Introduction

The Korean Wave (Hallyu; 한류; 韓流) refers to the transnational cultural phenomenon marked by the dramatic rise in the global popularity and influence of South Korean popular culture since the 1990s. Beginning with Korean pop songs, dramas, and films, it has since sparked enthusiastic interest in other Korean cultural products, including webtoons, cosmetics, cuisine, tourism, and Korean language learning (Cruz, 2019; Jung et al., 2022; Looney & Lusin, 2018; Oh & Park, 2012; Ono & Kwon, 2013). Since the mid-2010s, digital and social media platforms like YouTube, Netflix, and TikTok have further facilitated the spread of Korean cultural products and reshaped global cultural landscapes (Jin, 2023; Jang & Song, 2017; Lee, 2020).

Notably, the widespread embrace of Korean popular culture across Western societies—particularly in the United States—represents an unprecedented moment in terms of the visibility and cultural influence of Asians in mainstream media and society. Given the historical context of racial discrimination and marginalization around Asians in the United States, Hallyu offers more than entertainment; it actively reconfigures prevailing narratives of Asian identity, providing new avenues for its affirmation, expression, and acceptance in broader social and cultural discourse. Asian individuals in the United States have historically faced invisibility and exclusion, often being perceived as perpetual foreigners or passive, hardworking “model minorities” (Koo, 2021; Suspitsyna, 2021).

There is little research on the lived experiences of Asian international faculty in teacher education programs in the United States—a field largely dominated by a monolingual, white, middle-class, female teaching force. International faculty and faculty of color in U.S. higher education often receive less institutional recognition and lower teaching evaluations due to linguistic and cultural differences (Subtirelu, 2015). Deficit-based perspectives persist toward international faculty whose first language is not English, especially within teacher education (Han et al., 2025). These perspectives underscore a mismatch between a homogeneous teaching workforce and increasingly diverse student populations.

This study uses a collaborative autoethnographic approach to explore how two Korean transcultural teacher educators—one a university faculty member and the other a doctoral student instructor—engage with Hallyu to reframe their cultural identities through a postcolonial lens, challenging an embodied sense of inferiority (Fanon, 1952/1986) and internalized Western Orientalist discourse (Said, 1978) and by recognizing the assets they possess. Although interest in Hallyu is growing, scholarly research on the phenomenon remains in its early stages and lacks a solid empirical and theoretical framework to support comprehensive academic inquiry—particularly through the lens of postcolonialism (Park, 2025). Existing studies have largely originated from Western academic institutions, particularly within media studies, international relations, and marketing, focusing on the global dissemination of Korean cultural products and the key factors driving their international success (Cruz, 2019; Jung et al., 2022). Much of this research explores how Hallyu is received in various countries, often through a managerial lens (Khiun, 2013; Lidzhieva, 2021; Lie, 2015; Spetiani et al., 2022). However, the emphasis has predominantly been on external audiences, media content, and consumer behavior, with limited attention paid to how Koreans themselves—especially Korean teacher educators—interpret and engage with Hallyu in both personal and professional contexts within the United States.

Both authors are bilingual, have taught in elementary schools in Korea, and are currently teaching in U.S.-based teacher preparation programs with a focus on multilingual, multicultural education or literacy. Through shared reflection and narrative, we examine how our engagement with Hallyu influences our sense of self, cultural identities, and shapes more inclusive educational practices. The driving research questions of this study are as follows:

How does engagement with the Korean Wave (Hallyu) influence the identity development of Korean transnational teacher educators in their personal and professional lives?

In what ways do Korean transnational teacher educators integrate their cultural assets, shaped by Hallyu, into their teaching practices in American teacher preparation programs?

Literature Review

The Korean Wave: A Brief Overview

The Korean Wave (Hallyu; 한류; 韓流) refers to the transnational circulation of South Korean popular culture—including music, television dramas, films, webtoons, beauty products, and food—which has grown from a regional phenomenon in East Asia to a mainstream global presence. Although South Korea’s population is about 51.74 million (Statistics Korea, 2023), it is estimated that the number of Hallyu community members reaches over 156 million people across the globe (Molina & Yoon, 2022; Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Korea Foundation, 2022).

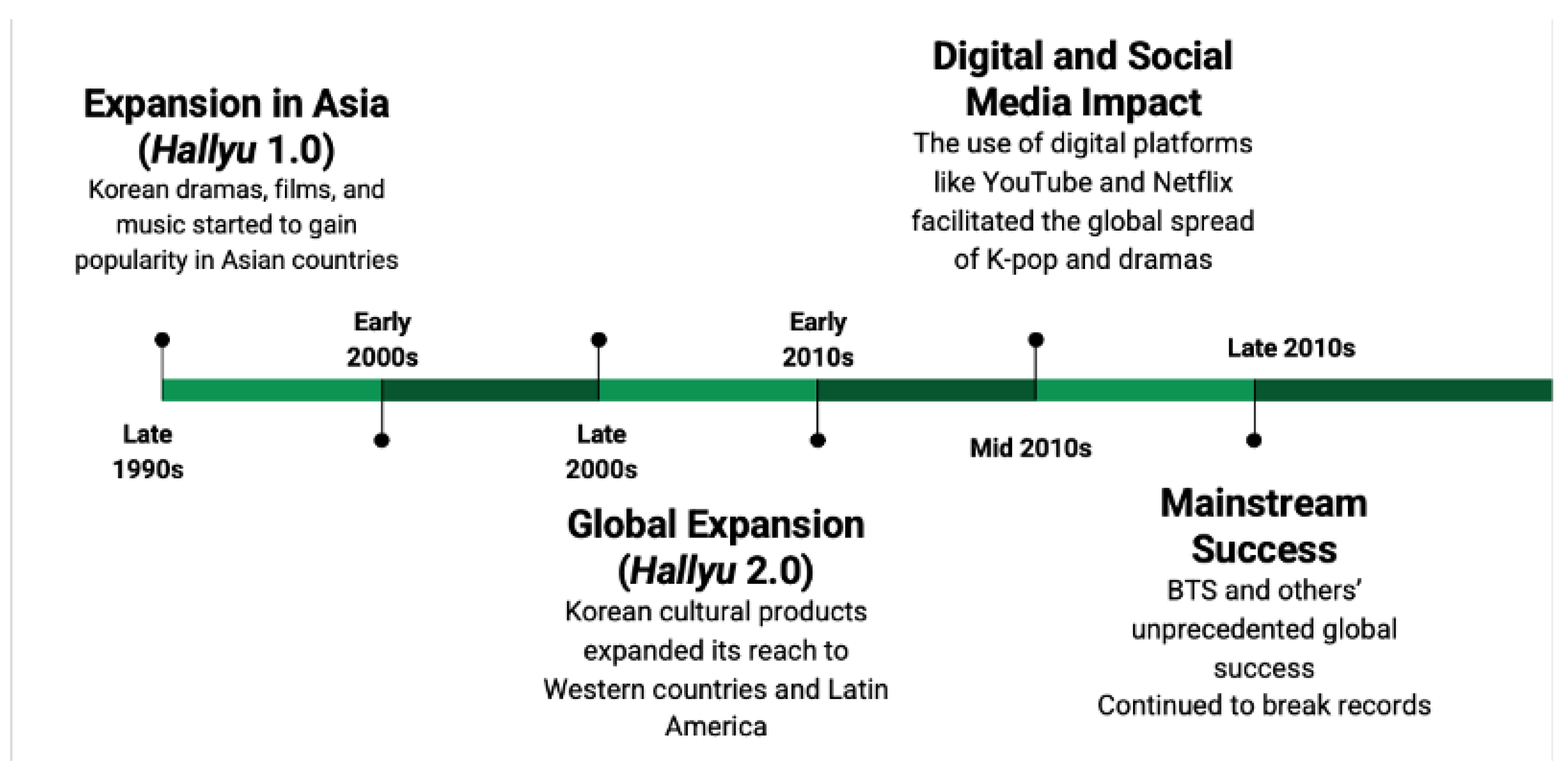

Figure 1.

Timeline of the development of the Korean Wave.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the development of the Korean Wave.

Emerging in the late 1990s and early 2000s through television dramas and early K-pop acts, Hallyu first gained momentum (Joo, 2011; Lie, 2012) as the South Korean government promoted cultural industries as part of its national development strategy (Hong, 2014). By the late 2000s, Hallyu transcended Asia into global markets, marking what Jin and Yoon (2016) termed “Hallyu 2.0,” characterized by participatory fan practices and digital platforms. The viral success of PSY’s “Gangnam Style (강남스타일)” in 2012 symbolized this shift (Oh & Lee, 2013), and the rise of social media platforms further accelerated global dissemination.

Since the 2010s, K-pop groups such as BTS and Blackpink and films like Parasite and series like Squid Game have achieved unprecedented global acclaim, winning major awards and shaping cultural conversations. Beyond entertainment, Hallyu has boosted interest in the Korean language (Gibson, 2015), food, and beauty products, while significantly contributing to South Korea’s economy- bringing an estimated 5 billion dollars annually (Smith, 2021). Korean cultural products function not only as entertainment but also as powerful sites of identity formation and soft cultural diplomacy (Park, 2025). In U.S. universities, for example, K-pop dance has been incorporated into liberal arts curricula, serving as a space for critical inquiry and identity exploration (Park, 2025). These developments illustrate how non-Western media can assert global cultural relevance through digital innovation and participatory fan cultures, offering a powerful model of soft power in the post-globalization era.

Experiences and Identities of International Teacher Educators

The experiences and identity formation of international teacher educators have received increasing scholarly attention in recent decades, especially as teacher education programs have become more globalized and diverse. International teacher educators often face marginalization within predominantly white, monolingual, and Western-centric teacher education environments (Cho, 2010; Han et al., 2025; Kang et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023; Phillion et al., 2009). Their educational backgrounds and culturally situated pedagogical approaches are frequently perceived as deficits rather than valuable assets (Faez, 2011; Han et al., 2025). Such marginalization can lead to feelings of invisibility, professional insecurity, and internal conflicts surrounding identity.

Prior research has shown how these educators negotiate multiple and sometimes conflicting identities—such as racialized immigrant, language learner, and critical educator—within their institutional contexts (Trent, 2011; Yuan, 2019). These negotiations are shaped by institutional norms, student perceptions, and the educators’ personal histories. Although international educators may be perceived as lacking dominant forms of cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1991), international teacher educators contribute uniquely to the preparation of culturally competent teachers. Their presence and pedagogical approaches challenge monocultural norms and encourage students to critically examine privilege, culture, and global perspectives (Myles et al., 2006; He & Cooper, 2009).

While existing research offers valuable insights into the experiences and identities of international teacher educators, it largely centers on broad issues of marginalization, identity negotiation, and cultural capital within Western teacher education contexts. However, there is a noticeable gap in exploring how specific transnational cultural phenomena—such as the Korean Wave (Hallyu)—shape the identities, pedagogical practices, and resistance strategies of Korean teacher educators in these settings. Our research addresses this gap by focusing explicitly on how engagement with Hallyu as a cultural and affective resource informs the identity formation and professional practices of Korean teacher educators navigating complex transnational and institutional landscapes. This focus highlights new dimensions of cultural negotiation and identity that extend beyond existing frameworks, emphasizing the role of popular culture as a site of empowerment and critical engagement.

Post-colonial Perspective

This collaborative autoethnography (CAE) is informed by postcolonial theory, particularly the works of Edward Said (1978), Frantz Fanon (1952/2008), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1986), Ashcroft et al. (1989), and Homi Bhabha (1994). Postcolonialism critiques not only the historical realities of colonization but also its ongoing cultural, political, and epistemic effects. As Ashcroft et al. (1989) explained, the term “post-colonial” encompasses all cultures affected by the imperial process, from the moment of colonization to the present, emphasizing its enduring legacy. While anti-colonialism focuses on overt resistance to colonial regimes, postcolonialism examines how structures of domination persist beyond formal independence, including in global systems such as media, education, and language.

Said’s (1978) Orientalism exposes how Western discourse constructs the "Orient" as irrational, exotic, and inferior—a representation that legitimizes domination and becomes internalized by those it targets. Fanon (1952/2008) analyzed the psychological consequences of colonization, describing how the colonized internalize the colonizer’s language, values, and worldview, leading to a deep-seated sense of inferiority, alienation, and identity fragmentation. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1986) emphasized the importance of language in resisting imperialism, arguing that the continued dominance of colonial languages like English perpetuates cultural alienation. He called for writing and teaching in indigenous languages as acts of cultural reclamation. Bhabha (1994) introduced the concept of hybridity to complicate binary notions of colonizer and colonized. He theorized a “third space” of negotiation where identities are fluid, hybrid, and ambivalent, destabilizing colonial authority. Similarly, Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin (1989) emphasized “writing back” as a means for postcolonial voices to challenge and subvert Eurocentric narratives, reclaiming voice and identity.

As Korean teacher educators in the United States, we draw on these frameworks to examine how we have internalized Orientalist representations and onto-epistemologies. Postcolonial theory serves both as a critical lens and a liberating tool, helping us interrogate our lived experiences and identity formation in relation to Hallyu. It also allows us to reflect on how hybrid identities are shaped within and against the forces of cultural imperialism, offering possibilities for resistance, redefinition, and healing.

Method

Collaborative autoethnography is a qualitative research method in which researchers collectively gather, analyze, and interpret autobiographical narratives, reflecting both individually and collectively on their lived experiences (Chang et al., 2016; Ellis et al., 2011; Hughes, 2008). We approach collaborative autoethnography as a research genre that enables us to “look inward into our identities, thoughts, feelings and experiences—and outward into our relationships, communities and cultures” (Adams et al., 2015, p. 46). By situating ourselves within broader cultural contexts, we explore the intersections between the personal and the collective, the individual and the sociocultural. This method allows us to critically examine how our identities as Korean teacher educators are shaped through our engagement with Hallyu.

Through dialogic collaboration grounded in our lived experiences of Hallyu, we interrogate dominant discourses and institutional ideologies, drawing particular inspiration from post-colonial theories. We recognize the researcher not as a detached observer but as a cultural subject embedded in and shaped by broader structures of power and meaning. As Hughes et al. (2012) suggested, the researcher becomes “a site of cultural inquiry within a cultural context,” which enables us to challenge the binary constructions of self and others that often underpin traditional empirical research (p. 210). Thus, collaborative autoethnography becomes a transformative process through which we reclaim and reframe our narratives in dialogue with one another and within the evolving landscape of teacher education.

Positionality

In this study, we position ourselves as two transnational teacher educators engaging in a collaborative autoethnographic inquiry to explore how our individual trajectories and institutional experiences have shaped our identities and practices within U.S. higher education. Through mutual reflection, we examine what it means to navigate teacher education as foreign-born scholars in predominantly white institutions.

Both of us were born and raised in South Korea, where we began our professional journeys as elementary school teachers in South Korea. We each came to the United States to pursue doctoral degrees in education. Gayoung is currently a female doctoral candidate and instructor in a teacher education program in the Midwest. SungEun is an early-career male faculty member in a teacher education program in the Northeastern United States. As Korean-speaking individuals who acquired English as a second language, we critically reflect on how our linguistic, cultural, and professional backgrounds shape our teaching, research, and identity development as transnational educators.

Data Source

In conducting a collaborative autoethnographic inquiry into how Korean teacher educators experienced Hallyu, we drew on a diverse range of data sources collected over the course of our time residing in South Korea from a young age and our time in the United States, seven years for one researcher and three years for the other. First, we began with individual writing and meaning-making through personal narratives, reflective journals, and memoirs related to our experiences of Hallyu and its counterpart, American culture. In these individual writings, we incorporated artifacts such as teaching materials, lesson plans, course evaluations, and letters from students.

Afterward, we shared our individual writings in group sessions and engaged in reflective conversations about the similarities and differences we observed. Additionally, we incorporated transcripts of conversations between the researchers discussing the individual writings and each person’s transnational experience in the United States. We also collected media and cultural artifacts that shaped our engagement with both Korean and American popular culture.

Together, these sources provided a rich and layered foundation for exploring the intersections of personal identity, professional practice, and cultural discourse.

Data Analysis

Following thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021), we analyzed our shared narratives through recursive cycles of reflection, interpretation, and meaning-making. Initially, we identified recurring elements in our stories—Korean educational values, cultural marginalization, and the influence of Hallyu. These elements became the basis for constructing analytic themes around identity tension, cultural affirmation, and pedagogical transformation. In the second stage, by utilizing concepts from postcolonial theories, we interrogated how particular experiences, such as moments of discomfort, pride, or shame, revealed internalized ideologies and possibilities for reframing our professional identities. Hallyu, in particular, emerged not only as a cultural anchor but as a transformative lens for reimagining ourselves as legitimate, asset-based educators. This analytic process, grounded in collaborative autoethnography (Chang et al., 2013), allowed us to generate insights that were both emotionally situated and politically meaningful.

Findings

1. Ontological Not-Enoughness and Otherness Within Embodied Orientalist Epistemologies

Our identities have been deeply shaped by Orientalism, which is not merely a set of cultural biases but a discursive system constructed by the West to define and dominate the non-West through structures of colonial power and knowledge (Said, 1978). Although formal colonialism has ended, its epistemic and affective residues continue to shape how we understand ourselves and our place in the world (Joo, 2016). Through Orientalism, we not only became the Other in the eyes of the West but also turned that gaze inward, engaging in self-othering that rendered us perpetually not enough.

It was full of students with pale faces, blonde hair, and blue eyes… They chatted joyously with each other, and when I entered, they all glanced at me and exchanged glances with each other, with slight smiles. I was the only Asian-looking person in a room of about 40 students. I tried to smile, but I was very terrified inside—simply because I was the one who looked so different in that space.

After the first day, I began to feel inadequate—and not enough. Compared to other professors, who are white and have teaching experience in American classrooms, I felt that everything was lacking. I lack experience in K–12 schools in the U.S., my English proficiency is not as native as that of the American professors, and I struggle to build a deep cultural connection with my students. I often find myself wondering if I truly belong here. I still question whether I am enough to stand at the front of this American classroom and call myself a teacher.

SungEun’s reflection

Reflecting on our initial few weeks of teaching teacher candidates in American teacher preparation programs, we both shared a sense of inadequacy and not-enoughness. It has also been terrifying for us to survive in a space where there is only one Asian teacher in the entire building. These affective responses are not unique to us. Research shows that many international faculty experienced similar feelings of inadequacy as educators due to language barriers, cultural differences, and a lack of teaching experience in American K-12 schools (Adebayo & Allen, 2020; Anandavalli et al., 2021; Bui, 2021; Han et al. 2025; Xu & Hu, 2020). Han et al. (2025) confessed that the systemic discrepancies between their home countries and the United States led to a sense of inadequacy and a struggle to bring the desired authenticity in the classroom. We highlight that these feelings were not solely grounded in our objective biographies but rather arise from internalized beliefs which were shaped by embodied Orientalist hierarchies. We believed we were inferior.

First of all, we felt a sense of inadequacy and otherness due to visible social markers. Our different skin tone, hair color, and facial features made it immediately apparent that we were Asian. We believed not only that we were different from American people, but also that they were “superior” in appearance.

If only for a day, let me be white.

This iconic longing of Gayoung captures the deeply racialized aesthetics that shaped our educational subjectivity. The perceived superiority of white embodiment—its social rewards, unspoken privileges, and symbolic legitimacy—has long been naturalized in our own imaginations. These beliefs were not formed in the United States; they were cultivated long before, in South Korea.

Our experience of Orientalist epistemology did not begin when we arrived in the United States. It began in Korea, where whiteness has long been idealized. Gayoung remembers working with Anne (pseudonym), a white American English teacher, in a Korean elementary school. One day, she said she wanted to spend the rest of her life in Korea. As a Korean citizen who held American citizenship and had long understood the symbolic power it carried, I was puzzled. But I soon understood.

I often helped her with shopping or outings, and everywhere we went together, Korea seemed extraordinarily kind to her.

At the post office, they gave her shipping boxes for free and assisted her with remarkable kindness. Even when she didn’t ask for help, someone always stepped up. At restaurants, they offered her free service items. She would smile and say, “Korea is so kind. I want to immigrate here.”

Her presence—tall, blonde, white—seemed to invite kindness I had never received myself as a Korean.

Gayoung’s reflection

Our sense of inadequacy also stemmed from linguistic hierarchies. Speaking English with Korean accents, rather than like “normal” American speakers, marked us as outsiders in American academia. We had grown up in a society where English proficiency was not only a skill but also a social marker of intelligence, social capital, and lifelong success (Min & Hong, 2015).

In that context, English was considered a superior language—more global, more valuable, more legitimate than Korean. The irony is that even after mastering English to the level of teaching in it, we still found ourselves wondering:

Am I enough to stand at the front of this classroom and call myself a teacher?

Our lack of K-12 teaching experience in the United States often felt like a disqualifier. Although we had years of teaching experience in Korea, they did not seem to count.

As educators working in public schools in South Korea, we had a strong aspiration to come to the United States to study education, as we viewed American education as the best in the world. The most widely cited educational theories, as well as many renowned scholars and researchers referenced in the education field in Korea, originated from the United States. To us, American education represented innovative educational philosophies, theories, and practices. We envisioned classrooms filled with lively discussions that prioritized critical thinking and creativity, project-based learning, cutting edge technologies, and teachers who nurtured individual students’ voices and identities. In contrast to the exam-driven and hierarchical structure of Korean schooling, American education appeared progressive, empowering, and liberating. These idealized constructions of the United States significantly influenced our decisions to pursue graduate study here.

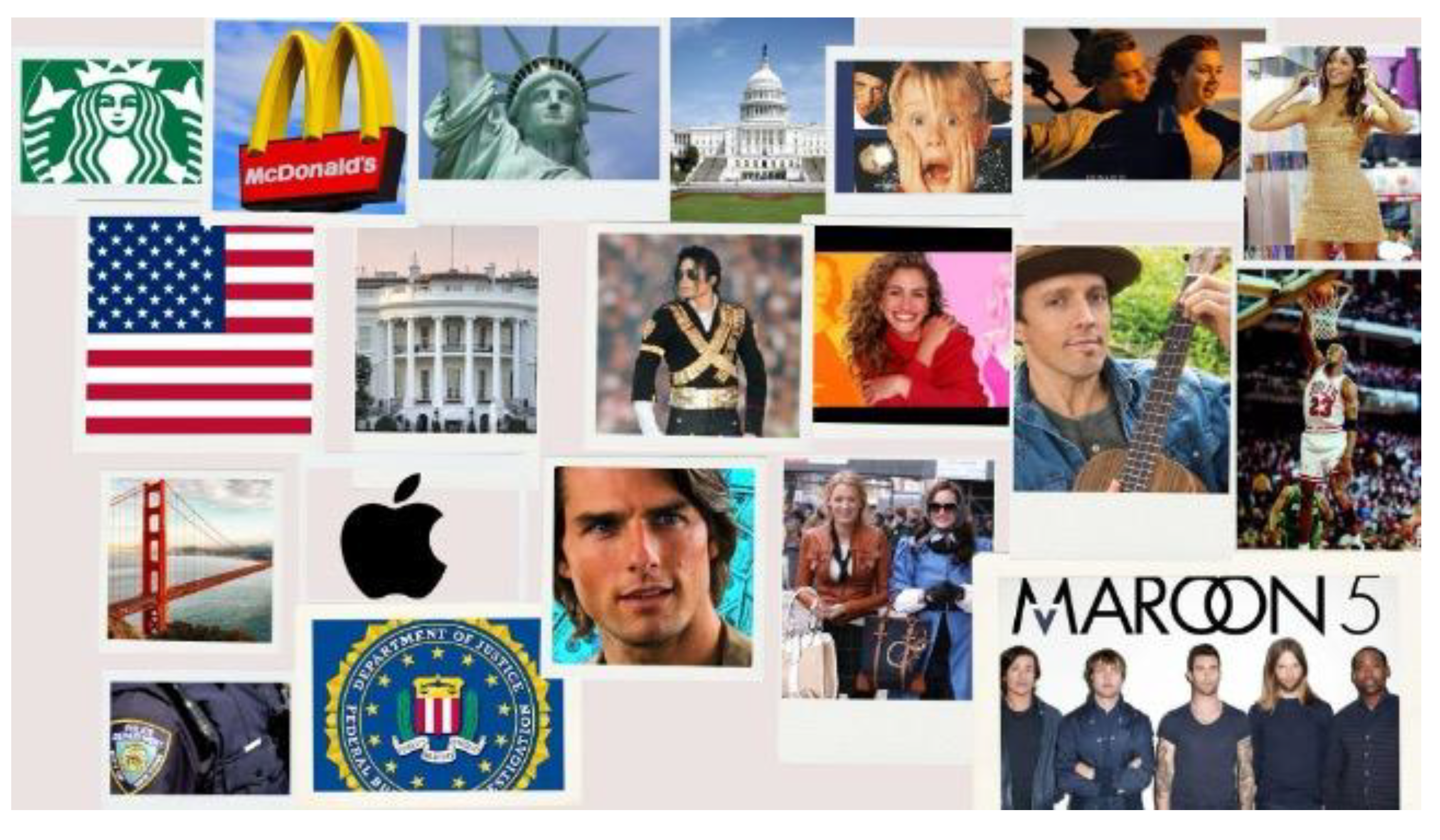

Ever since I was young, I have been captivated by Hollywood movies. The first film I ever watched in a theater was Home Alone, and I’ve rewatched it every Christmas season to relive the holiday spirit. To this day, I still consider Titanic one of the most flawless films in cinematic history—each viewing leaves me in awe of its compelling storyline, emotional depth, and stunning visual effects. Watching Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks, Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt, Nicole Kidman, Julia Roberts, I found them incredibly attractive and charismatic, reinforcing a glamorous image of American people. For me, America came to represent ideals such as freedom, liberty, democracy, global leadership, wealth, intelligence, and physical beauty. I always dreamed of visiting the United States someday.

SungEun’s reflection

Ever since I was young, I dreamed of a life in New York. I imagined myself somewhere between B and S, as a kind of Y

1—caught in that glittering in-between. I could see myself sitting on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art with friends, like a scene lifted straight out of Gossip Girl. Not buried in textbooks, but immersed in social worlds— gliding between Ivy League aspirations, parties, queen bees of the social scene, and proms. Things that felt utterly unimaginable in Korea seemed, in America, to be the natural rites of passage for any teenager. That dream shimmered in my mind, a quiet flame of possibility burning beyond the bounds of my reality.

Gayoung’s reflection

Figure 2.

Visual representations of American cultural symbols that shaped the authors’ early imaginaries of the United States.

Figure 2.

Visual representations of American cultural symbols that shaped the authors’ early imaginaries of the United States.

From a young age, we both wanted to come to the United States, the land of freedom, democracy, and happiness, full of intelligent and good-looking people. We Koreans have long lived with and aspired to American culture—it is deeply embedded in our daily lives.

This was not incidental. It was the product of cultural imperialism, where American soft power reshaped the aspirations of entire generations in Korea. Our desires, our self-perceptions, even our standards of educational excellence were forged in this unequal symbolic order. They were produced through embodied Orientalist epistemologies—racialized, gendered, and linguistic structures that rendered us simultaneously visible and illegible. Our journey as teacher educators in the United States revealed how deeply the legacies of cultural imperialism and racialized desire shaped even our most intimate professional uncertainties.

2. Paradigm Shift—“We Can Be Proud of Being Korean”: Hallyu as a Channel for Recognizing Cultural Identity as an Asset

“Could you add BTS’s Blood, Sweat and Tears to the music list for our work time?”

“Have you watched Squid Game? Do you know when the next season will come?”

“I saw this Korean recipe for japchae in a news magazine. Could you let me know how to get these noodles (dangmyeon)?”

Very interestingly, little by little, we’ve noticed that whenever people knew we were Koreans—whether in classrooms or other social settings—students, faculty, and individuals outside academia responded with great enthusiasm. They eagerly shared their experiences with Korean cultural products and expressed their knowledge of and interest in Korean culture by asking questions related to the topic. It was no longer surprising to see Korean language student clubs and K-pop dance teams at our universities, and many were genuinely enthusiastic about K-pop, K-dramas, and other aspects of Korean culture.

The emergence of Hallyu as a mainstream success in the United States has significantly impacted our lives as Korean teacher educators residing here, reshaping our perceptions of cultural identity. Experiencing Hallyu abroad and witnessing the widespread popularity of Korean cultural products and the transnational fandom surrounding Korean celebrities (Lee, 2016a; Yoon, 2019) served as an impetus for a “paradigm shift” (Kuhn, 1962) in how we perceived ourselves—from a deficit-based to an asset-based perspective. In particular, it helped us confront and move beyond our embodied sense of inferiority (Fanon, 1952/1986) and the internalized Western Orientalist discourse (Said, 1978) that has long portrayed us as inferior, dependent, and passive. Hallyu allowed us to recognize that what we possess is neither strange nor lacking in value but rather rich cultural assets that are appreciated and admired globally. The success of Hallyu stars and content is not theirs alone—it is also ours. We see ourselves reflected in them. Their success has become a form of aspirational capital (Yosso, 2005). Below, we explore how Hallyu has challenged and reshaped our identities as Korean teacher educators.

First, Hallyu challenges our embodied sense of inferiority in Asian bodies. This inferiority is associated with a broad perception of Asian bodies and identities (Museus & Iftikar, 2014), and we felt it particularly in our visibility (Foucault, 1975) in the white-dominant space of teacher education programs. Asian physical features have historically been mocked, with Asian men often stereotyped as lacking masculinity and physical attractiveness (Hamamoto, 1994; Lee, 1999), while Asian women have been depicted through hypersexualized stereotypes, such as the “submissive and obedient” trope or as exoticized figures desired through "yellow fever." One of the widely known racial microaggressions against the Asian population is pulling back the eyes to mock the shape of Asian eyes.

However, the rise of Hallyu has begun to challenge these portrayals, offering new representations of Asian bodies and redefining notions of both masculinity and femininity (Song & Velding, 2020). For example, in BTS’s “Boy With Luv” music video, the group subverts traditional gender expectations by embracing characteristics commonly coded as feminine. The members wear pink outfits, style their brightly colored hair casually, and accessorize with delicate jewelry like dangly earrings and layered pearl necklaces. This challenges traditional concepts of masculinity—such as the macho man ideal—and urges a reconceptualization of what masculinity can look like (Jung, 2011). Jung (2011) introduced the idea of soft masculinity, along with globalized and postmodern expressions of masculine identity, as reflected in the flexible forms of masculinity portrayed by K-pop boy bands within the framework of transcultural pop production. For both researchers, the success of Hallyu functioned as an oppositional gaze (Hooks, 1992) that challenged our internalized colonialism (Fanon, 1952/2008), particularly regarding the racialized Eurocentric norms of beauty and appearance.

Second, Hallyu challenged our deep-rooted assimilationist and monoglossic language ideology, valuing English as superior to Korean, and helped us to see our Korean language as linguistic capital (Yosso, 205) based on bilingual ideology. Thus we changed our perspective on our language from language-as-problem to language-as-asset. It was eye-opening to witness songs written entirely in Korean achieve global popularity, with American audiences not only singing along to Korean lyrics but also actively attempting to learn the Korean language. Among BTS's global hit songs, many feature Korean as the dominant language in the lyrics, such as “피땀눈물 (Blood Sweat and Tears)” in 2016, “DNA” and “봄날 (Spring Day)” in 2017, “Fake Love” and “Idol” in 2018, and “작은 것들을 위한 시 (Boy With Luv)” in 2019. We witnessed how our once-familiar mother tongue—taken for granted and regarded as inferior to English—became a valuable asset now recognized and appreciated in American society.

I got goosebumps watching BTS perform a song with Korean lyrics in collaboration with the British band Coldplay at the 2021 American Music Awards, which were held at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles, California, as Coldplay’s Chris Martin sang part of the song in Korean, while the American audience also sang along in Korean. (You can watch the performance here.)

SungEun’s reflection

Beyond K-pop, Korean dramas and films—such as Squid Game and Parasite—have received prestigious accolades, including Emmys and the 2020 Academy Awards, becoming the first non-English language works to achieve such honors. It was especially inspiring to watch Parasite director Bong Joon-ho accept the Oscar for Best International Feature Film. In his bold and witty acceptance speech, he said, “Once you overcome the 1-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films” (original Korean: “1인치 정도 되는 자막의 장벽을 뛰어넘으면, 여러분들이 훨씬 더 많은 영화를 즐길 수 있습니다”). His statement reflects a reversal of traditional linguistic hierarchies and ideologies: rather than urging non-English creators to cater to English-speaking audiences, he invited global viewers to embrace linguistic diversity by engaging with media in other languages.

Additionally, it is inspiring to see that, thanks to the global success of Hallyu, Korean words have been added to the Oxford English Dictionary, including noraebang (karaoke room), hyung or hyeong (elder brother), jjigae (stew), tteokbokki (spicy rice cake), and pansori (traditional lyrical opera). Seeing that our indigenous terminologies, which originated in Korea, were embraced in official authoritative dictionaries gave us great pride in the Korean language.

아파트 (apt), 아파트 (apt), 아파트 (apt)..., I had long understood the importance of moving beyond a monolingual perspective toward a multilingual one, but the question remained—how? The answer, unexpectedly, came through music. In the lyrics of BLACKPINK’s “Rosé,” Korean and English coexisted, crossing named language boundaries with ease. It was as if her linguistic practice embodied her identity as both a New Zealander and a Korean. In that moment, what I had encountered only in academic papers and conferences as translanguaging was suddenly realized—alive and resonant—in popular music itself.

Gayoung’s reflection

Hallyu offered a paradigm shift in our linguistic identity, moving from an assimilationist, monoglossic ideology to a pluralist and multilingual perspective. Hallyu taught us that the language we have can be a form of capital that American people want to acquire. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1986) critiqued the continued dominance of English in educational systems and literary production. Ngũgĩ argued that this linguistic hierarchy perpetuates colonial ideologies and alienates individuals from their cultural roots. He advocated for writing and teaching in indigenous languages as a radical act of reclaiming identity, culture, and resistance—a process he famously described as "decolonizing the mind." In a similar vein, Hallyu functions as a form of linguistic and cultural decolonization, challenging the monoglossic ideology that privileges English over Korean and repositioning the Korean language as a valued and legitimate medium of global cultural exchange.

Third, Hallyu challenged the fixed hierarchical onto-epistemology that positioned Western culture as superior and Korean culture as inferior, instead embracing greater cultural flexibility and hybridity (Bhabha, 1994). Homi Bhabha (1994) complicated the binary oppositions central to colonial discourse through his concept of hybridity, which resists rigid cultural identities. Rather than viewing our Korean identity as fixed or oppositional, Bhabha’s notion of the "third space" allowed us to conceptualize cultural in-betweenness—a space where hybrid identities emerge through negotiation and reinterpretation. Also, in recognizing the hybrid nature of Korean cultural products that combine their own indigenous funds of knowledge of Korean history and society and Western culture, we were able to negotiate hybrid or transnational identities (Jung, 2011; Kim, 2022). The hybrid nature of Korean cultural products is evidenced by K-pop dance, which is “genre hybridity” (Park, 2025). Many scholars argue that K-pop dance blends diverse Western dance forms—such as modern, hip-hop, street, and jazz—to create a distinctive and innovative style of performance. (Lie, 2012, Lie, 2015; Oh, 2015; Shim, 2006). Also, its choreographic style and visual elements are also strongly influenced by traditional Korean performance practices, especially Talchum (mask dance), which highlights coordinated movement, storytelling, and collective emotional expression (Park, 2025). Seeing the hybrid nature of Korean cultural products and their success with global audiences, the researchers were able to develop more hybrid, flexible, and transnational identities and ways of being.

3. Cultural Threads from Home: Weaving Korean Cultural Wealth into Teacher Education and Higher Education

Through the paradigm shift in the Korean teacher educators’ perceived identities—shaped by Hallyu—from a deficit-based to an asset-based perspective, the educators recognized and incorporated Community Cultural Wealth (Yosso, 2005) into their teaching practices and strategies within teacher education programs.

First, the Korean teacher educators incorporated their linguistic capital, in particular, their Korean language competencies, into teaching various literacy, ESL, or multicultural education courses. According to Yosso (2005), linguistic capital includes the communication competencies nurtured through multilingual experiences (Orellana et al., 2003).

For instance, Gayoung incorporated the syntax of the Korean language into teaching the English language system in literacy courses, such as when teaching prepositions or postpositions from a comparative linguistic perspective. She observed that using the Korean language system to explain the English system helped students quickly grasp the meaning, and the approach proved to be very effective. Additionally, when co-teaching with a white professor on the topic of metaphor, a student asked whether the notion of metaphor exists in other countries. Gayoung proudly introduced examples of metaphor in the Korean language system through traditional Korean proverbs and metaphoric expressions.

Second, Korean teacher educators draw on their familial capital rooted in Korean ethnicity. According to Yooso (2005), familial capital, as outlined by Delgado Bernal (1998, 2002), refers to the knowledge, values, and traditions transmitted through family and extended kinship ties. They incorporate traditional Korean games and food—transmitted through their home culture—into their instruction for preservice teachers. SungEun introduced Korean traditional games such as ttakji-chigi (딱지치기), yut-nori (윷놀이), jegi-chagi (제기차기), and paengi-dolligi (팽이 돌리기), which he used to play with his family members and friends from a young age, as well as Korean dishes like tteokbokki and japchae, in a multicultural education course. Along with introducing the Korean traditional games and food, he shared the stories relating to the games and food about what these meant to him. I played yut-nori with all my family members during Seollal (Lunar New Year) or Chuseok (Korean Thanksgiving Day) when I was young. I have many fond memories of the game, and I still play it with my family here in the U.S. I also taught my daughter how to play.

This was done to model culturally responsive teaching, promote an asset-based perspective on students from diverse backgrounds, and enhance preservice teachers’ cultural awareness.

Third, the two researchers proactively incorporated the experiences and perspectives of marginalized positionalities, such as English language learners and Koreans, into their teaching and community service. As Ashcroft et al. (1989) suggested, the researchers affirmed their marginalized identities and recognized the importance of using those identities as sites of resistance and agency. Rather than viewing marginality as a deficit, they positioned it as a powerful lens through which to critique dominant discourses and foster more inclusive and culturally responsive pedagogies. Their marginalized positionality became a form of resistant capital, referring to the critical knowledge and skills developed through efforts to confront and resist systemic inequities (Freire, 1970, 1973; Giroux, 1983; McLaren, 1994).

The researchers actively challenged monolingual ideologies and the forms of oppression they imposed on linguistically and culturally diverse students. For instance, they strategically used Korean-only instruction to help preservice teachers understand how English language learners might feel when instruction is delivered solely in English, drawing on their own experiences as English learners in monolingual English-only spaces. Gayoung had students read Korean text written on the board and told the teacher candidates, “The feeling you have now is your future students’ feeling.” Additionally, SungEun shared his struggles learning English as a Korean speaker, particularly with English sounds that do not exist or are not distinguished in the Korean sound system, such as th/d and p/f. He explained how certain English accents among non-native speakers can be understood in relation to the phonological structures of their first language.

Fourth, the Korean teacher educators incorporated their insider perspectives on Hallyu to help preservice teachers move beyond a surface-level and static understanding of culture and engage in deeper, more critical thinking—avoiding cultural appropriation and fostering cultural appreciation. They were also cautious about the possibility of essentializing Korean culture or reinforcing stereotypes of Korean or Asian identities through Hallyu phenomena, such as the equation “Korean culture = K-pop.” For instance, SungEun shared with students,

There are many different types of K-pop, and the K-pop I used to listen to a lot when I was young is different from the styles that current K-pop groups perform. I like BTS and Blackpink, but I’m not very familiar with other current boy or girl K-pop groups. Also, there are many types of Korean food besides kimchi, and I’m not even a big fan of kimchi.

SungEun also offered a campus-wide lecture series on how Hallyu can serve as a vehicle to challenge Eurocentrism and Asian hate by addressing the long history of microaggressions, hate crimes against Asian populations, and stereotypes of Asians in the United States. The series aimed to move beyond cultural appropriation of Hallyu toward cultural appreciation, while promoting critical thinking about culture from the perspectives of positionality, privilege, and power. Our efforts inspired the students we taught, and one of the students who took our course wrote a letter at the end of the semester:

Dear Professor,

Thank you so much for your support and guidance throughout my journey. I truly admire the way you teach with compassion. Your pride in your identity and your openness have deeply inspired me. You’ve reminded me that being yourself is a powerful form of teaching itself.

This heartfelt message underscores the profound impact that educators’ authentic cultural expression and familial knowledge can have on preservice teachers, fostering empathy, respect, and a deeper appreciation for diversity within teacher education.

Discussions and Implications

Through engagement with Hallyu, this collaborative ethnography demonstrates that the Korean teacher educators challenged the Eurocentric Orientalism internalized in their bodies and onto-epistemologies through a long history of cultural imperialism. In doing so, they experienced a paradigm shift in their identities—from a deficit-based to an asset-based perspective. They actively incorporated their community cultural wealth into their teaching practices, which suggests several broader implications.

Challenging the Marginality of Non-Western Thought and Curriculum Epistemicide

This research demonstrates that transnational teacher educators in the United States can challenge Eurocentric onto-epistemologies and can shift the deficit perspective rooted in an embodied sense of inferiority to an asset-based perspective. By actively reflecting on their lived experiences of how non-Western cultural products are appreciated in U.S. society—and by incorporating their cultural assets, identities, and perspectives into teacher education programs—they resist what Paraskeva (2016) terms curriculum epistemicide—the systematic silencing of non-Western knowledge systems—and reclaim cultural space within these programs. Drawing on decolonial theory, Paraskeva (2016) conceptualizes curriculum epistemicide as the legitimization and dominance of Western Eurocentric discourses and practices in education, which render non-Western perspectives silent and invisible. Similarly, Takayama et al. (2016) critiqued the ongoing marginalization of non-Western perspectives and argued decolonial and postcolonial scholarship in the field of education. The researchers in this study demonstrated how they mobilized their Orientalist marginality as a form of resistant capital (Yosso, 2005), transforming it into pedagogical agency and identity affirmation, thereby legitimizing non-Western cultural products within Western teacher education.

Building on its critique of Eurocentric epistemologies, we turn to Hallyu itself as a source of theoretical insight. We challenge the tendency to treat Western knowledge systems as universal truths (Joo, 2016). Instead, we dismantle these hegemonic frameworks to rediscover and legitimize forms of indigenous knowledge once deemed marginal or even illicit (Ghadhi, 1998). By theorizing Hallyu from within its own cultural foundations, we begin to see it through its own lens—no longer filtered through Western eyes but embraced as a living epistemology in its own right.

Incorporation of Transnational Teacher Educators’ Cultural Assets Into Teacher Education

The researchers’ integration of Korean culture, along with their insider perspectives and identities, into teaching practice demonstrated how transnational teacher educators can provide valuable multicultural and transnational insights on affirming and incorporating Community Cultural Wealth (Yosso, 2005) from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. They also highlight the importance of valuing the cultural assets within these communities and encourage moving beyond a superficial, fixed view of culture to promote deeper, critical reflection, helping to prevent cultural appropriation and support genuine cultural appreciation. Their cultural journey can inspire future teachers and model a culturally sustaining pedagogy and arts-integrated curriculum that moves beyond mere inclusion toward active cultural engagement and affirmation (Paris & Alim, 2017), leveraging other non-Western cultural products such as Korean cultural artifacts. This approach can foster cultural empathy and challenge stereotypes associated with marginalized ethnic groups.

We are reminded of the phrase, “What is Korean is global (한국적인 것이 세계적인 것이다).” This is more than a simple expression of cultural pride; it resonates as a declaration that our culture and language—long positioned at the periphery—are no longer bound by the standards of a single center. From a postcolonial perspective, it unsettles the hierarchical order that has taken Western universality as an unquestioned norm and redefines the value and meaning of what is uniquely Korean. In this sense, “global” no longer signifies conformity to Western criteria. Rather, it points to a process through which our own cultural contexts, histories, and languages generate their own global resonance. Realizing that what is Korean is indeed global allows us to view our cultural practices and identities not as deficient or in need of supplementation, but as rich epistemic resources through which we can engage in dialogue with the world.

References

- Adams, T. E., Holman Jones S. L., & Ellis, C (2015). Autoethnography. Oxford University Press.

- Adebayo, C. T., & Allen, M. (2020). The experiences of international teaching assistants in the U.S. classroom: A qualitative study. Journal of International Students, 10(1), 69–83. [CrossRef]

- Anandavalli, S., Borders, L. D., & Kniffin, L. E. (2021). “Because here, White is right”: Mental health experiences of international graduate students of color from a critical race perspective. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 43(3), 283–301. [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, B., Griffiths, G., & Tiffin, H. (1989). The empire writes back: Theory and practice in post-colonial literatures. Routledge.

- Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. (J. B. Thompson, Ed.; G. Raymond & M. Adamson, Trans.). Harvard University Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

- Bui, T. A. (2021). Becoming an intercultural doctoral student: Negotiating cultural dichotomies. Journal of International Students, 11(1), 257–265. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F. W., & Hernandez, K.-A. C. (2013). Collaborative autoethnography. Routledge.

- Cho, C. L. (2010). “Qualifying” as teacher: Immigrant teacher candidates’ counter-stories. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 100, 1–22.

- Cruz, D. (2019). Global fandom and cultural flows: K-pop and transnational identity formation. Journal of Youth and Cultural Studies, 12(1), 45–60.

- Delgado Bernal, D. (1998). Using a Chicana feminist epistemology in educational research. Harvard Educational Review, 68(4), 555–582.

- Delgado Bernal, D. (2002). Critical race theory, LatCrit theory and critical raced-gendered epistemologies: Recognizing Students of Color as holders and creators of knowledge. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 105–126.

- Ellis, C., Adams, T.E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Article 10.

- Fanon, F. (1986). Black skin, white masks (C. L. Markmann, Trans.). Pluto Press. (Original work published 1952).

- Faez, F. (2011). Reconceptualizing the field of language teacher education: A postmodern approach. TESOL Journal 2(3), 403–415. [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Pantheon Books.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

- Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. Seabury Press.

- Gibson, J. (2015, December 30). Korean boom: As foreign language enrollments drop in the U.S., Korean is on the rise. Korea Economic Institute of America. https://keia.org/the-peninsula/korean-boom-as-foreign-language-enrollments-drop-in-the-u-s-korean-is-on-the-rise/. 30 December.

- Giroux, H. A. (1983). Theory and resistance in education: A pedagogy for the opposition. Bergin and Garvey.

- Hamamoto, D. Y. (1994). Monitored peril: Asian Americans and the politics of TV representation. University of Minnesota Press.

- Han, S., Su, C., & Qi, Y. (2025). From challenges to assets: Collaborative autoethnography on the transcultural journeys as teacher educators. Journal of International Students, 15(4), 171-188. [CrossRef]

- He, M. F., & Cooper, R. (2009). The ABCs for pre-service teachers: Experiences of culturally and linguistically diverse teacher educators. Multicultural Perspectives, 11(1), 29–35. [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B. (1992). The oppositional gaze: Black female spectators. In: Black looks: Race and representation. (pp. 115–131). South End Press.

- Hughes, S. A. (2008). Toward “good enough methods” for autoethnography: Trying to resist the matrix with another promising red pill. Educational Studies, 43, 125–143. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S., Pennington, J. L., & Makris, S. (2012). Translating autoethnography across the AERA standards: Toward understanding autoethnographic scholarship as empirical research. Educational Researcher, 41, 209–219. [CrossRef]

- Hong, E. (2014). The birth of Korean cool: How one nation is conquering the world through pop culture. Picador.

- Jang, W., & Song, J. E. (2017). The influences of K-pop fandom on increasing cultural contact: With the case of Philippine Kpop Convention, Inc. Korean Regional Sociology, 18(2), 29-56.

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers, and gamers: Exploring participatory culture. NYU Press.

- Jin, D. Y. (2016). New Korean Wave: Transnational cultural power in the age of social media. University of Illinois Press.

- Jin, D. Y., & Yoon, K. (2016). The social mediascape of transnational Korean pop culture: Hallyu 2.0 as spreadable media practice. New Media and Society, 18(7), 1277–1292. [CrossRef]

- Jin, D. Y. (2023). Transnational proximity of the Korean Wave in the global cultural sphere. International Journal of Communication, 17, 9–28.

- Joo, J. (2011). Transnationalization of Korean popular culture and the rise of “pop nationalism” in Korea. The Journal of Popular Culture, 44(3), 489–504. [CrossRef]

- Joo, J. (2016). Postcolonialism and qualitative research: Methodological issues. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 34(4), 1–25.

- Jung, S. (2011). K-pop, Indonesian fandom, and social media. Transformative Works and Cultures, 8. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S., Kim, Y., & Lee, J. (2022). Korean Wave reception and hybrid identity formation among international audiences. Media, Culture & Society, 44(5), 875–892.

- Kang, H., Lyu, S., & Yun, S. (2022). Going beyond the (un)awakened body: Arts-based collaborative autoethnographic inquiry of Korean doctoral students in the United States. Journal of International Students, 12(2), 88–105.

- Khiun, L. K. (2013). K-pop dance trackers and cover dancers: Global cosmopolitanization and local spatialization. In: Y. Kim (Ed.), The Korean Wave. (pp. 165–181). Routledge.

- Kim, Y. (2015). South Korean cultural diplomacy and soft power: The Hallyu strategy. Asian Perspective, 39(3), 421–450.

- Kim, Y. (2022a). K-pop fandom and cultural identity among Asian American youth. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. (2022b). BTS and the politics of belonging in global pop culture. Media, Culture and Society, 44(5), 943–959. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T., Jang, S. B., Jung, J. K., Son, M., & Lee, S. Y. (2024). Negotiating Asian American identities: Collaborative self-study of Korean immigrant scholars’ reading group on AsianCrit. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 17(6), 972–985. [CrossRef]

- Koo, K. (2021). Distressed in a foreign country: Mental health and well-being among international students in the United States during COVID-19. In K. Bista, R. M. Allen, & R. Y. Chan (Eds.), Impacts of COVID-19 on International Students and the Future of Student Mobility: International Perspectives and Experiences. (1st ed., pp. 28–41). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (2nd ed). Jossey-Bass.

- Lee, H. (2020). Becoming a global fan: Transnational Korean pop culture and digital literacies. E-Learning and Digital Media, 17(3), 202–218. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-K. (2020). Hallyu and the reimagining of Asian identity in the West. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 20(1), 47–56.

- Lee, R. G. (1999). Orientals: Asian Americans in popular culture. Temple University Press.

- Lee, S. J., & Nornes, A. M. (Eds.). (2015). Hallyu 2.0: The Korean Wave in the age of social media. University of Michigan Press.

- Leung, S. (2021). K-pop fandoms, activism, and the Black Lives Matter movement. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 24(6), 944–961. [CrossRef]

- Lie, J. (2012). What is the K in K-pop? South Korean popular music, the culture industry, and national identity. Korea Observer, 43(3), 339–363.

- Lie, J. (2015). K-pop: Popular music, cultural amnesia, and economic innovation in South Korea. University of California Press.

- Lidzhieva, A. M. (2021). “Are you Koreans?”, “No, we are Kalmyks!”: The development of K-pop cover dance among Kalmykia’s youth revisited. Oriental Studies, 14(2), 337–346. [CrossRef]

- Looney, D., & Lusin, N. A. (2018). Enrollments in languages other than English in United States institutions of higher education, Summer 2016 and Fall 2016: Final report. Modern Language Association. https://www.mla.org/content/download/83540/2197676/2016-Enrollments-Short-Report.pdf.

- McLaren, P. (1994). Life in schools: An introduction to critical pedagogy in the foundations of education. Longman.

- Min, S., & Hong, Y. K. (2015). An autoethnography on the teaching experience of an English language specialist regarding colonialism, Journal of Curriculum Integration, 9(2), 93–123.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Korea Foundation. (2022). Analysis of global Hallyu status. Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Korea Foundation.

- Molina, E., & Yoon, H. Y. (2022, March 4). No. of global Hallyu fans sees 17-fold jump to 150M in 10 years. Korea.net. https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=211458.

- Morrell, E., & Duncan-Andrade, J. M. R. (2002). Promoting academic literacy with urban youth through engaging Hip-Hop culture. English Journal, 91(6), 88–92.

- Morrison, T. (1992). Playing in the dark: Whiteness and the literary imagination. Harvard University Press.

- Museus, S. D., & Iftikar, J. (2014). Asian critical theory (AsianCrit). In M. Y. Danico (Ed.), Asian American society: An encyclopedia (pp. 95–98). Sage Publications; Association for Asian American Studies.

- Myles, J., Cheng, L., & Wang, H. (2006). Teaching in elementary school: Perceptions of foreign-trained teacher candidates on their teaching practicum. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 233–245.

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiongʼo. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. Heinemann.

- Nye, J. S. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. PublicAffairs.

- Oh, I., & Park, G. S. (2012). From B2C to B2B: Selling Korean pop music in the age of new social media. Korea Observer, 43(3), 365–397.

- Oh, I., & Lee, H.-J. (2013). K-pop in Korea: How the pop music industry is changing a post-developmental society. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 9, 105–124. [CrossRef]

- Orellana, M. F., Reynolds, J., Dorner, L., & Meza, M. (2003). In other words: Translating or ‘para-phrasing’ as a family literacy practice in immigrant households. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(1), 12–34. [CrossRef]

- Paraskeva, J. M. (2016). Curriculum epistemicide: Towards an itinerant curriculum theory. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Park, H. (2025). Conceptual inquiry of K-pop dance as postcolonial educational discourse toward global dance and physical education studies. Educational Philosophy and Theory. [CrossRef]

- Phillion, J., He, M. F., & Connelly, F. M. (Eds.). (2009). Narrative and experience in multicultural education. Sage Publications. [CrossRef]

- Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

- Santoro, N. (2014). If I’m going to teach about the world, I need to know the world: Developing Australian pre-service teachers’ intercultural competence through international trips. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 17(3), 429–444. [CrossRef]

- Shim, D. (2006). Hybridity and the rise of Korean popular culture in Asia. Media, Culture and Society, 28(1), 25–44. [CrossRef]

- Song, K. Y., & Velding, V. (2020). Transnational masculinity in the eyes of local beholders? Young Americans’ perception of K-pop masculinities. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 28(1). 3–21. [CrossRef]

- Septiani, Y. Y., Kasiyan, & Saputra, A. (2022). K-POP dance girls and Moslem women in Indonesia: An axiological review. In J. Priyana & N. K. Sari (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Education Research and Innovation (ICERI 2021). (pp. 64–74). Atlantis Press SARL. [CrossRef]

- Smith, V. S. (2021, August 6). How BTS is adding an estimated $5 billion to the South Korean economy a year. NPR News. https://www.npr.org/2021/08/06/1025551697/how-bts-is-adding-an-estimated-5-billion-to-the-south-korean-economy-a-year.

- Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2001). Manufacturing hope and despair: The school and kin support networks of U.S.-Mexican youth. Teachers College Press.

- Statistics Korea. (2023). Population projections: Major demographic indicators (sex ratio, growth rate, population structure, dependency ratio, etc.) [Data set]. Statistics Korea. https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?sso=okandreturnurl=https%3A%2F%2Fkosis.kr%3A443%2FstatHtml%2FstatHtml.do%3FtblId%3DDT_1BPA002%26orgId%3D101%26checkFlag%3DN%26.

- Subedi, B. (2006). Preservice teachers’ beliefs and practices: Religion and religious diversity. Equity and Excellence in Education, 39(3), 227–238. [CrossRef]

- Subtirelu, N. C. (2015). “She does have an accent but…”: Race and language ideology in students’ evaluations of mathematics instructors on RateMyProfessors.com. Language in Society, 44(1), 35–62. [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. (2021). The power of K-pop: Motivational influences of Korean popular music on language and cultural learning. Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 9(1), 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Suspitsyna, T. (2021). Internationalization, whiteness, and biopolitics of higher education. Journal of International Students, 11(S1), 50–67. [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K., Sriprakash, A., & Connell, R. (2016). Toward a postcolonial comparative and international education. Comparative Education Review, 61(S1), S1–S24. [CrossRef]

- Trent, J. (2011). “Four years on, I’m ready to teach”: Teacher education and the construction of teacher identities. Teachers and Teaching, 17(5), 529–543. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., & Hu, J. (2020). Language feedback responses, voices and identity (re)construction: Experiences of Chinese international doctoral students. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57(6), 724–735. [CrossRef]

- Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91.

- Yuan, R. (2019). ‘This has to be done in English’: A narrative inquiry into identity construction of a transnational Chinese English teacher. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 10–20. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

This refers to the television series Gossip Girl, where Blair Waldorf (B) and Serena van der Woodsen (S) represent two iconic social archetypes within elite Manhattan youth culture. “Y” refers to the narrator (Gayoung), who imagines herself aspirationally situated between these two figures.

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).