1. Introduction

Savannas are highly heterogeneous ecosystems characterised by a dynamic mosaic of grasses, shrubs, and trees [

1,

2]. This heterogeneity is largely driven by microclimatic variation, with rainfall emerging as a primary determinant that regulates major ecological processes [

3,

4]. Variation in rainfall at both seasonal and interannual scales directly influence vegetation productivity, fuel accumulation, and the susceptibility of the ecosystem to disturbances such as fire [

5]. Through its control of water availability, rainfall underpins the growth of grasses and trees, mediates competition among plant functional types, and shapes patterns of herbivory and nutrient cycling [

1,

2,

6].

Fire is a central ecological process in savannas, but its occurrence, frequency, and intensity are strongly mediated by microclimatic conditions and fuel availability [

7,

8]. Frequent fires tend to limit tree recruitment and favor grasses, whereas infrequent fires allow tree densities to increase, potentially leading to woody encroachment [

9,

10]. The intensity and spread of fire are themselves contingent on rainfall-driven fuel loads, highlighting the indirect but powerful role of microclimatic variability in shaping fire–vegetation interactions [

11,

12]. In Etosha National Park, for example, the onset of spring in 2025 saw an outbreak of a high-intensity fire, following above-average rainfall during the preceding summer. The elevated fire intensity can be attributed to substantial biomass accumulation over time, resulting from several years of limited fire activities coupled with favorable rainfall conditions.

Empirical and theoretical studies [

11,

13,

14] have documented the importance of these feedbacks, but most have focused on average ecosystem responses or on fire dynamics in isolation, often neglecting the fine-scale spatial and temporal heterogeneity of rainfall and fuel distribution.

Vegetation and environmental heterogeneity, mediated by rainfall and microclimatic conditions, can profoundly affect savanna responses to disturbances [

5,

15,

16]. Areas with high grass biomass resulting from favorable rainfall may experience more intense fires, while patches with sparse fuel or greater tree cover may remain relatively unaffected [

17,

18]. However, many modeling approaches simplify these dynamics by assuming uniform rainfall, biomass, and fire susceptibility, limiting their ability to capture the nuanced interactions between climate, vegetation, and disturbance processes [

19,

20,

21].

Addressing these gaps requires models that explicitly integrate microclimatic variability, particularly rainfall, with vegetation dynamics and disturbance regimes. By linking rainfall patterns to biomass accumulation, herbivory, and fire occurrence, such models can illuminate the feedbacks that drive ecosystem trajectories. This approach is essential for predicting long-term savanna dynamics, informing management strategies, and assessing ecosystem resilience under changing climatic conditions.

The purpose of the present study is to develop a mechanistic simulation model that captures the interactions between rainfall variability, vegetation growth, and fire dynamics in savanna ecosystems. By explicitly modeling grass and shrub biomass over time, along with stochastic fire occurrence and intensity, the model aims to explore how different rainfall regimes influence fire frequency, fuel accumulation, and the long-term balance between grasses and trees. This approach allows for the assessment of environmental heterogeneity effects on savanna responses to fire, providing insights into the feedbacks between biomass production and disturbance regimes. Ultimately, the model serves as a tool to investigate the conditions under which fire regulates vegetation structure and to predict potential shifts in ecosystem composition under varying climatic and disturbance scenarios. This model is particularly applicable to semi-arid terrains such as the central Kalahari Basin, where topography is relatively flat and soils are homogenous, leaving rainfall as the main determinant of primary production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Description

We developed a mechanistic, stochastic model to simulate savanna vegetation dynamics and fire disturbances over a 100-year period in R 4.5.2. The model operates on a monthly time step to capture seasonality in rainfall and fire risk. Four hypothetical rainfall regimes—200 mm, 300 mm, 400 mm, and 500 mm per year were considered, representing arid to mesic and wetter savanna conditions. Wet-season months were defined as October to March, whereas July through September were considered dry and fire-prone. The model tracks grass biomass (), shrub biomass (), fuel biomass (), fire frequency, and fire intensity (), incorporating environmental stochasticity through monthly rainfall (), temperature (), humidity (), and wind speed ().

Vegetation growth was modeled using logistic dynamics to capture saturation effects and competition. Grass biomass was updated monthly as:

where

is the intrinsic monthly growth rate,

is the rainfall-specific grass carrying capacity,

is a rainfall growth coefficient, and

is monthly rainfall. shrub biomass also followed logistic growth, but with competitive suppression from grass:

where

and

are the intrinsic growth rate and carrying capacity for trees,

is the rainfall growth coefficient, and

C is a constant representing grass-tree competition.

Fuel biomass, representing combustible material, was calculated as:

Fire occurrence was probabilistic in dry-season months, with the monthly probability defined as:

where

is the baseline ignition probability,

is the average fuel biomass for a given rainfall regime, and

is monthly relative humidity. Fire intensity (

, kJ/m²) was determined by fuel biomass, humidity, and wind speed (

):

When fire occurred, biomass was reduced to simulate consumption:

Environmental drivers were incorporated using stochastic sampling. Wet-season rainfall was drawn from a normal distribution with mean equal to annual rainfall divided by six and standard deviation 20 mm, while dry-season rainfall was set to zero. Temperature followed a normal distribution with mean 28°C and standard deviation 2°C. Humidity was sampled around rainfall-specific mean values (30–45%) with standard deviation 5%, and wind speed had mean 5 m/s and standard deviation 2 m/s.

Monthly biomass and fire data were aggregated annually to compute mean grass, tree, and fuel biomass, fire frequency, and fire intensity:

Fire frequency was the sum of monthly fire occurrences, and mean fire intensity was calculated as the average of fire-intensity values for months when fire occurred.

Table 1.

Key parameters used in the savanna fire–vegetation model (values are averages where ranges exist).

Table 1.

Key parameters used in the savanna fire–vegetation model (values are averages where ranges exist).

| Parameter |

Value |

Description |

Source |

|

0.05 |

Grass intrinsic growth rate |

[9,22] |

|

0.03 |

Shrub intrinsic growth rate |

[1,6] |

|

4000 kg/ha |

Grass carrying capacity |

[2] |

|

1200 kg/ha |

Shrub carrying capacity |

[1,14] |

|

5 kg/ha per mm |

Rainfall growth coefficient for grass |

[3,16] |

|

2 kg/ha per mm |

Rainfall growth coefficient for trees |

[3,16] |

|

0.035 |

Base fire ignition probability |

[8,11] |

| C |

500 kg/ha |

Grass–tree competition constant |

[9,22] |

|

30–45% ± 5% |

Monthly humidity |

[11,18] |

|

m/s |

Monthly wind speed |

[7,11] |

2.2. Model Sensitivity and Validation

We evaluated the robustness of the savanna fire–vegetation model by varying five key parameters such as grass and shrub growth rates, fire ignition probability, and grass and shrub post-fire regrowth by ±10% from their baseline values in a mesic savanna (300 mm annual rainfall). The impact on grass biomass, shrub biomass, fuel load, fire frequency, and fire intensity was quantified using a Sensitivity Index (SI), representing the relative change from baseline conditions.

The analysis revealed that intrinsic growth rates of grass and shrubs exert the strongest influence on biomass dynamics. A 10% increase in grass growth raised grass biomass by approximately 14% and shrub biomass by nearly 18%, while shrub growth produced up to a 22% change in shrub biomass. Fire frequency and intensity were highly sensitive to both grass growth and ignition probability, reflecting the critical link between fuel accumulation and fire behaviour. In contrast, post-fire regrowth fractions of grass and shrubs had moderate effects, indicating that recovery dynamics fine-tune biomass but do not dominate long-term trends.

Overall, the model dynamics are primarily controlled by vegetation growth rates and ignition probability, with fuel accumulation mediating the interaction between biomass and fire. Post-fire regrowth modulates the system but plays a secondary role.

Model validation was carried out using remote sensing data covering Etosha National Park, which extends along a rainfall gradient ranging from approximately 200 mm per annum in the west to about 450 mm per annum in the east. Proxy indicators, including the kernel Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (kNDVI), the differenced Normalized Burn Ratio (dNBR), and fire frequency, exhibited significant variation along the east–west rainfall gradient, consistent with the model’s predicted patterns.

3. Results

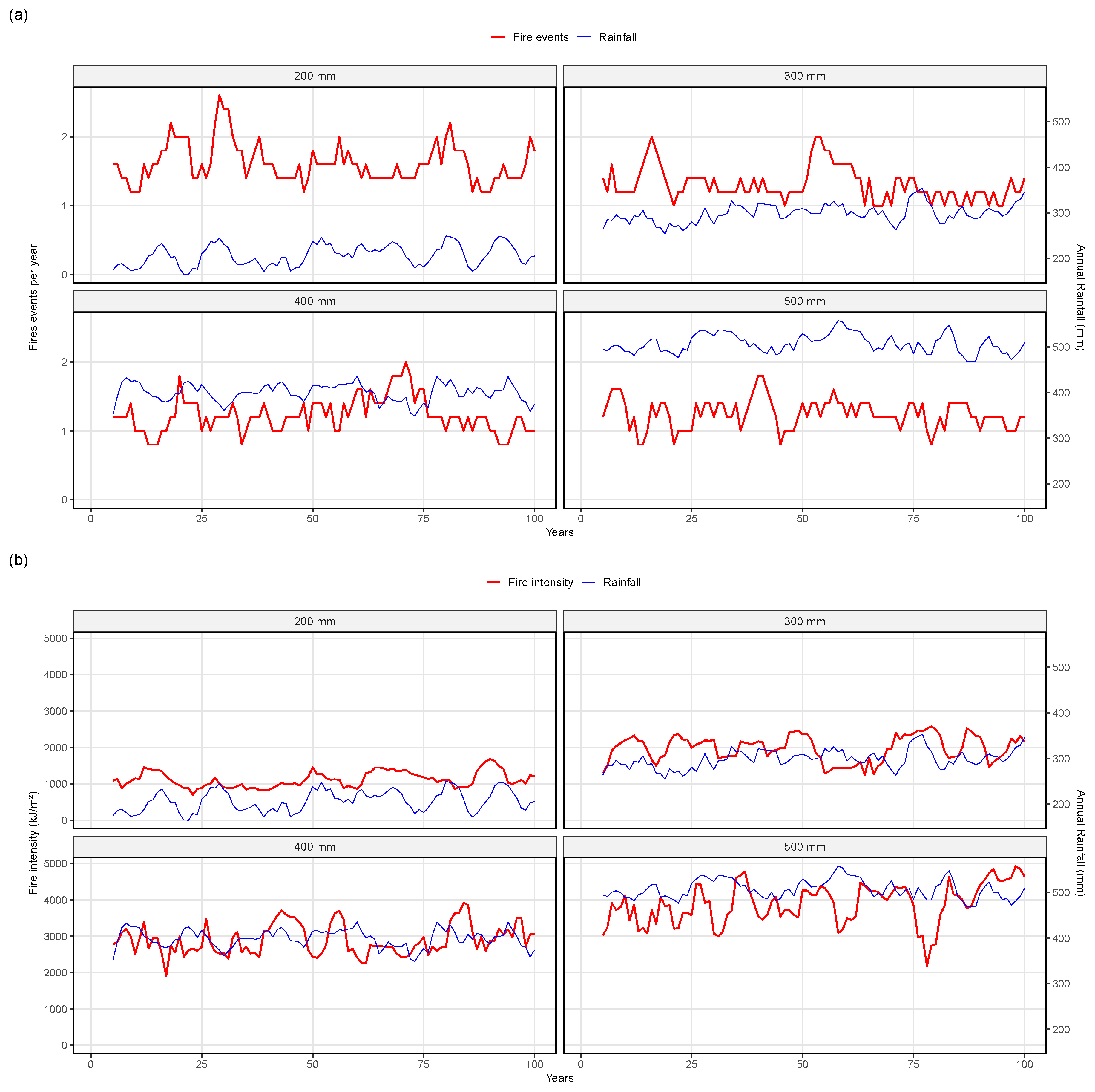

3.1. Variation in Fire Frequency and Intensity over Time

The results revealed consistent differences in fire frequency across rainfall regimes (

Figure 1a). In the 200 mm regime, fire events were most frequent, with multiple occurrences typically recorded within each 5-year interval throughout the simulation. The 300 mm regime also exhibited relatively high frequencies, although the temporal pattern was more variable, with some 5 year intervals characterised by several events and others by fewer. At 400 mm, the number of fire events declined further, with extended periods showing only a single occurrence or no fire within a given 5-year interval. The lowest frequencies were observed in the 500 mm regime, where long intervals without fire were punctuated only occasionally by isolated events.

Fire intensity displayed an opposing pattern to frequency, generally increasing with rainfall (

Figure 1b). In the 200 mm rainfall regime, fire intensity remained consistently low throughout the simulation, with both mean and peak values below 1,000 kJ/m². The 300 mm regime exhibited higher intensity, ranging from 1,500 to 2,000 kJ/m² and occasional peaks exceeding 2,000 kJ/m² during burning intervals. At 400 mm, fire intensity increased markedly, ranging from 2,000 and 3,000 kJ/m² and several peaks above 4,000 kJ/m². The 500 mm regime produced the most intense fires with intensity ranging from 3,000 kJ/m² to 5,000 kJ/m², despite the reduced frequency of fire occurrence.

Overall, these results reveal a clear pattern: as mean annual rainfall increases, fire events become less frequent but burn more intensely. Temporal variability in both frequency and intensity is more pronounced under moderate to high rainfall regimes. While fire frequency shows limited responsiveness to short-term rainfall fluctuations, fire intensity is more closely aligned with rainfall peaks, indicating that rainfall exerts a stronger influence on the energy released during fires than on the number of events.

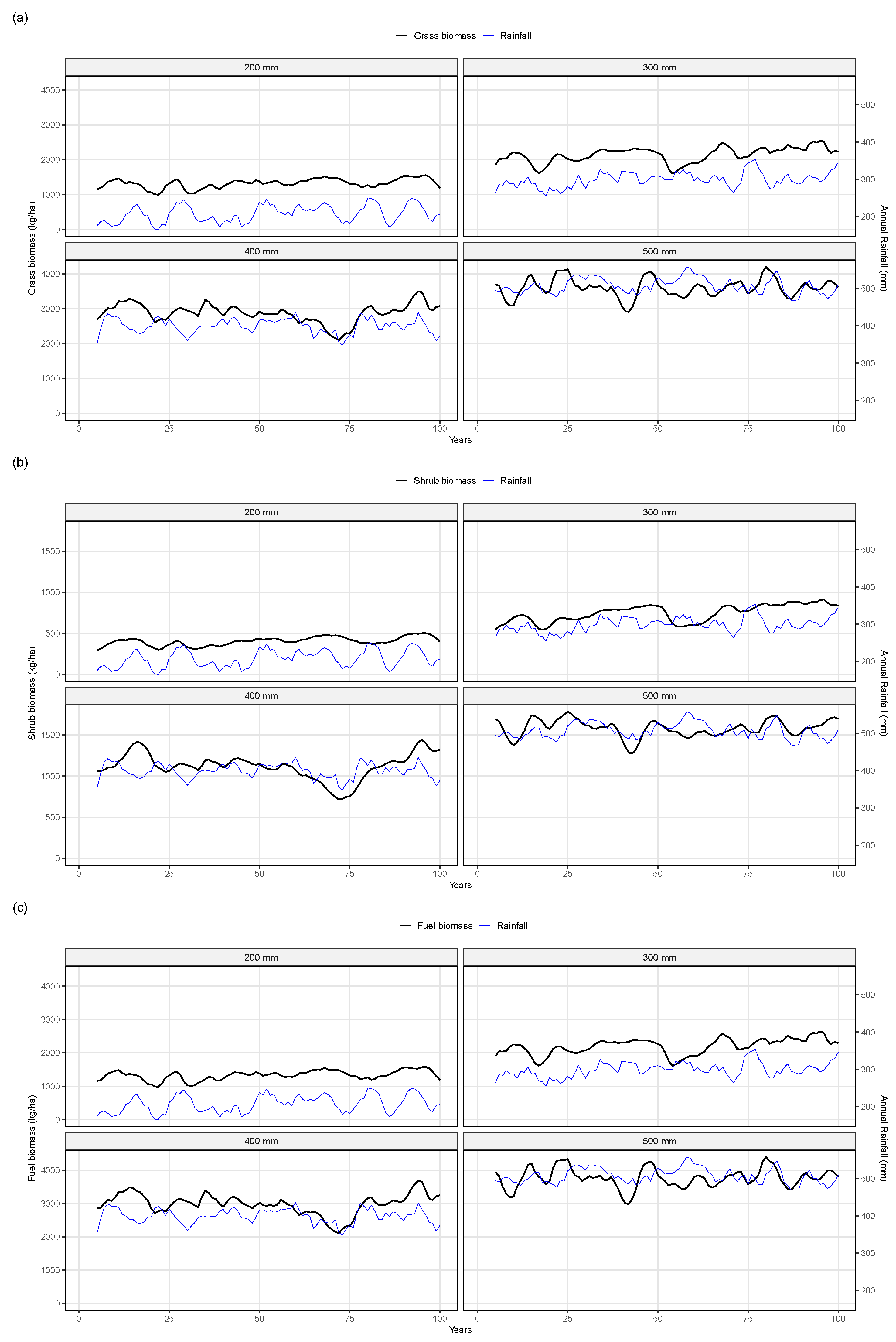

3.2. Variation in Biomass over Time

Overall, biomass in the system increased with rainfall, with both the amount of biomass and its year-to-year variability becoming more pronounced under wetter conditions. Grass, shrub, and fuel biomass followed similar trends, showing higher peaks and wider fluctuations as rainfall increased.

Grass biomass in the drier scenario, around 200 mm rainfall, ranged from about 1000 kg/ha in the lower years to nearly 2000 kg/ha in the higher years, remaining relatively stable over time. Under 300 mm rainfall, grass biomass increased, varying between approximately 1200 and 2200 kg/ha, with fluctuations beginning to correspond more closely to interannual changes in rainfall. In intermediate rainfall conditions, grass biomass displayed more variation, with lower values around 1300 kg/ha and higher values reaching 2500 kg/ha, showing distinct peaks and troughs over the years. In the wetter scenario, around 500 mm rainfall, grass biomass became highly dynamic, fluctuating between roughly 1500 and 2700 kg/ha, with the highest values occurring during wet years and more pronounced year-to-year oscillations.

Shrub biomass was generally lower than grass across all rainfall levels. In the drier scenario at 200 mm rainfall, shrub biomass ranged from about 500 kg/ha in low years to 1000 kg/ha in high years, showing relatively minor variation over time. Under intermediate rainfall conditions, shrub biomass increased, varying between roughly 600 and 1300 kg/ha, with more noticeable year-to-year changes. In wetter conditions around 500 mm rainfall, shrub biomass ranged from approximately 900 to 1500 kg/ha, with peaks occurring during wetter years and more evident variation compared to drier conditions.

Fuel biomass, representing the combined contribution of grasses and shrubs, reflected the additive patterns of both vegetation types. In the drier scenario, fuel biomass varied between about 1500 and 2000 kg/ha, showing little change from year to year. Under 400 mm rainfall, fuel biomass increased, ranging from approximately 1700 to 2800 kg/ha, with more dynamic fluctuations reflecting changes in both grass and shrub biomass. In the wetter scenario around 500 mm rainfall, fuel biomass ranged from about 2100 to over 3200 kg/ha, with pronounced year-to-year variation and noticeable peaks during wet years, highlighting the combined effect of both vegetation components.

Across all types of biomass, the overall pattern shows that both the amount and variability of biomass increased along the rainfall gradient. Grass biomass consistently had the highest values and the most pronounced fluctuations, shrub biomass was lower and showed slower increases with rainfall, and fuel biomass amplified the combined patterns of grass and shrub growth, exhibiting increasingly dynamic changes in wetter conditions.

Figure 2.

Variation in simulated biomass for grass (a), shrub and fuel (c) over 100 year period across different rainfall regimes.

Figure 2.

Variation in simulated biomass for grass (a), shrub and fuel (c) over 100 year period across different rainfall regimes.

3.3. Coupled Rainfall, Biomass-Fire Interaction

The results reveal a clear coupling between rainfall, vegetation biomass, and fire behaviour. Rainfall structured both the occurrence and intensity of fires, while simultaneously shaping the accumulation and variability of biomass.

In the drier rainfall regime, fire events were most frequent but consistently weak in intensity. Vegetation biomass remained low, with grasses forming the dominant component and shrubs contributing less, and variation across years was limited.

At intermediate rainfall levels, fire remained relatively frequent, though with more irregular temporal patterns. Fire intensity increased compared to drier conditions, and vegetation biomass also rose, with both grasses and shrubs showing more noticeable fluctuations. Fuel biomass became more dynamic, reflecting the combined variability of the vegetation components.

In wetter regimes, fire frequency declined, often with extended intervals without burning. However, when fires did occur, they were substantially more intense than in drier or intermediate conditions. Biomass accumulation reached higher levels, and year-to-year variability became more pronounced, with grasses showing strong peaks and troughs and shrubs responding more gradually. Fuel biomass amplified these patterns, displaying wide oscillations that closely tracked rainfall conditions.

Overall, the patterns show that drier conditions support frequent but low-intensity fires under relatively stable and limited biomass, while wetter conditions lead to infrequent but highly intense fires under abundant and variable biomass. Intermediate regimes occupy a transitional state, where both fire and biomass show greater variability over time.

Figure 3.

Variation in simulated (a) grass biomass, (b) shrub biomass, (c) fuel biomass, (d) fire intensity, and (e) fire frequency across rainfall regimes.

Figure 3.

Variation in simulated (a) grass biomass, (b) shrub biomass, (c) fuel biomass, (d) fire intensity, and (e) fire frequency across rainfall regimes.

Table 2.

Summary of savanna fire-vegetation simulation outcomes across rainfall regimes.

Table 2.

Summary of savanna fire-vegetation simulation outcomes across rainfall regimes.

| Rainfall regime |

Grass biomass |

Woody biomass |

Fuel biomass |

Fire frequency |

Fire intensity |

Dominant dynamics |

| 200 mm (drier) |

Low, stable |

Very low |

Low |

Frequent |

Very low |

Water-limited system; frequent but weak fires; stable low biomass dominated by grasses. |

| 300 mm (mesic) |

Moderate, fluctuating |

Low-moderate |

Moderate |

Frequent |

Moderate |

Fire acts as a key regulator; grasses recover quickly, woody biomass partly constrained. |

| 400 mm (mesic) |

High, fluctuating |

Moderate-high |

High |

Less frequent |

High |

Peak fire intensity; strong grass-fire feedback maintains dynamic balance with woody biomass. |

| 500 mm (wetter) |

Very high, variable |

High |

Very high |

Occasional |

Very high |

Abundant biomass with infrequent but severe fires; potential for gradual woody expansion. |

4. Discussion

This study elucidate a tightly coupled interplay among rainfall, fire dynamics, and vegetation biomass within savanna ecosystems and how such changes in accordance with varying microclimatic settings. Rainfall emerges as the principal determinant of primary productivity, which, in turn, exerts a critical influence on fire regimes through its modulation of fuel availability. Similar studies [

3,

12] found that fire behavior is predominantly governed by rainfall-mediated biomass accumulation.

Results confirm the hypothesis that savanna fire dynamics is mediated by microclimatic conditions which informs fuel availability and flamability. In arid savannas (200 mm/year), grass biomass constitutes the principal component of the combustible fuel load, given the typically sparse tree cover [

30]. Although total biomass is comparatively low, the extant grasses desiccate readily, rendering them highly flammable and facilitating frequent ignition. Fires in these systems are characterised by high frequency yet low intensity, occurring in a patchy manner and eliciting only modest reductions in aboveground biomass. Consequently, fire exerts a limited regulatory influence on vegetation dynamics under such xeric conditions.

In mesic savannas (300–400 mm/year), the feedbacks between biomass accumulation and fire dynamics are most pronounced. Elevated grass biomass sustains recurrent, relatively intense fires that can reduce fuel loads by 50–70%, producing marked oscillations in vegetation structure and fire activity over successive seasons. Trait-based empirical studies demonstrate substantial interspecific variation in grass flammability, determined by factors such as biomass, moisture content, and leaf surface area, which collectively modulate fire behavior [

30]. In particular, increased grass biomass coupled with reduced moisture content enhances fuel ignitability, combustibility, and fire persistence.

Concurrently, tree density begins to exert a regulatory effect on fire dynamics in these systems. Increasing canopy cover diminishes grass biomass and replaces it with leaf litter, which is intrinsically less flammable [

28,

29]. Dense tree canopies further alter the microclimatic milieu, reducing ambient temperature, increasing relative humidity, attenuating wind speed, and elevating fuel moisture content, all of which collectively suppress ignition probability, rate of spread, flame height, and fire-line intensity [

28,

29]. This results in less frequent fire These findings are consistent with experimental and observational studies across savanna–forest ecotones; for instance, in the Brazilian Cerrado, metrics of fire behavior, including ignition success, rate of spread, and fire-line intensity, decline progressively with increasing tree density, largely due to reductions in grass biomass and modifications of local microclimate [

28,

31]. Moreover, studies on the African savannas indicate that shifts in grass species composition induced by increasing canopy cover can attenuate fire intensity even prior to significant reductions in total grass biomass. Collectively, these findings suggest that flammability declines progressively along a gradient of increasing tree density, rather than exhibiting an abrupt threshold, and is further modulated by temporal variation in humidity.

In humid savannas (500 mm/year), although fuel loads remain substantial and fire continues to occur, rapid post-fire regrowth stabilizes biomass, indicative of the system’s resilience to repeated disturbance. Elevated humidity and dense canopy cover jointly mitigate fire activity by reducing the availability of highly flammable grass, enhancing fuel moisture, and moderating local temperature and wind dynamics [

28]. Temporal variability in rainfall further modulates these dynamics. During periods of above-average rainfall, biomass accumulation is accelerated, enhancing the potential for fire, whereas drought periods reduce fuel accumulation and fire occurrence. Critically, the magnitude of this rainfall-driven effect is contingent upon canopy structure: dense tree cover suppresses grassy fuel accumulation and alters the microclimate to inhibit ignition and fire spread, whereas open, grass-dominated systems remain highly susceptible to fire. These interactions underscore that the ecological role of fire in savanna ecosystems is neither uniform nor static, but is intricately mediated by vegetation structure, functional traits, and prevailing environmental conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the ecological role of fire in savannas is highly context-dependent, shaped by rainfall, fuel availability, vegetation recovery, and local humidity. In arid systems, dry and flamable biomass attract fire. In mesic regions, increasing tree cover results in less flamable grass biomass. In wet, humid savannas, high fuel loads coexist with elevated humidity, which reduces ignition probability and moderates fire intensity, making fire more of a stabilizing mechanism than a disturbance. These results confirm and extend existing knowledge of savanna fire ecology by quantitatively illustrating how fire-rainfall-biomass-humidity interactions vary along the rainfall gradient.

Management implications follow directly from these findings. In arid savannas, fire suppression may be critical to protect fragile vegetation. In mesic savannas, prescribed burns could maintain open landscapes and control woody encroachment if carefully managed. In wet, humid savannas, moderate, regular fires may sustain grass-tree coexistence and reduce the risk of extreme wildfires, while accounting for lower ignition probabilities due to humidity. Understanding rainfall- and humidity-mediated fire dynamics is essential for biodiversity conservation, ecosystem service maintenance, and enhancing resilience under changing climatic conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N. and J.A.; methodology, J.N.; software, J.N.; validation, M.H., J.N. and J.A.; formal analysis, J.N.; investigation, J.N.; resources, J.A.; data curation, J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.N.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; visualization, J.N.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, J.N.; funding acquisition, J.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The simulation code used in this study is available from the corresponding author at a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Professor Norman Owen-Smith from the University of the Witwatersrand for guidance on ecological modelling.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sankaran, M.; Hanan, N.P.; Scholes, R.J.; Ratnam, J. Determinants of woody cover in African savannas. Nature 2005, 438, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholes, R.J.; Archer, S.R. Tree–grass interactions in savannas. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1997, 28, 517–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synodinos, A.D.; Tietjen, B.; Lohmann, D.; Jeltsch, F. The impact of inter-annual rainfall variability on African savannas changes with mean rainfall. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2018, 437, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marston, C.G.; Wilkinson, D.M.; Reynolds, S.C.; Louys, J.; O’Regan, H.J. Water availability is a principal driver of large-scale land cover spatial heterogeneity in sub-Saharan savannahs. Landscape Ecology 2019, 34, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Milodowski, D.T.; Smallman, T.L.; Dexter, K.G.; Hegerl, G.C.; McNicol, I.M.; O’Sullivan, M.; Roesch, C.M.; Ryan, C.M.; Sitch, S.; et al. Precipitation–fire functional interactions control biomass stocks and carbon exchanges across the world’s largest savanna. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 1597–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C.E.R.; Archibald, S.A.; Hoffmann, W.A.; Bond, W.J. Deciphering the distribution of the savanna biome. New Phytologist 2014, 204, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.J.; Keeley, J.E. Fire as a global ’herbivore’: The ecology and evolution of flammable ecosystems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2005, 20, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, S.; Roy, D.P.; Van Wilgen, B.W.; Scholes, R.J.; Roberts, G.; Boschetti, L. Drivers of fire and burnt area in Southern Africa as revealed by remote sensing. Global Change Biology/International Journal of Wildland Fire 2009, 15/19, 613–630/861–878. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.I.; Bond, W.J.; Trollope, W.S.W. Fire, resprouting and variability: A recipe for grass–tree coexistence in savanna. Journal of Ecology 2000, 88, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staver, A.C.; Archibald, S.; Levin, S.A. Tree cover in sub-Saharan Africa: Rainfall and fire constrain forest and savanna as alternative stable states. Ecology/Science 2011, 92/334, 1063–1072/230–232. [CrossRef]

- Govender, N.; Trollope, W.S.W.; Van Wilgen, B.W. The effect of fire season, fire frequency, rainfall and management on fire intensity in savanna vegetation in South Africa. Journal of Applied Ecology 2006, 43, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C.E.R.; Anderson, T.M.; Sankaran, M.; Higgins, S.I.; Archibald, S.; Hoffmann, W.A.; Hanan, N.P.; Williams, R.J.; Fensham, R.J.; Felfili, J.; et al. Savanna vegetation–fire–climate relationships differ among continents. Science 2011, 334, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeltsch, F.; Weber, G.E.; Grimm, V. Ecological buffering mechanisms in savannas: A unifying theory of long-term tree-grass coexistence. Plant Ecology 2000, 150, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, D. A Conceptual Model of Vegetation Dynamics in the Semiarid Highland Savanna of Namibia, with Particular Reference to Bush Thickening by Acacia mellifera. Journal of Arid Environments 2008, 72, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishna, T.; Rifai, S.W.; Ratnam, J.; Oliveras Menor, I.; Stevens, N.; Malhi, Y. The distribution and drivers of tree cover in savannas and forests. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2024, 8, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, F. Precipitation and temperature drive woody vegetation dynamics in savannas. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 2023, 9, 70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, A.T.; Uno, K.T.; Berke, M.A.; Russell, J.M.; Scholz, C.A.; Marlon, J.R.; Staver, A.C. Nonlinear rainfall effects on savanna fire activity across the tropics. Global Change Biology 2023, 29, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laris, P. Determinants of fire intensity in working landscapes of an African savanna. Fire Ecology 2020, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Boucher, P.B.; Hockridge, E.G.; Davies, A.B. Effects of long-term fixed fire regimes on African savanna vegetation. Journal of Ecology 2023, 111, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, B.; Thiel, M.; Forkuor, G.; Mouillot, F.; Laris, P.; Tondoh, E.J.; Sponholz, B. Fire Impacts, vegetation Recovery, and environmental heterogeneity in savannas. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2025, 34, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindermann, L.; Sandhage‐Hofmann, A.; Amelung, W.; Borner, J.; Dobler, M.; Fabiano, E. Natural and Human Disturbances Have Non-Linear Effects on Carbon Storage in African Savannas. Global Change Biology 2025, 31, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accatino, F.; De Michele, C.; Vezzoli, R.; Donzelli, D.; Scholes, R.J. Tree–grass co-existence in savanna: Interactions of rain and fire. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2010, 267, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.J.; Midgley, G.F. Ecology of sprouting in woody plants: The persistence niche. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2001, 16, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucini, G.; Hanan, N.P. A continental-scale analysis of tree cover in African savannas. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2007, 16, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, R.J.; Roderick, M.L.; McVicar, T.R.; Farquhar, G.D. Impact of CO2 fertilization on maximum foliage cover across the globe’s warm, arid environments. Geophysical Research Letters 2013, 40, 3031–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, T.M.; Caylor, K.K.; Levin, S.A.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Positive feedbacks promote power-law clustering of Kalahari vegetation. Nature 2005, 449, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholes, R.J. Convex relationships in ecosystems containing mixtures of trees and grass. Environmental and Resource Economics 2003, 26, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, B.M.; Power, C.R.; Abreu, R.C.R.; Durigan, G.; Rossatto, D.R.; Hoffmann, W.A. Flammability thresholds or flammability gradients? Determinants of fire across savanna–forest transitions. New Phytologist 2020, 228, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, L.D.; Murphy, B.P.; Williamson, G.J.; Cochrane, M.A.; Jolly, W.M.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Does inherent flammability of grass and litter fuels contribute to continental patterns of landscape fire activity? Journal of Biogeography 2017, 44, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.J.; Archibald, S.; Osborne, C.P. Savanna fire regimes depend on grass trait diversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2022, 37, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.W.; Oliveras, I.; Abernethy, K.A.; Jeffery, K.J.; Lehmann, D.; Edzang Ndong, J.; McGregor, I.; Belcher, C.M.; Bond, W.J.; Malhi, Y.S. Grass species flammability, not biomass, drives changes in fire behavior at tropical forest-savanna transitions. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2018, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).