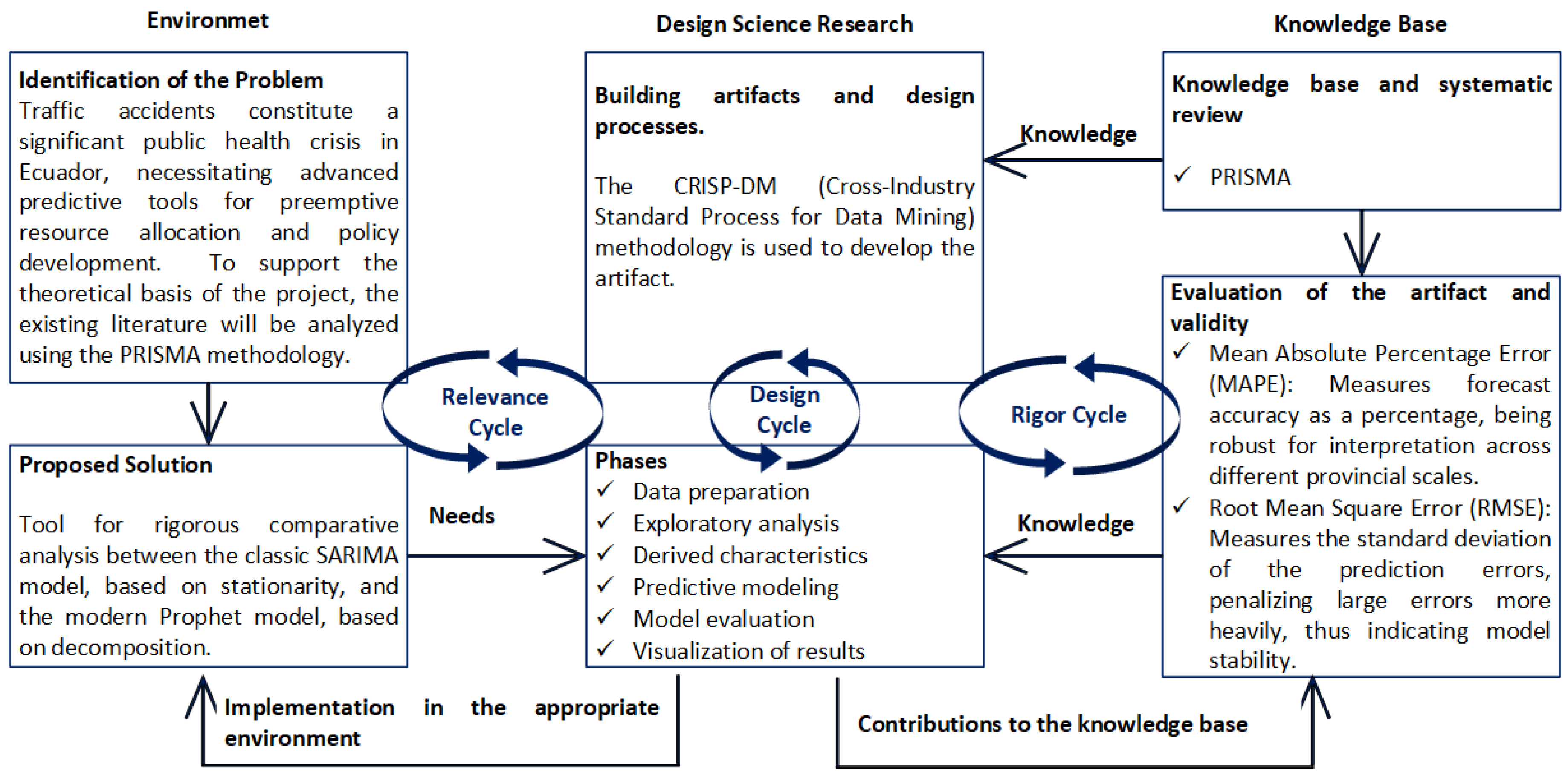

4.1. Coast Region

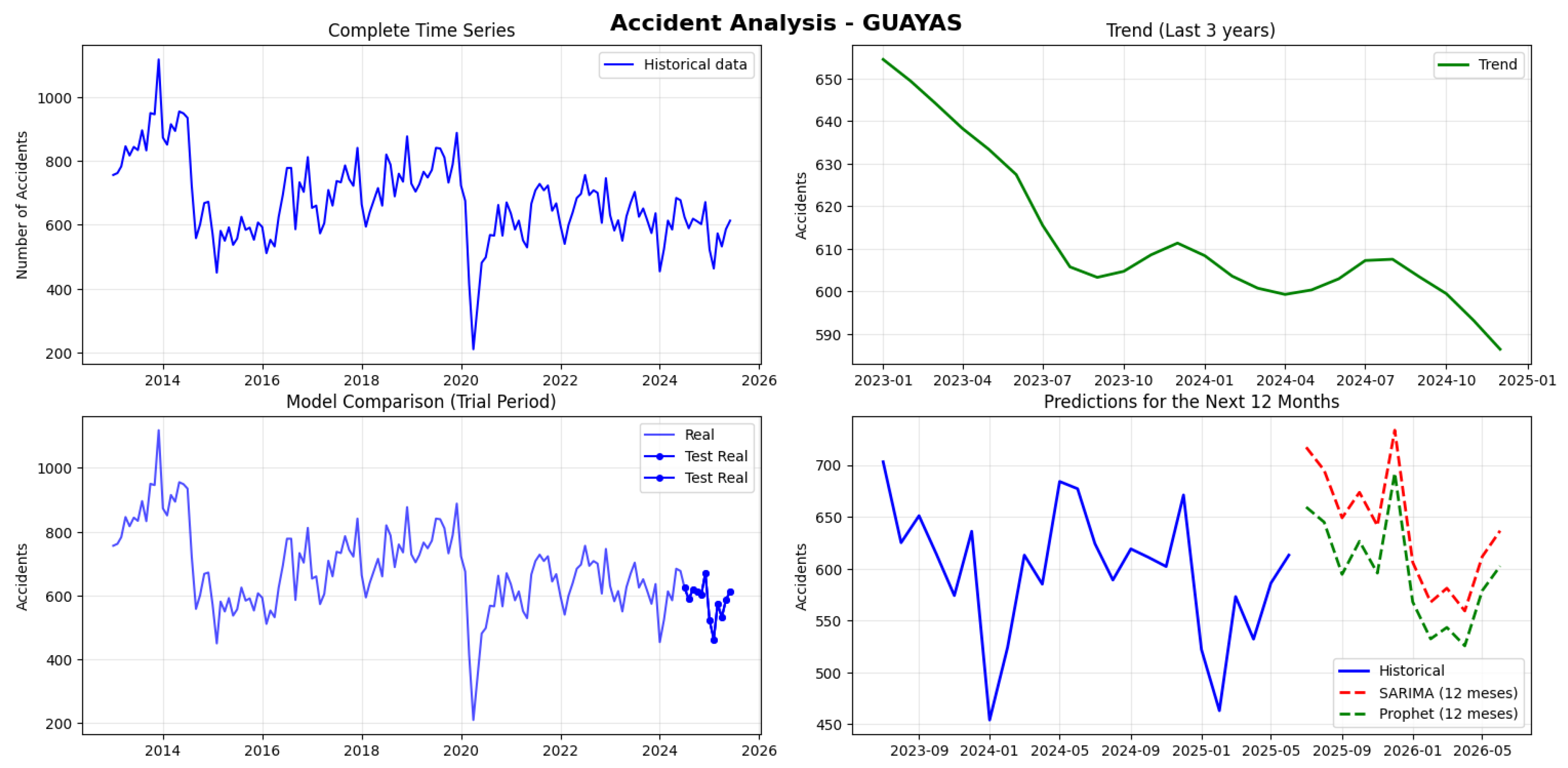

The analysis of the traffic accident time series in Guayas (101,179 total accidents) reveals a stationary series (P-value of ), which simplifies the modeling process.

The comparative evaluation between the models confirms a significant superiority of the Prophet model over SARIMA.

Prophet demonstrated much higher accuracy with a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 4.91% and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 33.76.

SARIMA recorded considerably higher metrics (MAPE of 9.77% and RMSE of 64.64).

Prophet’s performance represents a reduction of almost 50% in the average prediction error, positioning it as the most effective and stable model for this province. Prophet’s future projections suggest a seasonal pattern, predicting a peak in accidents in December 2025 (733) and a trough in February 2026 (568) (see

Figure 3).

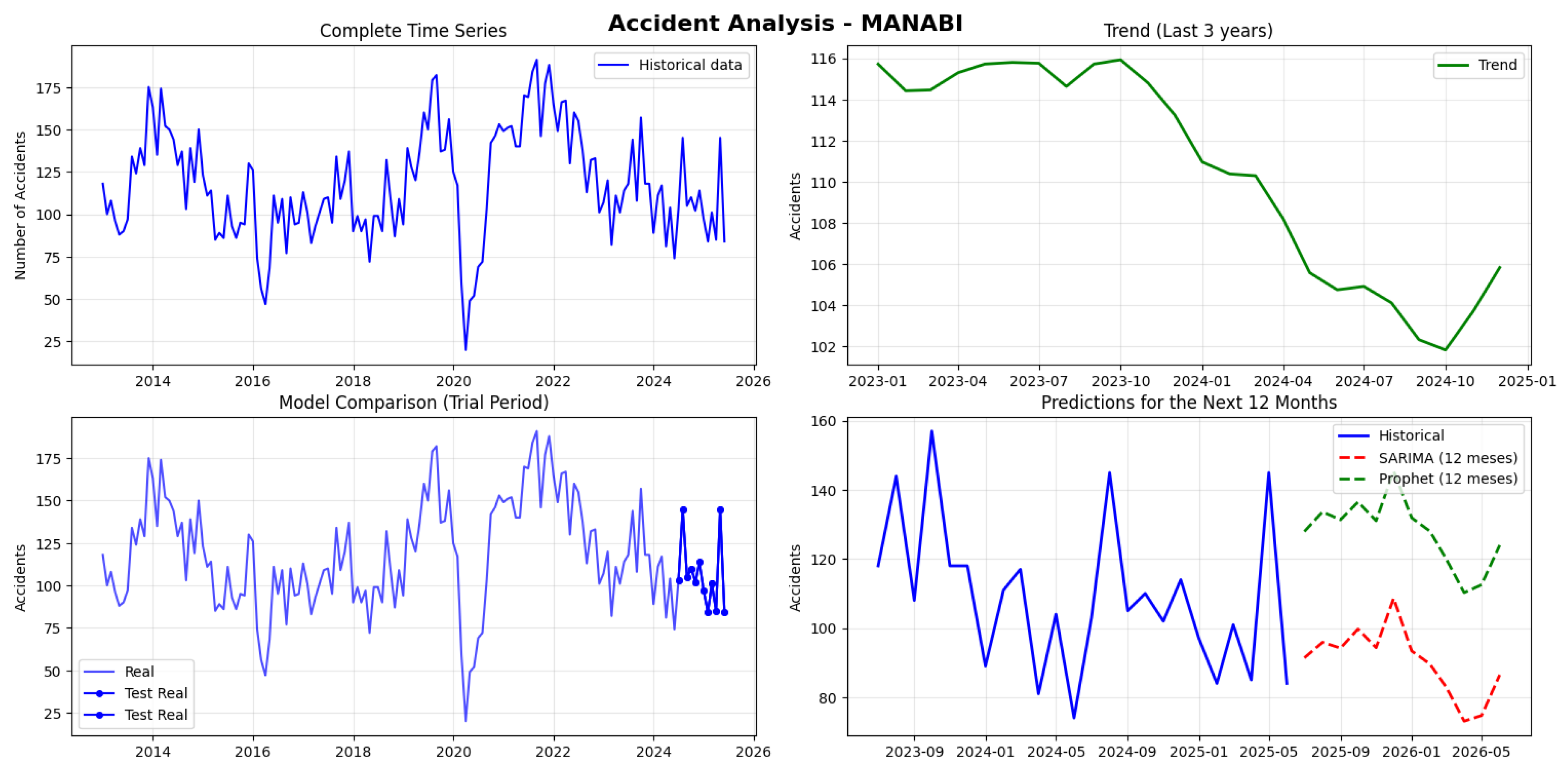

The

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal behavior and forecast performance of traffic accidents in Manabí province (2013–2025). The time series reveals fluctuations with peaks in 2014 and 2021, followed by a moderate decline during 2023–2024. The trend shows a gradual decrease with slight recovery in early 2025. Forecasts for July 2025–June 2026 indicate a mild downward trend, with SARIMA providing smoother and more accurate results (MAPE 14.22%, RMSE 26.32) compared to Prophet. The ADF test (p = 0.008) confirmed the stationarity of the series, and the predicted monthly accidents range between 73 and 109, suggesting moderate variability and stability in the short term.

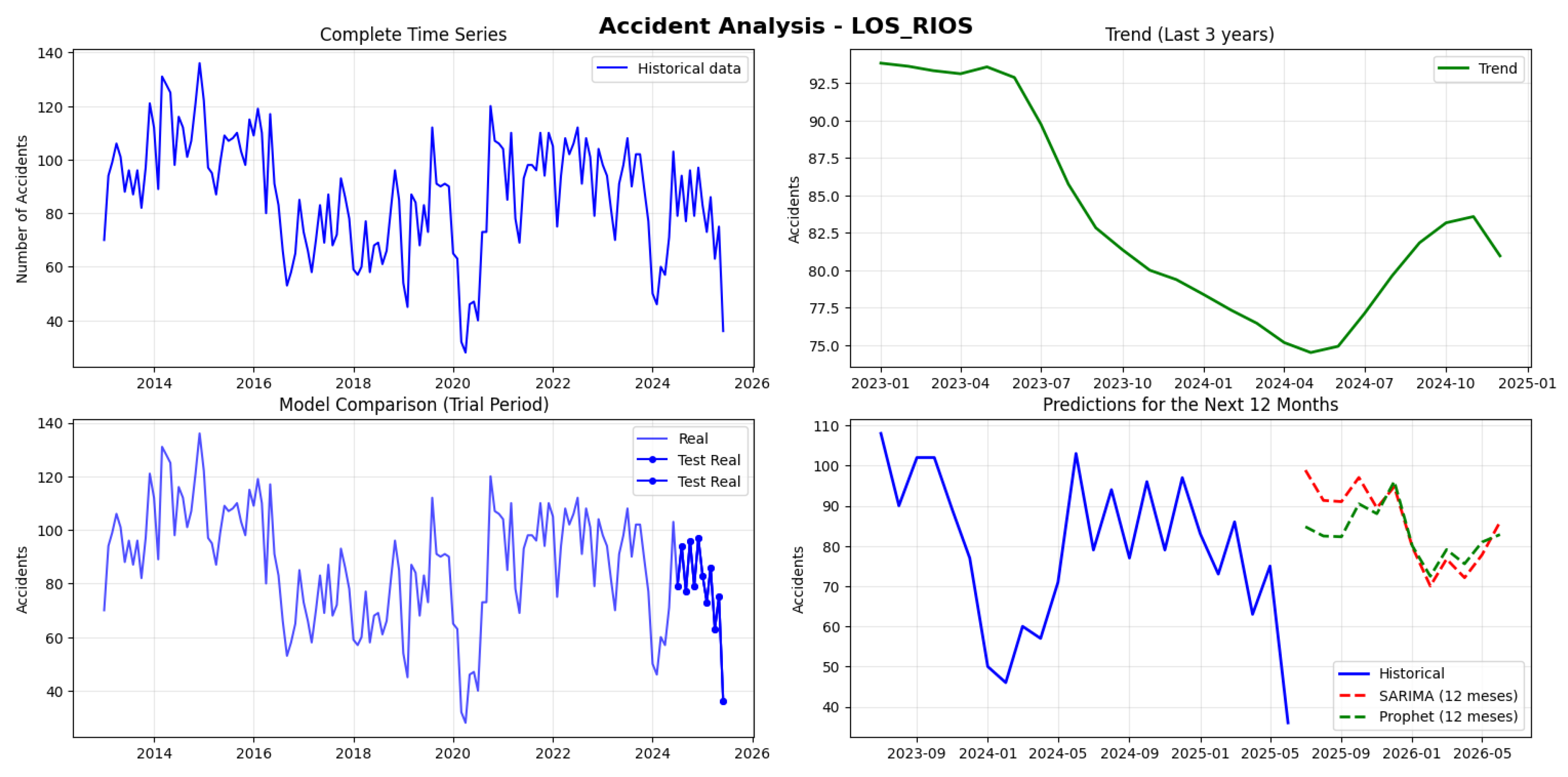

The

Figure 5 depicts the monthly evolution and forecasts of traffic accidents in Los Ríos province (2013–2025). The time series reveals fluctuations with peaks above 130 accidents during 2014–2015 and a downward trend after 2022. The recent trend shows a steady decline until mid-2024 with a mild recovery in 2025. Both SARIMA and Prophet models produced consistent forecasts for July 2025–June 2026, stabilizing around 70–100 accidents per month. Quantitatively, Prophet achieved slightly better accuracy (MAPE 17.91%, RMSE 15.14) than SARIMA (MAPE 19.88%, RMSE 16.85). The ADF test (p = 0.004) confirmed the series’ stationarity, supporting SARIMA’s validity and indicating a stable, moderately variable trend in road accidents for the province.

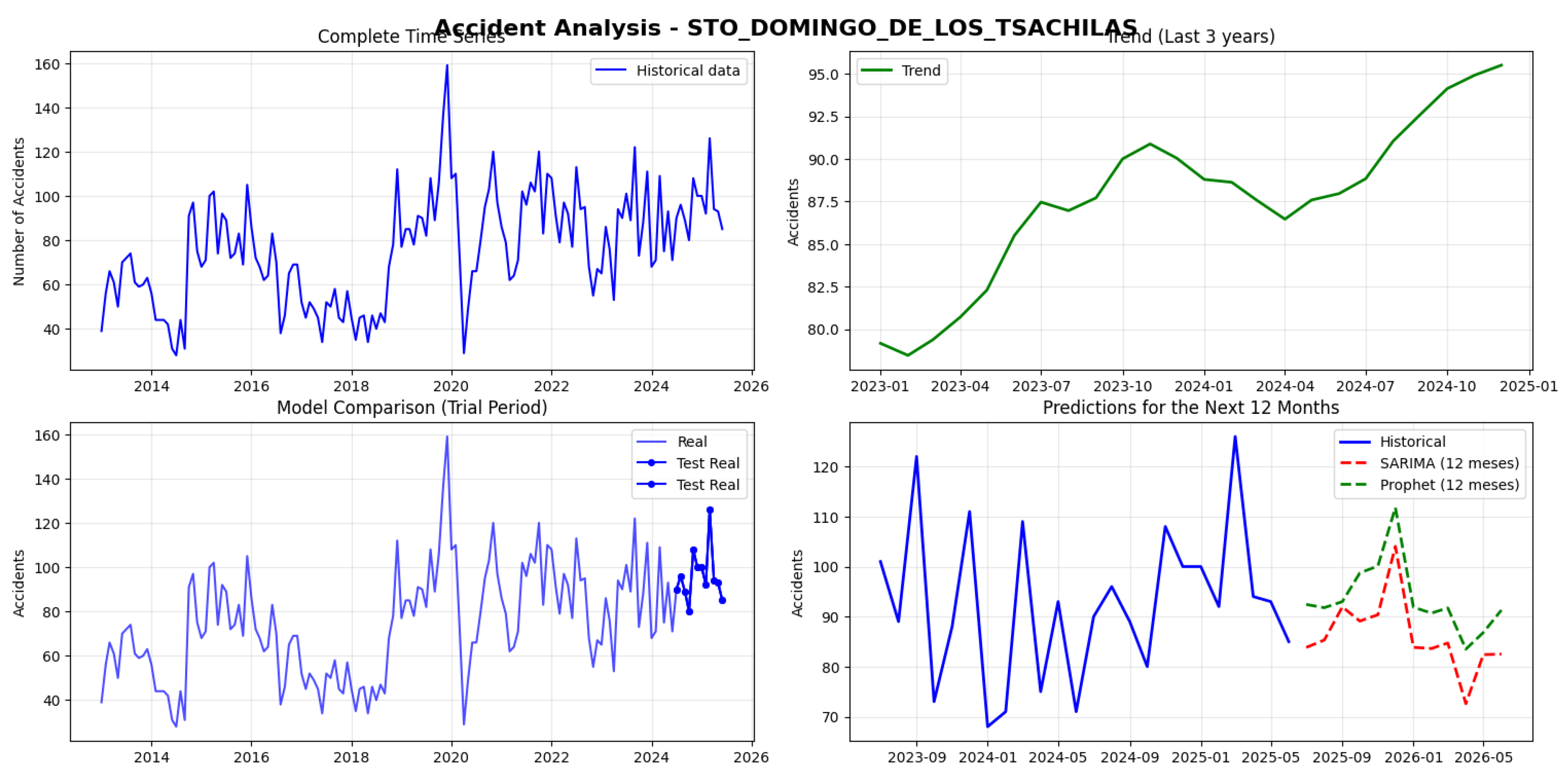

The

Figure 6 shows the monthly evolution of traffic accidents between 2013 and 2025, with projections extending to 2026. A total of 11,356 accidents were recorded, with a monthly average of 75.7 and values ranging between 28 and 159. Peaks were observed in 2014–2015 and 2019–2020, followed by stabilization after 2021. The stationarity test (p-value = 0.002) confirms that the series is suitable for ARIMA/SARIMA models. Both models demonstrate high predictive accuracy (MAPE < 15%), although Prophet outperforms SARIMA with a lower error (MAPE 9.67% vs. 12.35%). Forecasts for 2025–2026 indicate stability between 73 and 104 accidents, with a peak in December 2025 and stabilization around 82 by mid-2026. Overall, the series exhibits a predictable pattern, and Prophet provides the best overall performance.

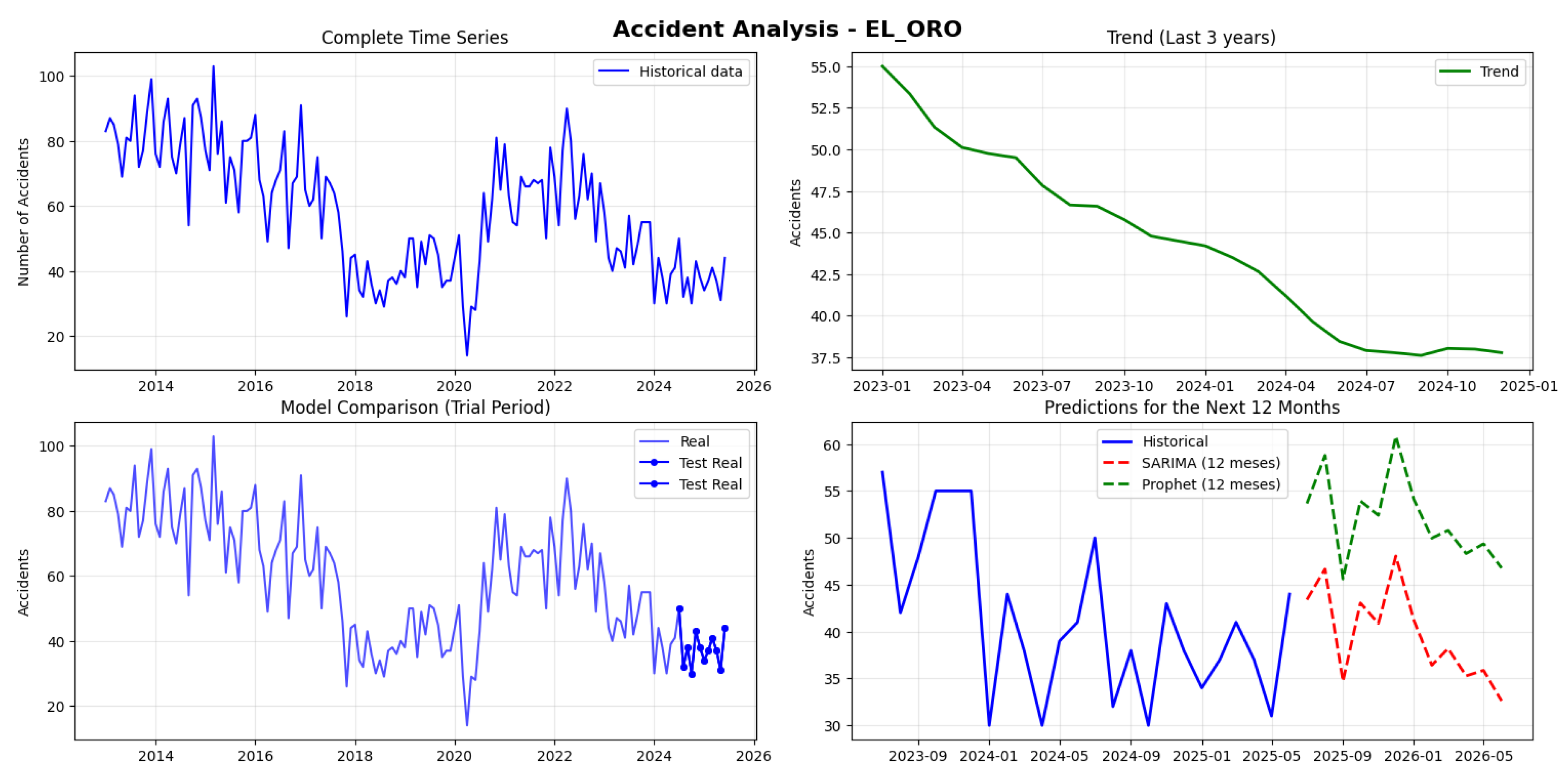

The

Figure 7 summarizes the temporal evolution and predictive analysis of traffic accidents in El Oro province (2013–2025).

Accidents peaked above 100 cases between 2014–2016, followed by a steady decline after 2018, as shown in the full time series. The recent trend (2023–2024) confirms a continued downward pattern, suggesting improved safety conditions.

Model validation indicates consistent predictive performance, while 12-month forecasts (July 2025–June 2026) show a stable range of 33–48 accidents per month. Quantitatively, SARIMA outperformed Prophet, with MAPE = 18.21% and RMSE = 7.97, versus Prophet’s MAPE = 40.60% and RMSE = 16.11. Despite the non-stationary series (), SARIMA demonstrated superior stability and accuracy in forecasting accident trends.

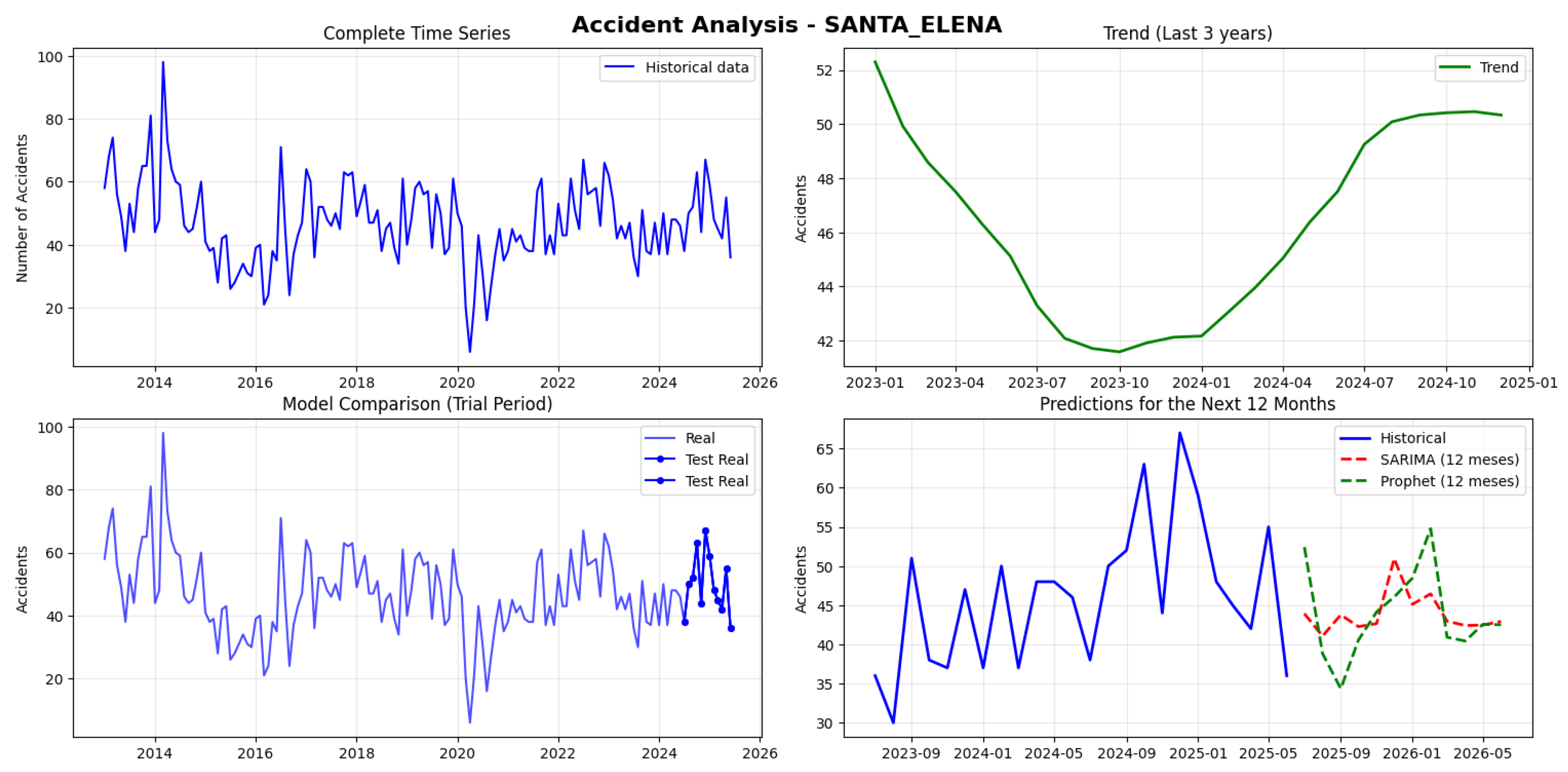

The

Figure 8 summarizes the temporal evolution and predictive modeling of traffic accidents in Santa Elena. The complete time series (top-left) shows high variability with peaks near 100 accidents (2014–2015) and stabilization between 40 and 60 after 2020. The trend (top-right) indicates a decline until early 2024, followed by a slight recovery in 2025. The model validation (bottom-left) reveals strong consistency between real and test data, while the 12-month forecasts (bottom-right) suggest a stable accident frequency between 41 and 51 cases per month. Quantitatively, the SARIMA model outperformed Prophet (MAPE = 15.29%, RMSE = 10.31 vs. MAPE = 20.58%, RMSE = 12.78). The ADF test (p = 0.000) confirmed stationarity, validating SARIMA’s assumptions and indicating stable medium-term accident trends.

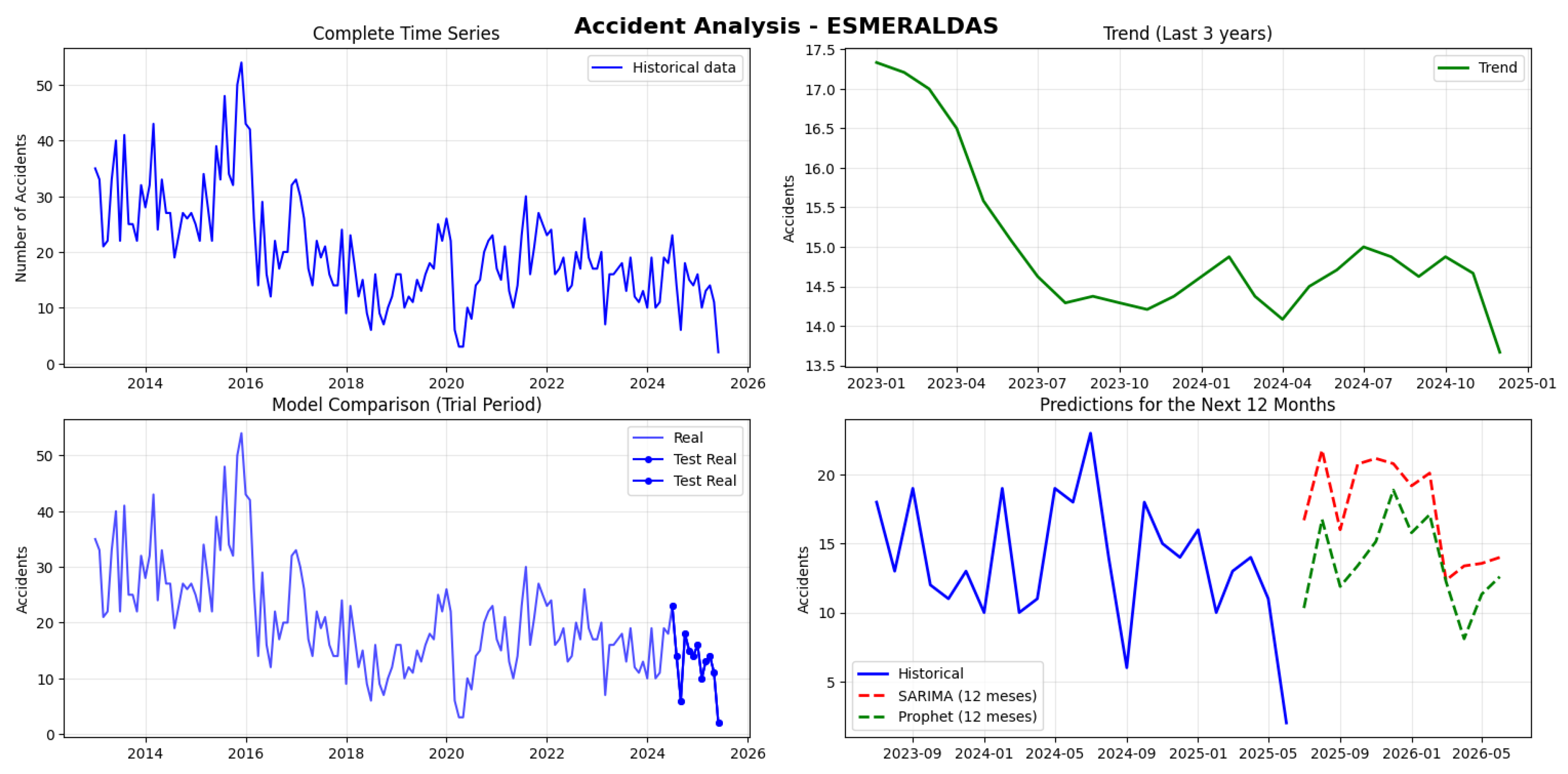

The analysis focuses on the traffic accident time series for the province of Esmeraldas, which is characterized by low volume (3039 total accidents, 20.3 monthly average) and extreme volatility (minimum of 2, maximum of 54). Methodologically, the series is NON-stationary (P-value of ), implying the need for differentiation in the SARIMA model.

In the comparative evaluation, although both models exhibit a high

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) (Prophet:

; SARIMA:

), which is typical for low-volume series, the

Prophet model demonstrates clear superiority. Prophet records an

MAPE that is 18.44 percentage points lower and an

RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) of

(compared to

for SARIMA). This lower metric in absolute terms positions

Prophet as the most accurate and stable model for forecasting accidents in this non-stationary, low-volume time series (see

Table 3).

Figure 9.

Comparative Analysis of SARIMA vs. Prophet and Accident Prediction in Esmeraldas.

Figure 9.

Comparative Analysis of SARIMA vs. Prophet and Accident Prediction in Esmeraldas.

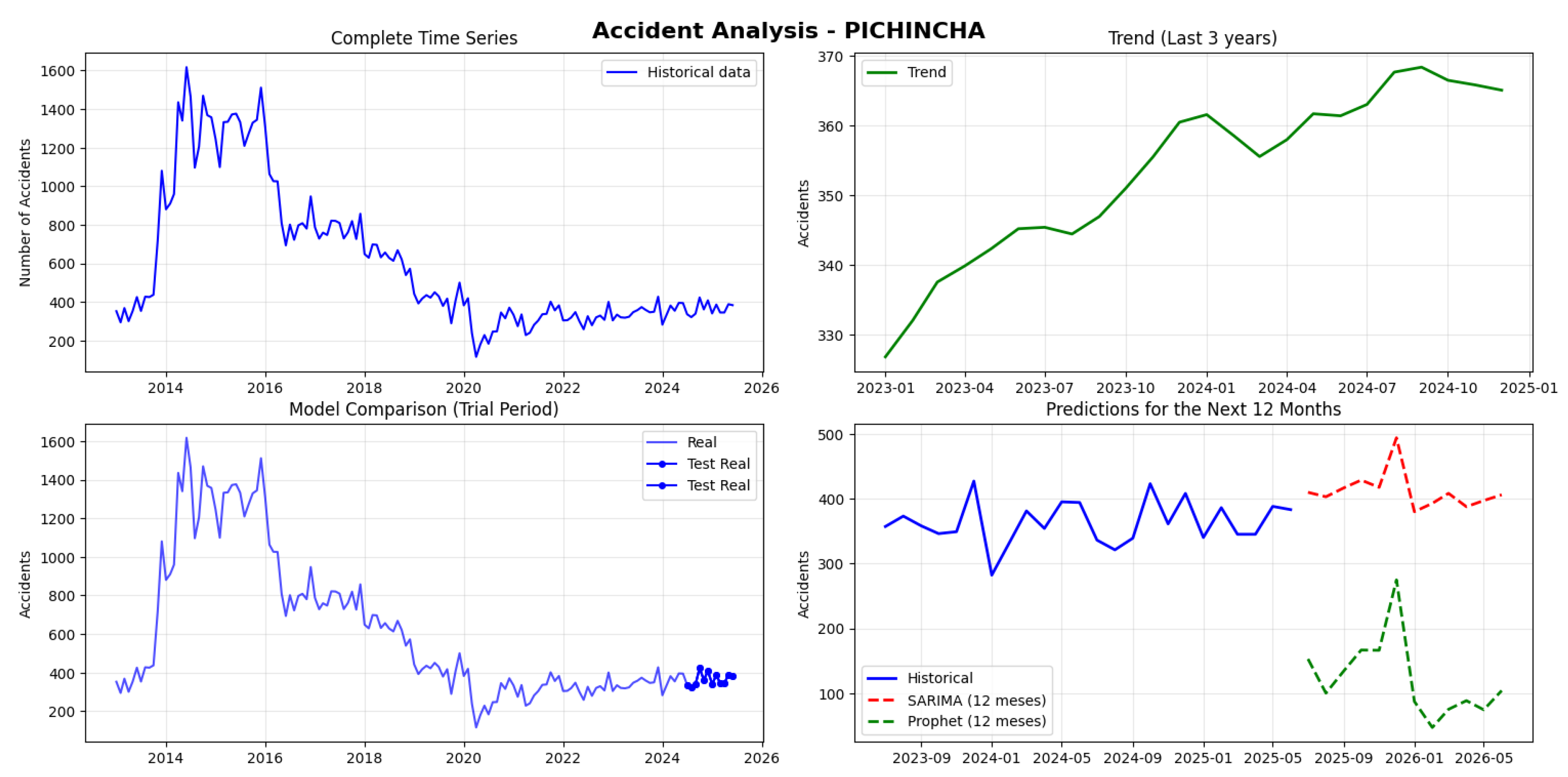

4.2. Andean Region

90,636 accidents were recorded with a monthly average of 604.2, showing high variability between 115 and 1,617 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.463), justifying the use of SARIMA. This model demonstrated high performance (MAPE: 13.38%, RMSE: 55.33), while Prophet had low performance (MAPE: 66.62%, RMSE: 248.24). SARIMA predictions for the next 12 months range between 380-494 accidents, with a peak in December 2025, showing overall stability with seasonal variations (see

Figure 10).

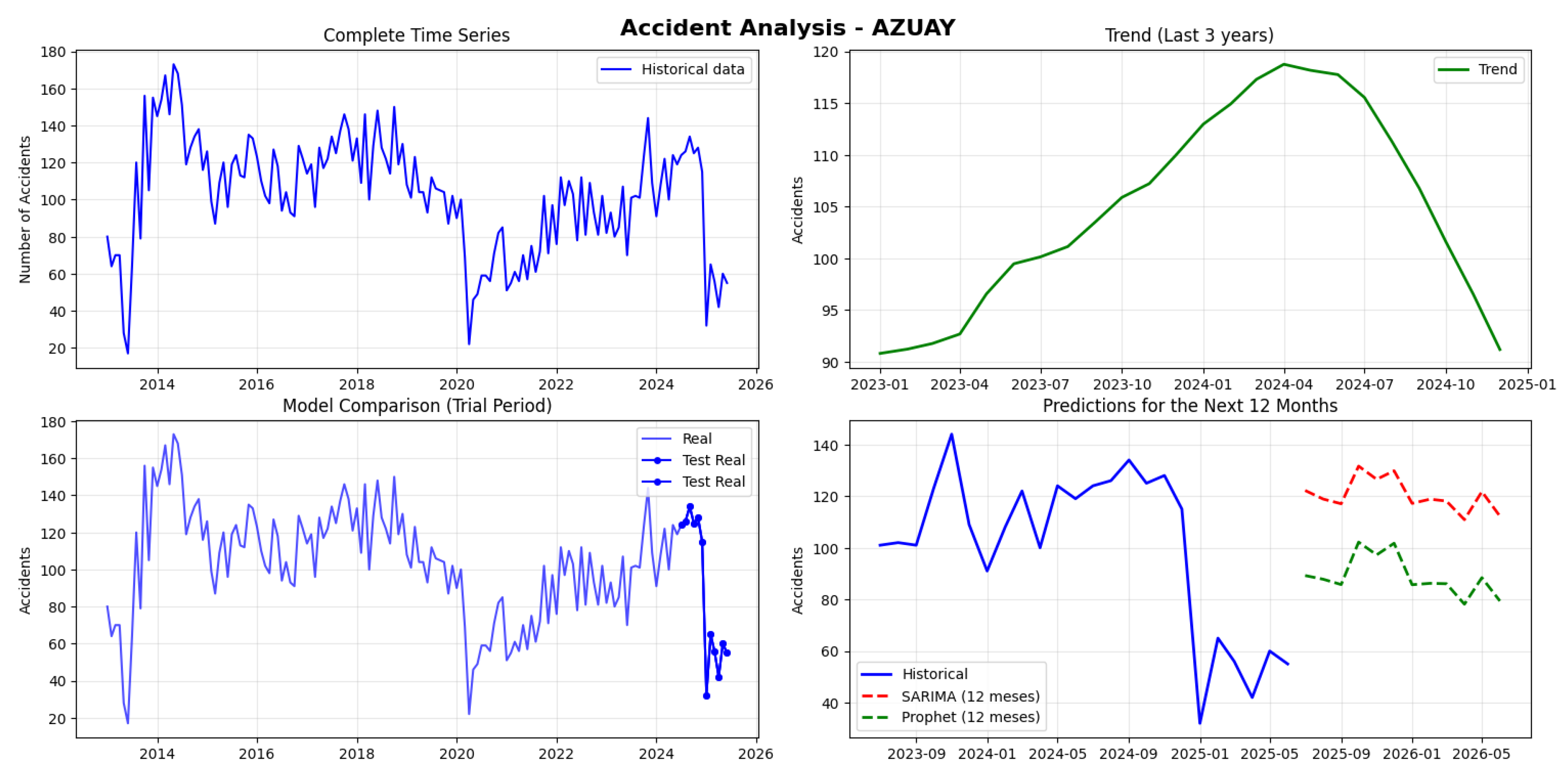

15,398 accidents were analyzed with a monthly average of 102.7, showing variability between 17 and 173 monthly incidents. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.076). The SARIMA model showed poor performance (MAPE: 72.51%, RMSE: 46.95), while Prophet demonstrated superior performance (MAPE: 48.34 RMSE: 33.64). SARIMA predictions for the next 12 months range between 111-132 accidents, showing stability but with limited reliability due to high error. It is recommended to use Prophet over SARIMA (see

Figure 11).

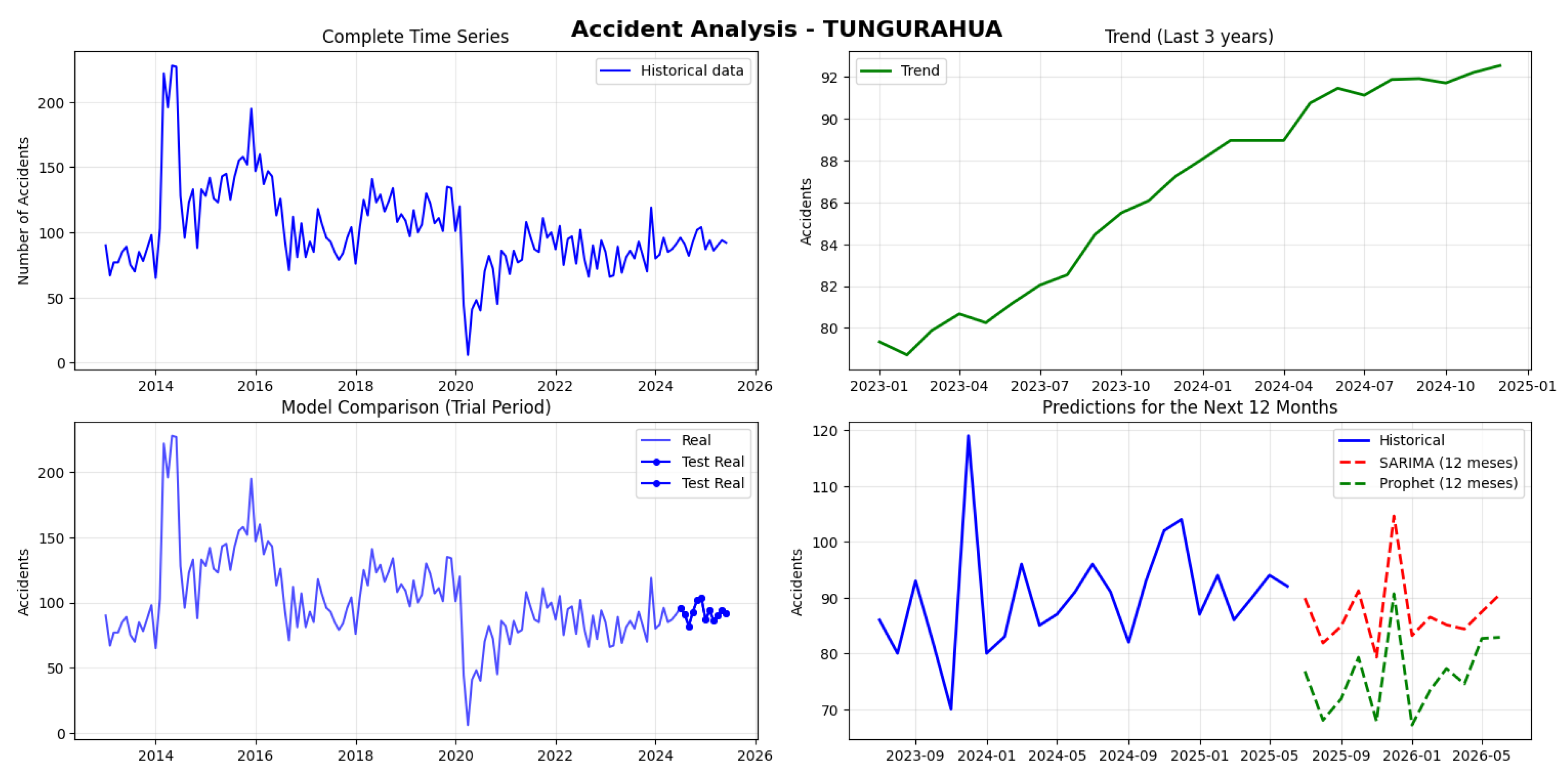

Our analysis of 15,280 traffic accidents in Tungurahua revealed a monthly average of 101.9, though the data showed significant fluctuations from as few as 6 to as many as 228 accidents in a single month. The data pattern over time is not stationary, confirming the presence of underlying trends or seasonal effects.

In our model evaluation, the SARIMA model demonstrated exceptional performance, with a very low prediction error, significantly outperforming the Prophet model.

Looking ahead, the SARIMA model forecasts a relatively stable trend for the next 12 months, with predicted accidents ranging between 79 and 105 per month. A noticeable peak of 105 accidents is anticipated for December 2025 (see

Figure 12).

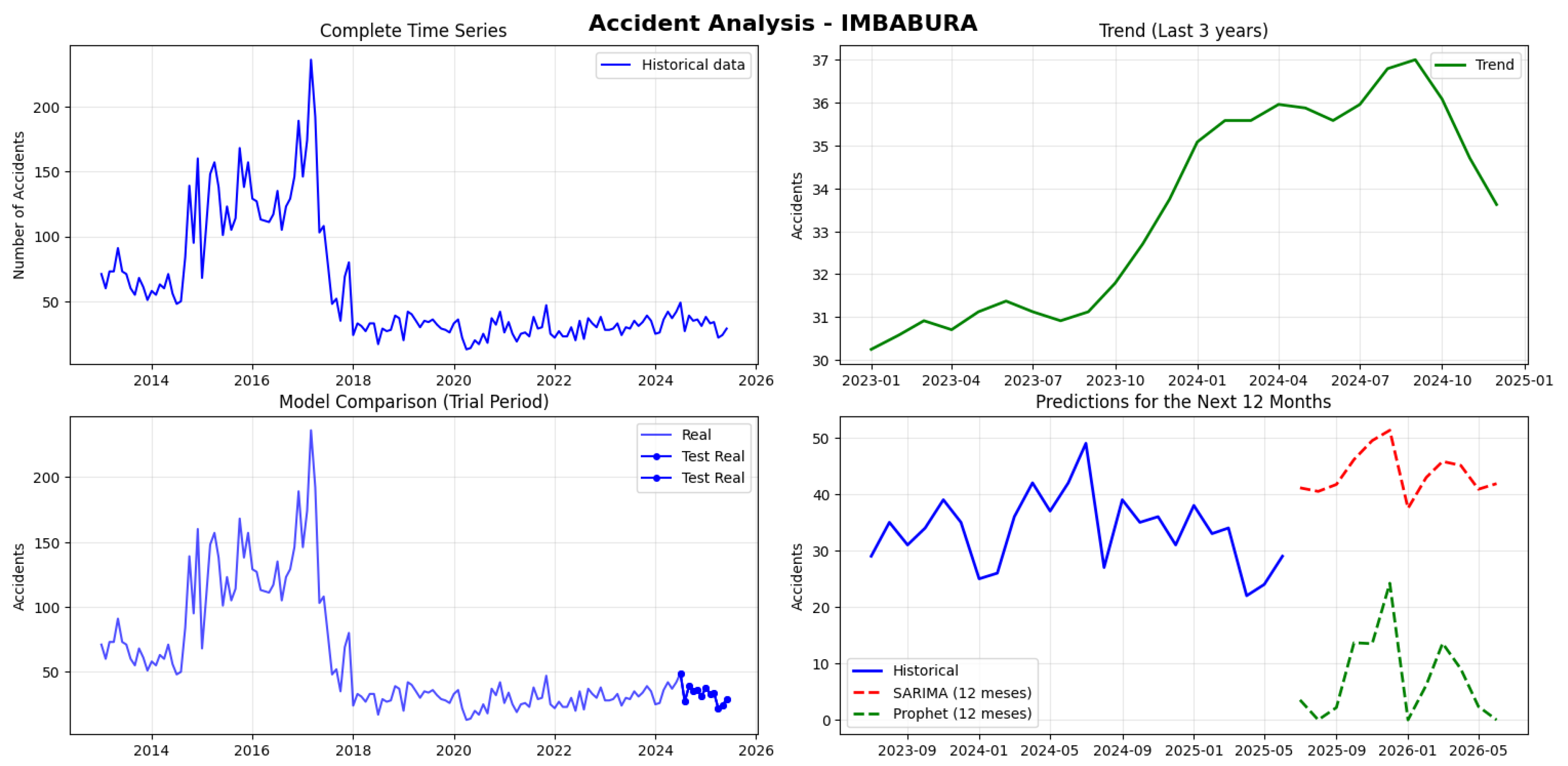

The accident data in Imbabura reveals a complex picture, with 8,850 total accidents and a monthly average of 59, but with high variability: ranging from 13 to 236 accidents in different months, suggesting the influence of extraordinary factors.

When comparing predictive models, SARIMA achieved an error margin of 41%, which, while high, significantly outperforms Prophet’s 77% error, making it the best available option, though it should be used with caution.

Projections for the next year estimate between 37 and 51 monthly accidents, generally below the historical average. It is recommended to investigate the causes of historical peaks and explore complementary methods to improve predictability (see

Figure 13).

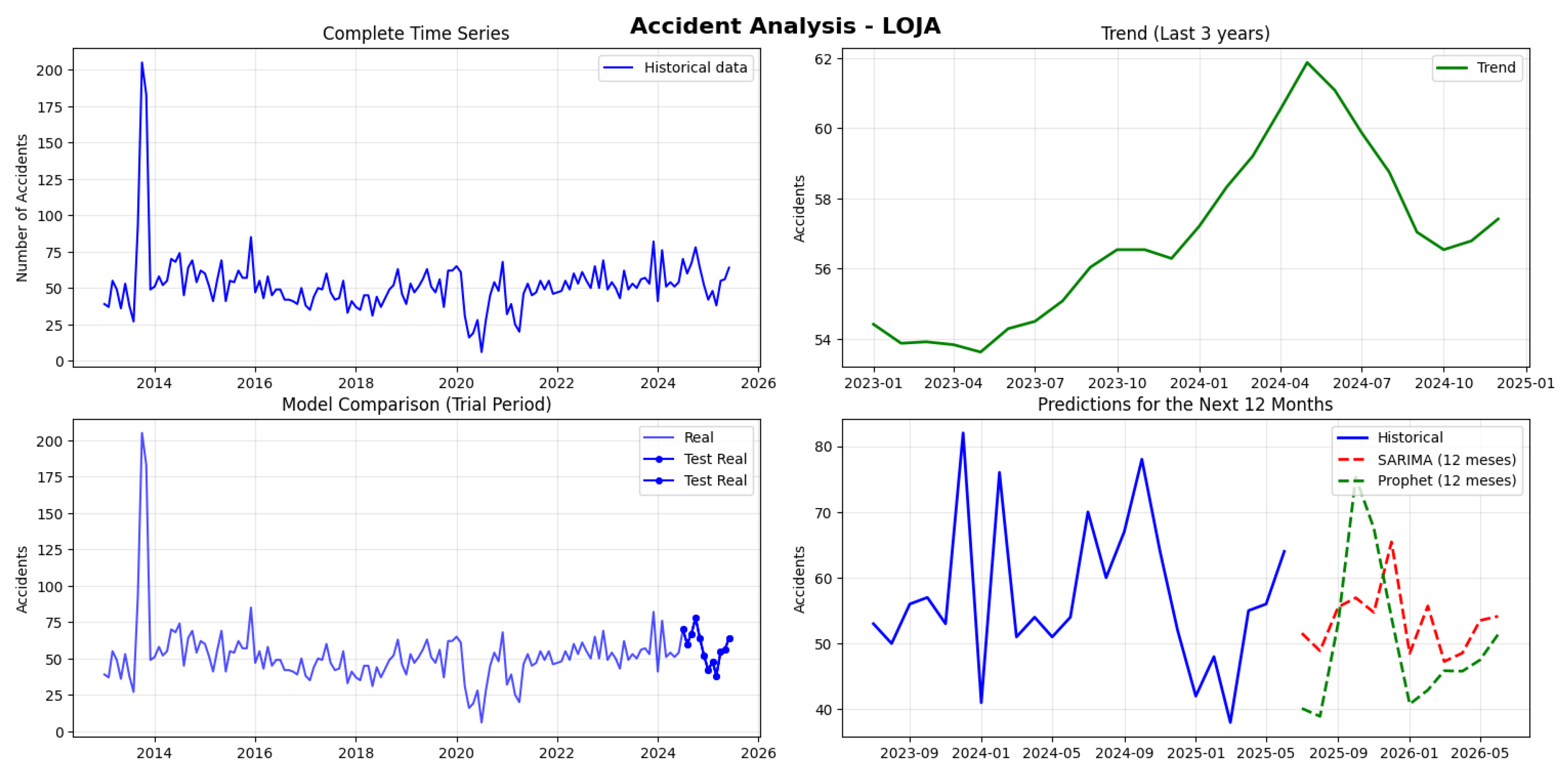

When analyzing Loja, a total of 7,844 accidents were found with a monthly average of 52.3. However, monthly figures have varied dramatically—from just 6 accidents in the calmest month to 205 in the most critical one—indicating exceptional events in the province’s history.

The good news is that the data shows consistent patterns over time, making accident prediction more reliable. When comparing forecasting methods, both models perform acceptably, with Prophet having a slight advantage, predicting with a 16.4% error compared to SARIMA’s 18.07

Projections for the next year indicate between 47 and 65 monthly accidents, remaining close to the historical average. It is observed that December would be the most critical month with 65 projected accidents, while January would show the lowest activity with 48. This stability in the predictions gives us greater confidence for preventive planning (see

Figure 14).

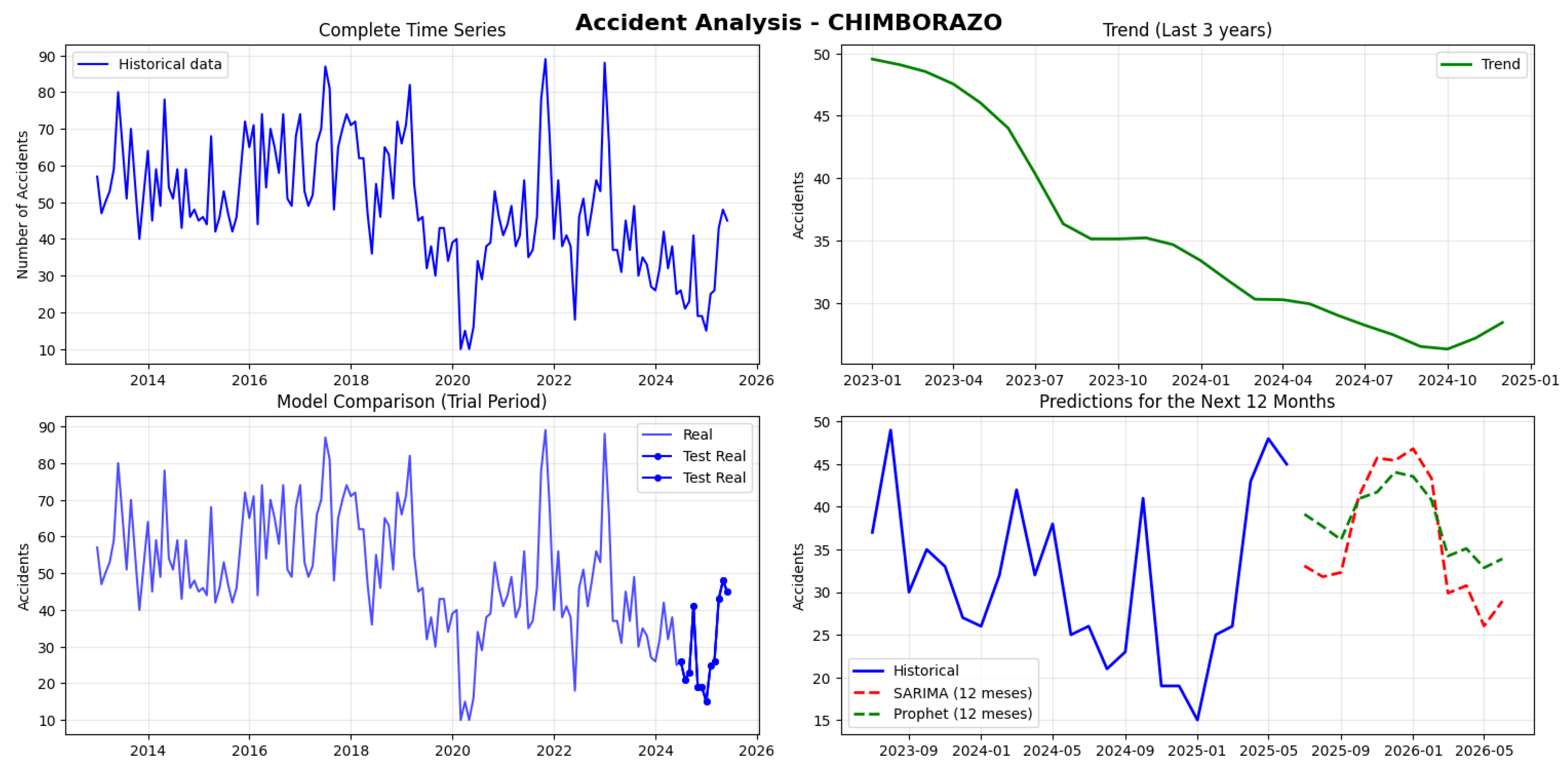

Chimborazo recorded 7,342 accidents with a monthly average of 48.9, showing moderate variability between 10 and 89 monthly accidents. Although the series is stationary (p-value: 0.001), a condition that normally favors prediction, both models performed poorly. SARIMA had an error of 67.48% and Prophet 66.55%, levels that are unacceptable for practical use. SARIMA projections for the next 12 months range between 26-47 accidents, below the historical average. The contradiction between stationarity and the high errors suggests that the models are not capturing non-linear patterns, dominant external factors, or possible random behavior in the data (see

Figure 15)

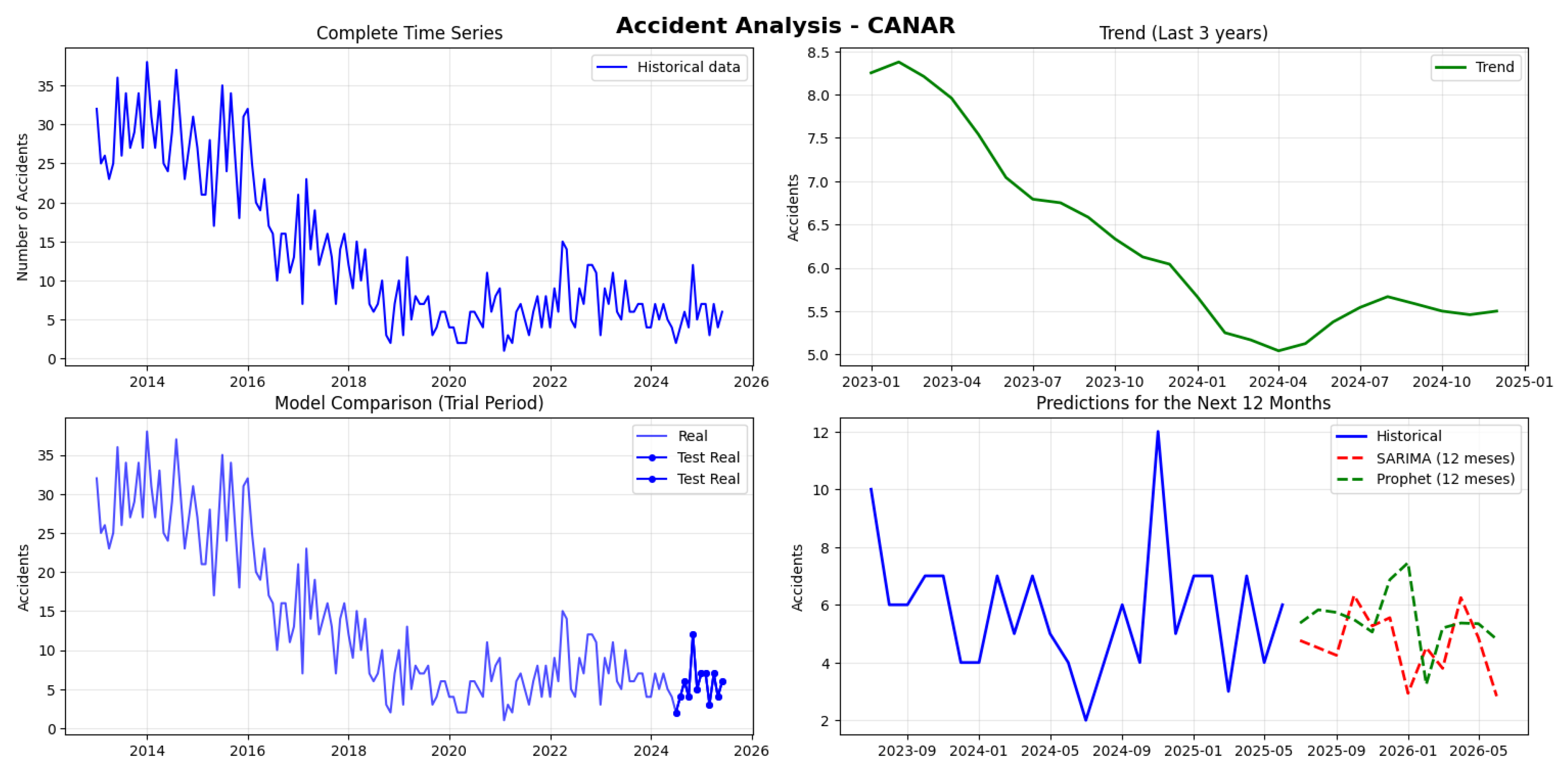

Cañar recorded 1,993 accidents in total, making it the province with the lowest volume analyzed. Its monthly average is 13.3 accidents, but with significant relative variability, having fluctuated between 1 and 38 accidents per month. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.688), which complicates predictive modeling.

When comparing the models, SARIMA showed an error of 42.53%, marginally outperforming Prophet (46.76%), with both showing low absolute errors. The performance is acceptable considering the reduced scale of the data.

SARIMA projections for the next 12 months predict between 3 and 6 monthly accidents, well below the historical average, with the highest values in October and December 2025 (6 accidents) and the lowest in January and June 2026 (3 accidents) (see

Figure 16).

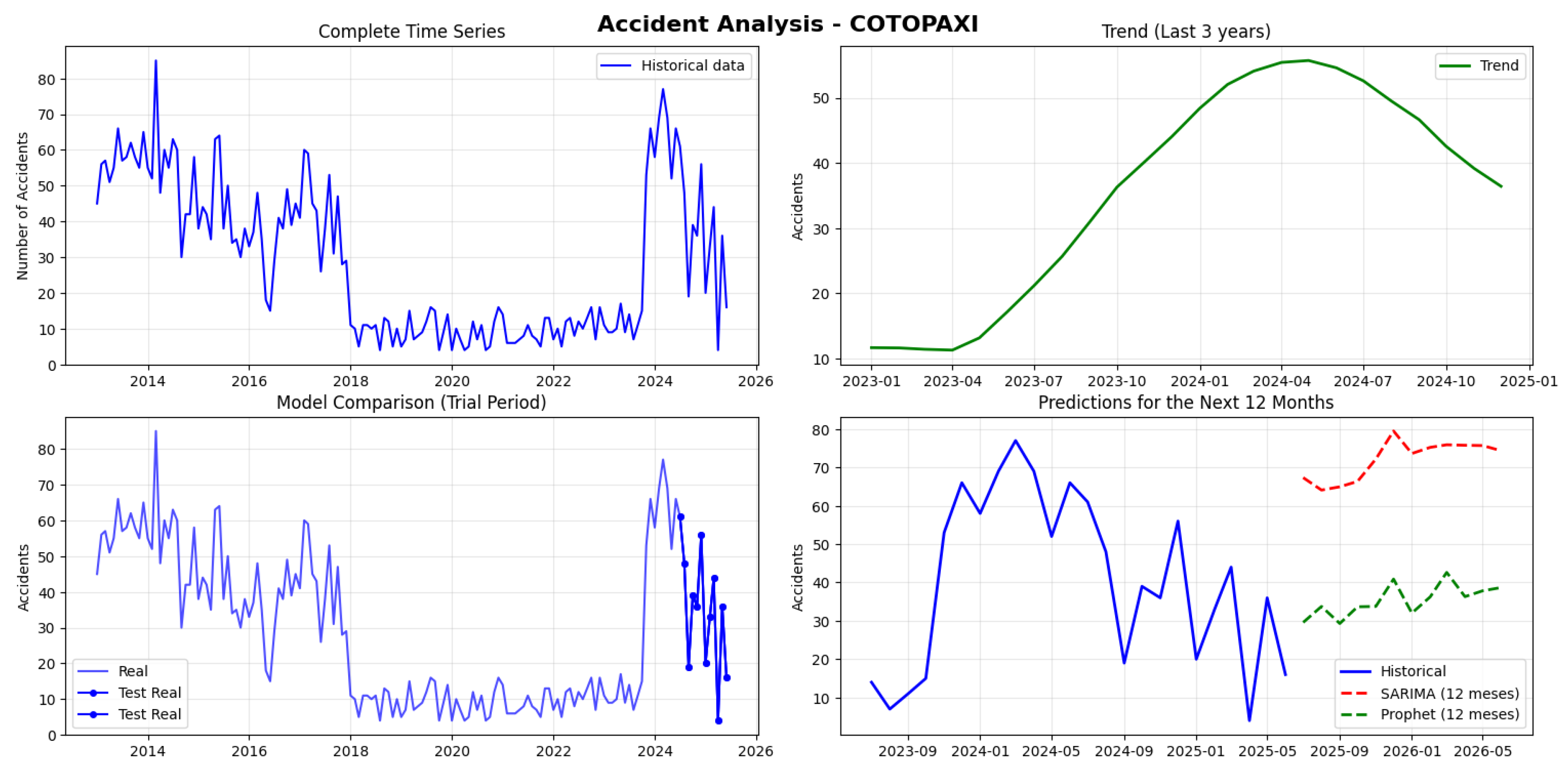

Cotopaxi recorded 4,371 accidents with a monthly average of 29.1, showing high variability between 4 and 85 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.132). Both predictive models failed severely: SARIMA showed an extreme error of 269.65%, while Prophet, although better, maintained a critical error of 100.83%. The SARIMA projections (64-79 monthly accidents) lack credibility as they double or triple the historical average (see

Figure 17).

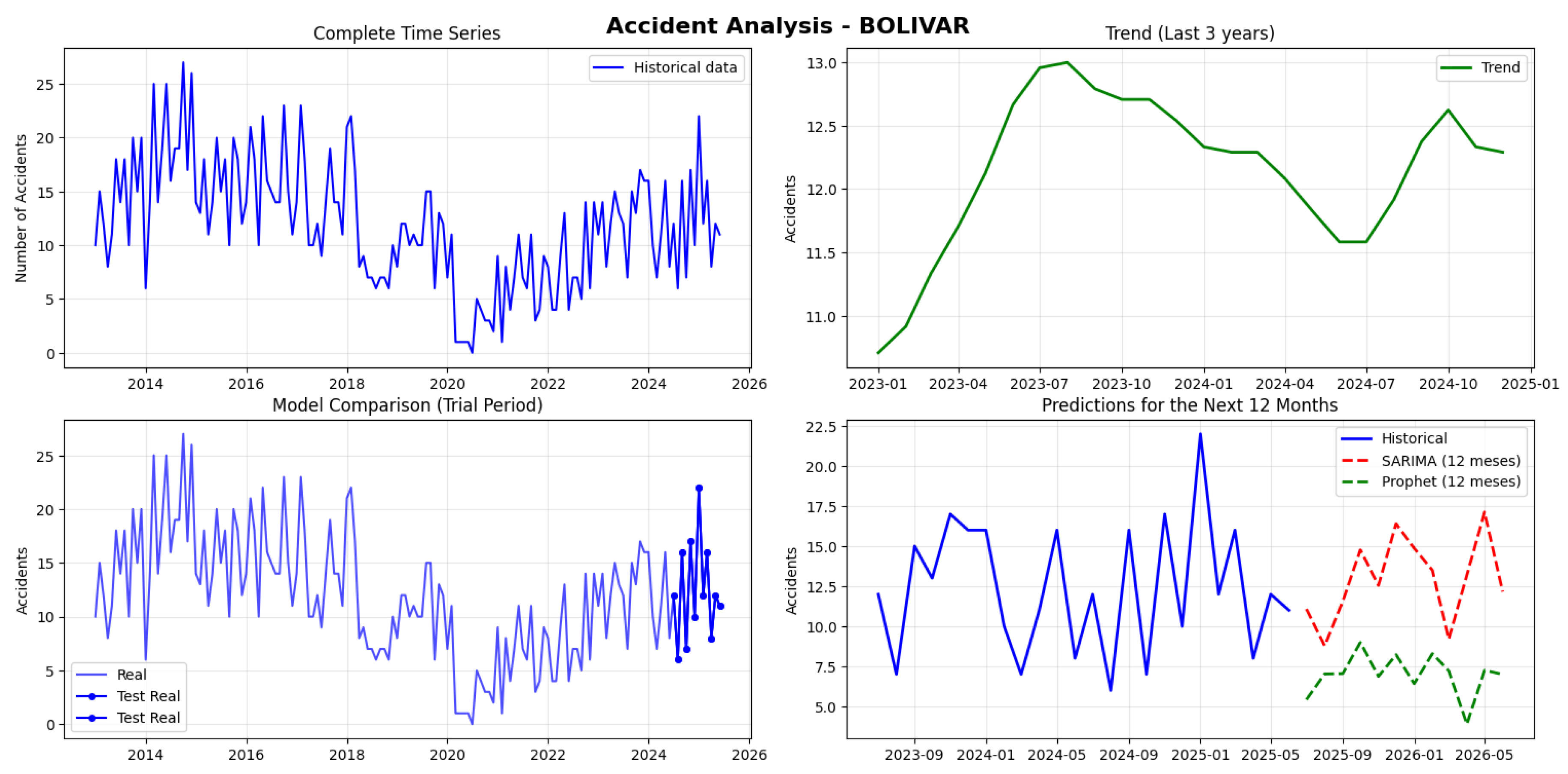

Bolívar recorded 1,787 accidents with a monthly average of 11.9, showing controlled variability between 0 and 27 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.174). SARIMA demonstrated better performance (MAPE: 40.72%, RMSE: 5.03) than Prophet (MAPE: 43.11%, RMSE: 7.20), showing clear superiority in both metrics. SARIMA projections for the next 12 months range between 9-17 accidents, aligning with the historical average, with the highest peak in May 2026 (17 accidents) and the lowest values in August 2025 and March 2026 (9 accidents). The results indicate a favorable scenario with recognizable seasonal patterns and stable projections that enable reliable planning (see

Figure 18).

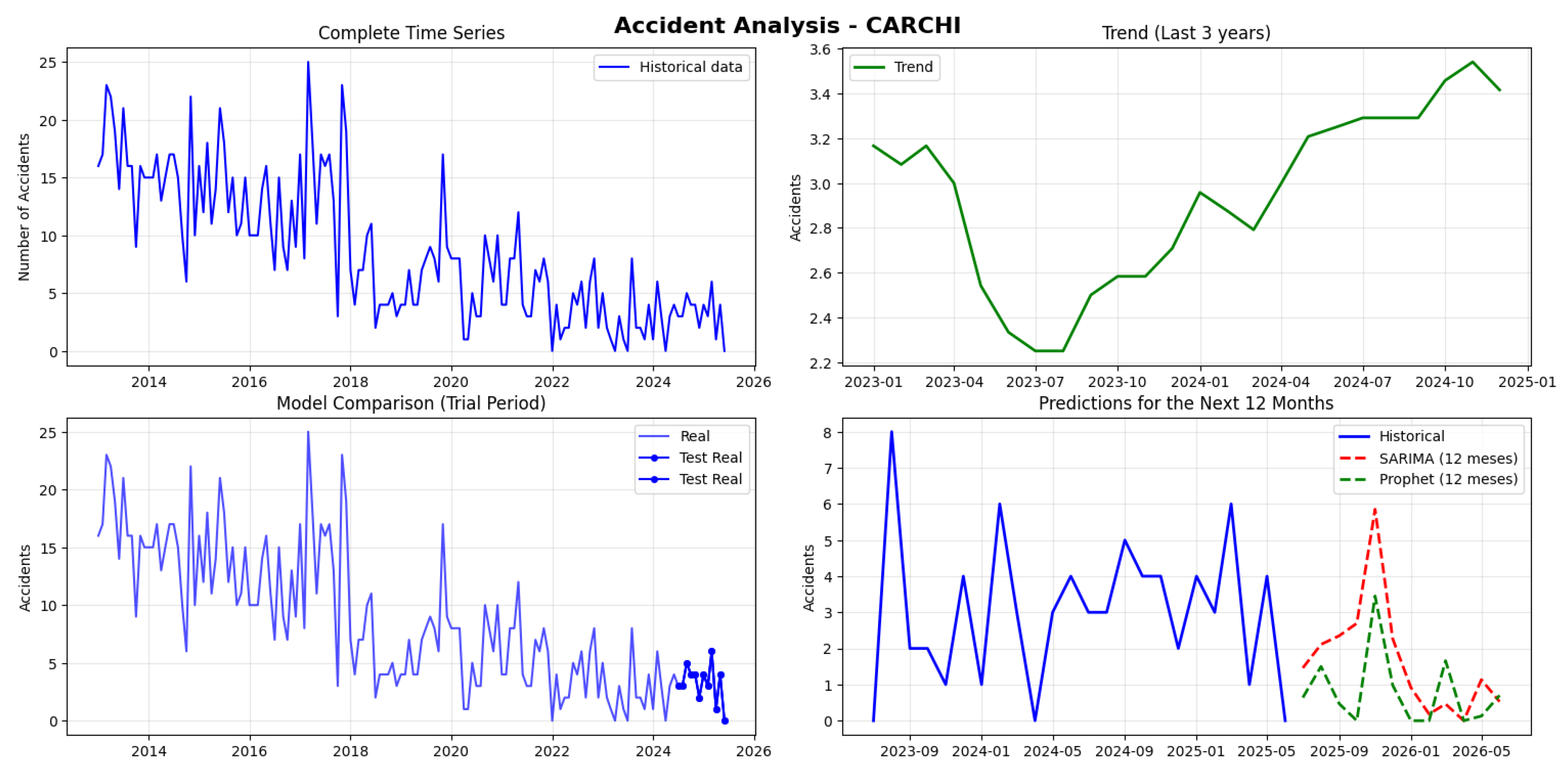

Carchi recorded 1,293 accidents with a very low monthly average of 8.6, ranging between 0 and 25 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary. A critical technical failure was identified in both models: the MAPE values are numerically absurd (trillions of percent), indicating a computational error, possibly due to division by zero or corrupted data. However, the RMSE is low (2.47-2.97) and the SARIMA projections (0-6 monthly accidents) are consistent with the low historical volume, although well below the average (see

Figure 19).

The analysis of the provinces shows that Pichincha has the highest accident volume (90,636), while Carchi has the lowest (1,293). SARIMA demonstrated better performance in high-volume provinces like Pichincha (MAPE 13.38%) and Tungurahua (6.07%), while Prophet was superior in Azuay (48.34%) and Loja (16.40%). Most series are not stationary, except for Loja and Chimborazo. Predictive errors vary significantly, from an excellent 6.07% in Tungurahua to a critical 100.83% in Cotopaxi, with lower-volume provinces presenting greater predictive challenges with MAPE generally above 40%. (see

Table 4).

4.3. Amazon Region

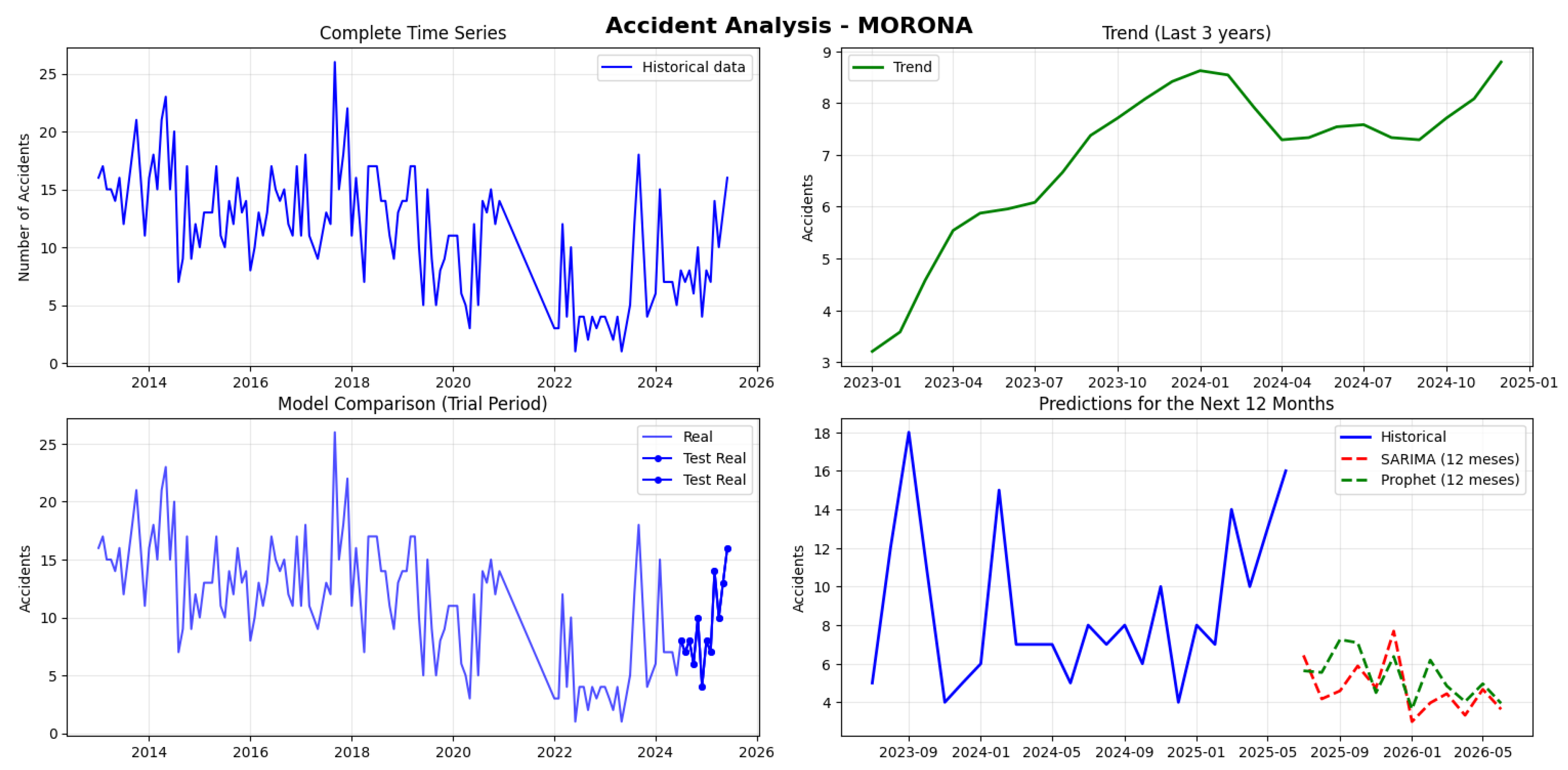

Morona Santiago recorded 1,553 accidents with a monthly average of 11.3, showing moderate variability between 1 and 26 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.324). Prophet demonstrated better performance (MAPE: 43.36%, RMSE: 5.73) than SARIMA (MAPE: 52.62%, RMSE: 6.16), clearly outperforming it in both metrics. The SARIMA projections for the next 12 months range between 3-8 accidents, well below the historical average, with the highest peak in December 2025 (8 accidents) and the lowest values in January and April 2026 (3 accidents) (see

Figure 20).

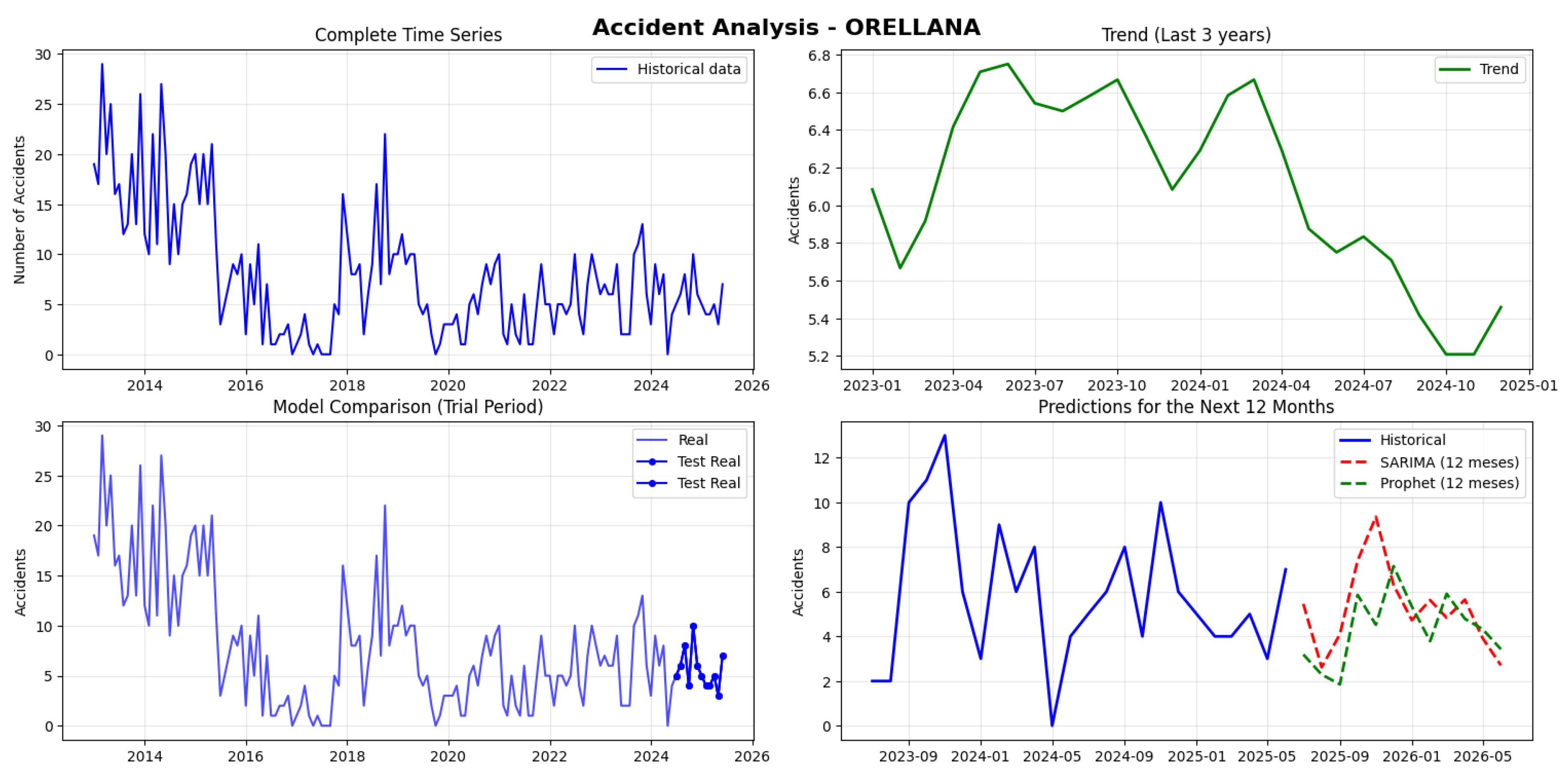

Orellana recorded 1,175 accidents with a very low monthly average of 7.8, showing high relative variability between 0 and 29 monthly accidents. The series is stationary (p-value: 0.012), a favorable characteristic. SARIMA demonstrated better performance (MAPE: 31.86%, RMSE: 2.27) than Prophet (MAPE: 37.87%, RMSE: 3.00), consistently outperforming it in both metrics. The SARIMA projections for the next 12 months range between 3-9 accidents, close to the historical average, with the highest peak in November 2025 (9 accidents) and the lowest values in August 2025 and June 2026 (3 accidents) (see

Figure 21).

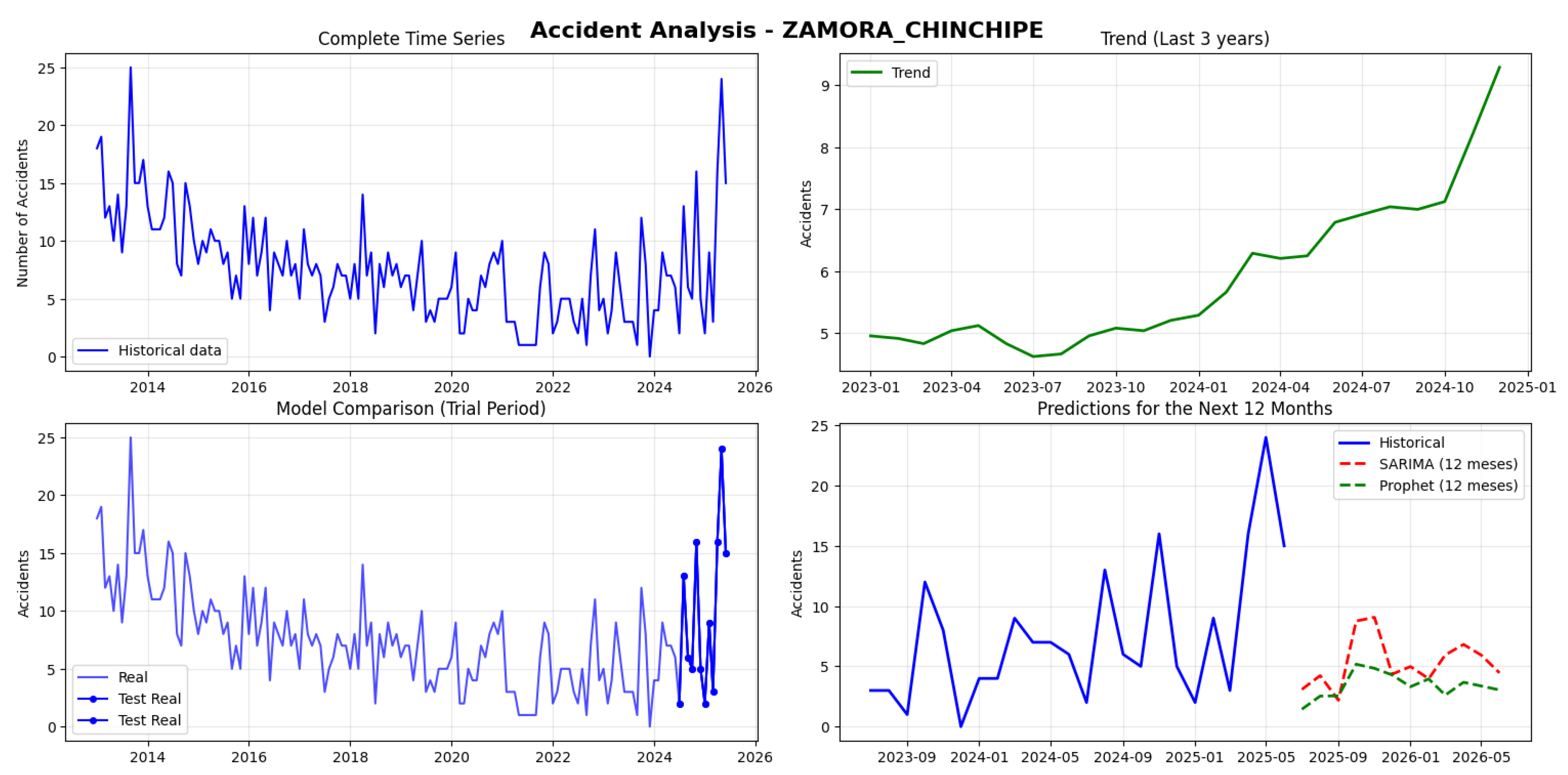

Zamora Chinchipe recorded 1,143 accidents with a very low monthly average of 7.6, showing significant variability between 0 and 25 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.251). Prophet demonstrated better performance (MAPE: 52.55%) than SARIMA (MAPE: 68.58%), although both models show high errors. The SARIMA projections for the next 12 months range between 2-9 accidents, close to the historical average, with peaks in October and November 2025 (9 accidents) and the lowest value in September 2025 (2 accidents) (see

Figure 22).

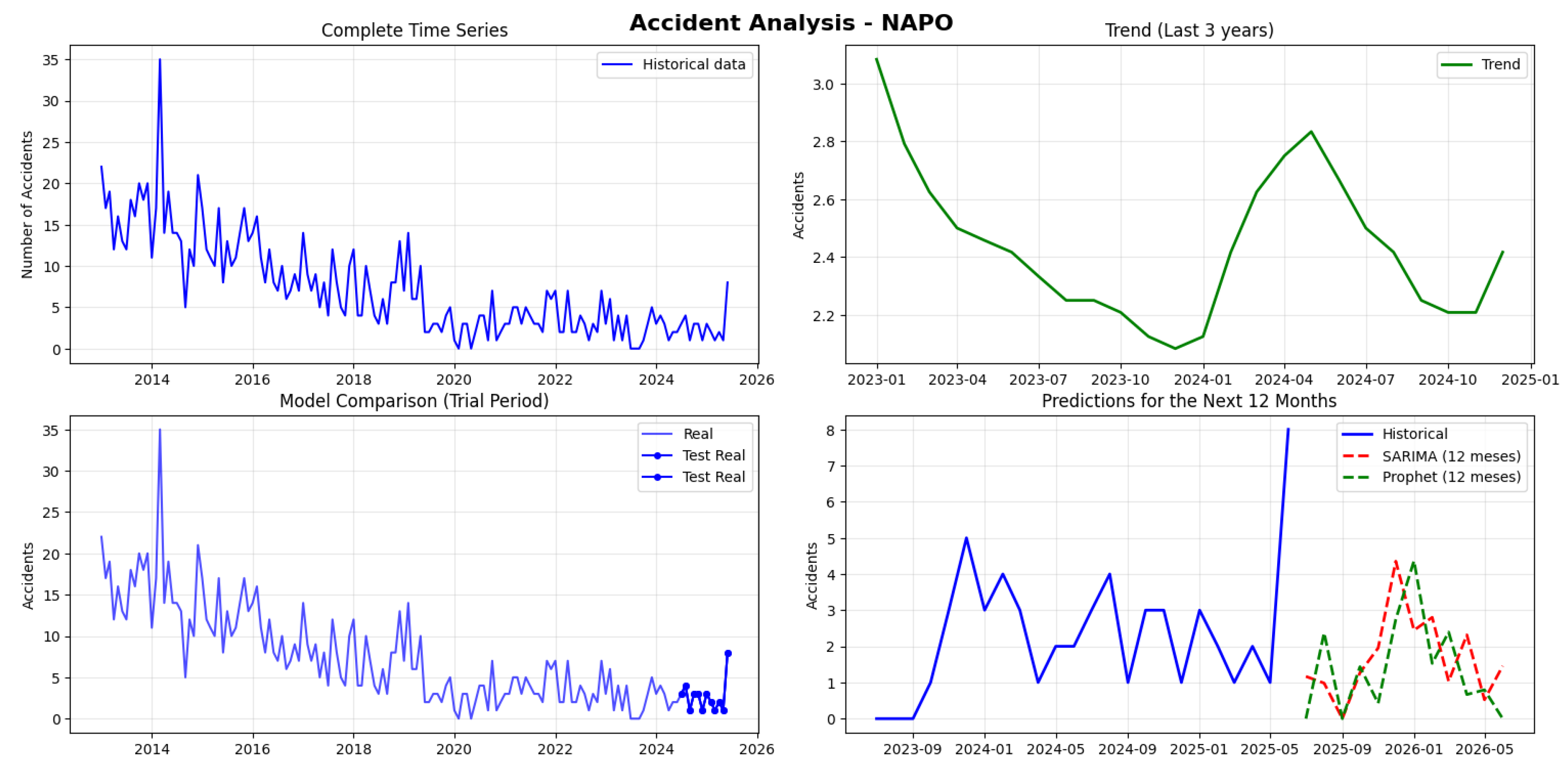

Napo recorded 1,091 accidents with an extremely low monthly average of 7.3, showing high variability between 0 and 35 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary (p-value: 0.383). SARIMA marginally outperformed Prophet with a MAPE of 72.63% versus 79.10%, although both models showed poor performance. The SARIMA projections for the next 12 months range between 0-4 accidents, well below the historical average, with the highest peak in December 2025 (4 accidents) and the lowest value in September 2025 (0 accidents) (see

Figure 23)

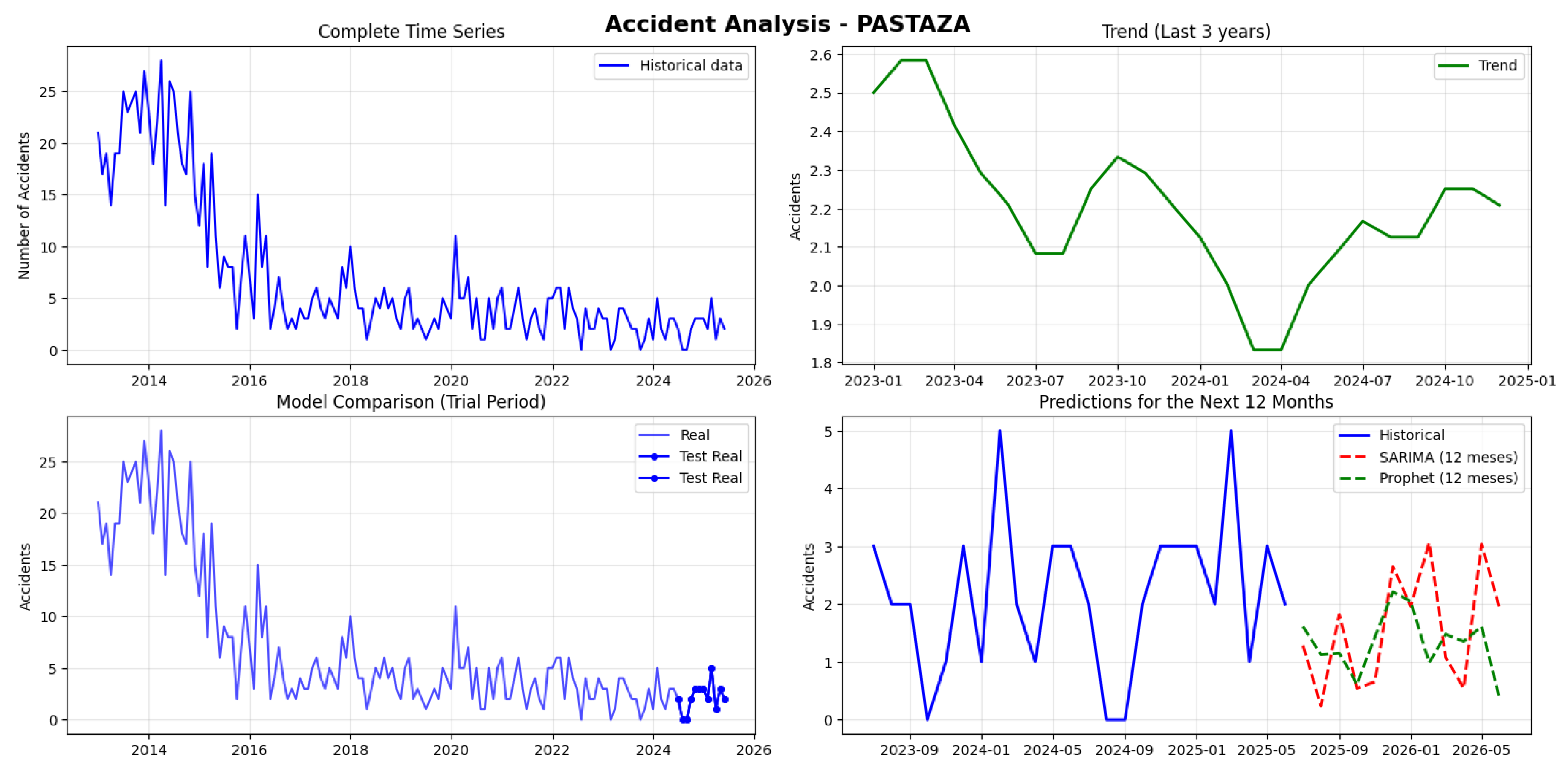

Pastaza recorded 1,041 accidents with an extremely low monthly average of 6.9, showing high variability between 0 and 28 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary. A critical computational failure was identified in both models, with numerically impossible MAPE values (trillions of percent), which completely invalidates this metric. However, the RMSE is very low (1.49-1.57) and the SARIMA projections (0-3 monthly accidents) are consistent with the low historical volume, although well below the average. The predictions show maximum values in December 2025 and February 2026 (3 accidents) and the minimum in August 2025 (0 accidents) (see

Figure 24).

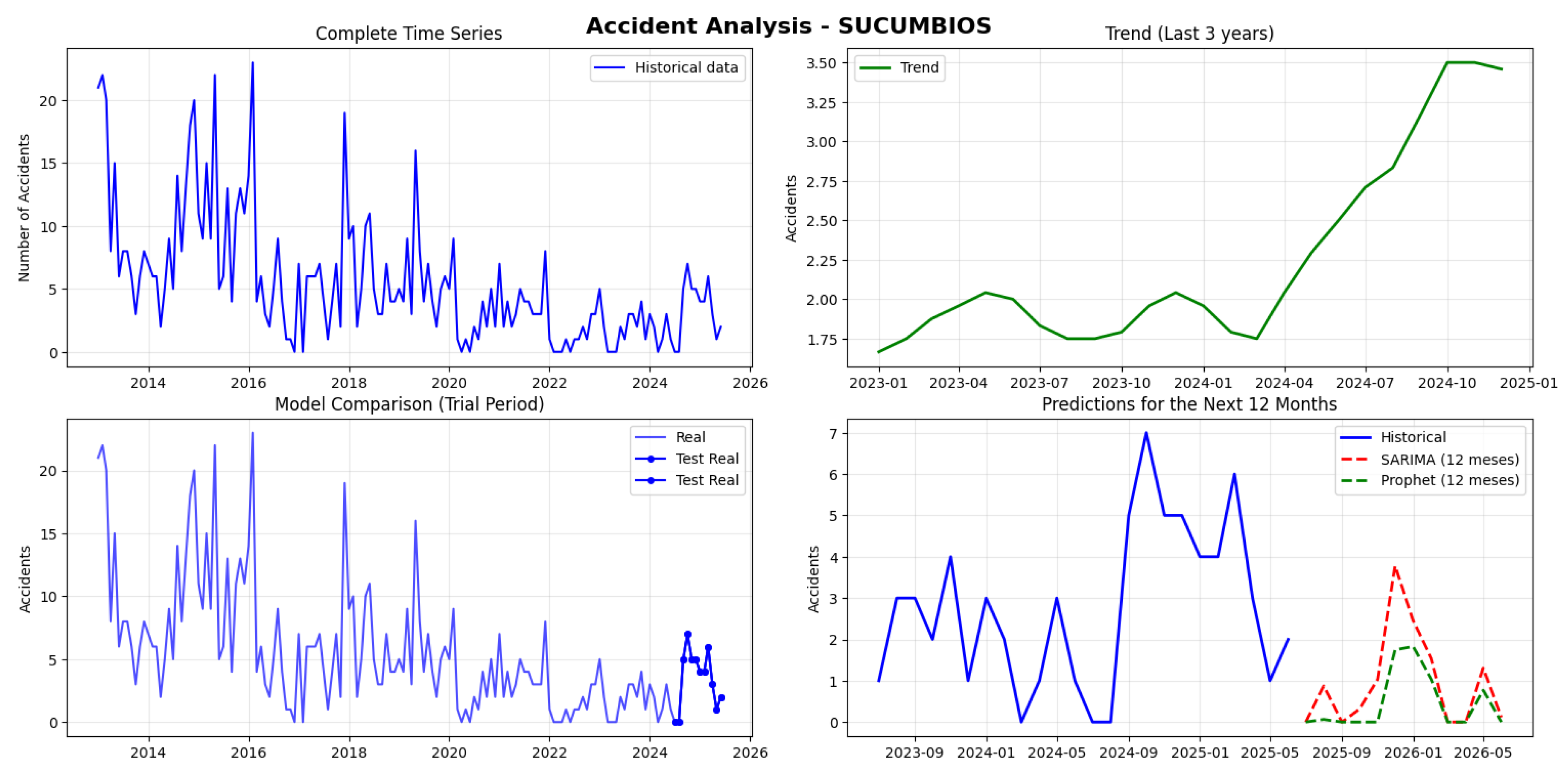

Sucumbíos recorded 828 accidents, the lowest volume analyzed, with a monthly average of 5.5 and high variability between 0 and 23 monthly accidents. The series is not stationary. Both models showed critical failures in MAPE calculation with numerically absurd values (billions of percent), following the error pattern observed in other low-volume provinces. The SARIMA projections range between 0-4 monthly accidents, with 7 of the 12 months projecting 0 accidents and only December 2025 showing a significant value (4 accidents), a trend well below the historical average (see

Figure 25).

Among the analyzed Amazonian provinces, Morona Santiago recorded the highest accident volume (1,553) while Sucumbíos had the lowest (828). Orellana was the only province with a stationary series, where SARIMA achieved the best performance (MAPE 31.86%). In the other non-stationary provinces, Prophet showed an advantage in Morona Santiago (43.36%) and Sucumbíos (533.73%), although the latter presents an extremely high error. Predictive errors vary dramatically, from the acceptable 31.86% in Orellana to critically high values in Pastaza (1703.95%) and Sucumbíos (533.73%), reflecting the challenges of modeling very low-volume series (see

Table 5).

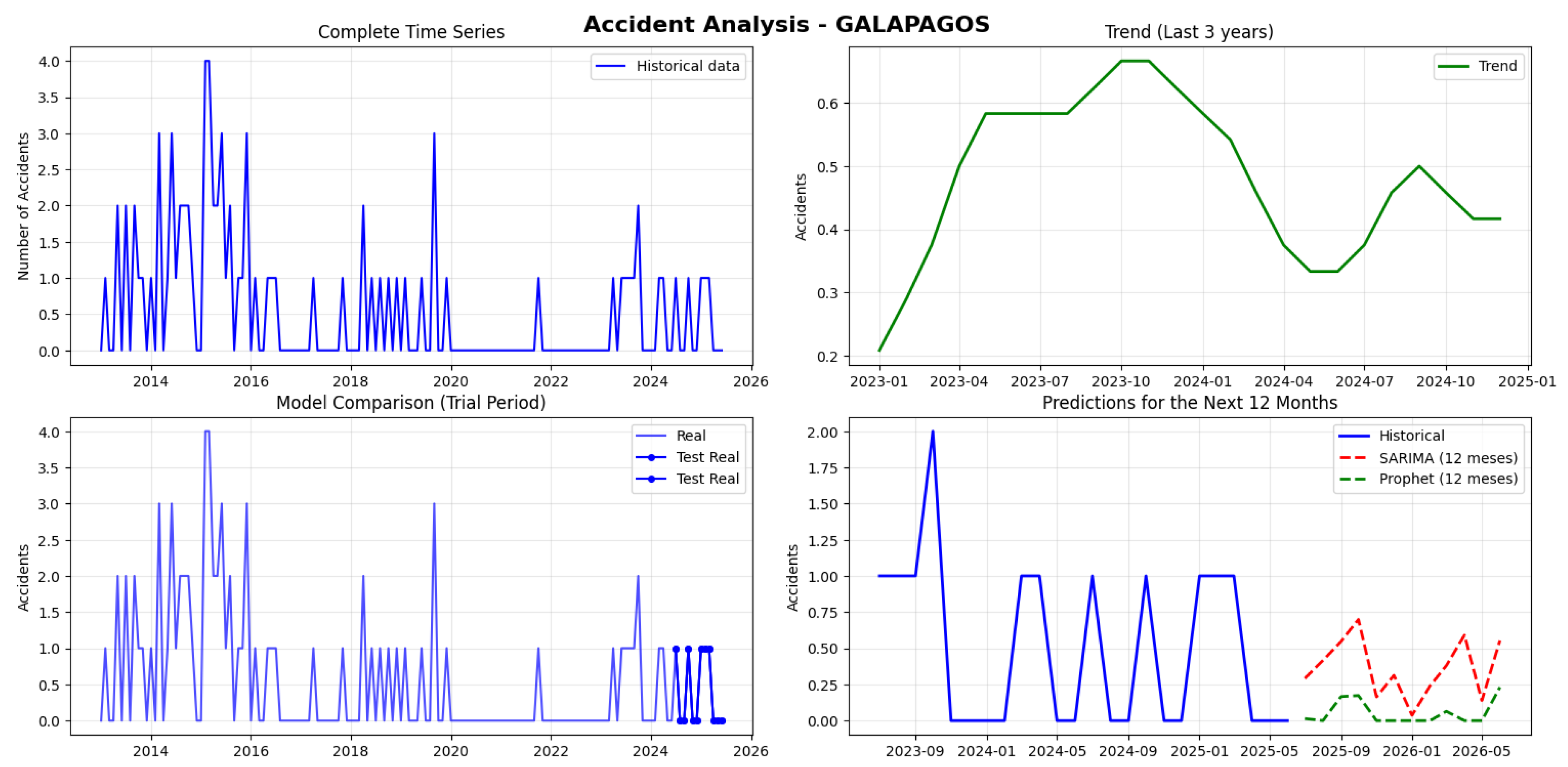

4.4. Insular Region

The Insular Region (Galápagos) has the lowest accident volume in the country, with a monthly average of only 0.5. Its time series is not stationary and the MAPE values are extremely high and unstable, showing numerically absurd figures that confirm a systematic error pattern in provinces with minimal volumes. This MAPE failure appears to be related to the high frequency of zero or near-zero values in the data (see

Figure 26)

However, the RMSE values are very low (0.56-0.62), indicating that the numerical predictions are accurate in scale. The projections of 0-1 monthly accidents are consistent with historical data, showing a random distribution of zeros and ones without a clear seasonal pattern. The projected average of 0.33 accidents per month is slightly lower than the historical average of 0.5 (see

Table 6).

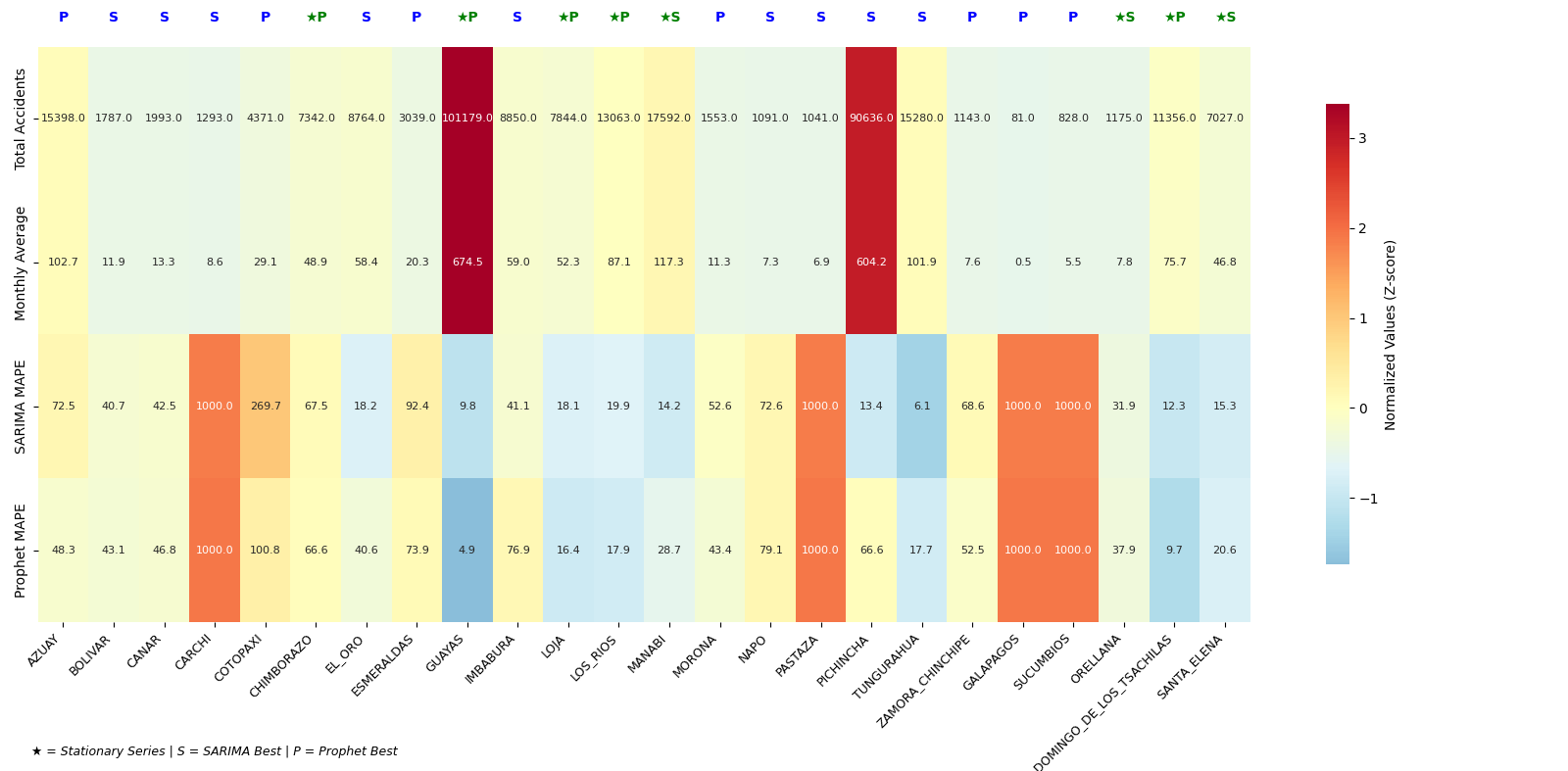

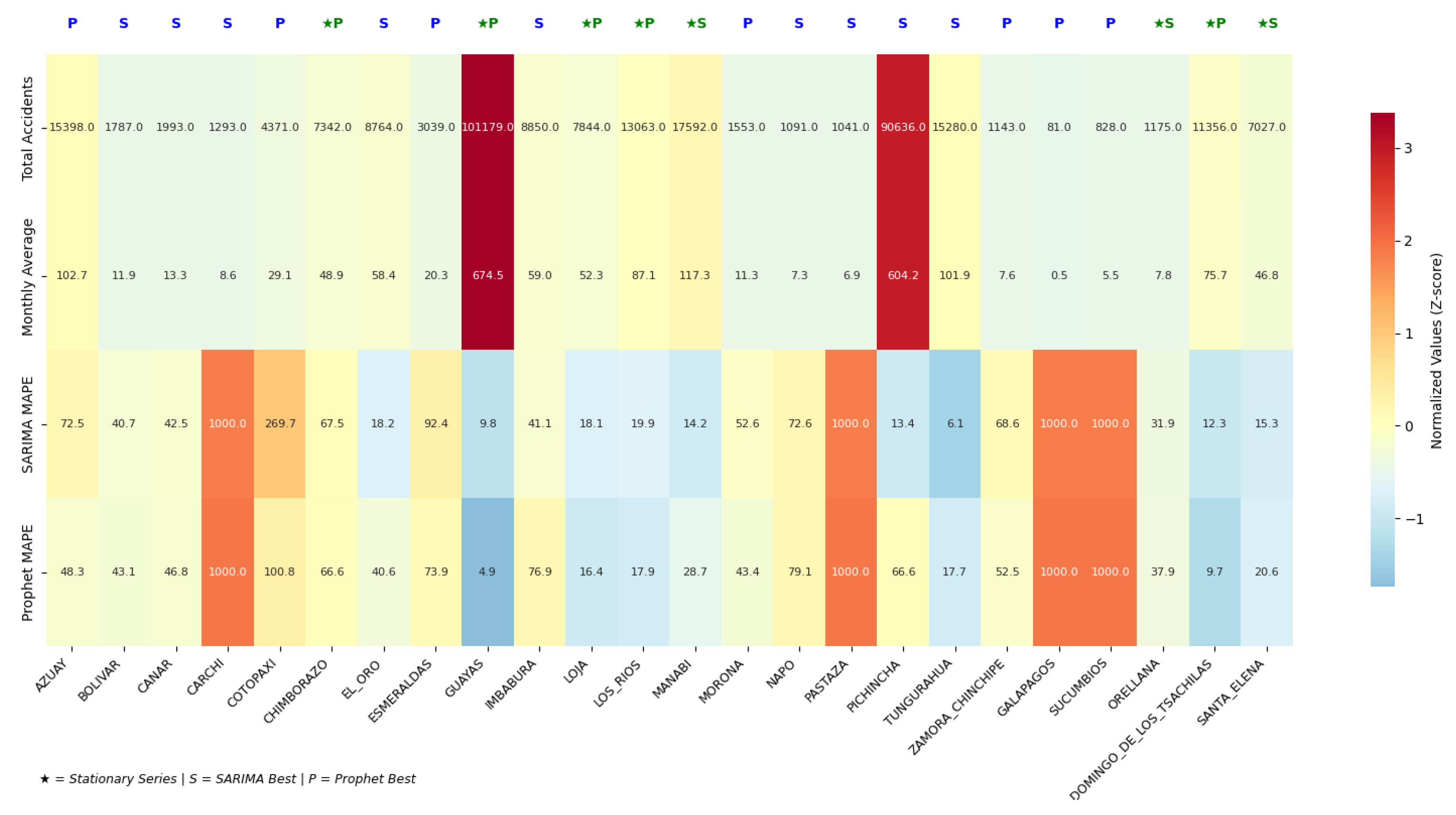

Despite the Prophet model registering the highest individual accuracy (4.91% MAPE in Guayas), the analysis reveals a Global Tie (12 vs. 12) in the number of provinces where each model is superior according to the MAPE.

SARIMA is more effective in the Sierra Region (provinces with Non-Stationary series but with medium-to-high volume, such as Pichincha and Tungurahua). Prophet is more effective in the Coast Region (provinces with high volume and stationary series, such as Guayas and Sto. Domingo de los Tsáchilas).

There is no single general “Best Model” when counting the victories per province; both models are equally competitive, with the selection of the optimal model depending on the intrinsic characteristics (stationarity, volume, volatility) of each province’s time series (see

Table 7)

The accident analysis compared the SARIMA and Prophet models for all 24 provinces, most having 150 monthly records, selecting the best model for each. Guayas has the highest accident volume (101,179 total, 674.5 monthly), and Galápagos the lowest (81 total, 0.5 monthly).The best overall precision was achieved with Prophet in Guayas (

), while SARIMA’s best precision was in Tungurahua (

). Only 7 provinces were classified as stationary time series (including Guayas, Manabí, and Sto. Domingo), while 17 provinces were non-stationary.The model choice was critical: Pichincha strongly favored SARIMA (

MAPE), and Guayas favored Prophet (

MAPE) (

Figure 27).