Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

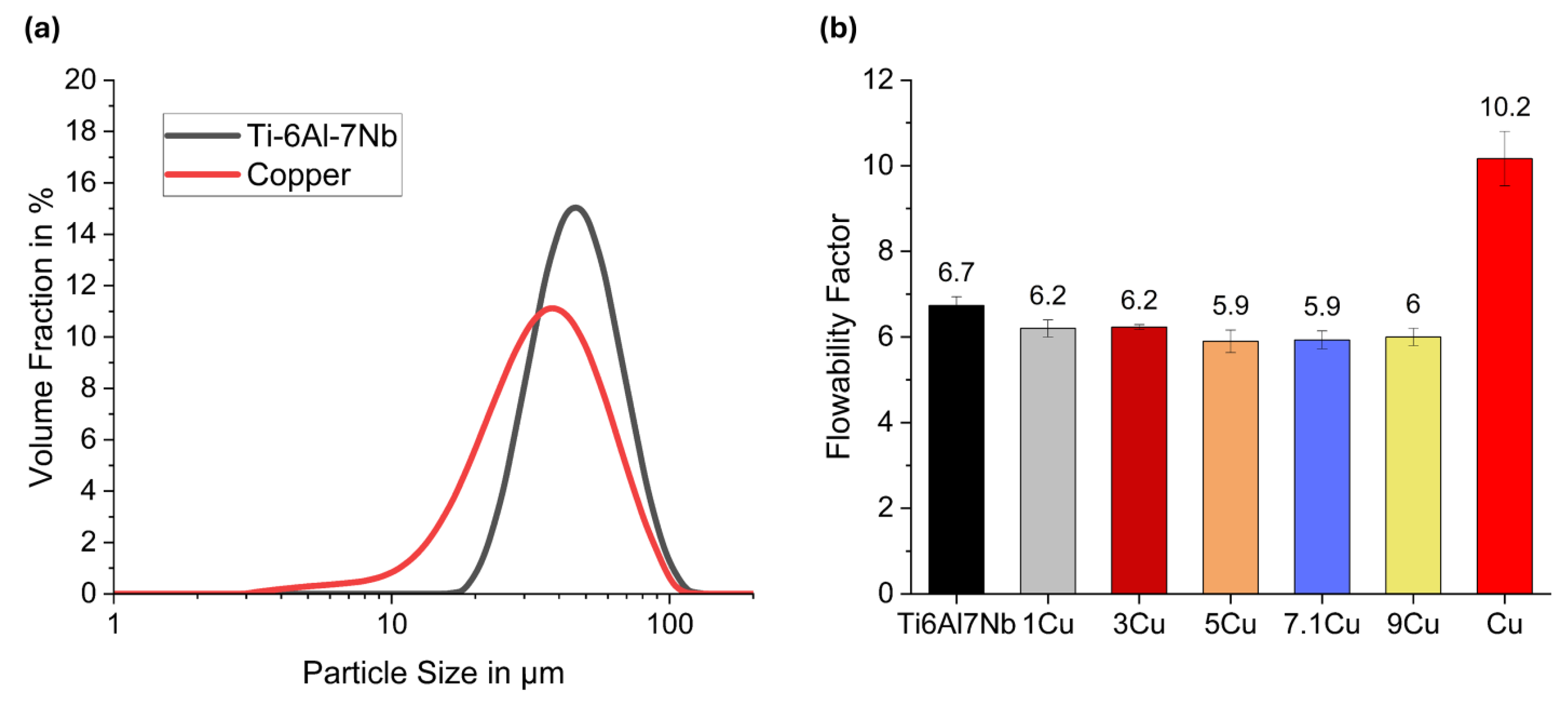

2.1. Powder Mixing and Characterisation

3. Results

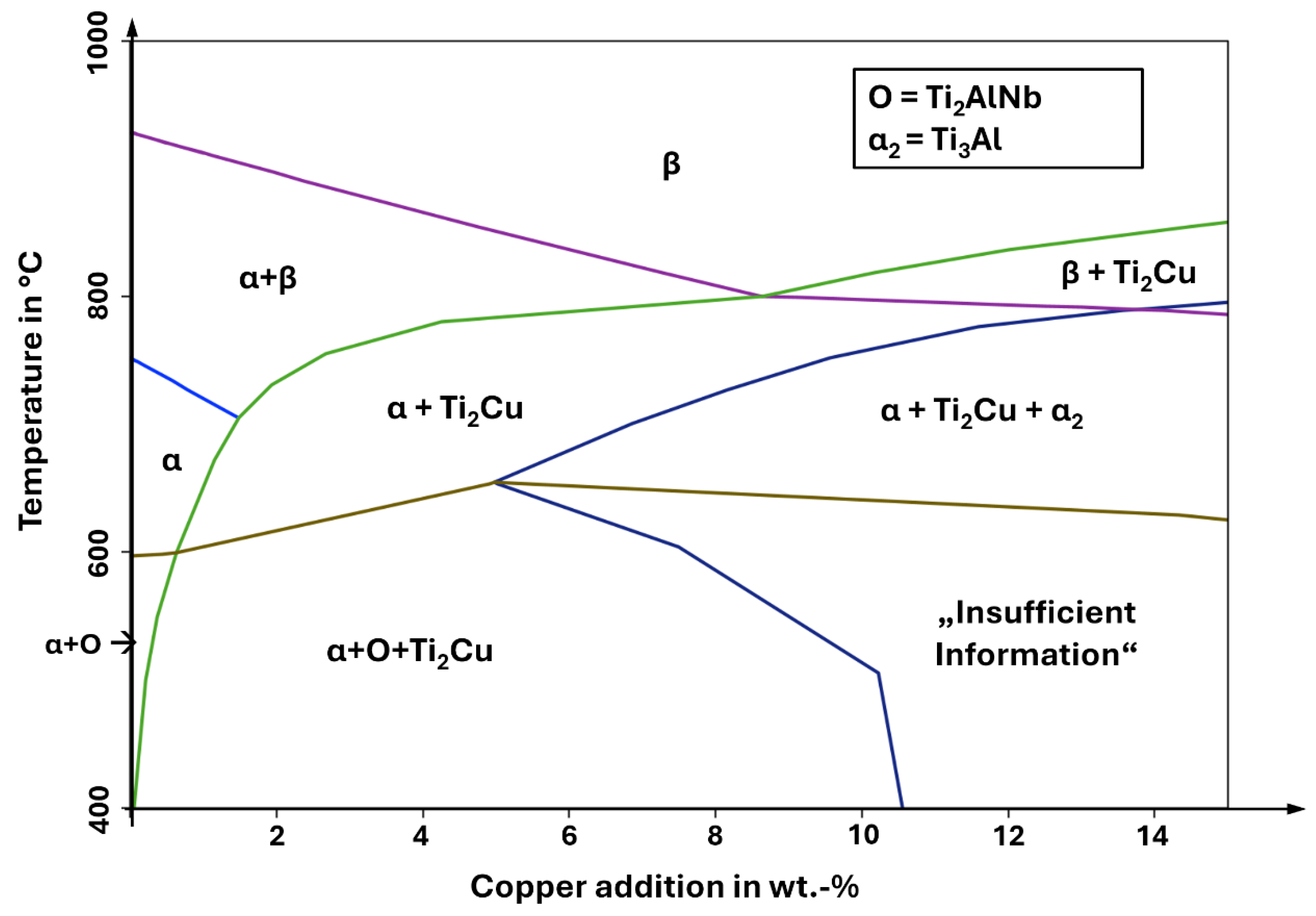

3.1. Calculated Pseudo-Binary Phase Diagram

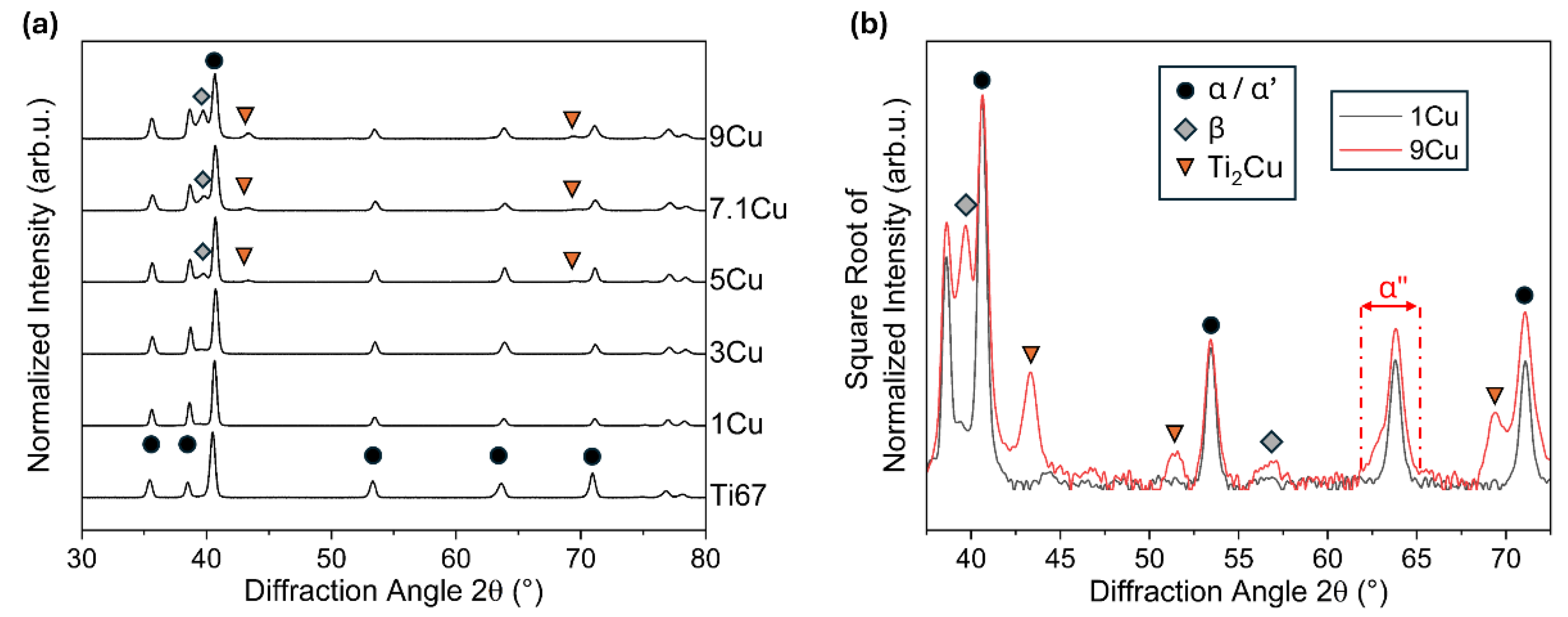

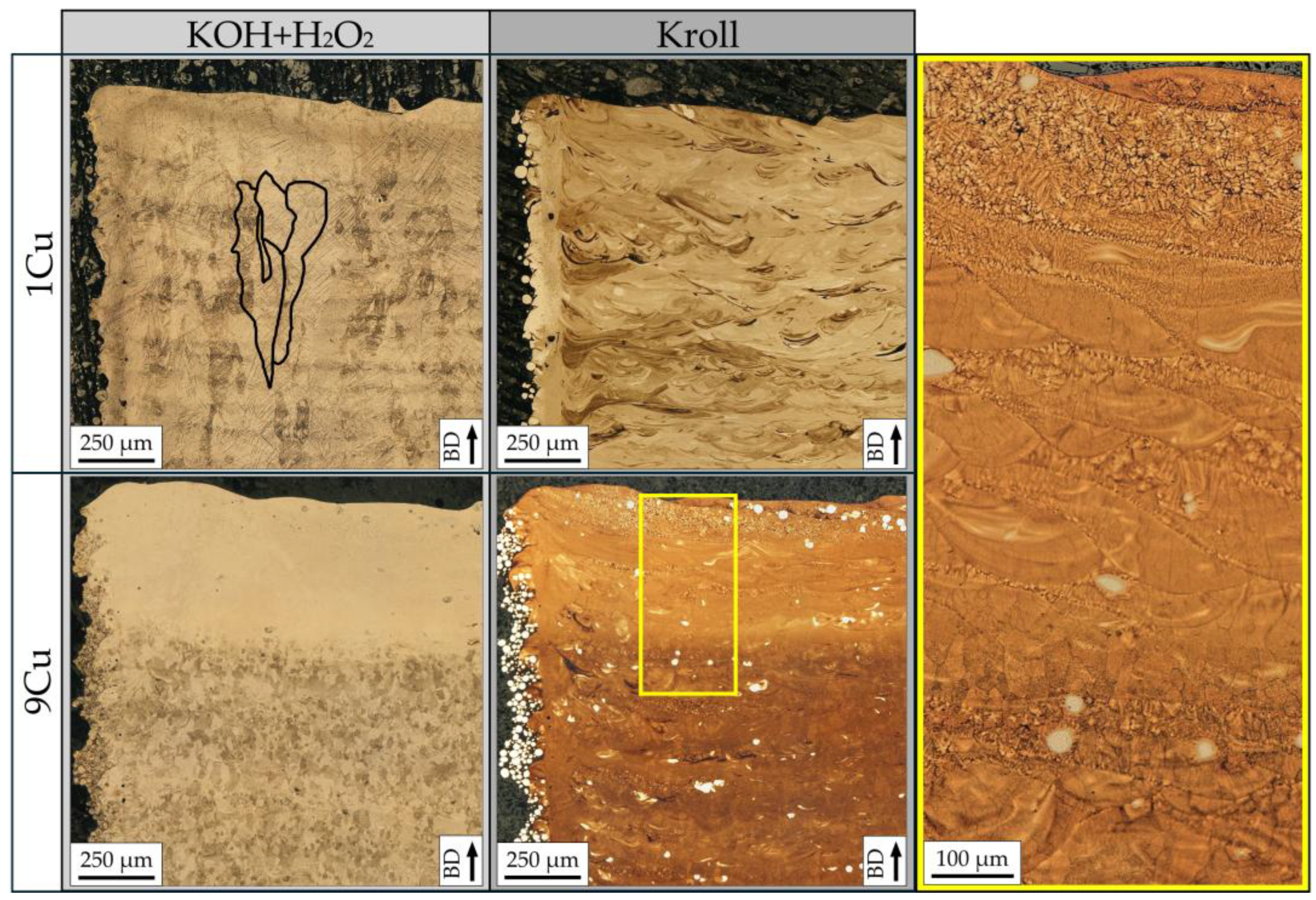

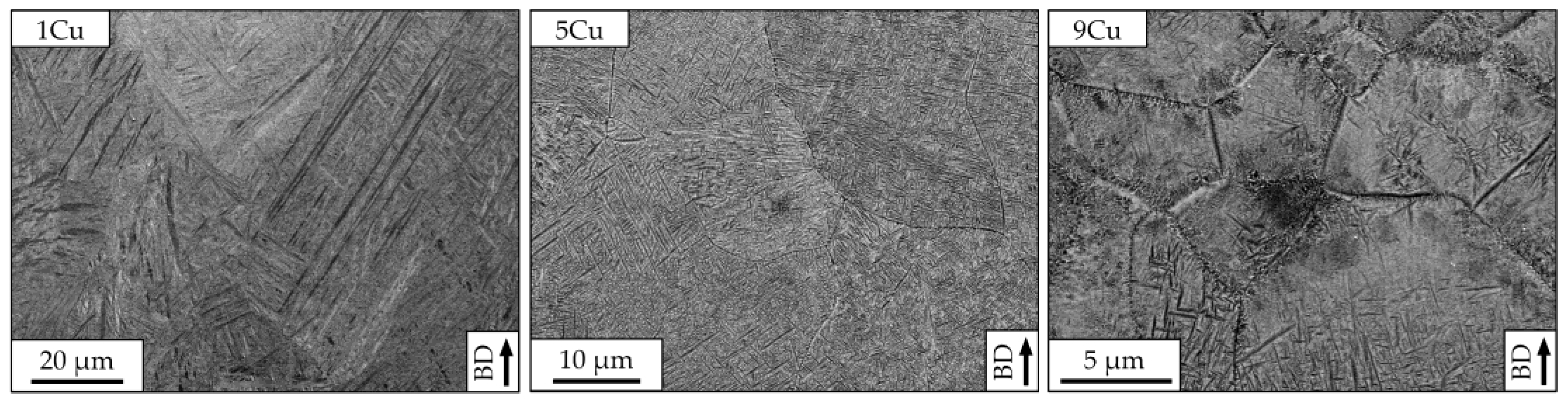

3.2. Characterisation of the As-Built Microstructures

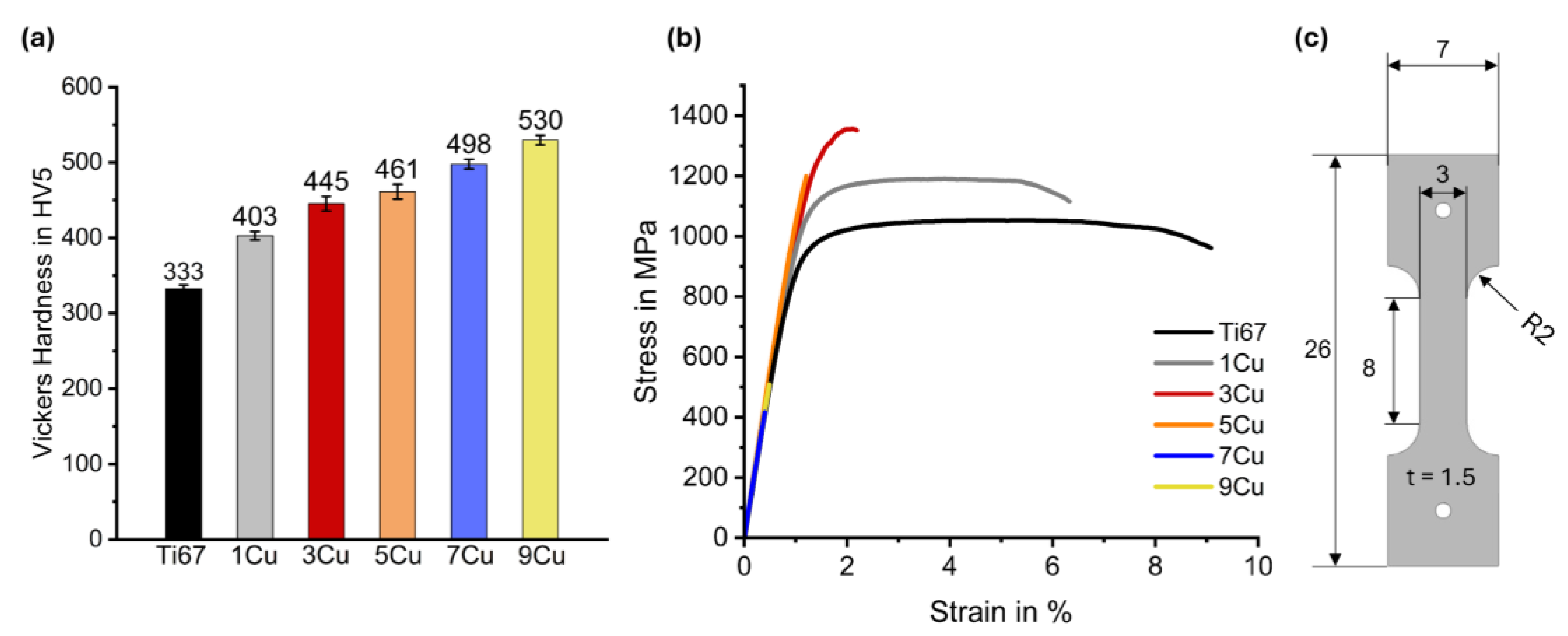

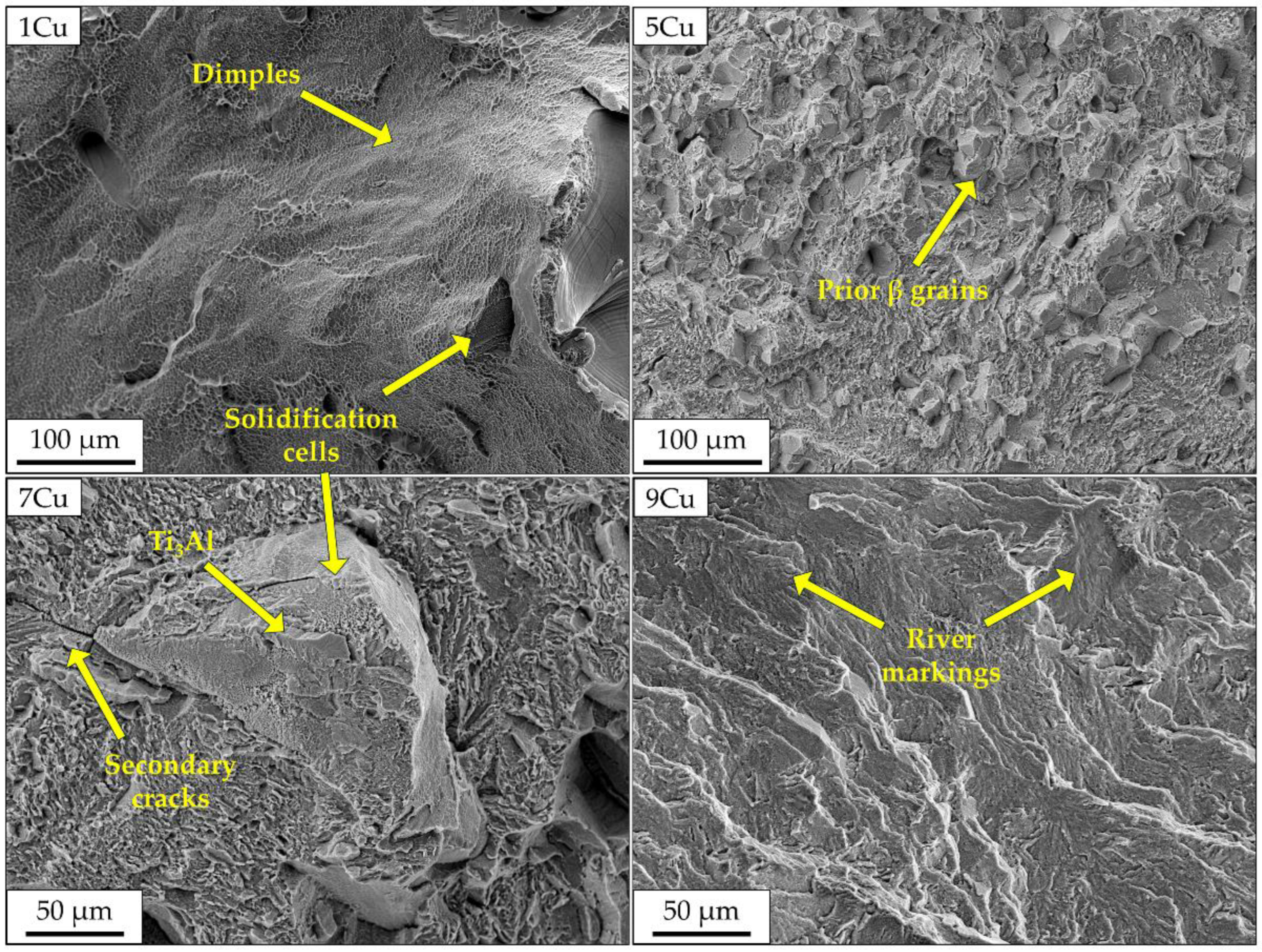

3.2. Mechanical Properties

4. Discussion

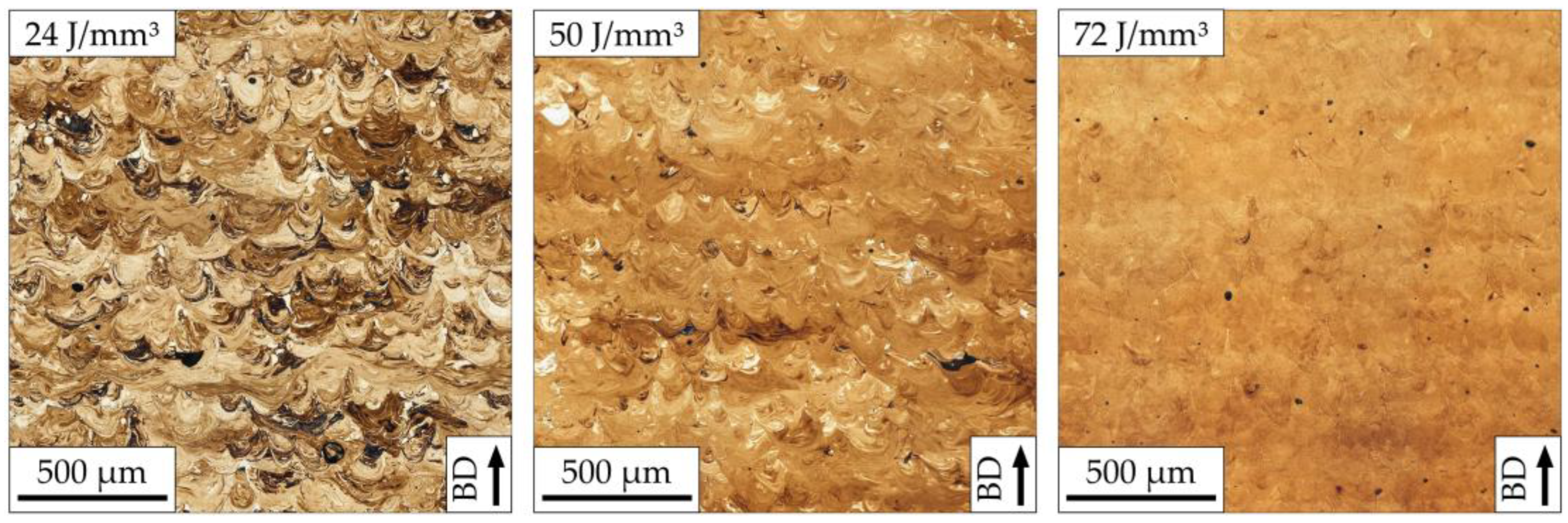

4.1. Parameter Studies and Processability

4.2. Phase Evolution and Morphology

4.3. Mechanical Properties

5. Conclusions

- High-density samples (> 99.9 %) were achieved for all compositions, but uniform copper distribution strongly depended on processing parameters, particularly energy density.

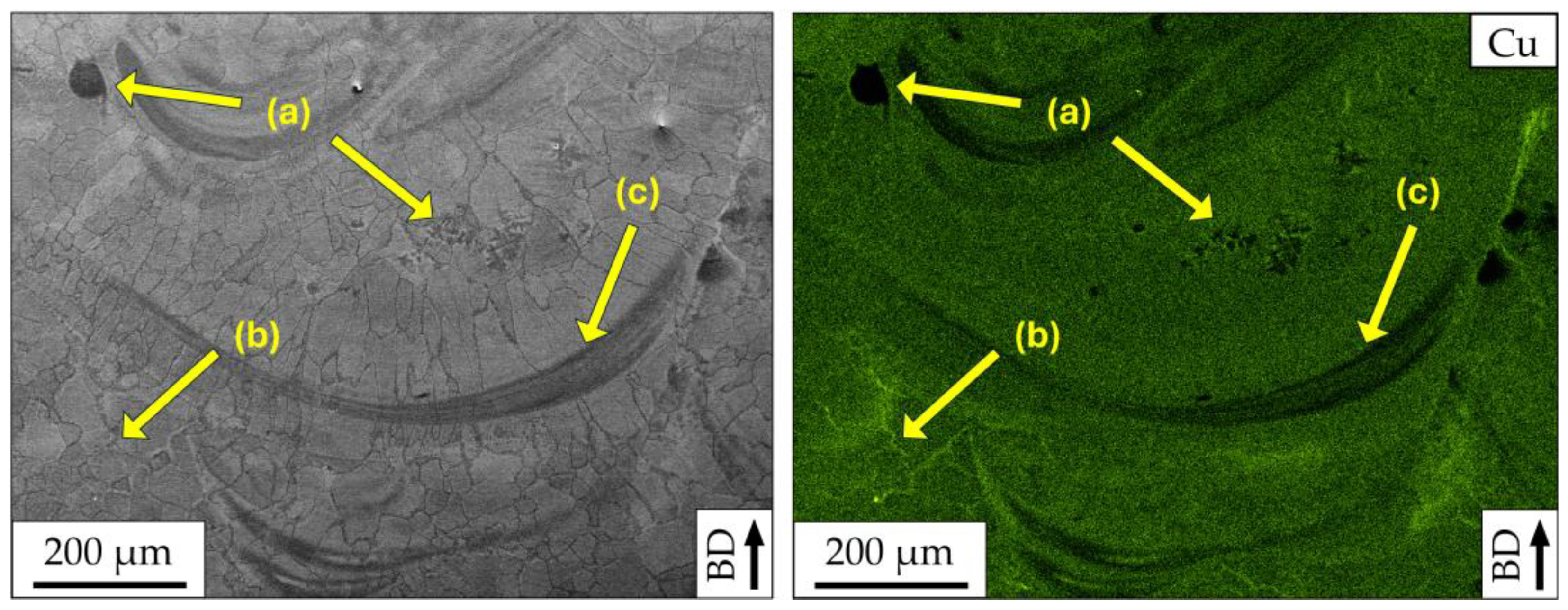

- Increasing copper content led to significant grain refinement and a columnar-to-equiaxed transition; however, inhomogeneities and copper segregation were observed at ≥ 5 wt.% Cu.

- XRD and SEM analyses revealed that copper additions promoted stabilisation of metastable β and precipitation of Ti₂Cu, with their fractions increasing with copper content.

- Hardness and yield strength increased nearly linearly with copper content due to solid solution strengthening, grain refinement, and precipitation hardening.

- Ductility decreased sharply beyond 5 wt.% Cu because brittle fracture mechanisms, hot cracking, and Ti₂Cu/Ti₃Al formation became dominant.

- Overall, moderate copper additions (≈ 1 wt.% – 3 wt.%) appear most promising, balancing mechanical performance and processability, while higher Cu levels lead to significant embrittlement and process-related defects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kobayashi, E., Wang, T., Doi, H. et al. Mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of Ti–6Al–7Nb alloy dental castings. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 9, 567–574 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Mochizuki, H.; Doi, H.; Yoneyama, T.; Hanawa, T. Fatigue Life Prediction of Biomedical Titanium Alloys under Tensile/Torsional Stress. Mater. Trans. 2006, 47, 1826–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, F.; Siemers, C.; Klinge, L.; Lu, C.; Lang, P.; Lederer, S.; König, T.; Rösler, J. Aluminum- and Vanadium-free Titanium Alloys for Medical Applications. MATEC Web Conf. 2020, 321, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.T., Eo, M.Y., Nguyen, T.T.H. et al. General review of titanium toxicity. Int J Implant Dent 5, 10 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Lemus, M.; López-Valdez, N.; Bizarro-Nevares, P.; González-Villalva, A.; Ustarroz-Cano, M.; Zepeda-Rodríguez, A.; Pasos-Nájera, F.; García-Peláez, I.; Rivera-Fernández, N.; Fortoul, T.I. Toxic Effects of Inhaled Vanadium Attached to Particulate Matter: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Thouas, G.A. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2015, 87, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Q., Lu, X. A Biomedical Ti-35Nb-5Ta-7Zr Alloy Fabricated by Powder Metallurgy. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 28, 5616–5624 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Iijima, D.; Yoneyama, T.; Doi, H.; Hamanaka, H.; Kurosaki, N. Wear properties of Ti and Ti-6Al-7Nb castings for dental prostheses. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 1519–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Lu, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, L.; He, M.; Zhao, C.; Gan, Y.; Lin, J.; Luo, J.; Xu, X.; Lin, J. Preliminary study on the corrosion resistance, antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of selective-laser-melted Ti6Al4V-xCu alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 72, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L.; Arciola, C.R. The significance of infection related to orthopedic devices and issues of antibiotic resistance. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2331–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xu, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Cai, H. Metallic Biomaterials: New Directions and Technologies; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, F.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Ren, B.; Yang, K.; Zhang, E. Effect of Cu content on the antibacterial activity of titanium–copper sintered alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 35, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Li, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Yang, K. A new antibacterial titanium–copper sintered alloy: preparation and antibacterial property. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 4280–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yao, M.; Liu, R.; Yang, K.; Ren, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Z.; Liu, W.; Qi, M. Study on antibacterial activity and cytocompatibility of Ti–6Al–4V–5Cu alloy. Mater. Technol. 2015, 30, B80–B85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., Memarzadeh, K., Chang, B. et al. Antibacterial effect of copper-bearing titanium alloy (Ti-Cu) against Streptococcus mutans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep 6, 29985 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Park, E.-J.; Song, H.-J.; Anusavice, K.J.; Park, Y.-J. Cytotoxicity of alloying elements and experimental titanium alloys by WST-1 and agar overlay tests. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Dong, H.; Liu, J.; Qin, G.; Chen, D.; Zhang, E. In vivo antibacterial property of Ti-Cu sintered alloy implant. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 100, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, L.; Janson, O.; Engqvist, H.; Norgren, S.; Öhman-Mägi, C. Antibacterial investigation of titanium-copper alloys using luminescent Staphylococcus epidermidis in a direct contact test. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 97, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, Y.; Yang, F.; Bolzoni, L. Low-cost powder metallurgy Ti-Cu alloys as a potential antibacterial material. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 95, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, S.; He, M.; Luo, K.; Lin, J. Copper-modified Ti6Al4V alloy fabricated by selective laser melting with pro-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties for potential guided bone regeneration applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 90, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakhmalev, P.; Yadroitsev, I.; Yadroitsava, I.; de Smidt, O. Functionalization of biomedical Ti6Al4V via in situ alloying by Cu during laser powder bed fusion manufacturing. Materials 2017, 10, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.C., Taggart, R. & Polonis, D.H. The morphology and substructure of Ti-Cu martensite. Metall Trans 1, 2265–2270 (1970). [CrossRef]

- Donthula, H.; Vishwanadh, B.; Alam, T.; Borkar, T.; Contieri, R.J.; Caram, R.; Banerjee, R.; Tewari, R.; Dey, G.K.; Banerjee, S. Morphological evolution of transformation products and eutectoid transformation(s) in a hyper-eutectoid Ti-12 at% Cu alloy. Acta Mater. 2019, 168, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobromyslov, A.; Kazantseva, N. Phase transformations in the Ti-Cu system. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2000, 89, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Dobromyslov, A.V. Bainitic Transformations in Titanium Alloys. Phys. Metals Metallogr. 122, 237–265 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Sato, K.; Togawa, G.; Takada, Y. Mechanical Properties of Ti-Nb-Cu Alloys for Dental Machining Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, W.; Xin, H.; Yu, F. Microstructure, corrosion and anti-bacterial investigation of novel Ti-xNb-yCu alloy for biomedical implant application. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 5212–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Peng, Q.; Huang, Q.; Niinomi, M.; Ishimoto, T.; Nakano, T. Development and characterizations of low-modulus Ti–Nb–Cu alloys with enhanced antibacterial activities. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Merklein, M.; Bourell, D.; Dimitrov, D.; Hausotte, T.; Wegener, K.; Overmeyer, L.; Vollertsen, F.; Levy, G.N. Laser based additive manufacturing in industry and academia. CIRP Ann. 2017, 66, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Rohani Shirvan, A.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. Additive manufacturing of metallic and polymeric load-bearing biomaterials using laser powder bed fusion: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 94, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, M.L.; Furlani, M.; Giuliani, A.; Bloise, N.; Fassina, L.; Visai, L.; Mengucci, P. Biomechanical performances of PCL/HA micro- and macro-porous lattice scaffolds fabricated via laser powder bed fusion for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 128, 112300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, W.; Attallah, M.M.; Loretto, M.H. Microstructure and strength of selectively laser melted AlSi10Mg. Acta Mater. 2016, 117, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.P.; LaLonde, A.D.; Ma, J. Processing parameters in laser powder bed fusion metal additive manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2020, 193, 108762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Kumar, S.; Dawari, A.; Kirwai, S.; Patil, A.; Singh, R. Effect of temperature and cooling rates on the α+β morphology of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 14, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shin, Y.C. Additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V alloy: A review. Mater. Des. 2019, 164, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, Y.; Tan, X.P.; Wang, P.; Nai, M.; Loh, N.H.; Liu, E.; Tor, S.B. Anisotropy and heterogeneity of microstructure and mechanical properties in metal additive manufacturing: A critical review. Mater. Des. 2018, 139, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, A.; Huynh, T.; Zhou, L.; Hyer, H.; Mehta, A.; Imholte, D.D.; Woolstenhulme, N.E.; Wachs, D.M.; Sohn, Y. Mechanical Behavior Assessment of Ti-6Al-4V ELI Alloy Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2021, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebus, E.; Kuźnicka, B.; Kurzynowski, T.; Dybała, B. Microstructure and mechanical behaviour of Ti–6Al–7Nb alloy produced by selective laser melting. Mater. Charact. 2011, 62, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, M.; Hoyer, K.-P.; Schaper, M. Additively processed TiAl6Nb7 alloy for biomedical applications. Mater. Werkst. 2021, 52, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaege, D.; Eschemann, N.; Hoyer, K.-P.; Schaper, M. Anisotropic Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of a Ti-6Al-7Nb Alloy for Biomedical Applications Manufactured via Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Crystals 2024, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargalis, L.; Ye, J.; Strantza, M.; Rubenchik, A.; Murray, J.W.; Clare, A.T.; Ashcroft, I.A.; Hague, R.; Matthews, M.J. Determining processing behaviour of pure Cu in laser powder bed fusion using direct micro-calorimetry. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 294, 117130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Qiu, D., Gibson, M.A. et al. Additive manufacturing of ultrafine-grained high-strength titanium alloys. Nature 576, 91–95 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Fan, J.; Wang, C. Formation of typical Cu–Ti intermetallic phases via a liquid-solid reaction approach. Intermetallics 2019, 113, 106577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarpour, M.R.; Alikhani Hesari, F. Synthesis of copper nanoparticles by electrochemical reduction: The effect of the preparation conditions on the particle size. Mater. Res. Express 2016, 3, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hatch Distance in µm | Scanning Speed in m/s | Laser Power in W | Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 1.5 | 275 | Ti-6Al-7Nb |

| 1Cu | |||

| 3Cu | |||

| 80 | 1.25 | 350 | 5Cu |

| 7Cu | |||

| 9Cu |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).