Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Why AI? Why genetics?

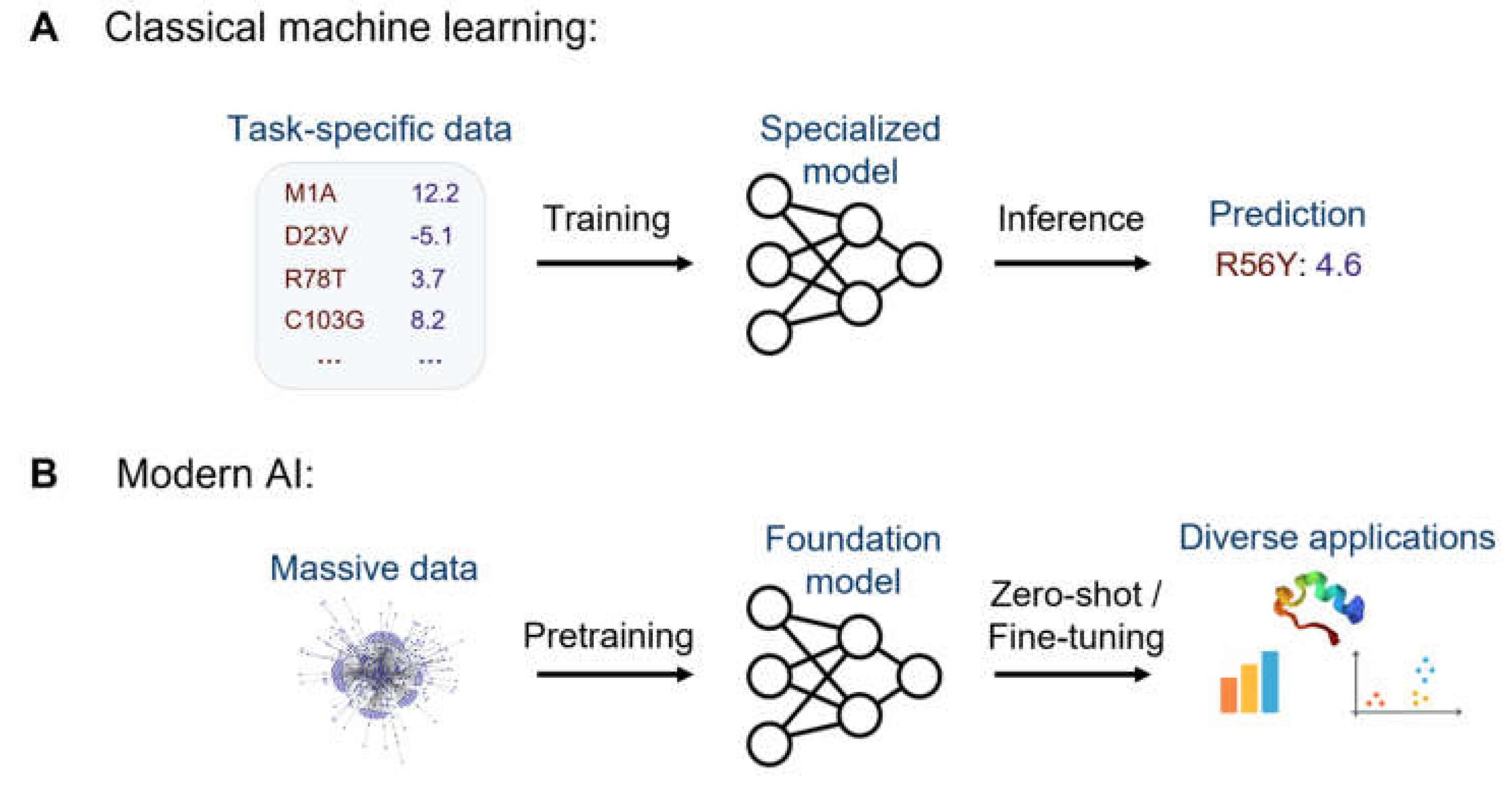

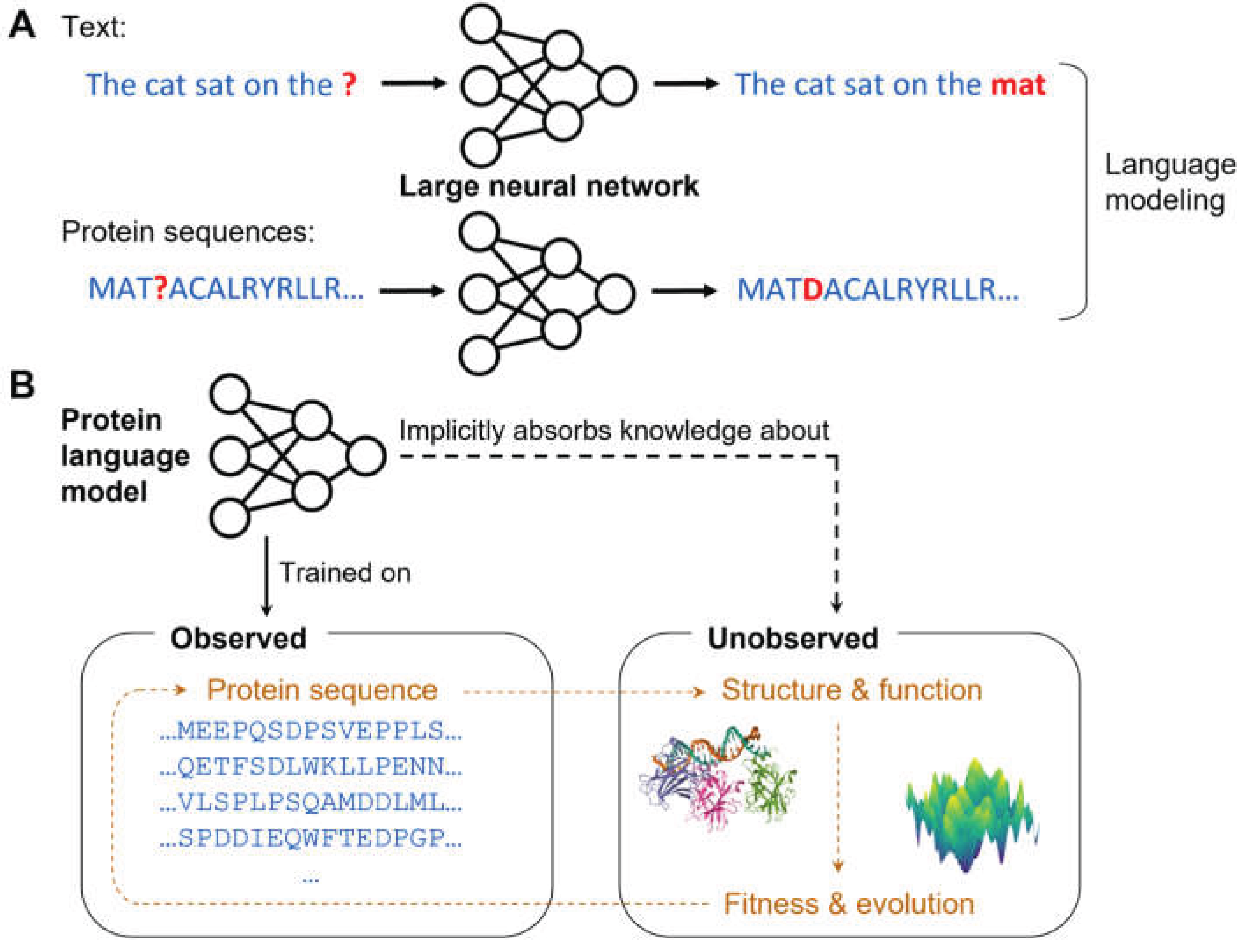

2. Terminology & AI Trends

Covered topics

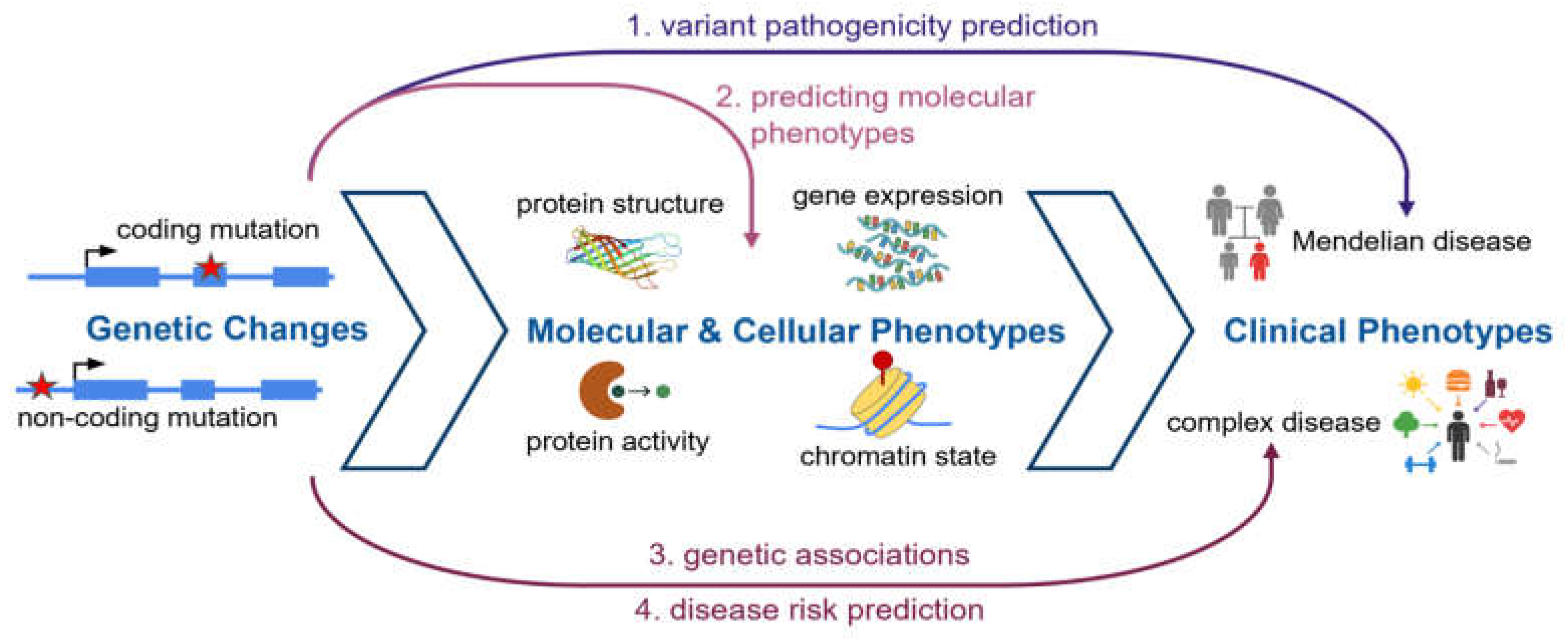

3. Identifying Disease-Causing Protein Mutations

3.1. The pursuit of mechanism: predicting genetic effects at the molecular level

3.2. Predicting regulatory effects

4. Universal Genomic Models

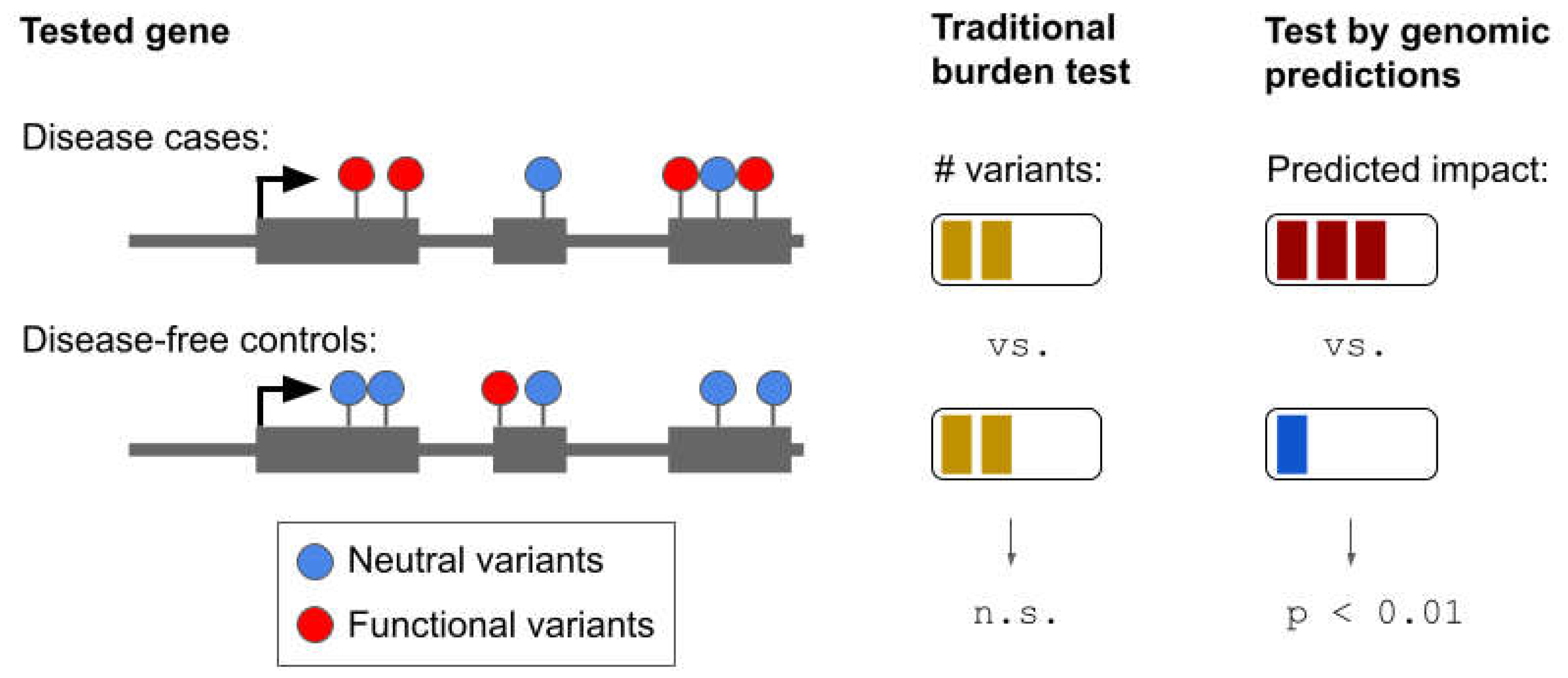

5. Informing Genetic Association Studies with Genomic Predictions

6. Disease Risk Estimation

7. Challenges for Real-World Impact

Acknowledgements

References

- DeepMind. AlphaFold: A Solution to a 50-Year-Old Grand Challenge in Biology [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://deepmind.com/blog/article/alphafold-a-solution-to-a-50-year-old-grand-challenge-in-biology.

- Outreach, NP. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2024 [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/2024/press-release/.

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature. 2021, 596, 583–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, M.A.; Markhieva, K.A.; Novikova, M.S.; Petrov, D.S.; Vorobyev, I.S.; Maksimova, E.S.; et al. Using AlphaFold to predict the impact of single mutations on protein stability and function. Plos One. 2023, 18, e0282689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science. 2023, 379, 1123–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rives, A.; Meier, J.; Sercu, T.; Goyal, S.; Lin, Z.; Liu, J.; et al. Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021, 118, e2016239118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brixi G, Durrant MG, Ku J, Poli M, Brockman G, Chang D, et al. Genome modeling and design across all domains of life with Evo 2. bioRxiv. 2025;2025–02.

- Baek, M.; DiMaio, F.; Anishchenko, I.; Dauparas, J.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Lee, G.R.; et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science. 2021, 373, 871–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Novati, G.; Pan, J.; Bycroft, C.; Žemgulytė, A.; Applebaum, T.; et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science. 2023, 381, eadg7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentzsch, P.; Schubach, M.; Shendure, J.; Kircher, M. CADD-Splice—improving genome-wide variant effect prediction using deep learning-derived splice scores. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentzsch, P.; Witten, D.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J.; Kircher, M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D886–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubach, M.; Maass, T.; Nazaretyan, L.; Röner, S.; Kircher, M. CADD v1.7: using protein language models, regulatory CNNs and other nucleotide-level scores to improve genome-wide variant predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1143–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandes, N.; Goldman, G.; Wang, C.H.; Ye, C.J.; Ntranos, V. Genome-wide prediction of disease variant effects with a deep protein language model. Nat Genet. 2023, 55, 1512–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, J.; Notin, P.; Dias, M.; Gomez, A.; Min, J.K.; Brock, K.; et al. Disease variant prediction with deep generative models of evolutionary data. Nature. 2021, 599, 91–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, M.F.; Shihab, H.A.; Mort, M.; Cooper, D.N.; Gaunt, T.R.; Campbell, C. FATHMM-XF: accurate prediction of pathogenic point mutations via extended features. Bioinformatics. 2018, 34, 511–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shihab, H.A.; Rogers, M.F.; Gough, J.; Mort, M.; Cooper, D.N.; Day, I.N.; et al. An integrative approach to predicting the functional effects of non-coding and coding sequence variation. Bioinformatics. 2015, 31, 1536–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benegas G, Albors C, Aw AJ, Ye C, Song YS. A DNA language model based on multispecies alignment predicts the effects of genome-wide variants. Nat Biotechnol. 2025;1–6.

- Albors C, Li JC, Benegas G, Ye C, Song YS. A Phylogenetic Approach to Genomic Language Modeling. ArXiv Prepr ArXiv250303773. 2025.

- Pollard, K.S.; Hubisz, M.J.; Rosenbloom, K.R.; Siepel, A. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 110–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adzhubei, I.; Jordan, D.M.; Sunyaev, S.R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2013, 76, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao H, Hamp T, Ede J, Schraiber JG, McRae J, Singer-Berk M, et al. The landscape of tolerated genetic variation in humans and primates. Science. 2023 ;380(6648):eabn8153. 2 June.

- Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, Middha S, McDonnell SK, Baheti S, et al. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(4):877–85.

- Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001 May;11(5):863–74.

- Avsec Ž, Latysheva N, Cheng J, Novati G, Taylor KR, Ward T, et al. AlphaGenome: advancing regulatory variant effect prediction with a unified DNA sequence model. bioRxiv. 2025;2025–06.

- Sasse A, Ng B, Spiro AE, Tasaki S, Bennett DA, Gaiteri C, et al. Benchmarking of deep neural networks for predicting personal gene expression from DNA sequence highlights shortcomings. Nat Genet. 2023 Dec 1;55(12):2060–4.

- Zhou J, Troyanskaya OG. Predicting effects of noncoding variants with deep learning–based sequence model. Nat Methods. 2015 Oct 1;12(10):931–4.

- Avsec Ž, Agarwal V, Visentin D, Ledsam JR, Grabska-Barwinska A, Taylor KR, et al. Effective gene expression prediction from sequence by integrating long-range interactions. Nat Methods. 2021 Oct 1;18(10):1196–203.

- Zhou J, Theesfeld CL, Yao K, Chen KM, Wong AK, Troyanskaya OG. Deep learning sequence-based ab initio prediction of variant effects on expression and disease risk. Nat Genet. 2018 Aug 1;50(8):1171–9.

- Gamazon ER, Wheeler HE, Shah KP, Mozaffari SV, Aquino-Michaels K, Carroll RJ, et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat Genet. 2015 Sept 1;47(9):1091–8.

- Jaganathan K, Panagiotopoulou SK, McRae JF, Darbandi SF, Knowles D, Li YI, et al. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell. 2019;176(3):535–48.

- Fabiha T, Evergreen I, Kundu S, Pampari A, Abramov S, Boytsov A, et al. A consensus variant-to-function score to functionally prioritize variants for disease. bioRxiv. 2024;2024–11.

- Ritchie GRS, Dunham I, Zeggini E, Flicek P. Functional annotation of noncoding sequence variants. Nat Methods. 2014 Mar 1;11(3):294–6.

- Schipper M, de Leeuw CA, Maciel BAPC, Wightman DP, Hubers N, Boomsma DI, et al. Prioritizing effector genes at trait-associated loci using multimodal evidence. Nat Genet. 2025 Feb 1;57(2):323–33.

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015 ;17(5):405–23. 1 May.

- Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown G, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D862–8.

- Chong JX, Buckingham KJ, Jhangiani SN, Boehm C, Sobreira N, Smith JD, et al. The genetic basis of Mendelian phenotypes: discoveries, challenges, and opportunities. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(2):199–215.

- Retterer K, Juusola J, Cho MT, Vitazka P, Millan F, Gibellini F, et al. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet Med. 2016;18(7):696–704.

- Liu X, Li C, Mou C, Dong Y, Tu Y. dbNSFP v4: a comprehensive database of transcript-specific functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Genome Med. 2020 Dec 2;12(1):103.

- Ofer D, Brandes N, Linial M. The language of proteins: NLP, machine learning & protein sequences. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:1750–8.

- Brandes N, Ofer D, Peleg Y, Rappoport N, Linial M. ProteinBERT: a universal deep-learning model of protein sequence and function. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(8):2102–10.

- Elnaggar A, Heinzinger M, Dallago C, Rehawi G, Wang Y, Jones L, et al. Prottrans: Toward understanding the language of life through self-supervised learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(10):7112–27.

- Hayes T, Rao R, Akin H, Sofroniew NJ, Oktay D, Lin Z, et al. Simulating 500 million years of evolution with a language model. Science. 2025;eads0018.

- Meier J, Rao R, Verkuil R, Liu J, Sercu T, Rives A. Language models enable zero-shot prediction of the effects of mutations on protein function. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:29287–303.

- Weinstein E, Amin A, Frazer J, Marks D. Non-identifiability and the blessings of misspecification in models of molecular fitness. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2022;35:5484–97.

- Hou C, Liu D, Zafar A, Shen Y. Understanding Protein Language Model Scaling on Mutation Effect Prediction. bioRxiv. 2025;2025–04.

- Pugh CW, Nuñez-Valencia PG, Dias M, Frazer J. From Likelihood to Fitness: Improving Variant Effect Prediction in Protein and Genome Language Models. bioRxiv. 2025;2025–05.

- Lu B, Liu X, Lin PY, Brandes N. Genomic heterogeneity inflates the performance of variant pathogenicity predictions. bioRxiv. 2025;2025–09.

- Wilcox EH, Sarmady M, Wulf B, Wright MW, Rehm HL, Biesecker LG, et al. Evaluating the impact of in silico predictors on clinical variant classification. Genet Med. 2022;24(4):924–30.

- Bergquist T, Stenton SL, Nadeau EA, Byrne AB, Greenblatt MS, Harrison SM, et al. Calibration of additional computational tools expands ClinGen recommendation options for variant classification with PP3/BP4 criteria. bioRxiv. 2024.

- Tavtigian SV, Greenblatt MS, Harrison SM, Nussbaum RL, Prabhu SA, Boucher KM, et al. Modeling the ACMG/AMP variant classification guidelines as a Bayesian classification framework. Genet Med. 2018;20(9):1054–60.

- Lin PY, Brandes N. P-KNN: Maximizing variant classification evidence through joint calibration of multiple pathogenicity prediction tools. bioRxiv. 2025.

- Gerasimavicius L, Livesey BJ, Marsh JA. Loss-of-function, gain-of-function and dominant-negative mutations have profoundly different effects on protein structure. Nat Commun. 2022 ;13(1):3895. 6 July.

- Fadini A, Li M, McCoy AJ, Terwilliger TC, Read RJ, Hekstra D, et al. AlphaFold as a Prior: Experimental Structure Determination Conditioned on a Pretrained Neural Network. bioRxiv. 2025;2025–02.

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235–42.

- Terwilliger TC, Liebschner D, Croll TI, Williams CJ, McCoy AJ, Poon BK, et al. AlphaFold predictions are valuable hypotheses and accelerate but do not replace experimental structure determination. Nat Methods. 2024;21(1):110–6.

- Chakravarty D, Lee M, Porter LL. Proteins with alternative folds reveal blind spots in AlphaFold-based protein structure prediction. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2025;90:102973.

- Esposito D, Weile J, Shendure J, Starita LM, Papenfuss AT, Roth FP, et al. MaveDB: an open-source platform to distribute and interpret data from multiplexed assays of variant effect. Genome Biol. 2019;20:1–11.

- Notin P, Kollasch A, Ritter D, Van Niekerk L, Paul S, Spinner H, et al. Proteingym: Large-scale benchmarks for protein fitness prediction and design. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2023;36:64331–79.

- Hsu C, Nisonoff H, Fannjiang C, Listgarten J. Learning protein fitness models from evolutionary and assay-labeled data. Nat Biotechnol. 2022 ;40(7):1114–22. 1 July.

- LaFlam TN, Billesbølle CB, Dinh T, Wolfreys FD, Lu E, Matteson T, et al. Phenotypic pleiotropy of missense variants in human B cell-confinement receptor P2RY8. bioRxiv. 2025;2025–02.

- Ellingford JM, Ahn JW, Bagnall RD, Baralle D, Barton S, Campbell C, et al. Recommendations for clinical interpretation of variants found in non-coding regions of the genome. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):73.

- Wang Z, Zhao G, Li B, Fang Z, Chen Q, Wang X, et al. Performance comparison of computational methods for the prediction of the function and pathogenicity of non-coding variants. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2023;21(3):649–61.

- Sasse A, Chikina M, Mostafavi S. Unlocking gene regulation with sequence-to-function models. Nat Methods. 2024;21(8):1374–7.

- Consortium Gte. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369(6509):1318–30.

- Linder J, Srivastava D, Yuan H, Agarwal V, Kelley DR. Predicting RNA-seq coverage from DNA sequence as a unifying model of gene regulation. Nat Genet [Internet]. 2025 Jan 8. [CrossRef]

- Karollus A, Mauermeier T, Gagneur J. Current sequence-based models capture gene expression determinants in promoters but mostly ignore distal enhancers. Genome Biol. 2023 Mar 27;24(1):56.

- Regev A, Teichmann SA, Lander ES, Amit I, Benoist C, Birney E, et al. The human cell atlas. elife. 2017;6:e27041.

- Cammaerts S, Strazisar M, Dierckx J, Del Favero J, De Rijk P. miRVaS: a tool to predict the impact of genetic variants on miRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(3):e23–e23.

- Barenboim M, Zoltick BJ, Guo Y, Weinberger DR. MicroSNiPer: a web tool for prediction of SNP effects on putative microRNA targets. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(11):1223–32.

- Sonney S, Leipzig J, Lott MT, Zhang S, Procaccio V, Wallace DC, et al. Predicting the pathogenicity of novel variants in mitochondrial tRNA with MitoTIP. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(12):e1005867.

- Sabarinathan R, Tafer H, Seemann SE, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF, Gorodkin J. RNA snp: efficient detection of local RNA secondary structure changes induced by SNP s. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(4):546–56.

- Quang D, Chen Y, Xie X. DANN: a deep learning approach for annotating the pathogenicity of genetic variants. Bioinformatics. 2014;31(5):761–3.

- Vishniakov K, Viswanathan K, Medvedev A, Kanithi PK, Pimentel MA, Rajan R, et al. Genomic Foundationless Models: Pretraining Does Not Promise Performance. bioRxiv. 2024;2024–12.

- He AY, Palamuttam NP, Danko CG. Training deep learning models on personalized genomic sequences improves variant effect prediction. United States; 2025.

- He Y, Fang P, Shan Y, Pan Y, Wei Y, Chen Y, et al. Generalized biological foundation model with unified nucleic acid and protein language. Nat Mach Intell. 2025;1–12.

- Brandes N, Weissbrod O, Linial M. Open problems in human trait genetics. Genome Biol. 2022;23(1):131.

- Schaid DJ, Chen W, Larson NB. From genome-wide associations to candidate causal variants by statistical fine-mapping. Nat Rev Genet. 2018 Aug 1;19(8):491–504.

- Kathail P, Bajwa A, Ioannidis NM. Leveraging genomic deep learning models for non-coding variant effect prediction. ArXiv Prepr ArXiv241111158. 2024.

- Gusev A, Ko A, Shi H, Bhatia G, Chung W, Penninx BWJH, et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2016 Mar 1;48(3):245–52.

- Brandes N, Linial N, Linial M. PWAS: proteome-wide association study—linking genes and phenotypes by functional variation in proteins. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):173.

- Kelman G, Zucker R, Brandes N, Linial M. PWAS Hub for exploring gene-based associations of common complex diseases. Genome Res. 2024;34(10):1674–86.

- Kim SS, Dey KK, Weissbrod O, Márquez-Luna C, Gazal S, Price AL. Improving the informativeness of Mendelian disease-derived pathogenicity scores for common disease. Nat Commun. 2020 Dec 7;11(1):6258.

- Benegas G, Eraslan G, Song YS. Benchmarking DNA Sequence Models for Causal Variant Prediction in Human Genetics.

- Choi SW, Mak TSH, O’Reilly PF. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(9):2759–72.

- Polderman TJC, Benyamin B, de Leeuw CA, Sullivan PF, van Bochoven A, Visscher PM, et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet. 2015 ;47(7):702–9. 1 July.

- Mäki-Tanila A, Hill WG. Influence of Gene Interaction on Complex Trait Variation with Multilocus Models. Genetics. 2014 July;198(1):355–67.

- Moore JH, Williams SM. Traversing the conceptual divide between biological and statistical epistasis: systems biology and a more modern synthesis. Bioessays. 2005;27(6):637–46.

- Génin, E. Missing heritability of complex diseases: case solved? Hum Genet. 2020 Jan 1;139(1):103–13.

- Zuk O, Hechter E, Sunyaev SR, Lander ES. The mystery of missing heritability: Genetic interactions create phantom heritability. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(4):1193–8.

- Li J, Li X, Zhang S, Snyder M. Gene-environment interaction in the era of precision medicine. Cell. 2019;177(1):38–44.

- Brandes N, Linial N, Linial M. Genetic association studies of alterations in protein function expose recessive effects on cancer predisposition. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14901.

- Zheng Z, Liu S, Sidorenko J, Wang Y, Lin T, Yengo L, et al. Leveraging functional genomic annotations and genome coverage to improve polygenic prediction of complex traits within and between ancestries. Nat Genet. 2024 ;56(5):767–77. 1 May.

- Fiziev PP, McRae J, Ulirsch JC, Dron JS, Hamp T, Yang Y, et al. Rare penetrant mutations confer severe risk of common diseases. Science. 2023;380(6648):eabo1131.

- Moldovan A, Waldman YY, Brandes N, Linial M. Body mass index and birth weight improve polygenic risk score for type 2 diabetes. J Pers Med. 2021;11(6):582.

- Lin J, Mars N, Fu Y, Ripatti P, Kiiskinen T, Tukiainen T, et al. Integration of Biomarker Polygenic Risk Score Improves Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2023 Dec;8(12):1489–99.

- Samani NJ, Beeston E, Greengrass C, Riveros-McKay F, Debiec R, Lawday D, et al. Polygenic risk score adds to a clinical risk score in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in a clinical setting. Eur Heart J. 2024 Sept 7;45(34):3152–60.

- McHugh JK, Bancroft EK, Saunders E, Brook MN, McGrowder E, Wakerell S, et al. Assessment of a polygenic risk score in screening for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(14):1406–17.

- Padrik P, Tõnisson N, Hovda T, Sahlberg KK, Hovig E, Costa L, et al. Guidance for the Clinical Use of the Breast Cancer Polygenic Risk Scores. Cancers [Internet]. 2025;17(7). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/17/7/1056.

- Abu-El-Haija A, Reddi HV, Wand H, Rose NC, Mori M, Qian E, et al. The clinical application of polygenic risk scores: A points to consider statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2023;25(5):100803.

- Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat Genet. 2019 Apr 1;51(4):584–91.

- Templeton A, Conerly T, Marcus J, Lindsey J, Bricken T, Chen B, et al. Scaling Monosemanticity: Extracting Interpretable Features from Claude 3 Sonnet. Transform Circuits Thread [Internet]. 2024; Available from: https://transformer-circuits.pub/2024/scaling-monosemanticity/index.html.

- Ameisen E, Lindsey J, Pearce A, Gurnee W, Turner NL, Chen B, et al. Circuit Tracing: Revealing Computational Graphs in Language Models. Transform Circuits Thread [Internet]. 2025; Available from: https://transformer-circuits.pub/2025/attribution-graphs/methods.html.

- Liao SE, Sudarshan M, Regev O. Deciphering RNA splicing logic with interpretable machine learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2023;120(41):e2221165120.

- Xiao K, Engstrom L, Ilyas A, Madry A. Noise or signal: The role of image backgrounds in object recognition. ArXiv Prepr ArXiv200609994. 2020.

- Jain S, Wallace BC. Attention is not explanation. ArXiv Prepr ArXiv190210186. 2019.

- Ma Z, He J, Qiu J, Cao H, Wang Y, Sun Z, et al. BaGuaLu: targeting brain scale pretrained models with over 37 million cores. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGPLAN Symposium on Principles and Practice of Parallel Programming. 2022. p. 192–204.

- Bloomfield D, Pannu J, Zhu AW, Ng MY, Lewis A, Bendavid E, et al. AI and biosecurity: The need for governance. Science. 2024;385(6711):831–3.

| Term | Definition |

| Amino acid | The molecular building block of proteins. There are 20 standard amino acids (and a few non-standard ones) which can be chained together in numerous arrangements to form protein sequences. |

| Burden test | A statistical method used to detect genes or other genomic regions associated with a trait. Instead of testing each variant separately, burden tests combine multiple variants into a single score that represents the overall burden of variants in a region per individual. The burden score is then tested for correlation with the trait across individuals. |

| Coding & non-coding genomic region | Coding regions in the genome contain instructions for creating proteins, whereas non-coding genomic regions have other functions, usually related to gene regulation. Mutations are also described as coding or non-coding, depending on whether they affect the sequence of a protein product. |

| Chromatin mark | A chemical modification of the DNA complex, known as chromatin. Common examples include DNA methylation and histone modifications. The state of the chromatin has a critical role in gene expression regulation. |

| Deep learning | A machine-learning approach based on artificial neural networks. Each artificial neuron is represented by a number and can affect the numeric values of downstream neurons in the network, depending on the strength of connections (weights) between pairs of neurons. The more neuron layers there are between the input and output, the deeper the network is. |

| Exon & intron | Genes are made up of exons and introns. Exons are the parts of a gene that remain in the final RNA, while introns are removed during RNA processing in a process called splicing. |

| Feature | In machine learning, a feature is an individual measurable property given as input to a model. Features can be anything from the age of a patient to the GC content of a DNA sequence, depending on the problem. The choice and design of features heavily influence model performance, especially in classical machine learning. |

| Fitness | A quantitative measure of an organism’s reproductive success. Mutations that improve survival or reproduction increase fitness and are favored by natural selection. |

| Foundation model | A large, general-purpose AI model trained on massive data and designed to be highly adaptable. Instead of being trained for one specific task, foundation models learn broad knowledge and representations that can be repurposed for diverse applications. Large language models are a notable example. |

| Gene | A segment of the genome that contains the instructions for making an RNA product, which in turn is often translated to a protein product. |

| Homology | Similarity between genomic sequences due to shared evolutionary origin. Homologous sequences often have related functions, meaning that knowledge about one can be used to make inferences about the other. |

| Genetic effect | The influence that a genetic factor, such as a variant or a gene, has on a trait. Some genetic effects can single-handedly lead to severe disease, while others are more subtle. |

| Genome | The complete set of DNA in an organism, including all the genes and non-coding regions. |

| Genome-wide association study (GWAS) | A study design used to identify genetic variants associated with a trait by scanning the entire genome in a large population. Each variant is tested for statistical correlation with the trait, for example whether it is more common in cases (people with a given disease) than controls (people without it). |

| Genotype & phenotype | Genotype refers to an individual’s genetic makeup, including the specific variants they carry. Phenotype refers to an observable trait, such as height, disease status, or gene expression levels. Much of human genetics is studying how specific genotypes affect specific phenotypes. |

| Large language model (LLM) | A deep-learning model trained to predict the next piece of text in a given source (usually taken from the internet) given all the text that came before it. This simple training task, if applied over huge amounts of text and compute, has given rise to some of the most capable models (such OpenAI’s GPT models which power ChatGPT). |

| Monogenic / Mendelian & polygenic / complex disease | Monogenic (or Mendelian) diseases are caused by mutations in a single gene and follow clear inheritance patterns. Polygenic (or complex) diseases, in contrast, are influenced by many genetic variants, most of which have small effects, along with environmental factors (and their complex interactions). |

| Multiple sequence alignment | A method for lining up multiple genomic sequences so that similar positions across sequences are aligned. This helps identify and characterize conserved regions of shared origin and infer evolutionary constraints. |

| Mutation / variant | A change in a DNA sequence, considered the basic unit of genetic difference between individuals. The terms “mutation” and “variant” sometimes carry different nuances, but are used largely interchangeably in this review. |

| Nucleotide (nt) | The building block of DNA and RNA molecules. DNA and RNA sequences can be represented as strings in a four-letter alphabet consisting of the four nucleotides: A, C, G, and T (for DNA) or U (for RNA). Sequence lengths are measured in nucleotides (e.g., 120 nt). |

| Promoter & enhancer | Regulatory DNA sequences that control when and how much genes are expressed (i.e., transcribed into RNA). A promoter is located near the start of a gene and is required to initiate transcription. Enhancers can be farther away and boost gene activity. |

| Protein | The molecules that carry out most biological functions that sustain life, from catalyzing chemical reactions to connecting tissues. Proteins are made of long chains of amino acids folded into specific 3D structures. A protein’s sequence determines its structure and function. Mutations that change that sequence can disrupt the protein and cause disease. |

| Phylogeny | The evolutionary relationships among species or genes, often represented as a tree. Phylogenies are reconstructed by comparing genomic sequences to infer how species or sequences have diverged and evolved over time. |

| Splicing | A biological process that removes specific parts of an RNA (called introns) and joins the remaining pieces (called exons) to create a mature RNA molecule. Splicing is guided by specific sequences, primarily the splice donor at the start of an intron and the splice acceptor at its end. Errors in splicing can change the resulting RNA molecule and cause disease. |

| Supervised learning | Training machine-learning models on labeled data, where each sample has a label indicating the desired prediction value. |

| Transcript / RNA | A biological molecule similar to DNA, produced by transcribing the sequence of a gene. Some RNA molecules code for proteins; others help regulate genes or support other biological functions. |

| Wildtype | An unmutated sequence, used as a reference point when studying genetic variation. A wildtype gene, protein or organism is one without the specific changes being investigated. |

| Zero-shot prediction | Application of an AI model to a task it hasn’t been explicitly trained to perform without fine-tuning or changing the model. For example, it turns out that protein language models, which have been trained to predict wild-type protein sequences across different species, can predict whether coding mutations in the human genome are pathogenic or benign. |

| Task | Model | Repository / Server | Ref |

| Protein / DNA language modeling | ESM | github.com/facebookresearch/esm | [5,6] |

| Evo2 | github.com/ArcInstitute/evo2 | [7] | |

| Protein structure prediction | AlphaFold |

alphafoldserver.com alphafold.ebi.ac.uk |

[3] |

| ESMFold |

github.com/facebookresearch/esm esmatlas.com/resources |

[5] | |

| RoseTTAFold | github.com/RosettaCommons/RoseTTAFold | [8] | |

| Variant pathogenicity prediction | AlphaMissense | zenodo.org/records/8360242 | [9] |

| CADD | cadd.gs.washington.edu | [10,11,12] | |

| ESM1b |

github.com/ntranoslab/esm-variants huggingface.co/spaces/ntranoslab/esm_variants |

[13] | |

| EVE | evemodel.org | [14] | |

| Evo2 | github.com/ArcInstitute/evo2 | [7] | |

| FATHMM | fathmm.biocompute.org.uk | [15,16] | |

| GPN-MSA | huggingface.co/collections/songlab/gpn-msa-65319280c93c85e11c803887 | [17] | |

| PhyloGPN | huggingface.co/songlab/PhyloGPN | [18] | |

| phyloP | compgen.cshl.edu/phast | [19] | |

| PolyPhen-2 | genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2 | [20] | |

| PrimateAI-3D | primateai3d.basespace.illumina.com | [21] | |

| REVEL | sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics | [22] | |

| SIFT | sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg | [23] | |

| Predicting variant effects on chromatin & gene regulation | AlphaGenome | deepmind.google.com/science/alphagenome | [24] |

| Borzoi | github.com/calico/borzoi | [25] | |

| DeepSEA | deepsea.princeton.edu | [26] | |

| Enformer | github.com/google-deepmind/deepmind-research/tree/master/enformer | [27] | |

| ExPecto | hb.flatironinstitute.org/expecto | [28] | |

| PrediXcan | github.com/hakyimlab/PrediXcan | [29] | |

| SpliceAI | github.com/Illumina/SpliceAI | [30] | |

| Fine-mapping GWAS results | cV2F | github.com/Deylab999MSKCC/cv2f | [31] |

| GWAVA | www.sanger.ac.uk/tool/gwava | [32] | |

| FLAMES | github.com/Marijn-Schipper/FLAMES | [33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).