1. Introduction

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) can be considered the precursors of cervical cancer and are almost exclusively caused by infections of high-risk types of the human papillomavirus (HPV). The method of excisional therapy has been proven effective in eliminating high-grade lesions of the cervix entirely but has also been observed to confer women an increased lifelong risk of recurrence of CIN2+, which can be attributable to the persistence of latent infection of high-risk HPV. Various large observational studies and meta-analyses have been used to provide supportive information regarding the role of adjuvant HPV vaccine therapy in the secondary reduction of the risk of recurrence of CIN2+ of the cervix by at least 60-70%. However, the post-CIN treatment acceptability of the HPV vaccine remains sub optimally low across the global context (1,2).

1.1. Adjuvant HPV Vaccination After Surgical Treatment for CIN2/3

HPV vaccination has recently proposed as an adjuvant prophylaxis strategy following surgical excision of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3) (3). Persistent or recurrent HPV infection remains the principal cause of post-treatment recurrence, with approximately 10–15% of women developing residual or new high-grade lesions despite adequate excision and negative surgical margins. Adjuvant vaccination enhances immune response, preventing from reinfection by vaccine-covered HPV types and potentially reducing viral persistence in latent sites (4,5).A growing body of evidence, including multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, demonstrates a 60–70% reduction in the risk of recurrent CIN2+ among women vaccinated perioperatively compared with unvaccinated controls. Sand et al. subsequent pooled analyses confirmed that vaccination—whether administered before or within one year after excision—significantly decreases the incidence of histologically confirmed recurrence, particularly for HPV-16/18–related lesions (2). These findings have led major professional societies, including ESGO, ASCCP, and CDC, to recognize adjuvant HPV vaccination for immunization as a promising adjunct to standard post-excisional surveillance in eligible women up to age 45.This reflects a shift toward secondary prevention, transforming the management of CIN from a purely surgical intervention to an integrated immunopreventive approach that addresses both eradication of existing disease and protection against future infection (6).

1.2. Challenges in Real-World Uptake After CIN Treatment

Although the existing data on adjuvanted HPV vaccination has been highly encouraging in preventing recurrence of high grede cervical lesions (CIN2+), it is astounding that scant few women actually receive this vaccination after treatment of CIN2/3. The lack of coverage achieved has been estimated variably, often <30-40% in regions with otherwise well-executed vaccination programs. The discrepancy between existing proof of concept and lack of practice does not indicate failure among efficacy trials, but lack of awareness, psychosocial engagement, or both. Many of these individuals consider vaccination following surgical removal of the lesion as redundant, as they often consider it an indication of complete cure of the disease. There also remains misconceptions among them concerning vaccine safety, fertility, or age indication.

From a healthcare perspective, there could be missed opportunities regarding vaccination counseling after treatment follow-up visits, which could be owing to the lack of physician recommendation, an established predictor of acceptance. Moreover, barriers from the psychosocial-informational domain all contribute jointly to undermine the effectiveness of an established intervention by which a significant recurrence of cancer could be averted. Taking into account the concerns, emotional states, and educational levels of women would thus be pivotal in exploring its complete preventive benefit by establishing a relationship of post-CIN care involving HPV vaccination.

Owing to the existing discrepancy between the findings of clinical research and implementation practices, comprehension of the ‘human factor’ of how HPV vaccination can be readily received by society has become a matter of relevance in public health. The group of interest, that is, women diagnosed with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), represents a specifically interested group of individuals exposed to heightened levels of psychological vulnerability, often facing anxiety, stigmatization, or the fear of disease recurrence. The findings of this research will be significant in understanding various attitudes of females concerning HPV vaccination after diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. What will follow represents a description of the issue of interest, its relevance, which will help frame the research question of this research. The current review will focus on synthesizing the existing knowledge on factors of attitudes of females concerning HPV vaccination after diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

Despite robust evidence that adjuvant HPV vaccination reduces CIN2+ recurrence by 60–70%, uptake remains low. Understanding post-treatment acceptance is therefore clinically essential.

2. Materials and Methods

The current review has been planned as an evidence-based narrative synthesis in accordance with SANRA quality criteria (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles). It does not constitute a systematic review. The overall objective of the present narrative comprehensive review has been to identify and critically analyze all existing evidence from 2010 to 2025 on women's views and acceptance of the HPV vaccine following treatment for CIN. The current narrative comprehensive review has used both quantitative as well as qualitative information to offer an overall perspective that considers clinical as well as system levels of determinant factors.

The literature search was carried out on the search engines of Pubmed, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science using the Boolean search terms: (“HPV vaccination” OR “human papillomavirus vaccine”) AND (“cervical intraepithelial neoplasia” OR “CIN” OR “cervical dysplasia”) AND (“acceptance” OR “attitude” OR “perception” OR “awareness” OR “knowledge” OR “determinant” OR “predictor”). The bibliographies of important guidelines and reviews from ESGO-EFC, WHO, and ACIP were also searched. For inclusion in the analysis, only peer-reviewed literature that had been published in the English language and included human subjects. The complete search strategy appears in Supplementary Table s1.

We included studies published between 2010 and 2025 that focused specifically on women diagnosed or previously treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and that reported at least one of the following: HPV vaccination acceptance, awareness, attitudes, perceptions, behavioural factors, or determinants influencing vaccination after CIN treatment. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were eligible. Only peer-reviewed articles in English were included.On the other hand we excluded studies that focused on the general population without CIN-specific data, studies that did not report outcomes related to post-CIN vaccination behaviour, conference abstracts without full text, commentaries, editorials, animal studies, duplicated datasets, and papers not written in English.

Trials were included that showed original data on HPV vaccine acceptance, awareness, and perceptual patterns in women who had been previously treated for CIN or cervical precancer. Studies were included if they reported at least one of: acceptance rates, determinants, awareness, risk perception, or post-treatment vaccination behaviours. These trials also had to have quantifiable outcomes like immunization rates, acceptance levels, and determinants. Studies that included general population trials without direct relevance to immunization acceptance post-CIN treatment, animal trials, abstract data from conventions and symposiums, commentary sections, and repeated data were excluded. The search included publications from January 2010 to March 2025. Two independent reviewers independently examined the titles and abstract sections of all records for the trial inclusion criteria and obtained the full text of potentially relevant trials. In both trials, the data collected included author's details, year of publication, country of research, size of trial population, nature of research design, trial population data, acceptance levels, determinants of immunization acceptance, and context of the trial.

Study Screening and Selection

All records identified through the database search were screened in two stages. First, two independent reviewers examined titles and abstracts to assess potential eligibility. Full texts were then obtained for all articles that met the initial criteria or where eligibility was uncertain. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion, and when necessary, a third senior reviewer was consulted to reach consensus. The final set of included studies was determined after full-text evaluation.

A total of 498 records were identified across all databases after removal of duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 117 articles were retrieved for full-text evaluation. Ultimately, 56 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the narrative synthesis. Of these, 34 were original research articles, and 22 were review-type articles, including systematic reviews, narrative reviews, guideline papers, or meta-analyses containing CIN-specific post-treatment HPV vaccination data.

Given the heterogeneity of designs within the included studies, it wasn’t possible to carry out meta-analysis. However, an assessment of the quality of research methodology on an adapted set of critical appraisal principles for observational and qualitative research has been carried out. This approach aimed at substantiating the current evidence level and didn’t eliminate the evidence of lower quality as it was foreseen by the principles of narrative synthesis.

For a cohesive analysis framework, the data were plotted on two intersecting axes. The first axis represented geographic divisions by continents: Europe, North America, Asia, Latin America, and Africa. The approach enabled analysis of acceptance rates in the context of local variations in acceptance of vaccines as well as healthcare infrastructure. The second axis represented types of determinants based on a structure adapted from the socioecological model. The socioecological model included four levels: individual, interpersonal, system, and societal. At the individual level were factors of age, education level, parity, existing knowledge of HPV infections, and beliefs on repeated infections. The interpersonal factor included physician influence, influence of partners/spouses, influence of family and friends, or peer influence. The system factors were cost of vaccines covered by healthcare services, vaccines accessible at healthcare centers, reminder services for HPV vaccinations, and easy access to subsequent care. At the societal level were factors of stigma against HPV-related infections in society due to ignorance and stigma. The structure enabled two-way analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data.

The findings were presented in the form of tables and figures. The acceptance levels in the regions, determinants of immunization, as well as the reduction of recurrence by adjuvant immunization post CIN treatment were presented. The quantitative findings from larger trials such as the SPERANZA project and the Danish nationwide prospective cohort were synthesized with qualitative findings on awareness levels, attitudes, and implementation challenges. Inconsistencies were examined with respect to healthcare system types and acceptance of the disease.

All information used for writing the critique has been obtained from existing research literature. No new data has been collected. The article therefore did not require an ethical consideration since it carried out neither human nor animal participant research.

Table S1.

Full Search Strategy for the Narrative Review.

Table S1.

Full Search Strategy for the Narrative Review.

| Database |

Full Search String (as executed) |

Date Last Searched |

Filters Applied |

Notes |

| PubMed |

(“human papillomavirus vaccine”[Mesh] OR “HPV vaccination” OR “HPV vaccine”) AND (“cervical intraepithelial neoplasia” OR CIN OR “cervical dysplasia” OR “cervical precancer”) AND (acceptance OR attitude OR perception OR awareness OR knowledge OR “vaccine hesitancy” OR determinant OR predictor) |

10 March 2025 |

• Humans • English • 2010–2025 |

Complete PubMed string required by Reviewer 1 |

| Scopus |

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“HPV vaccination” OR “human papillomavirus vaccine”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“cervical intraepithelial neoplasia” OR CIN OR “cervical dysplasia”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (acceptance OR attitude OR awareness OR perception OR determinant OR predictor) |

10 March 2025 |

• English • Article/Review • 2010–2025 |

Exported references manually checked for duplicates |

| Embase |

(‘human papillomavirus vaccine’/exp OR ‘HPV vaccination’ OR ‘quadrivalent vaccine’ OR ‘9-valent vaccine’) AND (‘cervical intraepithelial neoplasia’/exp OR CIN OR ‘cervical dysplasia’) AND (acceptance OR attitude OR perception OR ‘vaccine hesitancy’ OR awareness OR ‘decision-making’) |

11 March 2025 |

• Human studies • English • 2010–2025 |

Emtree terms adapted from previous HPV systematic reviews |

| Web of Science |

TS=(“HPV vaccination” OR “human papillomavirus vaccine”) AND TS=(“cervical intraepithelial neoplasia” OR CIN OR “cervical dysplasia”) AND TS=(acceptance OR perception OR attitude OR awareness OR determinant OR predictor) |

11 March 2025 |

• Web of Science Core Collection • English • 2010–2025 |

Citation tracking performed manually |

| Additional Sources |

— |

— |

• ESGO-EFC Guidelines • WHO HPV Technical Reports • ACIP/CDC Position Statements |

Hand-searching of reference lists of all included papers |

3. Results

3.1. HPV Vaccination and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Although HPV prophylactic vaccination was conceived as a tool of primary infection prevention, an increasing body of evidence shows its effectiveness in secondary infection prevention after cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) treatment. From a biologic perspective, this strategy relies on the immune memory induction able to effectively neutralize HPV viral particles, thus preventing readminstration of oncogenic types covered by the vaccine. The vaccination could also increase local surveillance of the cervical transformation zone, thus preventing viral persistence.

It is known in fact that, after an effective cervical intraepithelial lesion removal, women still retain a high risk of acquiring cervical carcinoma throughout their entire life [

1,

2,

4].

The effectiveness of adjuvant HPV vaccination after CIN2+ has been demonstrated by a number of randomized controlled trials and cohort studies. Meta-analyses of more than 20,000 CIN2/3-treated patients show a 60-70% reduced recurrence risk in the vaccinated group versus controls.

This estimate derives from previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses, not from the present narrative review. The meta-analysis by Di Donato et al. (Vaccines 2021) included 11 individual studies, while the Danish nationwide pooled analyses evaluated several large population-based cohorts. Together, these published analyses encompass more than 20,000 women treated for CIN2/3, which is the evidence base behind the commonly cited 60–70% reduction in recurrence.

Various clinical trials, including VIVIANE, FUTURE I/ II, PATRICIA, and data collected from follow-up cohorts of vaccinated populations in Italy, Denmark, as well as Australia, prove that immunization pre- or post-excisions effectively lowers the occurrence of a follow-up incident of CIN2+. The vaccination efficacy has also been proven by follow-up analyses of more than a decade after immunization [

1,

2].

Across the analyzed literature, adjuvant HPV vaccination following excisional treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) was consistently associated with a marked reduction in disease recurrence. In the Italian SPERANZA prospective study, Ghelardi et al. observed a 60% decrease in CIN2+ recurrence among women vaccinated within twelve months after conization compared with unvaccinated controls (recurrence rates 1.7% vs. 4.3%) [

13]. The Danish nationwide cohort of over 17,000 women reported by Sand et al. demonstrated a 45% lower risk of histologically confirmed CIN2+ recurrence following post-treatment vaccination, adjusted hazard ratio = 0.55 (95% CI 0.42–0.73) [

3]. Similar findings were supported by the meta-analysis of Di Donato et al. (2021), which pooled more than 20,000 treated patients and confirmed a relative risk reduction of approximately 65% for recurrent high-grade lesions in vaccinated versus unvaccinated women [

14]. Smaller prospective cohorts, including the German study by Jentschke et al. and the Korean trial by Kang et al., reinforced these outcomes, reporting recurrence reductions ranging between 50–70% [

15,

16]. Collectively, these results strengthen the hypothesis that vaccination after surgical treatment provides an effective secondary-prevention benefit beyond primary immunization, particularly against HPV-16/18-related lesions.

3.2. Current Guidelines' Recommendations

Taking into consideration this evidence base, current guidelines from leading gynecologic oncologic societies, including the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO), the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), as well as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), recommend HPV vaccination in women post-CIN2/3 treatment up until age 45 years. The ESGO consensus statement firmly advocates the role of adjuvant vaccination after cervical surgery on the premise of established efficacy and safety. The guidelines recommend co-administration of vaccination within the first year after cervical surgery [

3].

3.3. Implementation and Patient Acceptance

Although there is strong clinical evidence supporting the use of adjuvant vaccination, its application on a broader level still requires improvement. The key implementing factor in this process is the acceptance of the preventive measure by the patients. Many females find surgical removal of lesions curative. Also, there is less awareness of the risks of reoccurrence. Clinicians' efforts, along with proper information of the population, can thus become definitive steps in implementing this preventive measure.

3.4. Knowledge and Awareness Among Women with CIN

Even after decades of public education regarding this disease issue, there is still a lack of awareness of the etiological relationship of human papilloma virus (HPV) infection with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Many females with abnormal Pap tests or newly identified CIN do not understand that the HPV is the etiological factor leading to cervical dysplasias as well as the development of cervical carcinoma [

4]. The lack of awareness can sometimes produce questions among individuals regarding the justification of vaccination against HPV following treatment. Common misconceptions continue among various groups. Some women feel that HPV vaccination is unnecessary after infection or the onset of CIN, as it is only beneficial as a preventive measure given to adolescents or unexposed females. Some others raise unjustified concerns that the vaccine could affect fertility, menstrual cycles, or induce an autoimmune disease. This is encouraged by misinterpretations on the internet. There are also females who consider HPV vaccination a treatment of the infection itself. This confuses realistic expectations from vaccination [

4].

The level of awareness and knowledge is strongly related to the level of education, screening participation, and socioeconomic status. Educated women with regular participation in the cervical screening program show higher levels of awareness for HPV transmission, vaccination efficacy, and recurrence rates. Lack of health literacy, financial conditions, as well as lack of access to preventive services, has been consistently found to be associated with poor awareness despite clear susceptibility to misconceptions. There remains an identified need for efforts focused on education across gaps in the these groups. [

4,

5]

The role of the explanation by the clinician as well as the time of communicating this information plays an important role in building the level of comprehension as well as decision-making on the part of the patients. Evidence shows that personalized explanations provided during colposcopy or follow-up visits after biopsy can considerably raise acceptance of vaccination, especially if it is framed by physicians not as an additional measure, but as an inherent step of recovery [

5]. Regional variation in awareness Geographic and cultural variations also affect the levels of awareness as it is shown on

Table 1. Results from Northern and Western Europe show a higher level of awareness of the role of HPV in cervical disease, while Southern and Eastern Europe demonstrate less awareness of HPV and more myths. Awareness of both HPV and its vaccination in Asian countries has been inconsistent, with good levels in urban and educated communities but a lack of awareness in rural areas owing to various stigmas, lack of accessibility, and distorted information channels in the healthcare settings [

5,

6,

7].

3.5. Attitudes, Beliefs, and Emotional Factors

The diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) can cause significant emotional distress, including anxiety, guilt, or shame, mainly attributed to its association with an STI. Also, the diagnosis can be considered not only a medical issue but also a reflection of an individual’s behaviour by many females. This can be attributed to the stigma of HPV infection, which can be worsened by an inadequate explanation of the association of HPV with cervical carcinoma by practitioners, thus making it difficult for individuals to feel comfortable with medical interventions like vaccination [

6].

Such emotional responses are of key importance in the determination of risk perceptions as well as the willingness of an individual to take preventive measures. Female patients feeling fear or apprehension regarding the possibility of reoccurrence of diseases will or will not take the vaccination on account of denial or could do the opposite, which is take the vaccination as a means of reclaiming their autonomy. Research shows that the concept of vaccination as an enabling act of claiming autonomy in protecting oneself from disease, and not as an indication of having been exposed, enhances emotional acceptance or openness [

6,

7].

Trust in healthcare professionals and institutions is found repeatedly as a key factor in accepting vaccination. For women, belief in their gynecologist, colposcopist, or the national health authorities is significant in accepting HPV vaccination [

7]. Clear communication, care coordination, and endorsement by reputable organizations can help alleviate doubts created by myths. Perceived lack of clarity, rapid consultation visits, or lack of follow-up care contribute to skepticism among those carrying an emotional toll of diagnosis.

Various qualitative research among differing populations identifies some common themes encompassing the emotional experience of females post-CIN treatment as follows: “I wish I'd known earlier", "Fear of recurrence”, “Concerns about side effects”, “Concerns about it potentially being too late for vaccination".

The afore-mentioned quotes depict the true essence of regret, hope, and fear of patients. The concerns can easily be countered by directly dealing with them through counselling.Cultural practices, as well as dynamics of the family, also influence vaccination choices. For example, in more collectivist cultures, acceptance of vaccination can be conditional on approval or influence of spouses or the family, while in more individualist societies, autonomy or freedom of choice will be considered. The attitudes of one’s spouse concerning vaccination, attitudes of society concerning sexual health, or religious convictions can be the driving or inhibiting force. Recognizing the culture’s framework can help the practitioner adapt strategies in giving precepts on HPV vaccination by embedding it into the sociocultural environment of the vaccinated individual [

6,

7].

4. Discussion

The persistent infections by oncogenic HPV types such as HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 represent the prime underlying causal factor for cervical carcinogenesis. These types account for 90% of global cervical cancer cases altogether. HPV 16 and 18 alone accounts for almost 70% of the aggressive types. However, the low-risk types 6 and 11 were found to account for the majority of genital warts [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. CIN stands for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. These lesions represent a continuum of precursor lesions that include epithelial immaturity and varied nuclear atypias. Based on the 2012 Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology (LAST), CIN 2 and CIN 3 lesions represent high-grade squamous lesions of the epithelia confirmed by positive immunostaining for p16. These lesions imply high-grade infections that transform and pose a high malignant potential [

18].

Infection lasting above 12 months poses a substantial potential for aggressive CIN 3 lesions. The biological imperative of prevention both at the levels of infection as well as reinfection thus stands amplified.

4.1. Pathogenesis and Prevention Integration

The continuum of HPV infection to Invasive Carcinoma offers an ideal rationale for an adjuvant approach to vaccines. Viral integration leads to disrupting theE2 regulatory elements with an attendant, uncontrolled expression of oncogenesE6/E7 that degrade proteins p53 and Retinoblastoma proteins that promote genomic instability [58]. The persistent viral epithelial lesions also maintain the low-grade lesions, and subsequent reinfection of the regeneration transformation zone in an excised lesion may initiate additional foci of dysplasia. this cycle by preventing new infections and reinfections with OPV-types of HPV [59].

Thus, post-treatment immunization does not merely complement excisional therapy—it biologically closes the causal loop of HPV-driven carcinogenesis. This integration of molecular pathogenesis with preventive intervention epitomizes precision public health.

4.2. Factors That Influence Vaccination Acceptance and Adherence

Whether or not to vaccinate against HPV post-operatively for CIN treatment remains an intricate process involving various factors. Informed mainly by psychographic factors such as increased age and lower educational attainment as negative determinants of acceptance, given better understanding of overall healthcare concepts and familiarity with gynecologists' practice [

8,

19,

20,

33]. In contrast, reduced immunization levels have been found in the elderly population that may have difficulties gaining access to healthcare services due to geographical or socio-economic circumstances. The underlying healthcare infrastructure of cost effectiveness and implementation within an existing schedule of care has been found to influence adherence [

46,

47].

Financial issues are also important. The presence of government-supported immunization programs or those covered by insurance shows a much higher rate of completers than those that require the patient to pay on his/her own. Adding HPV immunization codes within existing surgical and follow-up billing protocols effectively shifts it from an elective preventive treatment to becoming a new standard of care as should be expected. Inclusion of reminder notices via automatic notifications on the patient's electronic medical records or simply via text notices has already increased compliance by 20 to 40%, thus sustaining that it needs more than providing knowledge alone – it needs facilitation [

46,

50]. By the addition of immunization as the last step of recovery as being optional preventive treatment outcomes remain much better.

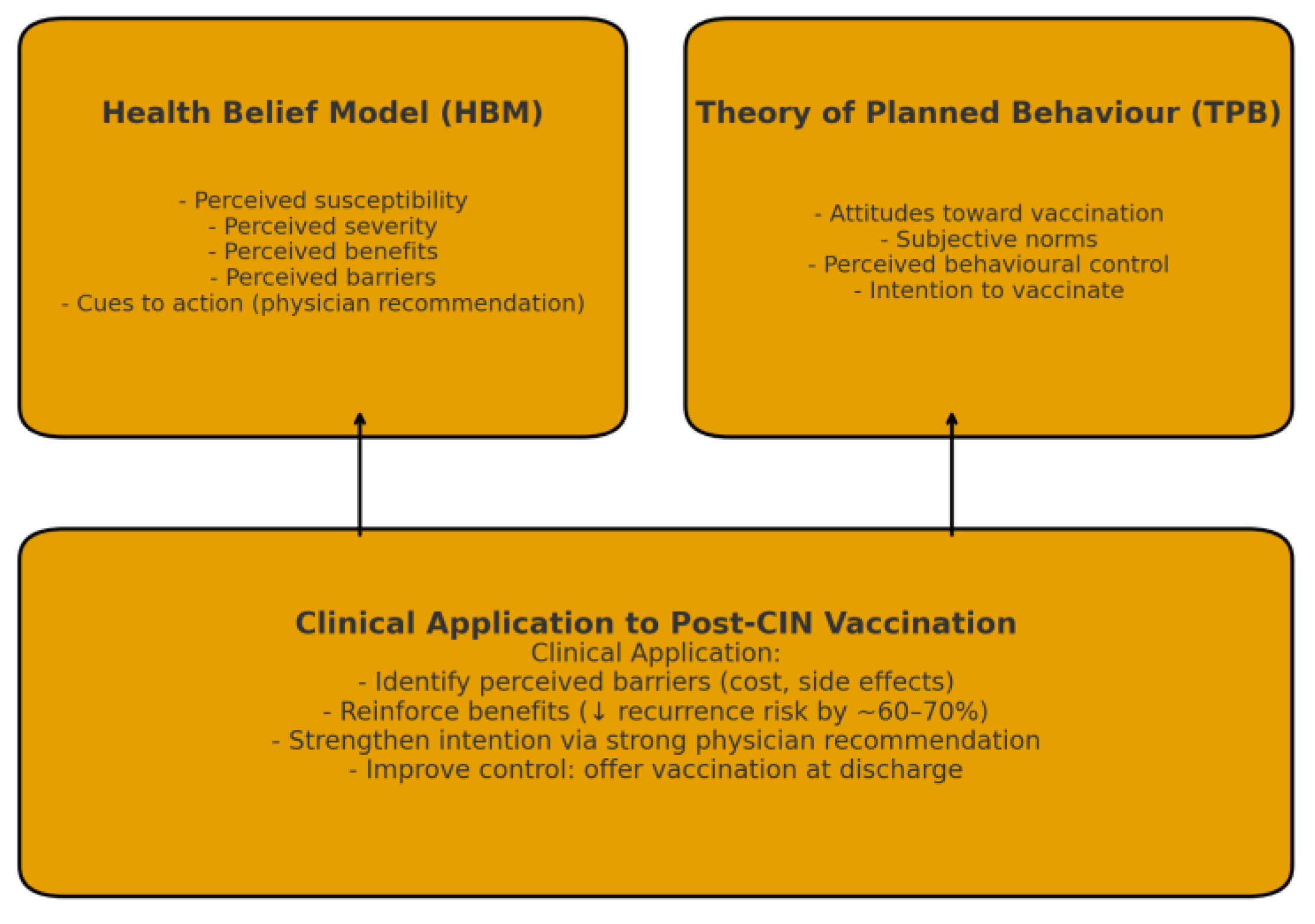

4.3. Behavioural Models and Predictors of Acceptance

Immunization choice following CIN treatment can be explained by using Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behaviour theories [

31,

32]. As mentioned in Health Belief Model theory, personal perceptions of disease susceptibility and benefits of immunization as well as cues such as practitioner recommendations serve as stimulants for preventive actions [

33]. As applied to TPB theories, behavioural intention emerges only on basis of attitudes toward immunization and internalization beliefs of an individual's control self-control over immunization manipulation [

23,

24,

25,

26,

34,

35]. In as much as these women comprehend that persistent HPV infections may recur due to latent viral reservoirs within the transformation zone of the cervix umbrella of cervical mucosa, their preventive strategy to immunization increases [

36,

37,

38,

39].

The persistent HPV infection leads to integration of the viral DNA into the host's basal keratinocytes. This expression produces two proteins, E6 and E7. These proteins act by inactivating tumor suppressor proteins p53 and Rb, respectively [

38]. These scientific facts highlight the important role of immunization post-therapy. The objective of immunization here is not the treatment of existing lesions but the prevention of reinfection of a biological area that has already been primed for malignant change. The tertiary preventive approach here is provided by the HPV vaccine.

The practical implementation of these frameworks of behaviour makes it possible to create personalized strategies of counselling. For women who have high perceived barriers of vaccines being expensive or having side effects, healthcare providers should highlight the high safety records of vaccines administered to hundreds of thousands of women worldwide [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. For those who have high perceived benefits but low levels of self-efficiency, healthcare providers may have to offer them logistical assistance such as immunization during discharge [

Figure 1].

4.4. Digital Health and Dynamics of Misinformation

The digital information environment has a dramatic influence on attitudes toward healthcare. Social networking sites such as Facebook and online fora have proliferated misinformation on HPV vaccines, often perpetuating myths of infertility, autoimmune disease, or sexual disinhibition as adverse consequences of such immunization [

27,

28,

29,

47,

48]. In contrast to the negative influence of online misinformation discussed above, online physician-led support groups and online healthcare-related websites increase trust levels in vaccines.

Findings of durable immunity following a single-dose regimen exist mostly through several landmark studies. The KEN SHE trial has proven the efficacy of single-dose HPV in protecting against new infections in Kenyan adolescents and young women. Studies in Costa Rica and India spearheaded by PATH also showed the strength of the immune response through the detection of antibodies up to 10 years post-immunization (46-49). Evidence from the Rwandan national single-dose study also supports the sustained immunogenicity of the vaccine and its high effectiveness at the community level. Model-driven research studies, as presented in Brisson et al. in 2022, showed the possibility of maintaining the protective effect of the vaccine beyond two decades through single-dose regimens. Evidence from the VIVIANE trial and the Joura trial also affirms the persistence of the neutralizing antibody level even through reduced dosages (50).

4.5. Physician Endorsement and Professional Responsibility

Among all factors influencing HPV vaccine acceptance, the endorsement of a physician's role ranks supreme [

26,

27]. In gynaecologic oncology, the physician's role as a healthcare provider as well as an educator holds irreplaceable value. The physician's strong indication of HPV immunization in the context of treatment completion significantly boosts acceptance. Lack of a strong indication triples the odds of refusal [

25,

27].

This emphasizes the importance of the professional ethics of providing a balanced perspective. Standardized immunization cues integrated into an electronic medical record system encourages uniformity. In addition, immunization discussions based on ESGO and ASCCP recommendations of immunization until age 45 and optimally within 12 months post-excisions establish immunization recommendations within evidence-derived guidelines [

19,

21,

22]. Continuing educational training on colposcopists and oncologists includes communication framework, shared decision-making, and cultural competence.

4.6. Health-System Integration and Cost-Effect

Addition of HPV immunization to existing prevention strategies for cervical cancer can improve both efficiency and long-term effectiveness. Cost-effective models have found that the addition of HPV testing to immunization during colposcopy visits or post-excisions has an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of less than USD 15,000 per QALY within high-resource regions [

9,

10]. These approaches offer both prevention of recurrence and prevention of new infections at the same time.

The WHO position paper of 2022 supporting single-dose immunization regimes marks the dawn of a new approach to implementation on a global scale [

1,

23,

45]. The latest UpToDate analysis supports that two- and single-dose immunization regimes retain immunogenicity at least comparable to a three-dose regime while offering substantial economic advantage by saving costs of implementation on a bigger scale [

49].

From a policy perspective, mechanisms of reimbursement and bundled payments should favour integration. Public-private collaborations involving the relevant ministries of health, manufacturing companies, and professional organizations may provide for subsidized value chains, especially for tertiary hospitals in resource-poor settings [

46,

47].

4.7. Barriers and Facilitators

Despite substantial evidence supporting adjuvant HPV vaccination, real-world uptake remains suboptimal. Common barriers include limited awareness, fear of side effects, distrust toward pharmaceutical industries, and misconceptions that surgery alone guarantees cure [

24,

25]. Structural obstacles—fragmented care pathways, limited vaccine availability, and lack of provider recommendation—further compound the issue [

37,

38].

Conversely, facilitators are clear: strong physician endorsement, culturally sensitive counselling, and logistical convenience. Studies demonstrate that offering vaccination on-site in colposcopy or oncology clinics doubles completion rates compared to external referrals [

24,

51]. Embedding prompts within national cervical cancer registries could institutionalize this “same-day, same-site” model. Emotional reassurance also plays a crucial role; women who perceive vaccination as empowerment against recurrence show higher adherence [

39,

40].

International experience illustrates the dynamic role of coordination. The comprehensive nationwide program involving schools and opportunistic catch-up and screening of girls and women in Australia led to the near eradication of high-grade cervical precancer lesions within 15 years [

10,

41,

42]. The decrease in HPV and CIN3+ in Scandinavia supports that population-level benefits can only be gained by comprehensive efforts at integration.

4.8. Ethical and Psychosocial Aspects

The principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice form the backbone of immunization. Healthcare providers should thus respect the principle of autonomy by being transparent about the risks and benefits. It should be noted that HPV immunization prevents reinfection or reduces the incidence of recurrence but has not been used as a treatment for existing HPV disease [59].

Psychosocially, post-CIN women often experience anxiety, guilt, or fear regarding reproductive potential and sexual relationships. Qualitative studies reveal that supportive counseling mitigates distress and enhances perceived control [

39,

40]. Cultural sensitivity is crucial—while autonomy predominates in individualist societies, spousal or familial endorsement may be decisive in collectivist settings. Tailoring counseling to local sociocultural context, using culturally adapted leaflets or survivor testimonials, improves acceptability. Reframing HPV vaccination as reproductive health promotion rather than an STI intervention helps destigmatize the topic and normalizes uptake [

6,

7,

41].

The healthcare providers also have moral considerations at the community level. Vaccination supports the concept of justice by providing an equal opportunity to avoid HPV-related cancers. The main objective of immunization targets the prevention of cervical cancer. The cervical cancer disease still poses a high mortality rate in resource-poor nations.

4.9. Future Directions and Research Gaps

Although observational data provide strong evidence that CIN2+ lesions recur less often post-vaccination, randomized controlled trials have been scarce. In future trials, it would be helpful to see outcomes differentiated by HPV types, age groups, and types of vaccines used. In addition, psychosocial outcomes such as decreased anxiety levels, improved body images, and overall quality of life should also be separately assessed.

Future studies seeking to tease apart the differences of vaccine efficacy according to HPV genotype will be challenged by the following substantive issues. Firstly, the number of non-16/18 high-risk HPV types will be exceedingly low in the context of the vaccine pool, rendering it impractical to detect recurrence according to genotype. In particular, the effectiveness of existing vaccines will cloud the ability to identify the role of a specific genotype. Additionally, the vast majority of existing information regarding recurrence of CIN2+ will be insufficiently sized to represent the rarity of genotypes represented by HPV 31, 33, and/or 52. Lastly, genotype recurrence databases and uniform molecular testing will be needed to properly measure the effect of the vaccine according to HPV type.

International standardization of the vaccination policy post-treatment is a prerequisite. Currently, both ESGO and EFC guidelines advocate CIN2/3 treatment-related vaccinations for women preferably within 12 months of excision, whereas the WHO and ACIP include women up to 45 years of age [

19,

21,

22]. The creation of global registries addressing recurrence rates, fertility outcomes, and survival rates would thus provide comprehensive data for these recommendations.

Finally, the implementation of artificial intelligence-driven reminder services, digital immunization registries, and monitoring dashboard services may ensure smooth implementation with high coverage. The long-term objective of such screening efforts goes beyond the prevention of lesion recurrence. Rather, it aims at the eventual prevention of cervical cancer as a public health problem. This milestone can only be realized through equitable immunization strategies.

5. Conclusions

HPV vaccination in the context of treatment of CIN2+ lesions through excision provides important secondary prevention against recurrence of the high-grade lesions. However, there has been marked variance in its acceptance, and this has been driven by various factors at the level of the individual against the backdrop of awareness to system-level factors of access. This narrative review draws particular attention to the impact of physician support being the chief facilitating factor as opposed to misinformation and cost being the chief hurdles.

The following topics should be explored in future research: (1) Risk of recurrence according to HPV type, (2) Comparative effectiveness of one versus two doses of vaccine in women who had received previous therapy, (3) Efficacy of electronic tools in correcting misinformation that hinders the decision-making process, and (4) Implementation strategies targeted at less resource-rich settings to eliminate inequities in the distribution of the vaccine. The above-mentioned research will be crucial in the quest to achieve the global target of cervical cancer elimination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L. and P.P.; methodology, V.L. and R.P.; validation, V.L., V.P. and P.P.; formal analysis, V.L. and R.P.; investigation, R.P., S.S., and C.C.; resources, E.S.B. and S.S.; data curation, R.P. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, V.L. and R.P.; writing—review and editing, V.L., V.P., and P.P.; visualization, E.S.B.; supervision, V.L. and P.P.; project administration, V.L.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it did not involve the collection of new data from human participants or animals. The present article is an evidence-based narrative review that synthesized and analyzed previously published studies available in the public domain. Therefore, no ethical approval was required in accordance with institutional and international guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. The study did not involve humans or animals, as it was based solely on previously published data and literature available in the public domain. Therefore, informed consent was not required. Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the First Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “Alexandra” Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and the Third Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University General Hospital “Attikon”, for their academic support and clinical environment that fostered this research. The authors also acknowledge the contribution of the ESGO–EFC guideline framework, which provided valuable context for the interpretation of evidence on HPV vaccination after CIN treatment. Editorial assistance and language review were provided internally without external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- World Health Organization. Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: WHO Position Paper, December 2022. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2022, 97, 645-672.

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, É.; Pérez, N.; Brisson, M.; et al. Population-Level Impact and Herd Effects Following the Introduction of HPV Vaccination Programs: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 497-509. [CrossRef]

- Sand, F.L.; Kjaer, S.K.; Frederiksen, K.; Dehlendorff, C. Risk of CIN2+ Recurrence after Conization and Adjuvant HPV Vaccination: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. BMJ 2020, 371, m3721.

- Cibula, D.; Kyrgiou, M.; Bosse, T.; et al. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO)-European Federation for Colposcopy (EFC) Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Prevention. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 944-959.

- Garland, S.M.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; Wheeler, C.M.; et al. Quadrivalent Vaccine against Human Papillomavirus to Prevent Anogenital Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1928-1943. [CrossRef]

- Joura, E.A.; Giuliano, A.R.; Iversen, O.E.; et al. A 9-Valent HPV Vaccine against Infection and Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 711-723. [CrossRef]

- Paavonen, J.; Naud, P.; Salmerón, J.; et al. Efficacy of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-Adjuvanted Vaccine against Cervical Infection and Precancer Caused by Oncogenic HPV Types (PATRICIA Trial). Lancet 2009, 374, 301-314. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, M.H.; Baron, M.; Levin, M.J.; et al. Comparative Immunogenicity and Safety of Cervarix and Gardasil HPV Vaccines in Healthy Women Aged 18-45 Years. Hum. Vaccin. 2009, 5, 705-719. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Goldie, S.J. Health and Economic Implications of HPV Vaccination in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 821-832. [CrossRef]

- Kusters, J.M.A.; Bogaards, J.A.; Berkhof, J.; et al. HPV Prevalence Changes during 12 Years of Girls-Only Vaccination in the Netherlands. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 231, e165-e173.

- Brotherton, J.M.L.; Fridman, M.; May, C.L.; Chappell, G.; Saville, M. Early Effect of the HPV Vaccination Programme on Cervical Abnormalities in Victoria, Australia: An Ecological Study. Lancet 2011, 377, 2085-2092. [CrossRef]

- Crowe, E.; Pandeya, N.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; et al. Effectiveness of Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine for the Prevention of Cervical Abnormalities: Case-Control Study Nested within a Population Screening Program. BMJ 2014, 348, g1458. [CrossRef]

- Ghelardi, A.; Parazzini, F.; Martella, F.; et al. SPERANZA Project: HPV Vaccine after Treatment for CIN2+: Reduced Recurrence Rate. Vaccines 2021, 9, 562.

- Di Donato, V.; Caruso, G.; Petrillo, M.; et al. Adjuvant HPV Vaccination to Prevent Recurrent Disease after Surgical Treatment for Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 410.

- Jentschke, M.; Kampers, J.; Becker, J.; et al. Prophylactic HPV Vaccination after LLETZ Reduces Recurrent CIN2+ Disease: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2102.

- Kang, W.D.; Kim, C.H.; Cho, M.K.; Kim, J.W.; Park, S.J. Preventive Role of HPV Vaccination after Conization in Korean Women: A Prospective Study. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2013, 56, 453-459.

- Kocken, M.; Helmerhorst, T.J.M.; Berkhof, J.; et al. Risk of Residual or Recurrent CIN after Excision: Population-Based Study. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 132, 211-218.

- Soutter, W.P.; Sasieni, P.; Panoskaltsis, T. Long-Term Risk of Cervical Cancer after Treatment for CIN: A Population-Based Study. BMJ 2020, 340, c345.

- Joura, E.A.; Kyrgiou, M.; Bosch, F.X.; et al. ESGO-EFC Position Paper on HPV Vaccination in Women Treated for Precancerous Lesions. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 116, 21-29.

- Meites, E.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Chesson, H.W.; et al. HPV Vaccination for Adults: Updated ACIP Recommendations. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 698-702.

- Petrosky, E.; Bocchini, J.A.; Hariri, S.; et al. Use of 9-Valent HPV Vaccine: Updated ACIP Recommendations. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 300-304.

- Castle, P.E.; Schmeler, K.M. HPV Vaccination: For Women of All Ages? Lancet 2014, 384, 2178-2179. [CrossRef]

- Hanley, S.J.B.; Yoshioka, E.; Ito, Y.; et al. Acceptance of HPV Vaccination among Women Treated for CIN: A Cross-Sectional Japanese Study. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1358-1365.

- Paolino, M.E.; Arrossi, S. HPV Vaccination in Women with Prior CIN: Missed Opportunities in Latin America. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1543.

- Niccolai, L.M.; Hansen, C.E. Practice- and Community-Based Interventions to Increase HPV Vaccine Coverage: A Systematic Review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2015, 11, 2503-2518.

- Lu, P.J.; Yankey, D.; Fredua, B.; et al. Association of Provider Recommendation with HPV Vaccine Initiation among Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2019, 206, 33-40.

- Ylitalo, K.R.; Lee, H.; Mehta, N.K. Health Care Provider Recommendation and HPV Vaccination by Race/Ethnicity. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 164-169.

- Adjei Boakye, E.; Tobo, B.B.; Rojek, R.P.; et al. Trends in Reasons for HPV Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States, 2010-2020. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022058896.

- Quinlan, J.D. Human Papillomavirus: Screening, Testing, and Prevention. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 152-160.

- Patel, C.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; et al. Australia's HPV Vaccination Program: Successes and Ongoing Challenges. Sex. Health 2018, 15, 483-491.

- Brewer, N.T.; Fazekas, K.I. Predictors of HPV Vaccine Acceptability: A Theory-Informed, Evidence-Based Review. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.Y.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Yankey, D.; et al. HPV Vaccination Coverage among Adolescents, United States, 2017. MMWR 2018, 67, 874-882.

- Chen, M.M.; Scott, S.; Chang, M.; et al. Sociodemographic Correlates of HPV Vaccination among Young Adults in the U.S. JAMA 2021, 325, 1673-1675.

- Bednarczyk, R.A.; Davis, R.; Ault, K.; Orenstein, W.; Omer, S.B. Sexual Activity-Related Outcomes after HPV Vaccination of Adolescents. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 798-805.

- Smith, L.M.; Kaufman, J.S.; Strumpf, E.C.; et al. Effect of HPV Vaccination on Sexual Behaviour among Adolescent Girls. CMAJ 2015, 187, E74-E81.

- Marlow, L.A.; Waller, J.; Evans, R.E.; Wardle, J. Predictors of Interest in HPV Vaccination among Adolescent Females and Their Mothers in the UK. Vaccine 2009, 27, 165-172.

- Msyamboza, K.P.; Mwagomba, B.M.F.; Valle, M.; et al. HPV Vaccine Acceptance and Willingness among Women in Malawi. Vaccine 2020, 38, 3621-3628.

- Makwe, C.C.; Anorlu, R.I. HPV Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Nigerian Women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 41, 1139-1144.

- Lenehan, J.G.; O'Brien, M.E.; Kingston, M.A. Stigma, Shame, and HPV: A Qualitative Exploration. J. Psychosoc. Oncol.2019, 37, 627-640.

- Daley, E.M.; Vamos, C.A.; Buhi, E.R.; et al. Influences on HPV Vaccine Decision-Making among Women Treated for CIN. Women Health 2018, 58, 819-834.

- Read, T.R.; Hocking, J.S.; Chen, M.Y.; Donovan, B.; Fairley, C.K. Near Disappearance of Genital Warts in Young Australian Women following the National HPV Vaccination Program. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2011, 87, 544-547.

- Donovan, B.; Franklin, N.; Guy, R.J.; et al. Quadrivalent HPV Vaccination and the Decline in Genital Warts in Australia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 39-44.

- Elfström, K.M.; Arnheim-Dahlström, L.; von Karsa, L.; Dillner, J. Cervical Cancer Screening Policies in the Era of HPV Vaccination: European Perspectives. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 199-207.

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Graubard, B.I.; Broutian, T.; et al. Effect of Prophylactic HPV Vaccination on Oral HPV Infections among Young Adults. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 262-267.

- Moreira, E.D., Jr.; Block, S.L.; Ferris, D.; et al. Safety Profile of the 9-Valent HPV Vaccine: Pooled Analysis of 7 Phase III Trials. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20154387.

- Hviid, A.; Svanström, H.; Mølgaard-Nielsen, D.; et al. Safety of the HPV Vaccine and Risk of Autonomic Dysfunction Syndromes: Nationwide Cohort. BMJ 2020, 370, m2930.

- Van Damme, P.; Meijer, C.J.L.M.; Kieninger, D.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of the 9-Valent HPV Vaccine in Adolescents. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e28-e39.

- Egemen, D.; Cheung, L.C.; Kinney, W.K.; et al. Risk Estimates Supporting the 2019 ASCCP Management Guidelines. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2238041.

- ACS Guideline Development Group. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and Cancer Prevention: American Cancer Society Guideline. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 274-280.

- Niccolai, L.M.; Hansen, C.E.; Credle, M.; et al. Interventions to Increase HPV Vaccine Coverage among Adults. Vaccine2021, 39, 4711-4720.

- Donovan, B.; Fairley, C.K.; Garland, S.M. Impact of Australia's National HPV Vaccination Program on Genital Warts: Ongoing Surveillance Data. Sex. Health 2022, 19, 307-314.

- Joura, E.A.; Iversen, O.E.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy of a 9-Valent HPV Vaccine. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1453-1462.

- Castle, P.E.; Wheeler, C.M.; Solomon, D.; et al. Interpreting HPV Natural History and Vaccine Protection: Lessons from Screening Cohorts. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011, 20, 991-1001.

- Kyrgiou, M.; Mitra, A.; Arbyn, M.; et al. Fertility and Early Pregnancy Outcomes after Excisional Treatment for Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. BMJ 2014, 349, g6192.

- Brisson, M.; Kim, J.J.; Canfell, K.; et al. Impact of One-Dose vs. Two-Dose HPV Vaccination: Global Modeling Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1113-e1122.

- Huh, W.K.; Ault, K.A.; Chelmow, D.; et al. Use of Primary High-Risk HPV Testing for Cervical Cancer Screening: ASCCP Interim Guidance. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 330-337.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).