Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

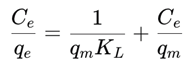

2.1. FTIR Analysis

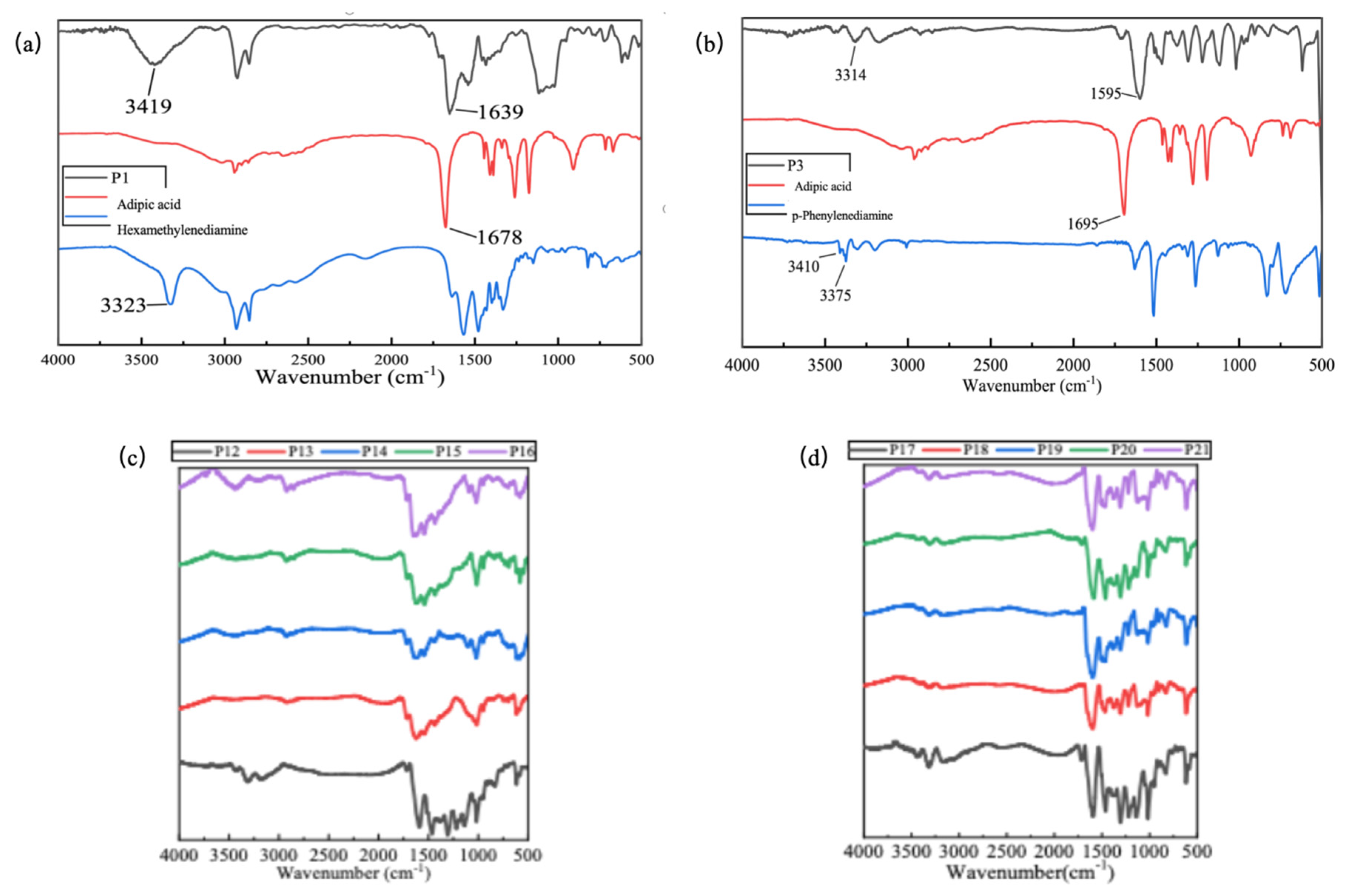

2.2. XRD Analysis

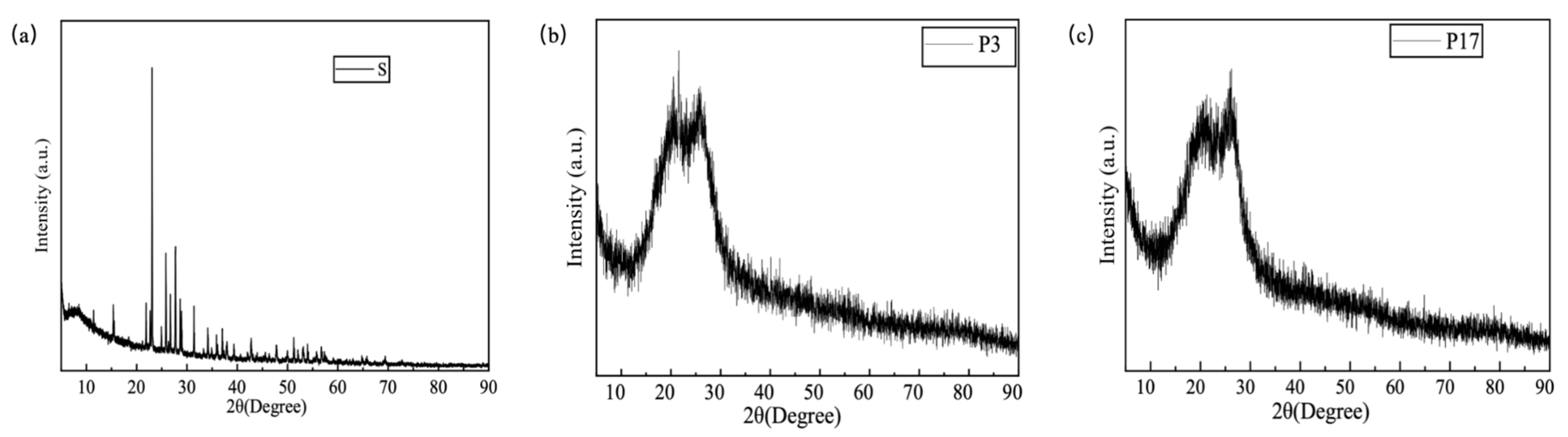

2.3. SEM Analysis

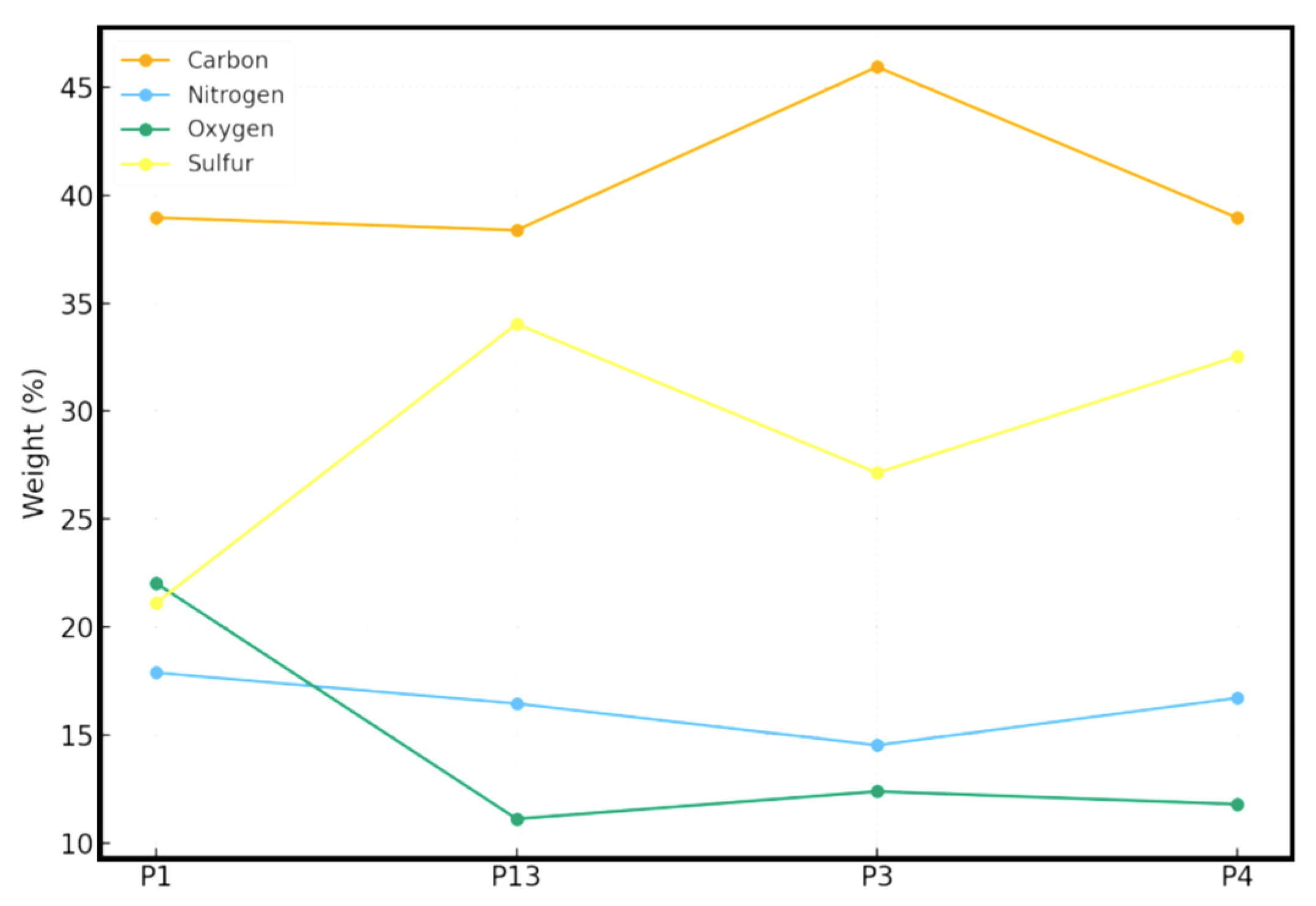

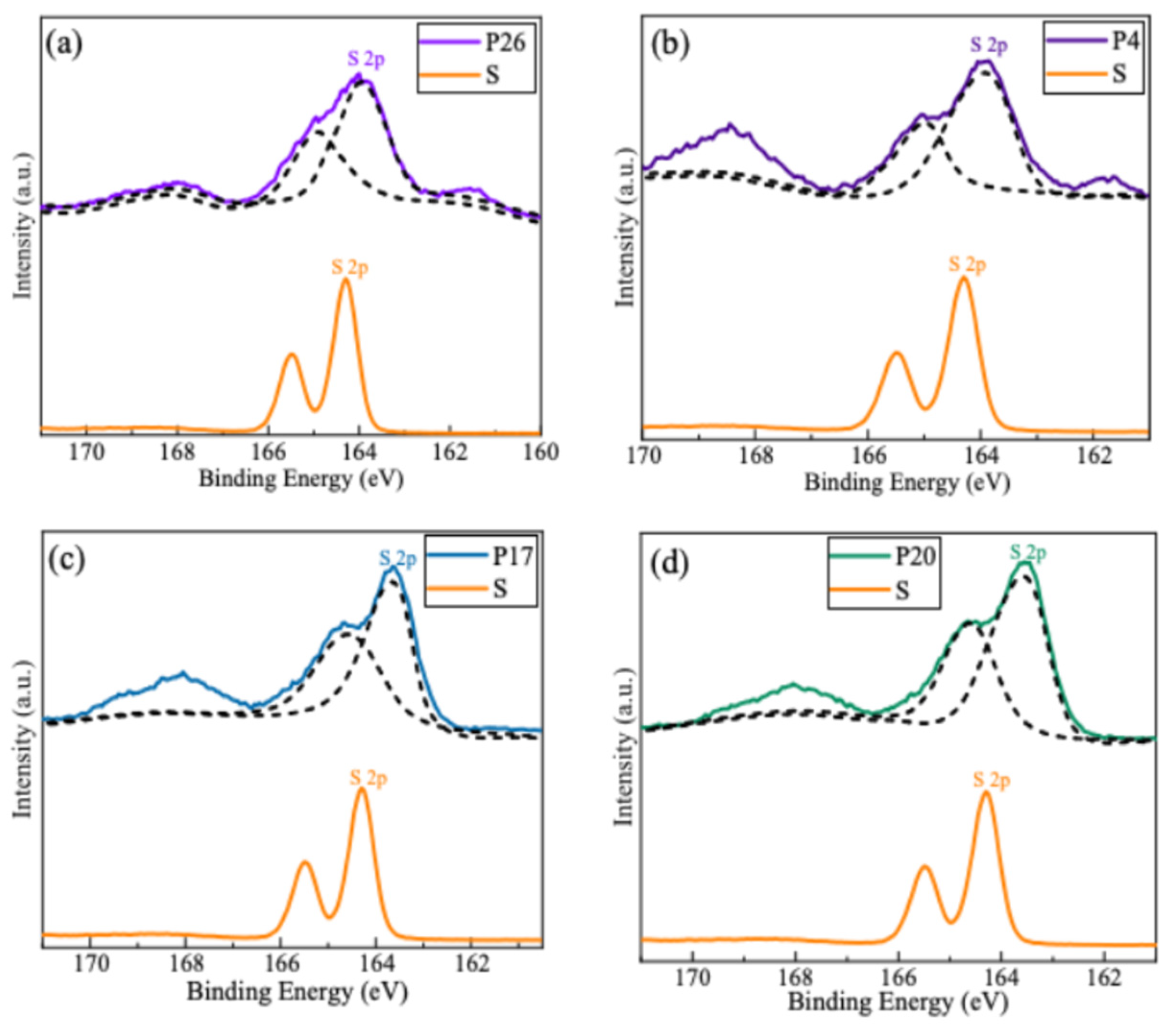

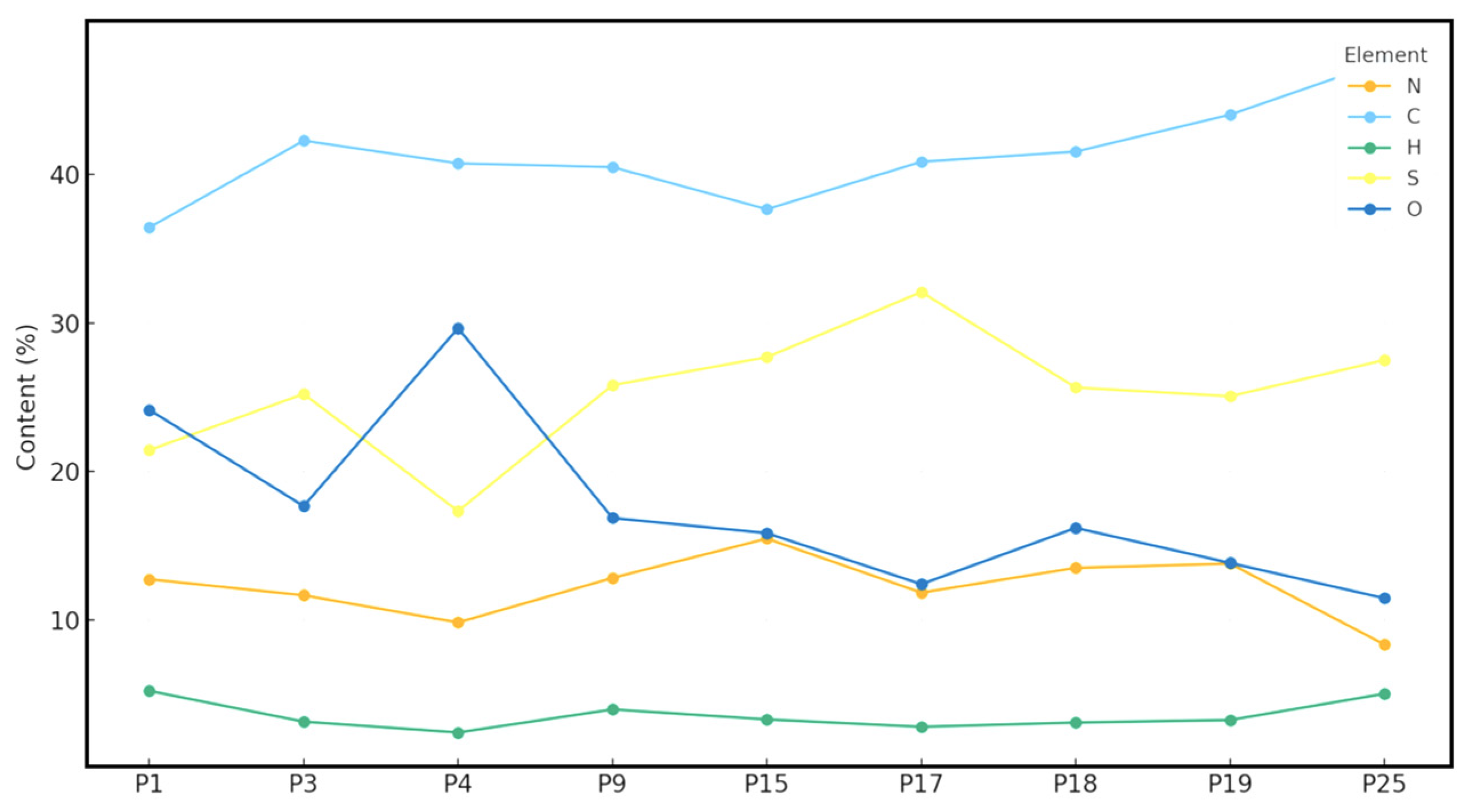

2.4. XPS Analysis

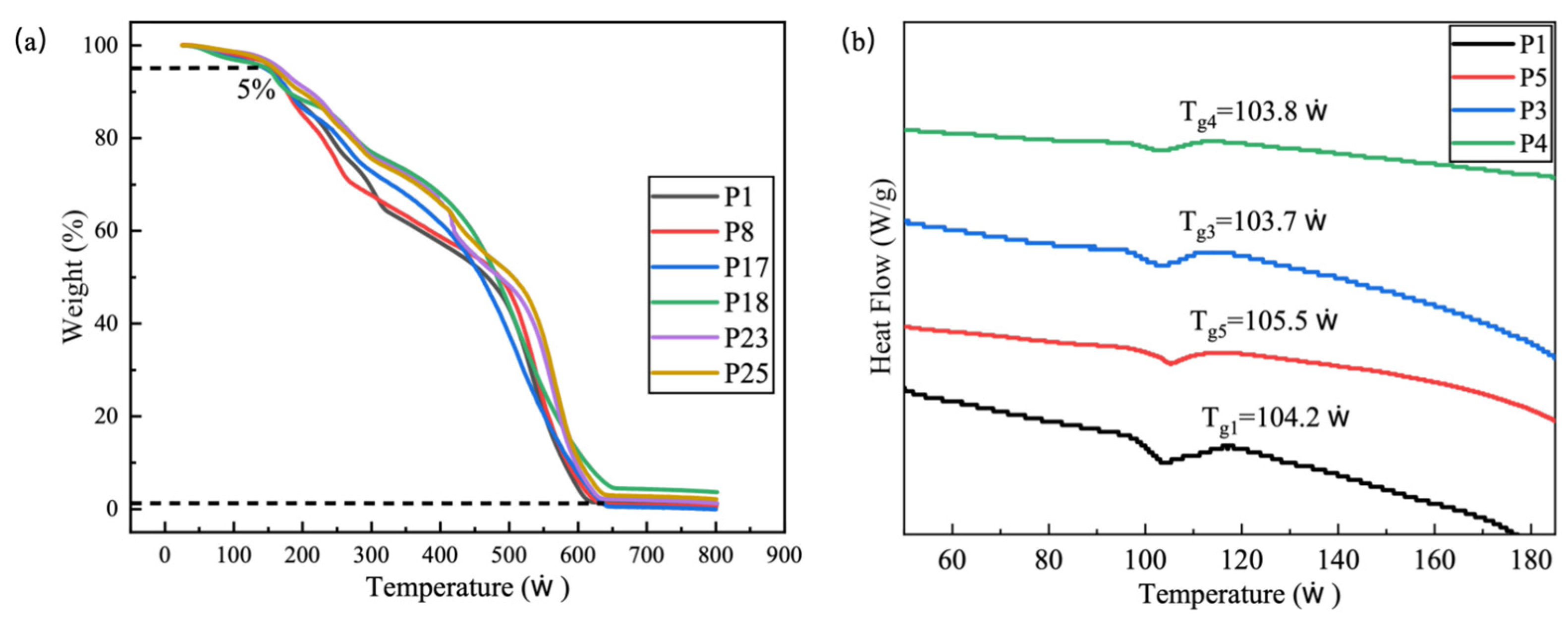

2.5. TG Analysis

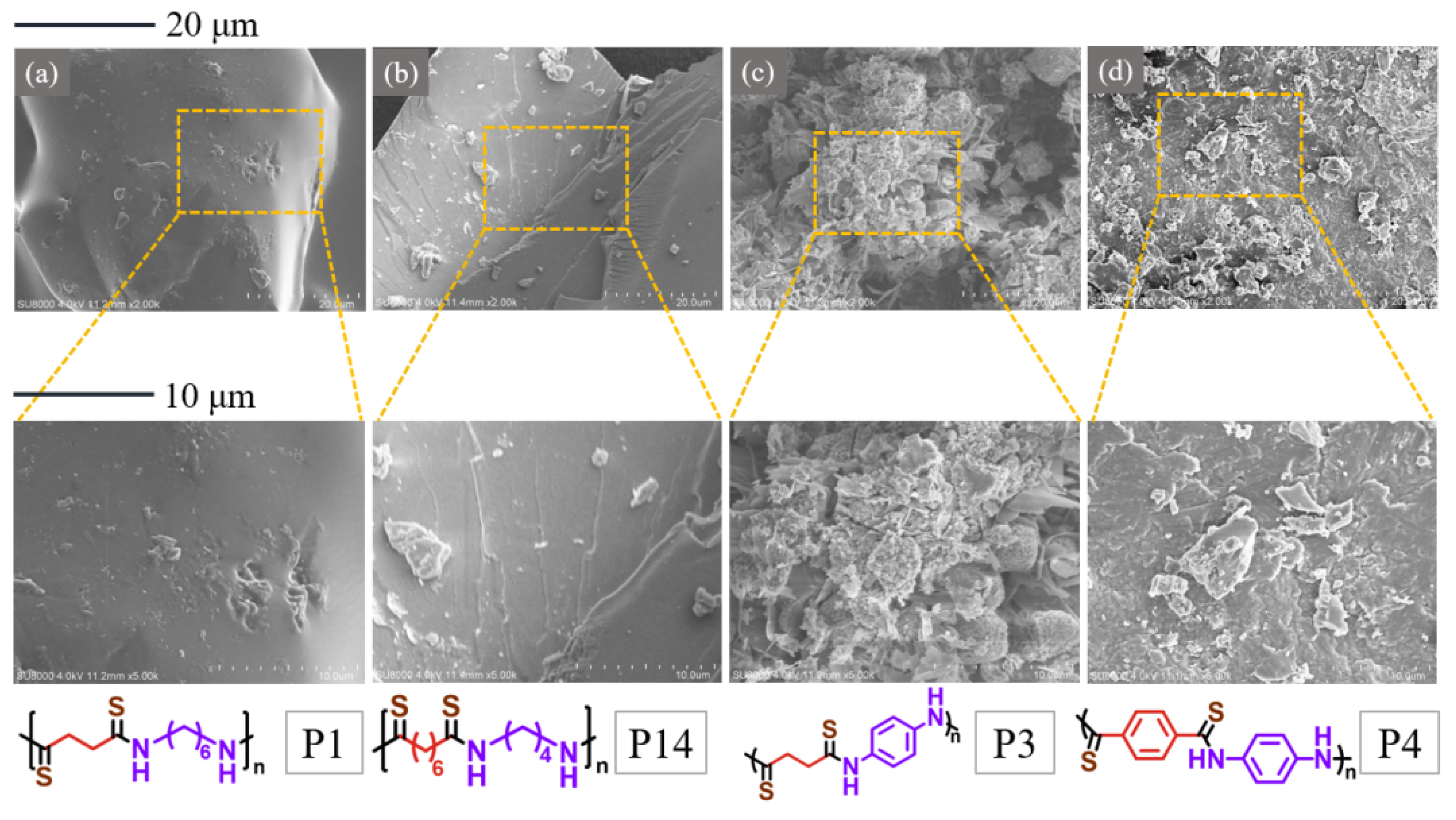

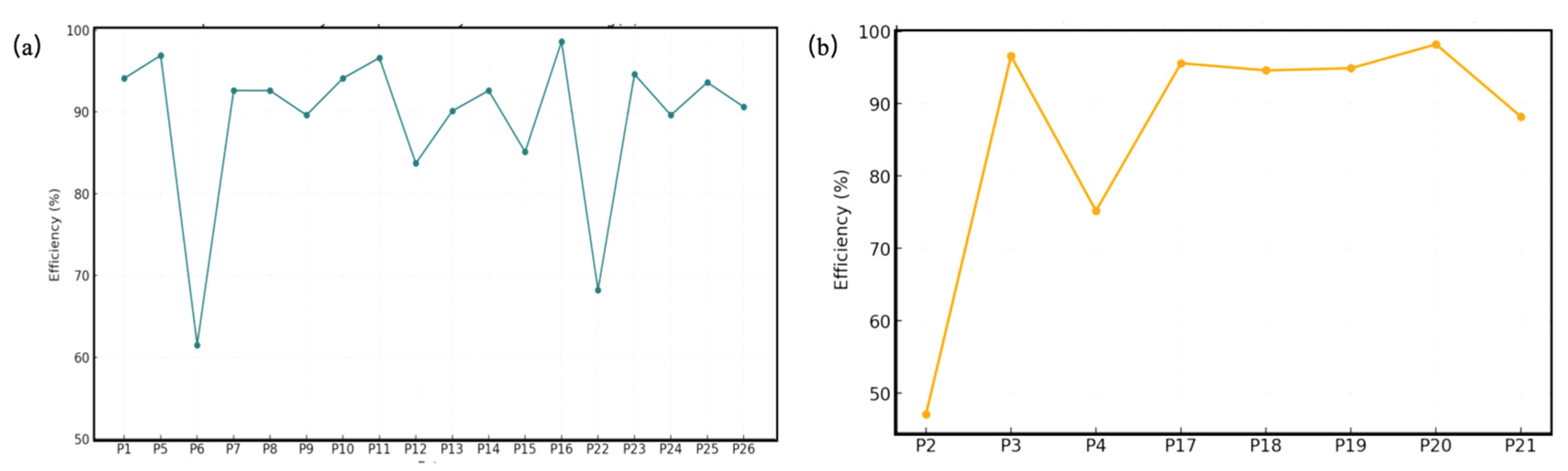

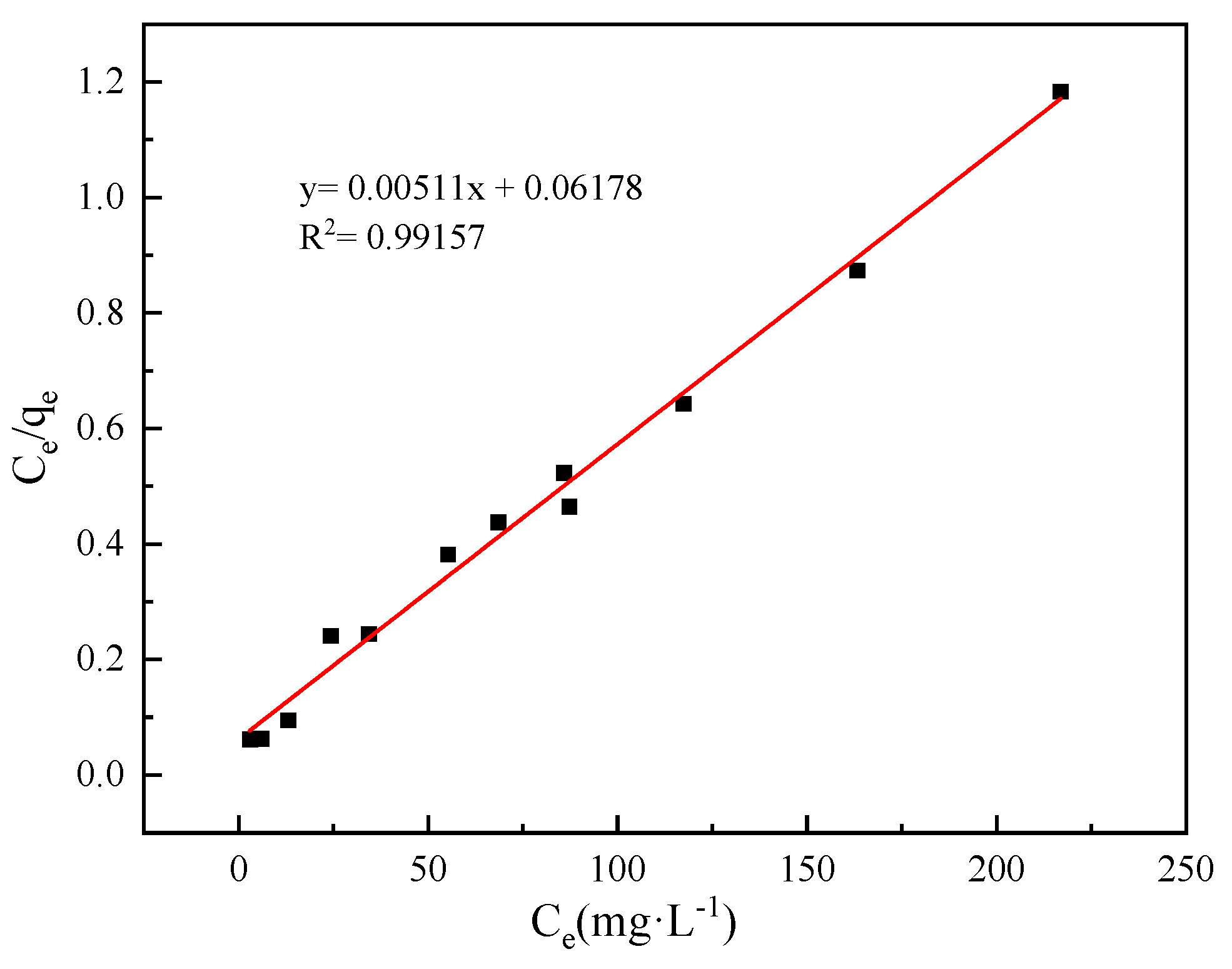

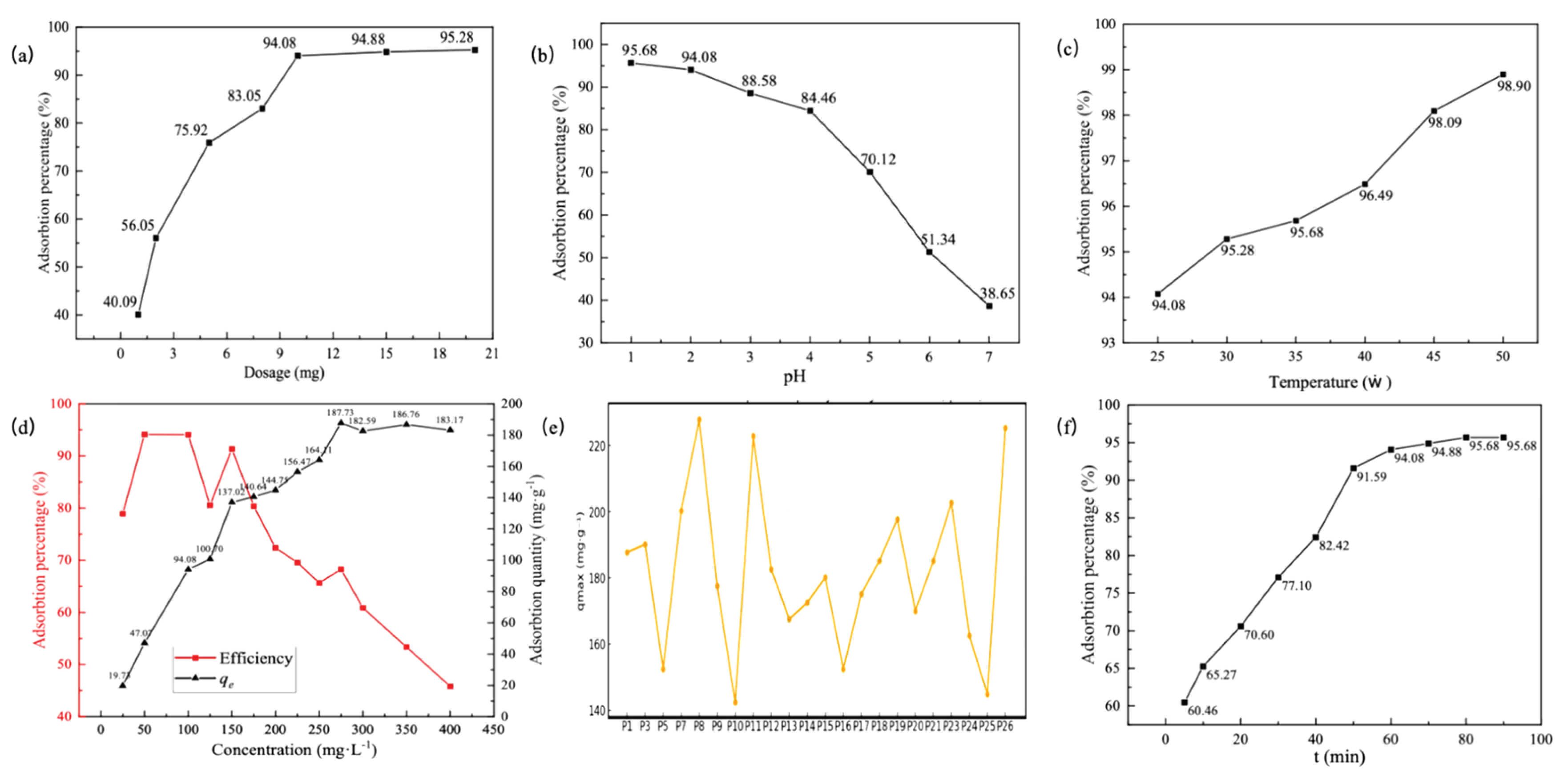

2.6. Adsorption of Hg(II) from Aqueous Solution

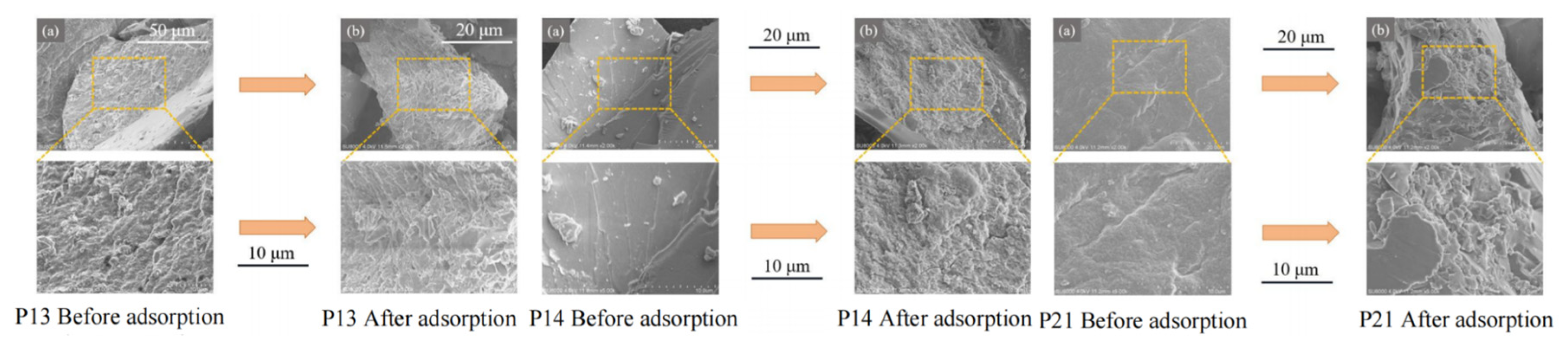

2.7. Characterization of Polythioamides After Hg(II) Adsorption – SEM Analysis

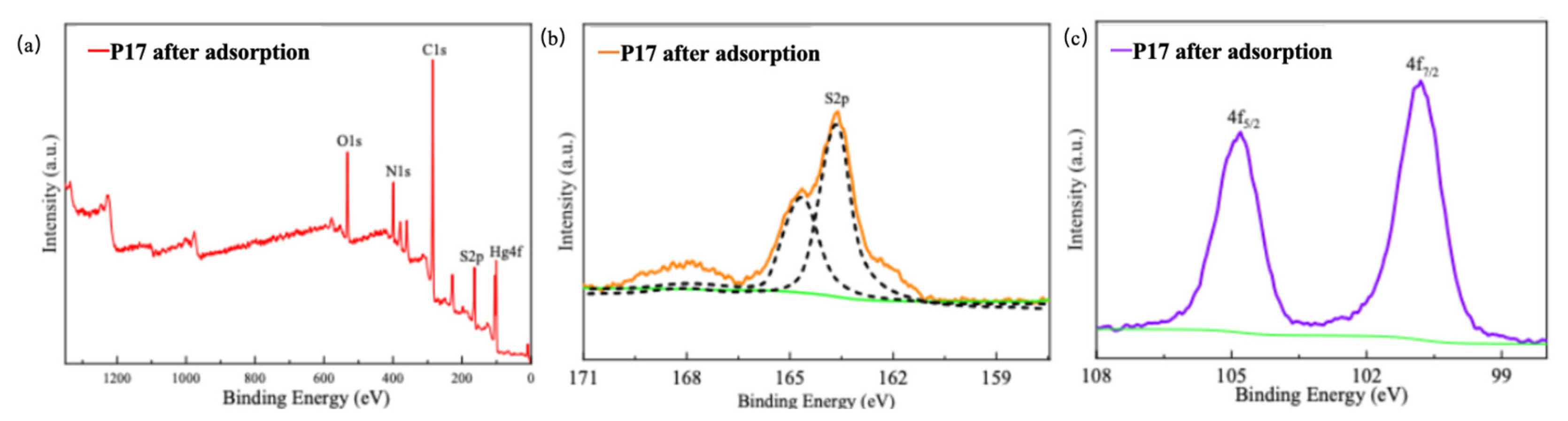

2.8. Characterization of Polythioamides After Hg(II) Adsorption (XPS) Analysis

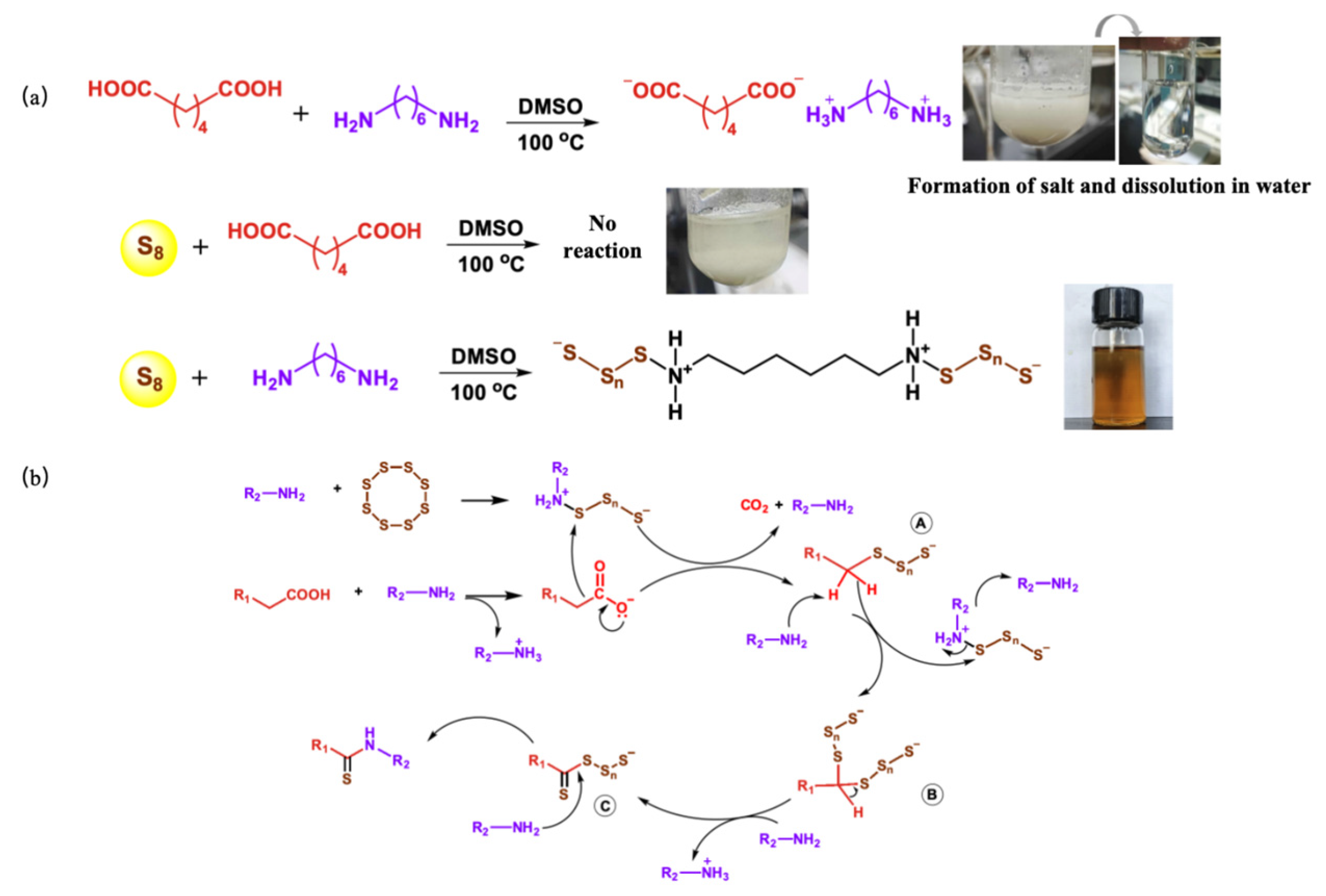

2.9. Polymerization Mechanism Verification

3. Experiment

3.1. Materials and Methods

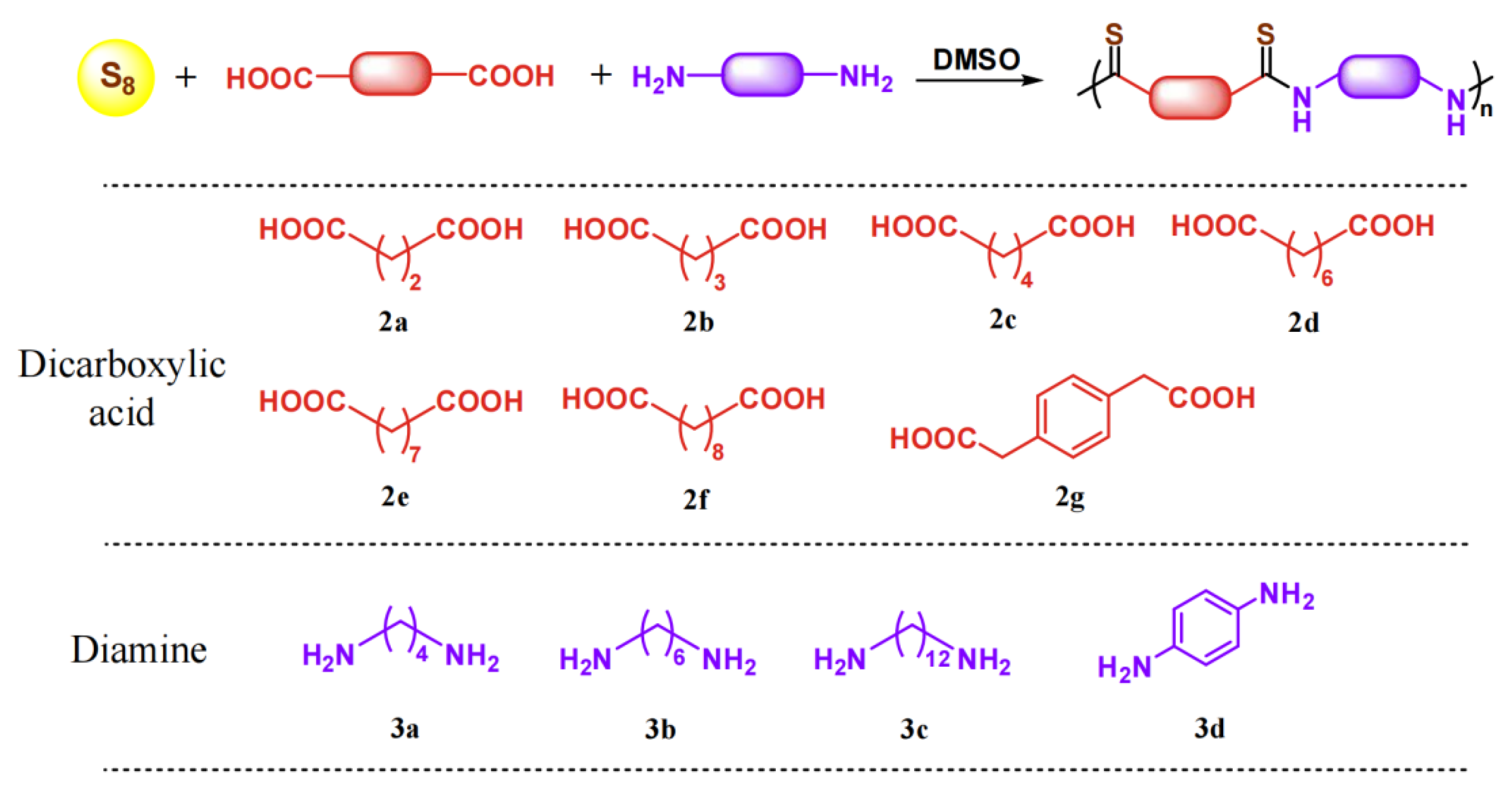

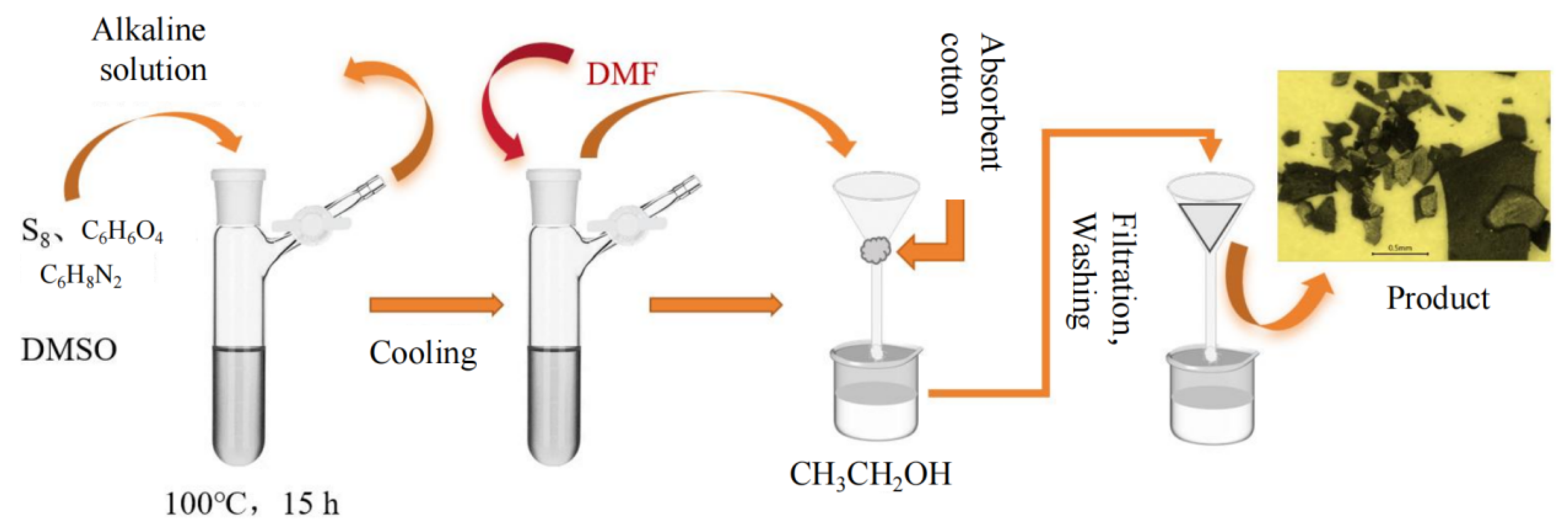

3.2. Synthesis of Polythioamides

3.3. Adsorption Performance of Polythioamides

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kutney, G. Sulfur: History, Technology, Applications and Industry; Elsevier: 2023.

- Ibrahim, A. Y.; Elgazzar, M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; et al. Performance Assessment and Process Optimization of a Sulfur Recovery Unit: A Real Starting-Up Plant. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighatjoo, F.; Ghorbani, A.; Rahimpour, M. R. Sulfur Recovery from Natural Gas. Adv. Nat. Gas: Form., Process., Appl. 2024, 7, 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ghumman, A. S. M.; et al. Evaluation of Properties of Sulfur-Based Polymers Obtained by Inverse Vulcanization: Techniques and Challenges. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2021, 29, 1333–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discekici, E. H.; et al. Evolution and Future Directions of Metal-Free Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7421–7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; et al. Emerging Functional Porous Polymeric and Carbonaceous Materials for Environmental Treatment and Energy Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1907006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amna, R.; Alhassan, S. M. A Comprehensive Exploration of Polysulfides, from Synthesis Techniques to Diverse Applications and Future Frontiers. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 4350–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsolami, E. S.; et al. One-Pot Multicomponent Polymerization Towards Heterocyclic Polymers: A Mini Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 1757–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. R.; et al. A Strategy to Develop Hydrophobic Stainless Steel Mesh through Three-Component Coupling Reaction with Presence of Sulfur. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 42, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brirmi, N. E. H.; et al. Progress and Challenges in Heterocyclic Polymers for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewater: A Review. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2024, 3, N-A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Z.; Yue, T. J.; Ren, B. H.; Lu, X. B.; Ren, W. M. Closed-Loop Recycling of Sulfur-Rich Polymers with Tunable Properties Spanning Thermoplastics, Elastomers, and Vitrimers. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; et al. One-Pot Synthesis of Fluorescent Guanidyl Sulfur Quantum Dots for Antibacterial and Antioxidant Performance. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 4580–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiernet, P.; Debuigne, A. Imine-Based Multicomponent Polymerization: Concepts, Structural Diversity and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 128, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.-J.; Ren, W.-M.; Lu, X.-B. Copolymerization Involving Sulfur-Containing Monomers. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 14038–14083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qin, A.; Tang, B. Z. Green Synthesis of Sulfur-Containing Polymers by Carbon Disulfide-Based Spontaneous Multicomponent Polymerization. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; et al. Metal-Free Multicomponent Polymerization to Access Polythiophenes from Elemental Sulfur, Dialdehydes, and Imides. Polym. Chem. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, R.; Tang, B. Z. Multicomponent Polymerization of Sulfur, Diynes, and Aromatic Diamines and Facile Tuning of Polymer Backbone Structures. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 6568–6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsen, C. V.; et al. Designed to Degrade: Tailoring Polyesters for Circularity. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 8473–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junyao; et al. Catalyst-Free Synthesis of Diverse Fluorescent Polyoxadiazoles for the Facile Formation and Morphology Visualization of Microporous Films and Cell Imaging. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 903–915. [Google Scholar]

- Rao; Chen, Q. Thio-Groups Decorated Covalent Triazine Polyamide (TTPA) for Hg2+ Adsorption: Efficiency and Mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112340.

- Chaoji; et al. Novel Triazine-Based Sulfur-Containing Polyamides: Preparation, Adsorption Efficiency and Mechanism for Mercury Ions. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 202, 112588.

- Guo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, B.; Ye, S.; Yi, W. Functional Polythioamides Derived from Thiocarbonyl Fluoride. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202313779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cao, T.; Du, J.; et al. The Bi-Modified (BiO)2CO3/TiO2 Heterojunction Enhances the Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics. Catalysts 2025, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; et al. Sulfhydryl Functionalized Chitosan-Covalent Organic Framework Composites for Highly Efficient and Selective Recovery of Gold from Complex Liquids. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasadakis, N.; Livanos, G.; Zervakis, M. Deconvolving the Absorbance of Methyl and Methylene Groups in the FT-IR 3000–2800 cm-Band of Petroleum Fractions. Spectroscopy 2013, 10, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Thombare, N.; et al. Comparative FTIR Characterization of Various Natural Gums: A Criterion for Their Identification. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 3372–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leewis, C. M.; et al. Ammonia Adsorption and Decomposition on Silica Supported Rh Nanoparticles Observed by in Situ Attenuated Total Reflection Infrared Spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 253, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basir, N. F. A.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of 5-Cyclopentylsulfanyl-3H- [1,3,4] Thiadiazole-2-Thione and Study of Its Single-Crystal Structure, FTIR Spectra, Thermal Behavior, and Antibacterial Activity. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 10745–10756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; et al. Effect of Elemental Sulfur (S8) on Carbon Isotope Analysis of n-Alkanes. Geochem. Int. 2023, 61, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Laser Microprobe Technique for Stable Carbon Isotope Analyses of Organic Carbon in Sedimentary Rocks. Geochem. J. 2000, 34, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D. Syntheses of Sulfur Rich Polymers and Their Application in Heavy Metal Capture. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Liverpool, 2025.

- Amna, R. Sulfur Copolymers via Emulsion Polymerization. Ph.D. Thesis, Khalifa University of Science, 2023.

- Huang, D.; et al. Minute-Scale Evolution of Free-Volume Holes in Polyethylenes During the Continuous Stretching Process Observed by in Situ Positron Annihilation Lifetime Experiments. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 4748–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demleitner, M.; et al. Influence of Block Copolymer Concentration and Resin Crosslink Density on the Properties of UV-Curable Methacrylate Resin Systems. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2200320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; et al. Mechanisms and Effects of Sunlight Exposure on Disperse-Dyed Aromatic Polysulfonamide Fibers. Surface Innov. 2025, 13, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; et al. High Rejection Seawater Reverse Osmosis TFC Membranes with a Polyamide-Polysulfonamide Interpenetrated Functional Layer. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 715, 123507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; et al. Lightweight, Superelastic, and Temperature-Resistant rGO/Polysulfoneamide-Based Nanofiber Composite Aerogel for Wearable Piezoresistive Sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 14641–14651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, A.; et al. Hyperbranched Multiple Polythioamides Made from Elemental Sulfur for Mercury Adsorption. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, E. T.; et al. Trisurethane Functionalized Sulfonamide Based Polymeric Sorbent: Synthesis, Surface Properties and Efficient Mercury Sorption from Wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 325, 124606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S. A.; et al. Development of Sulfurized Polythiophene-Silver Iodide-Diethyldithiocarbamate Nanoflakes Toward Record-High and Selective Absorption and Detection of Mercury Derivatives in Aquatic Substrates. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 440, 135896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).