Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

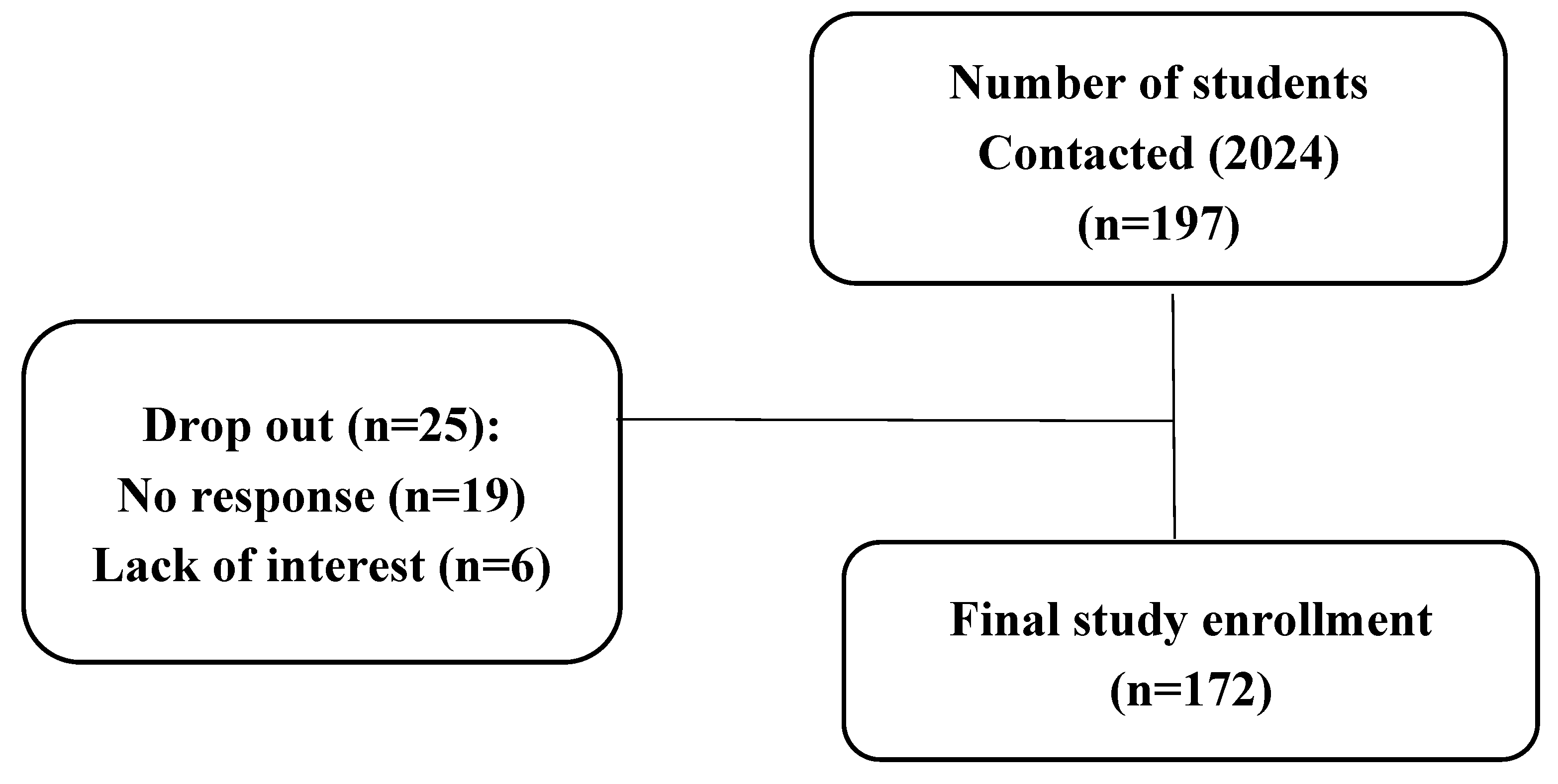

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample and Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Features

3.2. Low Back Pain Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implication

4.2. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

References

- Zhang, C.; Qin, L.; Yin, F.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, S. Global, regional, and national burden and trends of Low back pain in middle-aged adults: analysis of GBD 1990–2021 with projections to 2050. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2024 Nov 7;25(1):886.

- Ferreira, M.L., De Luca, K., Haile, L.M., Steinmetz, J.D., et al. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet Rheumatology, 2023, 5(6), pp.e316-e329.

- Al Amer, H.S. Low back pain prevalence and risk factors among health workers in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of occupational health, 2020, 62(1), p.e12155.

- Hoy, D., Bain, C., Williams, G., March, L., et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis & rheumatism, 2012, 64(6), pp.2028-2037.

- Alshehri, M.M., Alqhtani, A.M., Gharawi, S.H., Sharahily, R.A., et al. Prevalence of lower back pain and its associations with lifestyle behaviors among college students in Saudi Arabia. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2023, 24(1), p.646.

- Daldoul, C., Boussaid, S., Jemmali, S., Rekik, S., Sahli, H., Cheour, E. and Elleuch, M. Low back pain among medical students: prevalence and risk factors. 2020. AB0962.

- AlShayhan, F.A. and Saadeddin, M. Prevalence of low back pain among health sciences students. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology, 2018, 28(2), pp.165-170.

- Vujcic, I., Stojilovic, N., Dubljanin, E., Ladjevic, N., Ladjevic, I. and Sipetic-Grujicic, S. Low Back pain among medical students in Belgrade (Serbia): a cross-sectional study. Pain Research and Management, 2018 (1), p.8317906.

- Aggarwal, N., Anand, T., Kishore, J. and Ingle, G.K. Low back pain and associated risk factors among undergraduate students of a medical college in Delhi. Education for health, 2013, 26(2), pp.103-108.

- Falavigna, A., Teles, A.R., Mazzocchin, T., de Braga, G.L., et al. Increased prevalence of low back pain among physiotherapy students compared to medical students. European Spine Journal, 2011, 20(3), pp.500-505.

- Hafeez, K., Memon, A.A., Jawaid, M., Usman, S., et al. Back pain–are health care undergraduates at risk?. Iranian journal of public health, 2013, 42(8), p.819.

- Nordin, N.A.M., Singh, D.K.A. and Kanglun, L. Low back pain and associated risk factors among health science undergraduates. Sains Malaysiana, 2014, 43(3), pp.423-428.

- Yucel, H.; Torun, P. Incidence and Risk Factors of Low Back Pain in Students Studying at a Health University. Bezmialem Sci, 2016, 4: 12-18.

- Crawford, R.J., Volken, T., Schaffert, R. and Bucher, T. Higher low back and neck pain in final year Swiss health professions’ students: worrying susceptibilities identified in a multi-centre comparison to the national population. BMC Public Health, 2018, 18(1), p.1188.

- Isa, S.N.I., Kamalruzaman, N.S.A., Sabri, T.A.T. and Zamri, E.N. Associated Factors of Lower Back and Neck Pain Among Health Sciences Undergraduate Students in a Public University in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences, 2022, 18.

- Algarni, A.D.; Al-Saran, Y.; Al-Moawi, A.; Bin Dous, A.; Al-Ahaideb, A.; Kachanathu, S.J. The prevalence of and factors associated with neck, shoulder, and low-back pains among medical students at university hospitals in Central Saudi Arabia. Pain Res. Treat. 2017, 1, 1235706.

- Feyer, A.M.; Herbison, P.; Williamson, A.M. The role of physical and psychological factors in occupational low back pain: A prospective cohort study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2000, 57, 116–120.

- O’Sullivan, P.; Smith, A.; Beales, D.; Straker, L. Understanding adolescent low back pain from a multidimensional perspective: implications for management. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2017 Oct;47(10):741-51.

- Abbas, J.; Yousef, M.; Hamoud, K.; Joubran, K. Low Back Pain Among Health Sciences Undergraduates: Results Obtained from a Machine-Learning Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(6):2046. [CrossRef]

- Kuorinka, I.; Jonsson, B.; Kilbom, A. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl. Ergon. 1987, 18, 233–237.

- Jessor, R.; Turbin, M.S.; Costa, M.F. Survey of Personal and Social Development at CU; Institute of Behavioral Sciences, University of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2003; Volume 19, p. 2016. Available online: http://www.colorado.edu/ibs/jessor/questionnaires/ questionnaire_spsd2.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Thompson, W.R.; Gordon, N.F.; Pescatello, L.S. American College of Sport Medicine. In ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 9th ed.; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014.

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2952.

- Dionne, C.E.; Dunn, K.M.; Croft, P.R. A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine 2008, 33, 95–103.

- Abbas, J.; Hamoud, K.; Jubran, R.; Daher, A. Has the COVID-19 outbreak altered the prevalence of low back pain among physiotherapy students? J Am Coll Health. 2023 Oct;71(7):2038-2043. PMID: 34353241. [CrossRef]

- Nyland, L.J.; Grimmer, K.A. Is undergraduate physiotherapy study a risk factor for low back pain? A prevalence study of LBP in physiotherapy students. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003 Oct 9;4:22. PMID: 14536021; PMCID: PMC270026. [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.Y.H., Warasna, H.J.M., Awad, B.Y.H., Shaaban, M.E. Prevalence of lower back pain and its associations with lifestyle behaviors among university students in the West Bank, Palestine: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Medicine, 2025, 57(1), p.2522974.

- Feleke, M., Getachew, T., Shewangizaw, M. et al. Prevalence of low back pain and associated factors among medical students in Wachemo University Southern Ethiopia. Sci Rep , 2024, 14, 23518. [CrossRef]

- Alrabai, H.M., Aladhayani, M.H., Alshahrani, S.M., Alwethenani, Z.K., Alsahil, M.J. and Algarni, A.D. Low back pain prevalence and associated risk factors among medical students at four major medical colleges in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Nature and Science of Medicine, 2021, 4(3), pp.296-302.

- Behairy, M., Odeh, S., Alsourani, J., Talic, M., et al. Prevalence of Lower Back Pain (LBP) and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Alfaisal University Medical Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. In Healthcare 2025, June, p. 1490. MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, K.; Williams, M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Appl Ergon. 2000 Aug;31(4):343-60. PMID: 10975661. [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, A.; Yücel, B.; Ozyalçn, S.N.; Bayraktar, B.; et al. The frequency and associated factors of low back pain among a younger population in Turkey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 Jul 15;29(14):1567-72. PMID: 15247580. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, C., Salvi, C.S., Nisihara, R. et al. Low back pain in Brazilian medical students: a cross-sectional study in 629 individuals. Clin Rheumatol 38, 939–942 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sany, S.A.; Tanjim, T.; Hossain, M.I. Low back pain and associated risk factors among medical students in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. F1000Res. 2021 Jul 30;10:698. PMID: 35999897; PMCID: PMC9360907. [CrossRef]

- Amelot, A.; Mathon, B.; Haddad, R.; Renault, M.C.; Duguet, A.; Steichen, O. Low Back Pain Among Medical Students: A Burden and an Impact to Consider! Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019 Oct 1;44(19):1390-1395. PMID: 31261281. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Acharya, A.S.; Chauhan, R.; Acharya, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in 1,355 Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Asian Spine J. 2017 Aug;11(4):610-617. Epub 2017 Aug 7. PMID: 28874980; PMCID: PMC5573856. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zou, C.; Guo, W.; Han, F.; Fan, T.; Zang, L.; Huang, G. Global burden of low back pain and its attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2021: a comprehensive analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Front Public Health. 2024 Nov 13;12:1480779. [CrossRef]

- Bizzoca, D.; Solarino, G.; Pulcrano, A.; Brunetti, G.; et al. Gender-Related Issues in the Management of Low-Back Pain: A Current Concepts Review. Clin Pract. 2023 Oct 30;13(6):1360-1368. [CrossRef]

- Dev, R.; Raparelli, V.; Bacon, S.L.; Lavoie, K.L.; Pilote, L.; Norris, C.M.; iCARE Study Team. Impact of biological sex and gender-related factors on public engagement in protective health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional analyses from a global survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059673.

- Nielsen, M.W.; Stefanick, M.L.; Peragine, D.; Neilands, T.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Pilote, L.; Prochaska, J.J.; Cullen, M.R.; Einstein, G.; Klinge, I.; et al. Gender-related variables for health research. Biol. Sex Differ. 2021, 12, 23.

- Fillingim, R.B.; King, C.D.; Ribeiro-Dasilva, M.C.; Rahim-Williams, B.; Riley III, J.L. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009 May;10(5):447-85. PMID: 19411059; PMCID: PMC2677686. [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.Y.L; Chan, L.L.Y; Lo, C.W.T; Chan, W.W.Y.; et al. Prevalence/Incidence of Low Back Pain and Associated Risk Factors Among Nursing and Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. First Published: 25 January 2021.

- Wami, S.; Mekonnen, T.; Yirdaw, G.; Abere, G. Musculoskeletal problems and associated risk factors among health science students in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J. Public Health. 2020;29(2):1-7.

- Menzel, N.; Feng, D.; Doolen, J. Low Back Pain in Student Nurses: Literature Review and Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2016 May 13;13:/j/ijnes. PMID: 27176750. [CrossRef]

- Kanchanomai, S.; Janwantanakul, P.; Pensri, P.; Jiamjarasrangsi, W. Risk factors for the onset and persistence of neck pain in undergraduate students: 1-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011 Jul 15;11:566. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.; O’Sullivan, P.B.; Burnett, A. Identification of modifiable personal factors that predict new-onset low back pain: a prospective study of female nursing students. Clin J Pain. 2010, 26, 275-283.

- Jensen, J.N.; Holtermann, A.; Clausen, T.; Mortensen, O.S.; et al. The greatest risk for low-back pain among newly educated female health care workers; body weight or physical work load? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012 Jun 6;13:87. [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.T.; Macfarlane, G.J. Predicting persistent low back pain in schoolchildren: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Oct 15;61(10):1359-66. [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%)/ or mean ± SD |

| Male Female |

41 (23.8) 131 (76.2) |

| Mean age (year) | 25.1 ± 3.5 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 4.3 |

| Physical activity | 101 (58.7) |

| Department: Nursing Physical therapy Medical Lab Emergency Medical Services |

71 (41.3) 39 (22.7) 33 (19.2) 29 (16.9) |

| N (%) | |

| 1-year LBP: 1. Frequency of LBP:

3. Seeking-care 4. Medication consumption |

40 (23.3) 46 (26.7) 35 (20.3) 51 (29.7) 48 (27.9) 38 (22.1) 43 (25) |

| 1-month LBP | 84 (48.8) |

| 1-month functional disability | 34 (19.8) |

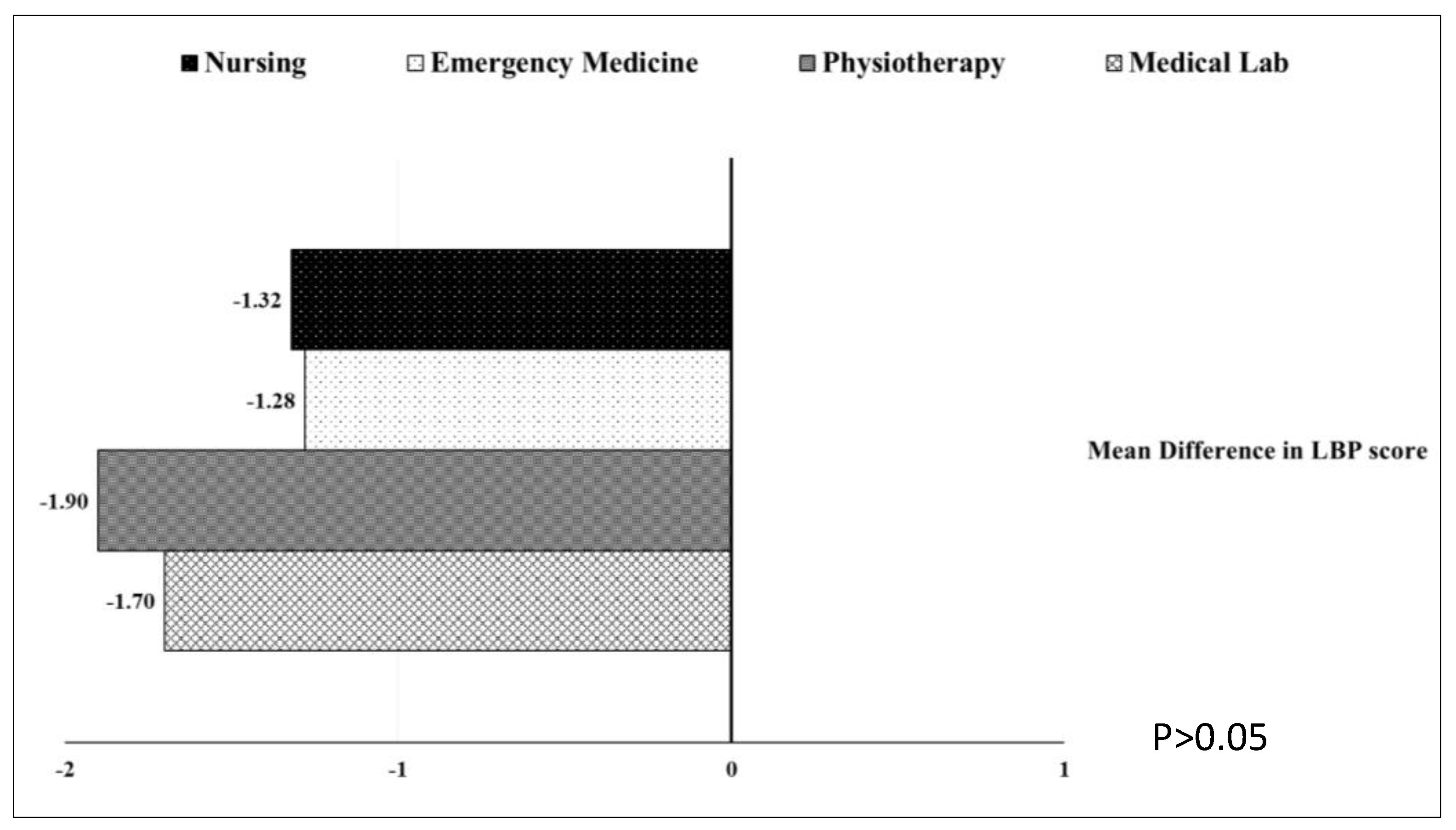

| Period | Mean | SD | T | P | Cohen’s d | |

| 1-year LBP Score | Pre | 3.26 | 0.812 | -11.25 | <0.001 | 0.859 |

| Post | 1.74 | 1.558 |

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | P |

| Department | .892 | ||

| Medical Lab (reference) | - | - | - |

| Physiotherapy | 1.19 | [0.47, 2.98] | .715 |

| Emergency Medicine | 0.81 | [0.31, 2.10] | .663 |

| Nursing | 1.19 | [0.43, 3.31] | .737 |

| Gender (Male) | 0.25 | [0.10, 0.62] | .003* |

| Physical activity pre (Yes) | 0.88 | [0.43, 1.81] | .723 |

| Daily continuously sitting (> 5 hr) | 0.62 | [0.30, 1.28] | .194 |

| Daily average sitting (> 8hr) | 0.61 | [0.29, 1.31] | .206 |

| LBP history pre (Yes) | 2.06 | [0.92, 4.59] | .077 |

| Hospitalization history pre (Yes) | 0.86 | [0.12, 5.96] | .878 |

| Disability history pre (Yes) | 0.82 | [0.36, 1.89] | .645 |

| Seeking care history pre (Yes) | 1.95 | [0.61, 6.29] | .261 |

| Medication use pre (Yes) | 1.01 | [0.37, 2.72] | .991 |

| Stress due to family pre (Yes) | 0.66 | [0.29, 1.50] | .324 |

| Stress due to personal life pre (Yes) | 0.57 | [0.14, 2.30] | .432 |

| Stress due to social life pre (Yes) | 1.19 | [0.55, 2.57] | .649 |

| Nagelkerke R² = .19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).