Submitted:

22 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

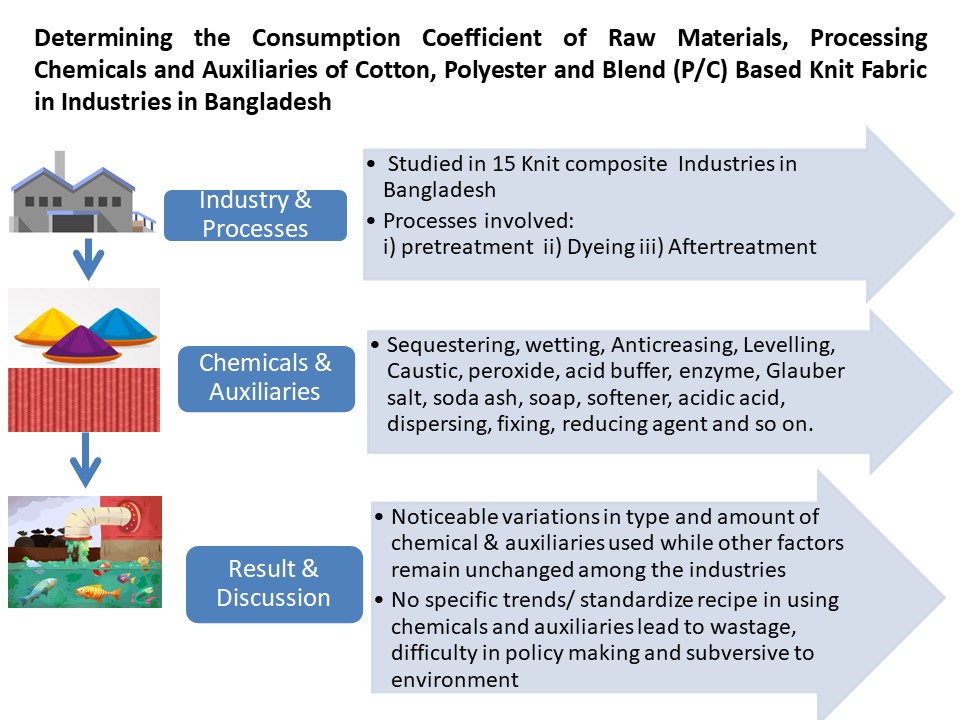

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

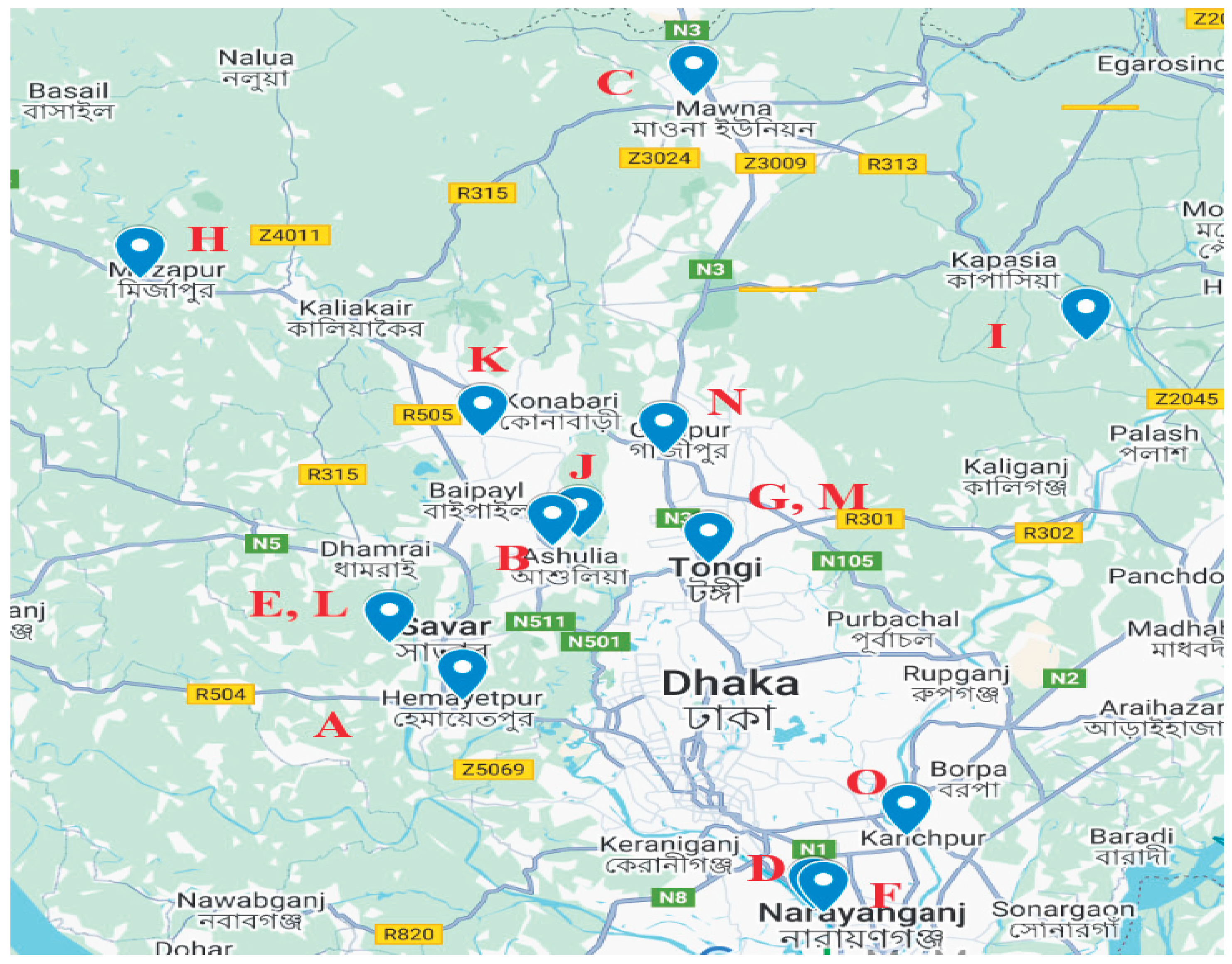

1.1. Study Setting

1.2. Data Collection

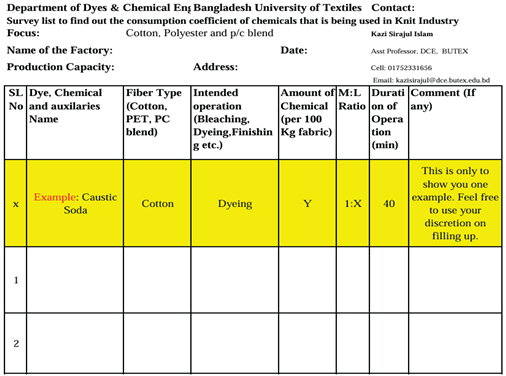

- Production metrics: Fiber composition (Cotton, Polyester, Polyester-Cotton blends)

- Chemical use: Kilograms to treat per 100 kg of fabric, categorized by process stage

- M: L ratios: Expressed as times, interpreted as liquid-to-material ratios (e.g., 1:6)

1.3. Sampling

3. Result and Discussion

Results

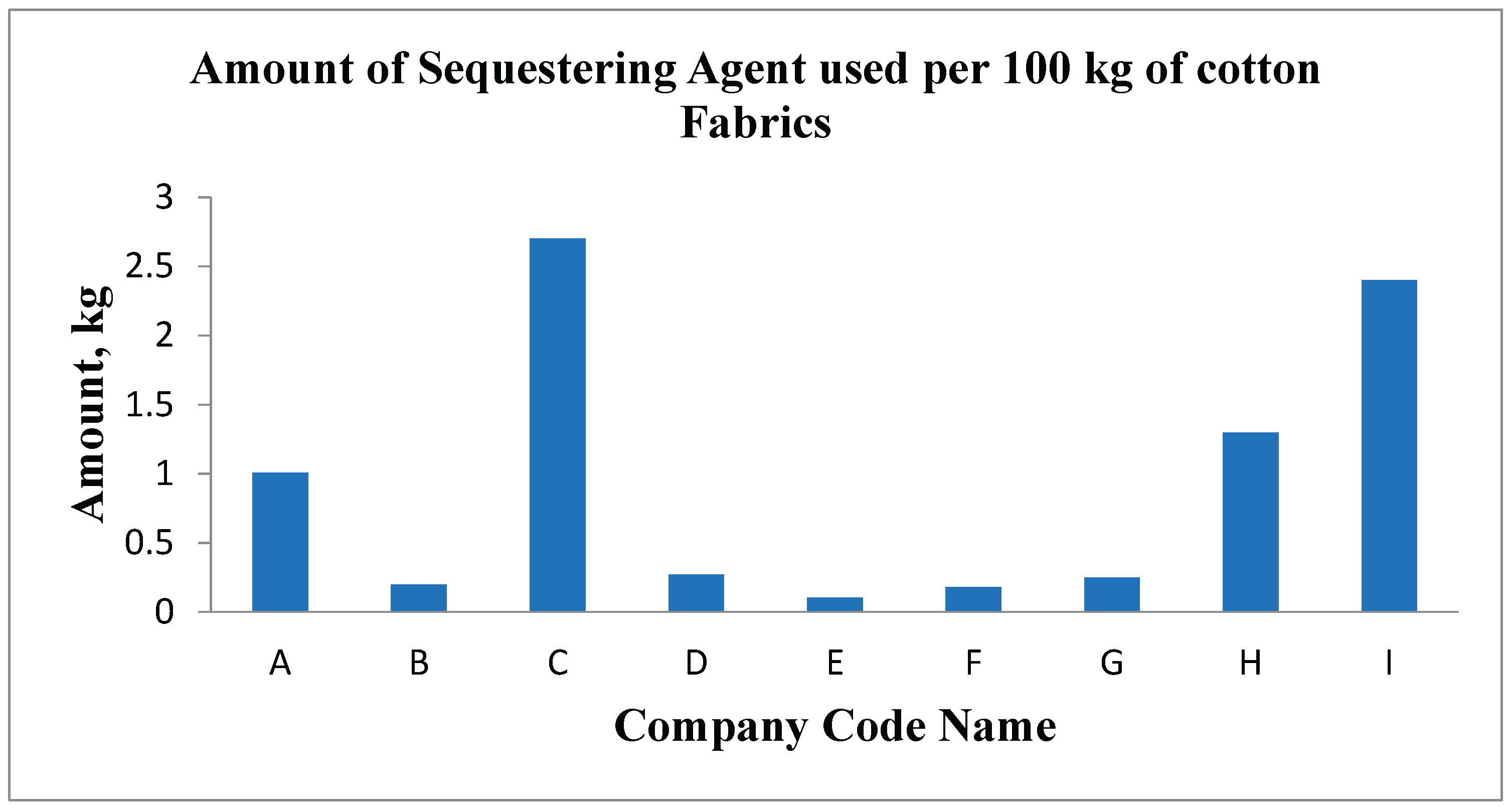

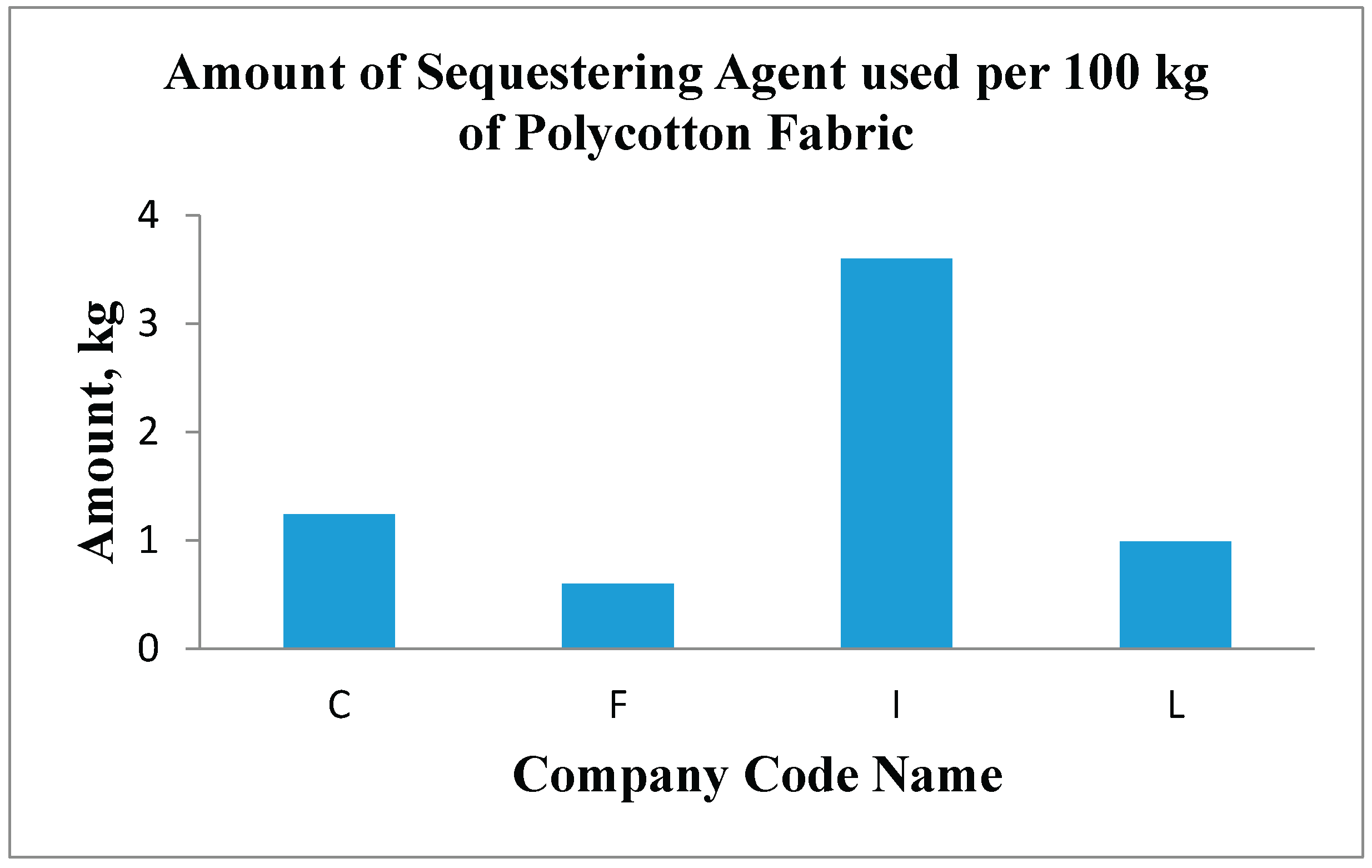

Sequestering Agent

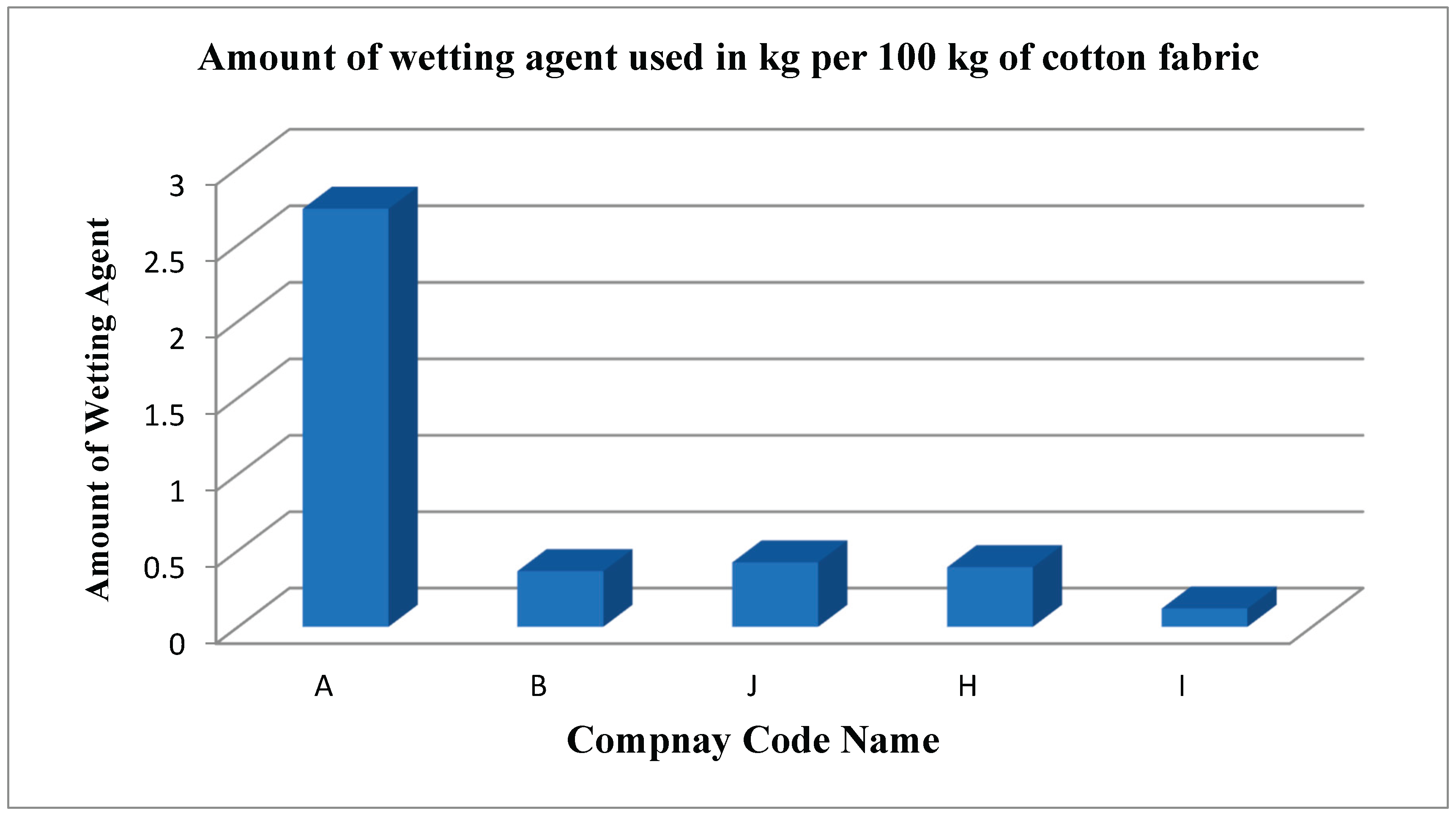

Wetting Agent

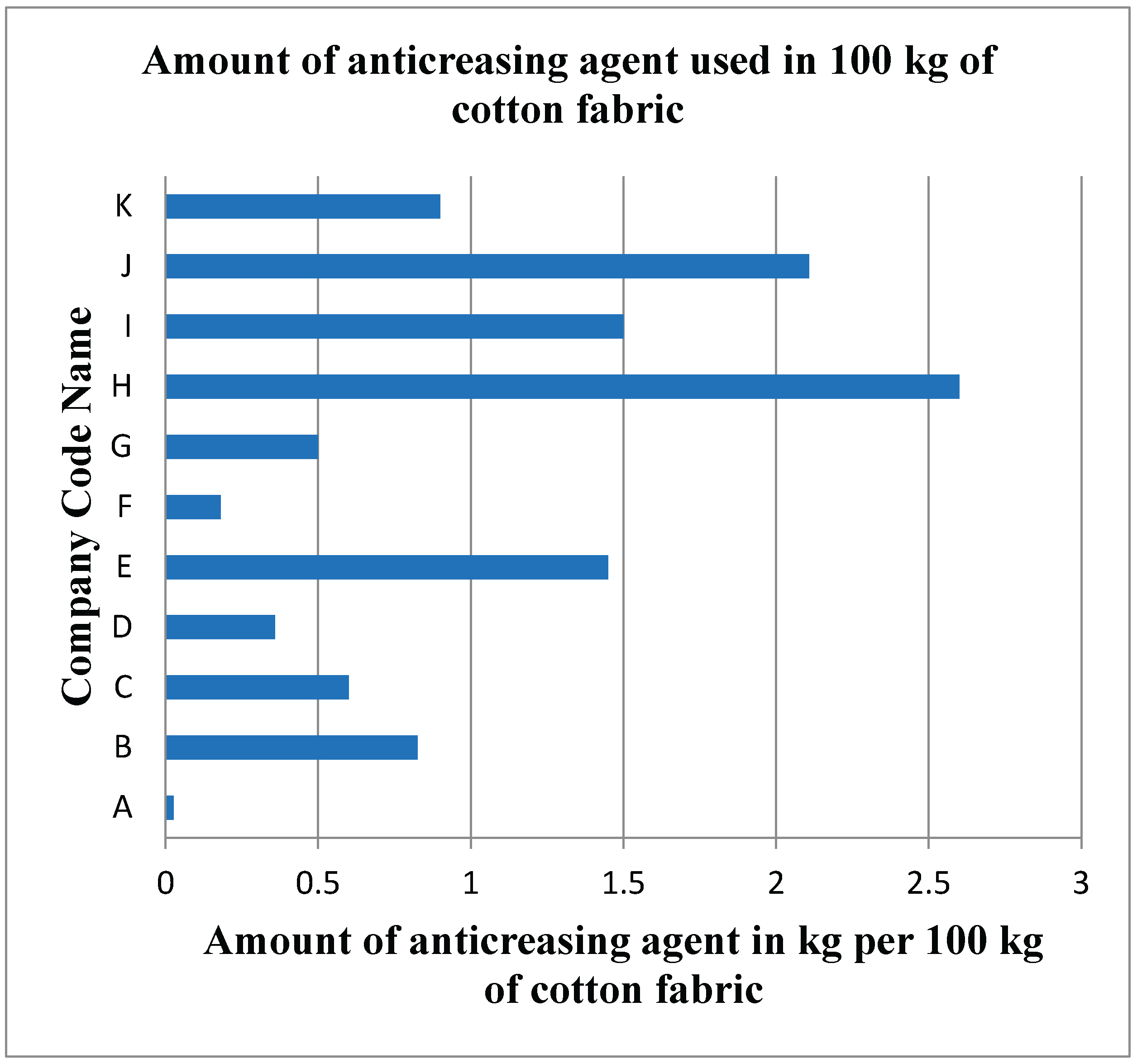

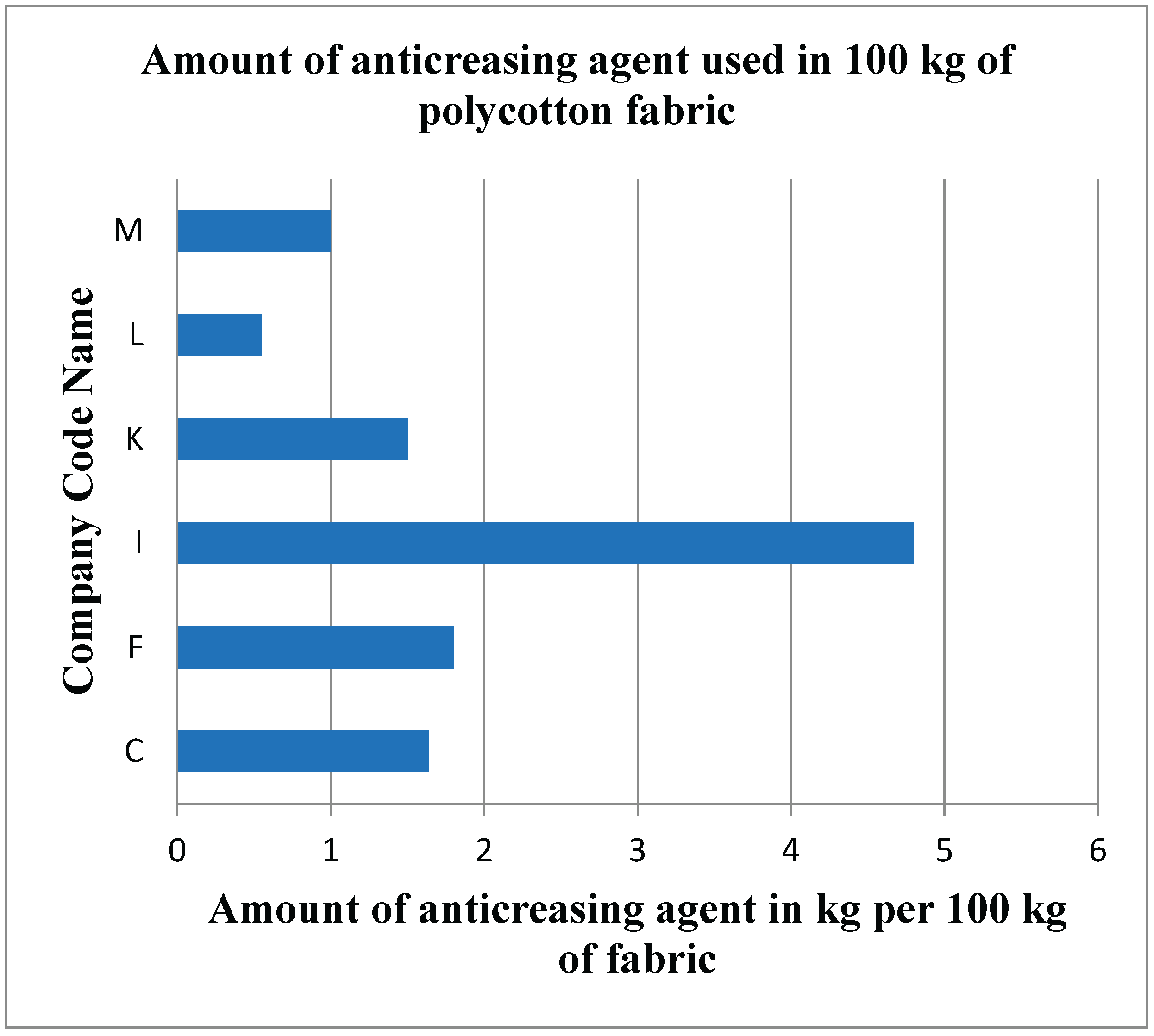

Anticreasing Agent

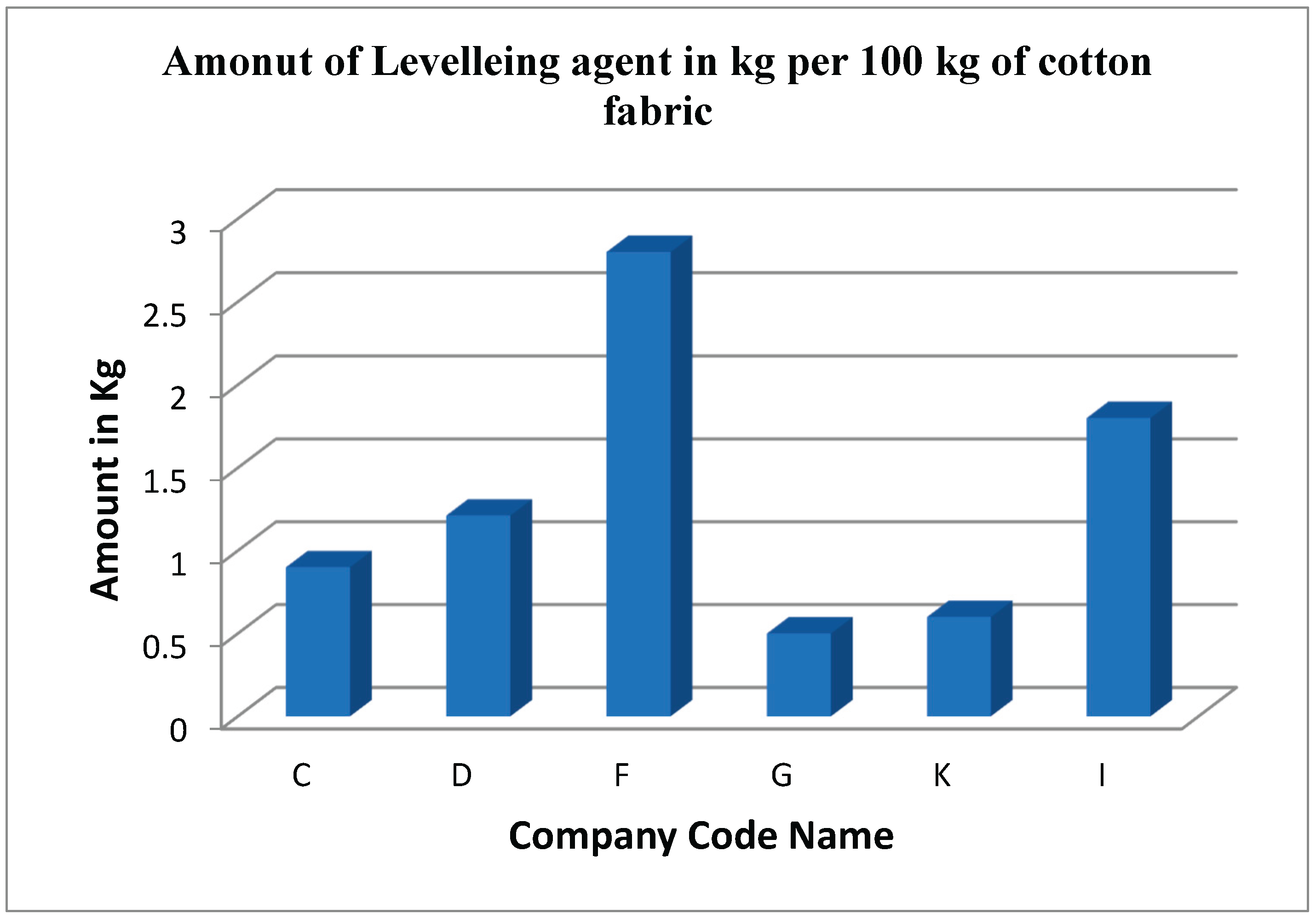

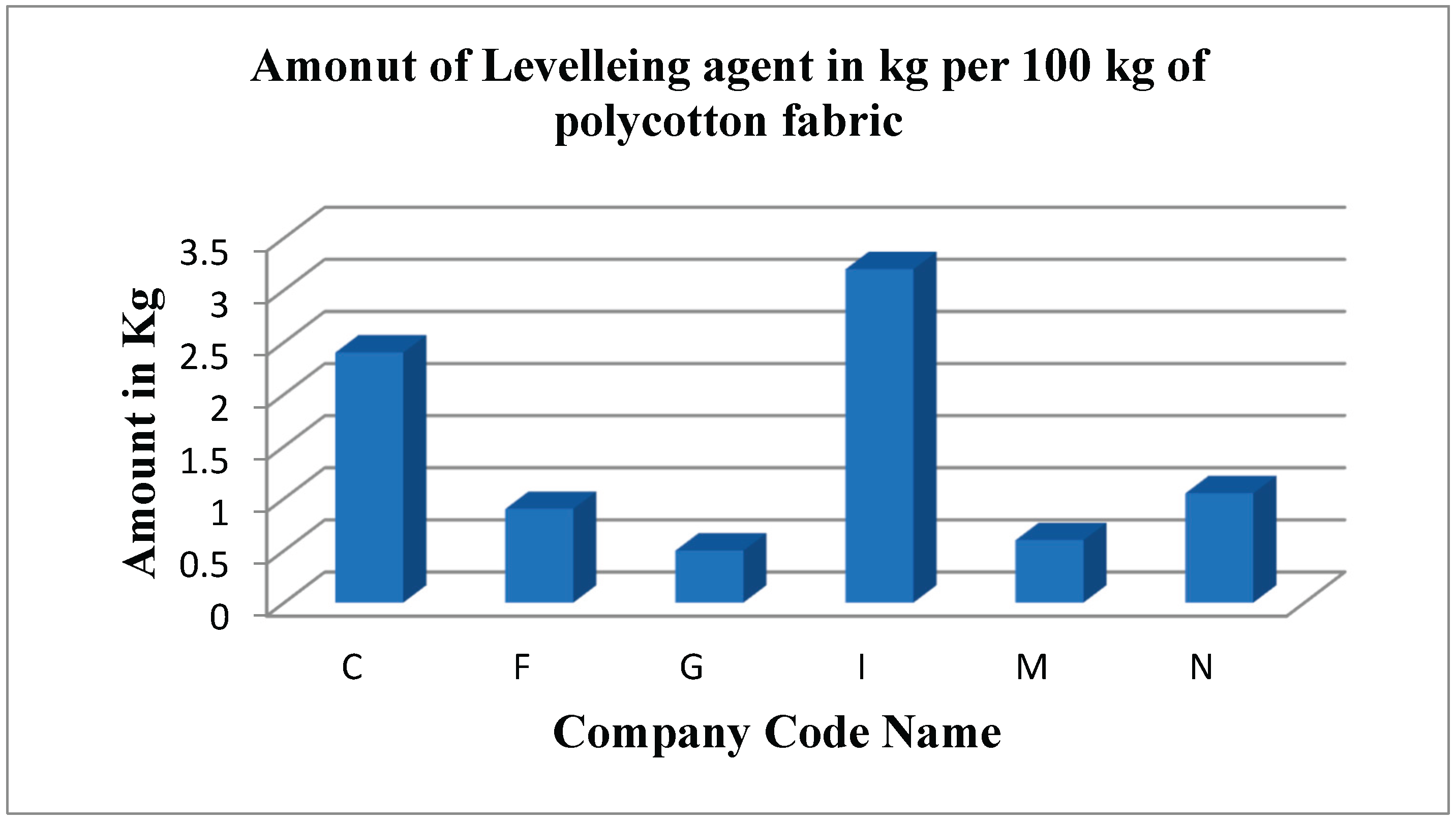

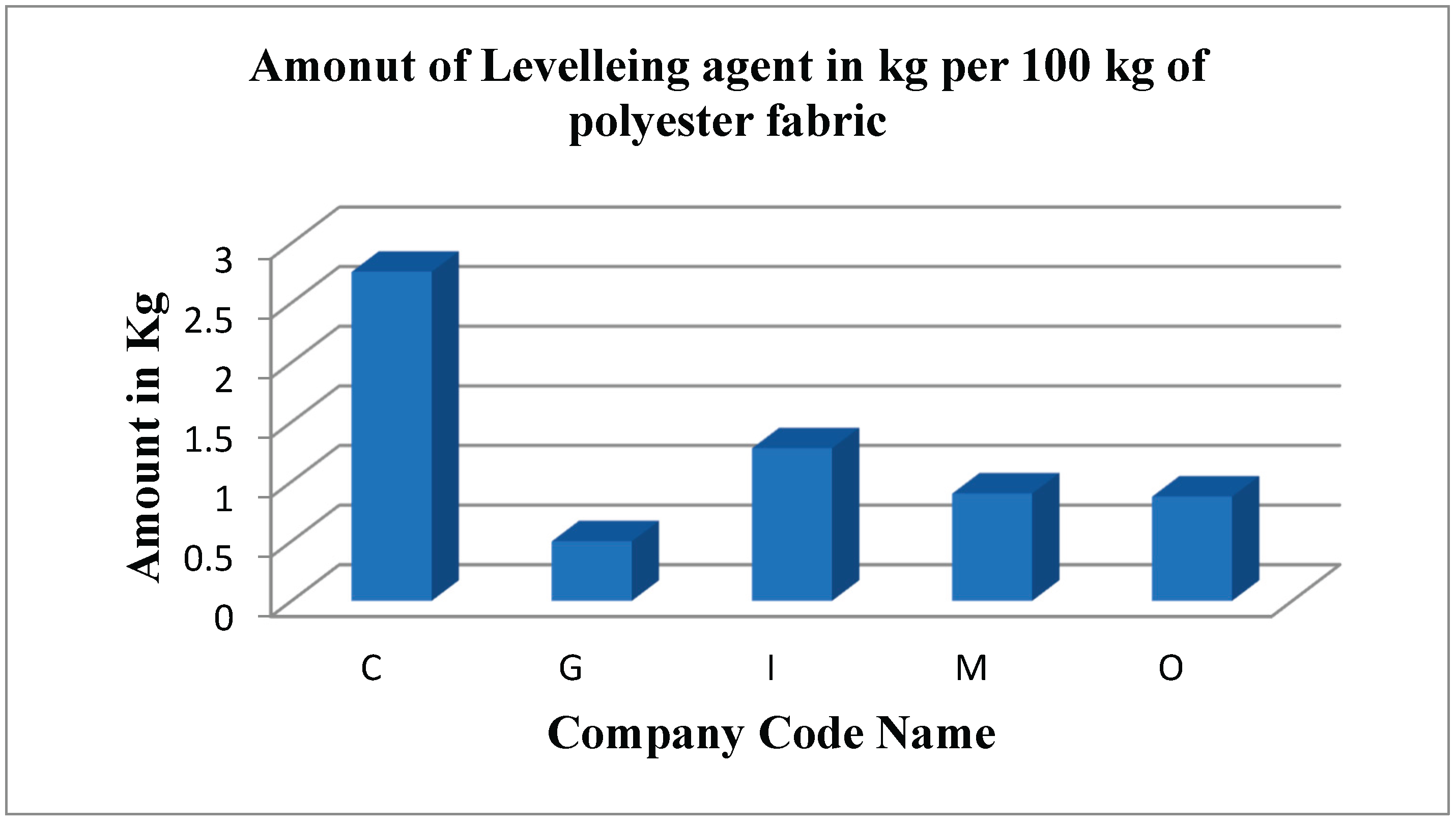

Leveling Agent

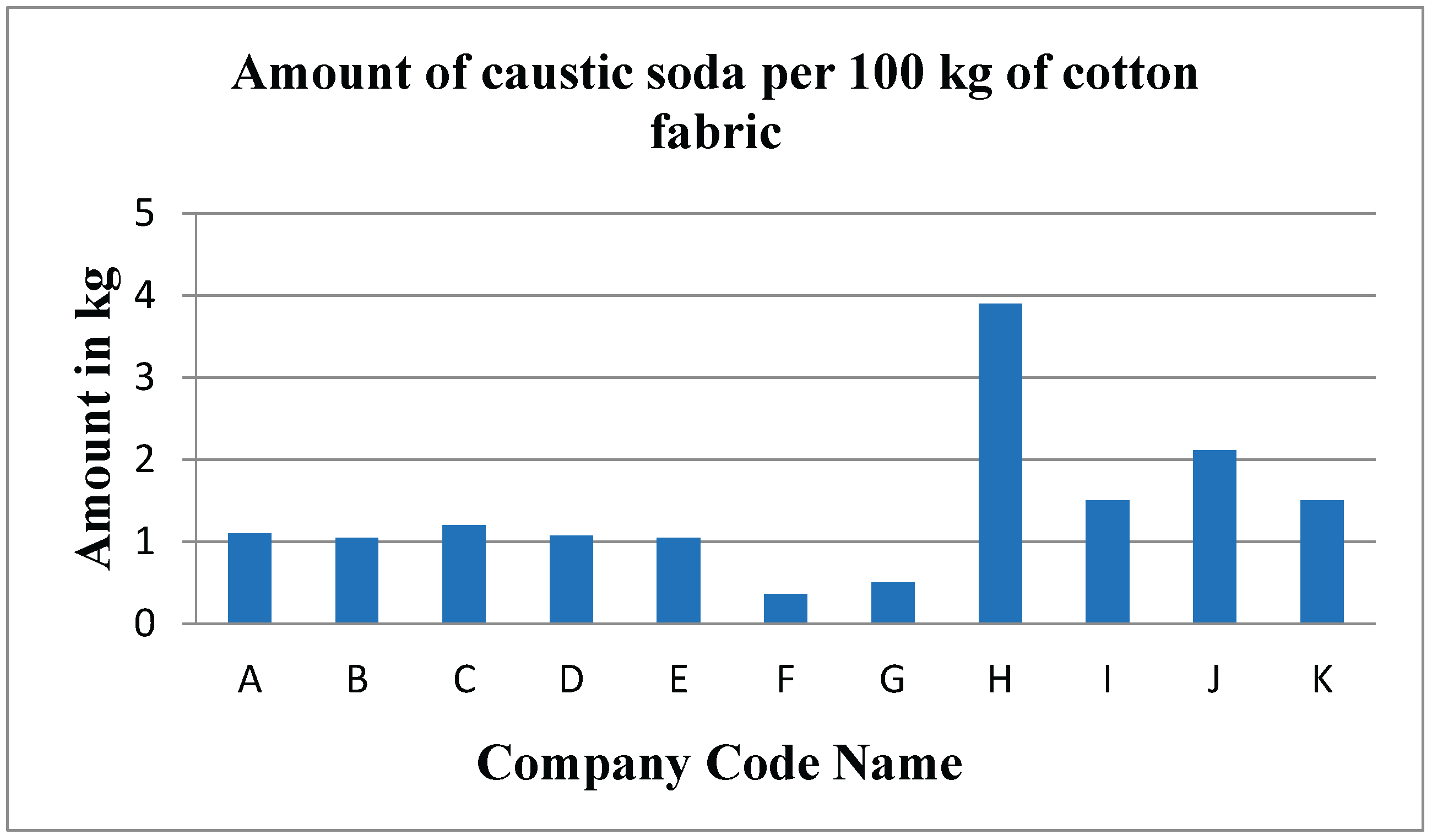

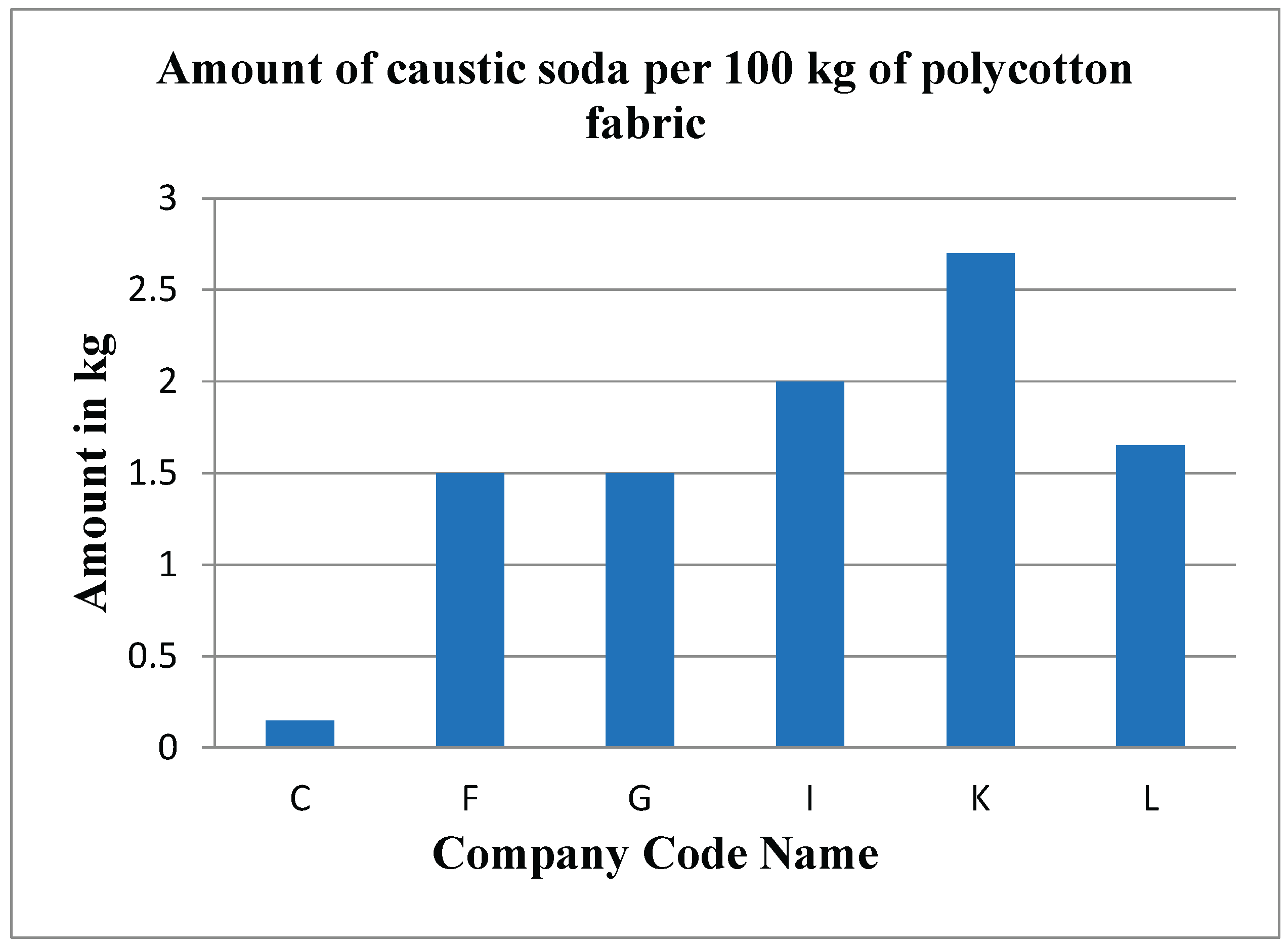

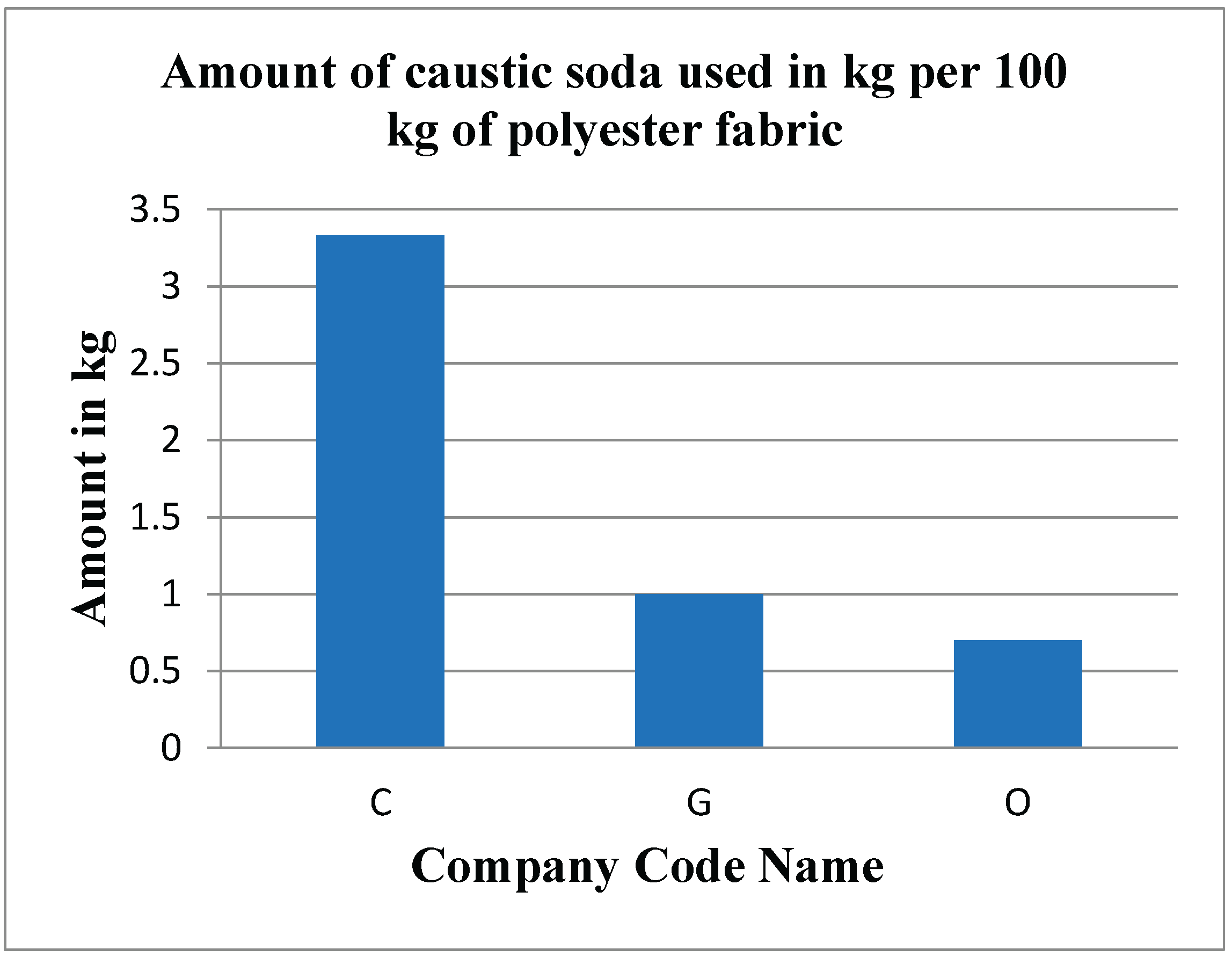

Caustic Soda

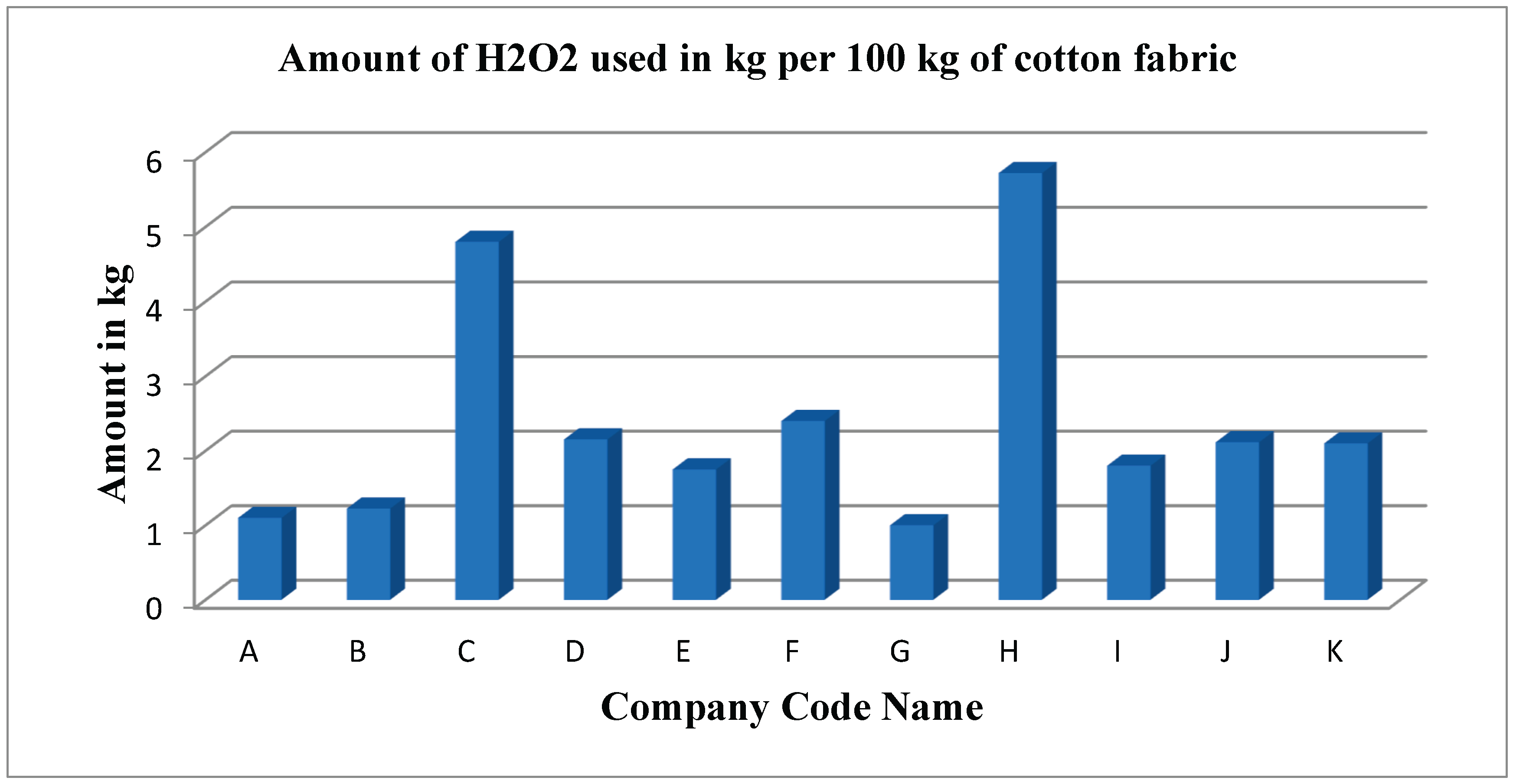

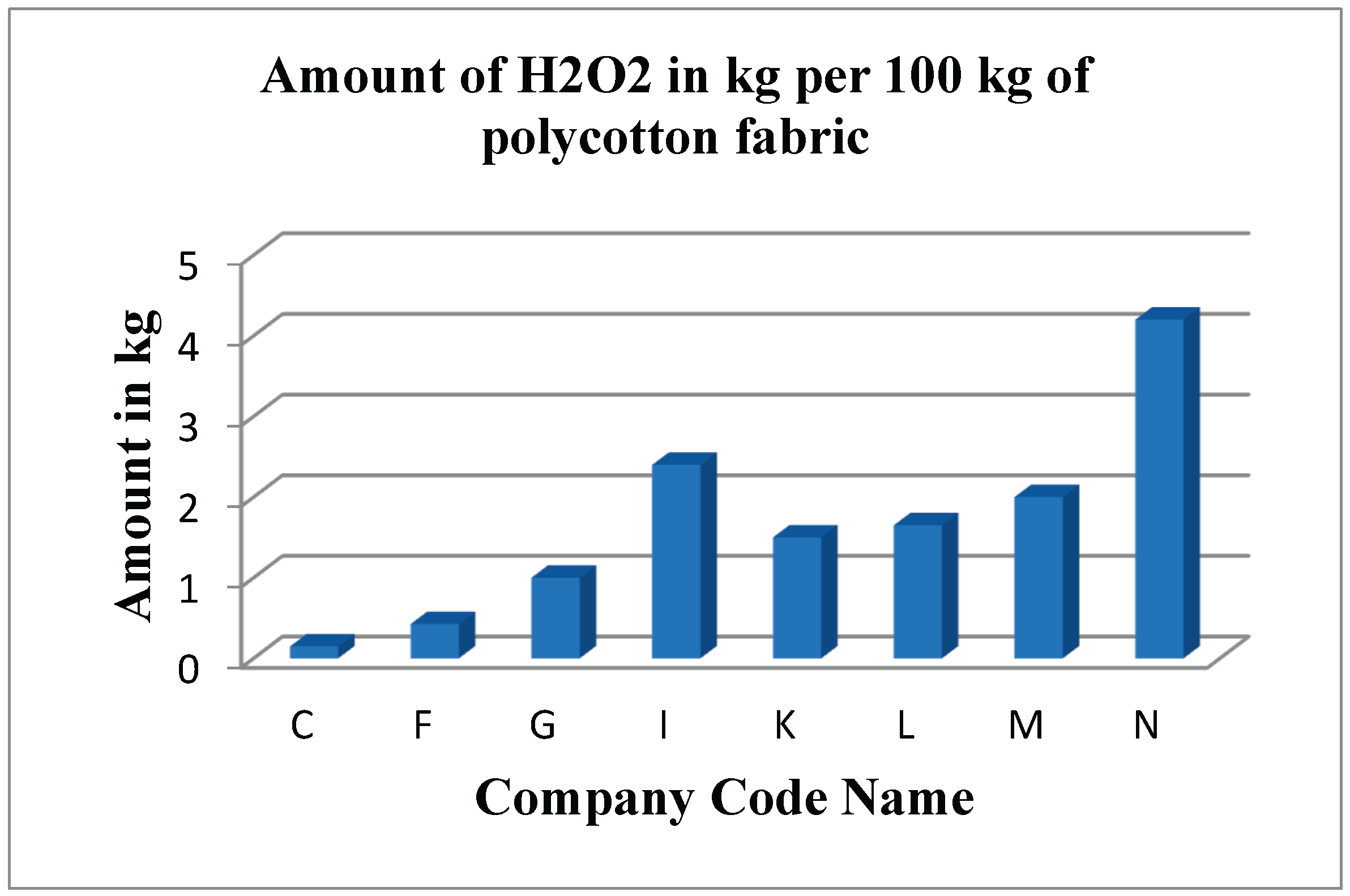

H2O2

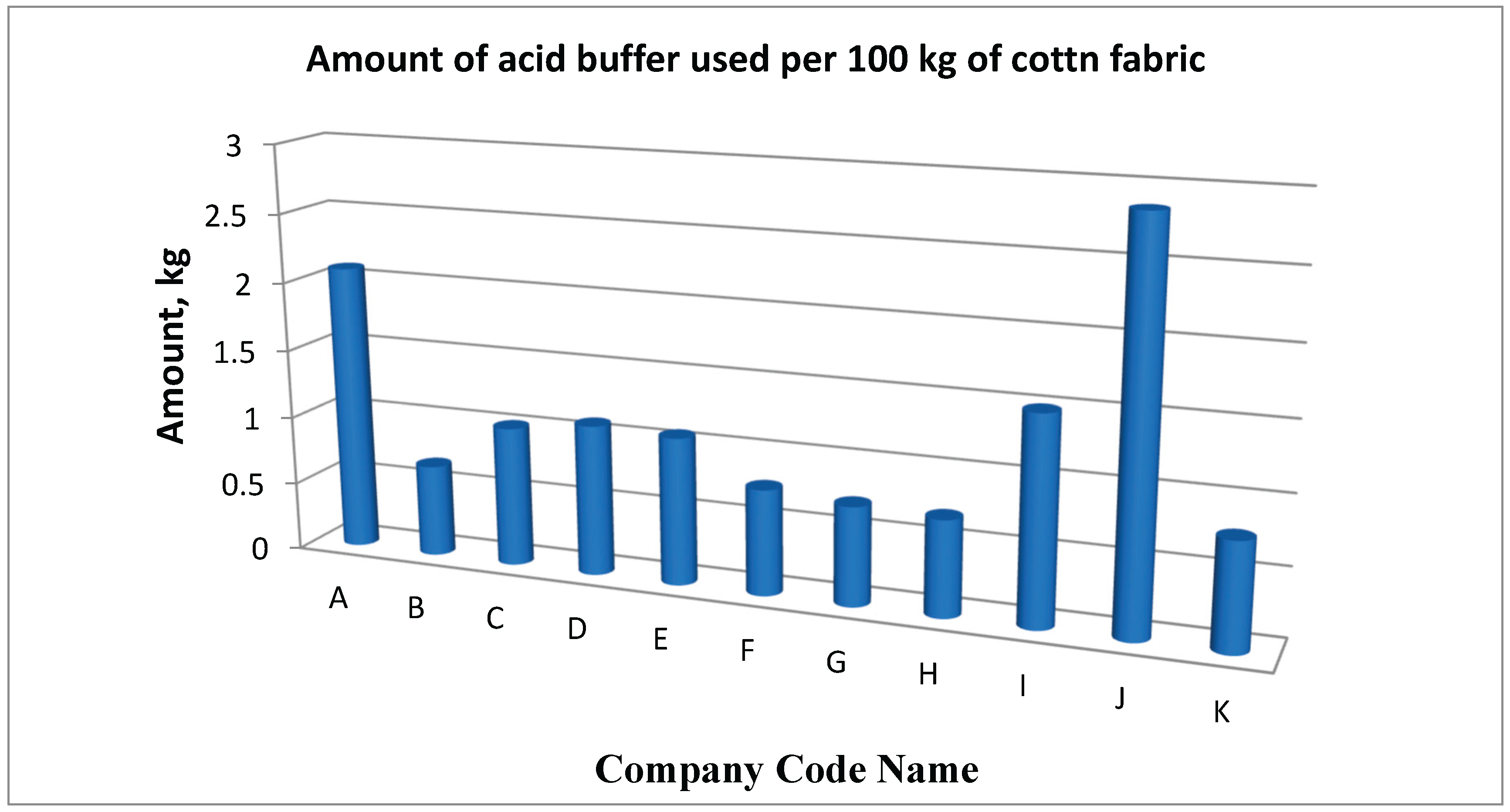

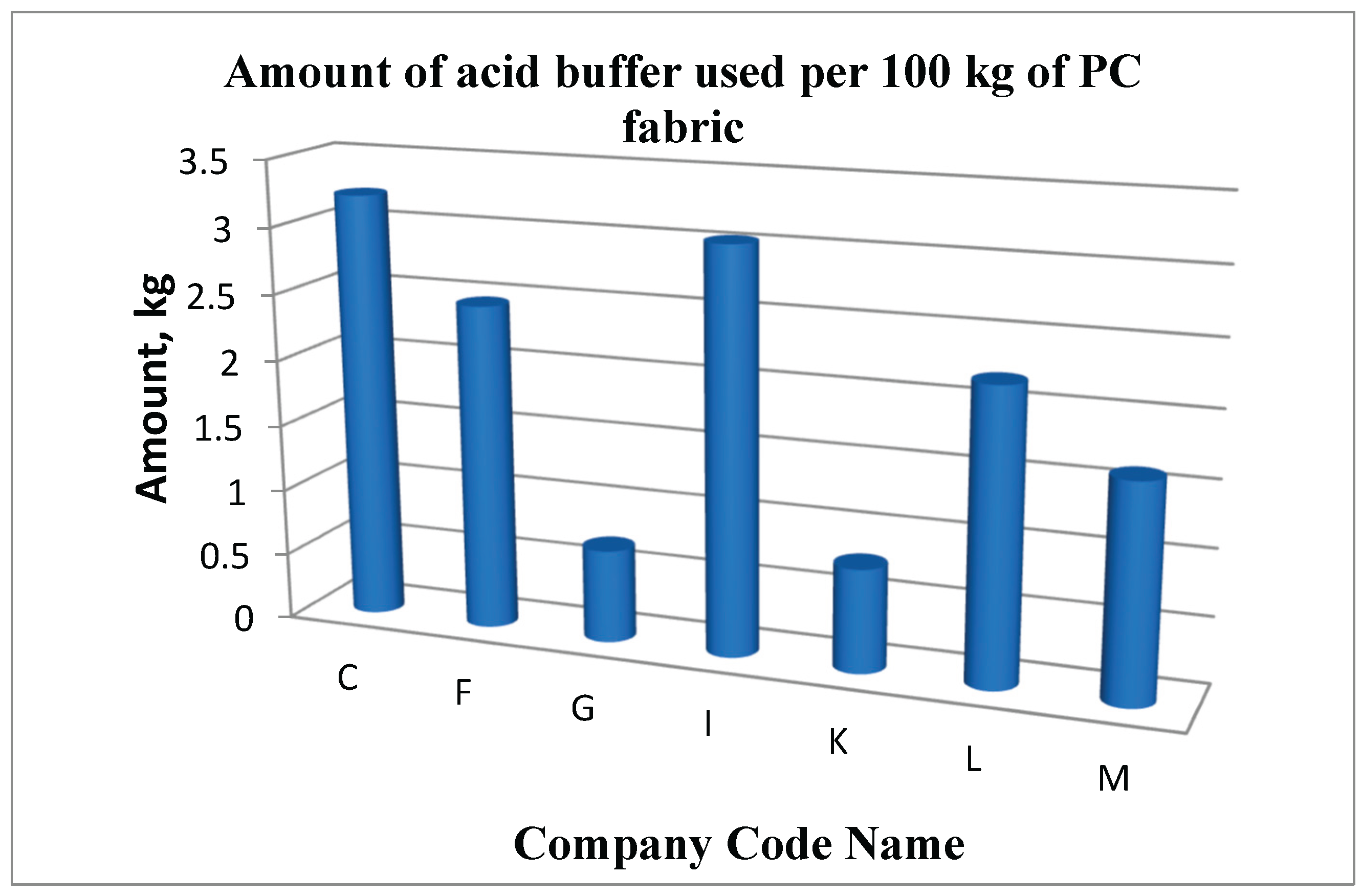

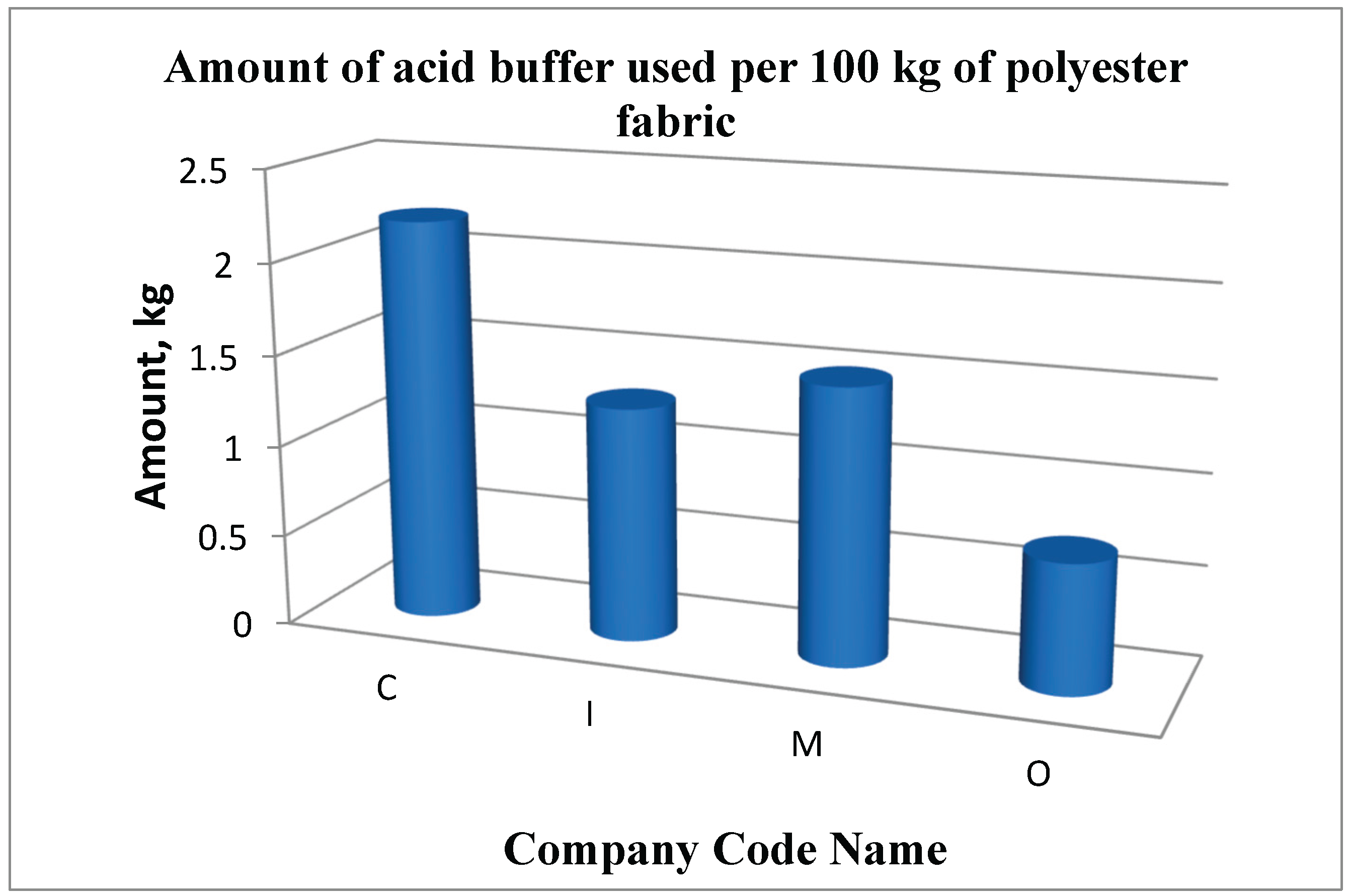

Acid Buffer

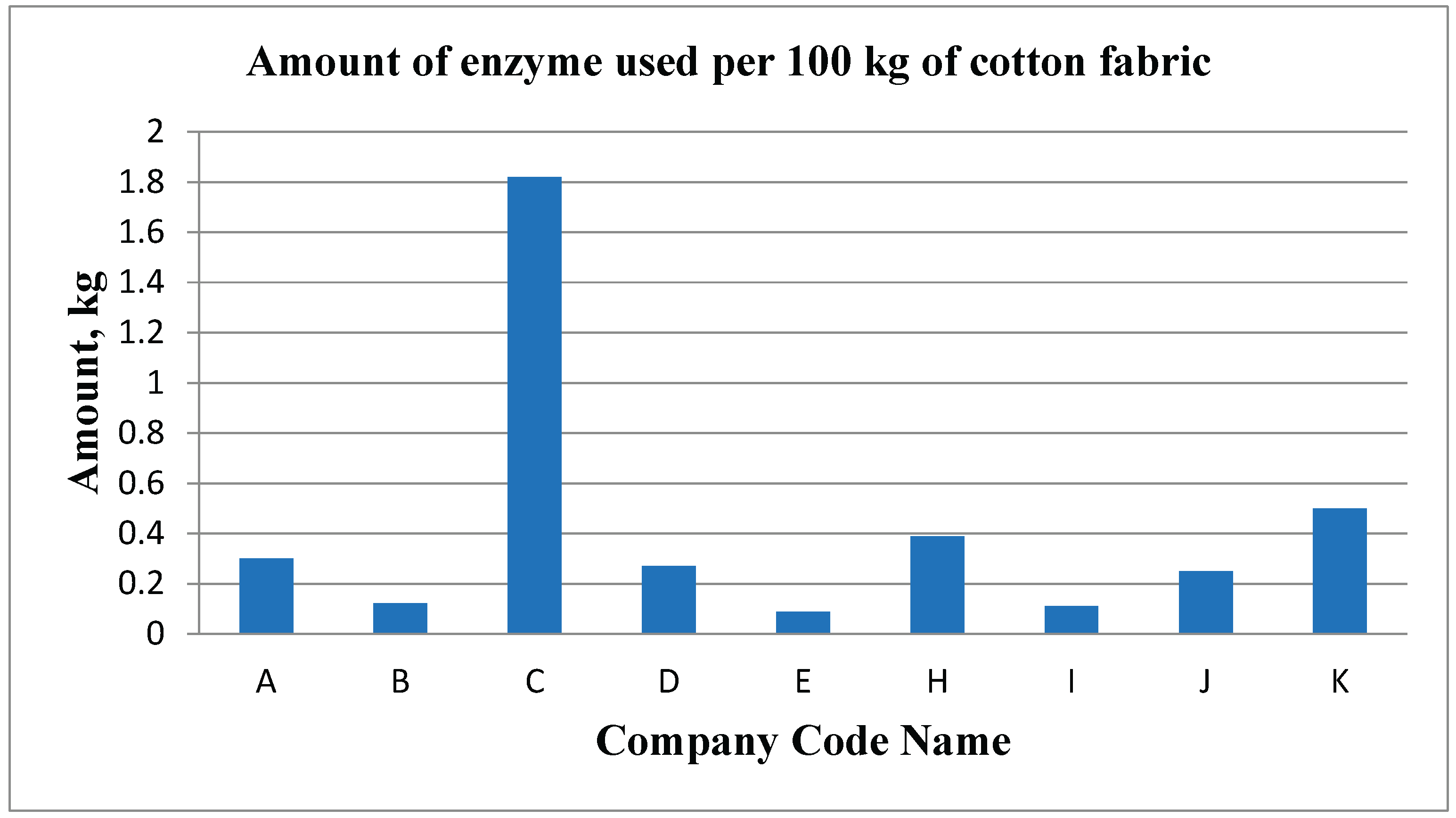

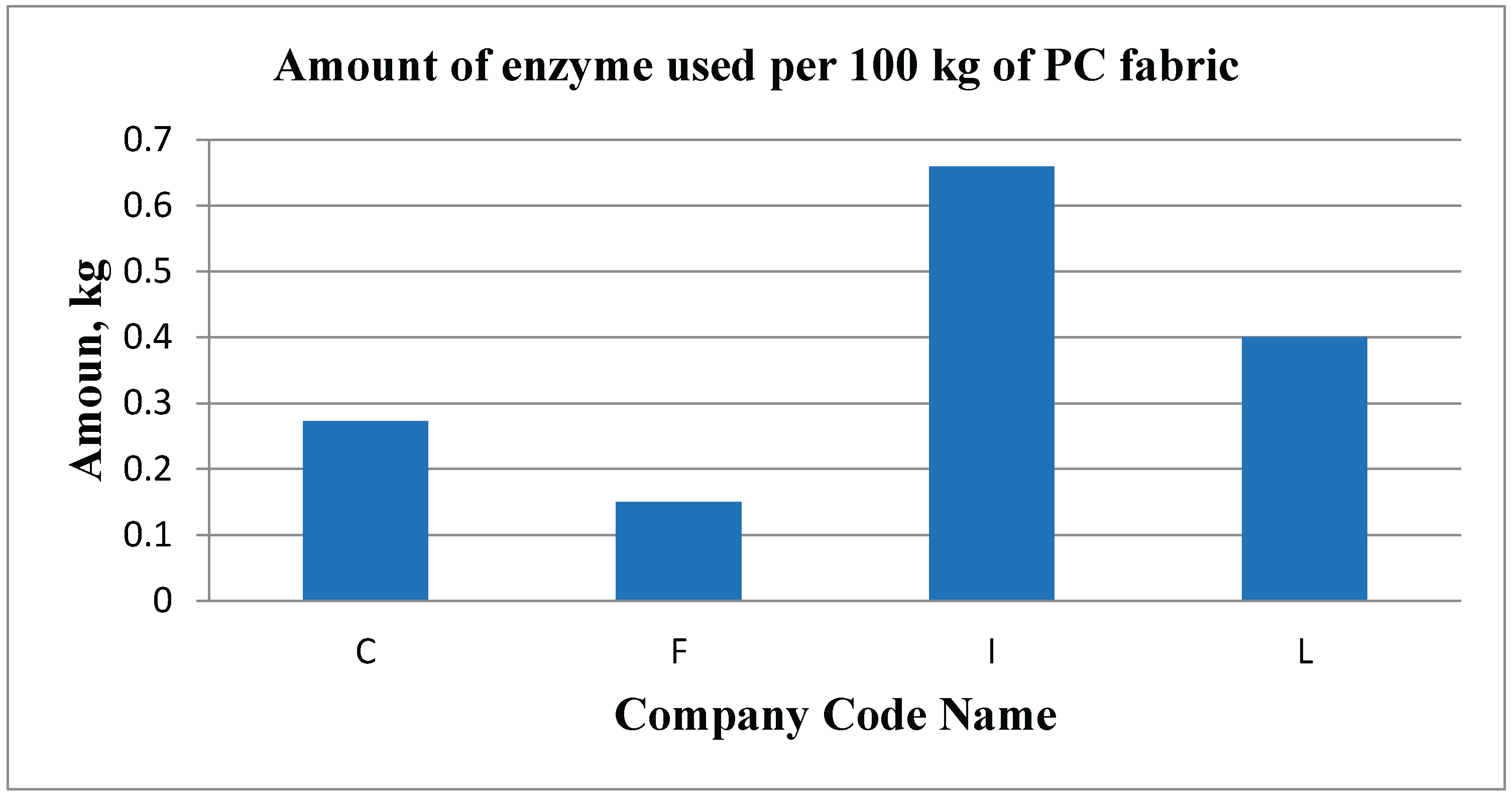

Enzyme

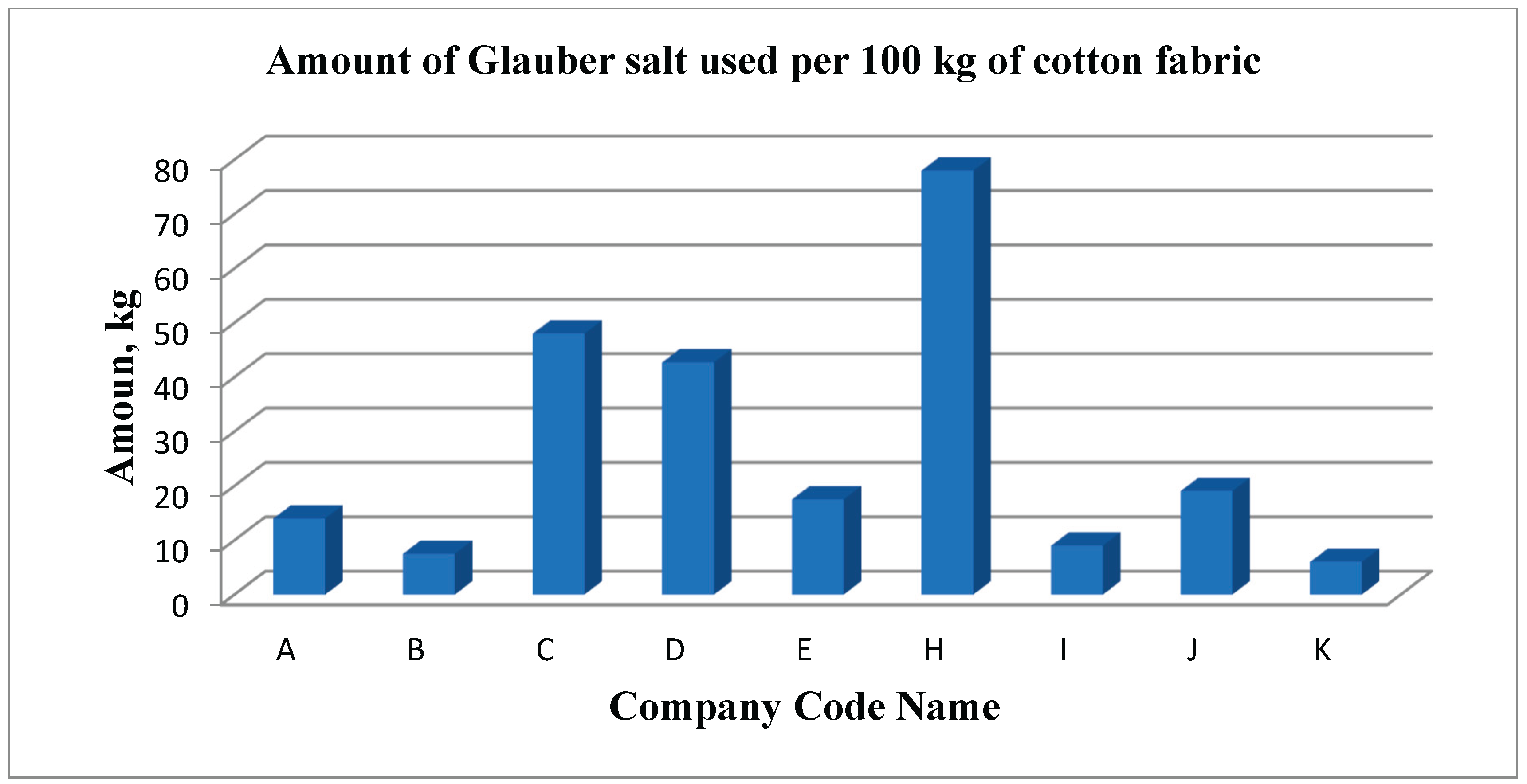

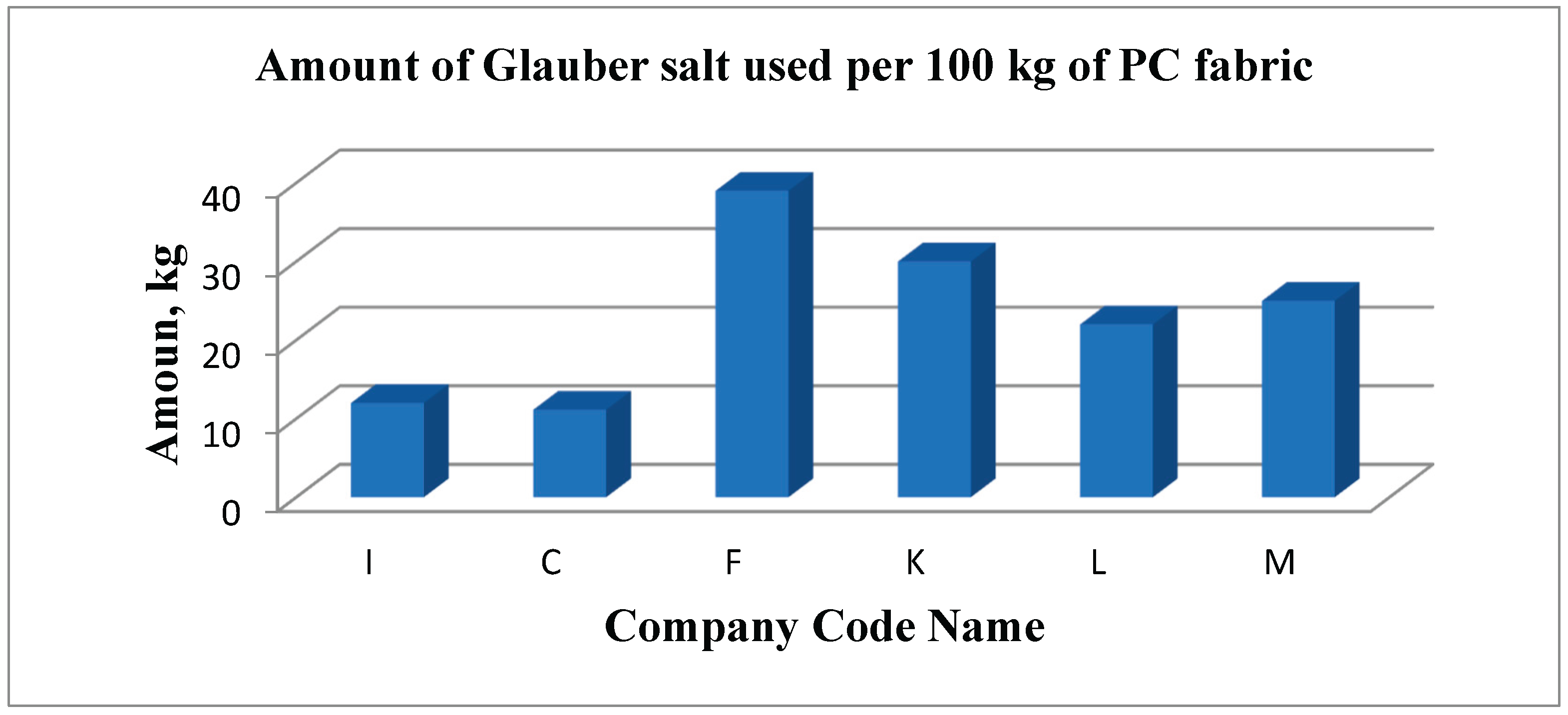

Glauber Salt

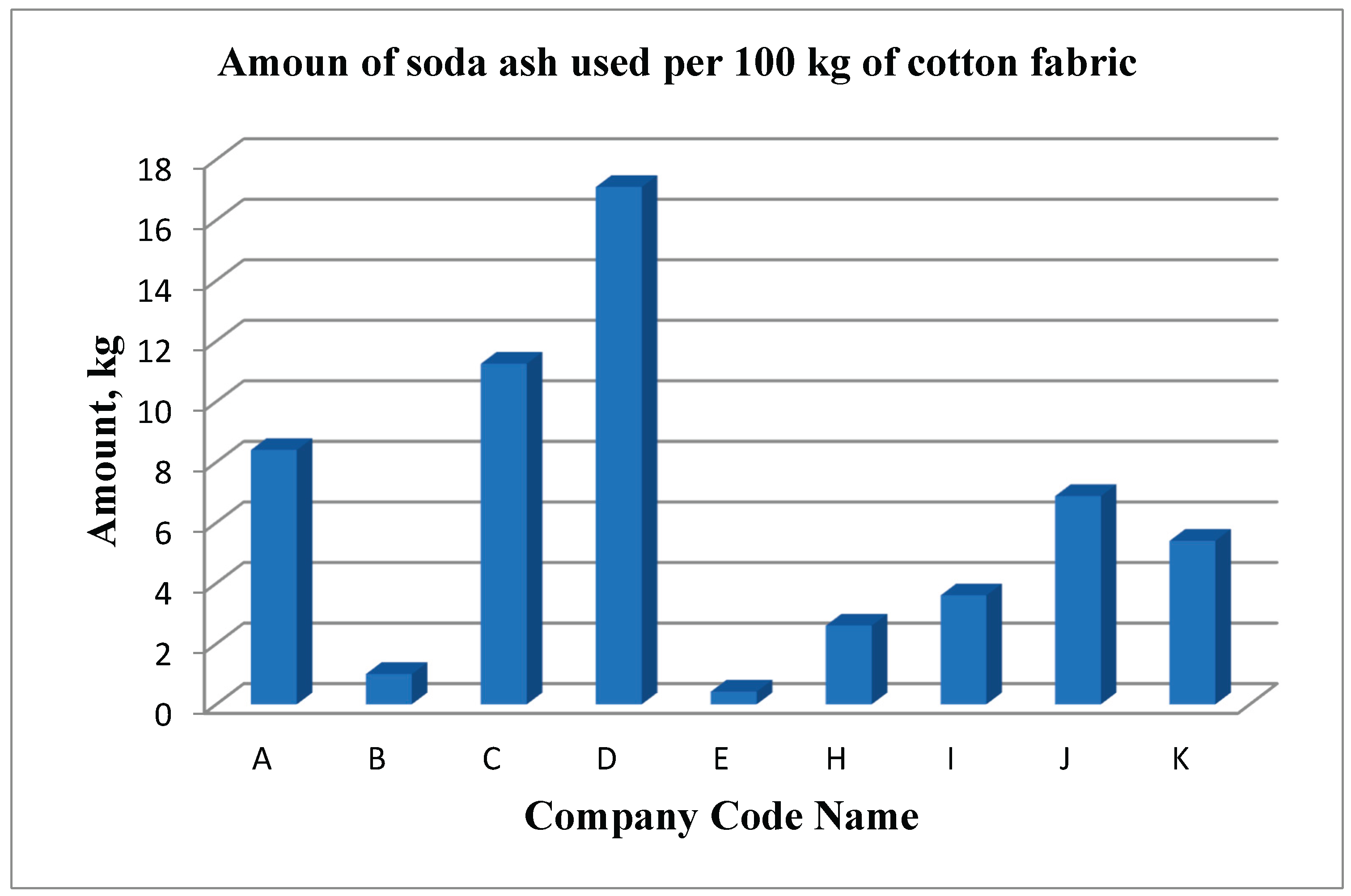

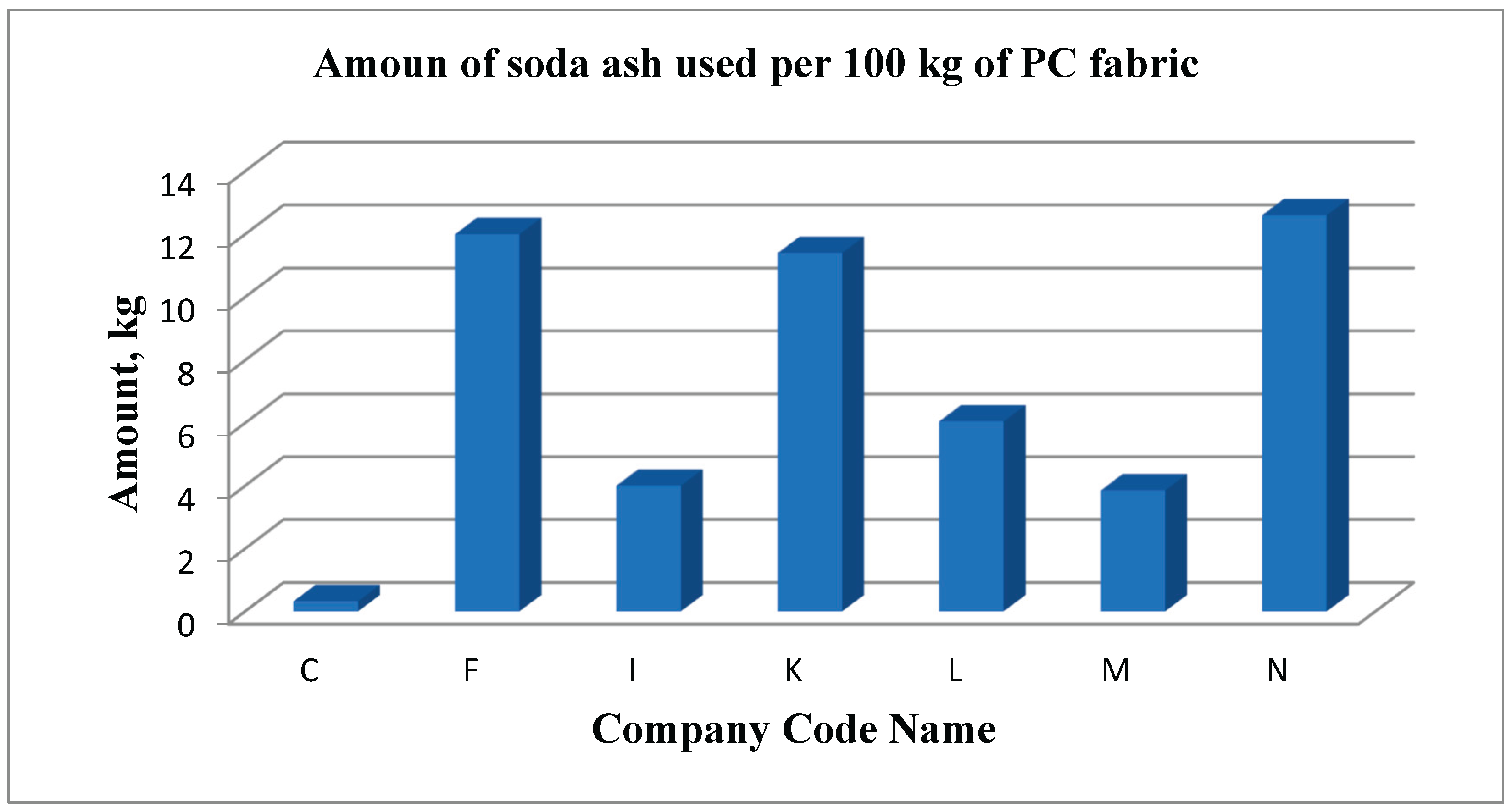

Soda Ash

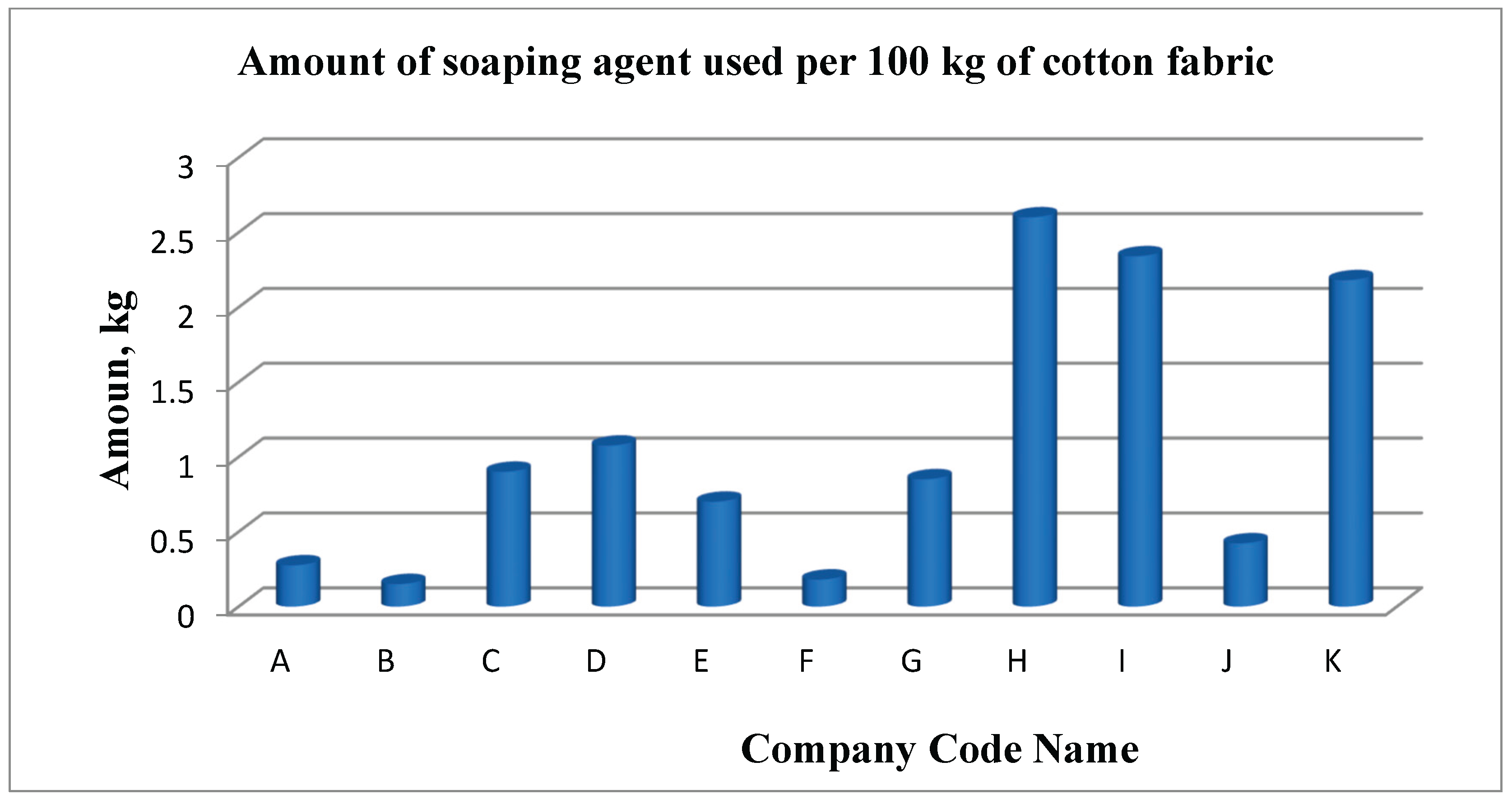

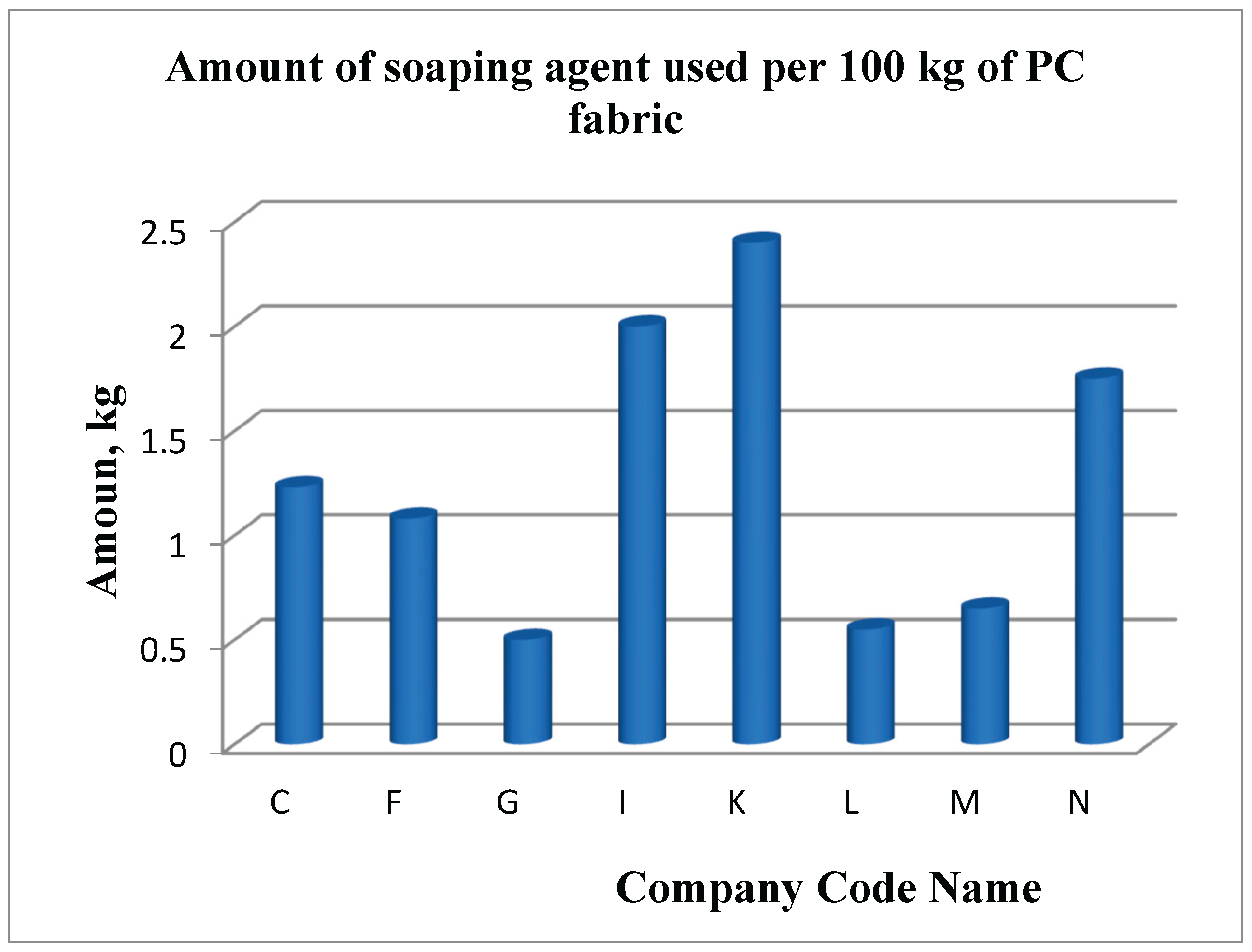

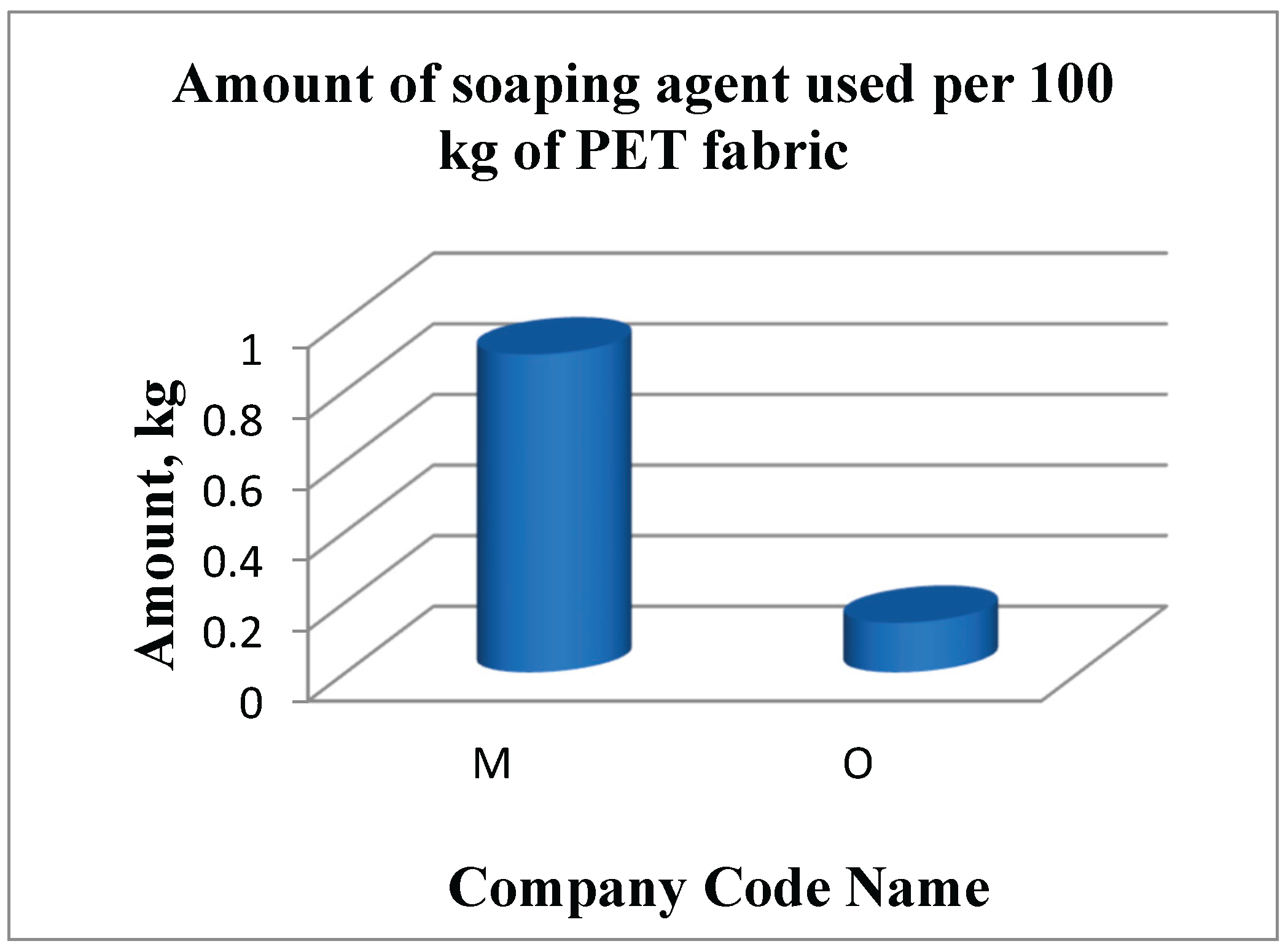

Soaping Agent

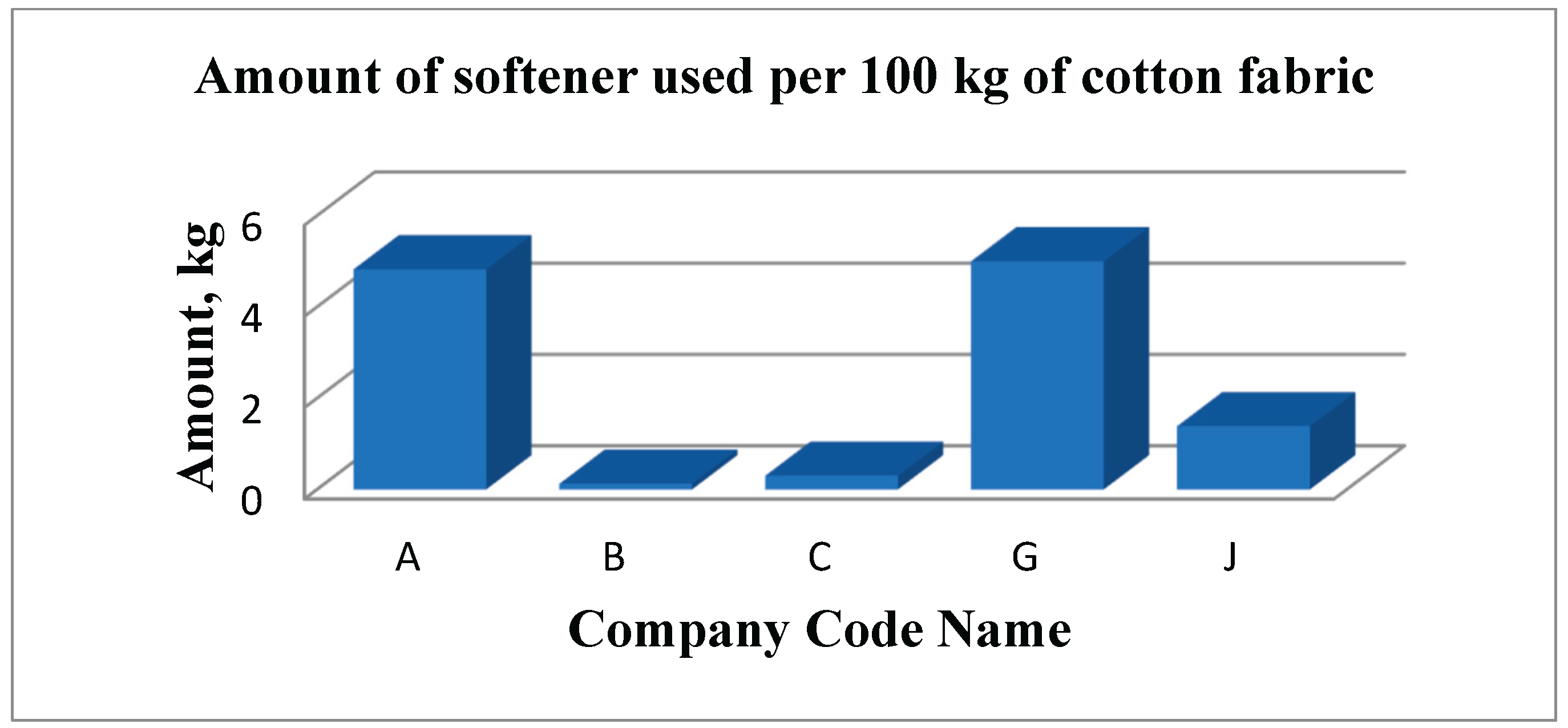

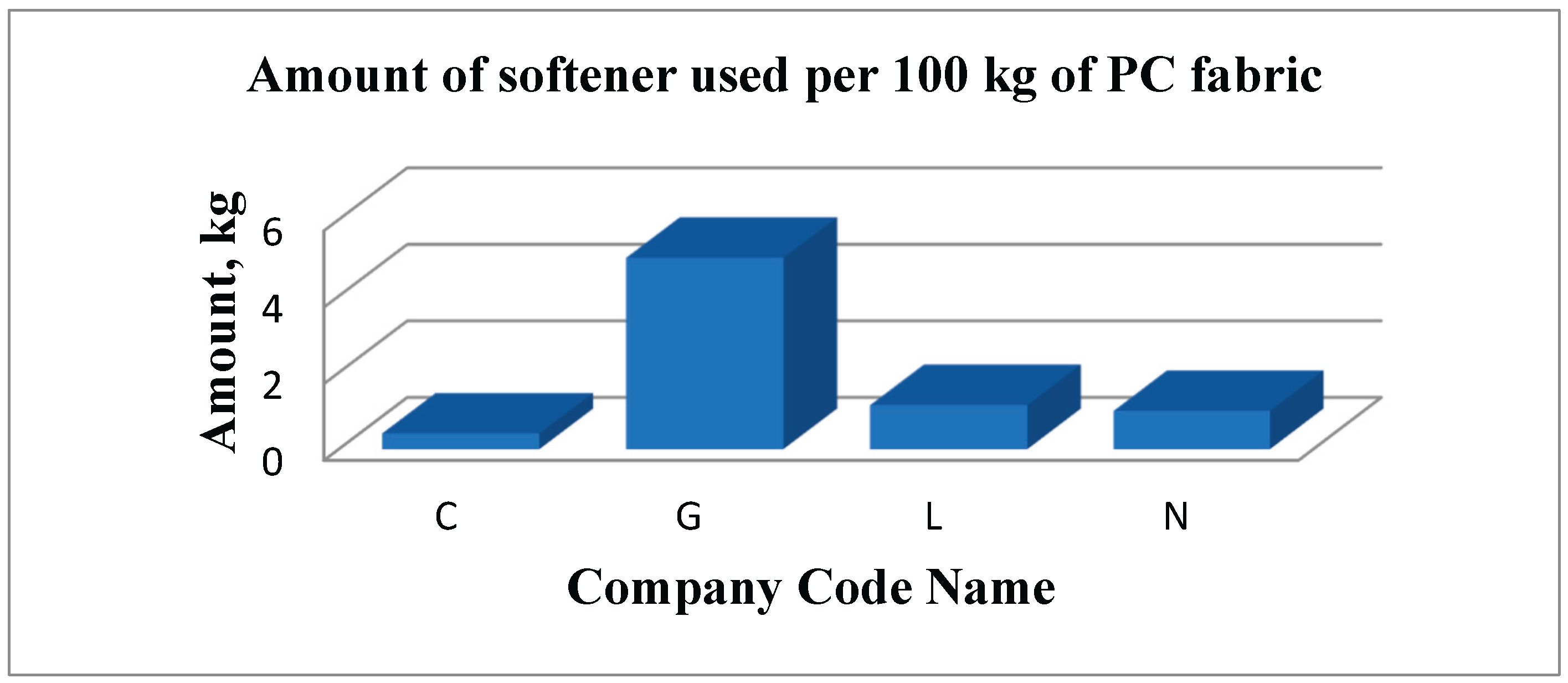

Softener

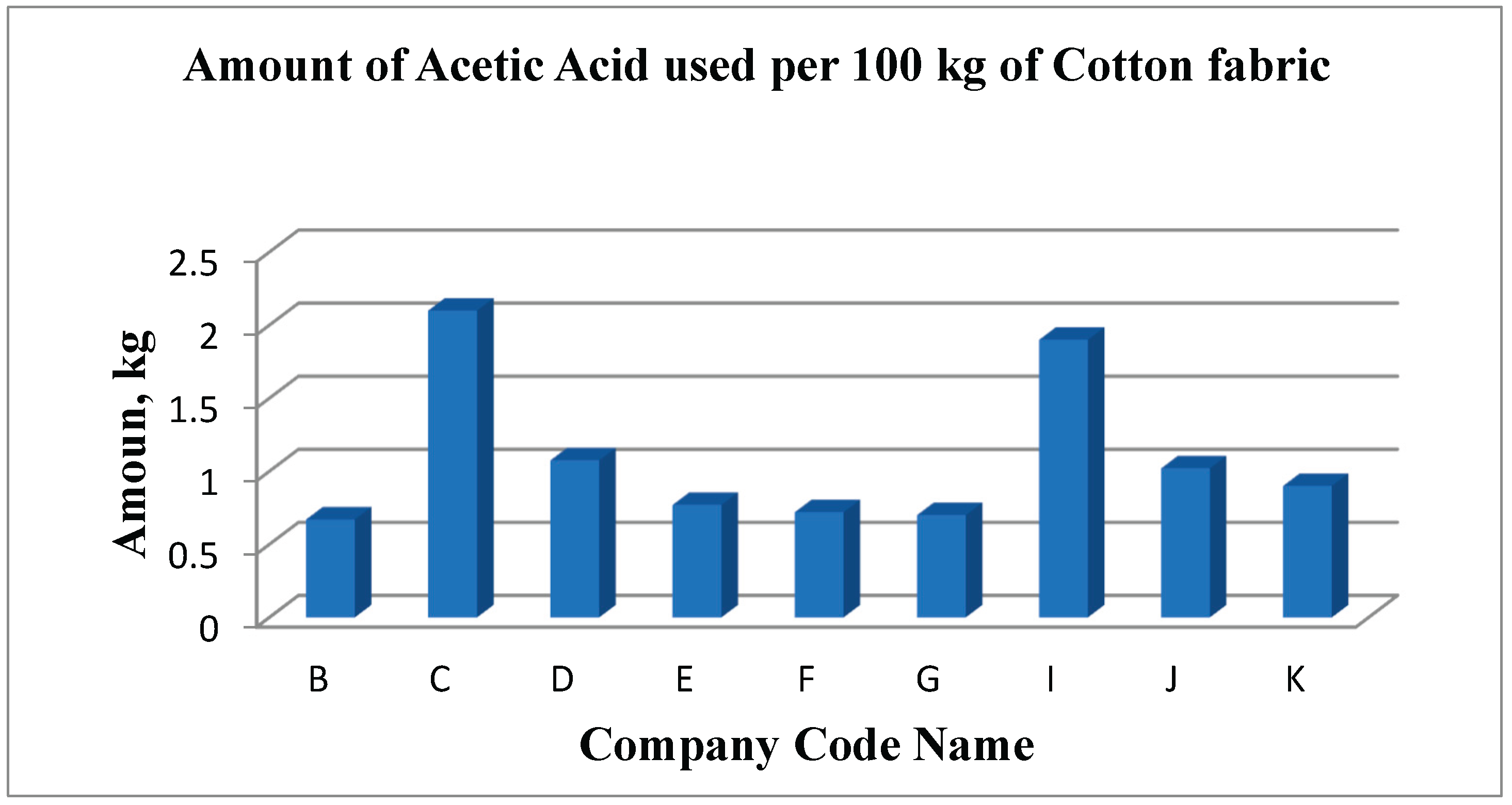

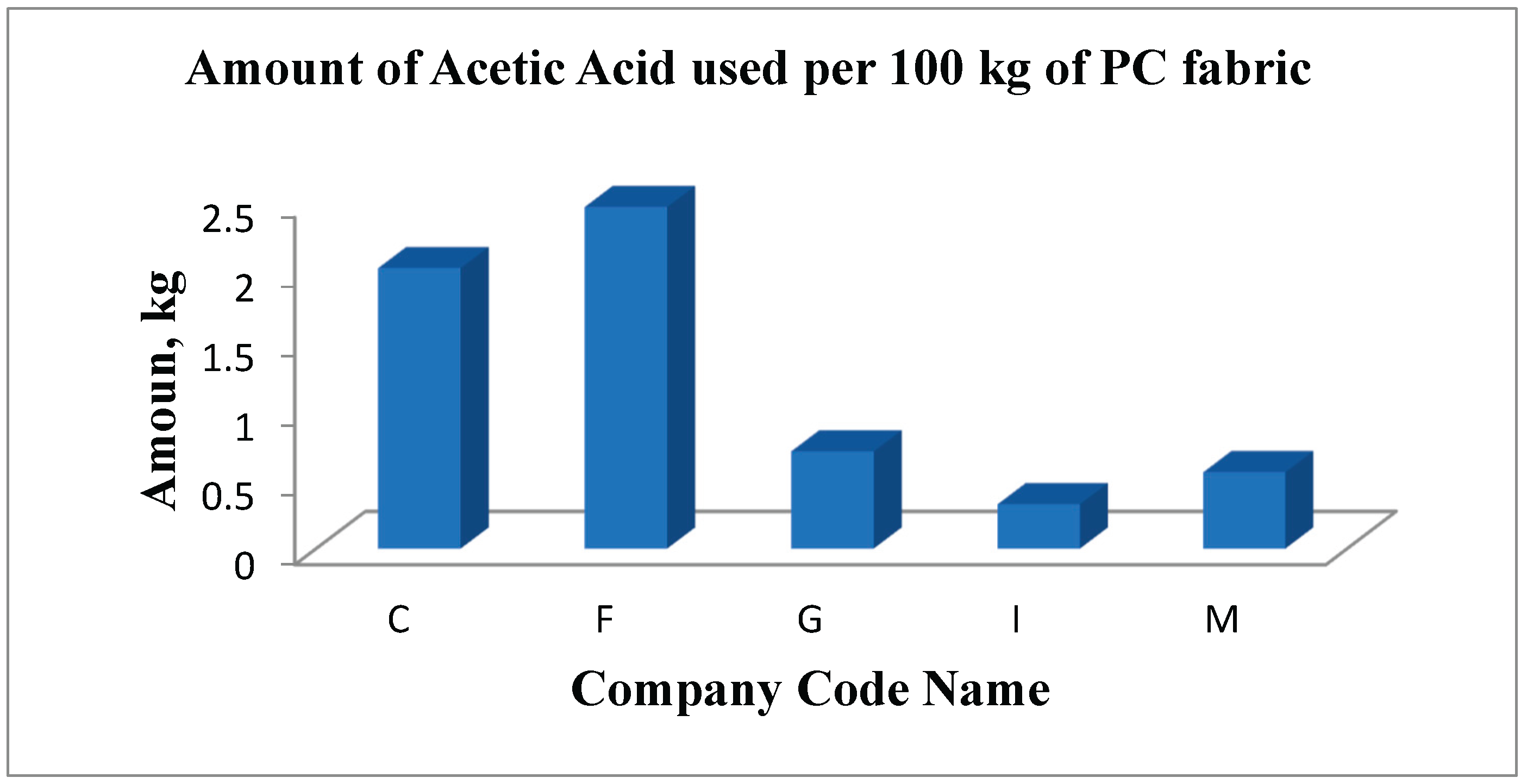

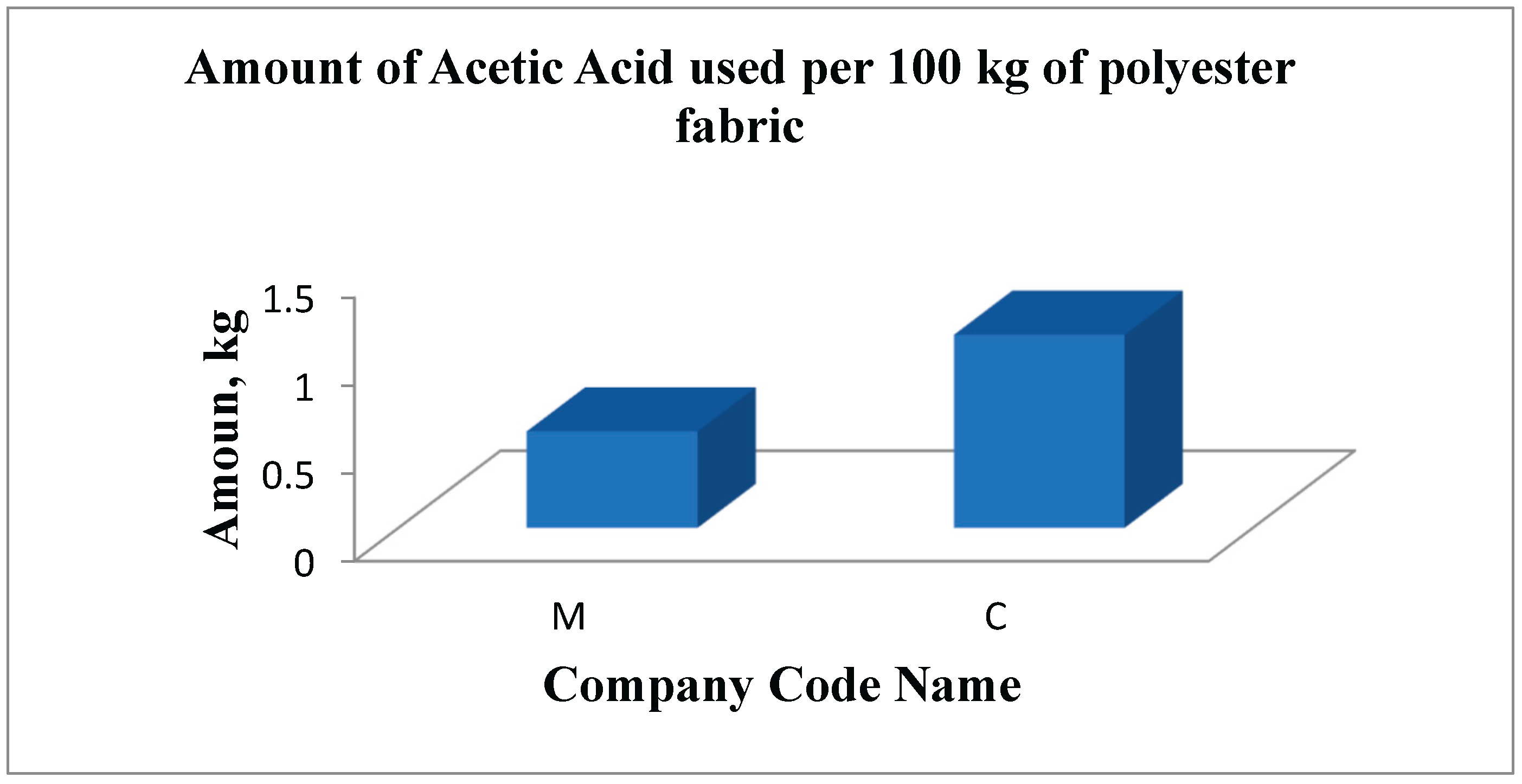

Acetic Acid

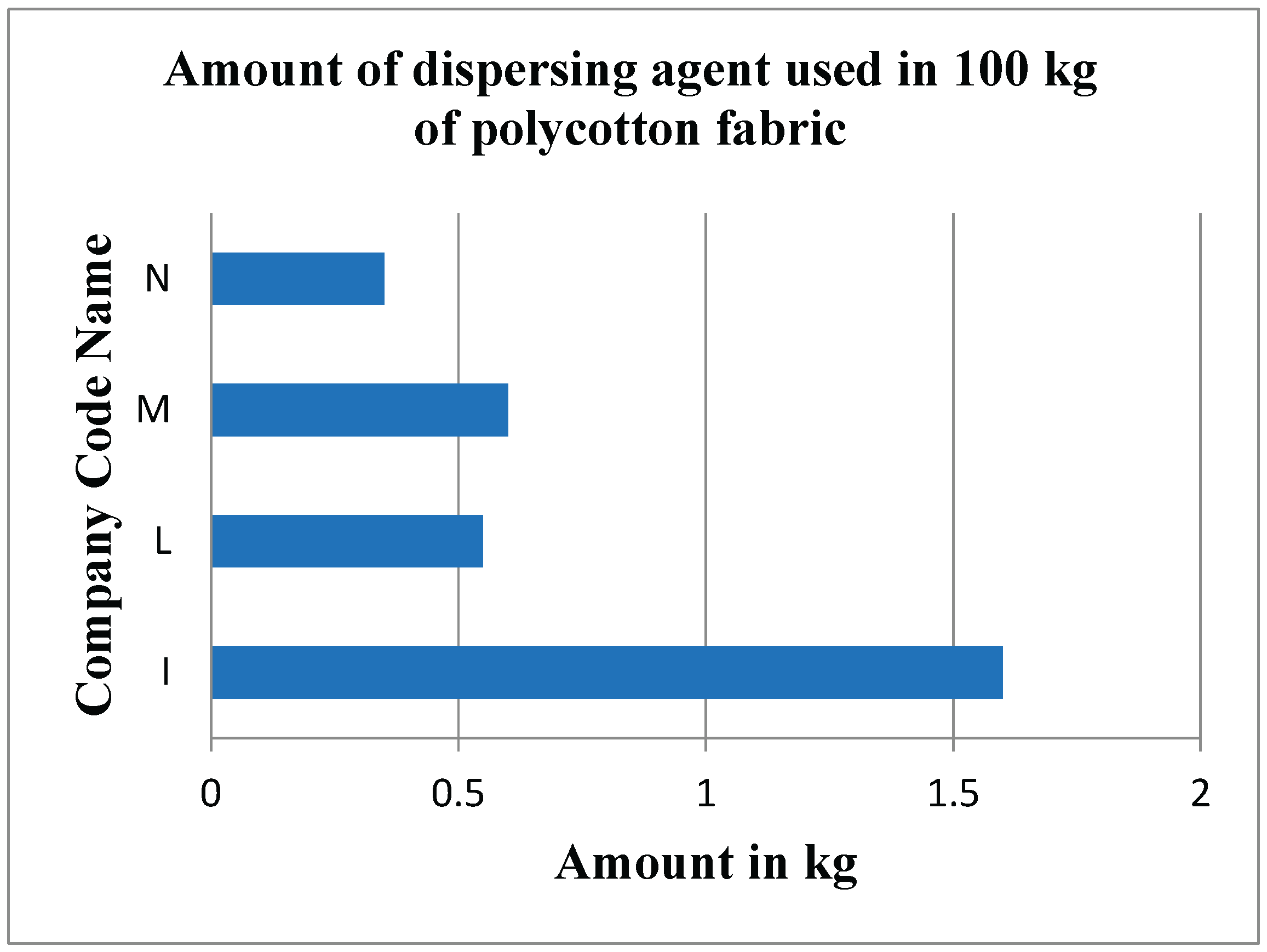

Dispersing Agent

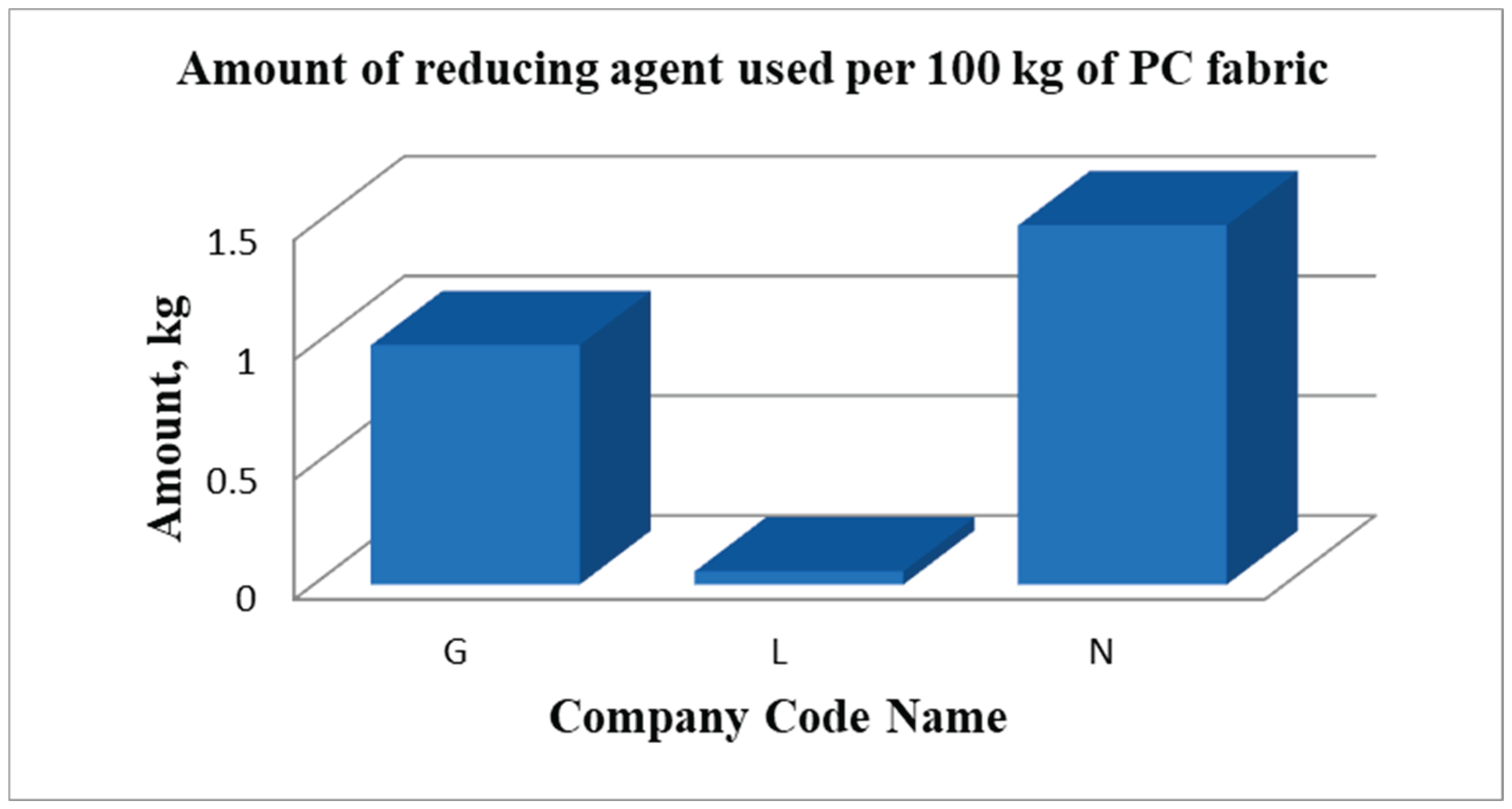

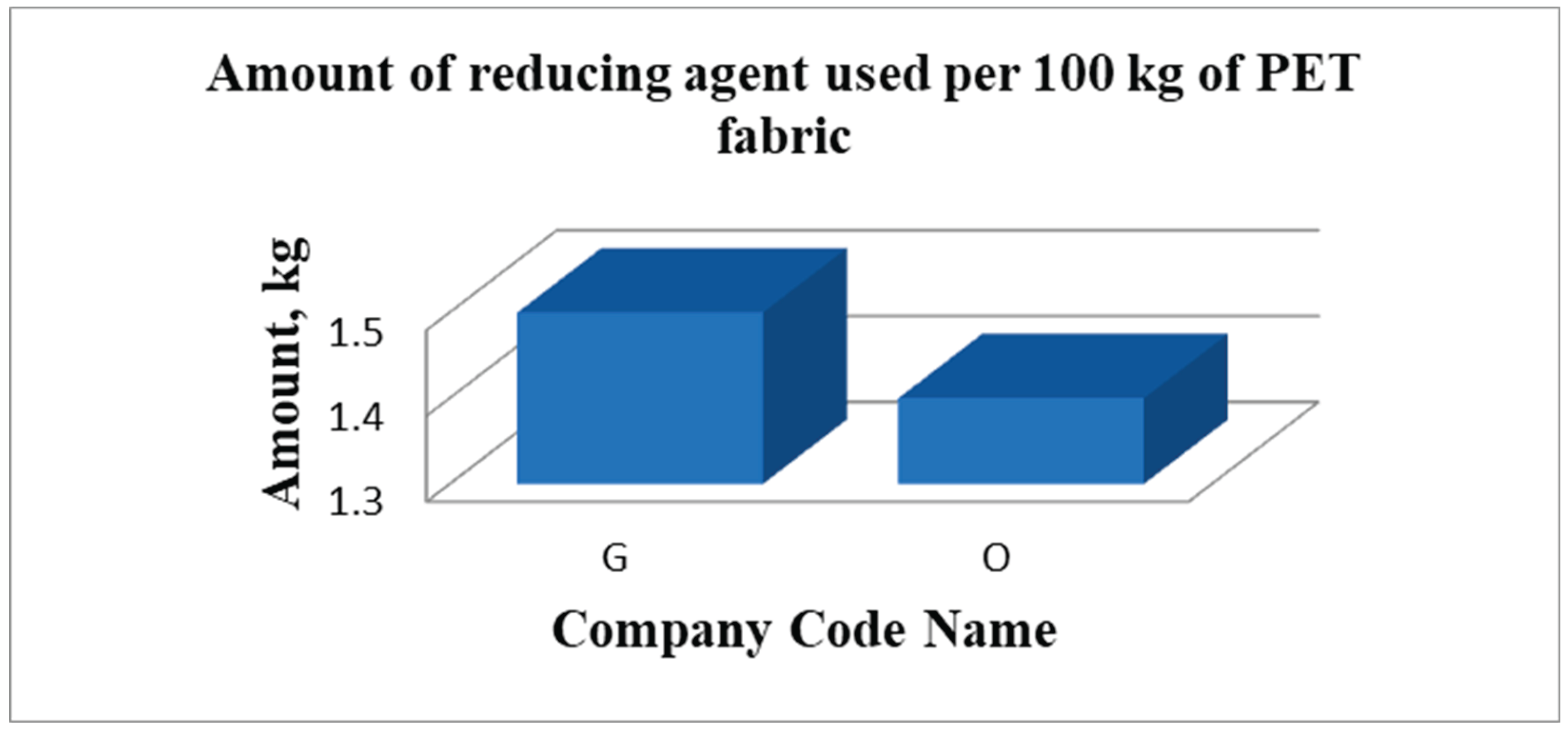

Reducing Agent

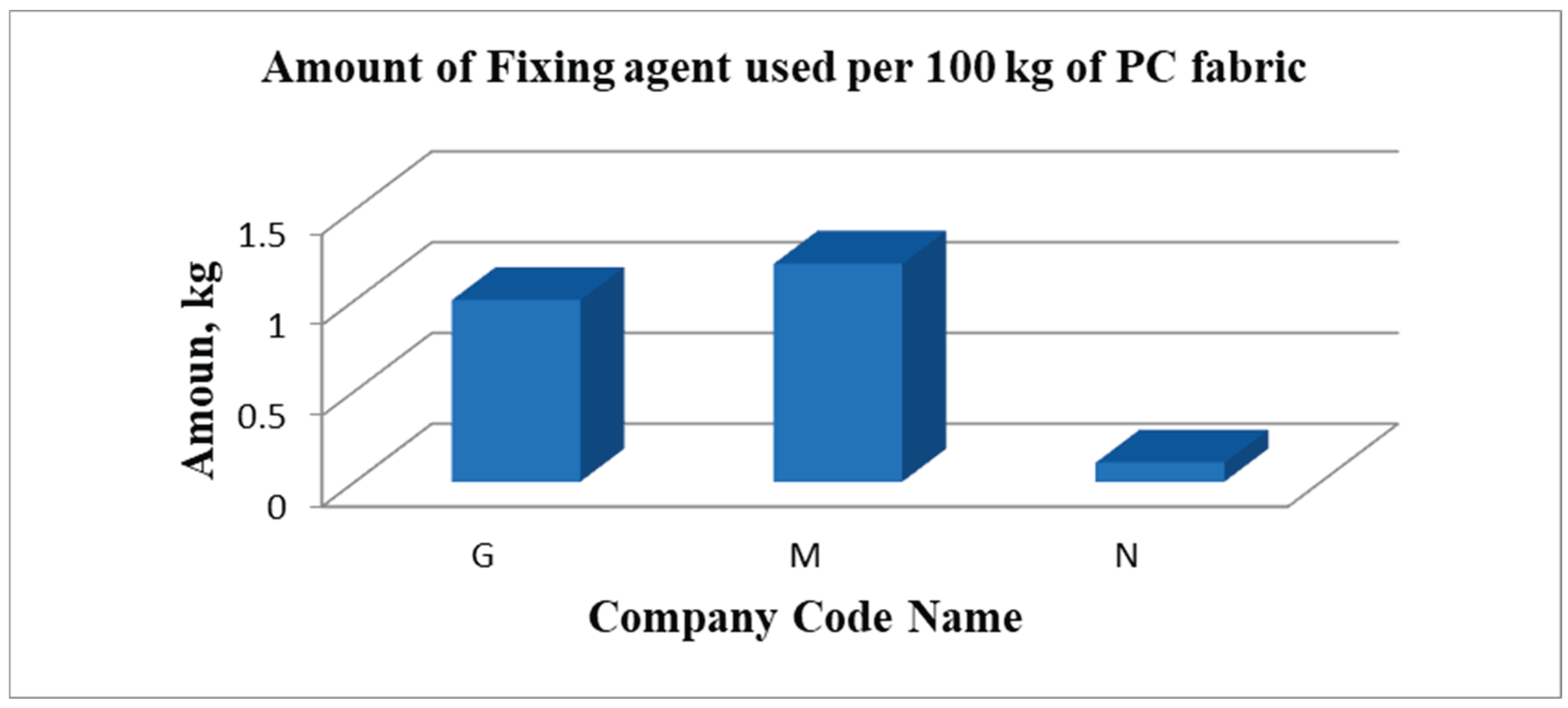

Fixing Agent

Others

Discussion

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Islam, Md.T. , Haque, F., Mahmud, K., Sultana, A., 2022. Sustainable Textile Industry: An Overview. Non-Metallic Materials Science. 4(2), 15–32. [CrossRef]

- Haque, F. , Khandaker, Md.M.R., Chakraborty, R., Khan, M.S., 2020. Identifying Practices and Prospects of Chemical Safety and Security in the Bangladesh Textiles Sector. Journal of Chemical Education. 97(7), 1747–1755. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.M. , Garcia, V.S.G., Boiani, N.F., Melo, C.G., Pereira, M.C.C., Borrely, S.I., 2019. Toxicity and environmental impacts approached in the dyeing of polyamide, polyester and cotton knits. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 7(2), 102973. [CrossRef]

- Roy Choudhury, A.K. , 2013. Green chemistry and the textile industry. Textile Progress. 45(1), 3–143. [CrossRef]

- Manickam, P. , Vijay, D., 2021. Chemical hazards in textiles. In: Chemical Management in Textiles and Fashion. Elsevier, pp. 19–52. [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research, 2025. Textile Market Size, Share & Growth Analysis Report, 2030. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/textile-market (accessed ). 2 April.

- Aizenshtein, E.M. , 2017. Polyester Fibres: Today and Tomorrow. Fibre Chemistry. 49(4), 288–293. [CrossRef]

- Textile Today, 2018. Knit sector gains a great momentum in 2018. https://textiletoday.com.bd/knit-sector-gains-a-great-momentum-in-2018 (accessed ). 2 April.

- Singha, K. , Pandit, P., Maity, S., Sharma, S.R., 2021. Chapter 11 - Harmful environmental effects for textile chemical dyeing practice. In: Ibrahim, N., Hussain, C.M. (Eds.), Green Chemistry for Sustainable Textiles. Woodhead Publishing, pp. 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, F. , 2021. Environmental hazard in textile dyeing wastewater from local textile industry. Cellulose. 28(17), 10715–10739. [CrossRef]

- Valko, E.I. , 1972. Textile Auxiliaries in Dyeing. Review of Progress in Coloration and Related Topics. 3(1), 50–62. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. , Zhang, L., Kim, H., Wu, X., Qiu, Y., Liu, Y., 2024. Research Progress and Development Trend of Textile Auxiliaries. Fibers and Polymers. 25(5), 1569–1601. [CrossRef]

- Ortikmirzaevich, T.B. , 2017. Improving logistics as main factor in textile capacity usage. Zbornik Radova Departmana za Geografiju, Turizam i Hotelijerstvo. 46(2), 44–52.

- Chowdhury, M.A. , Pandit, P., 2022. Chemical processing of knitted fabrics. In: Advanced Knitting Technology. Elsevier, pp. 503–536. [CrossRef]

- IntechOpen, 2025. Textile Dyeing Wastewater Treatment. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/22395 (accessed ). 2 April.

- Straits Research, 2025. Textile Dyes Market Size, Share | Growth Report 2033. https://straitsresearch.com/report/textile-dyes-market (accessed ). 2 April.

- The Financial Express, 2025. Women account for 55pc of garment workers. https://today.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade-market/women-account-for-55pc-of-garment-workers-1719244417 (accessed ). 3 April.

- WFX Fashion & Apparel Blog, 2025. 10 Stats on Bangladesh’s Growing Textile and Garment Industry. https://www.worldfashionexchange.com/blog/rise-of-bangladesh-textile-and-garment-industry/ (accessed ). 3 April.

- Fact.MR, 2025. Knitted Fabrics Market Trends, Demand & Growth Report 2023. https://www.factmr.com/report/2865/knitted-fabrics-market (accessed ). 2 April.

| Company Code Name | Company Type | Location | Types of fabric dyed | ||

| Cotton | Polycotton | Polyester | |||

| A | Knit Composite | Hemayetpur | ✔ | ||

| B | Knit Composite | Zirabo | ✔ | ||

| C | Knit Composite | Mawna | ✔ | ||

| D | Knit Composite | Narayanganj | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| E | Knit Composite | Savar | ✔ | ||

| F | Knit Composite | Fatullah | ✔ | ✔ | |

| G | Knit Composite | Tongi | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| H | Knit Composite | Mirzapur | ✔ | ||

| I | Knit Composite | Durgapur | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| J | Knit Composite | Zirani Bazar | ✔ | ||

| K | Knit Composite | Bhabanipur | ✔ | ✔ | |

| L | Knit Composite | Savar | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| M | Knit Composite | Tongi | ✔ | ||

| N | Knit Composite | Gazipur | ✔ | ||

| O | Knit Composite | Kanchpur | ✔ | ||

|

| Company Code Name | Fiber Type | Fabric Type | Chemical Name | Process | Amount in kg | |

| 1 | I | polycotton | knit fabric | Wetting Agent | Pre-Treatment | 0.36 |

| Company Code Name | Fiber Type | Fabric Type | Auxiliary Name | Process | Amount in Kg | |

| 1 | G | PET | knit fabric | Softener | After Treatment | 6 |

| Company Code Name | Types of Fiber Used | Types of Fabric | Chemicals Name | Operation | Amount In Kg | |

| 1 | M | polyester | Knit Fabric | Fixing Agent | After Treatment | 1.2 |

| Company Code Name |

Types of Fiber Used | Types of Fabric | Chemicals Name | Operation | Amount in Kg | |

| 1 | M | PC | Knit | Emulsifier | After Treatment | 0.5 |

| 2 | L | PC | Knit | Stabilizer | After Treatment | 0.165 |

| 3 | L | PC | Knit | Peroxide Killer | After Treatment | 0.15 |

| 4 | N | PC | Knit | Citric Acid | All Over | 3.29 |

| 5 | N | PC | Knit | Reduction Inhibitor | Pretreatment | 0.7 |

| 6 | N | PC | Knit | Surfactant And Solvent | Pretreatment | 1.7 |

| 7 | N | PC | Knit | Biopolish | Pre-Treatment | 0.15 |

| 8 | N | PC | Knit | Antifoaming | Pre-Treatment | 0.7 |

| Company Code Name | Types of Fiber Used | Types of Fabric | Chemicals Name | Operation | Amount In Kg | |

| 1 | O | PET | Knit | Solvent | Pre-Treatment | 0.315 |

| 2 | O | PET | Knit | Hydrose | Pre-Treatment | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).