Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

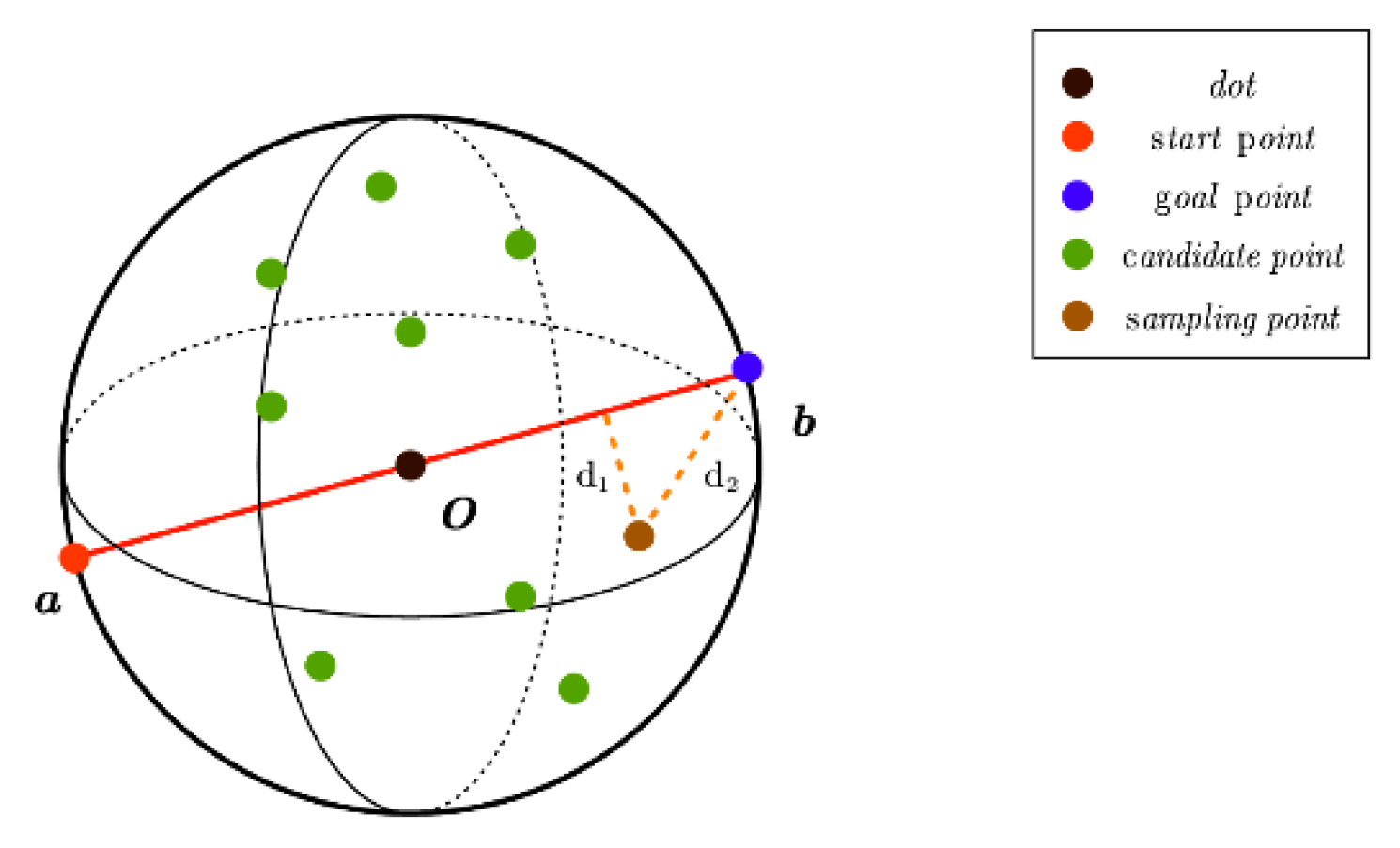

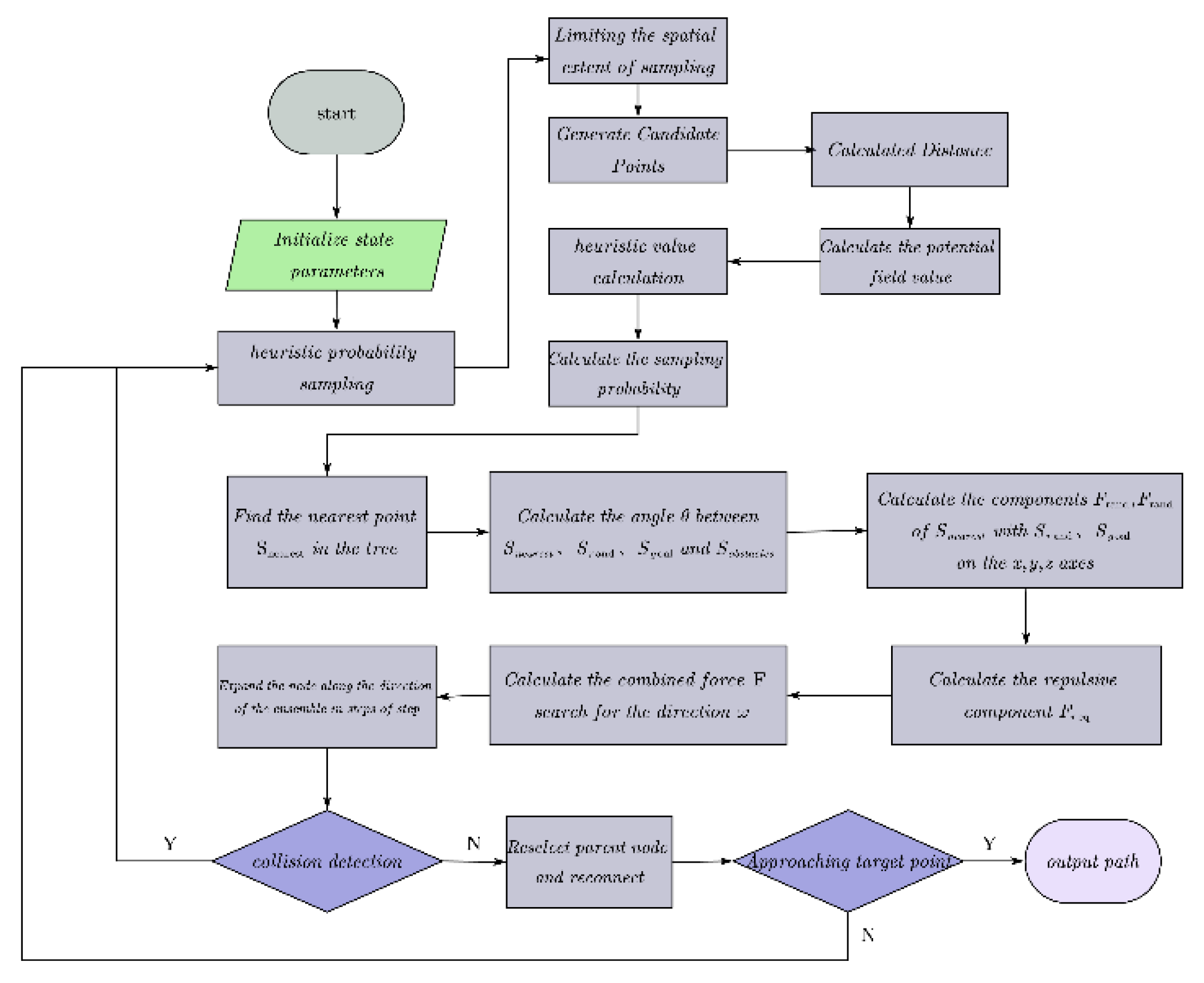

- Candidate Point Probability Calculation in the RRT* [21]:In three-dimensional Cartesian space, the line segment connecting the starting and ending points represents the shortest path. Define a spherical region based on the shortest path as the diameter. All candidate points will be sampled within this sphere. Calculate the distance from the candidate point to the nearest point on the shortest path and direct it towards the target point. By constructing a heuristic function, the weight of each candidate point is evaluated. Based on the weight values, the sampling probability of each candidate point is calculated to guide the algorithm in exploring the search space more efficiently;

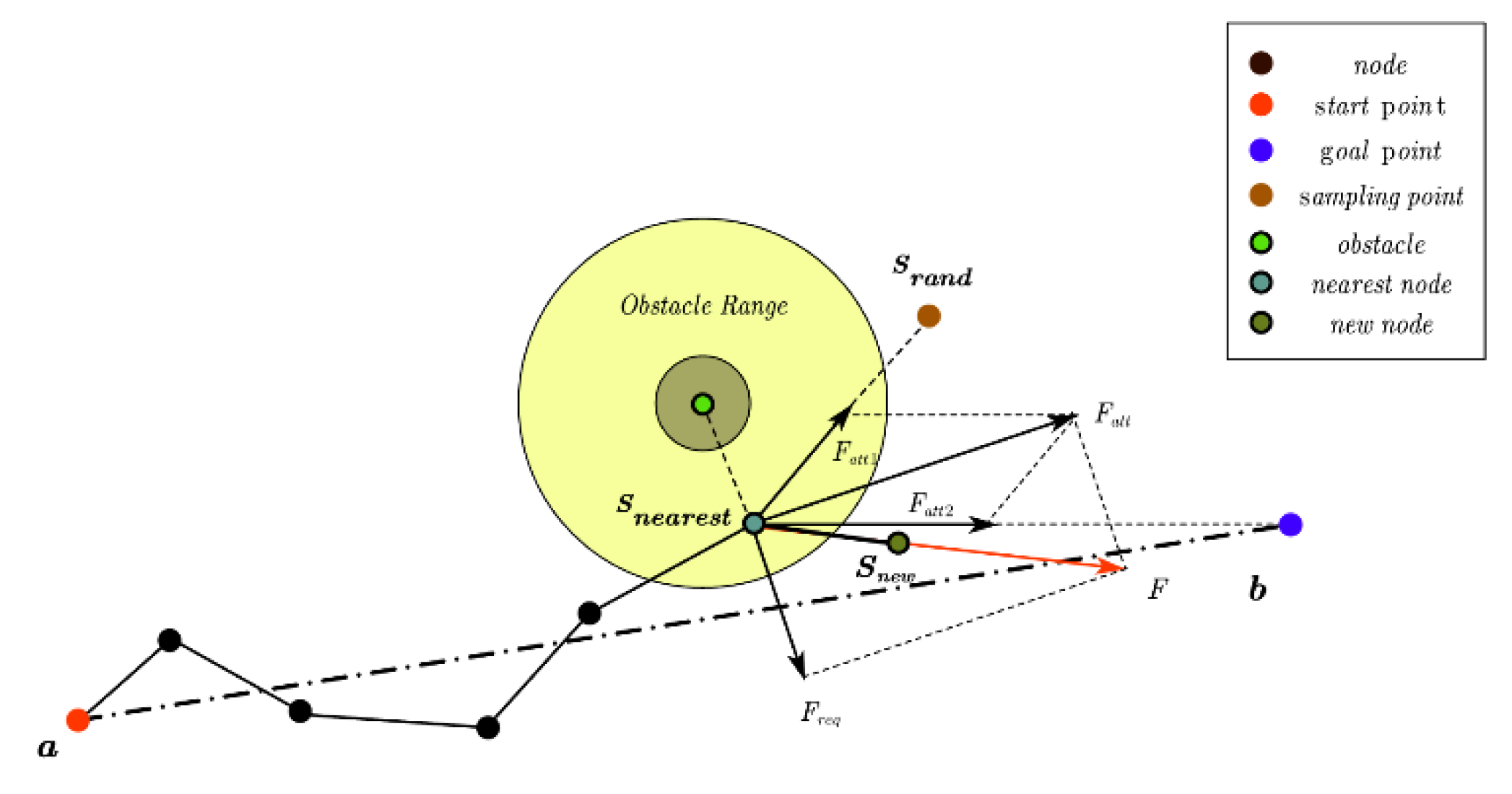

- Obstacle Avoidance Strategy Based on the APF[22]:The search time is significantly increased because the sampled nodes may be located in areas with dense obstacles. APF is introduced to guide the sampling point to avoid obstacles and move towards the target point by constructing a gravitational field and a repulsive field. This method enhances the density of sampling points, alters the direction of node expansion, and addresses the challenge of pathfinding in complex environments;

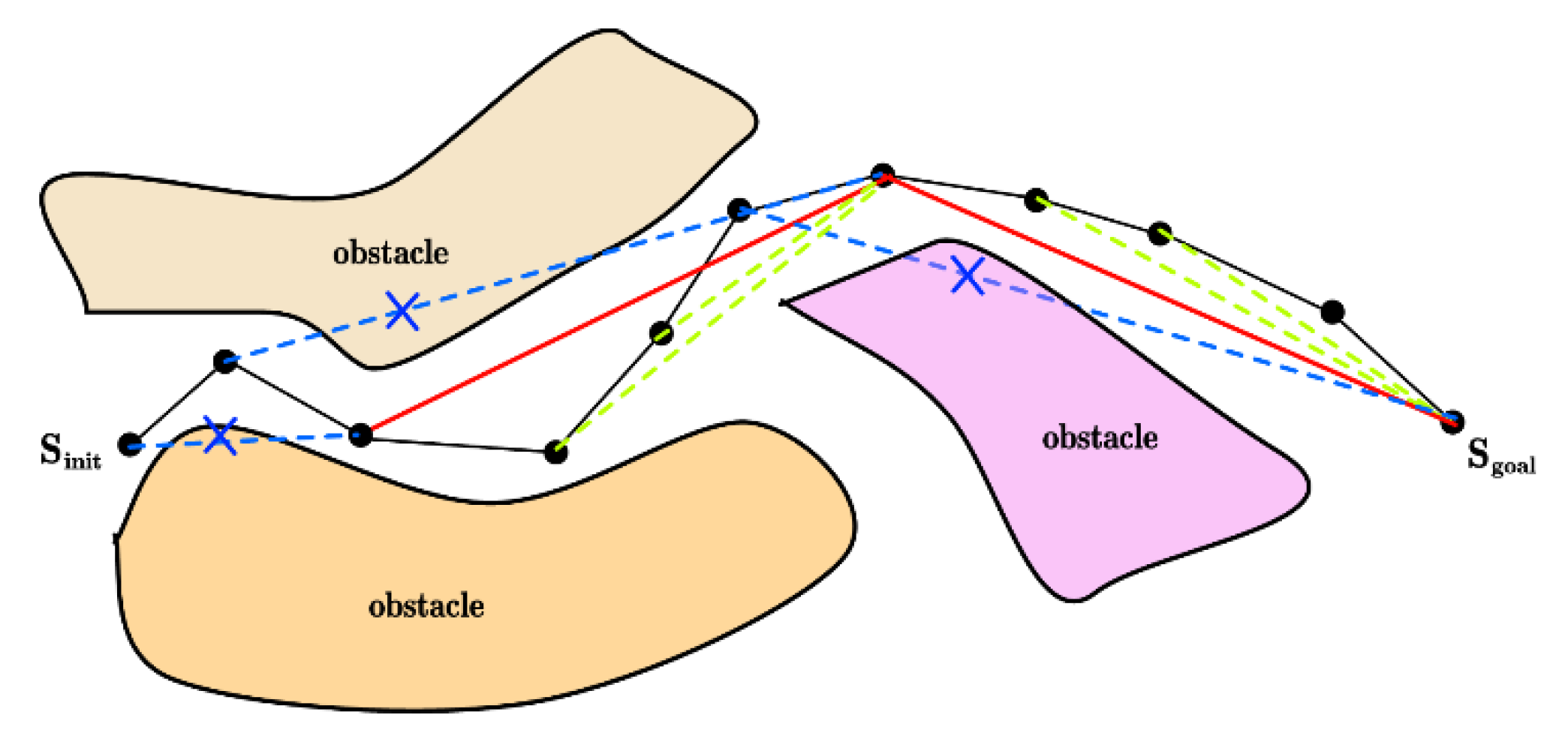

- Optimization of Paths Based on Trigonometric Inequalities[23]:The triangle inequality principle is employed to optimize each node along the generated path. The evaluation function is designed to re-evaluate and select the parent node for each node, eliminate redundant nodes along the path, simplify the path, and enhance both the efficiency and clarity of the final path.

2. Improved RRT* with Heuristic Probability Sampling and APF

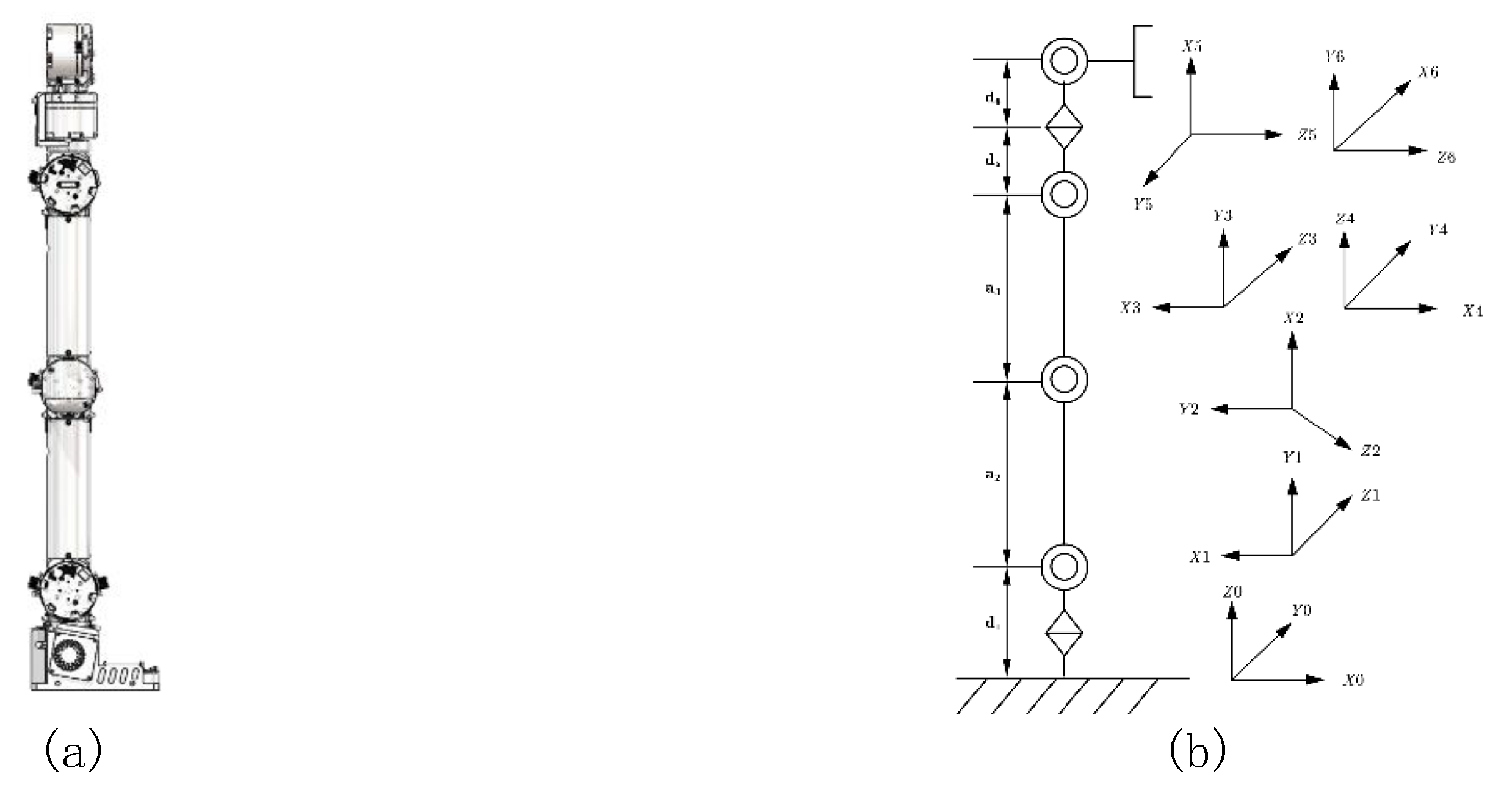

2.1. Kinematic Modeling and Solution of Robotic Arms

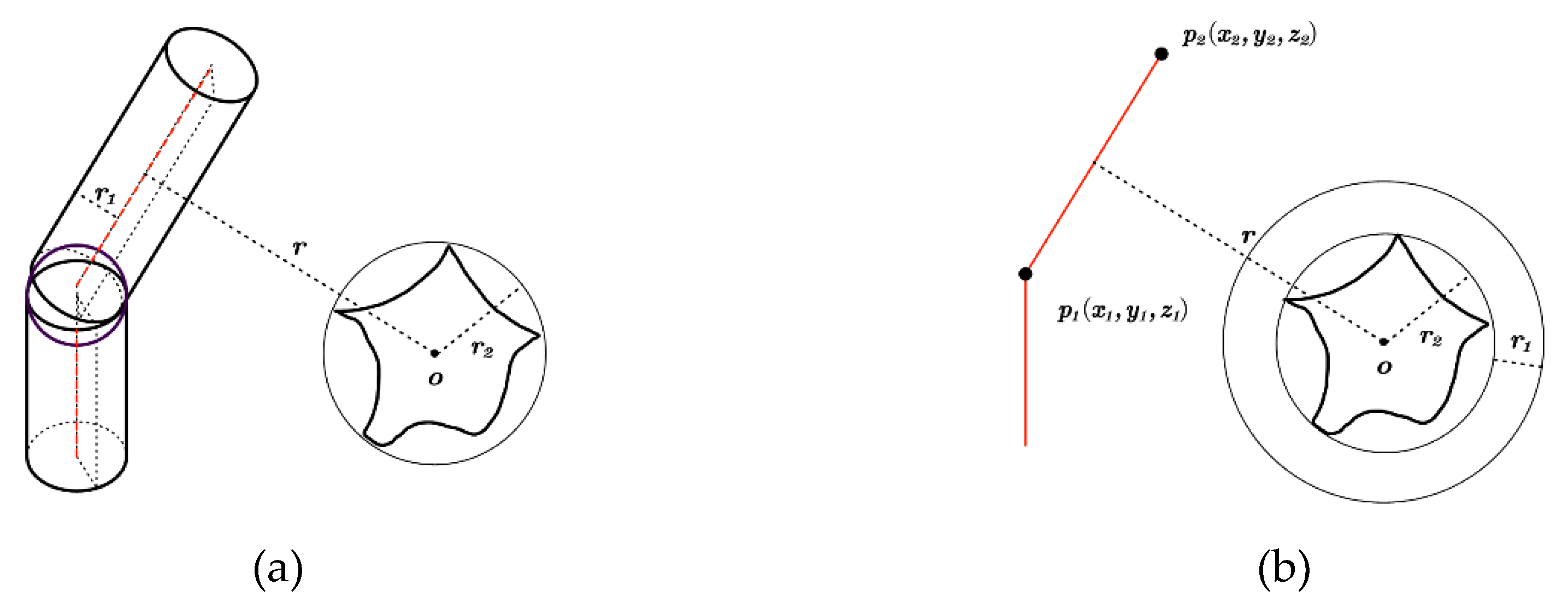

2.2. Obstacle Collision Detection

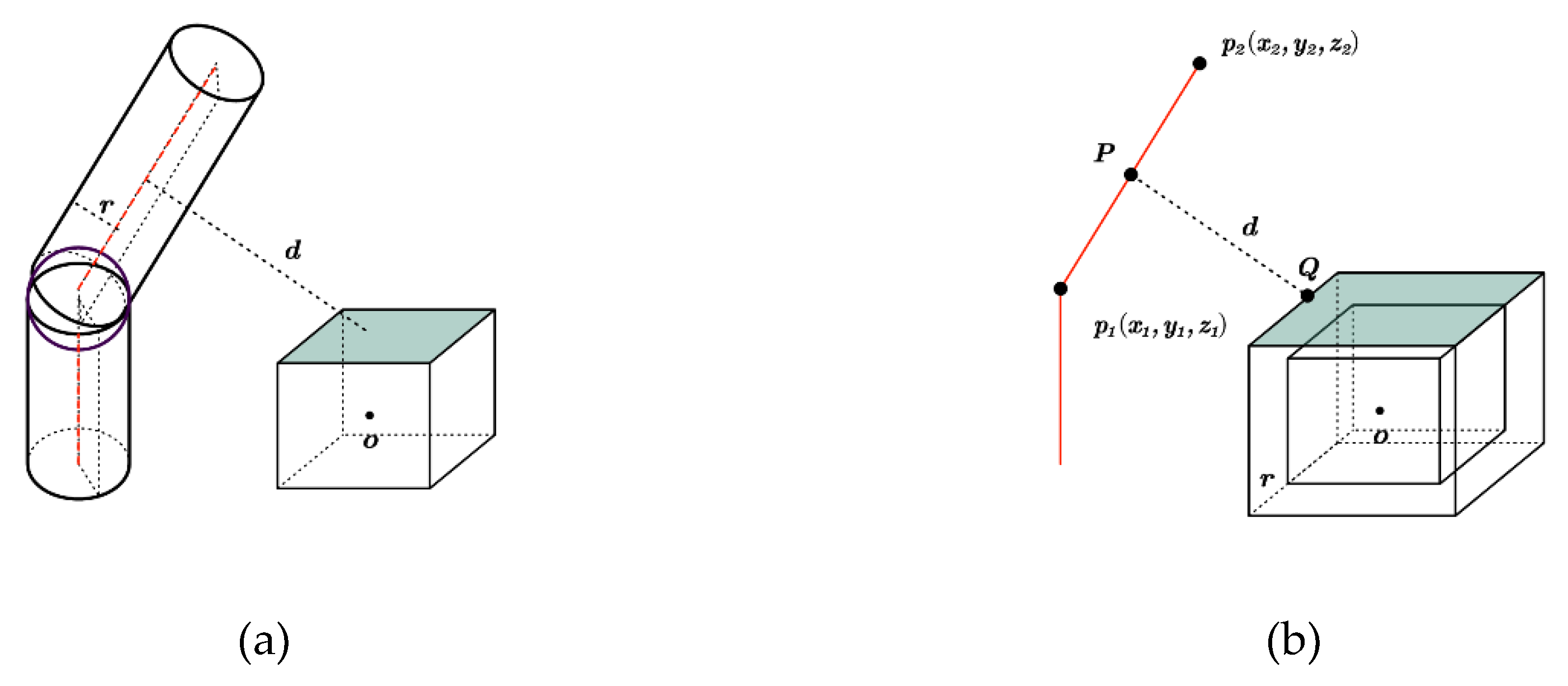

2.2.1. Collision detection of irregular obstacles

2.2.2. Collision Detection of Regular Obstacles

2.3. Improved RRT* Based on Heuristic Probabilistic Sampling

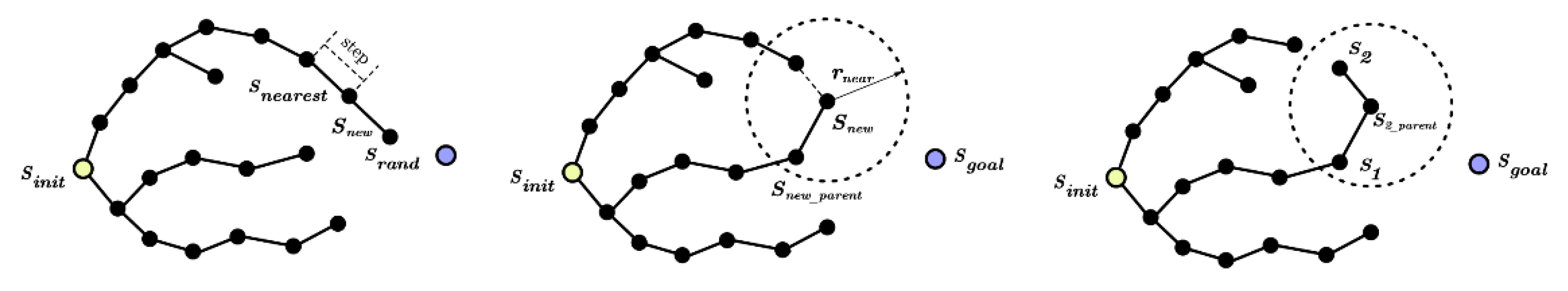

2.3.1. Basics of the RRT*

2.3.2. Improved RRT* Based on Heuristic Probabilistic Sampling

- Initialization phase;

- 2.

- Candidate point generation;

- 3.

- Heuristic function design;

- 4.

- Sampling and path selection

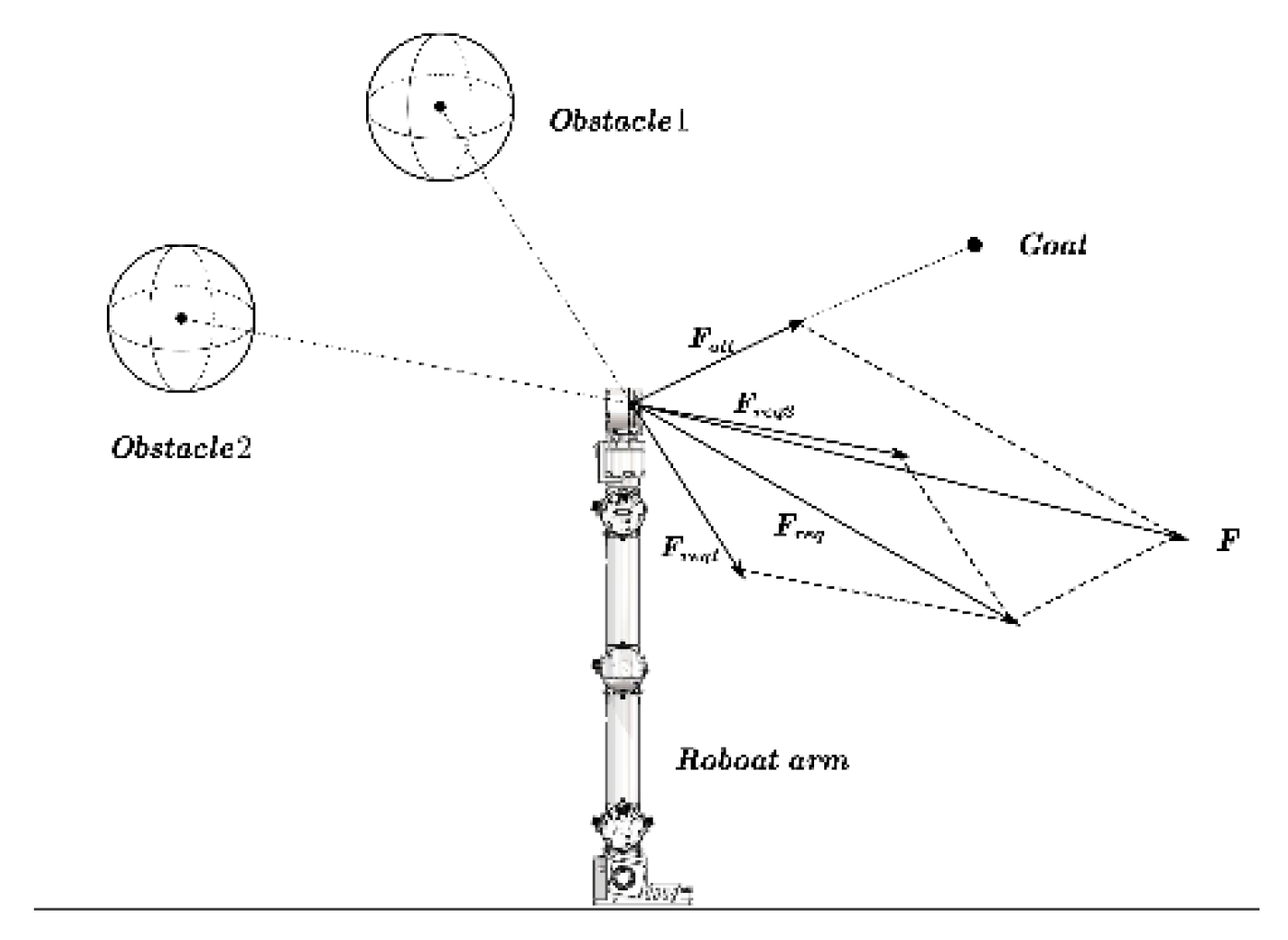

2.4. Improved HP-RRT* incorporating the APF

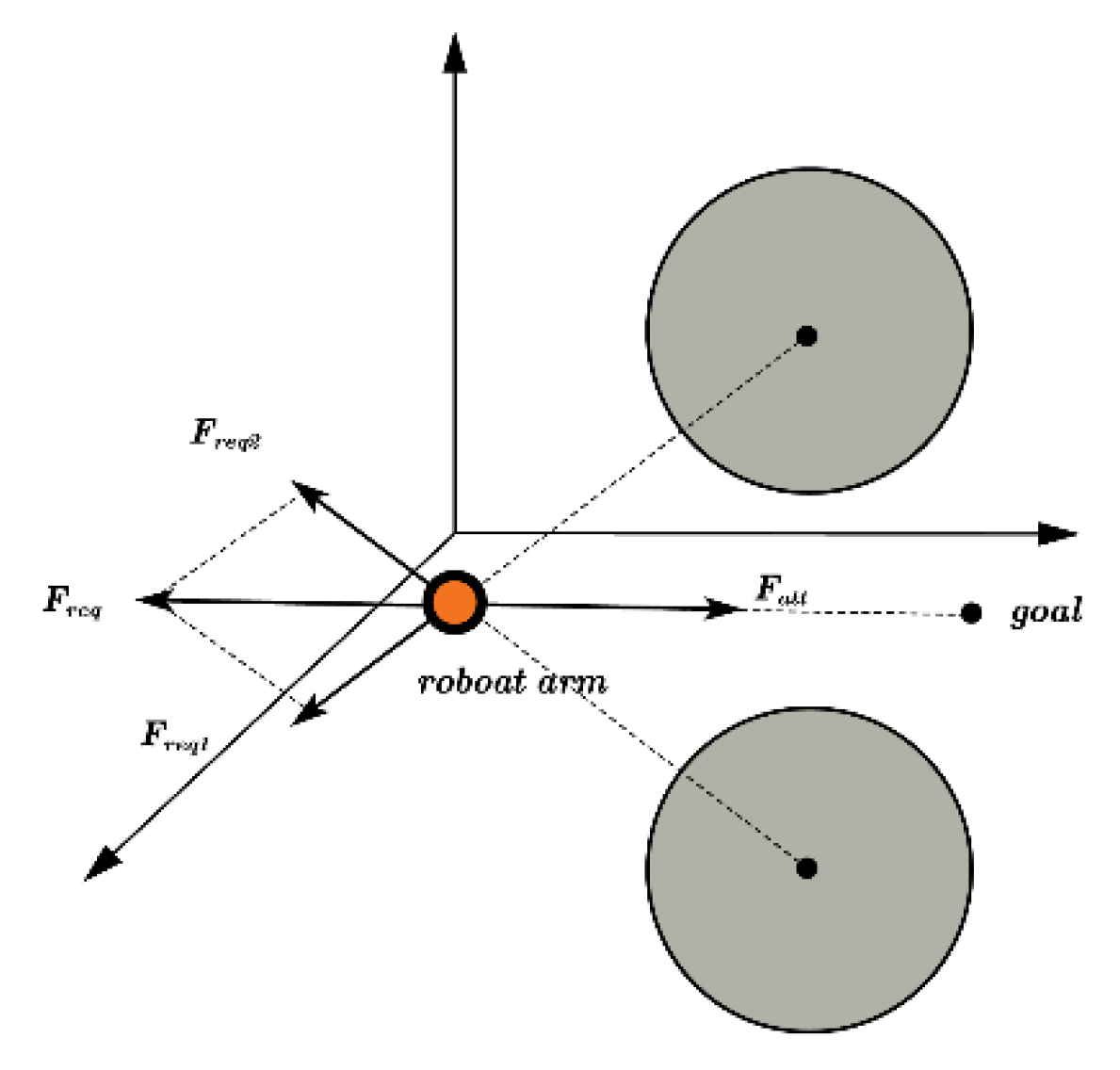

2.4.1. Traditional APF

2.4.2. Improved APF

2.4.3. HP-RRT* Incorporating APF

2.5. Path Optimization Based on Trigonometric Inequalities

3. Experiments and Analysis

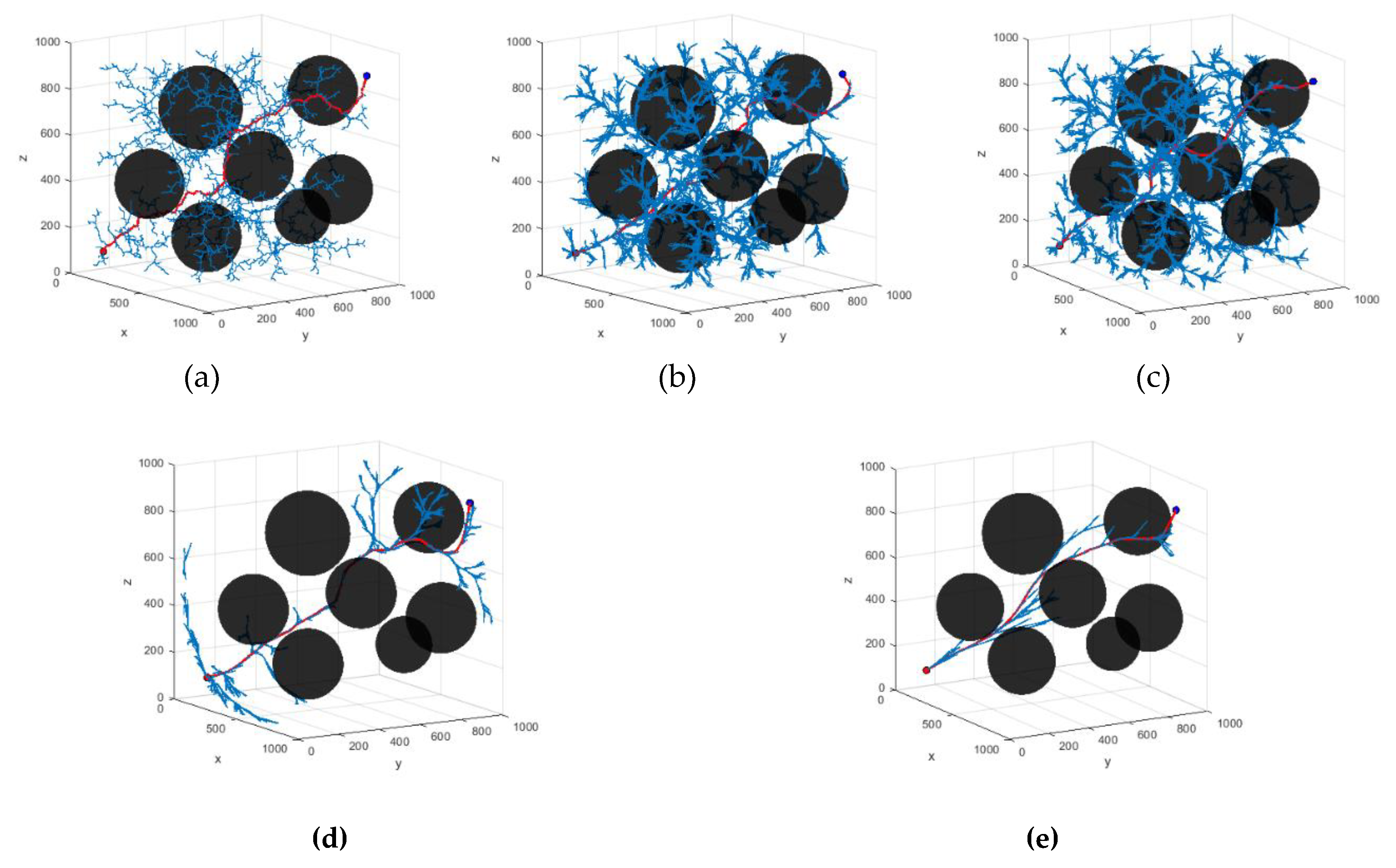

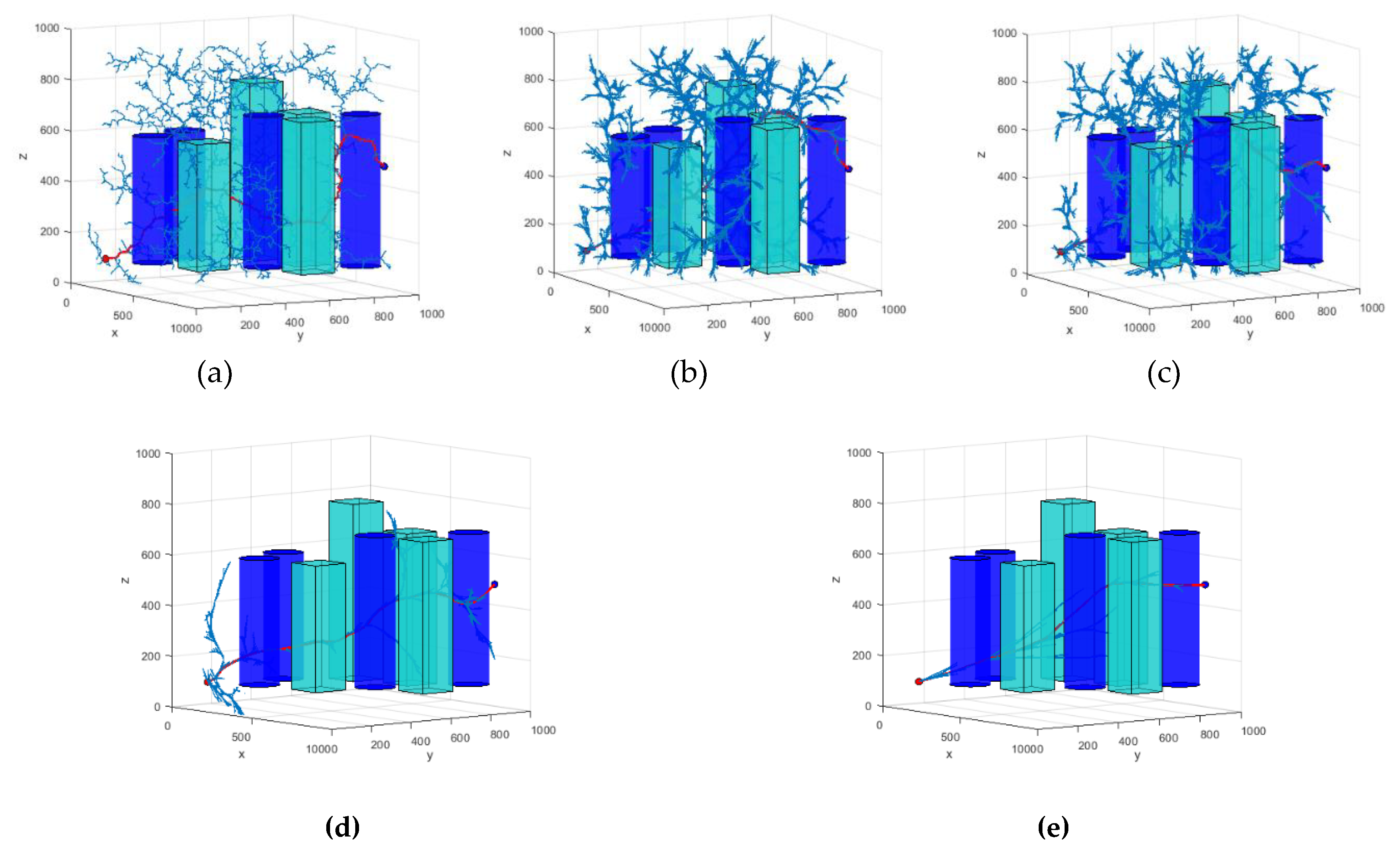

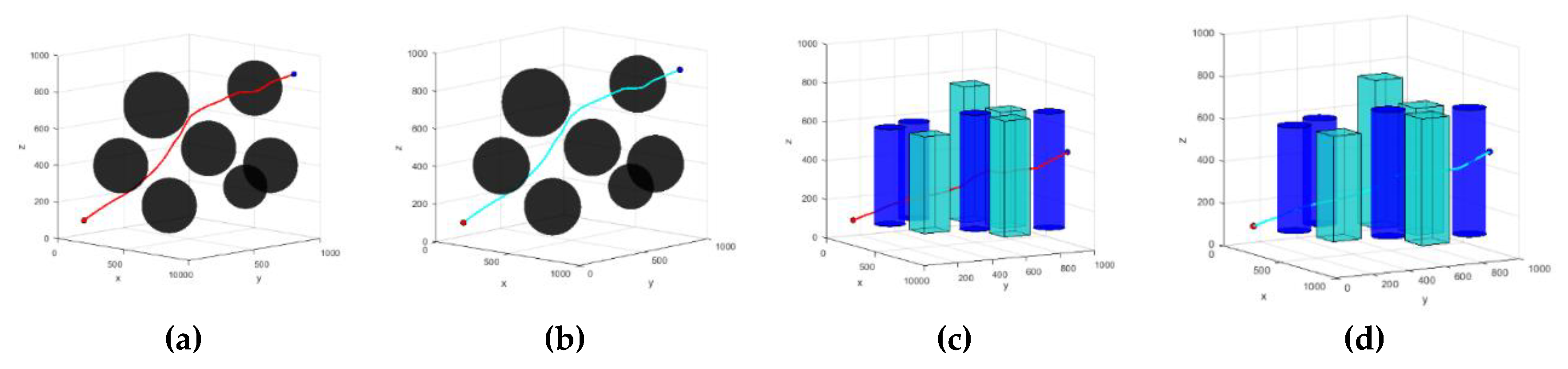

3.1. Simulation Experiment Analysis

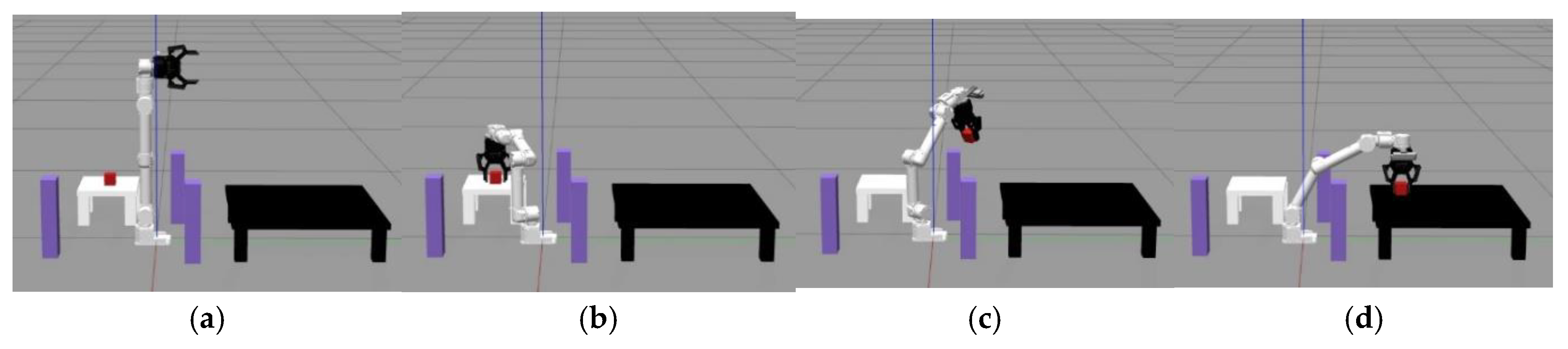

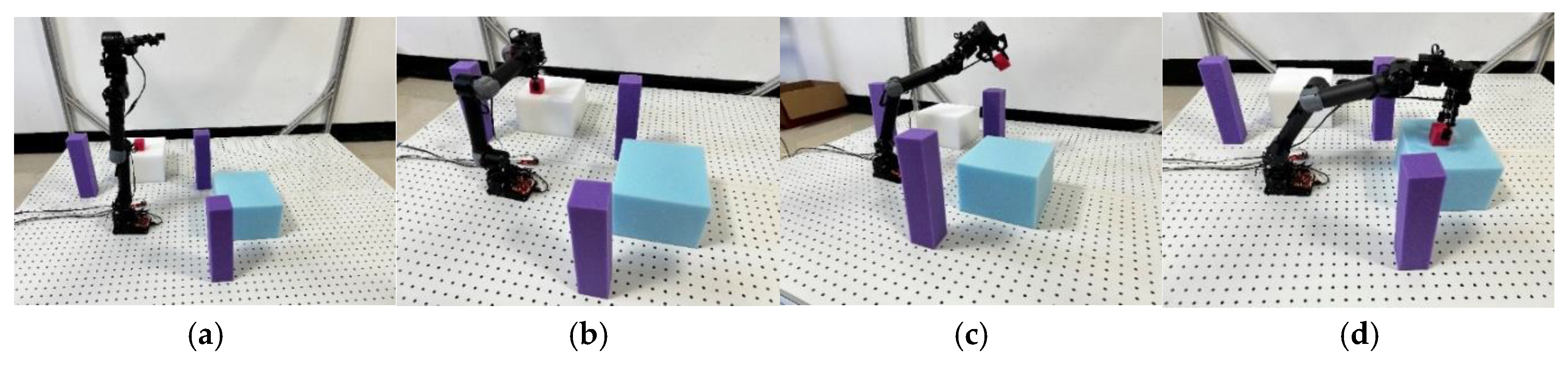

3.2. Physical Experiment Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Husainy, A.; Mangave, S.; Patil, N. J. A. R. o. M. E., A Review on Robotics and Automation in the 21st Century: Shaping the Future of Manufacturing, Healthcare, and Service Sectors. 2023, 12 (2), 41-45. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; He, Z.; Song, C.; Sun, C. J. J. o. S. E.; Electronics, A review of mobile robot motion planning methods: from classical motion planning workflows to reinforcement learning-based architectures. 2023, 34 (2), 439-459. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. I.; Lee, B.; Kim, K. In Path planning algorithm using the particle swarm optimization and the improved Dijkstra algorithm, 2008 IEEE Pacific-Asia Workshop on Computational Intelligence and Industrial Application, IEEE: 2008; pp 1002-1004.

- Han, C.; Li, B. In Mobile robot path planning based on improved A* algorithm, 2023 IEEE 11th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC), IEEE: 2023; pp 672-676.

- Li, B.; Chen, B. J. I. C. J. o. A. S., An adaptive rapidly-exploring random tree. 2021, 9 (2), 283-294. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Bu, S.; Yang, J. J. S., Smart vehicle path planning based on modified PRM algorithm. 2022, 22 (17), 6581. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, W.; Gao, Y.; Wang, D.; Fan, Z. J. E. s. w. a., PQ-RRT*: An improved path planning algorithm for mobile robots. 2020, 152, 113425. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X. J. R. P. o. E., Overview of Path Planning Algorithms. 2024, 18 (7), 76-89. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yap, H. J.; Khairuddin, A. S. M. J. J. o. S., Review on Motion Planning of Robotic Manipulator in Dynamic Environments. 2024, 2024 (1), 5969512. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, P. J. E. S. w. A., Path planning techniques for mobile robots: Review and prospect. 2023, 227, 120254. [CrossRef]

- Sotirchos, G.; Ajanovic, Z. J. a. p. a., Search-based versus Sampling-based Robot Motion Planning: A Comparative Study. 2024.

- Karaman, S.; Frazzoli, E. J. T. I. J. o. R. R., Sampling-based algorithms for optimal motion planning. 2011, 30, 846 - 894.

- Qi, J.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, C.; Du, X.; Du, F.; Ren, A. J. C.; Systems, I., Path planning and collision avoidance based on the RRT* FN framework for a robotic manipulator in various scenarios. 2023, 9 (6), 7475-7494. [CrossRef]

- LaValle, S. M.; Kuffner, J. J. J. T. I. J. o. R. R., Randomized Kinodynamic Planning. 1999, 20, 378 - 400. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, N. J. S. C. I.; Systems, Airport AGV path optimization model based on ant colony algorithm to optimize Dijkstra algorithm in urban systems. 2022, 35, 100716. [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, R.; Bai, H. J. C.; systems, i., Path planning of a manipulator based on an improved P_RRT* algorithm. 2022, 8 (3), 2227-2245. [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Ding, Z.; Fu, Z.; Li, M.; Ji, B. J. S. R., Efficient path planning for autonomous vehicles based on RRT* with variable probability strategy and artificial potential field approach. 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, T.; Li, B.; Meng, M. Q.-H. J. I. T. o. I. V., GMR-RRT*: Sampling-based path planning using gaussian mixture regression. 2022, 7 (3), 690-700. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chi, W.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Meng, M. Q.-H. J. I. T. o. A. S.; Engineering, Neural RRT*: Learning-based optimal path planning. 2020, 17 (4), 1748-1758. [CrossRef]

- Chai, Q.; Wang, Y. J. A. S., RJ-RRT: improved RRT for path planning in narrow passages. 2022, 12 (23), 12033. [CrossRef]

- Luders, B.; Kothari, M.; How, J. In Chance constrained RRT for probabilistic robustness to environmental uncertainty, AIAA guidance, navigation, and control conference, 2010; p 8160.

- Zhang, W.; Xu, G.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y. J. J. o. F. R., An obstacle avoidance strategy for complex obstacles based on artificial potential field method. 2023, 40 (5), 1231-1244. [CrossRef]

- Mall, K.; Grant, M. J.; Taheri, E. J. J. o. S.; Rockets, Uniform trigonometrization method for optimal control problems with control and state constraints. 2020, 57 (5), 995-1007. [CrossRef]

- Stilman, M. J. I. T. o. R., Global manipulation planning in robot joint space with task constraints. 2010, 26 (3), 576-584. [CrossRef]

- Stilman, M. In Task constrained motion planning in robot joint space, 2007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, IEEE: 2007; pp 3074-3081.

- Lee, J.-W.; Park, G.-T.; Shin, J.-S.; Woo, J.-W. In Industrial robot calibration method using denavit—Hatenberg parameters, 2017 17th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), IEEE: 2017; pp 1834-1837.

- Dai, Y.; Xiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, W.; Zhang, Q. J. A., A review of spatial robotic arm trajectory planning. 2022, 9 (7), 361. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Li, G.; Ding, K. J. I. A., Obstacle avoidance path planning for apple picking robotic arm incorporating artificial potential field and a* algorithm. 2023.

- Cheng, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, X.; Gao, J.; Qiao, T. J. J. o. I. I. I., An improved RRT-Connect path planning algorithm of robotic arm for automatic sampling of exhaust emission detection in Industry 4.0. 2023, 33, 100436. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xu, L. J. J. o. K. S. U.-C.; Sciences, I., Path planning algorithm of robot arm based on improved RRT* and BP neural network algorithm. 2023, 35 (8), 101650. [CrossRef]

- Agirrebeitia, J.; Avilés, R.; De Bustos, I. F.; Ajuria, G. J. M.; Theory, M., A new APF strategy for path planning in environments with obstacles. 2005, 40 (6), 645-658. [CrossRef]

| Connect rod serial number(i) | /mm | /(°) | /mm | (°) | (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | -90 | 92.5 | ± 180 | |

| 2 | 189 | 90 | 0 | ± 135 | |

| 3 | 189 | -90 | 0 | ± 150 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -170~+180 | |

| 5 | 0 | -90 | 36 | ± 120 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 86 | ± 360 |

| Algorithm name | Average search time/s | Average number of node samples | Average path length | Search Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRT | 4.203 | 5703 | 2112.441 | 91% |

| RRT* | 7.262 | 5513 | 1686.495 | 93% |

| P-RRT* | 7.768 | 5539 | 1690.284 | 93% |

| HP-RRT* | 3.015 | 2544 | 1713.812 | 100% |

| HP-APF-RRT* | 1.039 | 2290 | 1467.493 | 100% |

| Algorithm name | Average search time/s | Average number of node samples | Average path length | Search Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRT | 4.625 | 6304 | 1935.640 | 73% |

| RRT* | 10.415 | 6297 | 1530.290 | 61% |

| P-RRT* | 11.925 | 6488 | 1549.293 | 67% |

| HP-RRT* | 2.237 | 1978 | 1445.297 | 100% |

| HP-APF-RRT* | 0.889 | 1576 | 1286.505 | 100% |

| Algorithm name | Average path length | Average optimized path length |

|---|---|---|

| scenario one | 1467.493 | 1461.463 |

| scenario two | 1286.505 | 1275.741 |

| Algorithm name | Average grasp time/s | Average search time/s | Search Success Rate |

| RRT | 49.65 | 24.75 | 85% |

| RRT* | 58.74 | 36.71 | 80% |

| P-RRT* | 53.61 | 32.95 | 85% |

| HP-RRT* | 24.85 | 7.56 | 100% |

| HP-APF-RRT* | 19.79 | 5.62 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).