Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

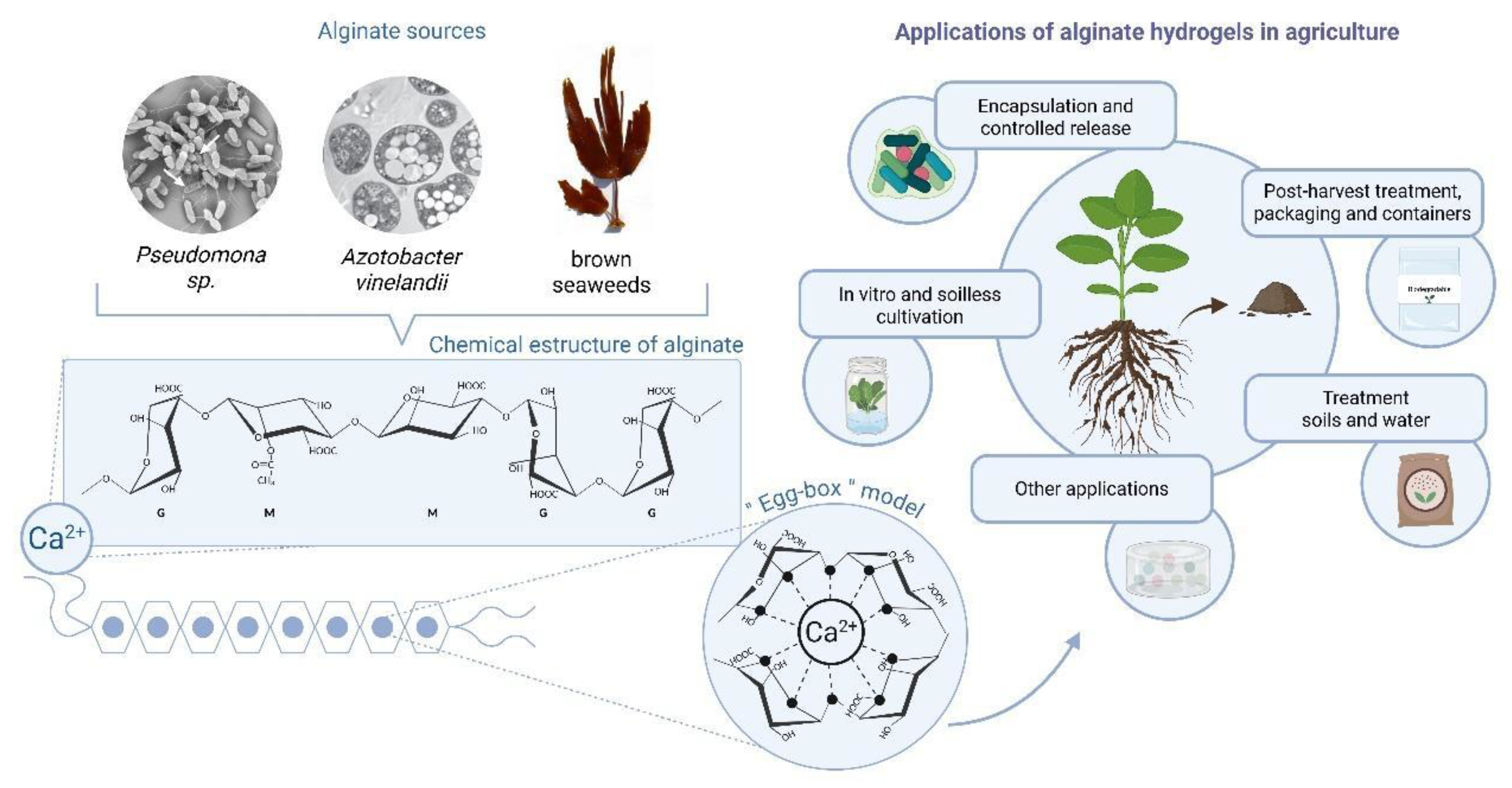

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

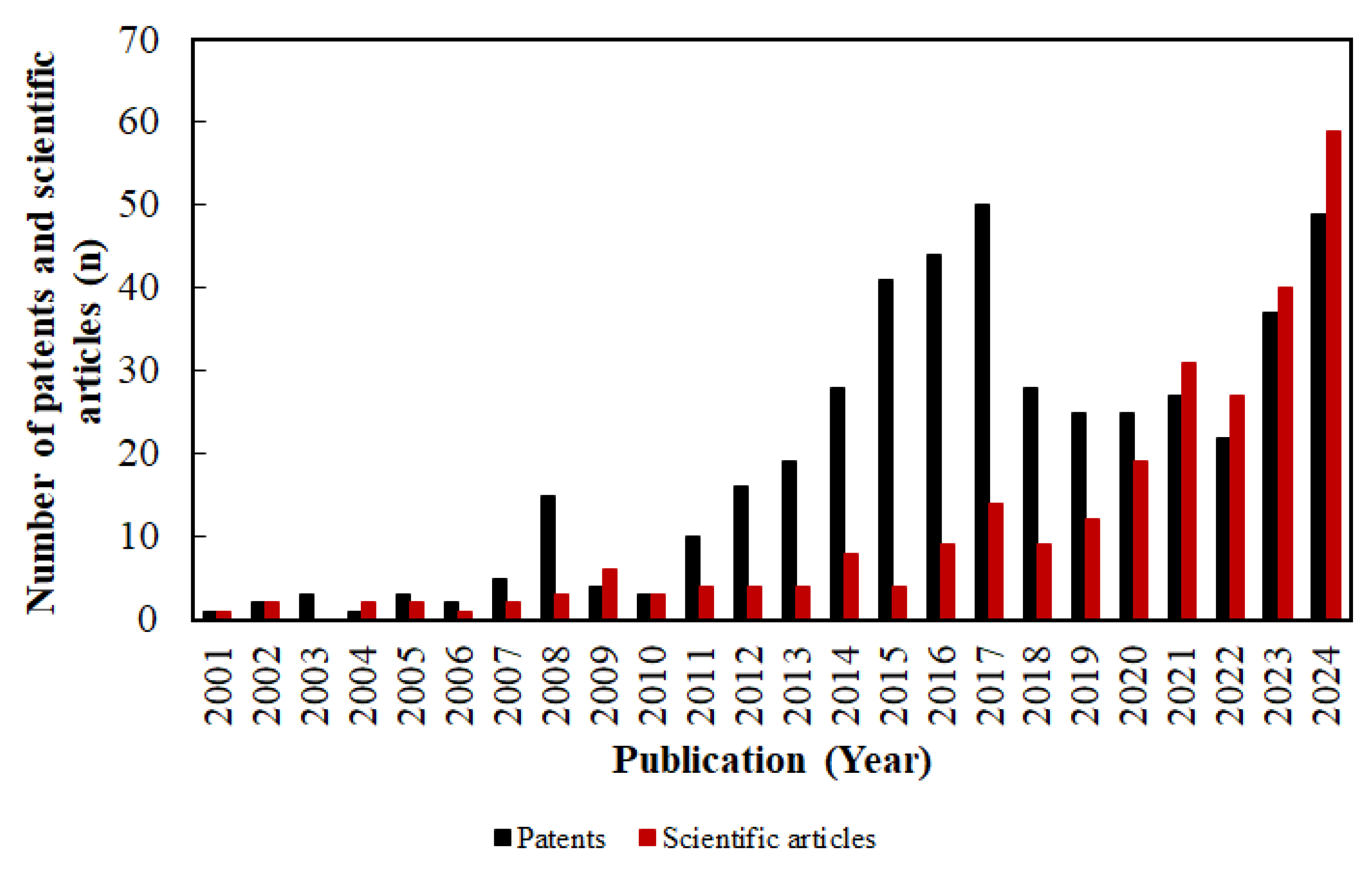

2.1. Bibliometric Analysis of Scientific Production on Alginate Applications in Agriculture

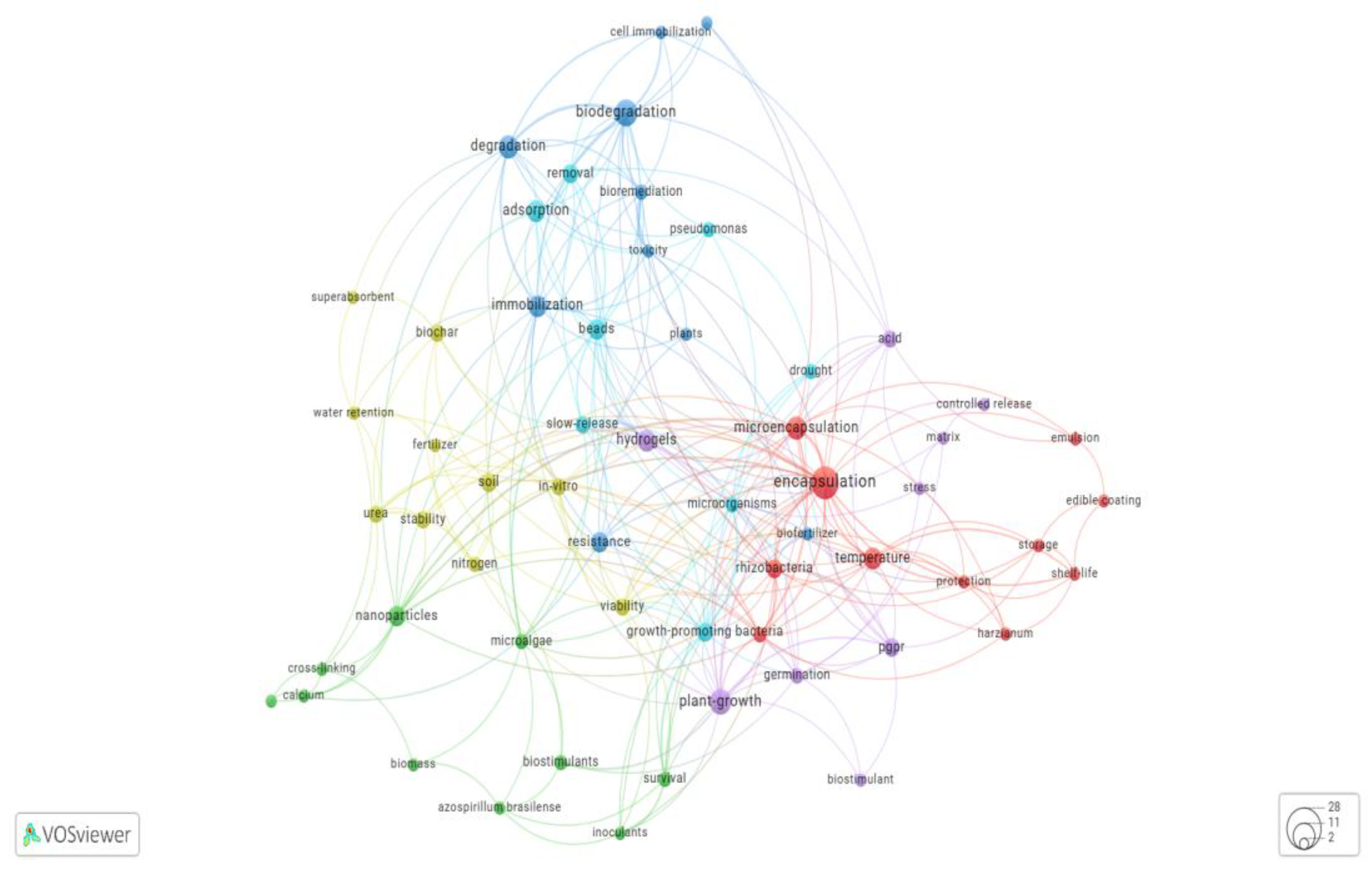

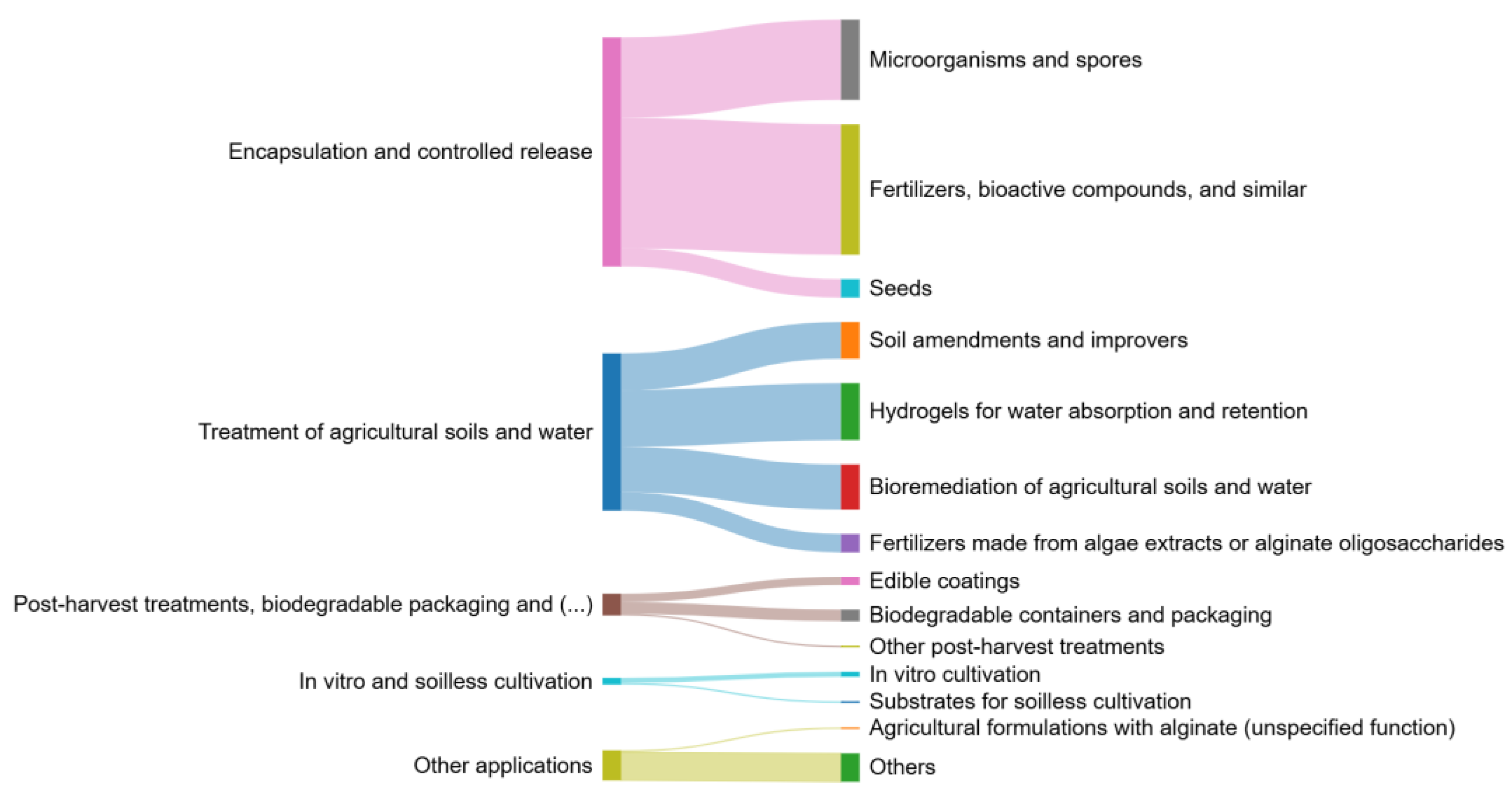

2.1.1. Clustering Analysis

2.1.2. Categorization of Scientific Documents According to Clustering Categories and Validation Levels

2.1.3. Research Topics According to Clustering Categories

2.1.3.1. Encapsulation and Controlled Release Of Microorganisms and Agrochemicals

- 2.1.3.1.1. Encapsulation and Controlled Release Of Microorganisms and Spores

- 2.1.3.1.2. Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Fertilizers and Bioactive Compounds

- 2.1.3.1.3. Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Seeds

2.1.3.2. Soil and Water Treatments

- 2.1.3.2.1. Soil amendments and Conditioners

- 2.1.3.2.2. Hydrogels for Absorption and Water Retention

- 2.1.3.2.3. Bioremediation of Agricultural Soils and Waters

- 2.1.3.2.4. Fertilizers from Algal Extracts and Alginate Oligosaccharides

- 2.1.3.3. Postharvest Treatments and Biodegradable Packaging for Agricultural Products

- 2.1.3.3.1.

- Edible Coatings

- 2.1.3.3.2. Biodegradable Packaging

- 2.1.3.3.3. Other Postharvest Treatments

- 2.1.3.4. In Vitro and Soilless Cultivation

- 2.1.3.4.1.

- In Vitro Cultivation

- 2.1.3.4.2. Substrates for Soilless Cultivation

- 2.1.3.5. Other Applications of Alginate in Agriculture

- 2.1.3.5.1. Agricultural Formulations with Alginate (Unspecified Function)

- 2.1.3.5.2. Miscellaneous: Pest Monitoring and Culture Protection

2.1.4. Trends and Emerging Topics Research

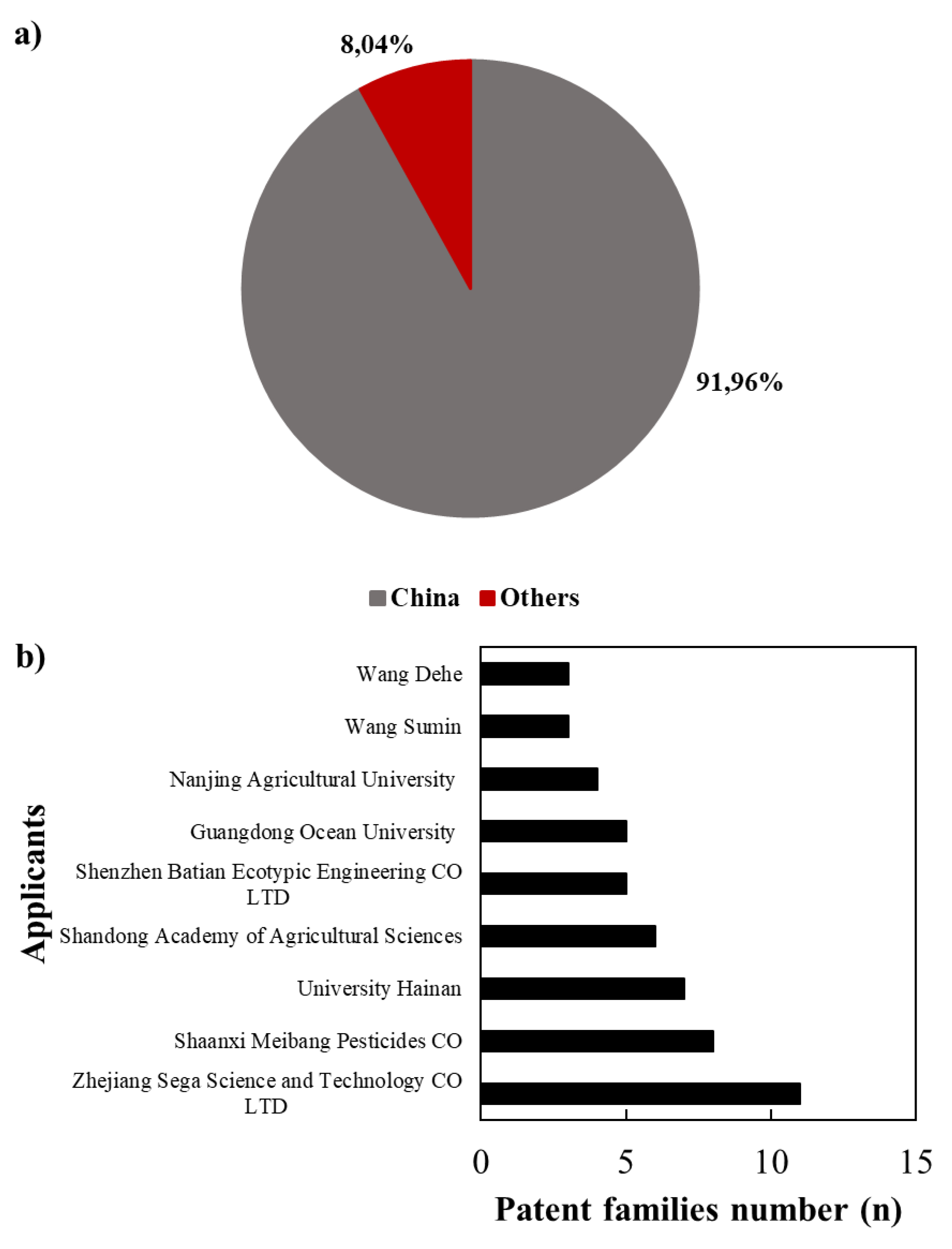

2.2. Patentometric Analysis

2.2.1. Patent Landscape of Alginate Hydrogel-Based Technologies

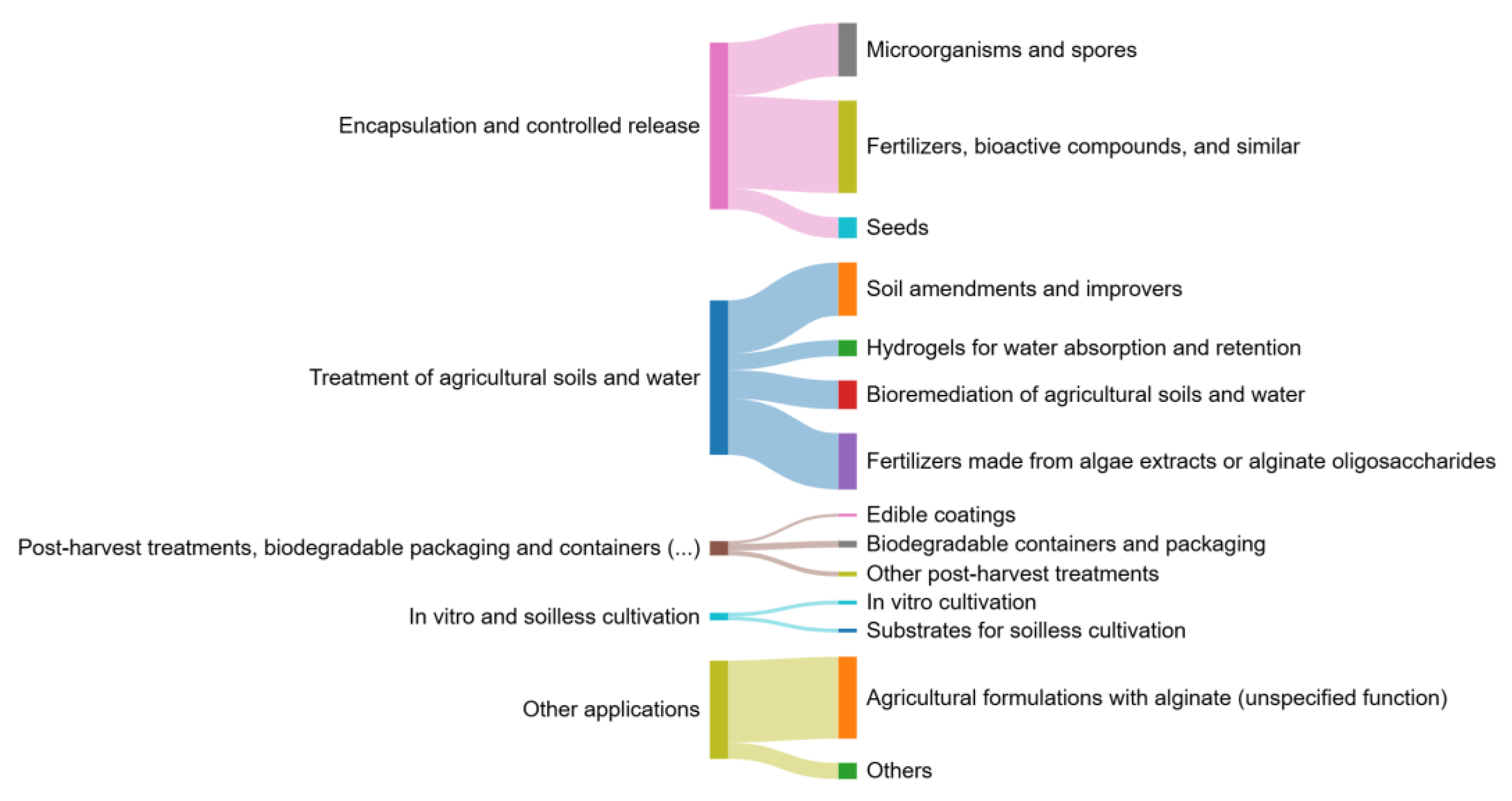

2.2.2. Categorization of Patent Families According to Clustering Categories

2.2.3. Technological Development Areas According to Clustering Categories

2.2.3.1. Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Microorganisms and Agrochemicals

- 2.2.3.1.1. Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Microorganisms and Spores

- 2.2.3.1.2. Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Fertilizers and Bioactive Compounds

- 2.2.3.1.3. Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Seeds

- 2.2.3.2. Soil and Water Treatments

- 2.2.3.2.1.

- Soil Amendments and Conditioners

- 2.2.3.2.2. Hydrogels for Absorption and Water Retention

- 2.2.3.2.3. Bioremediation of Agricultural Soils and Waters

- 2.2.3.2.4. Fertilizers from Algal Extracts and Alginate Oligosaccharides

2.2.3.3. Postharvest Treatments and Biodegradable Packaging for Agricultural Products

- 2.2.3.3.1. Edible Coatings

- 2.2.3.3.2. Biodegradable Packaging

- 2.2.3.3.3. Other Postharvest Treatments

2.2.3.4. In Vitro and Soilless Cultivation

- 2.2.3.4.1. In Vitro Cultivation

- 2.2.3.4.2. Substrates for Soilless Cultivation

2.2.3.5. Other Applications of Alginate in Agriculture

- 2.2.3.5.1. Agricultural Formulations with Alginate (Unspecified Function)

- 2.2.3.5.2. Miscellaneous: Pest Monitoring and Culture Protection

2.2.4. Technological Development Trends and Emerging Technologies

2.2.5. Comparative Analysis of Scientific and Technological Production

3. Conclusions and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bibliometric Analysis of Scientific Production on Alginate Applications in Agriculture

4.1.1. Data Collection and Processing

4.1.2. Clustering Analysis

4.1.3. Categorization of Scientific Documents According to Clustering Categories and Validation Levels

4.2. Patentometric Analysis of Technological Applications of Alginate in Agriculture

4.2.1. Data Collection and Processing

4.2.2. Patent Landscape of Alginate Hydrogel-Based Technologies

- Main jurisdictions of patent filing.

- Leading applicants.

- Main International Patent Classification (IPC) codes.

- Patent families with the highest number of applications.

- Specific patent documents with the highest number of citations in other patents.

4.2.3. Categorization of Patent Families According to Clustering Categories

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Bejenaru, L.E.; Bejenaru, C.; Blendea, A.; Mogoşanu, G.D.; Biţă, A.; Boia, E.R. Advancements in Hydrogels: A Comprehensive Review of Natural and Synthetic Innovations for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.-C.; Liu, X.; Zhao, C. Shear and Compressive Stiffening of Dual-Cross-Linked Alginate Hydrogels with Tunable Viscoelasticity. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2025, 8, 3899–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Hwang, T.; Jo, S.; Wooh, S.; Lee, H.; Jung, Y.; Yoo, J. Unveiling the Diverse Principles for Developing Sprayable Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, D.; Behera, D.; Pattnaik, S.S.; Behera, A.K. Advances in Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels: Synthesis, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical and Environmental Fields. Discover Polymers 2025, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, H.; Chen, X.; Tan, H. Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels: From Polymer to Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.C.; Debnath, S.; Sridhar, K.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Nayak, P.K.; Sharma, M. A Comprehensive Review of Food Hydrogels: Principles, Formation Mechanisms, Microstructure, and Its Applications. Gels 2022, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Xian, C.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, G.; Wu, J. Natural Polymer-Based Hydrogels with Enhanced Mechanical Performances: Preparation, Structure, and Property. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2019, 8, 1900670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, K.; Huang, J. Photopolymerized multifunctional sodium alginate-based hydrogel for antibacterial and coagulation dressings. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 260, 129428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, C. S. C. , Poh, P. E., Pasbakhsh, P., Tey, B. T., Yeoh, H. K., & Chan, E. S. Physicochemical characterization of halloysite/alginate bionanocomposite hydrogel. Applied clay science, 2014, 101, 444-454. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Montesinos, Y. E. , & Hernández-Carmona, G. Seasonal and geographic variations of Macrocystis pyrifera chemical composition at the western coast of Baja California. Ciencias Marinas, 1991, 17(3), 91-107, doi.org/10.7773/cm.v17i3.816.

- Savić Gajić, I. M. , Savić, I. M., Ivanovska, A. M., Vunduk, J. D., Mihalj, I. S., & Svirčev, Z. B. Improvement of alginate extraction from brown seaweed (Laminaria digitata L.) and valorization of its remaining ethanolic fraction. Marine Drugs, 2024, 22(6), 280.

- Bojorges, H. , Martínez-Abad, A., Martinez-Sanz, M., Rodrigo, M. D., Vilaplana, F., López-Rubio, A., & Fabra, M. J. Structural and functional properties of alginate obtained by means of high hydrostatic pressure-assisted extraction. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2023, 299, 120175. [Google Scholar]

- Peteiro, C. Alginate Production from Marine Macroalgae, with Emphasis on Kelp Farming. In: Rehm, B., Moradali, M. (eds) Alginates and Their Biomedical Applications. Springer Series in Biomaterials Science and Engineering, 2018, vol 11. Springer, Singapore.

- Kelly, B. J. , & Brown, M. T. Variations in the alginate content and composition of Durvillaea antarctica and D. willana from southern New Zealand. Journal of applied phycology, 2000, 12(3), 317-324.

- Mendoza-Cerezo, L.; Rodríguez-Rego, J.M.; Macias-García, A.; Iñesta-Vaquera, F.D.A.; Marcos-Romero, A.C. Study of Printable and Biocompatible Alginate–Carbon Hydrogels for Sensor Applications: Mechanical, Electrical, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation. Gels 2025, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Barrera, A. , Sanchez-Rosales, F., Padilla-Córdova, C., Andler, R., & Peña, C. Molecular weight and guluronic/mannuronic ratio of alginate produced by Azotobacter vinelandii at two bioreactor scales under diazotrophic conditions. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 2021, 44(6), 1275-1287.

- Ponce, B.; Urtuvia, V.; Maturana, N.; Peña, C.; Díaz-Barrera, A. Increases in Alginate Production and Transcription Levels of Alginate Lyase (alyA1) by Control of the Oxygen Transfer Rate in Azotobacter Vinelandii Cultures under Diazotrophic Conditions. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2021, 52, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, B.; Zamora-Quiroz, A.; González, E.; Andler, R.; Díaz-Barrera, A. Advances in Alginate Biosynthesis: Regulation and Production in Azotobacter Vinelandii. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2025, 13, 1593893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.; Castillo, T.; Flores, C.; Núñez, C.; Galindo, E.; Peña, C. Production of Alginates with High Viscosifying Power and Molecular Weight by Using the AT9 Strain of Azotobacter Vinelandii in Batch Cultures under Different Oxygen Transfer Conditions. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2023, 98, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, C. , Díaz-Barrera, A., Martínez, F., Galindo, E., & Peña, C. Role of oxygen in the polymerization and de-polymerization of alginate produced by Azotobacter vinelandii. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology, 2015, 90(3), 356-365.

- Tan, J.; Luo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, X.; Li, D.; Lai, X.; Liu, Y. Development of alginate-based hydrogels: Crosslinking strategies and biomedical applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 239, 124275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, H.; Srebnik, S. Structural characterization of sodium alginate and calcium alginate. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 2588–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, D.R.; Biswal, T. Alginate and Its Application to Tissue Engineering. SN Applied Sciences 2021, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.-C.; Yan, J.-N.; Wang, C.; Lai, B.; Zhang, L.-C.; Wu, H.-T. Construction and Characterization of Alginate/Calcium β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate Hydrogels: Effect of M/G Ratios and Calcium Ion Concentration. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 273, 133162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judith, R.; Adrián, V.N.; Gomes, C.É.T. Preparation of Sodium Alginate Films Incorporated with Hydroalcoholic Extract of Macrocystis Pyrifera L. Foods and Raw materials 2023, 11, 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.B.; Tøndervik, A.; Gaardløs, M.; Ertesvåg, H.; Sletta, H.; Aachmann, F.L. Mannuronate C-5 Epimerases and Their Use in Alginate Modification. Essays in Biochemistry 2023, 67, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhai, R.; Hu, B.; Williams, P.A.; Yang, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, T. Preparation and Characterization of Hydrophobically-Modified Sodium Alginate Derivatives as Carriers for Fucoxanthin. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 157, 110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cano, B.; Mendoza-Meneses, C.J.; García-Trejo, J.F.; Macías-Bobadilla, G.; Aguirre-Becerra, H.; Soto-Zarazúa, G.M.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A. Review and Perspectives of the Use of Alginate as a Polymer Matrix for Microorganisms Applied in Agro-Industry. Molecules 2022, 27, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, C.; Galindo, E.; Büchs, J. The Viscosifying Power, Degree of Acetylation and Molecular Mass of the Alginate Produced by Azotobacter Vinelandii in Shake Flasks Are Determined by the Oxygen Transfer Rate. Process Biochemistry 2011, 46, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapatsila, S.; Taras, R.; Varchuk, D.; Nosova, N.; Varvarenko, S.; Samaryk, V. Influence of Calcium Crosslinker Form on Alginate Hydrogel Properties. Gels 2025, 11, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čič, M.; Petek, M. Sustainable Cyclodextrin Modification and Alginate Incorporation: Viscoelastic Properties, Release Behavior and Morphology in Bulk and Microbead Hydrogel Systems. Gels 2025, 11, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheaburu, C.N.; Yilmaz, Ö. Development and Characterization of a Wound-Healing System Based on a Marine Biopolymer Hydrogel. Gels 2025, 11, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z. , Yang, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, F., Hou, Z., Li, Z., Shi, J. & Shen, T. A Critical Review: Gel-Based Edible Inks for 3D Food Printing: Materials, Rheology–Geometry Mapping, and Control. Gels, 2025, 11(10), 780.

- Yoneyama, F.; Yamamoto, M.; Hashimoto, W.; Murata, K. Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate and Alginate from Glycerol by Azotobacter Vinelandii under Nitrogen-Free Conditions. Bioengineered 2015, 6, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juříková, T.; Mácha, H.; Lupjanová, V.; Pluháček, T.; Marešová, H.; Papoušková, B.; Luptáková, D.; Patil, R.H.; Benada, O.; Grulich, M.; et al. The Deciphering of Growth-Dependent Strategies for Quorum-Sensing Networks in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.; Miranda, G.; Rocha, C.P.; Pato, R.L.; Cotas, J.; Gonçalves, A.M.M.; Santos, S.M.D.; Bahcevandziev, K.; Pereira, L. Portuguese Kelps: Feedstock Assessment for the Food Industry. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 10681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, E. S. M.; Elbagory, M.; Mahdy, M. E.; Abo-Koura, H. A.; & Omara, A. E. D. Microencapsulation of Bacillus megaterium in humic acid-supplied alginate beads enhances tomato growth and suppresses the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica under greenhouse conditions. Horticulturae, 1012. [Google Scholar]

- Saberi Riseh, R.; Moradi Pour, M.; & Ait Barka, E. A Novel route for double-layered encapsulation of Streptomyces fulvissimus Uts22 by alginate–Arabic gum for controlling of Pythium aphanidermatum in Cucumber. Agronomy, 2022, 12(3), 655.

- Merwe, R.D.T.; Goosen, N.J.; Pott, R.W.M. Macroalgal-Derived Alginate Soil Amendments for Water Retention, Nutrient Release Rate Reduction, and Soil pH Control. Gels 2022, 8, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinelli, N.; Sabando, C.; Rodríguez-Llamazares, S.; Bouza, R.; Castaño, J.; Valverde, J. C.; Rubilar, R.; Frizzo, M.; & Recio-Sánchez, G. Sodium alginate-g-polyacrylamide hydrogel for water retention and plant growth promotion in water-deficient soils. Industrial Crops and Products, 2024, 222, 119759.

- Pandey, V. K.; Shafi, Z.; Choudhary, P.; Pathak, A.; & Rustagi, S. ; & Rustagi, S. Navigating the Functional and Bioactive Landscape of Sodium Alginate-Based Edible Coatings for Modernized Fruit Preservation. Journal of Food Safety, 2025, 45(3), e70020.

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, C.; Gan, Z.; Chen, J.; & Wan, C. C. Loquat leaf extract and alginate based green composite edible coating for preserving the postharvest quality of Nanfeng tangerines. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 2022, 27, 100674.

- Alwraikat, A.; Jaradat, A.; Marji, S. M.; Bayan, M. F.; Alomari, E. A.; Naser, A. Y.; & Alyami, M. H. Development of a Novel, Ecologically Friendly Generation of pH-Responsive Alginate Nanosensors: Synthesis, Calibration, and Characterisation. Sensors, 2023, 23(20), 8453, doi.org/10.3390/s23208453.

- Dorochesi, F.; Barrientos-Sanhueza, C.; Díaz-Barrera, Á.; Cuneo, I.F. Enhancing Soil Resilience: Bacterial Alginate Hydrogel vs. Algal Alginate in Mitigating Agricultural Challenges. Gels 2023, 9, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Sanhueza, C.; Cargnino-Cisternas, D.; Díaz-Barrera, A.; & Cuneo, I. F. Bacterial alginate-based hydrogel reduces hydro-mechanical soil-related problems in agriculture facing climate change. Polymers, 2022, 14(5), 922.

- Velázquez-Herrera, F.D.; Lobo-Sánchez, M.; Carranza-Cuautle, G.M.; Sampieri, Á.; Rocío Bustillos-Cristales, M.; Fetter, G. Novel Bio-Fertilizer Based on Nitrogen-Fixing Bacterium Immobilized in a Hydrotalcite/Alginate Composite Material. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 32220–32226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, K.; Rasheed, T.; Bilal, M. Alginate-Based Nanobiosorbents for Bioremediation of Environmental Pollutants. In Nano-Biosorbents for decontamination of water, air, and soil pollution; 2022; pp. 479–502, doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-90912-9. 0002. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.T.; Shah, L.A.; Fu, J. Highly Stretchable Natural Polymer Agar Reinforced Conductive Hydrogel for Strain Sensing and Artificial Skin Applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 145976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, C. Advances in Preparation and Biomedical Applications of Sodium Alginate-Based Electrospun Nanofibers. Gels 2025, 11, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghita Puscaselu, R.; Lobiuc, A.; Dimian, M.; Covasa, M. Alginate: From Food Industry to Biomedical Applications and Management of Metabolic Disorders. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jiang, J.; Zhe, M.; Yu, P.; Xing, F.; Xiang, Z. Alginate-Based 3D Bioprinting Strategies for Structure–Function Integrated Tissue Regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 12765–12811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pan, J.; Ma, C.; Mintah, B.K.; Dabbour, M.; Huang, L.; Dai, C.; Ma, H.; He, R. Stereo-Hindrance Effect and Oxidation Cross-Linking Induced by Ultrasound-Assisted Sodium Alginate-Glycation Inhibit Lysinoalanine Formation in Silkworm Pupa Protein. Food Chemistry 2025, 463, 141284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Parikh, H.; Saxena, A.; Mishra, B.; Tyagi, R.; Awasthi, M.K.; Madhavan, A.; Sindhu, R.; Tiwari, A. Managing Municipal Wastewater Remediation Employing Alginate-Immobilized Marine Diatoms and Silver Nanoparticles. Energy & Environment 2025, 36, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-López, A.; Sánchez-Vega, M.; Betancourt-Galindo, R.; Leal-Robles, A.I.; Pérez-Hernández, H. Foliar Application of Chitosan–Alginate and Chitosan–Maltodextrin Composites Improves Growth and Fruit Quality of ‘Anaheim Chili’ Pepper in Arid Soils. J Soils Sediments 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; El Idrissi, A.; Long, T.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L. Eco-Friendly Alginate-Urea-Fluroxypyr Hydrogel for Sustainable Agriculture: A Comprehensive Approach to Integrated Fertilizer Delivery and Weed Control. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 310, 143257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yue, T.; Cai, R.; Muratkhan, M.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z. A Green Versatile Packaging Based on Alginate and Anthocyanin via Incorporating Bacterial Cellulose Nanocrystal-Stabilized Camellia Oil Pickering Emulsions. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 249, 126134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.; Simão, A.F.; Graça, M.F.P.; Mariz, M.J.; Correia, I.J.; Ferreira, P. Dextran-Based Injectable Hydrogel Composites for Bone Regeneration. Polymers 2023, 15, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, A.; Muñana-González, S.; Lanceros-Mendez, S.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Alvarez, L.P.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L. Biodegradable Natural Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering, Controlled Release, and Soil Remediation. Polymers 2024, 16, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Jang, A.-R.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.-Y. Application of Sodium Alginate-Based Edible Coating with Citric Acid to Improve the Safety and Quality of Fresh-Cut Melon (Cucumis Melo L.) during Cold Storage. Food Sci Biotechnol 2024, 33, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Seo, J.; Kim, H.J.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, H.; Park, C.; Eom, Y. Synergistic Design of Pickering Emulsion Inks of Nanochitosan-Alginate-Beeswax for Edible Coating in Fruit Preservation. Food Hydrocolloids 2025, 167, 111462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo-Torres, C.; Estévez, M.; Sánchez-Terrón, G.; Ventanas, S.; & Morcuende, D. Alginate-based Edible Coating Impregnated with Phenolic-rich Extract from Acorns Improves Oxidative Stability and Odor Liking in Ready-to-Eat Chicken Patties. Food Science of Animal Resources, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamabadi, H.; Demirkesen, I.; Colussi, R.; Roy, S.; Tabassum, N.; de Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Bist, Y.; Kumar, Y.; Nowacka, M.; Galus, S. & Falsafi, S., R. Recent Trends in the Application of Films and Coatings Based on Starch, Cellulose, Chitin, Chitosan, Xanthan, Gellan, Pullulan, Arabic Gum, Alginate, Pectin, and Carrageenan in Food Packaging. Food Frontiers 2024, 5, 350–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbreta, U.; Andze, L.; Filipova, I.; Dortins, E. Effect of nanofibrillated cellulose on alginate and chitosan film properties as potential barrier coatings for paper food packaging. BioResources, 2024, 19(2), 3375. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Vadrale, A.P.; Singhania, R.R.; Michaud, P.; Pandey, A.; Chen, S.-J.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D. Algal Polysaccharides: Current Status and Future Prospects. Phytochem Rev 2023, 22, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Y.E.; Laitano, M.V.; Zanazzi, A.N.; Fernández-Gimenez, A.V.; Pereira, N. de los Á.; Rivero, G. Turning Fishery Waste into Aquafeed Additives: Enhancing Shrimp Enzymes Immobilization in Alginate-Based Particles Using Electrohydrodynamic Atomization. Aquaculture 2024, 587, 740846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Céspedes, F.; Villafranca-Sánchez, M.; Fernández-Pérez, M. Alginate-Bentonite-Based Hydrogels Designed to Obtain Controlled-Release Formulations of Dodecyl Acetate. Gels 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, S.; Naz, F.; Ali, F.; Smita Jyoti, R.; Fatima, A.; Khan, W.; Singh, B.R.; Naqvi, A.H.; Siddique, Y.H. Effect of Cabergoline Alginate Nanocomposite on the Transgenic Drosophila Melanogaster Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods 2018, 28, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveira-Souto, I.; Rosell-Vives, E.; Pena-Rodríguez, E.; Fernandez-Campos, F.; Lajarin-Reinares, M. Advances in Hydrophilic Drug Delivery: Encapsulation of Biotin in Alginate Microparticles. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, Û. Alginate Coating for Seed Treatment. RU Patent Application 2016121153 A, filed on October 29, 2014. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/053005060/publication/RU2016121153A?q=pn%3D RU2016121153A. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, M. In Situ Treatment of Seed in Furrow. CA Patent Application 3009097 A1, filed on December 08, 2016. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/057681754/publication/CA3009097A1?q=pn%3DC A3009097A1. [Google Scholar]

- Iida, T.; Yanagisawa, K.; Hirao, A. Agrochemical Granules with Coating. RU Patent Application 2017104637 A, filed on February 14, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/059410171/publication/RU2017104637A?q=pn%3D RU2017104637A. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q.; Chen, S.; Pei, F. Method for Producing Instant Straw Mushroom Chips by Adopting Vacuum Low-Temperature Dehydration Technology. CN Patent Application 102406161 A, filed on November 28, 2011. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/045908728/publication/CN102406161A?q=pn%3D CN102406161A. [Google Scholar]

- Jiacheng, L.; Qiang, L.; Huiqiong, Y. Method for Preparing Drug-Loading Nanocomposite through Ball-Milling Modification of Mineral Soil and Application. CN Patent Application 103039442 A, filed on January 21, 2013. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/048052489/publication/CN103039442A?q=pn%3D CN103039442A. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Fu, P.; Genxing, P. Crop Seed Coating Agent Prepared from Novel Biomass Carbon of Agricultural Wastes and Preparation Method of Coating Agent. CN Patent Application 103053244 A, filed on January 16, 2013. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/048096392/publication/CN103053244A?q=pn%3D CN103053244A. [Google Scholar]

- Genxuan, W.; Zhongji, S.; Xiaobin, O. Composite Type Antitranspirant, Its Preparation Method and Application. CN Patent Application 102626112 A, filed on March 23, 2012. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/046584644/publication/CN102626112A?q=pn%3D CN102626112A. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, L. Slow-Release Agricultural Micro-Organism Agent. CN Patent Application 108911858 A, filed on August 09, 2018. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/064404249/publication/CN108911858A?q=pn%3D CN108911858A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Zhu, H. Biochar-Based Bacillus thuringiensis Sustained-Release Microspheres and Preparation Method and Application Thereof. CN Patent Application 114027322 A, filed on November 17, 2021. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/080138110/publication/CN114027322A?q=pn%3D CN114027322A. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, L.; Geng, N. Bacillus velezensis and Application Thereof in Desert. CN Patent Application 118086120 A, filed on February 29, 2024. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/091143644/publication/CN118086120A?q=pn%3D CN118086120A. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, C. Light-Controlled Sustained-Release Pesticide Preparation and Its Preparation Method. CN Patent Application 107333759 A, filed on June 22, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/060221166/publication/CN107333759A?q=pn%3D CN107333759A. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Lin, Q.; Hu, W. Water-Suspension Nano Capsule and Preparation Method Thereof. CN Patent Application 103168773 A, filed on January 21, 2013. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/048629324/publication/CN103168773A?q=pn%3D CN103168773A. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Feng, Y.; Yu, G. Method for Reducing Pesticide Migration from Soil to Water Environment. CN Patent Application 107258772 A, filed on August 21, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/060079779/publication/CN107258772A?q=pn%3D CN107258772A. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Gu, R.; Xing, D. Making Method of Two-Layer Embedded Artificial Seeds of Orychophragmus violaceus. CN Patent Application 106134995 A, filed on June 30, 2016. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/057351105/publication/CN106134995A?q=pn%3D CN106134995A. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkova, I.; Omelchenko, A. Method of Stimulation of Germination of Wheat Seeds. RU Patent Application 2601578 C1, filed on June 25, 2015. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/057278105/publication/RU2601578C1?q=pn%3DR U2601578C1. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Chen, S. Small and Micro Seed Aggregation Method. CN Patent Application 116897643 A, filed on July 04, 2023. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/088355654/publication/CN116897643A?q=pn%3D CN116897643A. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, K.; Nakamura, K. Mulch Film Substitute for Agriculture, Method for Producing the Same and Production Kit. JP Patent Application 2008035860 A, filed on July 13, 2007. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/039171620/publication/JP2008035860A?q=pn%3DJ P2008035860A. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. Self-Repairing Agricultural Film and Preparation Process Thereof. CN Patent Application 113583416 A, filed on September 09, 2021. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/078241881/publication/CN113583416A?q=pn%3D CN113583416A. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, F.; Wang, X. Thermal Sparying Substrate and Application Method. CN Patent Application 110463565 A, filed on September 24, 2019. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/068516575/publication/CN110463565A?q=pn%3D CN110463565A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Li, C.; An, F. Sandwich Type Antibacterial Water-Retaining Agent and Preparation Method Thereof. CN Patent Application 115251071 A, filed on August 12, 2022. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/083751781/publication/CN115251071A?q=pn%3D CN115251071A. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y. Straw Biomass Based Water Retaining Agent and Preparation Method Thereof. CN Patent Application 107513139 A, filed on August 21, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/060723204/publication/CN107513139A?q=pn%3DCN107513139A. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Huang, Y.; Yang, D. Full-Biomass Sodium Alginate/Lignin Water-Retaining Slow-Release Hydrogel as Well as Preparation Method and Application Thereof. CN Patent Application 117624647 A, filed on November 01, 2023. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/090024353/publication/CN117624647A?q=pn%3DCN117624647A. [Google Scholar]

- Achintya, B.; Almeelbi, T.B.; Quamme, M. Iron-Functionalized Alginate for Phosphate and Other Contaminant Removal and Recovery from Aqueous Solutions. US Patent Application 2014260468 A, filed on March 14, 2014. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/051521176/publication/US2014260468A1?q=pn%3DUS2014260468A1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Huang, J.; Wan, Z. Fe/Titanium-Based Biomass Carbon Composite Material as Well as Preparation Method and Application Thereof. CN Patent Application 104667866 A, filed on January 29, 2015. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/053303766/publication/CN104667866A?q=pn%3DCN104667866A. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y. Preparation and Application of Floatable Magnetic Hollow Material for Removing Heavy Metal in Water and Soil. CN Patent Application 107398251 A, filed on July 25, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/060401396/publication/CN107398251A?q=pn%3DCN107398251A. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chu, D. Application of Alginate Oligosaccharide in Promotion of Bacillus Movement and Field Planting in Plant Rhizosphere. CN Patent Application 115261267 A, filed on July 18, 2022. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/083765287/publication/CN115261267A?q=pn%3DCN115261267A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, Q.; Yin, H. Method for Alleviating Toxicity of Herbicides to Crops. CN Patent Application 104798776 A, filed on January 28, 2014. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/053684341/publication/CN104798776A?q=pn%3DCN104798776A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Yinh, H.; Liu, Q. Mitigating Agent for Unrotten Organic Fertilizer Compost Harm and Application of Mitigating Agent. CN Patent Application 108147885 A, filed on December 04, 2016. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/062470065/publication/CN108147885A?q=pn%3DCN108147885A. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, J. Bidirectional Crosslinking Intelligent Fruit Cracking Repairing Film Agent as Well as Preparation Method and Use Method Thereof. CN Patent Application 115433039 A, filed on August 23, 2022. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/084243888/publication/CN115433039A?q=pn%3DCN115433039A. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Ling, H.; Yuan, W. Composite Microbial Agent and Application Thereof in Preservation and Fresh-Keeping of Agricultural Products. CN Patent Application 118303461 A, filed on December 29, 2023. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/091725233/publication/CN118303461A?q=pn%3DCN118303461A. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D. Film-Coating and Fresh-Keeping Method of Pomegranate. CN Patent Application 107318970 A, filed on July 28, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/060227696/publication/CN107318970A?q=pn%3DCN107318970A. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D. Fresh Keeping Method for Longan. CN Patent Application 107494717 A, filed on July 28, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/060689051/publication/CN107494717A?q=pn%3DCN107494717A. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, Y. Preparation Method of Environment-Friendly Biomass Packaging Material. CN Patent Application 107903646 A, filed on November 10, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/061844582/publication/CN107903646A?q=pn%3DCN107903646A. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, L. Method of Quickly Freezing Heracleum Moellendorffii Hance. CN Patent Application 110279083 A, filed on July 23, 2019. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/068023840/publication/CN110279083A?q=pn%3DCN110279083A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Cheng, Z.; Gu, X. Method for Inhibiting Browning of Agaricus bisporus. CN Patent Application 118805821 A, filed on August 16, 2024. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/093065001/publication/CN118805821A?q=pn%3DCN118805821A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. Preparation Method of Chrysanthemum Morifolium ramat Scented Tea with Low Pesticide Residues and Good Ornamental Effects. CN Patent Application 107173493 A, filed on May 27, 2017. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/059835377/publication/CN107173493A?q=pn%3DCN107173493A. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. Method for Reducing Microbiological Contamination Rate by Encapsulating Explant by Virtue of Coating Film Containing Fungicide in Plant Tissue Culture. CN Patent Application 104521762 A, filed on January 23, 2015. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/052837546/publication/CN104521762A?q=pn%3DCN104521762A. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. Method for Reducing Explant Browning by Encapsulating Explants by Using Film-Coating Agent Containing Anti-Browning Agent in Plant Tissue Culture. CN Patent Application 104521763 A, filed on January 23, 2015. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/052837547/publication/CN104521763A?q=pn%3DCN104521763A. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. Coating Encapsulation Culture Method for Improving Explant Survival Rate of Plant Tissue Culture. CN Patent Application 104604681 A, filed on January 23, 2015. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/053139557/publication/CN104604681A?q=pn%3DCN104604681A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, G.; Liu, D. Soilless Culture Substrate for Organic Vegetables and Preparation Method Thereof. CN Patent Application 118435848 A, filed on May 21, 2024. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/092319381/publication/CN118435848A?q=pn%3DCN118435848A. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Soilless Culture Substrate for Tomato and Preparation Method Thereof. CN Patent Application 106613823 A, filed on October 31, 2016. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/058821500/publication/CN106613823A?q=pn%3DCN106613823A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Yu, P.; Zhang, Y. Modularized Indoor Agricultural Planting System Based on Gel Matrix. CN Patent Application 113057092 A, filed on March 26, 2021. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/076563634/publication/CN113057092A?q=pn%3DCN113057092A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Sheng, L.; Xu, J. Conjugated Polymer, Hydrogel Film Fluorescence Sensor, Portable Intelligent Sensing Platform and Preparation Method Thereof. CN Patent Application 119463127 A, filed on November 11, 2024. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/076563634/publication/CN113057092A?q=pn%3DCN113057092A. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Xiong, F.; Cui, L. Preparation Method and Application of Acetylcholin Esterase Electrochemical Biosensor. CN Patent Application 103412020 A, filed on March 18, 2013. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/049605046/publication/CN103412020A?q=pn%3DCN103412020A. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, H.; Lai, Y. Anti-Fog Greenhouse Film Coating Liquid, Agricultural Anti-Fog Greenhouse Film and Preparation Method and Application of Agricultural Anti-Fog Greenhouse Film. CN Patent Application 117986939 A, filed on October 28, 2022. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/090892078/publication/CN117986939A?q=pn%3DCN117986939A. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, D.-H.; Rust, M.; Hoddle, M. Biodegradable Bait Station for Liquid Ant Bait. US Patent Application 10729121 B2, filed on July 27, 2015. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/055163892/publication/US10729121B2?q=pn%3DUS10729121B2. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Chen, H.; Qu, H. Parasitic Wasp Attractant for Tea Garden. CN Patent Application 117158420 A, filed on August 17, 2023. Available: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/088930963/publication/CN117158420A?q=pn%3DCN117158420A. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, D.; He, H.; Zou, J.; Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C. Immobilization of Zirconium-Modified Activated Carbon in an Alginate Matrix for the Removal of Atrazine: Preparation, Performances and Mechanisms. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2024, 35, 103699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceković, M.; Jurić, S.; Vlahoviček-Kahlina, K.; Martinko, K.; Šegota, S.; Marijan, M.; Krčelić, A.; Svečnjak, L.; Majdak, M.; Nemet, I.; et al. Novel Zinc/Silver Ions-Loaded Alginate/Chitosan Microparticles Antifungal Activity against Botrytis Cinerea. Polymers 2023, 15, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Barrera, M.; Izquierdo-García, L.F.; Gómez-Marroquín, M.; Santos-Díaz, A.; Uribe-Gutiérrez, L.; Moreno-Velandia, C.A. Hydrogel Capsules as New Delivery System for Trichoderma Koningiopsis Th003 to Control Rhizoctonia Solani in Rice (Oryza Sativa). World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 40, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinelli, N.; Sabando, C.; Rodríguez-Llamazares, S.; Bouza, R.; Castaño, J.; Valverde, J.C.; Rubilar, R.; Frizzo, M.; Recio-Sánchez, G. Sodium Alginate-g-Polyacrylamide Hydrogel for Water Retention and Plant Growth Promotion in Water-Deficient Soils. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 222, 119759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Peng, H.; Ye, X.; Kong, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, F.; Meni, B.-H.; Lei, Z. High Salt Tolerance Hydrogel Prepared of Hydroxyethyl Starch and Its Ability to Increase Soil Water Holding Capacity and Decrease Water Evaporation. Soil and Tillage Research 2022, 222, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Montiel, L.G.; Chiquito Contreras, C.J.; Murillo Amador, B.; Vidal Hernández, L.; Quiñones Aguilar, E.E.; Chiquito Contreras, R.G. Efficiency of Two Inoculation Methods of Pseudomonas Putida on Growth and Yield of Tomato Plants. Journal of soil science and plant nutrition 2017, 17, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregonezi, B.F.; Pereira, A.E.S.; Ferreira, J.M.; Fraceto, L.F.; Gomes, D.G.; Oliveira, H.C. Seed Priming with Nanoencapsulated Gibberellic Acid Triggers Beneficial Morphophysiological and Biochemical Responses of Tomato Plants under Different Water Conditions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Dong, R.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Chen, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia Crassipes) Biodegradable Mulch Films. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 222, 119548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, E.I.; Hamed, L.M.M.; El-Refaie, E.M.S.A.; Samak, R.M.; Habashy, N.R. Fostering Sustainable Potato Prod: Enhancing Quality & Yield via Potassium & Boron Applications. International Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources 2024, 51, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clúster (color code) |

Top 5 keywords (ocurrences , links, TLS)* |

Analysis |

|---|---|---|

Red |

encapsulation (18, 29, 46), microencapsulation (9, 16, 24), temperature (8, 15, 17), rhizobacteria (6, 16, 21), biological control (4, 12, 16). |

The keywords reflect the role of alginate in the encapsulation and controlled release of microorganisms and bioactive compounds. |

Green

|

nanoparticles (7, 13, 17), microalgae (4, 11, 12) survival (4, 8, 11), biostimulants (4, 5, 6), inoculants (3, 7, 8) |

The keywords are closely related to the red cluster, emphasizing alginate as a matrix for microbial inoculants |

Blue

|

biodegradation (12, 16, 26), degradation (9, 13, 20), immobilization (8, 17, 22), bioremediation (4, 11, 13), toxicity (3, 8, 9) |

The keywords highlight the applications of alginate in the remediation of agricultural soils and water. |

Yellow

|

soil (6, 10, 10), stability (5, 5, 5), water retention (3, 7, 7), fertilizer (3, 5, 5), superabsorbent (3, 3, 3) |

The keywords are associated with soil amendments, water retention, and nutrient management |

Purple |

plant growth (11, 17, 24), hydrogels (8, 13, 15), plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) (6, 11, 15), matrix (3, 5, 5), controlled release (3, 2, 2) |

The keywords describe a transversal cluster linked to plant growth promotion. |

Light blue

|

growth-promoting bacteria (6, 16, 19), adsorption (8, 9, 12) beads (7, 17, 23), removal (6, 9, 12), slow release (5, 9, 11) |

The keywords also describe a transversal cluster related to pollutant removal. |

| Category | Subcategory | In vitro tests | Semi controlled conditions tests | Field trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation and controlled release of microorganisms and agrochemicals | Encapsulation and controlled release of microorganisms and spores | 15* | 30 | 3 |

| Encapsulation and controlled release of fertilizers, bioactive compounds, and similar substances | 33 | 33 | 12 | |

| Encapsulation and controlled release of seeds | 2 | 6 | 3 | |

| Treatment of agricultural soil and water |

Soil amendments and improvements | 2 | 11 | 9 |

| Hydrogels for water absorption and retention | 18 | 12 | 4 | |

| Bioremediation of agricultural soils and water | 22 | 2 | 3 | |

| Fertilizers made from algae extracts or alginate oligosaccharides | 2 | 7 | 2 | |

| Post-harvest treatments, biodegradable packaging and containers for agricultural products |

Edible coatings | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Biodegradable containers and packaging |

5 | - | 2 | |

| Other post-harvest treatments |

0 | - | 1 | |

|

In vitro and soilless cultivation |

In vitro cultivation | 3** | - | - |

| Substrates for soilless cultivation | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Other applications | Agricultural formulations with alginate (unspecified function) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Others | 8 | 1 | 8 |

| IPC codes | Description | Mentions |

|---|---|---|

| C05G 3/00 | Mixtures of one or more fertilizers with non-fertilizer additives. | 80 |

| C05G 3/80 | Mixtures of one or more fertilizers with non-fertilizer additives (...): Soil conditioners. | 56 |

| A01N 43/16 | Biocides, pest repellants or attractants, or plant growth regulators, containing heterocyclic compounds (...) having oxygen as a ring hetero atom. | 43 |

| A01P 7/04 | Insecticides. | 33 |

| A01N 43/90 | Biocides, pest repellants or attractants, or plant growth regulators, containing heterocyclic compounds (...) containing several defining heterocycles condensed among themselves or with a common carbocyclic system. | 32 |

| A01N 25/28 | Biocides, pest repellants or attractants, or plant growth regulators, characterized by their form, inactive ingredients, or methods of application; Substances reducing the noxious effects of the active ingredients on organisms other than pests (...) microcapsules. | 19 |

| A01N 63/22 | Biocides, pest repellants or attractants, or plant growth regulators, containing microorganisms, viruses, microscopic fungi, animals, or substances produced by, or obtained from, microorganisms, viruses, microscopic fungi, or animals, e.g. enzymes or fermentation products (...) Bacillus. | 19 |

| C12N 1/20 | Microorganisms, e.g. protozoa; Compositions comprising them; preparation of medicinal compositions containing bacterial antigens or antibodies; Processes for culturing or preserving microorganisms, or compositions containing them; Processes for the preparation or isolation of a composition containing a microorganism; Culture media (...) Bacteria. | 18 |

| A01P 21/00 | Plant growth regulators. | 18 |

| A01C 1/06 | Apparatus, or methods of use thereof, for testing or treating grain, roots, or the like, prior to sowing or planting (...) Coating or dressing of seeds. | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).