1. Introduction

Spinal cord (SC) injury (SCI) is a debilitating condition that leads to severe neurological disorders [

1]; worldwide, between 250,000 and 500,000 people suffer SCI every year [

2]. The pathophysiological mechanisms which are triggered after SCI are complex [

1]. The spectrum of functional disorders caused by SCI may result not only due to direct traumatic damage of SC, but also as a consequence of subsequent ascending and descending neurodegeneration, deafferentation, loss of voluntary control, cerebrospinal fluid circulation disorders, etc. [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Due to the insufficient effectiveness of existing treatment methods and the extremely high disability impact of SCI, many regenerative technologies are being developed as a potential curative approach to SCI, requiring adequate preclinical testing [

8].

Epidural electrical stimulation (EES) of the SC is a well-established method of neuromodulation that is currently used in clinical practice to alleviate the effects of SCI: in chronic pain [

9], improvement of non-motor functions [

10] and in studies focusing on the rehabilitation of the musculoskeletal system after SCI, both in animals [

11,

12,

13,

14], as well as in humans [

15,

16,

17]. The effectiveness of EES in restoring lost functions after SCI is due to stimulation of the posterior roots in the lumbar thickening of the SCI and activation of the gait generator [

16,

17,

18,

19]. In addition, in recent years, the field of research on animal models combining SC electrical stimulation with other therapeutic interventions has been expanding [

20]. However, despite significant advances in EES research, uncertainty remains regarding the transferability of these results to clinical practice.

Rodent models have become widely used in biomedical research aimed at studying pathophysiological processes [

21]. For example, it has been shown in rats that EES of the lumbar spinal cord can lead to the activation of synergistic muscle groups, providing locomotion close to natural [

22,

23]. In this experimental model, electrical stimulation of the spinal cord is usually performed using an external stimulator attached via a special connector on the animal’s head (“head plug”), and electrodes in the form of wires are connected to the lumbar region of the spinal cord [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Using a rodent model of SCI, significant progress has been made in understanding the basic mechanisms of plasticity in the SC modulated through EES [

25].

To translate the latest advances in neuromodulation and gene-cell technologies into clinical medicine, testing novel therapies on large mammals, most relevantly non-human primates (NHPs), is a necessary link between the rat model and humans. The SC of NHPs is anatomically and physiologically similar to the human SC, especially in terms of the topography of the conduction pathways and the function of the corticospinal tracts [

28]. Without experimental research on primates, it is impossible to develop neurotechnology involving the implantation of invasive cortical electrodes and the creation of control neurointerfaces. At the same time, when modeling SC pathology in NHPs and developing methods of therapy, the high level of development of higher nervous activity in these animals should be taken into account. Therefore, minimally invasive methods of implantation of epidural and myographic electrodes are used to assess the neurophysiological and locomotor consequences of SCI and the effectiveness of the methods used to treat it.

The aim of this study was to develop a bioethically acceptable platform for research on NHP using minimally invasive methods of implantation of epidural and myographic electrodes (both wireless and wired, connected via a head plug) to assess the neurophysiological and locomotor consequences of SCI and the effectiveness of the methods used to treat it.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Care

All experiments on NHP were conducted in Kurchatov Medical Primatology Center in Sochi, Russia. The animals for the study were selected from 20 male rhesus macaques aged 2-4 years and weighing up to 5 kg, which had been previously removed from the enclosure and placed in cages. Of these 20 animals, the 5 most suitable for the study, which showed the best quadrupedal walking skills on the treadmill, were selected. The selected animals were kept in conditions of natural lighting (at least 12 hours per day) with free access to water and fed twice daily in spacious cages with enriched media. All manipulations with animals were carried out in accordance with the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (European Treaty Series - No. 123, Strasbourg, 18.III.1986; Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes). The experiment protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the NRC Kurchatov Institute (Protocol No. 02-2 from 20.03.2025). The monkeys developed the necessary motor skills in their lower and upper limbs, after which electrodes were implanted and spinal trauma was simulated. During the experiment, two animals were excluded from the study due to the failure of the implanted devices. As a result, three animals underwent a complete neurophysiological examination.

2.2. Electromyography Wire and Electrode Implants

We developed an implantable system for simultaneous recording of motor activity and spinal cord stimulation. To connect the EMG equipment and stimulators to the implantable electrodes, head plugs were manufactured, including connectors (one 12-pin and one 16-pin, A22004-001 (MCP-12-SS) and A22032-001 (MCP-16-SS), Omnetics Connector Corp., USA) and microcables in multi-strand steel insulation (AS632, Cooner Wire, CA) as electrical conductors (

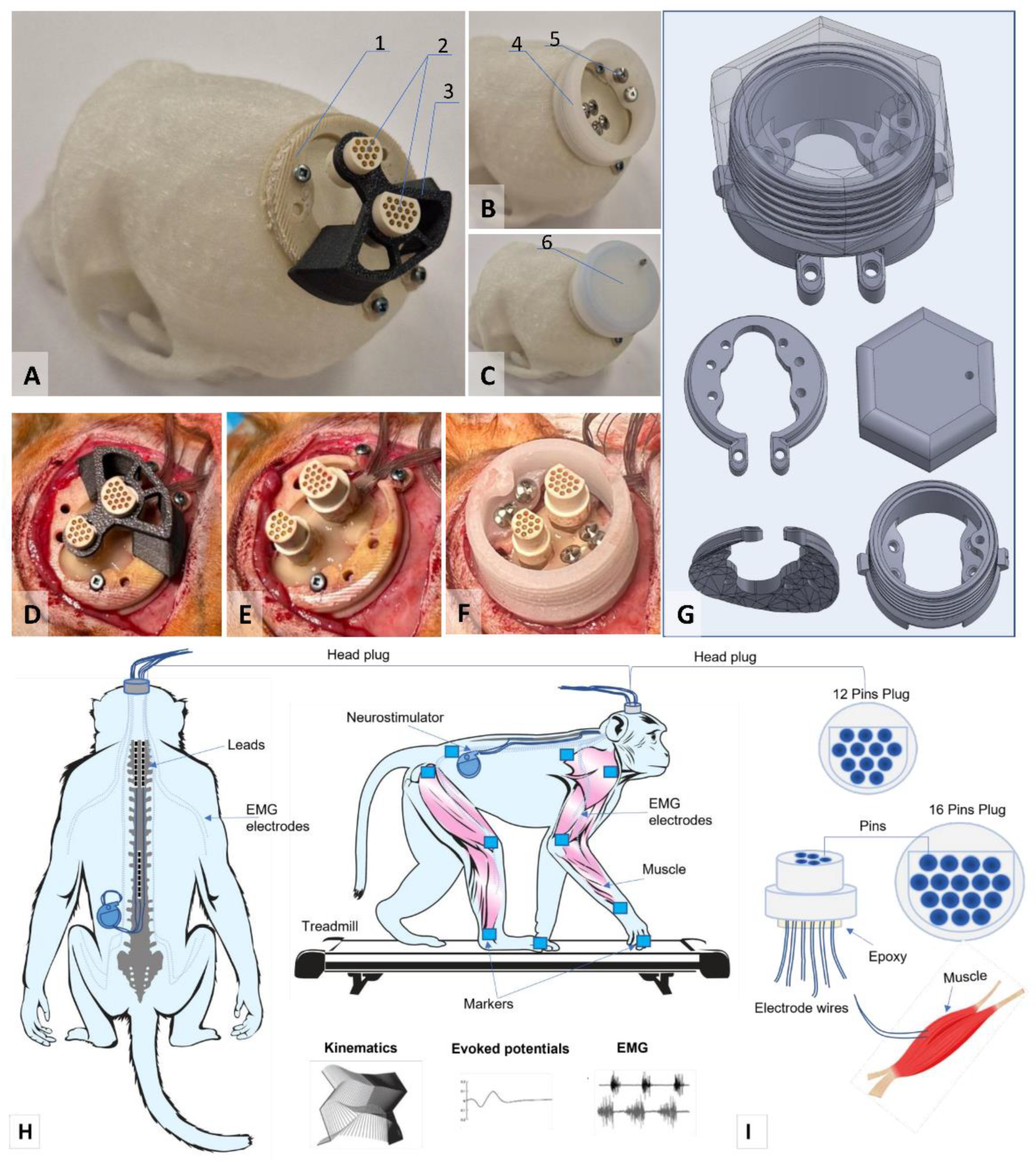

Figure 1A-C).

The lengths of the wires for implantation were calculated based on measurements of the research objects. The calculation of the lengths of the wires for implantation was performed using a multi-stage scheme, taking into account the dimensions of the research object.

The design of the connectors attached to the skull of the research object included a box with a hermetically sealed space, fixed to the bone tissue using a light-curing biocompatible dental composite. This head-plug design allows microcontacts to remain in working order and ensures easy connection to the mating parts of these connectors for connection to EMG recording equipment and stimulators. As a result of initial tests of the box for plugs attached to the bones of the cranial vault, it was decided to develop a second generation of the box made of osteoinductive material, which ensured reliable fixation of the box to the cranial vault with bone ingrowth (

Figure 1c).

The implantation kit consisted of two parts: insulated electrical wires soldered to a connector (plug) and a container. The wires were connected to the plug using low-temperature solder (POS-61), followed by insulation of the solder joints with epoxy glue. During implantation, the plug itself, as well as the part covered with glue, was insulated from biological tissues by the container material, the outer part of which was made of a biocompatible composite. The material of the implanted wires (Hookup Wire, Stranded Stainless Steel, model AS 632, Cooner Wire Company, USA) is a stainless-steel core insulated with fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP). The wire is made in the form of a single-core twist based on ultra-thin filaments (15 pcs) in a common outer insulation. The outer diameter of the wire in insulation is 0.3 mm, impedance 1 Ohm/cm. The design, including wires and contact plugs, was manufactured in the neuro-regeneration laboratory of the Federal Medical Biological Agency of Russia. The osteoinductive head-plug was developed and manufactured at the Institute of Biomedical Engineering, National University of Science and Technology MISIS (patent RU 2 829 633 C1, 26.06.2024 https://www.fips.ru/cdfi/fips.dll/ru?ty=29&docid=2829633).

2.3. Electrodes Implantation

The electrode implantation technique was adapted for primates based on a previously used implantation technique in rodents [

24,

25,

29,

30]. After making an incision in the skin in the projection of the parietal bone perpendicular to the midline suture of the skull, the muscles and fascia were retracted laterally, and the skull was thoroughly cleaned and dried. In several stages, a head plug was installed on the skull according to the developed installation technology (

Figure 1) using self-tapping screws (Conmet, Russia) and medium-flow light-curing dental composite. Through additional incisions on the neck and back, wires were distributed subcutaneously to the corresponding muscles using special introducers. Incisions were made in the skin in the projection of the muscles under study, and the fascial sheaths of m. biceps brachii (BIC), m. triceps brachii (TRIC), m. flexor digitorum superficialis (FLE), m. extensor carpi ulnaris (EXT), m. rectus femoris (RF), m. biceps femoris (BF), m. tibialis anterior (TA), and m. gastrocnemius medianus (GM). Bipolar intramuscular EMG electrodes were inserted into the muscles through small incisions in the fasciae and fixed with polyfilament non-absorbable sutures using the technique described earlier [

26]. All EMG wires had additional length, from which subcutaneous realizing loops were formed and laid around each implantation site to avoid mechanical tension/stress on the wires during the animal’s movements and growth. To verify the correct placement of the electrodes in each muscle, electrical stimulation was performed through the head plug with visual control of muscle contraction and impedance recording. Test electrical stimulation was performed using a NeoStim 5 multichannel stimulator (KOSIMA, Russia), connected to the head plug via wired connections.

For epidural stimulation of animals, we used rod electrodes and implantable Precision Spectra generators (Boston Scientific, USA). With the animal in the prone position, a linear incision was made along the midline of the lumbar spine in the S1-L4 projection. Under X-ray guidance, the epidural space was punctured with a Tuohy needle, and two cylindrical electrodes were sequentially inserted into the posterior epidural space and placed in the projection of the DREZ zone at the level of the C2 -C7 vertebrae on the left and right sides (

Figure 1H). A third cylindrical electrode was placed in the posterior epidural space along the midline at the level of Th10-L2. The needle was removed, and the electrodes were fixed to the aponeurosis. A subaponeurotic pocket was formed for the pulse generator on the left. The permanent neurostimulation system is mounted, the generator is placed in the pocket and fixed with knot sutures. The electrode loops are placed and additionally fixed with threads to the aponeurosis. To record artifacts in the electrode projection, two wires with a removed Teflon coating exposing 1.0–1.5 mm of wire were inserted under the skin. Another wire with an exposed distal end (about 1 cm) was placed circularly subcutaneously in the lumbar region and served as a common ground [

25].

2.4. Spinal Cord Injury

To avoid aspiration complications, food was discontinued at least 12 hours before induction of anesthesia, and drinking was discontinued 4 hours before. To ensure neuroleptanalgesia, for the safe removal of animals from the enclosure and further preoperative preparation, Relanium (1 mg/kg) and Ketamine (10 mg/kg) were administered intramuscularly into the quadriceps muscle of the thigh; Once the desired anesthetic effect was achieved (5-10 minutes), with spontaneous, adequate breathing maintained, the animal was removed from the enclosure and transported to the preoperative room. A veterinary clipper was used to remove the hair on the back and limbs. Under aseptic conditions, a 20G catheter was inserted into the subcutaneous vein of the lower leg. For the purpose of desensitization, multimodal analgesia, and achieving adequate perioperative hemostasis, 20 minutes before surgery, Ketonal 10 mg/kg, Dexamethasone 1 mg/kg, and Tranexamic acid 20 mg/kg were administered 20 minutes before surgery. Rapid sequential induction of general anesthesia was performed against a background of preliminary oxygenation and administration of Fentanyl 25 mcg/kg, Propofol 5-10 mg/kg, and Rocuronium 2.5-3 mg/kg. Once adequate depth of anesthesia was achieved, orotracheal intubation was performed with a 4.0 tube, after which the animal was transferred to mechanical ventilation in a semi-closed circuit with the following parameters: tidal volume 120-150 ml, respiratory rate 23-26 per minute, FiO2 0.4. Anesthesia was maintained by bolus administration of fentanyl and inhalation of isoflurane 1.2-2.0 vol%.

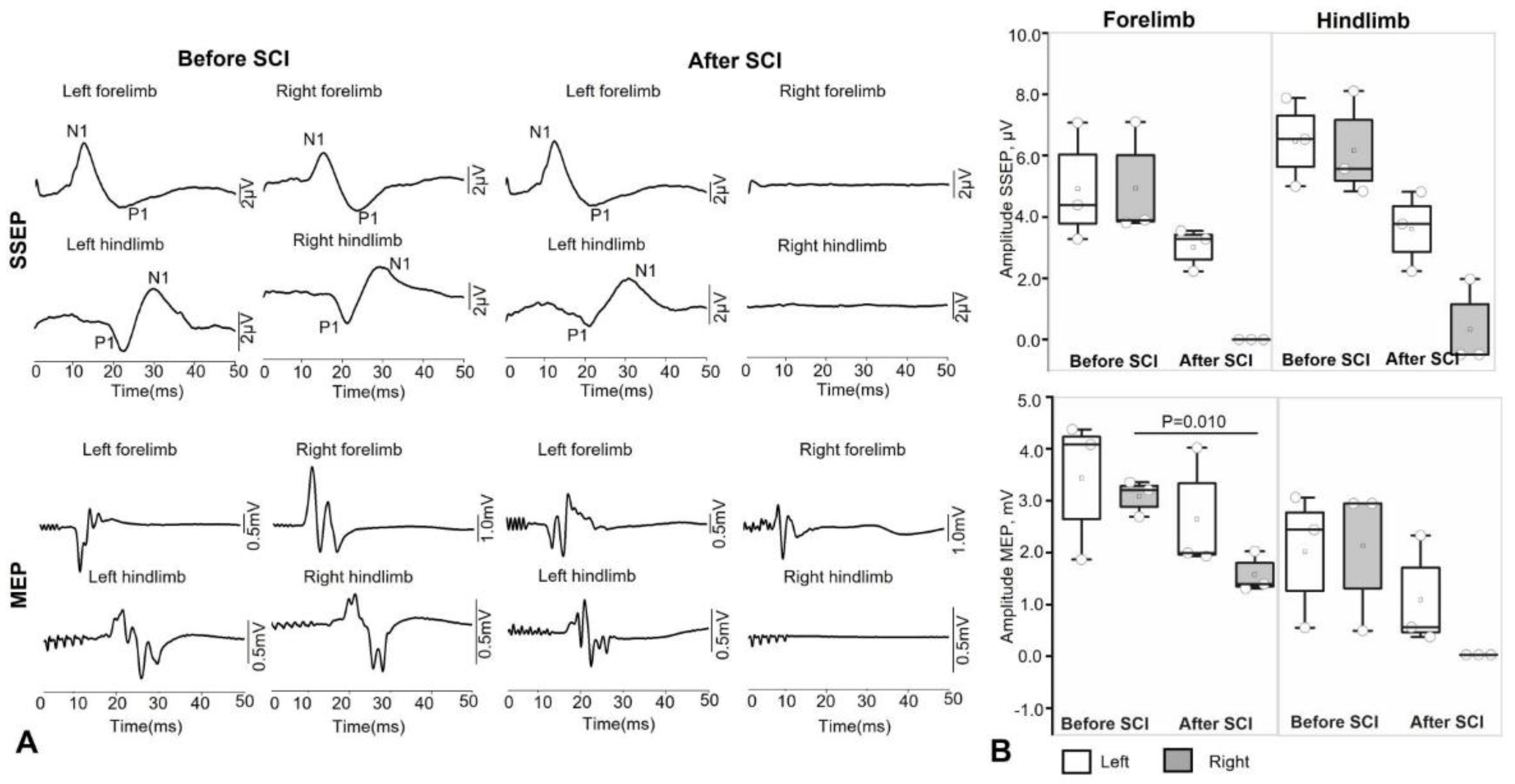

The surgical procedure was performed in a sterile operating room. Throughout the operation, the animals received infusion therapy with balanced crystalloid solutions at a rate of 10-15 ml/kg/hour, and their heart rate, blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and capnography were monitored. The monkeys were placed in the prone position, and their skin was wiped with Povidone-iodine. A 5 cm longitudinal midline skin incision was made in the projection of the spinous processes of the C3-C5 vertebrae, and the paraspinal muscles were separated subperiosteally. The spinous process of C4 was removed, and interlaminectomy was performed with partial removal of the C4-C5 vertebrae. The dura mater was exposed and longitudinally dissected in the projection of the C4-5 segment. Using a scalpel and microsurgical scissors under the control of an operating microscope and intraoperative recording of SSEP and MEP, a wedge-shaped hemisection of the spinal cord was performed on the right side. Upon receiving neurophysiological confirmation of the complete absence of afferent and efferent responses from the right half of the body, a hemostatic sponge was placed in the formed defect (2-3 mm) of the spinal cord. The DMSA was sutured and additionally sealed with a tachokomb. Hemostasis was performed, after which the dura mater was tightly sutured. The wound was sutured layer by layer and an aseptic dressing was applied.

At the end of the operation, when reflexes and independent adequate breathing were restored, the animals were transferred to independent breathing and extubated. In all cases, no significant episodes of hypotension and hypoxia were noted, blood loss was up to 50 ml and was considered insignificant. In the postoperative period, all animals received antibiotic therapy (Ceftriaxone, 50 mg/kg in a 0.5% solution of novocaine, intramuscularly, once a day). Pain was minimized by administering Ketonal (15 mg/kg) intramuscularly to the monkeys on the first day after surgery, followed by 10 mg/kg of Ketonal on the second and third days after surgery.

2.5. Electrophysiology Assessment

Intraoperative monitoring of motor and sensory fibers for the hind limbs of animals is performed throughout the surgical procedure by recording transcranial motor evoked potentials (MEP) and somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) using the Neuro-IOM Neurosoft system (Russia), with recording of indicators before and after the moment of injury.

The latency (primary positive/negative deviation) and amplitude (maximum peak-to-peak value) parameters of the muscle response are assessed for the m.abductor hallucis and m. abductor pollicis brevis on both sides, with an active electrode placed in the motor point area. The bandwidth was set at 10-1000 Hz. An assessment is also made as a percentage of the initial latency and amplitude values. Stimulation of the motor area is performed using a pair of needle electrodes at points corresponding to the C1–C2/C2–C1 leads according to the international EEG electrode placement system “10–20%.” The grounding electrode was placed in the m. biceps brachii. Train stimulation was performed with 5 pulses, an interstimulus interval of 2 ms, a duration of 200 μs each, and a voltage of up to 500 V. For each response recording, at least 3 consecutive stimulations were performed to increase reliability.

The presence of a response is assessed, as well as the amplitude and latency of the cortical SSEPs of the lower extremities in the form of the first positive (P1) and negative (N1) peaks. Alternate stimulation of the medianus and tibialis nerves on both sides in the area of the wrist joint and medial malleolus is performed using a pair of monopolar needle electrodes (cathode proximal) with the application of direct current pulses: with a duration of 200 μs and a frequency of 3.12 to 4.12 Hz, amplitude from 4 to 10 mA (supramaximal amplitude is selected until a stable response is obtained). To obtain a single SSEP result, an average of 50 to 250 stimuli is used (depending on the severity of the SSEPs). The SSEP response is recorded using a pair of needle electrodes from the surface of the head with Cz-Fz lead (“10-20%”).

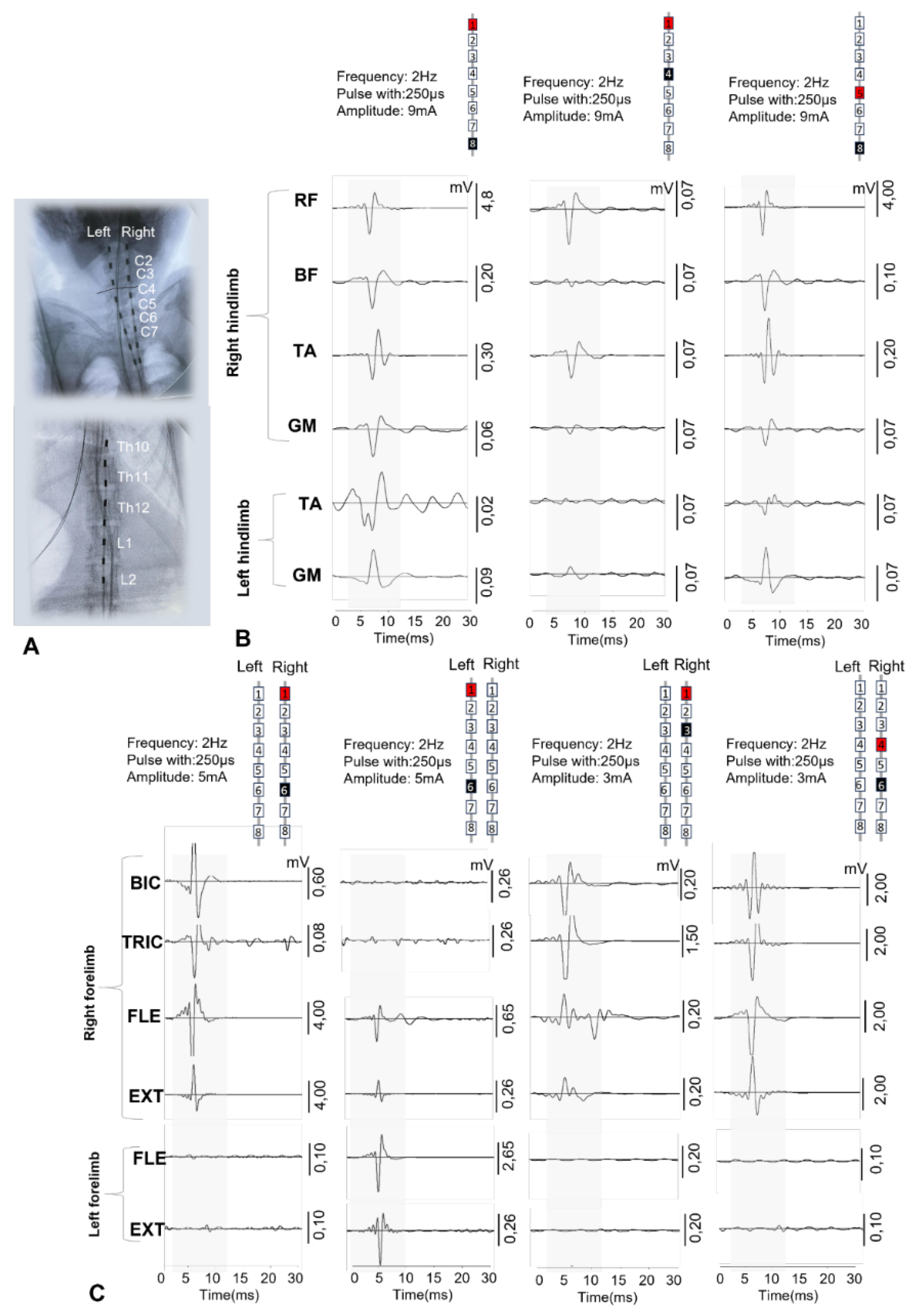

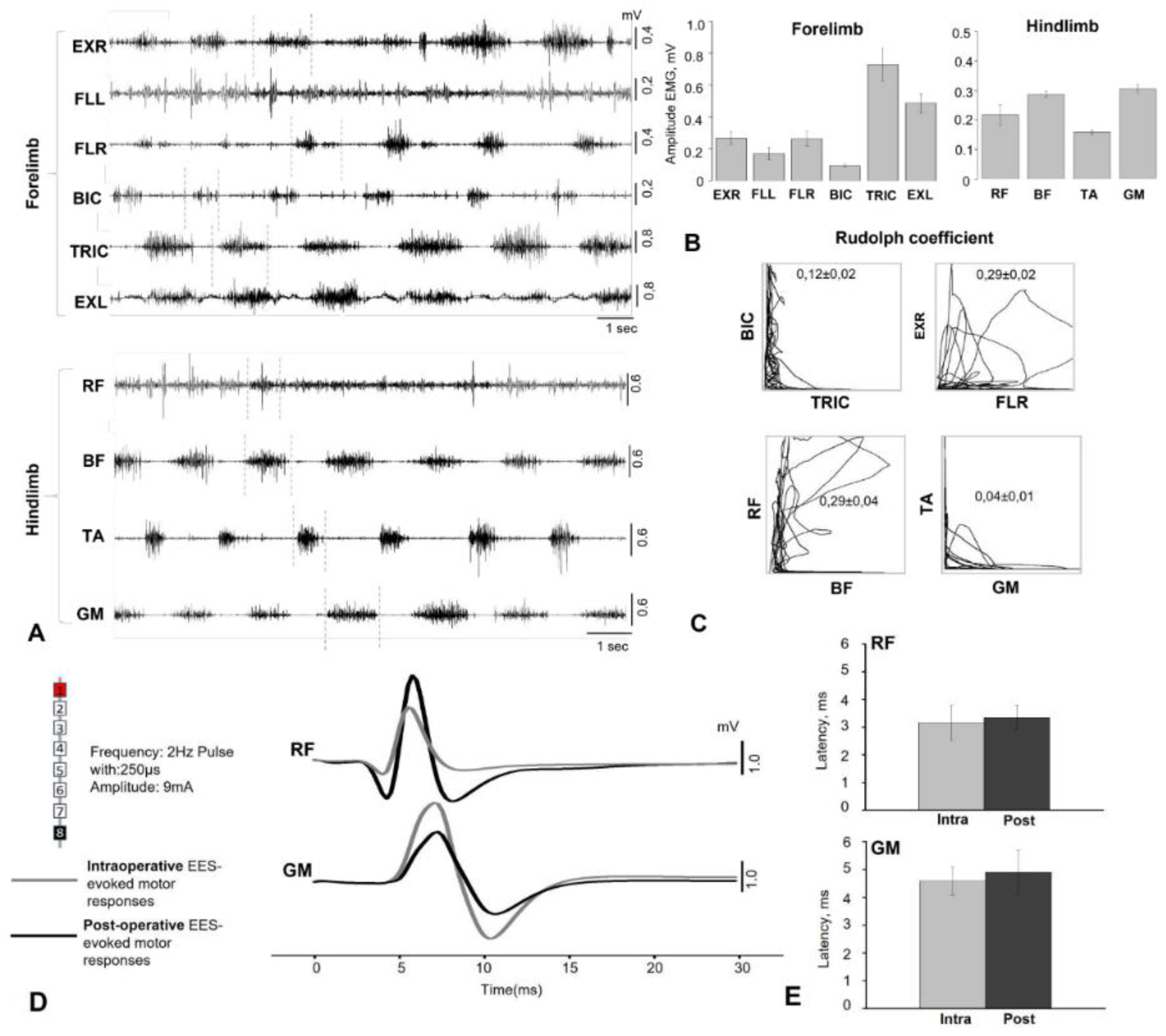

Electromyographic signals were recorded using bipolar electrodes implanted in the BIC, TRIC, FLE, EXT, RF, BF, TA, and GM. Electrophysiological recordings were performed during surgery to verify the spatial selectivity of the spinal implant and to precisely adjust its anatomical position. The delivery of a single current pulse (pulse duration 250 μs) 1.2–1.4 times higher than the motor threshold through the selected electrode contact causes motor responses in the leg muscles. EES-evoked responses include monosynaptic and polysynaptic components. EES was performed using a stationary implantable Precision Spectra generator (Boston Scientific, USA) and three rod electrodes placed at the cervical and lumbar levels as described above. EES-evoked responses at the cervical and lumbar levels were recorded using IDinstruments (USA) hardware and software and subcutaneous electrodes placed bipolarly above the motor point of the muscle. To determine the intensity of the stimulus required to elicit minimal limb muscle contractions (threshold) of responses, EES was performed with a duration of 250 μs, a frequency of 2 Hz, and a stimulus strength that varied in the range from 1 to 14 mA in 0.1 mA increments. EES-evoked motor response latencies were calculated as the time from stimulus pulse to the onset of the motor response of each muscle.

EMG and EES-evoked response data were collected at a sampling rate of 4 kHz (PowerLab; ADInstruments, Austin, TX) and analyzed using custom code written in Object Pascal, Free Pascal Compiler (v.2) for Microsoft Windows. Notch (50 Hz) and bandpass (20–1000 Hz) filters were applied to EMG recordings to reduce environmental artifacts.

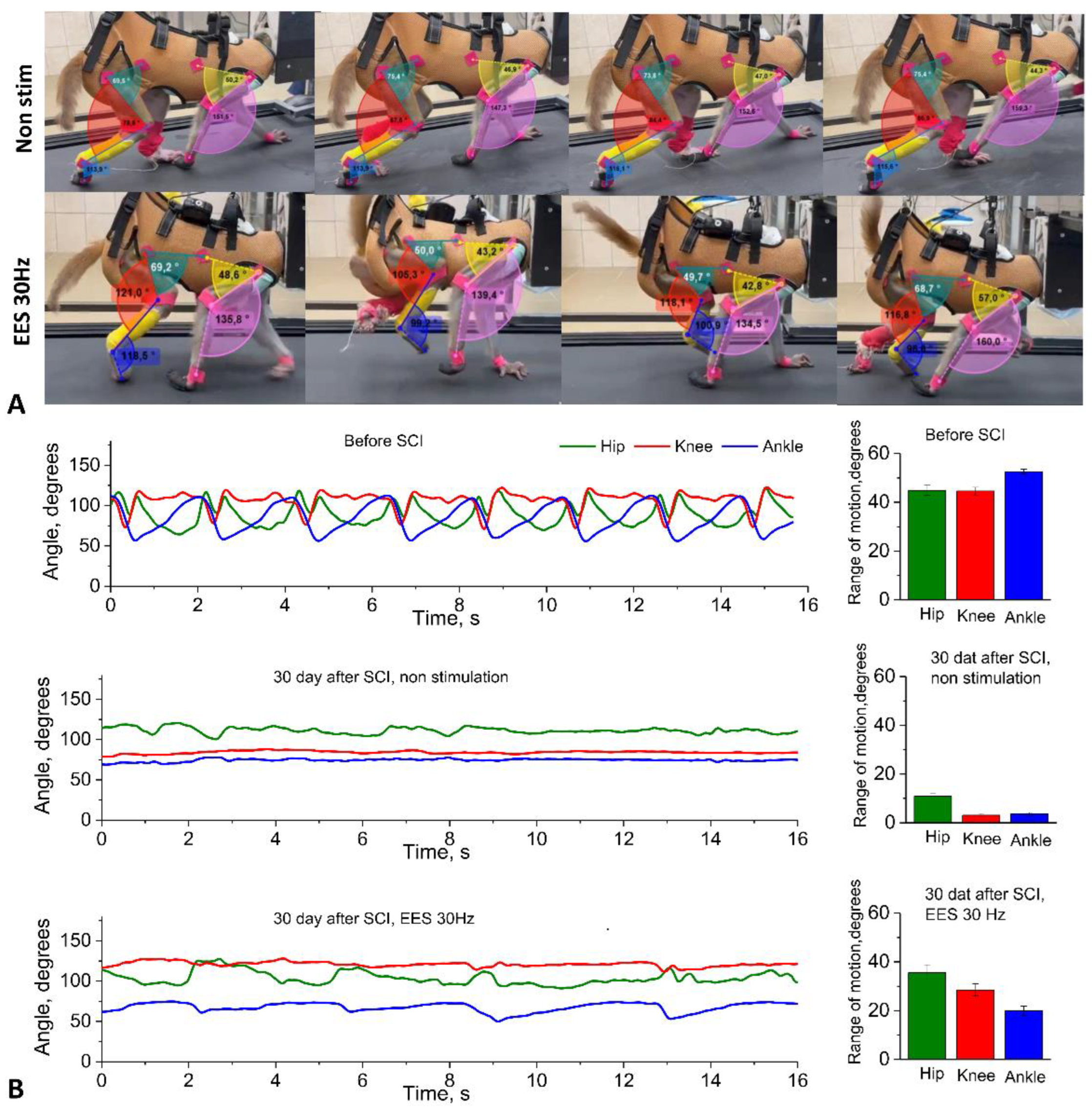

2.6. Kinematic Assessment

Within the framework of the platform we developed, we performed locomotion analysis - in an intact state, after electrode implantation (simultaneously with the recording of motor responses during walking) and in dynamics after spinal cord hemisection. The kinematic analysis consisted of assessing the range of motion in the joints while moving on a treadmill on four limbs with the head fixed using a special collar attached to the treadmill frame (see Supplementary Video 1). Fresh fruit (small pieces of apples, bananas, grapes) was offered to the animal as a reward during locomotion on the treadmill.

Gait registration was performed by filming the animal from two sides (left/right) followed by instrumental analysis of the angles in the limb joints using free Kinovea software by marking video frames. Based on tables containing frame-by-frame angle values for a time interval with several steps of the research object, the volumes of angular movement for three leg joints (hip, knee, and ankle) and two front limb joints (elbow and shoulder) were calculated using our original NeuroKin software (Certificate of registration of a computer program No. RU 2024692126, 26.12.2024,

https://www.fips.ru/registers-doc-view/fips_servlet). The range of angular motion in the joints was calculated as the difference between the maximum and minimum angles in the joint during the step phase, based on the analysis of intervals including approximately 1.5 steps (intervals known to be longer than the duration of one step, automation algorithm). Then, the average values for several steps were calculated for a standard recording interval of about 1 minute (average joint movement volumes: M±sem).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard error (M±sem) values were calculated from five consecutive stimuli. The Shapiro-Wilk method was used to test for normal distribution of data. For normally distributed data, statistically significant differences between response amplitudes and latency were calculated using standard parametric t-tests to compare muscle activity.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that minimally invasive implantation of epidural electrodes with a wireless stimulator, along with implantation of invasive myographic electrodes followed by hemisection of the spinal cord at the cervical level, is an ethically acceptable platform for studying the neurophysiological mechanisms of neuromodulation in the treatment of SCI in NHP. This platform is easy to implement, allows for the assessment of kinematics and myography in motion, and can be combined with various treatment options, such as neural progenitor cell transplantation, implantation of various biocompatible scaffolds, gene therapy using AAV, implantation of cortical grids, and development of BCI, etc.

More than twenty years of preclinical and clinical research have shown that EES at the lumbosacral level of the spinal cord can promote the activation of spinal locomotor circuits after SCI [

16,

17,

31,

32]. Using computer modeling [

33,

34,

35] and experimental studies conducted on animal models and humans with spinal cord injury [

36,

37], it has been convincingly proven that electrical stimulation of the spinal cord at the lumbosacral level primarily involves large myelinated afferent fibers passing through the dorsal roots of the spinal cord [

38]. Spinal cord electrical stimulation thus not only activates the spinal cord networks responsible for locomotion through interneurons and motor neurons in the lumbar thickening [

39], but also to modulate the spinal cord network in people after SCI [

40]. These studies highlight the need to develop the potential of stimulation technologies using EES to transform SCI medicine. In our study, we performed electrical stimulation in a non-contact manner using implanted permanent generators, but the responses were recorded in a contact manner using a patented wired head plug.

The use of a minimally invasive rod electrode for EES instead of suturing a wired electrode to the dura mater significantly reduces surgery time, as minimally invasive placement does not require laminectomy. Intraoperative positioning and selection of optimal electrode configurations are of paramount importance [

26]. Previously, animal models have successfully demonstrated that the localization of epidural electrodes relative to the posterior roots plays a decisive role in determining the configuration and intensity of stimulation required to activate selected spinal cord circuits [

41]. Intraoperative monitoring of electrophysiological parameters during surgery allowed for precise positioning of the stimulating electrodes. EES applied at different levels of the spinal cord using specific electrode configurations allowed for selective activation of different pools of motor neurons in the spinal cord. Rostral configurations predominantly activated proximal muscles, while caudal configurations activated distal muscles in rhesus macaques (

Figure 2). In addition, the use of wider configurations for EES (1 and 8 contacts on rode electrodes) along the midline at the level of the lumbar thickening of the spinal cord probably allowed for the activation of a greater number of spinal cord segments, resulting in a greater number of muscles involved in the response and a higher amplitude of EES-evoked responses (

Figure 2). Earlier studies have shown that stimulation of these areas activates the L1–S1 spinal cord segments in humans [

18,

42]. These results indicate that the use of a rod electrode in EES in non-human primate models can successfully activate the most proximal and distal muscles of the leg, as well as activate muscles on only one side. However, in the early postoperative period, there is a risk of electrode tip migration when using a rod electrode, since with this technology only the distal part of the electrode is fixed at its exit point [

43]. Our experience shows that when two cervical electrodes are implanted using the technique we have developed—in the DREZ zone on the right and left—there has been no electrode migration in any case. The problem of electrode migration may arise for the central lumbar electrode in the first two weeks after implantation. In cases of significant electrode migration detected by electromyography or CT, the electrode can be easily repositioned (minimally invasive electrode repositioning takes no more than 30 minutes). After three weeks, a connective tissue capsule forms around the electrode, making migration impossible. Thus, from our point of view, minimally invasive installation of an 8-channel rod electrode has many more advantages than disadvantages compared to open installation. In the future, with the development of this technology at NHPs, it may be possible to create flat custom electrodes for animals, also with minimally invasive installation. Such custom electrodes have already demonstrated their advantages in patients [

44].

It remains debatable whether it is possible to completely abandon wired signal transmission at the current stage of neurotechnology development. On the one hand, it is quite obvious that wireless epidural electrical stimulation and muscle response recording are preferable in the case of non-human primates. The Courtine G. group has implemented the idea of wireless transmission of cortical signals from the motor cortex to spinal efferents via a brain-computer interface. This idea was realized in an experiment on non-human primates [

32], and was also implemented in a pilot study involving patients [

45].

These studies used a wireless system: six antennas and a receiver were used to transmit 25 broadband neural signals (bandwidth from 0.1 Hz to 7.8 kHz, sampling rate 22 kHz), customized in collaboration with Medtronic. In addition to being quite expensive and requiring constant recharging (which, in the case of primates, is almost as difficult to implement as a wired connection and usually requires sedation), its use in broadband transmission mode is accompanied by heating, which can be unsafe when transmitted to patients. Unlike wireless transmission, wired transmission does not generate heat at high flow rates and high frequencies of transmitted signals, does not require recharging, and, when used with a treadmill that secures the animal with a special collar, does not require sedation for connection. In any case, from our point of view, two transmission methods (wireless and wired) are preferable to one, so in our platform we performed wireless epidural stimulation and wired recording of myographic signals with 4 kHz sampling.

The complexity of postoperative care and ethical and regulatory issues impose significant limitations on the choice of SCI model for non-human primates [

28]. To test our experimental platform for studying the neurophysiological mechanisms of neuromodulation in spinal injury therapy, we adopted a cervical lateral hemisection model [

26]. This SCI model does not result in spontaneous recovery [

46,

47]. In our study, all animals showed no signs of motor recovery on the side of spinal cord injury for 5 weeks after spinal injury modeling.

Training and implanting anything in NHPs is technically the most difficult experimental work, requiring the most refined methodology due to the behavioral characteristics of primates. In total, 20 Rhesus macaques participated in our project for the successful completion of all procedures for developing kinematic skills, training, implantation of electrodes, generators, and head plugs, followed by data recording. The most important factor for the successful implementation of the project is the selection of compliant animals that are easy to train in quadrupedal walking on a treadmill. Our experience shows that among animals kept in enclosures, captured and kept for 3 months in individual cages with an enriched environment, no more than 25% begin to walk independently on the treadmill. Animals should be no more than 2–2.5 years old at the start of treadmill training, weigh up to 4 kg, and be kept in individual cages for at least three months (the optimal period is six months: three months in an individual cage and three months with a collar for connection to the treadmill).

As a result of this initial testing, we selected five animals out of 20 that showed stable quadrupedal walking on the treadmill. After installing the electrodes, we had to exclude 2 animals during the experiment. The first one had the initial version of the head plug installed, and the attachment to the head using a photo-curing composite proved to be insufficient. The animal broke the head plug, so all myographic electrodes had to be removed. The head plug was modified and reinforced with several self-tapping screws for fixation (

Figure 1G). In the second excluded animal, the realizing loops at the entrance to the head plug were located too superficially under the skin, as a result of which the animal was able to remove the loops despite pharmacological support with gabapentin and tritico and tear off part of the electrodes. As a result, in all subsequent animals, the exit of the electrodes under the skin to the plug was additionally reinforced with a titanium plate fixed to the skull (see Supplementary

Figure 1) and were provide X-ray verification of electrode positions after the surgery (see Supplementary

Figure 2). Another characteristic complication during the installation of the wireless generator was skin trauma and the formation of bedsores on the skin in the projection of the generator. As a result of bedsores, the generator had to be relocated in two animals. To avoid this complication, vests were made for all animals to prevent traumatic contact between the skin above the generator and the hard elements of the cage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.L., and V.P.B.; methodology - neurophysiological assessment, A.D.M., V.V.A., E.V.B.; methodology – head-plug – Zh.S.V.; surgery and neuromodulation A.R.B., M.O.Sh., T.B.A.; kinematics and animal care L.A.B., R.V.P., D.V.B.; T.B.A.; data curation, A.D.M., V.V.A; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.M., V.P.B., writing—review and editing, V.P.B., M.O.Sh, I.A.L., A.P.T.; visualization, A.D.M., V.V.A.; supervision V.P.B., I.A.L., A.P.T.; funding acquisition, V.P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.