1. Introduction

Bike-sharing programs (BSPs) have become an integral component of contemporary urban transportation, reflecting the growing need to move away from motorized vehicles to more sustainable travel modes [

1]. Their rapid expansion helps address pressing urban challenges, most notably traffic congestion and poor air quality, since motorized transport remains a major source of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide [

2]. By integrating and promoting bicycles into urban mobility networks, BSPs contribute to emission reductions and the conservation of natural resources. In Shanghai, for example, bike-sharing was estimated to save 8,358 tons of fuel annually, resulting in reductions in carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions and measurable improvements in air quality [

3]. Beyond environmental benefits, BSPs promote public health by encouraging physical activity and deliver economic benefits through shorter travel times, lower transportation costs, and reduced demand for parking infrastructure. Together, these outcomes position BSPs as an effective strategy for cleaner air, decarbonization, more efficient mobility, and improved population health [

4,

5], while supporting a larger shift towards cycling as an efficient mode of transport [

6]. Currently, bike-sharing programs operate primarily in two formats: station-based and dockless. Station-based systems (DBS) rely on fixed docking stations, where users collect and return bicycles, while dockless systems (DLBS or Free-float, FFS) offer greater flexibility by allowing bicycles to be parked and locked anywhere within the designated service area. This flexibility, however, has a counterpart in uncontrolled—and at times obstructive—parking of shared vehicles. DLBS operations leverage GPS and mobile technology for bicycle tracking and rental via smartphone applications. The resulting free-floating model has driven the rapid global diffusion of DLBS, positioning it as a promising approach to improving urban mobility and advancing environmental sustainability. Nevertheless, DLBS also faces persistent challenges, including bicycle theft, vandalism, the distribution of bicycles in the territory, obstructive parking, and difficulties in ensuring reliable tracking of the bike position [

7]. On the other hand, conventional (or “muscular”) bicycles have traditionally formed the backbone of bike-sharing systems, primarily serving shorter trips with demand strongly influenced by terrain morphology [

7]. By contrast, electric bicycles (e-bikes) provide motorized assistance, markedly enhancing their practicality and appeal: e-bikes are particularly effective for navigating hilly areas [

8] and for enabling longer travel distances [

9] and for reducing travel time. Their introduction has broadened the shared cycling market by attracting new user groups and lowering barriers for individuals with physical limitations [

10]. While initially complementing conventional bicycle use, e-bikes often become a substitute over time—reducing demand for muscular bicycles yet substantially increasing overall shared cycling activity [

9]. Moreover, e-bikes, considering their enhanced performances, show greater potential for replacing car trips than their muscular counterparts [

11]. A wide range of factors shapes usage patterns in bike-sharing programs (BSPs), as widely studied in the recent review from Mafi et al. [

12]. Among the most important factors, there are weather conditions, including temperature [

13,

14], precipitation [

15], wind speed [

16], humidity, and seasonal variation [

14], which can significantly affect ridership levels. Built environment and land-use characteristics also matter, such as the availability of cycling infrastructure [

17], perceived safety [

18], topography [

19], land-use mix, and the degree of integration with public transport or mobility hubs [

20,

21,

22]. In addition, demographic attributes, including age, gender, income, education level, and motor vehicle ownership, are important determinants of BSP usage [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Finally, vehicle provision and service fees have a strong impact on usage of these transport services.

In Italy, the bike-sharing landscape has been shifting toward free-floating systems. According to the 2024 report of the Italian National Shared Mobility Observatory [

27], in 2016 all available services were station-based; beginning in 2017, the first dockless solutions were introduced. By 2023, of 47 bike-sharing services, 30 were dockless, with 77% of the national fleet operating in free-float mode. The same report ranks Bologna and Florence third and fourth, respectively, for electric fleet size. Overall, the market is moving toward electrification, with e-bikes accounting for 67% of the Italian shared bicycle fleet.

Given the limited number of studies on free-floating and electric bike-sharing and scooter-sharing services [

8], this paper aims to identify how BSS is used, based on revealed-preference data from users’ trips in two medium-size Italian cities. The findings are intended to assist planners and operators in designing better services, also by better understanding the differences between electric and muscular modes of shared micro-mobility. In the literature, GPS data have proven highly valuable for studying shared micromobility across multiple dimensions, including spatial analyses of territorial and behavioral factors that promote bike and scooter use [

28,

29,

30], intra-week and gender differences in usage [

31], contrasts between privately owned and shared bicycles [

32], equitable access to transport [

33], the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic [

34], and the environmental benefits of bike sharing [

35]. GPS records embed users’ revealed preferences with spatial context, offering considerable flexibility for diverse study designs, and new methods are emerging to acquire such datasets with high reliability and low effort [

36]. Although many studies leverage GPS information, the authors are aware of only one case that attempts path reconstruction when full traces are unavailable [

34], and even there the approach is used primarily to improve distance estimation compared with the Euclidean alternative.

This study assesses shared services using descriptive statistics and temporal and spatial analyses. We examine daily demand patterns, weekly dynamics of trip length, duration, and speed, daily turnover and productivity across trip-distance ranges, and monthly variations in trip volume, fleet size, and turnover, with comparisons across available modes. A productivity analysis quantifies trips per vehicle by mode for different trip-distance ranges, providing operators and planners with insight into the distances typically served by each mode. Temporal analysis at the week level highlights differences between working days and weekends, while monthly analysis reveals seasonality. The spatial analysis divides each city into 250 × 250 meter grid cells to identify zones with a surplus or deficit of vehicles, that is, where more trips end than begin, and vice versa. A key contribution of this study is the ability to derive insights that typically require full GPS traces, using only origin–destination and time records. By applying routing methods to microscopically detailed network models, we reconstruct plausible paths and analyze trip length, average speed, and temporal patterns. This approach broadens the usefulness of operator data, reduces reliance on continuous tracking, and provides planners and operators with actionable information even when only minimal trip attributes are available. The method is also advantageous from a privacy perspective, since bike-sharing data can be sensitive due to real-time tracking of individuals and operators seldom share complete traces.

This paper is organized into six sections. Methodology outlines preprocessing steps and explains the procedures used to reconstruct trips from GPS origin and destination points with their timestamps. This procedure enables the reconstruction of likely paths and the estimation of trip length and average speed, and it supports data filtering to remove anomalous trips. Case Study describes the main characteristics of the two Italian cities. Dataset Description and Preparation details the dataset and the application of the methodology to Florence and Bologna. Results presents descriptive statistics, monthly dynamics, mode-specific patterns, and spatial analysis together with plausible interpretations for both cities. Discussion synthesizes the findings across the two case studies, assesses their implications for planning and operations, and compares the cases. Conclusions summarize the main contributions, highlight practical points for operators and planners, and indicate priorities for future research.

3. Case Study

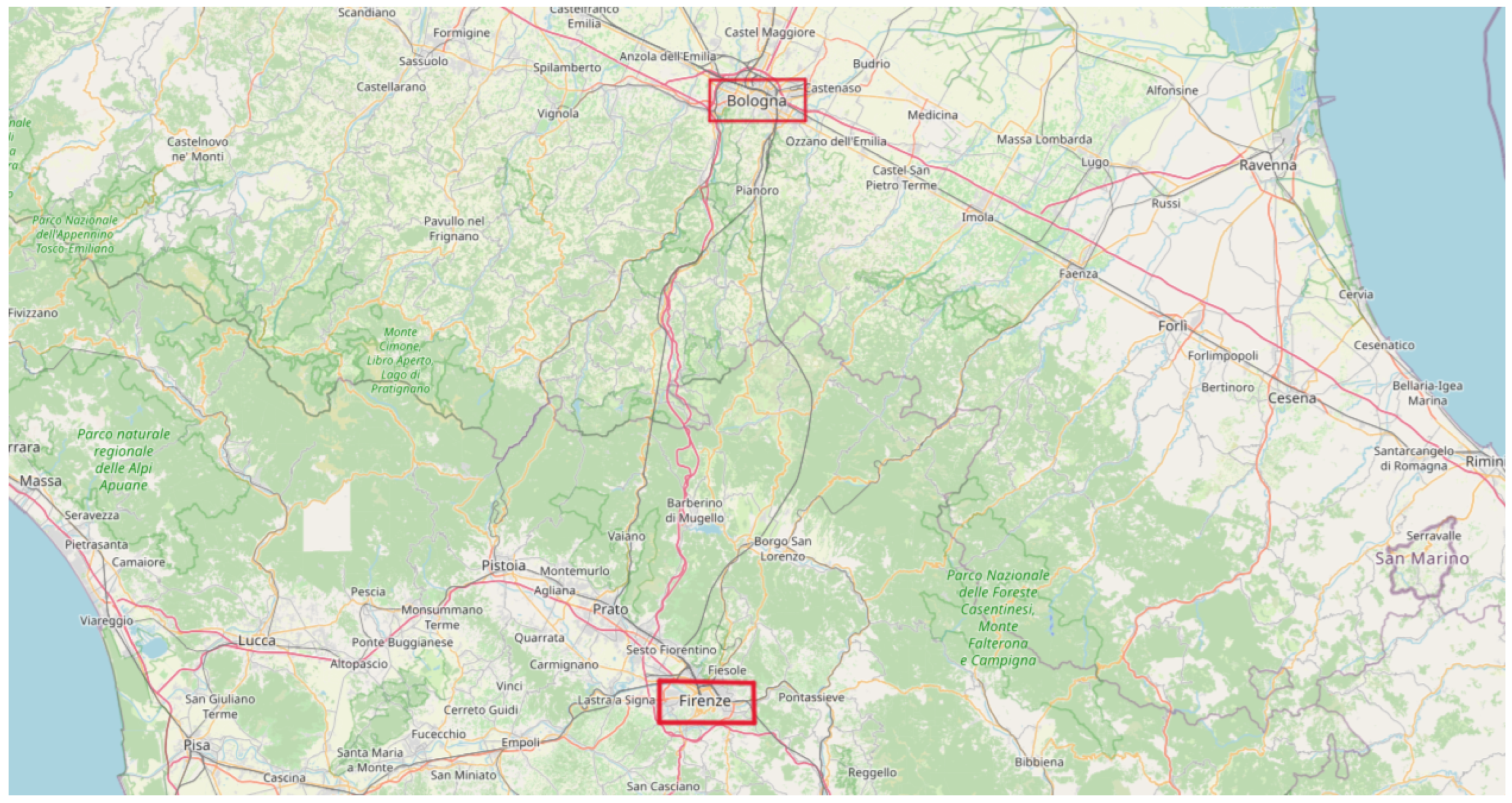

The methods shown in the Methodology section has been applied to the two case studies of Florence and Bologna, two medium-sized cities in central northern Italy with comparable territory and population. Florence covers 102 km² and has approximately 362 thousand inhabitants; Bologna covers 140 km² and has approximately 393 thousand inhabitants. The historic center of Florence, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, spans about 5 km², while Bologna’s historic center extends over roughly 4.5 km². Florence experiences heavy year-round tourism, about 12.750 million visitors in 2023 [

40]. Bologna has a lower tourist load than Florence, but a large share of university students live in the city. In territorial terms the two cities are similar; however, differences in user composition: tourists in Florence and university students in Bologna, can substantially influence demand for bike-sharing services. Both cities have a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (PUMS, Piano Urbano della Mobilità Sostenibile). Bologna was the first Italian city to adopt a metropolitan SUMP, formally approved in 2019, while Florence followed with its metropolitan plan in 2021. Both plans align with EU climate targets, modal shift, and integrated mobility systems. Bologna’s strategy centers on the 1,000 km “Bicipolitana” cycling network, which has helped attract new riders [

41], a new tramway system, and a regionally coordinated approach to micromobility and car sharing. Florence’s plan builds on its existing tram infrastructure, expands the cycling network toward a 200 km target, and introduces intermodal incentives such as free shared-bike access for public transport users. Both cities articulate a Mobility-as-a-Service vision, though no operational platform is yet deployed. Bologna’s PUMS sets an objective to integrate services, especially around intermodality and smart mobility, but does not specify a functioning MaaS platform. It calls for digitalization and service aggregation, linking bike sharing, car sharing, and public transport within a common platform. Florence’s plan likewise emphasizes intermodal integration and frames MaaS as a future development path, highlighting digital tools and “smart mobility” without concrete deliverables. Although public funding has been allocated to similar initiatives in several Italian cities, MaaS remains largely at the pilot stage in practice [

42].

Regarding service type, both Florence and Bologna operate free-floating systems, primarily served by electric bicycles. RideMovi, the main provider in both cities, offers three sharing options in Florence: bikes, e-bikes, and e-scooters, while in Bologna it offers two: bikes and e-bikes.

Figure 2.

Map of Italy with the two case studies highlighted in red. Map downloaded from OpenStreetMap, OpenStreetMap Foundation, under CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure 2.

Map of Italy with the two case studies highlighted in red. Map downloaded from OpenStreetMap, OpenStreetMap Foundation, under CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

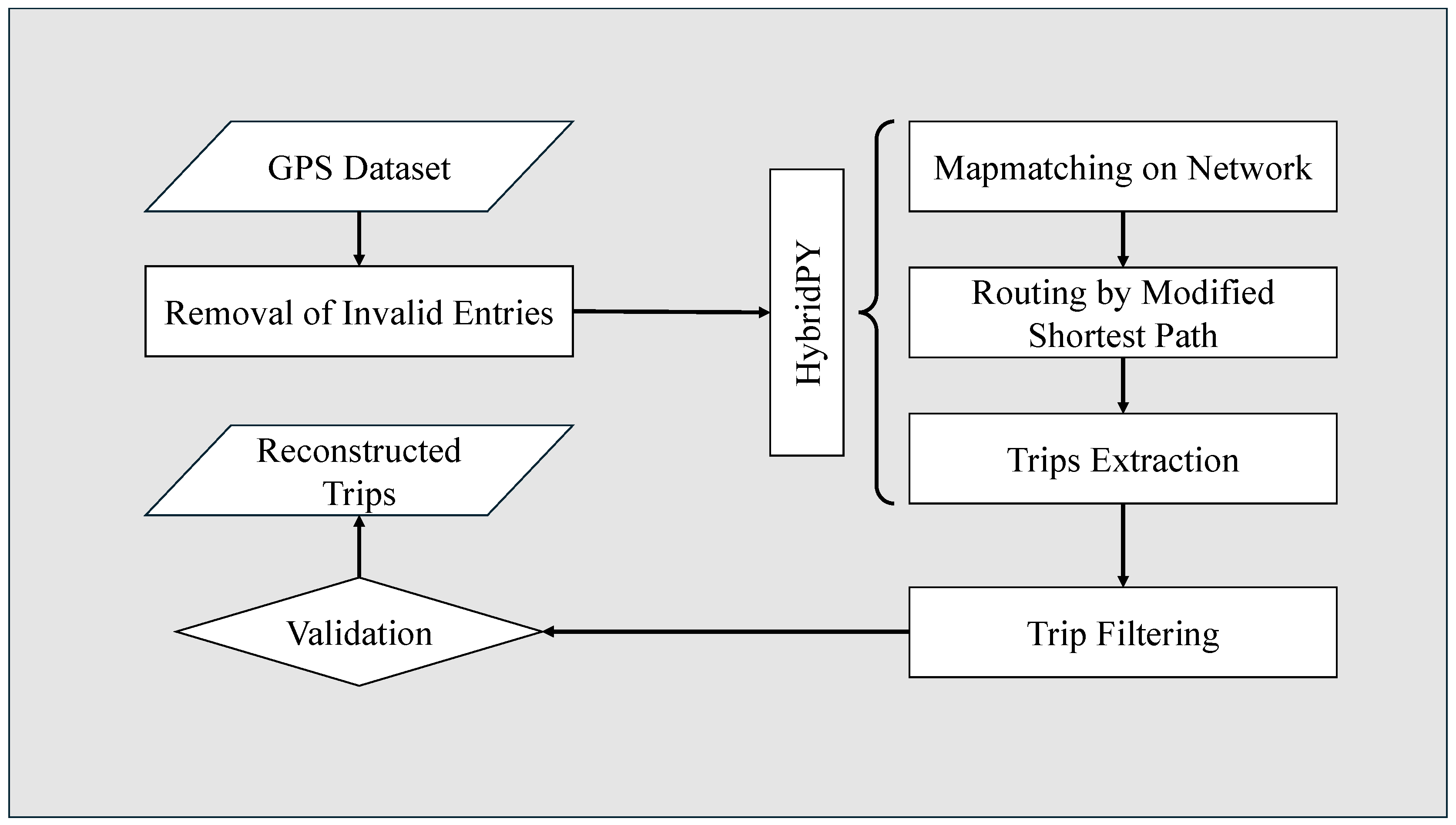

4. Dataset Description and Preparation

RideMovi and Società Reti e Mobilità provided GPS data for Florence and Bologna’s shared micromobility services for 2023 as comma-separated value files. The dataset includes the latitude, longitude, and time of trip origins and destinations, the vehicle type, and the vehicle ID; individual trips do not contain full GPS trajectories. The data were map-matched to the Bologna and Florence urban networks in HybridPY [

37,

38].

The Bologna network was imported from OpenStreetMap (OSM) and has been refined and regularly updated through multiple projects. Florence’s network was imported from OSM and subsequently cleaned and updated to support reliable map-matching and routing for bicycles, e-bikes, and e-scooters within the HybridPY environment by clustering intersection and ensuring bikeway lanes continuity. After map-matching the origin and destination of each trip to the SUMO network model, we performed the routing with the method of Schweizer et al. [

39], as outlined in

Section 2. The extracted data were filtered to remove trips with anomalies. Filtering was applied to trip distance (from routing estimation), trip time (from the data), and space-average speed (computed as distance over time, thus an estimate). Trips that were too short in distance or time, or unrealistically slow or fast, were removed. Such filtered trips may reflect errors in the dataset or incorrect routing. Routing errors can occur for round-trips or for trips with multiple detours between origin and destination. The authors acknowledge that these trips are of interest, but with the current data availability from the operator, that is, origin–destination points only, there is no reliable way to distinguish non-direct trips from data errors. The filtering thresholds and results are reported in

Table 1. Trips with reconstructed lengths below 400 meters are excluded, since they can be covered in just over 100 seconds of motion. As unlocking and locking times are included, these would excessively distort the estimated average speed. Very short trips should also be removed, as they could be round trips with close origin and destination; in these cases the route reconstruction would fail. Rentals shorter than 3 minutes or longer than about 40 minutes are excluded as not representative: the former are too brief, and the latter may include substantial pauses that cannot be reconstructed from origin–destination data. Trips with average speeds below 1 m/s are discarded as slower than walking pace, while those above 6.94 m/s (25 km/h) are removed as unrealistically fast even for an e-bike with a 25 km/h speed limit for pedal assistance. The filtering ranges and retained trip shares are reported in

Table 1.

Validation of the reconstructed trips was carried out by comparing them with a previous study on bicycle mobility in Bologna. Rupi et al. [

43] analyzed continuous GPS traces from the European Cycling Challenge 2016, which allowed the authors to reconstruct actual routes and speed profiles. Since our dataset contains only origin and destination points, we validated the routing by comparing the distribution of average trip speeds from our sample with those reported by Rupi et al. (2020). Rupi et al. (2020) derived their average speed distribution from speed profiles of trips undertaken during working days between 05:00 and 11:00 in May 2016 in Bologna during the European Cycling Challenge (

https://cyclingchallenge.eu/ecc2016). To obtain a comparable sample, we compare our reconstructed trips from May 2023 that started between 05:00 and 11:00 on working days, restricting the analysis to muscular bicycles, as only muscular bikes were used in May 2016. Several differences should be noted: (i) Rupi et al. measured speeds for participants who volunteered for data collection, which may bias the sample toward experienced or cycling-enthusiast users; (ii) they assumed a fixed time for unlocking, on the basis that users had already started app tracking, and subtracted this from total trip time; (iii) our trip times include unlocking and locking for shared bikes, even though these durations are generally quite short in the RideMovi service; (iv) our filtering is inherently less precise because we lack full GPS traces to select the most representative trips; and (v) limiting the time window and bike type to muscular bicycles yields a smaller sample, since muscular shared bikes were much less than e-bikes in Bologna in 2023.

Average speed distributions are broadly similar. An 18% discrepancy was expected, as Rupi et al. [

44], using the same GPS traces of Rupi et al. (2020), found that cyclists tend to travel routes about 20% longer than the shortest path to avoid high-traffic roads. Consequently, our reconstruction likely underestimates the true route length and yields speeds that are approximately 20% lower (see

Table 2).

We also compared speed distributions with similar European case studies [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Methods in those studies include GPS-trace analysis, video recording, and built-on speed sensors. In our data, average speeds range from 2.90 to 3.45 m/s for muscular bicycles and from 3.53 to 4.35 m/s for e-bikes. In the reviewed cases, reported averages range from 2.50 to 4.25 m/s for bicycles and from 4.83 to 6.00 m/s for e-bikes and mixed samples. Our averages lie at the lower end of these ranges, consistent with the estimated 18% underestimation of average speed in our dataset. Other factors may impact average speeds such as climate or street-layout.

Table 3.

Comparison of average values of trip speed with other EU case studies. Please note that here the speed is calculated on trips filtered based on the values in

Table 1

Table 3.

Comparison of average values of trip speed with other EU case studies. Please note that here the speed is calculated on trips filtered based on the values in

Table 1

| Study |

Location |

Vehicle Type |

Data acquisition Method |

Av. Speed [m/s] |

Standard Deviation [m/s] |

| This Study |

Bologna (Italy) |

Bike |

GPS o/d |

2.90 |

0.88 |

| This Study |

Bologna (Italy) |

E-Bike |

GPS o/d |

3.53 |

1.10 |

| This Study |

Florence (Italy) |

Bike |

GPS o/d |

3.45 |

1.08 |

| This Study |

Florence (Italy) |

E-Bike |

GPS o/d |

4.35 |

1.27 |

| Ul-Abdin et al. [45] |

Belgium |

Bike and E-Bike |

GPS Trace |

4.36 |

1.69 |

| Lyubenov et al. [46] |

Bulgaria |

Bike |

GPS Trace |

2.50 |

0.05 |

| Paulsen et al. [47] |

Denmark |

Bike and E-Bike |

Video Recording |

6.00 |

1.00 |

| Schleinitz et al. [48] |

Germany |

Bike |

Speed sensor |

4.25 |

0.64 |

| Schleinitz et al. [48] |

Germany |

E-Bike |

Speed sensor |

4.83 |

1.22 |

6. Discussion

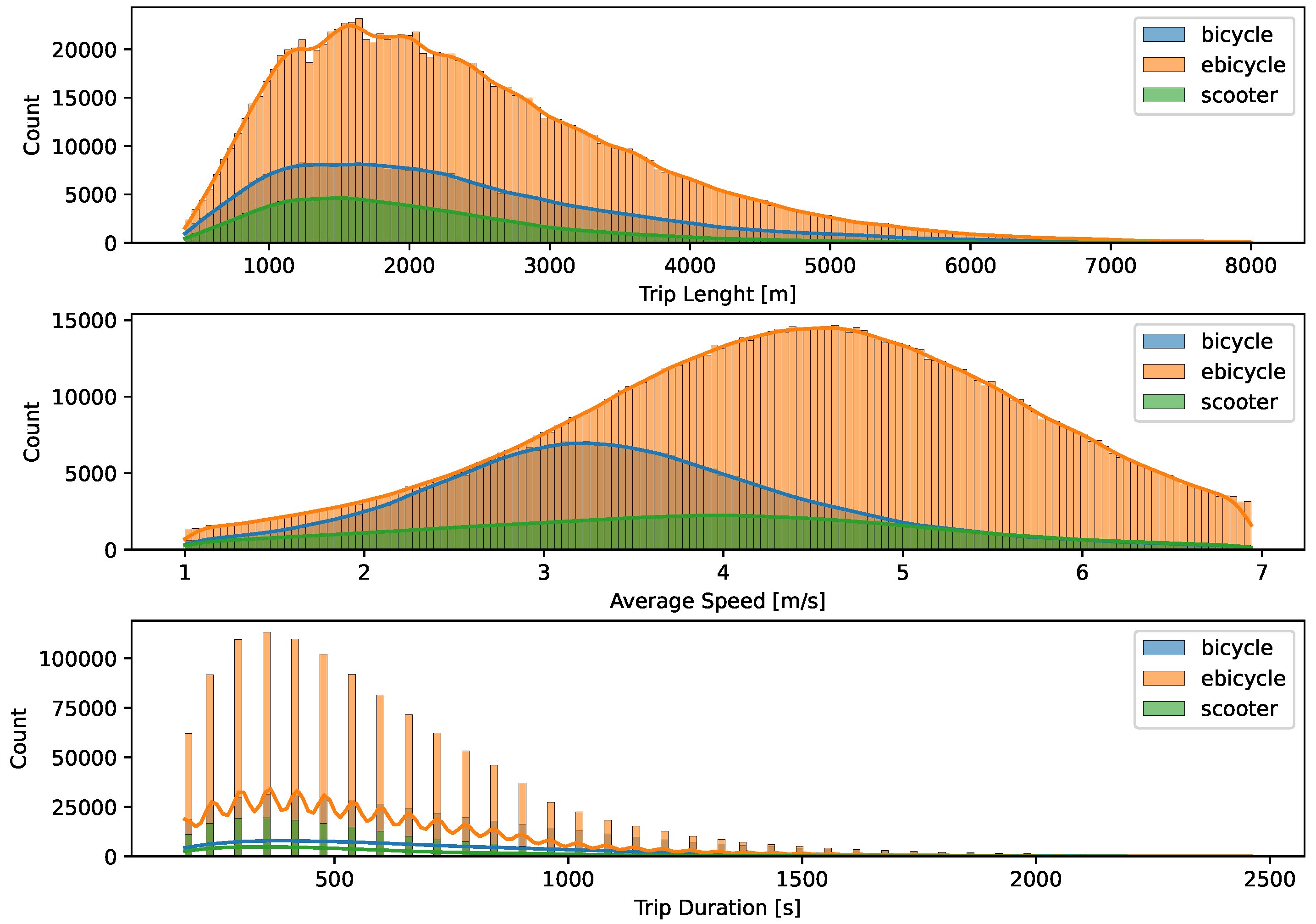

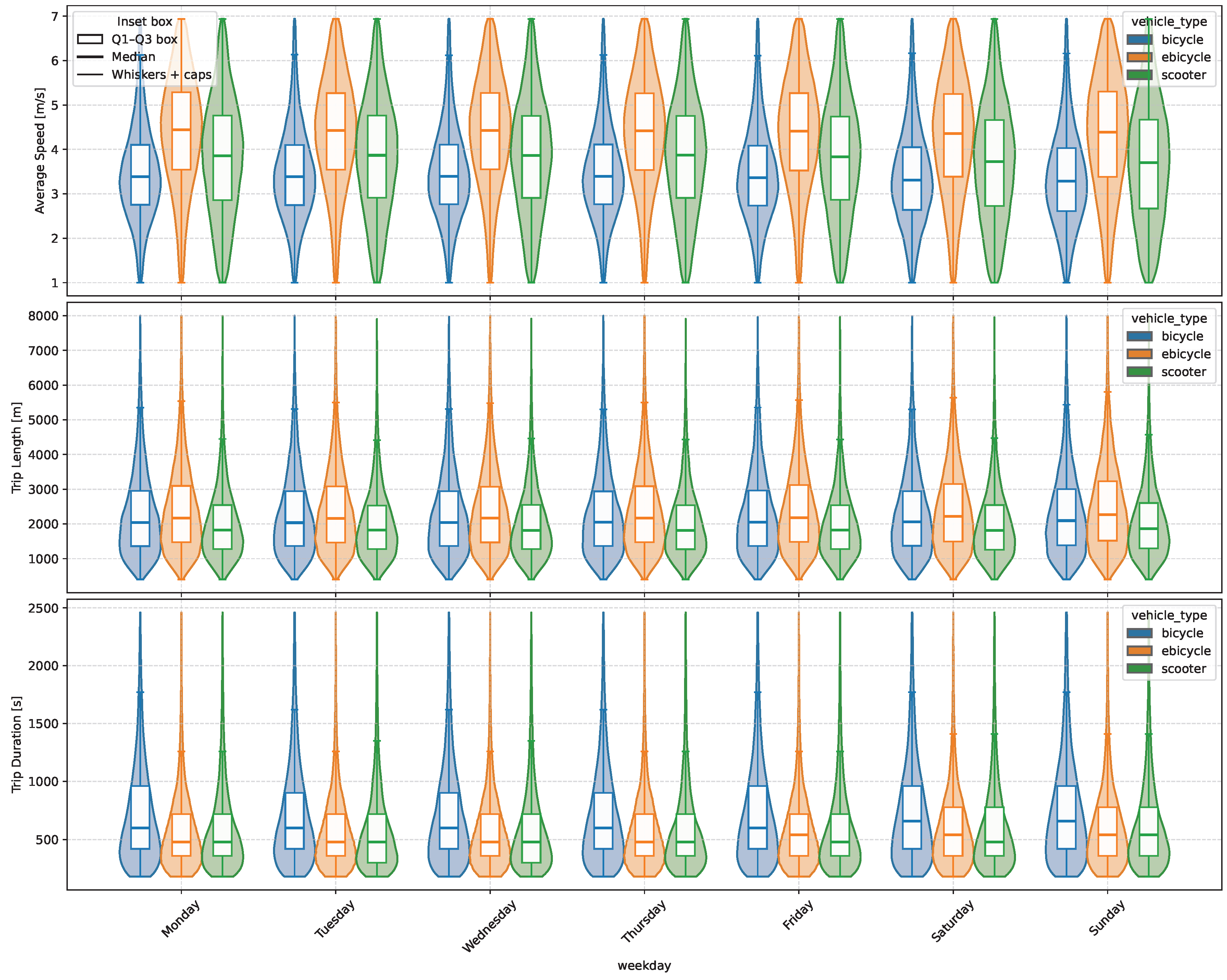

The Bologna and Florence cases display broadly similar distributions of trip parameters, with notable differences summarized in

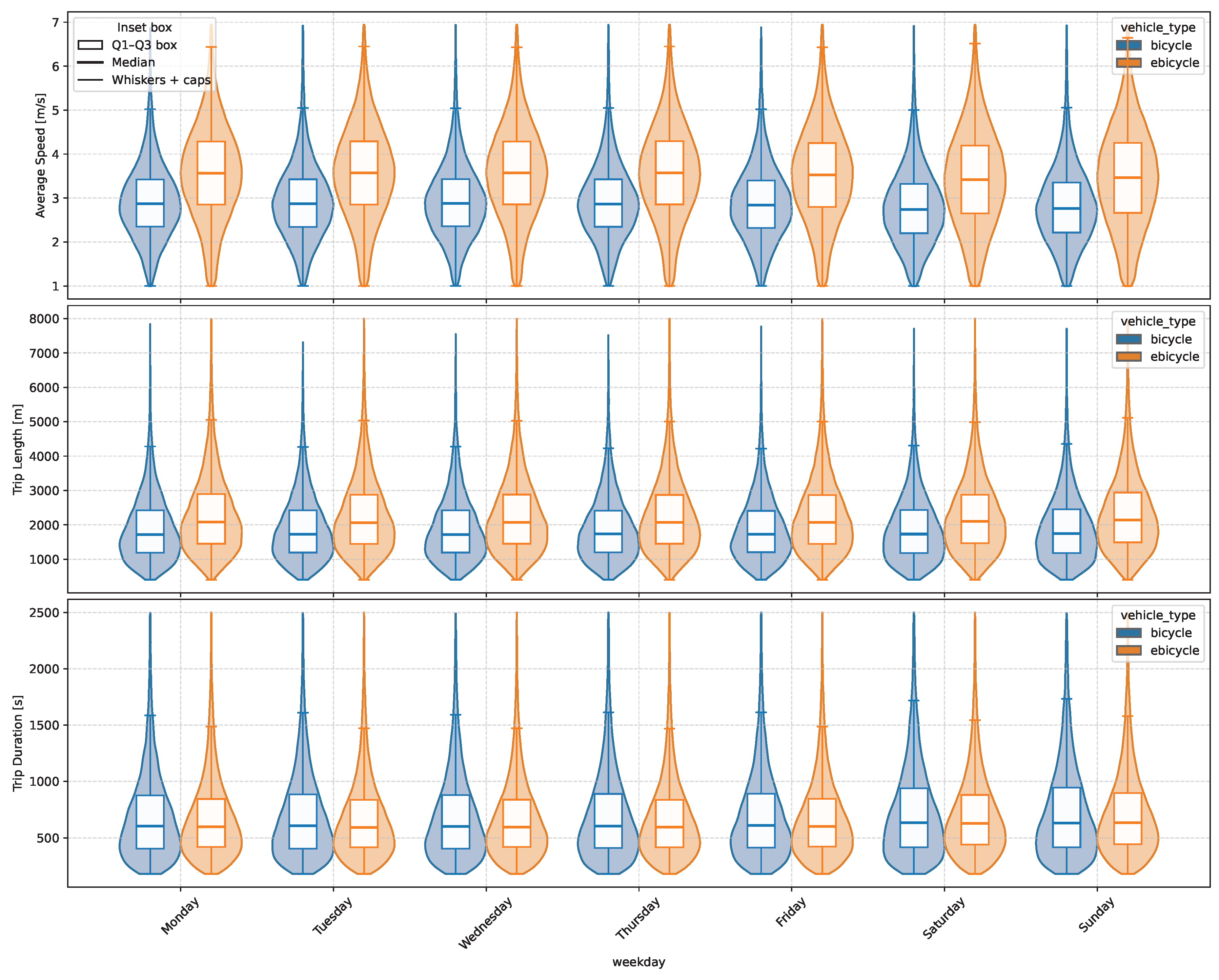

Table 8. On average, bicycles were used for longer trips in Florence (+19.9%), whereas trip lengths for e-bikes were comparable across the two cities. Moreover, in Florence, distances that in Bologna are covered with muscular bikes seem to be covered by e-scooters instead. The most pronounced difference concerns the average speed: Florence trips were faster by 23.2% for e-bikes and 19.0% for bicycles. Consequently, e-bike trip times in Florence were 14.0% lower, a natural outcome of the preceding parameters. Florence users are able to exhibit higher speeds with the same vehicles, the difference is even greater for e-bikes, suggesting that users in Florence are more capable in leveraging the extra power provided by the electric motor and, in general, prioritize speed more than fatigue with respect to Bologna. This also emerges from the reduced travel times in Florence. Another explanation for this effect is the more hilly terrain in Bologna, which is run across the whole city from mild slopes. Though the electric bike assist should greatly narrow the speed difference caused by the terrain morphology, the opposite emerges from our results, where the speed difference is even greater for electric bikes. In both case studies, the descriptive statistics related to trip length, duration, and speed did not change significantly between working and weekend days. A possible explanation is that the activities reached with this transport are not greatly different between working and weekend days, but this would not be supported by the demand pattern differences between working and weekend, where is clearly shown a difference in demand pattern with the commuting peak becoming much lees pronounced during the weekend. So, a more coherent explanation is that the activity mix of the demand is very heterogeneous. More on demand patterns and activity types is discussed at the end of this section.

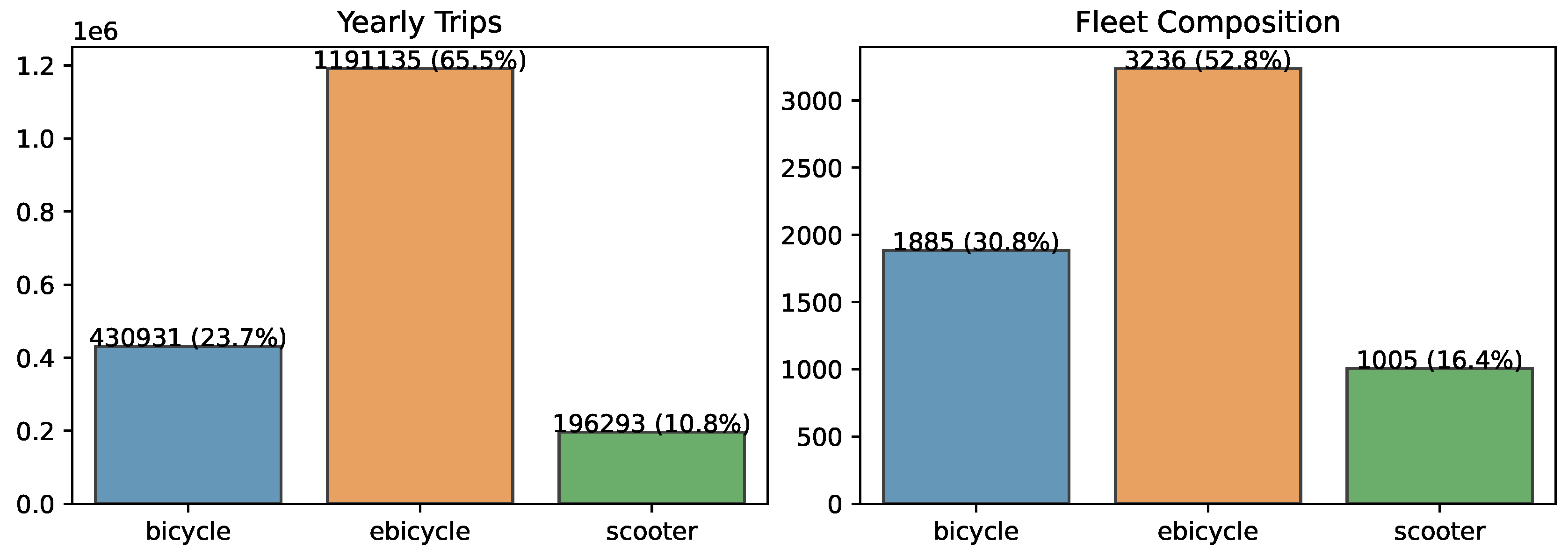

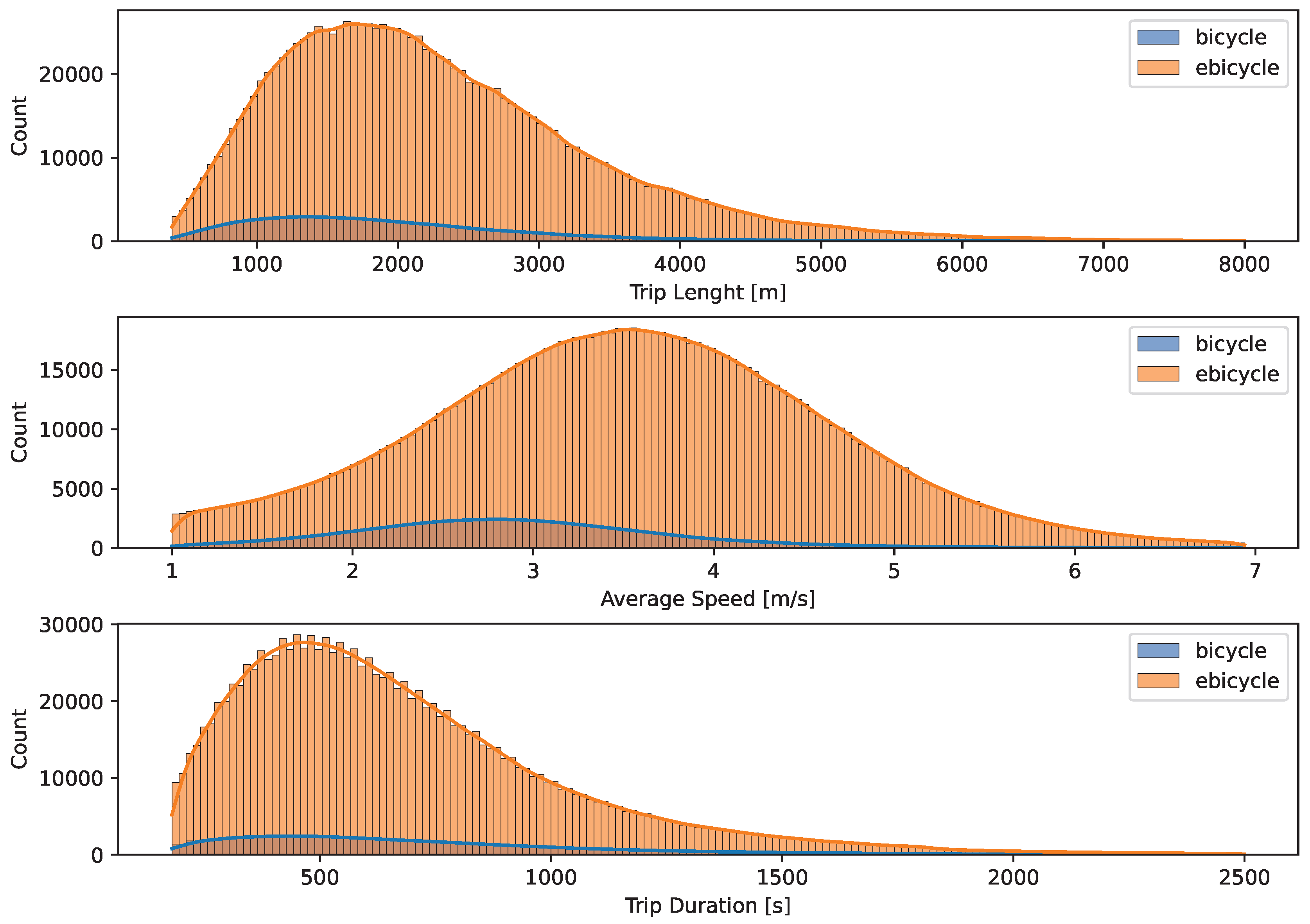

Considering each case study separately allows comparison of trip parameters and mode usage. In Florence (

Table 4), e-bikes show an average trip length similar to bicycles, about 2.4 km (+3.2%), and substantially longer trips than e-scooters (+18.6%). Average speed for e-bikes, 4.35 m/s, is higher than the other modes, +26.1% relative to bicycles and +14.5% relative to e-scooters. These results indicate that, as expected, e-bikes offer a greater range and, more importantly, higher speed, which enhances convenience. Given the reduced effort required to ride an electric vehicle, we expected e-bike trip durations to be similar to bicycle trips, with longer distances covered. This expectation reflects the idea that travel time budgets tend to be relatively constant, allowing longer trips within the same time. However, users may instead prefer quicker and less fatiguing trips to the same destinations. This suggests that users may value time savings more than access to opportunities further away. A different picture emerges in Bologna (

Table 6). e-bikes still lead in speed, +21.7% relative to bicycles, but, unlike Florence, they also have a much longer average trip length (+19.2%) and a similar trip duration (-2.8%) compared with bicycles. This pattern suggests that users are extending their opportunity reach while maintaining the same time budget. While not definitive, these results suggest that users in Bologna and Florence may prioritize different advantages of electric shared mobility: in Bologna is exploited to reach opportunities further away from the origin of the trip, in Florence to reach the same destinations in a shorter time.

The results of this study were compared with two large datasets, one on bike-sharing systems and one on e-scooters, see

Table 9. Waldner et al. [

49] analyze 267 European BSS cases, while Li et al. [

50] cover 30 European e-scooter systems. Median values for Florence and Bologna were compared with those reported in these studies. For Bologna, trip lengths for electric and muscular bicycles are close to the reference values, whereas in Florence, they are higher; e-scooter trip length is slightly above the maximum range reported by Li et al. Average e-bike speeds are substantially higher in both Italian cases than the BSS median reported by Waldner et al. Speed distributions for scooters are not provided in Li et al. Trip durations for e-bikes and bicycles are lower than the Waldner reference, which is consistent with the higher speeds, while e-scooter trip duration falls within the range reported by Li et al. From this comparison, it turns out that the most significant difference between the cited studies and the present study is the speed; for instance, in Florence the median speed is almost double for e-bikes. On the one hand, this could be an indicator of a better service being offered in the Italian cities, both from the share vehicle point of view as well as from an infrastructural point of view, or maybe more experienced users. On the other hand, it could also be an overestimation of speed due to imprecise trip reconstruction. Given that our reconstruction uses a shortest path criterion, we think that the risk of underestimating the speed is higher than overestimating it during route reconstruction, as also shown in the validation for the case of Bologna (see

Table 2). So we prefer to discard the speed overestimation hypothesis also for Florence and conclude that compared to the majority of the reviewed European shared micromobility services, the ones of Florence and Bologna provide a greater speed for the users, either because the transport offer is higher quality, or because the users are more experienced and capable.

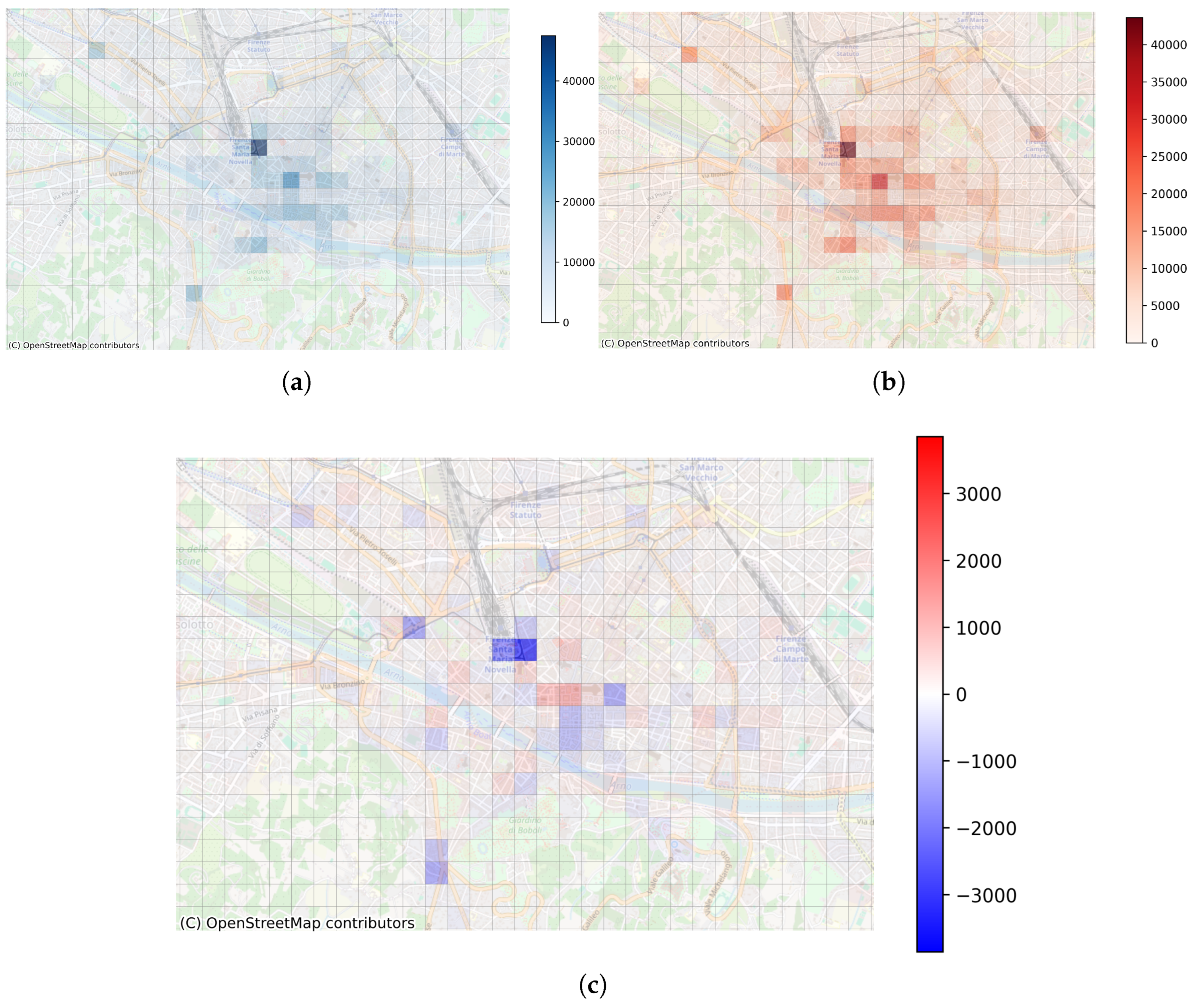

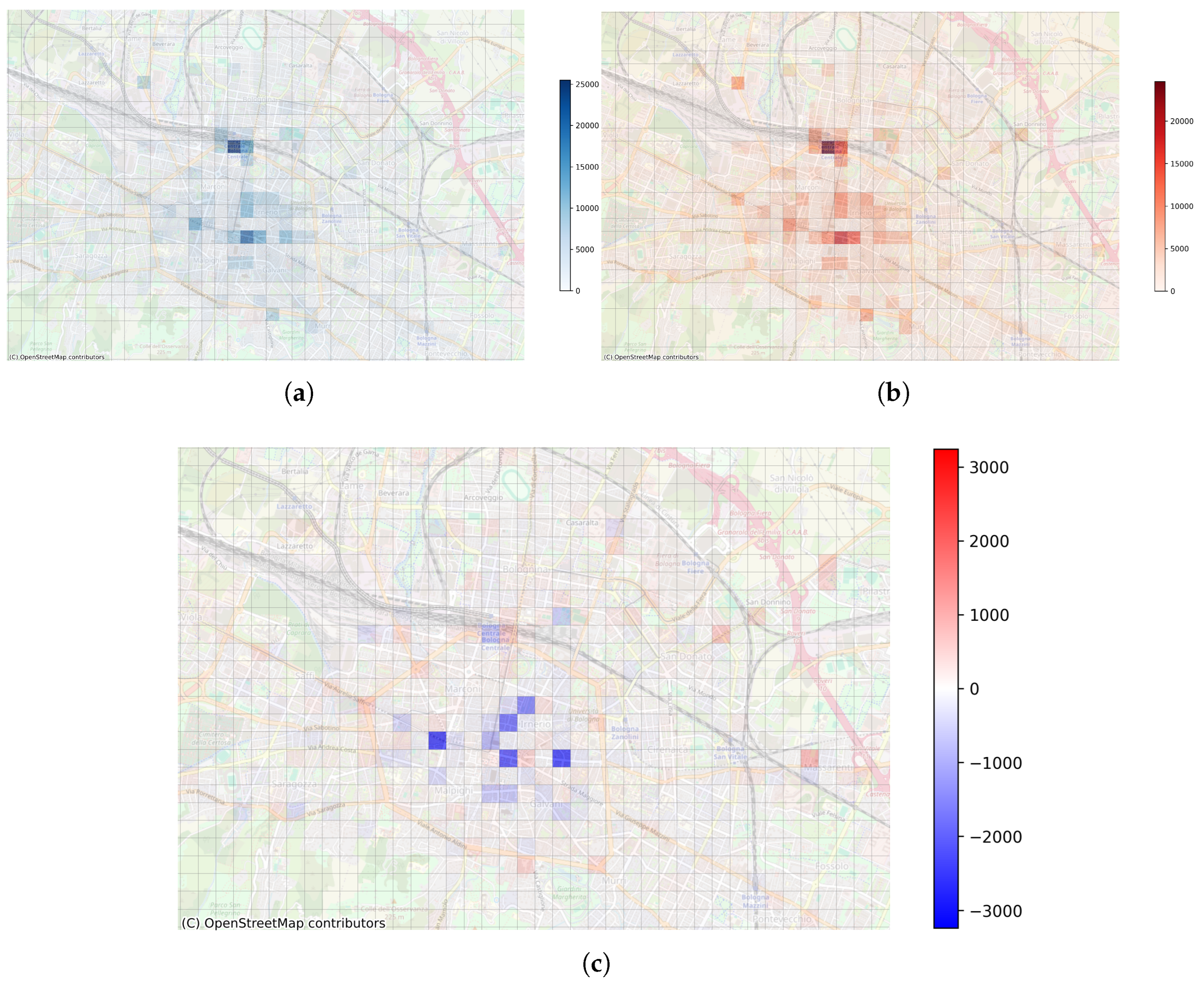

The spatial analyses depict two distinct scenarios. In Bologna, demand tends to move from the historic center toward the periphery. This imbalance suggests that bike sharing is not always used as the sole mode for trips into and out of the center; otherwise, deficits and surpluses would be more evenly distributed. A plausible explanation is that users reach the historic center by other modes and return home using bike sharing. This interpretation is consistent with Bologna’s daily demand pattern, which shows substantial late-night use when public transport is unavailable or operates at low frequency. In Florence, the distribution of surpluses and deficits is more homogeneous, with notable exceptions at the central railway station and the southern entrance to the Boboli Gardens. The greater homogeneity and the concentration of trips within the historic center indicate that demand is more focused in the central area, likely reflecting a larger share of tourists using shared mobility to move quickly between attractions. Florence also exhibits significant nighttime use, although its tram service runs until 02:00, whereas Bologna’s public transport operates until 01:00.

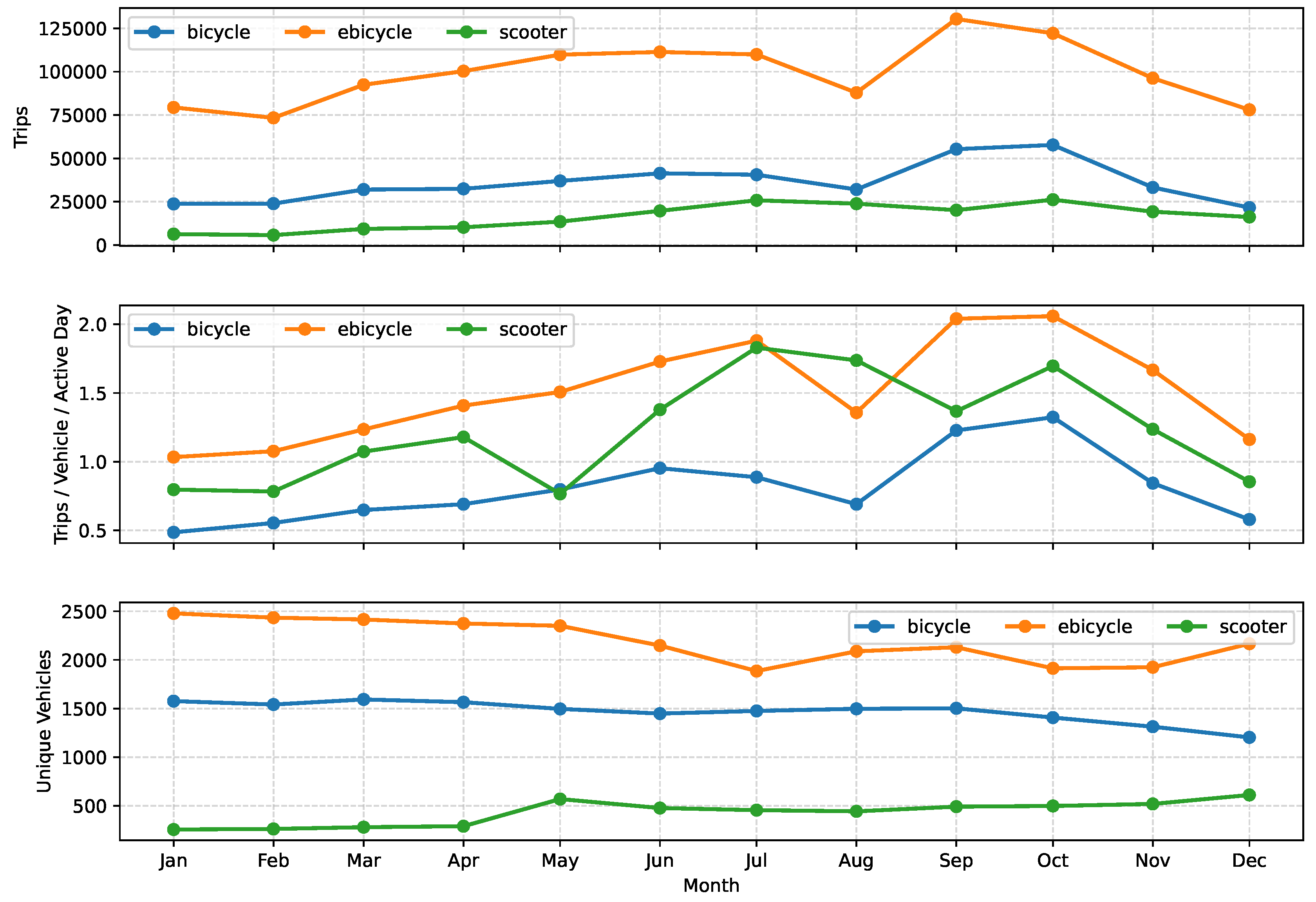

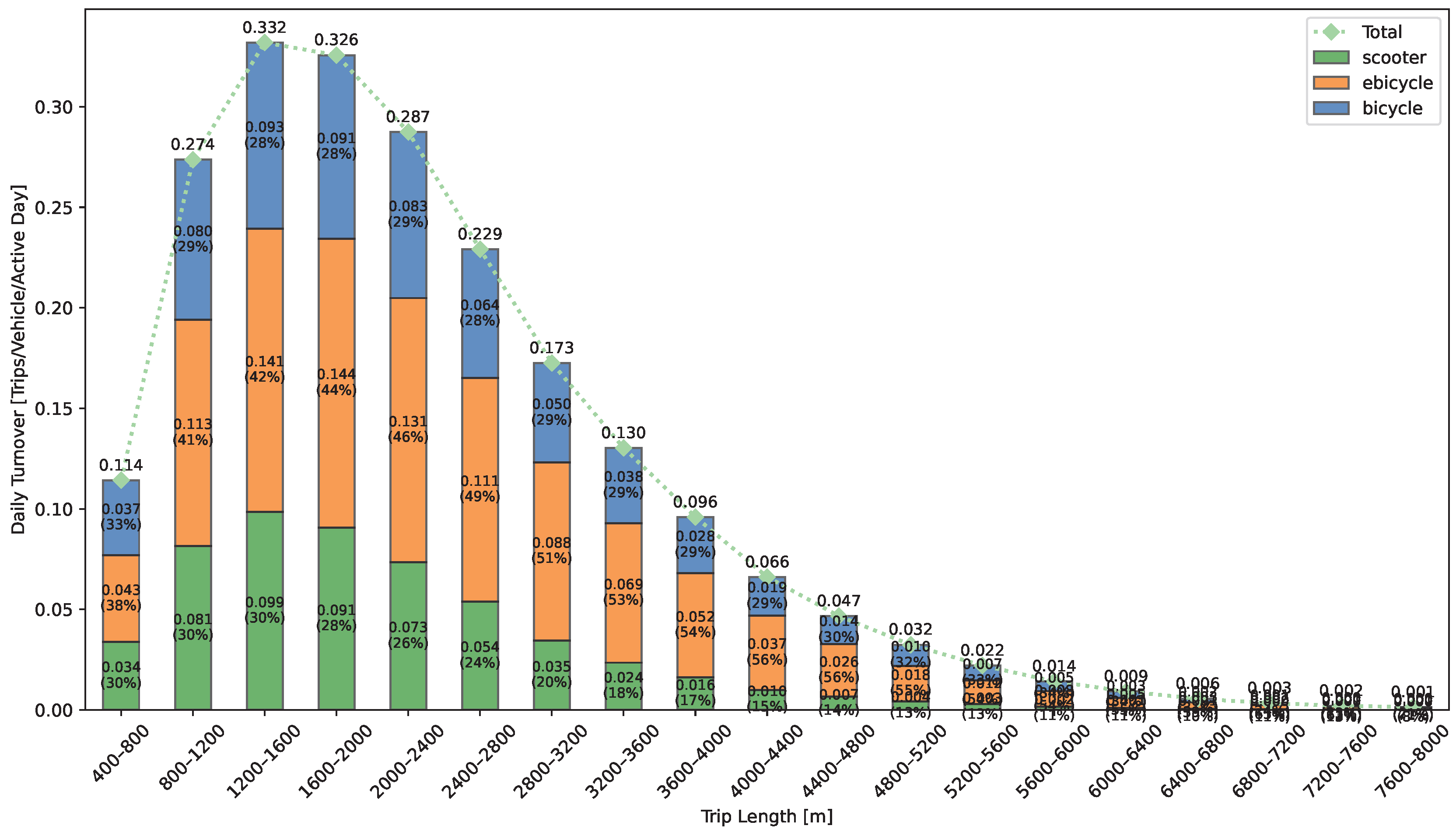

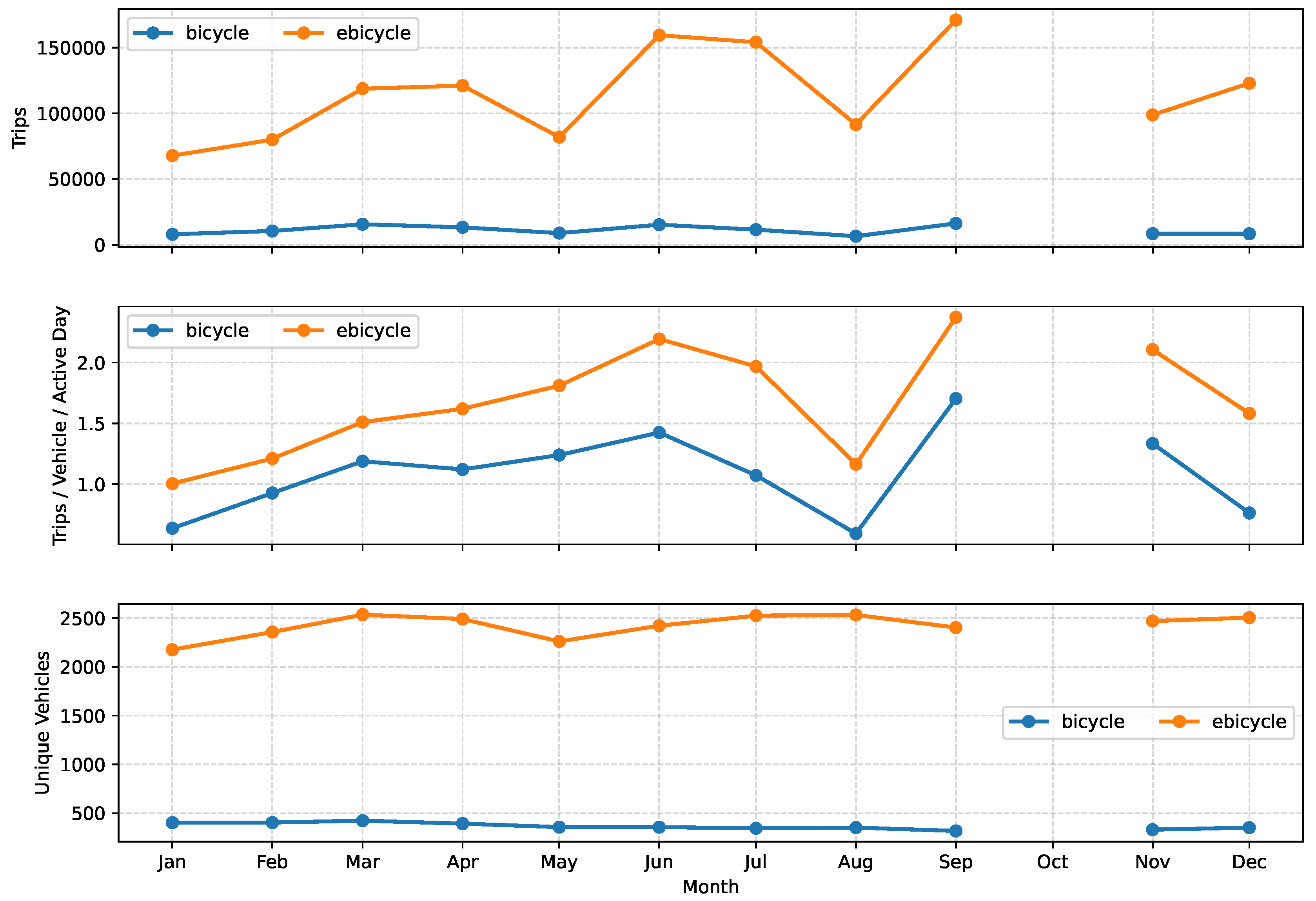

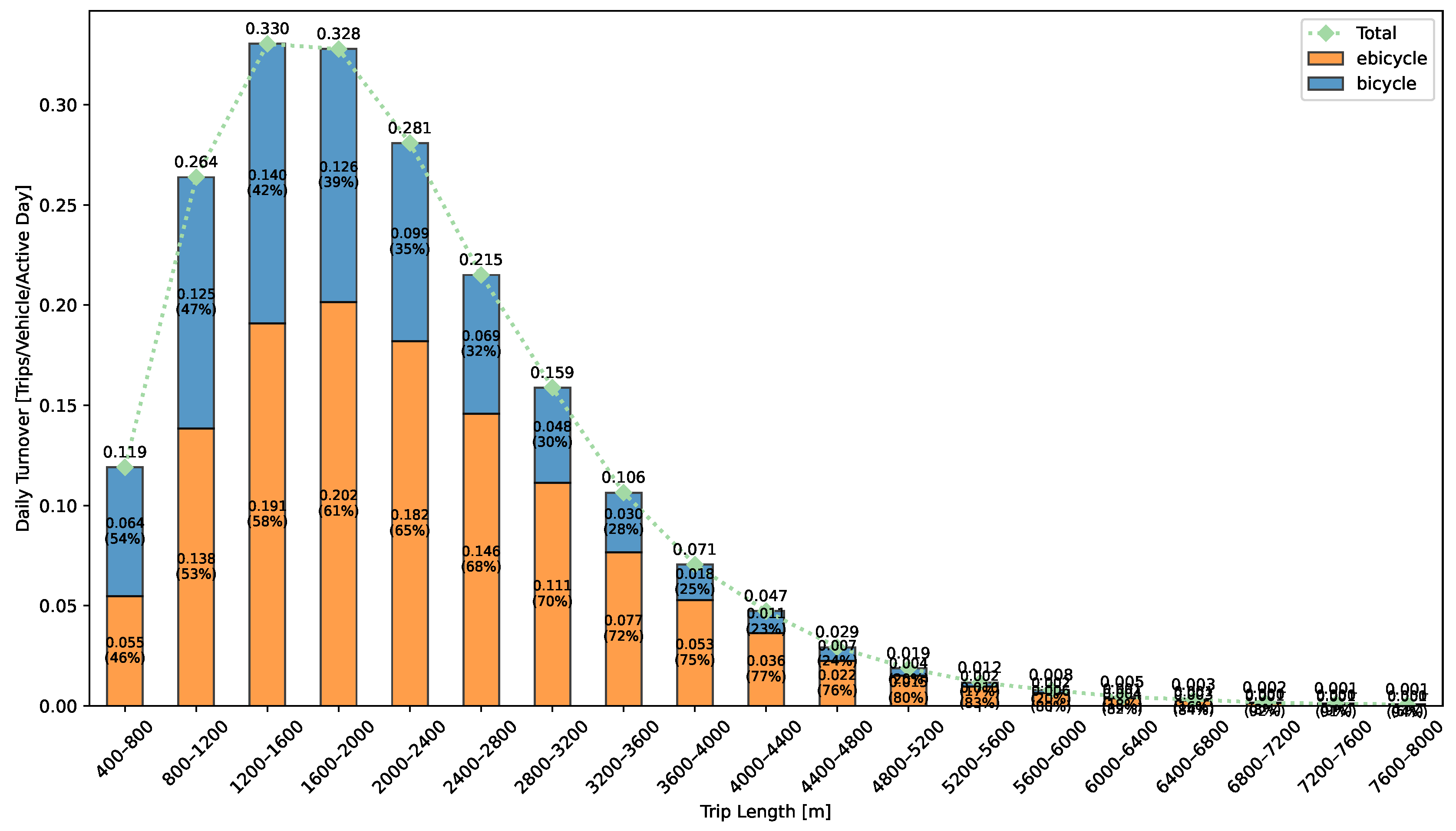

Comparing daily turnover values (

Table 11) shows that Bologna records slightly higher use of traditional bicycles than Florence and only a marginally higher use of e-bikes. Overall, Bologna’s BSS is more productive than Florence’s in terms of turnover. Both cities exhibit an increase in turnover from January to October, with a decline in August. This pattern aligns with findings from other Italian [

24] and European [

49] cities, although the turnover levels observed here are lower than those reported by Waldner et al. and Fishman. Both cities show that shared systems are most productive for trip lengths between 800 and 2800 meters. E-bikes perform well in terms of trips per bike at longer distances as well, up to about 3200 meters, as shown in

Figure 7,

Figure 15. In both Florence and Bologna, e-bikes appear superior from both operator and planner perspectives: they generate more trips per vehicle, cover a wider range of travel needs, help overcome hilly routes, and improve accessibility for people with physical limitations who might otherwise not choose the mode. E-scooters add variety but do not match e-bike trip production, which may reflect public acceptance. While bicycles are widely recognized as a standard transport mode, scooters may not be perceived similarly. Assessing whether e-scooter adoption will grow over time is beyond the scope of this study, and longer time series would help determine whether e-scooter turnover could match or surpass that of e-bikes. At present, it is only possible to say that traditional bicycles appear less attractive despite their lower prices, see

Table 10.

Table 10.

RideMovi prices by city and mode, as they were in September 2025.

Table 10.

RideMovi prices by city and mode, as they were in September 2025.

| City |

Mode |

Pay-as-you-go |

Prime Pass

|

Packages and Bundles |

| Florence |

Bike |

3.75 €/h |

15.00 €/month + 2.00 €/hour |

10.40 - 15.00 €/month |

| Florence |

E-bike |

18.00 €/h |

15.00 €/month + 6.00 €/hour |

13.70 - 25.0 €/hour |

| Florence |

E-scooter |

1.00 €/trip + 18.00 €/h |

15.00 €/month + 6.00 €/hour |

13.70 - 25.0 €/hour |

| Bologna |

Bike |

2.10 €/hour |

15.00 €/month + 2.00 €/hour |

10.40 - 15.00 €/month |

| Bologna |

E-bike |

5.00 €/hour |

15.00 €/month + 6.00 €/hour |

2.40 - 4.20 €/hour

|

Table 11.

Comparison between monthly minimum and maximum turnovers in Florence and Bologna cases during 2023.

Table 11.

Comparison between monthly minimum and maximum turnovers in Florence and Bologna cases during 2023.

| Case Study |

E-bike |

Bike |

E-Scooter |

| |

Min |

Max |

Min |

Max |

Min |

Max |

| Florence |

1.07 |

2.11 |

0.47 |

1.29 |

0.76 |

1.72 |

| Bologna |

0.98 |

2.32 |

0.58 |

1.66 |

n/a |

n/a |

| Florence/Bologna |

+9.2% |

-9.1% |

-19.0% |

-22.3% |

|

|

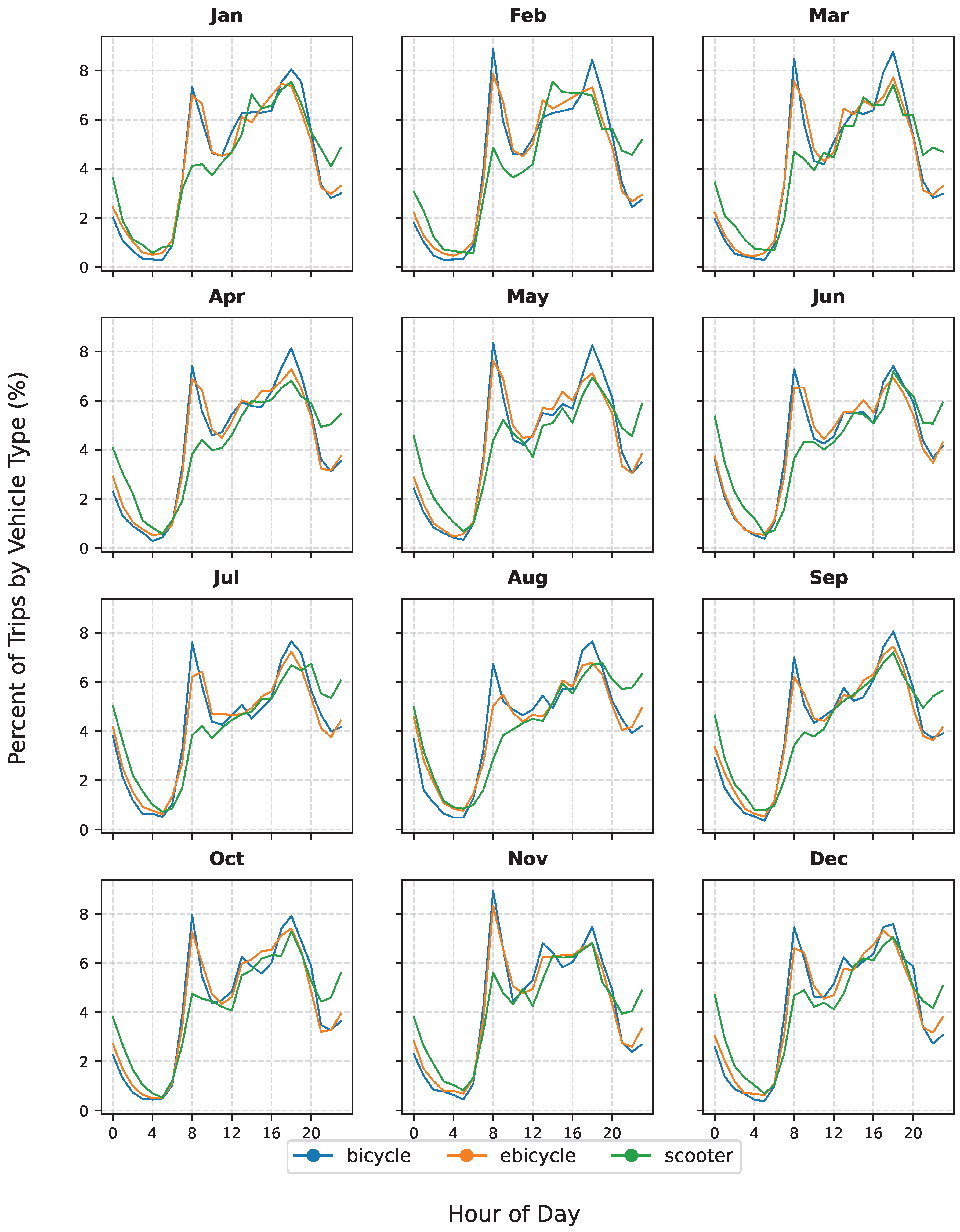

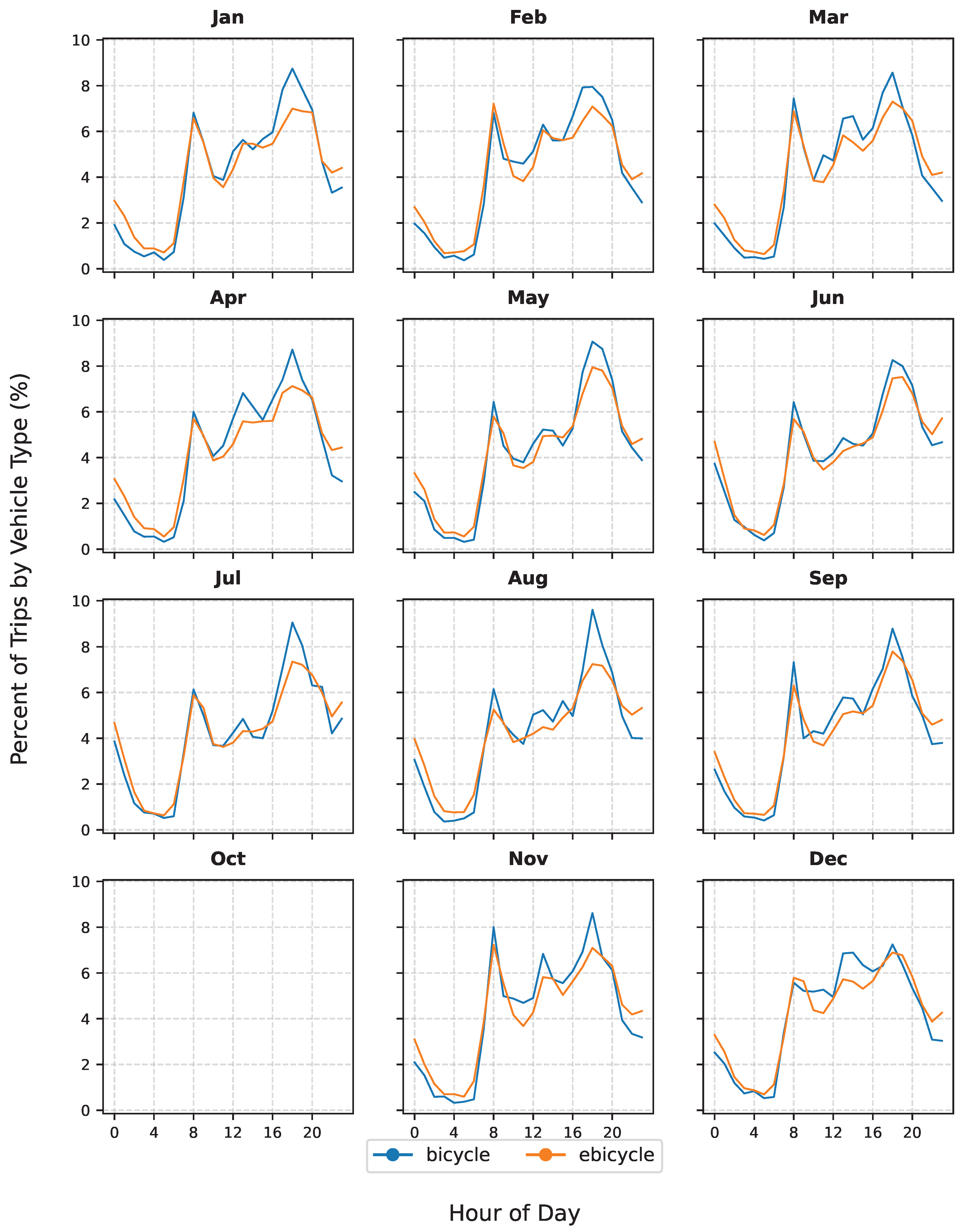

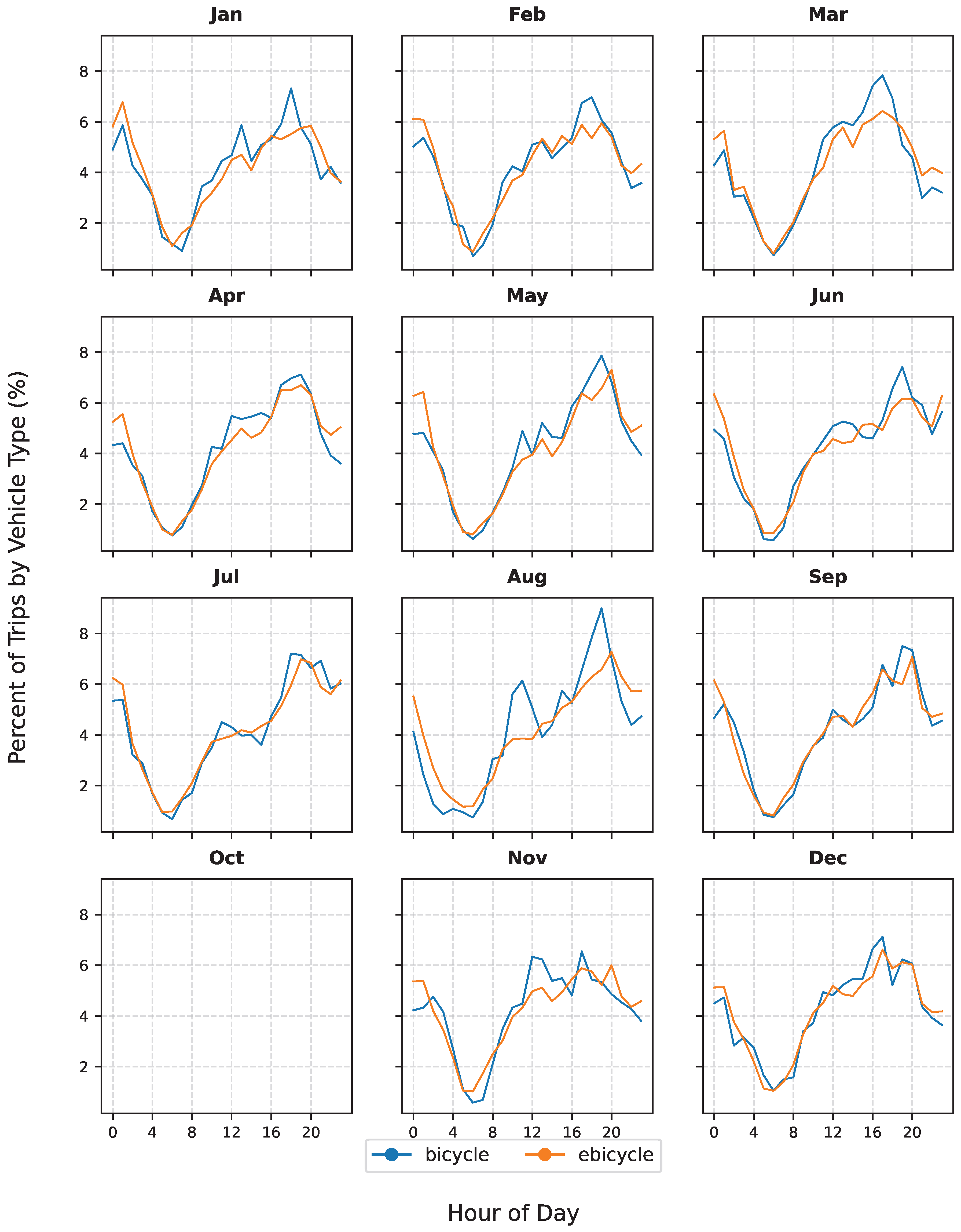

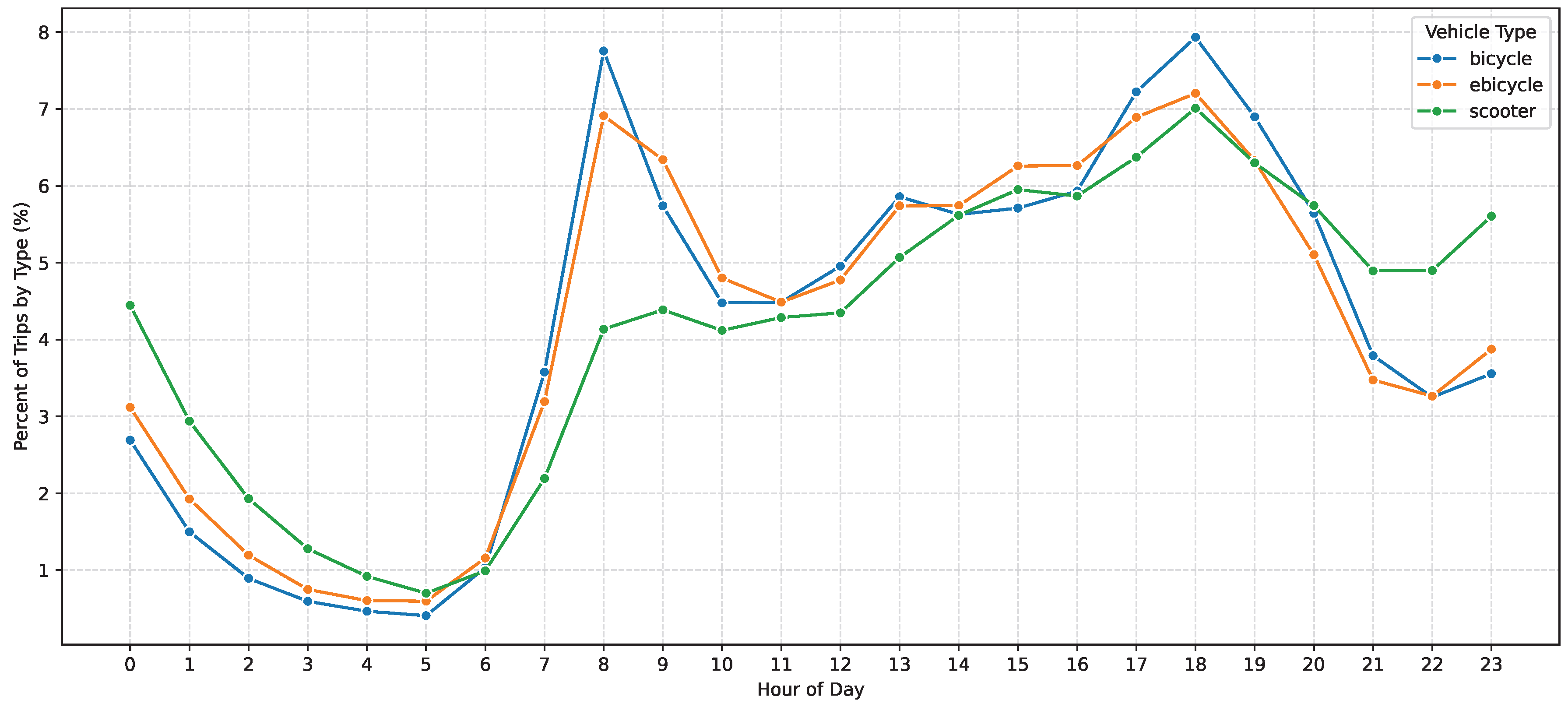

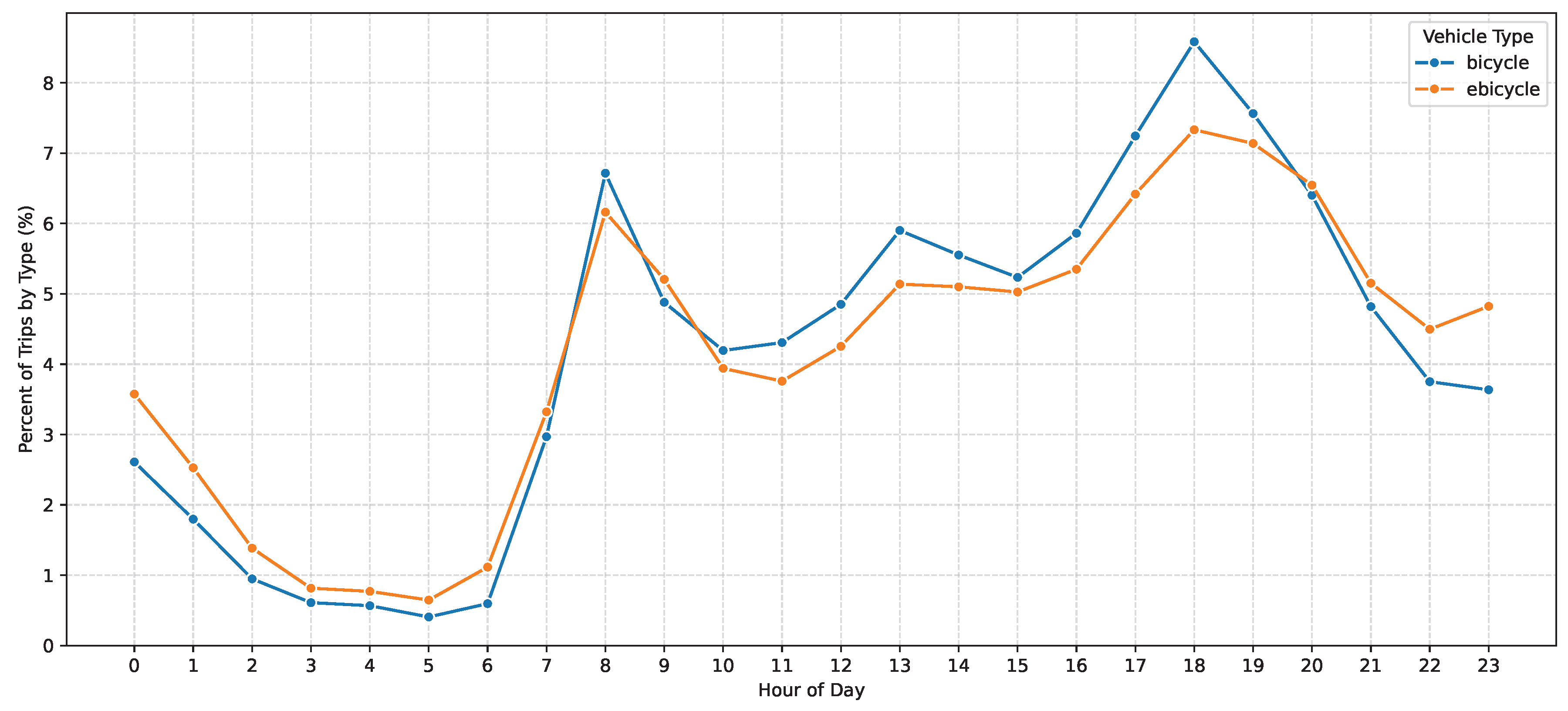

Florence exhibits a daily demand pattern that is not easily attributable to a single user type. On weekdays (

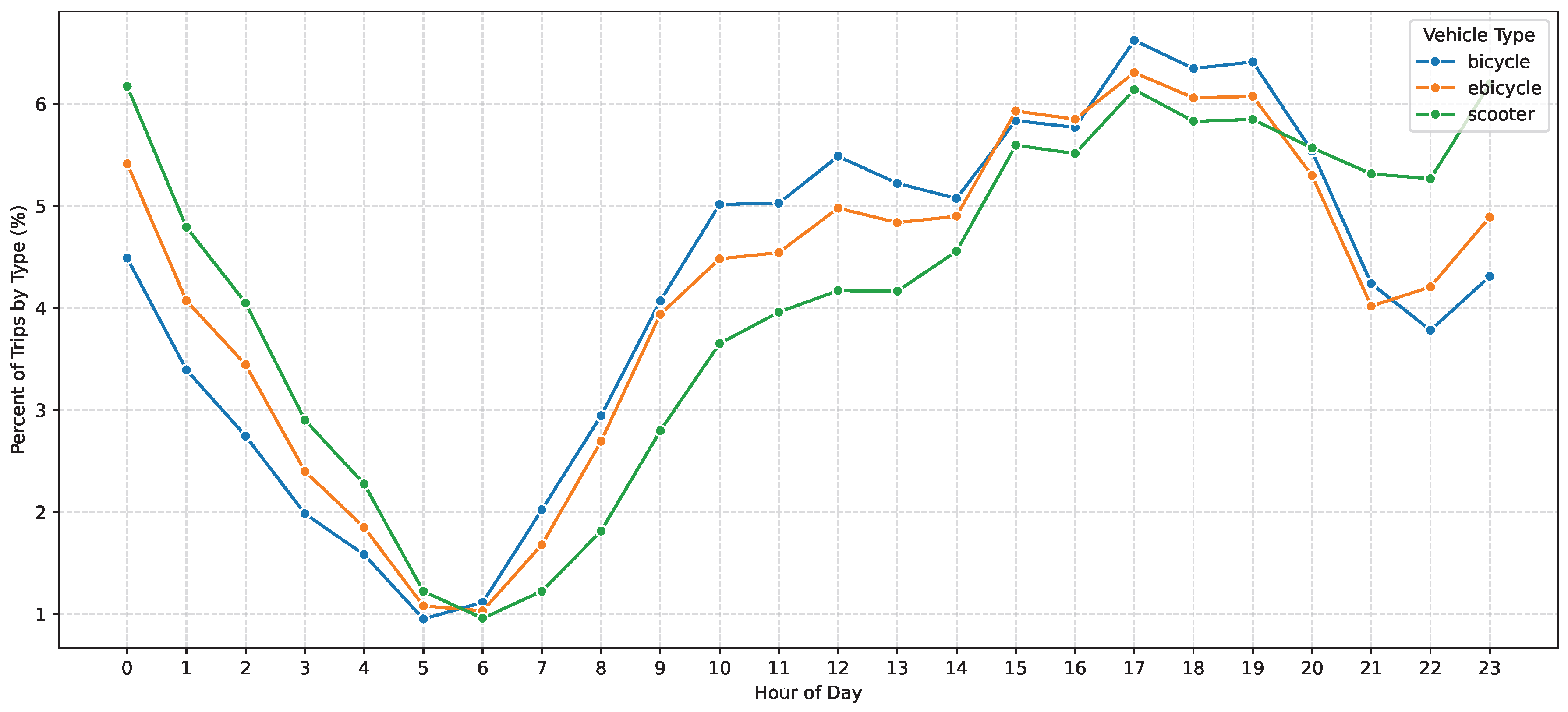

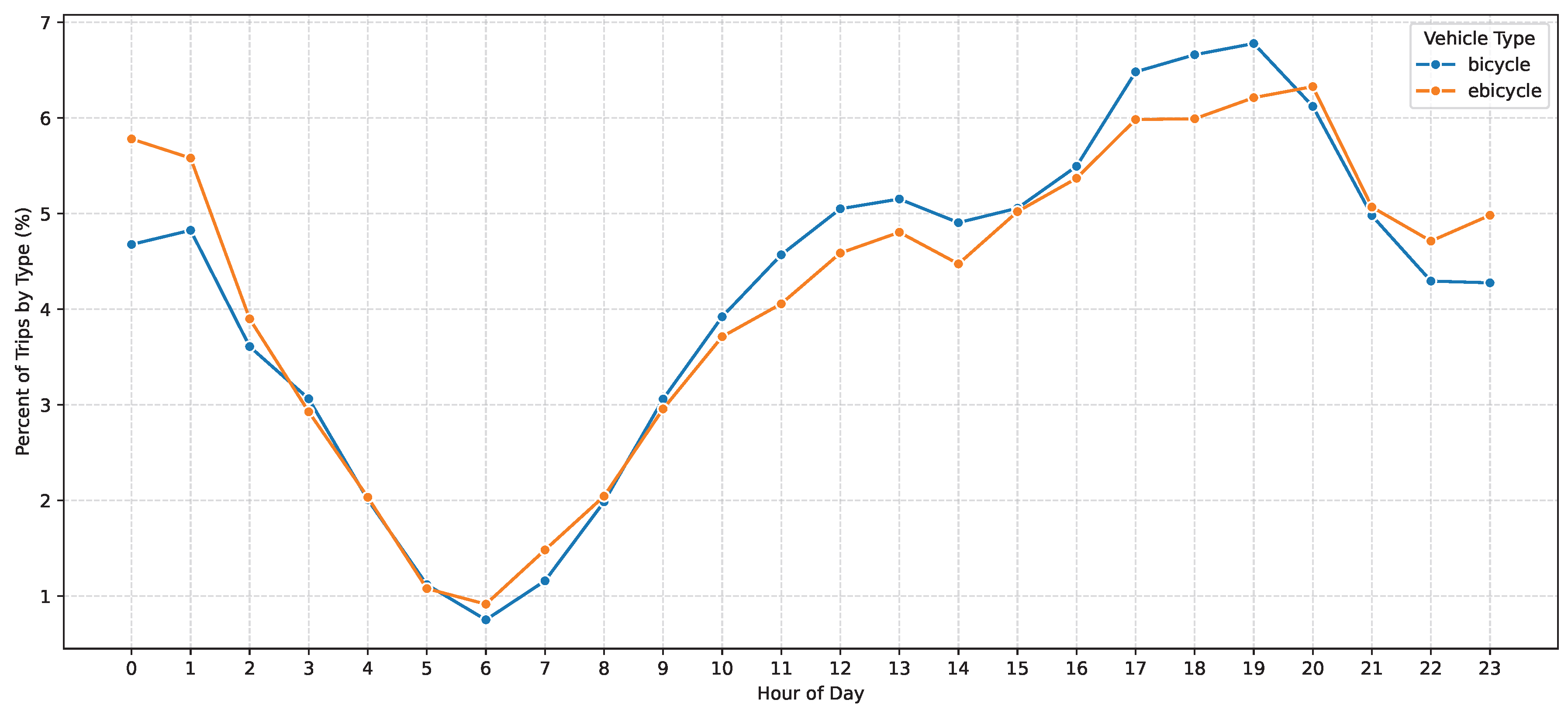

Figure 9), the two peaks in the morning and evening, typical of commuting or systematic trips, are evident. Midday demand is also sustained from 12:00 to 16:00, which likely reflects non-commuting activities such as utility or leisure trips. The high late-night demand from 22:00 to 01:00 is likewise consistent with leisure use. Overall, weekday patterns suggest a mixed profile of commuting, utility, and leisure activities, which aligns with the city’s touristic and university context. By mode, e-scooters do not show a pronounced morning peak, although an evening peak is present. This indicates that e-scooters may be less frequently chosen for morning commutes, while maintaining strong afternoon and nighttime use, consistent with a larger share of leisure trips. Weekend patterns (

Figure 10) resemble weekdays, but lack the morning and evening commuting peaks. The more uniform distribution across the day makes specific patterns less distinguishable, which is expected for weekends, when use is more likely associated with leisure or utility trips. On weekdays (

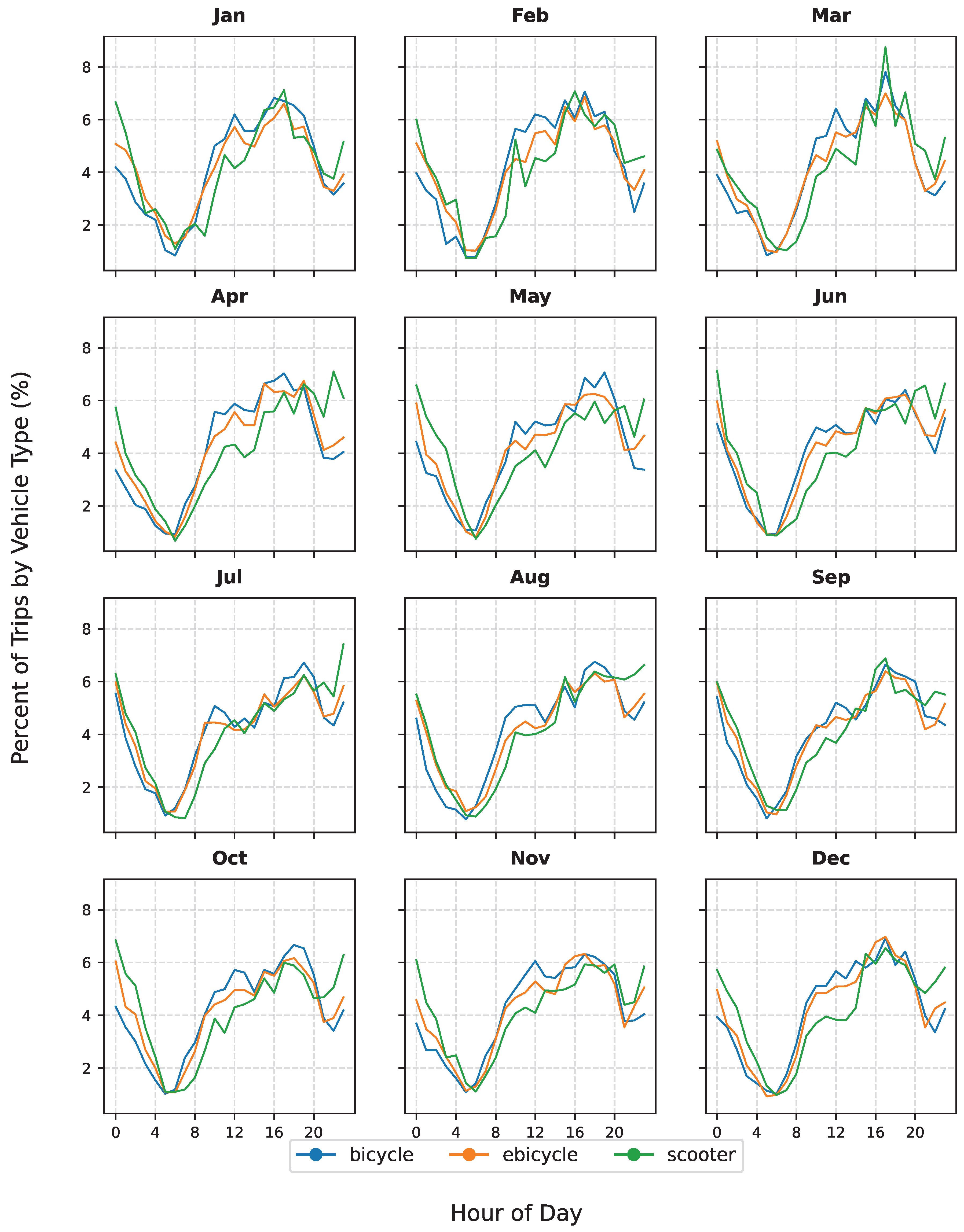

Figure 17), bicycle and e-bike use in Bologna is similar to Florence, with clear peaks at 08:00 and 18:00 during rush hours, sustained demand through the day, and some residual nighttime activity. These patterns indicate a mixed use across commuting, leisure, and utility trips. Weekend use (

Figure 18) is more uniform, with strong demand that extends into the night, up to about 02:00. O’Brien et al. [

51] propose a heuristics-driven approach to interpret daily demand patterns. They suggest that patterns with more than two peaks per day, and patterns with two commuter peaks accompanied by high intra-peak demand, indicate a mixed commuter–utility user base. Our demand pattern largely falls into the latter category, with two commuter peaks and elevated demand between them, suggesting a substantial share of utility users and, in Florence, a significant touristic component. This mixed transport purpose is also supported by results discussed previously on weekly patterns of trip length, duration, and speed, as these descriptive statistics are very homogeneous during the whole week, both on working and weekend days.

7. Conclusions

Shared micro-mobility seems to fill in numerous trip purposes; daily demand patterns suggest a strongly mixed use between commuting, utility, and leisure. The characteristics of the trips appear rather homogeneous during the week and do not seem to provide further evidence towards one activity type or the other. This homogeneity strengthens the thesis of very mixed use in both case studies. Electric modes are preferred by the users, as clearly indicated by the much higher daily turnover with respect to muscular bikes. E-bikes are often used for longer ranges with respect to e-scooters, which, on the other hand, are preferred for nighttime movements. Electric modes keep the user’s preference notwithstanding the much higher prices (up to +138% in Bologna, up to +380% in Florence); in Florence this may be due to the favorable pricing when buying a subscription to the service, while in Bologna even pay-as-you go are exceptionally low, to the point that even if e-bike costs twice as much the muscular option it is not a considerable inconvenience for the user. All shared mobility modes studied express their highest trips/day productivity in the 0.8-2.8 km range. This evidence suggests that convenience in using the service appears to drop for trips more than 3 km. Such diversified usage makes clear that shared micro-mobility is a very flexible transport service. The main issue remains the turnover values. Even the highest average turnover measured in Bologna in September 2023 is only 2.32 trips/vehicle/day, and on average over the year the value is much lower at around 1.5, less than 2 trips each day that would be made by a privately owned bike used daily for commuting.

In future work, it would be valuable to extend the analysis to a longer time series. This would allow observation of inter-year changes in supply and demand and assessment of whether daily demand patterns have shifted over time, offering insight into the evolution of usage by different user types. For example, it would be possible to examine whether the balance between commuter and leisure or tourist users has changed, and how these changes relate to service supply. Rather than relying on heuristics to classify usage, for example commuting, leisure, systematic, or non-systematic, it would be useful to employ machine learning methods such as clustering or decision-tree models to support demand categorization. Features analysed could span from temporal variables like starting time of the trip, trip descriptive statistics like trip length, speed and duration, and spatial variables, like landuse and points of interest, as they can be handled directly into HybridPY open source software used for this study. To improve the reliability of retained trips, an additional filtering phase based on simulated results could be introduced. Routed trips could be run in a micro-simulation with realistic 24-hour demand, and simulated trip times or speeds could be compared with observed values. Only trips with a close match between the synthetic and real environments would be retained. This approach may help preserve trips routed more closely to the actual paths, but it would require a highly accurate reconstruction of the network and demand for the case study. Finally, additional spatial analysis could be conducted relating rentals with land use as well as area average income for equity analyses. The same data could also be leveraged in accessibility analysis, using the reconstructed trips, similarly to full GPS traces are already used in this type of studies.

Figure 1.

Process diagram from origin-destination GPS dataset to reconstruct trips.

Figure 1.

Process diagram from origin-destination GPS dataset to reconstruct trips.

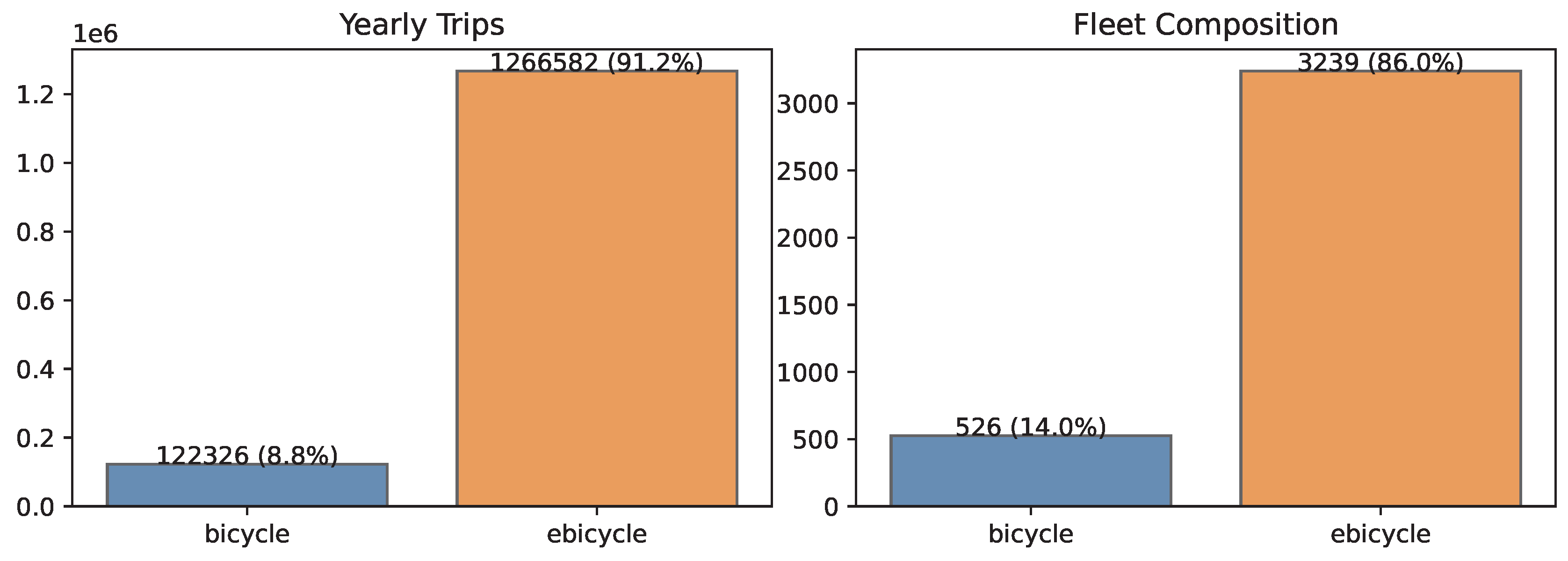

Figure 3.

From left to right: total trips in 2023, unique vehicle IDs in 2023: e-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green, city of Florence.

Figure 3.

From left to right: total trips in 2023, unique vehicle IDs in 2023: e-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green, city of Florence.

Figure 4.

Trip parameter distributions (post-filtering) for all modes in Florence. From top to bottom: trip length (meters), average trip speed (meters per second), and trip duration (seconds). E-bikes in orange, bikes in blue, and e-scooters in green.

Figure 4.

Trip parameter distributions (post-filtering) for all modes in Florence. From top to bottom: trip length (meters), average trip speed (meters per second), and trip duration (seconds). E-bikes in orange, bikes in blue, and e-scooters in green.

Figure 5.

(a) Heatmap of Florence trips’ origins. (b) Heatmap of Florence trips’ destinations. (c) Heatmap of Florence net yearly flows in the 250x250 meters cells. Negative values indicate that in that cell more trips started than ended, indicating a deficit of bikes in that area throughout the year. Positive values, in red, indicate that in that cell more trips ended than started, indicating a surplus of bikes in that area throughout the year.

Figure 5.

(a) Heatmap of Florence trips’ origins. (b) Heatmap of Florence trips’ destinations. (c) Heatmap of Florence net yearly flows in the 250x250 meters cells. Negative values indicate that in that cell more trips started than ended, indicating a deficit of bikes in that area throughout the year. Positive values, in red, indicate that in that cell more trips ended than started, indicating a surplus of bikes in that area throughout the year.

Figure 6.

Month-by-month variation of trips, average daily turnover, and fleet composition in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 6.

Month-by-month variation of trips, average daily turnover, and fleet composition in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 7.

Portions of the yearly average daily turnover by trip length ranges in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 7.

Portions of the yearly average daily turnover by trip length ranges in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 8.

Distributions of trip length, average speed, and trip duration on different days of the week in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 8.

Distributions of trip length, average speed, and trip duration on different days of the week in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 9.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekdays (Monday-Friday) for all modes in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 9.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekdays (Monday-Friday) for all modes in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 10.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekends (Saturday-Sunday) for all modes in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 10.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekends (Saturday-Sunday) for all modes in Florence. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue, e-scooters in green.

Figure 11.

From left to right: total trips in 2023, unique vehicle IDs in 2023 in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 11.

From left to right: total trips in 2023, unique vehicle IDs in 2023 in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 12.

Main trip parameters distribution (post-filtering) for all modes in Bologna. From top to bottom: Trip length [meters], Average trip speed [meters/second], and Trip duration [seconds]. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 12.

Main trip parameters distribution (post-filtering) for all modes in Bologna. From top to bottom: Trip length [meters], Average trip speed [meters/second], and Trip duration [seconds]. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 13.

(a) Heatmap of Bologna trips’ origins. (b) Heatmap of Bologna trips’ destinations. (c) Heatmap of Bologna net yearly flows in the 250x250 meters cells. Negative values indicate that in that cell more trips started than ended, indicating a deficit of bikes in that area throughout the year. Positive values, in red, indicate that in that cell more trips ended than started, indicating a surplus of bikes in that area throughout the year.

Figure 13.

(a) Heatmap of Bologna trips’ origins. (b) Heatmap of Bologna trips’ destinations. (c) Heatmap of Bologna net yearly flows in the 250x250 meters cells. Negative values indicate that in that cell more trips started than ended, indicating a deficit of bikes in that area throughout the year. Positive values, in red, indicate that in that cell more trips ended than started, indicating a surplus of bikes in that area throughout the year.

Figure 14.

Month-by-month variation of trips, average daily turnover, and fleet composition in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 14.

Month-by-month variation of trips, average daily turnover, and fleet composition in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 15.

Portions of yearly average daily turnover by trip length ranges in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 15.

Portions of yearly average daily turnover by trip length ranges in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 16.

Distributions of trip length, average speed, and trip duration on different days of the week in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 16.

Distributions of trip length, average speed, and trip duration on different days of the week in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 17.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekdays (Monday-Friday) for all modes in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 17.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekdays (Monday-Friday) for all modes in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 18.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekends (Saturday-Sunday) for all modes in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Figure 18.

Yearly average daily demand pattern of weekends (Saturday-Sunday) for all modes in Bologna. E-bikes displayed in orange, bikes in blue.

Table 1.

Trip filtering results

Table 1.

Trip filtering results

| Case Study |

Filtering Parameter |

Retaining Range |

Valid Trips |

| Bologna |

Trip Length [m] |

400<x |

83.7% |

| Trip Duration [s] |

180<x |

88.9% |

| |

x<2500 |

98.0% |

| Av. Trip Speed [m/s] |

1.00<x |

87.6% |

| |

x<6.94 |

97.6% |

| |

Total Retained |

1,389,982 (77.3%) |

| Florence |

Trip Length [m] |

400<x |

91.6% |

| Trip Duration [s] |

180<x |

93.5% |

| |

x<2500 |

98.4% |

| Av. Trip Speed [m/s] |

1.00<x |

92.2% |

| |

x<6.94 |

93.8% |

| |

Total Retained |

1,822,055 (81.2%) |

Table 2.

Average speed distribution comparison for trip reconstruction validation

Table 2.

Average speed distribution comparison for trip reconstruction validation

| Study |

Av. Speed [m/s] |

Standard Deviation [m/s] |

| This Study |

3.44 |

0.80 |

| ECC 2016 [43] |

4.20 |

1.09 |

| Ratio |

82% |

73% |

Table 4.

Overview of trip parameters distributions (post-filtering) for all modes in Florence.

Table 4.

Overview of trip parameters distributions (post-filtering) for all modes in Florence.

| Trip Parameter |

Percentile & Average |

E-bike |

Bike |

E-Scooter |

| Trip Length [m] * |

10th Percentile |

1028 |

944 |

916 |

| 50th Percentile |

2281 |

2049 |

1825 |

| 90th Percentile |

4092 |

3979 |

3407 |

| Mean |

2399 |

2325 |

2023 |

| Average Speed [m/s] * |

10th Percentile |

2.61 |

2.14 |

1.99 |

| 50th Percentile |

4.41 |

3.36 |

3.82 |

| 90th Percentile |

6.00 |

4.88 |

5.56 |

| Mean |

4.35 |

3.45 |

3.80 |

| Trip Duration [s] |

10th Percentile |

240 |

240 |

240 |

| 50th Percentile |

540 |

600 |

480 |

| 90th Percentile |

1020 |

1320 |

1080 |

| Mean |

588 |

717 |

594 |

Table 5.

Weekend versus weekday means comparison of trip length, average speed, and trip duration for all modes in Florence.

Table 5.

Weekend versus weekday means comparison of trip length, average speed, and trip duration for all modes in Florence.

| Trip Parameter (Mean) |

Transport Mode |

Weekdays |

Weekends |

Variation Weekend/Weekday |

| Trip Length [m] * |

E-bike |

2385 |

2440 |

+2.3% |

| Bike |

2282 |

2290 |

+0.4% |

| E-Scooter |

2018 |

2036 |

+0.9% |

| Average Speed [m/s] * |

E-bike |

4.36 |

4.29 |

-1.6% |

| Bike |

3.47 |

3.38 |

-2.6% |

| E-Scooter |

3.84 |

3.71 |

-3.4% |

| Trip Duration [s] |

E-bike |

580 |

610 |

+5.2% |

| Bike |

710 |

739 |

+4.1% |

| E-Scooter |

585 |

615 |

+5.1% |

Table 6.

Overview of trip parameters distributions (post-filtering) for all modes in Bologna.

Table 6.

Overview of trip parameters distributions (post-filtering) for all modes in Bologna.

| Trip Parameter |

Percentile & Average |

E-bike |

Bike |

| Trip Length [m] * |

10th Percentile |

1032 |

838 |

| 50th Percentile |

2082 |

1728 |

| 90th Percentile |

3772 |

3195 |

| Mean |

2271 |

1905 |

| Average Speed [m/s] * |

10th Percentile |

2.08 |

1.83 |

| 50th Percentile |

3.52 |

2.84 |

| 90th Percentile |

4.95 |

4.00 |

| Mean |

3.53 |

2.90 |

| Trip Duration [s] |

10th Percentile |

308 |

288 |

| 50th Percentile |

607 |

613 |

| 90th Percentile |

1161 |

1243 |

| Mean |

684 |

704 |

Table 7.

Weekend versus weekday means comparison of trip length, average speed, and trip duration for all modes in Bologna.

Table 7.

Weekend versus weekday means comparison of trip length, average speed, and trip duration for all modes in Bologna.

| Trip Parameter (Mean) |

Transport Mode |

Weekdays |

Weekends |

Variation Weekend/Weekday |

| Trip Length [m] * |

E-bike |

2264 |

2287 |

+1.01% |

| Bike |

1905 |

1906 |

+0.01% |

| Average Speed [m/s] * |

E-bike |

3.56 |

3.46 |

-2.81% |

| Bike |

2.92 |

2.82 |

-3.42% |

| Trip Duration [s] |

E-bike |

673 |

709 |

+5.35% |

| Bike |

694 |

728 |

+4.90% |

Table 8.

Comparison of trip parameters between Florence and Bologna case studies.

Table 8.

Comparison of trip parameters between Florence and Bologna case studies.

| Trip Parameter (Mean) |

Case Study |

E-bike |

Bike |

E-Scooter |

| Trip Length [m] * |

Florence |

2399 |

2284 |

2024 |

| Bologna |

2271 |

1905 |

n/a |

| Florence/Bologna |

+5.6% |

+19.9% |

|

| Average Speed [m/s] * |

Florence |

4.35 |

3.45 |

3.80 |

| Bologna |

3.53 |

2.90 |

n/a |

| Florence/Bologna |

+23.2% |

+19.0% |

|

| Trip Duration [s] |

Florence |

588 |

717 |

594 |

| Bologna |

684 |

704 |

n/a |

| Florence/Bologna |

-14.0% |

+1.8% |

|

Table 9.

Comparison of median values of trip length, speed, and duration with other case studies.

Table 9.

Comparison of median values of trip length, speed, and duration with other case studies.

| Trip Parameter (Median) |

Case Study |

E-bike |

Bike |

E-Scooter |

| Trip Length [m] |

Florence |

2181 |

2050 |

1825 |

| Bologna |

2082 |

1728 |

|

| 267 European BSS [49] |

1950 |

1750 |

|

| 30 Eur. E-Scooter Sharing [50] |

|

|

910-1790 |

| Average Speed [m/s] |

Florence |

4.41 |

3.36 |

3.82 |

| Bologna |

3.52 |

2.84 |

|

| 267 European BSS [49] |

2.22 |

2.08 |

|

| 30 Eur. E-Scooter Sharing [50] |

|

|

|

| Trip Duration [s] |

Florence |

540 |

600 |

480 |

| Bologna |

607 |

613 |

|

| 267 European BSS [49] |

750 |

750 |

|

| 30 Eur. E-Scooter Sharing [50] |

|

|

340-826 |