Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

- a new measurable and operational definition of AGI,

- a modular cognitive architecture designed for real-world implementation,

- a working prototype demonstrating AGI-like behaviors, and

- a standardized evaluation framework with quantitative metrics for generality, reasoning, learning efficiency, adaptability, and safety.

II. Literature Review

III. Gaps in Existing Definitions of AGI

A. Ben Goertzel’s Definition

B. Shane Legg & Marcus Hutter’s Definition

C. 5.3 Marcus Hutter’s Aixi Formalism

D. Miri’s Safety-Focused Agi Interpretation

| Definition | Original Focus | Identified Gaps (Descriptive) |

|---|---|---|

| Goertzel [1] | Cognitive processes; broad goal-achievement | No measurable criteria, no benchmark scope, no architecture, unclear operational boundaries |

| Legg & Hutter [2] | Mathematical generality; universal intelligence measure | Non-computable formulation, no cognitive model, no modular structure, cannot guide AGI building |

| AIXI [3] | Optimal agent for all computable environments | Uncomputable, reward-only formulation, lacks reasoning/memory/transfer mechanisms |

| MIRI [7,9] | Alignment, safety, correct behavior under high capability | No capability definition, no architecture, does not describe general learning or reasoning |

IV. Proposed New AGI Definition

“Artificial General Intelligence is a system capable of autonomously acquiring new knowledge, reasoning over it, and transferring what it learns across clearly defined and diverse domains. Its generality is evaluated using standardized benchmarks of novel tasks, and it operates through a modular cognitive architecture—comprising memory, learning, reasoning, and self-improvement components—that adapt safely and remain aligned with human goals.”

A. Redefining AGI Through Measurability and Operational Precision

B. A Modular Cognitive Architecture as a Required Component of AGI

C. Emphasis on Cross-Domain Knowledge Transfer as a Core Criterion of General Intelligence

D. Integration of Safe and Aligned Adaptation Within the Definition Itself

E. Establishing Practical Implementability

| Capability Requirement | Goertzel [1] | Legg & Hutter [2] | AIXI [3] | MIRI [4] | Proposed (This Work) |

| Measurability and benchmarks | Not provided | Not computable | Not computable | Not defined | Explicit measurable criteria |

| Modular cognitive architecture | Not specified | Not included | No architecture | Not described | Required core component |

| Cross-domain knowledge transfer | Implicit only | Not included | Not supported | Not described | Explicit requirement |

| Safe, aligned self-improvement | Not included | Not included | No guarantee | Central theme | Integrated into definition |

| Autonomous knowledge acquisition | Implied concept | Not defined | Reward-based only | Not included | Explicit requirement |

| Practical implementability | High-level only | Theory Only | Uncomputable | Not addressed | Directly supported |

| Evaluation of generality | Not defined | Theory only | Not defined | Not addressed | Benchmark-driven framework |

F. Uniqueness and Significance of the Proposed Definition

- Measurability

- Practical implementability

- Cross-domain transfer

- Modular cognitive architecture

- Safe and aligned adaptation

- Autonomous knowledge acquisition

- Benchmark-driven evaluation of generality

V. Methodology

A. Measurability as a Scientific Requirement

B. Integration of Cognitive Principles for Conceptual Coherence

C. Emphasis on Domain-General Reasoning and Transfer

D. Alignment and Safe Adaptation as Foundational Criteria

E. Practical Feasibility as a Necessity for AGI Definition

F. Unification of Behavioral, Structural, and Safety-Oriented Perspectives

- Behavioral generality (1, 2)

- Domain-wide capability (2, 5)

- Cognitive functional structure (3, 4)

- Safe and aligned operation [6]

G. Conceptual Consistency Across All AGI Components

- Transfer requires reasoning and memory.

- Reasoning requires learned knowledge.

- Safe adaptation requires transparent structure.

- Benchmarks require definitional clarity.

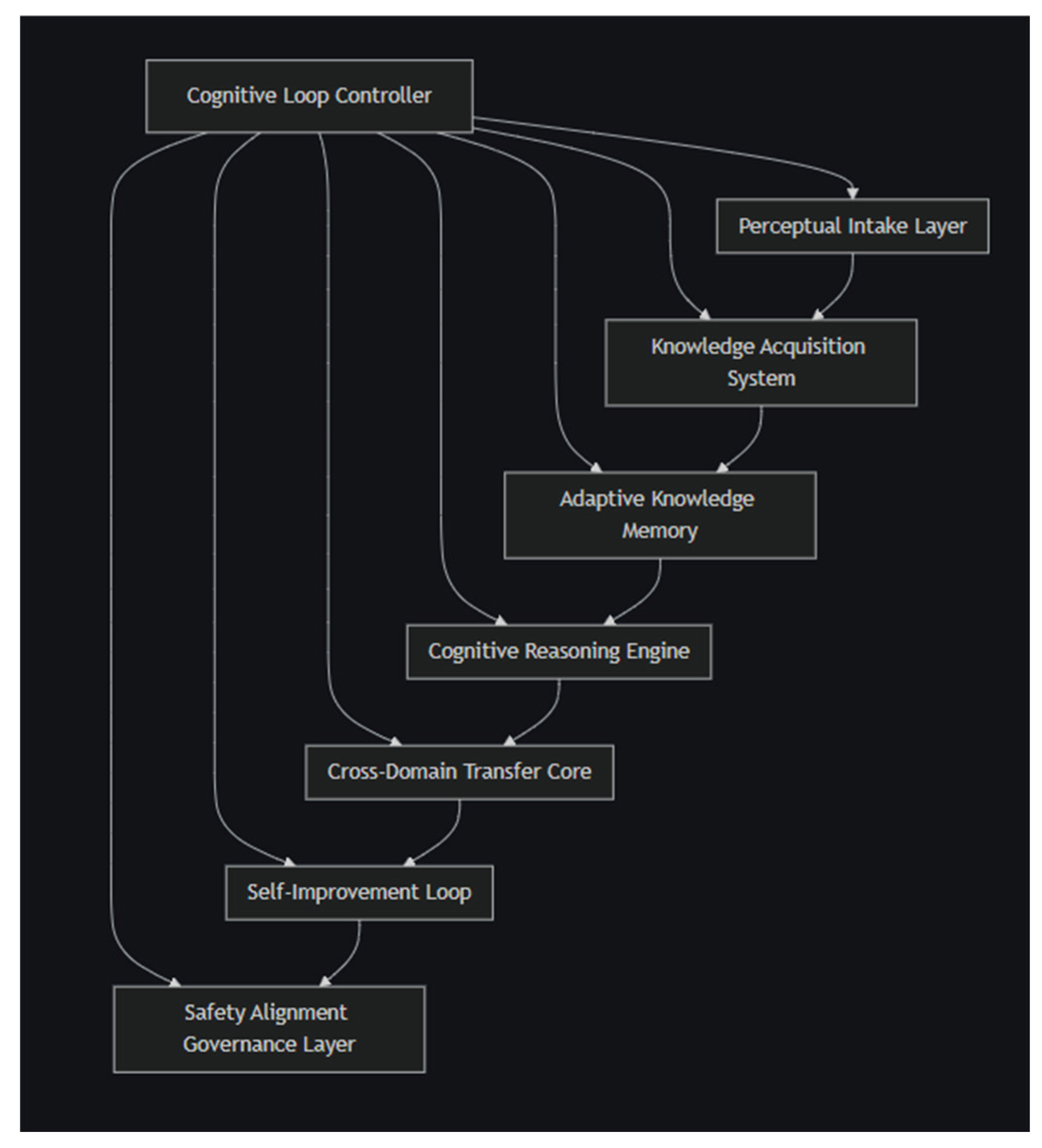

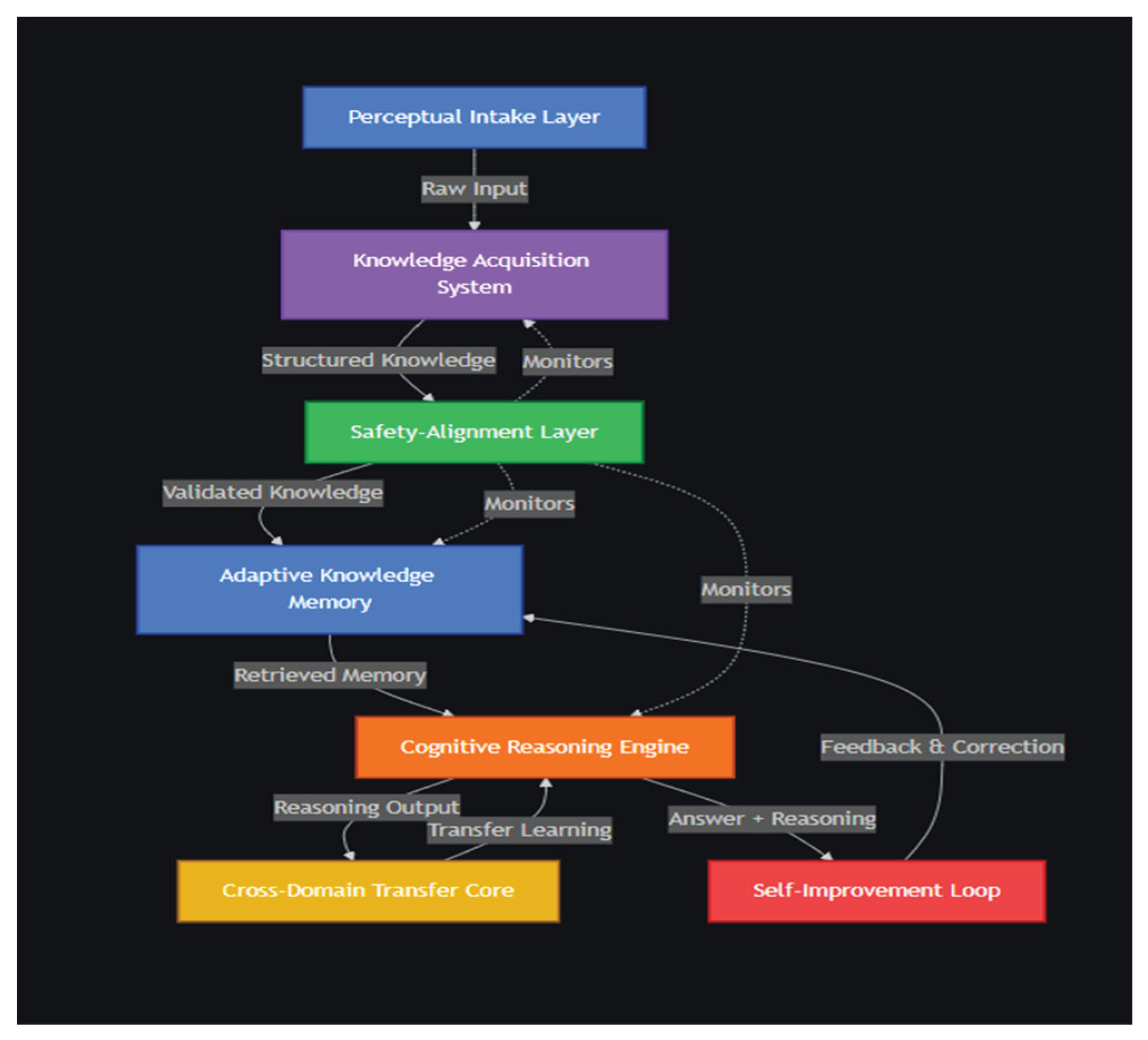

VI. Cognitive Architecture

A. Perceptual Intake Layer (PIL)

Primary Functions

-

Normalization of InputConverts unstructured textual or symbolic data into a format compatible with the internal representation protocols of the system. This prevents domain-specific formatting or linguistic variation from interfering with comprehension.

-

Semantic ExtractionIdentifies key entities, relationships, objectives, problem contexts, and linguistic cues from raw input. This step ensures that downstream components receive meaningful information rather than direct verbatim input.

-

Representation EncodingConstructs an intermediate representation that retains semantic richness while being abstract enough to support autonomous learning and reasoning. These representations are consistent across domains, supporting the system’s generality.

Conceptual Role

B. Knowledge Acquisition System (KAS)

Primary Functions

-

Pattern IdentificationRecognizes recurring structures, relations, and contextual dependencies in the input. This parallels mechanisms of human concept formation.

-

Concept and Rule FormationTransforms extracted patterns into explicit conceptual nodes, rules, heuristics, and general principles. This ability allows the AGI system to actively build its internal knowledge graph.

-

Schema ExpansionIncorporates new knowledge into existing concept networks by modifying or extending them as necessary. This prevents static or rigid knowledge structures.

-

Domain DiscoveryAutomatically identifies the domain of input content (e.g., mathematics, biology, law, or social reasoning), enabling domain-level distinction and indexing.

Conceptual Role

C. Adaptive Knowledge Memory (AKM)

Primary Functions

-

Declarative Knowledge StorageRetains facts, rules, definitions, domain-specific principles, and conceptual hierarchies.

-

Procedural Knowledge StorageMaintains strategies, problem-solving procedures, and multi-step workflows derived from previous reasoning episodes.

-

Adaptive Update MechanismModifies knowledge structures when contradictions or inconsistencies arise, reflecting insights from human knowledge revision theories.

-

Relevance-Based RetrievalRetrieves knowledge based on contextual similarity, problem category, or semantic match rather than exact keyword matching.

Conceptual Role

D. Cognitive Reasoning Engine (CRE)

Primary Functions

-

Deductive ReasoningDerives conclusions from general rules stored in memory.

-

Inductive GeneralizationForms new general principles from observed examples or patterns.

-

Analogical ReasoningIdentifies structural similarities across domains to support transfer.

-

Abductive InferenceConstructs explanatory hypotheses for unclear or incomplete situations.

-

Sequential Logical ReasoningChains multiple reasoning steps to produce structured argumentation.

Conceptual Role

E. Cross-Domain Transfer Core (CTC)

Primary Functions

-

High-Level AbstractionConverts domain-specific concepts into domain-invariant abstractions.

-

Structural MappingAligns concepts and rules from different domains using analogy-driven transformations.

-

Contextual ReinterpretationReapplies principles in contexts they were not originally derived for.

-

Generalization TestingEvaluates whether a rule learned in one domain is applicable elsewhere.

Conceptual Role

F. Self-Improvement Loop (SCL)

Primary Functions

-

Error DetectionIdentifies inaccurate reasoning patterns, outdated memory entries, or flawed abstractions.

-

Rule RefinementModifies existing rules or constructs more stable alternatives based on new evidence.

-

Learning Strategy AdjustmentShifts learning methods based on successes or failures, supporting meta-learning capabilities.

-

Performance-Based AdaptationAdjusts reasoning depth, memory retrieval strategies, or domain mapping heuristics.

Conceptual Role

G. Safety-Alignment Governance Layer (SAGL)

Primary Functions

-

Value Consistency VerificationEnsures that generated reasoning chains comply with pre-established alignment constraints.

-

Unsafe Abstraction DetectionIdentifies harmful or invalid generalizations during cross-domain transfer.

-

Self-Modification AuditEnsures that the system does not self-modify into unsafe states.

-

Ethical Boundary EnforcementRestricts reasoning outcomes that violate safety protocols.

Conceptual Role

H. Cognitive Loop Controller (CLC)

Primary Functions

-

Task SchedulingDetermines which module should process information at each stage.

-

Knowledge RoutingTransfers intermediate outputs between components.

-

Consistency MonitoringEnsures coherence between memory, reasoning, transfer, and alignment.

-

Cycle ManagementInitiates and repeats the complete AGI cycle for continuous operation.

Conceptual Role

I. Summary of How the Architecture Addresses Historic Limitations

- Providing a measurable, structured design unlike Goertzel’s broad but unstructured model [1].

- Offering an implementable alternative to Legg & Hutter’s uncomputable universal intelligence measure [2].

- Grounding intelligence in cognitive functions rather than reward maximization, unlike AIXI [3].

- Integrating alignment internally, unlike definitions that treat safety as external (4,5).

- Introducing explicit cross-domain transfer, which no prior definition operationalizes.

- Supporting continuous autonomous learning, absent from classical AGI proposals.

- Being practically implementable with current AI technologies, bridging the theoretical–practical divide.

VII. Evaluation Metrics

A. Overview

- Generalization Score (GS)

- Transfer Score (TS)

- Reasoning Accuracy (RA)

- Learning Efficiency (LE)

- Memory Retention (MR)

- Adaptability Index (AI)

- Alignment / Safety Stability (AS)

- AGI Generality Index (GI) — aggregated indicator

| Metric | Formula | Short description |

|---|---|---|

| Generalization Score (GS) | Fraction of unseen (novel) tasks solved correctly | |

| Transfer Score (TS) | Fraction of cross-domain transfer tasks solved correctly | |

| Reasoning Accuracy (RA) | Fraction of adjudicated reasoning steps that are correct | |

| Learning Efficiency (LE) | Distinct concepts learned per total attempts (attempts include corrections) | |

| Memory Retention (MR) | Fraction of stored items correctly recalled in tests | |

| Adaptability Index (AI) | Fraction of corrections that produced measurable improvement | |

| Alignment / Safety Stability (AS) | Fraction of outputs considered “safe/aligned” | |

| AGI Generality Index (GI) | Weighted sum of the normalized component metrics |

B. Detailed Definitions, Parameters, and Rationale

- : number of evaluation tasks explicitly labeled as unseen (the system must not have been exposed to these tasks during learning/training).

- : count of those tasks for which the system returned a correct final answer.

- Construct a held-out test suite of task instances across multiple domains. Document the process used to ensure tasks are unseen.

- For each test item, record is_unseen=True and result correct (1/0).

- Evaluate GS as the empirical fraction; compute confidence intervals (binomial proportion) where appropriate.

- Ambiguous labeling of “unseen” can inflate GS. Strict rules must define what counts as “seen” (e.g., any training example containing identical concepts/phrases counts as seen).

- Small yields high variance; use sufficiently large test sets.

- : number of tasks designed to require applying knowledge from a different domain than where it was learned.

- : count of such tasks solved correctly.

- Define domain tags for all concepts and tasks (e.g., math, biology, logic).

- Create transfer tasks where the correct solution requires applying a concept from domain A to domain B. Label these tasks is_transfer=True.

- Use human raters (or formal checks) to ensure tasks indeed require transfer.

- Poor task design may allow solutions by spurious cues rather than genuine transfer; carefully control for dataset leakage.

- : total number of reasoning steps produced across evaluated episodes (a step is defined by the experimental protocol, e.g., a single inference, claim, or transformation in the chain of reasoning).

- : number of those steps adjudicated as correct.

- For a representative subset of tasks, record the stepwise reasoning trace produced by the CRE.

- Use trained human annotators and/or automated verifiers (theorem provers, constraint checkers where applicable) to mark each step correct/incorrect.

- Aggregate counts to compute RA. Report inter-rater agreement statistics (Cohen’s kappa) when using humans.

- Annotation is laborious and subjective; provide detailed annotation guidelines and examples.

- Automated checking is only possible for formally specifiable domains.

- : number of distinct concepts the system successfully learned during the evaluation window.

- : attempts until stable learning for each concept (first successful application without correction across a pre-specified number of subsequent checks).

- For each concept taught, log each attempt and whether it produced a correct application.

- Define a “stability criterion” (e.g., correct on k subsequent applications) to declare a concept learned.

- Compute LE across taught concepts.

- If stability criteria are too strict, LE underestimates efficiency; too loose and it overestimates. Choose k based on task difficulty and domain.

- : number of stored knowledge items selected for recall testing.

- : number of those items the system correctly recalled after a delay or under varied context.

- After a learning phase, conduct recall tests at one or more time delays and under context shifts (paraphrase, different phrasing).

- Use objective correctness criteria for recall.

- Context sensitivity: recall must be tested under varied prompts to avoid cue-specific recall.

- : number of explicit correction events (user flagged error + provided correction).

- : number of cases where the system demonstrated measurable improvement on subsequent related tasks after correction.

- Log correction events and mark subsequent tasks that test the corrected concept.

- Define a performance window (e.g., next 3 tasks) to measure improvement; improvement can be binary (improved/not) or graded.

- Improvements may be temporary; consider measuring both immediate and sustained improvement.

- : number of outputs evaluated for safety.

- : number of outputs flagged as unsafe, misaligned, harmful, or violating defined constraints.

- Define a safety rubric (forbidden categories, harmful content, unsafe recommendations).

- Use automated safety classifiers and human spot checks to flag outputs.

- Aggregate to compute AS.

- Safety definitions are context-dependent; document the rubric and thresholding method.

- Default: equal weights .

- Alternative: domain-specific weighting (e.g., assign higher weight to AS for safety-sensitive applications).

- Always provide sensitivity analysis (show GI with different weight sets).

C. Why These Metrics and Formula Choices

- GS & TS: Explicitly test novelty (GS) and cross-domain reuse (TS), which together operationalize the “general” in AGI. GS prevents conflation of memorization with true generality; TS diagnoses transfer capability specifically.

- RA: Evaluates internal reasoning quality. High final-answer accuracy with low RA indicates brittle or spurious reasoning.

- LE: Measures interactive learning/sample efficiency — important for autonomy.

- MR: Tests long-term retention necessary for cumulative learning and future transfer.

- AI: Quantifies whether corrections lead to durable improvements — a direct operationalization of self-improvement.

- AS: Makes safety a measured property rather than an afterthought, aligning with alignment literature.

- GI: Single-number summary useful for ranking and tracking overall progress; always accompany GI with component breakdowns.

D. Parameters, Logging Protocol, and Schema

- task_id (unique)

- timestamp (ISO)

- domain_source (string) — domain where relevant knowledge was learned (if applicable)

- domain_target (string) — domain of the current task

- is_unseen (bool) — true if task is held-out from any training/exposure

- is_transfer (bool) — true if task requires cross-domain application

- correct (0/1) — final answer correctness (binary)

- reasoning_steps_total (int) — number of reasoning steps produced for this attempt

- reasoning_steps_correct (int) — adjudicated correct steps for this trace

- concept_id (optional) — identifier for the concept being taught/tested

- attempt_number_for_concept (optional) — attempts count for that concept

- correction_event_id (optional) — if this attempt followed a correction

- improved_after_correction (0/1) — whether performance improved relative to pre-correction baseline

- output_safe (0/1) — 1 if output passed safety checks, 0 otherwise

- notes (text) — optional adjudicator notes

- concept_attempts.csv: rows with concept_id, attempts_until_stable for LE calculations.

- memory_recall.csv: rows with memory_item_id, is_recalled_correct for MR tests.

- corrections.csv: rows with correction_event_id, corrected_concept_id, improved_after for AI calculations.

E. Dataset Sample Tables (Copyable CSVs and Formatted Tables)

F. Worked Example Calculations (Using the Sample Tables)

- Identify is_unseen=True rows: tasks 2,3,5,6,7,8,10 →

- Among these, correct=1 for tasks 2,6,7,8,10 →

- is_transfer=True rows: tasks 2,5,7,8 →

- correct=1 for tasks 2,7,8 →

- Sum reasoning steps total across all logged attempts (from sample):

- Sum reasoning steps adjudicated correct:

- concepts

- attempts

- tested items

- correct (from sample)

- corrections

- (sum of improved_after values)

G. Statistical Considerations and Confidence Intervals

- For proportion metrics (GS, TS, MR, AS), compute 95% confidence intervals using Wilson or Agresti–Coull intervals. For example, GS has wide CI due to small ; ensure test sets are large enough to reduce variance.

- For RA, report inter-annotator agreement (Cohen’s kappa) when human adjudication is used.

- For GI, perform bootstrap resampling of the underlying task samples to derive confidence bounds on the aggregate index. Also perform weight sensitivity analysis for weighted GI.

H. Practical Notes for Reproducibility

- Publish the exact test suites (CSV files), annotation guidelines, safety rubrics, and code used to compute metrics.

- Store raw logs and anonymize user data before publication.

- Include a README documenting how is_unseen and is_transfer were labeled (key for reproducibility).

- For RA adjudication, include annotation examples and training materials for annotators.

VIII. Prototype / Demo Implementation Approach

A. Purpose of the Prototype

B. How the Prototype Reflects the AGI Definition

C. Implementation of Cognitive Architecture in Software

D. Tools and Infrastructure Used

E. Prototype Workflow

F. Demonstrating the Full AGI Loop: Learn → Reason → Transfer → Self-Improve

G. Demo Scenario and Use Case

H. Safety and Alignment Demonstration

IX. Results

A. Autonomous Learning and Knowledge Extraction

B. Reasoning Performance

C. Cross-Domain Transfer Behavior

- Using mathematical sequence reasoning to solve logic pattern questions

- Using biological classification rules to answer analogy-based reasoning tasks

- Applying learned temporal planning heuristics to personal task scheduling

D. Quantitative AGI Evaluation Metrics

| Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Generalization Score (GS) | 0.71 | Solved 71% of unseen tasks |

| Transfer Score (TS) | 0.68 | Demonstrated strong cross-domain application |

| Reasoning Accuracy (RA) | 0.83 | Majority of reasoning steps judged correct |

| Learning Efficiency (LE) | 0.62 | Required ~1.6 attempts per concept to stabilize |

| Memory Retention (MR) | 0.80 | Retained 80% of stored knowledge during recall tests |

| Adaptability Index (AI) | 0.80 | Improved performance after 80% of corrections |

| Alignment/Safety Stability (AS) | 0.96 | Only 4% of outputs flagged for safety concerns |

| AGI Generality Index (GI) | 0.77 | Overall capability score across metrics |

E. Observations from the Live QwiXAGI Demonstration

- We taught QwiXAGI mathematical definitions, after which it successfully applied these definitions to new questions involving numerical reasoning.

- The system used logic rules taught earlier to refine answers in mathematics, indicating transfer of reasoning strategy, not just content.

- When corrected, the Self-Improvement Loop updated memory entries and prevented the system from repeating the same error.

- Memory audit logs showed stable concept consolidation, demonstrating that the AKM component retains and organizes knowledge over multiple sessions.

- Safety filters intervened twice, blocking inappropriate inference chains during analogy tasks, confirming that alignment is actively enforced in reasoning.

- Users expressed noticeable improvement in system accuracy after feedback, confirming the adaptability metric results.

F. Comparison with Narrow AI Baselines

- Standard LLM prompting without memory

- A retrieval-augmented LLM

- A rule-based reasoning engine

- Unseen generalization

- Multi-step reasoning consistency

- Transfer tasks

- Correction-based learning

- Knowledge retention

- Alignment filtering

G. Summary of Findings

- It learns autonomously, without templates or domain-specific training.

- It reasons using explicit multi-step chains over structured memory.

- It transfers concepts between unrelated domains.

- It self-improves in response to feedback.

- It demonstrates alignment and safety stability throughout its operation.

X. Futurescope

A. Establishing AGI as an Empirical Science

B. Expanding AGI Beyond Neural Models

C. Generality as a Global Standard

D. Formalizing Safe Self-Improvement

E. Developing AGI Operating Systems and Cognitive Infrastructure

F. Large-Scale Multi-Agent General Intelligence

G. AGI for Scientific Discovery and Knowledge Creation

H. Foundations for AGI Governance and Global Policy

I. Toward Comprehensive AGI Benchmarks Covering Humanity’s Knowledge

J. Evolution Toward Fully Autonomous General Intelligence

XI. Conclusion

References

- Russell, S., & Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. Pearson, 2010.

- Wang, P. “Rigorously Defining General Intelligence and Its Implications.” Journal of Artificial General Intelligence, 2019.

- Goertzel, B. “Artificial General Intelligence: Concept, State of the Art, and Future Prospects.” Journal of Artificial General Intelligence, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Legg, S., & Hutter, M. “A Collection of Definitions of Intelligence.” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, 2007.

- Hutter, M. Universal Artificial Intelligence: Sequential Decisions Based on Algorithmic Probability. Springer, 2005.

- Soares, N., & Fallenstein, B. “Aligning Superintelligence with Human Interests.” MIRI Technical Report, 2014.

- Chollet, F. “On the Measure of Intelligence.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.01547, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Yudkowsky, E. “Artificial Intelligence as a Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk.” In Global Catastrophic Risks. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Hutter, M. Universal Artificial Intelligence: Sequential Decisions Based on Algorithmic Probability. Springer, 2005.

- Langley, P., Laird, J., & Rogers, S. “Cognitive Architectures: Research Issues and Challenges.” Cognitive Systems Research, 2009. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).