Path planning is a fundamental technique for enabling agents to find optimal or suboptimal paths in complex environments, with widespread applications in autonomous vehicles, mobile robotics, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The core objective of path planning is to navigate an agent from a starting position to a target destination while satisfying various constraints, such as obstacle avoidance, path length minimization, energy efficiency, or flight time optimization. In recent years, advancements in artificial intelligence, computer vision, and control technologies have driven the evolution of path planning methods, spanning traditional mathematical optimization, sampling-based techniques, heuristic search algorithms, and deep reinforcement learning.

In early research on path planning, mathematical optimization methods, such as dynamic programming (DP), and graph search algorithms were widely used to determine optimal paths. Notably, in 1956, Edsger Wybe Dijkstra proposed the Dijkstra algorithm [44], which is based on weighted graphs and employs a breadth-first search (BFS) approach to guarantee the shortest path between a start and a goal node. However, this algorithm exhibits high computational complexity, particularly in high-dimensional continuous spaces, rendering it inefficient in such scenarios. To address this limitation, Peter Hart et al. introduced the A* (A-star) algorithm in 1968 [

2,

2]. The A* algorithm builds upon Dijkstra’s method by incorporating a heuristic function to guide the search process more effectively. By leveraging heuristic estimations—such as Euclidean distance or Manhattan distance—the algorithm reduces unnecessary expansions, significantly enhancing path planning efficiency. Despite its strong performance across numerous applications, A* remains computationally expensive and struggles to operate in real-time in high-dimensional environments [

2]. In the 1990s, M.H. Overmars et al. proposed the probabilistic roadmap (PRM) method [

2], a classic path planning approach particularly suited for robotic motion planning. PRM constructs a global roadmap by randomly sampling the workspace and connecting collision-free nodes to generate a feasible path. While effective in static environments, PRM suffers from limited adaptability in dynamic settings. Additionally, grid-based representation methods, such as the artificial potential field (APF) approach, have been widely applied [

2]. The APF method models attractive potential fields to guide agents toward the goal while employing repulsive potential fields to avoid obstacles. Despite its conceptual simplicity and effectiveness, APF is prone to significant drawbacks, including local minima traps and target inaccessibility issues. In recent years, with the advancement of computational power and intelligent algorithms, path planning methods have increasingly integrated metaheuristic optimization algorithms and deep learning techniques. Common metaheuristic optimization algorithms include Genetic Algorithm (GA) [

2], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [

2], Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [

9], and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [

10]. These algorithms perform global search by simulating biological behaviors and can effectively find near-optimal solutions . However, metaheuristic algorithms often struggle to balance exploration and exploitation, making them prone to local optima [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In 2023, Gang Hu et al. proposed SaCHBA-PDN to enhance the balance between exploration and exploitation in HBA [

20]. Experimental results demonstrated that SaCHBA-PDN provided more feasible and efficient paths in various obstacle environments. In 2024, Y. Gu et al. introduced Adaptive Position Updating Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO), designed to help PSO escape local optima and find higher-quality UAV paths [

21]. However, due to its iterative optimization nature, IPSO incurs high computational costs and slow convergence, limiting its applicability in real-time scenarios. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has recently emerged as a significant research direction in path planning [

22,

24]. Reinforcement learning optimizes an agent’s strategy through continuous interaction with the environment during exploration. For instance, path planning methods based on Deep Q-Network (DQN) [

23] and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [

25] have been applied in autonomous driving and UAV navigation. However, reinforcement learning methods generally require extensive training data, and their generalization ability is constrained by the training environment. Additionally, path planning methods incorporating Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) have been widely studied in robotic and UAV navigation [

26]. SLAM enables an agent to simultaneously construct a map and plan a path in an unknown environment, making it highly applicable to autonomous driving and robotic navigation. However, SLAM involves high computational complexity, particularly in large-scale three-dimensional environments, where data fusion and real-time processing remain challenging. Among the aforementioned path planning methods, the sampling-based Rapid-exploring Random Tree (RRT) has gained significant attention in recent years due to its efficiency and adaptability [

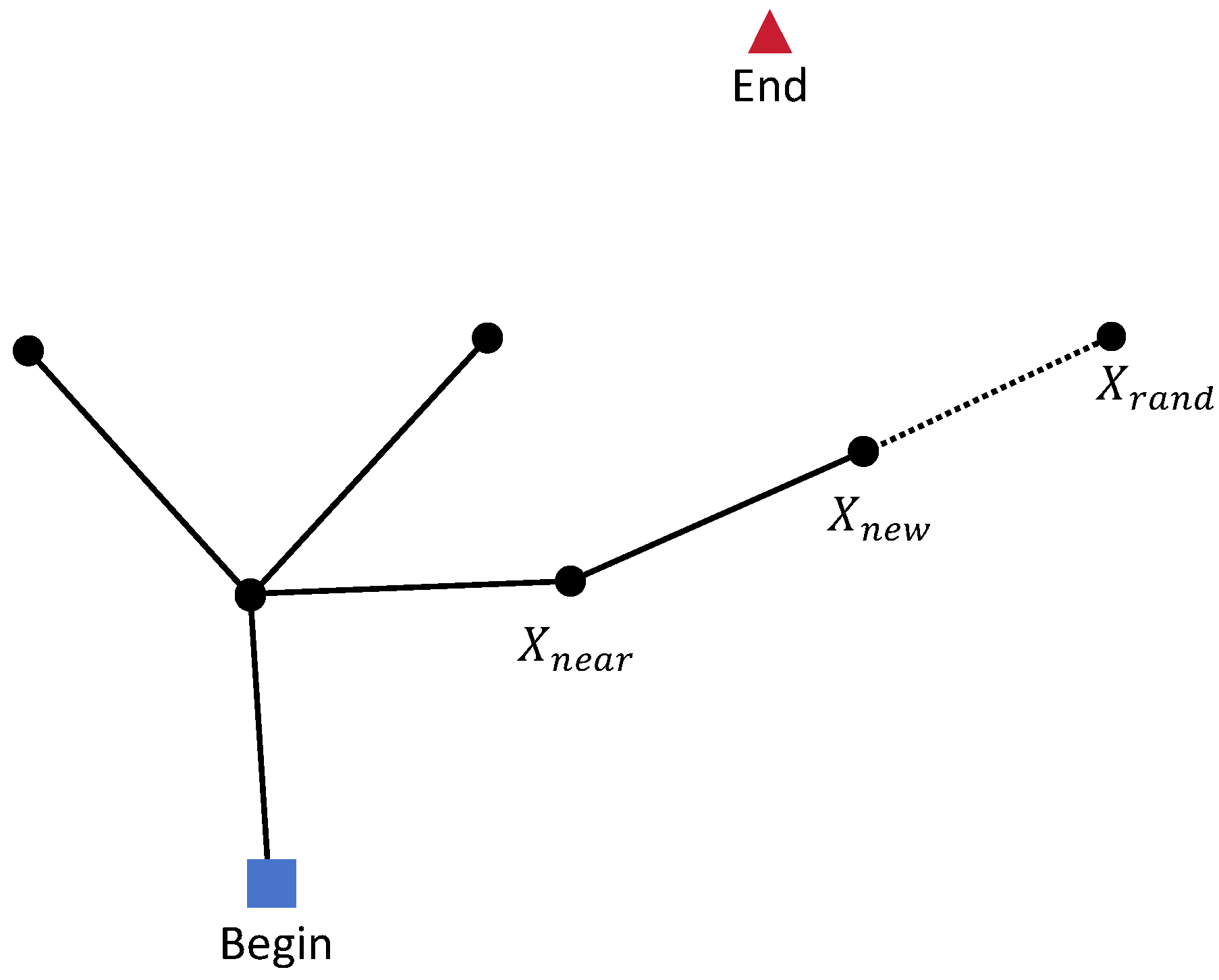

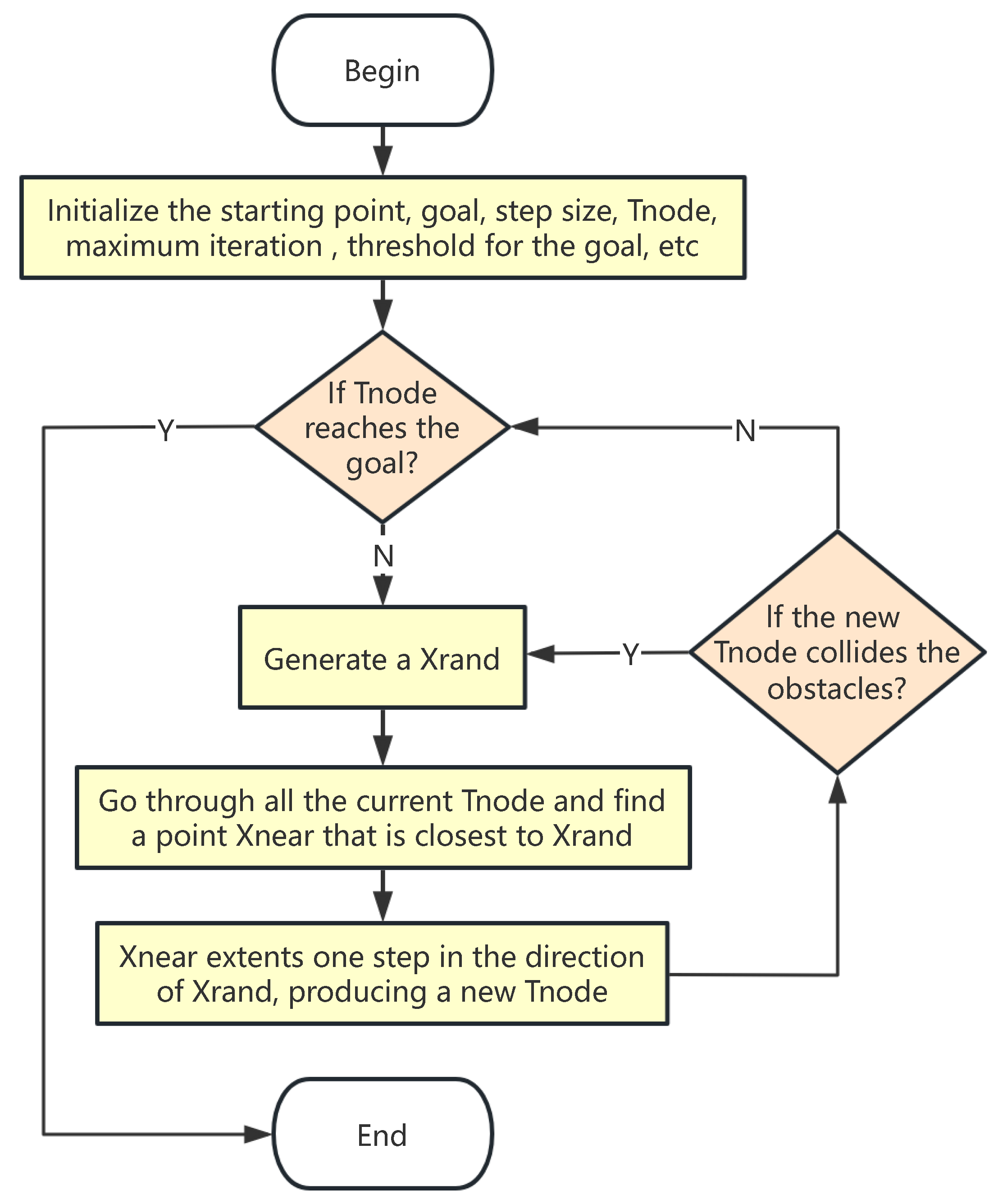

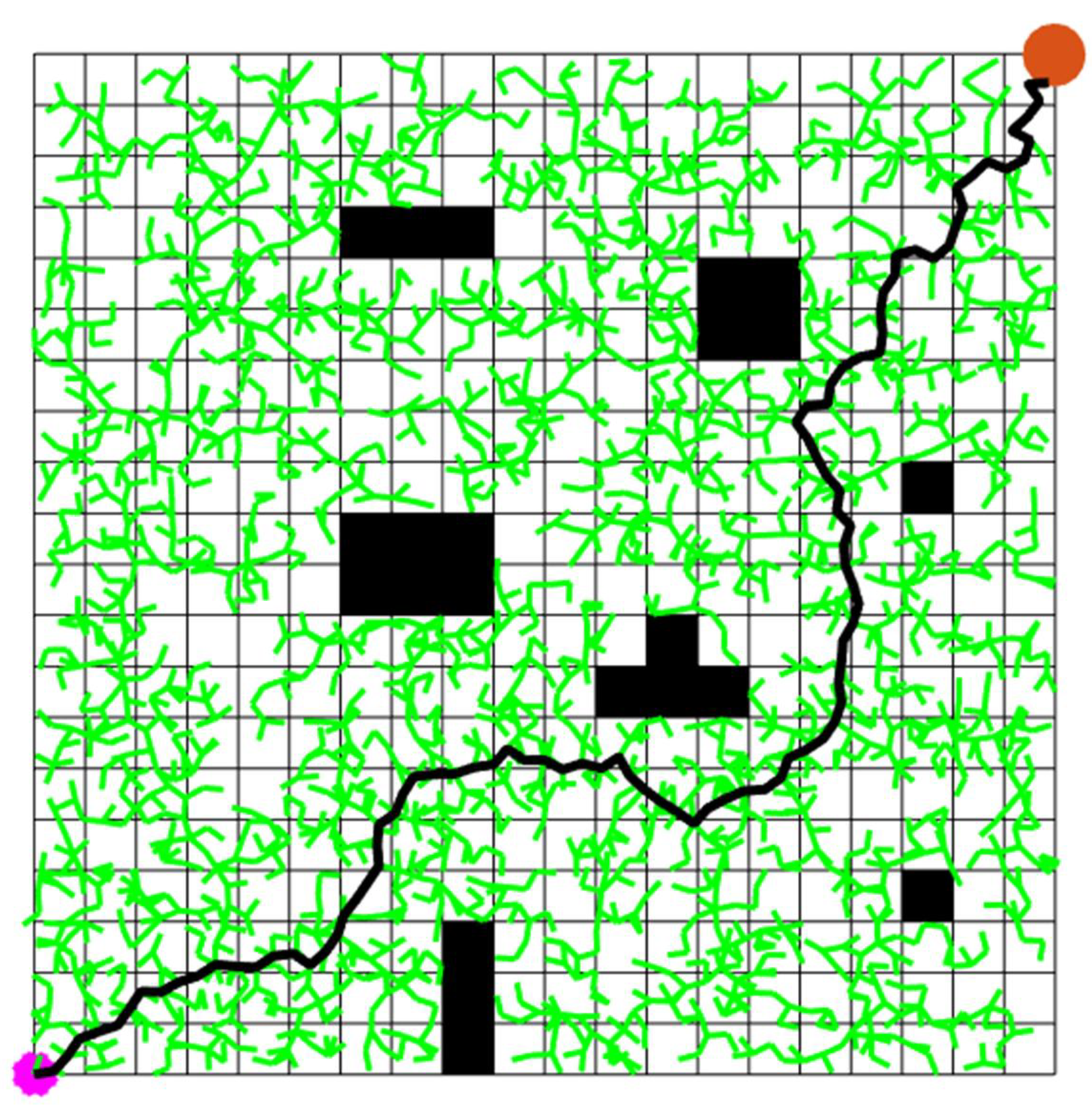

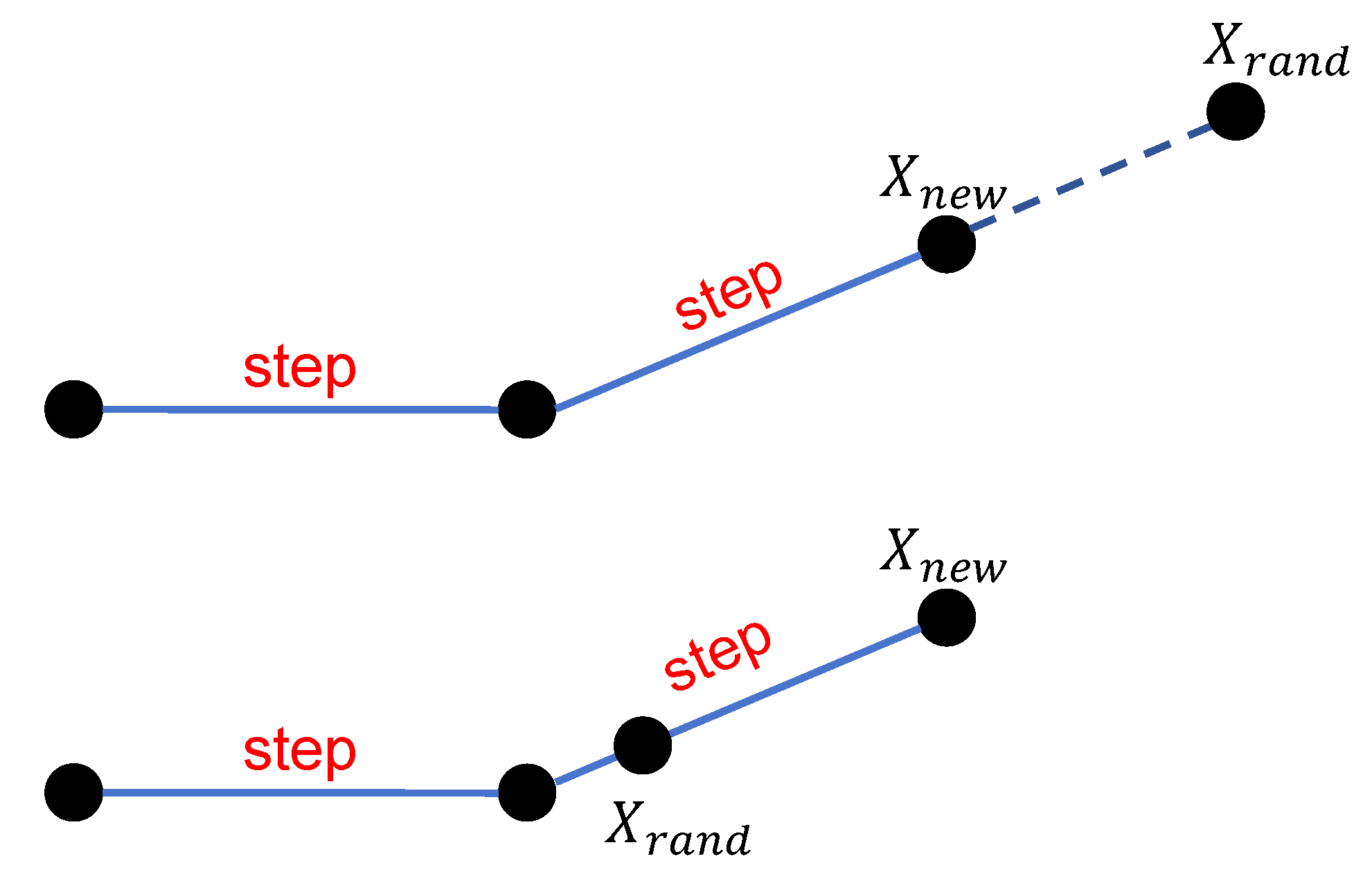

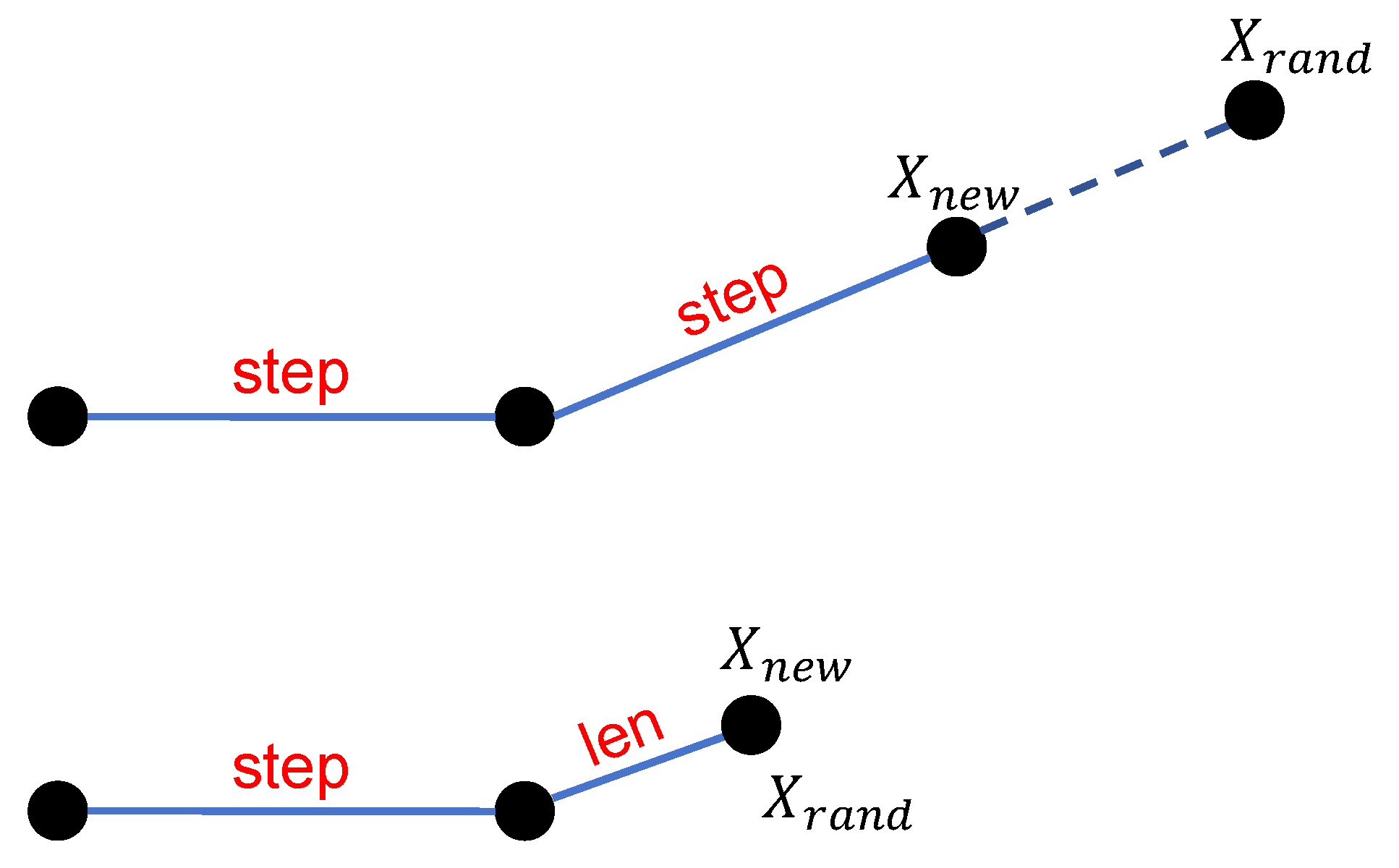

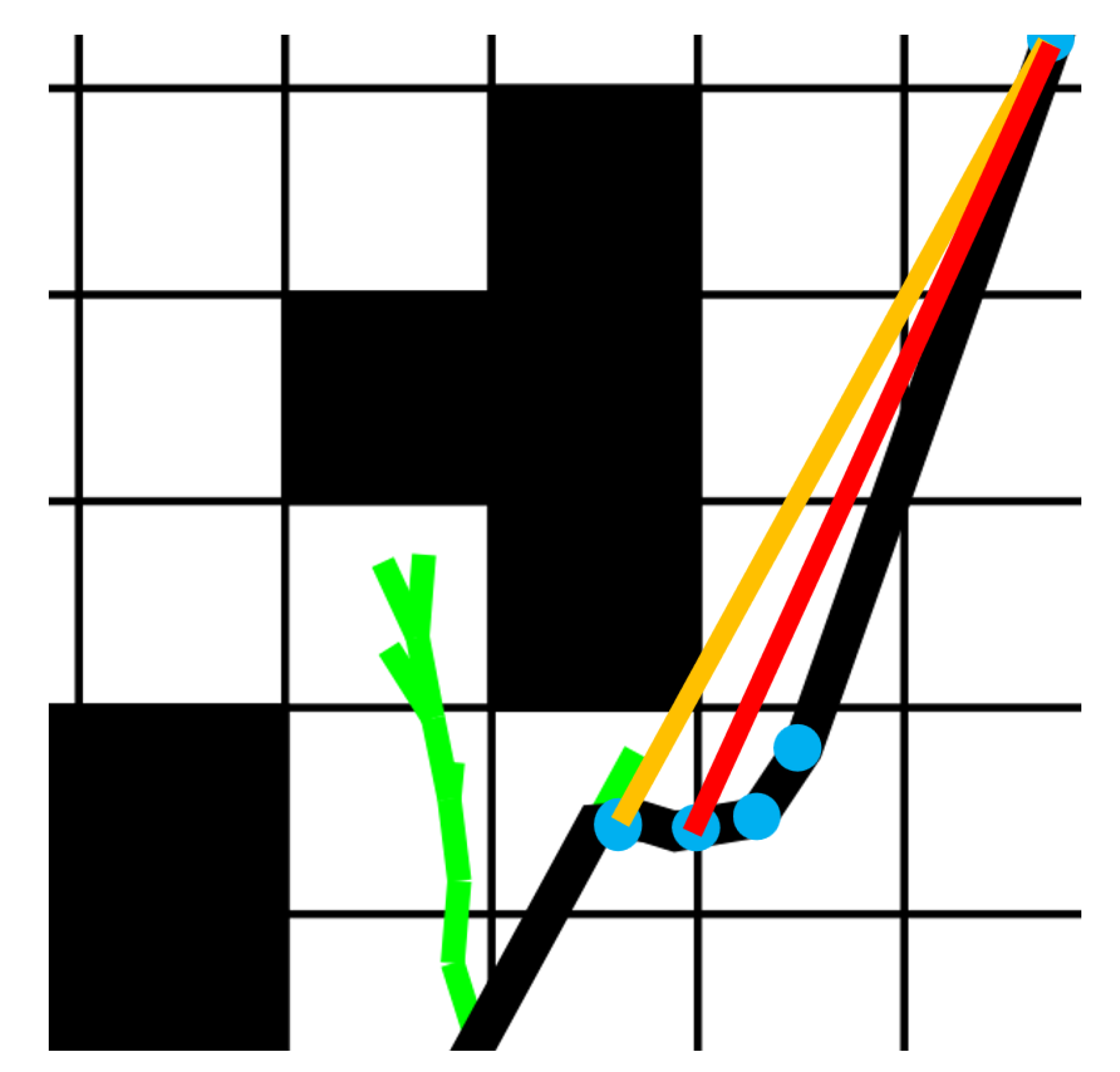

27]. RRT operates by randomly sampling points in the search space and incrementally constructing an expanding tree, enabling rapid coverage of the feasible space. This approach is particularly suitable for path planning in high-dimensional and complex environments. However, traditional RRT algorithms still face several challenges, such as unstable path quality, search efficiency heavily influenced by randomness, and susceptibility to local optima in complex environments. To enhance the performance of RRT in UAV urban path planning, researchers have proposed various improvement strategies. For instance, in 2000, Kuffner J. J. et al. introduced Bidirectional RRT (RRT-Connect), which simultaneously expands tree structures from both the start and goal points, significantly accelerating search convergence [

28]. RRT*, an optimized variant of RRT, incorporates a path rewiring mechanism to improve path quality, making it closer to the optimal solution [

29]. In 2015, Klemm S. et al. combined the concepts of RRT-Connect and RRT* to propose RRT*-Connect, aiming to provide robust path planning for autonomous robots and self-driving vehicles [

30]. In 2022, B. Wang et al. integrated Quick-RRT* with RRT-Connect to develop CAF-RRT*, designed to ensure smoothness and safety in 2D robot path planning [

31]. In 2024, Joaquim Ortiz-Haro et al. introduced iDb-RRT to address two-value boundary problems (which are computationally expensive) and to enhance the propagation of random control inputs (which are often uninformative). Experimental results demonstrated that iDb-RRT could find solutions up to ten times faster than other methods [

32]. In 2025, Hu W. et al. proposed HA-RRT, incorporating adaptive tuning strategies and a dynamic factor to improve the adaptability and convergence of RRT [

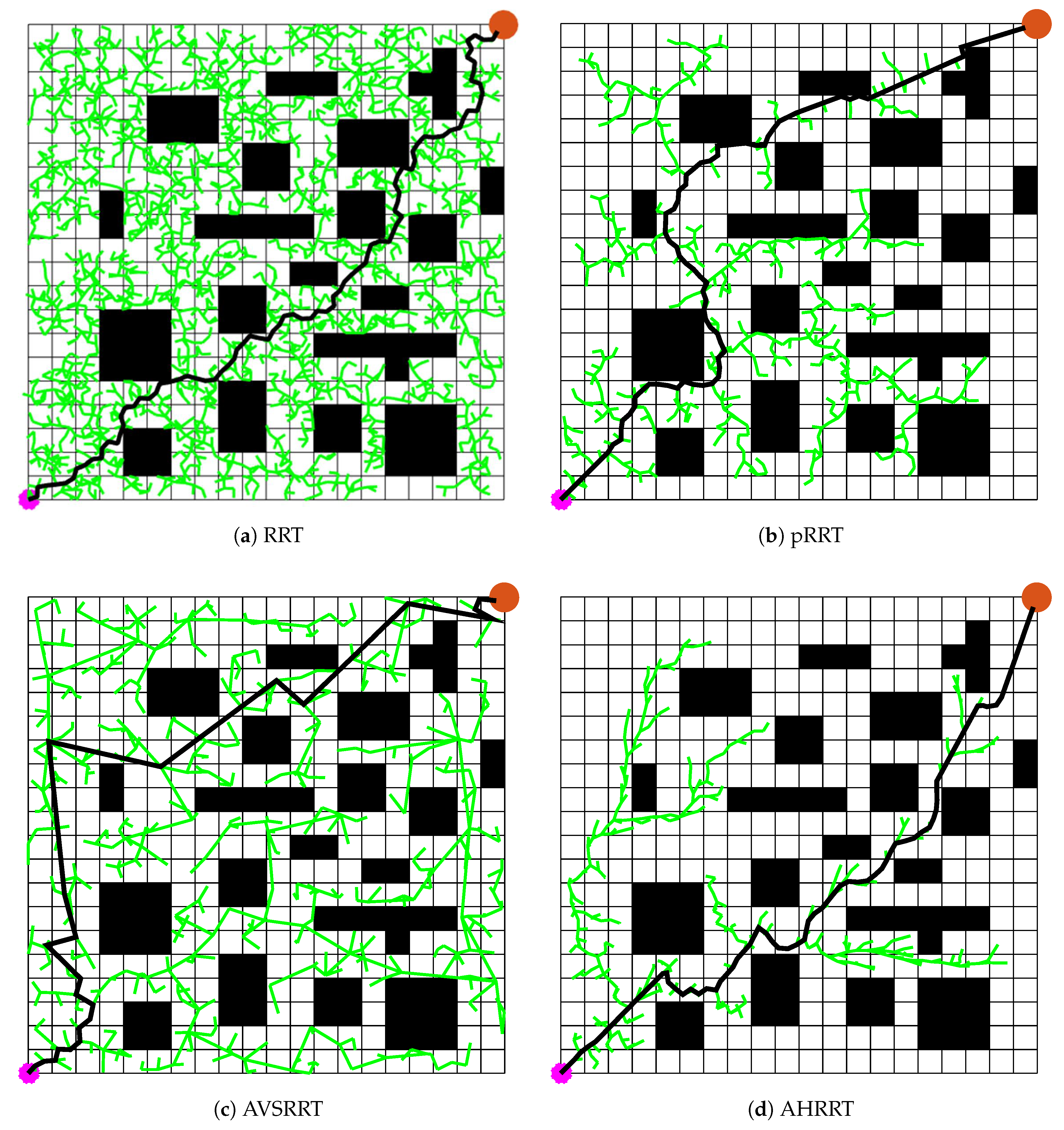

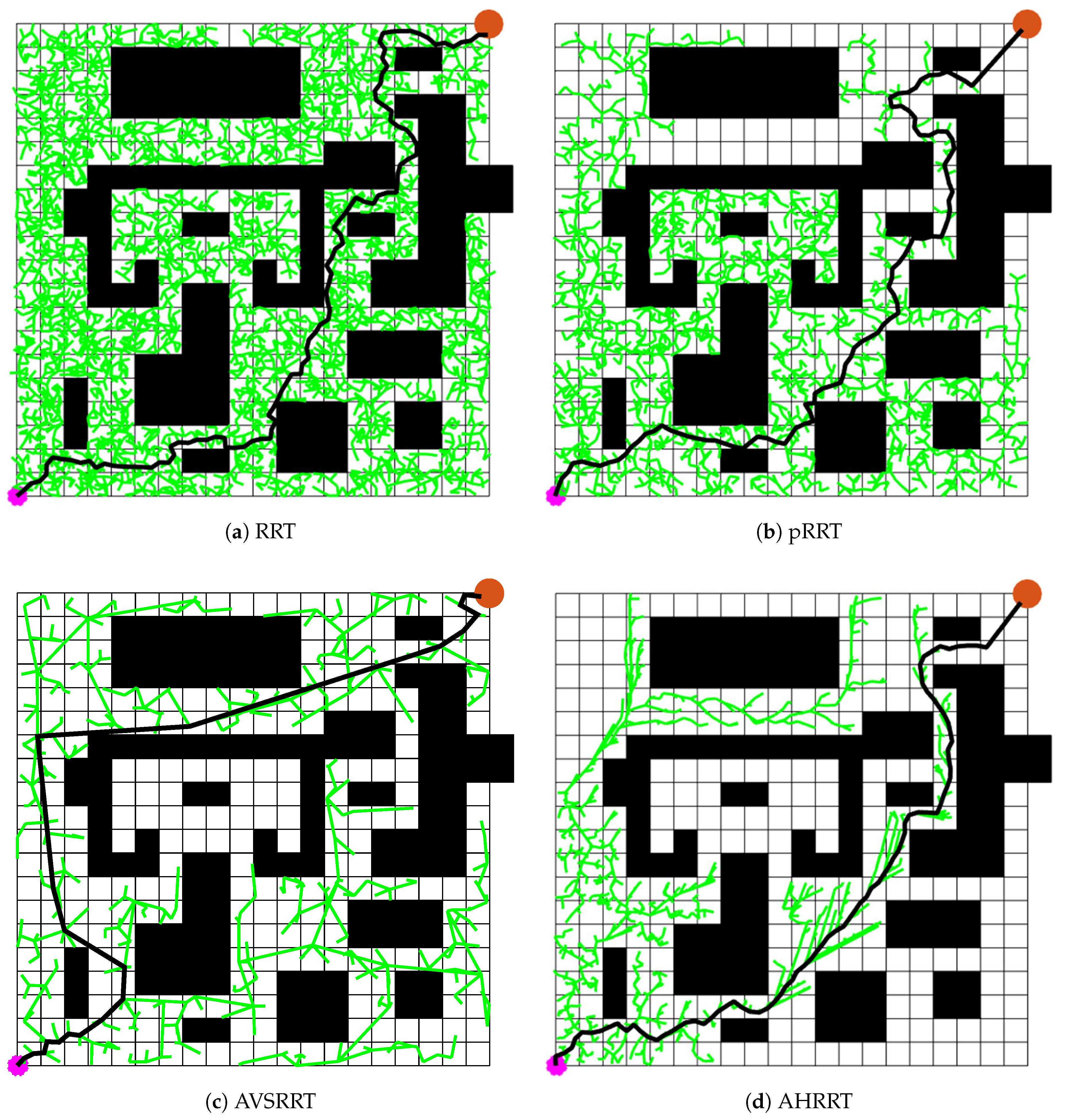

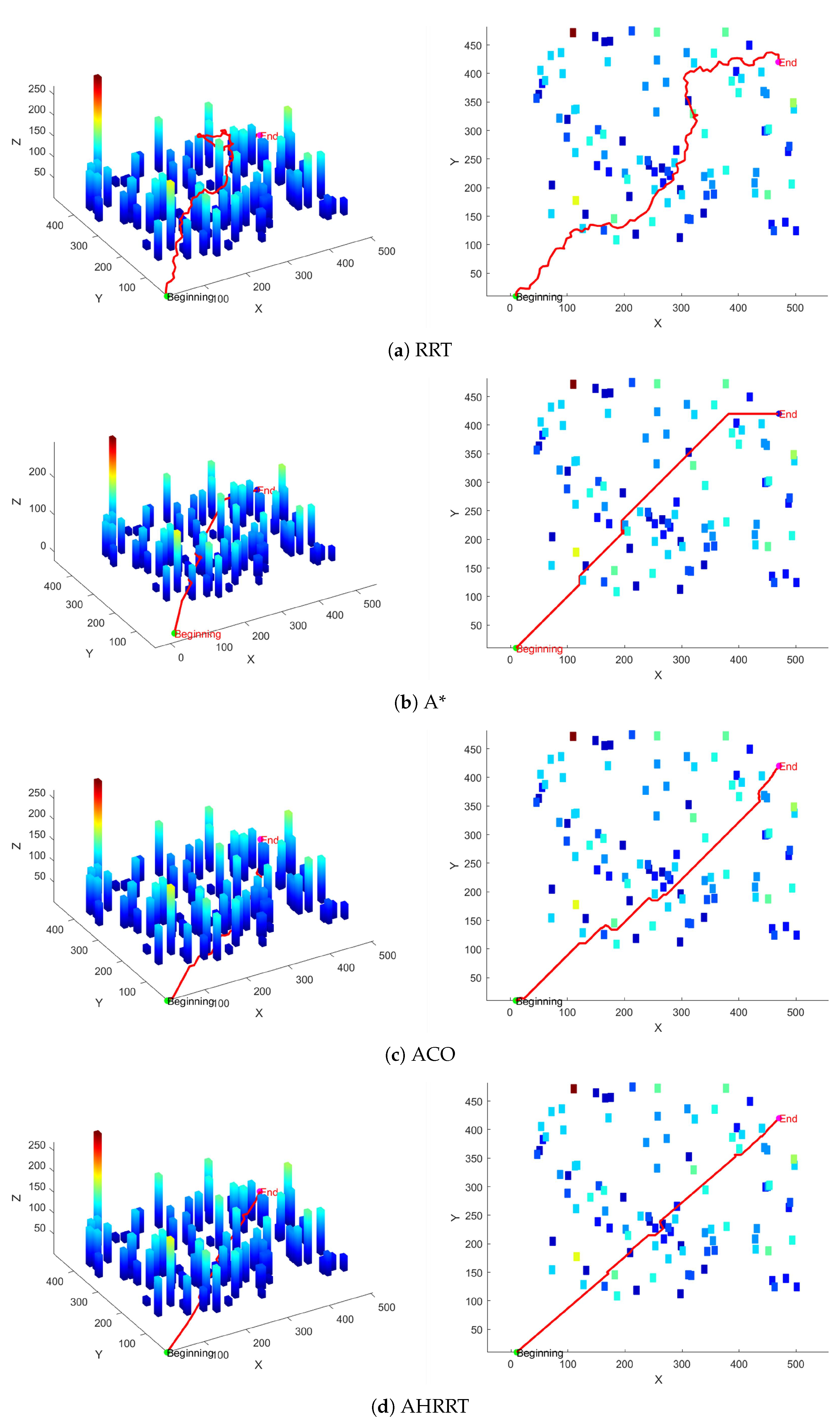

33]. However, these methods are often effective in 2D environments, while researchers have largely overlooked the feasibility of applying improved RRT variants to 3D maps. This paper proposed an adaptive RRT algorithm with heuristic search (AHRRT) that integrates heuristic search strategies to enhance the efficiency and robustness of path planning. AHRRT leverages environmental information during the sampling process to adjust the sampling strategy, enabling more efficient path searches in 3D maps. Furthermore, the algorithm incorporates an adaptive adjustment mechanism, allowing the exploration process to dynamically optimize itself based on environmental variations.