Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

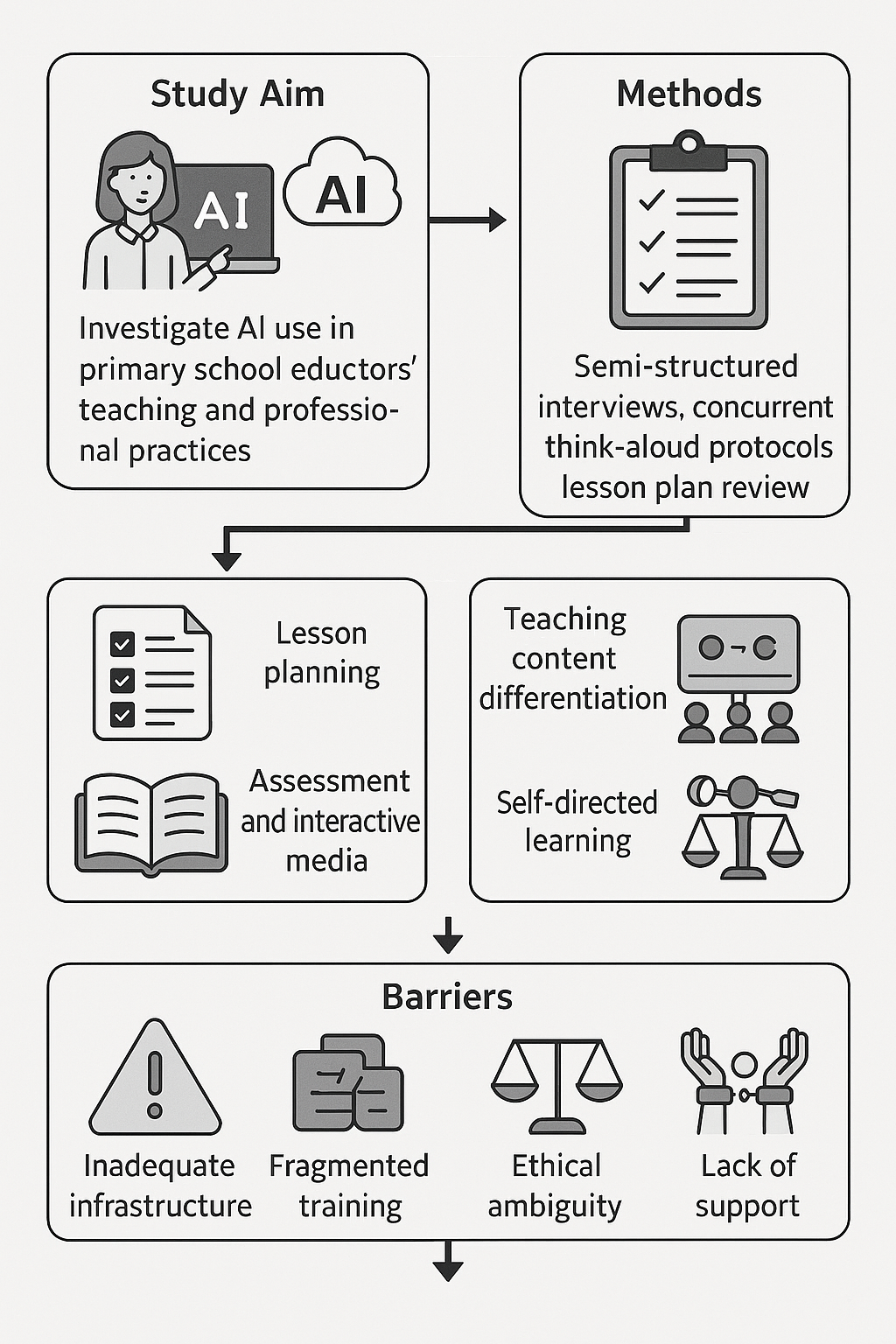

2. Purpose of the Study

3. Methodology

- One pre-use interview to explore their initial perceptions, expectations, and concerns regarding AI tools, and one post-use interview to gather their experiences, reflections, and any challenges encountered.

- Concurrent Think-Aloud sessions during educators utilisation of AI tools for preparation of their lessons, capturing participants’ reflections and decision-making processes.

- One Lesson plan from each educator as tangible evidence of pedagogical application, since participants designed and implemented AI-supported lessons.

Data Analysis

Theoretical Framework Integration

4. Results

4.1. Levels of Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools by Educators

4.2. Use of AI Tools by Educators in Their Professional and Pedagogical Practice

4.2.1. Thematic Unit 1: Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools as Teaching Aids

Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools for Teaching Preparation

Artificial Intelligence as a Tool for Enhancing Student Creativity: Group and Individual Practices

4.2.2. Thematic Unit 2: Use of Artificial Intelligence for Teacher Professional Development

| Subcategory | Examples |

| Exploration, Experimentation, Skill Development | “I’ve tried a bit to ask the AI to simplify some texts. But that’s it—not too much.” (Int1P2) “So, today I’ll try to use ChatGPT to give me ideas for the first day of school after the holiday break.” (TAP2P3) “I feel that I explored some tools specifically designed for school use, like Magic School, Canva, and ChatGPT.” (Int2P9) |

| On-Demand Assistance and Content Generation | “When I started, the first text it gave me was very close to what I had in mind, and I worked on it, revised it, and in the end, I managed to get exactly what I wanted. It saved me a lot of time.” (Int1P24) “I want it to include both open- and closed-ended questions, creative activities, questions that promote critical thinking, and differentiated tasks.” (TAP1P19) “And after I wrote, I asked [ChatGPT] to generate a text so we could compare it with the students’ own. I also asked them to provide the comparison, and for me, that was really helpful.” (Int2P14) |

| Personalized Exploration and Tool Adaptation | “Even though I’m not the kind of person who won’t try something out of fear that something might go wrong… I will try it, but with caution.” (Int1P14) “I’d say it’s interesting. You can even add music. Okay. Add [adds music]. Let’s see, is it here? [searches for music] Oh, it also has a cursor, what does that help us do?” (TAP3P17) “It’s the same for us educators, this is something new for us too. There’s been an explosion of this thing in recent years, and for many of us it’s unfamiliar. We also need some guidance.” (Int2P19) |

| Interactive and Dialogic Practices | “Yes, I believe we need to prepare the students, and they won’t be prepared unless they use these tools and learn to critique them.” (Int1P9) “Let’s say thank you to it as well. [Laughs and reads] You’re welcome. [comments] ChatGPT is polite too. Perfect.” (TAP1P11) “I’ve already suggested several tools to my colleagues, and we said we’d sit down in a meeting to go over them.” (Int2P2) |

| Critical Reflection & Metacognition | “I believe they will be useful once we learn how to use them properly, so that they help us instead of wasting our time.” (Int1P3) “Basically, I didn’t manage to do what I wanted. I’m closing.” (TAP3P5) “So, it’s really important to know what you’re asking it to generate, to give the right prompts, let’s say, so it produces what you actually want. You shouldn’t just accept whatever it gives you as-is.” (Int2P7) |

4.3. Barriers to the Implementation of AI Tools in the Classroom

4.3.1. Thematic Area 1: Lack of Systemic and Organizational Support

Systemic and Organizational Gaps in Support Frameworks

| Thematic Subcategory | Description | Examples |

| Lack of Parent Information and Involvement | Schools and the Ministry provide no communication to parents about AI use. | “The Ministry also needs to have convinced the parents that they should accept these tools.” (Int2P11) |

| Lack of Policy and Official Guidelines | No formal policies, circulars, or resources from the Ministry of Education. | “Right now, the way things are, it all depends on the goodwill of each school and each teacher for these matters to actually work in schools.” (Int2P4) |

| Lack of Structures for Student Digital Competency Development | Limited infrastructure or policy to support students’ digital skill development. | “They still don’t have the skills for me to say, ‘OK, save it to your USB.” (Int2P14) |

| Absence of Incentives or Recognition for AI Adoption | No incentives or recognition for educators integrating AI into their teaching. | “The most important thing, Maria, is that I, as a person, want to do it. If I want to do it, if I say I want to do it, then it’ll work out. If I don’t want to, for whatever reason, I won’t do it. It won’t work. So, it’s motivation. It’s all about motivation.” (Int2P24) |

| Time Constraints and Curriculum Pressure | Rigid timetables leave little room to try new tools. | “And of course, they’ll need to reduce the curriculum load.” (Int2P10) |

| Lack of Account Management Systems and Data Infrastructure | No systems or accounts in place to support access to AI platforms. | “I’d like the accounts to be ready in advance, so that the teacher doesn’t have to set them up.” (Int2P11) |

| Lack of Evaluation or Monitoring of AI Use | No systems to track or assess the impact of AI tools. | “Now, if the inspectors come and request it, and even impose it, let’s say, by asking to see a lesson conducted in the lab, I believe the work will not be done properly. There might be a slight shift, but it will not be substantial.” (Int2P9) |

| Absence of a Legal or Regulatory Framework | Missing legal and ethical guidelines for safe AI use in education. | “[...] how far I can allow students to use artificial intelligence. I mean, for someone who doesn’t want to take risks in life, there’s no legal framework in place either.” (Int2P9) |

| Lack of Curriculum Time for Digital Skills | Digital skills are not included in the official curriculum. | “Should the curriculum change? Should AI be introduced? We’re going to have a lot of work.” (Int2P11) |

| Outdated Teaching Materials | Existing materials fail to reflect current technology use. | “They want, let’s say, within the curriculum or the lessons themselves, to have an accompanying handbook for the teacher.” (Int2P17) |

Insufficient Infrastructure and Restricted Access to AI Tools

| Subcategory | Description | Examples |

| Lack of Technological and Support Structures | Unequal or inadequate technical infrastructure | “If only we had, I don’t know… okay… a device for each student, a screen? Yes, [so they have tablets], or a computer lab.” (Int2P11) |

| Institutional Barriers to Equipment Access | Restrictions due to funding shortages, bureaucracy, or procedural delays | “The computer lab is currently occupied, it’s being used as a classroom.” (Int2P2) |

| Inequities and Lack of Access to Licensed Tools | Limited access to premium tools due to licensing costs or restrictions | “You can’t expect a teacher to move forward and be an educator of tomorrow, and at the same time clip their wings. You need to give them incentives, support them. So just unlock the subscriptions, surely that would cost less overall. A teacher shouldn’t have to pay 20 here and 30 there. Why?” (Int2P15) |

Absence of Institutional Integration of Technologies into Educational Culture and Practice

| Subcategory | Description | Examples |

| Absence of Institutional Integration of Technologies into Educational Culture and Practice | Lack of a structured institutional framework and school-wide culture supporting AI or digital tool adoption | “No [we don’t have a school policy for the use of technology].” (Int2P9) |

| Lack of Interest or Support from School Leadership | Limited engagement, encouragement, or involvement from school leaders in promoting technology-enhanced teaching | “The school administration didn’t get involved with me, neither if I did it, nor if I didn’t.” (Int2P9) |

| Lack of Technological and Support Structures at the School Level | Absence of infrastructure such as computer labs, technical staff, or ICT support in daily school operations | “…that I actually have to go to the principal’s office to get the tablets, charge them, take them home, set them up myself, and make sure no other teacher wants them, which happened, as some didn’t. I also had to prepare the students in advance, because they had never used tablets at school before.” (Int2P2) |

| Lack of Integration of Technologies into School Culture and Practice | Technologies not embedded into regular teaching routines, planning, or school-wide initiatives | “If I had a colleague like you, Maria, who could excite me, who would say ‘you know, we’re going to start this thing, try something new,’ I would dare to do it. But I’m on my own.” (Int2P15) |

| Lack of Available Personal Time for Collaboration, Experimentation, and Professional Development | educators lack designated or flexible time during the workday for co-planning, digital experimentation, or skill-building | “…but I need time to try out the other ones too. They seem really interesting, especially the one that makes videos and... I just don’t have time.” (Int2P14) |

| Lack of Personal Time for Lesson Preparation | educators are time-constrained due to workload and find it difficult to prepare lessons using new digital tools | “[...] if I don’t know a tool, it will take up time, which I don’t have, so I have to take that time from somewhere else in order to use it, to learn it.” (Int2P21) |

| Absence or Inadequacy of Institutionalized Support Roles in Schools | Lack of formal roles such as digital mentors, technology coaches, or coordinators to support implementation | “They should select educators who are actively involved, train them properly, and then send one of them to each school, but they need to actually work, not just sit around for two hours, while someone else who doesn’t even have those hours ends up knowing more than them.” (Int2P10) |

Inadequate Functional, Experiential Training and Support for Educators

| Thematic Subcategory | Examples |

| Lack of systematic and functional training | “I believe that, besides the seminars, they should also train us in a more targeted way, anyway…” (Int2P3) “Well, first of all, the Ministry itself needs to take the initiative and provide training. Because right now, those of us who are using these tools, apart from ChatGPT, which I believe more or less everyone is using, these more…” (Int2P7) |

| Lack of specialized trainers and guidance structures | “There should be someone you can turn to at any time. I think in secondary schools there’s a teacher responsible for the computers who’s always available to help, at least that’s what I hear from my friends. We don’t have that kind of support in primary schools.”(Int2P19) |

| Need for experiential, targeted, and guided training | “The programs the Ministry offered this year on the topic were more like presentations. This presentation style doesn’t really get you to… I believe that if… I don’t know how you came into my path. I think if I hadn’t come across you, I’d still be watching YouTube videos.” (Int2P9) |

| Lack of pedagogical guidance for technology integration | “And in terms of how to use it in the classroom. We definitely need both guidance and some practical strategies.” (Int2P5) |

4.3.2. Thematic Area 2: Ethical and Pedagogical Concerns of Educators

5. Discussion

5.1. Levels of Educators’ Engagement with Artificial Intelligence Tools

5.2. Uses of AI Tools by Educators in Their Professional and Teaching Practice

5.3. Barriers to the Implementation of AI Tools in the Classroom

Educators’ Ethical and Pedagogical Concerns Regarding AI Use

6. Framework for Pedagogical Integration of AI in Primary Education

- Clear policy and governance where The Ministry of Education should develop and communicate clear ethical, legal and curricular guidelines for the use of AI in schools. This policy should include provisions for the protection of students’ data, the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, as well as clear procedures for the selection, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of AI tools. A strong regulatory framework will provide reassurance for educators and ensure that AI tools are used in a safe, responsible and beneficial manner to support learning.

- Equity of access and infrastructure in all schools, as is of paramount importance, for equitable use of AI. Schools need reliable internet connection, sufficient hardware, up-to-date devices, accessible platforms to all students, regardless of socioeconomic background, geographical location, and leadership style.

- Funded resources and support are also necessary. Therefore the Ministry of Education should fund licensed AI tools, for all schools, and protect time in the timetable for educators to experiment, co-plan and explore digital tools. Moreover, the appointment and empowerment of digital coordinators in schools will support day-to-day implementation, alleviate the burden on individual educators, and ensure a coherent approach across classrooms. Furthermore, ongoing professional learning should be continuous, practice-based and situated in real classroom work rather than delivered as one-off workshops. Training training should develop educators’ practical skills, AI literacy, ethical awareness and pedagogical integration through authentic scenarios. Peer mentoring, professional learning communities and structured reflection will help teachers incrementally build their confidence and expertise over time.

- Pedagogically aligned classroom integration is essential, since AI should be integrated in cross-curricular activities, such as writing, visual communication, language development. Educators should be supported to adopt student-centered, constructivist approaches that encourage critical thinking and creativity, and to make this actionable, provide open access lesson templates, adaptable resources and concrete examples of effective classroom use.

- Community trust and engagement are crucial, because successful integration requires trust and collaboration that extends beyond the classroom, therefore the Ministry should engage parents, caregivers and local communities in open dialogue about the role and purpose of AI in education and proactively address ethical and cultural concerns. This will help to build shared understanding and ownership, smooth implementation, and sustain momentum.

7. Limitations of the Study

8. Recommendations for Future Research

Institutional Review Board Statement

References

- Çelik, F., and M. H. Baturay. 2024. Technology and innovation in shaping the future of education. Smart Learning Environments 11, 1: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., P. Chen, and Z. Lin. 2020. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. IEEE Access 8: 75264–75278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, A. 2003. Creativity Across the Primary Curriculum: Framing and Developing Practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly 13, 3: 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovation and Digital Policy Cyprus. 2020. National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence—Deputy Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digital Policy—Gov.cy. Available online: https://www.gov.cy/dmrid/en/documents/national-strategy-for-artificial-intelligence/.

- Digital, Decade. n.d.Cyprus 2025 Digital Decade Country Report Shaping Europe’s digital future. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/factpages/cyprus-2025-digital-decade-country-report.

- Ding, A.-C. E., L. Shi, H. Yang, and I. Choi. 2024. Enhancing teacher AI literacy and integration through different types of cases in teacher professional development. Computers and Education Open 6: 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstad, E. 2024. AI in Education: Rationale, Principles, and Instructional Implications. arXiv arXiv:2412.12116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commision, European. 2023. Digital Education Action Plan (2021-2027)—European Education Area. November 23. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-education/action-plan.

- Feng, L., and S. Xue. 2023. Using the DigCompEdu Framework to Conceptualize Teachers’ Digital Literacy. Education Journal 12, 3: 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyer, N., H. Kempt, and L. Klöser. 2024. Easy-read and large language models: On the ethical dimensions of LLM-based text simplification. Ethics and Information Technology 26, 3: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiadini, A., G. Paganin, and S. Simbula. 2023. Teaching after the pandemic: The role of technostress and organizational support on intentions to adopt remote teaching technologies. Acta Psychologica 236: 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasaymeh, A. M. 2017. Faculty Members’ Concerns about Adopting a Learning Management System (LMS): A Developing Country Perspective. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 13, 11: 7527–7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, A., and J. Edwards. 2024. From Guidelines to Governance: A Study of AI Policies in Education. arXiv arXiv:2403.15601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griva, A. 2024. The effect of using ai in education: An empirical study conducted in Greek private high schools. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11025/57643.

- Guidroz, T., D. Ardila, J. Li, A. Mansour, P. Jhun, N. Gonzalez, X. Ji, M. Sanchez, S. Kakarmath, M. M. Bellaiche, M. Á. Garrido, F. Ahmed, D. Choudhary, J. Hartford, C. Xu, H. J. S. Echeverria, Y. Wang, J. Shaffer, Eric, and Q. Duong. 2025. LLM-based Text Simplification and its Effect on User Comprehension and Cognitive Load. arXiv arXiv:2505.01980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, K. M., Y. Wang, and K. M. McCormick. 2025. Using ChatGPT in the Secondary Gifted Classroom for Personalized Learning and Mentoring. Gifted Child Today 48, 2: 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, J., and P. H. P. Hanel. 2023. Artificial muses: Generative Artificial Intelligence Chatbots Have Risen to Human-Level Creativity. arXiv arXiv:2303.12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. E., and S. M. Hord. 1987. Change in Schools: Facilitating the Process. SUNY Series in Educational Leadership. Publication Sales, SUNY Press, State University of New York-Albany, SUNY Plaza, Albany, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A., and M. Jones. 2019. Leading professional learning with impact. School Leadership & Management 39, 1: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W., M. Bialik, and C. Fadel. 2019. Artificial Intelligence In Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning. Center for Curriculum Redesign: Available online: http://udaeducation.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Artificial-Intelligence-in-Education.-Promise-and-Implications-for-Teaching-and-Learning.pdf.

- Holmes, W., K. Porayska-Pomsta, K. Holstein, E. Sutherland, T. Baker, S. B. Shum, O. C. Santos, M. T. Rodrigo, M. Cukurova, I. I. Bittencourt, and K. R. Koedinger. 2022. Ethics of AI in Education: Towards a Community-Wide Framework. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 32, 3: 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. 2023. Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Student Privacy and Data Protection. Science Insights Education Frontiers 16, 2: 2577–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifenthaler, D., R. Majumdar, P. Gorissen, M. Judge, S. Mishra, J. Raffaghelli, and A. Shimada. 2024. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Implications for Policymakers, Researchers, and Practitioners. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 29, 4: 1693–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, E., C. Alexander, and E. M. Jones. 2024. Exploring the impact of gamification on engagement in a statistics classroom. arXiv arXiv:2402.18313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousiou, C. 2025. Navigating challenges in school digital transformation: Insights from school leaders in the Republic of Cyprus. Educational Media International 62, 1: 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinidou, M., S. Kleanthoys, and J. Otterbacher. 2025. Cypriot teachers’ digital skills and attitudes towards AI. Discover Education 4, 1: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmons, R., C. R. Graham, and R. E. West. 2020. The PICRAT Model for Technology Integration in Teacher Preparation. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education (CITE Journal) 20, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. A. 2014. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT press: Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=jpbeBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=info:cBzPyc88vIgJ:scholar.google.com&ots=Vp7PlU-XMa&sig=lHWEU-Wc4NLcwUb3ODR3urtrwyQ.

- Lu, O. H. T., A. Y. Q. Huang, D. C. L. Tsai, and S. J. H. Yang. 2021. Expert-Authored and Machine-Generated Short-Answer Questions for Assessing Students Learning Performance. Educational Technology & Society 24, 3: 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. E. 2009. Multimedia learning, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. 2024. Aνάρτηση επικαιροποιημένων Aναλυτικών Προγραμμάτων—Gov.cy. August 28. Available online: https://www.gov.cy/paideia-athlitismos-neolaia/anartisi-epikairopoiimenon-analytikon-programmaton/.

- Mogavi, R. H., B. Guo, Y. Zhang, E.-U. Haq, P. Hui, and X. Ma. 2022. When Gamification Spoils Your Learning: A Qualitative Case Study of Gamification Misuse in a Language-Learning App (No. arXiv arXiv:2203.16175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., E. Ingusci, F. Signore, A. Manuti, M. L. Giancaspro, V. Russo, M. Zito, and C. G. Cortese. 2020. Wellbeing Costs of Technology Use during Covid-19 Remote Working: An Investigation Using the Italian Translation of the Technostress Creators Scale. Sustainability 12, 15: 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Action Plan 2021. n.d.Digital Skills – National Action Plan 2021 – 2025—Deputy Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digital Policy—Gov.cy. Retrieved October 7, 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cy/dmrid/en/documents/digital-skills-national-action-plan-2021-2025/.

- Ng, D. T. K., J. K. L. Leung, M. J. Su, I. H. Y. Yim, M. S. Qiao, and S. K. W. Chu. 2022. AI Literacy Education in Early Childhood Education. In AI Literacy in K-16 Classrooms. Edited by D. T. K. Ng, J. K. L. Leung, M. J. Su, I. H. Y. Yim, M. S. Qiao and S. K. W. Chu. Springer International Publishing: pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. N. N., T. T. Tran, N. H. A. Nguyen, H. P. Lam, H. M. S. Nguyen, and N. A. T. Tran. 2025. The Benefits and Challenges of AI Translation Tools in Translation Education at the Tertiary Level: A Systematic Review. International Journal of TESOL & Education 5, 2: 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y., C. Zhang, B. Xu, Y. Zhou, and T. T. Wijaya. 2024. Teachers’ AI-TPACK: Exploring the Relationship between Knowledge Elements. Sustainability 16, 3: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasveran, R. a/l, and N. M. Nasri. 2018. Teachers’ Concerns on the Implementation and Practices of i-THINK with Concern Based Adoption Model (CBAM). Creative Education 9, 14: 2183–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, C., and N. Selwyn. 2020. Deep learning goes to school: Toward a relational understanding of AI in education. Learning, Media and Technology 45, 3: 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, G., V. Marcus, and S. Motamedi. 2025. Student Perspectives on the Benefits and Risks of AI in Education. arXiv arXiv:2505.02198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Cyprus. 2024. Regulatory Administrative Act No. 168/2024. Official Gazette of the Republic. Available online: http://cylaw.org/KDP/2024.html.

- Republic of Cyprus Governance. 2025. Στρατηγική Προώθησης της Τεχνητής Νοημοσύνης στην Κύπρο. Republic of Cyprus Governance: Available online: https://www.diakivernisi.gov.cy/gr/epikairotita/stratigiki-prowthisis-tis-texnitis-noimosynis-stin-kypro.

- Rogers, E. M., A. Singhal, and M. M. Quinlan. 2008. Diffusion of Innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research, 2nd ed. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schophuizen, M., and M. Kalz. 2020. Educational innovation projects in Dutch higher education: Bottom-up contextual coping to deal with organizational challenges. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 17, 1: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N., L. Pangrazio, S. Nemorin, and C. Perrotta. 2020. What might the school of 2030 be like? An exercise in social science fiction. Learning, Media and Technology 45, 1: 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X., G. Cheng, and M. H. Ling. 2025. Artificial intelligence in teaching and teacher professional development: A systematic review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 8: 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, B., M. Farren, and Y. Crotty. 2024. Impacting teaching and learning through collaborative reflective practice. Educational Action Research, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorikari, R., S. Kluzer, and Y. Punie. 2022. DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens - With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. In JRC Publications Repository. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagami, J. 2024. AI Chatbot Influences on Preservice Teachers’ Understanding of Student Diversity and Lesson Differentiation in Online Initial Teacher Education. International Journal on E-Learning 23, 4: 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O., V. I. Marín, M. Bond, and F. Gouverneur. 2019. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education – where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 16, 1: N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, S., Y. Qiao, Q. Hu, Z. Li, J. Gong, and Y. Xu. 2024. Designing Child-Centric AI Learning Environments: Insights from LLM-Enhanced Creative Project-Based Learning. arXiv arXiv:2403.16159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C., S. Wibowo, and L. D. Li. 2024. The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: A systematic review. Smart Learning Environments 11, 1: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Use | Interview 1 (Participants) | Interview 2 (Participants) |

| Non-Use | “I haven’t used them myself so far” (Int1P2) “I’ve heard how you can use it, I just haven’t used it yet.” (Int1PP3) | N/A |

| Exploratory Use | “In general, ChatGPT and I are just getting to know each other.” (Int1P11) “I experimented and I continue to experiment.” (Int1P21) |

N/A |

| Application Oriented Use | N/A | “I’ll definitely be using them [...] during preparation [...]” (Int2P3) “Okay, for lesson preparation, of course it’s useful.[...]” (Int2P17) |

| Potential Integration/Use | N/A | “Yes, I will continue with it. I want to learn more about the tools you recommended, to explore them myself first and find ideas to build on. [...]” (Int1P2) “I’m considering it, yes. I think it’s a necessary evil. [...]” (Int2P4) “I want to continue. If I have the same conditions as this year, I’ll definitely continue.” (Int2P5) |

| Systematic Use | “Okay, we use ChatGPT quite often… also Magic School, Ideogram, and Muse.ai for creating images, DALL·E, and… I’m forgetting the name of another one that’s also for text generation” (Int1P4) “Lately, I’ve started using ChatGPT more intensively.” (Int1P7) “Yes, today we already had our first [lesson using Artificial Intelligence tools] with the little ones [students] […]” (Int1P10) |

“Definitely, it’s done — they’ve now become part of my life. Although it scares me a little, in the sense that I now consider it… especially ChatGPT… I consider it essential. [...]” (Int2P7) “Of course, I use them here for my PhD, academically. Not just for that… let alone for my everyday teaching practice.” (Int2P2) “Yes, absolutely. As a person, as a teacher, and as a mom.” (Int2P24) |

| Subcategory | Description of Use | Indicative Examples |

| Creation and adaptation (differentiation) of teaching material | Simplifying texts, creating differentiated content, and adapting materials to learning levels | “Then I gave them the different texts I had created with the help of ChatGPT, which corresponded to the three learning levels.” (Int2P13) |

| Text simplification for language support | Producing simpler or grade- appropriate texts with targeted vocabulary | “And I can ask the AI to create a text that would fit, let’s say, fifth grade or first or second grade, and that includes a lot of adjectives.” (Int1P4) |

| Creation of worksheets, quizzes, and assessments | Rapid creation of worksheets and questions using AI-based tools | “…I need a worksheet, there’s no reason to waste time. I go to ChatGPT or Magic School, input my text, and immediately get a worksheet.” (Int2P9) |

| Interactive media and gamified activities | Use of game-based platforms (e.g., Quizizz, Kahoot) to promote engagement | “Some game-like questions were used for text comprehension through Kahoot. Not Kahoot, Quizlet.” (Int2P13) |

| Creation of assessments using AI | Using AI to design differentiated or adaptive assessment tools | “This is the third attempt, the third artificial intelligence tool. It’s Quizziz AI. I chose it as a third, different option aimed at creating assessment quizzes.” (TAP3P15) |

| Creation of multimodal and visual material to support teaching | Generation of videos, images, or presentations to enhance understanding and engagement | “I once made a little video for a lesson, and the kids really liked it.” (Int2P19) |

| Support in lesson planning | AI suggested lesson ideas, full plans, and activities tailored to student needs | “…it gives me ideas, and then I build on those ideas, I start building something else, and then a new idea comes to me…” (Int2P7) |

| Subcategory | Examples |

| Group Creation and Reflection | “What I tried with the kids, and it worked, let’s say, was this: how I would say it and how Artificial Intelligence would say it. We essentially compared our own text with the one generated by the AI.” (Int1P4) “We had [Gemini] make predictions, I think, if I remember correctly. We gave it, let’s say, some words to generate predictions about the text, and then we compared them with the students’.” (Int1P7) “We do this with the students, you enter a description, and it gives you an image, quite a specific one. Or for text, you can input a paragraph, I mean a paragraph of text, and it generates images for you.” (Int2P4) “We also made a song about the [March 25th] heroes. Using Suno.” (Int2P10) “…I used [ChatGPT] first in the whole class so they could see that I type to it, describe it, and then, when I click for it to generate the image, before we went down to the lab, and then I would give it corrections, ask it to redo it, and then we went down to the lab.” (Int2P14) |

| Individual Use and Personalized Support | “I said I had used Canva last year to create a poster in Math that the students wanted to make about grouping problems.” (Int1P10) “I also used it based on the children’s descriptions to create something. [...] so a video was created that we shared with the parents and played in class.” (Int1P21) “…a lot with images, because we were doing compositions, and based on the descriptions the students gave, it generated their little image for them to include under their writing in their notebooks.” (Int2P2) “...we did an activity with the younger students about coins, they had to write a description using Magic Media, to write the description.” (Int2P7) |

| Subcategory | Examples |

| Ethical concerns about the protection of personal data and student safety | “Yes, or if we’re going to use photos and things that will be in the classroom again. I think, I’m not sure, are we covered in all aspects?” (Int2P3) “[...] it needs to be used within an environment that is safe for the children. There should be something that is controlled at the school level and appropriate for the age of the students we have.” (Int2P5) |

| Fear of teacher replacement / devaluation of learning | “Doubts, okay, we all generally have doubts about artificial intelligence, about how far it’s going to go, how much we can... it serves us now, but you also think about how much AI can serve us, I mean, more in terms of ethics. And when you have children, you think about that aspect too.”(Int2P4) “[...] what really concerns me about the danger related to Artificial Intelligence is that we might reach a point where we no longer create anything ourselves, and everything will be ready-made, and we’ll start to consider the AI-generated product aesthetically pleasing? That’s something that worries and scares me.” (Int2P9) |

| Concerns about the authenticity of learning and critical thinking | “You need to be careful to check that what it tells you is actually correct, you have to test it first. It shouldn’t be like, I typed it in, it gave me something, and that’s it.” (Int2P7) “As for involving students in this area, okay, that’s where it requires a more careful consideration of your approach, a good understanding of your students’ abilities, what you’ve taught them so far, what their capabilities are. And I need to think carefully about where my role as a teacher ends and where this new kind of work begins.” (Int2P10) |

| Parental reactions and cultural/religious sensitivities | “Also, the Ministry needs to have convinced the parents that they should accept these tools, so that we don’t have to deal with parental backlash.” (Int2P11) “…It’s not just the kids, it’s also the parents. Because as a teacher, you have a lot to deal with if you fall into a trap, let’s say.[...] There are parents who don’t want this happening. Some are very religious, or… There are people who genuinely don’t want their children getting too involved in all this.” (Int2P19) |

| Equity of opportunities between schools | “From the start, it needs to ensure the strengthening of these networks, labs, tablets, there needs to be, in any case, some equality among schools when it comes to this technological matter.” (Int2P2) “The Ministry needs to manage this technological equipment issue... Not all schools have someone who’s involved or knowledgeable about it.” (Int2P4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).