Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

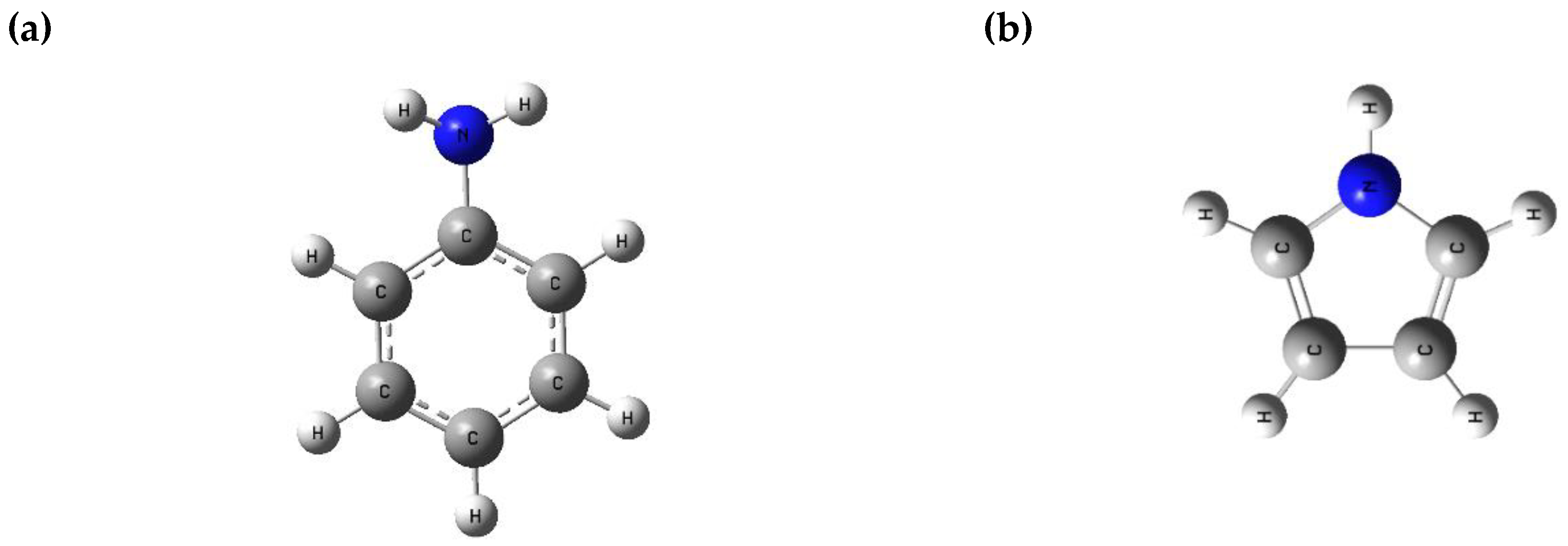

2. Methods

3. Results

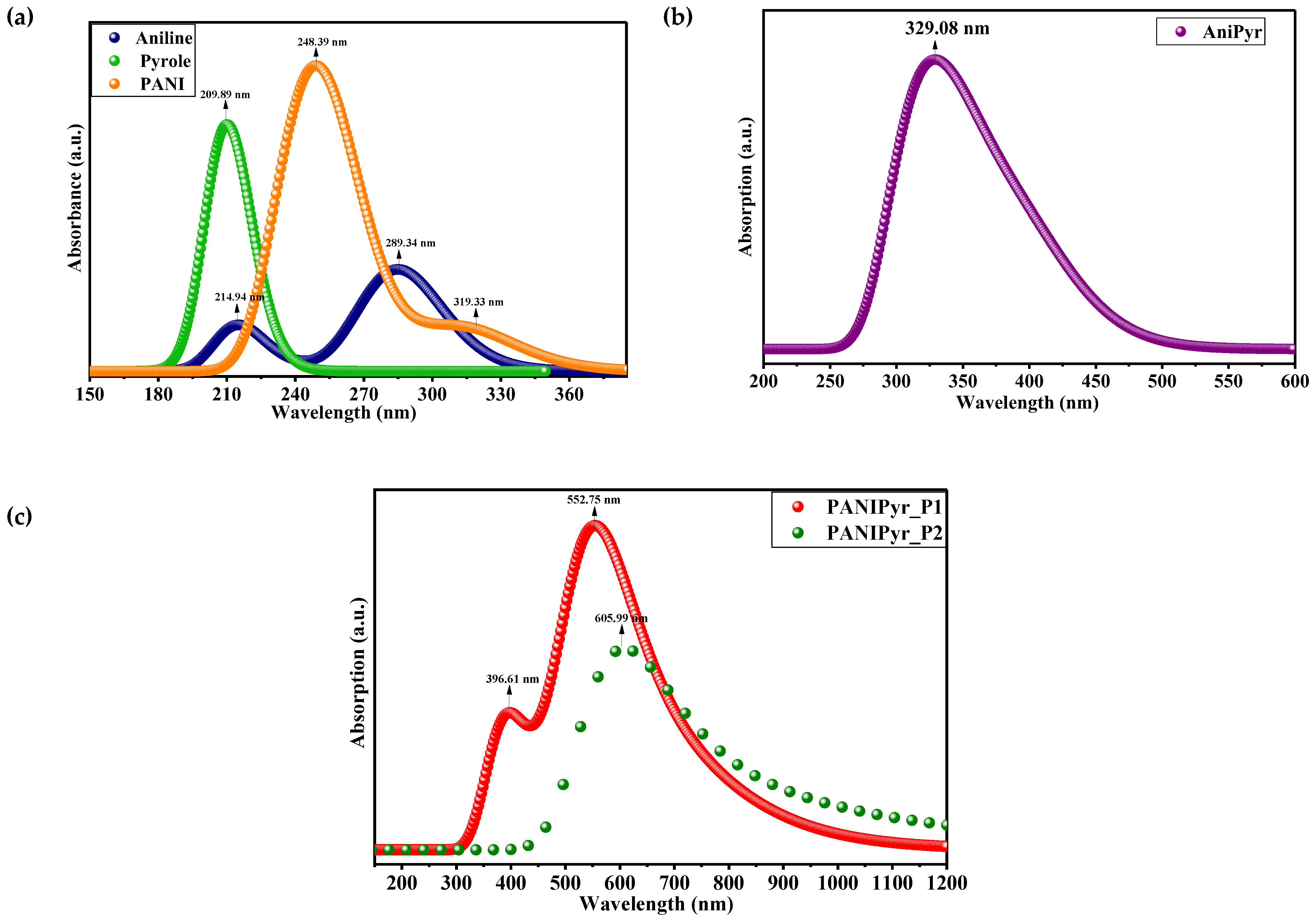

3.1. UV-VIS Absorption Spectroscopy

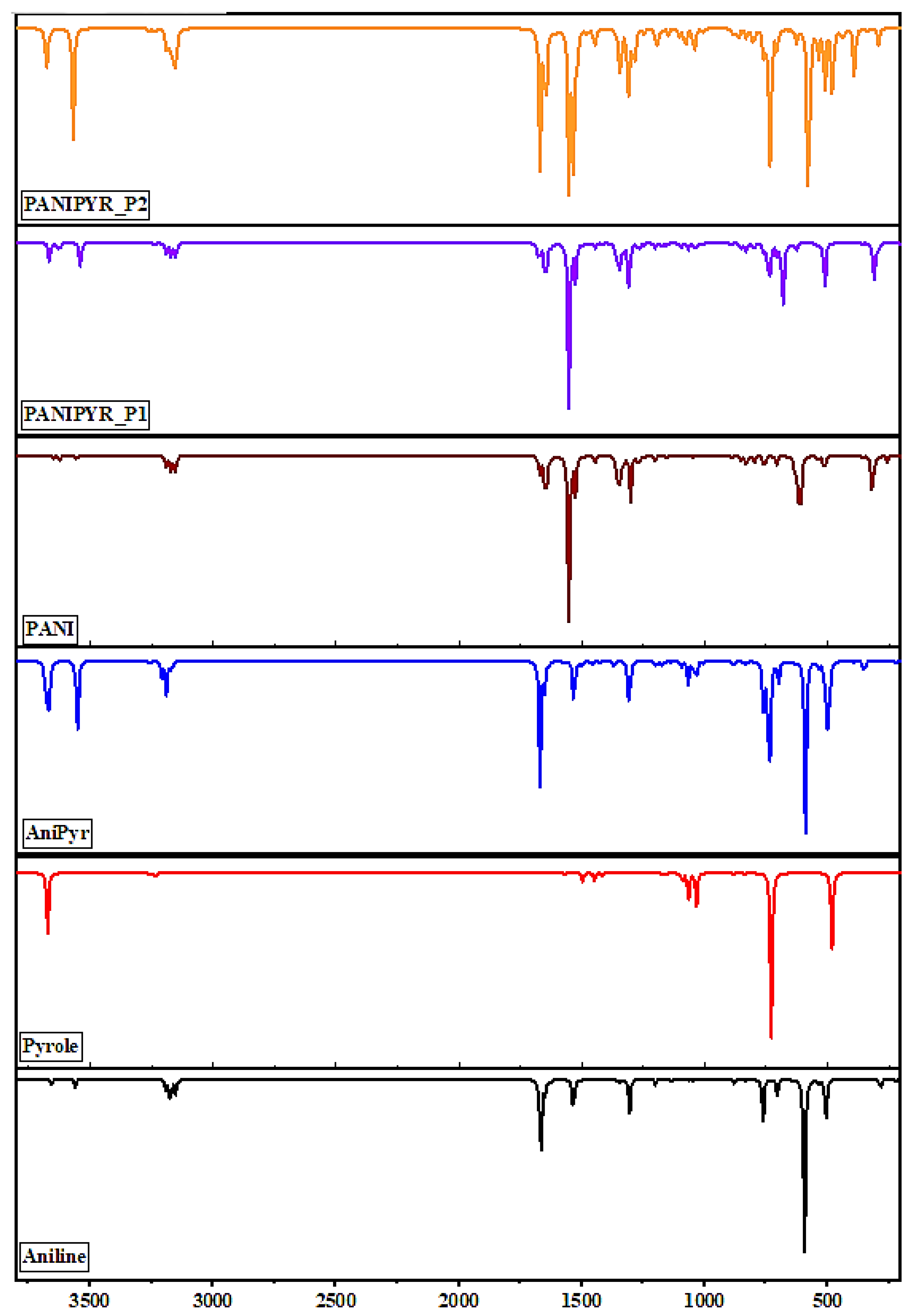

3.2. Molecular Vibrational Frequency

3.3. Orbital and Quantum-Mechanical Analysis

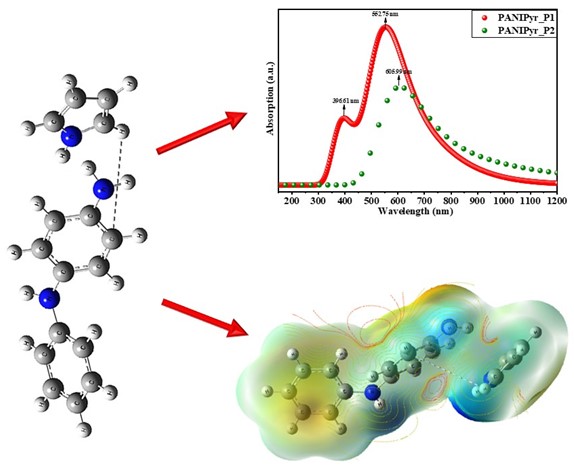

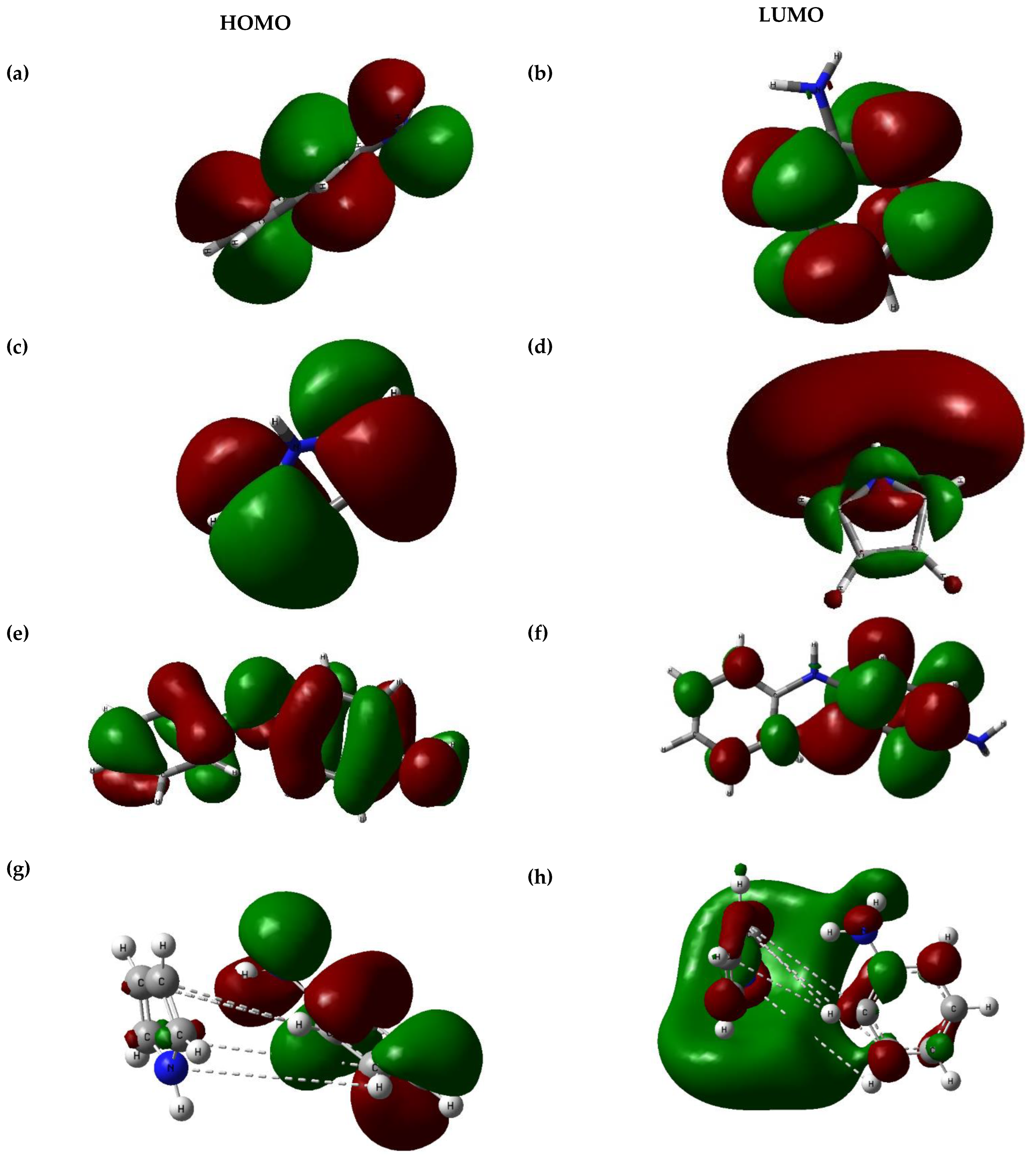

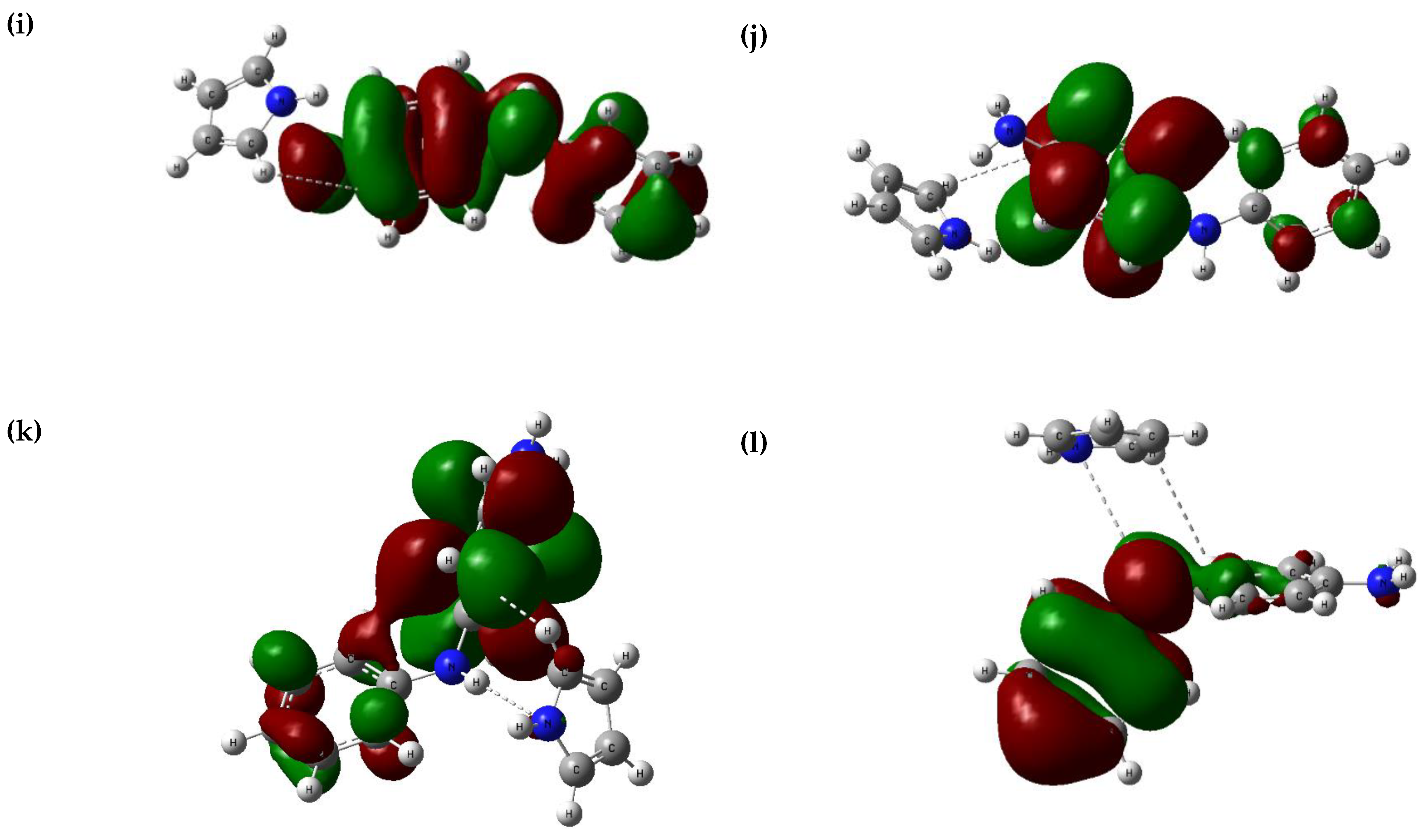

3.4. Interaction of the Optimised Composite Molecules

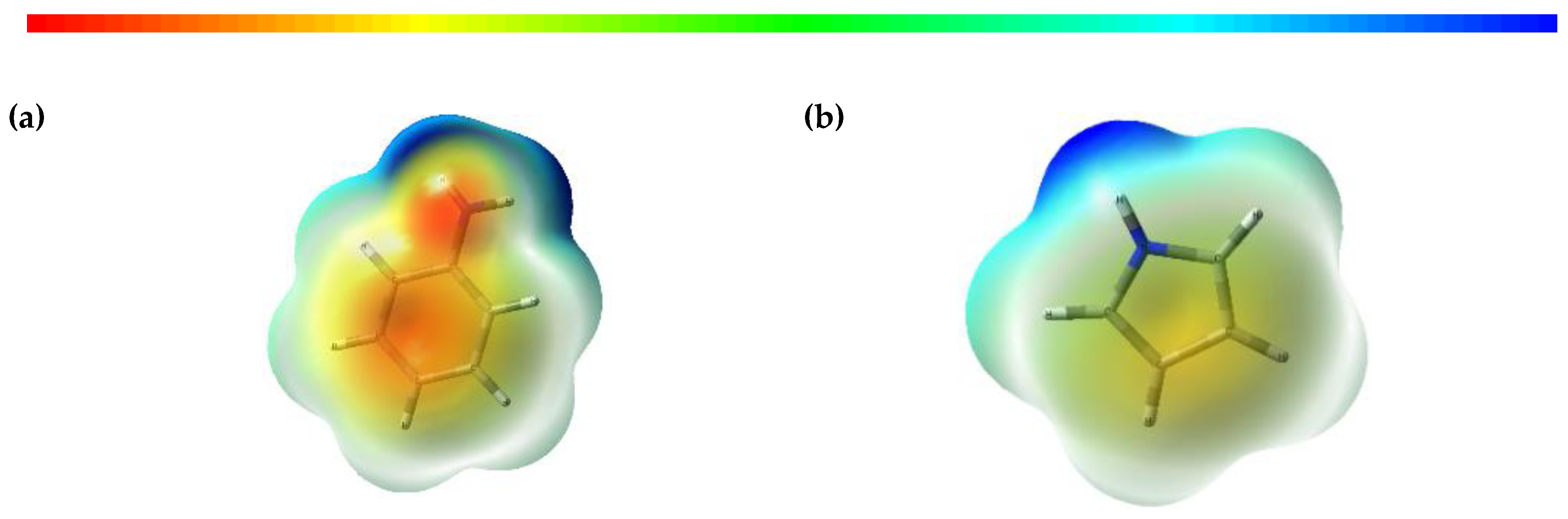

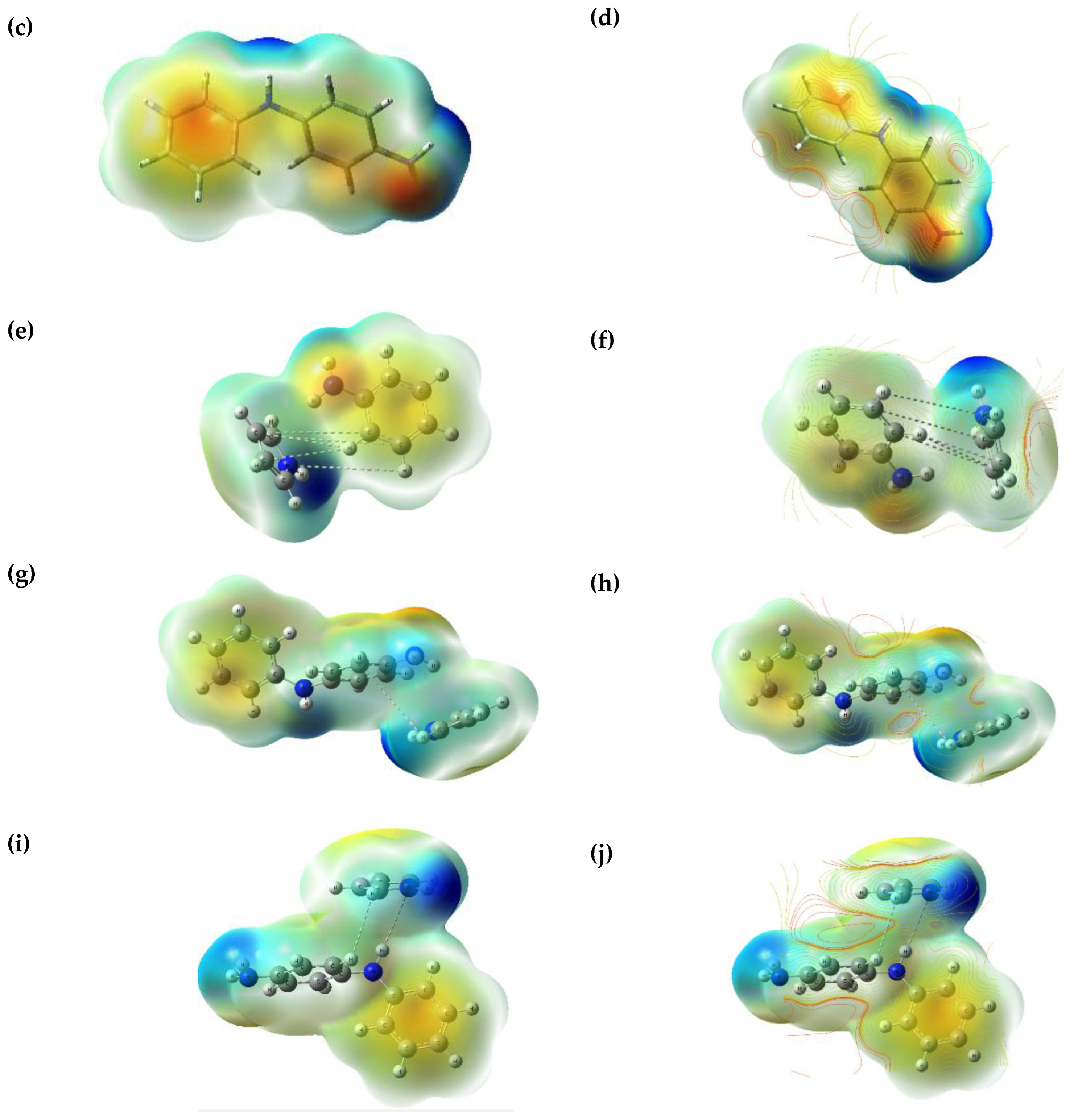

3.5. Electrostatic Potential (ESP) and Contour Mapping of Optimised Molecules

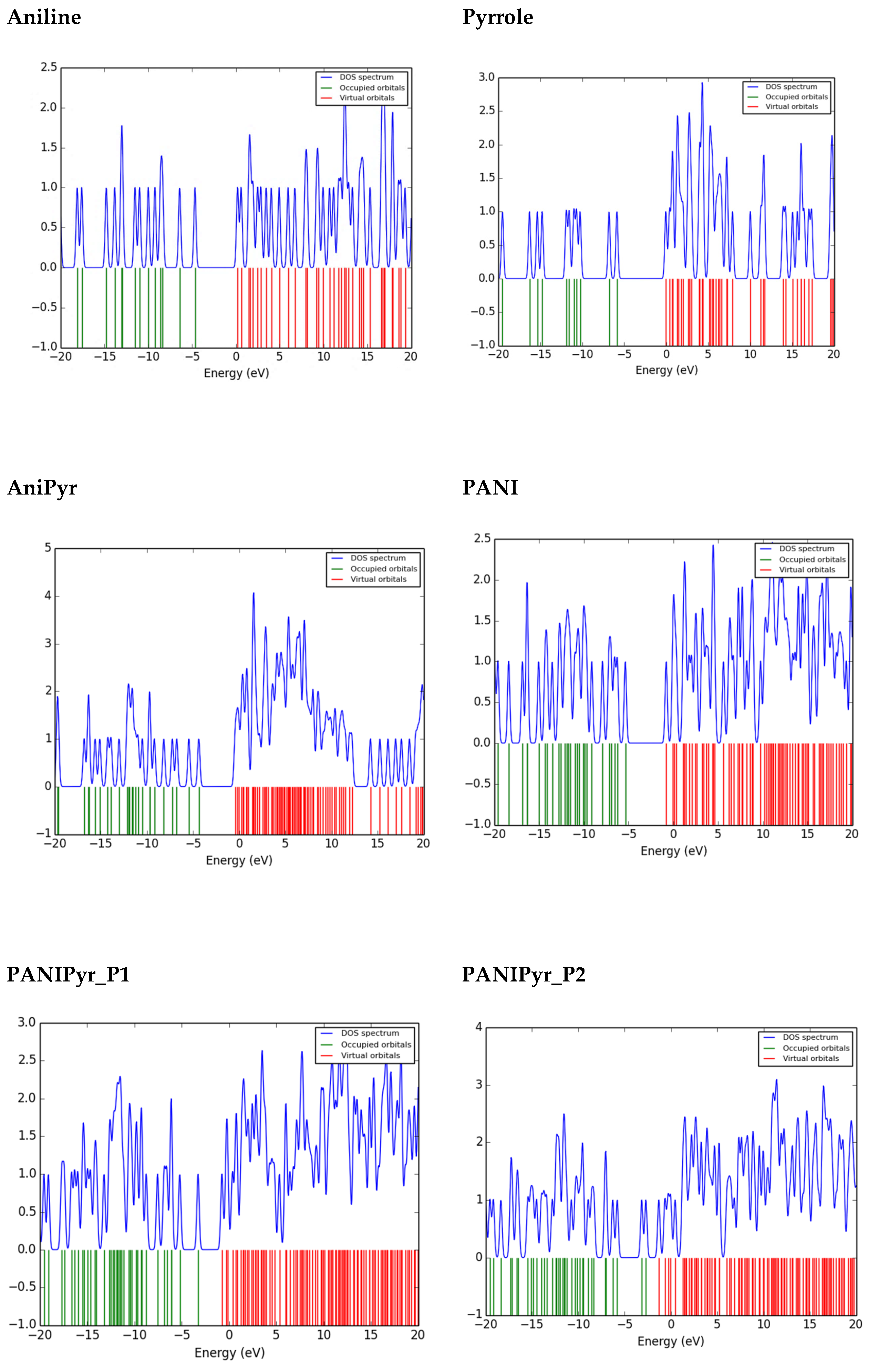

3.6. Density of States of Optimised Molecules

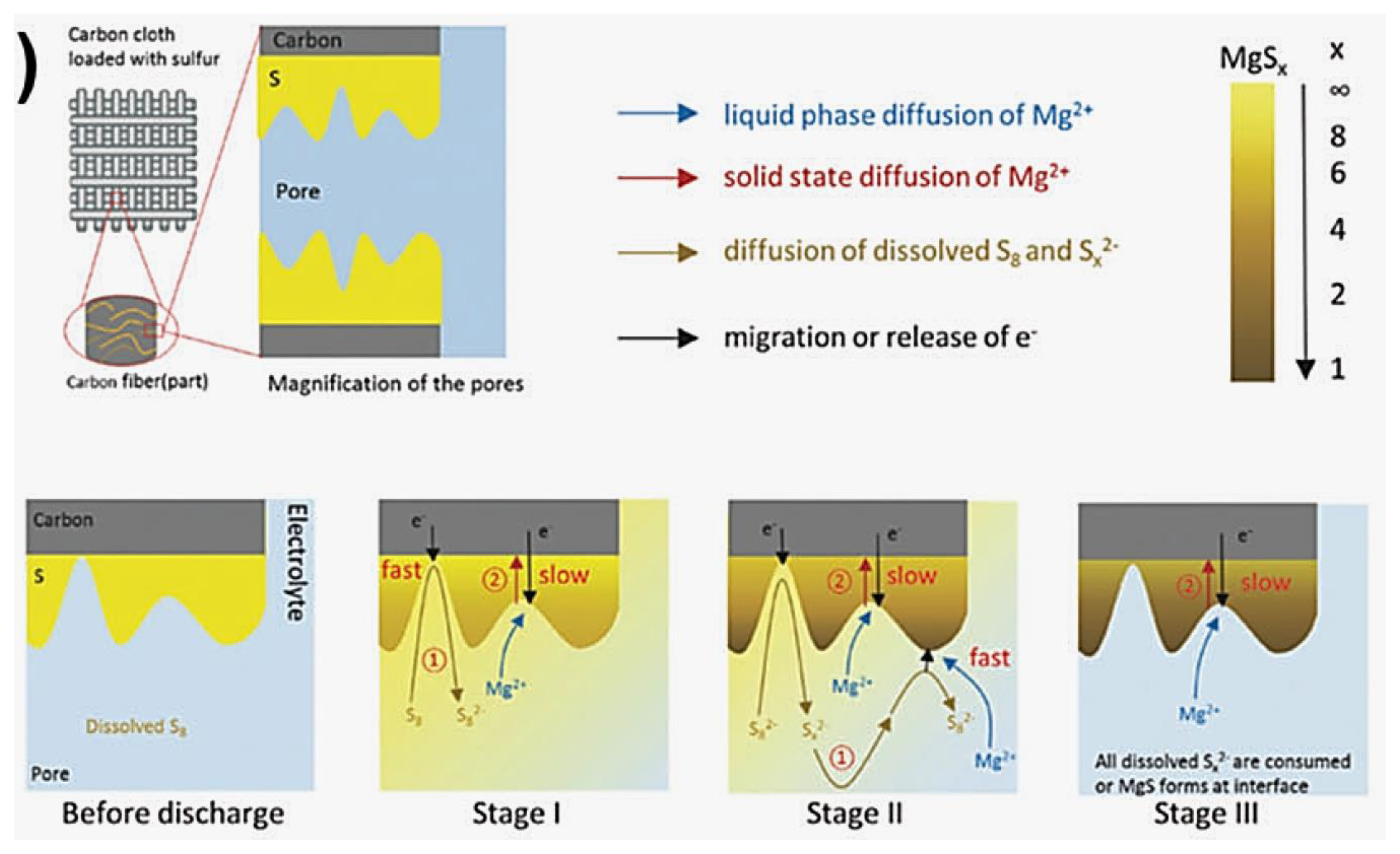

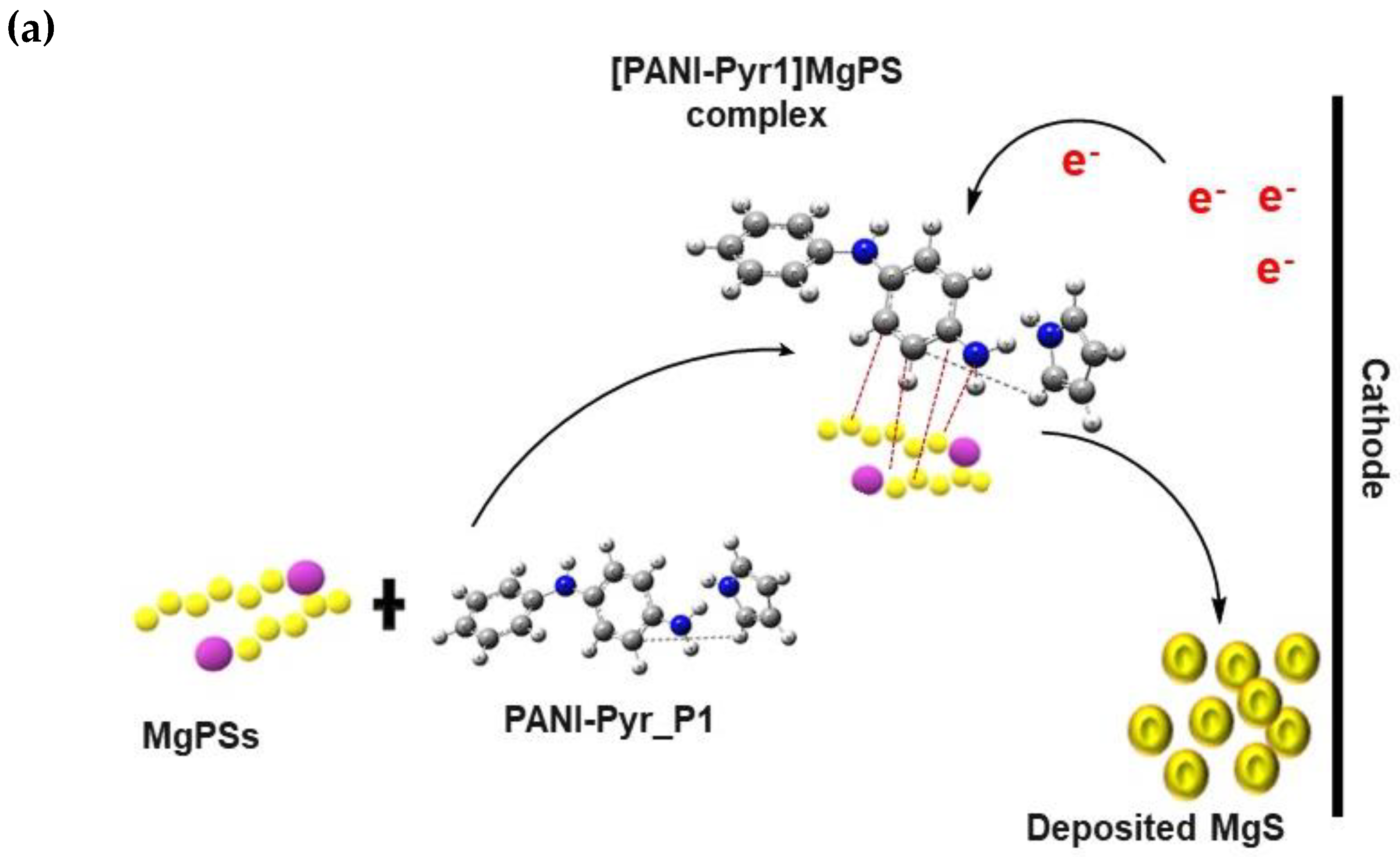

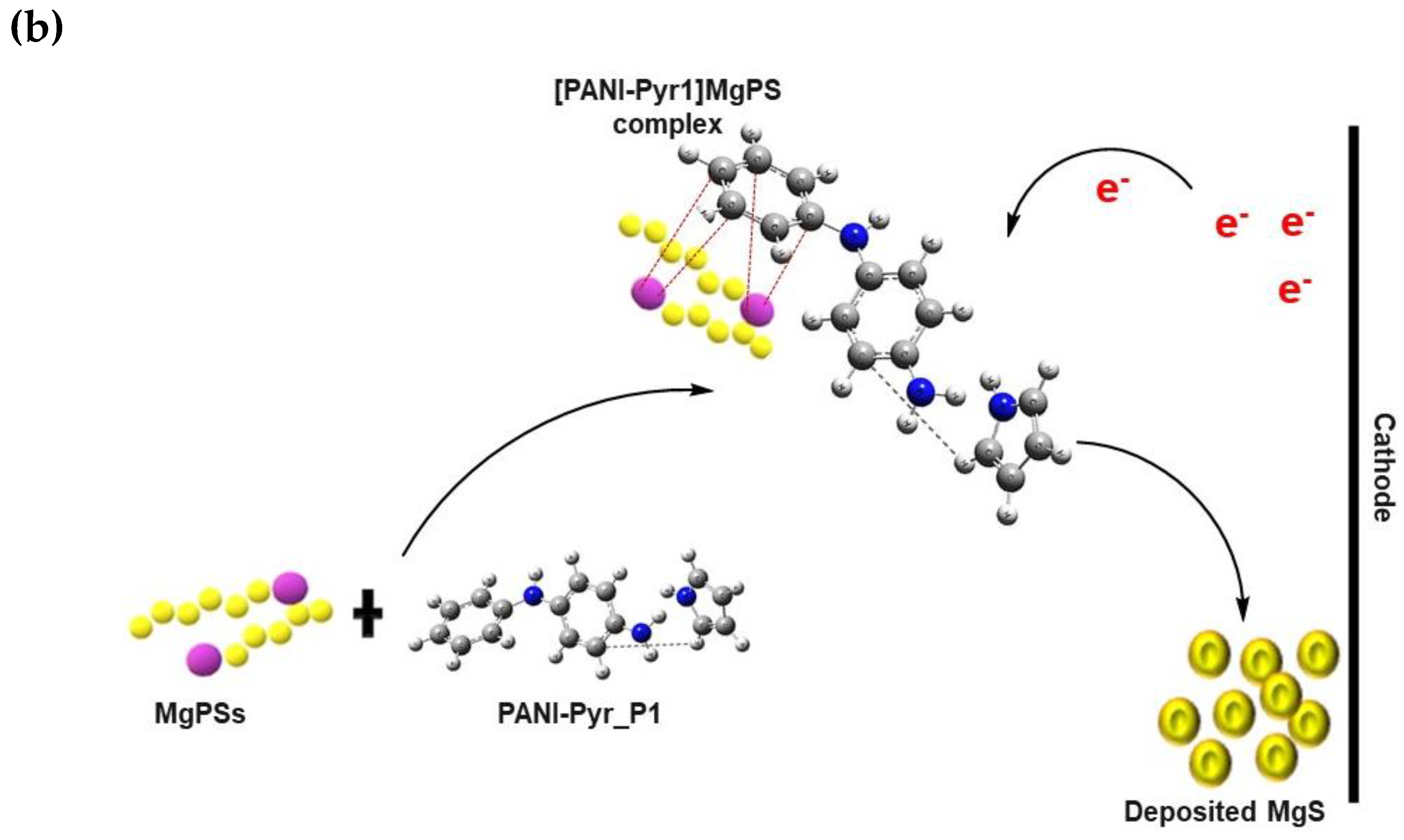

3.7. Proposed Mechanism of Polysulfide Conversion

3.7.1. Electrophilic Reaction

3.7.2. Nucleophilic Reaction

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PANIPyr | Polyaniline-pyrrole |

| HOMO | Highest occupied molecular orbital |

| LUMO | Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| DOS | Density of states |

| ESP | Electrostatic potential |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| BE | Binding energy |

| LIB | Lithium-ion battery |

References

- Manousakis, N.M.; et al. Integration of renewable energy and electric vehicles in power systems: a review. Processes 2023, 11, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; et al. Crystal regulation towards rechargeable magnesium battery cathode materials. Materials Horizons 2020, 7, 1971–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnick, P. and J. Muldoon, A trip to Oz and a peek behind the curtain of magnesium batteries. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30, 1910510. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.Y.; et al. Advances in cathodes for high-performance magnesium-sulfur batteries: a critical review. Batteries 2023, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; et al. Emerging intercalation cathode materials for multivalent metal-ion batteries: status and challenges. Small Structures 2021, 2, 2100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; et al. Polysulfides in magnesium-sulfur batteries. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2306239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; et al. Defect engineering: can it mitigate strong coulomb effect of Mg2+ in cathode materials for rechargeable magnesium batteries? Nano-Micro Letters 2025, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, M.; Chaubey, A.; Malhotra, B.D. Application of conducting polymers to biosensors. Biosensors and bioelectronics 2002, 17, 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, R.; Mecerreyes, D. Polymers with redox properties: materials for batteries, biosensors and more. Polymer Chemistry 2013, 4, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.; Lim, D.; Jo, N. Fabrication of an ion-selective sensor using a conducting polymer actuator. Materials Research Innovations 2011, 15 (suppl. S2), s59–s62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesza, P.J.; et al. Electrocatalytic properties of conducting polymer-based composite film containing dispersed platinum microparticles towards oxidation of methanol. Electrochimica Acta 1999, 44, 2131–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, F.; et al. Sensor applications of polypyrrole for oxynitrogen analytes: a DFT study. Journal of Molecular Modelling 2018, 24, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; et al. The potential application of VS2 as an electrode material for Mg ion battery: A DFT study. Applied Surface Science 2021, 544, 148775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernitskaya, T. and O. Efimov, Polypyrrole: A conducting polymer (synthesis, properties, and applications). Успехи химии 1997, 66, 502–505. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, T. A DFT study of polyaniline/ZnO nanocomposite as a photocatalyst for the reduction of methylene blue dye. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2019, 293, 111528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; et al. Understanding the role of different conductive polymers in improving the nanostructured sulfur cathode performance. Nano Letters 2013, 13, 5534–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, A.; et al. Computational modelling and mechanical characteristics of polymeric hybrid composite materials: an extensive review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2024, 31, 3901–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevher, D. Electroactive Polymers for Next-Generation Energy Storage and Conductive Composite Materials: A Focus on Pani and Pedot-Based Conjugated Polymers. 2024.

- Zhang, W.; et al. Exposure of active edge structure for electrochemical H2 evolution from VS2/MWCNTs hybrid catalysts. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 22949–22954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G. Density functional theory of atoms and molecules. in Horizons of Quantum Chemistry: Proceedings of the Third International Congress of Quantum Chemistry Held at Kyoto, Japan, October 29-November 3, 1979. 1989. Springer.

- Oviedo, P.S.; et al. Exploring the localised to delocalized transition in non-symmetric bimetallic ruthenium polypyridines. Dalton Transactions 2017, 46, 15757–15768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.E.; et al. Gaussian 16. 2016, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT.

- Janak, K.E.; Parkin, G. Experimental evidence for a temperature-dependent transition between normal and inverse equilibrium isotope effects for oxidative addition of H2 to Ir (PMe2Ph)2(CO) Cl. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2003, 125, 13219–13224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, R.A.; et al. Synthesis of polyaniline, polypyrrole, and poly (aniline-co-pyrrole) in deep eutectic solvent: a comparative experimental and computational investigation of their structural, spectral, thermal, and morphological characteristics. Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds 2024, 60, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEWIS, D.F. Frontier orbitals in chemical and biological activity: quantitative relationships and mechanistic implications. Drug metabolism reviews 1999, 31, 755–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhonnar, S.L.; et al. Molecular structure, FT-IR spectra, MEP and HOMO-LUMO investigation of 2-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-phenyl-1, 3, 4-oxadiazole using DFT theory calculations. Advanced Journal of Chemistry-Section A 2021, 4, 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fayemi, O.E.; et al. Investigation of the effects of concentration and voltage on the physicochemical properties of Nylon 6 nanofiber membrane. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 10865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhugul, V. and G. Choudhari, Synthesis and Characterisation of Polypyrrole-Zinc Oxide Nano Composites by Ex-Situ Technique and Study of Their thermal &Electrical Properties. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innovat 2013, 2, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, R.; et al. Preparation of electrochemical supercapacitor based on polypyrrole/gum arabic composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Ali, L.I.; et al. Polypyrrole-coated zinc/nickel oxide nanocomposites as adsorbents for enhanced removal of Pb (II) in aqueous solution and wastewater: an isothermal, kinetic, and thermodynamic study. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 64, 105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjalikrishna, P.K.; Suresh, C.H. Utilisation of the through-space effect to design donor–acceptor systems of pyrrole, indole, isoindole, azulene and aniline. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2024, 26, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.R.; et al. Simplistic fabrication of aniline and pyrrole-based poly (Ani-co-Py) for efficient photocatalytic performance and supercapacitors. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 37860–37869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadr, R.B.; et al. Quantum chemical calculation for the synthesis of some thiazolidin-4-one derivatives. Journal of Molecular Structure 2024, 1308, 138055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, R.A.; et al. N, N-Bis (2, 4-dihydroxy benzaldehyde) benzidine: Synthesis, characterisation, DFT, and theoretical corrosion study. Journal of Molecular Structure 2024, 1300, 137279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, R.A.; et al. A novel coumarin-triazole-thiophene hybrid: synthesis, characterisation, ADMET prediction, molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies with a series of SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Journal of Chemical Sciences 2023, 135, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamad, D.M.; Omer, R.A.; Othman, K.A. Quantum chemical analysis of amino acids as anti-corrosion agents. Corrosion Reviews 2023, 41, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, S.A.; Hamad, H.; Ali, T.E. Deeper insights into the density functional theory of structural, optical, and photoelectrical properties using 5-[(4-oxo-4H-chromen-3-yl) methylidene]-4-oxo (thioxo)-6-thioxo-2-sulfido-1, 3, 2-diazaphosphinanes. Optical and Quantum Electronics 2023, 55, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.A.; Lee, H.T. Polyaniline plasticised with 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidone: structure and doping behaviour. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 3254–3261. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel, J.; et al. Electrochemical properties of lithium polymer batteries with doped polyaniline as cathode material. Materials Research Bulletin 2012, 47, 2815–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koparir, P.; et al. Synthesis, characterisation and computational analysis of thiophene-2, 5-diylbis ((3-mesityl-3-methylcyclobutyl) methanone). Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2023, 43, 6107–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.L.; Sanborn, P.N.; Gschwend, P.M. Nucleophilic substitution reactions of dihalomethanes with hydrogen sulfide species. Environmental science & technology 1992, 26, 2263–2274. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Liu, X. Sulfur immobilization by “chemical anchor” to suppress the diffusion of polysulfides in lithium–sulfur batteries. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2018, 5, 1701274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters (eV) | Aniline | Pyrrole | AniPyr | PANI | PANIPyr_P1 | PANIPyr_P2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHOMO (ƐH) | -0.20646 | -0.21853 | -0.20245 | -0.18070 | -0.18011 | -0.18933 |

| ELUMO (ƐL) | -0.00337 | -0.00312 | -0.00819 | -0.01113 | -0.01279 | -0.01213 |

| Energy gap (Ɛgap) | 0.20309 | 0.21541 | 0.19426 | 0.16957 | 0.16732 | 0.1772 |

| Ionisation energy (I.E) | 0.20646 | 0.21853 | 0.20245 | 0.18070 | 0.18011 | 0.18933 |

| Electron Affinity (E.A) | 0.00337 | 0.00312 | 0.00819 | 0.01113 | 0.01279 | 0.01213 |

| Hardness (η) | 0.101545 | 0.107705 | 0.09713 | 0.084785 | 0.08366 | 0.0886 |

| Softness (eV-1) | 9.848 | 9.285 | 10.296 | 11.795 | 11.953 | 11.287 |

| Electronegativity (χ) | 0.105 | 0.111 | 0.105 | 0.096 | 0.096 | 0.101 |

| Chemical potential (μ) | -0.105 | -0.111 | -0.105 | -0.096 | -0.096 | -0.101 |

| Electrophilicity (ω) | 0.054 | 0.0572 | 0.0567 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.058 |

| Nucleophilicity (Ɛ), eV-1 | 18.519 | 17.544 | 17.637 | 18.519 | 18.182 | 17.241 |

| Back donation (ΔEbd) | -0.025 | -0.027 | -0.024 | -0.021 | -0.0209 | -0.022 |

| Electron transfer (ΔNmax) | 1.034 | 1.031 | 1.081 | 1.132 | 1.148 | 1.139 |

| Fermi level (EF) | -0.105 | -0.111 | -1053 | -0.096 | -0.097 | -0.101 |

| Work function (Φ) | 0.105 | 0.111 | 1053 | 0.096 | 0.097 | 0.101 |

| Optical electronegativity (Δχ*) | 0.054 | 0.058 | 0.052 | 0.045 | 0.0455 | 0.047 |

| Composites | AniPyr | PANIPyr_P1 | PANIPyr_P2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energy (eV) | 2.547 | -0.024 | 0.092 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).