1. Introduction

The Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) account for more than 95% of the business fabric in Ibero-America and are an essential pillar for job creation [

1,

2], innovation and social cohesion [

3,

4]. Their role transcends the economic sphere by contributing directly to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in terms of inclusive economic growth, poverty reduction and the promotion of innovation [

3,

5,

6]. However, despite their importance, MSMEs face persistent structural barriers, such as limited access to finance [

5,

7], insufficient digitalisation [

6,

8] and political instability. These conditions compromise their competitiveness and jeopardise their long-term sustainability.

Recent literature has advanced in the study of determinants such as sustainable innovation [

9], financial education [

10] and gender equality in business leadership [

11,

12], providing evidence of their influence on business competitiveness. However, most of this research adopts descriptive approaches or focuses on national cases, which limits the comparative understanding of the factors that influence the sustainable growth of MSMEs in broad regional contexts such as Ibero-America. Furthermore, the use of traditional methodologies, such as linear regressions or descriptive analyses, restricts the ability to model non-linear and complex relationships between organisational variables [

13,

14].

In this context, a research gap has been identified linked to the scarcity of empirical studies that integrate machine learning approaches to explain the sustainable growth of MSMEs in Ibero-America. Despite the abundance of business data available in the region, there has not yet been sufficient exploration of how techniques such as Random Forest can prioritise the factors that determine sustainability, providing both predictive rigour and interpretability to business management.

The aim of this study is to identify and rank the determining factors for the sustainable growth of MSMEs in Ibero-America by applying the Random Forest model to a database of 1,796 observations provided by FAEDPYME. The aim is to answer the research question: What factors most strongly explain the sustainability and competitive growth of MSMEs in Ibero-America?.

The article makes three main contributions. On a theoretical level, it broadens our understanding of sustainable growth in MSMEs from the perspective of dynamic capabilities, showing how organisational and contextual factors interact in a non-linear way. On an empirical level, it offers unprecedented regional evidence based on advanced predictive analysis techniques that overcome the limitations of traditional models. Finally, on a practical level, it formulates recommendations for the design of public policies and business strategies that strengthen human capital, innovation and the reduction of the digital divide as drivers of sustainability.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Sustainability in MSMEs

Corporate sustainability is understood as the ability of organisations to maintain balanced growth in the long term, simultaneously generating economic, social and environmental value [

15]. In the case of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), this concept transcends financial performance, as it implies resilience, adaptability and capacity for innovation in changing contexts [

16]. Due to their resource constraints, MSMEs face greater challenges in achieving sustainability, especially in emerging economies such as those in Ibero-America.

2.2. Key Concepts in Literature

Various studies have addressed the factors that affect the sustainability of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), highlighting the interaction between internal dimensions such as innovation, human capital and financial management, and external variables such as the political, institutional and technological context. The main approaches identified in recent literature are summarised below.

Innovation. Innovation is an essential pillar for the sustainability and competitiveness of MSMEs, enabling the creation of new products, services and processes that strengthen their economic performance and their commitment to long-term environmental responsibility [

9,

17]. In this context, entrepreneurs are increasingly open to dialogue and cooperation with their stakeholders, such as customers, employees and strategic partners, promoting co-creation spaces aimed at designing sustainable solutions that increase their adaptability and strengthen organisational competitiveness [

18,

19,

20]. Similarly, the development of innovation capacities has become a priority challenge, especially in relation to the acquisition of entrepreneurial and technological skills that foster sustainable innovation [

21,

22,

23].

Consequently, innovation not only drives organisational sustainability, but also promotes a positive impact on financial and environmental results, strengthening corporate reputation and generating new market niches [

9,

24].

Human Capital and Financial Education. Human capital is an essential component for business sustainability and organisational competitiveness [

25], as it improves their ability to adapt to the environment [

26]. In MSMEs, the lack of technical skills limits their development [

16], while higher qualifications and investment in human capital are linked to better business decisions [

27], greater innovation [

28], increased labour productivity [

29] and business economic growth [

30].

Likewise, financial education is becoming established as a key dimension of human capital, as it influences the strategic decision-making of MSMEs. A higher level of financial literacy improves financial performance [

31], investment decision-making [

32], risk management [

33,

34,

35] and business sustainability [

36]. In addition, the financial behaviour of entrepreneurs has a significant influence on organisational performance [

10].

However, financial education remains a structural weakness in the sector, limiting its ability to cope with changing environments [

37]. Hence the need to strengthen the technical and financial skills of human talent as a basis for sustainable and innovative management.

Access to financing. Access to financing is essential for the growth of MSMEs, as it strengthens their operational efficiency and competitive capacity [

38]. However, structural barriers persist, such as the lack of collateral and the demanding requirements of financial institutions, which hinder their inclusion in the formal financial system [

39,

40].

These limitations are exacerbated by poor financial literacy and low credit availability, which restricts innovation and hinders the execution of planned investments [

41,

42]. Despite the benefits of available financial products, their adoption remains limited among MSMEs [

43].

Given this scenario, sound financial management and strategic planning improve access to credit and efficiency in the use of resources [

44,

45]. In addition, self-financing and digital transformation have been shown to have a positive impact on financial performance by reducing dependence on external financing and optimising internal processes [

46].

MSMEs face obstacles in accessing formal financing. Alternatives such as fintech lending and crowdfunding are viable solutions, provided that adequate regulatory frameworks are in place.

Political Context and Security. Political stability and legal certainty are key conditions for creating environments conducive to private investment and business growth, especially in MSMEs, which tend to interpret stable political scenarios as a sign of confidence to invest, hire and expand their operations [

47,

48]. Conversely, political uncertainty creates an environment of risk aversion, inhibits innovation and reduces the competitiveness of the sector [

49,

50]. This climate of uncertainty particularly limits investment in research and development (R&D), mainly in companies without political ties, which face greater financial constraints and levels of risk [

51].

Furthermore, various forms of insecurity hinder commercial operations and discourage domestic and foreign investment, restricting business growth [

52]. In this context, companies that do not have comprehensive risk management systems are more vulnerable to these effects, compromising their sustainability [

53]. For its part, digital transformation is also affected by barriers linked to IT insecurity and a shortage of specialised talent, limiting technological modernisation processes and the ability to adapt to the digital environment [

54].

Digital Divide and Gender Perspective. The digital divide and gender perspective are interrelated dimensions that condition the competitive development of MSMEs, as reducing them is linked to greater business resilience, long-term sustainability and organisational well-being [

55]. In crisis contexts, a preference for female leadership has been observed due to more ethical and socially responsible approaches [

11,

12].

Furthermore, studies in Chile and Spain show that companies led by women achieve better financial performance and higher survival rates, demonstrating that gender and leadership styles have an impact on business results and reinforcing the need for public policies that promote equality in the business sphere [

56,

57].

On the other hand, in a digitalised environment, the use of ICT, the development of collaborative networks and marketing strategies such as SEO are becoming established as tools for improving the management, visibility and positioning of MSMEs; however, these opportunities require reducing the digital divide and ensuring inclusive access to technology [

58,

59].

2.3. Theoretical Basis

This study is based on the theory of dynamic capabilities [

60], which posits that competitive companies are those capable of integrating, building and reconfiguring internal and external resources in highly uncertain environments. In the case of MSMEs, sustainability is explained through three interrelated processes:

Identify: recognise opportunities and threats in the environment.

Leverage: mobilise resources to respond quickly to market changes.

Transform: reconfigure organisational structures and routines to sustain competitiveness over time.

The results of this research are interpreted within this theoretical framework, which allows us to understand how MSMEs combine internal factors (human capital, innovation, corporate governance) and external factors (financing, political context, digitalisation, gender) to drive their sustainable growth.

3. Materials and Methods

The study adopts a predictive, non-experimental quantitative approach based on supervised machine learning techniques such as the Random Forest (RF) algorithm, implemented in Python (version 3.11) using the scikit-learn package, recognised for its ability to handle large volumes of data and model complex relationships, reduce overfitting, the management of categorical and ordinal variables, and its ability to capture non-linear relationships and high-order interactions, and the interpretability of variable results according to their level of importance [

14,

61,

62,

63].

This type of model effectively handles heterogeneous variables, as the algorithm supports categorical and Likert-type ordinal variables without requiring strict transformations, facilitating the processing of multi-block business surveys [

14,

64,

65]. This model is particularly suitable in contexts with high dimensionality and possible non-linear relationships between predictor variables and the target variable, characteristics observed in the FAEDPYME 2024 database.

The RF's ability to estimate the relative importance of variables is also useful for identifying the factors that contribute most to the categorisation of business performance. It allows representative trees to be visualised and interpretable decision paths to be generated using plot_tree and export_graphviz, enabling a transparent explanation of the predictions [

66]. The model is aligned with previous studies that apply machine learning techniques in the analysis of micro and small businesses to predict success, growth, or risk [

67].

The structured survey from the FAEDPYME 2024 network was used, consisting of 18 blocks of questions aimed at evaluating factors related to corporate governance, human talent, environment, innovation, and business performance. The questionnaire includes different types of variables:

Categorical variables such as manager gender, family business, company size by employee range, type of economic sector, etc.

Likert-type ordinal variables rated on scales from 1 to 5 to measure perception of the environment, job skills, difficulty in hiring, level of innovation, importance of talent attraction strategies, among other aspects.

Continuous variables such as number of employees, percentage of international sales, percentage of women in management.

These variables were carefully pre-processed and coded in Python using pandas and sklearn, ensuring their correct transformation for supervised modelling. Meanwhile, Likert-type responses were treated as ordinal, preserving their structure for predictive analysis.

3.1. Details of the Empirical Model and Implementation

A pipeline was built for the pre-processing, training, and validation of the Random Forest model. The target variable corresponds to the perception of aggregate business performance (p12_5_mod), recoded into four ordinal classes (2, 3, 4, 5). This recoding was empirically justified to improve class distribution and facilitate classification, as classes 1 and 2 were underrepresented and were grouped together to avoid severe imbalance issues.

Two versions of the model were constructed in order to determine which one best complied with the principle of parsimony. The first version used the original base without major modifications to the data processing, while the second incorporated the SMOTE technique to oversample the less frequent classes and mitigate the bias towards the majority classes. The application of SMOTE is widely recognised in machine learning for datasets with class imbalance, as it generates synthetic instances of the minority class, improving the predictive capacity of the models [

68,

69].

To evaluate the model's performance without the risk of overfitting, a non-stratified split of the dataset was performed using Scikit-learn's train_test_split function, assigning 70% of the data to the training set and 30% to the test set. This ratio is recommended in the machine learning literature as an effective balance between robust training and sufficient external validation, allowing the model to learn general patterns without memorising the data, while reserving an adequate proportion to evaluate its generalisation ability [

70,

71].

In order to ensure the reproducibility of the results, the parameter random_state=42 was set. This practice ensures that, in future executions of the model, the training and test sets remain consistent, allowing valid comparisons between alternative configurations or models. The choice of the number 42 has become popular as a neutral standard value for random seed initialisation, although any fixed value could serve this purpose [

72].

3.2. Model Interpretability

The entire workflow was reproducible through the construction of supervised pipelines, which integrate cleaning, coding, modelling, and validation. Subsequently, the weight of each predictor variable in the prediction was calculated, highlighting the main factors associated with performance. As an interpretative decision rule, the most representative tree within the forest was identified by calculating Euclidean distances between the importance vectors of the individual trees and the complete set. and from this tree, explicit decision paths were visualised that allow us to see how certain combinations of variables lead to specific predictions, thus contributing interpretability to the model [

73].

3.3. Model Performance Evaluation

Table 1 presents key performance metrics of the Random Forest model following the application of SMOTE, and reports overall accuracy, macro and weighted F1-score, Chen's Kappa coefficient, and the confusion matrix. These metrics allow for a comprehensive and balanced evaluation of the model's performance in ordinal classifications and unbalanced situations [

66,

74].

4. Results

The empirical analysis was based on the implementation of the Random Forest algorithm, trained with class balancing using the SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) technique, with the aim of identifying patterns associated with the perceived level of growth in the sales of MSMEs in Ibero-America. This section presents the most representative results of the trained and validated model, including performance metrics, decision paths generated by the most representative tree, and their contextual interpretation, which allows the empirical findings to be linked to the thematic blocks of the conceptual framework.

It was decided to include only the results of the model with SMOTE, as it showed a significant improvement in predictive capacity compared to the model without class balancing, which is reflected in the accuracy metrics and the overall reliability of the classifier.

After applying the SMOTE synthetic oversampling technique to address class imbalance, RF achieved highly satisfactory performance, outperforming the model without SMOTE in terms of accuracy and class balance (

Table 1), reflecting robust and balanced predictive power, especially in classes of greater interest such as class 5 (rapid sales growth).

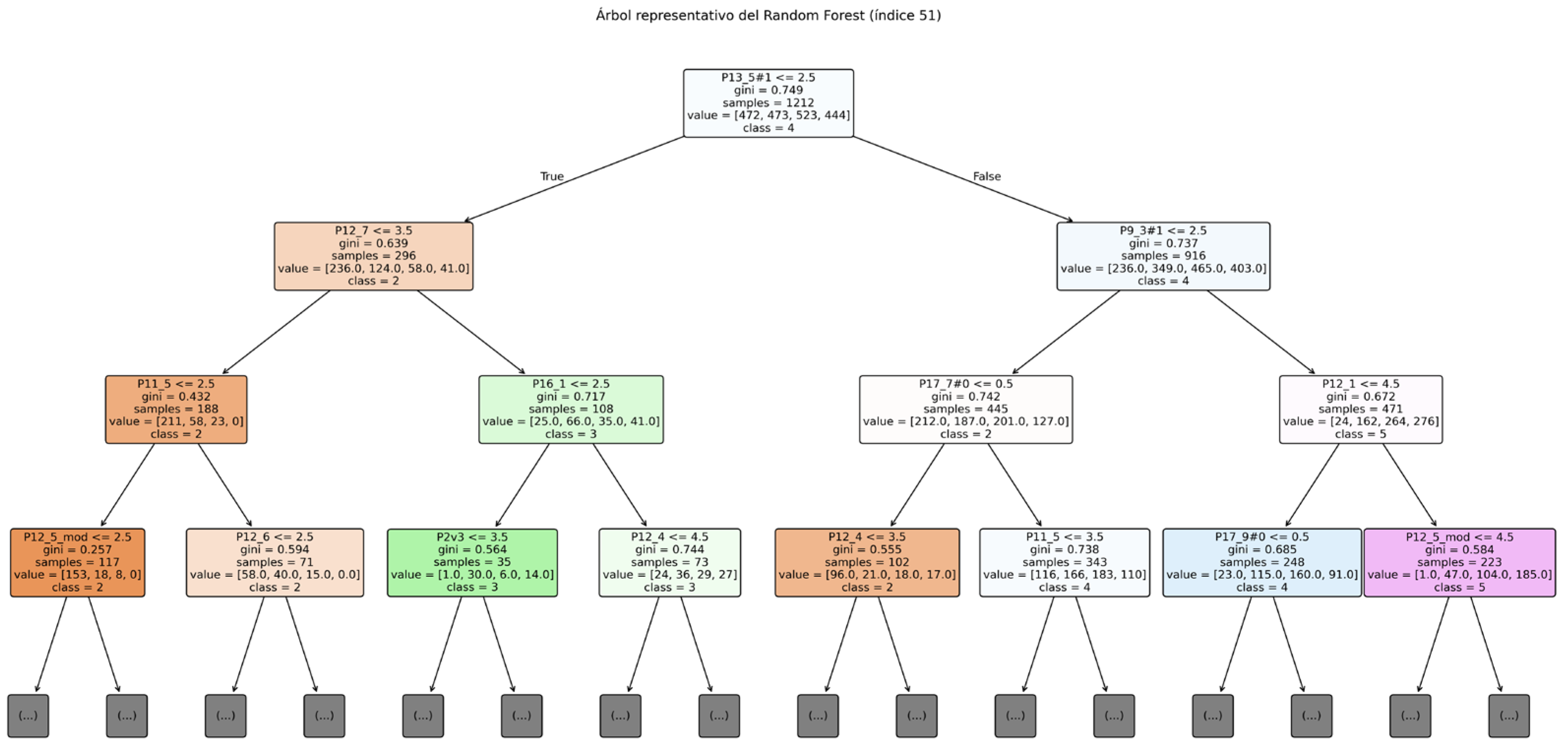

4.1. Representative Decision Tree

The model consists of 500 trees, but for interpretative purposes, tree number 51 (

Figure 1) was selected as representative (based on the lowest depth and prediction accuracy). The objective is the evolution of perceived sales growth (ordinal classes from 2 to 5), highlighting key nodes that lead to classifications in class 5.

Class 5 represents micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) that perceive high sales growth, which may be associated with greater competitive dynamism, operational efficiencies, or adaptability to the environment. Analysis of paths to this class within the representative tree of the RF model reveals patterns of combination of categorical and ordinal Likert-type variables that characterise these companies with high perceived performance.

4.1.1. Main Routes to Class 5

Table 2 presents the decision paths extracted from the most representative tree of the model, which allow the interpretation of the profiles of firms classified in the highest growth level (class 5). These paths reflect specific combinations of conditions in the key variables, grouped into thematic blocks such as innovation, environment, and governance.

4.1.2. Summary of Relevant Patterns

Table 3 summarises the common patterns observed in the paths leading to class 5 (highest sales growth), grouping the most influential variables by thematic block. These paths, derived from the representative tree of the model, enable the identification of key strategic blocks that characterise firms with superior relative performance.

The paths to growth (class 5) (

Table 3) do not respond to a single factor, but rather to synergistic combinations of staff satisfaction, trained leadership, innovation strategies, and organisational adaptability.

The specific contribution and content of each is detailed below (

Table 3):

Strategic innovation

The determining factors in this block are: innovation in products (P13_1#1) and equipment (P13_6#1) as key drivers of growth. In other words, companies that innovate in facilities, processes or capital goods, beyond the final product, tend to be better positioned, with innovation acting as a catalyst even when there are limitations in human talent or the digital environment.

Human talent and working environment

Variables such as job satisfaction (P12_7), difficulties in attracting talent (P15_9) and participation in external training (P15_10) show that human capital is a fundamental pillar. Companies with satisfied employees that invest in continuous training have a healthy working environment and achieve higher levels of growth, even if their processes are not yet highly innovative.

Corporate governance

In the corporate block, variables such as manager training in strategy (P16_1), age of the company (P2v3), and intention of family succession (P8_3) show that management decisions are key. Companies that have not yet considered generational transition, or that have academically trained leaders, are better able to capitalise on growth cycles, especially if they are relatively young and flexible.

Digital environment

To a lesser extent, the following also appear to be relevant: labour relations (P17_5#1), use of digital tools (P17_2#1), organisational agility (P12_4). Companies with cohesive working environments, even without a high level of digitalisation, manage to compensate for these weaknesses when they remain agile in the face of external changes or in their human relations.

5. Discussion

The findings obtained from the representative tree of the Random Forest model show that the sustainable growth of Ibero-American MSMEs does not depend on a single factor, but rather on a synergistic configuration of internal capabilities that interact in a non-linear manner. The hierarchical sequence identified—low process innovation, high job satisfaction, continuous training, and adaptable leadership—shows that the companies with the highest perceived growth are not necessarily the most digitised or those with formal strategic structures, but rather those that manage to mobilise their human capital as a compensatory driver of competitiveness. This result complements previous studies that highlight innovation as a determining factor in sustainable performance [

9,

24], by empirically demonstrating that job satisfaction and external training act as enabling preconditions for innovation to produce sustainable effects on performance.

Compared to the prevailing literature, which positions access to finance as the main structural obstacle for MSMEs in emerging economies [

5,

38], this factor did not emerge among the most hierarchically relevant predictors. This difference can be explained by two reasons: first, the FAEDPYME dataset includes surviving firms that have already overcome initial liquidity constraints, introducing a survival bias; and second, perceived sales growth responds more directly to internal transformation routines than to long-term structural financial conditions. In this sense, the results provide evidence that not all the structural factors described in the macroeconomic literature translate into predictive relevance at the micro-enterprise level, which invites us to differentiate between systemic constraints and activatable internal capacities.

From the theoretical framework of dynamic capabilities [

61], the results can be interpreted as empirical evidence of bundling processes. MSMEs that achieve higher levels of sustainability are those that reconfigure limited resources such as training, internal cohesion and incremental innovation to respond quickly to changes in the environment. The importance of job satisfaction in the upper nodes of the tree reinforces the notion that the social and behavioural dimensions of work are latent drivers of sustainability, particularly in contexts of resource scarcity. Thus, the empirical results support the hypothesis that companies can achieve sustainability through relational and human capital, even before reaching high levels of digitalisation or financial sophistication.

Taken together, the findings suggest a conceptual shift in understanding the sustainable growth of Ibero-American MSMEs: rather than depending on the availability of financial resources, it depends on the sequential activation of people-centred internal capacities. This positions human talent as a strategic lever for sustainability, rather than just an operational component. Consequently, public policies should prioritise the creation of training ecosystems, management mentoring programmes and the strengthening of the working environment, given that these strategies generate immediate sustainable returns and contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth) and SDG 9 (Industry, innovation and infrastructure).

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

A first limitation of the study relates to the cross-sectional nature of the FAEDPYME database. As the data covers a single time period, the patterns identified reflect static relationships between internal capabilities and perceived growth, without capturing evolutionary dynamics or lagged effects. Future research should incorporate longitudinal designs that allow for the analysis of causal trajectories and capacity maturation, especially in digitisation processes, where impacts tend to manifest themselves with time lags.

Secondly, the model is built on surviving companies, which introduces a selection bias towards firms that managed to withstand capital constraints, adverse environments or market failures. Consequently, the results cannot be automatically generalised to informal micro-enterprises or start-ups in pre-production phases. A natural next step is to replicate the model with samples stratified by type of enterprise, level of formalisation and economic sector, allowing us to validate whether the combinations of capabilities identified remain the same or whether different sustainability architectures emerge.

From a methodological point of view, although Random Forest offers predictive robustness and comparative interpretability superior to linear methods, future studies could contrast these results with additional explainable AI (XAI) techniques (e.g., SHAP values or LIME) and with deep non-linear architectures (e.g., Deep Neural Networks). This comparison would allow us to assess whether the routes identified here constitute stable patterns or whether alternative configurations could emerge under models capable of capturing higher-order interactions.

Finally, it is pertinent to incorporate institutional variables at the country level, such as regulatory frameworks, regional governance, political risks, and digital infrastructure, to estimate moderating effects of context and move towards multilevel models that simultaneously integrate internal capacities and structural constraints. This approach would increase the explanatory power of the model and link public policy formulation more directly to the organisational pathways that effectively lead to competitive sustainability.

7. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence on the factors that drive the sustainable growth of MSMEs in Ibero-America:

At the corporate governance level, we can see that the incorporation of new partners and external managers, in addition to the manager's university education, are determining factors for the competitive positioning of MSMEs, allowing them to be more robust and on track to achieve business sustainability [

75].

With regard to human talent, it is clear that the development of soft skills such as working in diverse teams, as well as job requirements and difficulties in filling positions in engineering and ICTs, and having skills in digitisation and communication technologies that better bridge the digital divide, are factors that significantly influence the achievement of sustainable growth [

76,

77].

Innovation, such as implementing changes and/or improvements within the company, and the perception of the environment, such as the available infrastructure and the country's economic situation, act as decisive factors when making a decision to make a short-, medium- or long-term investment.

These results show that a country's environment influences investment intentions, revealing the importance of generating public policies that respond to deep-rooted structural problems in the search for a robust system that fosters ideal environments for generating profitable and sustainable ventures over time [

78].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S.-E. and J.P.-P.; methodology, D.E.C.-T; L.S.-E. and J.P.-P; software, D.E.C.-T.; validation, D.E.C.-T. and L.S.-E.; formal analysis, D.E.C.-T. and L.S.-E.; investigation, L.S.-E.; J.P.-P. and D.E.C.-T.; resources, L.S.-E. and D.E.C.-T.; data curation, D.E.C.-T. and L.S.-E; writing—original draft preparation, L.S.-E.; J.P.-P. and D.E.C.-T.; writing—review and editing, L.S.-E. and J.P.-P.; visualization, D.E.C.-T; supervision, L.S.-E. and J.P.-P; project administration, L.S.-E. and J.P.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects who participated in the study were informed about the study and gave their express consent.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the support received from Universidad Técnica del Norte.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Prakash, P.; Verma, P.L.; Negi, V. MSMEs: Its Role in Inclusive Growth in India. IIFT Int. Bus. Manag. Rev. J. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Singh, S. Role of MSMEs in Social and Economic Development in India. Unpublished Work, 2020.

- Judijanto, L.; Hendra, J.; Islam, A. The Role of MSMEs in Realizing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). West Sci. Bus. Manag. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Indriani, A.; Sinaga, D.B.F.; Ingtyas, F.; Ginting, L. Meta-Analysis of the Role of Women in the Development of MSMEs. J. Corner Educ. Linguist. Lit. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Endris, E.; Kassegn, A. The Role of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) to the Sustainable Development of Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Challenges: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Ethiopia. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Rani, P. Role of MSMEs in Economic Development of India. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Stud. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K. A Study of Government Initiatives to Promote Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Sector in India. Manag. J. Adv. Res. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, K.; Sarvaiya, J. Role of MSMEs in India. Int. Res. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S. Eco-Innovation and SMEs’ Sustainable Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Culebro-Martínez, R.; Moreno-García, E.; Hernández-Mejía, S. Financial Literacy of Entrepreneurs and Companies’ Performance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 63. [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, M.C. Unlocking Sustainable Governance: The Role of Women at the Corporate Apex. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2024, 33, 746–762. [CrossRef]

- Chávez Díaz, J.M. Claves del Gobierno Corporativo y Sostenibilidad: Una Revisión de Literatura. Rev. Junta 2023, 6, 88–106. [CrossRef]

- Couronné, R.; Probst, P.; Boulesteix, A.-L. Random Forest versus Logistic Regression: A Large-Scale Benchmark Experiment. BMC Bioinform. 2018, 19, 270. [CrossRef]

- Probst, P.; Wright, M.; Boulesteix, A.-L. Hyperparameters and Tuning Strategies for Random Forest. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, e1301. [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation of SMEs: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, R.K. Managing Resilience of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) during COVID-19: Analysis of Barriers. Benchmarking. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Harsanto, B.; Mulyana, A.; Faisal, Y.A.; Shandy, V.M.; Alam, M. Sustainability Innovation in Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A Qualitative Analysis. Qual. Rep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Veronica, S.; Alexeis, G.-P.; Valentina, C.; Elisa, G. Do Stakeholder Capabilities Promote Sustainable Business Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises? Evidence from Italy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Scandurra, G.; Carfora, A. Adoption of Green Innovations by SMEs: An Investigation about the Influence of Stakeholders. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Phonthanukitithaworn, C.; Srisathan, W.; Ketkaew, C.; Naruetharadhol, P. Sustainable Development towards Openness SME Innovation: Taking Advantage of Intellectual Capital, Sustainable Initiatives, and Open Innovation. Sustainability 2023. [CrossRef]

- Heenkenda, H.; Xu, F.; Kulathunga, K.; Senevirathne, W. The Role of Innovation Capability in Enhancing Sustainability in SMEs: An Emerging Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2022. [CrossRef]

- Koliby, I.S.M.A.; Abdullah, H.H.; Suki, M. Linking Entrepreneurial Competencies, Innovation and Sustainable Performance of Manufacturing SMEs. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, R.; Jayasundara, J.; Gamage, S.K.N.; Ekanayake, E.; Rajapakshe, P.; Abeyrathne, G. Sustainability of SMEs in the Competition: A Systemic Review on Technological Challenges and SME Performance. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Ikram, M. Do Sustainability Innovation and Firm Competitiveness Help Improve Firm Performance? Evidence from the SME Sector in Vietnam. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Borazon, E.; Liu, J.-M.; Okumus, F. Human Capital, Growth, and Competitiveness of Philippine MSMEs: The Mediating Role of Social Capital. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2022, 30, 894–923. [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, D.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Popadiuk, S.; Mainardes, E. The Relationship between Human Capital, Information Technology Capability, Innovativeness and Organizational Performance: An Integrated Approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Lei, X.; Hu, F. The Influence of Top Management Team Human Capital on Sustainable Business Growth. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kusumawijaya, I.K.; Astuti, P.D. The Effect of Human Capital on Innovation: The Mediation Role of Knowledge Creation and Knowledge Sharing in Small Companies. Knowl. Perform. Manag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, J. Accumulating Human Capital: Corporate Innovation and Firm Value. Int. Rev. Finance 2023. [CrossRef]

- Saroj, S.; Shastri, R.; Singh, P.; Tripathi, M.A.; Dutta, S.; Chaubey, A. In What Ways Does Human Capital Influence the Relationship between Financial Development and Economic Growth? Benchmarking 2023. [CrossRef]

- Setiawati, S.; Gursida, H.; Indrayono, Y. MSME Financial Literacy Model as a Measuring Tool for MSME Financial Performance. J. Entrep. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Qamruzzaman, M.; Rui, W.; Kler, R. An Empirical Assessment of Financial Literacy and Behavioral Biases on Investment Decision: Fresh Evidence from Small Investor Perception. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.G.; Gopalakrishna, B.V. Financial Literacy—A Regulator of Intended Investment Behaviour: Analysing the Hypothetical Portfolio Composition. Manag. Finance 2023. [CrossRef]

- Almansour, B.; Almansour, A.; Elkrghli, S.; Shojaei, S.A. The Investment Puzzle: Unveiling Behavioral Finance, Risk Perception, and Financial Literacy. Economics 2024, 13, 131–151. [CrossRef]

- Mudzingiri, C. The Effect of Financial Literacy Confidence on Financial Risk Preference Confidence: A Lab Experiment Approach. SAGE Open 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Widagdo, B.; Sa’diyah, C. Business Sustainability: Functions of Financial Behavior, Technology, and Knowledge. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Is, R.; Kv, S.; Hungund, S.S. MSME/SME Financial Literacy: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Raj, R.; Dash, B.; Kumar, V.; Paliwal, M.; Chauhan, S. Access to Finance and Its Impact on Operational Efficiency of MSMEs: Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Personality and Self-Efficacy. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Charfeddine, L.; Umlai, M.I.; El-Masri, M. Impact of Financial Literacy, Perceived Access to Finance, ICT Use, and Digitization on Credit Constraints: Evidence from Qatari MSME Importers. Financ. Innov. 2024, 10, 15. [CrossRef]

- Harsanto, B.; Pradana, M.; Firmansyah, E.A.; Apriliadi, A.; Ifghaniyafi Farras, J. Sustainable Halal Value Chain Performance for MSMEs: The Roles of Digital Technology, R&D, Financing, and Regulation as Antecedents. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2397071. [CrossRef]

- Ključnikov, A.; Civelek, M.; Kupec, V.; Badie, N.B. Breaking Down Entrepreneurial Barriers: Exploring the Nexus of Entrepreneurial Behavior, Innovation, and Bank Credit Access through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Teng, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, M. Commercial Credit, Financial Constraints, and Firm’s R&D Investment: Evidence from China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Salmoran, J.R.; Calderon, Y.P.; Espindola, M.T.E.; Mendez, A.M. Development Bank Support for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Mexico during Crisis Periods. Telos 2025, 27, 27–43. [CrossRef]

- Talip, S.N.S.H.; Wasiuzzaman, S. Influence of Human Capital and Social Capital on MSME Access to Finance: Assessing the Mediating Role of Financial Literacy. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Nguyen, T.V.H.; Nguyen, S.; Nguyen, H. Does Planned Innovation Promote Financial Access? Evidence from Vietnamese SMEs. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2023, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Rita, M.R.; Nastiti, P.K.Y. The Influence of Financial Bootstrapping and Digital Transformation on Financial Performance: Evidence from MSMEs in the Culinary Sector in Indonesia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2363415. [CrossRef]

- Sendra-Pons, P.; Comeig, I.; Mas-Tur, A. Institutional Factors Affecting Entrepreneurship: A QCA Analysis. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Darnihmedani, P.; Block, J.; Jansen, J. Institutional Reforms and Entrepreneurial Growth Ambitions. Int. Small Bus. J. 2024, 42, 805–840. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, W.; Xiang, D. Political Turnover and Innovation: Evidence from China. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 2022, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Montes, G.; Nogueira, F.S.L. Effects of Economic Policy Uncertainty and Political Uncertainty on Business Confidence and Investment. J. Econ. Stud. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Meng, B.; Ullah, I. Uncertainty and Green Innovation Nexus: The Moderating Influence of Ownership Structure and Product Market Competition. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Omeje, A.N.; Mba, A.J.; Anyanwu, O. Impact of Insecurity on Enterprise Development in Nigeria. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ciocoiu, C.N.; Radu, C.; Colesca, S.; Prioteasa, A.-L. Exploring the Link between Risk Management and Performance of MSMEs: A Bibliometric Review. J. Econ. Surv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rupeika-Apoga, R.; Petrovska, K. Barriers to Sustainable Digital Transformation in Micro-, Small-, and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Piao, X.; Managi, S. The Role of Female Managers in Enhancing Employee Well-Being: A Path through Workplace Resources. Unpublished Work 2022. [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, M.A.; Sepúlveda Velásquez, J.; Ortúzar, S. Gender and Decision-Making Styles in Male and Female Managers of Chilean SMEs. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2023, 36, 289–334. [CrossRef]

- Luque-Vílchez, M.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, P.; Guerrero-Baena, M.D. The Gender of the CEO as a Determinant of Company Survival: The Case of Spanish Agri-Food SMEs. Rev. Galega Econ. 2019, 28, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Giraldo, C.A.; Rueda-Mahecha, Y.M.; Moreno-Suarez, A.M. Innovation in MSMEs through Collaborative Networks and the Use of ICTs. Techno Rev. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ortega Fernández, E. SEO: Key for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Growth. Opción 2015, 31(Special Issue 6), 652–675.

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533.

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Delgado, M.; Cernadas, E.; Barro, S.; Amorim, D.; Fernández-Delgado, A. Do We Need Hundreds of Classifiers to Solve Real World Classification Problems? J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 3133–3181. http://jmlr.org/papers/v15/delgado14a.html.

- Bischl, B.; Lang, M.; Kotthoff, L.; Schiffner, J.; Richter, J.; Studerus, E.; Casalicchio, G.; Jones, Z.M. mlr: Machine Learning in R. Unpublished Work 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309321208.

- Biau, G.; Scornet, E. A Random Forest Guided Tour. Test 2016, 25, 197–227. [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăgu, L. Random Forest in Remote Sensing: A Review of Applications and Future Directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 114, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Barboza, F.; Kimura, H.; Altman, E. Machine Learning Models and Bankruptcy Prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 83, 405–417. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Dowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. Unpublished Work 2002. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220543125.

- Fernández, A.; García, S.; Herrera, F.; Chawla, N.V. SMOTE for Learning from Imbalanced Data: Progress and Challenges, Marking the 15-Year Anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 863–905.

- Géron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019.

- Zhou, Z.-H. Machine Learning; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021.

- Raschka, S.; Mirjalili, V. Python Machine Learning: Machine Learning and Deep Learning with Python, Scikit-Learn, and TensorFlow 2, 3rd ed.; Packt Publishing: Birmingham, UK, 2020.

- Laabs, B.-H.; Westenberger, A.; König, I. Identification of Representative Trees in Random Forests Based on a New Tree-Based Distance Measure. Unpublished Work 2022. [CrossRef]

- López, V.; Fernández, A.; García, S.; Palade, V.; Herrera, F. An Insight into Classification with Imbalanced Data: Empirical Results and Current Trends on Using Data Intrinsic Characteristics. Inf. Sci. 2013, 250, 113–141. [CrossRef]

- Hoyos, O.; Castro Duque, M.; Toro León, N.; Trejos Salazar, D.; Montoya-Restrepo, L.A.; Montoya-Restrepo, I.A.; Duque, P. Gobierno Corporativo y Desarrollo Sostenible: Un Análisis Bibliométrico. Rev. CEA 2023, 9, e2190. [CrossRef]

- González Torres, A.; Pereira Hernández, M.L.; Lacruhy Enríquez, C.C. Desigualdad Tecnológica en las MIPYMES: Un Diagnóstico desde la Ciudad de México. RIDE Rev. Iberoam. Investig. Desarro. Educ. 2025, 15, 824.

- Ramírez, J.L.A.; Howlet, L.C.P.; Sánchez, M.G.P. Impacto de las Competencias Digitales en la Brecha Digital. Excel. Adm. Online 2024, 3(7). [CrossRef]

- Consejo Latinoamericano X.R.O. Políticas Públicas de Apoyo a las MIPYMES en América Latina y el Caribe; Consejo Latinoamericano X.R.O., 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).