3.1. Synthesis

According to Reaxys search [

24], here is synthetic routes overview of different methods for preparing paclobutrazol (

Figure 2).

Step 1 (N-alkylation): The initial step involves distinct approaches depending on the starting materials:

Approach A - Starting from pre-formed triazole derivatives:

Base-mediated alkylation: Using potassium hydroxide with polyethylene glycol in isopropanol (75-80°C), giving excellent yield (93.8%) with high purity [

25].

Hydride-mediated alkylation: Using sodium hydride in DMF (10-20°C), yielding the product in 76.3% as colorless crystals with melting point 124°C [

26].

Alternative hydride-mediated alkylation: Employing sodium hydride in tetrahydrofuran as reported by Min

et al. [

27].

Approach B - Starting directly from 1H-1,2,4-triazole:

Phase-transfer facilitated reaction: Combining 1

H-1,2,4-triazole, chlorinated ketone, and

p-chlorobenzyl chloride in toluene at 55°C with tetrabutylammonium bromide and sodium hydroxide [

25].

Direct triazole alkylation: Using sodium hydride in tetrahydrofuran as described by Min

et al. [

27], followed by subsequent reactions to introduce the

tert-butyl moiety.

Step 2 (Chiral resolution): The resolution of the racemic intermediate can be achieved through two distinct approaches:

Temperature-controlled base-mediated resolution: Using sodium hydroxide in methanol/water with careful temperature control from 30°C to 24.5°C as reported by Black

et al. [

28].

Combined grinding and crystallization resolution: A two-stage process developed by Lopes

et al. [

29] beginning with grinding in the presence of zirconium(IV) oxide and sodium hydroxide followed by resolution in ethanol/2-methylpentan.

Solvent-based resolution: Resolution in methanol/water as reported by Levilain

et al. [

30].

Step 3 (Stereoselective reduction): The final step is consistent across all methods, involves

sodium borohydride reduction in methanol at 5°C for 2 hours, providing excellent yield (93.5%) as reported by Black

et al. [

28]. This synthesis strategy demonstrates the versatility of approaches to paclobutrazol preparation, with options for different starting materials, reaction conditions, and resolution techniques that can be selected based on available resources, scale requirements, and desired stereochemical outcomes.

Building on the established synthetic methodologies for paclobutrazol, we developed two distinct routes (

Figure 3) for preparing our target derivatives (compounds

1-

26): etherification with substituted benzyl, alkenyl, or hetaryl halides using sodium hydride (Method A), and esterification mediated by pivalic anhydride and DMAP (Method B).

The derivatives were designed to incorporate the following types of groups: triazole scaffold, indicating its potential for target recognition and binding; alkyl, alkenyl, phenyl, naphthyl, hetaryl, halogen, trifluoromethyl, CN, OMe, NO2, or COOMe substituents, implying its role in modulating activity or physicochemical properties, influencing binding orientations, hydrogen bonding, or other interactions with the target; alkyl linkers of varying lengths, suggesting flexibility in the linker region is tolerated for target binding; presence of an oxygen atom in the linker region may introduce hydrogen bonding capabilities or affect conformational preferences; phenyl rings at the terminal positions could be involved in hydrophobic interactions or π-stacking with the target; cycloalkyl groups may contribute to lipophilicity and potential membrane permeability; additional heterocycles may modulate target affinity, selectivity, or physicochemical properties; presence of multiple substituents may create specific electronic environments or/and steric demands for target binding.

Key features like chemical shifts, coupling patterns, and substitutions on the aromatic rings and alkyl chains are clearly evident from the spectral data across

1H,

13C,

19F NMR, and IR for these series of derivatives (

Supplementary Material, Spectral data).

Hence, the

1H NMR spectrum (δ, ppm) of reported paclobutrazol (SDBS No 53084) [

31], assigned with heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence (HMQC) and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC), exhibits a singlet at 8.51, corresponding to the triazole NH proton. Also, the aromatic region shows one singlet of triazole CH at 7.76 and two doublets of phenyl protons at 7.23 and 7.11, respectively. Additional multiplet is observed at 4.76, corresponding to CH-triazole. The aliphatic region features doublet at 3.44 for CH-

tert-Bu (or oxymethine), and doublet of doublets at 3.25 and 3.12 for Ph-CH

2. And tertiary butyl methyles’ nine-proton singlet appears at 0.62.

Its 13C NMR spectrum (δ, ppm) displays six distinct resonances (149.29, 143.66, 136.79, 130.91, 130.64 (2C), and 127.96 (2C)), attributable to the aromatic carbons: triazole’s, and phenyl’s. The signal at 76.91 corresponds to the oxymethine carbon, and at 62.24 to the methylene carbon adjusted to triazole. Aliphatic resonances are observed at 39.26 for Ph-CH2, 34.69 for CH-(CH3)3 and 28.6 (3C) assigned to the tert-butyl methyl carbon.

And paclobutrazol IR spectrum (ν, cm

-1) exhibits a broad absorption band centered at 3407, which is attributed to the N-H stretching vibration of the triazole. The aromatic C-H stretches are observed as bands at 3128 and 3100. The aliphatic C-H stretching modes appear as intense vibrations at 2913 and 2871, corresponding to the methyl and methylene groups, respectively. In the fingerprint region, the bands at 1517 and 1497 are characteristic of the aromatic C=C stretching. The bands at 1438, 1410 are assigned to the C-H bending modes of the

t-butyl methyl groups along with C-N stretching vibrations of the triazole at 1395 and 1363. Furthermore, the strong bands at 1219 and 1199 could be attributed to the C-N stretching vibrations of the triazole ring system, and methyls in

tert-butyl group [

32]. The absorption at 1036 corresponds to the C-Cl stretching mode of the chlorinated carbon. The bands at 913 and 891 are likely due to the out-of-plane C-H bending vibrations of the aromatic ring system. Finally, the absorptions at 681, 662, 517 and 479 could be assigned to the various C-C and C-N bending modes within the paclobutrazol molecule.

So, considering 1H NMR spectra (δ, ppm) of three first synthesized compounds 1-3, they exhibit the singlets around 8.2-8.4 and 7.8-7.9 corresponding to the triazole protons; two doublets in the aromatic region (6.9-7.2) with coupling constants ~8 Hz, attributed to the para-substituted phenyl ring of 1-3, and additional phenyl of 3. Compound 1 demonstrates one proton multiplet at 5.9-5.8 and two proton multiplet at 5.10-4.98 for the terminal alkene group, and for 2 it is shown at 5.41 as one proton triplet of doublets. One proton signal is observed at ~ 4.8 for CH-triazole of 1 and 2 as multiplet or doublet doublet of doublets, and the multiplet signal of oxymethine proton is found at ~3.1-3.3, that downfield-shifted to 5.3 and 5.0 for 3, respectively. The OCH2 signals are found at 3.7 for 1, and 4.1-4.3 for 2, and CH2Ph is registered at 3.4-3.1 for 1-3. Also, signals of methylenes and methyls are shown at ~ 0.7-2.3.

In 13C NMR (δ, ppm) spectra compounds 1-3 show signals of the triazole carbons at 134-151; in the 124-135 range for the phenyl carbons; around 87 for the oxymethine carbon; in the 63-74 range for methylenes adjacent to oxygen; around 26-29 for the tert-butyl methyls. Compound 3 exhibits additional signals around 167 and 161 ppm for the oxadiazole carbons, and at 133 and 110 for alkene carbons of 1, and at 137 and 121 for 2.

Common features of 1-3 IR (ν, cm-1) data are: bands in the 2956-2961 range for aliphatic C-H stretches; at ~1490-1500 for aromatic C=C stretches; at 1375 for tert-butyl bending; in the 1200-1277 range for C-N and C-O stretches; at ~1090-1141 for C-O-C stretches; and at ~682-811 for aromatic C-H bends.

Considering 1H NMR (δ, ppm) of derivatives 7-19, they have: singlet around 8.0-8.4 for triazole N-H; aromatic signals in 6.8-8.1 range; signals for CH-triazole at 4.7-4.9. Oxymethine signals are overlapped with benzyl methylenes of 14-18 and registered at 3.1-3.5 as three proton signals, and for 7-13 are found separately as two proton doublets at 3.1-3.4. Additional aliphatic methylenes of 15-19 are found at 1.7-4.2, and tert-butyl methyl singlet around 0.7-0.9. Singlet of methyl group of 13 is found at 3.91.

Their characteristic 13C NMR data (δ, ppm) are: ester/amide carbonyl carbons 167-169 ppm (13, 14); two triazole carbons around 144-160; aromatic/olefinic signals in 110-145 range; oxymethine carbon in 85-90; CH2-triazole around 60-77; tert-butyl methyl carbon around 26-27. And compounds 9-11 show nitrile carbon at 118-119.

In 19F NMR spectra (δ, ppm) of 8, 15-17 signals are registered at -61 to -114.

IR (ν, cm-1): N-H stretch at ~3420-3450; C-H stretches at ~2950-2965; ester C=O stretches at 1719; C≡N at 2226-2229 (9-11); aromatic C=C at ~1490-1620; C-N, C-O stretches in 1200-1300 range; C-F absorptions at 1110-1330 (8, 15-17); N=O of nitro group at 1609-1788 range (18, 19); and fingerprint aromatic C-H bends at ~650-840.

The ester and amide derivatives 4-6, 20-26 in 1H NMR (δ, ppm) spectra have the following signals: singlet around 7.8-8.3 for triazole N-H; additional amide NH of 5 shows at 8.31, 24 at 8.29, 26 at 8.36, and 6 at 9.17, and aromatic signals in 6.0-7.9 range. The doublets for CH-triazole at 5.0-5.2; ddd of oxymethine protons - in 4.7-4.9 range; two proton multiplet of CH2Ph at 2.9-3.4; other aliphatic methylenes in 1.8-3.4 ppm; and tert-butyl methyl singlet around 0.7-0.9.

In 13C NMR (δ, ppm): ester/amide carbonyl carbons at 168-173, and for 22 – at 156.8; triazole carbons around 150-151; aromatic signals in 108.1-143.7 range; nitrile of 23 at 118; oxymethine carbon in 78.9-83.5 range; CH-triazole around 62-63; tert-butyl methyl carbon around 26.0; and aliphatic methylenes around 24-40.

19F NMR spectrum (δ, ppm) of 22 has a peak at -74.59 for trifluoroacetate group.

The characteristic bands of their IR (ν, cm-1) spectra are: N-H stretches at ~3435-3360; C-H stretches at ~2960-2970; ester C=O stretches at 1719-1754, and 1788 for 22; aromatic C=C at ~1490-1610; C-N, C-O stretches in 1085-1370 range; and fingerprint aromatic C-H bends at 683-810.

All mass data of LCMS-IT-TOF confirms the molecular ion peaks at m/z corresponding to the molecular formula.

We successfully synthesized and characterized twenty-six paclobutrazol derivatives with diverse structural features. To efficiently prioritize these compounds for biological testing, we employed an integrated computational screening approach to evaluate their therapeutic potential. This strategy addresses several practical and scientific challenges.

First, paclobutrazol's modest inherent antifungal activity suggests that structural modifications might enhance potency or reveal entirely new therapeutic applications. Computational target prediction enables systematic exploration of this possibility across a broad range of biological targets that would be impractical to assess experimentally for all 26 compounds. Second, the structural diversity of our library— spanning simple alkyl ethers, functionalized aromatics, amides, and heterocyclic derivatives necessitates evaluation of how these modifications influence toxicity, target binding, pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness simultaneously. Third, recent validation studies demonstrate, that modern machine learning-based prediction tools achieve accuracy comparable to medium-throughput experimental assays for initial compound prioritization [

2], making computational screening both scientifically robust and resource-efficient.

Our computational pipeline integrates five complementary methods that together provide a comprehensive pharmaceutical profile: toxicity prediction, binding affinity estimation, pathogenic target activity probability, and ADME properties with drug-likeness assessment.

3.2. In Silico Studies

3.1.1. Environmental and Human Toxicities via the CropCSM

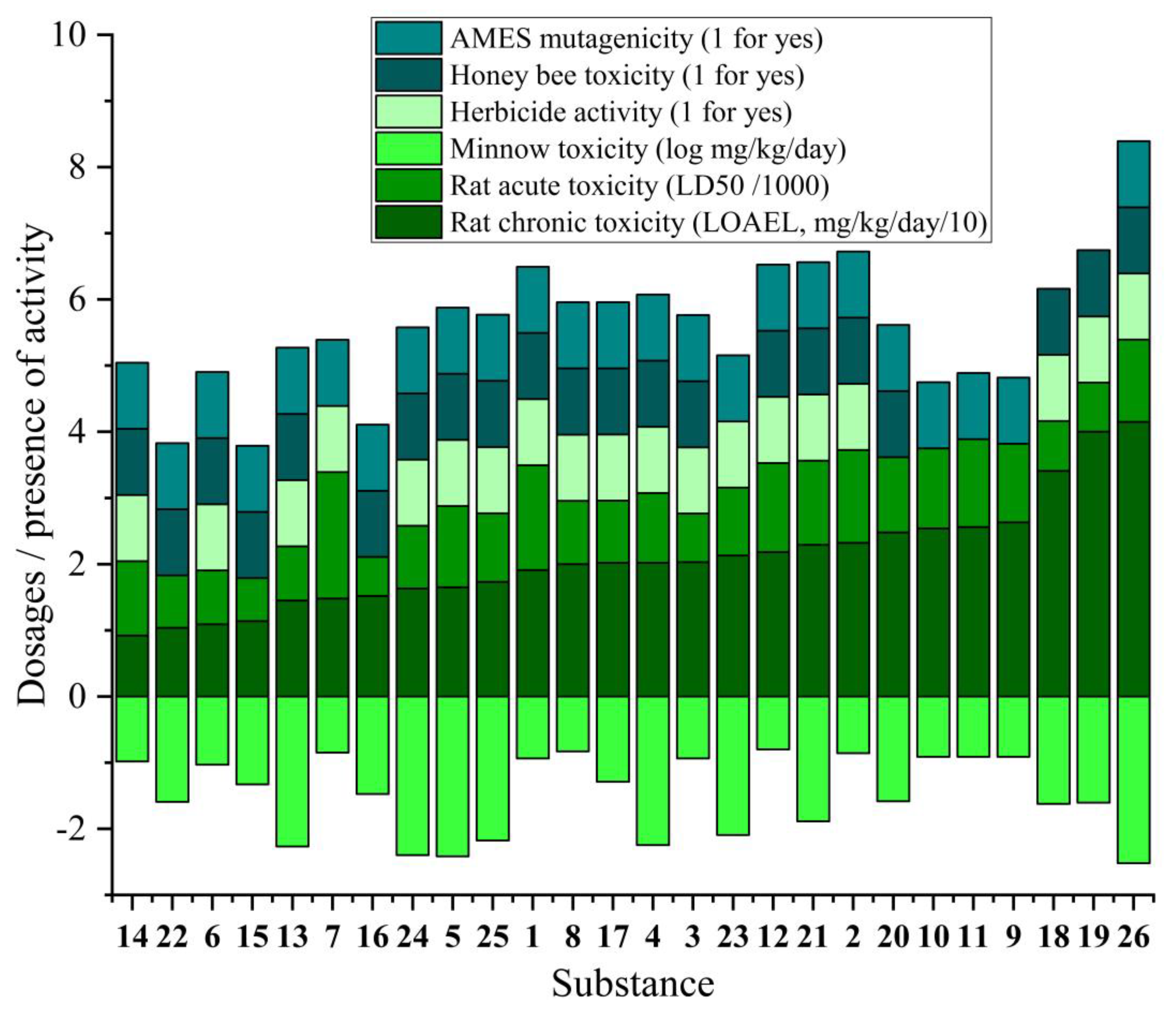

Novel compounds often exhibit enhanced biological activities while maintaining unknown levels of environmental and human safety. This analysis provides initial insights into structural features influencing the predicted toxicity profiles.

Environmental toxicity. All compounds are predicted to have no toxicity to birds (avian), but are toxic to minnows (fish) with log values below the safety threshold of -0.3. Compounds

7,

9-

11, and

23 are predicted to affect the honeybee

A. mellifera, as indicated by the colored bars in

Figure 4. Compounds

9-

11 with cyano substituents, along with the fluorinated derivatives

15 and

16, and compounds

20 and

22 demonstrate potential herbicidal activity.

Human toxicity. Compounds 18 and 19, both containing nitro-substituted aromatics, are the only substances predicted to be positive for AMES toxicity, indicating potential mutagenicity. For rat acute toxicity median lethal dose (LD₅₀), most compounds are classified as 'slightly toxic' with values exceeding 500 mg/kg, with none falling into the 'strong toxicity' category (below 50 mg/kg). Regarding rat chronic toxicity (lowest-observed-adverse-effect level, LOAEL), 14 shows the strongest predicted chronic toxicity (9.2 mg/kg/day), followed closely by 22 (10.4 mg/kg/day) and 15 (11.4 mg/kg/day), all below the threshold of 20 mg/kg/day for high chronic toxicity.

Structure-toxicity relationship analysis reveals that compounds containing halogenated aromatic rings (15-19) generally demonstrate higher predicted toxicity across multiple parameters compared to their non-halogenated counterparts. Cyano-substituted compounds 9-11 show a consistent pattern of both herbicidal activity and honeybee toxicity. Trifluoro-containing derivatives (15, 16, 22) exhibit the highest predicted chronic rat toxicity in the series. Increasing the alkyl chain length appears to reduce predicted toxicity, as evidenced by compound 21. Notably, the naphthyl-substituted compound 26 shows one of the lowest predicted rat chronic toxicity values (41.5 mg/kg/day) despite its structural complexity, suggesting it as a promising lead for further development.

It is important to note, that these predictions, while valuable for initial safety assessment and compound prioritization, require experimental validation to confirm the actual toxicological profiles of these novel derivatives.

Having established the favorable toxicity profiles of several compounds, particularly 18, 19, and 26, we next investigated their potential biological targets to gain insight into possible therapeutic applications and mechanisms of action.

3.1.2. G protein-Coupled Receptor Ligands Affinity via the pdCSM-GPCR

Its known that predicting potential interaction targets for newly synthesized compounds is crucial for several important reasons:

Drug development & safety: Helps identify both desired therapeutic effects and potential side effects early in development. Allows researchers to screen out compounds likely to have dangerous off-target interactions. Reduces the risk of adverse drug reactions and toxicity by flagging problematic interactions before clinical trials. Saves time and resources by prioritizing promising compounds and eliminating risky ones early.

Understanding mechanism of action: Reveals how a compound might work at the molecular level. Identifies which proteins, enzymes, or cellular pathways the compound affects. Helps explain observed biological effects. Guides optimization of compound structure for better efficacy.

Repurposing opportunities: May uncover beneficial interactions that suggest new therapeutic uses. Helps identify compounds that could be repurposed for treating different conditions. Expands the potential value and applications of newly synthesized molecules.

Economic benefits: Reduces costly late-stage failures in drug development. Streamlines the drug discovery process. Lowers the overall cost of bringing new drugs to market. Helps focus resources on the most promising candidates.

Research efficiency: Guides experimental design by suggesting which assays and tests to prioritize. Helps researchers focus on the most relevant biological pathways. Reduces the number of experiments needed to characterize a compound. Accelerates the overall pace of drug discovery.

Therefore, paclobutrazol has already shown inhibition of the following targets [

33]. It most potently inhibits CYP2C19 with an AC

50 of 0.12-0.13 µM. And also shows significant inhibition of multiple other CYP450 enzymes (3A4, 3A5, 2C18, 2B6, 1A1, 2C9) with AC

50 values ranging from ~1.4 to 7.6 µM. Demonstrates consistent inhibition (AC

50 ~1.48 µM) of several inflammation-related proteins: CCL2 (MCP1), ICAM1, PAI1, and uPAR. Also affects other inflammatory mediators at higher concentrations (4.44 µM): CXCL10; IL-1α; MMP1 (interstitial collagenase). It inhibits TGF-β1 signaling through multiple readouts (AC

50 1.48-4.06 µM), and this suggests potential effects on cellular growth, differentiation, and fibrosis. Also effects multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) with an AC

50 of 4.83 µM [

34]. So, it could affect drug transport and distribution.

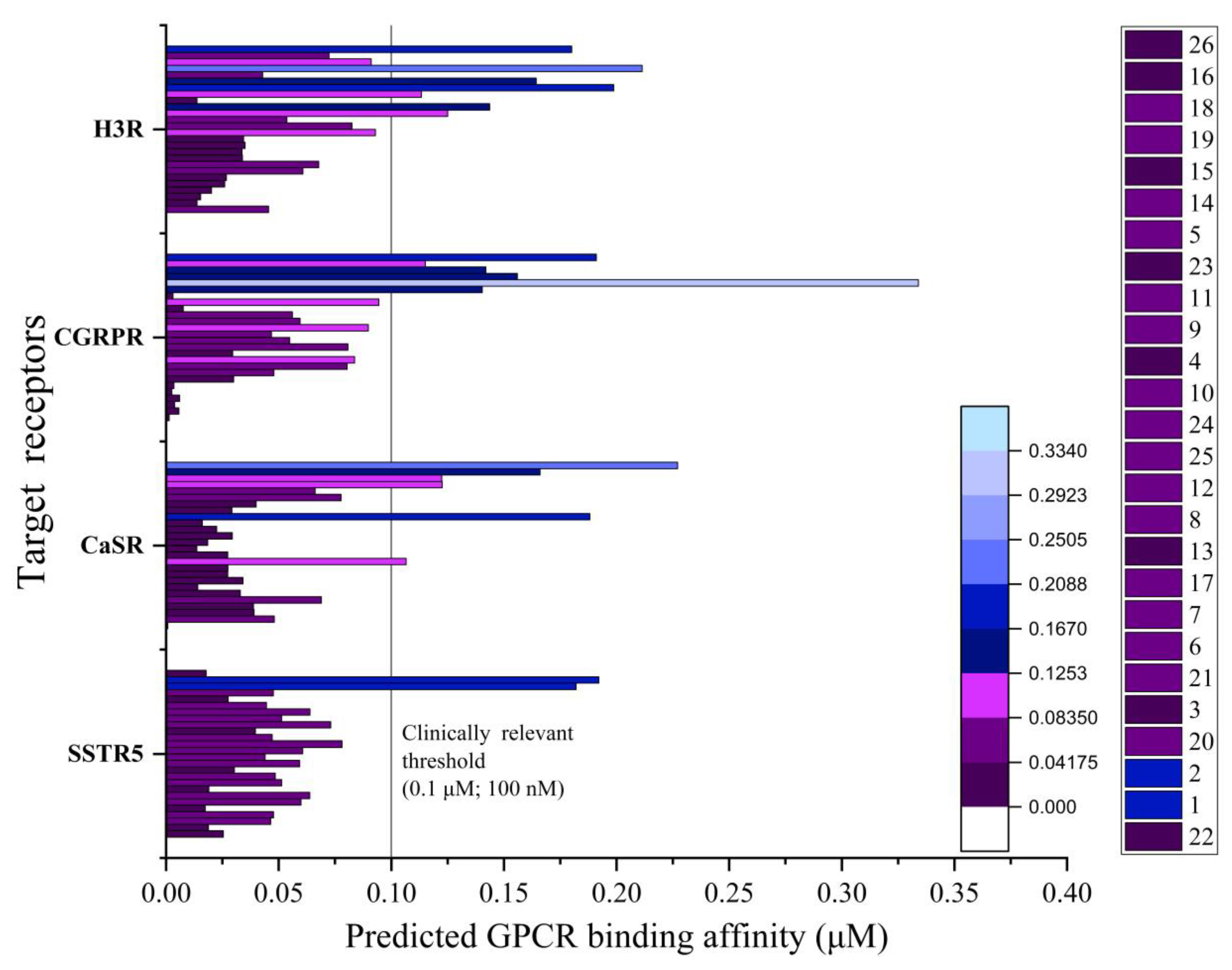

So, it was decided to predict the active concentrations of the synthesized substances against a panel of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) targets [

16], which transduce extracellular stimuli into a plethora of vital physiological processes. (

Supplementary Material, Table S3). The

Figure 5 illustrates the four GPCR targets with the lowest average calculated concentration among 36 others

via the pdCSM-GPCR model.

In the results, it was found that compound 26 displays the strongest average predicted activity (0.018 μM) against these four GPCR targets: the somatostatin type 5 (0.0254 μM), the extracellular calcium-sensing (0.0008 μM), the calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 (0.0014 μM), and the histamine H3 receptors (0.0455 μM).

The predicted binding concentration of compound

26 for the CGRP1 receptor (0.0014 μM) is particularly noteworthy. While this computational prediction cannot be directly compared to experimental IC50 values, the predicted concentration falls in the low micromolar range characteristic of potent CGRP antagonists such as rimegepant (experimental IC50 ~0.010 μM [

35]), suggesting compound

26 may warrant experimental validation as a CGRP1R modulator. The next most potent compounds against these targets were

16 (0.022 μM),

18 (0.026 μM),

19 (0.028 μM), and

15 (0.029 μM).

Furthermore, the

Supplementary Material, Table S3 shows that different compounds exhibit varying activity profiles across the GPCR targets, indicating the potential for selective modulation of specific receptor systems based on the structural modifications introduced. Among all synthesized substances, the highest specific activities (μM) were predicted against metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 for

4 (0.0005),

5 (0.0017),

19 (0.0047),

18 (0.0053); against extracellular calcium-sensing receptor for

26 (0.0008); and against calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor for

26 (0.0014),

15 (0.0026),

6 (0.0031),

14 (0.0034),

18 (0.0038),

16 (0.0057),

19 (0.0060), and

17 (0.0076).

The next calculated best targets with average predicted concentrations of 0.128-0.269 μM were: prostaglandin D2 receptor 2 (0.128), alpha-1A adrenergic receptor (0.133), smoothened homolog (0.135), 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 6 (0.142), D(4) dopamine receptor (0.171), P2 purinoceptor subtype Y1 (0.187), metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 (0.192), G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (0.214), and prostaglandin E2 receptor EP1 subtype (0.269).

The less potent activities (0.8-6.6 μM) tend to be against receptors involved in signaling pathways related to neurological processes, inflammation, and metabolism: sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 5; muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M5; substance-K receptor; metabotropic glutamate receptor 4; hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2; sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3; melanin-concentrating hormone receptors 1; 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A; endothelin receptor type B; mu-type opioid receptor.

Hence, based on the predicted activities and targets, when the in silico results are experimentally confirmed, it could potentially lead to therapeutic applications in the following diseases or conditions:

Migraine and neurological disorders: calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor (CGRP1R) plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of migraine and other neurological disorders.

Calcium metabolism disorders: extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) plays a vital role in maintaining calcium homeostasis, and mutations or dysregulation of this receptor can lead to various disorders affecting calcium metabolism, parathyroid function, and bone health.

Neuroendocrine disorders: somatostatin receptors are involved in the regulation of various neuroendocrine functions, including growth hormone secretion, insulin release, and gastrointestinal motility. Modulating these receptors could have therapeutic implications in the treatment of conditions such as acromegaly, neuroendocrine tumors, and gastrointestinal disorders.

Neurological and psychiatric disorders: the metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (mGluR4) is a G protein-coupled receptor that is involved in the modulation of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the central nervous system. Dysregulation or alterations in the function of mGluR4 have been associated with several neurological and psychiatric disorders, including: Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, anxiety and depression substance abuse disorders, and chronic pain.

Inflammation and pain: the predicted activity against the histamine H3 receptor indicates potential anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties.

However, binding data alone does not indicate functional activity (agonist/antagonist/inverse agonist). Further studies on functional effects, selectivity over other targets, pharmacokinetic properties, etc. would be needed to properly evaluate therapeutic potential. Nevertheless, the in silico results provide a valuable starting point for further investigation and optimization of the lead compounds.

3.1.3. Activity Probability via the MolPredictX

Beyond GPCR-targeting predictions, we employed MolPredictX [

17] to evaluate the broader biological potential of our compounds against multiple pathogenic targets.

Figure 6 presents the predicted activity probabilities (scale 0-1.0) for all synthesized compounds against a diverse panel of fungal, bacterial, parasitic, and viral targets.

The notable observation was the uniformly high activity predicted against Candida albicans, with all compounds except 3 showing maximum probability (1.0). This strong antifungal potential aligns with our earlier GPCR predictions and sterol 14-alpha demethylase binding studies, providing multiple lines of computational evidence for the antifungal potential of these derivatives.

The compounds also demonstrated significant predicted activity against parasitic targets, particularly Trypanosoma cruzi in its various life cycle stages (trypomastigota, amastigota, and epimastigota). Compounds 1, 4, 8, 14-19 exhibited especially strong probabilities (0.8-1.0) against multiple T. cruzi forms, suggesting potential application as antiparasitic agents. Similarly, several compounds showed moderate to high activity against different Leishmania species, with 8, 14, and 19 being particularly noteworthy for their consistent activity across multiple Leishmania forms.

Regarding non-infectious targets, virtually all compounds (24 of 26) demonstrated maximum predicted activity (1.0) against the Alzheimer's disease NADPH target. This unexpected finding suggests potential neuroprotective properties that align with our earlier GPCR predictions, particularly for receptors involved in neurological signaling pathways.

Antibacterial potential was also evident, with compounds 1, 4, 6, 17-19 showing high probabilities (0.8-1.0) against Escherichia coli and several compounds demonstrating moderate activity against Salmonella enterica. The nitro-substituted derivatives 18 and 19, which also showed favorable toxicity profiles, demonstrated the broadest spectrum of predicted activities across all categories.

For viral targets, including hepatitis C (various mechanisms) and SARS-CoV, the predictions were more modest (0.2-0.8), suggesting lower but still detectable potential antiviral properties. Compounds 4, 21, 23, 25, and 26 showed notable activity against hepatitis C RNA-dependent targets (probability 0.8-1.0).

Structure-activity relationship analysis revealed that compounds with nitro substitutions (18, 19) or extended alkyl linkers connected to aromatic moieties (15-19) generally demonstrated broader-spectrum activity profiles. Conversely, 3, containing an oxadiazole moiety, showed the most limited activity spectrum, suggesting this structural modification may reduce biological promiscuity.

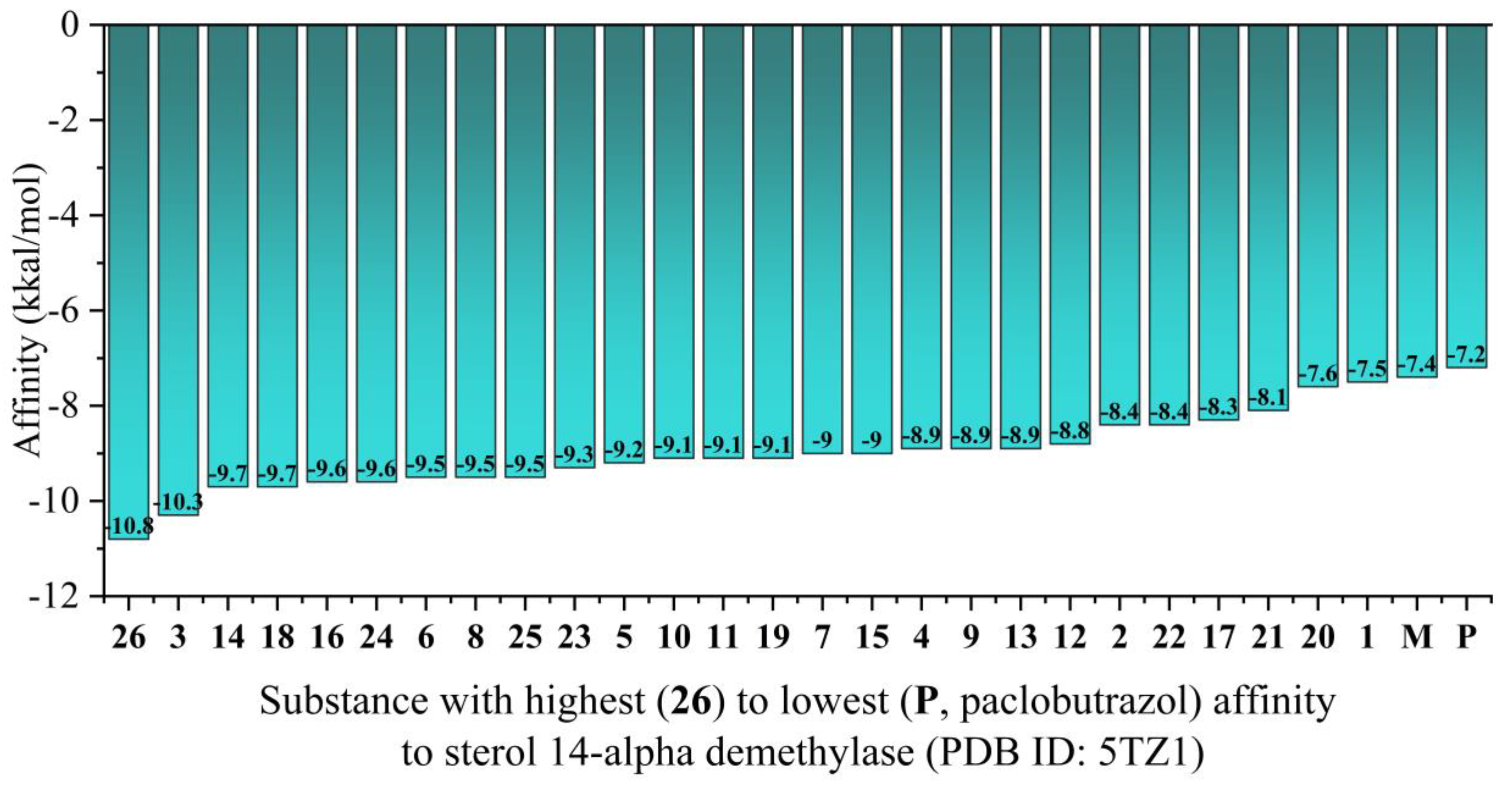

3.1.4. Molecular Docking via the CB-Dock2

Based on the high probability of activity against

C. albicans predicted by MolPredictX [

17] and the previously reported inhibition of multiple CYP450 enzymes by paclobutrazol [

34], we conducted molecular docking studies to evaluate the binding interactions of compounds with a key antifungal target, sterol 14-alpha demethylase (CYP51, PDB ID: 5TZ1 [

20]). a crucial enzyme in ergosterol biosynthesis essential for fungal cell membrane integrity.

Figure 7 displays the calculated binding affinities

via the CB-Dock2 website [18, 19] (

Supplementary Material, Table S5).

Structure-activity relationship analysis revealed that introduction of larger aromatic systems (naphthyl in 26), heterocycles (oxadiazole in 3), or functionalized aromatic rings (nitro groups in 18, CF₃ in 16) significantly enhanced binding affinity. This suggests these modifications create favorable interactions with the enzyme's binding pocket, potentially through additional hydrophobic contacts, π-stacking interactions, or hydrogen bond[18,19ing networks.

The binding affinity values observed for our top compounds (−10.8 to −9.5 kcal/mol) fall within the range typically associated with potent enzyme inhibitors, where values more negative than −9.0 kcal/mol often correlate with nanomolar-range inhibitory activity. This represents a notable improvement over the parent paclobutrazol, whose modest affinity (−7.2 kcal/mol) aligns with its known limited antifungal activity.

These molecular docking results provide mechanistic support for the antifungal activity predictions from our earlier analyses and identify sterol 14-alpha demethylase inhibition as a probable mechanism of action for these derivatives. The substantial improvement in binding affinity compared to paclobutrazol suggests our structural modifications have successfully enhanced the antifungal potential of this scaffold.

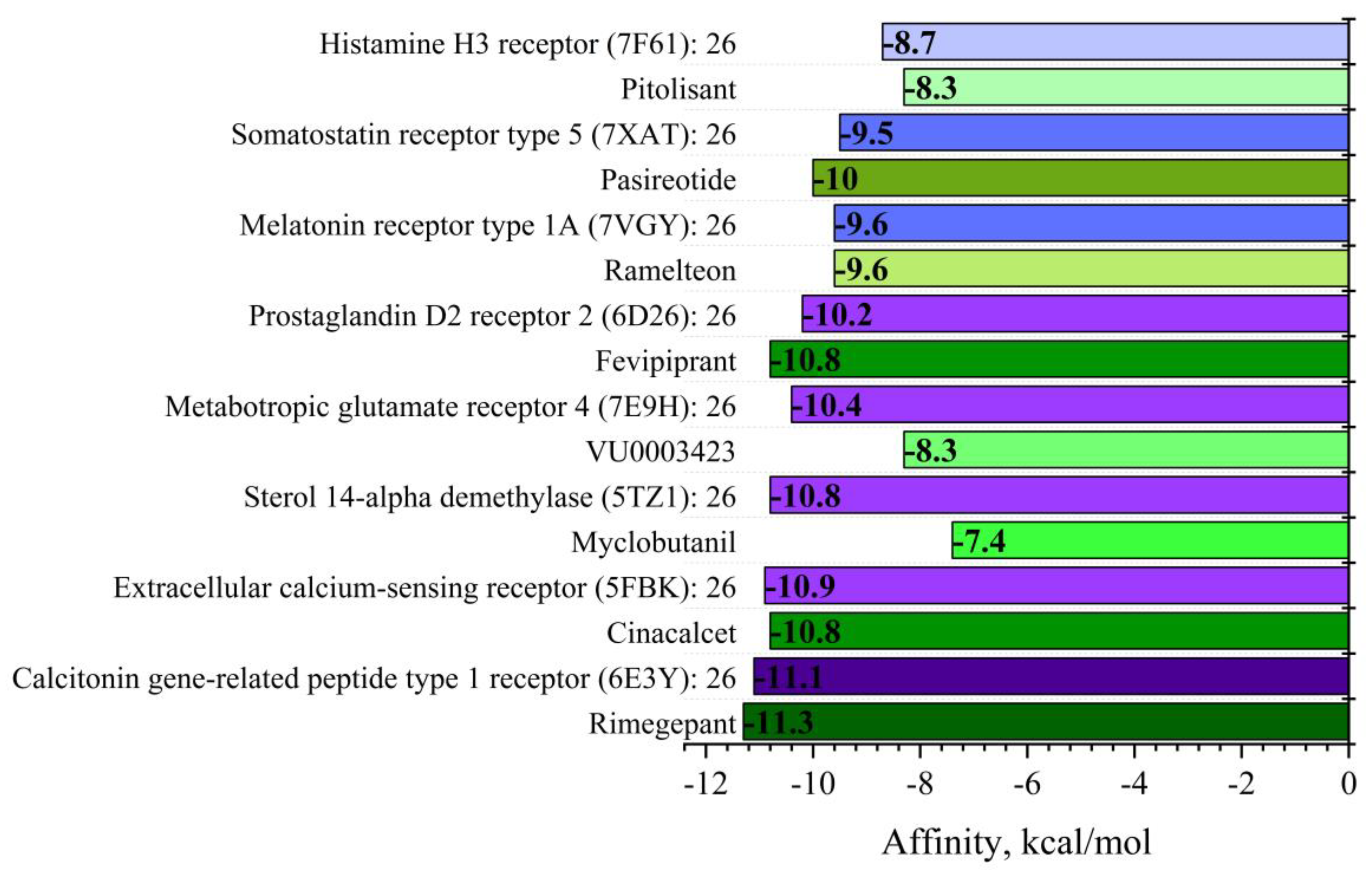

Moreover, considering the robust GPCR-targeting potential predicted by the pdCSM-GPCR website [

16] (

Supplementary Material, Table S3), we conducted additional molecular docking studies with compound

26, the most promising lead based on combined antifungal and GPCR-binding profiles. We selected eight high-priority GPCR and related targets identified earlier in analysis for further binding affinity assessment (

Figure 8).

The docking results revealed strong binding versatility of compound

26, with strong predicted affinities across all evaluated targets (−8.7 to −11.1 kcal/mol). Most notably, compound

26 exhibited outstanding affinity for the calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor (CGRP1R, −11.1 kcal/mol) and the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR, −10.9 kcal/mol)—both exceeding its already impressive affinity for the antifungal target sterol 14-alpha demethylase (−10.8 kcal/mol). For context, the binding affinity of compound

26 for CGRP1R (−11.1 kcal/mol) is comparable to rimegepant (−11.3 kcal/mol,

Supplementary Material, Table S6a), a FDA-approved CGRP antagonist for migraine treatment [

35,

37,

38]. Strong binding was also observed for somatostatin receptor type 5 (−9.5 kcal/mol), metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (−10.4 kcal/mol), and prostaglandin D2 receptor 2 (−10.2 kcal/mol).

The notable high affinity for CGRP1R is particularly significant, as this receptor plays a crucial role in pain signaling, neurogenic inflammation, and vasodilation. This finding aligns with our pdCSM-GPCR predictions, where compound

26 showed the lowest predicted concentration (0.0014 μM) against this target. Recent FDA-approved migraine therapies target this receptor [

39], suggesting potential applications of paclobutrazol derivatives in neurological disorders.

Similarly, the strong binding to CaSR (-10.9 kcal/mol) indicates potential utility in disorders of calcium homeostasis, where this receptor serves as a key regulator of parathyroid hormone secretion and calcium metabolism, as demonstrated in clinical applications with cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism [

40]. The binding to somatostatin receptor type 5 suggests possible applications in neuroendocrine disorders such as Cushing's disease [

41], while affinity for metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 suggests antiparkinsonian potential [

42]. The strong binding to prostaglandin D2 receptor 2 (−10.2 kcal/mol) could be leveraged for anti-inflammatory applications, particularly in allergic asthma [

43].

The binding to histamine H3 receptor (−8.7 kcal/mol) further expands potential applications into cognitive disorders and narcolepsy, as indicated by the therapeutic effects of pitolisant [

44], while the affinity for melatonin receptor type 1A suggests applications in sleep disorders similar to ramelteon [

45].

The multi-target binding profile of compound 26 suggests a notable versatility that spans from antifungal activity to potential applications in neurological, endocrine, and inflammatory conditions. To better understand the binding interactions responsible for this strong affinity, we conducted detailed visualization of the binding mode of compound 26 with its highest-affinity target, CGRP1R.

Hence, in

Figure 9 there is shown a 3D visual representation of the lead compound

26 vs rimegepant bounding within the active site of the calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor (CGRP1R) (

Supplementary Material, Table 6b).

Detailed comparative analysis of compound 26 with rimegepant reveals the molecular basis for their comparable CGRP1R binding affinities (−11.1 vs −11.3 kcal/mol). Both compounds engage similar amino acid residues but through distinct interaction patterns. Compound 26 forms strong conventional hydrogen bonds with SER191 (3.02 Å) and ARG150 (3.24 Å), while rimegepant establishes multiple hydrogen bonds with SER191 at comparable distances (3.20 Å and 3.30 Å), indicating this residue serves as a common recognition element.

The interaction with CYS233 represents another significant similarity, though achieved through different binding mechanisms. While rimegepant forms a conventional hydrogen bond with this residue (3.67 Å), compound 26 engages CYS233 through π-sulfur interactions (3.78 Å). This cysteine residue appears crucial for stabilizing both ligands within the binding pocket, despite the different interaction types.

Carbon hydrogen bonding patterns also differ between the compounds. Compound 26 interacts with ILE232 (3.48 Å) and VAL276 (3.34 Å), while rimegepant forms carbon hydrogen bonds with SER275 (3.32 Å) and PHE234 (3.53 Å). These subtle differences in hydrogen bonding networks may contribute to the slight variations in binding energies between the two compounds.

The hydrophobic interaction profiles show notable convergence, with both molecules establishing extensive networks of alkyl and π-alkyl interactions with a shared set of residues including ARG150, CYS148, ALA231, PRO107, and LEU192. The naphthyl moiety of compound 26 appears to occupy a spatial position similar to the aromatic centers in rimegepant, enabling comparable hydrophobic interactions with the receptor pocket at distances ranging from 4.8-5.4 Å.

Notably, compound 26 forms a distinctive π-σ interaction with ARG150 (3.96 Å) not observed with rimegepant, potentially contributing to its strong binding affinity. Conversely, reference compound uniquely engages with HIS62 through halogen interactions (3.58 Å) involving its fluorine atoms.

The strong binding affinity of compound 26 for CGRP1R (−11.1 kcal/mol) prompted detailed comparative analysis with rimegepant, revealing critical insights into their comparable binding mechanisms. The convergent interaction patterns, particularly with key residues SER191 and CYS233, coupled with extensive hydrophobic networks, suggest that despite their structural differences, both compounds achieve potent CGRP1R binding through overlapping pharmacophoric elements. This structural insight supports the potential therapeutic application of compound 26 or its derivatives in migraine and pain management through CGRP1R modulation.

Overall, obtained binding data guides prioritization of compounds and targets for deeper investigation in drug discovery in the directions of:

Neurological disorders: calcitonin gene-related peptide type 1 receptor (6E3Y): migraine, neurogenic inflammation; metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 (7E9H): Parkinson's disease, anxiety disorders; melatonin receptor type 1A (7VGY): insomnia, circadian rhythm disorders; histamine H3 receptor (7F61): cognitive disorders, sleep disorders.

Endocrine disorders: extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (5FBK): calcium homeostasis disorders, parathyroid disorders.

Fungal diseases: sterol 14-alpha demethylase (5TZ1): fungal infections, cholesterol biosynthesis disorders.

Inflammatory conditions: prostaglandin D2 receptor 2 (6D26): asthma, allergic inflammation.

Neuroendocrine disorders: somatostatin receptor type 5 (7XAT): acromegaly, neuroendocrine tumors.

The next steps of investigation were prediction of substances’ pharmacokinetic properties and drug-likeness fitness.

3.1.5. ADME Properties via the pkCSM

Absorption:

Water solubility (logS): values range from −7.56 (16) to −4.20 (3), with most compounds having predicted low water solubility below the favorable threshold of -4, which may impact formulation strategies.

Caco-2 permeability (logPapp): values between 0.58 (18) and 1.60 (17) exceed the favorable threshold of 0.90, indicating good to excellent predicted permeability across the Caco-2 cell monolayer model for most compounds.

Intestinal absorption (%): most compounds are predicted to have high (>90%) intestinal absorption, which is desirable for oral drugs.

Skin permeability (log Kp): values around −2.5 - −2.8 suggest low skin permeability, an important consideration for transdermal delivery.

P-glycoprotein substrate: 7 compounds (

5,

6,

10,

11,

14,

24,

26) are predicted P-gp substrates as shown in

Table S7c, which may reduce intestinal absorption and brain penetration. Notably, lead compound

26 is among these P-gp substrates, which could potentially limit its CNS penetration despite its high CGRP1R binding affinity.

P-glycoprotein I/II inhibitors: all compounds are predicted P-gp inhibitors (except 2, 20, 22, which are not II type inhibitors), so could impact the pharmacokinetics of co-administered P-gp substrate drugs.

Distribution:

Volume of distribution (log L/kg): values between -0.39 and 0.46 are low to moderate, indicating limited distribution outside the blood compartment.

Blood-brain barrier (log BB): compounds 4, 5, and 18-19 show negative values below -1 (ranging from −1.121 to −1.488), suggesting poor brain penetration, while compounds 1, 2, 7, 8, 12, and 20-23 show values above 0, indicating favorable BBB penetration. This variability offers opportunities to select compounds with CNS activity or peripheral-only effects based on therapeutic goals.

CNS permeability (logPS): the average negative values (about −2) indicate ability to penetrate the central nervous system at the low level.

Metabolism:

Excretion:

Renal OCT2 substrate: all are not, so they may rely on other mechanisms for renal excretion or may be eliminated through non-renal pathways.

Total clearance: low rate (0.001) to moderate (0.2-0.3). Higher clearance (0.45) indicates faster elimination, but requiring more frequent dosing.

Toxicity:

No compounds show mutagenicity risk (AMES toxicity) or skin sensitization potential based on the model.

Protozoan bacterium Tetrahymena pyrofirmis: all compounds are predicted to be toxic (> -0.5).

Fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas): all compounds are predicted to be toxic to aquatic organisms (< -0.3), except 14 (0.021).

Maximum tolerated dose: moderately high (0-1). Higher values indicate lower toxicity.

Oral rat acute / chronic toxicity: relatively low toxicity.

Hepatotoxicity: 16 compounds are predicted to be potentially hepatotoxic.

hERG I and II inhibition: 21 compounds may inhibit the hERG potassium channel, increasing cardiac toxicity risk.

Based on the toxicity predictions [

21] in

Table S7b, compounds

19 and

18 appear to be the least toxic (sum scores of 1.221 and 1.764, respectively), followed closely by compounds

16,

26,

23, and

24 (scores 1.640 to 2.470). These compounds, particularly

18 and

19 with nitro groups, demonstrate an interesting paradox of improved safety profiles despite containing structural features typically associated with toxicity.

It's important to note that this analysis is based on predictive models and should be considered alongside other drug-like properties and experimental data. The actual safety and efficacy of these compounds would need to be confirmed through further in vitro and in vivo studies. Still, the safest compound may not necessarily be the most effective for a given therapeutic use. So, to facilitate the future research, the possible pharmaceutical forms based on the data are proposed:

Oral tablets or capsules: compounds with good intestinal absorption (> 90%) and Caco-2 permeability (> 1) are suitable for oral administration. Most compounds in the dataset fit this category.

Transdermal patches: compounds with good skin permeability (closer to 0) could be used in transdermal formulations. Compounds 1, 2, and 8 have the highest values.

Intravenous (IV) formulations: for example, compounds with higher water solubility like 3 (−4.200) and 4 (−4.965) may be more suitable for aqueous formulations, while highly lipophilic compounds like 16 (logP 7.03) might benefit from lipid-based delivery systems.

Central Nervous System (CNS) targeted drugs: compounds 7, 8, and 12 show the most favorable BBB permeability (over 0.2), while compounds like 18 and 19 with BBB values below -1.48 would be better suited for peripheral applications where CNS side effects should be avoided.

In summary, the data suggests many of these compounds may have favorable absorption, but limited distribution, especially into the brain and CNS. Further optimization may be needed to improve characteristics like solubility, BBB penetration, and interactions with transporters/metabolizing enzymes. Although compounds display favorable intestinal absorption, they may be subject to efflux transporter and CYP-mediated metabolic liabilities. Overall, these results highlight key pharmacokinetic issues that could impact efficacy and toxicity to prioritize for further evaluation and optimization of this chemical series.

3.1.6. Drug-Likeness via the pkCSM

Building on the pharmacokinetic analyses, we evaluated the drug-likeness profiles of all synthesized compounds using multiple established criteria (

Supplementary Material, Table S8a,b) to assess their potential as

viable drug candidates.

Physicochemical properties. The compounds exhibited a broad range of molecular weights (361.19-540.25 Da), with most satisfying Lipinski's limit of <500 Da. Notable exceptions included compounds

5 (540.25 Da),

16 (509.21 Da),

18 and

19 (520.16 Da), and

26 (532.22 Da), which slightly exceeded this threshold but remained below the more permissive ADMETLab 2.0 cutoff of 600 Da [

23]. Compounds contained between 45-75 atoms, with atom counts generally appropriate for membrane penetration and oral absorption. This size range suggests good potential for balancing potency with bioavailability.

Hydrogen-bonding capacity. All compounds satisfied Lipinski's criterion of ≤10 hydrogen bond acceptors. However, several compounds exceeded the preferred limit of ≤5 hydrogen bond donors, including 3-5, 13, 18, 19, 23, and 26. This hydrogen-bonding profile may enhance aqueous solubility for these compounds but could potentially limit passive membrane permeability.

Lipophilicity and polarity. LogP values ranged from 3.91 (20) to 7.03 (16), with most compounds exhibiting values around 5-6. Compounds 5, 6, 15, and 16 showed notably high lipophilicity (6-7), which may enhance membrane permeation but potentially compromise aqueous solubility. Topological polar surface areas ranged from 39.94 to 95.34 Ų, all below the critical threshold of 140 Ų. Lower values (<60 Ų) in compounds 1, 2, 7, 8, and others suggest enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration potential, while higher values in compounds 5, 18, and 19 indicate improved water solubility at the expense of membrane permeability.

Structural flexibility and complexity. Rotatable bond counts ranged from 8 to 16, with flexibility indices between 0.36 and 0.84. Compounds 15-19 had the highest rotatable bond counts (12-13), potentially increasing their conformational adaptability but possibly decreasing oral bioavailability. The presence of multiple ring systems (2-4 rings per molecule) provides structural rigidity, potentially enhancing target selectivity and metabolic stability while maintaining favorable drug-like characteristics.

Overall drug-likeness assessment. Based on analysis across multiple drug-likeness criteria (

Supplementary Material, Table S8b), compounds

20 and

22 demonstrated favorable drug-likeness profiles, while compound

21 exceeded the LogP threshold (5.24) and showed elevated rotatable bond counts. However, all three compounds exhibited poor biological activity across GPCR targets. Compounds

1,

2,

7, and

8 also demonstrated favorable profiles, with only slightly elevated LogP values. Importantly, our lead compound

26, despite its higher molecular weight, exhibited a well-balanced drug-likeness profile as visualized in the radar plot (

Figure 11,

Supplementary Material, Table S8c), with only water solubility (−5.88) falling outside the desirable range (−4 to 0.5) of ADMETLab 2.0 Soft Rules [

23].

Implications for therapeutic development. The observed drug-likeness patterns suggest several potential therapeutic applications and formulation strategies. Compounds with favorable oral absorption parameters (20, 22) would be suitable for convenient daily dosing regimens. Those with enhanced BBB permeability (7, 8, 1, 2) present opportunities for CNS-targeted therapies. Compounds with higher lipophilicity could be candidates for dermal or transdermal applications. The poor aqueous solubility observed in most compounds, particularly 26, indicates that advanced formulation strategies (such as lipid-based delivery systems, nanosuspensions, or solid dispersions) may be necessary to achieve optimal bioavailability. These structure-property relationships provide a foundation for rational selection of lead compounds for specific therapeutic applications. While drug-likeness criteria offer valuable guidance for prioritizing compounds, they must be considered alongside the previously established activity profiles, particularly the strong GPCR binding affinity observed for compound 26, which compensates for its slight deviations from ideal drug-likeness parameters.

This visualization reveals that compound 26 exhibits favorable properties across most parameters essential for drug development. Specifically, it shows appropriate values for molecular weight (532.22, within the 100-600 range), hydrogen bond donors (0, within 0-7 range), hydrogen bond acceptors (6, within 0-12 range), number of rings (4, within 0-6 range), atoms in the biggest ring (10, within 0-18 range), heteroatoms (8, within 1-15 range), formal charge (0, within -4 to 4 range), and rigid bonds (24, within 0-30 range).

The radar chart highlights two parameters requiring attention during future optimization: water solubility (logS = -5.88, below the preferred range of -4 to 0.5) and rotatable bonds (12, slightly exceeding the upper limit of 11). The poor water solubility suggests that formulation strategies such as salt formation, particle size reduction, or lipid-based delivery systems might be necessary for effective delivery of compound 26. The slightly elevated number of rotatable bonds may affect conformational stability but could also contribute to the observed binding versatility across multiple targets, particularly the strong affinity for CGRP1R. This balanced profile of physicochemical properties, despite minor deviations from ideal parameters, supports compound 26's potential as a viable candidate for further therapeutic development, particularly for conditions where limited CNS penetration would be beneficial.

Based on the these profiles, several promising therapeutic applications emerge:

Oral medications. Compounds 20-22, with their balanced physicochemical parameters, but limited biological activity, present excellent candidates for oral administration in chronic conditions requiring daily dosing. Their compliance with multiple drug-likeness rules suggests reduced risk of bioavailability issues.

Central nervous system (CNS) drugs. Compounds 1, 2, 7, and 8, characterized by lower TPSA values (39.94-39.94 Ų) and optimal LogP profiles (5.11-6.11), demonstrate enhanced blood-brain barrier penetration potential. These properties make them particularly promising for neurological or psychiatric conditions where CNS penetration is essential.

Dermal or transdermal applications. The highly lipophilic compounds 15 and 16 (LogP 6.63-7.03) could be advantageous for topical or transdermal formulations. Their structural features would facilitate skin penetration, making them suitable for localized pain management or hormone therapy applications.

Extended-release formulations. The compounds with lower water solubility, particularly 16 (LogS -6.62) and 19 (LogS -6.40), present opportunities for extended-release oral formulations. Their limited aqueous solubility could be leveraged to provide controlled drug release and longer-lasting therapeutic effects.

Targeted therapies. The diverse molecular architecture observed across the series, especially in compounds 26 and 3 with their complex ring systems, suggests potential for developing drugs with tissue-specific distribution profiles. This diversity could be exploited for targeted treatments, including cancer therapies or other conditions requiring precise tissue or cellular compartment targeting.

Metabolism-focused drugs. The range of structural features influencing metabolism, particularly in compounds with moderate clearance rates like 15 (0.446) and 19 (0.408), could be valuable for developing drugs that modulate metabolic processes or have predictable metabolic profiles.

3.4. Limitations

While this computational study provides valuable insights into the therapeutic potential of paclobutrazol derivatives, several limitations should be acknowledged, which simultaneously present opportunities for further investigation:

Computational modeling boundaries. The study relies exclusively on computational predictions without experimental validation. While our multi-faceted approach utilizing various complementary in silico tools strengthens confidence in the predictions, biological systems inherently possess complexities that computational models cannot fully capture. This limitation represents an immediate opportunity for targeted experimental studies focusing on the most promising compounds, particularly 26, to validate predicted activities and mechanisms.

Predictive model considerations. Each computational model employed has its own training dataset biases, algorithm limitations, and applicability domains:

The binding predictions indicate potential targets but do not differentiate between agonist, antagonist, or allosteric modulator activity.

Toxicity predictions may not fully capture complex biological interactions or metabolite toxicity.

Drug-likeness assessments have empirically derived cutoffs that may not be universally applicable across all therapeutic contexts.

Structural optimization potential. The current compound library, while diverse, represents only a subset of possible modifications to the paclobutrazol scaffold. Several compounds (18, 19, 26) displayed promising profiles but had minor deviations from ideal drug-like properties (particularly water solubility). This limitation presents a clear opportunity for structure-activity relationship optimization to improve pharmacokinetic properties while maintaining target binding.

Mechanism of action exploration. While sterol 14-alpha demethylase inhibition has been identified as a probable antifungal mechanism, the multi-target activities predicted for these compounds (particularly GPCR binding) require further mechanistic investigation. This creates opportunities for exploring novel therapeutic applications through detailed binding site analyses and functional studies.

Formulation considerations. The poor aqueous solubility predicted for several lead compounds (

15-

19,

26) represents a pharmaceutical development challenge. However, this limitation also presents opportunities to explore innovative drug delivery strategies, such as lipid-based formulations, nanosuspensions, or prodrug approaches, which could potentially enhance bioavailability while preserving therapeutic efficacy [

48].

All above-mentioned limitations, viewed collectively, provide a framework not only for acknowledging the boundaries of the current study but also for guiding the strategic direction of future research. By addressing these constraints systematically, subsequent studies can build upon the foundation established here to realize the full therapeutic potential of these paclobutrazol derivatives.

3.5. Integrative Assessment and Future Directions

This study establishes several significant contributions to drug discovery while providing a clear path for translating computational insights into therapeutic applications:

Methodological framework.

The integration of multiple computational approaches — spanning toxicity, target binding, pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness — provides a robust evaluation pipeline that compensates for individual model limitations. This framework can be applied to other agricultural compounds, potentially uncovering additional therapeutically valuable scaffolds that have been overlooked.

Strategic prioritization for experimental validation.

The computational analysis enables rational prioritization of compounds and targets for experimental validation, focusing resources on the most promising candidates:

Lead compound prioritization. Compound 26 emerges as the highest priority for antimicrobial and GPCR-targeting validation studies, followed by compounds 18 and 19 for their favorable safety profiles, and compounds 20-22 for their optimal drug-likeness properties.

Target validation strategy. Experimental validation should include both antimicrobial assays (focusing on ergosterol biosynthesis inhibition) and GPCR functional assays (particularly for CGRP1R and CaSR), to confirm the multi-target potential of these compounds.

Formulation development. For lead compounds with poor predicted water solubility, parallel formulation studies should be initiated to overcome this limitation while experimental efficacy validation proceeds.

Scaffold optimization approach.

Based on our structure-activity insights, further optimization of the paclobutrazol scaffold should focus on:

Preserving the naphthyl moiety of 26 while exploring modifications that might improve water solubility without disrupting the critical hydrophobic interactions.

Exploration of additional nitro-substituted derivatives based on the favorable safety profiles of compounds 18 and 19, with a focus on improving metabolic stability.

Investigation of alternative heterocyclic replacements for the triazole, building on the insights from compound 3 with its oxadiazole moiety.

Translational research opportunities.

The multi-target profile of these derivatives, particularly their affinity for CGRP1R, aligns with current trends in drug discovery toward polypharmacological approaches for complex diseases [

49]. The potential applications in migraine, calcium disorders, and fungal infections represent specific translational opportunities that deserve priority in subsequent research phases.

Agricultural-pharmaceutical bridge.

Perhaps most significantly, this study establishes a methodological bridge between agricultural chemistry and pharmaceutical development — two fields that have traditionally operated in separate domains despite working with bioactive compounds [

50]. This cross-disciplinary approach could revitalize drug discovery by leveraging the extensive chemical space of agricultural compounds that have already demonstrated biological activity and favorable safety profiles in environmental contexts (

Table 1).

This integrative summary highlights how strategic structural modifications can be leveraged to optimize specific properties while maintaining the core paclobutrazol scaffold, providing clear direction for future medicinal chemistry efforts.