1. Introduction

The global shortage of adequate housing has become one of the most urgent humanitarian and environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. According to UN-Habitat, more than one billion people currently reside in informal settlements, a number expected to double by 2030 as rapid urbanization continues across the Global South. As these environments expand, they manifest both the structural inequities that limit access to formal housing and the remarkable adaptive capacities through which communities negotiate constraints. Although informal settlements often arise from economic precarity, infrastructural deficits, and regulatory exclusion, they also exhibit sophisticated spatial configurations, embedded cultural logics, and forms of collective organization. Scholars such as Dovey et al. [

1] and Atkinson [

2] argue that informal urbanism should therefore be understood not merely as a failure of planning but as an emergent spatial process shaped by everyday practices, negotiation, and incremental growth. These dynamics signal an urgent need for pedagogical frameworks that prepare future designers to engage with complexity, uncertainty, and the lived realities of marginalized urban environments.

Traditional architectural education has long emphasized individual authorship, formal experimentation, and the production of visually compelling outcomes. While such approaches contribute important design skills, they often underrepresent the socioeconomic, cultural, and political forces that shape built environments, particularly in underserved contexts. Engaging meaningfully with informal settlements instead requires models of design reasoning that integrate analytic rigor, cultural understanding, and participatory engagement. This shift demands tools that help students recognize how spatial patterns emerge, how communities adapt building typologies over time, and how local knowledge systems influence both form and use. Contemporary scholarship [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] increasingly highlights the potential of computational design to support this work by advancing relational thinking, rule-based reasoning, and iterative decision-making. When framed as an epistemic instrument rather than a representational technique, computation becomes a powerful method for understanding socio-spatial processes.

The design studio examined in this article, ARC 4025 Architectural Design V at the O’More College of Architecture and Design, Belmont University, integrates computational reasoning with service-learning principles to explore informal settlement planning. The pedagogical framework is built upon four interrelated components: (1) pattern language, (2) shape grammars, (3) parametric logic, and (4) service learning. Pattern language [

10] provides an entry point for identifying recurring spatial and behavioral structures that underlie community life. Shape grammars, rooted in the foundational work of Stiny [

11] and expanded by other scholars [

12,

13], offer a formalized method for translating these patterns into generative rules. Coupled with parametric modeling, these rules allow students to construct adaptive systems capable of producing multiple design variations from a shared logic. Service learning positions these computational tools within human narratives and ethical considerations, ensuring that algorithmic reasoning remains grounded in lived experience and community agency.

Ahmedabad, India, provides an especially instructive context for this pedagogical experiment. As one of India’s fastest-growing metropolitan regions, the city exhibits extreme socioeconomic contrasts and a diverse range of settlement typologies. Informal settlements such as Ramapir no Tekro demonstrate many of the challenges common to rapidly urbanizing regions—high density, limited infrastructure, constrained open space, and climate vulnerabilities—while also offering a rich morphological vocabulary of dwelling patterns, block structures, and cultural practices. These characteristics make Ahmedabad an ideal setting for teaching how computational methods can reveal, respect, and extend the logics embedded in informal urban fabric. Students are encouraged not to impose formal ideals derived from Western planning paradigms but to observe, interpret, and translate the settlement’s existing spatial intelligence. Within this framework, computation becomes a method of observation, translation, and synthesis.

This pedagogical methodology has evolved over multiple iterations of the studio and builds on earlier research conducted in partnership with Duarte, Beirão, Verniz, and others [

14,

15]. While existing literature has explored computational modeling, informal urbanism, and service-learning practices independently, there remains limited scholarship on frameworks that integrate these domains into a coherent generative workflow. Few studies examine how computational tools such as shape grammars and parametric logic can be embedded within ethically grounded, community-oriented learning environments. This study addresses that gap by demonstrating how a computational–service-learning model enhances students’ ability to analyze and design within informal settlement contexts by linking rule-based generative systems with real social narratives.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant scholarship on computational design pedagogy, informal urbanism, and service-learning frameworks.

Section 3 outlines the six-phase course methodology.

Section 4 presents the Community at Scale case study.

Section 5 discusses the pedagogical implications of integrating computational tools with service learning.

Section 6 concludes with recommendations for future research and applications.

2. Literature Review

The intersection of computational design, informal settlement research, and service-learning pedagogies has expanded significantly over the past two decades. Yet, these domains have rarely been brought into conversation within architectural education in a systematic and mutually reinforcing way. This literature review situates the pedagogical approach presented in this paper within three primary bodies of scholarship: (1) computational and generative design methods, including shape grammars and parametric modeling; (2) research on the morphology, governance, and spatial logics of informal settlements; and (3) service-learning pedagogies related to community engagement, urban inequality, and socially responsive architectural education. Together, these strands highlight an evolving disciplinary discourse that recognizes computation not simply as a technical skill, but as a cognitive, cultural, and ethical framework through which to understand and intervene in complex social environments.

2.1. Computational Design: From Parametric Logic to Generative Urban Systems

Computational design in architecture has undergone rapid conceptual and methodological expansion. Early foundational work positioned computational systems as generative tools capable of formal exploration, abstraction, and rule-based creativity. Stiny and Gips [

11,

16,

17,

18] introduced shape grammars as a method of producing spatial artifacts through rule-based transformations, establishing a framework for the algorithmic generation of form that has since informed computational design, urban analysis, and architectural pedagogy. Building on this legacy, contemporary scholars have argued for greater clarity in defining the spectrum of computational approaches, including parametric, generative, and algorithmic models, while emphasizing their epistemological implications [

8,

13,

19,

20,

21].

Within architectural education, emerging work explores how these tools support cognitive development, design reasoning, and creative exploration. Zhang, Mo, and Li [

22] highlight the role of web-based computational tools in enhancing studio workflows and collaborative learning, underscoring accessibility and scalability as key benefits for pedagogy. Similarly, Al-Rqaibat, Al-Nusair, and Bataineh [

23] demonstrate that hybrid digital tools—particularly those combining scripting, parametric modeling, and immersive environments—can enhance students’ cognitive flexibility while strengthening their iterative problem-solving skills.

Computational modeling has also broadened to include performance-oriented workflows. Bohm [

24], for example, calls for integrating building performance simulation as a “sense-making” tool that bridges empirical evaluation and conceptual design, suggesting that computation can simultaneously serve analytical and reflective roles. The increasing integration of VR within computational frameworks adds additional layers of spatial understanding and validation, with studies such as Maksoud et al. [

25] showing that VR-based optimization workflows enhance design feedback loops and improve decision-making.

Across these works, a shared theme emerges: computational design should not be reduced to the pursuit of geometric complexity or visual novelty. Rather, it offers structured methodologies for analyzing context, formalizing patterns, and generating responsive design alternatives. This shift—from computation as aesthetic generator to computation as epistemic instrument—forms a critical foundation for applying generative methods to socially complex environments such as informal settlements.

2.2. Shape Grammars and Urban Morphogenesis in Informal Settlements

The use of generative systems to study informal settlements has gained traction as scholars seek methods capable of engaging with the adaptive and self-organizing nature of these environments. Dovey et al. [

1] describes informal settlements as morphogenetic systems—dynamic, decentralized, and governed by incremental spatial decisions rather than top-down planning. This understanding positions informal urbanism as an emergent, resilient, and highly adaptive form of city-making. Such insights necessitate analytical tools that can capture spatial logic without imposing reductive formal typologies.

Shape grammar-based research offers one promising avenue. Dias [

26] applied shape grammar methods to identify and encode spatial patterns in informal settlements, demonstrating the potential of rule-based frameworks to articulate recurring morphological structures. Lima et al. [

27] extend this approach pedagogically through the World Studio model, using shape grammars and parametric methods to help students distill spatial rules embedded within low-income settlements. Their work highlights the pedagogical value of rule-based modeling: students gain computational literacy while simultaneously developing sensitivity to vernacular strategies and socio-spatial resilience.

More recent studies broaden this conversation through comparative and cross-scalar lenses. Wang et al. [

28] examine how shape grammars can analyze vernacular houses in global contexts, focusing on how rule-based systems translate cultural patterns into computational frameworks. Yang [

29] proposes a generative design method that merges shape grammars with Alexander’s pattern language, demonstrating how computational systems can encode qualitative spatial principles alongside quantitative rules. This hybridization—between rule-based logic and culturally embedded spatial knowledge—may be particularly useful in urban settings shaped by informal, incremental, and community-driven practices.

Research at the urban scale has also highlighted the complex relationship between informality, everyday practices, and governance. Atkinson [

2] reframes informal settlements through the lens of public administration, calling for governance models that recognize the legitimacy and agency of informal spatial practices rather than treating them as failures of planning. Together, this body of scholarship portrays informal settlements as places of creative adaptation, socio-spatial intelligence, and iterative design—qualities that align naturally with generative and computational approaches. However, the application of computation to these contexts remains pedagogically underexplored, particularly when combined with structured frameworks for community engagement.

2.3. Service Learning, Community Engagement, and Architectural Pedagogy

[

30] Service learning has become increasingly central to architectural education as programs respond to global calls for socially responsible and community-engaged design practices. Recent scholarship emphasizes that service-learning frameworks deepen students’ understanding of equity, cultural context, and social impact by positioning design as a collaborative process grounded in community needs. García Cervantes [

30] identifies both the opportunities and the challenges of implementing service-learning experiences within informal settlements, arguing that such work requires intentional pedagogical structuring to avoid extractive or superficial engagement. When properly framed, service learning cultivates empathy, ethical awareness, and critical reflection—attributes essential for working in environments shaped by inequality and contested spatial rights. This emphasis on empathy and well-being aligns with emerging research showing that students develop more socially attuned design reasoning when they engage directly with community narratives and real-world contexts [

31,

32,

33].

Özgür [

34] reinforces this perspective by highlighting the importance of cross-cultural dialogue, participatory methods, and interdisciplinary collaboration in contemporary urban design education. These themes resonate strongly with the studio model presented in this article, which situates design exploration within the socio-spatial realities of a partner community and evolves iteratively across multiple academic years. Additional contributions from recent service-learning scholarship further demonstrate how community-engaged design processes foster student growth in cultural sensitivity, ethical responsibility, and collaborative problem solving—qualities central to this pedagogical approach.

Within the broader field of design education, service-learning frameworks often emphasize reciprocal knowledge exchange, reflective practice, and shared authorship. These principles align closely with contemporary perspectives on computational design, where computation is increasingly understood as a method for inquiry and co-production rather than as a tool for producing formal complexity. Boeva and Noel [

35], for instance, argue for a critical computational stance that interrogates the social, political, and ethical implications of generative methods, suggesting that computational systems can support—not substitute—meaningful engagement with communities and spatial contexts.

Integrating service learning with computational techniques, therefore, offers considerable pedagogical value: computation structures the analysis of spatial patterns and generative rules, while service learning anchors the design process in cultural, ethical, and community-based considerations. Yet, despite this complementarity, relatively few architectural studios bring these approaches together, particularly in informal settlement contexts, where such integration is most urgently needed.

2.4. Synthesis: Toward a Pedagogy of Computational Engagement with Informal Urbanism

Taken together, these bodies of literature establish a clear rationale for the pedagogical model developed in this study. Computational design, whether through shape grammars, parametric modeling, or hybrid generative systems, provides powerful tools for analyzing and synthesizing spatial patterns in informal environments. Research on informal settlements underscores the need for methods that respect their emergent logics, socio-cultural structures, and modes of everyday spatial production. Meanwhile, service-learning scholarship highlights the importance of ethical engagement, reciprocity, and reflective practice when working with real communities and global inequities.

Despite their conceptual alignment, these areas of scholarship rarely intersect in architectural education. The present study addresses this gap by offering a studio model that integrates:

rule-based computational reasoning (shape grammars, parametric modeling)

critical spatial analysis of informal settlement patterns

service-learning principles emphasizing social awareness and reflective engagement

This triangulation positions computation not as a detached act of formal manipulation but as a method for understanding social complexity, amplifying local knowledge, and exploring participatory strategies for urban resilience. In doing so, it contributes to a growing discourse that seeks to reorient computational design toward ethical, context-responsive, and socially engaged forms of practice.

3. Studio Framework, Site Features, and Pedagogical Context

The ARC 4025 Architectural Design V studio at O’More College of Architecture and Design builds directly on the generative urban design framework proposed by Duarte and Beirão [

12] and extends the research–teaching lineage established by Verniz et al. [

14] and Lima and Duarte [

15]. Earlier iterations of this pedagogical model focused primarily on shape grammars, pattern-language extraction, and parametric reasoning. Beginning in 2022, however, the studio evolved in response to Belmont University’s mission-driven context as a liberal arts, faith-based institution. This environment, rooted in service, community uplift, and transformative learning, enabled a strengthened service-learning dimension, attracting students committed not only to computational rigor but also to ethical engagement and social impact. Within this expanded vision, computational design was framed as a method for reasoning about social complexity and supporting human-centered outcomes rather than as a formal or representational technique.

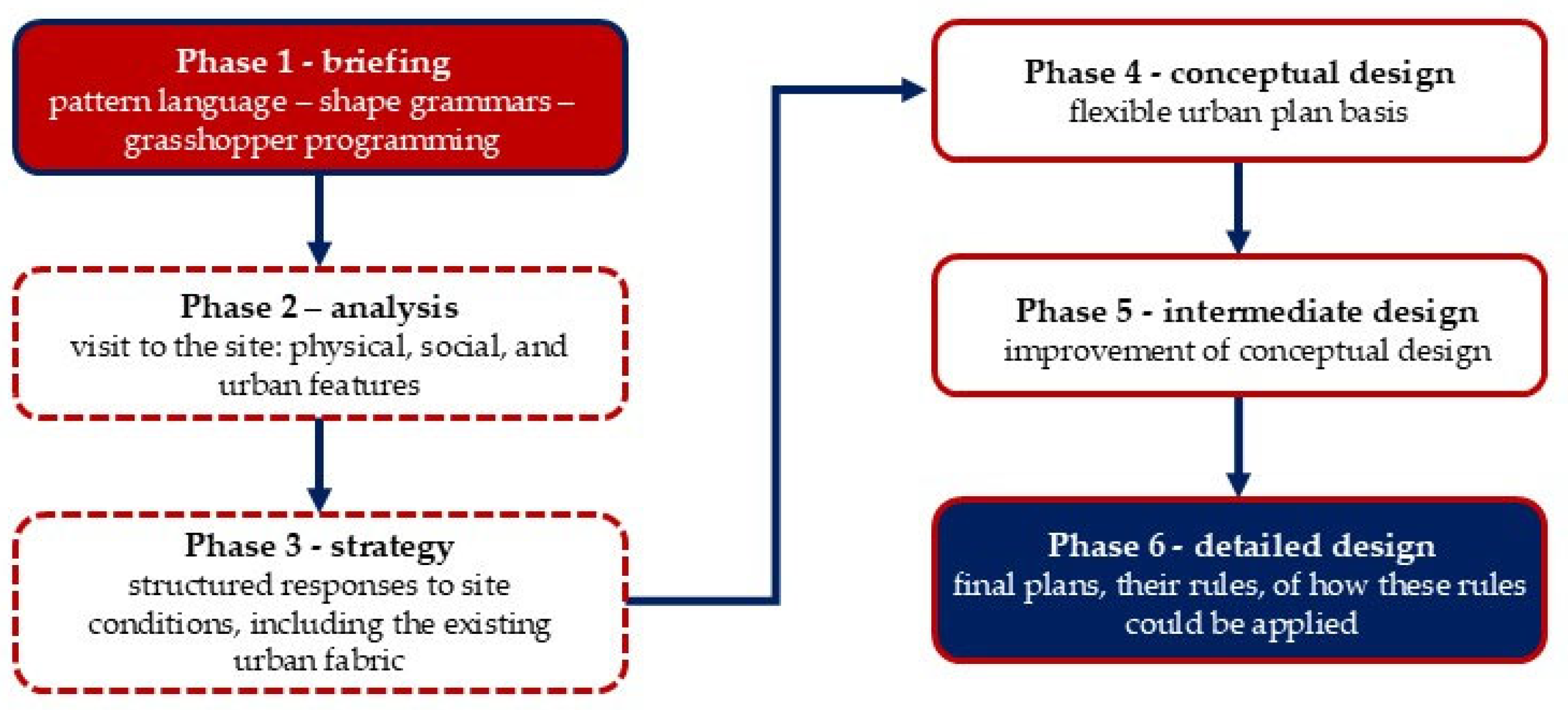

Figure 1.

Six-phase generative and service-learning framework used in the ARC 4025 studio, adapted from Duarte & Beirão and expanded to integrate contextual analysis, community engagement, and computational methods.

Figure 1.

Six-phase generative and service-learning framework used in the ARC 4025 studio, adapted from Duarte & Beirão and expanded to integrate contextual analysis, community engagement, and computational methods.

To structure this work, the semester followed a six-phase workflow adapted from Duarte & Beirão: briefing, analysis, strategy, conceptual design, intermediate design, and detailed design. In the briefing phase, students engaged with discourse on informal urbanism, where authors such as Dovey and Atkinson describe informal settlements as adaptive systems shaped by self-organization, negotiation, and resilience. These perspectives helped students reframe informality as a dynamic socio-spatial condition rather than a deficit-based exception within the city. Through readings and seminar discussions, students began interrogating assumptions about authorship, control, and the nature of “formal” versus “informal” order.

The analysis phase focused on Ramapir no Tekro in Ahmedabad, India—one of the city’s densest and most socioeconomically vulnerable informal settlements. Home to approximately 15,000 residents living within roughly 8,500 dwellings, the settlement displays significant density fluctuations, chronic infrastructural limitations, and an acute scarcity of accessible public space. Seasonal flooding along the central drainage corridor further disrupts mobility, public health, and everyday activities. Despite these challenges, current upgrading interventions deployed in the area rely on a standardized, repetitive housing solution that lacks contextual customization, spatial variation, or sensitivity to existing social dynamics.

In contrast, the students’ proposals began by documenting the settlement’s embedded spatial patterns—such as row-house configurations, courtyard clusters, and mixed-use edge conditions—while also examining the temporal rhythms of daily life. They observed flexible thresholds that shift between retail and domestic functions, the use of improvised shading systems, and the presence of micro-courtyards supporting cooking, gathering, and small-scale commerce. This analysis foregrounded the socio-spatial intelligence already present in the settlement and provided the foundation for the generative design strategies developed in subsequent phases.

Figure 2.

Aerial photograph of Ramapir no Tekro, illustrating density variation, limited public space, and the current high-rise, mass-production governmental solution for the site (Adapted from Google maps).

Figure 2.

Aerial photograph of Ramapir no Tekro, illustrating density variation, limited public space, and the current high-rise, mass-production governmental solution for the site (Adapted from Google maps).

These observations emphasized that informal settlements contain significant spatial intelligence embedded in community practices.

During the strategy phase, these observations were converted into rule-based systems. Using pattern-language techniques and shape grammars, students cataloged dwelling types, adjacency logics, access relationships, and rules for incremental expansion. Shape-grammar reasoning enabled them to formalize everyday spatial behaviors into generative mechanisms capable of producing multiple design outcomes rather than fixed solutions. This shift from designing forms to designing rules introduced a new mode of authorship—one centered on understanding processes rather than imposing predetermined shapes.

Parametric modeling extended this rule-based logic into computational simulations. Students created Grasshopper scripts that modeled variations in dwelling units, cluster organization, block formations, and neighborhood-scale circulation. Adjustable parameters—including lot dimensions, street widths, density targets, and environmental constraints—allowed students to visualize how small rule changes could produce cascading effects across scales. These simulations helped them assess walkability, solar access, ventilation patterns, and the distribution of public spaces across generative iterations.

Throughout the semester, service-learning principles grounded computational experimentation in questions of equity, cultural respect, and community agency. Students were encouraged to reflect critically on how generative rules could empower or marginalize residents. They asked how density shifts might alter privacy, how block restructuring might affect micro-economies, and who stands to gain—or lose—from land reorganization. These reflections highlighted the ethical dimension of computational design and reinforced the importance of aligning algorithms with human well-being.

A defining feature of the 2022–2024 iterations of ARC 4025 was the active engagement with the Ahmedabad community through a sustained partnership with an architectural firm based in the city. This collaboration enabled students to participate in video interviews and virtual dialogues with community members and practitioners, providing invaluable insights into lived experiences, constraints, and aspirations. The partnership culminated in an in-person lecture delivered on Belmont’s campus by the firm’s principal, whose direct knowledge of Ramapir no Tekro helped students more accurately interpret their analytical models and understand the socio-spatial nuances that computational workflows alone cannot reveal. This cross-cultural collaboration deepened the studio’s service-learning dimension and reinforced Belmont’s mission to cultivate designers committed to ethical and community-engaged practice.

The conceptual and intermediate phases brought analytical insight and computational logic together into coherent urban strategies. Students developed neighborhood frameworks that addressed infrastructural deficits, environmental vulnerabilities, and the need for distributed essential services. They explored how block structures could integrate schools, health centers, markets, and communal courtyards within short walking distances. Landscape proposals simultaneously functioned as flood infrastructure and public gathering spaces, supporting climate resilience while enhancing quality of life.

By the detailed design phase, each team had developed a multiscalar generative model with outputs ranging from parametric dwelling families to block typologies, mixed-use corridors, and open-space networks. Representational techniques included grammar diagrams, typological taxonomies, environmental assessments, and renderings. These systems, shaped by computational reasoning and grounded in service-learning values, set the stage for the case study presented in the following section.

4. Case Study: “The Community at Scale” Design

Community at Scale represents a comprehensive application of the ARC 4025 studio’s computational and service-learning methodology, synthesizing pattern-based reasoning, shape grammar rules, and parametric logic into a multiscale urban proposal for an informal settlement in Ahmedabad. Conceived as both an analytical exercise and a generative framework, the project investigates how settlements can emerge from rules rather than prescriptions, an approach that honors the incremental, adaptive nature of informal urbanism. Instead of imposing a static design, Community at Scale proposes a system capable of producing a family of urban outcomes derived from logic, pattern recognition, and the socio-environmental realities of life in Ramapir no Tekro.

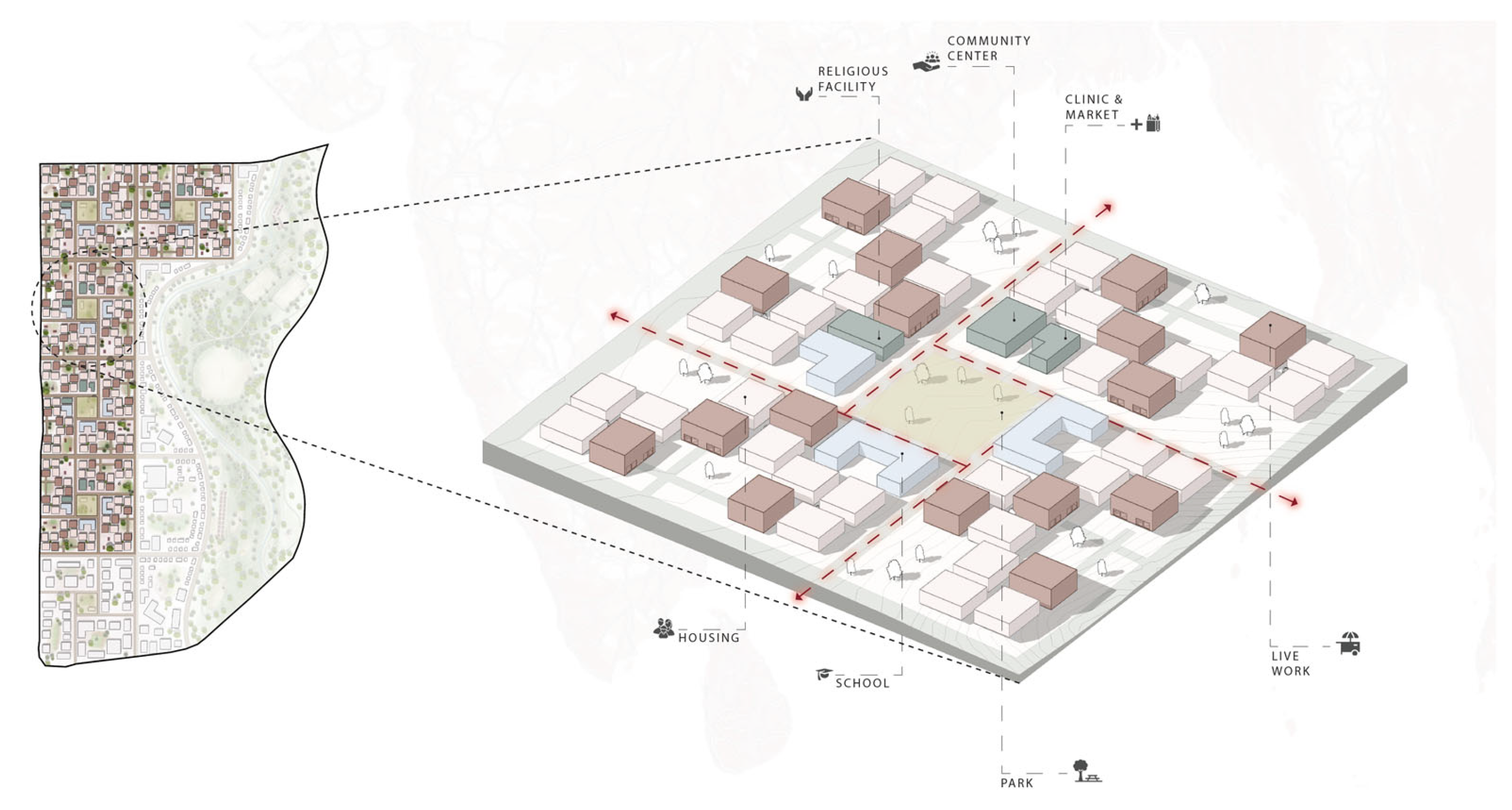

The project begins with the construction of an urban grammar intended to model the settlement’s potential evolution under conditions of improved infrastructure, environmental resilience, and social accessibility. The underlying grammar encodes principles of street hierarchy, density distribution, and land-use clustering, ensuring that spatial growth remains legible and coherent even as it adapts to shifting needs. The resulting masterplan, generated through iterative computational testing, organizes development around a central landscape spine aligned with the site’s existing drainage channel. This corridor acts as a flood-responsive ecological buffer—wide enough to absorb seasonal overflow while doubling as an accessible public park. The masterplan (see

Figure 3) illustrates this dual role, showing a network of housing clusters and civic facilities oriented to maintain proximity to the greenbelt while preserving key pedestrian connections. By situating this corridor at the heart of the proposal, the project aligns form with environmental behavior, transforming a vulnerability into a structuring asset.

From this macro-scale structure, the project moves into the definition of the neighborhood block as the essential unit of urban organization. Each block is conceived as a complete micro-urban system, integrating the daily-life components necessary to support residents without requiring long-distance commutes. Schools, clinics, markets, religious spaces, community centers, live-work edges, and a range of housing clusters are arranged within an 800ft × 800ft footprint. This organization is not arbitrary: the distribution of programs responds to generative rules about walkability, adjacency, and public–private gradients.

The block diagram (see

Figure 4) showcases this logic with clarity. Primary circulation routes are oriented to maintain permeability, leading residents to civic anchors at the block’s core or edges. Shaded internal courtyards serve as semi-public spaces that support small-scale commerce, children’s play, and community gatherings. By concentrating essential services within short walking distances, the block reinforces social cohesion while supporting modes of mobility consistent with informal settlements, where walking is the primary means of transportation. These spatial decisions also reflect community preferences observed during earlier analyses: the desire for immediate access to water, markets, and schooling, as well as safe and shaded routes for daily movement.

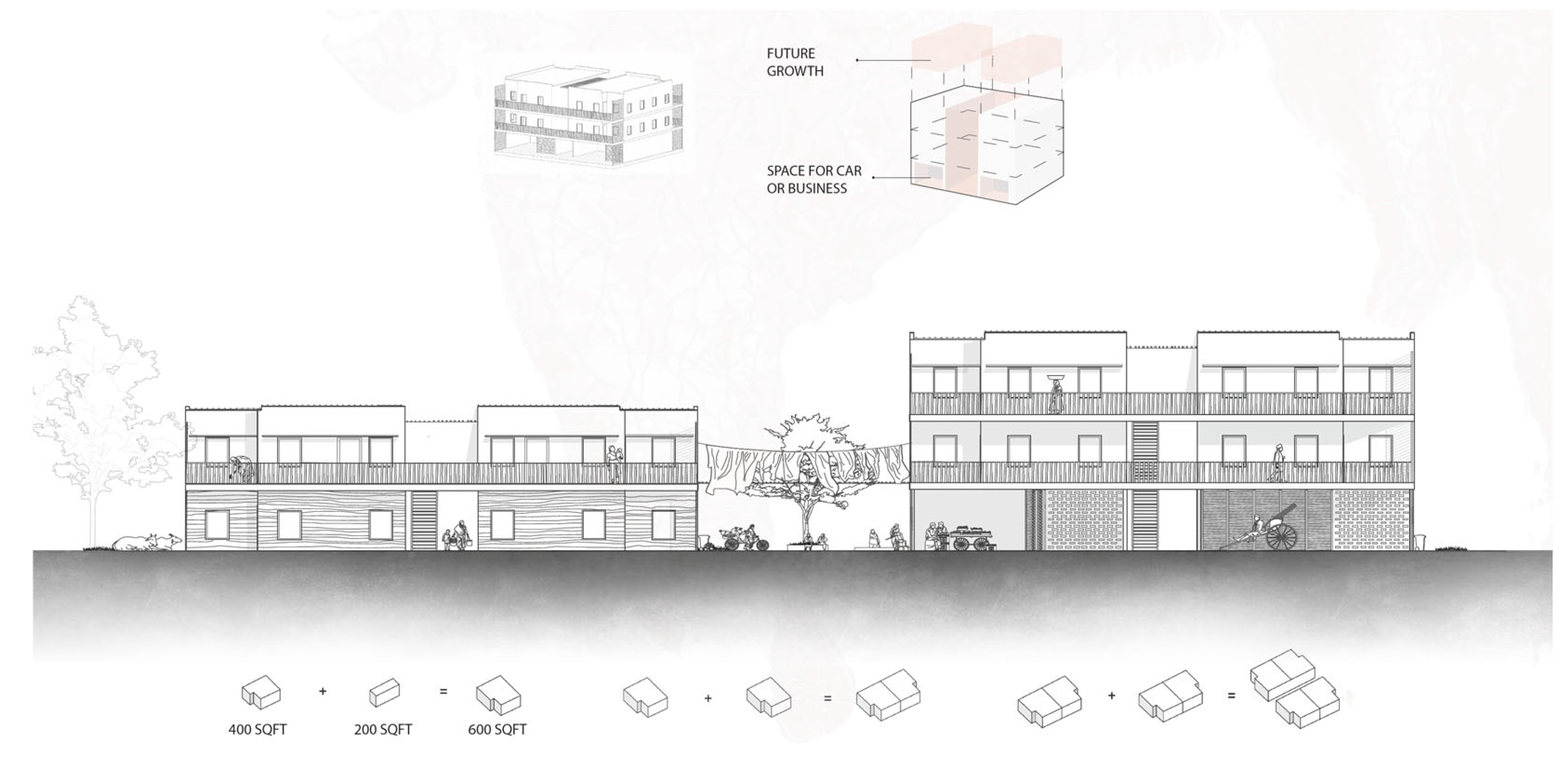

Within these blocks, Community at Scale organizes building groups through a hybrid generative strategy. Shape grammar rules provide the governing structure, while parametric logic allows each building group to adjust to site conditions, family size, or economic function. The building assemblies visible in the elevation study (see

Figure 5) highlight this fusion: units are arranged in staggered clusters that create porosity, shade, and communal thresholds. Ground floors are intentionally flexible, accommodating family businesses, small workshops, or vehicle storage depending on need, reflecting the live-work character of Ahmedabad’s informal neighborhoods. Upper floors are designed to be incrementally expanded, mirroring the vertical growth patterns documented in the site analysis. This capacity for staged construction supports long-term affordability by allowing households to build according to financial readiness.

Architectural elements reinforce cultural specificity and environmental responsiveness. Brick lattice screens filter sunlight and promote ventilation, timber shading devices offer comfort during peak heat, and rammed-earth plinths elevate residents above flood levels. These materials and strategies, while modernized through generative design, remain consistent with vernacular knowledge and local construction practices. The building groups, therefore, function as modular components in a broader system but retain the identity and rhythms of the communities they aim to serve.

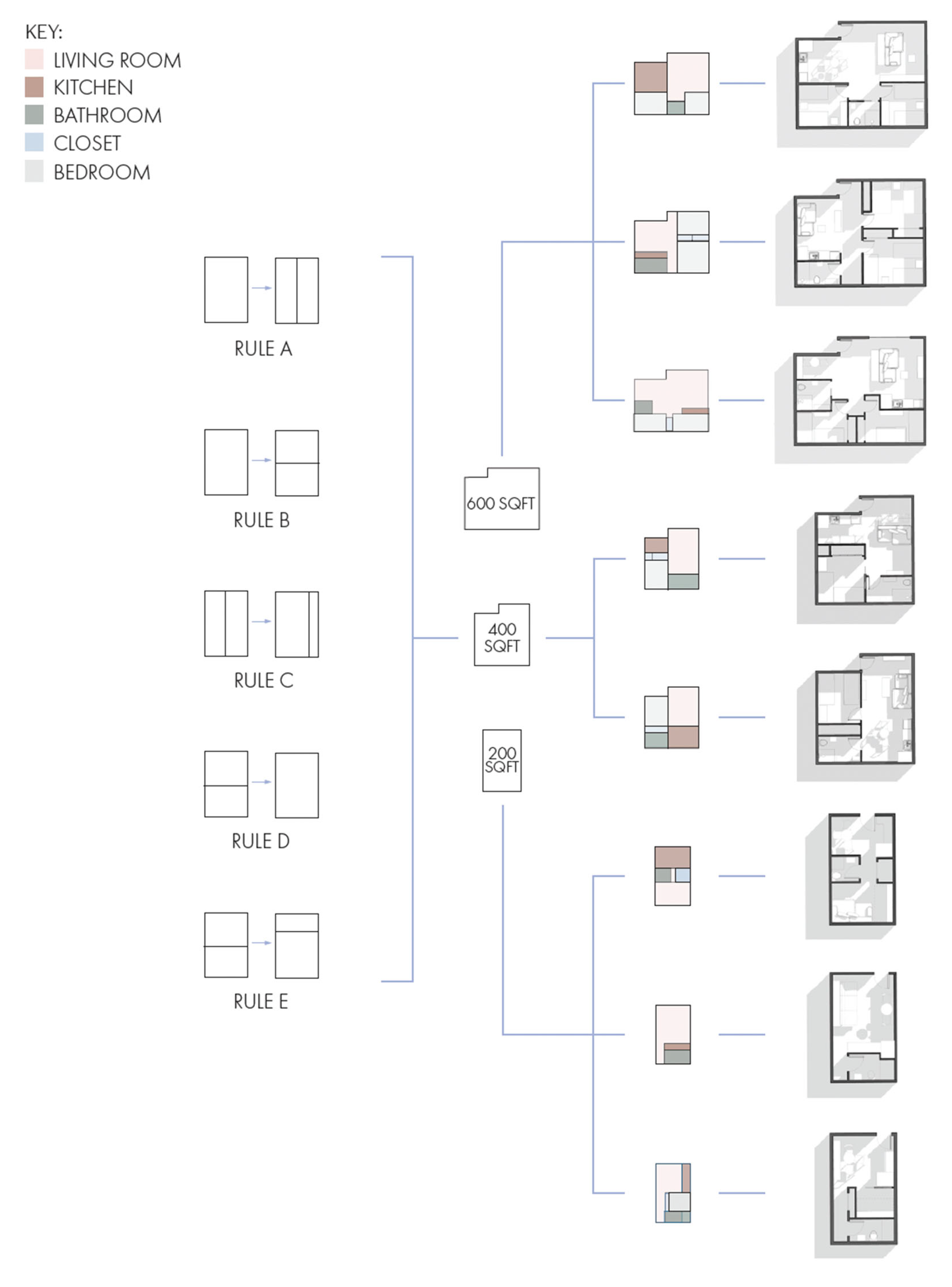

At the micro scale, the project focuses on the dwelling unit as the smallest generative element. Each unit originates from one of three base footprints—200, 400, or 600 square ft, and is transformed through a set of five grammar rules (A–E). These rules define how a dwelling can expand, subdivide, reorient, or combine with other units. Rather than treating housing as a fixed commodity, the project views it as a living system that changes alongside the family. The shape grammar diagram (see

Figure 6) illustrates how these rules produce a variety of floor plans, each maintaining core functional relationships while accommodating diverse needs. Kitchens may shift to improve ventilation; living rooms may expand to allow home-based commerce; service spaces may be consolidated to support shared infrastructure.

By formalizing these variations as rules, Community at Scale ensures that the housing system remains predictable yet flexible. Families can personalize their homes while the neighborhood retains spatial coherence—an essential balance for informal contexts where both individuality and collective order matter.

The experiential qualities of the project are conveyed through a series of renderings that illustrate the lived atmosphere of the proposed spaces. The interior-cluster rendering (

Figure 7) depicts a shaded courtyard framed by housing units, trees, and lightweight canopies. The scene reflects a common feature of informal settlements: semi-public zones where domestic, economic, and social activities blend. Children move freely across open ground; vendors display items near thresholds; families gather in shared seating areas. The rendering highlights how the spatial logic derived from grammar rules creates opportunities for organic social life rather than constraining it.

A mixed-income street view (

Figure 8) demonstrates how incremental architectural variations create a vibrant façade along primary routes. Small shops, balconies lined with laundry, informal seating, and multiple entry points create an active frontage where private life extends into the public realm. This spatial informality is supported, not suppressed, by the generative system. The rendering shows the promise of a socially mixed neighborhood: households of different economic means coexisting in a shared urban environment shaped by flexibility and mutual visibility.

At the civic scale, the town square (

Figure 9) serves as the gravitational center of each neighborhood. It hosts a Warka water tower for fog harvesting, a timber market pavilion, shaded gathering areas, and open surfaces for performances, prayer, or festivals. The rendering captures the layered functionality of this space: environmental infrastructure merges with social infrastructure, creating a hub where essential resources—water, shade, commerce, community—are co-located. The square becomes a symbol of the project’s commitment to design that supports dignity and access.

Finally, the riverside park (

Figure 10) embodies the project’s environmental and recreational aspirations. As a flood-resilient public landscape, it provides sports fields, play structures, shaded gathering areas, and walking paths that connect the community to the water’s edge. More than a buffer, it becomes a shared living room for the settlement, extending social life into the natural environment while mitigating flood risk. The rendering captures its openness, greenery, and potential as a communal anchor.

Altogether, Community at Scale presents a nuanced model for designing with, rather than merely for, informal urban contexts. Its generative system translates observed patterns into rule-based strategies that preserve cultural identity, support economic opportunity, and respond to environmental realities. Through its integration of computational thinking and service-learning values, the project demonstrates how flexible, contextually grounded, and socially attuned neighborhoods can emerge from logic rather than imposition. This case study thus exemplifies the potential of computational design to mediate between empirical observation and visionary urban futures in the Global South.

5. Discussion

The pedagogical model presented in this study demonstrates how computational design, when integrated with service-learning principles, can reshape architectural education by reorienting design inquiry around social complexity rather than formal novelty. The ARC 4025 studio shows that computational workflows such as pattern extraction, shape grammars, and parametric modeling are not merely technical exercises but can serve as bridges between analytical rigor and ethical engagement. This discussion expands on the pedagogical implications of the model, emphasizing three central themes: (1) computation as a mode of relational understanding, (2) generative design as a pathway to contextual intelligence, and (3) service learning as an essential complement that grounds computational reasoning in lived experience.

First, the studio underscores the need to reposition computational design within architectural education as a tool for relational understanding to think about how social, environmental, and spatial systems interact. In many architectural curricula, computational tools are introduced through abstract geometric challenges or formal optimization tasks. While technically useful, such exercises often lack grounding in real-world conditions. By contrast, the ARC 4025 studio situates computational reasoning within the socio-spatial realities of informal settlements such as Ramapir no Tekro. Students must engage not only with geometry and logic but also with the informal economies, cultural traditions, and environmental vulnerabilities that shape daily life in Ahmedabad.

This contextual framing shifts how students perceive computation. Instead of seeing algorithms as mechanisms for producing complexity, they begin to recognize how generative systems can express and support local patterns, incremental development, and community resilience. Shape grammars, for instance, become tools for articulating how dwellings evolve as families grow, how courtyards emerge around shared needs, and how social networks influence spatial arrangement. Parametric modeling helps students visualize the cascading consequences of modifying public–private gradients, circulation hierarchies, and density distributions. In this way, computational tools cultivate a deeper awareness of interdependence, encouraging students to view settlements as living systems shaped by rule-based adaptation rather than formal disorder.

Second, generative design, particularly through hybrid shape-grammar/parametric workflows, offers a powerful methodology for operating within informal settlement contexts characterized by uncertainty, constraint, and incremental growth. A key contribution of the studio is demonstrating that students can move beyond deterministic masterplanning toward contextually intelligent generative systems. These systems do not impose singular solutions; instead, they produce a family of possible outcomes that remain coherent while allowing for variation, personalization, and long-term adaptability. This mirrors the fundamental nature of informal settlements, where buildings and neighborhoods evolve according to emergent needs rather than fixed blueprints.

The Community at Scale case study illustrates this pedagogical shift. Its design logic is rooted in rule-based reasoning: dwellings expand through grammar operations; blocks are organized through adjacency rules; civic spaces emerge from parametric relationships between landscape, flood zones, and public access. Students learn that design in informal contexts must remain open-ended, resilient, and negotiable. In doing so, they gain fluency in computational approaches that match the adaptive intelligence of the communities they study. The ability to model, test, and revise generative rules equips students with tools for engaging uncertain futures—an essential skill in regions experiencing rapid urbanization and climate vulnerability.

Third, the service-learning component enriches computational reasoning by grounding design work in ethical responsibility and cultural humility. Without this grounding, computational tools risk becoming detached abstractions that inadvertently reinforce top-down planning paradigms. The ARC 4025 studio instead positions service learning as a framework for accountability, a way to ensure that computational experiments remain connected to real human narratives. Through interviews, cross-cultural dialogues, and sustained partnership with Ahmedabad-based practitioners, students gain insight into how settlement residents negotiate daily challenges, how informal economies operate, and how environmental pressures intersect with social life. These engagements challenge students to evaluate the moral and social implications of their generative systems.

This integration reveals an important pedagogical synergy: computational design benefits from the ethical reflexivity cultivated by service learning, and service-learning gains analytical depth when paired with computational reasoning. Together, they help students reconcile two modes of practice often treated as separate—technological innovation and community engagement. The studio demonstrates that these modes can mutually reinforce each other when computation is framed as a method for supporting community agency rather than replacing it. Students begin to understand that algorithms carry assumptions about order, hierarchy, and value, and that these assumptions must be made transparent, debated, and aligned with local priorities.

Finally, the iterative evolution of the studio over multiple years highlights the adaptability of the framework itself. Each iteration refines the balance between computational rigor and social engagement, responding to institutional missions, evolving technological literacy, and the deepening relationship with Ahmedabad partners. This evolving pedagogy reflects the very principles it teaches: like informal settlements, the studio grows incrementally, responding to new insights, new needs, and new partnerships. The approach thus models the adaptability required of future architects working in contexts shaped by rapid social and environmental change.

Overall, the discussion demonstrates that combining computational design with service-learning principles produces a pedagogical model that is analytical, ethical, and contextually grounded. It helps students develop a form of design intelligence that can navigate both the rule-based logic of generative systems and the human-centered complexities of informal settlement planning.

6. Conclusions

This study advances a pedagogical framework that integrates computational design and service-learning principles to support architectural education in addressing the urgent challenges of informal settlement planning. By situating computational reasoning within the lived realities of communities such as Ramapir no Tekro, the ARC 4025 studio demonstrates how generative design tools can foster deeper social awareness, critical inquiry, and ethical engagement among students. The findings from the case study and the broader analysis indicate that this integrated model holds promise for cultivating designers capable of operating within the complexities of rapidly urbanizing and underserved contexts.

The conclusions of this work emphasize three overarching contributions. First, the study affirms that computational design—when understood not as an aesthetic pursuit but as a cognitive and analytical framework—can illuminate the underlying structures, patterns, and adaptive strategies embedded in informal settlements. Shape grammars and parametric modeling enable students to decode the logic of incremental construction, spatial clustering, and everyday practice, revealing the intelligence embedded in self-organized environments. This shift in perspective counters deficit-based views of informal urbanism and empowers students to recognize its potential as a source of design knowledge rather than a problem to be corrected. Computational methodologies thus become tools for honoring local practices, supporting community resilience, and informing context-sensitive interventions.

Second, the study demonstrates the pedagogical benefits of moving from form-making to rule-making. Generative design systems allow students to explore a range of possible futures rather than impose singular solutions, aligning with the dynamic conditions of informal settlements where flexibility, negotiation, and incremental change define the urban fabric. By designing rules instead of forms, students develop strategies that accommodate growth, variation, and long-term transformation. This mode of thinking prepares them to address contemporary urban challenges—including climate change, migration pressures, and resource scarcity—that demand adaptive, resilient, and scalable design approaches. The Community at Scale project exemplifies this contribution by showing how multiscalar generative systems can produce urban configurations that are both coherent and adaptable, balancing environmental logic with cultural specificity.

Third, the study highlights the essential role of service learning in grounding computational methods in ethical and cultural responsibility. Engaging with community narratives—through interviews, cross-cultural dialogues, and partnerships with local practitioners—ensures that computational models remain connected to human needs and aspirations. This grounding helps students develop empathy, humility, and reflexivity, encouraging them to consider how their design decisions affect livelihoods, social networks, and local economies. Service learning also fosters an understanding of design as an inherently relational practice: one that requires listening, collaboration, and respect for community agency. When paired with computational design, these principles ensure that technological innovation does not overshadow social commitment but instead becomes a medium for supporting equitable and sustainable outcomes.

Taken together, these contributions illustrate the potential of a computational–service-learning model to advance architectural education in both conceptual and practical terms. The model equips students with a hybrid skill set that bridges technical proficiency and ethical sensitivity, preparing them to operate within interdisciplinary teams, navigate complex urban environments, and collaborate meaningfully with diverse stakeholders. It encourages designers to view computation as a tool for engaging uncertainty, modeling complexity, and amplifying local knowledge rather than as a mechanism for imposing predetermined solutions.

The findings also suggest several directions for future research. One promising avenue involves expanding partnerships with communities and institutions in the Global South to deepen cross-cultural learning and ensure that computational frameworks align with lived realities. Another involves integrating additional forms of simulation—such as VR-mediated walkthroughs, environmental performance modeling, and agent-based simulations—to enrich students’ understanding of spatial experience and urban dynamics. Further inquiry might also examine how generative rules can incorporate social metrics, such as accessibility to essential services, the distribution of public space, or the preservation of cultural practices. Such integration would help bridge the gap between computational logic and social impact, enabling designers to evaluate the ethical dimensions of their generative systems.

Finally, expanding longitudinal assessment of student learning outcomes would strengthen the evidence base for this pedagogical approach. Tracking how students apply rule-based reasoning, community engagement principles, and computational methods in future academic or professional settings could illuminate the lasting influence of this model. As architectural education grapples with global challenges—from housing shortages to climate resilience—the need for pedagogies that cultivate adaptive, ethical, and computationally literate designers will only grow.

In sum, this study contributes to the evolving discourse on computational design, informal settlement planning, and service learning by demonstrating how these domains can be integrated into a cohesive pedagogical model. The ARC 4025 studio provides a replicable and adaptable framework for developing design intelligence that is both technologically sophisticated and socially attuned. By engaging computation not as a detached process but as a way of reasoning through complex human environments, architectural education can help shape practitioners capable of building more equitable, resilient, and participatory urban futures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L., A.A., E.S., and V.W.; methodology, F.L.; design, A.A., E.S., and V.W.; writing—original draft preparation, F.L.; writing—review and editing, F.L., A.A., E.S., and V.W.; visualization, A.A., E.S., and V.W.; supervision, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all students who have participated in this project since 2020 and whose thoughtful engagement and design work have shaped the evolution of this pedagogical model. Deep appreciation is extended to the O’More College of Architecture & Design at Belmont University for its continued institutional support and for providing the academic structure within which this work has been developed. The authors also thank Arpan Johari and the AW Design Team for their invaluable guidance, local expertise, and sustained support in providing critical information about Ahmedabad and Ramapir no Tekro. Their insights greatly enriched the contextual understanding that underpins this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dovey, K.; van Oostrum, M.; Chatterjee, I.; Shafique, T. Towards a Morphogenesis of Informal Settlements. Habitat Int. 2020, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C.L. Informal Settlements: A New Understanding for Governance and Vulnerability Study. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.P. Towards the Mass Customization of Housing: The Grammar of Siza’s Houses at Malagueira. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2005, 32, 347–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.P.; Rocha, J.; Soares, G. Unveiling the Structure of the Marrakech Medina: A Shape Grammar and an Interpreter for Generating Urban Form. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2007, 21, 317–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.P.; Beirão, J.N.; Montenegro, N.; Gil, J. City Induction: A Model for Formulating, Generating, and Evaluating Urban Designs. In Digital Urban Modeling and Simulation; Arisona, S.M., Aschwanden, G., Halatsch, J., Wonka, P., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 73–98. ISBN 978-3-642-29758-8. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano, I.; Santos, L.; Leitão, A. Computational Design in Architecture: Defining Parametric, Generative, and Algorithmic Design. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F. Urban Design Optimization: Generative Approaches towards Urban Fabrics with Improved Transit Accessibility and Walkability - Generative Approaches towards Urban Fabrics with Improved Transit Accessibility and Walkability. In Proceedings of the A. Globa, J. van Ameijde, A. Fingrut, N. Kim, T.T.S. Lo (eds.), PROJECTIONS - Proceedings of the 26th CAADRIA Conference - Volume 2, The Chinese University of Hong Kong and Online, Hong Kong, 29 March - 1 April 2021, pp. 719-728; CUMINCAD, 2021.

- Lima, F.T.; Brown, N.C.; Duarte, J.P. A Grammar-Based Optimization Approach for Designing Urban Fabrics and Locating Amenities for 15-Minute Cities. Buildings 2022, 12, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.T.; Costa, F. The Quest for Proximity: A Systematic Review of Computational Approaches towards 15-Minute Cities. Architecture 2023, 3, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; OUP: USA, 1977; ISBN 978-0-19-501919-3. [Google Scholar]

- Stiny, G. Introduction to Shape and Shape Grammars. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.P.; Beirão, J. Towards a Methodology for Flexible Urban Design: Designing with Urban Patterns and Shape Grammars. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.P. A Discursive Grammar for Customizing Mass Housing: The Case of Siza’s Houses at Malagueira. Autom. Constr. 2005, 14, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verniz, D.; Lima, F.; Duarte, J. Decoding and Recoding Informal Settlements in a Design Studio: An Overview of the World Studio Project. Gest. Tecnol. Proj. 2022, 17, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.; Duarte, J.P. Teaching Shape Grammars and Parametric Urban Design in The Context of Informal Settlements: The World Studio Project. In Emerging Perspectives on Teaching Architecture and Urbanism; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 2024; pp. 173–196; ISBN 1-5275-5260-8.

- Stiny, G.; Gips, J. ‘Shape Grammars and the Generative Specification of Painting and Sculpture.’; January 1 1971; Vol. 71, pp. 1460–1465.

- Stiny, G. Two Exercises in Formal Composition. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1976, 3, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiny, G. Ice-Ray: A Note on the Generation of Chinese Lattice Designs. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirão, J.N.; Duarte, J.P.; Rudi, S. An Urban Grammar for Praia: Towards Generic Shape Grammars for Urban Design. In Proceedings of the Computation: The New Realm of Architectural Design [27th eCAADe Conference Proceedings / ISBN 978-0-9541183-8-9] Istanbul (Turkey) 16-19 September 2009, pp. 575-584; CUMINCAD, 2009. 575–584.

- Beirão, J. CItyMaker. Designing Grammars for Urban Design, TU Delft: Delft, 2012.

- Lima, F.T.; Brown, N.C.; Duarte, J.P. A Grammar-Based Optimization Approach for Walkable Urban Fabrics Considering Pedestrian Accessibility and Infrastructure Cost. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 23998083211048496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mo, Y.; Li, B. Web-Based Computational Design Tools for Architectural Design Studio: Enhancing Pedagogical Framework. Nexus Netw. J. 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rqaibat, S.; Al-Nusair, S.; Bataineh, R. Enhancing Architectural Education through Hybrid Digital Tools: Investigating the Impact on Design Creativity and Cognitive Processes. Smart Learn. Environ. 2025, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, M. Building Performance Simulation for Sensemaking in Architectural Pedagogy. Build. Cities 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksoud, A.; Hussien, A.; Mushtaha, E.; Alawneh, S.I.A.-R. Computational Design and Virtual Reality Tools as an Effective Approach for Designing Optimization, Enhancement, and Validation of Islamic Parametric Elevation. Buildings 2023, 13, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Angela Dias Informal Settlements: A Shape Grammar Approach. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2014, 8. [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.T.; Muthumanickam, N.K.; Miller, M.L.; Duarte, J.P. World Studio: A Pedagogical Experience Using Shape Grammars and Parametric Approaches to Design in the Context of Informal Settlements. In Proceedings of the Blucher Design Proceedings; 2020; Vol. 8, pp. 627–634.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Fan, W. Application of Shape Grammar to Vernacular Houses: A Brief Case Study of Unconventional Villages in the Contemporary Context. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Samaranayake, S.; Dogan, T. An Adaptive Workflow to Generate Street Network and Amenity Allocation for Walkable Neighborhood Design; online, 2020.

- Garcia Cervantes, N.; Hinojosa Hinojosa, K. Opportunities and Challenges for Service-Learning Experiences in Informal Urban Settlements. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2022, 17, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F. Utilizing Service Learning Practices for Creative Design Improvements; IGI Global, 2025; ISBN 979-8-3693-9704-6.

- Lima, F.; Yates, J. Designing for Blue Zone Neighborhoods: Addressing Social Determinants of Health in an Underserved Neighborhood in Nashville, TN. In Utilizing Service Learning Practices for Creative Design Improvements; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2025; pp. 407–438; ISBN 979-8-3693-9704-6.

- Lima, F.; Shankel, E.; Dambrino, K.L.; Bahemuka, O.; McCoy, T.; Harvey, M.; Ryan, B. Fostering Empathy and Innovation in Architectural Education: Exploring Interdisciplinary Service Learning in Disaster Relief Design. In Utilizing Service Learning Practices for Creative Design Improvements; IGI Global Scientific Publishing, 2025; pp. 311–340; ISBN 979-8-3693-9704-6.

- Yavuz Özgür, I.; Çalışkan, O. Urban Design Pedagogies: An International Perspective. URBAN Des. Int. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeva, Y.; Noel, V.A.A. Critical Computational Relations in Design, Architecture and the Built Environment: Editorial. Digit. Creat. 2023, 34, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).