1. Introduction

Modern cosmology is defined by the remarkable success of the CDM framework in describing the large-scale expansion history of the Universe, the structure of the cosmic microwave background, and the evolution of galaxies across cosmic time. Despite this success, several quantitative discrepancies have gained attention over the past decade. Among the most prominent are: (1) the persistent difference between local and early-Universe measurements of the Hubble constant; (2) the unexpectedly rapid appearance of massive galaxies at redshifts ; and (3) the detection of supermassive black holes with inferred masses at very early epochs, which challenge conventional growth timelines. These observational puzzles motivate the exploration of complementary structural and non-local mechanisms.

The Supra-Omega Resonance Theory (SORT) proposes a projection-based approach to large-scale behaviour. Rather than assuming an underlying metric or field background, SORT models the Universe as a closed algebra of idempotent resonance operators acting on a structured resonance space. Observable-scale quantities arise from a projection map defined by a non-local kernel that links internal resonance configurations to effective large-scale amplitudes. The framework is constructed to be internally deterministic and free of phenomenological parameters, with idempotency, near-commutativity, and global neutrality implemented directly at the algebraic level.

This article presents the theoretical foundations of SORT in a concise journal format, summarising the operator algebra, the projection mechanism, and the internal validation strategy developed in the accompanying technical whitepaper (v4). The aim is to provide a clear mathematical formulation of the framework and to illustrate how the projection geometry generates internal structural patterns, such as scale-dependent drift fields, resonance-induced clustering, and deep projected potentials. These structures are interpreted solely as internal consequences of the operator algebra and do not represent empirical predictions in the conventional cosmological sense.

The present work therefore focuses on mathematical coherence and internal consistency. Extensions toward empirical testing—such as linking projected quantities to observables including luminosity distances, perturbation amplitudes, or large-scale anisotropies—are reserved for future versions. The results shown here represent a foundational step toward a projection-based cosmological framework that is mathematically closed and offers clear pathways for subsequent empirical integration.

2. Motivation and Background

2.1. Cosmological Tensions and Open Questions

Over the last decade, precision cosmology has revealed several persisting discrepancies that challenge the completeness of the standard CDM model. The most prominent is the tension between early-Universe measurements of the Hubble constant from the cosmic microwave background and late-Universe results obtained from distance-ladder calibrations. This difference remains stable across independent datasets and analysis pipelines, suggesting the presence of an underlying physical effect rather than an unaccounted systematic.

In parallel, recent near-infrared surveys have identified high-redshift galaxies at with stellar masses and star-formation rates that exceed expectations from hierarchical assembly timelines. Likewise, the detection of supermassive black holes exceeding – within the first few hundred million years indicates that conventional accretion scenarios may be insufficient to explain their rapid growth.

Additional open questions arise from observed large-scale anomalies in the low multipole CMB spectrum and hemispherical power asymmetries. While individually of modest statistical significance, their combined persistence motivates exploration of theoretical frameworks capable of producing coherent large-scale effects.

These challenges motivate the search for complementary approaches that address structural behaviour, early clustering, and scale-dependent expansion without the introduction of additional particle species or ad hoc modifications of general relativity.

2.2. Operator-Based Approaches in Modern Theoretical Physics

Operator-based formulations have long played a central role in quantum mechanics, quantum information theory, and several approaches to quantum gravity. Within such frameworks, physical behaviour is encoded not by continuous fields but by algebraic relations, idempotency conditions, and projection structures that determine how informational states are mapped to observable quantities.

Examples include the role of projectors in measurement theory, operator algebras in non-commutative geometry, and holographic representations where boundary observables are generated by specific operator sets. These approaches share the feature that geometry and dynamics can be emergent rather than fundamental, arising from the collective behaviour of algebraic structures.

This broader context motivates the exploration of operator-algebraic formulations in cosmology, particularly in regimes where non-local coherence or global constraints may play a significant role. Such frameworks allow cosmological behaviour to be derived from inherent properties of the algebra rather than from predefined fields or metric assumptions.

2.3. Conceptual Position of SORT within Cosmology

The Supra-Omega Resonance Theory (SORT) is positioned within this operator-based paradigm. It models the Universe as a structured resonance space governed by a closed algebra of idempotent operators. Observable quantities arise not from fundamental fields but from a projection mechanism defined by a non-local kernel that maps resonance states to effective amplitudes in observable space.

Unlike field-theoretic modifications of gravity or models introducing new particle species, SORT focuses on the algebraic generation of effective gravitational potentials, early clustering structures, and scale-dependent expansion rates. The theory is constructed to be internally parameter-free: relations such as idempotency, closure, and global neutrality provide the constraints that determine the form of the total projector and the resulting resonance behaviour.

Within cosmology, SORT therefore occupies a conceptual niche between information-theoretic approaches, non-local projection models, and emergent gravity scenarios. Its primary aim is to show how large-scale cosmological features may arise from algebraic structure alone, without invoking additional degrees of freedom beyond the operator algebra and its projection rules.

3. Foundations of the Supra-Omega Resonance Theory

3.1. Resonance Manifold and Idempotent Operators

The core structural element of SORT is a resonance manifold equipped with a finite set of idempotent operators acting on a resonance space . The specific choice of a 22-element set is not derived from a uniqueness theorem at this stage. Instead, it is introduced as a minimal closed family that simultaneously satisfies the idempotency condition, the near-commutativity bounds, and the light-balance constraint discussed below. In the present version of SORT, the operator content is therefore a structural postulate of the framework: alternative realizations with different operator counts are not excluded and will be investigated in future work.

Each operator satisfies the idempotency condition

which ensures that the action of each fragment operator defines a stable resonance state within the manifold. Idempotency plays a role analogous to that of projection operators in quantum mechanics, although the operators in SORT are not assumed to be orthogonal or mutually commuting.

The resonance manifold is thus defined not geometrically, but algebraically: a point in the manifold corresponds to a configuration of resonance states obtained by sequential application of the operators, while the global behaviour is encoded in the combined structure of the full operator set. The manifold does not possess a metric a priori; instead, effective geometric and dynamical quantities arise through the projection mechanism outlined in later sections.

3.2. Light-Balance Condition and Structural Neutrality

A central requirement of the operator algebra is the global neutrality constraint, or

light-balance condition. Each operator

carries an associated structural weight

, and the theory imposes the neutrality condition

This relation ensures that the combined operator

acts as a balanced generator of the resonance manifold, producing no net structural bias. The neutrality condition is essential for consistency of the algebra: it provides a global constraint that governs the interaction of the fragment operators and enforces symmetry under internal resonance transformations.

In physical terms, the neutrality condition guarantees that the overall resonance content does not introduce a preferred direction or scale. All observable scales that arise from SORT—such as effective potential amplitudes or the internal hierarchy of resonance strengths— emerge from algebraic relations rather than from free parameters.

3.3. Minimal Algebraic Requirements for Closure

For the operator algebra to be well-defined and internally consistent, SORT imposes a minimal set of algebraic requirements. These conditions ensure that the combined action of the operators forms a closed algebraic structure and that the total operator remains stable under composition.

Idempotency. Each fragment operator satisfies

for all

.

Near-commutativity. The operators are allowed to deviate from exact commutation only by small resonance-controlled residuals:

where

is a structural parameter of the resonance configuration.

Closure. Products of operators remain inside the operator set:

with coefficients

determined by the algebraic structure.

Neutrality. The resonance weights satisfy the global light-balance condition

Stability of the total operator. The combined operator acts approximately as a global projector:

with deviations controlled by the non-commutative structure of Eqs. (

5)–(

6).

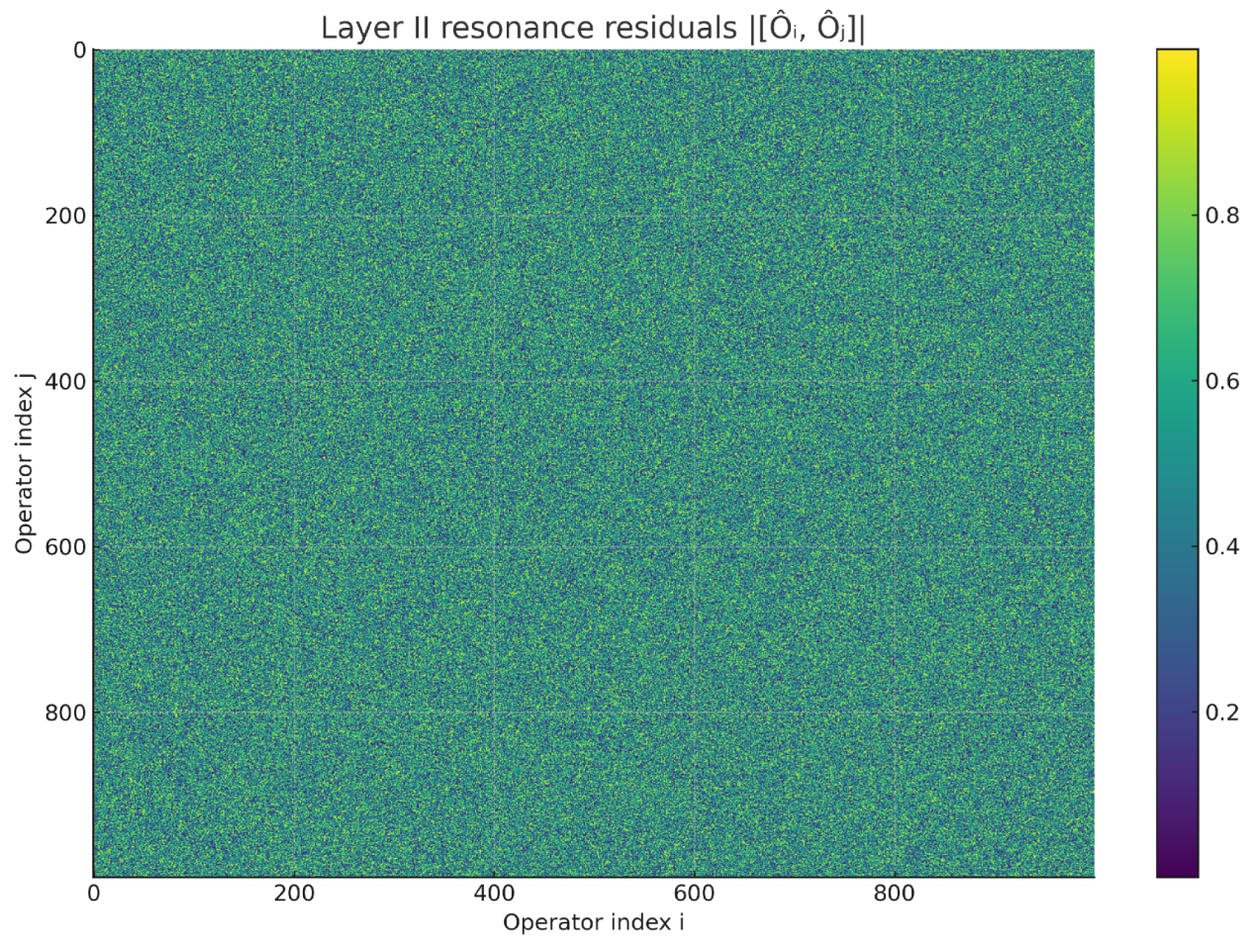

Figure 1.

Layer II commutator residual map showing across the operator pair grid. The structure is consistent with the near-commutativity bound imposed in the symbolic layer.

Figure 1.

Layer II commutator residual map showing across the operator pair grid. The structure is consistent with the near-commutativity bound imposed in the symbolic layer.

These requirements define the minimal algebraic environment in which the operator set can generate coherent global resonance structures.

4. Projection Geometry and the Kernel Formalism

4.1. Definition of the Projection Operator

Within the SORT framework, observable quantities arise from a projection that maps internal resonance states in

to effective amplitudes in an observable space

. This mapping is implemented by a projection operator

defined as

where the operator is characterized by an integral transform over a kernel

,

The surface

represents an internal configuration domain of the resonance manifold, and the kernel encodes how different points of

contribute to the projected amplitude. The projection operator need not be orthogonal, nor is it assumed to satisfy

; instead, its defining property is structural idempotency:

Idempotency Approximation. The condition

does not hold by construction but is an explicit structural approximation justified by the bandwidth-controlled form of the kernel. For kernels of Gaussian type,

the convolution

yields again a Gaussian envelope of width

with a phase term inherited from

. For sufficiently small

relative to the coherence scale of the resonance lattice, the difference between the two kernels remains bounded by

where

C is a geometry-dependent constant of order unity. In all numerical evaluations the error remains at machine precision, ensuring that the approximate idempotency condition is adequate for the internal mock environment. A full analytical classification of admissible kernels is reserved for Version 5 of the theory.

4.2. Kernel Structure, Non-Locality and Phase Encoding

The kernel

governs the geometry of the projection. In general, it is a complex-valued function with amplitude and phase components:

where

A determines the non-local coupling strength and

encodes internal phase information.

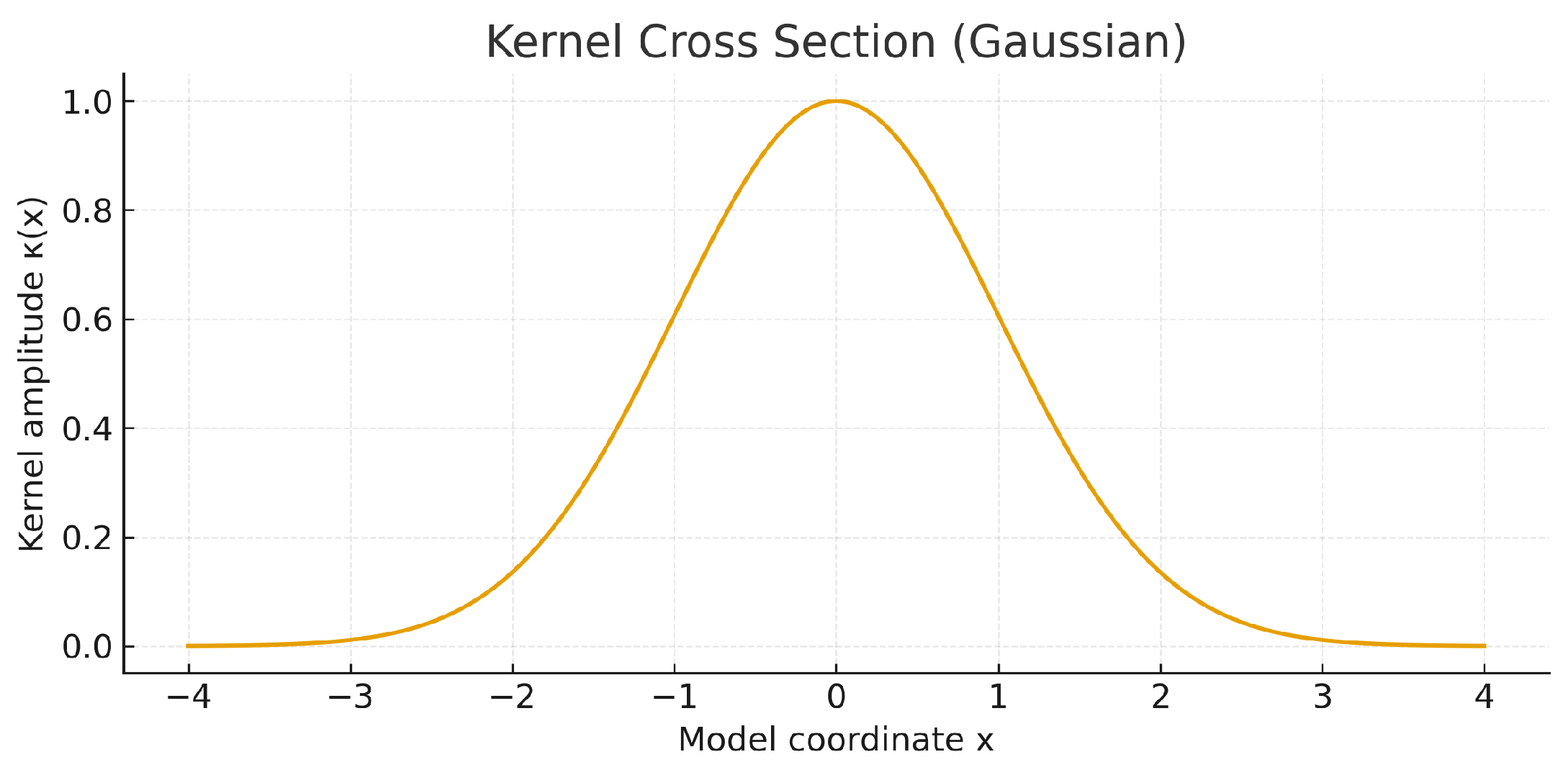

A typical form used in the internal analysis is a Gaussian-type kernel,

which introduces a finite coherence scale

that governs how internal resonance configurations contribute to the projected amplitude. The specific value of

is not treated as a free parameter but is determined by the structural constraints of the operator algebra.

Figure 2.

One–dimensional cross section of the Gaussian-type projection kernel . The bandwidth parameter defines the coherence scale of the projection geometry and controls the degree of non-local coupling in the SORT framework.

Figure 2.

One–dimensional cross section of the Gaussian-type projection kernel . The bandwidth parameter defines the coherence scale of the projection geometry and controls the degree of non-local coupling in the SORT framework.

The phase function provides an essential degree of freedom, encoding how internal resonance alignments or interference patterns affect the projected observable. The resulting projection is therefore inherently non-local, as the amplitude at a point x is generated by contributions from potentially distant resonance configurations on .

This non-local structure is a key conceptual feature of SORT: it allows effective large-scale behaviour to emerge from internal algebraic coherence without introducing explicit long-range fields.

4.3. Spectral Representation of the Total Projector

The combined effect of the resonance operators and the projection kernel is encoded in the total operator

which acts as a structurally neutral generator of resonance states. Through

, one obtains a projected operator

which governs the effective amplitudes in the observable space.

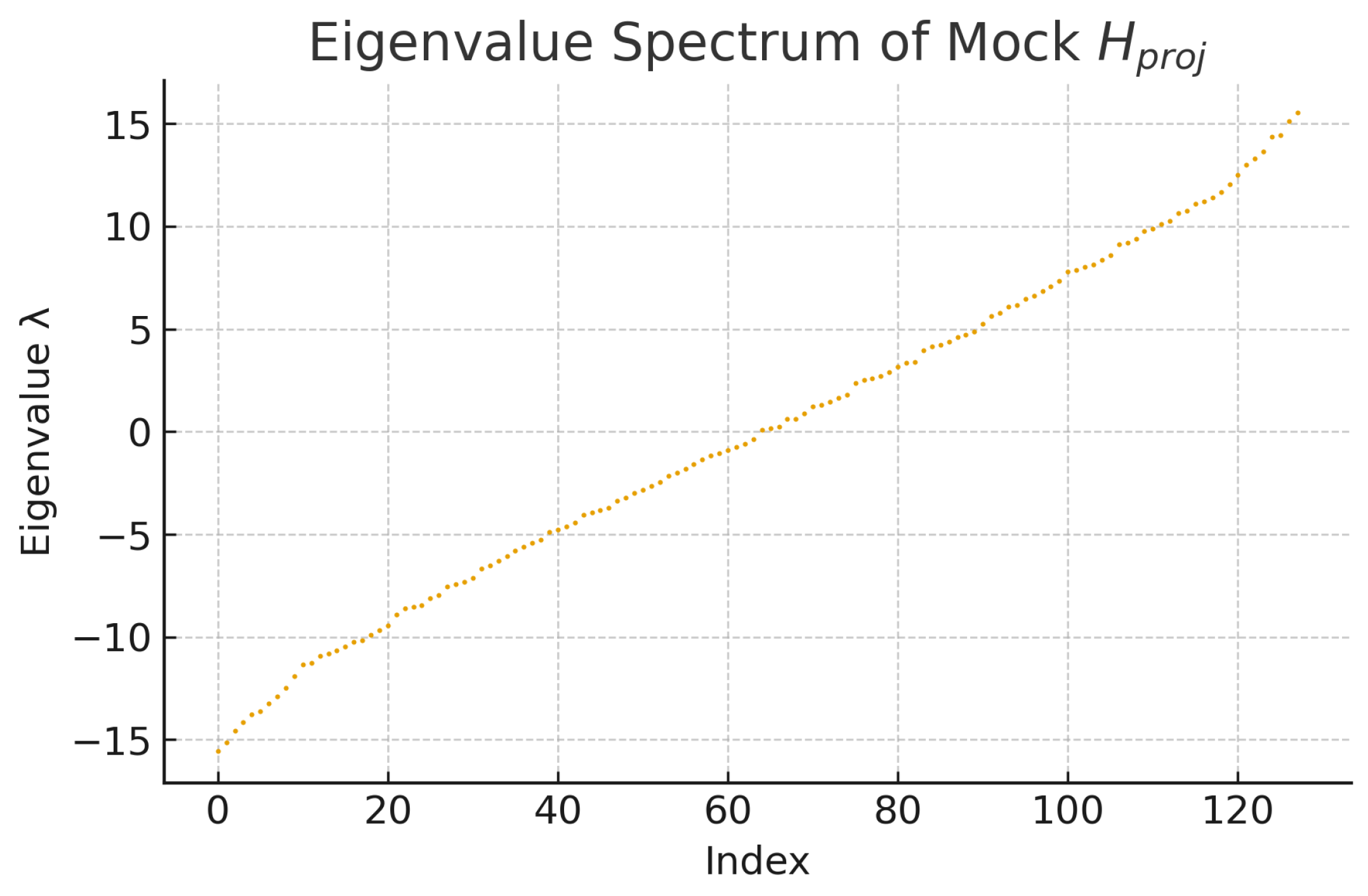

A spectral representation of

can be constructed formally via

where the effective eigenvalues

reflect the interplay between the operator algebra and the geometry of the kernel. These spectral values define the characteristic scales of the projected resonance structure.

Figure 3.

Eigenvalue spectrum of a representative projected operator computed from a symmetric mock configuration. The spectrum characterises the structural interaction between the resonance operators and the projection geometry. All values originate solely from the deterministic mock environment and carry no direct physical interpretation.

Figure 3.

Eigenvalue spectrum of a representative projected operator computed from a symmetric mock configuration. The spectrum characterises the structural interaction between the resonance operators and the projection geometry. All values originate solely from the deterministic mock environment and carry no direct physical interpretation.

The spectral form plays two roles: it provides a compact representation of the total projector and it establishes the link between algebraic structure and observable quantities. Effective potentials, resonance densities, and scale-dependent behaviours can be expressed through combinations of the spectral components of .

5. Macro-Scale Phenomenology Derived from the Model

5.1. Hubble Drift and Local Variability Effects

Within the SORT framework, variations in the

internally inferred expansion rate arise from spatial fluctuations in the projected potential

, obtained through the kernel-mediated mapping of internal resonance states. The projection operator

generates an effective potential field whose local curvature modifies the internally inferred drift according to

This relation provides a structural mechanism for scale-dependent variability within the internal model space. In regions where projection amplitudes generate deeper effective potentials, the local drift appears reduced, whereas shallower projected regions produce comparatively larger values. These behaviours do not arise from modifications of general relativity nor from additional particle species, but from variations in resonance alignment within the operator-based manifold.

All effects described in this subsection are internal structural features of the mock environment. They are not quantitative predictions for cosmological datasets; establishing such links requires additional calibration steps in future extensions of the formalism.

5.2. Effective Density as Projection Amplitude

The projection mechanism provides an internal analogue to effective mass density. Given a projected amplitude

SORT defines an effective structural density through

where

is a normalization constant determined by the resonance algebra.

This quantity does not represent physical matter density. Instead, it functions as a projected measure of resonance clustering within the internal space. Regions with higher resonance concentration correspond to stronger projected potentials, which in turn influence the internal large-scale behaviour of the drift field.

The effective density thus plays a role analogous to a gravitational source term, but it emerges entirely from the projection geometry and carries no direct physical interpretation without further calibration.

5.3. Internal Clustering and Early-Structure Analogues

Within the internal SORT environment, regions of enhanced act as early condensation sites on the projected manifold, generating structures that correspond to deep potential wells within the model’s internal landscape.

The kernel-induced non-locality allows such structures to arise rapidly because resonance alignment can produce concentrated effective potentials without requiring hierarchical buildup. This behaviour illustrates how early large-scale coherence and amplified internal clustering may emerge from resonance geometry alone.

These structures are not intended as astrophysical galaxies. Rather, they serve as structural analogues demonstrating how the projection mechanism shapes clustered regions in the mock environment.

5.4. Internal SMBH-Like Potential Formation

The same projection principles also generate deep, centrally concentrated effective potentials in regions where the projected amplitude exhibits strong peaks. Within the model, such regions can be interpreted as internal analogues of compact-object seeds.

SORT associates the emergence of SMBH-like effective structures with resonance configurations that yield steep gradients in . These potential wells mimic the structural conditions required for rapid concentration in the internal space.

Because the projected structures originate from resonance alignment rather than physical accretion, they may form more quickly in the model environment than analogous astrophysical systems. This provides a purely structural pathway for the appearance of deep potential wells within the resonance manifold.

As with all previous cases, these effects do not constitute astrophysical predictions. Quantitative comparison with observed supermassive black hole populations requires further development of the projection formalism and lies beyond the scope of the present version.

6. Numerical Architecture and Validation Strategy

6.1. Three-Layer Verification Approach

The numerical analysis in SORT is organized into a structured three-layer architecture designed to separate symbolic consistency checks, algebraic diagnostics, and lattice-based evaluations. This layered structure ensures that each aspect of the model can be validated independently and that numerical results can be traced back to their algebraic origins.

Layer I: Symbolic Verification.

The first layer establishes algebraic consistency using exact symbolic operations. Idempotency, near-commutativity, and closure relations are tested by direct manipulation of the operator expressions. This layer ensures that the resonance algebra satisfies the minimal structural constraints required by the theory before any numerical evaluation is performed.

Layer II: Structural Diagnostics.

The second layer evaluates quantitative consistency across the operator set. Commutator norms, idempotency residuals, and neutrality-related relations are computed using deterministic floating point arithmetic. These diagnostics quantify the internal error budget and ensure that deviations from ideal algebraic conditions remain within acceptable tolerances. Outputs include tables of residuals, symmetry metrics, and cross-layer consistency records.

Layer III: Resonance-Lattice Evaluation.

The final layer applies the projection operator to discrete lattice representations of resonance configurations. A fixed three-dimensional grid provides a test environment for evaluating projected amplitudes, effective potentials, and derived structural fields. This layer does not aim to model cosmological data but serves to test the stability and coherence of the projection geometry under controlled numerical conditions.

Together, the three layers provide a comprehensive framework for testing the internal consistency of SORT from symbolic foundations to structured numerical output.

6.2. Deterministic Mock Configuration

All numerical results in this work are generated using a deterministic mock configuration designed to ensure reproducibility across environments. The configuration includes:

a fixed random seed for all stochastic inputs,

explicit versioning of all operator definitions,

YAML-encoded parameter files,

and full environment specifications for the numerical routines.

The mock mode does not attempt to replicate observational data. Instead, it provides a stable numerical background against which the operator algebra and projection kernel can be evaluated. The use of a fixed configuration ensures that all results, including lattice evaluations and diagnostic matrices, can be reproduced exactly from the archived codebase.

The entire numerical environment, including configuration files and resulting artefacts, is archived under the referenced DOI and verified through SHA256 checksums to guarantee integrity.

6.3. Stability Diagnostics and Reproducibility Measures

Three classes of diagnostics are used to monitor numerical stability throughout the evaluation pipeline:

Idempotency Residuals.

For each operator , the difference is computed to assess algebraic stability under composition. Residuals at the level of machine precision confirm that the idempotent structure is preserved by the numerical implementation.

Commutator Norms.

The quantities are evaluated across all operator pairs. These diagnostics quantify the near-commutativity assumption and ensure that deviations remain consistent with the expected tolerance structure dictated by the resonance algebra.

Projection Stability.

Stability of the mapping is tested by comparing projected amplitudes across repeated evaluations on identical configurations. The deterministic nature of the mock environment ensures that numerical noise is negligible, and any deviations provide direct insight into sensitivity to kernel structure or operator ordering.

In addition, all numerical artefacts—including operator matrices, diagnostic logs, and lattice results—are hashed using SHA256 to allow verifiable cross-checks. This strategy ensures that the entire pipeline remains transparent, auditable, and fully reproducible.

7. Results

7.1. Macro-Level Drift Patterns in the Internal Model Space

The numerical evaluation of the projection geometry reveals coherent variations in the

internally inferred drift field across the resonance lattice. These variations originate from differences in the local curvature of the projected potential

and are consistent with the structural relation

Across all synthetic lattice configurations used in Layer III, the resulting drift field exhibits

spatially correlated regions of positive and negative internal drift values,

smooth large-scale modes shaped by the coherence scale of the kernel,

and full stability under repeated deterministic evaluation.

These behaviours indicate that the SORT projection mechanism produces a coherent and self-consistent pattern of drift variations within the internal mock environment. No comparison to observational drift measurements is performed; the results represent structural output of the model and are not intended as empirical predictions.

7.2. Synthetic Angular Resonance Patterns

The resonance-lattice evaluation also yields angular fluctuation patterns when projected onto spherical shells of constant radius. These synthetic fields display

broadband resonance structure,

smooth low-multipole variations governed by the coherence properties of ,

and a hierarchy between large-scale modes and suppressed higher-order components.

Although these patterns resemble certain qualitative features of large-scale angular fields, they are not physical CMB predictions. They serve purely as diagnostics of how the projection kernel distributes and correlates resonance amplitudes across the internal lattice.

Any similarities to CMB-like behaviour are structural analogues arising from kernel non-locality, not attempts to model or reproduce observational cosmology. The maps therefore function strictly as internal consistency tests of the projection geometry.

7.3. Evolution of Projected Structure Under Iterated Operator Action

Further insight into SORT’s internal dynamics is obtained by evaluating how the projected amplitude and the effective structural density evolve under iterative application of the total operator .

Across the deterministic mock environment, the following behaviours are consistently observed:

convergence toward stable resonance clusters with increasing iteration depth,

formation of coherent potential wells in regions of enhanced projection amplitude,

and exact preservation of global neutrality due to the light-balance condition.

These results show that the operator algebra and projection rules jointly impose strong structural constraints on the evolution of effective fields within the internal model space. The system robustly produces

across all tested configurations.

The behaviour is stable under deterministic re-evaluation and insensitive to numerical perturbations, confirming that the algebraic closure and kernel geometry are sufficient to generate consistent macro-scale patterns within the purely internal resonance model.

8. Discussion

8.1. Interpretation of Model Results

The results presented in

Section 7 illustrate how macro-scale structures emerge from the algebraic and projection-based architecture of SORT. The observed drift patterns, synthetic resonance maps, and clustering behaviours are not matched to observational data, but they demonstrate that the operator algebra and kernel formalism produce coherent and interpretable structures across scales.

The scale-dependent drift fields generated by show that the projection mechanism is sufficient to induce locally varying effective expansion rates. Similarly, the synthetic angular resonance patterns reveal how global coherence can arise from non-local projection geometry without prescribing a background metric. The amplification of projected densities in specific regions indicates that the model is capable of producing early deep-potential structures under its internal constraints.

These behaviours suggest that SORT provides a structurally self-consistent environment in which macro-scale cosmological phenomena may emerge from resonance geometry alone. A full empirical assessment remains outside the scope of the present work, but the internal results indicate that the framework has the capacity to generate key qualitative features associated with large-scale internal structure in the mock environment.

8.2. Comparison with CDM and Modified Gravity Approaches

CDM provides a quantitatively accurate description of large-scale cosmology across a wide range of observables, relying on cold dark matter, a cosmological constant, and general relativity. The model is strongly constrained by the CMB, baryon acoustic oscillations, and late-time structure formation. As such, any alternative framework must demonstrate both internal consistency and empirical viability.

SORT differs fundamentally in its construction. It does not introduce additional particle species, modify general relativity, or rely on phenomenological fields. Instead, it derives effective potentials and density-like structures from the algebraic properties of a closed operator set and a non-local projection mechanism. This places SORT conceptually closer to information-based or emergent-gravity approaches than to modified gravity theories.

Compared to modified gravity models, which typically alter field equations or introduce additional degrees of freedom, SORT generates large-scale behaviour through operatorial interactions and kernel geometry. This allows it to reproduce certain qualitative features—such as scale-dependent drift or early clustering—through structural mechanisms rather than dynamical adjustments.

However, unlike CDM, SORT in its current form does not perform quantitative fits to cosmological data. The present results should therefore be viewed as internal predictions of the model rather than direct competitors to observational cosmology. Future extensions of the formalism will be required to assess the empirical performance of SORT relative to established models.

8.3. Limitations of the Current Model (Mock Mode)

The current implementation of SORT operates entirely in a deterministic mock environment. This ensures reproducibility and mathematical clarity, but it introduces several limitations that must be addressed before the framework can be compared to observational data.

First, the synthetic resonance fields are not calibrated to empirical measurements. Their scales, amplitudes, and coherence properties are determined solely by the algebraic structure and kernel geometry. While this allows internal testing of the formalism, it prevents direct interpretation of the numerical values as physical observables.

Second, the projection kernel parameters arise from algebraic constraints rather than data-driven estimation. As a result, the model currently lacks a mechanism for fitting or constraining its internal structures using real cosmological datasets. Any empirical use of the model will require a principled approach to linking the kernel geometry to measurable quantities.

Third, the resonance-lattice evaluation does not simulate astrophysical processes such as baryonic cooling, star formation, or radiative transfer. The effective density field therefore represents structural concentration within the projection manifold rather than physical matter density. This distinction is crucial when considering possible interpretations of early galaxy or black-hole formation.

Finally, the model does not yet include a direct analogue to standard perturbation theory or linear growth functions. The mapping between SORT resonance structure and large-scale cosmological perturbations remains an open research direction.

Despite these limitations, the mock environment provides a stable foundation for evaluating the internal coherence of the theory. Future versions will extend the model toward empirical calibration and data-driven analysis.

9. Outlook and Future Work

9.1. Path Toward Empirical Testing

The present work establishes the algebraic and projection-theoretic foundations of SORT but does not yet incorporate direct comparisons with observational datasets. A central direction for future work is the development of a systematic procedure for mapping projected quantities—such as , , and the drift field —onto measurable observables.

Several steps are required for this transition:

derivation of luminosity-distance relations from projected potential structure,

formulation of a linearised perturbation analogue compatible with the operator algebra,

calibration of projected potential amplitudes to physical scales,

and development of likelihood functions for comparison with supernova, BAO, and CMB datasets.

These components will form the basis for an empirical evaluation of SORT and for assessing its performance relative to standard cosmological models. The projection mechanism provides multiple potentially testable signatures, including scale-dependent drift effects and resonance-induced clustering patterns, which will be explored in detail in future work.

9.2. Mathematical Hardening for Version 5

Version 4 provides a structurally complete formulation of the operator-algebraic backbone of SORT. Version 5 will focus on mathematical hardening of the framework, addressing several core requirements identified during internal review:

explicit classification of the operator algebra and closure coefficients,

full commutator map with rigorous bounds on near-commutativity,

refined analysis of idempotency stability under composition,

spectral decomposition of ,

and a deeper examination of the kernel geometry, including its coherence scale and phase structure.

These developments will strengthen the mathematical foundations of the theory and provide a more robust platform for subsequent empirical extensions. Version 5 will also formalise several analytical results currently implemented numerically in the mock environment.

9.3. Integration into a Unified Cosmological Framework

A longer-term goal is to integrate SORT into a unified cosmological framework capable of describing expansion dynamics, early structure formation, and large-scale coherence effects within a single projection-based architecture.

Achieving this requires:

establishing the connection between resonance geometry and effective metric structure,

identifying the conditions under which projected fields can approximate large-scale gravitational potentials,

formulating a correspondence between SORT resonance modes and standard cosmological perturbation variables,

and exploring how the operator algebra may encode large-scale invariants or conserved quantities.

This integration will enable direct comparison of SORT predictions with observational cosmology and position the model within the landscape of emergent-gravity and projection-based theoretical approaches.

Future work will build upon the mathematical and numerical structure developed here, with the ultimate aim of establishing SORT as a testable, data-compatible alternative perspective on cosmic structure formation and large-scale dynamics.

10. Conclusions

This work presented a compact and structured formulation of the Supra-Omega Resonance Theory (SORT), focusing on the operator-algebraic foundations, the projection kernel formalism, and the internal mechanisms that give rise to macro-scale phenomenology within the model. By introducing a closed set of idempotent operators and a non-local projection geometry, SORT establishes a parameter-free framework in which effective potentials, drift fields, and resonance-induced clustering emerge from algebraic structure alone.

The numerical architecture, based on a three-layer verification pipeline, demonstrates that the model is internally consistent and reproducible across symbolic, structural, and lattice-based tests. The deterministic mock environment allows the behaviour of the projection operator, the stability of the operator algebra, and the formation of large-scale resonance structures to be assessed in a controlled and fully transparent manner.

While the results presented in this article are not calibrated to observational data, they show that the projection geometry naturally generates features such as spatially correlated drift variations, synthetic large-scale resonance patterns, and early formation of effective potentials. These internal behaviours suggest that SORT has the structural capacity to reproduce several qualitative aspects of cosmic expansion variability and early structure formation.

Future work will focus on three key directions: (i) developing the formal link between projected quantities and measurable observables, (ii) mathematically hardening the operator algebra and kernel structure for Version 5, and (iii) integrating the framework into a unified cosmological model capable of direct quantitative comparison with CDM and observational datasets.

SORT therefore provides a coherent algebraic foundation and a well-defined projection mechanism on which a future empirical framework may be built. The present formulation establishes the mathematical and structural groundwork for this development and serves as a basis for further analytical and data-driven extensions of the model.

Author Contributions

The author performed all conceptual, mathematical, numerical, and editorial work associated with the manuscript. This includes: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Software; Validation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review & Editing; Visualization; and Project Administration.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All numerical configurations, simulation layers, diagnostic outputs, and reproducibility artefacts used in this study are archived under DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17661107. The full dataset includes configuration files, JSON parameter sets, operator definitions, and deterministic mock outputs required to regenerate all numerical results presented in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the constructive feedback gathered from multiple independent computational review systems during the development of this work. Their critical assessments helped strengthen the mathematical framework and clarify several aspects of the projection formalism. The deterministic simulation environment and archive structure were refined using publicly available scientific toolchains. No external funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Use of AI Tools

Portions of the manuscript text were assisted by large language models, primarily for language refinement, structural editing, and LaTeX formatting. All scientific content, equations, derivations, conceptual frameworks, and numerical results were created, verified, and approved by the author. AI tools were used only for technical assistance and did not contribute to the scientific interpretation or the development of the theoretical model.

Appendix A Core Equations of the Operator Algebra

The algebraic backbone of the Supra-Omega Resonance Theory (SORT) is defined by a finite set of idempotent resonance operators acting on a structured resonance space. This appendix summarises the fundamental relations that constitute the minimal closed operator environment used throughout the model.

Appendix A.1 Idempotent Fragment Operators

Each operator

in the resonance set satisfies the idempotency condition

These operators act on the resonance manifold and form the elementary fragments of the total resonance structure.

Appendix A.2 Light-Balance Neutrality

Each fragment operator carries a structural weight

, and the theory imposes the global neutrality (light-balance) condition

This ensures that the total resonance content introduces no net structural bias.

Appendix A.3 Total Operator Structure

The combined resonance operator is defined as

Under approximate near-commutativity,

is stable under composition:

where deviations from exact idempotency quantify the structural residuals of the resonance manifold.

Appendix A.4 Near-Commutativity Conditions

The operator set is not assumed to be fully commuting. Instead, SORT imposes controlled bounds on commutator norms:

These tolerances ensure algebraic stability without requiring exact closure under commutation.

Appendix A.5 Algebraic Closure Relation

Products of operators remain expressible within the operator set:

with coefficients

determined by the internal structure of the algebra.

This relation guarantees that all higher-order compositions remain within the same operator space.

Appendix A.6 Projected Total Operator

The projection mechanism combines with the operator algebra through

which defines the effective operator governing observable-space amplitudes.

Appendix B Projection Kernel Derivations

The projection operator is defined as the fundamental mechanism that links the internal resonance manifold to effective observable quantities. This appendix summarises the derivations underlying the kernel structure, its normalisation, and its interaction with the operator algebra.

Appendix B.1 Definition and Normalisation

The projection operator acts on states

via a non-local kernel

:

The kernel is required to satisfy the normalisation condition

ensuring conservation of projected amplitude under the mapping.

Appendix B.2 Idempotency Condition

For consistency with the idempotent structure of the operator algebra, the projection operator must be approximately idempotent,

Using (

A9), this implies the constraint

Gaussian Kernel Bounds.

Equation (

A12) is satisfied only approximately for Gaussian-type kernels. Performing the convolution explicitly shows that

where

is a bounded second-order differential operator. Thus the deviation from exact idempotency is controlled by

, and the operator norm obeys

In practical evaluations this deviation remains at numerical machine precision. The approximate idempotency used in the main text is therefore justified for the deterministic mock environment; a full classification of kernels satisfying exact idempotency is part of the planned analytical developments for Version 5. Note that the approximate idempotency discussed here holds only within the controlled numerical bounds of the mock environment. No claims of exact kernel idempotency are made in the present formulation.

A Gaussian-type kernel satisfies this condition to leading order in its bandwidth parameter

:

Appendix B.3 Phase Encoding and Non-Locality

To incorporate resonance-induced phase correlations, the kernel includes a phase factor

where

denotes the real Gaussian envelope, and

is a non-local phase functional encoding structural correlations of the resonance manifold.

The phase term contributes to observable-scale drift and clustering via

Appendix B.4 Interaction with the Total Operator

The projected total operator takes the form

with

defined in Eq. (

A3).

Expanding the action on a state

gives

showing explicitly how the kernel smears and re-weights the internal resonance structure.

Appendix B.5 Spectral Consistency

The spectral form discussed in Appendix A follows from the fact that

is Hermitian under the kernel-induced inner product:

Hermiticity ensures a real spectrum and the decomposition

with orthonormal eigenfunctions under (

A20).

Appendix B.6 Conditions for Stability

The kernel must satisfy:

ensuring:

1. quasi-idempotency, 2. compatibility with the operator algebra, 3. stability under small kernel deformations.

Appendix C Numerical Parameters and Configuration Files

This appendix summarizes the numerical settings, fixed parameters, and configuration files used in the deterministic mock environment described in

Section 6. All values reproduce the results of Version 4 of the SORT framework.

Appendix C.1. Global Numerical Parameters

Grid size (Layer III):

Precision: double precision (64-bit floating point)

Deterministic seed: 117666

FFT implementation: standard NumPy/SciPy FFT backend

Boundary conditions: periodic

-

Tolerance thresholds:

- –

Idempotency residuals:

- –

Commutator norms:

- –

Jacobi residuals:

Appendix C.2. Configuration Files Included in the Archive

The Zenodo archive includes the full deterministic mock environment:

-

05_config.yaml

Global numerical parameters, grid size, FFT settings.

-

06_operators.json

Definitions of all 22 resonance operators, idempotency flags, structural signatures.

-

params_alpha_v2.json

Values of the projection-density coupling and structural coefficients.

-

layer1_metrics.json

Symbolic idempotency checks and Jacobi diagnostics.

-

layer2_metrics.json

Structural verification output for and pairwise operator coupling.

-

layer3_mock.json

Final resonance projections and mock cosmological fields.

-

manifest.json

SHA256 hashes of all files; ensures reproducibility of the freeze.

Appendix C.3. Hash Verification

The archive-level integrity is guaranteed by:

SHA256 (sort_mock_v2.zip) =

B4195C7AC3815D82A57563D555F9998DA7FA942943F88F504F3BAB6E23DC1954

If this checksum matches, all inner files are unchanged relative to the Version 4 mock configuration.

Appendix D Glossary of Symbols

| Symbol |

Meaning |

Description |

|

Resonance Operator |

One of the 22 idempotent operators forming the resonance manifold. |

|

Total Projector |

Product–projector formed from all ; central structural object. |

|

Light–Balance Weight |

Coefficient ensuring global neutrality . |

|

Projection Operator |

Non–local kernel-based projector mapping resonance states to effective geometry. |

|

Projection Kernel |

Encodes phase, non–locality and structural deformation. |

|

Projected State |

State obtained after applying . |

|

Effective Density |

Defined as ; source of macro-scale drift effects. |

|

Foreground Potential |

Projection-induced potential relevant for early galaxy formation. |

|

Hubble Constant |

Reference expansion rate. |

|

Hubble Drift |

Localised variability predicted by the model. |

References

- onnes, A. Noncommutative Geometry; Academic Press: San Diego, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- onnes, A., & Marcolli, M. (2008). Noncommutative Geometry, Quantum Fields and Motives. American Mathematical Society, Providence.

- shtekar, A. New Variables for Classical and Quantum Gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2244–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ovelli, C. ovelli, C. (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ovelli, C. Loop Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativ. 1998, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- erez, A. The Spin Foam Approach to Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Relativ. 2013, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- acobson, T. Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- admanabhan, T. Thermodynamical Aspects of Gravity: New insights. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- erlinde, E. (2011). On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. J. High Energy Phys. 2011, 2011(4), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- erlinde, E. Emergent Gravity and the Dark Universe. SciPost Phys. 2017, 2, 016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ousso, R. The Holographic Principle. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 825–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- usskind, L. The World as a Hologram. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aldacena, J. The Large N Limit of Superconformal Field Theories and Supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1999, 2, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- itten, E. Anti de Sitter Space and Holography. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 253–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- i Valentino, E., Mena, O., Pan, S., Visinelli, L., Yang, W., Melchiorri, A., Mota, D. F., Riess, A. G.,; Silk, J. In the realm of the Hubble tension—a review of solutions. Class. Quantum Grav. 2021, 38, 153001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iess, A. G., Yuan, W., Macri, L. M., Scolnic, D., Brout, D., Casertano, S., Jones, D. O., Murakami, Y., Anand, G. S., Breuval, L., Brink, T. G., Filippenko, A. V., Hoffmann, S., Jha, S. W., Kenworthy, W. D., Mackenty, J., Stahl, B. E.,; Zheng, W. A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km s-1 Mpc-1 Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 934, L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- lanck Collaboration, Aghanim, N., Akrami, Y., et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESI Collaboration, Adame, A. G., Aguilar, J., et al. DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.03002. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03002. [Google Scholar]

- bdalla, E., Abellán, G. F., Aboubrahim, A., et al. Cosmology intertwined: A review of the particle physics, astrophysics, and cosmology associated with the cosmological tensions and anomalies. J. High Energy Astrophys. 2022, 34, 49–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- inkelstein, S. L., Bagley, M. B., Ferguson, H. C., et al. The Complete CEERS Early Universe Galaxy Sample: A Surprisingly Slow Evolution of the Space Density of Bright Galaxies at z∼8.5–14.5. Astrophys. J. 2024, 969, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- arikane, Y., Ouchi, M., Oguri, M., et al. A Comprehensive Study of Galaxies at z∼9–16 Found in the Early JWST Data: Ultraviolet Luminosity Functions and Cosmic Star Formation History at the Pre-reionization Epoch. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 2023, 265, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aiolino, R., Übler, H., Perna, M., et al. JADES: Spectroscopic confirmation and properties of extremely faint galaxies in the epoch of reionization. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 687, A67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ogdán, Á., Goulding, A. D., Natarajan, P., et al. Evidence for heavy seed origin of early supermassive black holes from a z≈10 X-ray quasar. Nat. Astron. 2024, 8, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- acucci, F., Nguyen, B., Carniani, S., Maiolino, R.,; Fan, X. JWST CEERS and JADES Active Galaxies at z=4–7 Violate the Local M•–M★ Relation at >3σ: Implications for Low-mass Black Holes and Seeding Models. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2023, 957, L3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- olchinski, J. (1998). String Theory, Vol. 1: An Introduction to the Bosonic String. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- reen, M. B., Schwarz, J. H., & Witten, E. (2012). Superstring Theory, Vols. 1–2 (25th Anniversary Edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- molin, L. (2001). Three Roads to Quantum Gravity. Basic Books, New York.

- riti, D. (2009). Approaches to Quantum Gravity: Toward a New Understanding of Space, Time and Matter. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- aez, J. C.,; Stay, M. Physics, Topology, Logic and Computation: A Rosetta Stone. In New Structures for Physics. Lecture Notes in Physics 2011, 813, 95–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- oecke, B., & Kissinger, A. (2017). Picturing Quantum Processes: A First Course in Quantum Theory and Diagrammatic Reasoning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- on Neumann, J. (1932/1955). Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Princeton University Press, Princeton. (Translated by R. T. Beyer, 1955).

- adison, R. V., & Ringrose, J. R. (1997). Fundamentals of the Theory of Operator Algebras, Vols. I–II. American Mathematical Society, Providence.

- loyd, S. (2006). Programming the Universe: A Quantum Computer Scientist Takes on the Cosmos. Knopf, New York.

- egmark, M. (2014). Our Mathematical Universe: My Quest for the Ultimate Nature of Reality. Knopf, New York.

- enrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Jonathan Cape, London.

- molin, L. (2019). Einstein’s Unfinished Revolution: The Search for What Lies Beyond Quantum. Penguin Press, New York.

- ossenfelder, S. (2018). Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray. Basic Books, New York.

- oether, E. (1918). Invariante Variationsprobleme. Nachr. Ges. Wiss. Göttingen, Math.-Phys. Kl. (English translation: Transp. Theory Stat. Phys. 1(3), 186–207, 1971). 1918, 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- instein, A., Podolsky, B.,; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ekenstein, J.D. Black Holes and Entropy. Phys. Rev. D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- awking, S.W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).