Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

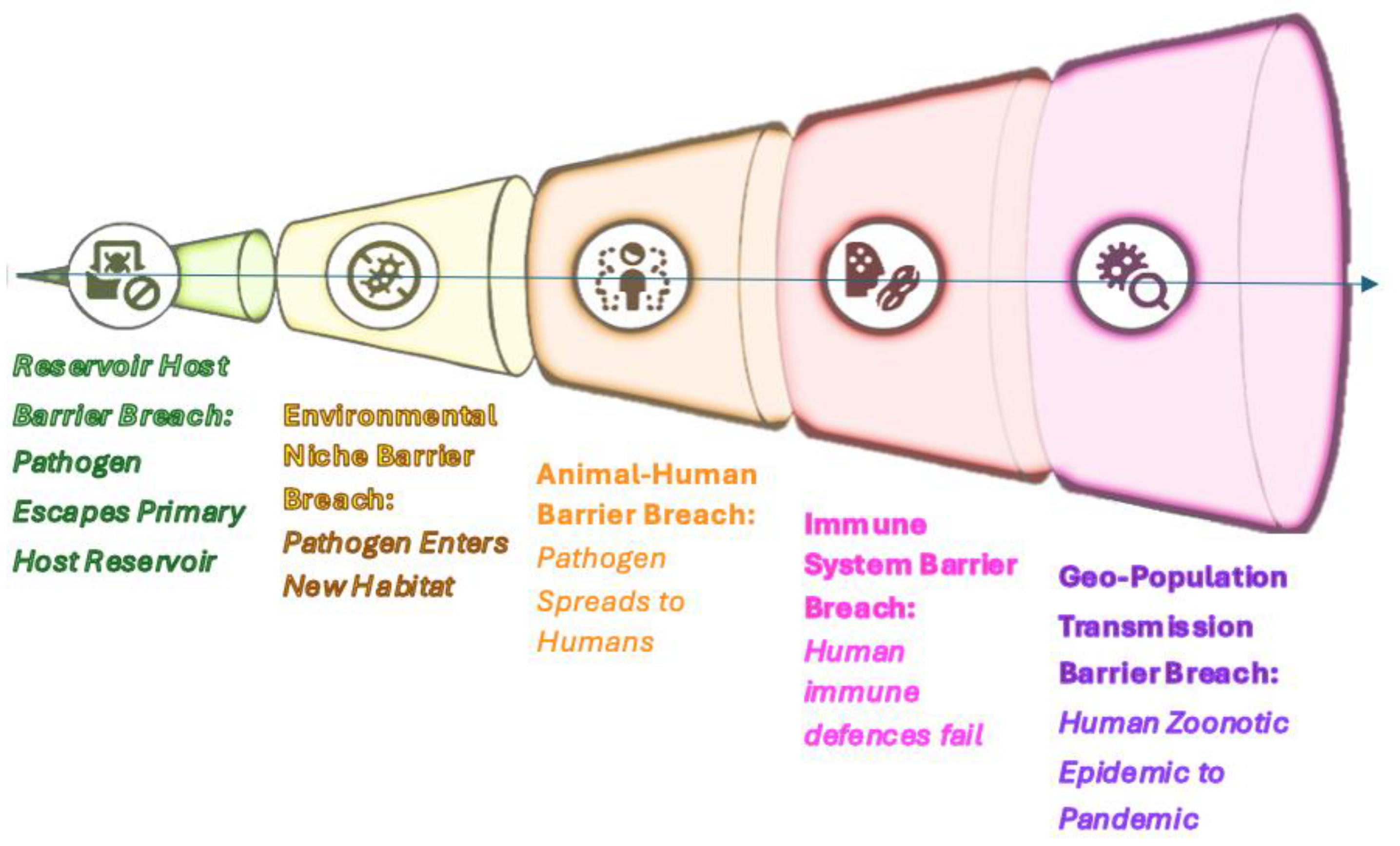

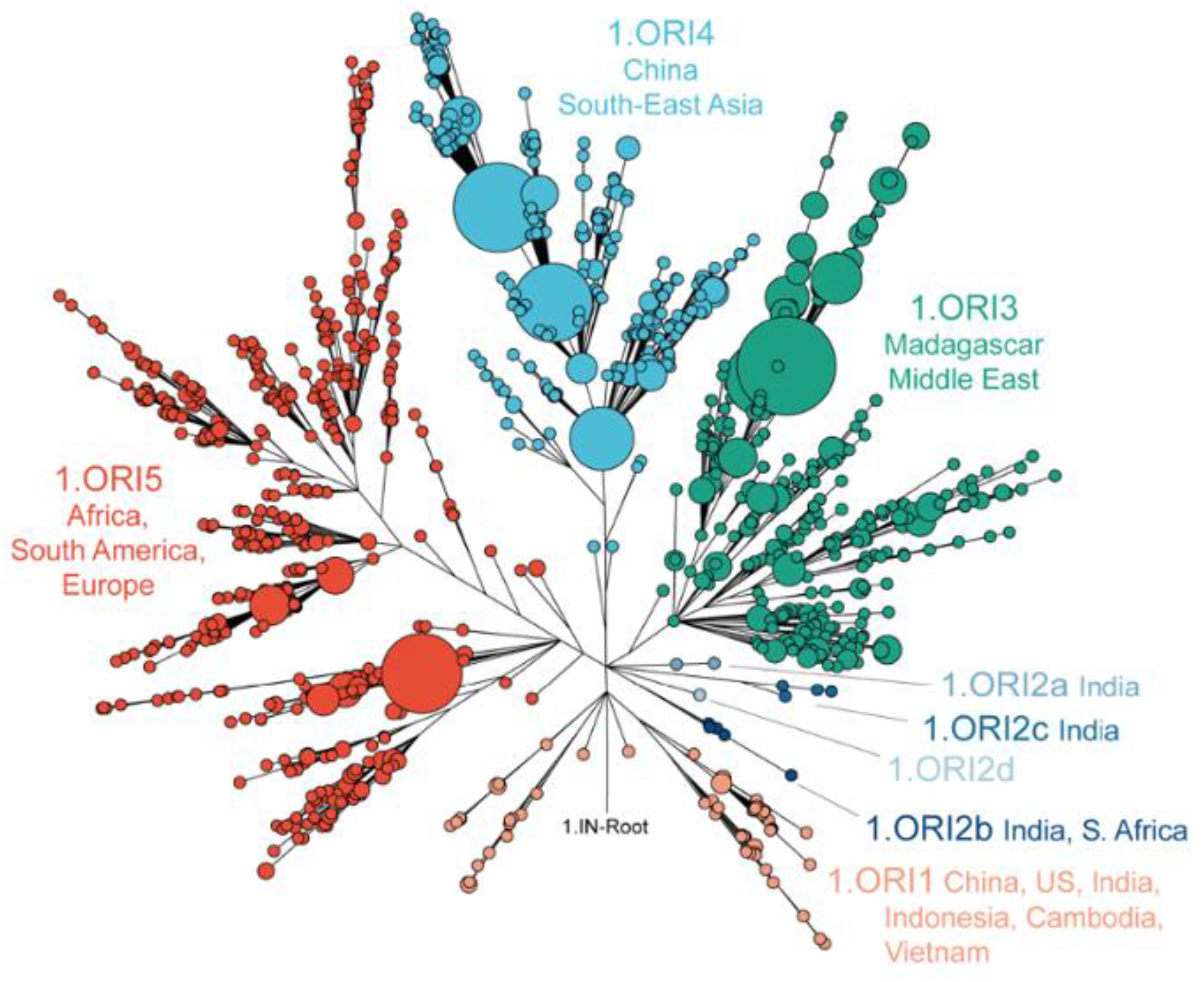

The emergence of the Third Plague Pandemic in 19th-century Yunnan, linked to Yersinia pestis strain 1.ORI, remains incompletely understood. Applying a One Health framework, this study investigates how human-driven ecological and societal disruptions during the 19th century compromised zoonotic barriers, facilitating initial spillover and a bottleneck event that enabled global spread. Our interdisciplinary methodology analyzes Qing dynasty gazetteers, historical medical records, and environmental data, integrated with biological evidence on transmission dynamics involving commensal rats and the flea vector Xenopsylla cheopis. Results indicate that convergent factors—including widespread deforestation, intensified mining/agriculture, population growth, high synanthropic rat densities, and the disruptions of the Panthay Rebellion—collectively created a high-risk interface for zoonotic transfer. Critically, comorbidities such as malnutrition, heavy metal exposure, and opium use likely eroded host immune resilience in both rodent and human populations, amplifying transmission. Yunnan’s rapid socio-ecological transformation was thus a critical catalyst for pandemic emergence. This analysis underscores how historical land-use, demographic shifts, and public health conditions shaped zoonotic risk. Crucially, a One Health assessment must analyze interactions across time and space, recognizing that environmental, biological, and socioeconomic changes occur on non-uniform temporal scales. This spatiotemporal perspective provides a framework that offers deeper insight into past pandemic origins and for anticipating contemporary vulnerabilities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Understanding the Risk of Zoonotic Diseases Through Analysing Their Biological, Environmental, & Societal Context

2. Methods and Materials

Research Framework Through an Integrated Approach

- Digital gazetteer databases, including the Erudition Database of Local Gazetteers(《方志数据库》)and CNKI’s Local Chronicles Collection, were systematically consulted to extract primary references to plague outbreaks, rodent infestations, and ecological degradation across Yunnan during the Qing period. These digital platforms aggregate county-level and prefectural records from multiple editions, enabling comparative tracking of terminology evolution (e.g., 鼠疫) and spatial distribution patterns over time.

- Printed historical compilations, such as the Guangxu-era Yunnan Tongzhi(《云南通志》)and selected fascicles of the Qing Veritable Records(《清实录》), provided authoritative accounts of state responses to epidemic outbreaks, regional famines, and military–epidemic interactions. These sources were used to cross-reference local narratives and identify macro-level policy changes (e.g., granary failures, mining decrees, population relocations) that shaped zoonotic conditions in 19th-century Southwest China.

- Secondary literature by Joseph Esherick, Edward Rhoads, and William Rowe, which proved helpful for triangulating demographic and political shifts.

3. Results

- Natural spread: Formation of primary (wildlife-maintained) and secondary (adapted to new hosts and environments) plague foci across Eurasia.

-

Geographic constraints:

- ○

- Permafrost boundary and Sahara-Gobi arid belt as ecological barriers.

- ○

- Early Pleistocene migration of Tatera rodents (e.g., T. indica), which may have shaped host-vector dynamics.

- Human-driven expansion: Global dispersal via trade routes, notably the gly− strain (1.ORI lineage) from South Asia.

- 1.

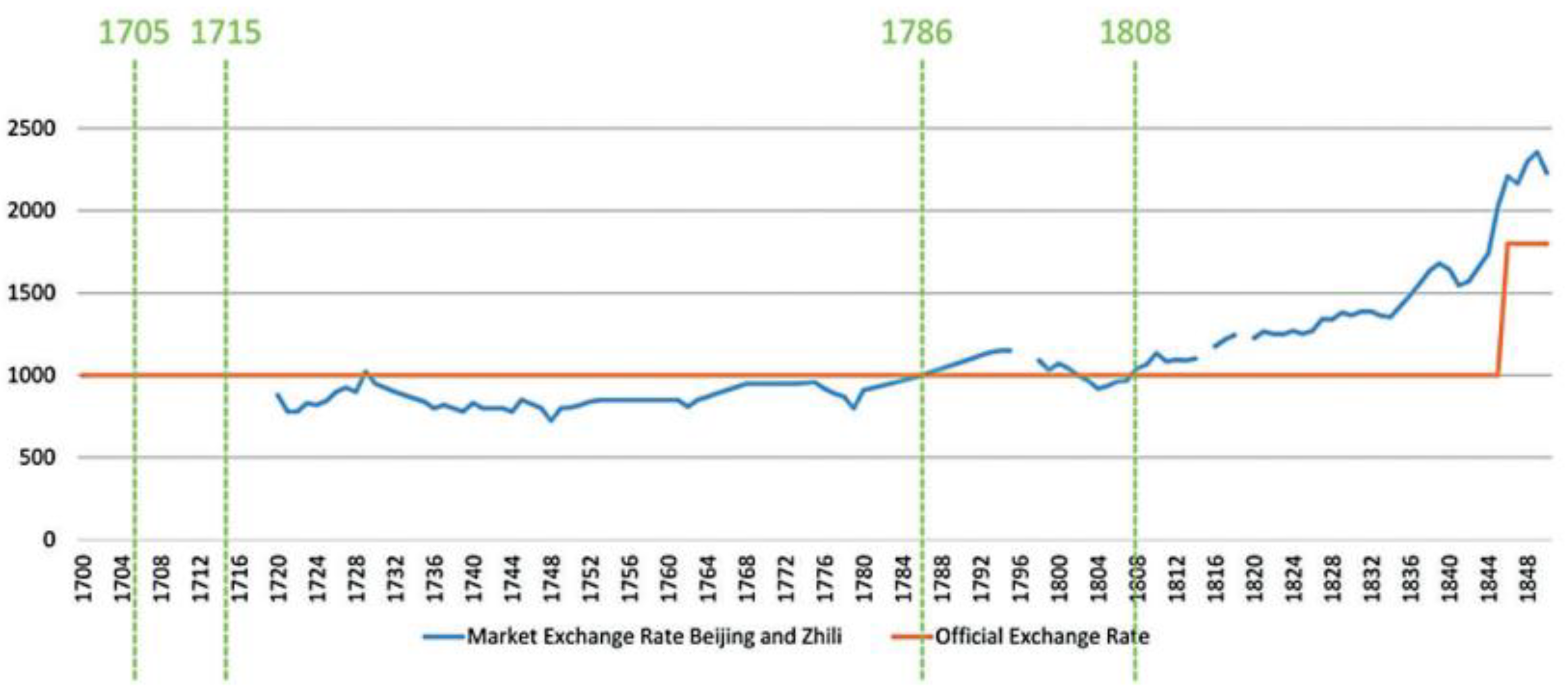

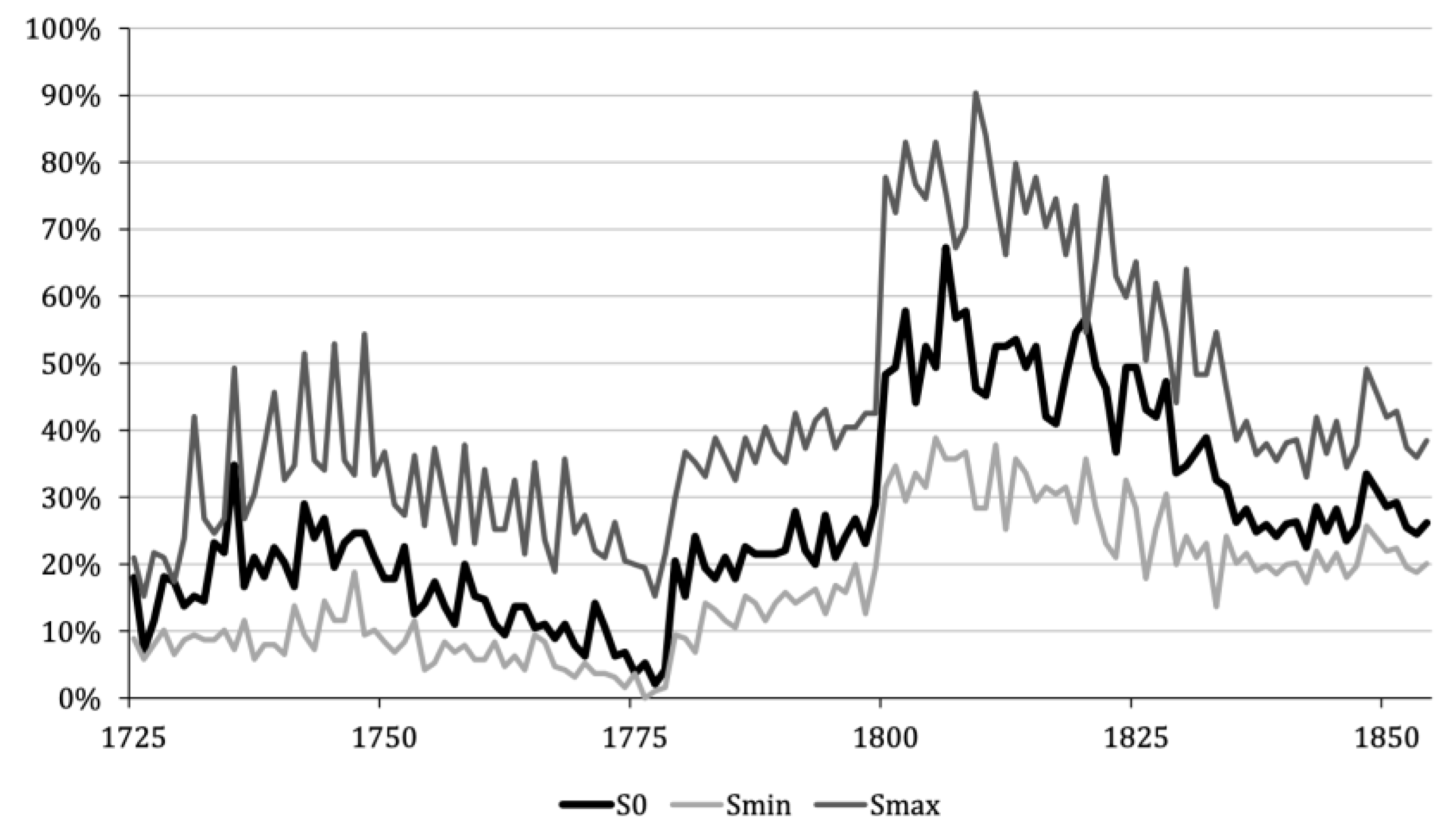

- Real Wage Decline & the Devaluation of Coin Currencies

- 2.

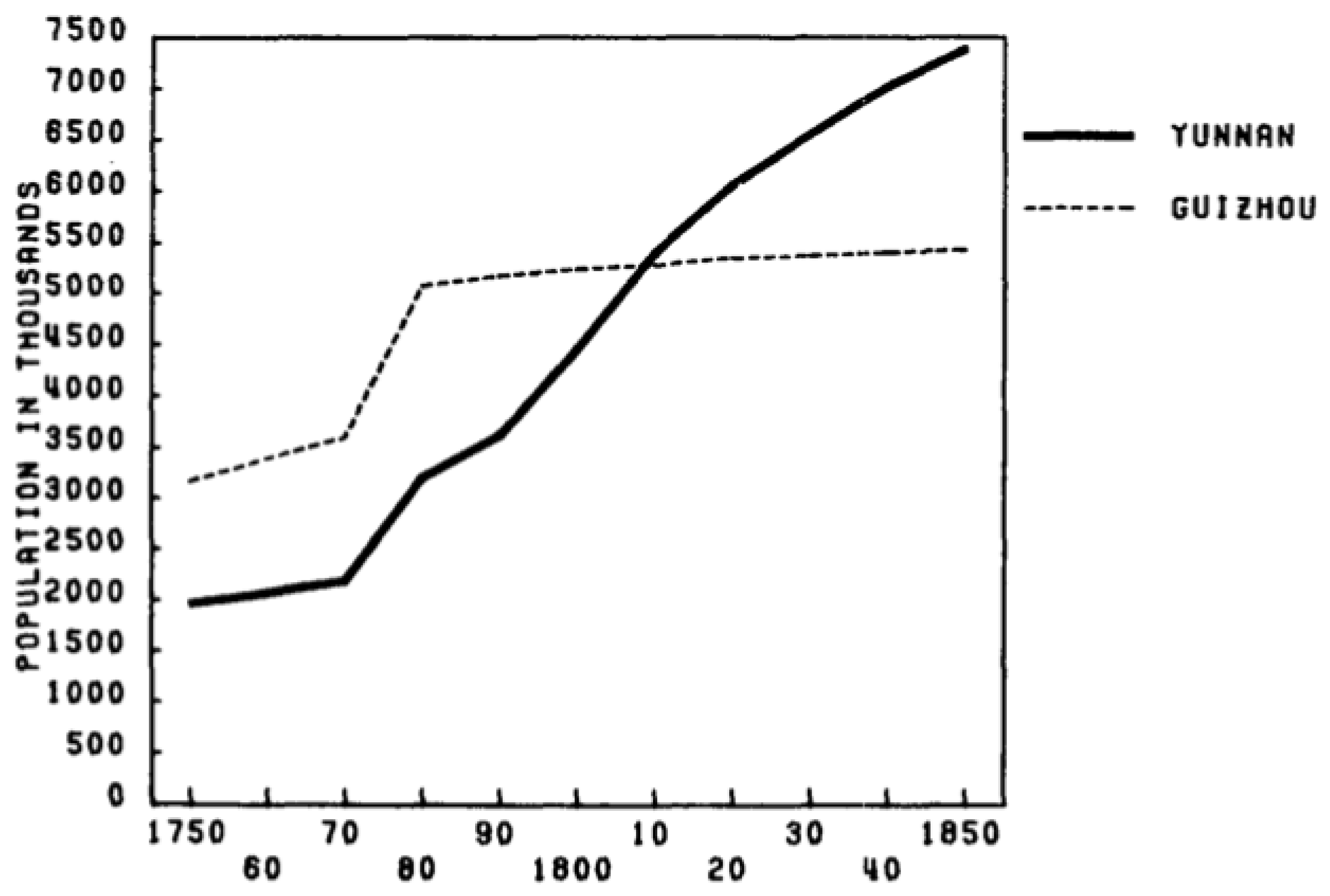

- Rapid Population Growth and Deforestation in late 18th and 19th century

- 3.

- Erosion leading to Heavy Metal Contamination in Lake Water

“Between the 1860s and 1890 CE, the EFs of Hg, Pb and Zn calculated based on the pre-anthropogenic background are above 1, and the Pb isotope ratios also showed higher values. This may be due to the influence of historical metal production in the late Qing Dynasty. Our analysis indicates that the use of pre-industrial sediment as a geochemical background in pollution studies underestimates the trace metal pollution in Erhai Lake. The EFs of Hg, Pb and Zn referenced to the pre-anthropogenic baseline are used in the pollution assessment in this work.”.[85], (p.67)

- Dose and Immunity: A healthy rat with a strong immune system can potentially inoculate itself against a low dose of the bacteria. Rats that survive infection and develop antibodies help decrease the spread of plague within the population [130]

- Genetic Diversity: Genetic diversity within the rat population is crucial for developing effective immune responses. Populations with high genetic variability are better at limiting large outbreaks, while genetically homogenous populations (due to bottlenecks) are at higher risk [131].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Plowright, R. K., Hudson, P. J., McCallum, H., Kessler, M. K., Eby, P., Wright, A. M., & Smith, M. J. (2024). Ecological countermeasures to prevent pathogen spillover and subsequent pandemics. Nature Communications, 15(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Plowright, R. K., Hudson, P. J., McCallum, H., Kessler, M. K., Eby, P., Wright, A. M., & Smith, M. J. (2024). Ecological countermeasures to prevent pathogen spillover and subsequent pandemics. Nature Communications, 15(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Benedict, C. (1996). Bubonic plague in nineteenth-century China (pp. 70–71). Stanford University Press.

- Bello, D. (2003). The venomous course of southwestern opium: Qing prohibition in Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou in the early nineteenth century. The Journal of Asian Studies, 62(4), 1114. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Li (2023) To What Extent Did the Panthay Rebellion Influence the Yunnan Plague during the Late Qing Dynasty from 1846 to 1872? International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 13(5), 49-76. https://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_13_No_5_October_2023/7.pdf.

- Liang, Y., Zhao, X., Chen, F., Yang, Y., & Ljungqvist, F. C. (2025). Winter–spring drought in Yunnan since the early 19th century and its impact on social governance in China’s southwestern border regions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. S. (李玉尚), & Cao, S. J. (曹树基). (2001). 咸同年间的鼠疫流行与云南人口的死亡 [The spread of plague and mortality in Yunnan during the Xiantong Hui Rebellion]. Qing Shi Yan Jiu [Qing History Journal], (2), 19–32.

- Lee, J. (1982). Food supply and population growth in southwest China, 1250–1850. The Journal of Asian Studies, 41(4), 7. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. (2019). The last copper century: Southwest China and the coin economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1–2), 126–146.

- Von Glahn, R. (2016). The economic history of China: From antiquity to the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Liang, Y., Zhao, X., Chen, F., Yang, Y., & Ljungqvist, F. C. (2025). Winter–spring drought in Yunnan since the early 19th century and its impact on social governance in China’s southwestern border regions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D. (胡蝶). (2014). 清代云南疫病传播的地理规律与环境机制研究 [Research on the geographical laws and environmental mechanisms of epidemics in Yunnan Province during the Qing Dynasty] [Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University].

- Lee, H. F., & Zhang, D. D. (2013). A tale of two population crises in recent Chinese history. Climatic Change, 116(2), 285–308. [CrossRef]

- Hang, X., Sun, Z., He, J., Xin, J., Zhang, S., Zhao, Y., & Hao, Y. (2025). Temporal and spatial effects of extreme drought events on human epidemics over ancient China in 1784–1787 CE. Environmental Health, 24(1), 8.

- Shi, L., Qin, J., Zheng, H., Guo, Y., Zhang, H., Zhong, Y., & Cui, Y. (2021). New genotype of Yersinia pestis found in live rodents in Yunnan Province, China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, 628335.

- Eisen, R. J., Wilder, A. P., Bearden, S. W., Montenieri, J. A., & Gage, K. L. (2007). Early-phase transmission of Yersinia pestis by unblocked Xenopsylla cheopis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) is as efficient as transmission by blocked fleas. Journal of Medical Entomology, 44(4), 678–682.

- Qin, J., Wu, Y., Shi, L., Zuo, X., Zhang, X., Qian, X., & Cui, Y. (2023). Genomic diversity of Yersinia pestis from Yunnan Province, China, implies a potential common ancestor as the source of two plague epidemics. Communications Biology, 6(1), 847.

- Rogaski, R. (2004). Hygienic modernity: Meanings of health and disease in treaty-port China (Vol. 9). University of California Press.

- Lynteris, C. (2024). The figure of the staggering rat: Reading colonial outbreak narratives against the grain of “virus hunting”. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 79(4), 331–344.

- Simond, P. L. (1898). La propagation de la peste. Annales de l’Institut Pasteur.

- Macleod, R. (1988). Introduction. In R. Macleod & M. J. Lewis (Eds.), Disease, medicine, and empire: Perspectives on Western medicine and the experience of European expansion (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Haynes, D. M. (2001). Imperial medicine: Patrick Manson and the conquest of tropical disease. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Achtman, M., Zurth, K., Morelli, G., Torrea, G., Guiyoule, A., & Carniel, E. (1999). Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96(24), 14043–14048.

- Achtman, M., Morelli, G., Zhu, P., Wirth, T., Diehl, I., Kusecek, B., ... & Keim, P. (2004). Microevolution and history of the plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(51), 17837–17842.

- Mas Fiol, G., Lemoine, F., Mornico, D., Bouvier, G., Andrades Valtuena, A., Duchene, S., ... & Pizarro-Cerda, J. (2024). Global evolutionary patterns of Yersinia pestis and its spread into Africa. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Suntsov, V. V. (2021). Host aspect of territorial expansion of the plague microbe Yersinia pestis from the populations of the Tarbagan marmot (Marmota sibirica). Biology Bulletin, 48, 1367–1379.

- Li, Y. S. (李玉尚). (2002). 近代中国的鼠疫应对机制——以云南、广东和福建为例 [The response mechanism to plague in modern China: The cases of Yunnan, Guangdong and Fujian]. Southeast Asian Studies, (01), 114–127, 192.

- Hu, D. (胡蝶). (2014). 清代云南疫病传播的地理规律与环境机制研究 [Research on the geographical laws and environmental mechanisms of epidemics in Yunnan Province during the Qing Dynasty] [Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University].

- Skurnik M., Peippo A., Ervela E. (2000). Characterization of the O-antigen gene cluster of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and the cryptic O-antigen gene cluster of Yersinia pestis shows that the plague bacillus is most closely related to and has evolved from Y. pseudotuberculosis serotype O:1b. Mol. Microbiol., 37(2), 316–330. [CrossRef]

- Achtman, M., Morelli, G., Zhu, P., Wirth, T., Diehl, I., Kusecek, B., ... & Keim, P. (2004). Microevolution and history of the plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(51), 17837-17842.

- Morelli, G., Song, Y., Mazzoni, C. J., Eppinger, M., Roumagnac, P., Wagner, D. M., ... & Achtman, M. (2010). Phylogenetic diversity and historical patterns of pandemic spread of Yersinia pestis. Nature Genetics, 42(12), 1–14.

- Suntsov, V. V. (2021). Host aspect of territorial expansion of the plague microbe Yersinia pestis from the populations of the Tarbagan marmot (Marmota sibirica). Biology Bulletin, 48, 1367–1379.

- Morelli, G., Song, Y., Mazzoni, C. J., Eppinger, M., Roumagnac, P., Wagner, D. M., ... & Achtman, M. (2010). Phylogenetic diversity and historical patterns of pandemic spread of Yersinia pestis. Nature genetics, 42(12), 1-14.

- Morelli, G., Song, Y., Mazzoni, C. J., Eppinger, M., Roumagnac, P., Wagner, D. M., ... & Achtman, M. (2010). Phylogenetic diversity and historical patterns of pandemic spread of Yersinia pestis. Nature genetics, 42(12), 1-14.

- Suntsov, V. V. (2021). Host aspect of territorial expansion of the plague microbe Yersinia pestis from the populations of the Tarbagan marmot (Marmota sibirica). Biology Bulletin, 48, 1367–1379.

- Mas Fiol, G., Lemoine, F., Mornico, D., Bouvier, G., Andrades Valtuena, A., Duchene, S., ... & Pizarro-Cerda, J. (2024). Global evolutionary patterns of Yersinia pestis and its spread into Africa. bioRxiv, 24. [CrossRef]

- Mas Fiol, G., Lemoine, F., Mornico, D., Bouvier, G., Andrades Valtuena, A., Duchene, S., ... & Pizarro-Cerda, J. (2024). Global evolutionary patterns of Yersinia pestis and its spread into Africa. bioRxiv, 24. [CrossRef]

- Aplin, K. P., Suzuki, H., Chinen, A. A., Chesser, R. T., Ten Have, J., Donnellan, S. C., ... & Cooper, A. (2011). Multiple geographic origins of commensalism and complex dispersal history of black rats. PloS one, 6(11), e26357.

- Shi, L., Yang, G., Zhang, Z., Xia, L., Liang, Y., Tan, H., ... & Wang, P. (2018). Reemergence of human plague in Yunnan, China in 2016. PLoS ONE, 13(6), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Plowright, R. K., Hudson, P. J., McCallum, H., Kessler, M. K., Eby, P., Wright, A. M., & Smith, M. J. (2024). Ecological countermeasures to prevent pathogen spillover and subsequent pandemics. Nature Communications, 15(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. (2019). The Last Copper Century: Southwest China and the Coin Economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1–2), 126–146. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. (2019). The Last Copper Century: Southwest China and the Coin Economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1–2), 126–146. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, A. (2008). Concurrent but non-integrable currency circuits: Complementary relationships among monies in modern China and other regions. Financial History Review, 15(1), 17–36.

- von Glahn, R. (2016). The economic history of China: From antiquity to the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Peng, X.(彭信威). (2007). 中国货币史[Zhongguo huobi shi / A monetary history of China]. Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (Original work published 1954).

- Cao, J. (2019). The Last Copper Century: Southwest China and the Coin Economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1–2), 126–146. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, A. (2008). Concurrent but non-integrable currency circuits: Complementary relationships among monies in modern China and other regions. Financial History Review, 15(1), 17–36.

- Von Glahn, R. (2016). The economic history of China: From antiquity to the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Peng, X.(彭信威). (2007). 中国货币史[Zhongguo huobi shi / A monetary history of China]. Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (Original work published 1954).

- Allen, R. C., Bassino, J.-P., Ma, D., Moll-Murata, C., & van Zanden, J. L. (2011). Wages, prices, and living standards in China, 1738–1925: In comparison with Europe, Japan, and India. The Economic History Review, 64(S1), 8–38. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. (2019). The Last Copper Century: Southwest China and the Coin Economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1–2), 126–146. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, A. (2008). Concurrent but non-integrable currency circuits: Complementary relationships among monies in modern China and other regions. Financial History Review, 15(1), 17–36.

- von Glahn, R. (2016). The economic history of China: From antiquity to the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Peng, X.(彭信威). (2007). 中国货币史[Zhongguo huobi shi / A monetary history of China]. Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (Original work published 1954).

- Vogel, H. U. (2018). Fuel for the smelters: Copper mining and deforestation in Northeastern Yunnan during the High Qing, 1700–1850. In C. Daniels (Ed.), Southwest China in a regional and transnational perspective (pp. 213–257). Brill.

- Cao, J. (2019). The Last Copper Century: Southwest China and the Coin Economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1-2),137.

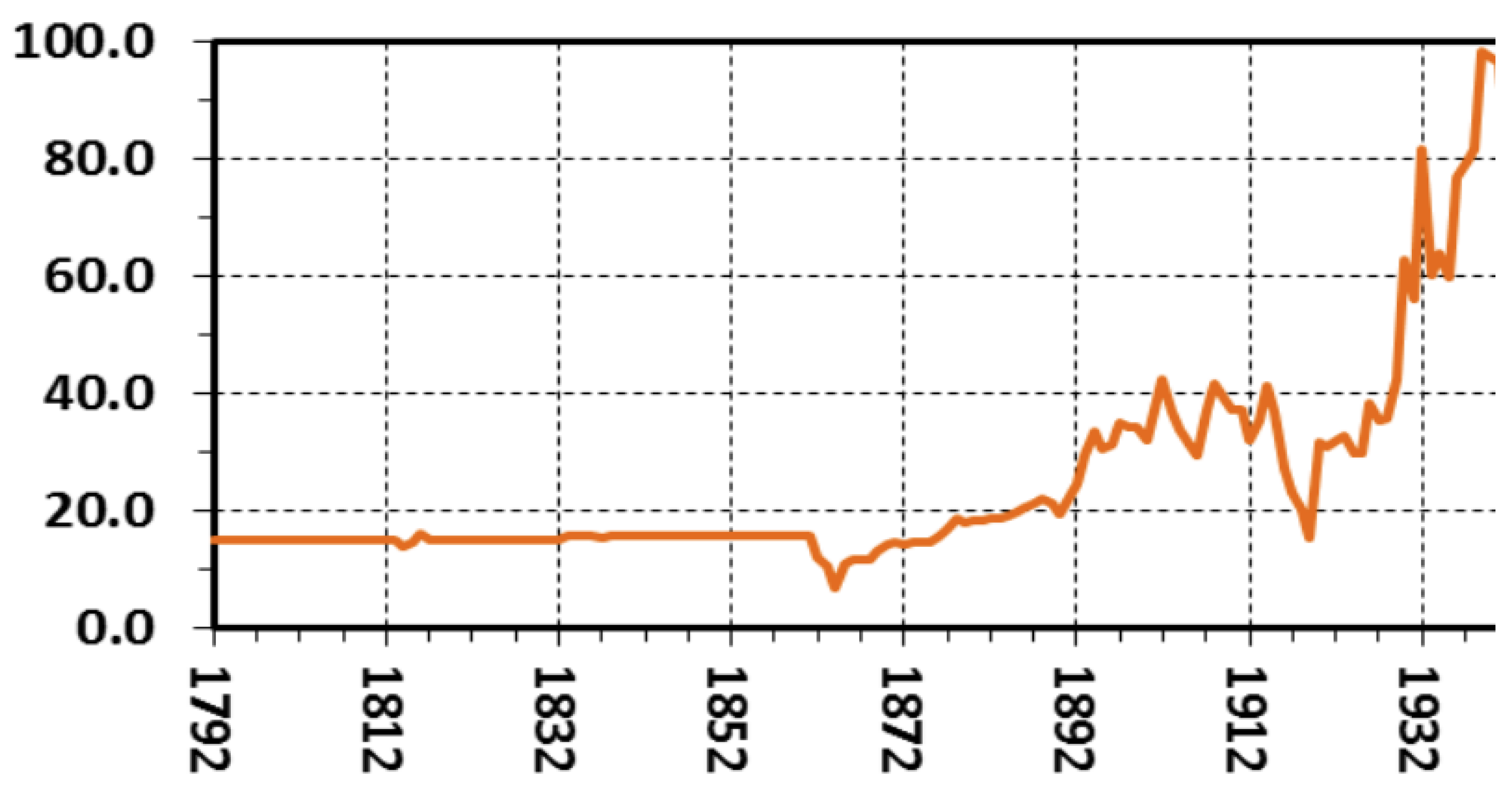

- Flup, M. (2016). Gold, silver, and the US dollar: 1792–1971. Gold Geologist. https://www.goldgeologist.com/mercenary_musings/musing-160425-Gold-Silver-and-the-US-Dollar-1792-1971.pdf.

- Hu, Y. (胡岳峰). (2021). 清代银钱比价波动研究(1644–1911)[A study on the fluctuation of silver-copper currency exchange rates in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)] [Master’s thesis, East China Normal University]. [CrossRef]

- Long, Y. (龙云), & Lu, H. (卢汉) (Chief Editors), Zhou, Z. (周钟岳) (Compiler). (1949). Xin zuan Yunnan tong zhi [新纂云南通志, New Compilation of the General Gazetteer of Yunnan] [Block-printed edition].

- Hu, G. (胡刚). (2015). 明清云南府域灾害研究 [A study on disasters in Yunnan Prefecture during the Ming and Qing Dynasties] [Doctoral dissertation, Yunnan University].

- Cao, J. (2019). The Last Copper Century: Southwest China and the Coin Economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1-2),136. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Kim, N. (2023). Overlooked Silver: Reassessing Ming–Qing Silver Supplies. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 83(1), 19-20.

- Lee, J. (1982). Food supply and population growth in southwest China, 1250–1850. The Journal of Asian Studies, 41(4), 7.

- Yunnan Provincial Archives, DG 19/12/17 (Daoguang 19 [1839]).

- Xie, Bin. 2014. Ming Qing shiqi Yunnan Xundian diqu kaifa jincheng yanjiu 明清时期云南寻甸地区开发进程研究 [The Development Process of Xundian, Yunnan in the Ming and Qing Periods]. MA thesis, Yunnan University.

- Guangxu Revised Kunming County Gazetteer 光绪《续修昆明县志》, juan 7 “Wuxing zhi” 卷七《五行志》, c. 1906.

- Benedict, C. (2011). The social environment of tobacco. In Golden-silk smoke: A history of tobacco in China, 1550–2010 (pp. 73–106). University of California Press.

- Bello, D. (2003). The venomous course of southwestern opium: Qing prohibition in Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou in the early nineteenth century. The Journal of Asian Studies, 62(4), 1111-1112. [CrossRef]

- Bello, D. (2003). The venomous course of southwestern opium: Qing prohibition in Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou in the early nineteenth century. The Journal of Asian Studies, 62(4), 1114. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. (1982). Food supply and population growth in southwest China, 1250–1850. The Journal of Asian Studies, 41(4), 741. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. (2010). The legacy of opium cultivation in China: Ecological and agricultural impacts. Environmental History, 15(4), 682–705.

- Moula, M. S., Hossain, M. S., Farazi, M. M., Ali, M. H., & Mamun, M. A. A. (2018). Effects of consecutive two years tobacco cultivation on soil fertility status at Bheramara Upazilla in Kushtia District. J. Rice Res, 6(1), 1-4.

- Lee, J. (1982). Food supply and population growth in southwest China, 1250–1850. The Journal of Asian Studies, 41(4), 740. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. (1982). Food supply and population growth in southwest China, 1250–1850. The Journal of Asian Studies, 41(4), 722-723.. [CrossRef]

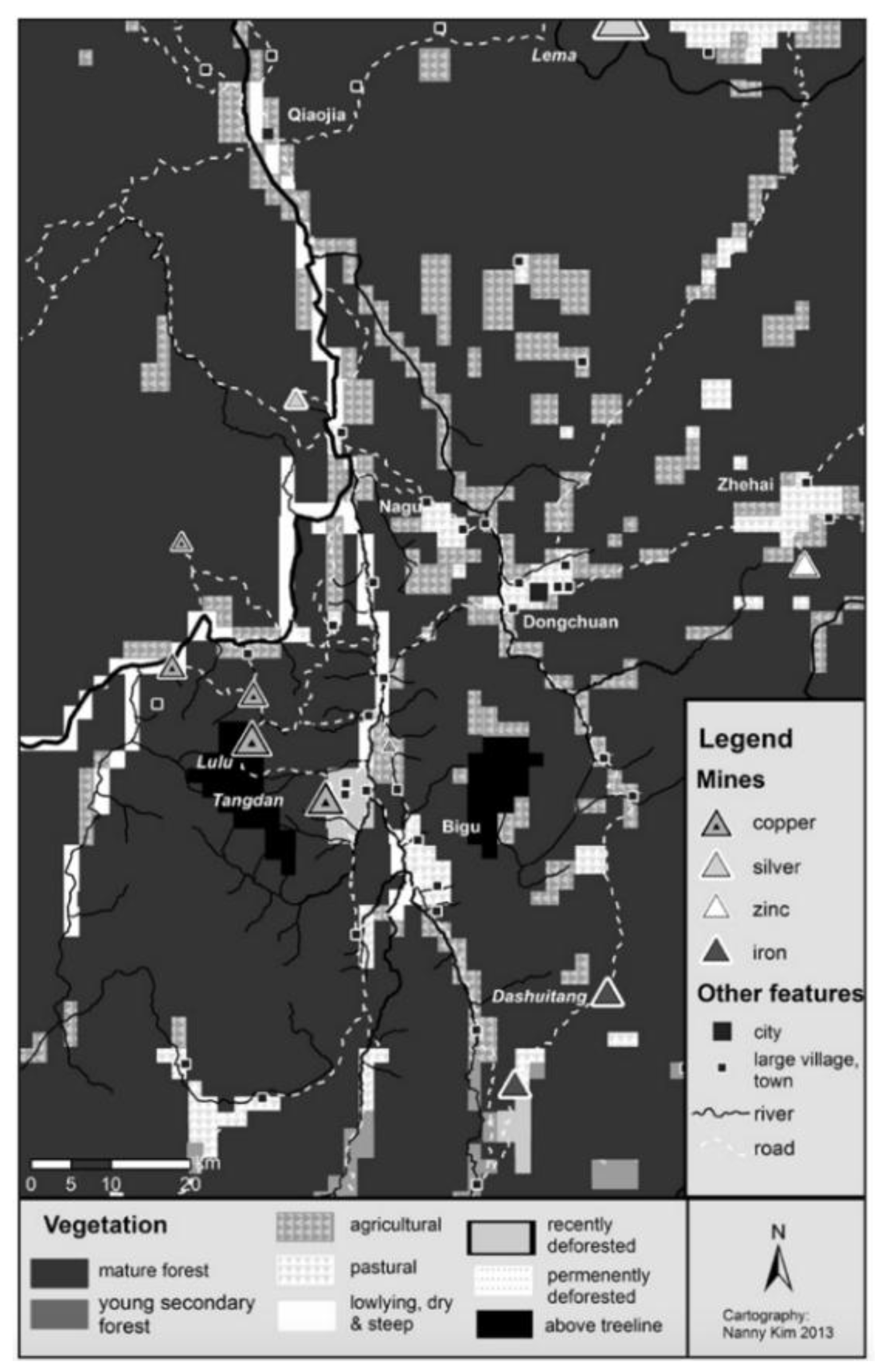

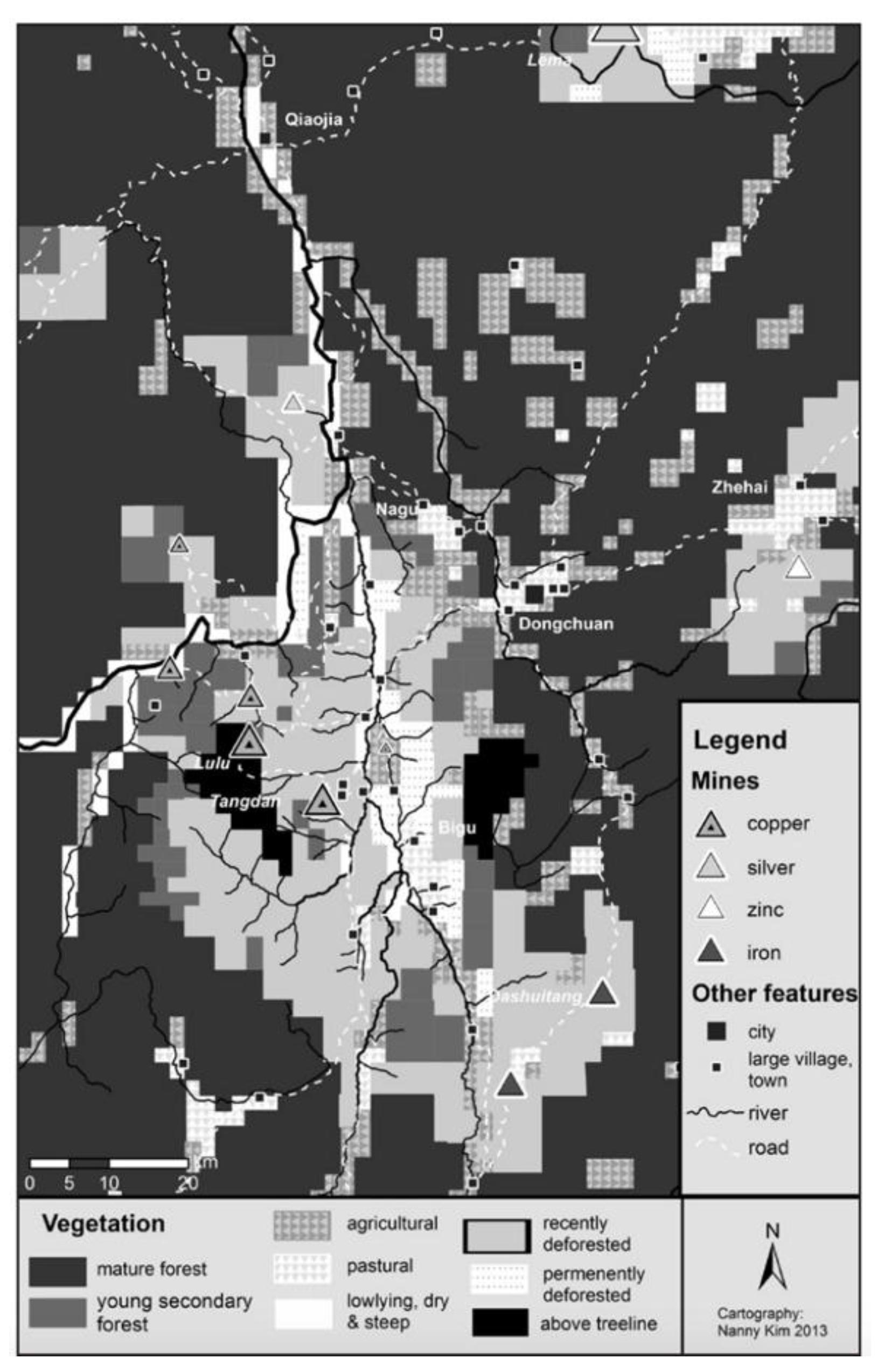

- Braun, A., Rosner, H. J., Hagensieker, R., & Dieball, S. (2015). Multi-method dynamical reconstruction of the ecological impact of copper mining on Chinese historical landscapes. Ecological Modelling, 303, 50. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Ye, Y., Fang, X., & Liu, Y. (2022). Reconstruction of agriculture-driven deforestation in western Hunan Province of China during the 18th century. Land, 11(2), 12. [CrossRef]

- Braun, A., Rosner, H. J., Hagensieker, R., & Dieball, S. (2015). Multi-method dynamical reconstruction of the ecological impact of copper mining on Chinese historical landscapes. Ecological Modelling, 303, 50. [CrossRef]

- Braun, A., Rosner, H. J., Hagensieker, R., & Dieball, S. (2015). Multi-method dynamical reconstruction of the ecological impact of copper mining on Chinese historical landscapes. Ecological Modelling, 303, 50. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. (2018). Fuel for the smelters: Copper mining and deforestation in northeastern Yunnan during the high Qing, 1700 to 1850. In Southwest China in a regional and global perspective (c. 1600–1911) (pp. 112, 118). Brill.

- Kim, N. (2018). Fuel for the smelters: Copper mining and deforestation in northeastern Yunnan during the high Qing, 1700 to 1850. In Southwest China in a regional and global perspective (c. 1600–1911) (pp. 112, 118). Brill.

- Kim, N. (2018). Fuel for the smelters: Copper mining and deforestation in northeastern Yunnan during the high Qing, 1700 to 1850. In Southwest China in a regional and global perspective (c. 1600–1911) (pp. 112, 118). Brill.

- Kim, N. (2018). Fuel for the smelters: Copper mining and deforestation in northeastern Yunnan during the high Qing, 1700 to 1850. In Southwest China in a regional and global perspective (c. 1600–1911) (p. 101). Brill..

- Dearing, J. A., Jones, R. T., Shen, J., Yang, X., Boyle, J. F., Foster, G. C., ... & Elvin, M. J. D. (2008). Using multiple archives to understand past and present climate–human–environment interactions: The lake Erhai catchment, Yunnan Province, China. Journal of Paleolimnology, 40(1), 24–25.

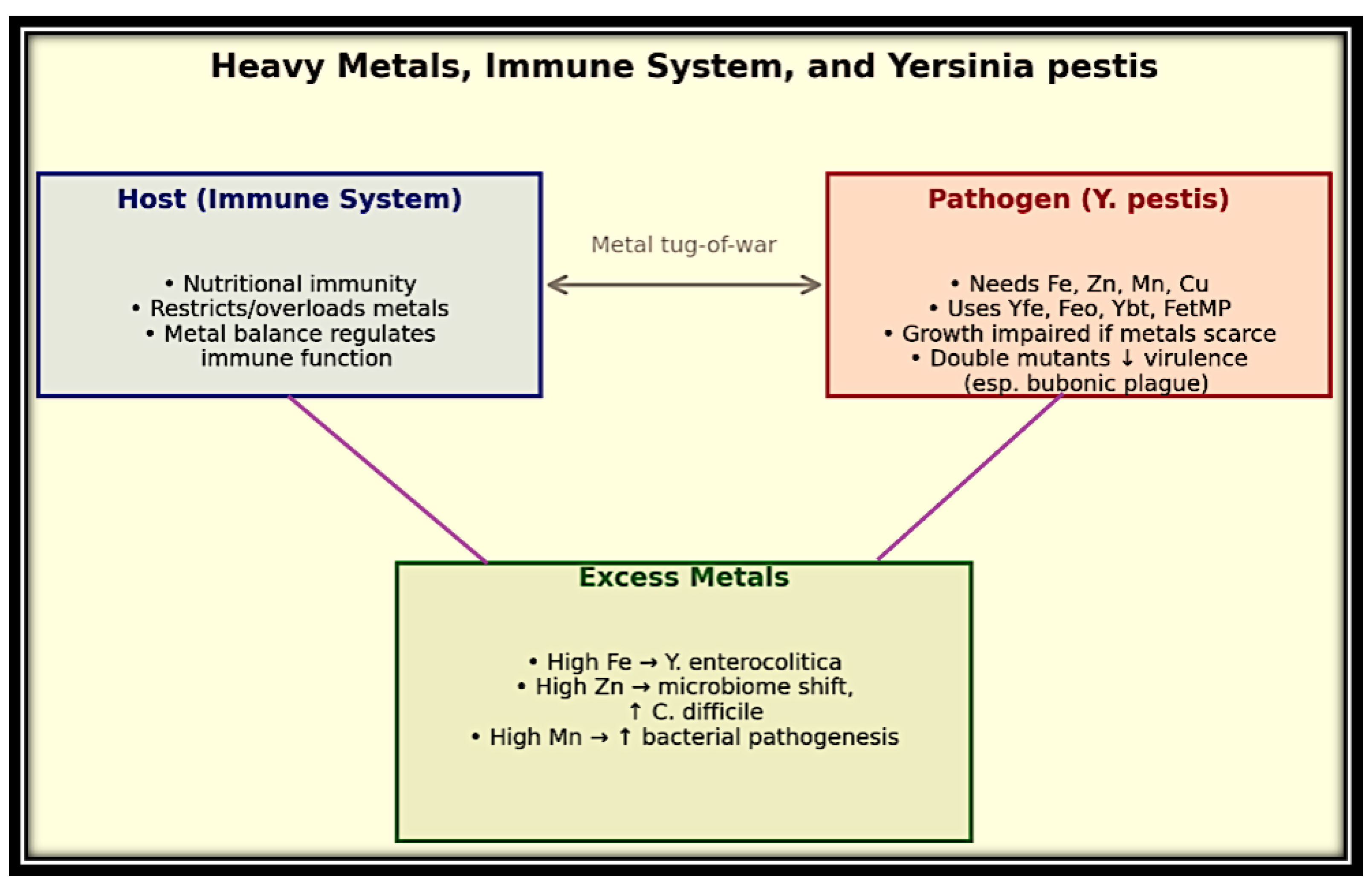

- Li, K., Liu, E., Zhang, E., Li, Y., Shen, J., & Liu, X. (2017). Historical variations of atmospheric trace metal pollution in Southwest China: Reconstruction from a 150-year lacustrine sediment record in the Erhai Lake. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 172, 67.

- Li, K., Liu, E., Zhang, E., Li, Y., Shen, J., & Liu, X. (2017). Historical variations of atmospheric trace metal pollution in Southwest China: Reconstruction from a 150-year lacustrine sediment record in the Erhai Lake. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 172, 67.

- Liu, P., Liu, F., Li, G., Li, Y., Cao, H., & Li, X. (2024). Anthropogenic impact on the terrestrial environment in the Lake Dian Basin, Southwestern China during the Bronze Age and Ming–Qing period. Land, 13(2), 8.

- Hillman, A. L., Yu, J., Abbott, M. B., Cooke, C. A., Bain, D. J., & Steinman, B. A. (2014). Rapid environmental change during dynastic transitions in Yunnan Province, China. Quaternary Science Reviews, 98, 30.

- Zhang, X., Hu, M., Guo, X., Yang, H., Zhang, Z., & Zhang, K. (2018). Effects of topographic factors on runoff and soil loss in Southwest China. Catena, 160, 401.

- Li, B., Deng, J., Li, Z., Chen, J., Zhan, F., He, Y., ... & Li, Y. (2022). Contamination and health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil and ditch sediments in long-term mine wastes area. Toxics, 10(10), 607.

- Zhang, X., Yang, L., Li, Y., Li, H., Wang, W., & Ye, B. (2012). Impacts of lead/zinc mining and smelting on the environment and human health in China. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 184(4), 2261–2273.

- Lai, L., Li, B., Li, Z. R., He, Y. M., Hu, W. Y., Zu, Y. Q., & Zhan, F. D. (2022). Pollution and health risk assessment of heavy metals in farmlands and vegetables surrounding a lead-zinc mine in Yunnan province, China. Soil and Sediment Contamination: An International Journal, 31(4), 483–497.

- Yang, Y., Pan, M., Lin, Y., Xu, H., Wei, S., Zhang, C., ... & Niu, B. (2025). Assessing heavy metal risks in liquid milk: Dietary exposure and carcinogenicity in China. Journal of Dairy Science.

- Yang, Y., Pan, M., Lin, Y., Xu, H., Wei, S., Zhang, C., ... & Niu, B. (2025). Assessing heavy metal risks in liquid milk: Dietary exposure and carcinogenicity in China. Journal of Dairy Science, 6838.

- Deng, L., Yin, M., Yang, S., Wang, X., Chen, J., Miao, D., ... & Ren, Z. (2025). Assessment of metal residues in soil and evaluate the plant accumulation in copper mine tailings of Dongchuan, Southwest China. Frontiers in Plant Science, 16, 13.

- Zhang, H., Wang, J., Zhang, K., Shi, J., Gao, Y., Zheng, J., ... & Li, H. (2024). Association between heavy metals exposure and persistent infections: The mediating role of immune function. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1367644.

- Zauberman, A., Vagima, Y., Tidhar, A., Aftalion, M., Gur, D., Rotem, S., ... & Mamroud, E. (2017). Host iron nutritional immunity induced by a live Yersinia pestis vaccine strain is associated with immediate protection against plague. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 7, 277.

- Demeure, C. E., Dussurget, O., Mas Fiol, G., Le Guern, A. S., Savin, C., & Pizarro-Cerdá, J. (2019). Yersinia pestis and plague: An updated view on evolution, virulence determinants, immune subversion, vaccination, and diagnostics. Microbes and Infection, 21(5), 205.

- Murdoch, C. C., & Skaar, E. P. (2022). Nutritional immunity: The battle for nutrient metals at the host–pathogen interface. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 20(11), 659–670.

- Ellwanger, J. H., Ziliotto, M., & Chies, J. A. B. (2025). Impacts of metals on infectious diseases in wildlife and zoonotic spillover. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(4), 105.

- Yang, R., Wu, D., Li, Z., Yuan, Z., Niu, L., Zhang, H., ... & Zhou, A. (2022). Holocene–Anthropocene transition in northwestern Yunnan revealed by records of soil erosion and trace metal pollution from the sediments of Lake Jian, southwestern China. Journal of Paleolimnology, 68(1), 95–112.

- Pareja-Carrera, J., Martinez-Haro, M., Mateo, R., & Rodríguez-Estival, J. (2021). Effect of mineral supplementation on lead bioavailability and toxicity biomarkers in sheep exposed to mining pollution. Environmental Research, 196, 110364.

- Imperial Maritime Customs. (1890). Medical reports for the half-year ended 30th September 1889 (Customs Gazette No. 31). Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs, 40–42.

- Gejiu Subprefecture Local History Office (Ed.). (1993). Gazetteer of Gejiu Subprefecture (Vol. 3, p. 105) [《个旧厅志》卷三·食货志]. Kunming: Yunnan University Press. (In Chinese).

- Chuxiong Prefecture Cultural Bureau (Ed.). (1996). Kangxi Gazetteer of Guangtong Department (Vol. 4, p. 59) [《康熙广通州志》卷四·赋役志]. Chuxiong: Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture Cultural Bureau. (In Chinese).

- Cao, J. (2019). The last copper century: Southwest China and the coin economy (1705–1808). Asian Review of World Histories, 7(1–2), 126–146. [CrossRef]

- Von Glahn, R. (2016). The economic history of China: From antiquity to the nineteenth century. Cambridge University Press.

- Ben-Ari, T., Neerinckx, S., Agier, L., Cazelles, B., Xu, L., Zhang, Z., ... & Stenseth, N. C. (2012). Identification of Chinese plague foci from long-term epidemiological data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(21), 8200. [CrossRef]

- Chuxiong Prefecture Magistrate’s Office. (1891). Gazetteer of Chuxiong Prefecture (Vol. 13) [楚雄府志, Guangxu 17, section “Phenology”]. Chuxiong: Chuxiong Prefectural Printing Bureau.

- Imperial Maritime Customs. (1888). *Medical report for the half-year ended 30th June 1888*. Yunnan Station.

- Rosner, H.-J., Dieball, S., & Specht, R. (2008). Reconstruction of copper transportation routes in Qing China—A multi-source approach. In T. Hirzel & N. Kimm (Eds.), Metals, monies, and marks in early modern societies: East Asian and global perspectives (pp. 237–254). LIT Verlag.

- Benedict, C. (1992). Bubonic plague in nineteenth-century China [Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.p.84.

- Liang, Y., Zhao, X., Chen, F., Yang, Y., & Ljungqvist, F. C. (2025). Winter-spring drought in Yunnan since the early 19th century and its impact on social governance in China’s southwestern border regions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., Li, Q., Fang, X., Sun, Y., Li, D., & Cao, Y. (2008). Effects of surrounding vegetable fields on the indoor capture of Rattus flavipectus in rural households of Yunnan Province. Chinese Journal of Vector Biology and Control, 19(5), 463.

- Huang, F. (2012). Settlement and ethnic interaction in the southwestern Bazi basins. In K. Hammond (Ed.), China’s march toward the tropics: A study of southward expansion (pp. 67–89). White Lotus Press, 78-80.

- Vogel, H. U. (2018). Fuel for the smelters: Copper mining and deforestation in northeastern Yunnan during the High Qing, 1700–1850. In F. Guo & C. Lin (Eds.), Southwest China in a regional and transnational perspective Brill,.112–134.

- Dai, Jingsun [戴絅孫], comp. Kunming Xianzhi [昆明縣志; Kunming County Gazetteer]; Guangxu 27 (1901) woodblock ed.; Juan 3, “Wuchan zhi” [物產志]. National Library of China scan, Wikimedia Commons. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/01/NLC403-312001086725-82770_%E6%98%86%E6%98%8E%E7%B8%A3%E8%AA%8C_%E6%B8%85%E5%85%89%E7%B7%9227%E5%B9%B4%281901%29_%E5%8D%B7%E4%B8%89.pdf (accessed on 20 Oct 2025). (In Chinese).

- https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/surveillance-and-management-of-common-structure-invading-rats#:~:text=Fecal%20evidence:%20Rats%20are%20able,infection%20with%20rodent%2Dborne%20disease.

- Horizon Pest Control. (n.d.). Recognizing the odors of a rodent infestation. Retrieved October 25, 2024, from https://horizonpestcontrol.com/recognizing-the-odors-of-a-rodent-infestation/.

- Begon, M., Davis, S., Laudisoit, A., Leirs, H., & Reijniers, J. (2019). Sylvatic plague in Central Asia: A case study of abundance thresholds. In Wildlife disease ecology: linking theory to data and application (pp. 623-643).

- Chuxiong Prefecture Magistrate’s Office. (1891). Gazetteer of Chuxiong Prefecture (Vol. 13, “Phenology” section). [《楚雄府志》卷十三《物候志》, 光绪十七年]. Archival local gazetteer, unpublished print. (In Chinese).

- National Pest Management Association & Ostrapp, D. (n.d.). Surveillance and management of common structure-invading rats. NC State Extension Publications. Retrieved October 25, 2024, https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/surveillance-and-management-of-common-structure-invading-rats.

- Horizon Pest Control. (n.d.). Recognizing the odors of a rodent infestation. Retrieved October 25, 2024, from https://horizonpestcontrol.com/recognizing-the-odors-of-a-rodent-infestation/.

- Arakawa, H., Arakawa, K., & Deak, T. (2010). Sickness-related odor communication signals as determinants of social behavior in rat: a role for inflammatory processes. Hormones and behavior, 57(3), 330-341. Sickness-related odor communication signals as determinants of social behavior in rat: A role for inflammatory processes.

- Shiping Prefecture Magistrate’s Office. (c. 1880s). Gazetteer of Shiping Prefecture (Vol. 9, “Disasters and Anomalies” section). [《石屏州志》卷九《灾异》]. Archival local gazetteer, unpublished print. (In Chinese).

- Zhaotong Prefecture Magistrate’s Office. (1878). Gazetteer of Zhaotong Prefecture (Vol. X, relevant disaster section). [《昭通府志》, 光绪四年或前后]. Archival local gazetteer, unpublished print. (In Chinese).

- Huize Prefecture Magistrate’s Office. (1888). Gazetteer of Huize Prefecture (Vol. 12, “Disasters and Anomalies” section). 《会泽州志》卷十二《灾异》. Archival local gazetteer. (In Chinese).

- Andrianaivoarimanana, V., Kreppel, K., Elissa, N., Duplantier, J. M., Carniel, E., Rajerison, M., & Jambou, R. (2013). Understanding the persistence of plague foci in Madagascar. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 7(11), e2382.

- Andrianaivoarimanana, V., Rajerison, M., & Jambou, R. (2018). Exposure to Yersinia pestis increases resistance to plague in black rats and modulates transmission in Madagascar. BMC research notes, 11(1), 898.

- Tollenaere, C., Rahalison, L., Ranjalahy, M., Duplantier, J. M., Rahelinirina, S., Telfer, S., & Brouat, C. (2010). Susceptibility to Yersinia pestis experimental infection in wild Rattus rattus, reservoir of plague in Madagascar. EcoHealth, 7(2), 242-247.

- Andrianaivoarimanana, V., Telfer, S., Rajerison, M., Ranjalahy, M. A., Andriamiarimanana, F., Rahaingosoamamitiana, C., ... & Jambou, R. (2012). Immune responses to plague infection in wild Rattus rattus, in Madagascar: a role in foci persistence? PLoS One, 7(6), e38630.

- Hagai, T., Chen, X., Miragaia, R. J., Rostom, R., Gomes, T., Kunowska, N., ... & Teichmann, S. A. (2018). Gene expression variability across cells and species shapes innate immunity. Nature, 563(7730), 197-202.

- Zhaotong Prefecture Magistrate’s Office. (1891). Gazetteer of Zhaotong Prefecture (Vol. 14, “Disasters and Anomalies” section). 《昭通府志》卷十四《灾异》. Archival local gazetteer. (In Chinese).

- Luoping County Magistrate’s Office. (1877). Gazetteer of Luoping County (Vol. 7, “Disasters” section). 《罗平县志》卷七《灾异》. Archival local gazetteer. (In Chinese).

- Andrianaivoarimanana, V., Telfer, S., Rajerison, M., Ranjalahy, M. A., Andriamiarimanana, F., Rahaingosoamamitiana, C., ... & Jambou, R. (2012). Immune responses to plague infection in wild Rattus rattus, in Madagascar: a role in foci persistence? PLoS One, 7(6), e38630.

- Andrianaivoarimanana, V., Kreppel, K., Elissa, N., Duplantier, J. M., Carniel, E., Rajerison, M., & Jambou, R. (2013). Understanding the persistence of plague foci in Madagascar. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 7(11), e2382.

- Andrianaivoarimanana, V., Rajerison, M., & Jambou, R. (2018). Exposure to Yersinia pestis increases resistance to plague in black rats and modulates transmission in Madagascar. BMC research notes, 11(1), 898.

- Tollenaere, C., Rahalison, L., Ranjalahy, M., Duplantier, J. M., Rahelinirina, S., Telfer, S., & Brouat, C. (2010). Susceptibility to Yersinia pestis experimental infection in wild Rattus rattus, reservoir of plague in Madagascar. EcoHealth, 7(2), 242-247.

- Translated from French from: Rocher, É. (1879-80). La Province chinoise du Yunnan; Librairie de la Société asiatique de l’École des langues orientales vivantes: Paris, France, Vol. 1, 221. “Au moment de notre passage, le village était entièrement désert, les habitants avaient fui leurs demeures pour aller camper sur les hauteurs, abandonnant leurs récoltes sur pied, afin d’éviter les atteintes d’un ennemi plus impitoyable que les rebelles, la peste.”.

- Li, Y. S. (李玉尚). (2002). 近代中国的鼠疫应对机制——以云南、广东和福建为例 [The response mechanism to plague in modern China: The cases of Yunnan, Guangdong and Fujian]. Southeast Asian Studies, (01), 114–127, 192.

- Li, Y. S., & Cao, S. J. (李玉尚 & 曹树基). (2003). 咸同年间的鼠疫流行与云南人口的死亡 [Plague spread and mortality in Yunnan during the Xian-Tong period]. Qing History Studies (清史研究), (4), 88–100.

- Xu, X. M. (许新民). (2010). 近代云南瘟疫流行考述 [A study of plague epidemics in modern Yunnan]. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University (Social Sciences), 11, 121–126.

- Hu, D. (胡蝶). (2014). 清代云南省疫灾地理规律与环境机理研究 [Geographical laws and environmental mechanisms of epidemics in Yunnan during the Qing] [Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University].

- Gazetteer of Tengyue Subprefecture (《腾越州志》), vol. 6. Entry from the end of the Daoguang reign (c.1845–1850).

- Tengyue Subprefecture Magistrate’s Office. (ca. 1845–1850). Gazetteer of Tengyue Subprefecture (Vol. 6). 《腾越州志》卷六,道光末年记载 [Tengyue Gazetteer, Vol. 6, late Daoguang reign entry].

- Yongshan County Magistrate’s Office. (ca. 1885). Gazetteer of Yongshan County (Vol. 6). 永善县志卷六《风俗医药》 [Customs and Medicine section, Guangxu period].

- Yongshan County Gazetteer Editorial Office. (ca. 1885). Gazetteer of Yongshan County (Vol. 6). 永善县志卷六《风俗医药》 [Customs and Medicine section, Guangxu period].

- Platt, S. R. (2012). Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the epic story of the Taiping Civil War. Knopf.

- Davis, B. C. (2017). Opium and rebellion at high altitudes. In Imperial bandits: Outlaws and rebels in the China-Vietnam borderlands (pp. 22–49). University of Washington Press.

- Davis, B. C. (2017). Opium and rebellion at high altitudes. In Imperial bandits: Outlaws and rebels in the China-Vietnam borderlands (pp. 22–49). University of Washington Press.

- Lee, H. F., & Zhang, D. D. (2013). A tale of two population crises in recent Chinese history. Climatic Change, 116(2), 292, 295-6.

- Laybourn-Langton, L., & Hill, T. (2019). Facing the crisis: Rethinking economics for the age of environmental breakdown, 4.

- McMahon, B. J., Morand, S., & Gray, J. S. (2018). Ecosystem change and zoonoses in the Anthropocene. Zoonoses and Public Health, 65(7), 755-765.

- Orlandi, G., Hoyer, D., Zhao, H., Bennett, J. S., Benam, M., Kohn, K., & Turchin, P. (2023). Structural-demographic analysis of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) collapse in China. Plos one, 18(8), 1.

- See also: Maddison, A. (2003). The world economy: Historical statistics. OECD Publishing: . [CrossRef]

- Benedict, C. (1988). Bubonic plague in nineteenth-century China. Modern China, 14(2), 107-155.

- Bitton, M. (2022). Taiping Heavenly Kingdom map [Map]. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved [October 2025], https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/23/Taiping_Heavenly_Kingdom_map.svg.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).