Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Sample

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Comparison

2.3. Measurement Procedures and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Statistical Formulations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

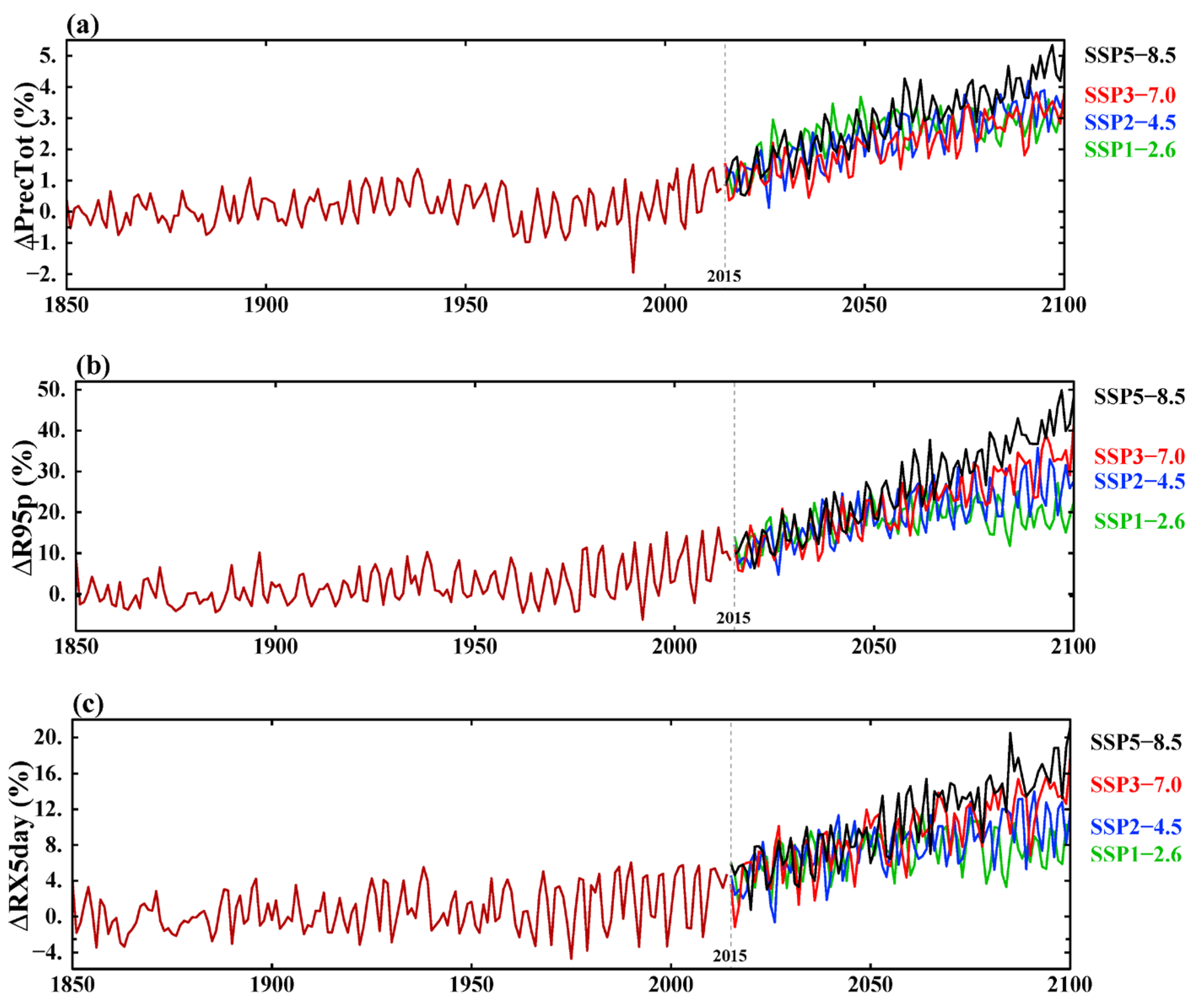

3.1. Overall Reproduction of Precipitation Extremes

3.2. Sensitivity to Temporal Aggregation

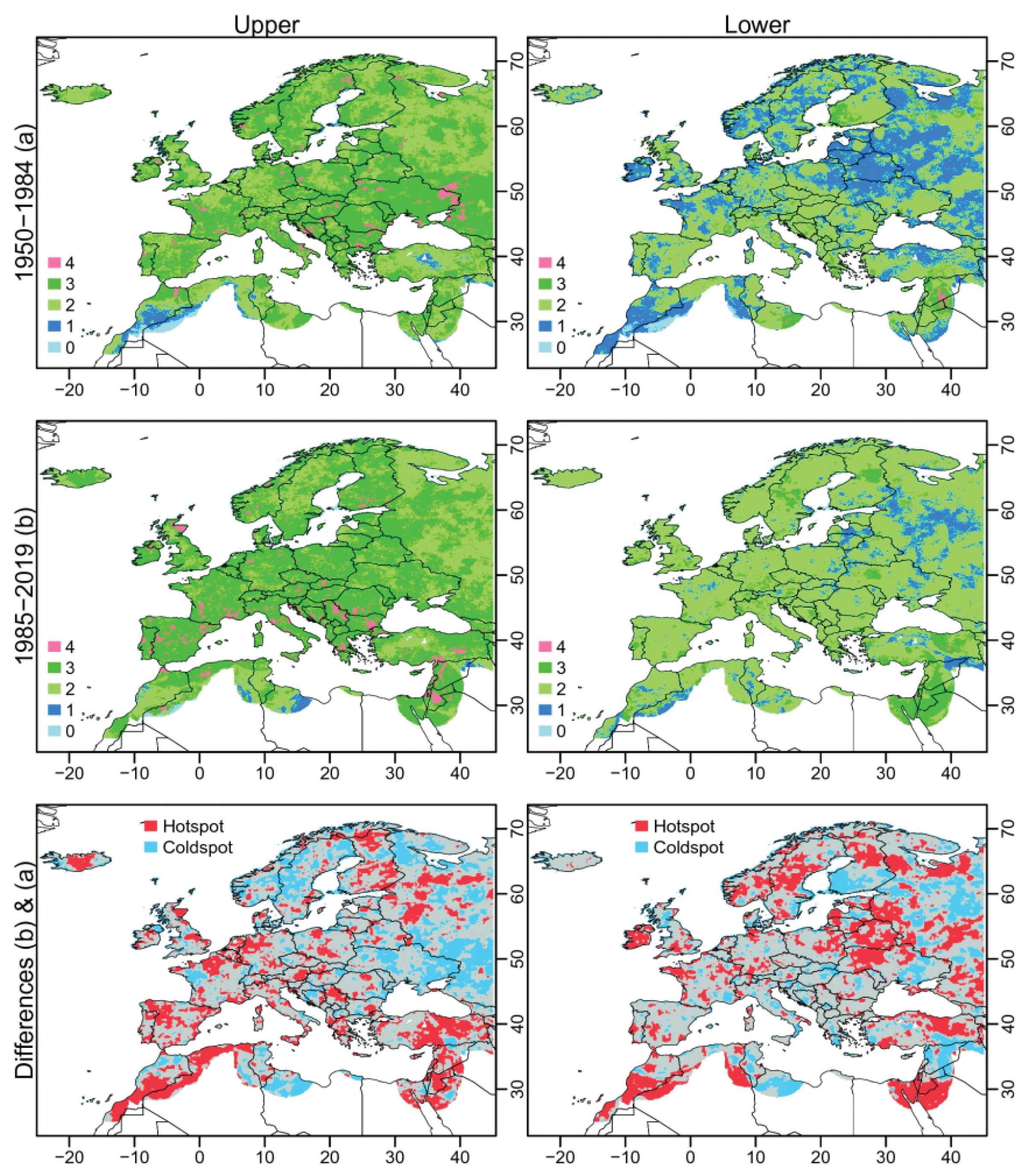

3.3. Regional Patterns of Bias

3.4. Broader Implications and Limitations

4. Conclusion

References

- Kron, W., Löw, P., & Kundzewicz, Z. W. (2019). Changes in risk of extreme weather events in Europe. Environmental Science & Policy, 100, 74-83. [CrossRef]

- Nissen, K. M., & Ulbrich, U. (2017). Increasing frequencies and changing characteristics of heavy precipitation events threatening infrastructure in Europe under climate change. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 17(7), 1177-1190. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE.

- Wright, D. B. (2018). Rainfall information for global flood modeling. Global flood hazard: Applications in modeling, mapping, and forecasting, 17-42. [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, J., Mehra, P., Yang, J., & Linford, E. (2025). Privacy Preserving Risk Modeling Across Financial Institutions via Federated Learning with Adaptive Optimization. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence Research, 2(1), 35-43. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, O. (2022). Advances and challenges in climate modeling. Climatic Change, 170(1), 18. [CrossRef]

- LINCOLN, W. S. (2014). Analysis of the 15 June 2013 Isolated Extreme Rainfall Event in Springfield, Missouri. Journal of Operational Meteorology, 2(19).

- Müller, S. K., Caillaud, C., Chan, S., de Vries, H., Bastin, S., Berthou, S., ... & Warrach-Sagi, K. (2023). Evaluation of Alpine-Mediterranean precipitation events in convection-permitting regional climate models using a set of tracking algorithms. Climate Dynamics, 61(1), 939-957. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., DeFlorio, M. J., Sengupta, A., Wang, J., Castellano, C. M., Gershunov, A., ... & Ralph, F. M. (2024). Seasonality and climate modes influence the temporal clustering of unique atmospheric rivers in the Western US. Communications Earth & Environment, 5(1), 734. [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Picher, P., Argüeso, D., Brisson, E., Tramblay, Y., Berg, P., Lemonsu, A., ... & Caillaud, C. (2021). Convection-permitting modeling with regional climate models: Latest developments and next steps. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 12(6), e731. [CrossRef]

- Ehmele, F., Kautz, L. A., Feldmann, H., & Pinto, J. G. (2020). Long-term variance of heavy precipitation across central Europe using a large ensemble of regional climate model simulations. Earth System Dynamics, 11(2), 469-490. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, S., Kotlarski, S., Soares, P. M., Cardoso, R. M., Jaczewski, A., Gutiérrez, J. M., & Maraun, D. (2019). Uncertainty in gridded precipitation products: Influence of station density, interpolation method and grid resolution. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Chakrapani, V. (2023). Environmental Factors Controlling the Electronic Properties and Oxidative Activities of Birnessite Minerals. ACS Earth and Space Chemistry, 7(4), 774-787. [CrossRef]

- Prein, A. F., & Gobiet, A. (2017). Impacts of uncertainties in European gridded precipitation observations on regional climate analysis. International Journal of Climatology, 37(1), 305-327. [CrossRef]

- Bissi, F. (2024). Heat wave and heat stress space-time pattern analysis in Lombardy using climate reanalysis data.

- Barlow, M., Gutowski Jr, W. J., Gyakum, J. R., Katz, R. W., Lim, Y. K., Schumacher, R. S., ... & Min, S. K. (2019). North American extreme precipitation events and related large-scale meteorological patterns: a review of statistical methods, dynamics, modeling, and trends. Climate Dynamics, 53(11), 6835-6875. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K., Lu, Y., Hou, S., Liu, K., Du, Y., Huang, M., ... & Sun, X. (2024). Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nature Communications, 15(1), 8223. [CrossRef]

- Morbidelli, R., Saltalippi, C., Flammini, A., Corradini, C., Wilkinson, S. M., & Fowler, H. J. (2018). Influence of temporal data aggregation on trend estimation for intense rainfall. Advances in Water Resources, 122, 304-316. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Shen, M., Wang, L., Wen, Y., & Cai, H. (2024). Comparative Modulation of Immune Responses and Inflammation by n-6 and n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Oxylipin-Mediated Pathways. [CrossRef]

- Colucci, R. R., Žebre, M., Torma, C. Z., Glasser, N. F., Maset, E., Del Gobbo, C., & Pillon, S. (2021). Recent increases in winter snowfall provide resilience to very small glaciers in the Julian Alps, Europe. Atmosphere, 12(2), 263. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).