In this section, the compressive strength of all mixtures is discussed.

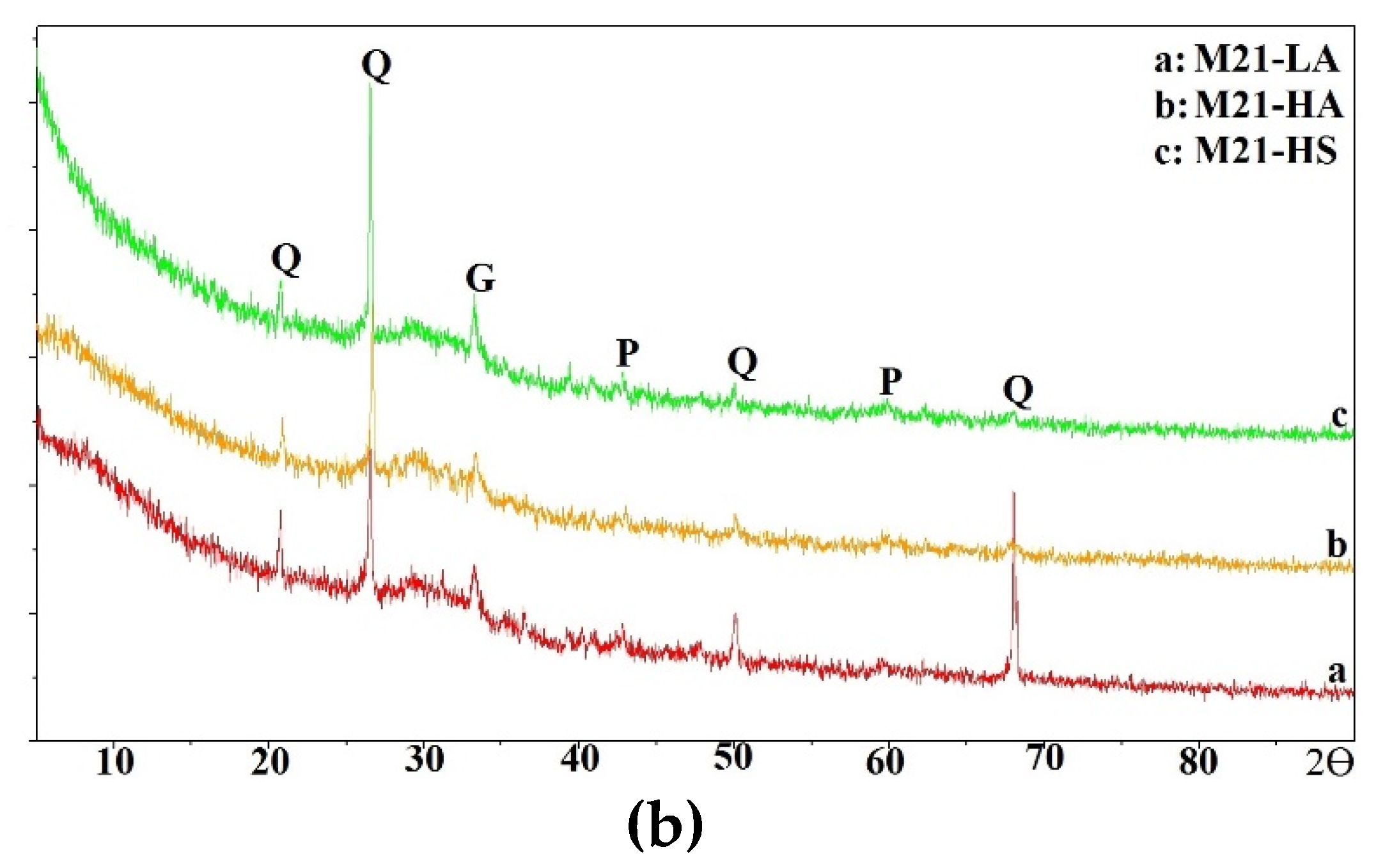

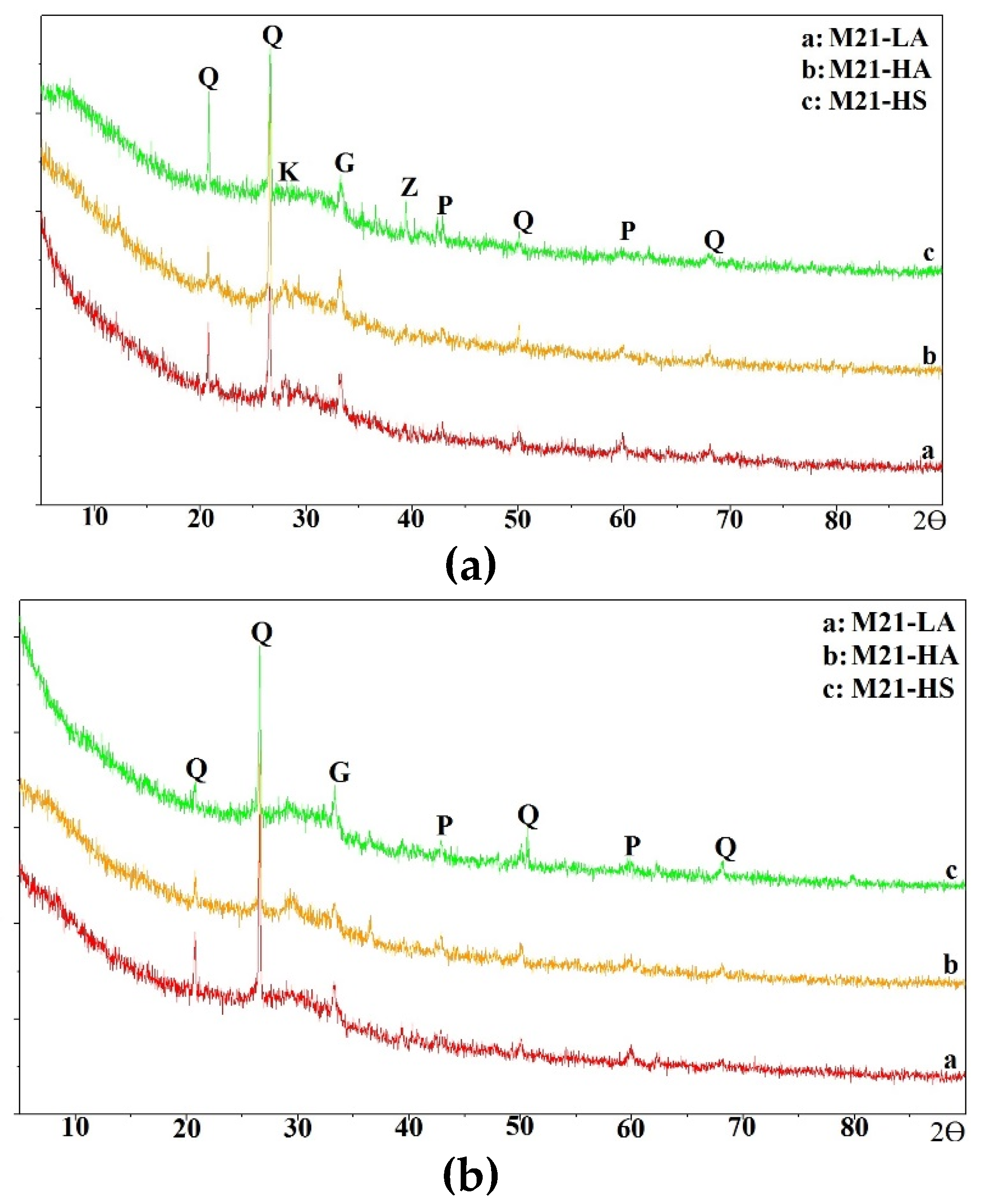

4.2.1. Compressive Strength of AAM Cured at Ambient Temperatures

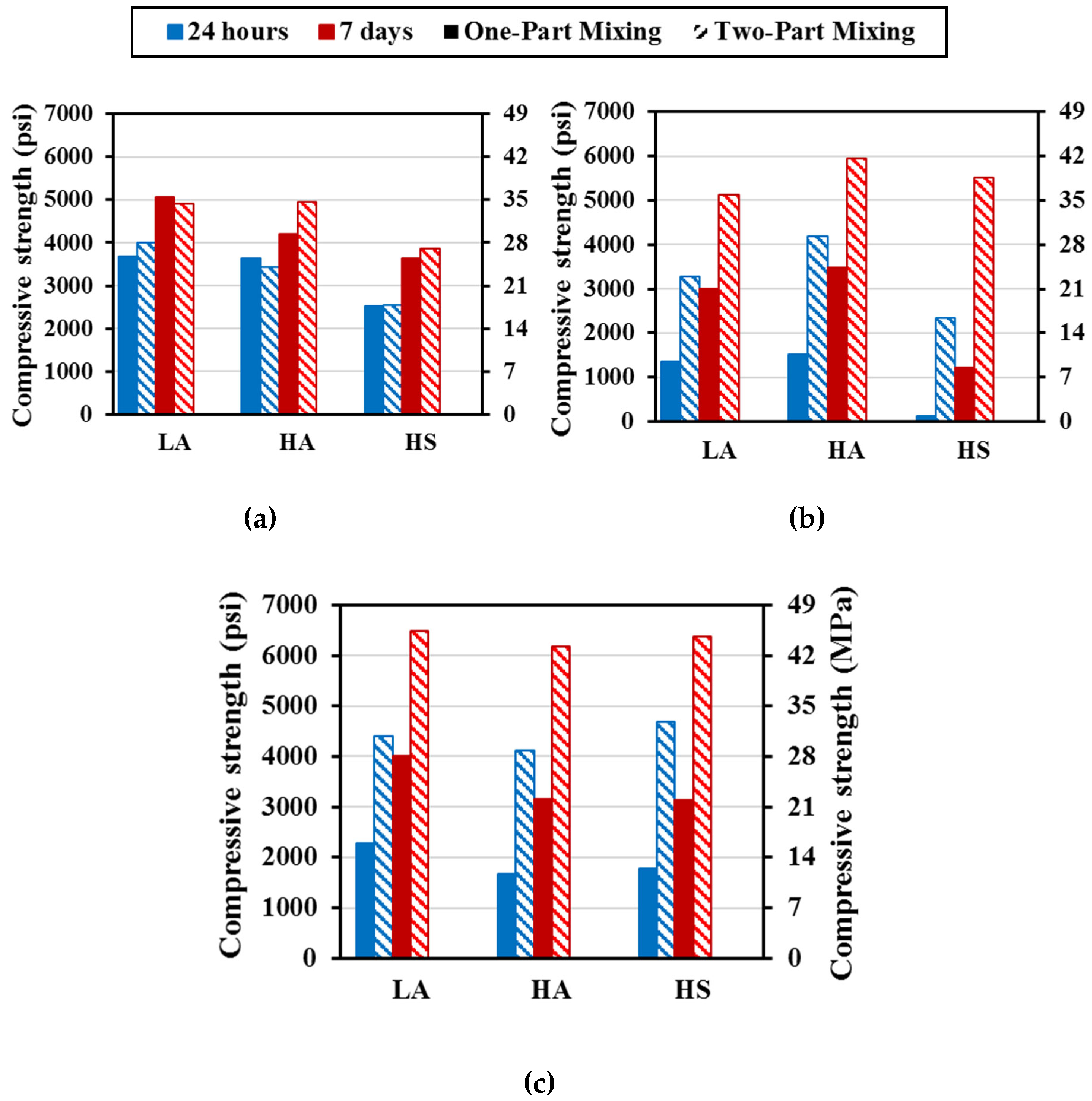

M37 had the highest compressive strength values for specimens cured at 30° C (86° F), followed by M29, and M21 with two-part mixes displayed higher compressive strengths than the corresponding one-part mixes. The compressive strength of the one-part mixtures cured at 30° C (86° F) for 24 hours ranged from 17.4 to 25.4 MPa (2520 to 3680 psi) for M29, from 0.84 to 10.5 MPa (120 to 1520 psi), for M21, and 11.5 to 15.7 MPa (1670 to 2280 psi) for M37 (

Figure 5). These values represented approximately 94% to 99% of the compressive strength of their corresponding two-part M29, 5% to 42% for M21, and 38% to 52% for M37.

The compressive strength of the one-part and two-part mixture increased with increasing the curing time to 7 days. The compressive strength values increased by approximately 37%, 15%, and 44% for mixes LA, HA, and HS mixes of M29; approximately 120% and 290% for LA and HA mixes of M21, while in the case of mix HS, the 7-day compressive strength was 10 times greater than the 1-day strength. For M37 mixes, a 76%, 89%, and 75% strength increase were observed between the 1-day and 7-day strength of mixes LA, HA, and HS, respectively.

The tremendous difference in the compressive strengths of one-part and two-part AAM mixes was due to the physical properties of the mix (i.e. workability), the pH, and the solubility product of the materials.

It was shown in previous studies that the strength development of alkali-activated systems comes from a combination between the geopolymerization and hydration processes. The contribution of each process depends on many factors, such as, curing temperature, curing time, added alkali-activators, and the chemical composition of FA. In short, the geopolymerization process’s contribution to the strength development increases with increasing the curing temperature, curing time, alkali-activators and the silica and alumina contents of the FA. The hydration process’s contribution to the strength development increases with decreasing the curing temperature (in case of oven-dry curing), increasing curing time, and increasing the calcium content of FA.

As stated earlier, in the case of one-part mixing system the dissolutions of all elements in water started simultaneously. Contrary to the two-part mixing system, using liquid activator solutions created a favorable environment for the geopolymerization reaction by improving the dissolution and hydrolysis mechanisms [

17,

18] which affected the compressive strength development of the mixes.

The geopolymerization reaction is influenced by the Si/Al and calcium content of the precursor as well as the alkalinity and constituent of the activators. The silica availability controls the strength development while the alumina content controls the setting properties [

12]. In the case of two-part mixes, the high availability of dissolved silica in addition to the presence of dissolved calcium led to formation of products such calcium-silicate-hydrate (CSH) and/or calcium-aluminate-silicate- hydrate (CASH) which influences the high strength development of cementitious materials at ambient temperature. For one-part mixes, the faster dissolution of alumina compared to silica, leads to a high concentration of dissolved alumina in the solution which reduces the dissolution capacity of Si in water [

19]. In addition, the dissolution of calcium species and hydroxyl ions in the mix, would lead to having a solution saturated essentially with calcium, alumina and hydroxyl ions, and thus precipitation of products such as calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)

2) and calcium-aluminate-hydrates which hinders the strength development of the mixes [

20].

The variation of compressive strength of AAM mixes with respect to their source material (FA), was mainly due to the difference in the chemical composition of their respective source materials (i.e. FA). FA C37 having the highest calcium content, had the higher ability for its mixes to develop relatively higher strength at 30° C (86° F) where the hydration process does not require relatively high temperature to take place. FA C21 with the lowest calcium content and higher Al and Si content, required much elevated temperature for fast strength development. However, due to the high surface area of FA C29 (

Table 1) compared to the remaining FAs, both the dissolution and the reaction rate of M29 mixes happened faster, which influenced the strength development of these mixes at early ages, allowing the 1-day strength of one-part mixes to be similar to those of two-part mixes (

Figure 5a).

4.2.2. Compressive Strength of AAM Cured at Elevated Temperatures

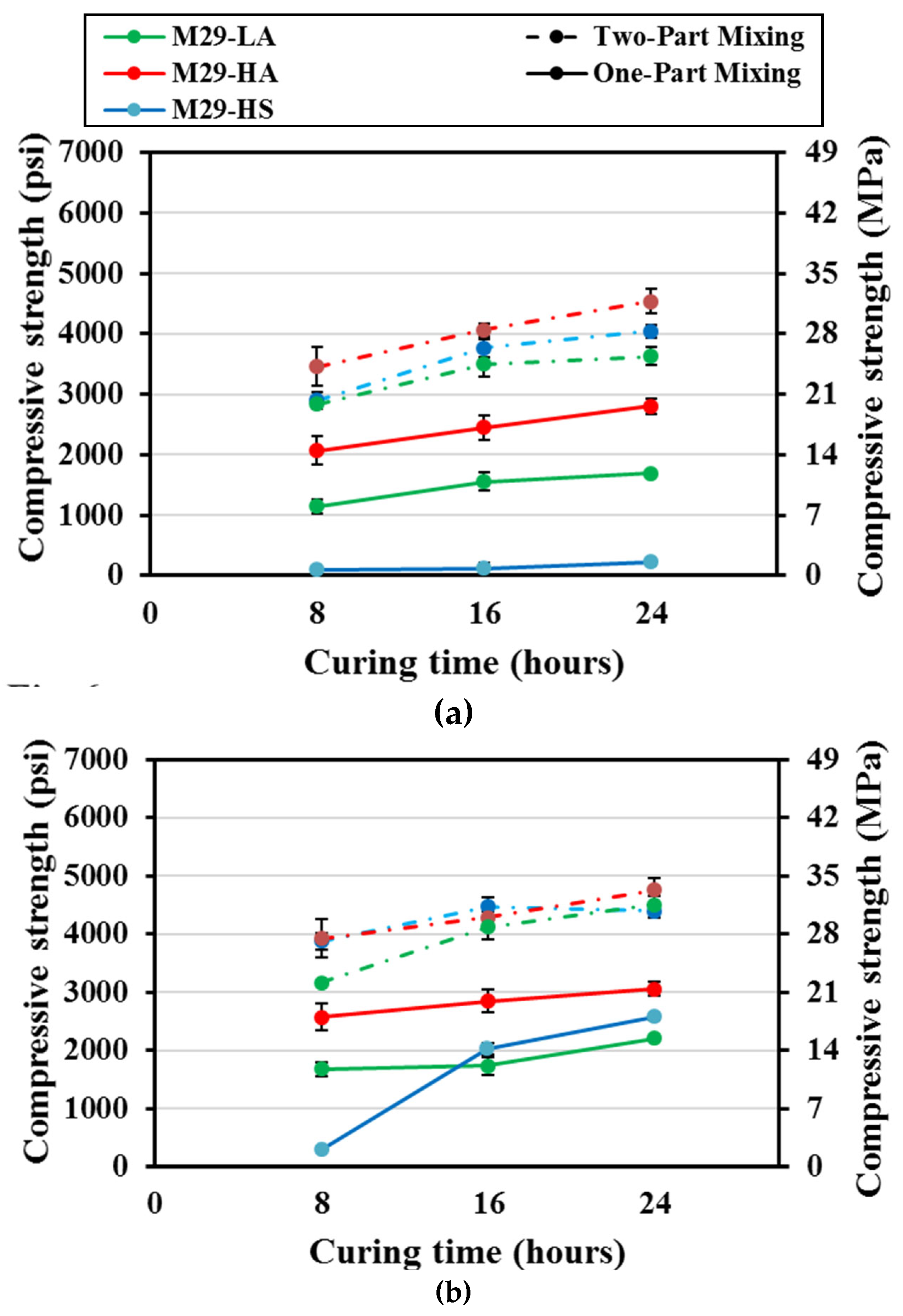

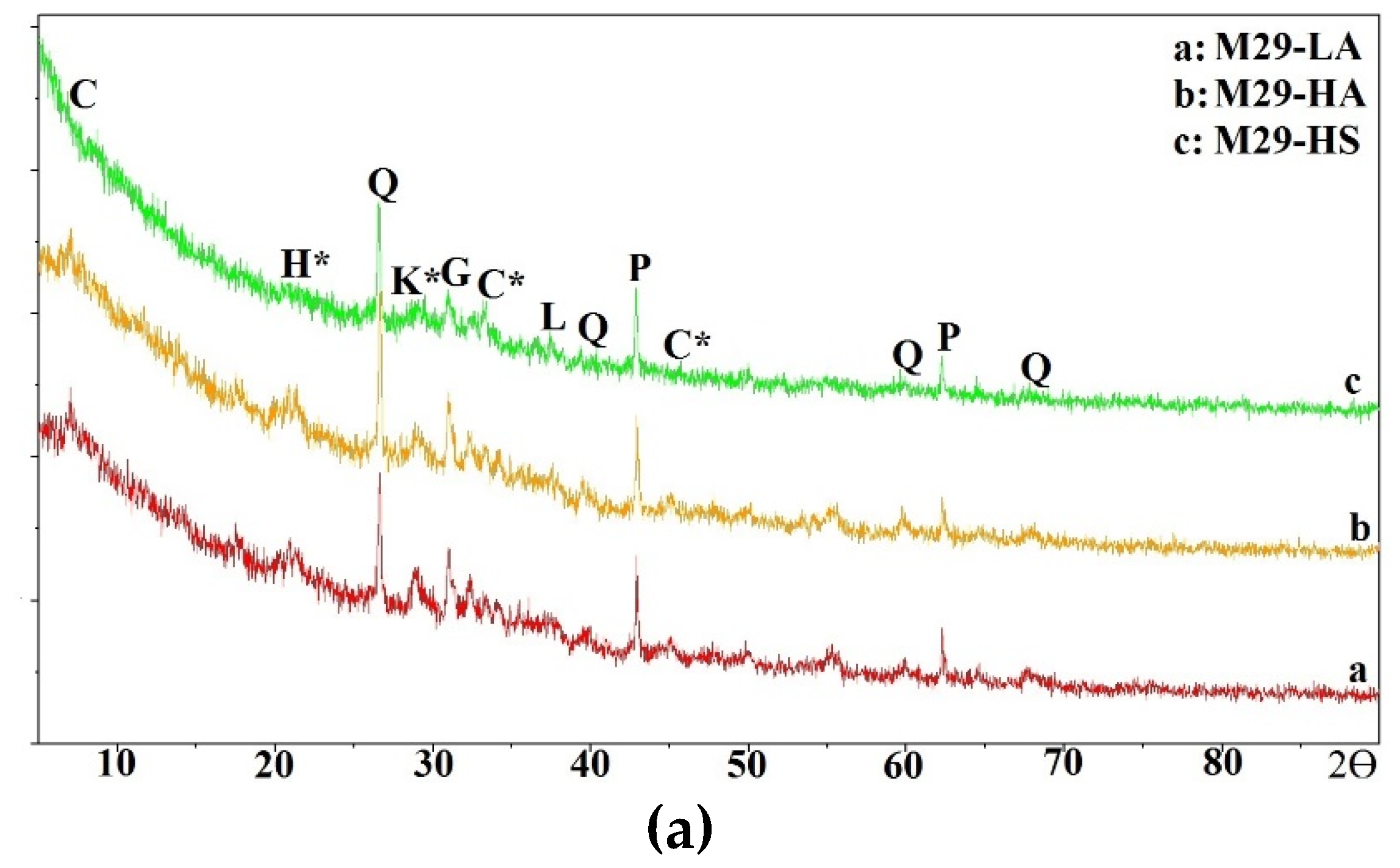

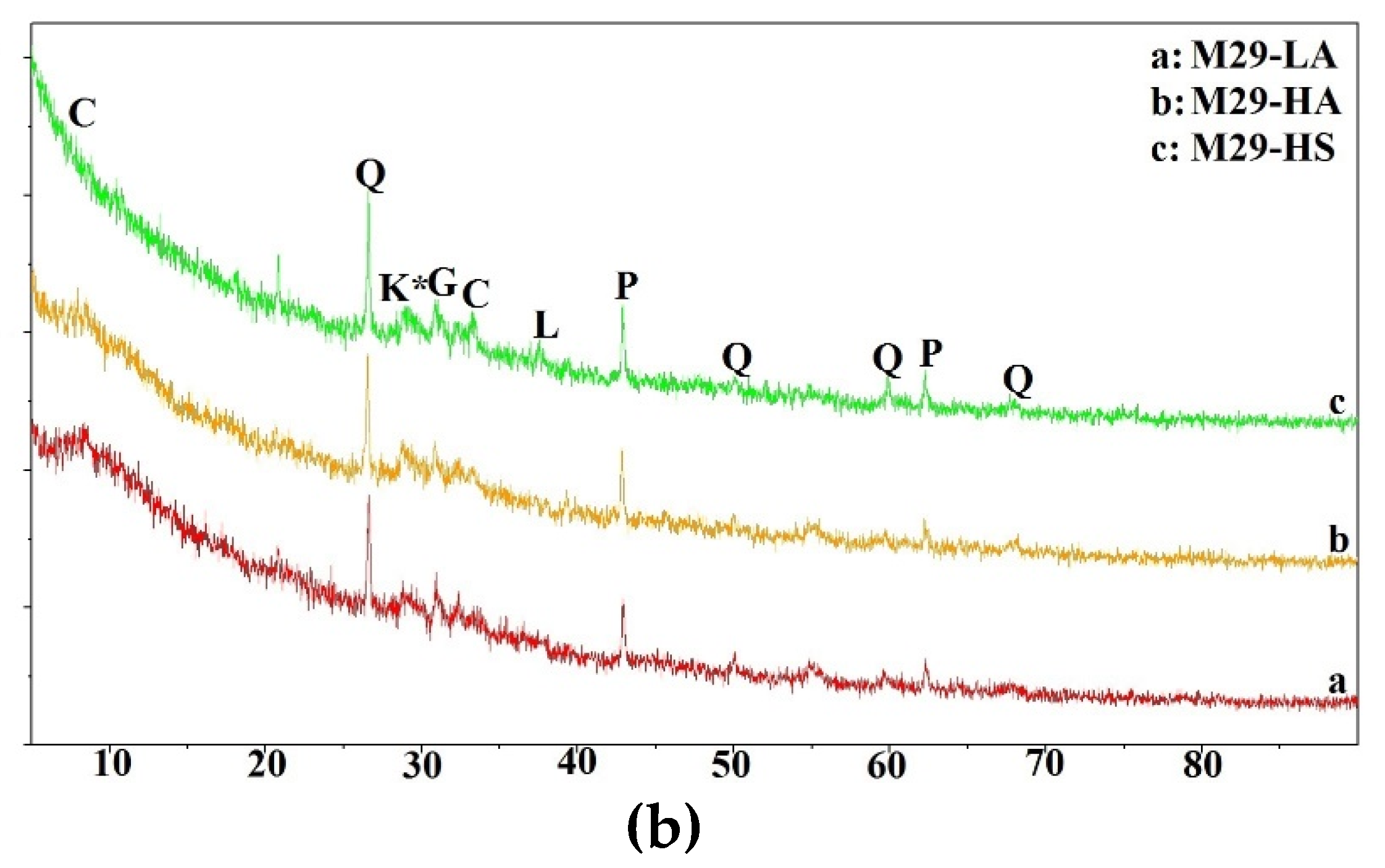

The compressive strengths of the one-part mix M29-HS cured at 55° C (131° F) reached a maximum of 1.5 MPa (220 psi) after 24 h of curing (

Figure 6). However, those of mixes M29-LA and M29-HA increased from 7.89 to 11.7 MPa (1150 to 1690 psi), and from 14.2 to 19.3 MPa (2070 to 2800 psi), respectively, when the curing duration was increased from eight hours to 24 hours. These increases are corresponding to an average strength increase of about 36 - 48%. The two-part mortar mixes displayed compressive strengths of 20 – 23.4 MPa (2900 - 3400 psi) for all M29 mixes, after eight hours of curing; which increased to 27.6 to 32.4 MPa (4000 to 4700 psi) after 24h of curing. These values represent approximately 175% of that of the corresponding one-part M29-LA and M29-HA mixes.

Increasing the curing temperature to 70° C (158° F), improved the strength of one-part M29-LA and M29-HA cured for eight hours by approximately 12%. However, when these mixes were subjected to extended curing time of 16 and 24 hours at 70° C (158° F), they displayed either slightly improved or unchanged strength. Furthermore, higher curing temperature and extending curing time was quite effective for the one-part M29-HS reaching 17.8 MPa (2580 psi) at 24 hours curing time being 11 times greater than the corresponding mixture cured at 55° C (131° F).

In the case of two-part mixing and with increasing the curing temperature, the compressive strengths of mixes M29-HS and M29-HA were approximately the same at eight hours curing and then increased from about 27.6 to 31.0 MPa (4000 to 4500 psi) as the curing duration was increased to 24 hours, respectively; and the strength of mix M29-LA increased from 19.3 to 24.8 MPa (2800 to 3600 psi). Furthermore, increasing the curing temperature from 55 °C (131 °F) to 70° C (158° F) increased the compressive strength by an average of 6% for mixes HA and HS, and 24% for mix LA . At short curing duration of eight hours, the strength of the two-part mix M29-HS was 13 times greater than its one-part counterpart. However, by 24 hours of curing, the one-part mixing strength considerably increased and the average strength of all one-part M29 mixes reached 50% - 80% of the corresponding two-part mixes.

The relatively higher compressive strength of the two-part mixes when compared to the corresponding one-part mixes were related to the favorable reaction environment created by the liquid activators used in two-part as mentioned earlier. The lower strength development of mix M29-HS compared to mixes M29-LA and M29-HA for both one-part and two-part mixes cured at 55° C (131° F) was related to the proportion configuration of these mixes. As shown in

Table 2, mix HS had a SS/SH ratio of 2, while mixes LA and HA had a SS/SH ratio of 1, therefore the lower availability of hydroxyl ions in mix HS as compared to mixes LA and HA implied a lower pH, and thus a relatively slower dissolution rate of the element in this mix (HS). But when the curing temperature was increased to 70° C (158° F), a considerable increase in strength of this mix occurred especially for the one-part mixing, since with increasing the temperature, more silica dissolved and contributed to the strength development of mixes leading to formation of compounds rich in silica, calcium and alumina (CASH).

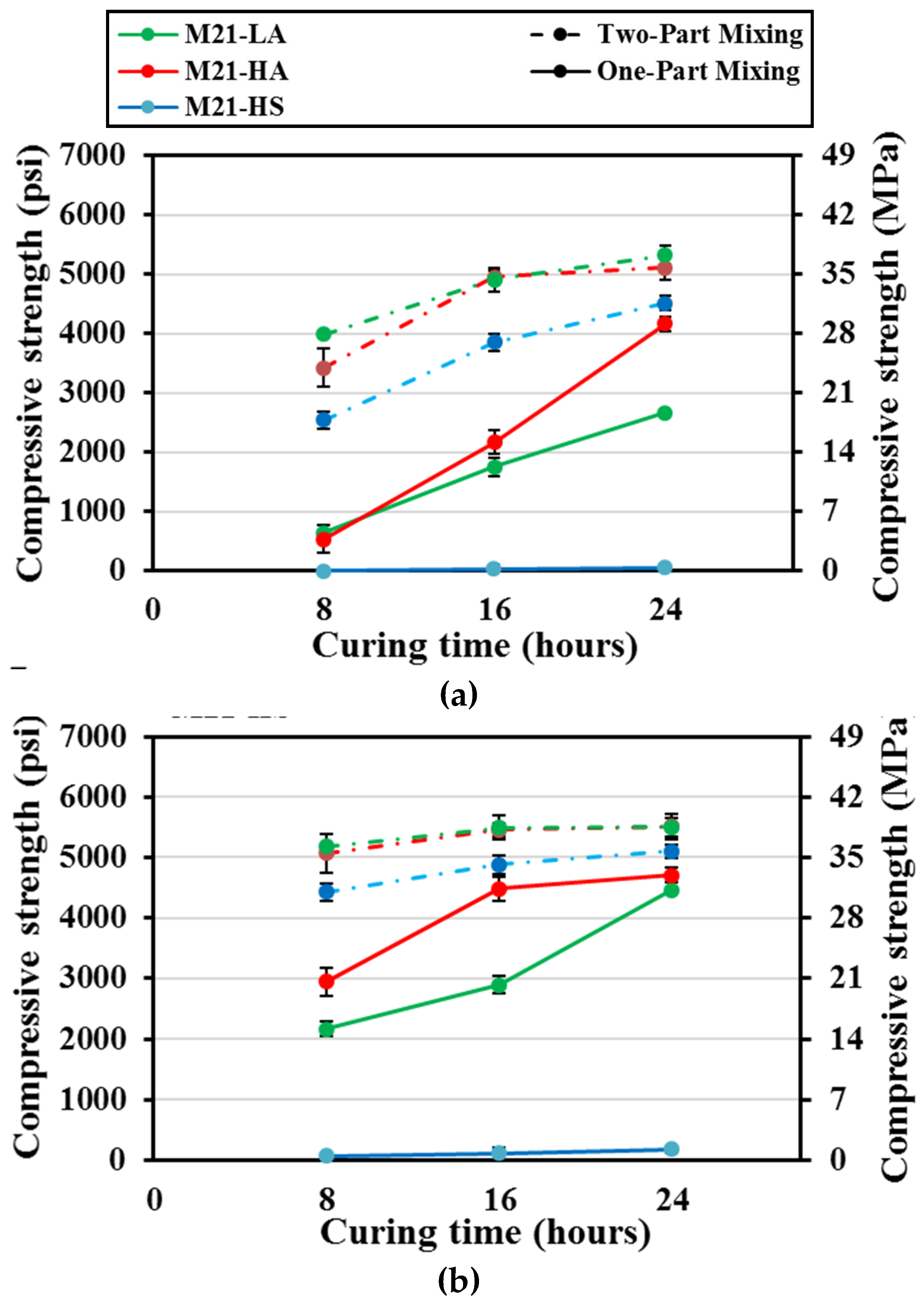

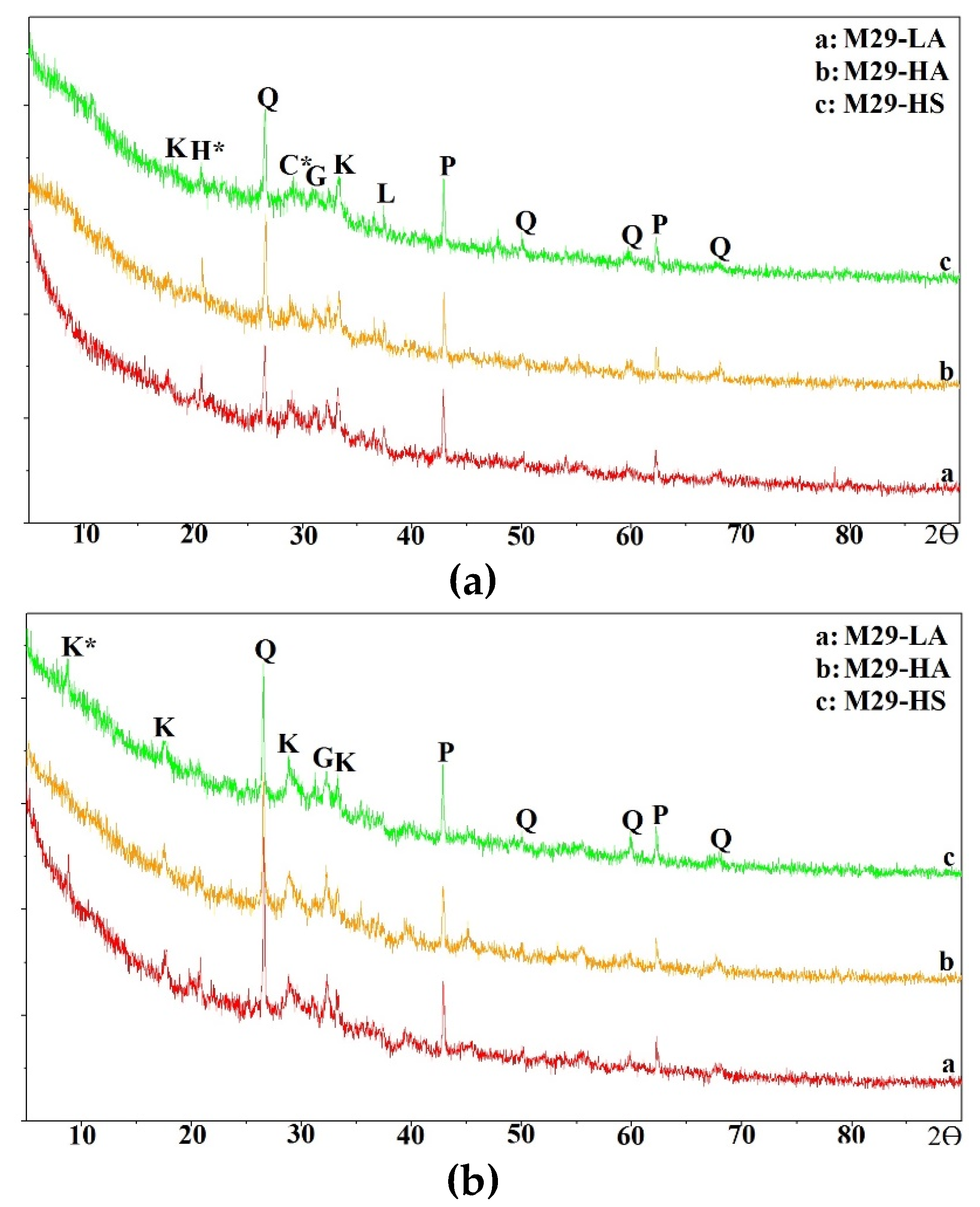

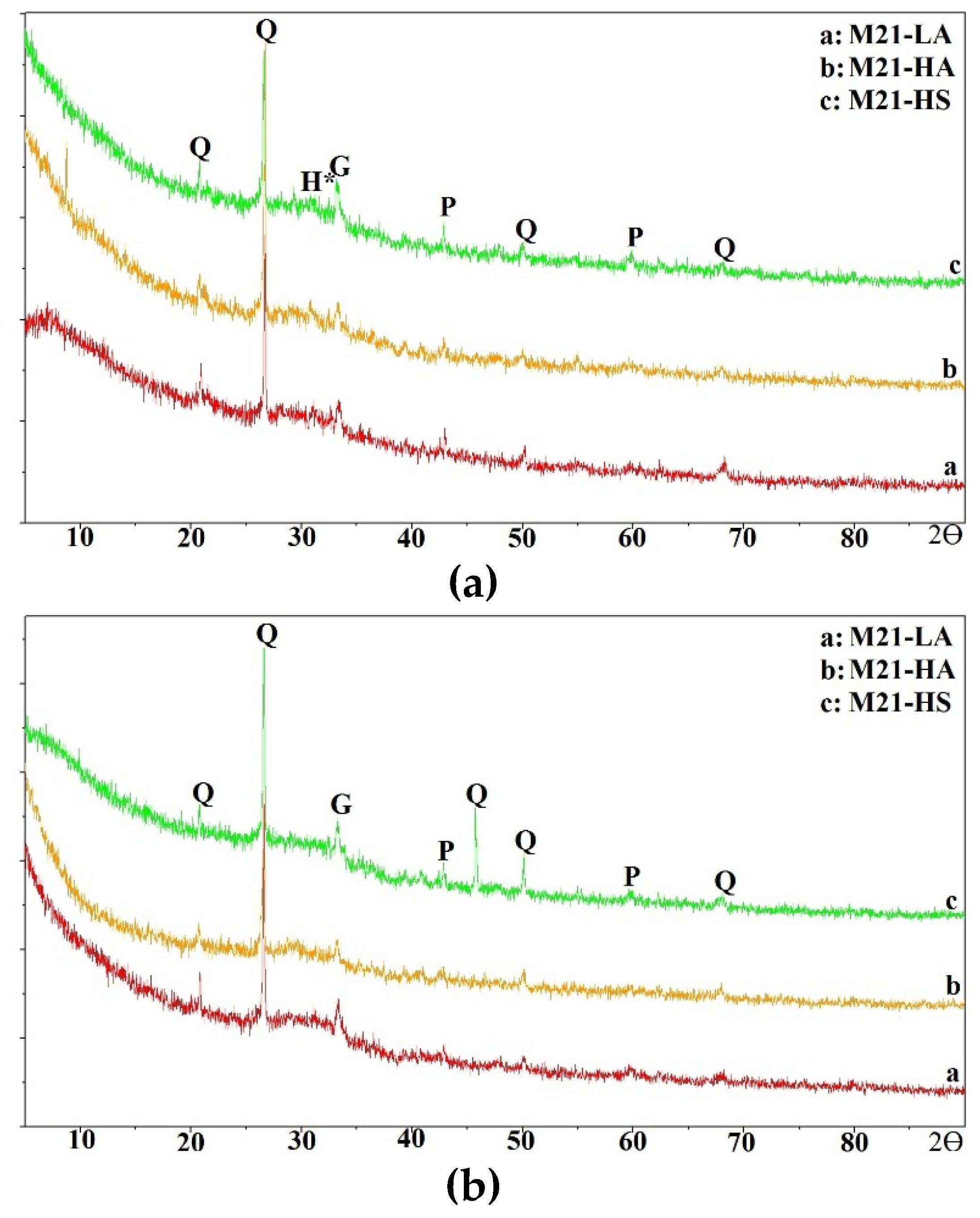

The compressive strengths of the one-part mix M21-HS cured at 55° C (131° F) reached a maximum of 0.34 MPa (50 psi) after 24 h of curing (

Figure 7). However, those of mixes M21-LA and M21-HA significantly increased by 395% to 670%, i.e. from approximately 4 MPa (600 psi) to 18.5 and 26.7 (2680 and 3900 psi), respectively, when the curing duration was increased to 24 hours. The two-part mortar mixes displayed compressive strengths of 17.2 MPa to 27.5 MPa (2500 to 3990 psi) for all M21 mixes, after eight hours of curing; which increased to 31 to 36.7 MPa (4500 to 5320 psi) after 24 hours of curing. These strengths of the two-part M21-LA and M21-HA mixes cured for 24 hours represented approximately 125% to 200% of the corresponding one-part mixtures. For the case of two-part M21-HS mix, the strength was multiple folds higher than that of the corresponding one-part mix at all curing times since the one-part developed very low strength.

Increasing the curing temperature to 70° C (158° F), improved the strength of one-part M21-LA and M21-HA cured for eight hours by approximately 300% and 445% compared to curing at 55° C (131° F). The specimens continued to gain strength as the curing time increased to 16 hours and 24 hours for M21-HA and M21-LA, respectively. However, neither the higher curing temperature nor the extending curing time was effective for the one-part M21-HS reaching 0.7 MPa (100 psi) at 24 hours curing time.

In the case of two-part mixing and with increasing the curing temperature to 70° C (158° F), the compressive strengths of all mixes at eight hours curing increased by 30% to 74% compared to those cured at 55° C (131° F) and then slightly increased reaching 35.2 to 37.9 MPa (5100 to 5500 psi) as the curing duration was increased to 24 hours. At short curing duration of eight hours, the average strengths of the two-part mix M21-LA and M21-HA was approximately 140 - 170% of its counterpart one-part. However, by 24 hours of curing, the one-part mixing strength considerably increased, and the average strength of two-part mixes reached 17% -23% of the corresponding one-part mixes.

The poor strength development observed in the case of mix M21-HS as compared to mixes M21-LA and M21-HA for both one- and two-part AAM was related the less amount of sodium hydroxide in the activator as mentioned earlier. In addition, due to the lower calcium content of FA C21 as shown with

Table 1, formed products in this case would essentially be rich in silica and alumina, which requires high temperature for faster strength development as it is related to the activation energy theory whereby higher kinetic energy is needed to intrigue the geopolymerization action [

21]. The kinetic energy increased by either increasing the temperature or prolonging the duration of curing. This explained the high rise in strength of all mixes as the temperature was increased from 55° C to 70° C (from 131° F to 158° F), or when the duration of curing went from eight hours to 24 hours.

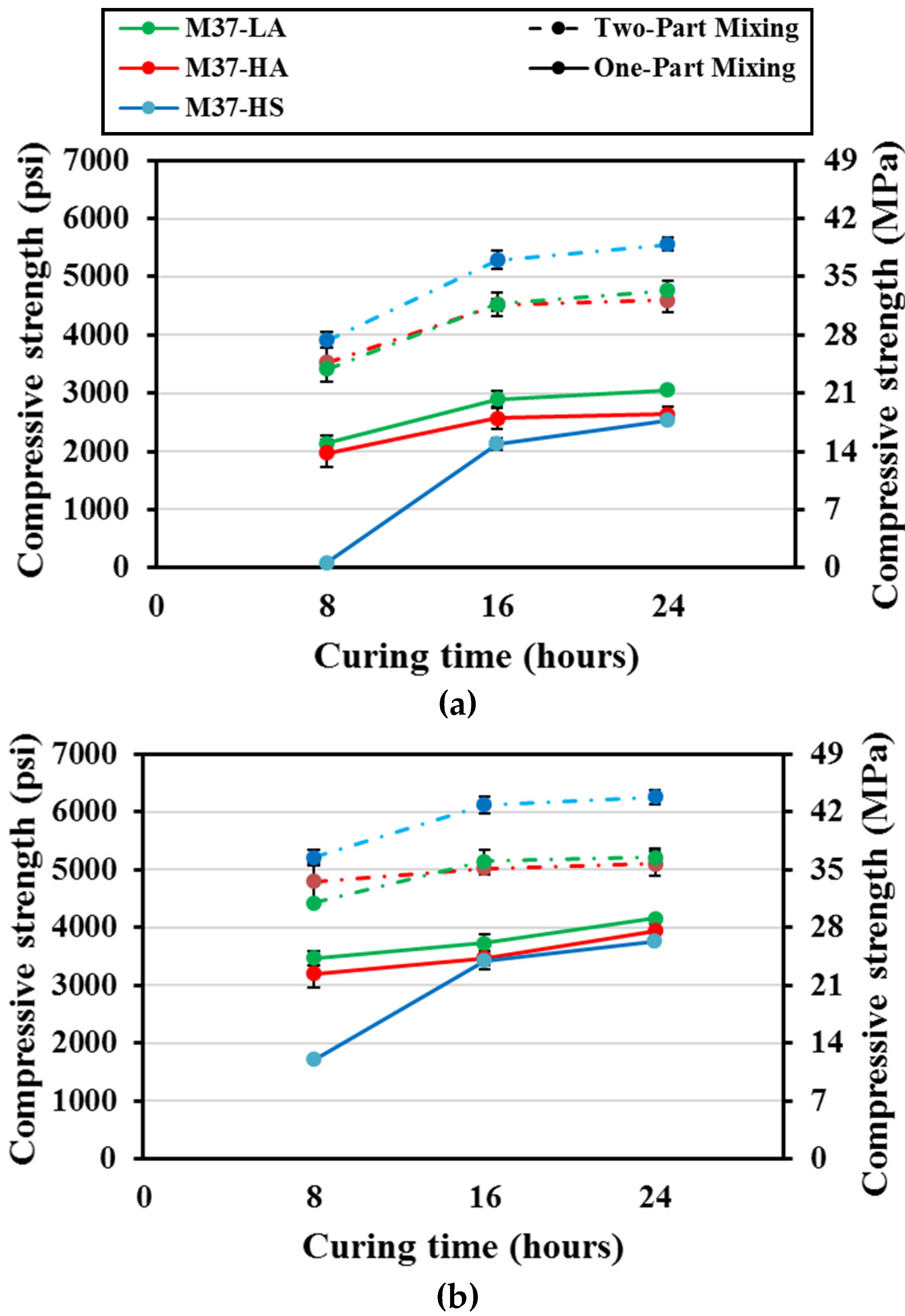

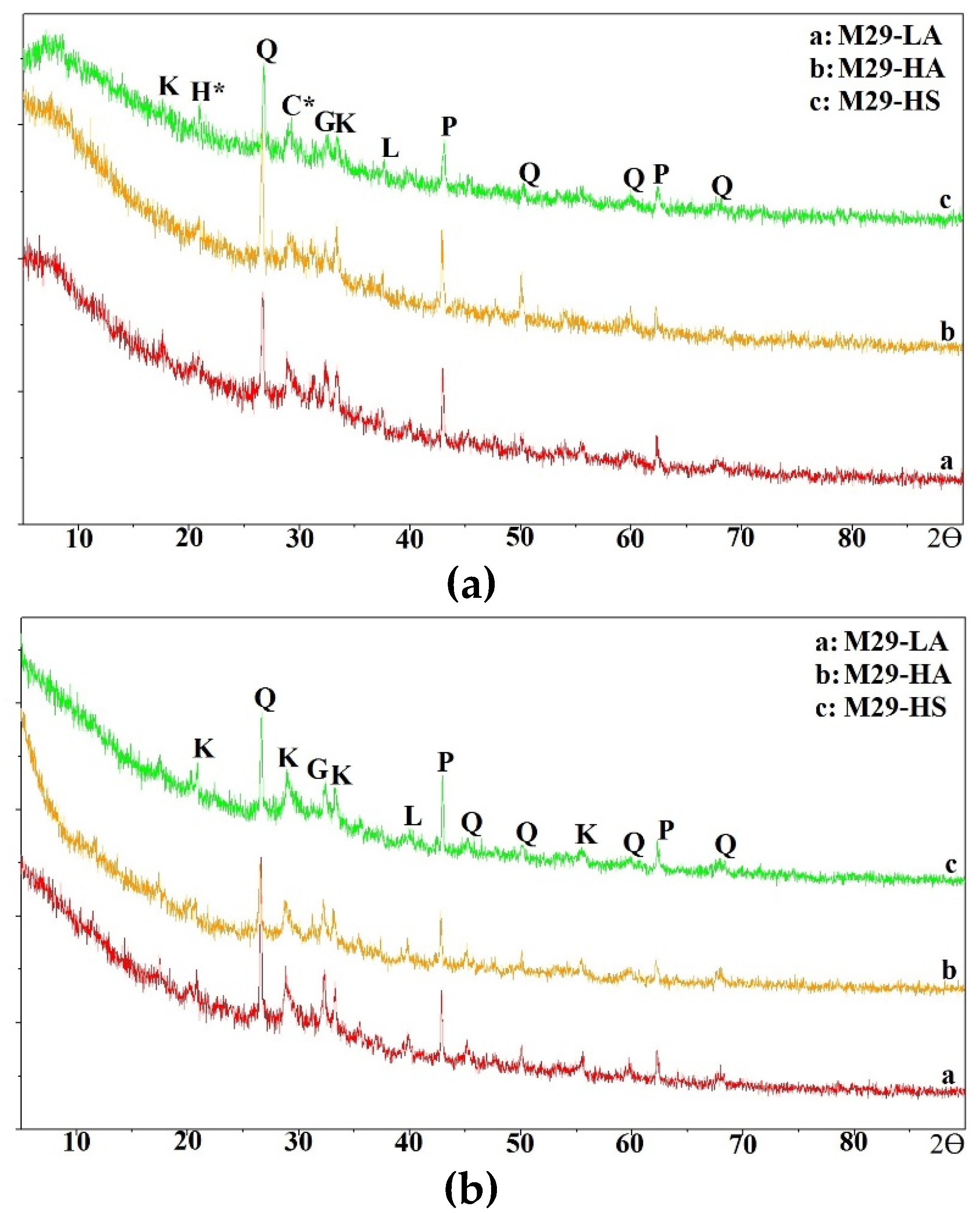

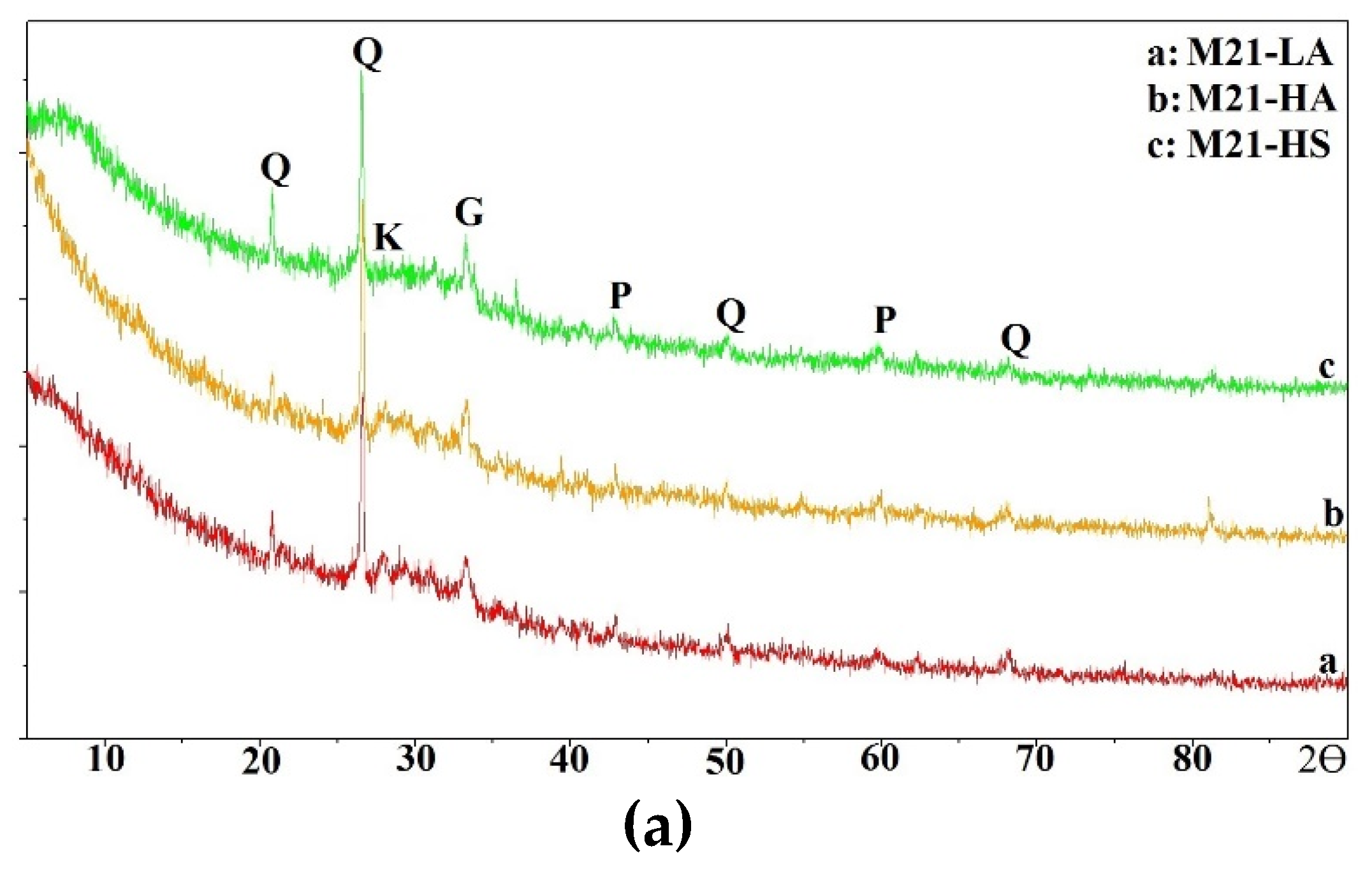

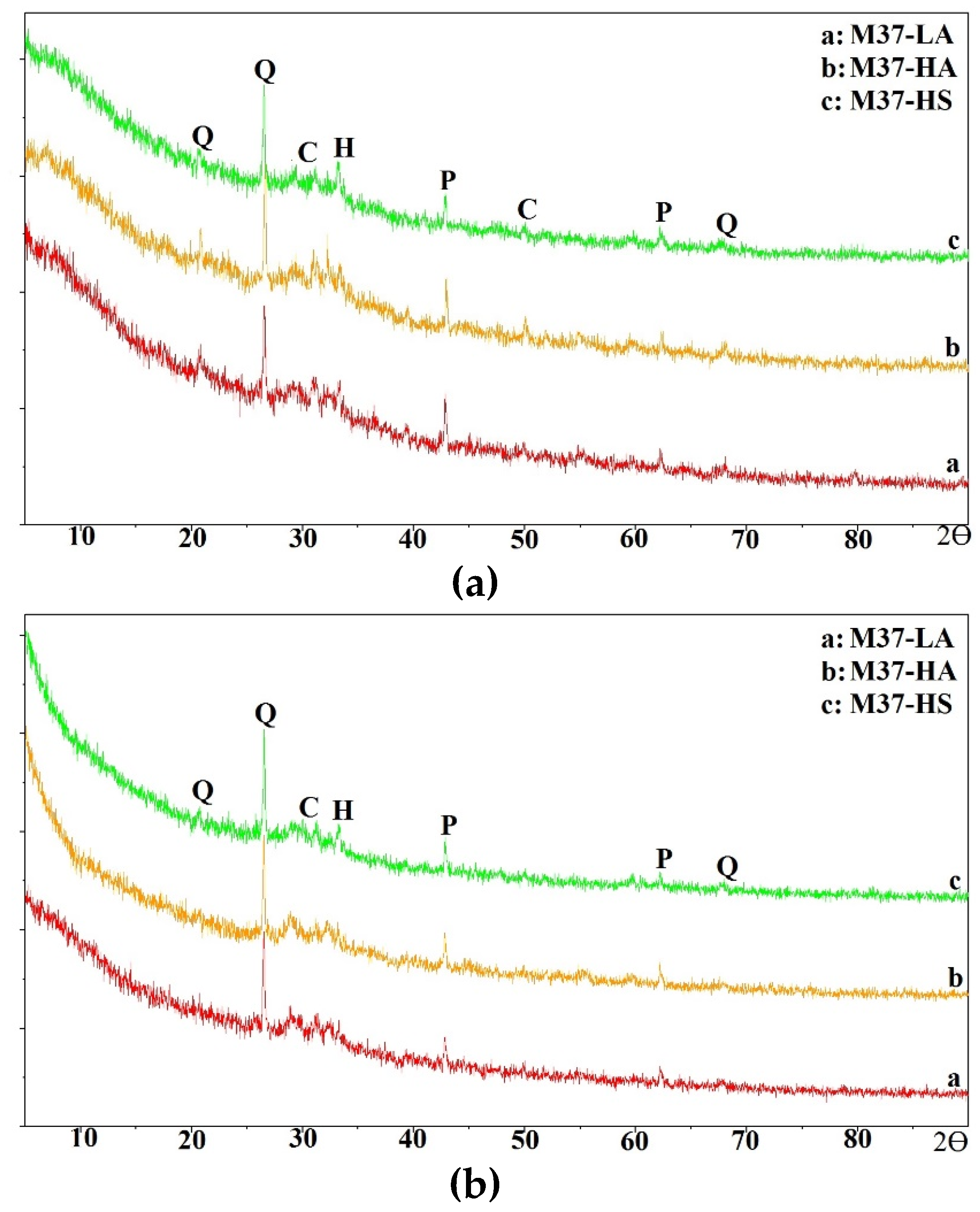

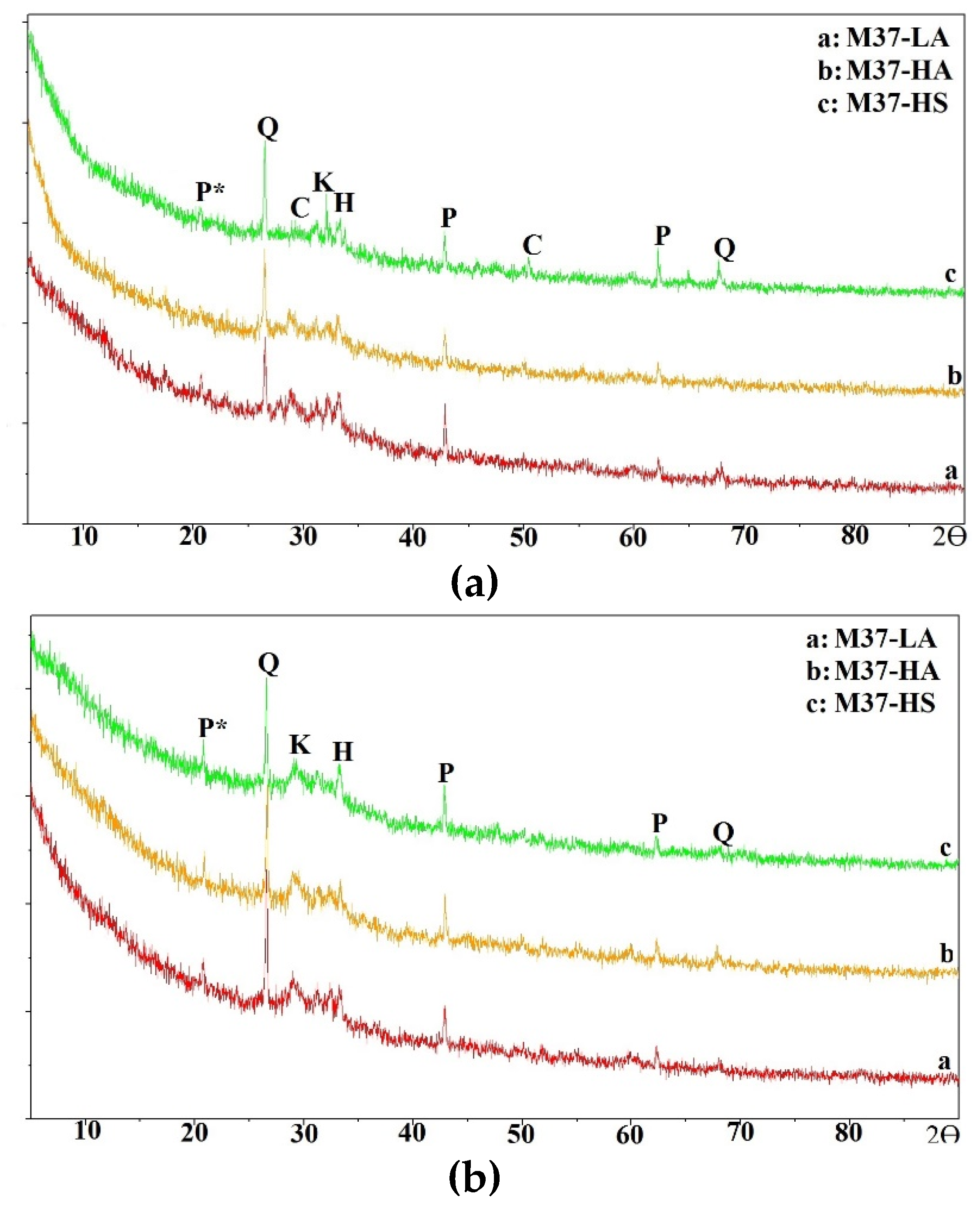

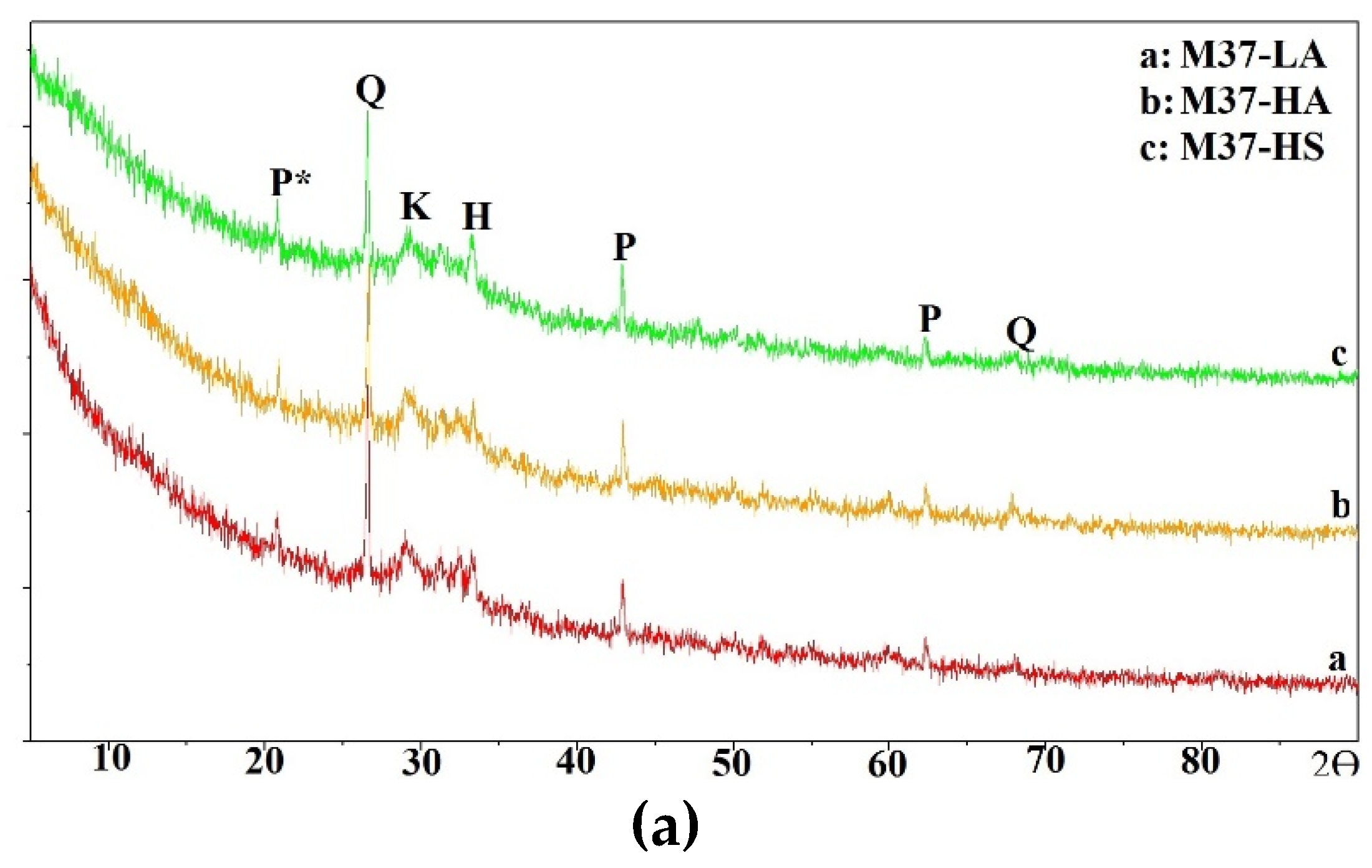

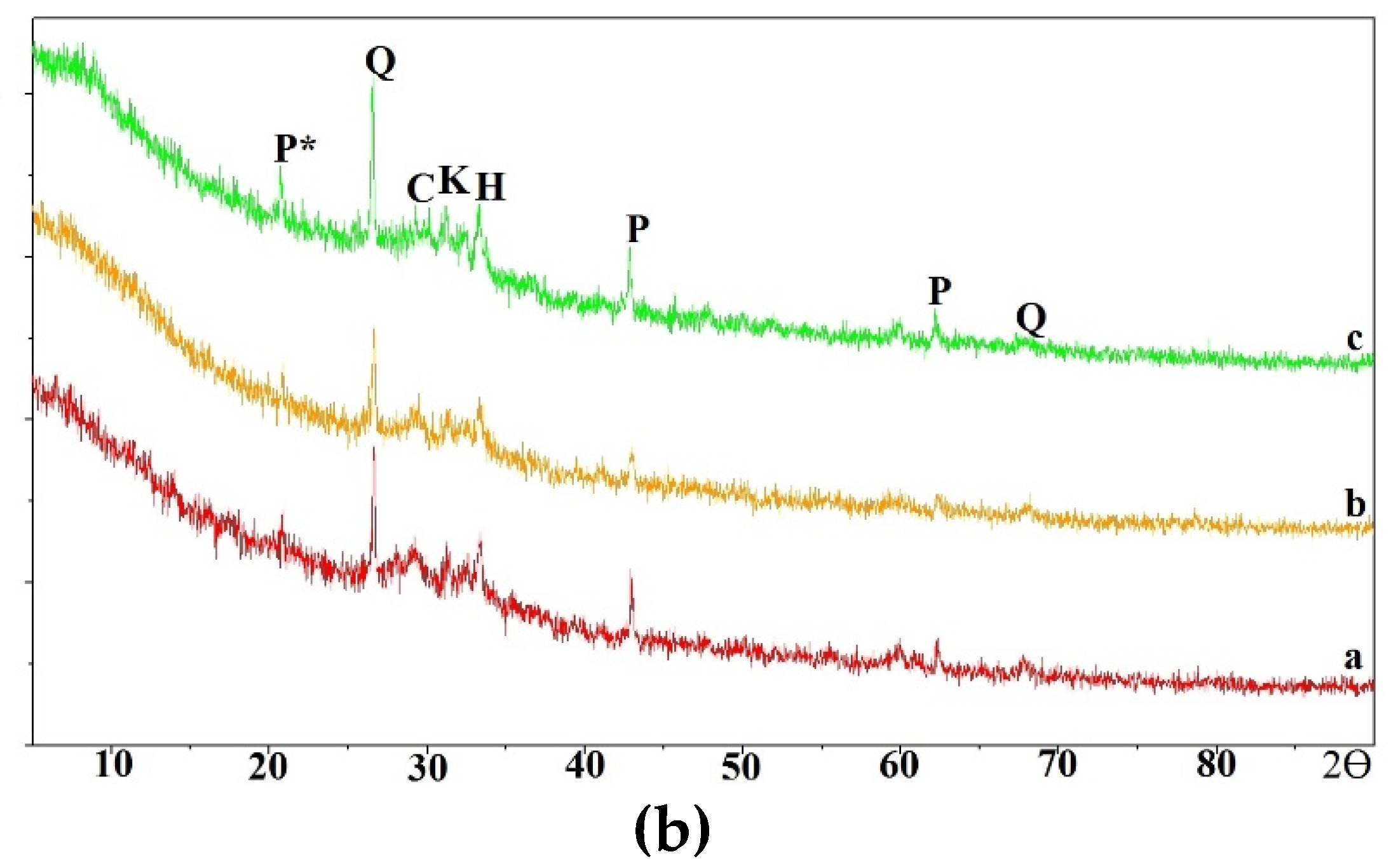

The compressive strength of M37 mortar mixes is summarized in

Figure 8. At 55° C (131° F) of oven curing, for one-part mixing, the compressive strength of mix M37-HS was less than 0.55 MPa (80 psi) after the first eight hours of curing, then consistently increased to reach up to 17.2 MPa (~2500 psi) after 24 hours of curing; while strengths of mixes M37-LA and M37-HA only increased from 13.8 – 14.5 MPa (2000 - 2100 psi) to 17.2 – 20.7 MPa (2500 and 3000 psi) as the duration of curing went from eight to 16 hours, respectively. This represented about 200% strength increase in the case of mix M37-HS; 45% and 25% for mixes M37-LA and M37-HA, respectively.

In the case of corresponding two-part mixing, mix M37-HS demonstrated a high strength from early ages equal to 26.9 MPa (3900 psi) after only eight hours of curing; mixes M37-LA and M37-HA had strengths equal to 23.4 and 22.8 MPa (3400 and 3300 psi), respectively. These strengths were 1.6, 1.7 times greater than the one-part mixing for mixes LA and HA; and 40 times greater for mix HS, respectively.

When the curing temperature was elevated to 70° C (158° F), the strength of one-part mixes increased considerably especially in the case of mix M37-HS which had a compressive strength of 11.7 MPa (1700 psi) after only eight hours of curing, and 25.5 MPa (3700 psi) after 24 hours; while the strength of mixes M37-LA and M37-HA went from 22.1 – 23.4 MPa (3200 – 3400 psi) to 27.6 – 28.2 MPa (4000 – 4100 psi) as the curing duration increased from eight to 24 hours. This represented a rise in compressive strength on a scale of 1.5 for all three mixes when considering the final strength after 24 hours of curing, as the temperature went from 55 to 70° C (131 to 158° F).

For equivalent two-part mixes cured at the same temperature, all three mixes had high compressive strength from early ages, ranging between 31 MPa (4500 psi) for mix M37-LA and 35.2 MPa (5100 psi) for mix M37-HS after eight hours of curing. Then only a slight increase of about 20% happened as the duration of curing went from eight to 24 hours for these mixes. The final compressive strength of two-part mixes were 1.2 to 1.6 times greater than their corresponding one-part mixes.

FA C37 had the highest calcium content among all the three used FAs, therefore formed products of M37 mixes would essentially be rich in Ca species, which explained their higher ambient strength, as discussed earlier. But as the temperature increases, the leaching of Ca is known to be reduced [

22]. This explained why there wasn’t a major change in strength as the temperature increased from 55 to 70° C (131 to 158° F) in the case of two-part mixes. However, for one-part mixes, the rise in temperature increased the dissolution rate of elements and thus led to higher strength.