Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

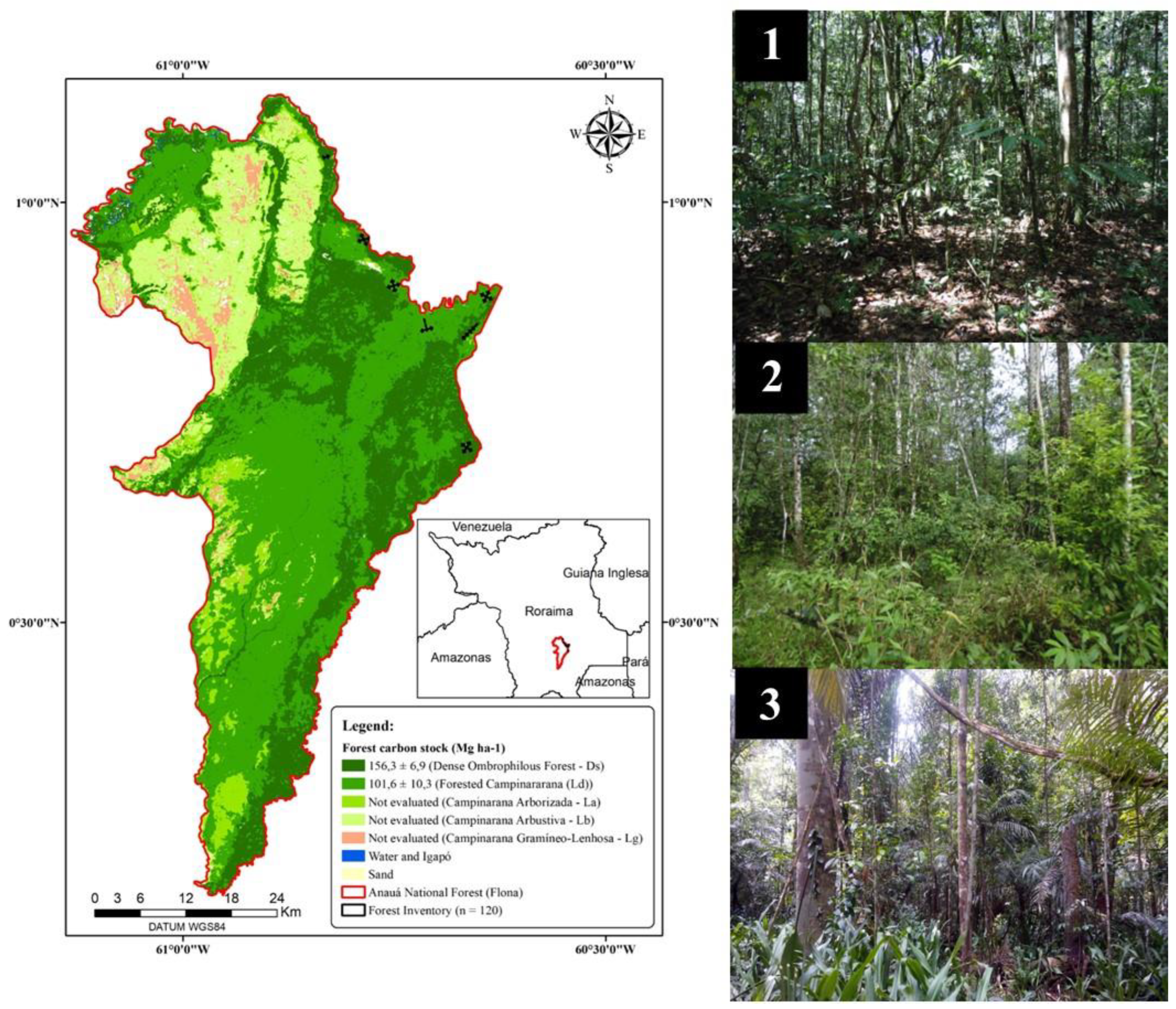

2.1. Study Area and Data Collection

2.2. Botanical Identification and Taxonomy

2.3. Phytosociological and Data Analyses

2.4. Estimates of Total Height, Commercial Volume, Biomass, and Forest Carbon

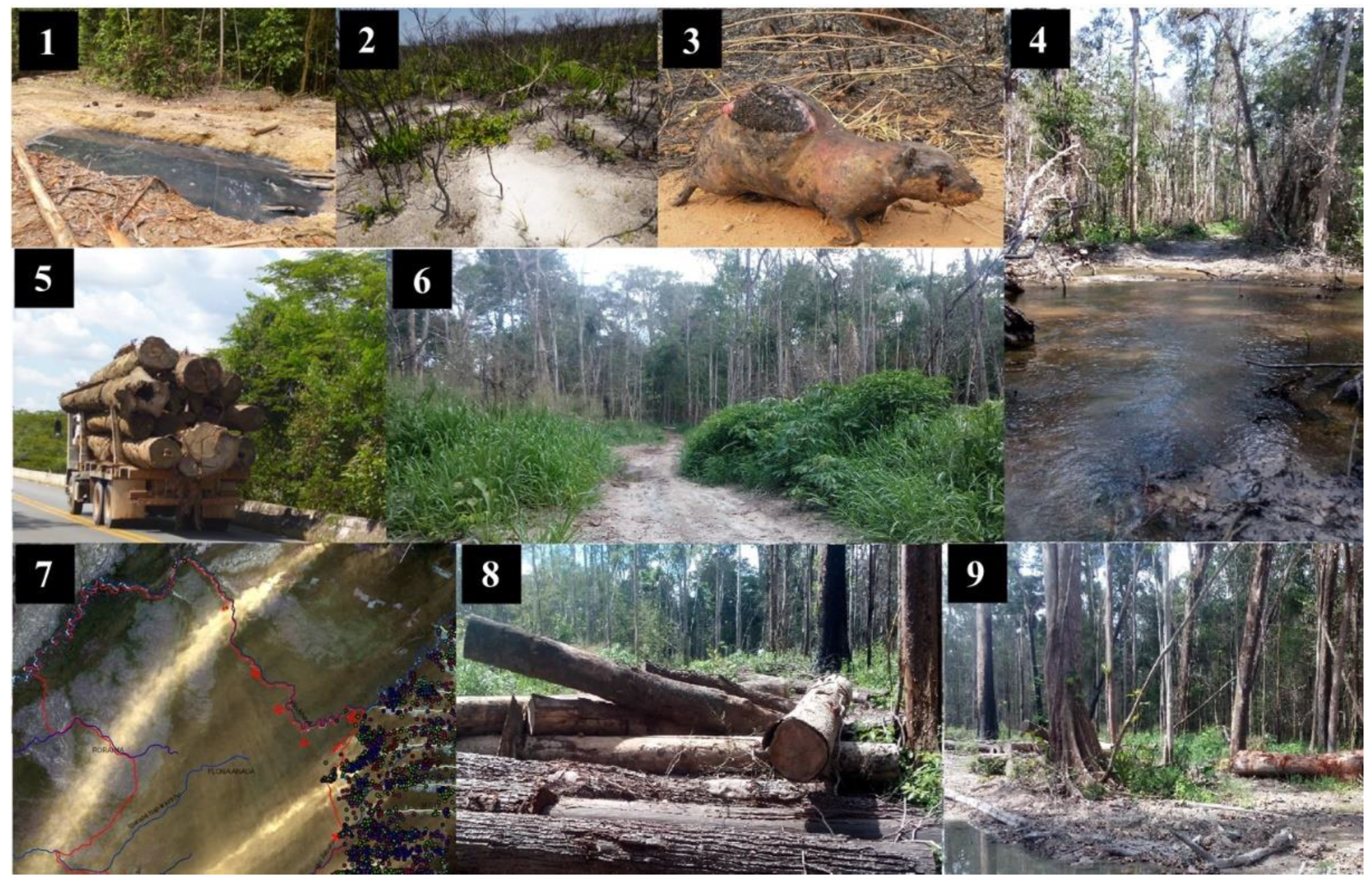

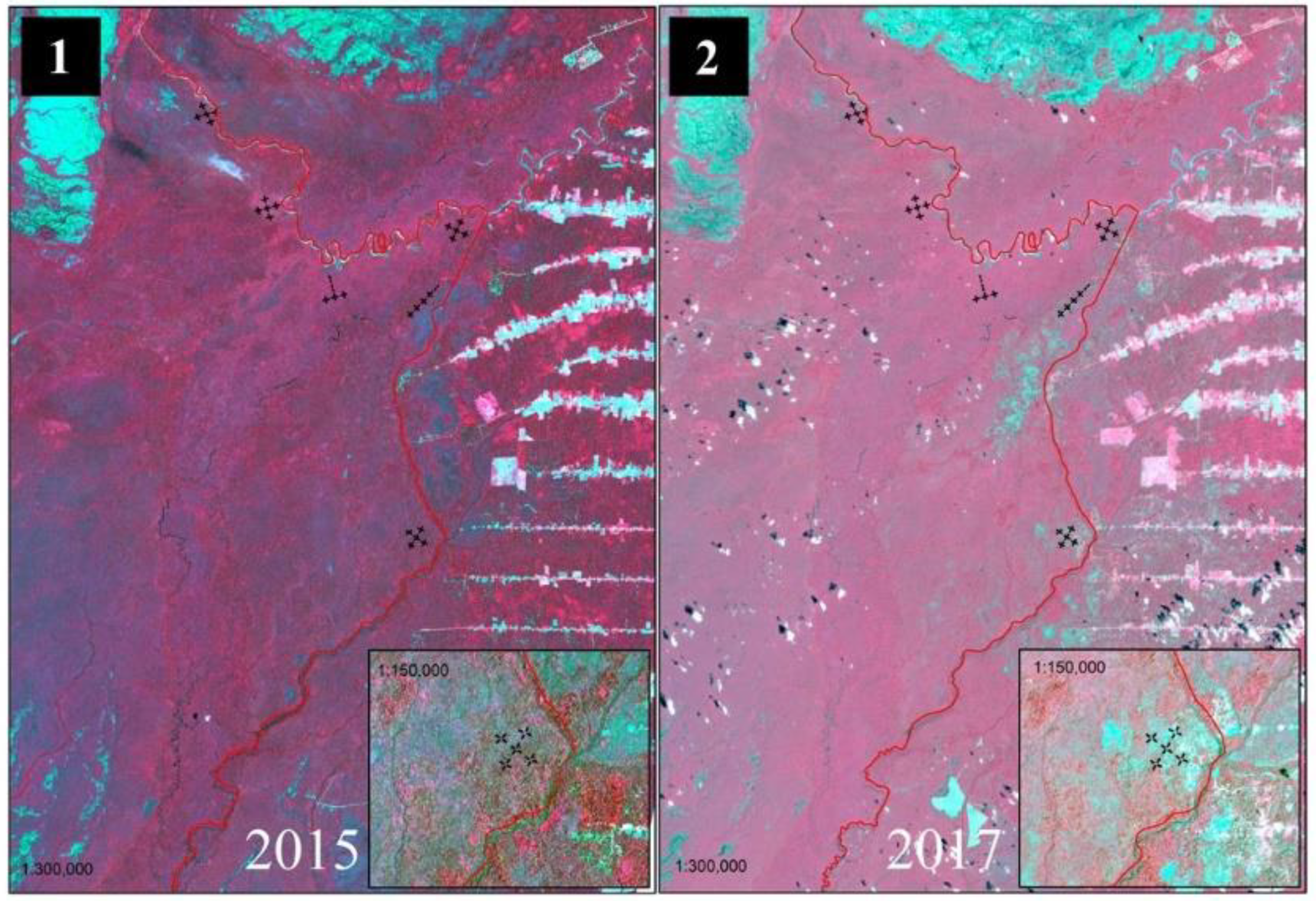

2.5. Estimation of Tree Mortality from Natural and Anthropogenic Causes

3. Results

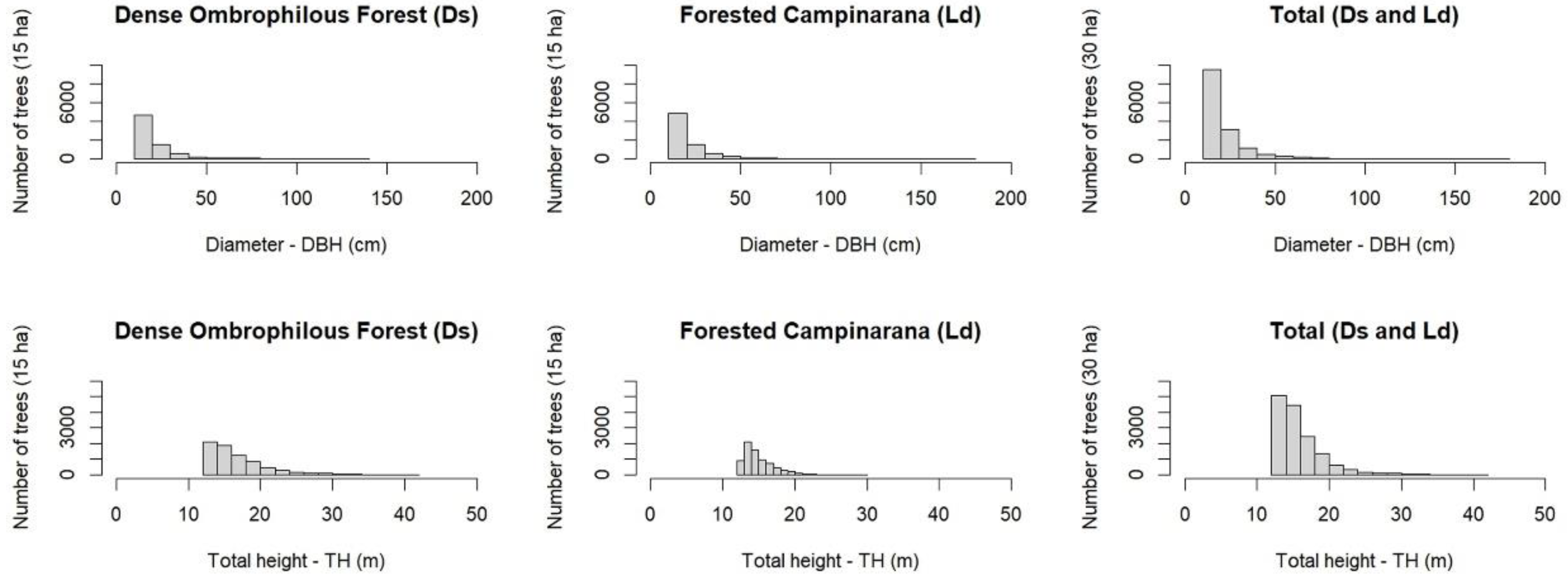

3.1. Forest Inventory, Taxonomy and Forest Structure

3.2. Timber and Non-Timber Potential in a Future Scenario of MFS Through Forest Concessions

3.3. Impact of Anthropogenic Actions on Tree Species Diversity and Remaining Forest Structure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Condé, T.M.; Tonini, H. Fitossociologia de uma Floresta Ombrófila Densa na Amazônia Setentrional, Roraima, Brasil. Acta Amaz. 2013, 43, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.L.; Soares, C.P.B. Florestas Nativas: estrutura, dinâmica e manejo, Editora UFV: Viçosa, Brazil, 2013, ISBN 978-85-7269-463-6.

- Magurran, A.E. Ecological Diversity and Its Measurement, 1rd ed.; Chapman & Hall: University College of North Wales, Bangor, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condé, T.M.; Tonini, H.; Higuchi, N.; Higuchi, F.G.; Lima, A.J.N.; Barbosa, R.I.; Pereira, T.S.; Haas, M.A. Effects of sustainable forest management on tree diversity, timber volumes, and carbon stocks in an ecotone forest in the northern Brazilian Amazon. Land Use Policy, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL, 2006. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2004–2006/2006/Lei/L11284. htm (accessed on 01 February 2025).

- Vidal, E.; Viana, V.M.; Batista, J.L.F. Crescimento de floresta tropical três anos após colheita de madeira com e sem manejo florestal na Amazônia Oriental. Sci. For. 2002, 61, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Condé, T.M.; Higuchi, N.; Lima, A.J.N. Illegal selective logging and forest fires in the Northern Brazilian Amazon. Forests 2019, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francez, L.M.B.; Carvalho, J.O.P.; Jardim, F.C.S. Mudanças ocorridas na composição florística em decorrência da exploração florestal em uma área de floresta de Terra Firme na região de Paragominas, PA. Acta Amaz. 2007, 37(2), 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Muelbert, A.; Phillips, O.L.; Brienenand, R.J.W.; Fauset, S.; Sullivan, M.J.P.; Baker, T.R.; Chao, K.J.; Feldpausch, T.R.; Gloor, E.; Higuchi, N.; and, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Tree mode of death and mortality risk factors across Amazon forests. Nature Com. 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Knapp, D.E.; Broadbent, E.N.; Oliveira, P.J.C.; Keller, M.; Silva, J.N.M. Selective Logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Science 2005, 310, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepstad, D.; McGrath, D.; Stickler, C.; Alencar, A.; Azevedo, A.; Swette, B.; Bezerra, T.; DiGiano, M.; Shimada, J.; Motta, R.S.; and, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Slowing Amazon deforestation through public policy and interventions in beef and soy supply chains. Science 2014, 344, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajão, R.; Soares-Filho, B.; Nunes, F.; Börner, J.; Machado, L.; Assis, D.; Oliveira, A.; Pinto, L.; Ribeiro, V.; Rausch, L.; and, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. The rotten apples of Brazil’s agribusiness. Science 2020, 369, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.C.; Rylands, A.B.; Fonseca, G.A.B. The fate of the Amazonian areas of endemism. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19(3), 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, T.M.; Prado, P.I. How many species are there in Brazil? Cons. Biol. 2005, 19(3), 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Steege, H.; Vaessen, R.W.I; Cárdenas-López, D.; Sabatier, D.; Antonelli, A.; Oliveira, S.M.; Pitman, N.; Jørgensen, P.M.; Salomão, R.P.; Gomes, V.H.F.; and, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. The discovery of the Amazonian tree flora with an updated checklist of all known tree taxa. Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. [CrossRef]

- ter Steege, H.; Pitman, N.C.A.; Amaral, I.L.; Coelho, L.S.; Matos, F.D.A.; Lima Filho, D.A.; Salomão, R.P.; Wittmann, F.; Castilho, C.V.; Guevara, J.E.; and, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. Mapping density, diversity and species-richness of the Amazon tree flora. Comm. Biol. 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaise, E.; Nelson, B.W.; Schietti, J.; Desmoulière, S.J.-M.; Espírito Santo, H.M.V.; Costa, F.R.C. Assessing the relationship between forest types and canopy tree beta diversity in Amazonia. Ecography 2010, 33(110), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, M.J.G. Modelling the known and unknown plant biodiversity of the Amazon basin. J. of Biogeog. 2007, 34(8), 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condé, T.M.; Higuchi, N.; Lima, A.J.N.; Campos, M.A.A.; Condé, J.D.; Oliveira, A.C.; Miranda, D.L.C. Spectral Patterns of Pixels and Objects of the Forest Phytophysiognomies in the Anauá National Forest, Roraima State, Brazil. Ecologies 2023, 4, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMBio. Chico Mendes Institute of Biodiversity. PAN Portaria nº 457. Plano de Manejo da Floresta Nacional de Anauá. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.br/icmbio/pt-br/assuntos/biodiversidade/unidade-de-conservacao/unidades-de-biomas/amazonia/lista-de-ucs/flona-de-anaua/arquivos/pm_flona_anaua_consolidado_vs-10.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Barbosa, R.I.; Lima, C.G.B. Notas sobre a Diversidade de Plantas e fitofisionomias em Roraima através do Banco de Dados do Herbário Inpa. Amazônia: Ci. & Desenv. 2008, 4(7), 131-154.

- Alemán, L.A.B; Barbosa, R.I.; Fernández, I.M.; Carvalho, L.C.S; Barni, P.E.; Oliveira, R.L.C.; Vale Jr., J. F.; Maldonado, S.A.S.; Pérez, N.E.A. Edaphic Factors and Flooding Periodicity Determining Forest Types in a Topographic Gradient in the Northern Brazilian Amazonia. Int. J. of Plant & Soil Science. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.B. White-sand vegetation of Brazilian Amazonia. Biotropica 1981, 13(3), 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Araújo, A.C.; Artaxo, P.; Balch, J.K.; Brown, I.F.; Bustamante, M.M.C.; Coe, M.T.; DeFries, R.S.; Keller, M.; Longo, M.; and, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. The Amazon basin in transition. Nature 2012, 411, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Manual Técnico da Vegetação Brasileira. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=263011 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- INCT. Herbário Virtual da Flora e dos Fungos. Available online: http://inct.florabrasil.net/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- TROPICOS. Missouri Botanical Garden. Available online: https://tropicos.org (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- REFLORA. Available online: http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/ (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- FLORA BRASILIENSIS. Centro de Referência em Informação Ambiental. Available online: https://florabrasiliensis.cria.org.br/opus (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- APG III. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. of the Linnean Soc. [CrossRef]

- APG, IV. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. of the Linnean Soc. [CrossRef]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 5nd ed. Prentice Hall: New Jersey, EUA, 2010, ISBN 978-0-13-100846-5.

- ter Steege, H.; Pitman, N.C.A.; Sabatier, D.; Baraloto, C.; Salomão, R.P.; Guevara, J.E.; Oliver, L. Phillips, Castilho, C.V.; Magnusson, W.E.; Molinoet, J.F; and et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian Tree Flora. Science 2013, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Müller-Dombois, D.; Ellemberg, H. Aims and methods for vegetation ecology, John Wiley & Sons: New York, EUA, 1974, ISBN 9781930665736.

- SISBIO. Autorização de Pesquisa nas Unidades de Conservação Federal (UC´s). Available online: https://www.gov.br/icmbio/pt-br/servicos/servicos-do-icmbio-no-gov.br/autorizacoes/pesquisa-nas-ucs-sisbio (accessed on 1 July 2017).

- Silva, R.P. Alometria, estoque e dinâmica da biomassa de florestas primárias e secundárias na região de Manaus (AM). Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia/Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Woortmann, C.P.I.B. Equações Alométricas, Estoque de Biomassa e Teores de Carbono e Nitrogênio de Campinaranas da Amazônia Central. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, AM, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.J.N.; Suwa, R.; Ribeiro, G.H.P.M.; Kajimoto, T.; Santos, J.; Silva, R.P.; Souza, C.; Barros, A.S.; Noguchi, P.C., H. , Ishizuka, M., Higuchi, N. Allometric models for estimating above- and below-ground biomass in Amazonian forests at São Gabriel da Cachoeira in the upper Rio Negro, Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 277, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.Q.; Artaxo, P. Biosphere-atmosphere interactions: Deforestation size influences rainfall. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artaxo, P.; Gatti, L.V.; Leal, A.M.C.; Longo, K.M.; Freitas, S.R.; Lara, L.L.; Pauliquevis, T.M.; Procópio, A.S.; Rizzo, L.V. Química atmosférica na Amazônia: A floresta e as emissões de queimadas controlando a composição da atmosfera amazônica. Acta Amazonica 2005, 35(2), 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnside, P.M.; Barbosa, R.I.; Pereira, V.B. Emissões de gases do efeito estufa por desmatamento e incêndios florestais em Roraima: fontes e sumidouros. Revista Agro@mbiente On-line. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Presidência da República. Lei nº 12.651, de 25 de maio de 2012. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011–2014/2012/Lei/L12651.htm (accessed on 07 February 2015).

- CONAMA. Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente. Resolução nº 406, de 02 de fevereiro de 2009. Available online: https://conama.mma.gov.br/?option=com_sisconama&task=arquivo.download&id=578 (accessed on 07 February 2025).

- BRASIL. Presidência da República. Lei nº 9.985, de 18 de julho de 2000. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L9985.htm (accessed on 07 February 2015).

- Fearnside, P.M. A floresta Amazônica nas mudanças globais, INPA: Manaus, Brasil, 2003.

- Barreto, P.; Souza Jr., C.; Noguerón, R.; Anderson, A.; Salomão, R. Pressão humana na floresta amazônica brasileira. Imazon: Belém, Brasil, 2005.

- ICMBio. Chico Mendes Institute of Biodiversity. Portaria nº 457. Plano de Manejo da Floresta Nacional de Anauá. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.br/icmbio/pt-br/assuntos/biodiversidade/unidade-de-conservacao/unidades-de-biomas/amazonia/lista-de-ucs/flona-de-anaua/arquivos/pm_flona_anaua_consolidado_vs-10.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Adeney, J.M.; Christensen, N.L.; Vicentini, A.; Cohn-Haft, M. White-sand Ecosystems in Amazonia. Biotropica 2016, 48, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivelli, B.R.S.; Gomes, J.P.; Morais, W.W.C.; Condé, T.M.; Santos, R.L.; Bonfim Filho, O.S. Caracterização do setor madeireiro de Rorainópolis, sul de Roraima. Ciência da Madeira. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Presidência da República. Lei nº 14.119, de 13 de janeiro de 2021. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2019-2022/2021/Lei/L14119.htm (accessed on 07 February 2023).

- Putz, F.E.; Sist, P.; Fredericksen, T.; Dykstra, D. Reduced-impact logging: challenges and opportunities. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 256, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Zweede, J.; Asner, G.P.; Keller, M. Forest canopy damage and recovery in reduced-impact and conventional selective logging in eastern Para, Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 168, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, E.O.; Braz, E.M.; Oiveira, M.V.N. Manejo de Precisão em Florestas Tropicais: Modelo Digital de Exploração Florestal. Embrapa Acre/Embrapa Florestas: Rio Branco, Brasil, 2007.

- Amaral, P.; Veríssimo, A.; Barreto, P.; Vidal, E. Floresta para Sempre: um Manual para Produção de Madeira na Amazônia, 1ed., Imazon: Belém, Brazil, 1998.

- Braz, E.M. Subsídios para o planejamento do manejo de florestas tropicais da Amazônia. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Curitiba, Paraná, 2010.

- FSC. Forest Stewardship Council. Forest Management Certification. FSC Document reference code: FSC-STD-01–001 V5–2 EN. Bonn, Germany, 2015.

- REDD. Redução de Emissões por Desmatamento e Degradação Florestal. REDD no Brasil: um enfoque amazônico - Fundamentos, critérios e estruturas institucionais para um regime nacional de Redução de Emissões por Desmatamento e Degradação Florestal - Edição revista e atualizada. Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos/Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia/Secretaria de Assuntos Estratégicos da Presidência da República, 2011.

- Fearnside, P.M. Quantificação do serviço ambiental do carbono nas florestas amazônicas brasileiras. Oecologia Brasiliensis 2008, 12(4), 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, N. O papel da floresta amazônica como mitigadora dos efeitos da mudança climática global pretérita. Available online: https://florestal.revistaopinioes.com.br/pt-br/revista/detalhes/7-floresta-amazonica-r-mudancas-climaticas/ (accessed on 27 September 2023).

- Lapola, D.M.; Pinho, P.; Barlow, J.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Berenguer, E.; Carmenta, R.; Liddy, H.M.; Seixas, H.; Silva, C.V.J.; Silva-Junior, C.H.L.; and, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. The drivers and impacts of Amazon forest degradation. Science 2023, 379, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, B.O.; Danielli, F.E.; Oliveira, C.K.A.; Santos, J.; Higuchi, N. Equações volumétricas para espécies comerciais madeireiras do sul do estado de Roraima. Scientia Forestalis 2015, 43(106), 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Brancalion, P.H.S.; de Almeida, D.R.A.; Vidal, E.; Molin, P.G.V.; Sontag, E.; Souza, S.E.X.F.; Schulze, M.D. Fake legal logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Sci. Adv. 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.I; Souza, A.N.; Joaquim, M.S.; Júnior, I.M.L.; Pereira, R.S. Concessão florestal na Amazônia brasileira. Ci. Fl. 2020, 30(4), 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PF. Polícia Federal. Operação Salmo 96:12 prende servidores federais. Available online: https://www.jusbrasil.com.br/noticias/mpf-rr-e-policia-federal-deflagram-operacao-de-combate-a-grilagem-e-desmatamento-ilegal/3128405?msockid=27ed666b8f7d60991be3704e8ecc61bb (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- PF. Polícia Federal. Operação Xilófagos combate o avanço do desmatamento na Amazônia Legal. Available online: https://www.ecoamazonia.org.br/2014/12/policia-federal-deflagra-operacao-coibir-desmatamento-ilegal-rr/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

| Scientific Name | Treesi | D | DBH | TH | BA | V | Biomass | Carbon | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGB | BGB | B | AGC | BGC | C | |||||||||||

| Anacardiaceae | ||||||||||||||||

| Anacardium giganteum W. Hancock ex Engl. | 16 | 0.53 | 32.0 | ± | 24.3 | 19.0 | ± | 6.7 | 0.066 | 0.612 | 0.8699 | 0.1790 | 0.8914 | 0.4176 | 0.0859 | 0.4279 |

| Anacardium parvifolium Ducke | 1 | 0.03 | 27.5 | - | - | 19.5 | - | - | 0.002 | 0.015 | 0.0277 | 0.0037 | 0.0292 | 0.0133 | 0.0018 | 0.0140 |

| Anacardium sp. | 1 | 0.03 | 40.3 | - | - | 23.2 | - | - | 0.004 | 0.036 | 0.0575 | 0.0094 | 0.0597 | 0.0276 | 0.0045 | 0.0286 |

| Astronium lecointei Ducke | 2 | 0.07 | 16.3 | ± | 5.3 | 15.3 | ± | 2.3 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.0212 | 0.0022 | 0.0227 | 0.0102 | 0.0010 | 0.0109 |

| Spondias sp. | 57 | 1.90 | 40.2 | ± | 13.2 | 19.7 | ± | 2.9 | 0.266 | 2.333 | 3.5666 | 0.6326 | 3.6839 | 1.7120 | 0.3036 | 1.7683 |

| Tapirira guianensis Aubl. | 18 | 0.60 | 28.1 | ± | 13.4 | 17.1 | ± | 2.8 | 0.045 | 0.379 | 0.6175 | 0.0976 | 0.6434 | 0.2964 | 0.0468 | 0.3088 |

| Anisophylleaceae | ||||||||||||||||

| Anisophyllea guianensis Sandwith | 4 | 0.13 | 15.3 | ± | 3.5 | 14.9 | ± | 1.6 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.0373 | 0.0037 | 0.0401 | 0.0179 | 0.0018 | 0.0192 |

| Anisophyllea manausensis Pires & W.A.Rodrigues | 1 | 0.03 | 18.9 | - | - | 15.0 | - | - | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.0135 | 0.0014 | 0.0144 | 0.0065 | 0.0007 | 0.0069 |

| Annonaceae | ||||||||||||||||

| Anaxagorea brevipes Benth. | 218 | 7.27 | 18.2 | ± | 9.2 | 15.2 | ± | 2.8 | 0.237 | 1.846 | 3.3266 | 0.4430 | 3.5138 | 1.5968 | 0.2126 | 1.6866 |

| Annona ambotay Aubl. | 2 | 0.07 | 13.3 | ± | 2.5 | 14.0 | ± | 1.2 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.0139 | 0.0012 | 0.0150 | 0.0067 | 0.0006 | 0.0072 |

| Annona neoinsignis H. Rainer | 2 | 0.07 | 17.6 | ± | 7.7 | 15.6 | ± | 3.4 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.0254 | 0.0028 | 0.0271 | 0.0122 | 0.0014 | 0.0130 |

| Annona sp. 1 | 19 | 0.63 | 16.3 | ± | 5.8 | 15.1 | ± | 2.4 | 0.015 | 0.107 | 0.2130 | 0.0233 | 0.2274 | 0.1022 | 0.0112 | 0.1092 |

| Annona sp. 2 | 1 | 0.03 | 10.3 | - | - | 12.5 | - | - | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.0043 | 0.0003 | 0.0047 | 0.0020 | 0.0002 | 0.0022 |

| Bocageopsis multiflora (Mart.) R.E.Fr. | 202 | 6.73 | 17.6 | ± | 4.5 | 15.6 | ± | 1.8 | 0.174 | 1.258 | 2.5017 | 0.2723 | 2.6715 | 1.2008 | 0.1307 | 1.2823 |

| Duguetia chrysea Maas | 363 | 12.10 | 15.7 | ± | 4.5 | 14.4 | ± | 1.5 | 0.252 | 1.796 | 3.6661 | 0.3806 | 3.9285 | 1.7598 | 0.1827 | 1.8857 |

| Duguetia trunciflora Maas & A.H.Gentry | 3 | 0.10 | 15.4 | ± | 1.6 | 14.7 | ± | 0.9 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.0276 | 0.0027 | 0.0298 | 0.0133 | 0.0013 | 0.0143 |

| Guatteria scytophylla Diels | 55 | 1.83 | 19.9 | ± | 9.1 | 15.3 | ± | 2.4 | 0.069 | 0.537 | 0.9675 | 0.1277 | 1.0212 | 0.4644 | 0.0613 | 0.4902 |

| Guatteria sp. | 3 | 0.10 | 18.4 | ± | 6.0 | 15.5 | ± | 2.7 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.0408 | 0.0046 | 0.0435 | 0.0196 | 0.0022 | 0.0209 |

| Onychopetalum amazonicum R.E. Fr. | 1 | 0.03 | 17.3 | - | - | 15.8 | - | - | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.0114 | 0.0012 | 0.0122 | 0.0055 | 0.0006 | 0.0059 |

| Xylopia amazonica R.E. Fr. | 105 | 3.50 | 18.7 | ± | 5.2 | 15.9 | ± | 2.0 | 0.103 | 0.759 | 1.4749 | 0.1677 | 1.5705 | 0.7080 | 0.0805 | 0.7538 |

| Xylopia benthamii R.E.Fr. | 8 | 0.27 | 11.3 | ± | 1.2 | 13.0 | ± | 0.6 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.0409 | 0.0033 | 0.0445 | 0.0196 | 0.0016 | 0.0214 |

| Xylopia polyantha R.E.Fr. | 17 | 0.57 | 17.2 | ± | 5.3 | 15.0 | ± | 1.7 | 0.014 | 0.104 | 0.2055 | 0.0225 | 0.2194 | 0.0987 | 0.0108 | 0.1053 |

| Xylopia sp. | 7 | 0.23 | 17.4 | ± | 2.9 | 14.6 | ± | 0.7 | 0.006 | 0.041 | 0.0827 | 0.0086 | 0.0885 | 0.0397 | 0.0041 | 0.0425 |

| Apocynaceae | ||||||||||||||||

| Ambelania duckei Markgr. | 14 | 0.47 | 14.3 | ± | 5.0 | 13.7 | ± | 1.3 | 0.008 | 0.059 | 0.1218 | 0.0124 | 0.1307 | 0.0584 | 0.0059 | 0.0627 |

| Aspidosperma album (Vahl) Benoist ex Pichon | 4 | 0.13 | 14.9 | ± | 3.1 | 14.6 | ± | 1.5 | 0.002 | 0.017 | 0.0351 | 0.0034 | 0.0378 | 0.0168 | 0.0016 | 0.0181 |

| *Other species ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ||

| Undetermined | 123 | 4.10 | 24.3 | ± | 11.7 | 17.4 | ± | 3.6 | 0.234 | 1.911 | 3.2181 | 0.4817 | 3.3680 | 1.5447 | 0.2312 | 1.6166 |

| Dead trees | 1,033 | 34.43 | 21.5 | ± | 13.4 | 16.3 | ± | 3.5 | 1.742 | 14.623 | 23.8278 | 3.8586 | 24.8688 | 11.4373 | 1.8521 | 11.9370 |

| Total (Ds and Ld) | 14,730 | 491 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22.7 | 187.4 | 313.2 | 48.2 | 327.8 | 150.3 | 23.1 | 157.3 |

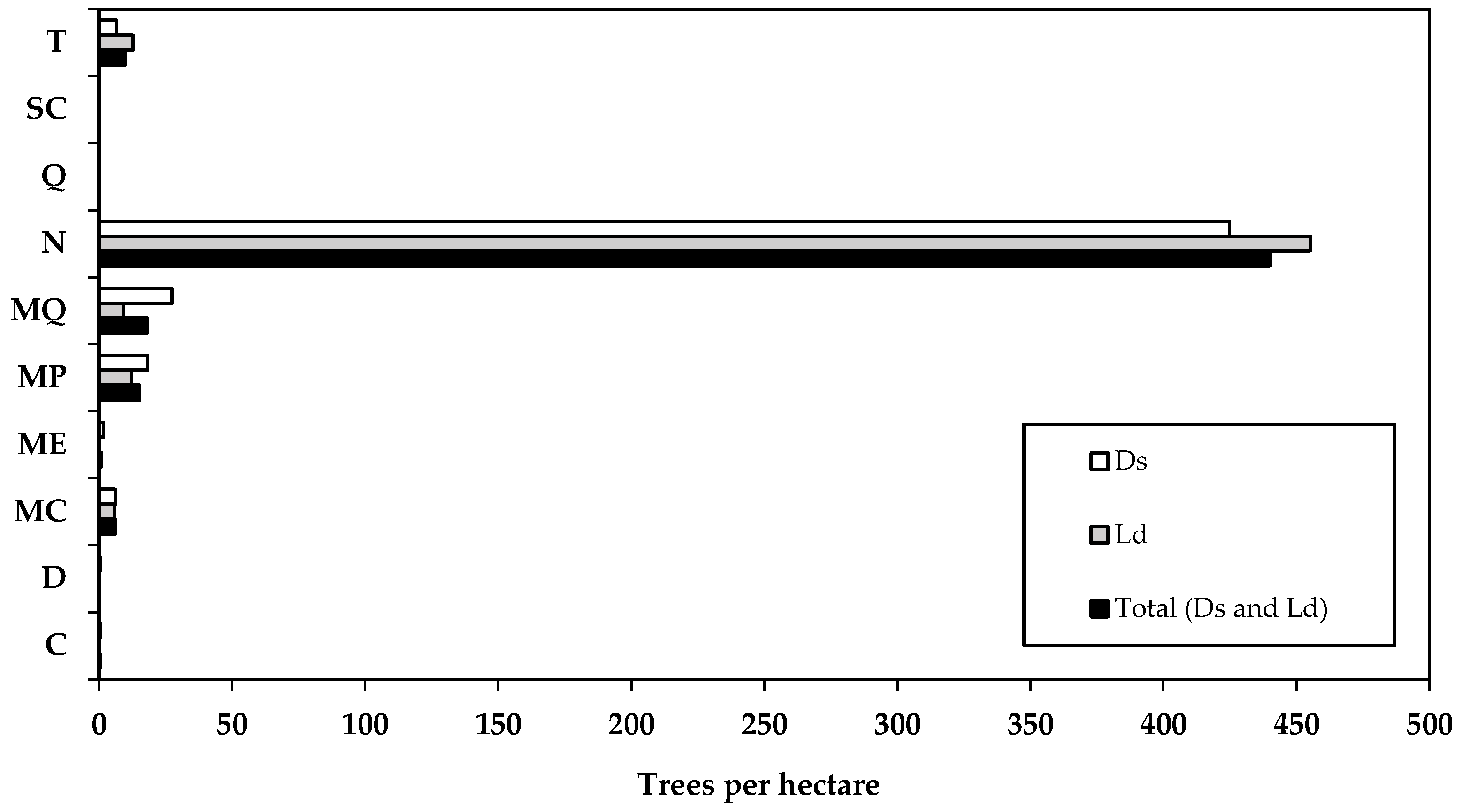

| Ranking | Botanical Family | Horizontal Structure | Carbon | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treesi | BAi | ADi | RDi | ADoi | RDoi | ADIVi | RDIVi | VCi% | FIVi% | AGC | BGC | C | ||

| 1º | Fabaceae | 1,738 | 104.8 | 57.9 | 12.7 | 3.5 | 16.6 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 14.7 | 11.4 | 22.8 | 3.8 | 23.7 |

| 2º | Arecaceae | 2,555 | 57.7 | 85.2 | 18.7 | 1.9 | 9.2 | 0.3 | 5.0 | 13.9 | 10.9 | 13.3 | 1.4 | 14.3 |

| 3º | Sapotaceae | 1,311 | 84.7 | 43.7 | 9.6 | 2.8 | 13.4 | 0.3 | 4.8 | 11.5 | 9.3 | 18.4 | 3.1 | 19.1 |

| 4º | Lecythidaceae | 906 | 38.1 | 30.2 | 6.6 | 1.3 | 6.0 | 0.3 | 4.8 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 8.4 | 1.3 | 8.8 |

| 5º | Annonaceae | 1,006 | 26.4 | 33.5 | 7.3 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 6.4 |

| 6º | Vochysiaceae | 372 | 43.3 | 12.4 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 9.2 | 1.7 | 9.5 |

| 7º | Moraceae | 453 | 29.7 | 15.1 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 6.5 | 1.1 | 6.7 |

| 8º | Chrysobalanaceae | 611 | 22.9 | 20.4 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 0.7 | 5.4 |

| 9º | Burseraceae | 649 | 17.0 | 21.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 4.1 |

| 10º | Lauraceae | 515 | 20.4 | 17.2 | 3.8 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 0.6 | 4.8 |

| Subtotal | 10,116 | 445 | 337 | 74 | 15 | 71 | 3 | 46 | 72 | 64 | 98.2 | 14.9 | 102.9 | |

| Other species* | 4,614 | 237 | 119 | 26 | 6 | 29 | 3 | 54 | 28 | 36 | 52.1 | 8.2 | 54.4 | |

| Total (Ds and Ld)* | 14,730 | 683 | 457 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 150.3 | 23.1 | 157.3 | |

| Ranking | Species | Horizontal Structure | Carbon | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treesi | BAi | ADi | RDi | ADoi | RDoi | AFi | RFi | CVi% | IVi% | AGC | BGC | C | ||

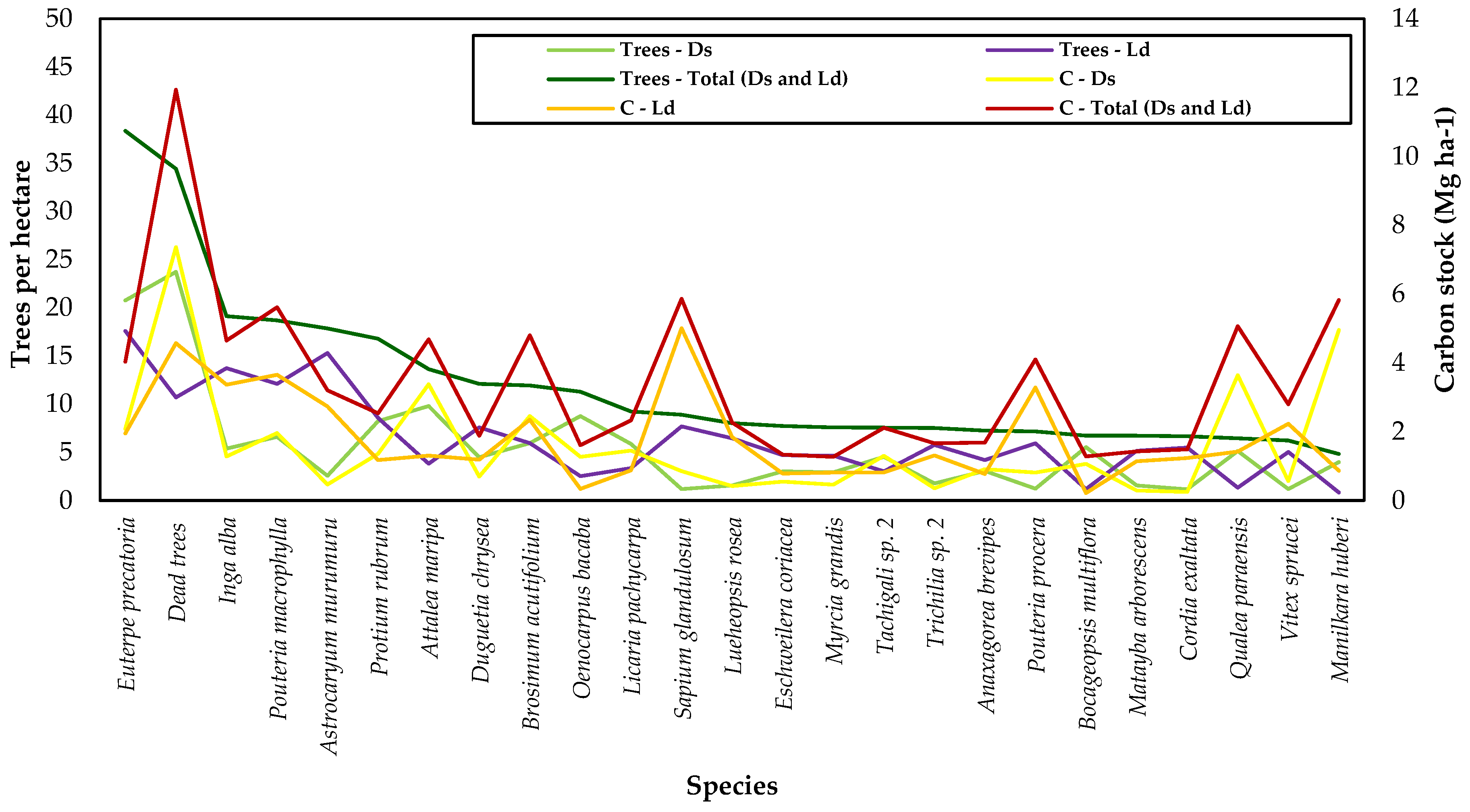

| 1º | Euterpe precatoria | 1,151 | 15.8 | 38.4 | 8.4 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 81.7 | 2.1 | 5.5 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 0.3 | 4.0 |

| 2º | Pouteria macrophylla | 561 | 23.9 | 18.7 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 3.8 | 75.0 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 0.7 | 5.6 |

| 3º | Inga alba | 574 | 19.4 | 19.1 | 4.2 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 85.0 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 4.7 |

| 4º | Brosimum acutifolium | 358 | 21.0 | 11.9 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 84.2 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 4.8 |

| 5º | Protium rubrum | 504 | 10.2 | 16.8 | 3.7 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 84.2 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 2.5 |

| 6º | Sapium glandulosum | 267 | 26.1 | 8.9 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 44.2 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 5.9 |

| 7º | Attalea maripa | 409 | 19.7 | 13.6 | 3.0 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 43.3 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 4.7 |

| 8º | Astrocaryum murumuru | 536 | 12.9 | 17.9 | 3.9 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 43.3 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 0.3 | 3.2 |

| 9º | Manilkara huberi | 145 | 27.3 | 4.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 36.7 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 1.2 | 5.8 |

| 10º | Qualea paraensis | 194 | 23.2 | 6.5 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 45.0 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 4.9 | 0.9 | 5.1 |

| Subtotal | 4,699 | 200 | 157 | 34 | 7 | 32 | 623 | 16 | 33 | 27 | 44.1 | 6.6 | 46.3 | |

| Other species* | 10,031 | 483 | 300 | 66 | 14 | 68 | 3,358 | 84 | 67 | 73 | 95.4 | 14.8 | 99.8 | |

| Total (Ds and Ld) | 14,730 | 683 | 457 | 100 | 21 | 100 | 3,980 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 139.5 | 21.3 | 146.0 | |

| Authors | Brazilian Legal Amazon | Ds | LO | Ld | H’ | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condé et al., 2025 (This study) |

Rorainópolis-RR | X | 4,43 | 75,27 | ||

| X | 4,26 | 57,23 | ||||

| Condé e Tonini (2013) | Caracaraí-RR | X | 3,27 | - | ||

| Alves e Miranda (2008) | Almeirim-PA | X | 4,25 | - | ||

| Oliveira et al. (2008) | Manaus-AM | X | 5,10 | - | ||

| Miranda (2000) | Pimenta Bueno-RO | X | 3,88 | - | ||

| Oliveira e Mori (1999) | Projeto Dinâmica Biológica de Fragmentos Florestais (PDBFF) próximo à Manaus-AM | X | - | 205,08 | ||

| Amaral (1996) | Região do Rio Urucu-AM | X | - | 140,51 | ||

| Tello (1995) | Manaus-AM | X | - | 53,01 |

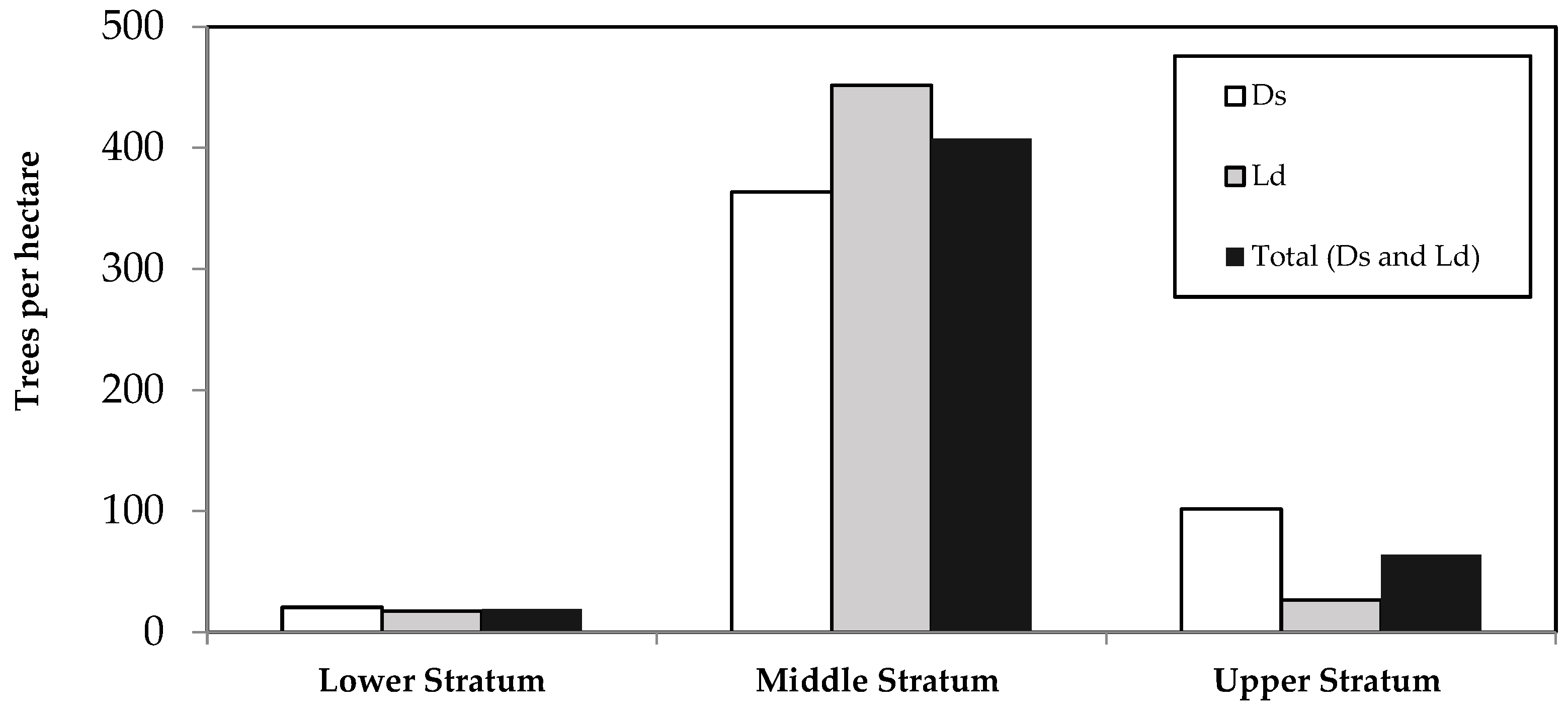

| Forest physiognomies | Stratum (ha) | Trees | BA | V | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ha) | (m² ha-1) | (106 m²) | (m³ ha-1) | (106 m³) | ||||||||||||

| Ds | 71.161 | 486 | ± | 21 | 23,2 | ± | 1,1 | 1,7 | ± | 0,1 | 192,9 | ± | 10,9 | 13,7 | ± | 0,1 |

| Ld | 116.907 | 496 | ± | 23 | 22,3 | ± | 1,3 | 2,6 | ± | 0,1 | 162,6 | ± | 10,4 | 19,0 | ± | 0,9 |

|

Total (Ds and Ld) |

188.068 | 492 | ± | 16 | 22,6 | ± | 0,8 | 4,3 | ± | 0,2 | 174,1 | ± | 7,4 | 32,7 | ± | 1,4 |

| Forest physiognomies | Stratum (ha) | Biomass | |||||||||||||||||

| AGB | BGB | B | |||||||||||||||||

| (Mg ha-1) | (106 Mg) | (Mg ha-1) | (106 Mg) | (Mg ha-1) | (106 Mg) | ||||||||||||||

| Ds | 71.161 | 322,3 | ± | 14,2 | 22,9 | ± | 0,1 | 49,8 | ± | 3,5 | 3,5 | ± | 0,1 | 332,3 | ± | 14,2 | 23,6 | ± | 0,1 |

| Ld | 116.907 | 213,9 | ± | 21,7 | 25,0 | ± | 1,5 | 26,4 | ± | 4,0 | 3,1 | ± | 0,3 | 245,1 | ± | 25,8 | 28,7 | ± | 1,8 |

|

Total (Ds and Ld) |

188.068 | 254,9 | ± | 13,3 | 47,9 | ± | 2,5 | 35,3 | ± | 2,7 | 6,6 | ± | 0,5 | 278,1 | ± | 15,0 | 52,3 | ± | 2,8 |

| Forest physiognomies | Stratum (ha) | Carbon | |||||||||||||||||

| AGC | BGC | C | |||||||||||||||||

| (Mg ha-1) | (106 Mg) | (Mg ha-1) | (106 Mg) | (Mg ha-1) | (106 Mg) | ||||||||||||||

| Ds | 71.161 | 156,3 | ± | 6,9 | 11,1 | ± | 0,1 | 24,2 | ± | 1,7 | 1,7 | ± | 0,1 | 161,2 | ± | 6,9 | 11,5 | ± | 0,1 |

| Ld | 116.907 | 101,6 | ± | 10,3 | 11,9 | ± | 0,7 | 12,5 | ± | 1,9 | 1,5 | ± | 0,2 | 116,4 | ± | 12,2 | 13,6 | ± | 0,8 |

|

Total (Ds and Ld) |

188.068 | 122,3 | ± | 6,3 | 23,0 | ± | 1,2 | 16,9 | ± | 1,3 | 3,2 | ± | 0,2 | 133,3 | ± | 7,2 | 25,1 | ± | 1,4 |

| NTFPs | Category 1: Palm trees and juvenile trees with a diameter between 10 < DBH < 31.8 cm | ||||||||||||

| Forest physiognomies | Juvenile trees | Juvenile commercial volume | |||||||||||

| ha (m³) | Stratum (106 m³) | ha (m³) | Stratum (106 m³) | ||||||||||

| DS | 422.3 | ± | 20.8 | 30.1 | ± | 0.1 | 77.6 | ± | 2.8 | 5.5 | ± | 0.1 | |

| LD | 431.3 | ± | 22.4 | 50.4 | ± | 1.8 | 74.1 | ± | 3.9 | 8.7 | ± | 0.3 | |

| Total (Ds and Ld) | 427.9 | ± | 15.3 | 80.5 | ± | 2.9 | 75.4 | ± | 2.5 | 14.2 | ± | 0.5 | |

| NTFPs and TFP | Category 2: Pre-harvestable trees with a diameter between 31.8 < DBH < 50.0 cm | ||||||||||||

| Forest physiognomies | Pre-exploitable trees | Volume comercial pré-explorável | |||||||||||

| ha (m³) | Stratum (106 m³) | ha (m³) | Stratum (106 m³) | ||||||||||

| DS | 42.5 | ± | 4.0 | 3.0 | ± | 0.1 | 42.4 | ± | 4.1 | 3.0 | ± | 0.1 | |

| LD | 48.5 | ± | 4.8 | 5.7 | ± | 0.4 | 43.4 | ± | 4.5 | 5.1 | ± | 0.4 | |

| Total (Ds and Ld) | 46.2 | ± | 3.1 | 8.7 | ± | 0.6 | 43.0 | ± | 3.0 | 8.1 | ± | 0.6 | |

| TFP | Category 3: Exploitable trees with DBH > 50.0 cm | ||||||||||||

| Forest physiognomies | Explorable trees | Exploitable commercial volume | |||||||||||

| ha (m³) | Stratum (106 m³) | ha (m³) | Stratum (106 m³) | ||||||||||

| DS | 21.2 | ± | 2.4 | 1.5 | ± | 0.1 | 72.9 | ± | 11 | 5.2 | ± | 0.1 | |

| LD | 16.2 | ± | 2.3 | 1.9 | ± | 0.2 | 45.1 | ± | 9.1 | 5.3 | ± | 0.8 | |

| Total (Ds and Ld) | 18.1 | ± | 1.6 | 3.4 | ± | 0.3 | 55.6 | ± | 7.0 | 10.5 | ± | 1.3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).