Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

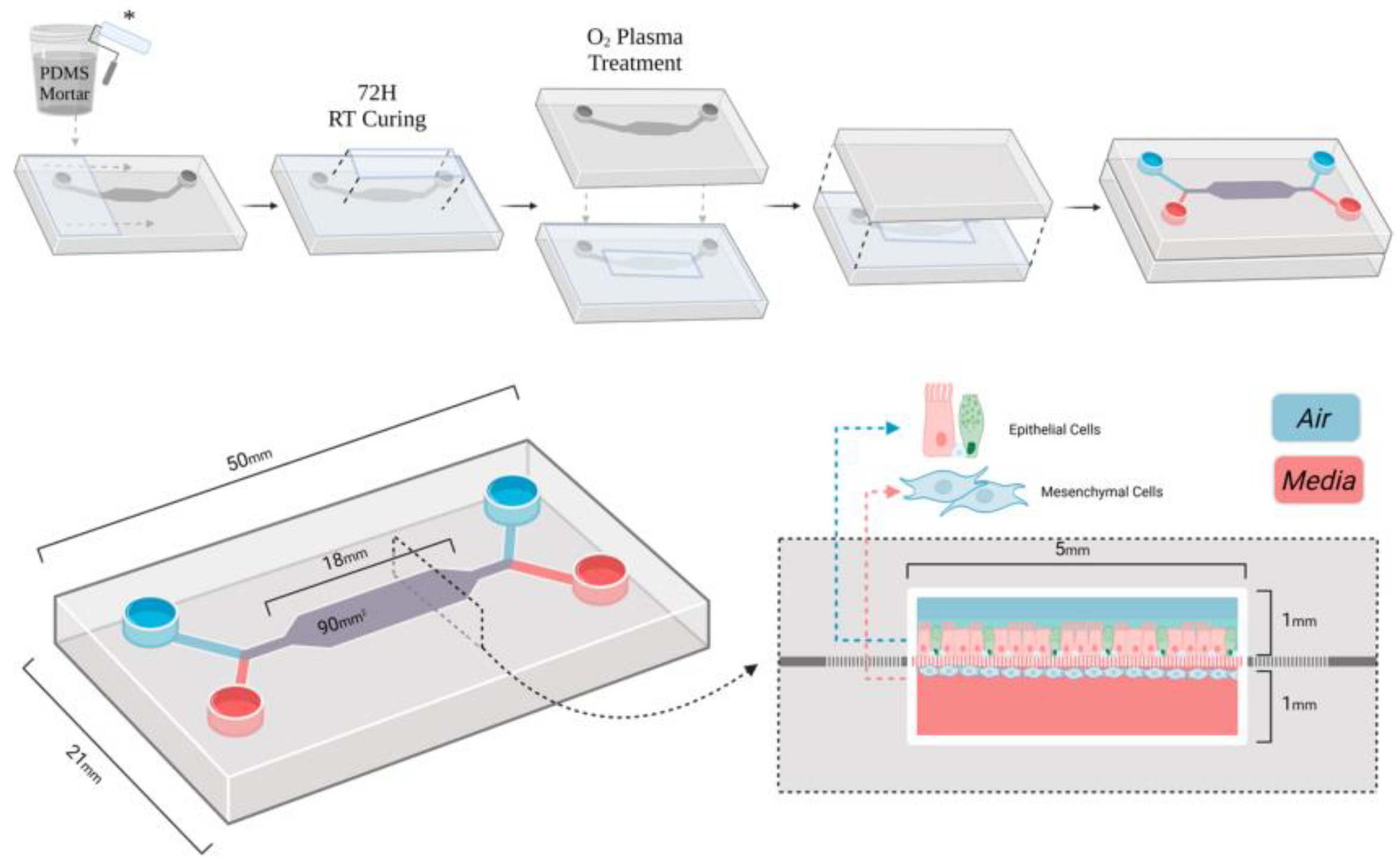

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Study Description

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

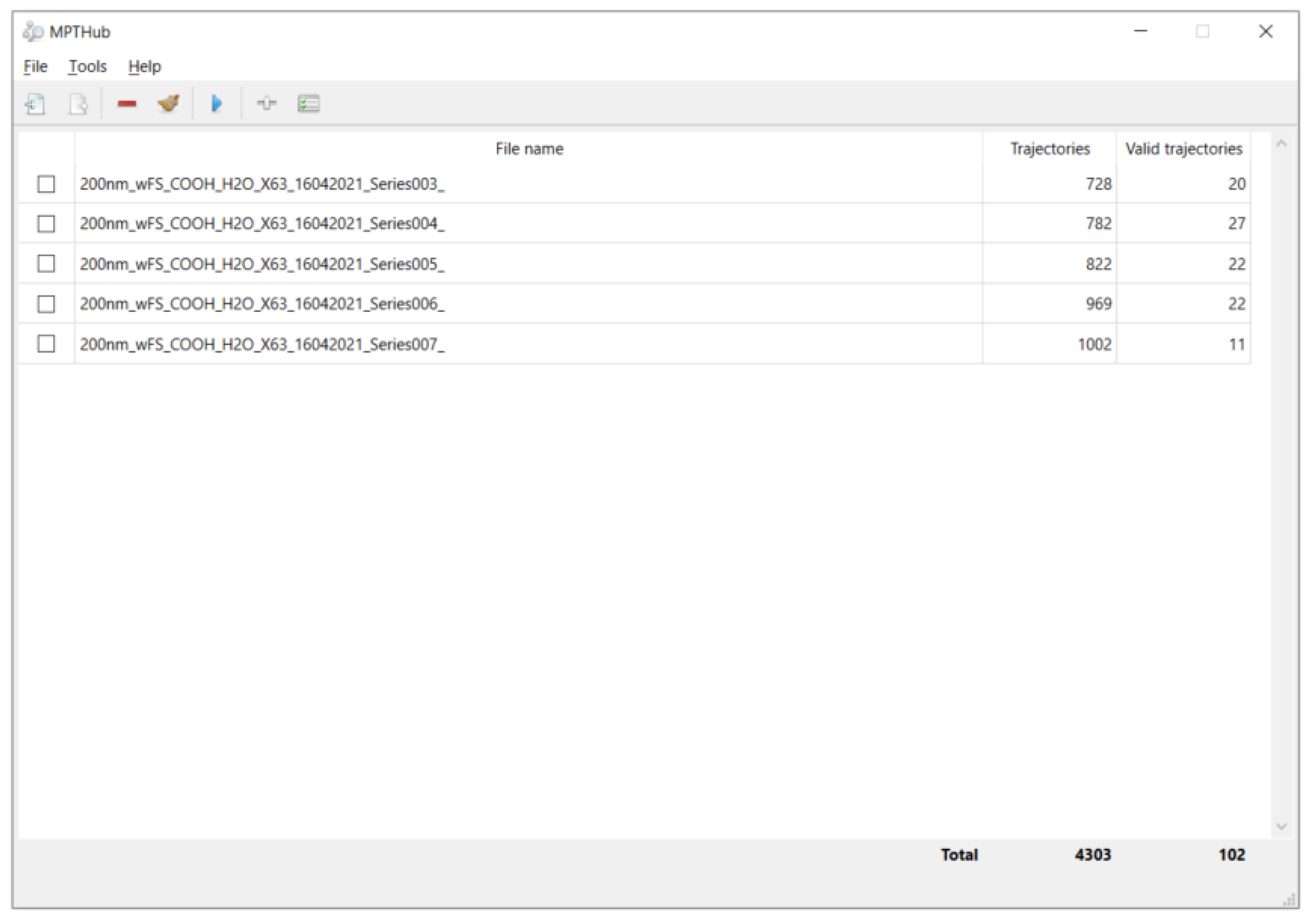

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Formulation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Particle Size on Transport

3.2. Role of Surface Wettability in Mucus Penetration

3.3. Combined Influence of Size and Wettability

3.4. Comparison with Previous Studies and Implications

4. Conclusion

References

- Fröhlich, E. Non-Cellular Layers of the Respiratory Tract: Protection against Pathogens and Target for Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 992. [CrossRef]

- Zha, D.; Mahmood, N.; Kellar, R.S.; Gluck, J.M.; King, M.W. Fabrication of PCL Blended Highly Aligned Nanofiber Yarn from Dual-Nozzle Electrospinning System and Evaluation of the Influence on Introducing Collagen and Tropoelastin. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 6657–6670. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.W.; Song, I.H.; Um, S.H. Role of Physicochemical Properties in Nanoparticle Toxicity. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1351–1365. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, T.M.; Kimna, C.; Lieleg, O. A pH-stable, mucin based nanoparticle system for the co-delivery of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 215, 102–112. [CrossRef]

- Abdelkawi, A.; Slim, A.; Zinoune, Z.; Pathak, Y. Surface Modification of Metallic Nanoparticles for Targeting Drugs. Coatings 2023, 13, 1660. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, S.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Su, Y.; Kwak, G.; Zuo, X.; Rao, D.; et al. A Two-Pronged Pulmonary Gene Delivery Strategy: A Surface-Modified Fullerene Nanoparticle and a Hypotonic Vehicle. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 15225–15229. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Wheeler, K.; Ribbeck, K. Mucins and Their Role in Shaping the Functions of Mucus Barriers. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 34, 189–215. [CrossRef]

- Dash, P.K.; Chen, C.; Kaminski, R.; Su, H.; Mancuso, P.; Sillman, B.; Zhang, C.; Liao, S.; Sravanam, S.; Liu, H.; et al. CRISPR editing of CCR5 and HIV-1 facilitates viral elimination in antiretroviral drug-suppressed virus-infected humanized mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [CrossRef]

- Poland, C.A.; Hiéronimus, L.; Okhrimenko, D.V.; Hoffman, J.W. Biopersistence of man-made vitreous fibres (MMVF) / synthetic vitreous fibres (SVF): advancing from animal models to acellular testing. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2025, 22, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Lu, Y.; Hou, S.; Liu, K.; Du, Y.; Huang, M.; Feng, H.; Wu, H.; Sun, X. Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Srinivasan, H.; Gupta, J.; Mitra, S. Lipid lateral diffusion: mechanisms and modulators. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 7763–7796. [CrossRef]

- Zha, D.; Gamez, J.; Ebrahimi, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Verma, N.; Poe, A.J.; White, S.; Shah, R.; Kramerov, A.A.; Sawant, O.B.; et al. Oxidative stress-regulatory role of miR-10b-5p in the diabetic human cornea revealed through integrated multi-omics analysis. Diabetologia 2025, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Hirota, M.; Shibata, R.; Matsuura, T.; Komatsu, K.; Saruta, J.; Att, W. The 3D theory of osseointegration: material, topography, and time as interdependent determinants of bone–implant integration. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2025, 11, 1–37. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. (2025). Building a Structured Reasoning AI Model for Legal Judgment in Telehealth Systems.

- Wang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, H. Assessing the Role of Adaptive Digital Platforms in Personalized Nutrition and Chronic Disease Management. World J. Innov. Mod. Technol. 2025, 8, 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y. Application of Nanocarrier-Based Targeted Drug Delivery in the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Vascular Diseases. J. Med. Life Sci. 2025, 1, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Tjakra, M.; Lidayová, K.; Avenel, C.; Bergström, C.A.; Hossain, S. Machine learning framework for investigating nano- and micro-scale particle diffusion in colonic mucus. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Meziu, E. (2025). Nanoparticle interactions with mucosal barriers.

- Jiang, A.Y.; Lathwal, S.; Meng, S.; Witten, J.; Beyer, E.; McMullen, P.; Hu, Y.; Manan, R.S.; Raji, I.; Langer, R.; et al. Zwitterionic Polymer-Functionalized Lipid Nanoparticles for the Nebulized Delivery of mRNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 32567–32574. [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Khatibi, M.; Ashrafizadeh, S.N. Synergistic effects of dielectrophoretic and magnetophoretic forces on continuous cell separation via pinched flow fractionation. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37. [CrossRef]

- Chime, S.A.; Momoh, M.A. (2025). PEGylated Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery Applications. In PEGylated Nanocarriers in Medicine and Pharmacy (pp. 107-136). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).