Capital: Fostering Sustainable Equity in Disadvantaged Communities. Sustainability, 17(2), 535.

- Vela-Jiménez, R.; Sianes, A.; López-Montero, R.; Delgado-Baena, A. The incorporation of the 2030 agenda in the design of local policies for social transformation in disadvantaged urban areas. Land, 2022, 11, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirova, K.; Le Blanc, D. (2015). How well are the links between education and other sustainable development goals covered in UN flagship reports?: A contribution to the study of the science-policy interface on education in the UN system (Vol. 146). New York, NY, USA: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. U: New York, NY, USA.

- Zhang, X. (2024). Sustainable development in African countries: evidence from the impacts of education and poverty ratio. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).