Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 40A05; 46A45; 26A03; 05C20

1. Introduction

1.1. Real Valued Sequences

1.2. Motivation

1.3. Study Outline

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Set-Theoretic Foundations

- 1.

- The sequence is non-decreasing and is non-increasing.

- 2.

- For every :

- 3.

-

The limitsalways exist in .

- 4.

- We always have the inequality

- (i)

- If the (finite) limit exists and is equal to , then

- (ii)

- Conversely, if , then converges to L, that is,

- (iii)

- If , then the sequence does not converge in ; in this case is either divergent to or oscillatory between at least two distinct cluster values.

2.2. Linear-Algebraic Foundations

- (i)

- The elements of B are linearly independent.

- (ii)

- Every element can be written as a finite linear combination of elements of B; that is,for some , scalars , and distinct .

- If such a set B exists, the cardinality is called the (Hamel) dimension of X.

- the algebraic viewpoint, where has a Hamel basis of cardinality , and

- the analytic viewpoint, where familiar sequence spaces admit countable Schauder bases describing their elements through convergent series.

- Our classification of into seven macroscale blocks will be constructive and finitary in spirit, and will be independent of any particular choice of Hamel or Schauder basis.

2.3. Special Sequences

- (A)

- has and finite;

- (B)

- has finite ;

- (C)

- has finite and ;

- (D)

- has and .

- Here and denote, respectively, the lim inf and lim sup of the corresponding sequence.

- (A–pattern). Define c byThen for all k and for . Hence b has a subsequence equal to and infinitely many zeros, so

- (B–pattern). Split S into two infinite subsequences, for instanceDefine b byand then set whenever , and when . By construction b takes the values infinitely often (and 0 possibly as well), henceso and are finite with .

- (C–pattern). Choose any infinite subsequence and defineand again put when , when . Then while for infinitely many n, so

- (D–pattern). Using the same partition as above, defineand set for , when . Then b has subsequences and , hence

3. Main Results

3.1. Partition of with Scenario Classification & Examples

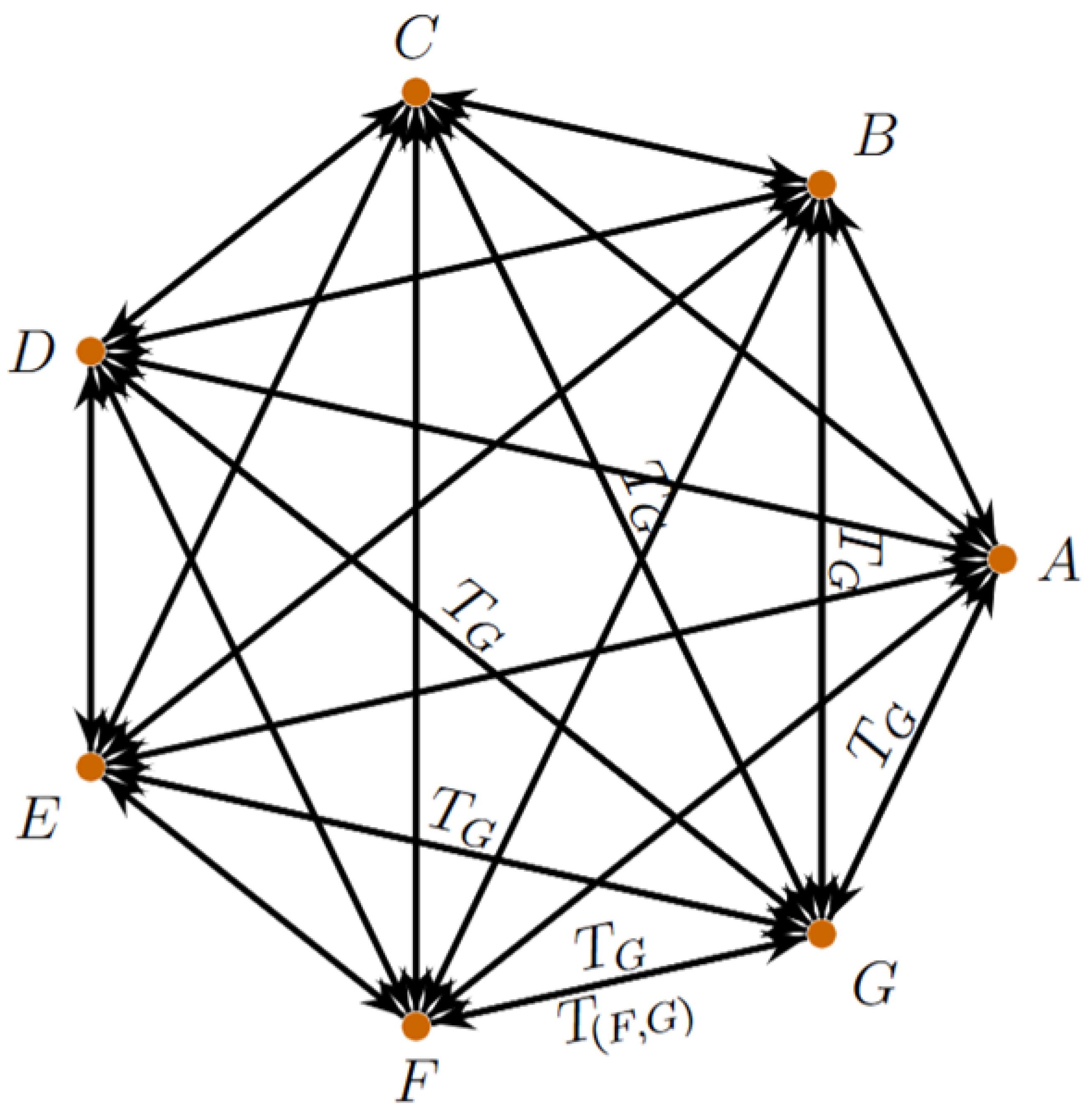

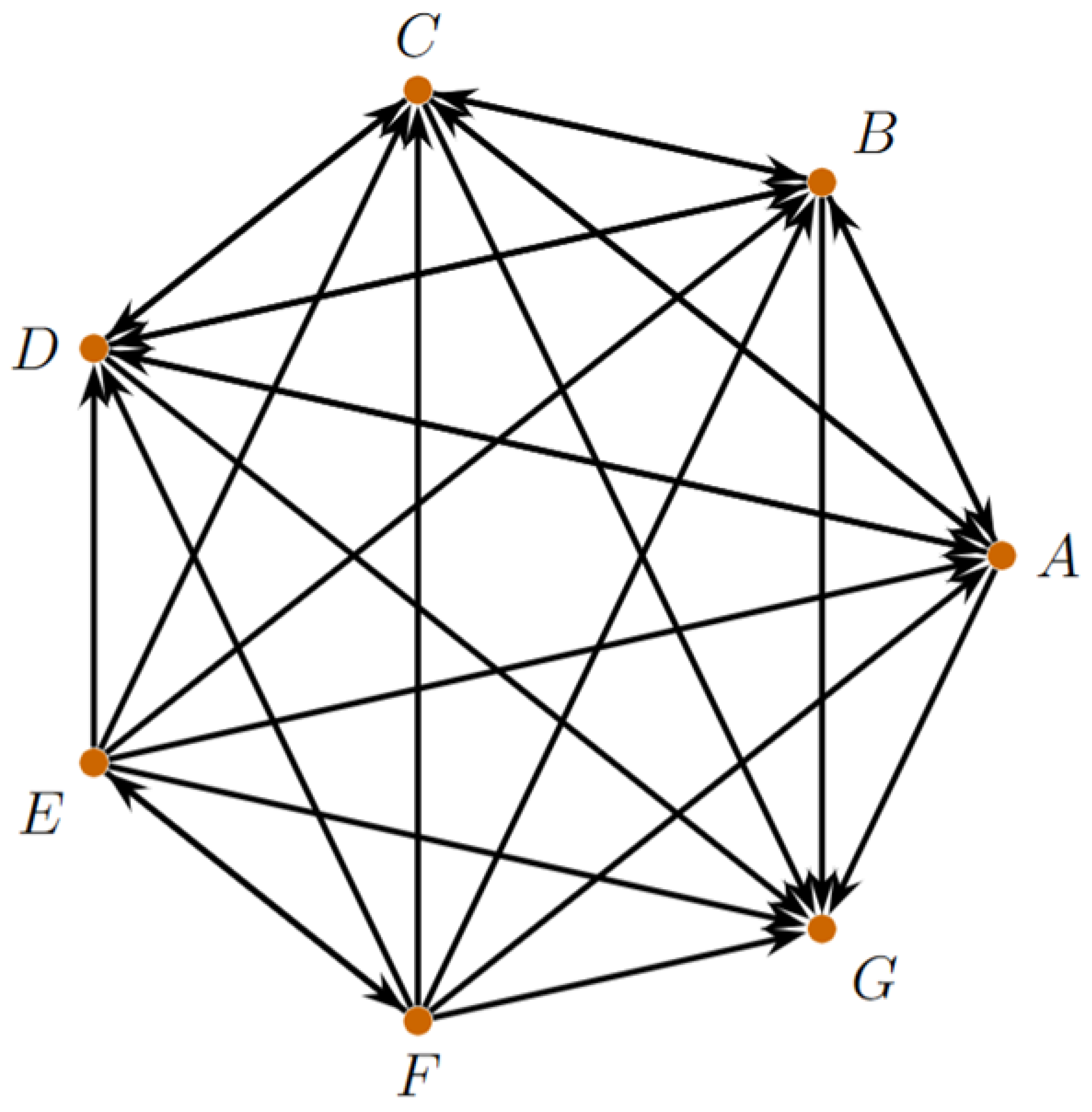

3.2. The Relationship between the Blocks

3.2.1. Macroscale

- (i)

-

Target G ().Then is constant, hence in G.

- (ii)

-

Target F ().Clearly , so .

- (iii)

- Target E ().so and .

- (iv)

-

Target D ().Along even indices the sequence tends to ; along odd indices it tends to , so .

- (v)

-

Target C ().Then and , so and , hence .

- (vi)

-

Target B ( ). Defineand setThen and with , so .

- (vii)

-

Target A ().Then and , so and ; hence .

- For , for any n.

- For , .

- For , .

- For , .

- For , .

- For , .

- For , .

- Thus if , then the corresponding codes coincide: . Since is injective, implies . Hence each is a one-to-one map.

3.2.2. Microscale

- Case (finite limit). By definitionGiven any , choose the constant connector . Then for all n, so is the constant zero sequence and hencethat is, . Since a was arbitrary, we obtain for every . Restricting to distinct blocks, all six implications with are true.

- Case (). Herewe need the product to diverge to .

- Positive result. If , then , so eventually. With the constant connector we have , and thereforeso for every . Thus .

- Negative results. By Lemma 2.11, if a sequence has infinitely many zeros then no Hadamard product with it can belong to F (its liminf and limsup cannot both be ). Hence, if a block X contains even one sequence with infinitely many zeros, then : taking that particular witnesses the failure of the definition of .

- in A: for odd n, for even n. Then , , and a has infinitely many zeros;

- in B: for even n, for odd n, so , ;

- in C: for odd n, for even n, so , ;

- in D: for example , , (), so , ;

- in G: the constant zero sequence has .

- In each case a has infinitely many zeros, so by Lemma 2.11 no connector c can produce . Thus

- Case (). This is completely symmetric to the previous case. We have

- Positive result. If (so ), the connector gives , henceand so for every . Thus .

- Negative results. We reuse exactly the same “infinitely many zeros’’ witnesses in listed above. For each such a no Hadamard product can have , again by Lemma 2.11. Consequently,

- Case (, ). HereBy the D–pattern in Lemma 2.12, for every with we can construct a connector c such that satisfieshence . Therefore,

- Case (). NowUsing the C–pattern in Lemma 2.12, we can, for every with , construct a connector c such thatso that . Hence

- Case (finite ). We haveBy the B–pattern of Lemma 2.12, for each with we can construct a connector c so that, for instance,and hence . Thus

- Case (, finite). Finally,Using the A–pattern in Lemma 2.12, we can, for every with , build a connector c such thatso that . ThereforeRestricting to distinct blocks, this yields for all .

-

Step 2: Summary of Cases Summarizing all implications, the adjacency matrix (rows = source X, columns = target Y) for distinctive pairs isand concretely:□

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary & Contributions

4.2. Comparison of Macroscale Matrix U versus Microscale Matrix V

4.3. Limitations & Future Work

4.4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

- c: cardinality of the continuum; HamSim: Hamming similarity; JacSim: Jaccard similarity; lim inf: limit inferior; lim sup: limit superior; N: set of natural numbers; R: set of real numbers; Seq(R): sequence space.

References

- Grabiner, J. V. (1981). The origins of Cauchy’s rigorous calculus. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. ISBN 0-486-43815-5.

- Rogers, R. R., & Boman, E. (2014). How we got from there to here: A story of real analysis. Open SUNY Textbooks, Geneseo, NY, USA. ISBN: 978-1-312-34869-1.

- Deshpande, J. V. (2004). Mathematical analysis and applications: An introduction. Alpha Science International. Harrow, UK. ISBN 1-84265-189-7.

- Hunter, J. K. (2014). An introduction to real analysis. University of California, Davis, CA, USA.

- Loku, V., & Braha, N. L. (2024). Basic concepts of mathematical analysis. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Lady Stephenson Library, UK. ISBN 978-1-0364-1086-5.

- Tao, T. (2016). Analysis I (3rd ed.). Springer. Hindustan Book Agency, New Delhi, India. ISBN 978-981-10-1789-6.

- Soltanifar, M. (2023). A Classification of Elements of Function Space F(R,R). Mathematics, 11(17), 3715. [CrossRef]

- di Dio, P. J., & Langer, L.-L. (2025). The Hadamard product of moment sequences, diagonal positivity preservers, and their generators. Integral Equations and Operator Theory, 97, 32. [CrossRef]

- Levy, A., Shalom, B. R., & Chalamish, M. (2025). A guide to similarity measures and their data science applications. Journal of Big Data, 12, 188. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, N., Kajikawa, Y., & Sakata, I. (2012). Link prediction in citation networks. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(1), 78–85. [CrossRef]

- Leskovec, J., Rajaraman, A., & Ullman, J. D. (2020). Mining of massive datasets (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H., Liu, Y., Caglar, T., Cole, C. M., Blanchard, N., Peterson, C., & Kirby, M. (2023). Hamming similarity and graph Laplacians for class partitioning and adversarial image detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW) (pp. 590–599). IEEE. [CrossRef]

| # | Block | Definition of | Representative sequence | Size |

| 1 | A | continuum | ||

| 2 | B | continuum | ||

| 3 | C | continuum | ||

| 4 | D | continuum | ||

| 5 | E | continuum | ||

| 6 | F | continuum | ||

| 7 | G | continuum |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).