Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

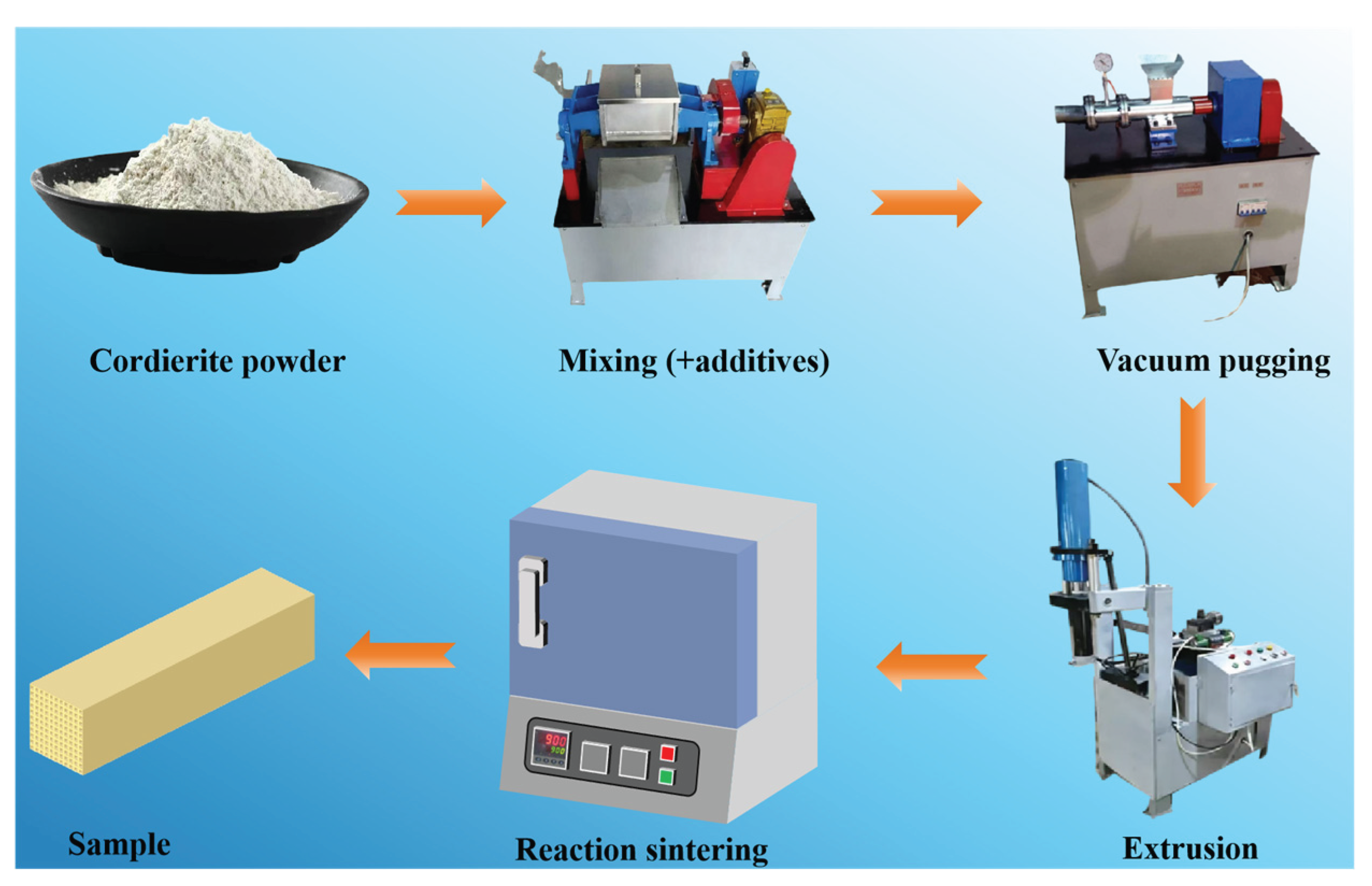

2.2. Preparation of Honeycomb Shaped Cordierite

2.3. Orthogonal Experimental Design (OED)

2.4. Characterization

3. Results

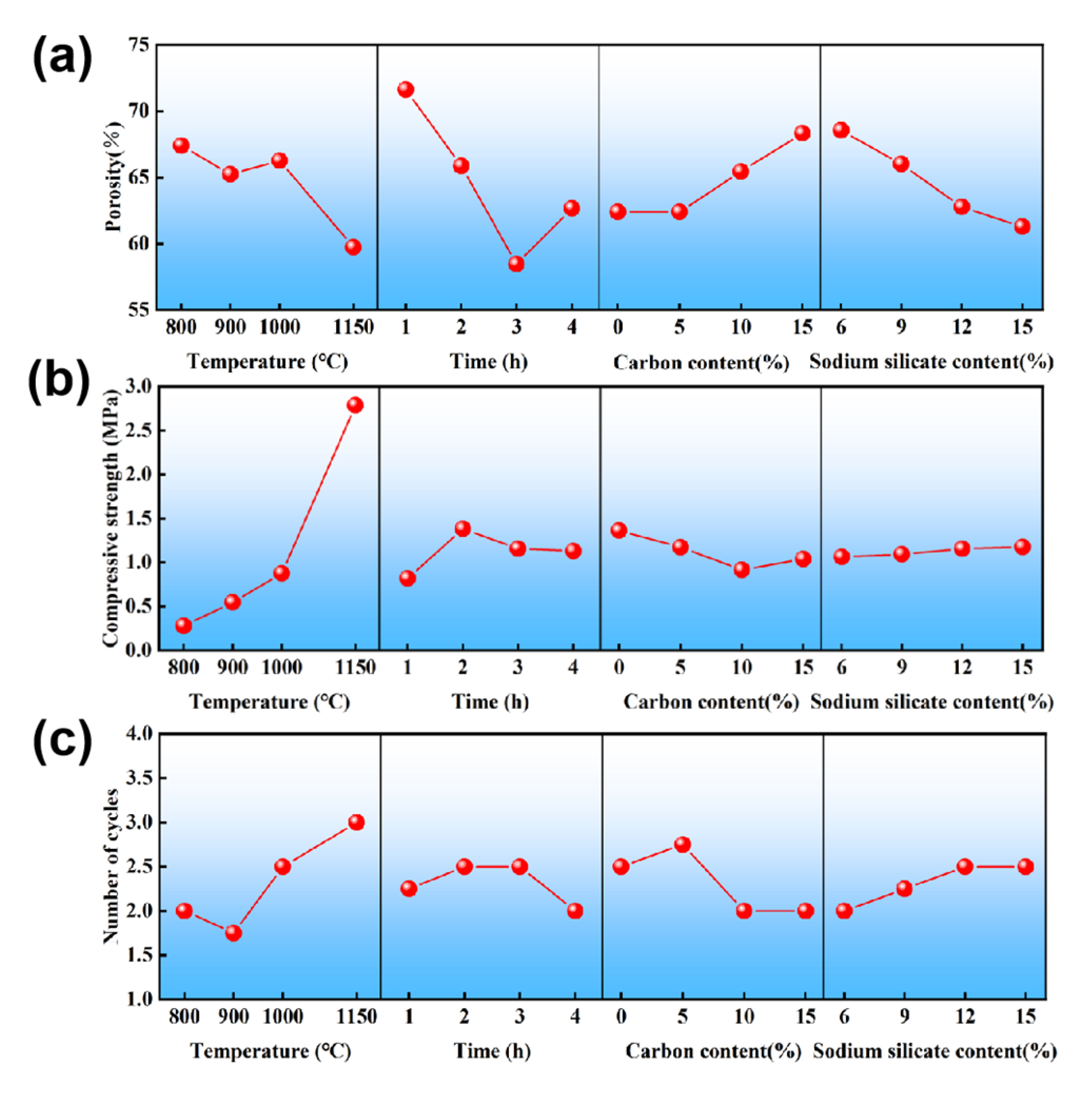

3.1. Orthogonal Test Results

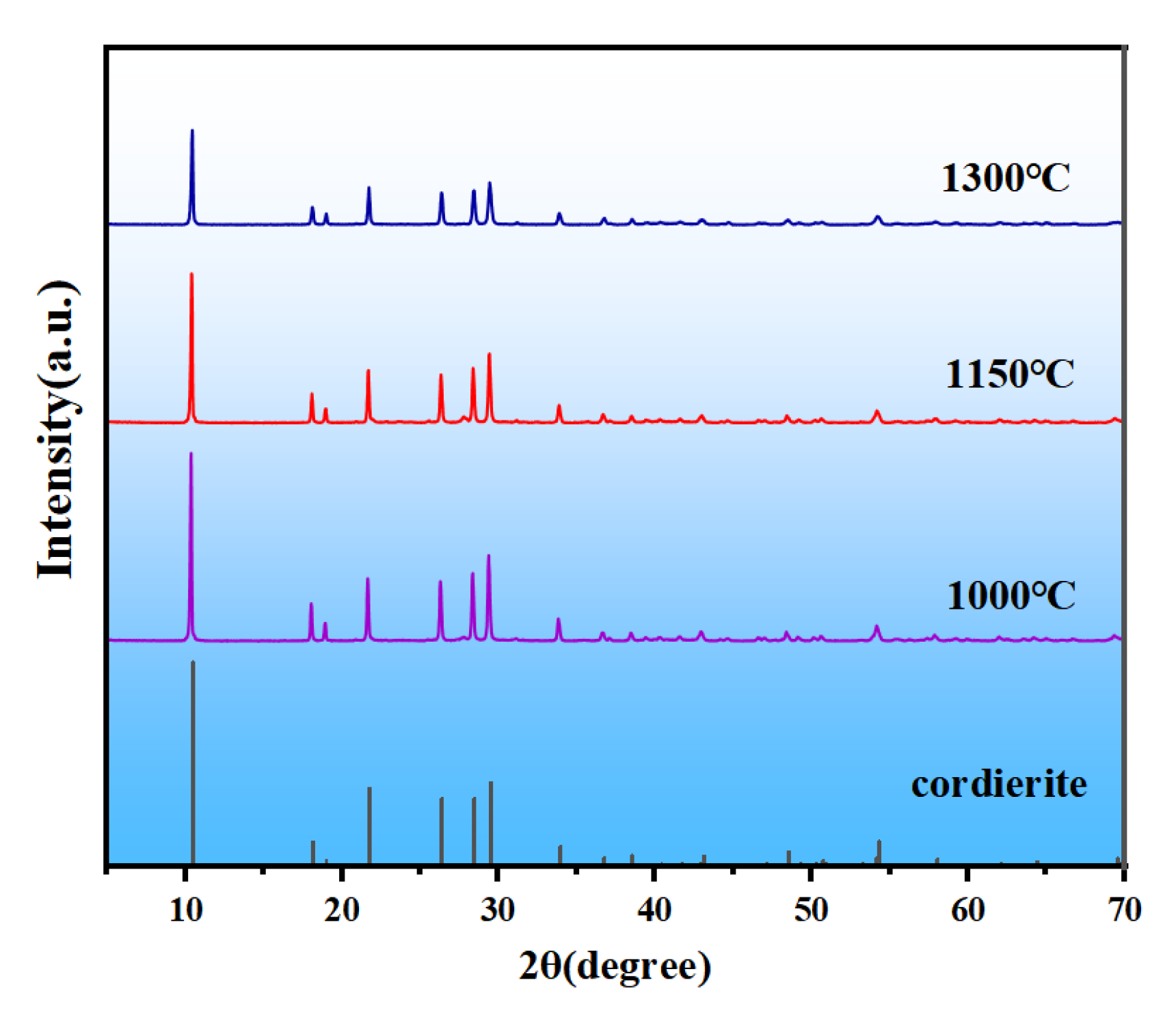

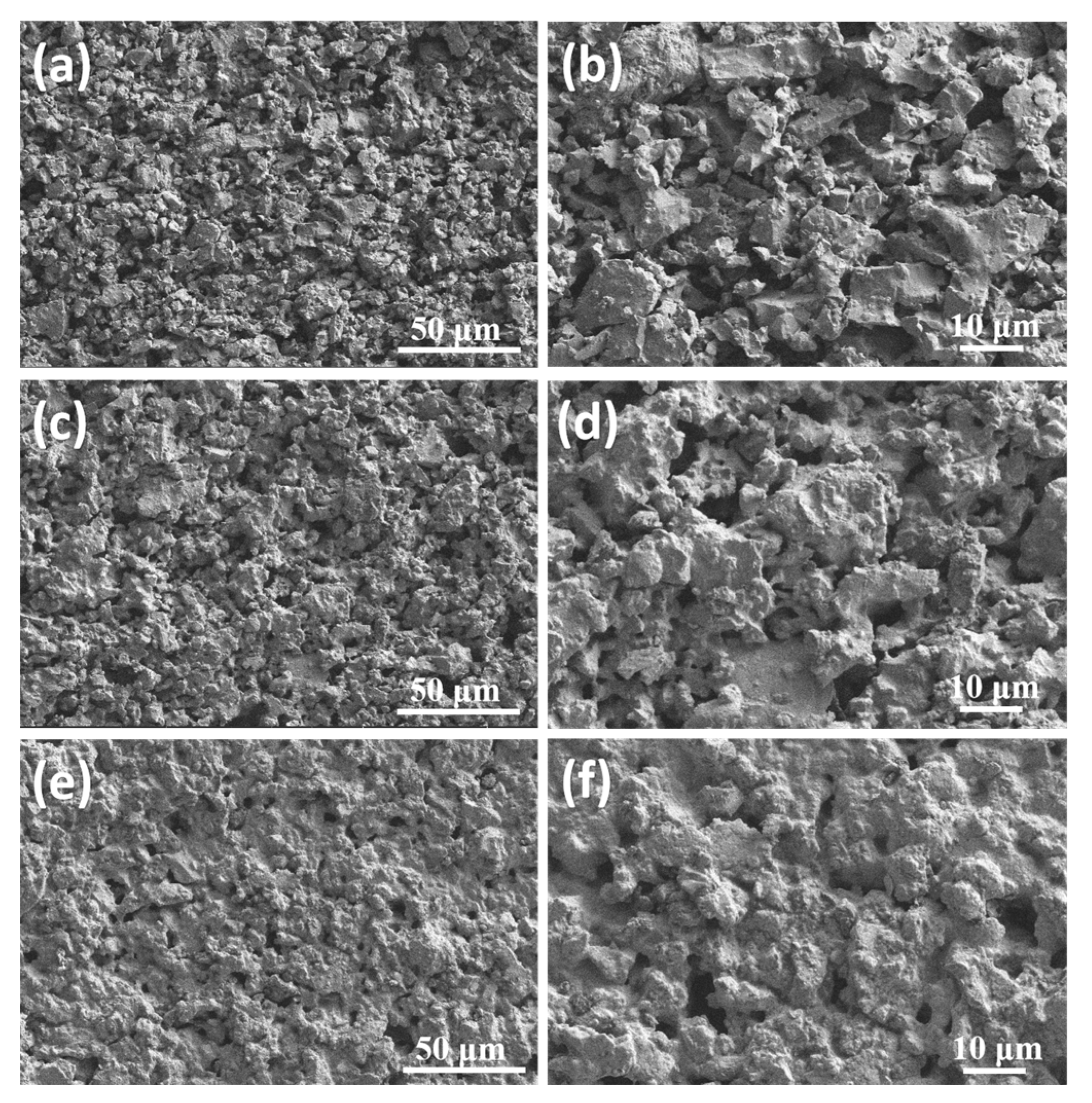

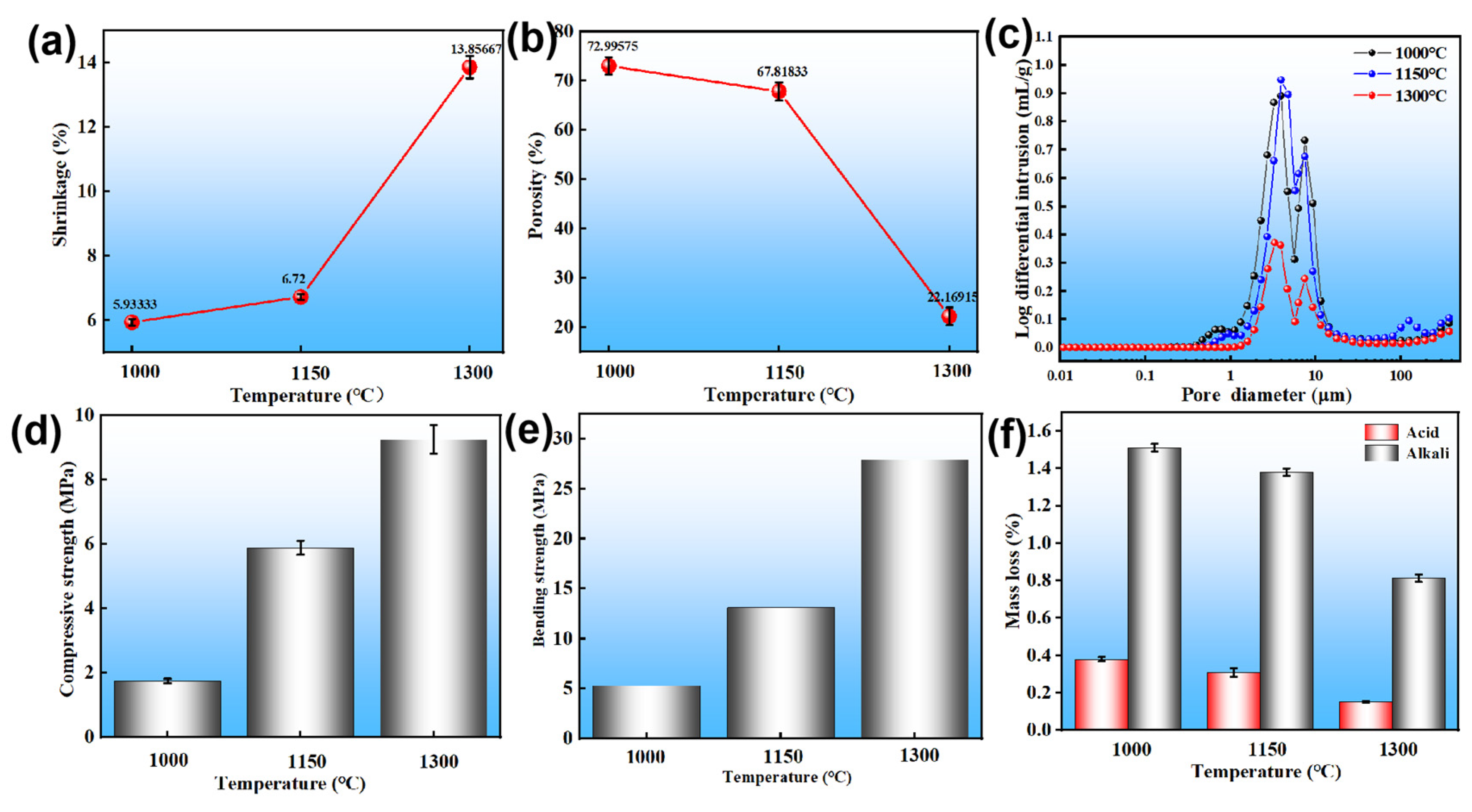

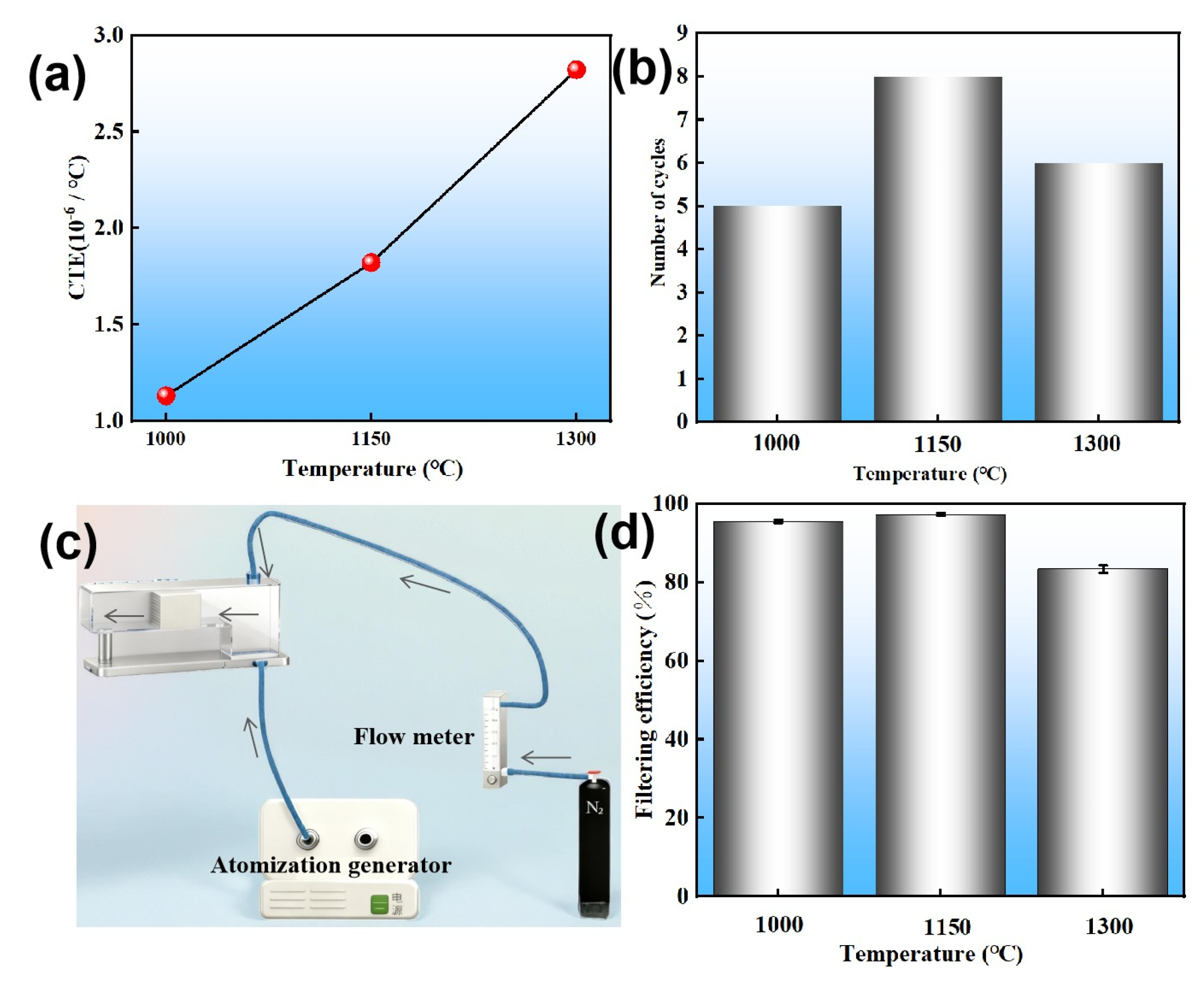

3.2. Effects of Sintering Temperature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khanna, S. , Dewangan, A.K., Yadav, A.K., Ahmad, A. A progressive review on strategies to reduce exhaust emissions from diesel engine: Current trends and future options. Environ. Prog. Sustain. 2025, 44, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. , Gao, S., Yu, D., Zhou, S., Wang, L., Yu, X., Zhao, Z. Research progress on preparation of cerium-based oxide catalysts with specific morphology and their application for purification of diesel engine exhaust. J. Rare Earth. 2024, 42, 1187–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. , Dong, R., Lan, G., Yuan, T., Tan, D. Diesel particulate filter regeneration mechanism of modern automobile engines and methods of reducing PM emissions: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2023, 30, 39338–39376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. , Huang, S., Song, J., Dong, S., Pan, T., Zhang, Y., Wang, K., Liu, Y., Preparation and mechanism study of pin rod SiC reinforced cordierite-based diesel particulate filters. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 117135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z. , Wang, W., Zeng, B., Bao, Z., Hu, Y., Ou, J., Liu, J., An experimental investigation of particulate emission characteristics of catalytic diesel particulate filters during passive regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D. , Wang, L., Liu, X., Zhang, Y., Liang, J., Meng, J., Preparation and properties of cordierite-based multi-phase composite far-infrared emission ceramics by fine-grained tailings. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 29729–29737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, M. , Yang, Y., Ullah, B., Xiao, Y., Tan, D.Q., Exceptionally optimized millimeter-wave properties of cordierite-based materials via innovative processing and predictive analytics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 117206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, A. , Bruno, G., Watkins, T.R., Pandey, A., Lara-Curzio, E., Parish, C.M., Stafford, R.J., The effect of porosity and microcracking on the thermomechanical properties of cordierite. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 4557–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. , Bao, C., Dong, W. and Liu, R., Phase evolution and properties of porous cordierite ceramics prepared by cordierite precursor pastes based on supportless stereolithography. J. Alloy. Compound. 2022, 922, 166295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Wang, S., Meng, Z., Chen, Z., Liu, L., Wang, X., Qian, D. and Xing, Y., Mechanism of cordierite formation obtained by high temperature sintering technique. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 20544–20555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahsh, M.M.S. , Mansour, T.S., Othman, A.G.M., Bakr, I.M. Recycling bagasse and rice hulls ash as a pore-forming agent in the fabrication of cordierite-spinel porous ceramics. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Tec. 2022, 19, 2664–2674. [Google Scholar]

- Elbadawi, M. , Wally, Z.J. and Reaney, I.M. Porous hydroxyapatite-bioactive glass hybrid scaffolds fabricated via ceramic honeycomb extrusion. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 3541–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. , Li, Z., Gao, X., Huang, Y., He, R. Material extrusion 3D printing of large-scale SiC honeycomb metastructure for ultra-broadband and high temperature electromagnetic wave absorption. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 85, 104158. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. , Ma, C., Sun, T., Yu, Y., Wu, Y., Wu, Y., Zang, G., Fu, J., Yu, C., Liu, X., Jiang, B. A novel honeycomb ceramic for gas treatment prepared by microarc oxidation. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 12525–12533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, T. , Tomita, T., Kameshima, Y., Nakajima, A., Okada, K. Preparation and properties of porous alumina ceramics with oriented cylindrical pores produced by an extrusion method. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 26, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhudan, A.I. , Supriadi, S., Whulanza, Y., Saragih, A.S. Additive manufacturing of metallic based on extrusion process: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 66, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. , Cai, X., Zhu, L., Zhang, L., Yang, H. Preparation and properties of SiC honeycomb ceramics by pressureless sintering technology. J. Adv. Ceram. 2014, 3, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. , Zhou, W., Zhou, Z., Sun, N., Liu, Y., Liu, W., Yang, X., Pui, D.Y. Microwave drying coupled with convective air and steam for efficient dehydration of extruded zeolite honeycomb monolith. Ceram. Int., 2024, 50, 43674–43682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y. , Li, A., Wu, D., Li, J., Guo, J. Low-resistance optimization and secondary flow analysis of elbows via a combination of orthogonal experiment design and simple comparison design. Build. Environ. 2023, 236, 110263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B. , Zhou, X., Gu, Q., Ding, J., Zhang, C., Zhu, H., Wang, Z. Orthogonal design of bioinspired butterfly-wing microstructures for enhanced anti-reflection performance. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. , Xiang, Y., Feng, H., Cui, Y., Liu, X., Chang, X., Guo, J. and Tu, P. Optimization of 3D printing parameters for alumina ceramic based on the orthogonal test. ACS omega 2024, 9, 16734–16742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, P. , Zhao, Q., Guo, S., Xue, W., Liu, H., Chao, Z., Jiang, L. and Wu, G. Optimisation of the spark plasma sintering process for high volume fraction SiCp/Al composites by orthogonal experimental design. Ceram. Int., 2021, 47, 3816–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. , Zhu, D., Zhang, X., Liang, J. Effect of spontaneous polarization of tourmaline on the grain growth behavior of 3YSZ powder. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 4542–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. , Xie, Y., Ji, L., Zhong, Z., Xing, W. Low-temperature sintering of a porous SiC ceramic filter using water glass and zirconia as sintering aids. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 26125–26133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürel, M.Ş. and Topateş, G.Ü.L.S.Ü.M. Role of liquidus temperature and composition on the densification and properties of cordierite. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 34016–34024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. , Hu, C., Pi, C., Xu, X. and Xiang, W. Preparation and corrosion resistance of cordierite-spodumene composite ceramics using zircon as a modifying agent. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 19590–19596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlikov, V.M. , Garmash, E.P., Yurchenko, V.A., Pleskach, I.V., Oleinik, G.S., Grigor’ev, O.M. Mechanochemical activation of kaolin, pyrophyllite, and talcum and its effect on the synthesis of cordierite and properties of cordierite ceramics. Powder Metall. Met. Ceram. 2011, 49, 564–574. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, C.S. , Çakır, C.A., Altundağ, H., Toplan, N., Toplan, H.Ö. The effects of mechanical activation on corrosion resistance of cordierite ceramics. Turk. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 5, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.W. , Son, M.A., Park, S.J., Kim, J.S., Kim, S.H. Effect of sintering atmosphere on the crystallizations, porosity, and thermal expansion coefficient of cordierite honeycomb ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 19526–19537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, O. , Zaichuk, A., Amelina, A. Low-temperature cordierite ceramics with porous structure for thermal shock resistance products. Open Ceramics 2024, 17, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Factor level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sintering temperature (℃) | Holding time (h) | Pore-forming agent content (wt.%) | Sintering aid content (wt.%) | |

| A | B | C | D | |

| 1 | 800 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | 900 | 2 | 5 | 9 |

| 3 | 1000 | 3 | 10 | 12 |

| 4 | 1150 | 4 | 15 | 15 |

| No. | Factors | Porosity (%) | Compressive strength (MPa) | Thermal shock cycles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||

| 1 | 800 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 76.46 | 0.20 | 2 |

| 2 | 900 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 69.45 | 0.25 | 2 |

| 3 | 1000 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 71.29 | 0.45 | 2 |

| 4 | 1150 | 1 | 15 | 15 | 69.27 | 2.38 | 3 |

| 5 | 800 | 2 | 10 | 9 | 72.98 | 0.23 | 2 |

| 6 | 900 | 2 | 15 | 6 | 73.22 | 0.72 | 1 |

| 7 | 1000 | 2 | 0 | 15 | 60.01 | 1.42 | 3 |

| 8 | 1150 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 57.24 | 3.17 | 4 |

| 9 | 800 | 3 | 15 | 12 | 61.20 | 0.26 | 2 |

| 10 | 900 | 3 | 10 | 15 | 56.91 | 0.46 | 2 |

| 11 | 1000 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 63.92 | 0.82 | 3 |

| 12 | 1150 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 51.79 | 3.09 | 3 |

| 13 | 800 | 4 | 5 | 15 | 58.94 | 0.45 | 2 |

| 14 | 900 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 61.34 | 0.75 | 2 |

| 15 | 1000 | 4 | 15 | 9 | 69.83 | 0.81 | 2 |

| 16 | 1150 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 60.58 | 2.52 | 2 |

| Parameter | A | B | C | D | |

| Porosity (%) | K1 | 67.40 | 71.62 | 62.40 | 68.55 |

| K2 | 65.23 | 65.86 | 62.39 | 66.01 | |

| K3 | 66.26 | 58.46 | 65.44 | 62.77 | |

| K4 | 59.72 | 62.67 | 68.38 | 61.28 | |

| R | 7.68 | 13.16 | 5.99 | 7.27 | |

| Compressive strength (MPa) | K1 | 0.28 | 0.82 | 1.36 | 1.06 |

| K2 | 0.54 | 1.38 | 1.17 | 1.09 | |

| K3 | 0.88 | 1.16 | 0.92 | 1.16 | |

| K4 | 2.70 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 1.18 | |

| R | 2.42 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.12 | |

| Thermal shock cycles | K1 | 2 | 2.25 | 2.5 | 2 |

| K2 | 1.75 | 2.5 | 2.75 | 2.25 | |

| K3 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2 | 2.5 | |

| K4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2.5 | |

| R | 1.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).